Abstract

There is an urgent need for new strategies to combat infectious diseases in developing countries. Many pathogens have evolved to elude immunity and this has limited the utility of current therapies. Additionally, the emergence of co-infections and drug resistant pathogens has increased the need for advanced therapeutic and diagnostic strategies. These challenges can be addressed with therapies that boost the quality and magnitude of an immune response in a predictable, designable fashion that can be applied for wide-spread use. Here, we discuss how biomaterials and specifically nanoscale delivery vehicles can be used to modify and improve the immune system response against infectious diseases. Immunotherapy of infectious disease is the enhancement or modulation of the immune system response to more effectively prevent or clear pathogen infection. Nanoscale vehicles are particularly adept at facilitating immunotherapeutic approaches because they can be engineered to have different physical properties, encapsulated agents, and surface ligands. Additionally, nanoscaled point-of-care diagnostics offer new alternatives for portable and sensitive health monitoring that can guide the use of nanoscale immunotherapies. By exploiting the unique tunability of nanoscale biomaterials to activate, shape, and detect immune system effector function, it may be possible in the near future to generate practical strategies for the prevention and treatment of infectious diseases in the developing world.

Keywords: Immunotherapy, Chronic disease, Vaccine, Prophylactic therapy, Nanoparticle, Biomaterials, Adjuvant, Global health

1. Introduction

Throughout history, diseases caused by infectious pathogens have posed significant challenges. These health challenges are most acute in countries described as “low income” or “developing”. In developing countries, a large portion of the population lives below the poverty line and infectious diseases remain a major contributor to both morbidity and mortality. The World Health Organization reported in 2004 that four of the top ten causes of death in low income countries were attributed to infectious diseases (diarrheal diseases, HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, and malaria) [1] (Fig. 1). The lack of adequate prophylactic or therapeutic medicines for infectious diseases in those areas can partly be attributed to 1) socioeconomic barriers that limit the access of therapeutics to the affected populations and 2) the technological dearth of available and effective therapeutics that prevent or alleviate disease progression. The technological deficiency is especially transparent when compared to the advances in new therapeutics for diseases endemic in developed countries. Clearly, there is an urgent need to translate these new understandings into safe, stable, and effective technologies that can be applied worldwide.

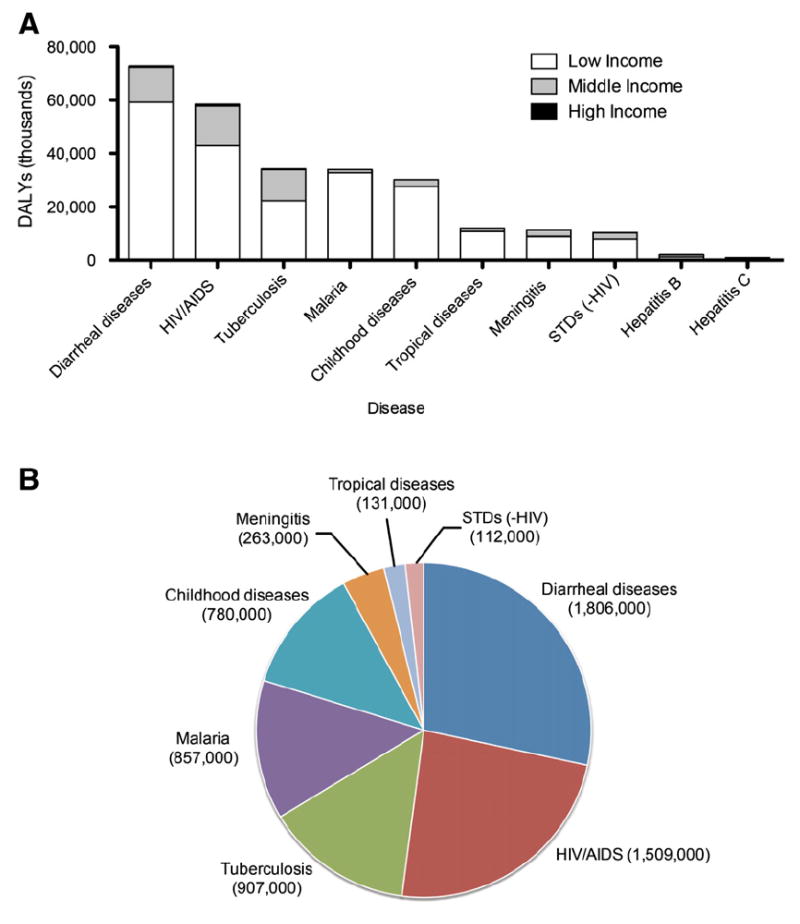

Fig. 1.

Disease burden of infectious disease in low income countries; statistics adapted from the World Health Organization [1]. A. Infectious disease burden distribution by income group, as measured by disability-adjusted life years (DALYs). A DALY measures years of healthy life lost due to premature mortality. Income levels are based on the gross national income per capita, and are grouped as low income (<US$825), middle income (US$826–US$10,065), and high income (>US $10,066) nations. B. Mortality due to infectious diseases in low income nations (<US$825).

The human immune system has evolved to combat a broad range of infectious pathogens, yet its resilient and adaptive power remains to be exploited to its full potential for neutralizing new and evolving infectious diseases. Indeed, vaccines are one of the greatest breakthroughs in medical history because of the utility of harnessing individual immune responses against infectious agents. The durability of this technology is proof of its power. However, the production of vaccines for pathogens endemic in the developing world such as HIV and malaria has proved much more complex. Part of the problem has been the unavailability of novel strategies that trigger immunity in predictable and designable ways. New advances in the construction of nanoscale drug delivery systems that target immune system cells promise to add more value to the already established successes of prophylactic vaccines and active immunotherapy. Nanoscale drug delivery systems can be readily exploited for modulating the immune system. These nanotechnology-based systems can be modified to target specific cells of the immune system and deliver chemotherapeutic or immunomodulatory agents that can prime and activate innate and antigen-specific memory immune responses. This immunomodulatory capability of nanotechnology provides a novel means for preventing or treating outstanding global infectious diseases. Here we discuss the technical perspective of how immunomodulatory nanotechnology systems can be used to improve infectious disease outcome. New insights in immunology paired with innovations on the nanoscale are now leading to extraordinary opportunities for improving health worldwide, especially in resource limited environments.

1.1. The immune system is a multifaceted, tunable defense network

A remarkable feature about the immune system is its ability to recognize infectious agents with exquisite specificity and its plasticity to mount a response that is specifically tailored for different pathogens. This section will briefly describe the major cellular interactions involved in the immune response, and how these responses are influenced by the tissue-specific site of immune potentiation. By understanding the multiple avenues in which immunity is influenced, one can design new vaccines and therapies that stimulate the immune response to more favorably combat infectious pathogens.

1.1.1. Cooperation between the innate and adaptive immune system

The immune system is a complex network of cells and molecules that coordinate responses against infectious agents while maintaining tolerance to self-antigen. The immune response consists of two interrelated arms: innate immunity and adaptive immunity. Innate immunity is the initial response against pathogen challenge, in which pathogen recognition and immune response is triggered through pathogen associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) which are recognized by pathogen recognition receptors (PRRs) on the host cell. The role of PRRs and PAMPs in innate immunity has been extensively reviewed elsewhere [2-5]. PAMPs are conserved molecular motifs that are commonly expressed on microorganisms, and include molecules such as flagellin, lipopolysaccharides, or double-stranded RNA. The PRRs are evolutionary conserved recognition receptors that are contained within the germ line of cells. Binding of PRRs with their cognate PAMPs initiates the innate clearance of cells through a number of mechanisms such as opsonization, complement activation, acute inflammation, host-derived antimicrobial compounds, or phagocytosis.

In concert with the innate response, the adaptive immune response serves as a second-line of defense against pathogens. Adaptive immunity leads to the generation of antigen-specific memory responses via molecular recognition by the T and B cell receptors. Unlike the PRRs, the antigen specificity of the T and B cell receptors are randomly generated to yield an extensive repertoire with great diversity. T and B cell responses lead to the generation of pathogen specific antibody responses, cytolytic attack of infected cells by T cells, and overall enhancement of immune responses against pathogen. Unlike the innate immune response, triggering the adaptive immune response leads to the generation of long-lasting, antigen-specific memory T and B cells, which can be rapidly activated to clear pathogen upon future infection challenge. This long-lasting memory response is the basis for which vaccination is possible.

A hallmark of the cooperation between the innate and adaptive immune response is the participation of dendritic cells. Antigen presentation is the process in which pathogens such as a bacteria or viruses are ingested and processed by antigen presenting cells for stimulation of antigen specific T cells. Of the different antigen presenting cells (B cells, macrophages, and dendritic cells), dendritic cells are the most effective in presenting antigen. Furthermore, dendritic cell interactions with antigen specific T cells can influence the maturation and differentiation of T cells.

