Abstract

The development of non-peptide fusion inhibitors through rational drug design has been hampered by the limited accessibility of the gp41 coiled coil target, which is highly hydrophobic, and the absence of structural data defining details of small molecule interactions. Here we describe a new approach for obtaining structural information on small molecules bound in the hydrophobic pocket of gp41, using a paramagnetic probe peptide which binds adjacent to the pocket along an extended coiled coil. Ligand binding in the pocket leads to paramagnetic relaxation effects or pseudocontact shifts of ligand protons. These effects are distance and / or orientation dependent, permitting determination of ligand pose in the pocket. The method is demonstrated with a fast-exchanging ligand. Multiple measurements at different coiled coil and probe peptide ratios enabled accurate determination of the NMR parameters. Use of a labeled probe peptide stabilizes an otherwise aggregation-prone coiled coil, and also enables modulation of the paramagnetic effect to study ligands of various affinities. Ultimately, this technique can provide essential information for structure-based design of non-peptide fusion inhibitors.

Fusion inhibitors have promising characteristics in HIV-1 prevention and therapeutics. To date, there is only one FDA-approved fusion inhibitor, the peptide T20 (Fuzeon)1. T20 acts in a dominant negative manner, preventing the association of HIV-1 gp41 N-and C-terminal domains that accompanies fusion2,3. The N-terminal domain (HR1) forms a homotrimeric coiled coil, containing a hydrophobic pocket that has been identified as a hotspot for inhibiting the protein – protein interaction. It has been the target of many studies to identify low molecular weight fusion inhibitors4,5. However, there are no experimental details defining the orientation of small molecules in the hydrophobic pocket, since it has not been possible to crystallize the coiled coil structure in the presence of ligands other than peptides. NMR has been used to demonstrate qualitatively that small molecules bind in the hydrophobic pocket6, but no specific structural information has been obtained. Rational drug design for low molecular weight fusion inhibitors has therefore relied solely on computational predictions of ligand binding7.

We have previously described development of a stable fragment of the gp41 coiled coil that was used in a fluorescence assay to quantify small molecule binding in the hydrophobic pocket8. Extending these design concepts, we describe here a novel method for obtaining explicit structural constraints on a small molecule ligand bound in the hydrophobic pocket. The technique utilizes paramagnetic NMR in a second site screening approach, in which binding and orientation of the ligand is determined with respect to a second ligand (a probe) that binds with known orientation in an adjacent site. This method was first demonstrated as an NMR screening tool with the acronym SLAPSTIC, using a spin labeled probe ligand which caused strong relaxation effects on small molecules that bound in the adjacent site9. It was recognized that differential paramagnetic relaxation effects (PRE) could potentially be used to determine the alignment between the two ligands10. Transferred pseudocontact shifts (PCS) have also been demonstrated in determination of ligand binding using lanthanide substitution in an instrinsic metal-binding site11.

The SLAPSTIC and transferred PCS effects were applied to the study of low affinity ligands in fast-exchange, for which substantial scaling of the paramagnetic effect occurs. This prevents excessive broadening or shifting of ligand resonances and permits detection through resonances of the free ligand. SLAPSTIC has not been demonstrated as a quantitative structural tool, possibly because the paramagnetic component of ligand relaxation can be difficult to obtain accurately, requiring measurement of exactly matched diamagnetic and paramagnetic samples, and incurring additive experimental errors when taking the difference of two proton relaxation rates. The approach that we describe here overcomes some of the limitations in adapting the methodology to structure determination of bound ligands. Our method does not require ligands to be in fast exchange, or perfectly matched paramagnetic and diamagnetic samples. Instead the PCS and PRE effects are modulated by varying the fraction of bound probe, and the diamagnetic component can be accurately extracted as a function of fractional occupancy of the ligand. Furthermore, we use as a probe a segment of the C-terminal domain helix of gp41, which not only has a well-defined structure, but also stabilizes the inherently hydrophobic coiled coil in solution, preventing aggregation12. Application to gp41 presents a unique opportunity to characterize small molecule binding to the hydrophobic pocket, and offers a technique that can be generalized to the study of inhibitors of protein-protein interactions.

