Abstract

Objective

Despite proven efficacy of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) for treating eating disorders with binge eating as the core symptom, few patients receive CBT in clinical practice. Our blended efficacy-effectiveness study sought to evaluate whether a manual-based guided self-help form of CBT (CBT-GSH), delivered in 8 sessions in a Health Maintenance Organization setting over a 12-week period by masters level interventionists, is more effective than treatment as usual (TAU).

Method

In all, 123 individuals (mean age = 37.2, 91.9% female, 96.7% non-Hispanic White) were randomized, including 10.6% with bulimia nervosa (BN), 48% with Binge Eating Disorder (BED), and 41.4% with recurrent binge eating in the absence of BN or BED. Baseline, post-treatment, and 6- and 12 month follow-up data were used in intent-to-treat analyses. At 12-month follow-up, CBT-GSH resulted in greater abstinence from binge eating (64.2%) than TAU (44.6%, Number Needed to Treat = 5), as measured by the Eating Disorder Examination (EDE, Fairburn & Cooper, 1993). Secondary outcomes reflected greater improvements in the CBT-GSH group in dietary restraint (d = .30), eating-, shape-, and weight concern (d’s = .54, 1.01, .49) (measured by the EDE-Questionnaire, respectively, Fairburn & Beglin, 2008), depression (d = .56) (Beck Depression Inventory, Beck, Steer, & Garbin, 1988), and social adjustment (d = .58) (Work and Social Adjustment Scale, Mundt, Marks, Shear, & Greist, 2002), but not weight change.

Conclusions

CBT-GSH is a viable first-line treatment option for the majority of patients with recurrent binge eating who do not meet diagnostic criteria for BN or anorexia nervosa.

Keywords: binge eating, cognitive behavior therapy, guided self-help, effectiveness

Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) has been shown to be an effective treatment for bulimia nervosa (BN) and binge eating disorder (BED) (Brownley, Berkman, Sedway, Lohr, & Bulik, 2007; Shapiro et al., 2007; Wilson, Grilo, & Vitousek, 2007) and has been recommended as the psychological treatment of choice for these disorders (Wilson & Shafran, 2005). Yet, only a minority of patients receives this treatment (Currin, et al., 2007; Mussell et al., 2000) and, indeed, only a minority of individuals receives any mental health treatment specifically targeting the eating disorder (Grilo et al., 2008; Mond, Hay, Rodgers, & Owen, 2007; Striegel-Moore et al., 2008; Striegel-Moore, Leslie, Petrill, Garvin, & Rosenheck, 2000) despite strong evidence of psychosocial and health impairments associated with these disorders (Lewinsohn, Striegel-Moore, & Seeley, 2000; Mond & Hay, 2007; Mond, Hay, Rodgers, & Owen, in press; Striegel-Moore, Seeley, & Lewinsohn, 2003). Numerous barriers have been described that may explain underutilization of mental health services in general, and the recommended treatment (CBT) in particular (Cachelin & Striegel-Moore, 2006; Sysko & Walsh, 2008; Wang et al., 2005).

Experts have noted the dearth of clinicians trained in delivery of CBT treatment as well as the intensity or cost of CBT which requires 20 50-minute sessions to be provided over a period of five months (Fairburn, 2008; Wilson, Wilfley, Agras, & Bryson, in press). To ensure cost-effective allocation of scarce treatment resources, experts have called for a “stepped care” approach to the treatment of eating disorders with less intensive treatments as the first step and more intensive treatments reserved for those who fail to respond (Perkins, Murphy, Schmidt, & Williams, 2006; Wilson, Vitousek, & Loeb, 2000). Several studies have shown that brief, readily disseminable guided self-help approaches based on cognitive behavioral principles (CBT-GSH) have been shown to be effective in the treatment of both BN (e.g., Banasiak, Paxton, & Hay, 2007; Mitchell et al., 2006) as well as BED (e.g., Grilo & Masheb, 2005; Wilson et al., in press). The superiority of CBT-GSH for BED over behavioral weight loss (BWL) treatment in the later two studies provides evidence of the specificity of its effects. Specifically, in a randomized clinical trial of 90 individuals with BED, Grilo and Masheb (2005) found that CBT-GSH had significantly higher treatment completion rates (indicating greater acceptability) and abstinence from binge eating rates (indicating greater efficacy) than BWL. Similarly, a randomized clinical trial comparing the efficacy of a 10-session CBT-GSH program and a 20-session BWL program for the treatment of BED found significantly greater abstinence from binge eating in CBT-GSH (Wilson et al., in press).

Efficacy studies on CBT-GSH have focused on BN and BED primarily in specialty treatment settings (Wilson et al., 2007) even though a majority of patients with eating disorders are identified and treated in primary care settings (Hoek & van Hoeken, 2003; Striegel-Moore et al., 2008). Moreover, evidence suggests that lay individuals believe that eating disorders should be treated in a primary care setting (Mond & Hay, 2008; Mond, Hay, Rodgers, Owen, & Beumont, 2004b). By providing guidance from highly educated therapists (PhD candidates or therapists with graduate degrees) working in tertiary treatment centers with extensive local expertise in the treatment of eating disorders, the existing studies have not yet fully explored the possibility of expanding the availability of CBT-GSH by offering this treatment via less educated therapists. As a step toward effectiveness research, we evaluated CBT-GSH delivered in a primary care setting by master level counselors with no prior experience in the treatment of eating disorders.

Most patients presenting for treatment do not meet criteria for either BN or BED (Fairburn et al., 2007); to date, however, clinical trials have required presence of full syndrome eating disorders. One of the major reasons for not meeting full syndrome criteria is a lower binge frequency than the required minimum average of two episodes a week for three consecutive months for BN or two days a week for six consecutive months in the case of BED, yet emerging evidence suggests that individuals who engage in regular binge eating even if at a lesser frequency report significant clinical impairment or distress (Wilson & Sysko, in press). In the present study, patients were included if they met our research definition of “recurrent binge eating” which required a minimum average of one “objective bulimic episode” (OBE) a week during the preceding three months with no gaps of two or more weeks between binge eating episodes. This threshold is consistent with recent studies that have shown that even at the lower frequency level, binge eating is associated with elevated levels of psychological distress (Striegel-Moore et al., 2000) or indicators of impairment such as “days out of role” (Mond & Hay, 2007).