For example, dendritic cells can activate naïve CD4 T cells, which can then differentiate into one of several distinct CD4 T cell specific subsets that produce unique cytokines and initiate special effector functions. The activation of naïve CD4 T cells can lead to CD4 T cell differentiation into a Th1, Th2, Th17, T regulatory (Treg), or T follicular helper (TFH) cell phenotype. Th1 cells can produce IFN-γ and TNF-α cytokines, which mediate protection against intracellular pathogens, whereas Th2 cells produce IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 cytokines, which are important in generating immune responses to extracellular and helminthic infections. Th17 cells are characterized by the production of the proinflammatory cytokine IL-17, while Treg cells are involved in maintaining tolerance for self-antigen. TFH cells engage B cells in the lymph nodes and spleen and stimulate B cells to produce antibodies. The T cell commitment to differentiate into one of these subsets is influenced by inflammatory signals provided by dendritic cells and the local tissue environment. Similarly, CD8 T cells and B cells also have analogous diversity in their cytokine profile and phenotypic tropism. This complex network of immune cell interactions is depicted in Fig. 2. The activation state is also another important parameter that can characterize T and B cells. T and B cell activation state can be classified as naïve, activated, or memory and describes the initiation or maintenance of an adaptive response against pathogens.

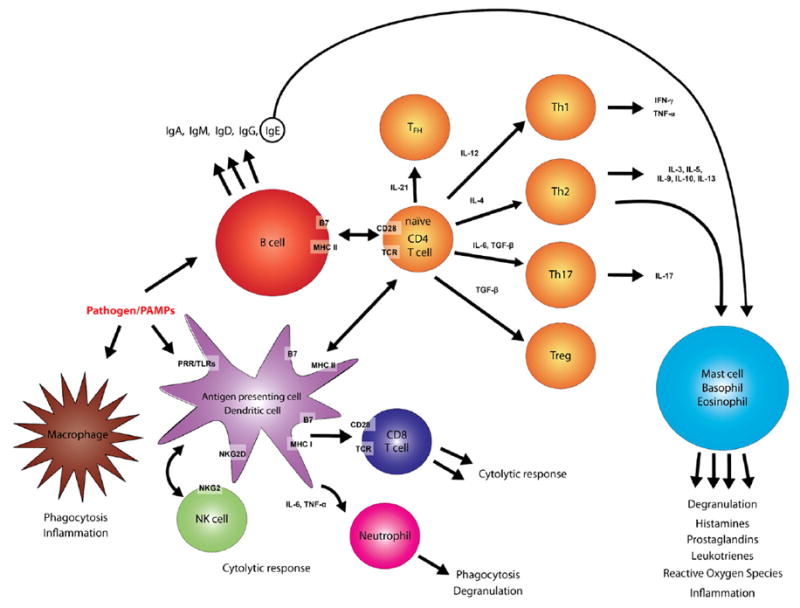

Fig. 2.

Immune system interactions. The immune system consists of several cellular interactions that lead to different functional responses by different immune cells. Numerous cell surface receptor–ligand interactions, cytokines, and inflammatory molecules coordinate and affect the immune response. Antigen presenting cells such as dendritic cells can interact with CD8 T cells to stimulate cellular (cytolytic) immune responses, or with CD4 T cells to prime humoral (antibody) based responses. A CD4 T cell can differentiate into a variety of effector subsets, which include those that stimulate B cells to produce antibodies or those that help activate other immune clearance and regulatory processes.

1.1.2. Route of pathogen entry shapes the immune response

In addition to immune cellular interactions that lead to unique phenotypes, the initial site of pathogen entry into the host is another means in which the immune response is shaped and altered. Pathogens can enter a host through a mucosal surface or through a cutaneous skin/blood route (Fig. 3). The mucosal surfaces include the lining of the respiratory, gastrointestinal, and urogenital tracts as well as the ocular surface. Many diseases including HIV, tuberculosis, enteric pathogens, and herpes are predominantly transmitted at the mucosal surface. Other pathogens, particularly insect vector transmitted diseases like malaria and leishmaniasis, enter through the skin and blood. The site of pathogen entry can tune the nature of the adaptive immune response, because different pathogen entry sites contain phenotypically distinct populations of immune cells in different physiological environments. The mucosal surfaces are typically characterized by a layer of mucus, a heterogeneous viscous fluid, that overlays an epithelial layer. Within this epithelial layer are heterogeneous populations of immune cells, including specialized tissue-specific dendritic cells, macrophages, granulocytes, and lymphocytes. On the other hand, the cutaneous skin lacks this mucus and has different types of resident immune cells within the dermal epithelial cells. In particular, dendritic cell populations are highly variable between different organs and tissues and can have very different phenotypes. In the skin, Langerhans dendritic cells are more efficient at priming cellular immunity whereas intestinal-resident dendritic cells can more efficiently prime humoral immunity [6].

Fig 3.

Human body entry routes for infectious pathogen. Pathogens can enter the body via a cutaneous/blood route or through the mucosal surfaces. The cutaneous/blood route involves pathogen penetration through the skin and into the blood stream. This cutaneous penetration can occur by insect bites (such as mosquitoes, sandflies, and flies), through the use of contaminated medical supplies, or when the pathogen directly penetrates through the epidermis. The mucosal surface consists of three main tracts: the respiratory, the oral (gastrointestinal), and the urogenital (reproductive). The ocular route is also another mucosal surface. Some pathogens, such as HIV and hepatitis B and C, can enter the body through more than one route.

Because of the inherent differences between the mucosal and cutaneous routes, different immune responses are developed for mucosal and cutaneous initiated infections. Mucosal immunity is characterized by the presence of IgA antibody in addition to local antigen-specific effector memory lymphocytes. For pathogens that enter through skin and blood, the immune response predominantly consists of IgG antibody and central memory lymphocytes disseminated throughout the peripheral lymphatic organs. These different immune responses can have a direct impact on the success of vaccination and protective immunity. For example, it has been recently suggested that HIV vaccines may be more effective when administered at mucosal sites, because resident mucosal memory T cells are generated and would more readily prevent HIV infection at the mucosal surfaces during sexual transmission [7]. Thus, the site of initial antigen challenge can modulate the tropism and effectiveness of the adaptive immune response and the residence of memory cell populations.

1.2. Immunomodulatory nanoparticles for the advancement of global health

New innovations in vaccines and therapeutics that also improve patient compliance can significantly improve infectious disease treatment. The failure to complete a therapeutic regimen that lasts several days to months can lead to incomplete therapeutic benefit and the potential generation of drug resistant pathogens. Issues with patient compliance are exacerbated by the high cost of existing therapeutics, the lack of ready access to a health care setting where the therapeutic is administered, and the patient’s economic opportunity cost and inconvenience of having to travel to a health care setting. The poor stability of bioactive agents and the lack of adequate distribution networks further compound these challenges. Patient compliance can be substantially improved if therapies were more potent, cheaper, and required less rigorous or less frequent dosing regimens. These criteria are especially key for developing vaccines and therapies for diseases such as malaria or HIV, which are currently managed only through strict compliance to a rigorous therapeutic regimen.

Nanoparticles used as novel immunotherapeutic platforms are attractive for several reasons. First, these systems can encapsulate a high density of bioactive compounds that can stimulate immunity against infection. Second, these systems can be fabricated from materials that can release encapsulated compounds in a sustained fashion over several days to months. Finally, because of the flexibility over their synthesis and formulation, these systems can be extensively modified to enhance their bioactivity or transport to specific cells and organs within the body. While substantial progress has already been made in delivering affordable and effective therapeutics to resource-limited environments, opportunities exist for further improvement using nanoscale drug delivery systems. For example, the Institute for One World Health has been instrumental in delivering the antibiotic paromomycin to Bihar state in India for the treatment of visceral leishmaniasis, a fatal vector-borne parasitic disease [8]. While this therapy has been an improvement over previous approaches, it is not without its limitations. Treatment requires daily administration of the injectable drug for 21 days and there is currently no vaccine to protect against this disease. Nanocarrier-based systems that can overcome this limitation would therefore be an obvious advantage over free drug delivery.

An additional advantage of encapsulating therapeutic agents inside nanoparticles is the potential to enhance their stability during transport across extreme temperature environments. This stability is critical in areas that lack reliable cold-storage (2 °C to 8 °C). Some nanocarrier formulations can be lyophilized to a dry form, which aids in preserving the therapeutic for long-term storage across a wide temperature range (0 °C to 40 °C) [9,10]. The protection afforded by encapsulation into a nanoparticle extends to enhancing the agent’s biodistribution within the body after its administration, because many drug delivery administration routes such as the gastrointestinal tract are caustic environments for labile compounds. For example, plasmid DNA incorporated into polymeric particles has been shown to protect against in vivo nuclease degradation [11]. This protection can facilitate delivery of therapeutic nucleic acids, which are generally cheaper to produce than recombinant proteins.

