Abstract

Background

Clinical guidelines advise screening for depression in patients with diabetes. The Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) and the depression subscale of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS-D) are commonly used in primary care.

Aim

To compare the efficacy of HADS-D and PHQ-9 in identifying moderate to severe depression among primary care patients with type 2 diabetes.

Design of study

Self-report postal survey, clinical records assessed by GPs.

Setting

Seven metropolitan and rural general practices in Victoria, Australia.

Method

Postal questionnaires were sent to all patients with diabetes on the registers of seven practices in Victoria. A total of 561 completed postal questionnaires were returned, giving a response rate 47%. Surveys included demographic information, and history of diabetes and depression. Participants completed both the PHQ-9 and HADS-D. Clinical data from patient records included glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) levels and medications.

Results

The proportion of the total sample completing HADS-D was 96.8% compared with 82.4% for PHQ-9. Level of education was unrelated to responses on the HADS-D but was related to completion of the PHQ-9. Using complete data (n = 456) from both measures, 40 responders showed HADS-D scores in the moderate to severe range, compared with 103 cases identified by PHQ-9. Only 35 cases were classified in the moderate to severe category by both the PHQ-9 and HADS-D. Items with the highest proportions of positive responses on the PHQ-9 were related to tiredness and sleeping problems and, on the HADS-D, feeling slowed down.

Conclusion

It may be that the items contributing to the higher prevalence of moderate to severe depression using the PHQ-9 are due to diabetes-related symptoms or sleep disorders.

Keywords: depression, diabetes, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, Patient Health Questionnaire, sleep disturbance

INTRODUCTION

Diabetes is a major contributor to the global burden of disease and a growing number of studies show links between depression and diabetes.1–3 The negative impact depression can have on quality of life for people with diabetes, together with the increased healthcare costs of comorbid depression have been recognised.4

In the UK, the Quality and Outcomes Framework provides incentives for GPs to use validated questionnaires to identify people with depression, including those with existing heart disease or diabetes.5 The Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9)6 and the depression subscale of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS-D)7 are increasingly used to improve the identification and management of people with depression among those with diabetes or heart disease,8–10 but doctors' responses to the category scores vary, depending on which of the questionnaires is used.11,12

Several studies show that PHQ-9 and HADS-D differ in the proportion of people classified with mild, moderate, or severe depression.13,14 A previous study15 by the current authors identified the prevalence of psychological disorders among people with type 2 diabetes in Victoria, Australia, and used several indices of depression, distress, and anxiety. This study reports the results of administering both the PHQ-9 and HADS-D measures to all participants and compares the performance of each in identifying depression.

METHOD

Participants

Between February 2007 and March 2008, 1200 postal questionnaires were sent to 10 practices in rural and metropolitan Victoria, Australia to distribute to potential participants. Clinical data were recorded by practice staff. Adults with type 2 diabetes from seven general practices participated. A total of 561 completed questionnaires that could be matched with clinical records were received, giving a response rate of 46.8%.

Measures

The questionnaires asked about demographics, diabetes, and depression. Clinical data included glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c), body mass index (BMI), and medications. The depression questionnaires used were HADS-D and PHQ-9. Standard cut-off scores were used with HADS-D to classify minimal (0–7), mild (8–10), and moderate to severe (≥11) levels of depression. For PHQ-9 the cut-off scores were: minimal (0–4), mild (5–9), and moderate to severe (≥10).

Statistical analysis

Cronbach's α and corrected item-total correlations were used to examine internal consistency of items on the two depression measures. Homogeneity and structure of both scales were assessed using principal components analysis. Additional analyses included calculation of χ2, t-tests, and analysis of variance to determine relationships between clinical characteristics and depression scores (Stata version 10).

RESULTS

Sample characteristics

The sample comprised 309 males (median age 67 years) and 252 females (median age 70 years). Most were married (63%), from rural areas (75%), educated to high-school level or less (69%), and either retired or not in full-time employment (75%). Males and females in the sample did not differ significantly in age or level of education. There were no significant differences between urban and rural responders with regard to sex, age, level of education, employment status, or health concessions.

