Abstract

Objective

To determine if OnabotulinumtoxinA injections and task practice training with or without functional electrical stimulation (FES) improves upper limb motor function in chronic spastic hemiparesis.

Design

Randomized controlled trial.

Setting

Outpatient spasticity clinic.

Participants

Participants (N=23) had chronic spastic hemiparesis with moderate-severe hand impairment based on Chedoke-McMaster Assessment ≥ 2.

Interventions

OnabotulinumtoxinA injections followed by 12-weeks of post-injection task practice. Participants randomly assigned to FES group were also fitted with an orthosis that provided functional electrical stimulation.

Main Outcome Measures

Motor Activity Log (MAL)-Observation was the primary outcome. Secondary outcomes were Action Research Arm Test (ARAT) and MAL-Self-Report.

Results

For the entire cohort, MAL-Observation mean item scores improved significantly from baseline to week-6 (p = 0.005), but did not remain significant at week-12. MAL-Self-Report mean item scores improved significantly (p = 0.009) from baseline to week-6 and remained significantly higher (p = 0.014) at week-12. ARAT total scores also improved significantly from baseline to week-6 (p = 0.018) and were sustained at week-12 (p = 0.032). However, there were no significant differences between the FES and No-FES groups for any outcome variable over time.

Conclusions

Rehabilitation strategies that combine OnabotulinumtoxinA injections and task practice therapy are feasible and effective in improving upper limb motor function and reducing spasticity in individuals with chronic spastic hemiparesis. However, the cyclic FES protocol used in this study did not increase gains achieved with the combination of OnabotulinumtoxinA and task practice alone.

Keywords: Botulinum toxin, Electric stimulation, Muscle spasticity, Recovery of Function, Rehabilitation, Stroke

Stroke is the leading cause of disability in the United States, with an estimated 795,000 new or recurrent cases of stroke each year 1. About 55% to 75% of stroke survivors sustain impaired upper extremity function, although with routine interventions, only about 12% of survivors recover fully within 6 months of injury 2, 3. Unfortunately, the vast majority continue to experience upper extremity impairment 6 months post-stroke and beyond, with little or no prospect for additional motor improvement after that.

Task-oriented practice is effective for promoting motor recovery after chronic stroke and traumatic brain injury 4, 5. In clinical practice, task-practice protocols involve the development of home exercise programs using 4 to 5 activities chosen by the therapist to match the patient’s interests. However, the level and quality of participation in task practice activities may be limited for individuals with moderate to severe muscle weakness and/or spasticity, prompting the need for adjunctive treatments to augment hand grasp function during activity-based training.

Concurrent treatments for muscle spasticity and weakness have the potential to improve gains made during task practice in individuals with spasticity. For example, intramuscular injections of OnabotulinumtoxinA, an US Food and Drug Administration-approved medication for cervical dystonia that blocks the release of acetylcholine at the neuromuscular junction 6, can temporarily decrease muscle spasticity. In addition, FES can strengthen weaker muscles and is frequently used in clinical practice 7, 8. Cyclic FES (FES) involves a fixed timing pattern of stimulation for specified muscle groups, for example, to produce alternating cycles of flexion and extension actions to aid grasp and release of objects.

Thus, a rehabilitation program that combines OnabotulinumtoxinA injections, task practice and FES treatments may enhance motor performance by simultaneously targeting multiple mechanisms impeding recovery. In fact, clinical practice rarely relies on a single intervention to treat a complex condition, and prior studies have shown that interventions based soley on OnabotulinumtoxinA injections or occupational therapy alone provide limited benefit for improving hand function in persons with chronic spastic hemiparesis 9. However, a recent report suggests that the combination of task practice and OnabotulinumtoxinA is associated with improvements in upper limb quality of movement among individuals with chronic spastic hemiparesis 10.

The present study was designed to determine if outcomes for hand function are improved by adding FES to our standard intervention, which consists of OnabotulinumtoxinA injections and task practice therapy. Our hypothesis is that the addition of FES to our standard intervention will increase the magnitude and durability of improvements in hand grasp and release motor function among individuals with spastic hemiparesis.

METHODS

The University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board approved all protocols for this study.

Participants

This was a single-blinded randomized controlled pilot study. We recruited a convenience sample of individuals with chronic hemiparesis from the Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Spasticity Clinic at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center. All participants had a minimum of 6 months of unilateral spastic hemiparesis and had at least 2 prior sessions of OnabotulinumtoxinA injections for treatment of spasticity. This prior exposure confirmed that participants tolerated injection therapy without adverse reactions with a predictable dosage. Subjects had pre-injection Modified Ashworth scores 2 or greater in at least 1 of the following muscle groups: wrist flexors or finger flexors. Additionally, they had to attain at minimum a Stage 2 classification on the Chedoke McMaster Assessment of hand impairment 11, plus demonstrate the ability to do at least 1 of the following Stage 3 tasks: active wrist extension greater than half range, active finger/wrist flexion greater than half range, or actively touch thumb to index finger when the hand was placed in supination with thumb fully extended. Participants without any voluntary motion or severe fixed joint contracture in the affected arm were excluded. Although participants were required to have some voluntary motor function in the hand, these criteria were used to select people that were unable to reliably grasp and release objects prior to treatment.