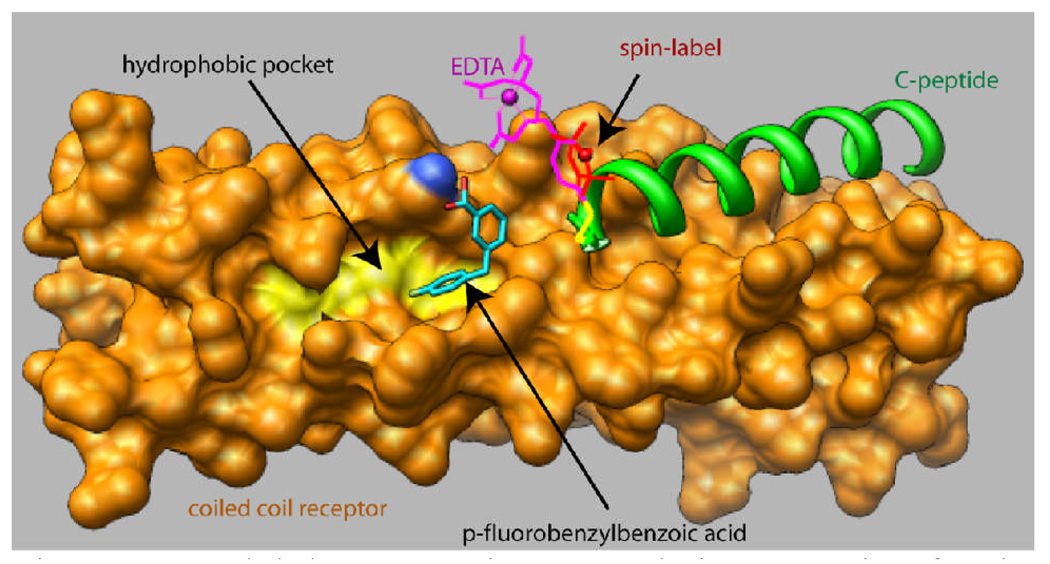

A key feature of our system is the design of a stabilized extended gp41 coiled coil structure in solution, to use as a receptor for both probe peptide and ligand binding. We have developed a 45–residue long bipyridylated HR1 segment env5.0 (bpy-GQAVSGIVQQQNNLLRAIEAQQHLLQLTV-WGIKQLQARILAVEKK-NH2), which forms a coiled coil structure upon addition of 1/3 stoichiometry of ferrous ions. We have demonstrated nanomolar binding of a 39-residue cognate C-peptide to this construct (manuscript in preparation). For this application, we have designed a truncated C-peptide, C29-e5.0 (Ac-CYTSLIESLIRESQE-QQEKNEQELRELDK-NH2), which is missing the hydrophobic pocket - binding residues. It has an N-terminal cysteine positioned at the edge of the pocket and pointing away from the protein – protein interaction surface. Labeling with a paramagnetic reporting group provides a system sensitive to ligand binding in the pocket. The concept is illustrated in Figure 1. The cysteine is labeled with the spin label MTSL or with cysteaminyl-EDTA (Toronto Research Chemicals). Distance and orientation dependent changes in ligand resonances are induced upon binding, providing positional constraints on bound ligand conformation.

Figure 1.

Model demonstrating second site screening for the hydrophobic pocket. A spin label or EDTA moiety is attached to an outer C-peptide (green) which binds in a site adjacent to the pocket. The coiled coil is shown as an orange surface with the floor of the pocket emphasized in yellow. The small ligand p-fluorobenzylbenzoic acid is shown docked in a pose which agrees with the NMR data (see text).