Mean duration of diabetes for the sample was 8.84 years (standard deviation = 7.35 years). About half the sample reported no diabetes complications and a quarter reported two or more complications. Most managed diabetes with oral medication only (53.7%), or no medication (27.3%), but 107 (19.1%) participants were taking insulin or insulin plus oral medication. Previous history of depression was reported by 161 participants; 48 of these had had an episode within the previous 12 months, and 59 within 1–5 years. Current antidepressant usage was reported by 65 of the 239 participants who had some depression.

How this fits in.

Clinical guidelines recommend screening patients with diabetes for depression because of poor clinical outcomes when there is comorbid depression. The depression subscale of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS-D) and the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) are commonly used for screening in primary care, but there is poor agreement between the measures in categorising moderate to severe depression. When used to assess depression among patients with type 2 diabetes, PHQ-9 may overestimate moderate to severe depression because of items that include symptoms of diabetes or sleep disorders. HADS-D is a better screening tool for depression in patients with diabetes.

Responses to HADS-D and PHQ-9 depression measures

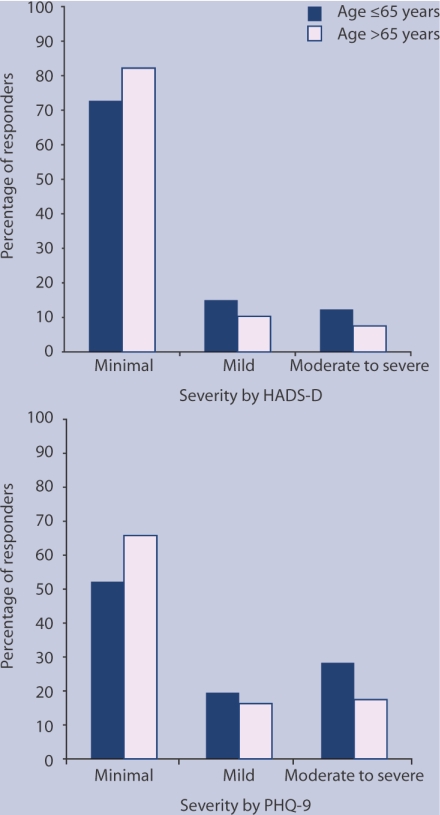

A higher proportion of the sample completed HADS-D (96.8%) than PHQ-9 (82.4%; P<0.001). Of the 561 patients who completed questionnaires, six (1.1%) did not complete HADS-D but completed PHQ-9, and 87 (15.5%) had missed items on PHQ-9 but completed HADS-D. In total, 456 (81.3%) participants completed both measures in full. Response rates on both measures related to age: older people (that is, those aged >65 years) had a lower response rate than their younger counterparts on both measures: HADS-D, P = 0.013; PHQ-9, P<0.001 (Figure 1). Level of education was unrelated to responses given on HADS-D, but was related to those on PHQ-9 (P = 0.023), with lower response rates shown for lower levels of education (that is, high-school education or less).

Figure 1.

Distribution of depression severity among patients with diabetes assessed on the depression subscale of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS-D, n = 543) and the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9, n = 462).

Distribution of missing responses

The number of missing responses on individual HADS-D items ranged from five to 11 (0.9% and 2.0% of the total sample respectively). Items with close to 2% of missing responses on HADS-D were: H3 ‘I feel cheerful’ (2%) and H1 ‘I still enjoy the things I used to enjoy’ (1.8%).

On the individual PHQ-9 items, the number of missing responses ranged from 43 to 58 (7.7% and 10.3% of the total sample respectively). PHQ-9 items with close to 10% of missing responses were: P1 ‘Little interest or pleasure in doing things’ (10.3%); P2 ‘Feeling down, depressed, or hopeless’ (9.8%); and P5 ‘Poor appetite or overeating’ (9.8%).

Reliability analysis

Cronbach's α coefficients and item-total correlations are given in Appendix 1. Coefficient α for both scales are acceptable and comparable with previous studies of these measures in samples from primary care. All item-total correlations within both measures exceed 0.4 (HADS-D range 0.43 to 0.72, PHQ-9 range 0.56 to 0.76). The figures given for Cronbach's α if items are deleted show that removal of any of the individual items on HADS-D or PHQ-9 would not substantially improve the internal reliabilities of the scales.

