Abstract

Background and Hypothesis

Although thin primary lesions are largely responsible for the rapid increase in melanoma incidence, making identification of appropriate candidates for nodal staging in this group critically important. We hypothesized that common clinical parameters may accurately estimate the risk of nodal metastasis after wide excision and determine the need for sentinel node (SN) biopsy.

Design and Setting

Review of prospectively acquired data in the large melanoma database at a tertiary referral center

Patients and Methods

We identified patients seen within 6 months of diagnosis of thin (<1 mm) melanoma and treated by wide excision alone. We examined the rate of regional nodal recurrence and the impact of clinical/demographic variables by univariate and multivariate analyses.

Results

The overall nodal recurrence rate was 2.9%; median time to recurrence was 38.3 months. Univariate analysis of 1732 patients identified male sex (p<0.001), increased Breslow thickness (p<0.001), and increased Clark level (p<0.001) as significant for nodal recurrence. Multivariate analysis identified male sex (p=0.0005, HR 3.5), younger age (p=0.0019, HR 0.45), and increased Breslow thickness (categorical, p<0.001, HR 2.47) as significant. Clark was no longer significant (p=0.6). Breslow thickness, age and sex were used to develop a scoring system and nomogram for the risk of nodal involvement: predictions ranged from 0.1% in the lowest risk group to 17.4% in the highest risk group.

Conclusion

Many patients with thin melanoma will have nodal recurrence after wide excision alone. Three simple clinical parameters may be used to estimate recurrence risk and select patients for SN biopsy.

Background

The incidence of melanoma has increased over the last several decades faster than virtually any other malignancy.1 Approximately 70% of new cases of melanoma are thin lesions, less than 1 mm in thickness.2,3 These lesions are generally considered low risk for metastasis and melanoma-related death. However, it is well known that a portion of this group will eventually suffer disease recurrence and risk death from melanoma. Due to the high number of cases, even a relatively small proportion of the group recurring will lead to a large absolute number of recurrences in thin melanoma.

Lymphatic mapping/sentinel lymph node dissection (SLND) is now a standard procedure for patients with intermediate thickness melanoma.4 The technique offers the most important piece of prognostic information for these patients, and we have recently confirmed this prognostic significance in thin melanoma.5 SLND allows selection of appropriate candidates for complete lymph node dissection (CLND), and this upfront treatment of clinically occult nodal disease appears to reduce the risk of melanoma-related death.

However, the use of SLND in thin melanoma is more controversial. Universal application of the technique would be prohibitively expensive and would expose a large number of patients with an extremely low risk of nodal disease to the real, albeit low, risk of toxicity related to the procedure. Several centers have examined their results with SLND in patients with thin melanoma, and some have suggested methods of selecting patients, but the selection factors have varied from series to series and some of the selection criteria used may be difficult for non-specialized centers to reproduce. In addition, the use of SLND series to determine the appropriate candidates for future use of the procedure is complicated by surgeon selection of cases with perceived higher risk and by relatively short follow up duration.

In order to overcome these problems, we examined our prospective melanoma database to determine the incidence of nodal recurrence among patients with thin melanoma treated by wide local excision alone. We also utilized selection factors that were relatively straightforward to reproduce.

Hypothesis

We hypothesized that a small number of straightforward clinical characteristics could be used to determine the risk of harboring occult nodal metastasis in thin melanoma.

Patients and methods

We queried our prospectively maintained database of over 13,000 melanoma patients for those diagnosed with thin (<1.00 mm) melanoma and treated with wide excision without immediate operative nodal staging (by elective node dissection or sentinel lymphadenectomy). Because of the potential for referral bias favoring recurrent cases in the database, analysis was limited to patients who were treated at our institution within 6 months of their diagnosis of melanoma. Patients did not have clinical evidence of nodal disease at the time of initial treatment, and patients recurring within 3 months of diagnosis were excluded as well. Wide excisions were performed using excision margins following recommendations current during that treatment era. Currently 1 cm margins are used. Reconstruction was most often performed with local advancement flap, though skin grafting was used as necessary based on excision size and anatomic site.