A masked trained evaluator administered baseline assessments for each outcome measure after obtaining informed consent and determining whether participants met inclusion criteria. Participants meeting the inclusion criteria were assigned randomly to 1 of 2 groups. The No-FES group received our standard intervention consisting of OnabotulinumtoxinA injections and task practice therapy, while the FES group received FES in addition to the standard intervention. Outcomes were measured at 3 time-points: baseline (pre-injection), week-6, and week-12 post-injection.

Standard intervention: OnabotulinumtoxinA injections and task practice therapy (both groups)

Participants in both groups received OnabotulinumtoxinA injections performed by an experienced physician (MCM) as part of clinical management for spasticity within 2 weeks after baseline assessment. All patients were positioned supine with the arm abducted and forearm supinated as much as feasible. Muscles were localized using a combination of EMG guidance or ultrasound direct visualization procedures for forearm flexor muscles. The individual bellies of the flexor digitorum superificalis were injected separately 12, and all other muscles had 1 injection site. All doses of the toxin were prepared using a 1:1 dilution.

Within 7 days following OnabotulinumtoxinA treatment, participants in both groups attended an initial instructional visit with an occupational therapist involved in this study (LH). During the initial visit, participants received 1 hour of therapy that included instructions for the home exercise program, and instruction on how to complete a daily patient exercise diary. Participants in the FES group received 1 additional hour of therapy so that they could be fitted and trained to use the H200 devicea.

The post-injection intervention for both groups included a home exercise program that required a total of 60 minutes of task practice daily for 12 weeks using a standardized protocol without constraining the unimpaired arm. Participants were encouraged to set aside a target of 60 minutes per day to devote to their home exercise program, incorporating rest breaks between tasks as needed. We selected 60 minutes per day based on our experience in implementing task practice protocols clinically in our facility. We selected 12 weeks given the expected duration of therapeutic effects provided by the OnabotulinumtoxinA injections 13. The task practice home exercise program was developed by an experienced occupational therapist (LH) and consisted of 4 to 5 functional tasks that were selected in collaboration with the participants according to their interests and abilities. Examples included stacking canned goods, dealing cards, sorting pennies, and wiping down counters. Participants practiced their individiually-designed task practice programs for 60 minutes per day with rest breaks as needed. The implementation of these home exercise programs was monitored during 5 additional 1-hour visits with the occupational therapist to ensure that the participants could complete the program independently without difficulty.

Experimental treatment: Cylic FES (FES group only)

Participants in the FES group were fitted with an H200 device during their initial OT visit. A detailed description of the device can be found elsewhere 14. The device consists of a battery powered programmable stimulator and a forearm-wrist-hand orthosis containing 5 electrodes positioned to provide reliable activation of the following muscles: extensor digitorum communis and extensor pollicis brevis, flexor pollicis longus, flexor digitorum superficialis, and thenar muscles. The size and location of each electrode were custom fit to each patient following procedures recommeded by the manufacturer (Bioness, Inc.a). The intensity of stimulation was set to a level that provided comfortable and consistent activation of the extensor and flexor muscles to achieve whole hand opening and functional grasping. Reliable functioning of the device was verified by the occupational therapist during subsequent visits, and adjustments to the device fit and/or stimulation settings were maded if necessary to achieve complete hand opening and grasping. We did not employ FES to augment the uptake of OnabotulinumtoxinA within muscles immediately after injection.15

The H200 devices were programmed to provide for 60 minutes of exercise during the task practice activities. Each stimulation cycle consisted of a 5-second period of ‘extensor’ stimulation, followed by a 5-second period of ‘flexor’ stimulation and a 2-second rest period. Participants in the FES group were instructed to coordinate their actions with the pre-timed stimulation patterns programmed in the H200 device so as to synchronize the user’s intention with FES-assistance. For example, during the extension phase, participants moved their hand in position to grasp the object for their task. Grasp assistance was provided by electrical stimulation during the flexion phase, completing one full cycle of stimulation with each repetition of the task. Although the stimulation cycles were fixed, participants needed to engage actively in the tasks to produce the synergistic muscle actions throughout the upper limb requisite to effective task performance. During the initial and subsequent OT visits, performance of the FES-assisted task practice activities was monitored to ensure that participants were achieiving reliable coordination between FES and hand grasp and release activities, and that adequate rest breaks were included as needed.