Factor structure

Factor analysis of the separate scales used principal components. For HADS-D, the analysis gave one factor with an eigenvalue of 3.49, which explained 49.8% of the total variance. For PHQ-9, a single factor was obtained with an eigenvalue of 5.1, explaining 56.8% of the total variance. Most items within each scale had a substantial loading on the primary factor (HADS-D range 0.56 to 0.83, PHQ-9 range 0.66 to 0.83).

A factor analysis including all items from both HADS-D and PHQ-9 was also performed (Appendix 2.) The analysis yielded two factors with eigenvalues of 7.8 and 1.2 respectively, which together explained 56.5% of the total variance. Items with substantial loadings (>0.65) on factor 1 were: H4 ‘I feel as if I am slowed down’; P3 ‘Trouble falling or staying asleep, or sleeping too much’; P4 ‘Feeling tired or having little energy’; and P5 ‘Poor appetite or overeating’. The PHQ-9 items P1 ‘Little interest or pleasure in doing things’ and P2 ‘Feeling down, depressed, or hopeless’, loaded on both factors.

Comparison of severity ratings between depression measures

The correlation between HADS-D and PHQ-9 was significant at the 0.001 level (r = 0.78). The threshold scores for mild and moderate to severe depression were 8 and 11 respectively for HADS-D, and 5 and 10 respectively for PHQ-9. Although 117 (21.5%) of those who completed HADS-D had some depression (score >8), 186 (40.3%) of those who completed PHQ-9 showed depression (score >5). There were no significant sex differences across severity categories on either of the measures, but there were age differences. A higher proportion of those aged 65 years and under (compared with those over 65 years) reported moderate to severe depression on both HADS-D (P = 0.029) and PHQ-9 (P = 0.008).

The cross tabulation of HADS-D and PHQ-9 scores in Table 1 shows a lack of concurrence of distribution within severity cut-offs. Of the 103 cases identified by PHQ-9 as moderate to severe, 35 were in the same category on HADS-D, but 31 had minimal depression on HADS-D. Of the 40 identified by HADS-D in the moderate to severe range, PHQ-9 classified 35 as moderate to severe and two cases as minimal depression.

Table 1.

Cross tabulation of scores across depression measures and severity ratings reported by primary care patients with type 2 diabetes.

| PHQ-9 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minimal (0–4) | Mild (5–9) | Moderate to severe (≥10) | Total | |

| HADS-D | n | n | n | n |

| Minimal (0–7) | 262 | 68 | 31 | 361 |

| Mild (8–10) | 7 | 11 | 37 | 55 |

| Moderate to severe (≥11) | 2 | 3 | 35 | 40 |

| Total | 271 | 82 | 103 | 456 |

HADS-D = depression subscale of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. PHQ-9 = Patient Health Questionnaire.

Distribution of expected and observed item responses by severity cut-offs

On both measures, the maximum possible rating for each item was 3, indicating highest frequency of occurrence (this was ‘nearly all the time’ on HADS-D, and ‘nearly every day’ on PHQ-9). The expected proportion of maximum ratings for each item within each total score, y = a/b, was calculated by determining, for each possible total score, (a) the number of ways in which the total score could be arrived at while keeping a particular item fixed at the maximum and (b) the overall number of ways in which the total score could be arrived at. Means of expected proportions were calculated for each depression severity to be compared with the observed proportion by using 95% confidence intervals.

