Abstract

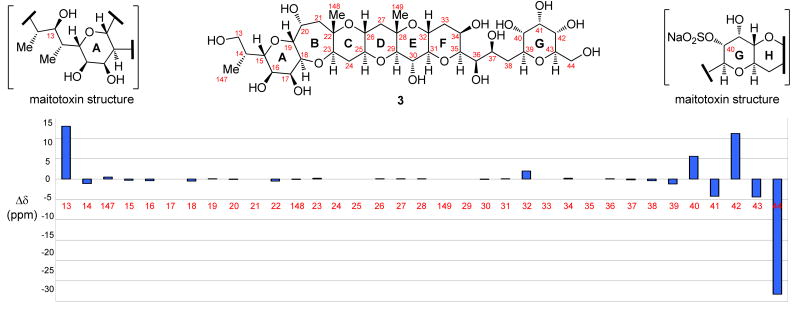

Maitotoxin (1) continues to fascinate scientists not only because of its size and neurotoxicity but also due to its molecular architecture. In order to provide further support for its structure and facilitate fragment-based biological studies, we developed an efficient chemical synthesis of the ABCDEFG segment 3 of maitotoxin. 13C NMR chemical shift comparisons of synthetic 3 with the corresponding values for the same carbons of maitotoxin revealed a close match, providing compelling evidence for the correctness of the originally assigned structure to this polycyclic system of the natural product. The synthetic strategy for the synthesis of 3 relied heavily on our previously developed furan-based technology involving sequential Noyori asymmetric reduction and Achmatowicz rearrangement for the construction of the required tetrahydropyran building blocks, and employed a B-alkyl Suzuki and a Horner–Wadsworth– Emmons olefination to accomplish their assembly and elaboration to the final target molecule.

Keywords: chemical synthesis, maitotoxin, natural products, neurotoxins, structure elucidation

Introduction

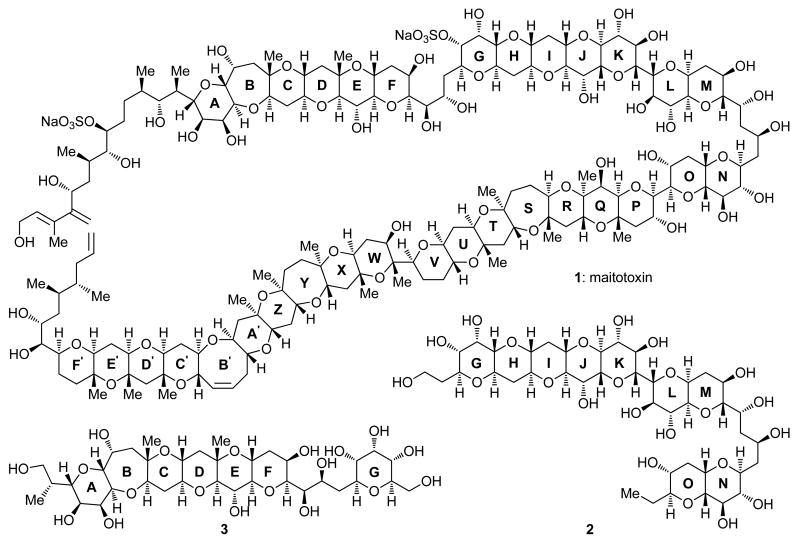

As the largest and most toxic of the secondary metabolites isolated1 and characterized to date, maitotoxin (1, Figure 1) attracted considerable attention from the chemical community.2 It was first detected in the gut of the surgeonfish Ctenochaetus striatus in 1976,1b,c and subsequently isolated in small amounts from the dinoflagellate Gambierdiscus toxicus by Yasumoto et al. in 1988.1d,e Maitotoxin is one of the causative agents of the ciguatera fish poisoning that infects consumers of contaminated seafood periodically around the Pacific Ocean, and, as such, constitutes a major environmental and health hazard.3 Its mode of action involves interference with cell membrane ion channels and Ca2+ ion influx that causes neurotoxicity.4 The structure of maitotoxin, including its absolute stereochemistry, has been assigned on the basis of NMR spectroscopic, mass spectrometric analysis, and the chemical synthesis of relatively small fragments.5–7 A recent challenge by Gallimore and Spencer to the 1996 Kishi–Tashibana– Yasumoto assigned structure of maitotoxin8 elicited a response from our laboratories that provided strong support for the originally assigned structure, first through computations9 and, subsequently, chemical synthesis of a GHIJK polycyclic system10 and a GHIJKLMNO fragment (2, Figure 1), followed by NMR spectroscopic comparisons with the natural product.11 In continuing our quest for further support of the structure of maitotoxin, and as a prelude to a possible synthesis of large domains of this molecule for biological investigations, we undertook the construction of a number of other fragments of the natural product. In this article we describe the synthesis and spectroscopic analysis of the ABCDEFG polycyclic system 3 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Structure of maitotoxin (1), previously synthesized GHIJKLMNO domain 2, and targeted ABCDEFG fragment 3.

Results and Discussion

The selection of fragment 3 and the design of its synthesis took into account the potential for further elaboration of key intermediates to larger fragments of maitotoxin, such as the decapentacyclic ABCDEFGHIJKLMNO domain. The immediate objective of this study, however, was to compare the NMR spectroscopic data of the synthetic material (3) with those of the corresponding region of the natural product as a means to confirm its originally assigned stereochemical configuration.12