Clinical follow up recommendations consisted of complete dermatologic and physical examination every 3 months over the first two years, every 4–6 months for the next three years and annually thereafter. Routine laboratory bloodwork including complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, and lactate dehydrogenase were collected annually. A chest x-ray was obtained annually.

The primary endpoint was regional basin lymph node recurrence. Univariate analysis was performed for common prognostic variables including Breslow thickness, Clark level, ulceration, age, sex, primary tumor site. Breslow values were categorized into four groups (0.01–0.25, 0.26–0.50, 0.51–0.75, 0.76–0.99). Age was examined as a dichotomized variable and by decade. Two cutoff values previously established in the literature as significant for outcome and/or nodal recurrence were examined (50 and 60 years-old). Ulceration, regression and histologic subtype were also examined. A multivariate analysis was then undertaken by logistic regression identifying significant independent variables. Significant covariates were identified through the regression analysis and predictors were selected for incorporation into the final nomogram based upon statistical significance and clinical utility. The strongest predictor (Breslow) was scaled for point values to 100 and other predictor’s values in the model were incorporated based on their predictive value relative to that of thickness. The overall predictive strength of the model (c-index) could then be calculated.

Results

A total of 2211 patients with thin melanoma treated by wide local excision alone were identified in the database between 1971 and 2005. Of those, 1732 met entry criteria. The demographic and pathologic characteristics of this population are described in table 1. With a median follow up time of 13.2 years, 51 (2.9%) patients suffered a nodal recurrence. Median time to nodal recurrence was 38.3 months. The overall population was fairly evenly divided by sex and had a mean tumor thickness of 0.50 mm. Two-thirds of the lesions were Clark level II.

Table 1.

Demographics/ Tumor Characteristics

| Characteristic | n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | 877 (51) |