Lack of recognition of the eating behavior as symptomatic and lack of information about available or appropriate treatment options are yet further barriers to seeking treatment (Cachelin, Rebeck, Veisel, & Striegel-Moore, 2001; Mond & Hay, 2008; Mond, Hay, Rodgers, Owen, & Beumont, 2004a). As described in detail in a previous report (DeBar et al., 2009), the present study utilized a recruitment procedure more typically found in epidemiological studies than in treatment trials. Specifically, rather than relying solely on advertisements or public service announcements for finding participants, the present study invited members of a health maintenance organization to complete a brief eating disorder screener (and, if screen positive, a confirmatory interview) and enter the trial portion of the study if found to suffer from an eating disorder involving binge eating as the core behavioral symptom. Hence, outreach extended to individuals who might not themselves have identified their eating behavior as in need of treatment and who, therefore, might not have responded to a clinical trial study announcement seeking participants.

The principal aim of the present study was to conduct a blended efficacy-effectiveness trial testing the acceptability and efficacy of CBT-GSH for the treatment of eating disorders with recurrent binge eating as a core symptom in the context of a “real world” setting of a health maintenance organization (HMO) by comparing CBT-GSH to treatment as usual (TAU). A majority of individuals in the United States receive their health care in a managed care setting (Claxton et al., 2008). We selected TAU as a credible alternative to CBT-GSH because in the HMO members have access to a wide range of health promotion and treatment interventions related to weight and eating management as well as more general mental health concerns. Our design was also intended to examine the cost effectiveness of CBT-GSH and those results are the subject of a separate report (Lynch et al., 2009). We hypothesized that participants randomized to receive CBT-GSH would be more likely than those randomized to TAU to achieve abstinence from binge eating (primary outcome) and demonstrate significantly greater improvements in eating related psychopathology and psychosocial functioning (secondary outcomes).

Method

Participants and Recruitment

Participants were 123 health plan members (91.9% female, 96.7% white, and 3.3% Hispanic) with a mean age of 37.20 (SD = 7.78) and mean BMI of 31.27 (SD = 6.23). Most (82.1%) reported completing at least some college. A majority of participants (n = 72) met full-syndrome criteria for an eating disorder (bulimia nervosa (BN) n = 13; BED n = 59) and seven participants met the “lead symptom” criterion of binge eating on average at least twice a week with no gaps longer than two weeks but missed one of the remaining symptoms required for full syndrome diagnosis of BN (n = 1) or BED (n = 6). Eight participants reported binge eating on average at least twice a week but missed more than one criterion for a diagnosis of either BN or BED. Thirty-six participants reported recurrent binge eating at a minimum average frequency of once a week for the preceding three months.

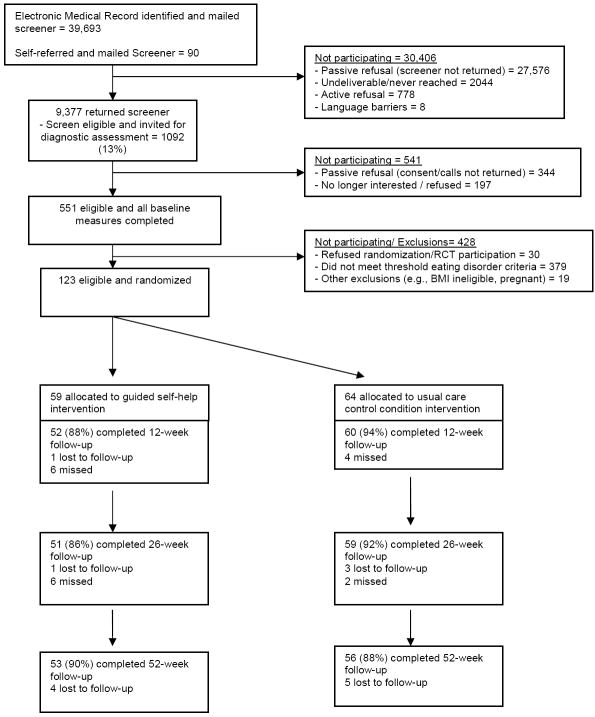

A detailed report of our recruitment approach has been published (Debar et al., 2009). The CONSORT diagram (Figure 1) shows the flow of participants from screening to randomization into the trial. In brief, recruitment initially involved mailings to a random sample of male and female health plan members between 18 and 35 for an epidemiological study on eating habits and body image (Striegel-Moore, Rosselli, et al., in press). To permit an unbiased examination of the psychometric properties of the screening instrument used for case finding, until we reached a predetermined number (100) of screen positive respondents, the study invitation did not mention the clinical trial and participants who met inclusion trial criteria (N = 29) were consented for the clinical trial upon completion of the baseline assessment. Later mailings specifically recruited for the clinical trial and targeted female health plan members up to age 50; also, posters and brochures advertising the study were distributed in HMO clinics to supplement these latter mailed recruitment efforts. These latter efforts yielded 95 additional patients. Except for gender (a greater proportion of the patients recruited via the epidemiological phase than via the recruitments advertising the trial were male) no differences were found on demographic characteristics or eating disorder diagnosis when comparing the two recruitment approaches.

Figure 1.

Participant flow across all phases of the study

All participants underwent a two-stage case finding procedure involving initial screening followed by a confirmatory diagnostic interview by study staff unaware of the screening status (Striegel-Moore, Perrin, et al., in press). Excluded from sampling were individuals with diagnostic codes indicative of severe cognitive impairment or psychosis, individuals currently being treated for cancer, women who were pregnant or had given birth in the past four months, and approximately 100 plan members whose records indicated an a priori opt-out from any study participation. Additional exclusion criteria (as determined during the diagnostic assessment) were a current diagnosis of anorexia nervosa and severe obesity (BMI > 45). The study was approved by all participating institutions’ human subjects review boards. The trial was registered online with the National Institutes of Health National Library of Medicine (http://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT00158340).