1. Retrosynthetic Analysis

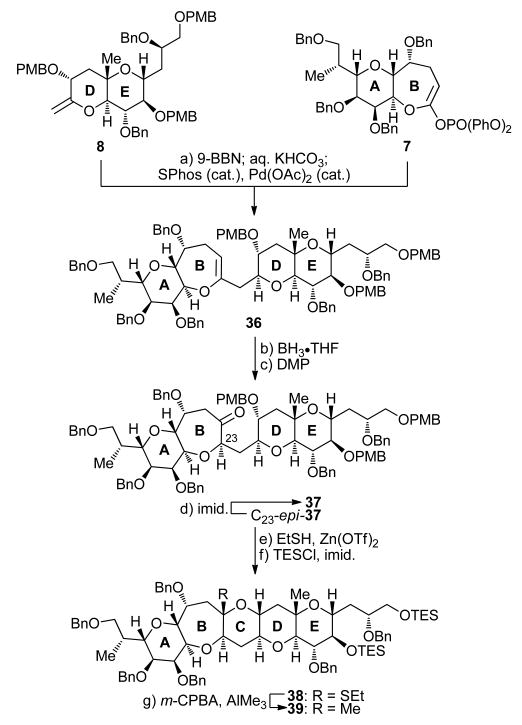

From the outset, our retrosynthetic analysis was based on the desire to devise a strategy toward fragment 3 that would be highly convergent and applied our practical and successful furan-based technologies for the construction of tetrahydropyran systems,9,10 a strategy which has also been explored by others.13 In addition, we sought to accommodate the possibility of employing an advanced intermediate to synthesize the entire ABCDEFGHIJKLMNO domain of maitotoxin at a later time. Figure 2 outlines the retrosynthetic analysis of the ABCDEFG ring system 3. Thus, sequential disconnection (Horner–Wadsworth–Emmons olefination; cyclization/reduction) of target 3 as shown led to G ring aldehyde 4 and ABCDE pentacyclic system 6 as possible precursors. While G building block 4 could be connected directly to furfuryl alcohol 5,10 the ABCDE pentacyclic intermediate 6 had to be further disconnected to smaller fragments that could be traced back to simple furan derivatives. Thus, disassembly of ring C within 6 through a B-alkyl Suzuki coupling14 and an S,O-acetal formation/methylation as shown revealed AB endocyclic ketene acetal phosphate 7 and DE exocyclic vinyl ether 8 as the required building blocks. These fragments were then connected to furfural (9) and furfuryl alcohol (5), respectively, through envisioned routes based on the furan-based synthetic technology.

Figure 2.

Retrosynthetic analysis of ABCDEFG heptacyclic system 3.

2. Furan-based Construction of the AB and DE Building Blocks 7 and 8

With sufficient quantities of ring G building block 4 available to us through our previously developed route to a closely related fragment from furfuryl alcohol 5,10,15 we focused on the synthesis of the AB and DE building blocks 7 and 8.

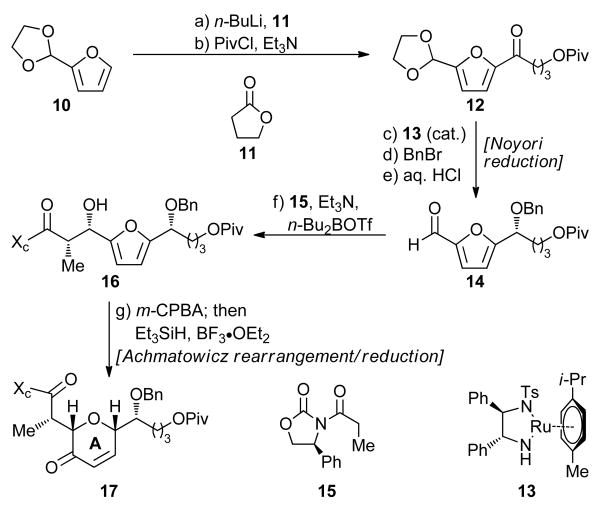

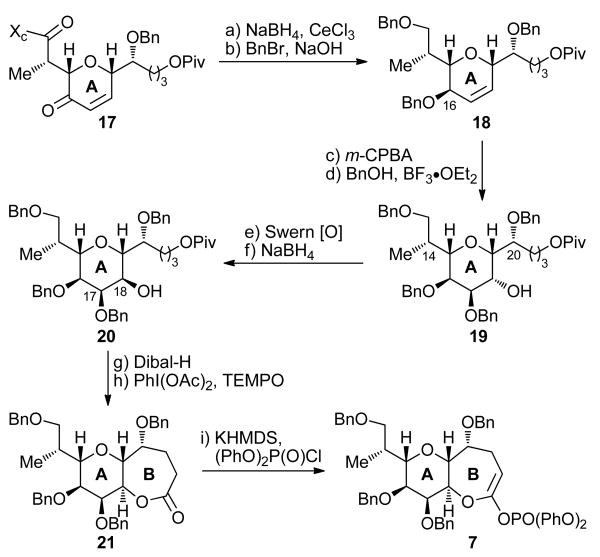

Scheme 1 summarizes the construction of ring A intermediate 17 from furfural-derived ethylene ketal 10. Thus, lithiation of 10 (n-BuLi) followed by addition of γ-lactone 11 (62% yield, 82% based on 20% recovered starting material) resulted, after pivaloate formation (PivCl, Et3N, 94% yield), in the formation of ketone 12. Ketone 12 was subjected to Noyori asymmetric transfer hydrogenation [HCO2Na, nBu4Cl, 13 (cat.)]16 to afford the corresponding alcohol in 97% yield and 94% ee (Naproxen® ester NMR spectroscopic analysis). This alcohol was then protected as its benzyl ether (NaH, BnBr, quant.) and the aldehyde moiety was liberated through the action of aq. HCl (quant.) to afford furfural derivative 14. Aldol reaction of aldehyde 14 with Evans chiral auxiliary 15 (n-Bu2BOTf, Et3N)17 furnished furfuryl alcohol 16 in 98% yield as a single diastereomer. Treatment of 16 with m-CPBA followed by addition of Et3SiH and BF3•OEt2 resulted in the formation of enone 17 through Achmatowicz rearrangement18 and subsequent reduction of the resulting hemiketal product in 75% overall yield. This one-pot procedure was routinely carried out on 50 g scale and provided ample quantities of key intermediate 17 for further elaboration. Thus, and as shown in Scheme 2, 17 was reduced under Luche conditions (NaBH4, CeCl3)19 to afford the corresponding diol (80% yield), whose benzylation (NaOH, BnBr) led to bis-benzyl ether 18 in 91% yield. As suspected, direct dihydroxylation of 18 proceeded from the wrong side of the molecule (α face); therefore, the desired diol was obtained via an indirect method involving stereoselective epoxidation (m-CPBA, 71% yield, ca. 5:1 dr), epoxide opening with BnOH–BF3•OEt2 to afford tetra-benzyl ether 19 (91% yield), and oxidation–reduction (Swern [O]; NaBH4) to afford hydroxy compound 20 (64% yield overall for the two steps) after chromatographic purification. Removal of the pivaloate group (Dibal-H, 83% yield) followed by oxidative lactonization [PhI(OAc)2, TEMPO] then led to AB ring system 21 in 92% yield. Finally, and in preparation for the planned Suzuki coupling, lactone 21 was converted to ketene acetal phosphate 7 in 97% yield through reaction with KHMDS and (PhO)2POCl.20