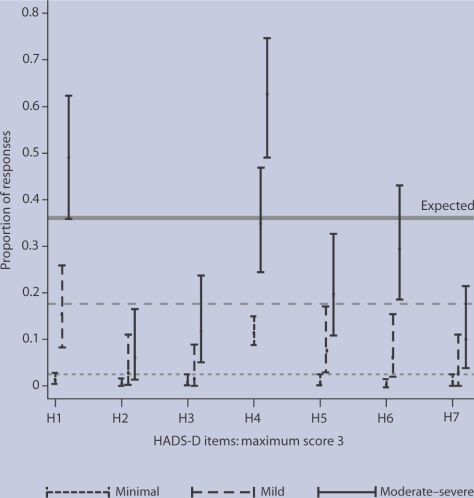

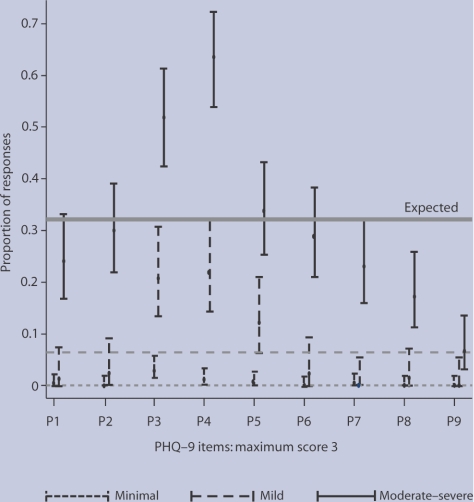

Figures 2 and 3 show the distribution of item responses by severity cut-offs on HADS-D and PHQ-9 respectively. Only one HADS-D item and two PHQ-9 items showed over 50% of moderate to severe category responses on the maximum rating: H4 ‘I feel as if I am slowed down’; P3 ‘Trouble falling or staying asleep, or sleeping too much’; and P4 ‘Feeling tired or having little energy’. The proportions of observed responses to these items were significantly higher than their corresponding expected responses.

Figure 2.

Distribution of responses for maximum score 3 on individual items of the depression subscale of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS-D) by depression severity: minimal n = 426, mild n = 66, moderate to severe n = 51. H1–H7 refers to individual question items (see Appendices 1 and 2).

Figure 3.

Distribution of responses for maximum score 3 on individual items of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) by depression severity: minimal n = 276, mild n = 82, moderate to severe n = 104. P1–P9 refers to individual question items (see Appendices 1 and 2).

Clinical characteristics and depression scores

Table 2 shows the mean scores on the two depression measures by diabetes and depression clinical characteristics. Duration of diabetes was related to both HADS-D (P<0.001) and PHQ-9 (P = 0.026) scores, with greater duration (≥5 years) linked to higher depression. A greater number of diabetes complications was related to higher scores on HADS-D (P<0.001) and PHQ-9 (P<0.001). Use of medication, either oral or oral plus insulin, was related to higher HADS-D scores (P<0.001) and higher PHQ-9 scores (P = 0.004). Depression scores were unrelated to recent HbA1c levels in patients' clinical records. Obesity (BMI >30 kg/m2) was related to higher depression on both HADS-D (P = 0.002) and PHQ-9 (P = 0.001). Participants who had a previous episode of depression showed higher scores on HADS-D (P<0.001) and PHQ-9 (P<0.001), as did those being prescribed antidepressants at the time of the study (HADS-D, P<0.001; PHQ-9, P<0.001).

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics and depression scores

| HADS-D | PHQ-9 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Mean | SD | n | Mean | SD | |

| Diabetes duration | ||||||

| <5 years | 170 | 3.62 | 3.55 | 151 | 4.56 | 5.85 |

| ≥5 years | 345 | 5.25 | 3.97 | 290 | 5.94 | 6.32 |

| Diabetes complications | ||||||

| None | 266 | 3.79 | 3.61 | 233 | 4.35 | 5.63 |

| One | 146 | 4.94 | 3.51 | 121 | 5.35 | 5.89 |

| Two or more | 131 | 6.20 | 4.24 | 108 | 7.95 | 6.67 |

| Diabetes regimen | ||||||

| No medication | 148 | 3.73 | 3.59 | 133 | 4.56 | 5.78 |

| Oral only | 249 | 4.75 | 3.90 | 244 | 5.28 | 6.14 |

| Insulin or insulin + oral | 101 | 5.89 | 3.82 | 85 | 7.34 | 6.21 |

| Recent HbA1c | ||||||

| >7 | 146 | 4.86 | 4.19 | 132 | 6.11 | 6.87 |

| ≤7 | 214 | 4.53 | 3.72 | 182 | 5.26 | 5.84 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | ||||||

| ≤30 | 221 | 4.02 | 3.53 | 189 | 4.26 | 5.34 |

| >30 | 217 | 5.13 | 4.05 | 198 | 6.39 | 6.54 |

| Previous depression | ||||||

| Yes | 158 | 6.49 | 4.48 | 143 | 8.82 | 6.83 |

| No | 385 | 3.94 | 3.31 | 319 | 3.94 | 5.09 |

| Current antidepressant medication | ||||||

| Yes | 63 | 7.38 | 4.48 | 59 | 10.78 | 7.60 |

| No | 480 | 4.33 | 3.64 | 403 | 4.67 | 5.45 |

HADS-D = depression subscale of Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. HbA1c = glycosylated hemoglobin. PHQ-9 = Patient Health Questionnaire.