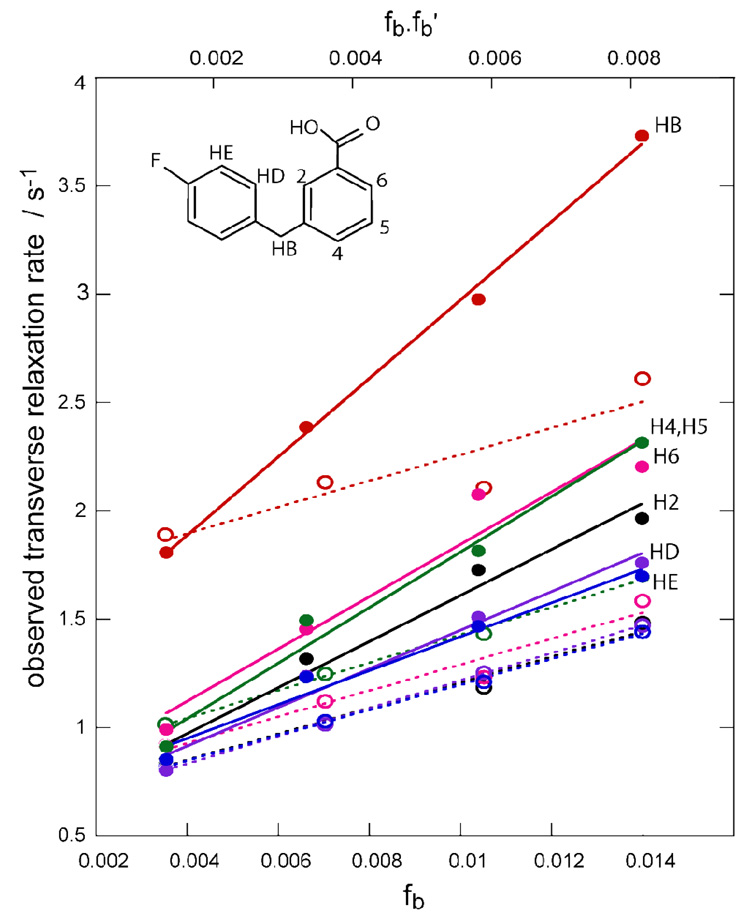

We demonstrate this experiment using a low affinity ligand, 3-p-fluorobenzylbenzoic acid (3p-FB), which binds to the hydrophobic pocket with a KI = 0.55 ± 0.05 mM. This molecule was developed as a highly soluble fragment of the hydrophobic pocket binder 11{6,11}8. Line broadening of 3p-FB occurs upon addition of 4% Fe(env5.0)3 (data not shown), confirming both ligand binding and the accessibility of the hydrophobic pocket. C29-e5.0 binds to Fe(env5.0)3 with a 3 ± 0.33 µM KI. Ligand and probe peptide binding constants were determined using our competitive inhibition fluorescence assay8 (Supplementary Data). Figure 2 shows the observed transverse relaxation rates of 300 µM 3p-FB in the presence of increasing amounts of Fe(env5.0)3 and C29-e5.0. The amounts of receptor and probe peptide were kept equal to avoid any aggregation of the receptor. Two data sets were obtained for unlabeled and MTSL-labeled C29-e5.0. Clear differentiation between the diamagnetic and paramagnetic relaxation rates was observed. Diamagnetic relaxation as a function of the fraction of bound ligand, fb could be fit to a straight line, in accordance with the expected dependence of the observed relaxation rate R2obs dia in a fast-exchanging system:

| [1] |

R2f and R2bdia are the transverse relaxation rates of free ligand, and ligand bound in the presence of diamagnetic probe peptide, respectively. R2ex is an exchange broadening term. (R2bdia − R2f + R2ex), obtained from the slope of the fit to equation [1], varies by less than 4% between the different ligand protons.

Figure 2.

Plot of relaxation rates of 300µM 3p-FB (shown inset) with Fe(env5.0)3 and unlabeled or MTSL-labeled C29-e5.0 in ratios of 3:3, 6:6, 9:9, 12:12 µM. Relaxation rates in the diamagnetic sample are plotted against fb (open symbols and dashed lines); relaxation rates in the paramagnetic sample are plotted against fb·fb’ (closed symbols, solid lines). Experiments were conducted at 500MHz. Protons H4 and H5 are overlapping.

The observed paramagnetic relaxation R2obspara depends on the product of fb with fb’, the fractional occupancy of the probe, according to:

| [2] |

Subtraction of the diamagnetic best-fit line from the paramagnetic data will give a straight line with slope R2bpara when plotted against fb∙b’. R2bpara is directly related to the inverse sixth power of the distance from spin label to observed proton, according to the Solomon-Bloembergen equations13. It varies by more than 200% among protons of the ligand, indicating a system highly sensitive to proton position with respect to the spin label.

Importantly, measurement at various receptor and probe peptide concentrations allows for averaging of the errors associated with measuring individual data points. In fact in this case, where diamagnetic slopes are essentially equal for all protons, a single diamagnetic condition prevails for the whole ligand. Additionally, the diamagnetic samples do not need to have exactly the same composition as the paramagnetic samples to obtain the trendlines.