Intervention

Efron’s procedure (Efron, 1971) stratifying on purging status and gender was used to randomize participants into TAU or CBT-GSH. Participants were permitted to avail themselves of the full treatment resources offered through the HMO during the course of the study and all service use was recorded. Following randomization, all participants were mailed a flyer detailing relevant health plan sponsored services, such as a regularly offered series of classes focused on non-diet approaches to healthy living and eating. In addition, participants were encouraged to contact their primary care physician for other potentially appropriate services within the health plan including visits with a nutritionist or mental health provider. CBT-GSH additionally involved 8 sessions of CBT-GSH implemented over a 12 week period. The first session lasted 60 minutes; each subsequent session was 20 to 25 minutes in length. The first four sessions were weekly, the next four at two-week intervals. The treatment was based on Fairburn’s “Overcoming Binge Eating” (1995). The book’s first part provides user-friendly information about binge eating; the second part comprises a six step self-help program. The primary focus is on developing a regular pattern of moderate eating using self-monitoring, self-control strategies, and problem-solving. To promote maintenance of behavioral change, relapse prevention is emphasized. We added a module designed to reduce body-checking and body avoidance in order to explicitly address dysfunctional body shape and weight concerns (available on request from GTW). The main role of the therapist is to explain the rationale for CBT-GSH, develop realistic outcome expectancies, and engage the patient in adhering to the manual-based program.

Three master’s level therapists with experience in using CBT for depression, but no familiarity with eating disorders or CBT-GSH for treating binge eating, were trained and subsequently delivered the CBT-GSH treatment. The therapists had an average of 6 years of post-graduate clinical experience (range 4-10 years). Initial training was conducted by one of the senior investigators (GTW) in a three hour workshop. All therapists were required to complete treatment of two pilot patients and be approved before participating in the study proper. The therapists received weekly supervision on-site (LD) and participated in biweekly supervision conference calls as well as on-site supervision meetings three times a year with all three senior investigators (GWT, LD, RSM) who listened to audio recordings of randomly selected sessions.

Measures

All participants were assessed at baseline using all instruments described below and, using only measures of primary and secondary outcomes, at 12 weeks (post-treatment), 6- and 12 months. Treatment expectancies were measured at week 2. Participants could complete the screening questionnaire online and receive a $5.00 coffee-house gift card or return the completed questionnaire by pre-paid envelope without compensation. For all subsequent assessments, participants were compensated between $10 and $50 (depending on the length of assessment) for a total compensation of $225 plus a one-time bonus of $50 for participants completing all assessments.

For all study participants, use of HMO services during the 12 weeks post randomization was extracted from the electronic medical records and coded into four mutually exclusive categories: weight related services, eating related services, medications for mental health problems, and “all other services.” In addition, we coded for “all medications” and this category included medications for mental health problems.

Screening Questionnaire

The screening questionnaire collected information on demographic characteristics and current height and weight and measured eating disorder symptoms using a modified version of the Patient Health Questionnaire (Spitzer, Kroenke, & Williams, 1999) eating disorder module (PHQ-ED) which includes binary response items concerning binge eating and compensatory behaviors. Participants who reported binge eating at least once per week during the past three months (“screen-positive”) were invited to participate in further assessment to verify study eligibility. As previously reported, the PHQ-ED had high sensitivity and specificity (Striegel-Moore, Perrin, et al., in press). As evident from Figure 1, however, a large number of screened participants were found to be “false positive” cases, supporting the need to conduct the confirmatory diagnostic interviews described below.

Eating Pathology and Psychiatric Disorders

Screen-positive participants were interviewed by phone using the Eating Disorder Examination (EDE; Fairburn & Cooper, 1993), 12th edition with text edits from the 14th and 15th editions, to confirm presence of recurrent binge eating and eating disorder diagnoses based on the 4th edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). The EDE is a widely used semi-structured interview, generating operationally defined, DSM-IV based, diagnoses of eating disorders and dimensional information about eating behaviors and related attitudes. EDE items focus on the past 28 days and, for diagnostic items, also on the past 3 months (BN) or 6 months (BED). Symptoms are measured in terms of their frequency (e.g., number of binge eating episodes during the past 28 days) or severity (rated on a scale from 0 = absent to 6 = highest level of pathology, e.g., extreme overvaluation of weight or shape). The EDE defines binge eating episodes (also referred to as OBEs) as eating episodes that involve consuming, in two hours or less, more than what most people would eat under similar circumstances and experiencing loss of control during the episodes. The reliability and validity of the EDE have been established in several independent studies and these studies consistently have supported its use (Fairburn, Cooper & O’Connor, 2008).

To reduce participant burden, the EDE was edited such that only eating patterns and diagnostic items were assessed during the telephone interview and items comprising the EDE subscales (dietary restraint, eating concern, shape concern, and weight concern) were collected via a 22-item self-report questionnaire (EDE-Q; Fairburn & Beglin, 1994, 2008). Referring to the past 28 days, the EDE-Q items ask respondents to rate the number of days on which they experienced symptoms (e.g., “Have you tried to exclude from your diet any foods you like in order to influence your weight or shape, regardless of whether you have succeeded?”) or rate the severity of the symptoms (e.g., “How dissatisfied have you been with your weight?”). Ratings range from 0 (no days; or “not at all”) to 6 (everyday or “markedly,” respectively). Items are summed across the items comprising each scale and averages are calculated by dividing the scale total by the number of items. The EDE-Q has been shown to have excellent reliability and validity except when measuring overeating or binge eating (Fairburn & Beglin, 2008) which is why the latter was measured by EDE interview.

The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID-I/NP with psychotic screen; First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, 2002) was administered at baseline to measure axis I psychiatric disorders (current and life-time) and the Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD) module of the SCID-II (First, Gibbon, Spitzer, Williams, & Benjamin, 1997) was used to determine presence (life-time) of BPD.

All interviews (EDE and SCID) were conducted by telephone by assessors blind to participants initial screening responses and randomization assignment. Assessor training included the 11-hour SCID video series (www.scid4.org), 12 hours of training workshops with an expert SCID trainer, 20 hours of workshops with an expert EDE trainer, as well as interviews with pilot participants. For both the SCID and EDE, assessors continued practice interviewers until they achieved three consecutive interviews with 100% expert agreement. Ongoing biweekly supervision continued throughout the data collection period. Five percent of the EDE interviews were randomly selected to be coded by one of the two most experienced assessors to determine reliability. Inter-rater reliability was very high for EDE diagnoses (kappa = .961) as well as assessment of OBE days (ICC = .997) and number of OBEs (ICC = .999) during the past 28 days.