Biocompatible nanodelivery systems can be composed of natural or synthetic, and degradable or nondegradable polymers. Lipid-based formulations and viral vectors are also commonly used to fabricate nanodelivery systems. The choice of material influences many aspects of the nanoparticle. For example, the rate of release of an encapsulated compound can be tuned by the size and material composition of the nanoparticle [12], and this property has facilitated the use of nanoparticles in several applications [13-15]. In many cases, the nanoparticle material is amenable to surface modification, which provides opportunities to specifically target the incorporated therapeutic to select cells and organs [16-20]. Also, material modification with appropriate transport mediating molecules can facilitate nanoparticle delivery through the skin (topical) [21], gastrointestinal tract (oral) [22], respiratory (aerosol) route [23], urogenital (topical) tract [24], or blood circulation (parenteral) [25,26]. Thus given these unique capabilities, nanoparticles can be readily loaded or coupled with immunomodulatory agents such as cytokines or immune cell-specific ligands and can be administered through a variety of routes to improve immunity against infectious disease. Fig. 4 illustrates how various tunable features of nanoparticles can be adjusted to stimulate or enhance an immune response.

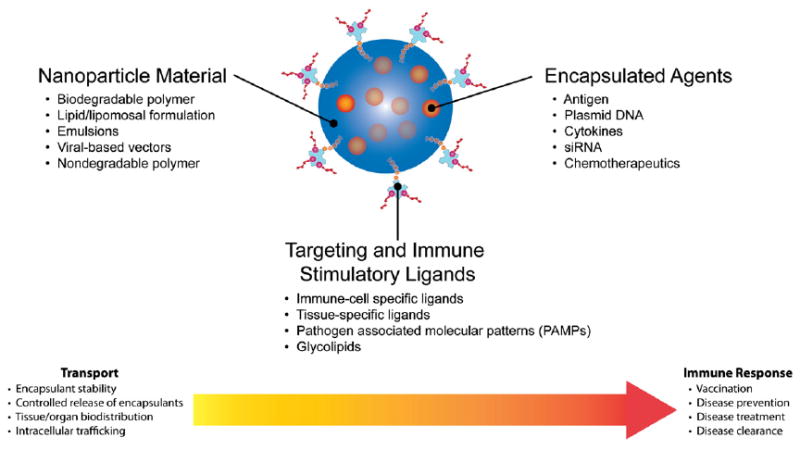

Fig. 4.

Nanoparticles can be modified in many ways to achieve beneficial transport (pharmacokinetic) and immunomodulatory (pharmacodynamic) effects. The composition of the nanoparticle can be fabricated from different materials which control several aspects about nanoparticle transport and pharmacokinetics. The nanoparticle material composition typically controls the loading and release rate of encapsulants from the nanoparticle and can also influence the organ and intracellular trafficking of the particle. Furthermore, certain nanoparticle material formulations can stabilize or protect the encapsulated compound from physiological caustic environments in vivo and possibly from ambient environmental conditions during transport of the therapeutic to remote settings. The addition of targeting and immune stimulatory ligands to the particle surface can enhance cell and tissue specific targeting of nanoparticles. These ligands can also have a direct pharmacodynamic effect by triggering immune responses through cell-surface receptor mediated signaling events, such as when nanoparticle surface associated PAMPs trigger TLRs. Finally, the choice of encapsulant within the nanoparticles can have potent immunomodulatory effects.

2. Prophylactic strategies

Prophylactic therapies have been successful in preventing morbidity and mortality worldwide. However, several infectious diseases in the developing world have eluded current prophylactic strategies. This is partly due to the complex nature of pathogen infection and the failure of current approaches to mount an adequate immune response. Despite the challenges, the development of prophylactic therapies is a necessary control measure to lower infectious disease burden. The treatment and cure of an established infection is difficult for several reasons. For example, some infectious diseases such as malaria and enteric (diarrheal) pathogens cause acute symptoms like fever that have sudden onset and can sometimes be fatal if untreated. Other diseases have no current cure and cause life-time illness, such as HIV and hepatitis B and C. Furthermore, the emergence of multi-drug resistant strains of pathogens such as tuberculosis make some diseases virtually untreatable [27], posing an immediate health concern for both developing and developed nations alike. Although some infections can be effectively cured with treatment, the course of illness can cause permanent disability or disfigurement, such as blindness in onchocerciasis infections and elephantiasis in lymphatic filiariasis infections. Prophylaxis is an absolute necessity to avoid these dire clinical outcomes.

Here we describe two approaches in which nanoparticles can be used to create new generations of versatile and potent prophylactics. Innate immune stimulators and microbicides will be described in the context of eliciting short term protection against pathogen transmission in the event of known potential exposure. For long term protection, we describe vaccination strategies that attempt to elicit immunological memory responses to prevent infection.

2.1. Innate immune stimulators and microbicides

A general pre-emptive strategy to provide short-term protection against infection is to block pathogen transmission at the site of infection. In particular, the transmission of a myriad of sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) through the mucosal surface of the urogenital tract poses a significant health challenge, making the development of broad protecting prophylactic strategies critical. Two potential approaches that can accomplish this objective are: 1) generation of a localized acute immune response via stimulation of innate immunity at the site of infection or 2) disruption of pathogen activity at the exposure site. Both approaches have immediate applicability for protection against STDs such as HIV, human papillomavirus (HPV), and herpes in the female reproductive tract where therapies can be topically administered.

Stimulation of the innate immune system through recognition of PAMPs in the female reproductive tract has demonstrated effective protection against pathogen infection. An innate immune response can limit infection via the relatively quick response of a variety of immune cells (dendritic cells, neutrophils, macrophages, and natural killer cells) and cytokines. One common PAMP is oligodeoxynucleotides (ODN) containing the unmethylated CpG dinucleotides commonly found in bacterial and viral DNA. In a herpes simplex virus-2 (HSV-2) mouse model of infection, soluble CpG ODN delivered via vaginal lavage 24 hours prior to a lethal dose of HSV-2 showed protection against HSV-2 infection [28]. In this study the same protection was not observed when HSV-2 exposure occurred 3 or 5 days after treatment with CpG. It can be hypothesized that the sustained release of CpG ODN from nanoparticles could extend its delivery or potency [29,30].

In addition to eliciting an immune response, microbicides have been developed that specifically reduce or disrupt the infectivity of pathogen in the female reproductive tract. One approach has focused on making this environment more caustic to pathogens by further reducing the pH of the pathogen microenvironment or by delivering detergents that disrupt pathogen structure [31,32]. More directed approaches through surface interactions with viral pathogens include charge association with polyanionic polymers [33] and glycan binding molecules [34]. Delivery of molecules that compete or block pathogen binding domains on cells is another strategy to reduce infectivity. This approach has been utilized to dramatically reduce HIV infection in non-human primates, by preventing HIV from binding to the host cell surface receptor CCR5 using a competitive inhibitor to the CCR5 binding site [35]. This competitive inhibitor, called PSC-RANTES, is a structural analog to the chemokine that normally binds to CCR5. Furthermore, an increased potency of PSC-RANTES was demonstrated in an in vitro model when PSC-RANTES was encapsulated and delivered in poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) nanoparticles [36].

The use of nanoparticles as innate immune stimulators or for microbicide delivery points to newand more effective opportunities for delivering agents to the female reproductive tract. The most common drug delivery system for the female reproductive tract has been the use of macroscale ring shape structures fabricated from non-degradable materials. However, the use of nanoparticles can better overcome the transport limitations of mucosal drug delivery [37]. For example, it has been recently shown that nanoparticle surface modification with hydrophilic ligands can enhance nanoparticle transport through cervical mucus [38]. This strategy may be useful for delivering siRNA in the vaginal mucosa [24], which can potentially be used to inhibit the establishment of pathogen infection.

2.2. Vaccination

Prevailing infectious diseases consist of a broad array of microorganisms, ranging from viruses and bacteria to multicellular eukaryotes including protozoans and helminthes. Although the immunopathology is broad, the multifunctionality of nanoparticulate based vaccines can be flexibly tailored to address the unique challenges posed by each of these pathogens. Design opportunities for these nanoparticulate systems have been extensively reviewed elsewhere [39]. Despite the broad range of pathogen etiology, these pathogens share some commonalities, such as their typical presentation as a chronic disease, many with an intermittent latent period, and an obligate intracellular tropism for most or part of their life cycle. We focus on how some commonalities in pathogen immunobiology and vaccine design—the intracellular tropism of pathogens, immune potentiation with adjuvants, the multi-antigenicity of pathogens, and the need for site-specific immune responses—are common areas in which nanoparticulate systems can be used to improve vaccination against many types of infections.