| Female | 855 (49) | |

| Age (mean in years) | 48.5 (median 47.2, range 11–95) |

|

| Breslow (mean in mm) | 0.50 (median 0.50, range .02–.99) |

|

| 0.01–0.25 | 151 (9) | |

| 0.26–0.50 | 830 (48) | |

| 0.26–0.50 | 515 (30) | |

| 0.76–0.99 | 236 (14) | |

| Clark | II | 1163 (67) |

| III | 463 (27) | |

| IV | 62 (4) | |

| V | 1 (0) | |

| Unknown | 43 (2) | |

| Ulceration | Yes | 39 (2.3) |

| No | 1243 (71.8) | |

| Unknown | 450 (26.0) | |

| Site | Trunk | 746 (43) |

| Extremity | 699 (41) | |

| Head/Neck | 277 (16) | |

| Follow up (mean in years) | 13.2 (median 12.3) | |

|

Time to nodal recurrence (median) |

38.3 months | |

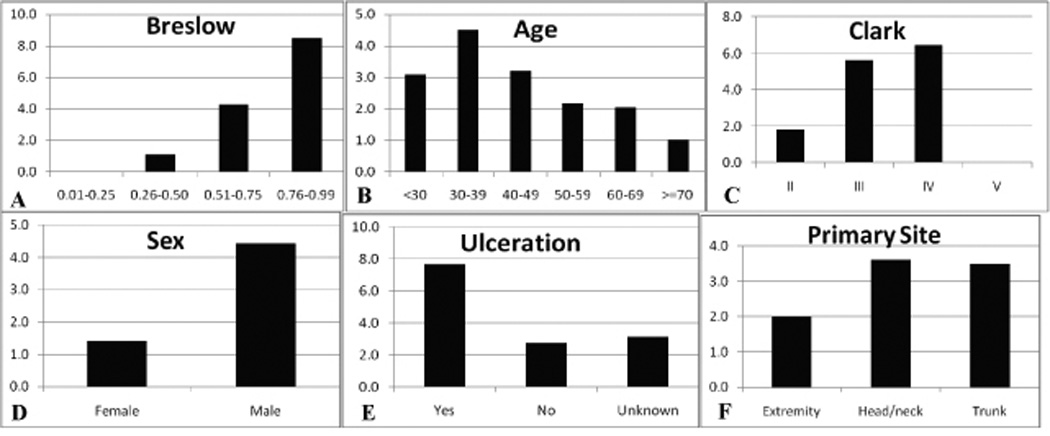

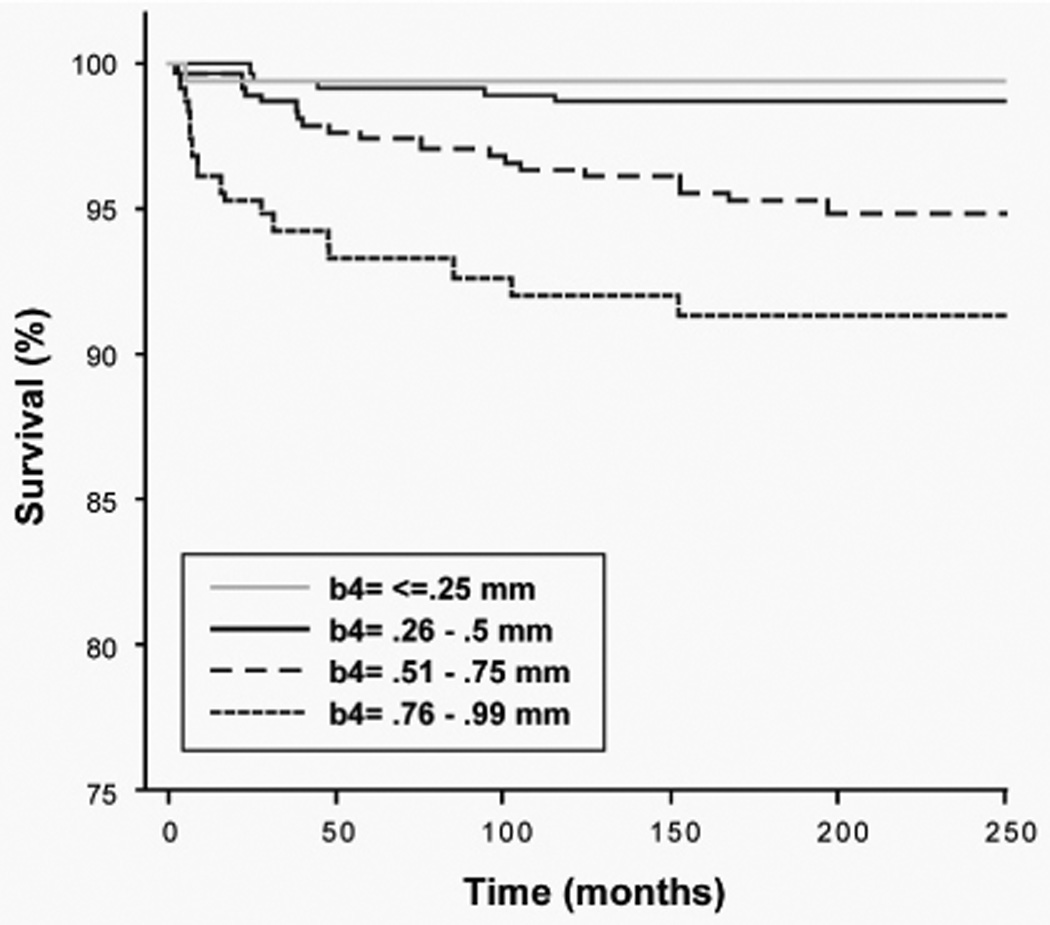

By univariate analysis, sex (p<0.001), Breslow (p<0.001), and Clark (p<0.001) were significant predictors of nodal recurrence (Table 2). Age (+\− 50) trended toward significance (p=0.08). The nodal recurrence rate increased with Breslow (<0.25 = 0%, 0.26–0.50 = 1.1%, 0.51–0.75 = 4.3%, 0.76–0.99 = 8.5%) (figure 1A). Nodal recurrence-free survival diminished most quickly in the thickest tumor category (figure 2). There were no nodal recurrences in the group with Breslow up to 0.25 mm, but it should be noted that we observed several patients excluded from this study who had been previously treated at other institutions and presented to us after nodal recurrence of melanoma <0.25mm (data not shown). The likelihood of nodal recurrence decreased with age (<30: 3.9%, 30–39: 4.5%, 40–49: 3.2%, 50–59: 2.2%, 60–69: 2.1%, >=70: 1.0% (figure 1B)) Nodal recurrence increased directly with Clark level (figure 1C). Since there was only one case rated as Clark V, nodal risk assessment in this category is unreliable. Males were much