Psychosocial functioning

Self-report was used to assess depression, using the 21-item Beck Depression Inventory (BDI; Beck, Steer, & Garbin, 1988), and functional impairment, using the 5-item Work and Social Adjustment Scale (WSAS; Mundt, Marks, Shear, & Greist, 2002).

Data analyses

Comparisons between the TAU and intervention groups at baseline were conducted using chi-square and t-tests. Multilevel modeling with HLM6.0 was used to test for differences between the TAU and intervention groups across time for the primary and secondary outcomes. A quadratic model for time (baseline, 12, 26, 52 weeks) was used to capture nonlinear change across time. Therefore two parameters, linear slope and quadratic slope, characterize the change across time. The linear slope describes the initial rate of change and the quadratic slope reflects the degree to which the change slowed (or increased) over time. Both slope parameters are estimated simultaneously in the model. Multilevel modeling allows the inclusion of all participants regardless of missing data across time consistent with an intent-to-treat approach. Number needed to treat (NNT) effect sizes were computed for the primary outcome (Kraemer & Kupfer, 2006). In the context of this study, NNT answers the question: “How many more patients would need to be treated with CBT-GSH in order to avoid one more failure (i.e., patient continues to binge eat) that would have occurred had the patient been treated as usual”? For the secondary outcomes, Cohen’s d (Cohen, 1988) was computed using change from baseline to 52 weeks. Repeated measures analysis of variance was used for additional analyses to examine the relationship between abstinence over time and BMI. Using baseline measures, we conducted exploratory analyses to identify potential nonspecific predictor or moderator variables, including demographic characteristics, type or severity of eating disorder symptomatology, baseline BMI and “weight suppression” (i.e., the difference between current and highest adult BMI; Carter, McIntosh, Joyce, & Bulik, 2008; Lowe, 1993), comorbid psychiatric disorders (any comorbid disorder or total number, as well as Borderline Personality Disorder), self-reported depression, and treatment expectancies.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

We verified that the TAU and CBT-GSH groups did not differ at baseline, suggesting that randomization created initially equivalent groups. Specifically, as shown in Table 1, the groups did not differ at baseline on age, gender, BMI, education, race, ethnicity, depression, EDE diagnosis, presence of borderline personality disorder, Axis I disorder without eating disorder, or major depressive disorder.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Study Sample by Treatment

| TAU (N=64) | CBT-GSH (N=59) | Test statistic | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age (SD) in years | 36.64 (7.92) | 37.81 (7.64) | -.834a | .406 |

| Gender (female): % (n) | 92.2% (59) | 91.5% (54) | .018b | .893 |

| Education (some college or more): % (n) | 79.7% (51) | 84.7% (50) | .535b | .465 |

| Race (White): % (n) | 95.3% (61) | 98.3% (58) | .874b | .331 |

| Ethnicity (Hispanic): % (n) | 3.1% (2) | 3.4% (2) | .007b | .934 |

| Eating Disorder (ED) Diagnosis | .459b | .928 | ||

| Bulimia Nervosa purging: % (n) | 4.7% (3) | 5.1% (3) | ||

| Bulimia Nervosa nonpurging: % (n) | 6.3% (4) | 5.1% (3) | ||

| Binge Eating Disorder: % (n) | 45.3% (29) | 50.8% (30) | ||

| Recurrent Binge Eating: % (n) | 43.8% (28) | 39.0% (23) | ||

| Borderline Personality Disorder: % (n) | 4.7% (3) | 1.7% (1) | .915b | .633 |

| Axis I Disorder w/o ED: % (n) | 60.9% (39) | 59.3% (35) | .033b | .855 |

| Major Depressive Disorder: % (n) | 10.9% (7) | 15.3% (9) | .523b | .770 |

| EDE-Q Restraint: M (SD) | 2.74 (1.39) | 2.60 (1.44) | .568a | .571 |

| EDE-Q Eating Concern: M (SD) | 3.58 (1.19) | 3.51 (1.29) | .300a | .765 |

| EDE-Q Shape Concern: M (SD) | 4.67 (0.94) | 4.84 (0.94) | -1.025a | .308 |

| EDE-Q Weight Concern: M (SD) | 4.10 (1.81) | 4.20 (1.01) | -.508a | .612 |

| Beck Depression Inventory: M (SD) | 18.63 (8.32) | 19.63 (7.71) | -.679a | .499 |

| Work and Social Adjustment: M (SD) | 17.37 (7.24) | 17.28 (7.13) | .068a | .946 |

| Body Mass Index: M (SD) | 30.88 (6.71) | 31.68 (5.70) | -.710a | .479 |

Note. TAU = Treatment as Usual. CBT-GSH = Guided Self-Help Cognitive Behavioral Therapy. EDE-Q = Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire.

t-test.

chi-square test.

Table 2 illustrates that the proportion of participants utilizing health services during the 12 weeks following randomization did not differ significantly between the two groups in terms of use of services to treat an eating related problem, a weight related problem, use of prescription medications for mental health, use of any prescription medications, or all other health services (excluding the aforementioned categories). Weight-related services included participation in health education weight management and healthy eating group classes as well as individual visits with health plan nutritionists.

Table 2.

Health Services Use Among Participants in the 12 Weeks Following Randomization by Health Services Category and Treatment

| Health Services Category | TAU (N=64) | CBT-GSH (N=59) | Chi-square | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight related services | 4.7% | 1.7% | 0.874 | 0.350 |

| Eating disorder related services | 10.9% | 5.1% | 1.408 | 0.235 |

| Medications for mental health | 45.3% | 47.5% | 0.057 | 0.812 |

| All medications | 71.9% | 81.4% | 1.532 | 0.216 |

| All other health services | 64.1% | 64.4% | 0.002 | 0.968 |

Note. TAU = Treatment as Usual. CBT-GSH = Guided Self-Help Cognitive Behavioral Therapy.

Acceptability and Treatment Expectancies

The majority of the CBT-GSH group (71.2%) attended all 8 sessions, 74.6% attended at least 7 sessions and 81.4% attended at least 6 sessions. The mean number of sessions attended was 6.75 (SD = 2.39) and only 11.9% attended 2 or fewer sessions. There were minimal missing data with 83.7% of the total sample having data on the primary outcome at all 4 time points (84.4% TAU, 83.1% CBT-GSH), 90.2% with 3 or more time points, and 95.1% with 2 or more time points. At 52 weeks, 56 of the 64 TAU and 53 of the 59 CBT-GSH patients had data on the primary outcome.