2.2.1. Nanoparticle methods for activating cellular immunity

Conventional vaccines using live attenuated microorganisms have been successful because they involved the administration of a single vaccine dose that effectively elicited sufficient protective humoral and cellular immunity. Two successful examples of using live attenuated vaccines are the Sabin polio vaccine and the smallpox vaccine. However, live attenuated vaccines are intrinsically environmentally labile and require refrigeration, making the delivery of these therapeutic agents to remote regions difficult, especially in resource poor settings. Furthermore, the use of live attenuated vaccines can be dangerous and cause mortality if the attenuated pathogen is able to revert to a more active, less attenuated form. This danger is particularly acute for immune compromised individuals infected with HIV. Thus current vaccination strategies that utilize live attenuated pathogen, such as the Bacillus Calmette–Guérin (BCG) vaccine for tuberculosis treatment, cannot be safely administered to these individuals [40]. Purified antigen subunits used for vaccination were developed, in part, to avoid these dangers but they are traditionally less immunogenic compared to whole pathogens. Moreover, because of their attenuated immunogenicity after purification, these subunit vaccines sometimes require more than one dose administration, such as in the hepatitis B and diphtheria-pertussistetanus (DTaP) vaccines, which require several injections administered over a span of several months. Booster shots are sometimes necessary, as in the case of tetanus vaccination. In addition, the historical emphasis on eliciting humoral responses with vaccines has limited efficacy against pathogens that require both humoral and cellular responses. Partly because of this historical emphasis, existing vaccine strategies have not been successful against prevailing global infectious diseases, many of which involve obligate intracellular pathogens such as HIV and malaria. Table 1 lists some infectious diseases with their intracellular niche.

Table 1.

Obligate intracellular tropism of infectious diseases. During established infection inside a human host, several pathogens spend all or part of their life cycle within the intracellular space of host cells. All viruses are obligate intracellular diseases, as well as some protozoan and bacterial pathogens. An effective immune response that clears these intracellular pathogens requires cellular (cytolytic) action that can kill infected host cells.

| Disease | Intracellular niche |

|---|---|

| Viruses | |

| Dengue fever | Vascular endothelial cells, white blood cells, hepatocytes |

| HIV | Macrophages, T cells, epithelial cells |

| Herpes simplex virus (HSV-2) | Epithelial cells, neural ganglion |

| Hepatitis B | Hepatocytes |

| Hepatitis C | Hepatocytes |

| Human papilloma virus (HPV) | Urogenital epithelial cells |

| Inuenza A and B | Respiratory epithelial cells |

| Rotavirus | Intestinal epithelial cells |

| Protozoa | |

| Chagas disease | Heart cytoplasm, smooth muscle cells, adipose tissue |

| Leishmaniasis | Macrophages |

| Malaria | Hepatocytes, red blood cells |

| Bacteria | |

| Salmonella | Macrophages |

| Shigella | Intestinal epithelia |

| Tuberculosis | Alveolar macrophages, dendritic cells |

Activation of the cytolytic immune responses that clear infected host cells is thus a key area of research for improving vaccines. Immune cytolytic responses are primarily mediated by CD8 T cells, CD4 Th1 cells, and natural killer T cells. These cytolytic cells can mediate direct destruction of infected cells via recognition of pathogen-derived antigen that is presented in the context of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I or CD1-lipid antigen complexes. Upon antigen-specific recognition of infected cells, these immune cells release cytolytic agents that directly destroy infected cells and can induce inflammatory reactions which facilitate innate immune clearance as well as some humoral response. In order to generate CD8 T cell immunity, many efforts have focused on enhancing cross-presentation, in which exogenous antigen is presented on MHC class I, in order to promote a strong cytolytic and Th1 inflammatory bias. Cross-presentation of exogenous antigen can be challenging, because most exogenous antigens that are internalized by a cell are more readily processed into the MHC class II pathway, which typically stimulates CD4 T cell humoral responses. In order for cross-presentation to occur, antigen must escape from the endosomal compartment into the cytosolic and endoplasmic reticular space where MHC class I processing occurs.

Thus antigen presentation in MHC class I is important for generating cellular immunity during vaccination. The particulate nature of nanoparticles has some inherent ability to facilitate antigen cross-presentation, and several methods have been explored to enhance nanoparticle-mediated MHC class I antigen presentation. These methods include specifically targeting nanoparticles to specialized dendritic cell populations that actively cross-present antigen [41], synthesizing nanoparticles with pH-responsive polymers that naturally facilitate antigen endosomal escape into the cytosol [42], and delivering plasmid DNA in nanoparticles to allow intracellular production of antigen for loading into MHC class I [43].

Some initial studies have suggested that nanoparticles can have some intrinsic ability to cross-present their encapsulated cargo. Shen et al. have shown that PLGA nanoparticles could deliver antigen into the MHC class I antigen presentation pathway [44]. This work with mouse bone marrow-derived dendritic cells showed that PLGA-encapsulated ovalbumin enhanced and sustained antigen presentation in MHC class I to a much higher degree than soluble antigen. In other studies, Baba et al. have used biodegradable poly(gamma-glutamic acid) (gamma-PGA) nanoparticles for enhancing cellular immune responses in an HIV vaccine [45,46]. These studies encapsulated the p24 subunit of the HIV capsid into nanoparticles [45]. When tested in mice, nanoparticles were shown to elicit a better T cell response when compared with a known, potent adjuvant such as complete Freund’s adjuvant (CFA). Similarly, gamma-PGA nanoparticles have also been used to encapsulate the HIV envelope protein gp120 [46]. Intranasal immunization of mice with gp120 loaded nanoparticles induced antigen specific effector and memory CD8 T cell responses.

Enhancing cellular immunity can be improved by specifically targeting key surface receptors on dendritic cells. Upon uptake of antigen, dendritic cells mature, migrate, and process antigen through MHC class II and MHC class I pathways for presentation to CD4 and CD8 T cells, respectively. Dendritic cells express several surface receptors, such as the C-type lectins DC-SIGN and DEC-205 [47-51]. These pattern recognition receptors are internalizing and help deliver antigens to different intracellular compartments that lead to antigen presentation on MHC class I and CD1 molecules. These receptors have led to novel and exciting possibilities for efficient delivery of vaccines to dendritic cells. For example, Steinman et al. have shown that antibody mediated antigen targeting using conjugate protein significantly enhances antigen presentation to both CD4 and CD8 T cells [51].

Some dendritic cell subsets are especially efficient at cross-presentation, and targeted delivery of antigen to these dendritic cell subsets has been explored. Dendritic cells can be subdivided into distinct subsets with varying markers and functions. For example, mouse dendritic cells can be categorized as CD4+, CD8α+, or CD4−CD8α− [52,53]. These different subsets have unique MHC class I or MHC class II processing capabilities. Mouse CD8α+ dendritic cells are specialized to efficiently cross present self and foreign antigens via the MHC class I pathway. Kwon et al. have used pH-responsive microparticles that were surface-conjugated with anti-DEC-205, a targeting ligand for the DEC-205 receptor unique to CD8α+ dendritic cells [41]. Their work showed that in vivo anti-DEC-205 coated particles were internalized by CD8α+ dendritic cells much more efficiently than the control particles. Given these unique dendritic cell targeting possibilities, nanoparticles can be particularly adept at delivering antigens to dendritic cells in a targeted and prolonged manner.

Another strategy to achieve effective dendritic cell cross-presentation is to use pH-responsive materials that naturally facilitate antigen escape from the endosome into the cytosol, where MHC class I antigen processing begins. For example, Tirrell, Hoffman, and Stayton et al. have developed synthetic polymers containing alkyl(acrylic acid) monomers that become protonated at endosomal pH levels (5.5–6.5) [54-57]. Once protonated, the polymers destabilize the endosomal membrane and allow antigen to escape into the cytoplasm. Alternatively, Fréchet et al. synthesized acid-sensitive microgels that also disrupt endosomal stability. At endosomal pH, the microgels degrade and cause the endosome to lyse by colloidal osmotic pressure, leading to antigen delivery into the cytosol [58].

In addition to the delivery of subunit antigens, the delivery of antigen-encoding plasmids can facilitate MHC class I antigen presentation [59]. This is possible because endogenous (intracellular) production of gene products are readily processed into the MHC class I pathway. Nanomaterials that can facilitate intracellular gene delivery can readily improve antigen presentation into MHC class I. Most of these materials are polycationic in order to facilitate complexation with nucleic acids. For example, emulsion polymerization was used to fabricate poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA) nanoparticles with a positively charged surface that electrostatically adsorbed plasmid DNA [60]. Nanoparticles adsorbed with a plasmid encoding for the HIV-1 Tat protein were intramuscularly injected into mice, which induced Tat-specific cellular and humoral responses. Alternatively, poly(ethyleneimine) (PEI) nanoparticles have been used to encapsulate and deliver an HIV-1 antigen-encoding plasmid. These PEI nanoparticles are functionalized with mannose and are administered from a transdermal patch [61,62]. The mannose enhances the targeted delivery of the nanoparticles to Langerhans cells, a dendritic cell subset that resides in the epidermis. The use of these nanoparticles in non-human primates was observed to generate both cellular and humoral immunity and was found to not cause any local or systemic toxicity [62].