DISCUSSION

Summary of main findings

Both the HADS-D and PHQ-9 measures demonstrated acceptable reliability and robustness of factor structure. Both questionnaires can be self-administered and completed within a few minutes, but HADS-D seems to be a better tool for self-administered screening than PHQ-9. This is because response rates for PHQ-9, but not HADS-D, appear to be influenced by level of education and because the distribution of responses on individual items on PHQ-9 showed more missing responses. Some 10% were missing on the first two items; these make up the PHQ-2 test, which is sometimes used for rapid screening.

Using the recommended severity scores, the PHQ-9 tool (scores >5) identified about 20% more patients as having depression compared with HADS-D (scores >8). Only about a third (34%) of the cases identified by PHQ-9 in the moderate to severe depression category was located in the same category by HADS-D.

This study confirms the poor agreement between PHQ-9 and HADS-D measures for classifying severity of depression. The explanation for the higher proportion categorised as moderate to severe by

PHQ-9 comes from responses to two items concerned with sleeping problems and tiredness or having little energy, which received a rating 3 (experienced nearly every day) by over 50% of the sample. Similarly, the ‘feel slowed down’ item on HADS-D was endorsed by over 60% of those in the moderate to severe category with the maximum rating.

The factor analysis of the pooled HADS-D and PHQ-9 items found the HADS-D item ‘feel slowed down’, together with the PHQ-9 items concerning sleeping, tiredness, and poor appetite or overeating, showed high loadings on the first factor. These results suggest somatic symptoms and behaviours related to diabetes may be contributing to the depression scores, particularly when measured using PHQ-9.

Strengths and limitations of the study

This is a singular comparison of responses to PHQ-9 and HADS-D measures among participants with diagnosed type 2 diabetes in primary care, providing a snapshot of what GPs are likely to encounter in everyday practice. The study demonstrates that both measures can be used for screening through self-completion of a postal questionnaire, but that HADS-D appears to provide a more accurate view. The prevalence of depression with HADS-D is similar to other epidemiological studies in the region.15,16

Gold standards such as the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV17 were beyond the scope of the study but could probably have further clarified which measure performed better for screening. The sample was selected because of type 2 diabetes status. This study did not have a comparison sample that had depression but not diabetes, but the factor analysis of pooled HADS-D and PHQ-9 items for this group of patients with diabetes showed a different pattern of item loadings when compared with a similar analysis of primary care patients without diabetes in Sweden.14

Comparison with existing literature

The psychometric properties of the HADS-D and PHQ-9 depression measures in this Australian population with type 2 diabetes are similar to those reported in samples of patients in primary care in the UK11,13 and Sweden.14 Comparing the two measures, PHQ-9 identified more than twice as many in the moderate to severe category as HADS-D, a pattern that has been noted in other studies.11,13,14 Other authors reported that these large differences in categorisation are not reflected in prescribing because GPs take other things, such as history of depression, into account along with the questionnaire score.11,12

One study showed that although PHQ-9 categorised 83.5% of patients as having moderate to severe depression compared with 55% by HADS-D, prescription rates were almost identical at 79%, and referral rates at 23.7% and 20.3% respectively.11 The study also reported lower treatment rates among patients with heart disease or diabetes.

Implications for clinical practice and future research

Patients appear to value these self-report measures, which they regard as objective and offering them a means to express how they feel. GPs, however, may see depression questionnaires simply as guides to decision making.12 GPs appear more inclined to accept a HADS-D score at face value than a PHQ-9 one. This is reflected in the similar rates of prescribing and referral, even though PHQ-9 seems to be used three times more often than HADS-D.11 Perhaps GPs are taking into account the fact that PHQ-9 overestimates severity because it includes somatic symptoms that GPs are willing to attribute to the underlying condition rather than depression.

The two items forming PHQ-2 seem particularly unsuitable for screening patients with diabetes. They both had a high proportion of missing responses and so could not be used to classify patients with diabetes who also have moderate to severe depression.