When asked at session 2 how suitable participants thought their options were for treating binge eating on a scale from 1 (not at all suitable) to 5 (extremely suitable), the CBT-GSH group found their options to be significantly more suitable (M = 4.16, SD = 0.65) than the TAU group (M = 2.71, SD = 1.22), t(82) = 7.09, p < .001, d = 1.25. The CBT-GSH group was also more confident (1 = not at all confident, 5 = extremely confident) that their treatment options would be successful (M = 3.78, SD = 0.82) than the TAU group (M = 2.65, SD = 0.98), t(82) = 5.75, p <.001, d = 1.09. In subgroup analyses for the TAU and CBT-GSH groups, neither question was predictive of abstinence at 52 weeks (TAU suitable χ2 =0.15, p = .700; TAU confident χ2 = 2.39, p = .122; CBT-GSH suitable χ2 = 1.68, p = .195; CBT-GSH confident χ2 =1.14, p = .286).

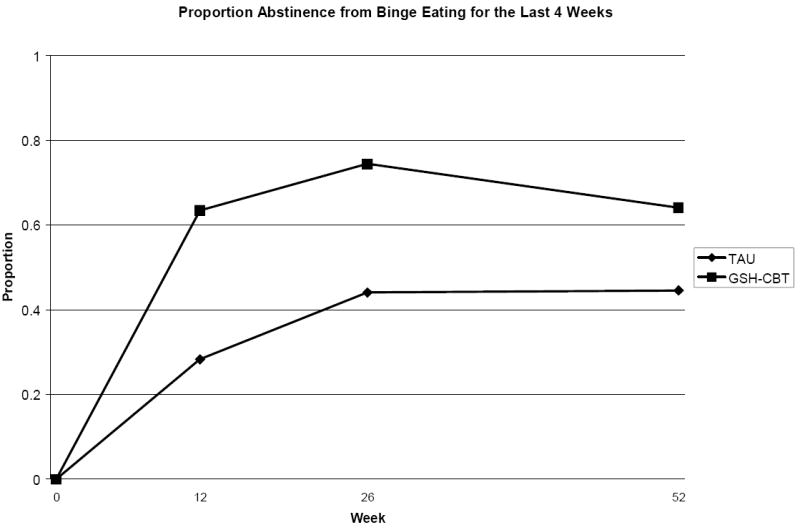

Proportion Abstaining from Binge Eating

The CBT-GSH and TAU groups were significantly different on the pattern of change in the primary outcome of abstinence from binge eating over time. The improvement in abstinence was greater for CBT-GSH than TAU, with a greater rate of change from baseline (B = .122, p < .001) for the CBT-GSH group which also slowed more over time (B= -.002, p < .001) in comparison to the TAU group (see Figure 2). At 12 weeks, 28.3% of TAU and 63.5% of CBT-GSH participants were abstinent from binge eating (χ2 = 13.91, p < .001, NNT = 3), 44.1% and 74.5% were abstinent from binge eating in the TAU and intervention groups at 26 weeks (χ2 = 10.42, p < .001, NNT = 3), and at 52 weeks, 44.6% of the TAU group and 64.2% of the CBT-GSH group were abstinent from binge eating (χ2 =4.17, p < .041, NNT = 5). These group differences reflected large effects: at six months, for every three patients treated with CBT-GSH, one more treatment failure (i.e., the patient would have continued to binge eat) was avoided (Kraemer & Kupfer, 2006).

Figure 2.

Abstinence rates at post-treatment, 6-month, and 12-month follow-up

Note: TAU and GSH-CBT are significantly different at each follow-up time point (Weeks 12 & 26 p<.001: Week 52 p=.041)

Secondary Outcomes

As shown in Table 3, the two groups differed significantly in the pattern of restraint (B = -.055, p < .004, d = .30), eating concern (B = -.068, p < .001, d =. 54), shape concern (B = -.045, p < .038, d = 1.01), and weight concern (B = -.048, p=.017, d = .49): the CBT-GSH group showed more improvement than TAU over time for each of these subscales. The CBT-GSH group reported less eating restraint, and fewer eating-, shape-, and weight concerns at the follow-ups than the TAU group. The CBT-GSH group also showed greater improvement in depression as measured by the BDI (B = -.330, p < .007, d = .56) and work and social adjustment as measured by the WSAS (B = .142, p < .038, d = .58). There were no significant differences in the acceleration or deceleration of the changes over time between the two groups for any of the secondary outcomes. The two groups did not differ significantly on the change in BMI over time.

Table 3.

Secondary Outcomes by Treatment and Assessment Time

| Baseline M (SD) | Week 12 M (SD) | Week 26 M (SD) | Week 52 M (SD) | p-value | Effect Size | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EDE-Q Restraint | ||||||