Antigen presentation in MHC class I by dendritic cells can also be enhanced by dendritic cell stimulation with natural killer T cells (NKT). NKT cells are key players in innate immunity because they mediate anti-viral responses, produce IFN-γ, and activate dendritic cells to cross-present antigens and produce the Th1 polarizing cytokine IL-12 [63]. NKT cells possess an invariant T cell-like receptor that binds strongly to alpha-galactosylceramide presented by CD1d on antigen presenting cells. Alpha-galactosylceramide is a safe, lipid adjuvant that potently stimulates NKT cells, and thus may be useful for enhancing cellular immune responses. The activation of NKT cells and the use of alpha-galactosylceramide has been reported to have broad use for vaccination [64] against several intracellular pathogens, including HIV [65], tuberculosis [66], and malaria [67]. However, freely-circulating alpha-galactosylceramide in vivo can induce anergy (inactivation) of NKT cells [63]. This anergy is due to non-selective presentation of alpha-galactosylceramide by circulating, CD1d expressing B cells, which do not provide sufficient co-stimulatory signals to NKT cells to overcome anergy induction [68]. One effective strategy to overcome this problem is to use poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) nanoparticles for targeted delivery of alpha-galactosylceramide to dendritic cells [69], because dendritic cells can provide greater co-stimulatory signals than B cells to prevent anergy induction in NKT cells [70]. NKT cells were effectively stimulated in vitro and in vivo with these nanoparticles, without inducing anergy. Soluble alpha-galactosylceramide caused NKT cell inactivation after a single exposure, while nanoparticle functionalized alpha-galactosylceramide did not induce anergy to NKT cells even after repeated exposure. This effect was caused by the preferential uptake of nanoparticles by dendritic cells and macrophages but not B cells [69]. Thus, the incorporation of alpha-galactosylceramide on particles was necessary to achieve an immunotherapeutic effect that would not have been possible with soluble free alpha-galactosylceramide.

Despite the vast interest in generating improved cellular immune responses, it should be noted that humoral immunity (antibody response) still remains necessary for preventing and managing many intracellular pathogens. Pathogens such as HIV also exist extracellularly for part of their life cycle, in addition to their predominant intracellular niche. A recent HIV vaccine trial in humans (referred to as the ‘STEP study’) used intramuscularly injected adenoviral vectors to specifically induce cellular immunity [71]. Cellular immunity was generated, as measured by the presence of IFN-γ and TNF-α secreting CD4 T cells and HIV epitope specific CD8 T cells. However, the cellular vaccine ultimately failed to prevent HIV infection. It is currently unclear why the cellular vaccine was not effective in the STEP study, but it has been hypothesized that the epitopic breadth and cytokine profiles of the cytolytic T cells generated from the STEP study vaccine were insufficient to provide protection. Other hypotheses have suggested that, more generally, a strictly cellular vaccine is not sufficient to provide complete protective immunity, but can sometimes still be beneficial to controlling an established infection [72].

2.2.2. Immune potentiation with adjuvant-functionalized nanoparticles

In order to improve the immunostimulatory nature of traditional antigen subunit vaccines, immune potentiators called “adjuvants” are often used. Adjuvants are compounds that can activate immune inflammatory reactions. These inflammatory reactions enhance the immunogenicity of antigen subunit vaccines and facilitate the generation of an immune memory response. In addition to their role as effective antigen delivery vehicles, nanoscale drug delivery systems can be modified to present adjuvants and can even act themselves as an adjuvant. Nanoparticles that initiate inflammation or complement in the innate immune can thus potentiate and shape the adaptive immune response.

An actively explored vaccination strategy is to incorporate PAMP ligands that stimulate PRRs in order to elicit inflammatory responses. PRRs are expressed on tissue-specific epithelial cells as well as immune cells including macrophages, dendritic cells, and B cells. The toll-like receptors (TLRs) are one class of PRRs that have been extensively researched. Many immunostimulatory adjuvants are TLR ligands such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS), monophosphoryl lipid A, CpG DNA, and muramylpeptides [73-76]. These adjuvants can be incorporated in nanocarriers to enhance an immune response [73,77]. Two other recent classes of innate immune receptors are the cytosolic Nod-like receptors (NLRs) and RIG-like helicases (RLHs). NLRs and RLHs are also involved in pathogen recognition and immune modulation. TLRs, NLRs, and RLHs, can all work in collaboration through interacting signaling pathways. The exact mechanism of how adjuvants initiate these innate inflammatory pathways is still a new area of research. However, these emerging paradigms represent a novel design strategy to integrate into nanoparticle vaccines. The functional outcome of innate immune receptor signaling plays a dominant role in deciding the type of immune response that is generated. Thus stimulating these signaling pathways can optimize vaccine efficacy.

The synthetic material of a nanoparticle may act as an adjuvant itself, without other agents, by activating various signal transduction pathways which are conducive to immune system priming. It has been recently shown that the NALP3 inflammasome, a member of the intracellular NLRs, is activated by alum [78], uric acid [79], silica [80] as well as PLGA microparticles and nanoparticles [81,82]. In particular, recent work by Sharp et al. has shown that cellular internalization of PLGA and polystyrene microparticles induced large amounts of IL-1β production in dendritic cells via inflammasome activation. IL-1β is a potent inflammatory cytokine involved in macrophage recruitment, and is produced by monocytes, macrophages, and dendritic cells. Internalization of microparticles activated the inflammasome through lysosomal damage and caspase-1 activation [81]. The presence of a TLR agonist was essential to induce the IL-1β response in vitro, but in vivo TLR agonist was observed to not be required to produce IL-1β at the site of injection. This work showed that microparticulate adjuvants work by activating the NALP3 inflammasome.

Similarly, Demento et al. has recently shown that PLGAnanoparticles incorporating LPS on their surface led to the production of IL-1β in wild type macrophages. NALP3-deficient and caspase-1 deficient macrophages showed negligible production of IL-1β. This apparent inflammasome activation depended on nanoparticle internalization and the subsequent destabilization of lysosomal compartments [82]. Inflammasome activation and IL-1β production occurs at nontoxic doses that do not induce cell death. Unpublished work in our lab has shown that in vitro exposure of bone marrow-derived dendritic cells to PLGA nanoparticles at concentrations less than ~450 μg/mL do not cause cell death and is sufficient for immunomodulation. The LPS-modified nanoparticle vaccine by Demento was tested in vivo, using recombinant West Nile virus envelope protein as antigen. The in vivo results showed that mice vaccinated with the LPS-nanoparticle system possessed enhanced protection from subsequent challenge with a lethal dose of West Nile Virus [82]. This observation is among the first reports that describe the efficacy of using nanoparticles to enhance vaccination against a flavivirus, and this particular formulation may have broad applicability for vaccination against other prevalent flaviviruses such as Dengue fever, Japanese encephalitis, and St. Louis encephalitis. These flaviviruses have evolutionary conserved expression of the envelope protein, which is a component of all flaviviral capsids and mediates viral entry into host cells. The use of nanoparticles with TLR stimulators can enhance the immunogenicity of flaviviral envelope protein antigen, which has been observed to be poorly immunogenic when administered on itsown [83] or in PLGA nanoparticles without LPS incorporation [82]. Furthermore, although many groups have extensively shown over the past twenty years that the use of PLGA particles can improve vaccine responses, the findings by Sharp and Demento are among the first to demonstrate the novel mechanism that inflammasome activation by particles contributes to their adjuvant effect.

Other particulate materials can stimulate signaling pathways that lead to cellular activation. Baba et al. have shown that gamma-PGA nanoparticles can be used as a vaccine adjuvant. These nanoparticles induced dendritic cell maturation through MyD88-mediated NF-κB activation and the p38 MAPK pathways, in a manner somewhat similar to LPS maturation of dendritic cells [84]. Dendritic cells that internalized these nanoparticles could successfully activate T cells. Mice that were immunized with these particles carrying a peptide of Listeria monocytogenes were protected from pathogen infection. Thus, particulate matter may also act as an adjuvant simply by inducing maturation of dendritic cells. Extensive in vitro studies by Babensee et al. and Elamanchili et al. have shown that exposure of bone marrow derived dendritic cells to polymers such as PLGA results in dendritic cell maturation as measured by the up-regulation of cell surface stimulatory markers such as MHC II, CD40, CD80 and CD86 [85-88].