more likely to develop nodal recurrence than females (4.4% vs. 1.4%, figure 1D). Data regarding ulceration was present in 1282 (74%) patients, among whom 39 (3%) had ulceration. Those with ulceration had a 7.7% nodal recurrence rate relative to 2.7% without (figure 1E). Data for this field was more commonly missing earlier in the series, but due to both the lack of data and to the infrequency of this finding in thin melanoma, ulceration was not included in the final predictive modeling. Regression data were absent in the majority of cases, so this variable was not investigated further in this study. Although there was a somewhat lower rate of nodal recurrence among patients with extremity melanoma, the association was not significant (p=0.13, figure 1F).

Table 2.

Univariate and Multivariate predictors of nodal recurrence

| Characteristic | Univariate p-value |

Multivariate p-value |

OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (male) | <0.0001 | 0.0005 | 3.5 (1.8–7.0) |

| Breslow (by category*) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 2.5 (1.6–3.7) |

| Age (<50 years) | 0.08 | 0.0019 | 0.45 (0.24–0.86) |

| Clark | <0.0001 | 0.60 | 0.7 (0.2–2.6) |

| Primary site | 0.13 | N/A | N/A |

Breslow categories (0.01–0.25, 0.26–0.50, 0.51–0.75, 0.76–0.99)

Figure 1.

Frequency of regional nodal recurrence by several clinical and pathologic factors: A) Breslow thickness, B) age, C) Clark level, D) sex, E) ulceration, F) primary melanoma site.

Figure 2.

Regional nodal metastasis-free survival. Kaplan-Meier plot based on Breslow categories: (0.01–0.25 [n=151], 0.26–0.50 [n=830], 0.51–0.75 [n=515], and 0.76–0.99 [n=236]. Logrank p<0.01 for overall comparison and for comparison of all <0.5 vs. 0.51–0.75 vs. 0.76–0.99.