Scheme 1. Furan-based Synthesis of A Ring Building Block 17a.

aReagents and conditions: (a) n-BuLi (2.5 M in hexanes, 1.0 equiv), THF, −78 °C, 15 min; then 11 (1.0 equiv), −78 °C, 2.5 h, 62% plus 20% recovered starting material (10); (b) PivCl (1.2 equiv), Et3N (3.0 equiv), DMAP (0.1 equiv), CH2Cl2, 25 °C, 20 min, 94%; (c) catalyst 13 (0.01 equiv), n-Bu4NCl (0.3 equiv), HCO2Na (10.0 equiv), CH2Cl2:H2O (1:1), 25 °C, 48 h, 97% (94% ee by Naproxen® ester NMR spectroscopic analysis); (d) BnBr (2.5 equiv), n-Bu4NI (0.5 equiv), NaH (60% in mineral oil, 4.0 equiv), THF, 0 → 25 °C, 16 h, quant.; (e) 2.0 M aq. HCl:THF (1:2), 25 °C, quant.; (f) 15 (1.0 equiv), n-Bu2BOTf (1.0 M in CH2Cl2, 1.2 equiv), Et3N (1.3 equiv), −78 → 0 °C, CH2Cl2, 45 min; then 14, −78 → 0 °C, 4.5 h, 98%; (g) m-CPBA (1.2 equiv), CH2Cl2, 0 → 25 °C 2.5 h; then Et3SiH (2.0 equiv), BF3•OEt2 (2.0 equiv), −50 → −10 °C, 20 min, 75%.

Scheme 2. Completion of the Synthesis of AB Ring System 7a.

aReagents and conditions: (a) NaBH4 (4.0 equiv), CeCl3 (2.0 equiv), CH2Cl2:MeOH (1:1), −30 → −10 °C, 15 min, 80%; (b) BnBr (25 equiv), n-Bu4NI (0.75 equiv), NaOH (25% aq.):PhMe (1:1), 25 °C, 48 h, 91%; (c) m-CPBA (3.0 equiv), CH2Cl2, 25 °C, 48 h, 71% (5:1 dr); (d) BnOH (2.5 equiv), BF3•OEt2, CH2Cl2, 25 °C, 18 h, 91%; (e) (COCl)2 (2.0 equiv), DMSO (4.0 equiv), CH2Cl2, −78 °C, 2 h; then Et3N (6.0 equiv), 0 °C, 1 h; (f) NaBH4 (2.0 equiv), MeOH, −78 °C, 45 min, 64% over the two steps; (g) Dibal-H (1.0 M in CH2Cl2, 2.5 equiv), CH2Cl2, −78 °C, 1 h, 83%; (h) PhI(OAc)2 (5.0 equiv), TEMPO (0.2 equiv), CH2Cl2, 25 °C, 48 h, 92%; (i) (PhO)2P(O)Cl (10.0 equiv), KHMDS (0.5 M in PhMe, 3.0 equiv), THF:HMPA (10:1), −78 °C, 30 min, 97%.

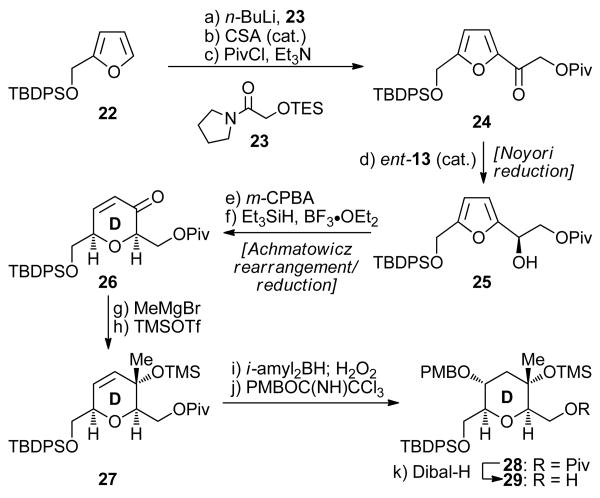

The construction of the other defined coupling partner (i.e. 8) for the proposed Suzuki coupling required D ring intermediate 29 involved the Noyori reduction/Achmatowicz rearrangement sequence, and proceeded through enone 26 as shown in Scheme 3. Thus, lithiation of the TBDPS derivative (22) of furfuryl alcohol (n-BuLi) followed by addition of amide 23 (available in two steps from glycolic acid)13e provided the corresponding acyl furan derivative in 70% yield. Protecting group exchange (desilylation with CSA, 97% yield; pivaloylation with PivCl, 93% yield) then led to pivaloate 24. Asymmetric reduction of 24, employing the Noyori protocol [HCO2Na, n-Bu4Cl, ent-13 (cat.)], delivered enantioenriched secondary alcohol 25 in 94% yield and ≥95% ee (Naproxen® ester NMR spectroscopic analysis). Conversion of furanyl alcohol 25 to enone 26 was effectively carried out through the Achmatowicz rearrangement/reduction sequence (m-CPBA; then Et3SiH, BF3•OEt2) in 74% overall yield. In contrast to the one-pot conversion of 16 to 17 (Scheme 1) described above, this transformation required removal of the m-CPBA-derived byproducts by standard work-up prior to the reduction step for satisfactory yields. Introduction of the methyl group in the growing molecule was then achieved stereoselectively and exclusively in a 1,2-fashion by reaction of enone 26 with MeMgBr to afford, after silylation of the resulting tertiary alcohol (TMSOTf, 98% yield), TMS ether 27. The axially disposed methyl group within 27 compound played a crucial role in the exclusive regio- and stereoselective addition of diisoamylborane across the double bond to afford, upon oxidative work-up (corresponding alcohol, 75% yield) and PMB ether formation [PMBOC(NH)CCl3, La(OTf)3, 97% yield], fully protected D ring system 28.21 The pivaloate group was then removed (Dibal-H, 81% yield) to afford the desired primary alcohol 29.