Immune potentiation can also be achieved by activating the complement system. Triggering of complement activates a series of complement component proteins and enzymes which can promote inflammation, macrophage phagocytosis, anaphylaxis, B cell maturation, and T cell responses [89], as well as enhance antigen presentation by follicular dendritic cells residing in the lymphoid tissue [90]. The use of nanomaterials that are specifically designed to activate complement may initiate immunostimulatory signals that enhance vaccination. This strategy has been employed with synthetic polyhydroxylated nanomaterials that chemically activate the C3b component of the complement cascade in order to activate lymph node resident dendritic cells in mice [91]. Particulate surface coating with hydroxyl groups has been suggested to induce complement by direct activation of C3b through the alternative complement pathway [92], and has been shown to be dependent on the surface presentation of hydroxyl groups with polysaccharide coatings [93]. Alternatively, the use of the complement protein C3d, which is activated downstream of C3b in the complement cascade, has also been explored as an adjuvant in gene-based vaccines [94-96]. Complement can also be activated by the nonspecific adsorption (fouling) of complement proteins, antibodies, and opsonins onto nanoparticles [97], which leads to enhanced phagocytosis of nanoparticles by macrophages and other monocytes [26,98]. The immunostimulatory effects of nanoparticle opsonization and complement on macrophages can be multifaceted, because macrophages can participate in antigen presentation to T cells and are also potent producers of inflammatory cytokines, chemokines, and other stimulatory molecules which prime adaptive immune responses. In addition to IL-1β, macrophages can produce a variety of cytokines upon nanoparticle internalization and also upregulate surface stimulatory molecules [99]. Furthermore, nanoparticle opsonization by the complement components C1q or C5a may stimulate the macrophage complement receptors gC1qR or C5aR and lead to a differential, respective decrease or increase of IL-12 production from the macrophage [100,101].

2.2.3. Vaccination against multi-antigenic and multi-stage pathogens

Many infectious diseases are difficult to vaccinate against because they have multi-antigenic variability and shedding that allow them to constantly evade antigen-specific memory immune responses. This multi-antigenicity can be attributed to antigenic-variation of pathogen proteins through selective gene expression such as in malaria [102] or many bacteria [103], the existence of different stages of the pathogen life-cycle within the host such as leishmaniasis and malaria, and rapid viral mutations in HIV. One method to overcome this immune evasion strategy of antigenic variability is to vaccinate with a combination delivery of multiple antigens (sometimes referred to as ‘multivalent’ vaccines). Nanoparticle formulations are particularly well-suited for this purpose. For example, in one HIV vaccine, the HIV- 1 p24 and gp120 proteins were adsorbed onto the surface of surfactant-free anionic poly(lactic acid) (PLA) nanoparticles. The use of these PLA nanoparticles in mice elicited high antibody titers against both antigens. Development of such multi-antigenic vaccines is thus possible with anionic PLA nanoparticles [104,105].

A multi-stage prophylactic vaccine that targets antigens in both the early and late stage life cycles of a pathogen could improve immunization strategies. This strategy would be useful for preventing many types of protozoa and helminthic diseases that have unique tissue-specific stages during their life-cycle, as well as for preventing certain pathogens with long latent stages such as tuberculosis and most viral diseases. In malaria, the parasite invades the hepatocytes as a sporozoite; upon maturation to the merozoite stage of its life cycle, malarial parasites invade and replicate within red blood cells. The febrile illness and hemorrhagic complications during malaria sickness are due to the blood-stage merozoites. In order to achieve full protective immunity against both the liver and blood stage forms of malaria, which is referred to as ‘sterile immunity’, vaccines using antigens unique to both life-cycle stages have been researched. For example, malarial liver and blood stage antigens were loaded in a nanoscale carrier fabricated from the influenza virus [106]. When these so-called ‘virosomal’malaria vaccines were tested in a Phase II human clinical trial, patients developed protective immunity from the blood stage cycle of Plasmodium falciparum, but liver stage infection still occurred. While this initial study demonstrated the efficacy of developing blood stage immunity, the failure to prevent liver stage infection and generate full sterile immunity remains an important area of optimization.

Similar multi-antigenic strategies have been employed for vaccinating against tuberculosis by delivering plasmids encoding for multiple tuberculosis antigens. This ‘vaccine’ may be useful even after the establishment of infection, since tuberculosis vaccines can still potentiate immune responses that aid in bacterial clearance [107,108].

2.2.4. Effective generation of site-specific memory responses

The delivery route of vaccines primes the generation of site-specific, memory immune cells which can readily respond against pathogen. Many vaccines are administered parenterally, which can trigger systemic immunity but not necessarily effective mucosal immunity. Mucosal surfaces, which primarily consist of the gastrointestinal (oral), respiratory, and urogenital tract, are an important immunization site because most pathogens enter the body through a mucosal surface. Although mucosal administration of vaccines (reviewed in this issue of Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews) can improve patient compliance, physiological barriers such as mucus, low pH, and a digestive environment can limit the transport of functionally intact vaccine in these environments. Microparticle and nanoparticle vaccine systems can be uniquely tailored to overcome tissue specific transport limitations, and make mucosal and even cutaneously delivered vaccines more effective.

Oral vaccines have been actively investigated for antigen delivery to gut associated lymphoid tissue (GALT) and systemic mucosal associated lymphoid tissue (MALT). Many particulate oral vaccines have employed microparticles which induced potent mucosal and systemic immunity [109-111] against numerous pathogens, such as Bordetella pertussis [112], Chlamydia trachomatis [113], Salmonella typhimurium [114], and Mycobacterium tuberculosis [115]. Similar successful studies have been conducted in non-human primates for microparticle mucosal vaccination against simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) [116] and Staphylococcus aureus [117]. Nanoparticles have also been used to enhance gastrointestinal antigen uptake via specialized epithelial cells known as M-cells [118], which facilitate antigen transfer to lymphoid tissue. The efficiency of nanoparticle uptake by M cells can be enhanced by functionalizing nanoparticles with M cell-specific ligands or PEG [119,120].

Nanoscale aerosol vaccines have been developed for respiratory-transmitted pathogens like tuberculosis. Most inhaled vaccines for tuberculosis consist of nebulized droplets which can perfuse throughout the respiratory pathway. Edwards et al. have recently synthesized a particle system with both micrometer and nanometer dimensions for aerosolized delivery of the attenuated tuberculosis vaccine, BCG [121]. These so-called dried “nanomicroparticle” vaccines were synthesized with two axes with nanoscale dimensions and a third axis with a microscale dimension. The non-uniform dimensions of the nanomicroparticles improved particulate aerosolization, dispersion, and trafficking in the respiratory tract. Aerosol delivery of BCG-encapsulated nanomicroparticles in guinea pigs enhanced their resistance to tuberculosis infection, and generated better immune protection than a standard parenteral BCG formulation.

A particle’s size strongly influences where it can traffic, as microscale and nanoscale particles have very different trafficking patterns. This size-dependent trafficking can greatly influence particulate strategies for vaccination, whether for mucosal or parenteral delivery. For example, recent work by Manolova et al. has shown that nanoparticles trafficking to the draining lymph nodes is size dependent [122]. They observed that 20–200 nm diameter nanoparticles injected intradermally in mice could readily migrate to the draining lymph nodes for uptake by lymph node resident dendritic cells. However, larger nanoparticles with a 500–2000 nm diameter were internalized by skin-resident dendritic cells, which subsequently migrated to the lymph node. These differential trafficking patterns may govern the outcome of immune responses, since CD8α+ dendritic cells in the lymph nodes can better prime cellular immune responses than skin resident Langerhan dendritic cells [123]. Similarly, Reddy et al. showed that intradermally administered, ultra-small (25 nm diameter) nanoparticles are more efficient at interstitial lymphatic trafficking to lymph node resident dendritic cells than larger (100 nm diameter) nanoparticles [91].

3. Treatment of chronic infections

Chronic infections involve pathogens that have long-term persistence in the host and are not fully cleared by the immune system. Table 2 summarizes the broad range of pathogens that can cause chronic disease. The failure of the immune system to normally clear these pathogens is caused by several immune evasion mechanisms that are unique to each pathogen. These immune evasion mechanisms include pathogen migration into immune-privileged sites, the existence of a viral latent state that integrates into the host cell genome, antigenic variation to evade memory specific responses, and the skewing of inflammatory cytokine responses to an immunosuppressive and toleratory phenotype. These unresolved infections create long-term debilitating conditions or inflammatory responses that lead to tissue and organ damage or the predisposition of infected individuals to coinfection or opportunistic infection.

Table 2.