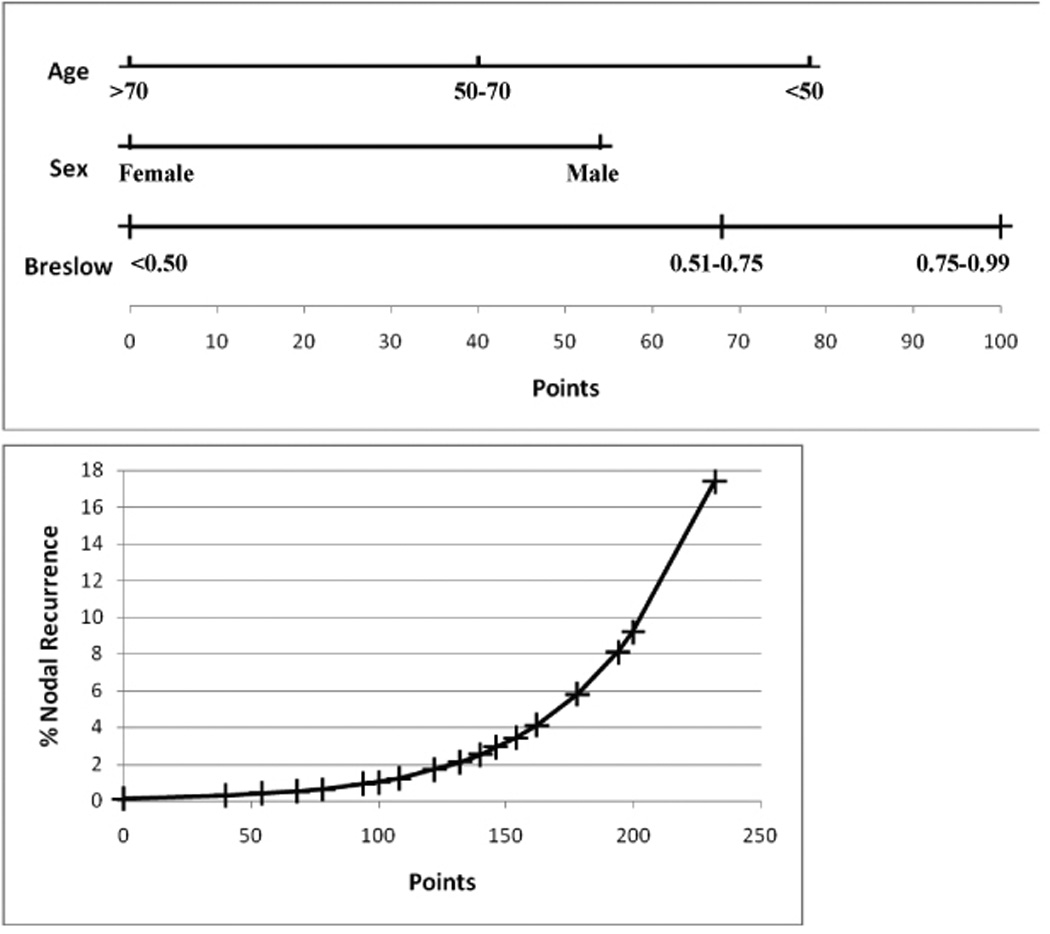

By multivariate analysis sex, age, and Breslow were significant. Primary tumor site and Clark level were not. A scoring system using Breslow, age and gender was developed to predict nodal involvement (Figure 3). Due to the very low risk of nodal metastasis for primary tumors less than 0.50 mm, these were grouped into one category. The inverse relationship between age and nodal recurrence declined to a plateau between 50 and 70 years of age and then fell again above that age. This led to the division of age into three categories (<50, 50–70, >70). Predicted risk varied from 0.1% in the lowest risk group to 17.4% in the highest risk group.

Figure 3.

Nomogram predicting regional nodal recurrence in thin melanoma. Points are assigned based upon patient and tumor characteristics. The total number of points is then used to determine the risk of nodal recurrence using the second plot. c-index =0.791.

Discussion

Although thin melanoma is generally associated with favorable outcomes, there is clearly a subgroup of patients who will suffer melanoma recurrence and subsequently die. Determination of which patients are at higher risk for relapse and death is important due to the large number of patients with a thin melanoma diagnosis. A number of series have examined factors that are associated with worse overall prognosis in thin melanoma including both large institutional database and population-based database analyses. These series confirm a relatively small, but consistent fraction of patients will recur, and suggest several potential risk factors.

McKinnon and colleagues in Australia examined both the New South Wales Cancer Registry and the Sydney Melanoma Unit database.2 For the SMU group the survival was 92.7% at 10 years and for the NSW registry it was 96.4%. The series noted a predilection toward late recurrence (median time to recurrence 49.8 months) and the importance of long-term follow up in accurately assessing melanoma risk. They also noted a steady decline in 10-year survival with increasing Breslow thickness: <0.50 = 98%, 0.51–0.75 = 96.6%, 0.76–1.00 = 91.5%. Gimotty et al performed a similar study using the SEER and University of Pennsylvania Pigmented Lesion Group (PLG) database.3 The 10-year survival for thin melanoma in the SEER database was 95.1%. The PLG analysis found that Clark level (II vs. III/IV), gender and mitotic rate figured into a decision tree analysis. The Australian analysis reported a Clark discrimination of II/III vs. IV. Investigators at Duke University examined their database and found a 9.4% rate of recurrence after thin melanoma for patients followed over time.6 Male gender, older age and Breslow thickness (>0.75mm) were adverse prognostic factors in this analysis.

However, the predictors for worse overall or melanoma-related survival are not the same as those that predict nodal involvement. For example, increased age is a factor that is clearly related to worse overall and melanoma-specific survival, but paradoxically it is associated with a lower risk of nodal metastasis. We recently reported diminished lymphatic function with age seen during SN biopsy as a possible biological mechanism to explain this paradox.7 It is apparent that a prediction system specifically tailored to identify nodal risk is needed to select patients for additional nodal evaluation, rather than an overall prognostic model.