Scheme 3. Furan-Based Synthesis of D Ring Intermediate 29a.

aReagents and conditions: (a) 22 (1.2 equiv), n-BuLi (2.5 M in hexanes, 1.2 equiv), THF, −78 → 0 °C, 1 h; then 23 (1.0 equiv), −78 → 0 °C, 1 h, 84%; (b) CSA (0.1 equiv), CH2Cl2:MeOH (5:1), 25 °C, 1 h, 97%; (c) PivCl (1.2 equiv), Et3N (2.0 equiv), CH2Cl2, 25 °C, 12 h, 93%; (d) ent-13 (0.02 equiv), n-Bu4NCl (0.3 equiv), HCO2Na (10.0 equiv), CH2Cl2:H2O (1:1), 25 °C, 24 h, 94% (≥95% ee by Naproxen® ester NMR spectroscopic analysis); (e) m-CPBA (1.2 equiv), CH2Cl2, 0 → 25 °C, 2 h; (f) Et3SiH (3.0 equiv), BF3•OEt2 (2.0 equiv), CH2Cl2, −78 → −20 °C, 3 h, 74% over the two steps; (g) MeMgBr (2.0 equiv), THF, −78 °C, 2 h, 80%; (h) TMSOTf (1.5 equiv), Et3N (2.5 equiv), CH2Cl2, −78 °C, 1 h, 98%; (i) diisoamylborane (4.0 equiv), THF, −78 → 0 °C, 72 h; then H2O2 (35% aq., 40 equiv), NaOH (1.0 M aq., 80 equiv), 25 °C, 5 h, 75%; (j) PMBOC(NH)CCl3 (2.0 equiv), La(OTf)3 (0.05 equiv), PhMe, 25 °C, 3 h, 96%; (k) Dibal-H (2.2 equiv), CH2Cl2, −78 °C, 84%.

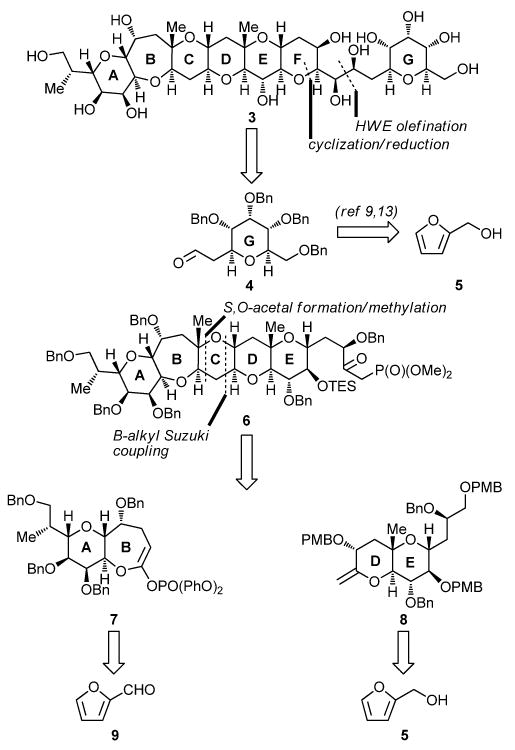

Scheme 4 summarizes the completion of the synthesis of the targeted DE fragment 8 that involved a silver-promoted cyclization of a hydroxy ynone (32→33) followed by stereoselective elaboration of the resulting bicycle to the desired system. Thus, lithiation of acetylenic compound 31 (obtained from (S)-glycidol through a standard, 5-step sequence)15 followed by addition of aldehyde 30 (obtained by DMP oxidation of alcohol 29) led to a diastereomeric mixture of secondary alcohols (86% yield, ca. 7:1 dr), which was subjected to sequential selective desilylation (K2CO3, MeOH, 99% yield) and DMP oxidation to afford hydroxy ynone 32 in 91% overall yield. Exposure of the latter to AgOTf22,10 caused ring closure, furnishing DE ring enone 33 in 76% yield. (R)-CBS reduction23 of enone 33 resulted in the selective formation of the corresponding α-hydroxy compound (93% yield), whose reaction with TBSCl and imidazole furnished, after hydroboration (BH3•THF) and oxidative workup, hydroxy TBS ether 34 (53% overall yield for the two steps). The installment of the bulky TBS group prior to the hydroboration step ensured the diasteroselectivity of the reaction, thus securing the desired stereochemical configuration around ring E. Desilylation of 34 with excess TBAF led to the corresponding triol (quant.), whose selective benzylation was achieved with BnBr and n-Bu4NI under the facilitating influence of n-Bu2SnO to afford diol 35 in 85% yield.24 DE bicyclic enol ether 8 was then derived from diol 35 through a three-step sequence involving selective tosylation of the primary hydroxyl group (TsCl, Et3N), iodide formation (NaI, 89% yield for the two steps), base-induced elimination (KOt-Bu), and PMB ether formation (NaH, PMBCl). The last two operations were carried out in the same pot and proceeded in 88% overall yield.

Scheme 4. Completion of the Synthesis of the DE Ring Coupling Partner 8a.

aReagents and conditions: (a) DMP (1.5 equiv), NaHCO3 (5.0 equiv), CH2Cl2, 25 °C, 1 h; (b) 31 (2.5 equiv), n-BuLi (2.5 M in hexanes, 2.5 equiv), THF, −78 → −40 °C, 10 min; then 30 (1.0 equiv), −78 → −50 °C, 1.5 h, 86% over the two steps; (c) K2CO3 (5.0 equiv), MeOH, 25 °C, 30 min, 99%; (d) DMP (1.5 equiv), CH2Cl2, 25 °C, 1 h, 91%; (e) AgOTf (0.9 equiv), CH2Cl2, −40 °C, 20 h, 76%; (f) (R)-CBS (1.0 M in PhMe, 1.5 equiv), BH3•THF (1.0 M in THF, 1.5 equiv), PhMe, −50 → −20 °C, 1 h, 93%; (g) TBSCl (6.0 equiv), imid. (10.0 equiv), CH2Cl2, 25 °C, 1 h, 98%; (h) BH3•THF (1.0 M in THF, 10 equiv), THF, 0 °C, 18 h; then H2O2 (35% aq., 100 equiv), NaOH (1.0 M aq., 200 equiv), 25 °C, 6 h, 54%; (i) TBAF (1.0 M in THF, 5.0 equiv), THF, 25 °C, 16 h, quant.; (j) n-Bu2SnO (1.0 equiv), PhMe, 110 °C, 12 h; then BnBr (1.5 equiv), n-Bu4NI (1.0 equiv), 100 °C, 4.5 h, 85%; (k) TsCl (3.0 equiv), Et3N (6.0 equiv), DMAP (0.1 equiv), CH2Cl2, 25 → 45 °C, 20 h; (l) NaI (10.0 equiv), DME, 85 °C, 7 h, 89% over the two steps; (m) KOt-Bu (12 equiv), THF, 0 °C, 16 h; then PMBCl (5.0 equiv), NaH (60% suspension in mineral oil, 10.0 equiv), n-Bu4NI (0.5 equiv), 25 °C, 36 h, 88%.