Outcome Assessments

Outcomes for motor function and spasticity were assessed at baseline (2 weeks prior) and 6 and 12 weeks after OnabotulinumtoxinA injections. Week-6 was chosen as the primary endpoint for assessing gains in function, while the week-12 time point was used to assess the durability of those gains.

Primary outcomes were upper extremity function during activities of daily living assessed observationally by masked, trained evaluators on the “How Well Scale” of the MAL-Observation. Prior to beginning this study, we standardized the administration and scoring of each MAL item through observation, developed an administration manual (available from the authors) and trained the masked evaluator to inter-rater reliability (intraclass correlation coefficient=.97) with the occupational therapy researcher on the team (ES).

Secondary outcomes were (a) dexterous hand function as measured by the ARAT, and (b) patient’s perception of self-performance in activities of daily living assessed with the MAL-Self-Report. Previous studies have reported on the reliability and validity of these secondary outcome measures 16-19. A masked evaluator trained in administering each of these measures conducted all evaluations.

Adherence Monitoring

Adherence to the task practice program was assessed through home diary records in both groups, and through the electronic log in the FES group. The home diary contained pre-printed forms listing the prescribed task practice program. Individuals were required to document the amount of time and frequency of repetitions of each prescribed activity on a daily basis. For the individuals in the FES group, these data were compared with the automatic tracking feature of the H200 device, which provided an electronic log of device use. The treating occupational therapist (LH) reviewed the home diaries and electronic activity logs during the 6 treatment sessions and again at each follow-up assessment to assure adherence to the task practice program at home.

Data Analysis

Analysis was done on the basis of intent-to-treat. We calculated average scores for each outcome measure, including MAL-Observation, ARAT, and MAL-Self-Report. We performed bivariate (Mann Whitney and chi-square, as appropriate) analyses to compare the demographic and baseline variables between the FES and the No-FES groups. Because the FES group was significantly older than the No-FES group, we controlled for age in our analyses. We used mixed effects model analyses 20 to evaluate the differences in outcome variables between the No-FES and FES groups at the baseline, week-6, and week-12 time points. We verified the normality assumption for MAL-Observation, MAL-Self-Report, and ARAT using the 1-sample Kolmogorov-Simirnov test. There was no violation of this assumption for any of the outcome variables. We controlled for multiple testing using the Benjamini and Hochberg correction methods 21. Analyses were performed using SPSS v16b and R softwarec.

RESULTS

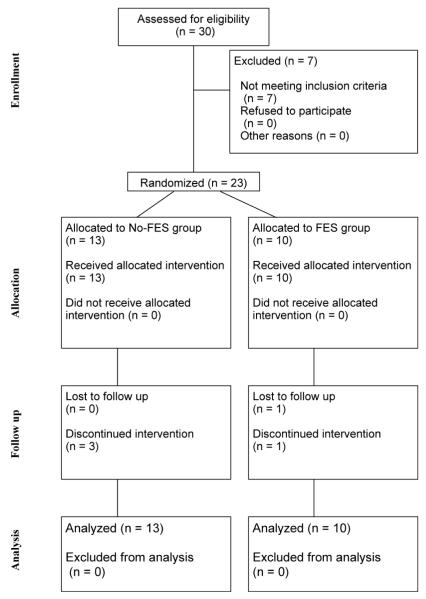

Thirty participants were enrolled in the study, but 7 did not meet the minimum requirements for hand function (Chedoke McMaster Assessment >= 2). A CONSORT diagram showing the enrollment and group assignments appears in figure 1. Thirteen people were randomized to the No-FES group, and 10 people were randomized to the FES group. Three participants withdrew from the No-FES group citing decline in health status (n=2) and personal reasons (n=1). One person withdrew from the FES group citing personal reasons, and 1 person was not available for the week-6 and week-12 outcome assessments. Thus, a total of 18 participants completed the study, 10 in the No-FES group and 8 in the FES group. There were no significant differences at baseline between those who completed the study and those who dropped out on any of the outcome measures. Because mixed effect models do not assume balanced data, our analysis was based on the full sample (N = 23).

Figure 1.

CONSORT diagram.

There were no significant differences between No-FES and FES groups in terms of gender, time since injury, total OnabotulinumtoxinA dose, baseline Chedoke McMaster Assessment scores, or baseline MAS scores (table 1). On average, participants in the No-FES group were significantly younger (p = 0.03) than participants in the FES group. While there were differences in etiology between TBI and stroke, all subjects had to meet the same inclusion critierion with respect to cogntive function (i.e., abiltiy to reliably follow 3-step instructions) in order to participate in the rehabilitation protocol. Thus, given that all other major baseline variables were similar between treatment groups, the etiologic differences between stroke and TBI are mitigated since all subjects had spastic hemiparesis without severe cognitive deficits. A complete description of muscles injected and mean doses per muscle is listed in table 2.

Table 1.