It is now well established that the status of regional lymph nodes is the most important prognostic variable in clinically localized melanoma. Use of SLND allows assessment of the regional nodal basin with minimal morbidity, and multiple institutional series have confirmed the prognostic value of SN staging.8 A recent prospective, multicenter clinical trial demonstrated that the SN status was the most powerful predictor of outcome in patients with clinically localized melanoma.4 Since the majority of new cases of melanoma are thin lesions, the absolute number of recurrences in this group is actually quite large. For example, of 100 patients with melanoma, approximately 70 will have thin lesions. If the overall sentinel node metastasis rate is 3% for this group, 2 will have nodal metastases. Of the remaining 30 patients, approximately 23 will have intermediate thickness lesions. With a 20% sentinel node metastasis rate, 5 will be positive. So in absolute terms, due to the prevalence of thin lesions, metastases from thin lesions will account for over one quarter of positive nodes in these patients.

The prognostic importance of SN metastasis in thin melanoma has been questioned due to the low volume of disease often found in the SN of these patients. Indeed some small series have not found an independent value in the SN status.9However, our own series of SLND for thin melanoma, which includes a larger number of patients and enjoys longer follow up, confirms a very significant independent prognostic impact of SN status in thin melanoma.5,10 The SN information is therefore very important for the subgroup of thin melanoma patients who harbor clinically occult metastases. However, it has also been shown that completely indiscriminate use of sentinel node biopsy would be prohibitively cost-ineffective with each detected SN metastasis costing $700,000–$1,000,000.11 It is therefore critically important to determine what patients are appropriate candidates for more aggressive intervention.

Predictors of nodal disease have been sought largely through reviews of SN biopsy in thin melanoma. Several potential predictors of metastasis have been identified including vertical growth phase (VGP), gender, mitotic rate, Breslow thickness, Clark level, age, and tumor infiltrating lymphocytes.12–18 However, not all series supported the same factors, and some suggested no factors correlated with SN status.9,19

There are several difficulties with these systems of SN prediction. Vertical growth phase, which is recommended as an indicator by the Pigmented Lesion Group at the University of Pennsylvania is not universally reported at many centers, and many pathologists are not well trained in distinguishing VGP from radial growth phase. Similar difficulties exist in determining the Clark level of invasion in a reproducible way.20 In the current study, this lack of reproducibility may account for the loss of significance for Clark when Breslow subcategories (e.g. 0.01–0.25, 0.26–0.50, etc) were included. The degree of tumor infiltration by host lymphocytes is also measured on a somewhat subjective scale that may be reported differently by different pathologists. Mitotic rate appears to be an extremely important variable in the assessment of melanoma risk. 21–23 This variable will be included in the updated AJCC staging system, but it has not been systematically collected in many centers for very long. A study from the PLG found that this was a strong predictor of metastasis in thin melanoma,16 but in thin lesions the reported mitotic rate may vary with the proportion of the dermal component that is evaluated. Finally, ulceration is associated with both a worse outcome and greater propensity for nodal metastasis. However, this finding is very infrequent in thin melanomas. In our own series, ulceration was only seen in 2.3% of patients. This is similar to the rate reported by Gimotty of 1.2%.3 While such ulcerated lesions clearly deserve greater concern and evaluation, the rarity of this find decreases the utility of including it in a prediction scheme.

A more basic problem with prediction schemes derived from SN series, is that the patients included in the series have already been selected by the surgeon to undergo the procedure. This selection bias may preclude sufficient evaluation of potential prognostic indicators. For example, if Clark level IV invasion is used as a consistent selection criterion for SN biopsy, it is highly unlikely to be found to be predictive of nodal metastasis. The current report examines a different population: those patients treated by wide local excision alone. This greatly reduces the impact of selection bias, making evaluation of multiple potential predictors possible.

In addition, the possibility of a false-negative SN biopsy exists. At centers that are not experienced with the technique, this rate may be as high as 10% or greater.4 This may be particularly true of thin lesions, since the volume of disease in the node is often quite small. Using clinical nodal recurrence as an endpoint obviates that problem.