3. Fragment Coupling and Completion of the Synthesis of the Maitotoxin ABCDEFG Ring System

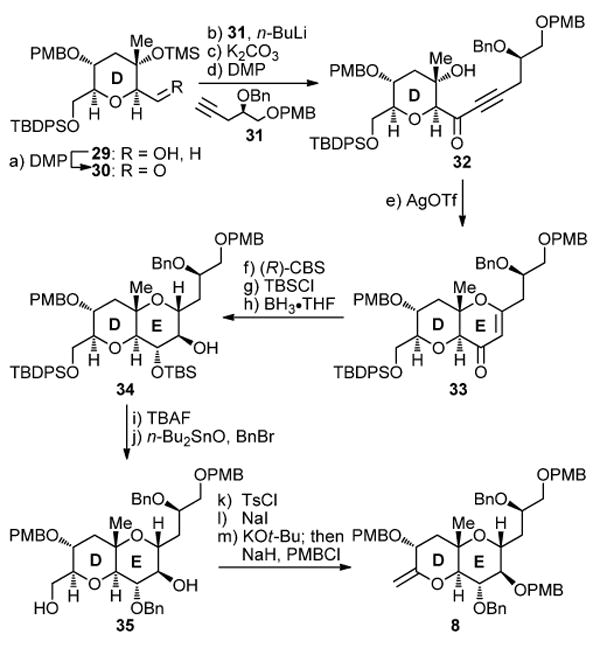

With ample quantities of both fragments (7 and 8) in hand, we proceeded to explore their union through the planned B-alkyl Suzuki coupling. It was upon considerable experimentation that we discovered the critical factors necessary for success in this reaction. Thus, an excess of cyclic vinyl ether partner 8 and relatively larger amounts of Buchwald's SPhos ligand25 were needed for this process, which proceeded smoothly under the developed conditions [8 (1.5 equiv.), 9-BBN; then aq. KHCO3; then 7 (1.0 equiv), SPhos (0.3 equiv), Pd(OAc)2 (0.15 equiv), 25 °C, 72 h] to afford coupling product 36 in 90% yield (based on phosphate 7; the excess of vinyl ether 8 was converted to the corresponding alcohol via its borane by oxidative work-up and recovered as the corresponding primary alcohol which could be recycled). In preparation for the fusion of ring C, vinyl ether 36 was regio- and stereoselectively hydroborated and converted to the corresponding α and β alcohols upon oxidative work-up (85% combined yield, α:β ca. 4.5:1 dr). The two isomers were chromatographically separated and oxidized separately with DMP to afford the respective ketones (epimeric at C23, maitotoxin numbering) [37 (97% yield) and C23-epi-37 (84% yield)]. Equilibration of the wrong diastereomer (i.e. C23-epi-37) with imidazole at 105 °C delivered a chromatographically separable mixture of 37 and C23-epi-37 (ca. 2.5:1 ratio, 91% combined yield), from which further amounts of the desired ketone isomer 37 could be obtained.26 Treatment of 37 with EtSH in the presence of Zn(OTf)2 caused sequential cleavage of the PMB groups within the substrate and thioacetalization to provide the corresponding hydroxy cyclic S,O-acetal, from which the TES protected S,O-acetal 38 was generated (TESCl, imid., 91% overall yield for the two steps). Finally, fully protected ABCDE ring system 39 was generated from 38 through sequential m-CPBA oxidation (to afford the corresponding sulfone) and axial methyl group installment (AlMe3, same pot) in 94% overall yield.

As a prelude to growing the synthesized pentacyclic fragment of maitotoxin to include rings G and F, ABCDE ring system 39 was transformed to ketophosphonate 6. Scheme 6 depicts the developed sequence to the latter intermediate, its coupling with G ring aldehyde 5, and the elaboration of the resulting product to the targeted maitotoxin ABCDEFG ring system 3. Thus, selective primary TES removal from 39 (PPTS, CH2Cl2–MeOH, 88% yield) followed by NMO–TPAP (cat.) oxidation of the resulting primary alcohol yielded aldehyde 40 (78% yield). Addition of the lithio derivative of dimethyl methylphosphonate [(MeO)2POMe, n-BuLi] to aldehyde 40 followed by DMP oxidation of the so obtained secondary alcohol furnished ketophosphonate 6 in 66% overall yield (plus 17% recovered starting material 40). The Horner– Wadsworth–Emmons coupling of ketophosphonate 6 with G ring aldehyde 410,15 proceeded smoothly under the Masamune–Roush conditions (i-Pr2NEt, LiCl)27 to afford enone 41 in 91% yield (plus 4% recovered starting material 6). From the latter intermediate to the final targeted product of ABCDEFG ring system 3, all that remained to be accomplished was forging of ring F and functionalization of the linker between the resulting fused hexacyclic system and ring G. To this end, enone 41 was treated with TsOH in MeOH:CH2Cl2 (3:1), conditions that facilitated formation of the F ring-containing heptacycle as its mixed methoxy acetal 42, of which reduction with Et3SiH in the presence of TMSOTf led to advanced intermediate 43 in 69% overall yield for the two steps. Initial attempts to install stereoselectively the missing 1,2-diol on substrate 43 through a Sharpless asymmetric dihydroxylation28 were met with difficulties, presumably due to steric congestion around the olefinic bond, forcing us to resort to the simpler NMO–OsO4 (cat.) protocol. Under the latter conditions, diol 44 was obtained as a mixture with its opposite diastereomer (ca. 3:1 dr), from which the desired isomer was isolated in 61% yield.6a,7a Finally, global debenzylation [H2, Pd(OH)2 (cat.)] revealed the targeted ABCDEFG maitotoxin fragment 3 in 97% yield.