Participant Demographics and Clinical Characteristics.

| No-FES (n=13) | FES (n=10) | Test Statistic | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female, % | 62 | 70 | Χ21=.18, p=.67 |

| Age (y) (SD) | 41.2 (14.2) | 54.0 (10.3) | T21=−2.51, p=.03 |

| Race | |||

| White, % | 92.3 | 90 | Χ21=.04, p=.85 |

| Black, % | 7.7 | 10 | |

| Chronicity (y) (SD) | 4.3 (2.5) | 9.7 (8.6) | T10=−1.92, p=.08 |

| Diagnosis | |||

| Stroke, % | 61 | 100 | |

| Traumatic Brain Injury, % | 39 | 0 | Χ21=1.89, p=.16 |

| Location of insult | |||

| Cortical, % | 92.3 | 100 | |

| Subcortical, % | 7.7 | 0 | Χ21=.80, p=.37 |

| OnabotulinumtoxinA dose, | |||

| units, (SD) | 251.8 (123.5) | 328.6 (90.6) | T21=−1.65,p = .11 |

| Baseline Measures | |||

| MAL-O, (SD) | 1.11 (.87) | .96 (.84) | T21=.43, p=.68 |

| MAS-SR, (SD) | 1.55 (.96) | 1.17 (.74) | T21=1.02,p=.32 |

| ARAT, (SD) | 25.8 (15.5) | 19.5 (13.9) | T21=1.00, p=.33 |

| MAS-Wrist, median (IQR) | 3 (2,3) | 3 (3,4) | Z=−.57,p=.61 |

| MAS-Fingers, median (IQR) | 3(2,3) | 3(3,3) | Z=−.95,p=.41 |

NOTE. Data represent mean and SD except where indicated. No-FES: subjects who received OnabotulinumtoxinA injections and task practice therapy. FES: subjects who received Cylic FES in addition to OnabotulinumtoxinA injections and task practice therapy.

Abbreviations: IQR, interquartitle range; MAS, Modified Ashworth scales; MAL-O, Motor Activity Log Observation; MAL-SR, Motor Activity Log Self-Report.

Table 2.

Average OnabotulinumtoxinA Dose Per Muscle Injected Within Each Treatment Group.

| No-FES | FES | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Muscle | N | Mean | SEM | N | Mean | SEM | 95% CI of the Difference |

| PT | 5 | 38.0 | 4.9 | 8 | 42.5 | 4.5 | [−19.8, 10.8] |

| FCR | 6 | 36.7 | 3.3 | 8 | 33.8 | 2.6 | [−6.2, 12.0] |

| FCU | 5 | 24.0 | 5.1 | 2 | 20.0 | 10.0 | [−21.8, 29.8] |

| FDS | 13 | 66.5 | 10.6 | 9 | 75.0 | 7.7 | [−38.3, 21.4] |

| FDP | 13 | 35.0 | 5.0 | 9 | 33.4 | 6.6 | [−15.5, 18.6] |

| FPL | 9 | 14.4 | 2.9 | 5 | 14.0 | 2.4 | [−9.1, 10.0] |

NOTE. Data listed in the table are mean with SEM. There are no significant differences between the 2 groups since all CI include zero.Other muscles, such as lower limb muscles, may have been injected but are not shown. No-FES: subjects who received OnabotulinumtoxinA injections and task practice therapy. FES: subjects who received Cylic FES in addition to OnabotulinumtoxinA injections and task practice therapy.

Abbreviations: FCR, flexor carpi radialis; FCU, flexor carpi ulnaris; FDP, flexor digitorum profundus; FDS, flexor digitorum superficialis; FPL, flexor pollicis longus; PT, pronator teres;SEM,standard error of the mean.

Outcomes for Motor Function

Table 3 lists the mean, standard error, and 95% CI for MAL-Observation, MAL-Self-Report, and the ARAT scores at baseline, week-6, and week-12 timepoints for both groups. The MAL-Observation and ARAT scores at baseline were slightly higher in the No-FES group, but the differences were not significant as indicated by the considerable overlap in the 95% CI for the No-FES and FES groups. Over time, there were no significant differences between treatment groups for any outcome measure.

Table 3.

Average Scores for MALO, MALSR and ARAT at Each Time Point and by Treatment Group

| Baseline | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No-FES | FES | |||||