There has been considerable progress in screening people with diabetes for depression.8,9 The current results suggest that PHQ-9 overestimates depression among patients with diabetes because it contains questions about tiredness, sleeping problems, and eating patterns that are common in diabetes. There is a complicated relationship between obesity, diabetes, depression, and obstructive sleep apnoea.18,19 Sleep disturbances in diabetes are frequently due to nocturia, neurogenic pain, and other causes.20,21 The PHQ-9 questions about over eating or under eating, and the somatic symptom of tiredness may be accounted for by diabetes itself, or by sleep disturbances including obstructive sleep apnoea, and could account for the high classification rate for moderate to severe depression.

HADS-D is probably a better screening instrument for patients with type 2 diabetes. If using PHQ-9, GPs should assess each of the patient's nine answers and consider causes of sleep disorder or tiredness besides depression. Focusing on individual responses, rather than total scores, may prove more effective in reducing suffering and accurately identifying the problems encountered by the patient.22

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the general practices of Colac, Hamilton Medical Group, Moe, Pascoe Vale, Preston, Reservoir, and Warracknabeal for their help with this study.

Appendix 1. Cronbach's α and item-total correlations of the HADS-D and PHQ-9.

| Scale and items | Item-total correlations | Coefficient α (95% CI) | Cronbach's α if item deleted | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HADS-D (n = 543) | 0.83 (0.80 to 0.85) | |||

| H1 | Still enjoy things | 0.63 | 0.79 | |

| H2 | Can laugh | 0.59 | 0.80 | |

| H3 | Feel cheerful | 0.59 | 0.80 | |

| H4 | Feel slowed down | 0.50 | 0.82 | |

| H5 | Lost interest in appearance | 0.57 | 0.80 | |

| H6 | Look forward with enjoyment | 0.72 | 0.78 | |

| H7 | Can enjoy book/radio/TV | 0.43 | 0.82 | |

| PHQ-9 (n = 462) | 0.90 (0.88 to 0.91) | |||

| P1 | Little interest or pleasure in doing things | 0.76 | 0.88 | |

| P2 | Feeling down, depressed, hopeless | 0.75 | 0.88 | |

| P3 | Trouble sleeping or sleeping too much | 0.66 | 0.89 | |

| P4 | Feeling tired or having little energy | 0.75 | 0.88 | |

| P5 | Poor appetite or overeating | 0.63 | 0.89 | |

| P6 | Feeling bad about self, or a failure, or have let self or family down | 0.71 | 0.88 | |

| P7 | Trouble concentrating, such as reading newspaper or watching TV | 0.66 | 0.89 | |

| P8 | Moving or speaking more slowly, or being restless, moving more than usual | 0.61 | 0.89 | |

| P9 | Thoughts of self-harm | 0.56 | 0.90 | |

HADS-D = depression subscale of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. PHQ-9 = Patient Health Questionnaire.

Appendix 2. Factor analysis loadings with varimax rotation of pooled items from HADS-D and PHQ-9 measures of depression.

| Scale | Item | Factor 1 | Factor 2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| HADS-D | |||

| H1 | Still enjoy things | 0.594 | 0.338 |

| H2 | Can laugh | 0.371 | 0.631 |

| H3 | Feel cheerful | 0.343 | 0.670 |

| H4 | Feel slowed down | 0.752 | 0.046 |

| H5 | Lost interest in appearance | 0.560 | 0.299 |

| H6 | Look forward with enjoyment | 0.562 | 0.568 |

| H7 | Can enjoy book/radio/TV | 0.073 | 0.664 |

| PHQ-9 | |||

| P1 | Little interest or pleasure in doing things | 0.610 | 0.568 |

| P2 | Feeling down, depressed, hopeless | 0.581 | 0.532 |

| P3 | Trouble sleeping or sleeping too much | 0.657 | 0.306 |

| P4 | Feeling tired or having little energy | 0.795 | 0.278 |

| P5 | Poor appetite or overeating | 0.704 | 0.237 |

| P6 | Feeling bad about self, or a failure, or have let self or family down | 0.531 | 0.571 |

| P7 | Trouble concentrating, such as reading newspaper or watching TV | 0.267 | 0.768 |

| P8 | Moving or speaking more slowly, or being restless, moving more than usual | 0.296 | 0.648 |

| P9 | Thoughts of self-harm | 0.203 | 0.706 |

HADS-D = depression subscale of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. PHQ-9 = Patient Health Questionnaire. Figures in bold are items with high (>0.500) loadings on each factor.