Scheme 6. Completion of the Synthesis of the Maitotoxin ABCDEFG Ring System 3a.

aReagents and conditions: (a) PPTS (0.5 equiv), CH2Cl2:MeOH (10:1), 0 °C, 1 h, 88%; (b) NMO (3.0 equiv), TPAP (0.1 equiv), 4 Å MS, CH2Cl2:MeCN (9:1), 25 °C, 30 min, 78%; (c) (MeO)2P(O)CH3 (5.0 equiv), n-BuLi (2.5 M in hexanes, 5.0 equiv), THF, −78 °C, 1 h; then 40 (1.0 equiv), −78 °C, 2.5 h; (d) DMP (3.0 equiv), CH2Cl2, 25 °C, 30 min, 66% over the two steps plus 17% recovered starting material (40); (e) i-Pr2NEt (3.0 equiv), LiCl (3.0 equiv), 4 (1.4 equiv), MeCN, 25 °C, 72 h, 91% (95% brsm); (f) TsOH (3.0 equiv), MeOH:CH2Cl2 (3:1), 25 °C, 2 h; (g) Et3SiH (10.0 equiv), TMSOTf (5.0 equiv), MeCN, −40 → −25 °C, 30 min, 69% over the two steps; (h) NMO (3.0 equiv), OsO4 (2.5 wt % in t-BuOH, 0.05 equiv), acetone:H2O (4:1), 72 h, 61%, plus 26% of the opposite diastereomer; (i) 20% Pd(OH)2/C (50% w/w), H2, EtOH, 6 d, 97%.

4. Comparison of 13C NMR Chemical Shifts of the ABCDEFG Ring System 3 with Those Corresponding to the Same Region of Maitotoxin

NMR spectroscopic analysis of synthetic ABCDEFG fragment 3 confirmed its expected stereochemical configurations and allowed assignment of all its 13C NMR chemical shifts.29 These are listed in Table 1, together with the values reported4d for the same carbons (C13 to C44 and C147 to C149) within the corresponding region of maitotoxin. As seen from the small differences between these values (Δδ, ppm, see Table 1), which are also graphically depicted in Figure 3, there is compelling agreement between the two sets of chemical shifts (δ, ppm) for the two structures, except for those carbons residing at the edges of these structural motifs due to the drastically different structural motifs at these locations. Thus, the average chemical shift difference (Δδ) between the two sets of values for the C15 to C38 and C147 to C149 is 0.22 ppm, and the maximum difference for a given carbon is 2.0 ppm (C32). These compelling experimental values provide strong support for the originally assigned structure5–7 to the ABCDEFG region of maitotoxin (1).

Table 1.

C13 to C44 and C147 to C149 Chemical Shifts (δ) for Maitotoxin (MTX, 1) and ABCDEFG Ring System 3 and Their Differences (Δδ, ppm)a

| carbon | δ for MTX (1) (ppm) | δ for 3 (ppm) | difference (Δδ, ppm) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 13 | 78.8 | 65.8 | 13.0 | |

| 14 | 35.8 | 36.9 | −1.1 | |

| 147 | 11.0 | 10.5 | 0.5 | |

| 15 | 74.8 | 75.1 | −0.3 | |

| 16 | 69.0 | 69.4 | −0.4 | |

| 17 | 72.4 | 72.4 | 0.0 | |

| 18 | 76.0 | 76.5 | −0.5 | |

| 19 | 76.8 | 76.7 | 0.1 | |

| 20 | 71.4 | 71.5 | −0.1 | |

| 21 | 48.3 | 48.3 | 0.0 | |

| 22 | 79.1 | 79.6 | −0.5 | |

| 148 | 21.5 | 21.6 | −0.1 | |

| 23 | 76.7 | 76.5 | 0.2 | |

| 24 | 34.4 | 34.4 | 0.0 | |

| 25 | 80.7 | 80.7 | 0.0 | |

| 26 | 69.8 | 69.7 | 0.1 | |

| 27 | 45.0 | 44.9 | 0.1 | |

| 28 | 75.4 | 75.3 | 0.1 | |

| 149 | 17.9 | 17.9 | 0.0 | |

| 29 | 86.0 | 86.0 | 0.0 | |

| 30 | 69.6 | 69.7 | −0.1 | |

| 31 | 85.4 | 85.3 | 0.1 | |

| 32 | 68.2 | 66.2 | 2.0 | |

| 33 | 38.8 | 38.8 | 0.0 | |

| 34 | 66.5 | 66.3 | 0.2 | |

| 35 | 81.0 | 81.0 | 0.0 | |

| 36 | 73.1 | 73.0 | 0.1 | |

| 37 | 67.3 | 67.5 | −0.2 | |

| 38 | 37.4 | 37.8 | −0.4 | |

| 39 | 72.3 | 73.5 | −1.2 | |

| 40 | 78.9 | 73.3 | 5.6 | |

| 41 | 68.5 | 72.7 | −4.2 | |

| 42 | 80.6 | 69.4 | 11.2 | |

| 43 | 69.6 | 74.0 | −4.4 | |

| 44 | 36.3 | 64.6 | −28.3 | |

150 MHz, 1:1 methanol-d4:pyridine-d5

Figure 3.

Graphically depicted 13C chemical shift differences (Δδ, ppm) for each carbon between C13 to C44 and C147 to C149 for maitotoxin (1) and ABCDEFG ring system 3.