| Mean | SEM | 95% CI | Mean | SEM | 95% CI | |

| MALO | 1.55 | 0.27 | [0.97, 2.13] | 1.17 | 0.23 | [0.65, 1.70] |

| MALSR | 1.11 | 0.24 | [0.58, 1.64] | 0.96 | 0.26 | [0.36, 1.56] |

| ARAT | 25.77 | 4.29 | [16.42, 35.12] | 19.50 | 4.40 | [9.54, 29.46] |

| Week 6 | ||||||

| MALO | 2.01 | 0.26 | [1.42, 2.59] | 1.61 | 0.32 | [0.86, 2.36] |

| MALSR | 1.74 | 0.23 | [1.22, 2.27] | 1.77 | 0.34 | [0.96, 2.58] |

| ARAT | 30.50 | 4.92 | [19.38, 41.62] | 25.13 | 5.32 | [12.54, 37.71] |

| Week 12 | ||||||

| MALO | 1.79 | 0.26 | [1.2, 2.37] | 1.52 | 0.37 | [0.63, 2.40] |

| MALSR | 1.71 | 0.30 | [1.04, 2.38] | 1.85 | 0.42 | [0.86, 2.84] |

| ARAT | 31.40 | 5.54 | [18.86, 43.94] | 23.50 | 6.21 | [8.83, 38.17] |

NOTE. Data repesent mean plus SEM. There are no significant differences between treatment groups at any time point. No-FES: subjects who received OnabotulinumtoxinA injections and task practice therapy. FES: subjects who received Cylic FES in addition to OnabotulinumtoxinA injections and task practice therapy.

Abbreviations: MALO, Motor Activity Log Observation; MALSR, Motor Activity Log Self-Report; SEM, standard error of the mean.

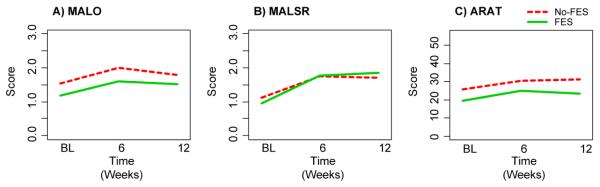

Figure 2 shows trends in group-averaged scores for the 3 outcome variables. Positive trends for all 3 outcomes are shown for both groups from baseline to week-6. There is a slight, but insignificant trend toward an improvement in MAL-Self-Report scores for the FES group from week-6 to week-12, while the No-FES group exhibits a weak, but insignificant trend toward deterioration. Conversely, the ARAT scores exhibit a slight, but insignificant trend toward deterioration from week-6 to week-12 in the FES group, while the trend for the No-FES group shows a slightly positive slope.

Figure 2.

Outcomes for motor function change over time. Plots show the group averages at BL, week-6 and week-12 time points. Note: MALO and MALSR scores represent mean item score (range 0 – 5). ARAT scores represent total scale score (range 0 – 57). No-FES: subjects who received OnabotulinumtoxinA injections and task practice therapy. FES: subjects who received Cylic FES in addition to OnabotulinumtoxinA injections and task practice therapy. Abbreviations: BL, baseline; MALO, Motor Activity Log-Observation; MALSR, Motor Activity Log-Self-Report.

The No-FES and FES groups did not differ significantly for any outcome variable at any time point, so we collapsed the data across groups to examine changes in outcome scores for the entire cohort. Average changes in outcome variables for the entire cohort from baseline to week-6 and baseline to week-12 are summarized in table 4. The 95% CI data in Table 4 show that significant improvements in all 3 outcomes were observed at week-6, and the MAL-Self-Report and ARAT improvements were sustained at week-12. Although a slight increase in the mean MAL-Observation score was observed from baseline to week-12, the improvement was not significant.

Table 4.

Overall Improvement of the Entire Cohort from Baseline to 6 Weeks and From Baseline to 12 Weeks.

| Baseline to Week-6 Improvement | |||

| Mean Difference | SEM | 95% CI | |

| MALO | 0.41 | 0.08 | [0.24, 0.58] |

| MALSR | 0.64 | 0.15 | [0.32, 0.95] |

| ARAT | 6.39 | 1.43 | [3.38, 9.40] |

| Baseline to Week-12 Improvement | |||

| MALO | 0.25 | 0.14 | [−0.05, 0.54] |

| MALSR | 0.65 | 0.15 | [0.33, 0.97] |

| ARAT | 6.17 | 1.83 | [2.31, 10.03] |

NOTE. All measeures show significant improvement except for MALO from baseline to week-12 (CI includes zero). Data repesent mean plus SEM. No-FES: subjects who received OnabotulinumtoxinA injections and task practice therapy. FES: subjects who received Cylic FES in addition to OnabotulinumtoxinA injections and task practice therapy.

Abbreviations: MALO, Motor Activity Log Observation; MALSR, Motor Activity Log Self-Report; SEM, standard error of the mean.

The interaction between group and time were not significant for any of the outcome variables, so we concluded that the FES group did not improve significantly more than the No-FES group. Interestingly, the self-reported MAL-Self-Report mean item scores for both groups showed the largest increase, nearly a full point, from baseline to week-12, with a slight albeit insignificant increase between week-6 and week-12. Thus, participants in both groups indicated a strong perceived increase in hand function that was sustained through the full 12-week course of the study.