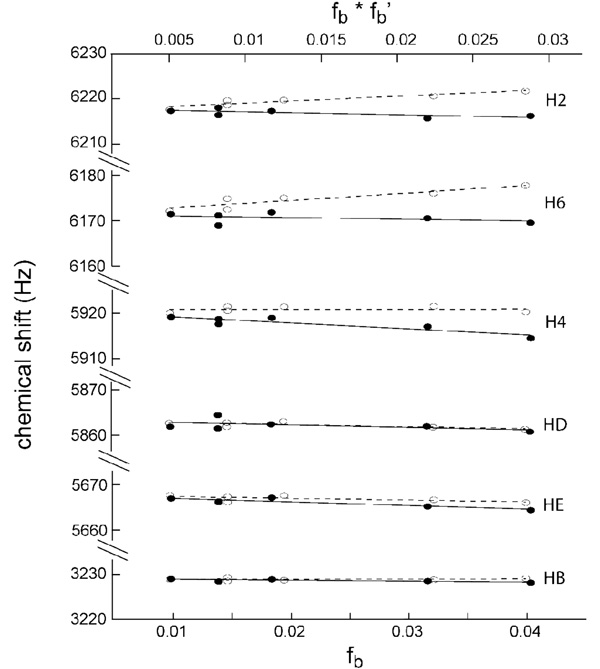

A second experiment illustrating PCS effects is shown in Figure 3, using EDTA-labeled C29-e5.0 either free or complexed to Co2+. Clear differentiation in chemical shift behavior was observed as a function of proton position, the PCS effect depending not only on distance from the spin label, but also on orientation. For example, HB protons of the methylene group experienced the largest paramagnetic relaxation effect, but a very small pseudocontact shift. This indicates that the positive and negative lobes of the Co2+ magnetic susceptibility anisotropy tensor intersect close to HB, a result that can be used to help define the tensor orientation. Similar equation to [1] and [2] hold for the variation of ligand shifts with fb and fb’, except for the absence of the exchange term of equation [1]. As with the paramagnetic relaxation effect, the slope of the paramagnetic data minus the diamagnetic trendline gives the pseudocontact shift of bound ligand protons, which is a global structural constraint on their position14,15. Averaging of several experiments is once again advantageous in reducing error, especially in the case of a weakly binding ligand where the residual shifts are small, as in this case.

Figure 3.

Observed chemical shifts of 50µM 3p-FB in the presence of Fe(env5.0)3 : EDTA-C29-e5.0 in ratios of 6;6, 9:9, 12:12, 20:20 and 25:25. Data were obtained in the absence (plotted against fb, open symbols and dashed lines) and in the presence of Co2+ (plotted against fb·fb’, solid symbols and solid lines). Experiments were performed at 800MHz.

This method relies on precise determination of ligand and probe binding constants. The experimental error in the KD’s translates into a 10% error in R2bpara or δPCS. These errors should be included in structure calculations. An inaccuracy in fb’ can be absorbed by the scaling factors (spectral density or susceptibility tensor magnitudes) linking R2bpara or δPCS to the structural constraints. Thus a system can be calibrated for a given peptide probe without requiring accurate determination of peptide KD. For universal application involving multiple probe peptides, accuracy in peptide KD‘s is required.

Cross-validation of low energy docked conformations and minimization with the PRE data yielded the unique pose of 3p-FB shown in figure 1. The carboxylate group makes a hydrogen bond with a pocket lysine residue, in common with a similar effect observed for C-peptide bound in the pocket. The methylene group HB and the edge of the ring supporting protons H4 and H5 are closest to the labeled probe peptide. We obtained an excellent fit between observed and calculated PCS data for this ligand conformation, by allowing variation of tensor parameters. This was not possible using non-PRE-minimized docked conformations (Supplementary Material).

Structural information is critical for rational design of more potent inhibitors. In a separate study, we will apply PRE and PCS restrained molecular dynamics simulations for more detailed structure determination of the bound ligand, taking into account flexibility of the paramagnetic reporter groups16 and PRE from both the spin label and a Mn2+-EDTA system.