Select strategies for chronic infection treatment. Most chronic infections require long-term administration of therapeutic compounds to manage disease. This list of chemotherapeutic drugs is not exhaustive; tuberculosis and malaria treatment can involve other compounds not listed here. Nanoparticle strategies have been developed for the treatment of chronic disease. These nanoparticle therapies may have higher potency or less toxicity to the human host, and thus could be useful in better treating or minimizing the drug dosing regimen during chronic infection management. Some helminthic diseases can be treated with a single dose of chemotherapeutic agent, but infection can cause life-long disability and organ damage.

| Chronic condition | Current treatment strategy | Therapy duration | Example of nanoparticulate strategies |

|---|---|---|---|

| HIV/AIDS | Highly active anti-retroviral therapy (HAART) | Life-time; daily oral dose | Dermavir patch [62] |

| Hepatitis B | Lamivudine (reverse transcriptase inhibitor) Pegylated IFN-α |

Life-time; 1-2 oral doses of lamivudine daily [183] | siRNA delivery with lentiviral vector [138] |

| Hepatitis C | Ribavirin Pegylated IFN-α |

Life-time; 1–2 oral doses of lamivudine daily; 2–3 weekly injections of pegylated IFN-α [184] | siRNA delivery with lentiviral vector [137] |

| Leishmaniasis | Pentostam Glucantime Amphotericin B Paromomycin |

30 days; daily i.v. [185] | AmBisome-liposome formulation with amphotericin B [186] |

| Tuberculosis | Rifampicin Isoniazid Pyrazinamide Ethambutol |

6–9 months; three oral doses per week [187] | Aerosolized rifampicin-PLGA [131]; aerosolized IFN-γ emulsions [149] |

| African trypanosomiasis | Suramin Pentacarinat Melarsoprol Ornidyl |

10–20 days; daily i.v. injection, up to 4 times/dy [185] | Lipid-drug nanoparticles [129] |

| Chagas disease | Nifurtimox Nitroimidazole |

≥60 days [185];2–3 daily oral dose [185], [188] | PEG-PLA nanoparticles [189] |

| Lymphatic filariasis | Diethylcarbamazine Ivermectin |

12-day regimen with diethylcarbamazine; annual dosing for 4–6 years with ivermectin combination therapy [190] | |

| Trichuriasis | Mebendazole | 2 daily oral doses for 3 consecutive days [190] | |

| Hookworm | Albendazole Mebendazole |

2 daily oral doses for 3 consecutive days [190] | |

| Onchocerciasis | Ivermectin | 1 oral dose [191] | |

| Schistosomiasis | Praziquantel | 1 oral dose [192] | Lipid emulsion [193] |

| Malaria | 4-aminoquinolines 8-aminoquinolines 4-Quinolinemethanols Artemesinin Atovaquone Antibiotics |

variable; typically 3–7 days for acute phase, followed by daily dose with Primaquine for 2 weeks [194] | Lipid emulsion of Primaquine [133] |

The effective management and treatment of these chronic infections typically require a life-time therapeutic regimen that can be costly and inconvenient to routinely administer in resource-poor settings. These chronic infections are responsible for a significant loss of economic output and productivity due to debilitating patient illness and infirmity, and thus represent an important aspect of infectious disease control that must be addressed alongside the development of prophylactics. Many of these chronic diseases, such as those caused by the HIV or hepatitis B and C viruses, have no available cure and so current disease management is limited to the use of anti-viral therapies that limit the expansion of viral load. Other chronic diseases, such as malaria, tuberculosis, leishmaniasis, and many helminthic diseases can be cured using synthetic chemotherapeutic agents that are toxic to the pathogen. However, the administration of these chemotherapeutic agents can require long-term administration (lasting several weeks) for complete clearance. Many patients in resource-poor settings do not complete the full duration of therapy, and there is consequentially an increased risk of developing chemotherapeutic-resistant strains of the pathogen [124,125]. In the absence of effective chemotherapeutic drugs, the treatment of chronic infections is supportive, relying primarily on corticoids and other anti-inflammatory compounds that alleviate symptoms but not the underlying pathogen.

Treatment of chronic infections should ideally be potent enough to require only a single or limited number of doses, have minimal toxicity, be inexpensive, and be easy to deliver and administer to patients. Nanoparticulate based solutions have the inherent ability to address these requirements, due to their ability to release therapeutic compounds over prolonged periods and the ability to target relevant sites of pathogen infection. The vast majority of current nanotechnology therapeutics has focused on the effective delivery of chemotherapeutic or antisense compounds to directly inhibit or kill pathogens that cause chronic infection. Here we review some of these existing developments, and discuss how future nanotechnologies can be potentially modified to overcome pathogen immune evasion by eliciting favorable immune defense mechanisms.

3.1. Passive chemotherapeutic and gene targeting to innate immune cells

Passive nanoparticulate targeting of chemotherapeutics to the cells and organs of the reticuloendothelial system (RES) has been a significant area of research for the treatment of chronic infectious diseases. The RES comprises monocyte-lineage immune cells such as macrophages and dendritic cells, as well as the spleen, liver, and kidneys. These components of the RES are consistently implicated as sites of nanoparticle clearance and localization [126]. Although many strategies have been developed to prevent nanoparticle clearance by the RES, passive nanoparticle targeting to the RES can be beneficial in the treatment of chronic infections, as many of these pathogens reside within the organs and immune cells of the RES. Leishmaniasis and tuberculosis, which are both obligate intracellular anaerobes, reside within the macrophages of human hosts. Because macrophages are highly efficient at nonspecific particulate endocytosis, various nanoparticulate strategies have been developed to specifically deliver chemotherapeutic compounds for macrophage uptake [127]. The use of nanoparticulate drug delivery system can sometimes improve the tolerability of toxic chemotherapeutics [128]. Many of these nanoparticulate systems are primarily lipid-based vehicles as small as 10 nm, and can be used to treat several types of parasitic infections [129]. Intravenously administered nanoparticles containing the drug amphotericin B have been explored as a treatment strategy for leishmaniasis [130]. These studies have shown that passive nanoparticulate targeting can effectively inhibit leishmania parasites that reside within the macrophages and even those that exist extracellularly. Passive targeting of chemotherapeutic compounds to alveolar macrophages has also been explored using pulmonary administration of nanoparticles for the treatment of tuberculosis infections [131]. The innate feature of macrophages to nonspecifically uptake nanoparticulates may make it possible to more cheaply and inexpensively produce nanoparticulate systems by avoiding the need for expensive functionalization with targeting ligands.

Although RES passive targeting of nanoparticles to the liver is feasible, most of this distribution can be attributed to uptake by liver resident Kupffer cells and not the actual hepatocytes [132]. In malaria, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C infections, the hepatocytes are reservoirs for these pathogens. Strategies have been developed to more specifically target liver hepatocytes by utilizing the natural ability of hepatocytes to internalize chylomicrons, which are lipid emulsions that can be synthetically fabricated and loaded with chemotherapeutics and even siRNA. Lipid formulations of primaquine nanoparticles have been synthesized, and can be orally or systemically administered to achieve effective anti-malarial effect [133,134], and thus could be used for leishmaniasis treatment. Another strategy to target hepatocytes is to use liver-specific viral vectors. For example, Yamada et al. created nanoparticles from the L-subunit of the hepatitis B viral capsid [135]. These viral-nanoparticles could be used for targeted delivery of DNA and small molecule drugs.

Not all chronic infections can be effectively cured by the delivery of chemotherapeutic compounds. The life-long administration of therapeutic agents is necessary for many chronic viral diseases which permanently form a latent reservoir within their host, such as hepatitis B and C, herpes, and HIV. These viruses integrate their viral genome within the chromosomes of their host. The integrated virus can persist within the host cell in an inactive state; periodically, the virus can reactivate and rapidly reproduce progeny, causing chronic disease. The life-long recurrence of disease requires the life-long administration of therapy to inhibit viral proliferation. Gene therapy has been a recently explored strategy for constitutively delivering interfering antisense oligonucleotides and siRNA against viral pathogen synthesis [136]. Some of these efforts have involved the use of lentiviruses that can deliver siRNA [137]; the use of lentiviruses appears to be most successful in maintaining long-term transcript expression that can last for several weeks in vivo [138], due to integration of the gene into the host chromosome. However, in one human trial using viral-mediated gene therapy, viral vector integration into the host chromosome caused mutations that led to the development of leukemia [139]. This unexpected oncogenesis has prompted concern over the use of viral vectors. Non-integrating viral vectors, such as adenoviruses, have also been explored as an alternative to lentiviral vectors but adenoviruses may not be suitable because of their more rapid immunogenic clearance [140]. Thus the immunogenicity of viral vectors may preclude their use in treating life-long chronic diseases, if multiple doses are necessary. Other gene therapy delivery efforts have relied on the use of non-viral vectors, such as cationic polymers or lipids, to deliver siRNA [141,142].