Conclusion

The described chemistry provides access to the ABCDEFG fragment of maitotoxin for biological investigations and opens a possible pathway to the construction of larger domains of this biotoxin. It also secures further support for the originally assigned structure to this region of maitotoxin through 13C spectroscopic analysis and comparisons with the reported data for the same region of the natural product.5d The success of the developed synthetic route demonstrates the power of the furan-based, Noyori reduction/Achmatowicz rearrangement approach to tetrahydropyran building blocks suitable for incorporation into polyether assemblies of the type found in maitotoxin and other marine neurotoxins.30

Supplementary Material

Scheme 5. Synthesis of ABCDE Ring System 39a.

aReagents and conditions: (a) 8 (1.5 equiv), 9-BBN (0.5 M in THF, 4.5 equiv), THF, 25 °C, 4 h; then KHCO3 (0.5 M aq., 13.5 equiv), 25 °C, 20 min; then 7, SPhos (0.3 equiv), Pd(OAc)2 (0.15 equiv), 25 °C, 72 h, 90%; (b) BH3•THF (1.0 M in THF, 10.0 equiv), THF, 0 °C, 18 h; then H2O2 (35% aq., 100 equiv), NaOH (1.0 M aq., 200 equiv), 25 °C, 6 h, 70% (α-diastereomer) plus 15% (β-diastereomer); (c) DMP (4.0 equiv), CH2Cl2, 0 → 25 °C, 2 h, 97% for 37, 84% for C23-epi-37; (d) imid. (200 equiv), PhMe, 105 °C, 120 h, 65% plus 26% recovered starting material (C23-epi-37); (e) 37 (1.0 equiv), Zn(OTf)2 (5.0 equiv), EtSH:CH2Cl2 (1:5), 25 °C, 20 h; (f) TESCl (10.0 equiv), imid. (20 equiv), CH2Cl2, 25 °C, 1 h, 91% over the two steps; (g) m-CPBA (2.5 equiv), CH2Cl2, 0 °C, 30 min; then AlMe3 (2.0 M in hexanes, 5.0 equiv), 0 °C, 30 min, 94%.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. D.-H Huang and G. Siuzdak for spectroscopic and mass spectrometric assistance, respectively. Financial support for this work was provided by the National Institutes of Health (U.S.A.), The Skaggs Institute of Chemical Biology, UCSD/SDSU IRACDA (postdoctoral fellowship to F.R.), and A*STAR Singapore (postdoctoral fellowship to J.J.).

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available. Scheme for the synthesis of G ring aldehyde 4, experimental procedures, and characterization data for all compounds. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.(a) Murata M, Yasumoto T. Nat Prod Rep. 2000;17:293. doi: 10.1039/a901979k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Yasumoto T, Bagnins R, Randal JE, Banner AH. Bull Jap Soc Sci Fish. 1976;37:724. [Google Scholar]; (c) Yasumoto T, Bagnins R, Vernoux JP. Bull Jap Soc Sci Fish. 1976;42:359. [Google Scholar]; (d) Yasumoto T, Nakajima I, Bagnis R, Adachi R. Bull Chem Soc Sci Fish. 1977;43:1021. [Google Scholar]; (e) Yokoyama A, Murata M, Oshima Y, Iwashita T, Yasumoto T. J Biochem. 1988;104:184. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a122438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Nicolaou KC, Postema MHD, Yue EW, Nadin A. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:10335. [Google Scholar]; (b) Nakata T, Nomura S, Matsukura H. Chem Pharm Bull. 1996;44:627. [Google Scholar]; (c) Nagasawa K, Hori N, Shiba R, Nakata T. Heterocycles. 1997;44:105. [Google Scholar]; (d) Sakamoto Y, Matsuo G, Matsukura H, Nakata T. Org Lett. 2001;3:2749. doi: 10.1021/ol016355k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Morita M, Ishiyama S, Koshino H, Nakata T. Org Lett. 2008;10:1675. doi: 10.1021/ol800267x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Morita M, Haketa T, Koshino H, Nakata T. Org Lett. 2008;10:1679. doi: 10.1021/ol800268c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Satoh M, Koshino H, Nakata T. Org Lett. 2008;10:1683. doi: 10.1021/ol8002699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Yasumoto T, Murata M. Chem Rev. 1993;93:1897. [Google Scholar]; (b) Botana LM, editor. Phycotoxins: Chemistry and Biochemistry. Blackwell Publishing; Ames: 2007. p. 345. [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Takahashi M, Ohizumi Y, Yasumoto T. J Biol Chem. 1982;257:7287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Gusovsky F, Daly JW. Biochem Pharmacol. 1990;39:1633. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(90)90105-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Ueda H, Tamura S, Fukushima N, Takagi H. Eur J Pharmacol. 1986;122:379. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(86)90421-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Konoki K, Hashimoto M, Nanomura T, Sasaki M, Murata M, Tachibana K. J Neurochem. 1998;70:409. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.70010409.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Murata M, Gusovsky F, Yasumoto T, Daly JW. Eur J Pharmacol. 1992;227:43. doi: 10.1016/0922-4106(92)90140-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.(a) Murata M, Iwashita T, Yokoyama A, Sasaki M, Yasumoto T. J Am Chem Soc. 1992;114:6594. [Google Scholar]; (b) Murata M, Naoki H, Iwashita T, Matsunaga S, Sasaki M, Yokoyama A, Yasumoto T. J Am Chem Soc. 1993;115:2060. [Google Scholar]; (c) Murata M, Naoki H, Matsunaga S, Satake M, Yasumoto T. J Am Chem Soc. 1994;116:7098. [Google Scholar]; (d) Satake M, Ishida S, Yasumoto T. J Am Chem Soc. 1995;117:7019. [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Zheng W, DeMattei JA, Wu JP, Duan JJW, Cook LR, Oinuma H, Kishi Y. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:7946. [Google Scholar]; (b) Cook LR, Oinuma H, Semones MA, Kishi Y. J Am Chem Soc. 1997;119:7928. [Google Scholar]; (c) Kishi Y. Pure Appl Chem. 1998;70:339. [Google Scholar]