| TAU | 2.74 (1.39) | 2.08 (1.51) | 2.07 (1.44) | 1.92 (1.39) | .004 | .30 |

| CBT-GSH | 2.60 (1.44) | 1.48 (1.38) | 1.27 (1.16) | 1.35 (1.24) | ||

| EDE-Q Eating Concerns | ||||||

| TAU | 3.58 (1.19) | 2.31 (1.51) | 2.21 (1.57) | 2.10 (1.37) | <.001 | .54 |

| CBT-GSH | 3.51 (1.29) | 1.43 (1.43) | 1.24 (1.35) | 1.36 (1.44) | ||

| EDE-Q Shape Concerns | ||||||

| TAU | 4.67 (0.94) | 3.86 (1.36) | 3.79 (1.53) | 3.91 (1.42) | .038 | 1.01 |

| CBT-GSH | 4.84 (0.94) | 3.23 (1.63) | 3.09 (1.66) | 3.13 (1.64) | ||

| EDE-Q Weight Concerns | ||||||

| TAU | 4.10 (1.81) | 3.36 (1.31) | 3.26 (1.52) | 3.23 (1.49) | .017 | .49 |

| CBT-GSH | 4.20 (1.01) | 2.70 (1.43) | 2.60 (1.45) | 2.64 (1.52) | ||

| Beck Depression Inventory | ||||||

| TAU | 18.63 (8.32) | 14.63 (9.23) | 13.77 (9.64) | 13.94 (9.16) | ||

| CBT-GSH | 19.74 (7.68) | 10.54 (8.37) | 9.23 (7.78) | 10.76 (8.42) | ||

| Work and Social Adjustment | ||||||

| TAU | 17.37 (7.24) | 14.53 (7.13) | 12.17 (7.04) | 13.15 (7.71) | .038 | .58 |

| CBT-GSH | 17.28 (7.13) | 9.57 (5.79) | 9.79 (6.38) | 8.86 (5.27) | ||

| Body Mass Index | ||||||

| TAU | 30.88 (6.71) | 30.91 (6.87) | 30.85 (7.16) | 31.50 (7.33) | .770 | .16 |

| CBT-GSH | 31.74 (5.67) | 31.10 (5.79) | 31.04 (5.73) | 31.38 (5.50) | ||

Note: CBT-GSH = Guided Self-Help Cognitive Behavioral Therapy; EDE-Q = Eating Disorder Examination-Questionnaire; p-value is for differences between the groups in change over time; effect sizes are Cohen’s d

Because of the apparent absence of a relationship between improvements in BMI in the CBT-GSH group compared to TAU, we conducted an unplanned exploratory analysis examining the effect of abstinence from binge eating on BMI using data from both groups. Participants were classified as being abstinent at 26 weeks and 52 weeks or not. A group (those who were abstinent at weeks 26 and 52 versus those who were not abstinent at weeks 26 and 52) by time (baseline and 52 weeks) repeated measures analysis of variance was conducted with BMI as the dependent variable. Forty-one individuals were abstinent at both 26 and 52 weeks; fifty-eight individuals were not abstinent at both 26 and 52 weeks or were missing data on abstinence at one of those time points. The time by group interaction was significant, F(1,97)= 4.44, p < .038, d = .12 with those who were not abstinent at 26 and 52 weeks showing an increase in BMI (M = 31.16, SD = 6.77 at baseline; M = 31.82, SD = 7.10 at 52 weeks) and those abstinent at both time points showing a decline in BMI (M = 31.01, SD = 5.22 at baseline; M = 30.91, SD = 5.57 at 52 weeks).

Nonspecific predictors and moderators

Exploratory analyses testing for nonspecific predictors or moderators of treatment outcome were non-significant for age, education, income, number of binge eating episodes at baseline, eating disorder diagnosis (recurrent binge eating, BN, BED), severity of depressed mood (BDI scores), any or total number of comorbid psychiatric disorders, Borderline Personality Disorder, baseline BMI or obesity (BMI equal to or greater than 30), and weight suppression (data available upon request).

Discussion

This study examined the acceptability and efficacy of a brief guided self-help program, based on cognitive-behavioral principles, for the treatment of recurrent binge eating relative to treatment as usual. Our study employed a randomized clinical trial design yet involved features more commonly found in effectiveness studies, including delivering the treatment in a primary care context and by staff with less education than is typical in efficacy studies, and adopting a broader definition of eating disorders (i.e., allowing for greater variability in diagnoses and thereby more closely capturing eating disorder cases that might present in routine clinical practice). As summarized in Table 1, 48% of the sample was diagnosed with BED, 10.6% met criteria for BN, and 41.6% of the sample met our criteria for recurrent binge eating. Exploratory moderator analyses failed to show differential treatment effects across eating disorder diagnoses, yet we caution that the percentage of individuals with BN was too small to detect differences. Previous research has shown CBT-GSH to be effective both with BED (Wilson et al., in press) and with BN (Mitchell et al., 2006), yet the latter study awaits replication. Hence, until further studies are conducted where power is adequate to test efficacy of CBT-GSH for the treatment of BN, we conservatively conclude that CBT-GSH is a viable treatment for recurrent binge eating in individuals who do not meet criteria for BN or anorexia nervosa.

Although the particular outreach approach to health plan members proved highly challenging, requiring large scale mailings (Debar et al., 2009), once participants agreed to enter the trial, acceptability of the CBT-GSH program as reflected in attendance rates was high. Dropout was low and consistent with completion rates reported in other trials providing guided self-help for the treatment of binge eating disorder which found dropout rates of 10% (Carter & Fairburn, 1998) or 13% (Grilo & Masheb, 2005), respectively. Moreover, participants appeared to agree with the rationale for CBT-GSH which was presented during the first session: the mean expectancy rating for the suitability of this treatment for their eating problem (obtained at session 2) was 4.16 on a scale where 5 was the maximum score. Of note, suitability ratings were not predictive of treatment outcome. Our design does not permit testing the hypothesis that suitability ratings would be predictive of relatively greater adherence to CBT-GSH versus another treatment because our comparison condition, TAU, did not require patients to follow a specific regimen.

Treatment in this study was delivered by Master’s level therapists with experience in using CBT for depression. A majority of patients in our study exhibited comorbid psychopathology (see Table 1). Roughly 60% had a comorbid axis I diagnosis; 15% of the CBT-GSH group were diagnosed with major depression. Rates of comorbid Borderline Personality Disorder were low. The level of therapist training and skill necessary for effective administration of CBT-GSH remains undetermined (Sysko & Walsh, 2008). Inexperienced and unsupervised health care providers with minimal training in CBT-GSH appear ineffective (Walsh, Fairburn, Mickley, Sysko, & Parides, 2004). Even if successful CBT-GSH requires specific therapist selection, training, and supervision, it would still provide a briefer, less costly, and more readily disseminable intervention to a wider range of health care providers than specialty psychotherapy (Wilson et al., in press).

The primary aim of our study was to evaluate CBT-GSH against TAU. All participants were informed about the HMO’s options for treating binge eating. Our data show that most participants in both conditions utilized health services during the 12 weeks following randomization and thus had opportunity to request specific services for their eating problem. The large number of participants receiving psychotropic medications (typically antidepressants and, to a lesser degree anxiolitics) speaks to the considerable level of distress or comorbid psychopathology in this sample. Yet, as shown in Table 2, only few participants were treated specifically for an eating disorder outside the context of the CBT-GSH treatment condition. Similar to services offered in most health care settings, treatment for eating disorders within the health plan largely consisted of nonspecific case management rather than the provision of evidence based CBT treatment for eating disorders. Indeed, several previous studies have documented the infrequent use of care targeted specifically to treating the eating disorder (Striegel-Moore et al., 2008; Striegel-Moore et al., 2000).