It is relatively easy to modulate the affinity of the C-peptide for the gp41 receptor and therefore to change the amplitude of PRE and PCS effects. Mutation of residues involved in groove binding or in helical propensity have been shown to sensitively affect the peptide affinity17–19. By studying low affinity ligands with a strongly binding probe peptide and high affinity ligands with a weakly binding probe peptide, we can always obtain a weighted average of the paramagnetic effect, scaled according to fractional occupancy (see Supplementary Material for additional discussion). This tuning is not possible if the protein receptor is labeled directly. In slow exchange, protein resonances in the pocket can also be characterized, with isotopic labeling to distinguish between resonances of the protein and ligand. The use of paramagnetically labeled probe peptide rather than direct labeling of the receptor not only enables tuning and accurate determination of PRE and PCS, as shown above, but also avoids peak doubling of receptor resonances in PCS measurements, a common problem associated with stereoisomerization of metal - EDTA coordination20.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated a unique method for structural characterization of ligand bound in the hydrophobic pocket of gp41. This is the first explicit definition of a low molecular weight inhibitor of gp41, providing a significant advance in methodology for structure-based drug design of non-peptide fusion inhibitors. The method can be applied to other viruses with a similar fusion mechanism to HIV, and potentially to a variety of protein-protein interaction targets.

Supplementary Material

Binding data, PCS fitting and notes on ligand exchange rates. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported by NIH grant NS059403 to MG. Molecular graphics images were produced using the UCSF Chimera package from the Resource for Biocomputing, Visualization, and Informatics at the University of California, San Francisco (supported by NIH P41 RR-01081). The authors thank Dr. Lifeng Cai for assistance with determination of ligand inhibition constant, Dr. Jeff de Ropp at the UC Davis NMR facility for access and help with use of the NMR facility, and Dr. Robert Rizzo at SUNY Stonybrook for providing receptor and initial docked ligand coordinates.

REFERENCES

- 1.Greenberg ML, Cammack N. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2004;54:333–340. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkh330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wexler-Cohen Y, Johnson BT, Puri A, Blumenthal R, Shai Y. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:9005–9010. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M512475200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eckert DM, Kim PS. Annual Rev Biochem. 2001;70:777–810. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.70.1.777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eckert DM, Malashkevich VN, Hong LH, Carr PA, Kim PS. Cell. 1999;99:103–115. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80066-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu S, Wu S, Jiang S. Curr Pharm Des. 2007;13:143–162. doi: 10.2174/138161207779313722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frey G, Rits-Volloch S, Zhang XQ, Schooley RT, Chen B, Harrison SC. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:13938–13943. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601036103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Teixeira C, Barbault F, Rebehmed J, Liu K, Xie L, Lu H, Jiang S, Fan B, Maurel F. Bioorg Med Chem. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2007.12.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cai L, Gochin M. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007;51:2388–2395. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00150-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jahnke W, Perez LB, Paris CG, Strauss A, Fendrich G, Nalin CM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122:7394–7395. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jahnke W. In: BioNMR in Drug Research. Zerbe O, editor. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH; 2003. pp. 341–354. [Google Scholar]

- 11.John M, Pintacuda G, Park AY, Dixon NE, Otting G. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:12910–12916. doi: 10.1021/ja063584z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weissenhorn W, Calder LJ, Dessen A, Laue T, Skehel JJ, Wiley DC. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1997;94:6065–6069. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.12.6065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Solomon I, Bloembergen N. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1956;25:261–266. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bertini I, Luchinat C. NMR of Paramagnetic Molecules in Biological Systems. Vol. 3. Benjamin/Cummins Publishing Co. Inc.; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tu K, Gochin M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121:9276–9285. doi: 10.1021/ja9904540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Iwahara J, Schwieters CD, Clore GM. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:5879–5896. doi: 10.1021/ja031580d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dwyer JJ, Wilson KL, Davison DK, Freel SA, Seedorff JE, Wring SA, Tvermoes NA, Matthews TJ, Greenberg ML, Delmedico MK. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:12772–12777. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701478104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang S, York J, Shu W, Stoller MO, Nunberg JH, Lu M. Biochemistry. 2002;41:7283–7292. doi: 10.1021/bi025648y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Otaka A, Nakamura M, Daisuke N, Kodama E, Uchiyama S, Nakamura H, Kobayashi Y, Matsuoka M, Fujii N. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2002;41:2938–2939. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020816)41:16<2937::AID-ANIE2937>3.0.CO;2-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ikegami T, Verdier L, Sakhaii P, Grimme S, Pescatore B, Saxena K, Fiebig KM, Griesinger C. J Biomol NMR. 2004;29:339–349. doi: 10.1023/B:JNMR.0000032611.72827.de. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Binding data, PCS fitting and notes on ligand exchange rates. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org