Adherence to Home Exercise Program

Data from the home diary and electronic logs (for the FES group) indicate that the task practice program was very practical, and that most participants were able to adhere to the required daily practice schedule for the full duration of the 12-week study. Participants in the No-FES group practiced an average of 53 minutes per day (SD=7), whereas participants in the FES group practiced an average of 48 minutes per day (SD=6). For the participants in the FES group, the electronic logs supported the home diary data.

DISCUSSION

The primary aim of this study was to examine whether the addition of FES to a rehabilitation program consisting of OnabotulinumtoxinA and task practice improved upper limb motor function among individuals with chronic spastic hemiparesis. Although several previous studies have shown that treatment with OnabotulinumtoxinA alone is effective in reducing spasticity after stroke, improvements in upper limb motor function in moderately to severely impaired chronic stroke survivors was not reported or not significant 22-24. Our findings showed improved motor outcomes at 6 weeks with the primary outcome measure (MAL-Observation) and improved secondary motor outcomes (MAL-Self-Report and ARAT) at both 6-week and 12-week endpoints for the entire cohort. However, we did not observe additional motor recovery in those individuals randomized to receive FES in addition to OnabotulinumtoxinA and task practice treatments.

The motivation for testing the benefits of FES was to determine if electrical stimulation could augment the grasp and release actions of the hand during task practice activities in individuals who could not reliably grasp and release objects on their own due to hemiparesis. Thus, we examined whether the addition of FES improved the quality and recovery of hand function during training. The Bioness H200 device was selected for this study, because it is designed for easy donning and doffing, making it suitable for participants to take home and use reliably on a daily basis 25-26. The rationale for combining FES, OnabotulinumtoxinA, and task practice was that boosting muscle contractile force with FES and relaxing spasticity with OnabotulinumtoxinA would improve motor performance during task practice training. Indeed, our results demonstrated that the combination of OnabotulinumtoxinA and task practice enabled individuals with spasticity to participate effectively in task practice training. On average, participants completed over 50 minutes/day of training during their in-home exercise protocol.

At baseline, the participants in our study exhibited moderate to severe spasticity in the fingers and wrist (MAS >= 2.5) and were generally low functioning (MAL-Observation < 2 and ARAT < 30); yet, all participants were able to perform their task practice activities after OnabotulinumtoxinA injections and achieved significant gains in hand function. The improvements in motor function exhibited at the week-6 and week-12 time points are clinically meaningful based on the study reported by Lang et al 27. Their data indicates that a change in upper extremity function above 16% to 30% from baseline constitutes a ‘minimal clinically important difference’ for people with hemiparesis early after stroke, and that even smaller changes may be clinically important for participants with chronic hemiparesis27. At week-12, 118% and 42% gains were measured in MAL-Self-Report and ARAT respectively, and both increases were statistically significant.

Study Limitations

This study was designed to evaluate the importance of FES in combination with OnabotulinumtoxinA injections and 12 weeks of daily task practice. Although the group sizes in the present study were small (n = 13 and n = 10 in the No-FES and FES groups, respectively), the entire cohort achieved significant improvements in all measures of motor function at the primary endpoint (week-6). A larger sample size may have been more effective in detecting group differences between the FES and No-FES treatments.

We did not control for the effects of OnabotulinumtoxinA in our study because the goal was to examine the combined synergistic effects of FES in augmenting task practice training after chemodenervation. While it is noteworthy that all participants demonstrated significant improvements in all measures of hand function at the primary endpoint (week-6), future studies are needed to identify the relative importance of task practice training and OnabotulinumtoxinA in achieving these gains.

In general, the randomization procedure was effective in balancing the 2 groups on baseline scores for motor function. Although all participants with TBI were randomized to the No-FES group, they met the same criteria for cognitive function and could understand and follow instructions for completing the home exercise program. Adherence to the program was verified by records in the home diary for both groups. Thus, the higher proportion of persons with TBI in the No-FES group had minimal if any impact on the outcomes of this study.

Another limitation is that the H200 device does not provide for direct pairing of the user’s intentions with specific stimulation patterns. This synchronization between voluntary actions in the neuromuscular system with the desired effect is important for achieving the ‘Hebbian-type’ neural plasticity that is sought to promote functional recovery28,29. Although the H200 provides a pushbutton switch for triggering pre-timed phases of flexion or extension stimulation 30, this indirect mode of coordination still does not achieve the goal of synchronizing stimulation with activity in muscles targeted for rehabilitation. EMG-triggered FES is one method for directly coordinating FES patterns with the user’s intention to contract specific muscle groups31,32, although the benefits of EMG-triggered FES over cyclic FES are not certain33.

It is possible that some decline in motor function scores is due to a wearing-off of the therapeutic effect of OnabotulinumtoxinA, which generally lasts for 9-12 weeks with the doses used in this study. Alternatively, discontinuation of OT sessions after week-6 may have contributed to a failure to maintain MAL-Observation improvements achieved during the first half of the study period. Nevertheless, all of the secondary measures for motor function remained significantly improved at week-12, although long-term follow-up is needed to determine the chronic durability of these improvements.