Funding body

Department of Human Services Victoria (Ref No ADF/05/8456, Project ChD/2).

Ethics committee

Ethical approval was obtained from DHS Victoria Human Research Ethics Committee (Application No 04/07).

Competing interests

The authors have stated that there are none.

Discuss this article

Contribute and read comments about this article on the Discussion Forum: http://www.rcgp.org.uk/bjgp-discuss

REFERENCES

- 1.Anderson RJ, Freedland KE, Clous RE, Lustman PJ. The prevalence of comorbid depression in adults with diabetes: a meta-analysis. Diabetes Care. 2001;24:1069–1078. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.6.1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ali S, Stone MA, Peters JL, et al. The prevalence of co-morbid depression in adults with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabet Med. 2006;23:1165–1173. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2006.01943.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dunbar JA, Reddy P, Davies-Lameloise N, et al. Depression: an important comorbidity with metabolic syndrome in a general population. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:2368–2373. doi: 10.2337/dc08-0175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Egede LE, Zheng D, Simpson K. Comorbid depression is associated with increased health care use and expenditures in individuals with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:464–470. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.3.464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.NHS Employers, the General Practitioners' Committee. Quality and outcomes framework guidance for GMS contract 2009/10: delivering investment in general practice. 2009. March http://www.bma.org.uk/images/qof0309_tcm41-184025.pdf (accessed 6 May 2010)

- 6.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67:361–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lin EH, Katon W, Von Korff M, et al. Relationship of depression and diabetes self-care, medication adherence, and preventive care. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:2154–2160. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.9.2154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Katon WJ, Von Korff M, Lin EH, et al. The pathway study: randomized trial of collaborative care in patients with diabetes and depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:1042–1049. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.10.1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reddy P, Dunbar JA, Morgan M, O'Neil A. Coronary heart disease and depression: getting evidence into clinical practice. Stress and Health. 2008;24:223–230. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kendrick T, Dowrick C, McBride A, et al. Management of depression in UK general practice in relation to scores on depression severity questionnaires: analysis of medical record data. BMJ. 2009;338:b750. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b750. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dowrick C, Leydon GM, McBride A, et al. Patients' and doctors' views on depression severity questionnaires incentivised in UK quality and outcomes framework: qualitative study. BMJ. 2009;338:b663. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b663. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cameron IM, Crawford JR, Lawton K, Reid IC. Psychometric comparison of PHQ-9 and HADS for measuring depression severity in primary care. Br J Gen Pract. 2008;58:32–36. doi: 10.3399/bjgp08X263794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hansson M, Chotai J, Nordström A, Bodlund O. Comparison of two self-rating scales to detect depression: HADS and PHQ-9. Br J Gen Pract. 2009 doi: 10.3399/bjgp09X454070. DOI: 10.3399/bjgp09X454070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reddy P, Dunbar J. Type 2 diabetes and depression: Assessing the prevalence in Victoria and identifying effective public health interventions. Melbourne: Department of Human Services Victoria; 2008. http://www.greaterhealth.org/media/resources/EPI_FINAL_REPORT-2.pdf (accessed 14 Dec 2009) [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kilkkinen A, Kao-Philpot A, O'Neil A, et al. Prevalence of psychological distress, anxiety and depression in rural communities in Australia. Aust J Rural Health. 2007;15:114–119. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1584.2007.00863.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID-I) Arlington VA: American Psychiatric Press Inc; 1995. Clinical Version, User's guide. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tasali E, Mokhlesi B, Van Cauter E. Obstructive sleep apnea and type 2 diabetes: interacting epidemics. Chest. 2008;133:496–506. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-0828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tuomilehto H, Peltonen M, Partinen M, et al. Sleep duration, lifestyle intervention, and incidence of type 2 diabetes in impaired glucose tolerance: The Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:1965–1971. doi: 10.2337/dc08-1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sridhar GR, Madhu K. Prevalence of sleep disturbance in diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 1994;23:183–186. doi: 10.1016/0168-8227(94)90103-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Knutson KL, Ryden AM, Mander BA, Cauter EV. Role of sleep duration and quality in the risk and severity of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1768–1774. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.16.1768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dowrick C. Reasons to be cheerful? Reflections on GPs' responses to depression. Br J Gen Pract. 2009;59:636–637. doi: 10.3399/bjgp09X454025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]