Other series have examined the rate of nodal recurrence among patients treated with wide local excision alone.2,4,6,25–29 These rates have varied from 4.3% to 12.0% and appear higher than the reported rates of SN positivity for the same group. However, in many of these series referral bias may have led to inclusion of cases that had been sent to a tertiary center only after recurrence, increasing the apparent rate of nodal metastasis. The series from the PLG excluded patients referred in for recurrence and found an overall rate of 4.3% and a rate of 8.6% for lesions between 0.75 and 1.00 mm. This is quite similar to the current report. They found the risk of nodal recurrence related to vertical growth phase, mitotic rate and male gender in a decision-tree analysis. Ulceration was also significant in a multivariate model.

Our predictive system for nodal metastasis in thin melanoma uses three very simple and reproducible variables to determine the risk of harboring clinically occult nodal metastases. These variables should be easily available for all melanoma patients. This risk assessment is not intended to mandate what risk level is appropriate for SN evaluation, but it allows for a better informed discussion with the newly diagnosed patient. Such information could be used to reassure extremely low-risk patients who may be anxious about the possibility of metastases, or convince patients at higher risk of the need to consider SN biopsy.

Acknowledgments

Supported in part by grant CA29605 from the National Cancer Institute and by funding from the Amyx Foundation, Inc. (Boise, ID), Berton M. Kirshner (Los Angeles, CA), Todd Kirshner (Los Angeles, CA), Mr. and Mrs. Louis Johnson, (Stanfield, AZ), Heather and Jim Murren (Las Vegas, NV), Mrs. Marianne Reis (Lake Forest, CA), and the Wallis Foundation (Los Angeles, CA).