- 7.(a) Sasaki M, Nonomura T, Murata M, Tachibana K. Tetrahedron Lett. 1995;36:9007. [Google Scholar]; (b) Sasaki M, Nomomura T, Murata M, Tachibana K, Yasumoto T. Tetrahedron Lett. 1995;36:9011. [Google Scholar]; (c) Sasaki M, Nonomura T, Murata M, Tachibana K. Tetrahedron Lett. 1994;35:5023. [Google Scholar]; (d) Sasaki M, Matsumori N, Muruyama T, Nonomura T, Murata M, Tachibana K, Yasumoto T. Angew Chem, Int Ed Engl. 1996;35:1672. [Google Scholar]; (e) Nonomura T, Sasaki M, Matsumori N, Murata M, Tachibana K, Yasumoto T. Angew Chem, Int Ed Engl. 1996;35:1675. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gallimore AR, Spencer JB. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2006;45:4406. doi: 10.1002/anie.200504284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nicolaou KC, Frederick MO. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2007;46:5278. doi: 10.1002/anie.200604656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nicolaou KC, Cole KP, Frederick MO, Aversa RJ, Denton RM. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2007;46:8875. doi: 10.1002/anie.200703742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nicolaou KC, Frederick MO, Burtoloso ACB, Denton RM, Rivas F, Cole KP, Aversa RJ, Gibe R, Umezawa T, Suzuki T. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:7466. doi: 10.1021/ja801139f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.For a review on wrongly assigned structures to natural products, see. Nicolaou KC, Snyder SA. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2005;44:1012. doi: 10.1002/anie.200460864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.(a) Guo H, O’Doherty GA. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2007;46:5206. doi: 10.1002/anie.200701354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Zhou M, O’Doherty GA. J Org Chem. 2007;72:2485. doi: 10.1021/jo062534+. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Guo H, O’Doherty GA. Org Lett. 2006;8:1609. doi: 10.1021/ol0602811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Harris JM, Keranen MD, Nguyen H, Young VG, O’Doherty GA. Carbohydr Res. 2000;328:17. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6215(00)00031-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Li M, Scott J, O’Doherty GA. Tetrahedron Lett. 2004;45:1005. [Google Scholar]; (g) Henderson JA, Jackson KL, Phillips AJ. Org Lett. 2007;9:5299. doi: 10.1021/ol702559e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Jackson KL, Henderson JA, Motoyoshi H, Phillips AJ. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2009;48:2346. doi: 10.1002/anie.200806111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (i) Krishna UM, Srikanth GSC, Trivedi GK. Tetrahedron Lett. 2003;44:8277. [Google Scholar]

- 14.(a) Sasaki M, Fuwa H, Inoue M, Tachibana K. Tetrahedron Lett. 1998;39:9027. [Google Scholar]; (b) Sasaki M, Fuwa H, Ishikawa M, Tachibana K. Org Lett. 1999;1:1075. [Google Scholar]; (c) Sasaki M, Ishikawa M, Fuwa H, Tachibana K. Tetrahedron. 2002;58:1889. [Google Scholar]; For a comprehensive review of applications of B-alkyl Suzuki couplings in total synthesis, see: Chemler SR, Trauner D, Danishefsky SJ. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2001;40:4544. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20011217)40:24<4544::aid-anie4544>3.0.co;2-n.

- 15.For full details, see Supporting Information.

- 16.(a) Fujii A, Hashiguchi S, Uematsu N, Ikariya T, Noyori R. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:2521. [Google Scholar]; (b) Ferrie L, Reymond S, Capdevielle P, Cossy J. Org Lett. 2007;9:2461. doi: 10.1021/ol070670a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.(a) Evans DA, Bartroli J, Shih TL. J Am Chem Soc. 1981;103:2126. [Google Scholar]; (b) Ager DJ, Allen DR, Shaad DR. Synthesis. 1996:1283. [Google Scholar]; (c) Burke MD, Berger EM, Schreiber SL. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:14095. doi: 10.1021/ja0457415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Achmatowicz O, Bielski R. Carbohydr Res. 1977;55:165. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6215(00)84452-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Luche JL. J Am Chem Soc. 1978;100:2226. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nicolaou KC, Shi GQ, Gunzner JL, Gärtner P, Yang Z. J Am Chem Soc. 1997;119:5467. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rai AN, Basu A. Tetrahedron Lett. 2003;44:2267. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang C, Forsyth CJ. Org Lett. 2006;8:2997. doi: 10.1021/ol0609457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.(a) Corey EJ, Bakshi RK, Shibata S. J Am Chem Soc. 1987;109:5551. [Google Scholar]; (b) Corey EJ, Bakshi RK, Shibata S, Chen CP, Singh VK. J Am Chem Soc. 1987;109:7925. [Google Scholar]; (c) Corey EJ, Helal CJ. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 1998;37:1987. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19980817)37:15<1986::AID-ANIE1986>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.David S, Hanessian S. Tetrahedron. 1985;41:643. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barder TE, Walker SD, Martinelli JR, Buchwald SL. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:4685. doi: 10.1021/ja042491j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johnson HWB, Majumder U, Rainer JD. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:848. doi: 10.1021/ja043396d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blanchette MA, Choy W, Davis JT, Essenfeld AP, Masamune S, Roush WR, Sakai T. Tetrahedron Lett. 1984;25:2183. [Google Scholar]

- 28.(a) Hentges SG, Sharpless KB. J Am Chem Soc. 1980;102:4263. [Google Scholar]; (b) Kwong HL, Sorato C, Ogino Y, Chen H, Sharpless KB. Tetrahedron Lett. 1990;31:2999. [Google Scholar]; (c) Sharpless KB, Amberg W, Bennani YL, Crispino GA, Hartung J, Jeong KS, Kwong HL, Morikawa K, Wang ZM, Xu D, Zhang XL. J Org Chem. 1992;57:2768. [Google Scholar]; (d) Kolb HC, VanNieuwenhze MS, Sharpless KB. Chem Rev. 1994;94:2483. [Google Scholar]

- 29.The stereochemistry and 13C chemical shift assignments of 3 were based on 1H coupling constants and COSY, ROESY, HSQC, and HMBC NMR spectroscopic experiments.

- 30.For selected reviews on the synthesis of fused polyether natural products, see: Nicolaou KC, Frederick MO, Aversa RJ. Angew Chem, Int Ed Engl. 2008;47:7182. doi: 10.1002/anie.200801696.Nicolaou KC. Angew Chem, Int Ed Engl. 1996;35:588.Nakata T. Chem Rev. 2005;105:4314. doi: 10.1021/cr040627q.Inoue M. Chem Rev. 2005;105:4379. doi: 10.1021/cr0406108.Sasaki M. Bull Chem Soc Jpn. 2007;80:856.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.