The post-treatment and one year follow-up abstinence rates from binge eating (our primary outcome variable) for CBT-GSH of 63% and 64% respectively are consistent with findings from recent research on the efficacy of CBT-GSH for the treatment of BED. For example, Wilson et al. (in press) obtained rates of 58% and 60% at post-treatment and one year follow-up. Moreover, favorable results were also observed for several of the secondary outcomes, including improvements on measures of eating related psychopathology (specifically, eating-, weight- and shape concerns, and restraint), as well as on measures of depression and functional impairment.

The effect size estimates for abstinence from binge eating further underscore the clinical significance of our results. For every three patients (at 6 months) or 5 patients (at 12 months) treated with CBT-GSH, one more failure (i.e., a patient who did not achieve abstinence) was observed in TAU. Even though CBT-GSH lost some of its superiority over TAU over time (NNT decreased from 3 at post-treatment and 6-month follow-up to 5 at 12-months), this relative decline in superiority is modest. Moreover, we note that the relative decline in superiority appeared to occur because of improvements in the TAU group rather than because of a loss of earlier gains in the CBT-GSH group. The cost effectiveness of CBT-GSH relative to TAU is the subject of a separate report (Lynch et al., 2009). The results also compare favorably with outcomes for BED of specialty psychological therapies such as manual-based CBT and IPT (Wilson et al., 2007). As such, they add to the accumulating evidence that recurrent binge eating can be effectively treated with a brief and easily disseminable treatment.

Similar to studies of CBT or CBT-GSH for the treatment of BED (Grilo & Masheb, 2005; Wilson et al., in press), a population where overweight or obesity is common and weight loss therefore a desirable treatment outcome (Wilfley, Bishop, Wilson, & Agras, 2007), our study found that CBT-GSH had no significant effect on weight. In part this may reflect the fact that the intervention does not target weight loss (although we point out that participants in the Grilo and Masheb (2005) study also did not lose significant amounts of weight in the BWL condition). An unplanned post-hoc analysis found a small effect for BMI when comparing participants who had achieved abstinence from binge eating versus those who had not. Of note, the latter group experienced a slight weight gain over the course of the study. This finding is consistent with data from a longitudinal study of women with bulimia nervosa or binge eating who were found to gain weight at an accelerated rate compared to healthy women (Fairburn et al., 2003).

Several limitations need to be considered. These include the insufficient power for testing predictors or moderators of treatment outcome. Surprisingly, we did not find a significant predictor effect of negative affect (defined by BDI scores) given previous studies in which high negative affect predicted a poorer treatment response (Masheb & Grilo, 2008; Stice, Bohon, Marti, & Fischer, 2008). Another limitation was the demographic homogeneity of our sample. Men or individuals representing ethnic minority populations have been shown to suffer from binge eating disorders (Alegria, et al., 2007; Cachelin & Striegel-Moore, 2006; Hudson, Hiripi, Pope, & Kessler, 2007; Taylor, Caldwell, Baser, Faison, & Jackson, 2007), yet few men or Hispanic individuals were included in our sample despite outreach efforts and the availability of assessment and intervention materials in Spanish language for Hispanic health plan members (the largest ethnic minority group in the HMO’s geographic area).

The strengths of the study include the health maintenance organization setting, the use of the EDE, good retention of patients in the sample through follow-up, and a broader sample of patients (including many with EDNOS) than more narrowly defined BED or BN samples from previous studies of CBT-GSH. As such, we have provided novel findings for the disseminability of evidence based CBT-GSH.

Acknowledgments

Supported by MH066966 (to principal investigator R.S.M.) from the National Institutes of Health and by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) and the National Institute of Diabetes, Digestive, and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) (awarded to Kaiser Foundation Research Institute). The contents of this study are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official of the NIH, NIMH, NIDDK, or the Kaiser Foundation Research Institute. Trial registry name: Guided Self-Help Treatment for Binge Eating Disorders (BEST)

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: The following manuscript is the final accepted manuscript. It has not been subjected to the final copyediting, fact-checking, and proofreading required for formal publication. It is not the definitive, publisher-authenticated version. The American Psychological Association and its Council of Editors disclaim any responsibility or liabilities for errors or omissions of this manuscript version, any version derived from this manuscript by NIH, or other third parties. The published version is available at www.apa.org/pubs/journals/ccp

Contributor Information

Ruth H. Striegel-Moore, Wesleyan University

G. Terence Wilson, Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey.

Lynn DeBar, Center for Health Research, Kaiser Permanente NorthWest.

Nancy Perrin, Center for Health Research, Kaiser Permanente NorthWest.

Frances Lynch, Center for Health Research, Kaiser Permanente NorthWest.

Francine Rosselli, Wesleyan University.

Helena C. Kraemer, Stanford University

References

- Alegria M, Woo M, Cao Z, Torres M, Meng X, Striegel-Moore R. Prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in Latinos in the United States. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2007;40(Supl):S15–S21. doi: 10.1002/eat.20406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4. Washington DC: Author; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Banasiak SJ, Paxton SJ, Hay PJ. Perceptions of cognitive behavioural guided self-help treatment for bulimia nervosa in primary care. Eating Disorders. 2007;15(1):23–40. doi: 10.1080/10640260601044444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Garbin MG. Psychometric properties of the Beck depression Inventory: Twenty-five years of evaluation. Clinical Psychology Review. 1988;8(1):77–100. [Google Scholar]