Footnotes

Presented at the Western Surgical Association, Santa Fe, NM, November 11, 2008.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Devesa SS, Hartge P, Tucker MA. Recent trends in cutaneous melanoma incidence among whites in the United States. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93:678–683. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.9.678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McKinnon JG, Yu XQ, McCarthy WH, Thompson JF. Prognosis for patients with thin cutaneous melanoma: long-term survival data from New South Wales Central Cancer Registry and the Sydney Melanoma Unit. Cancer. 2003;98:1223–1231. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gimotty PA, Guerry D, Ming ME, et al. Thin primary cutaneous malignant melanoma: a prognostic tree for 10-year metastasis is more accurate than American Joint Committee on Cancer staging. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:3668–3676. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morton DL, Thompson JF, Cochran AJ, et al. Sentinel-node biopsy or nodal observation in melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1307–1317. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa060992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wright BE, Scheri RP, Ye X, et al. Importance of sentinel lymph node biopsy in patients with thin melanoma. Arch Surg. 2008;143:892–899. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.143.9.892. discussion 899–900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kalady MF, White RR, Johnson JL, Tyler DS, Seigler HF. Thin melanomas: predictive lethal characteristics from a 30-year clinical experience. Ann Surg. 2003;238:528–535. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000090446.63327.40. discussion 535-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Conway W, Terando A, Nicholl M, Glass E, Morton DL, Faries M. International Sentinel Node Congress. Sydney, Australia: 2008. Is lymphatic physiology to blame for the age paradox in melanoma? [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gershenwald JE, Thompson W, Mansfield PF, et al. Multi-institutional melanoma lymphatic mapping experience: the prognostic value of sentinel lymph node status in 612 stage I or II melanoma patients. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:976–983. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.3.976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wong SL, Brady MS, Busam KJ, Coit DG. Results of sentinel lymph node biopsy in patients with thin melanoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2006;13:302–309. doi: 10.1245/ASO.2006.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ranieri JM, Wagner JD, Wenck S, Johnson CS, Coleman JJ., 3rd The prognostic importance of sentinel lymph node biopsy in thin melanoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2006;13:927–932. doi: 10.1245/ASO.2006.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Agnese DM, Abdessalam SF, Burak WE, Jr, Magro CM, Pozderac RV, Walker MJ. Cost-effectiveness of sentinel lymph node biopsy in thin melanomas. Surgery. 2003;134:542–547. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6060(03)00275-7. discussion 547-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cecchi R, Buralli L, Innocenti S, De Gaudio C. Sentinel lymph node biopsy in patients with thin melanomas. J Dermatol. 2007;34:512–515. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2007.00323.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vaquerano J, Kraybill WG, Driscoll DL, Cheney R, Kane JM., 3rd American Joint Committee on Cancer clinical stage as a selection criterion for sentinel lymph node biopsy in thin melanoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2006;13:198–204. doi: 10.1245/ASO.2006.03.092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Puleo CA, Messina JL, Riker AI, et al. Sentinel node biopsy for thin melanomas: which patients should be considered? Cancer Control. 2005;12:230–235. doi: 10.1177/107327480501200404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bedrosian I, Faries MB, Guerry Dt, et al. Incidence of sentinel node metastasis in patients with thin primary melanoma (< or = 1 mm) with vertical growth phase. Ann Surg Oncol. 2000;7:262–267. doi: 10.1007/s10434-000-0262-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kesmodel SB, Karakousis GC, Botbyl JD, et al. Mitotic rate as a predictor of sentinel lymph node positivity in patients with thin melanomas. Ann Surg Oncol. 2005;12:449–458. doi: 10.1245/ASO.2005.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bleicher RJ, Essner R, Foshag LJ, Wanek LA, Morton DL. Role of sentinel lymphadenectomy in thin invasive cutaneous melanomas. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:1326–1331. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.06.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oliveira Filho RS, Ferreira LM, Biasi LJ, Enokihara MM, Paiva GR, Wagner J. Vertical growth phase and positive sentinel node in thin melanoma. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2003;36:347–350. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x2003000300009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stitzenberg KB, Groben PA, Stern SL, et al. Indications for lymphatic mapping and sentinel lymphadenectomy in patients with thin melanoma (Breslow thickness < or =1.0 mm) Ann Surg Oncol. 2004;11:900–906. doi: 10.1245/ASO.2004.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Owen SA, Sanders LL, Edwards LJ, Seigler HF, Tyler DS, Grichnik JM. Identification of higher risk thin melanomas should be based on Breslow depth not Clark level IV. Cancer. 2001;91:983–991. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sondak VK, Taylor JM, Sabel MS, et al. Mitotic rate and younger age are predictors of sentinel lymph node positivity: lessons learned from the generation of a probabilistic model. Ann Surg Oncol. 2004;11:247–258. doi: 10.1245/aso.2004.03.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Paek SC, Griffith KA, Johnson TM, et al. The impact of factors beyond Breslow depth on predicting sentinel lymph node positivity in melanoma. Cancer. 2007;109:100–108. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gimotty PA, Van Belle P, Elder DE, et al. Biologic and prognostic significance of dermal Ki67 expression, mitoses, and tumorigenicity in thin invasive cutaneous melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:8048–8056. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.0735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morton D, Hoon D, Cochran A, et al. Lymphatic mapping and sentinel lymphadenectomy for early-stage melanoma: therapeutic utility and implications of nodal microanatomy and molecular staging for improving the accuracy of detection of nodal micrometastases. Ann Surg. 2003;238:538–549. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000086543.45557.cb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Massi D, Franchi A, Borgognoni L, Reali UM, Santucci M. Thin cutaneous malignant melanomas (< or =1.5 mm): identification of risk factors indicative of progression. Cancer. 1999;85:1067–1076. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19990301)85:5<1067::aid-cncr9>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Karakousis GC, Gimotty PA, Botbyl JD, et al. Predictors of regional nodal disease in patients with thin melanomas. Ann Surg Oncol. 2006;13:533–541. doi: 10.1245/ASO.2006.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Corsetti RL, Allen HM, Wanebo HJ. Thin < or = 1 mm level III and IV melanomas are higher risk lesions for regional failure and warrant sentinel lymph node biopsy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2000;7:456–460. doi: 10.1007/s10434-000-0456-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Woods JE, Soule EH, Creagan ET. Metastasis and death in patients with thin melanomas (less than 0.76 mm) Ann Surg. 1983;198:63–64. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198307000-00012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Naruns PL, Nizze JA, Cochran AJ, Lee MB, Morton DL. Recurrence potential of thin primary melanomas. Cancer. 1986;57:545–548. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19860201)57:3<545::aid-cncr2820570323>3.0.co;2-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]