CONCLUSIONS

This study demonstrated improved upper limb motor function using a combined intervention approach in a sample of individuals with chronic, moderate to severe spastic hemiparesis. While the sample is small, these results are important in demonstrating that these combinatorial approaches are feasible and effective in this population. Although we are unable to make strong statements about the superiority of one approach over another, our findings support the inclusion of OnabotulinumtoxinA injections and task practice training as components of a therapeutic ‘cocktail’ to improve upper limb motor function. Additional studies are needed to determine optimal strategies for improving motor function in adults with chronic spasticity.

Acknowledgments

Supported by an unrestricted grant from Allergan, Inc.; the National Institutes of Health Post-Doctoral Training grants (Training Rehabilitation Clinicians for Research Careers, grant no. T32 HD049307) and Career Development Training (Comprehensive Opportunities for Rehabilitation Research Training, grant no. K12 HD055931). Additional support was provided by NIH from the NIBIB (grant no. 1R01EB007749) and NINDS (grant no. 1R21NS056136) and the Telemedicine and Advanced Technology Research Center (TATRC) U.S. Army Medical Research and Material Command Agreement (no. W81XWH-07-1-0716).

Abbreviations

- ARAT

Action Research Arm Test

- CI

confidence intervals

- EMG

electromyogram

- FES

functional electrical stimulation

- MAL

Motor Activity Log

- OT

occupational therapy

- TBI

traumatic brain injury

Footnotes

No commercial party having a direct financial interest in the results of the research supporting this article has or will confer a benefit on the authors or on ay organization with which the authors are associated.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Suppliers Bioness Inc, 25103 Rye Canyon Loop, Valencia, CA 91355.

SPSS Inc, 233 S Wacker Dr, 11th Fl, Chicago, IL 60606.

The R Foundation for Statistical Computing c/o Department of Statistics and Mathematics Wirtschaftsuniversitat Wien Augasse 2-6 1090 Vienna, Austria.