3.2. Combination or adjunct therapy with immunomodulatory agents

Preexisting chemotherapeutic strategies may be potentially enhanced when combined with immunostimulatory agents. By stimulating the immune response against a pathogen and delivering toxic drugs to it, several clearance mechanisms are invoked in order to reduce the likelihood that the pathogen can evade all treatment strategies. This strategy is already in use for certain chronic infectious diseases. In conventional hepatitis C treatment, combination therapy involves using the viral nucleotide inhibitor ribavirin in conjunction with a pegylated form of interferon-alpha (IFN-α) [143,144]. IFN-α is a potent cytokine involved in antiviral-response that can lead to enhanced CD8 T cell and NK cell cytolytic response; the use of poly (ethylene glycol) conjugated to IFN-α (pegylation) helps extend the half-life of the IFN-α in vivo. This combination therapy raises the possibility of using nanomaterials to deliver both immunomodulatory cytokines together with chemotherapeutic drugs to more effectively treat existing chronic infections. For example, the therapeutic gene delivery of IL-12 to the liver in a hepatitis B animal model reduced viremia and enhanced cytolytic immune responses [145]. The use of immunotherapeutic intervention with chemotherapy may even be necessary for treating multidrug resistance strains of a pathogen. In the treatment of multidrug resistant tuberculosis, the administration of cytokines such as low dose IL-2, which stimulates T cells and NK cells, can improve disease outcome when conventional antibiotic therapy fails [146,147]. Alternatively, the nanoparticulate delivery of aerosolized IFN-γ via the pulmonary route has been shown to be a safe and efficacious new adjunct treatment for tuberculosis [148,149] when used in combination with antibiotics. The delivery of other cytokines such as IL-7 or IL-15, which can enhance cellular memory response against chronic infection [150-152], has also been shown to be an effective immunotherapy for HIV [153].

Chronic infectious diseases can persist because cells of the immune system have upregulated cytokines and receptors that lead to immune inactivation and even tolerance of the pathogen. A poor immune response against chronic intracellular pathogens can be improved by the use of nanomaterials that prevent the inactivation of cytolytic cellular responses, such as CD8 T cells and NK cells. For example, many chronic infections persist because of the inability of CD8 T cells to sufficiently maintain effective cytolytic responses against pathogen-infected cells. This CD8 T cell “exhaustion” results in a more immune toleratory phenotype to the pathogen, and can be characterized by expression of PD-1 on the surface of T cells. Stimulation of PD-1 leads to contraction of T cells responses [154,155]. Delivery of a PD-1 siRNA or blockading agent may potentially be useful for treating chronic infections [156,157]. Similarly, in many helminthic infections, the immunosuppressive cytokines TGF-β and IL-10 are often secreted [158]. IL-10 mitigates macrophage function and IFN-γ production, while TGF-β can function to produce immunosuppressive T regulatory cells. Current particulate delivery strategies of TGF-β [159] or IL-10 [160] siRNAs could potentially be used to relieve this immunosuppression. Interestingly, there are many similarities between chronic infection immunobiology and cancer persistence. Thus future immunotherapeutic strategies initially developed in cancer models, for which there is currently much more extensive literature, may potentially be adopted for chronic infectious disease control.

4. Appropriate nanodiagnostic technologies to facilitate immunotherapeutics

The therapeutic monitoring of infectious disease progression is important for administering the appropriate therapeutic compound and controlling the dosing regimen. Despite the broad range of infectious agents, disease symptoms share remarkable overlap and correct differential diagnosis of the causative agent is difficult without serological, nucleic acid, culture, or histological analysis. In developing countries, there is a need for appropriate diagnostic technologies which are clinically accurate and reliable, cheap, quick, and simple to use. In vitro nanoscale diagnostic devices may be particularly useful because they can have high sensitivity and can be multiplexed to detect a broad panel of different antigens, nucleic acid sequences, and other molecular indicators of disease state [161]. Diagnostic technologies would be useful for therapeutic monitoring of patients with acute and chronic infections, such as with differential diagnosis of fevers or with measuring CD4 T cell numbers in HIV patients [162]. Several reviews highlighting the unique capabilities and technical requirements of such diagnostics for the developing world have been described elsewhere [163-165] and in this issue of Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews. A majority of such “lab-on-a-chip” diagnostics employ some form of immunoassay or nucleic acid detection for cell or molecular detection, coupled to an optical transducer for quantitative measurement. An alternative nanoscale diagnostic strategy is to use semiconducting nanowires as an electrical transducer for serological measurements [166] and functional responses by antigen-specific immune cells [167].

The high sensitivity of nanoscale diagnostics is particularly useful for evaluating the immune system, because the immune system itself can be highly responsive to very low amounts of antigen [168] and still yield a response. Detecting the presence of antigen-specific cells is important for monitoring the progress of an immunotherapy, but functional assays of these cells is also necessary to provide a more complete understanding of how these cells affect immune function. For example, the differentiation of T cell subsets after mouse leishmaniasis vaccination results in a heterogeneous Th1 population that produces different combinations of cytokines; a Th1 cell can produce IL-2, IFN-γ, and TNF-α but not necessarily all of these cytokines at the same time or in the same combination [169]. This variability within an individual and between individuals can be related to population differences, the presence of coinfections, and previous infection by other pathogens. It may be useful to use nanodiagnostic technologies to rapidly detect these immune cell functional differences to predict vaccine or therapeutic outcome. The ability to detect antigen specific cells and their functional response after vaccination or during active infection by a pathogen may provide readily available, patient-specific, personalized information that is useful to administering immunotherapeutics. Nanodiagnostic technologies are potentially well-suited to perform these assays on a shorter time scale (seconds to minutes) than with conventional laboratory equipment and assays which can take several hours or days to complete [166,170-172].

5. Future research areas and challenges

The use of immunomodulatory nanotechnologies for improving infectious disease outcome contains many future opportunities for research and development. In addition to the extensive work already done in prophylactic technologies and particularly vaccination, there are at least three emerging needs that require additional focus in the development of immunomodulatory nanoscale therapeutics: chronic disease infection, infection with multidrug resistant pathogens, and coinfection by multiple diseases (particularly of HIV with tuberculosis [173,174] or hepatitis [175], but also helminthes with other pathogens [176,177]). The high burden of these infectious disease challenges that occur when preventative measures fail warrant the development of new and more effective therapeutics for disease treatment. Yet there is little available research in these areas. Nanotechnology solutions may help address this need, by improving the efficacy of therapeutic regimens and thus potentially reducing the frequency and cost of dosing. As advances in immunobiology and pathology further elucidate immune system function during infection, nanoscale systems can be better designed to address the specific challenges of infectious disease in the developing world.

The use of immunomodulatory nanotechnologies for stimulating the immune system must be reconciled with concerns about nanotechnology biocompatibility and toxicity. For example, although biomaterial-induced inflammation is sometimes considered adverse, it can also be considered necessary and beneficial in immunotherapies. Dobrovolskaia and McNeil [178] have reviewed the immunological responses (immunotoxicity) against nanoparticles from various nanomaterials, and outline in vitro and in vivo assays for measuring toxicity during preclinical testing.

The practical use of nanotechnologies in the developing world presents unique socioeconomic and cultural issues that may need to be evaluated. A full discussion of these topics is beyond the scope of this review, but is important to emphasize because end user considerations may affect the feasibility of new nanotechnologies. Financial affordability and cultural acceptability for nanotechnology medicines must be carefully evaluated. The existence of cooperative agreements between pharmaceutical companies, governments, and nonprofit organizations has had some success with providing free or affordable therapies for certain diseases [179,180]. The emergence of strategic philanthropic organizations provides an additional funding structure to finance disease treatment [181]. Additionally, cultural acceptance for nanomedicines must exist before it can be widely adopted [182]. By establishing clinical efficacy, affordability, accessibility, and acceptance for new technologies, these therapeutics can be better translated for use on a global scale.

Acknowledgments

M.L. is a graduate research fellow of the National Defense Science and Engineering Graduate (NDSEG) program from the U.S. Department of Defense, and the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship Program(NSFGRFP).A.B. is supported by a National Research Service Award (NRSA) postdoctoral fellowship (5T32 HL007974-08) from the National Institutes of Health (NIH). J.S.B. is supported through an NIH postdoctoral fellowship (F32AI072942). T.M.F. is funded by an NSF Nanoscale Interdisciplinary Research Team (NIRT) grant (CTS- 0609326). We thank Stacey L. Demento and Dr. Atanu Sengupta for review of this paper.

References

- 1.The World Health Organization. The global burden of disease: 2004 update. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Iwasaki A, Medzhitov R. Toll-like receptor control of the adaptive immune responses. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:987–995. doi: 10.1038/ni1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mogensen TH. Pathogen recognition and inflammatory signaling in innate immune defenses. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2009;22:240–273. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00046-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]