References

- 1.Lloyd-Jones D, Adams R, Carnethon M, De Simone G, Ferguson TB, Flegal K, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics--2009 update: a report from the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Circulation. 2009;119(3):e21–181. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.191261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nakayama H, Jorgensen HS, Raaschou HO, Olsen TS. Recovery of upper extremity function in stroke patients: the Copenhagen Stroke Study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1994;75(4):394–8. doi: 10.1016/0003-9993(94)90161-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kwakkel G, Kollen BJ, van der Grond J, Prevo AJ. Probability of regaining dexterity in the flaccid upper limb: impact of severity of paresis and time since onset in acute stroke. Stroke. 2003;34(9):2181–6. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000087172.16305.CD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wolf SL, Winstein CJ, Miller JP, Thompson PA, Taub E, Uswatte G, et al. Retention of upper limb function in stroke survivors who have received constraint-induced movement therapy: the EXCITE randomised trial. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7(1):33–40. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70294-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Duncan P, Studenski S, Richards L, Gollub S, Lai SM, Reker D, et al. Randomized clinical trial of therapeutic exercise in subacute stroke. Stroke. 2003;34(9):2173–80. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000083699.95351.F2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rousseaux M, Kozlowski O, Froger J. Efficacy of botulinum toxin A in upper limb function of hemiplegic patients. J Neurol. 2002;249(1):76–84. doi: 10.1007/pl00007851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chae J, Bethoux F, Bohine T, Dobos L, Davis T, Friedl A. Neuromuscular stimulation for upper extremity motor and functional recovery in acute hemiplegia. Stroke. 1998;29(5):975–9. doi: 10.1161/01.str.29.5.975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Billian C, Gorman PH. Upper extremity applications of functional neuromuscular stimulation. Assist Technol. 1992;4(1):31–9. doi: 10.1080/10400435.1992.10132190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brashear A, Gordon MF, Elovic E, Kassicieh VD, Marciniak C, Do M, et al. Intramuscular injection of botulinum toxin for the treatment of wrist and finger spasticity after a stroke. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(6):395–400. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meythaler JM, Vogtle L, Brunner RC. A preliminary assessment of the benefits of the addition of botulinum toxin a to a conventional therapy program on the function of people with longstanding stroke. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;90(9):1453–61. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2009.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gowland C, Stratford P, Ward M, Moreland J, Torresin W, Van Hullenaar S, et al. Measuring physical impairment and disability with the Chedoke-McMaster Stroke Assessment. Stroke. 1993;24(1):58–63. doi: 10.1161/01.str.24.1.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Munin MC, Navalgund BK, Levitt DA, Breisinger TP, Zafonte RD. Novel approach to the application of botulinum toxin to the flexor digitorum superficialis muscle in acquired brain injury. Brain Inj. 2004;18(4):403–7. doi: 10.1080/02699050310001617334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yablon SA. Botulinum neurotoxin intramuscular chemodenervation. Role in the management of spastic hypertonia and related motor disorders. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2001;12(4):833–74. vii–viii. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Snoek GJ, MJ IJ, Groen FA in ’t, Stoffers TS, Zilvold G. Use of the NESS handmaster to restore handfunction in tetraplegia: clinical experiences in ten patients. Spinal Cord. 2000;38(4):244–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3100980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frasson E, Priori A, Ruzzante B, Didone G, Bertolasi L. Nerve stimulation boosts botulinum toxin action in spasticity. Mov Disord. 2005;20(5):624–9. doi: 10.1002/mds.20395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van der Lee JH, Beckerman H, Lankhorst GJ, Bouter LM. The responsiveness of the Action Research Arm test and the Fugl-Meyer Assessment scale in chronic stroke patients. J Rehabil Med. 2001;33(3):110–3. doi: 10.1080/165019701750165916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Platz T, Pinkowski C, van Wijck F, Kim IH, di Bella P, Johnson G. Reliability and validity of arm function assessment with standardized guidelines for the Fugl-Meyer Test, Action Research Arm Test and Box and Block Test: a multicentre study. Clin Rehabil. 2005;19(4):404–11. doi: 10.1191/0269215505cr832oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Uswatte G, Taub E, Morris D, Light K, Thompson PA. The Motor Activity Log-28: assessing daily use of the hemiparetic arm after stroke. Neurology. 2006;67(7):1189–94. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000238164.90657.c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van der Lee JH, Beckerman H, Knol DL, de Vet HC, Bouter LM. Clinimetric properties of the motor activity log for the assessment of arm use in hemiparetic patients. Stroke. 2004;35(6):1410–4. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000126900.24964.7e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chakraborty H, Gu H. A Mixed Model Approach for Intent-to-Treat Analysis in Longitudinal Clinical Trials with Missing Values. RTI Press Methods Report Series. 2009 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series B (Methodological) 1995:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Simpson DM, Alexander DN, O’Brien CF, Tagliati M, Aswad AS, Leon JM, et al. Botulinum toxin type A in the treatment of upper extremity spasticity: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Neurology. 1996;46(5):1306–10. doi: 10.1212/wnl.46.5.1306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smith SJ, Ellis E, White S, Moore AP. A double-blind placebo-controlled study of botulinum toxin in upper limb spasticity after stroke or head injury. Clin Rehabil. 2000;14(1):5–13. doi: 10.1191/026921500666642221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sheean GL. Botulinum treatment of spasticity: why is it so difficult to show a functional benefit? Curr Opin Neurol. 2001;14(6):771–6. doi: 10.1097/00019052-200112000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hendricks HT, MJ IJ, de Kroon JR, Groen FA in ’t, Zilvold G. Functional electrical stimulation by means of the ‘Ness Handmaster Orthosis’ in chronic stroke patients: an exploratory study. Clin Rehabil. 2001;15(2):217–20. doi: 10.1191/026921501672937235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Page SJ, Maslyn S, Hermann VH, Wu A, Dunning K, Levine PG. Activity-based electrical stimulation training in a stroke patient with minimal movement in the paretic upper extremity. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2009;23(6):595–9. doi: 10.1177/1545968308329922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lang CE, Edwards DF, Birkenmeier RL, Dromerick AW. Estimating minimal clinically important differences of upper-extremity measures early after stroke. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2008;89(9):1693–700. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2008.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Khaslavskaia S, Sinkjaer T. Motor cortex excitability following repetitive electrical stimulation of the common peroneal nerve depends on the voluntary drive. Exp Brain Res. 2005;162(4):497–502. doi: 10.1007/s00221-004-2153-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chae J. Neuromuscular electrical stimulation for motor relearning in hemiparesis. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2003;14(1 Suppl):S93–109. doi: 10.1016/s1047-9651(02)00051-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alon G, McBride K. Persons with C5 or C6 tetraplegia achieve selected functional gains using a neuroprosthesis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2003;84(1):119–24. doi: 10.1053/apmr.2003.50073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cauraugh JH, Kim S. Two coupled motor recovery protocols are better than one: electromyogram-triggered neuromuscular stimulation and bilateral movements. Stroke. 2002;33(6):1589–94. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000016926.77114.a6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.von Lewinski F, Hofer S, Kaus J, Merboldt KD, Rothkegel H, Schweizer R, et al. Efficacy of EMG-triggered electrical arm stimulation in chronic hemiparetic stroke patients. Restor Neurol Neurosci. 2009;27(3):189–97. doi: 10.3233/RNN-2009-0469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.de Kroon JR, MJ IJ. Electrical stimulation of the upper extremity in stroke: cyclic versus EMG-triggered stimulation. Clin Rehabil. 2008;22(8):690–7. doi: 10.1177/0269215508088984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]