- Brownley KA, Berkman ND, Sedway JA, Lohr KN, Bulik CM. Binge eating disorder treatment: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2007;40(4):337–348. doi: 10.1002/eat.20370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cachelin FM, Rebeck R, Veisel C, Striegel-Moore RH. Barriers to treatment for eating disorders among ethnically diverse women. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2001;30(3):269–278. doi: 10.1002/eat.1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cachelin FM, Striegel-Moore RH. Help seeking and barriers to treatment in a community sample of Mexican American and European American women with eating disorders. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2006;39(2):154–161. doi: 10.1002/eat.20213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter FA, McIntosh VV, Joyce PR, Bulik CM. Weight suppression predicts weight gain over treatment but not treatment completion or outcome in bulimia nervosa. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2008;117(4):936–940. doi: 10.1037/a0013942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter JC, Fairburn CG. Cognitive-behavioral self-help for binge eating disorder: A controlled effectiveness study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1998;66(4):616–623. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.4.616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claxton G, Gabel JR, Dijulio B, Pickreign J, Whitmore H, Finder B, et al. Health benefits in 2008: Premiums moderately higher, while enrollment in consumer-directed plans rises in small firms. Health Affairs (Project Hope) 2008;27(6):w492–502. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.6.w492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Currin L, Waller G, Treasure J, Nodder J, Stone C, Yeomans M, et al. The use of guidelines for dissemination of “best practice” in primary care of patients with eating disorders. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2007;40(5):476–479. doi: 10.1002/eat.20385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debar LL, Yarborough BJ, Striegel-Moore RH, Rosselli F, Perrin N, Wilson GT, et al. Recruitment for a guided self-help binge eating trial: Potential lessons for implementing programs in everyday practice settings. Contemporary Clinical Trials. 2009;30(4):326–333. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2009.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efron B. Forcing a sequential experiment to be balanced. Biometrika. 1971;58:403–417. [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn CG. Overcoming binge eating. New York: Guilford Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn CG. Cognitive behavior therapy and eating disorders. New York: Guilford Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn CG, Beglin SJ. Assessment of eating disorders: Interview or self-report questionnaire? International Journal of Eating Disorders. 1994;16(4):363–370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn CG, Beglin SJ. Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire. In: Fairburn CG, editor. Cognitive behavior therapy and eating disorders. New York: Guilford Press; 2008. pp. 308–314. [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn CG, Cooper Z. The eating disorder examination. In: Fairburn CG, Wilson GT, editors. Binge eating nature, assessment, and eating. 12. New York: Guilford Press; 1993. pp. 317–360. [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn CG, Cooper Z, Bohn K, O’Connor ME, Doll HA, Palmer RL. The severity and status of eating disorder NOS: Implications for DSM-V. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2007;45(8):1705–1715. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2007.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn CG, Stice E, Cooper Z, Doll HA, Norman PA, O’Connor ME. Understanding persistence in bulimia nervosa: A 5-year naturalistic study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71(1):103–109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I disorders, research version, non-patient edition, with psychotic screen, (SCID-I/NP, w/psy screen) New York: Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Gibbon M, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Benjamin LS. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II personality disorders, (SCID-II) Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, Inc; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Grilo CM, Hrabosky JI, White MA, Allison KC, Stunkard AJ, Masheb RM. Overvaluation of shape and weight in binge eating disorder and overweight controls: Refinement of a diagnostic construct. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2008;117(2):414–419. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.117.2.414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grilo CM, Masheb RM. A randomized controlled comparison of guided self-help cognitive behavioral therapy and behavioral weight loss for binge eating disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2005;43(11):1509–1525. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2004.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoek HW, van Hoeken D. Review of the prevalence and incidence of eating disorders. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2003;34(4):383–396. doi: 10.1002/eat.10222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson JI, Hiripi E, Pope HG, Jr, Kessler RC. The prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey replication. Biological Psychiatry. 2007;61(3):348–358. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.03.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer HC, Kupfer DJ. Size of treatment effects and their importance to clinical research and practice. Biological Psychiatry. 2006;59(11):990–996. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer HC, Wilson GT, Fairburn CG, Agras WS. Mediators and moderators of treatment effects in randomized clinical trials. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2002;59(10):877–883. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.10.877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewinsohn PM, Striegel-Moore RH, Seeley JR. Epidemiology and natural course of eating disorders in young women from adolescence to young adulthood. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2000;39(10):1284–1292. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200010000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe MR. The effects of dieting on eating behavior: A three-factor model. Psychological Bulletin. 1993;114(1):100–121. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.114.1.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch FL, Striegel-Moore RH, Dickerson JF, Perrin N, DeBar L, Wilson GT, et al. Cost-effectiveness of a guided self-help intervention for recurrent binge eating. 2009 doi: 10.1037/a0018982. Manuscript submitted for publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masheb RM, Grilo CM. Prognostic significance of two sub-categorization methods for the treatment of binge eating disorder: Negative affect and overvaluation predict, but do not moderate, specific outcomes. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2008;46(4):428–437. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2008.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mond JM, Hay PJ. Functional impairment associated with bulimic behaviors in a community sample of men and women. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2007;40(5):391–398. doi: 10.1002/eat.20380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mond JM, Hay PJ. Public perceptions of binge eating and its treatment. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2008;41(5):419–426. doi: 10.1002/eat.20512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mond JM, Hay PJ, Rodgers B, Owen C. Health service utilization for eating disorders: Findings from a community-based study. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2007;40(5):399–408. doi: 10.1002/eat.20382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mond JM, Hay PJ, Rodgers B, Owen C. Comparing the health burden of eating-disordered behavior and overweight in women. International Journal of Eating Disorders. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2008.1174. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mond JM, Hay PJ, Rodgers B, Owen C, Beumont PJV. Beliefs of the public concerning the helpfulness of interventions for bulimia nervosa. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2004a;36(1):62–68. doi: 10.1002/eat.20004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mond JM, Hay PJ, Rodgers B, Owen C, Beumont PJV. Beliefs of women concerning the severity and prevalence of bulimia nervosa. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2004b;39(4):299–304. doi: 10.1007/s00127-004-0726-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mundt JC, Marks IM, Shear M, Greist JM. The Work and Social Adjustment Scale: A simple measure of impairment in functioning. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;180(5):461–464. doi: 10.1192/bjp.180.5.461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mussell MP, Crosby R, Crow SJ, Knopke AJ, Peterson CB, Wonderlich S, et al. Utilization of empirically supported psychotherapy treatment for individuals with eating disorders. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2000;27:230–237. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(200003)27:2<230::aid-eat11>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins SJ, Murphy R, Schmidt U, Williams C. Self-help and guided self-help for eating disorders. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (Online) 2006;3:CD004191. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004191.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro JR, Berkman ND, Brownley KA, Sedway JA, Lohr KN, Bulik CM. Bulimia nervosa treatment: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2007;40(4):321–336. doi: 10.1002/eat.20372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: The PHQ Primary Care Study. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1999;282(18):1737–1744. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.18.1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E, Bohon C, Marti CN, Fischer K. Subtyping women with bulimia nervosa along dietary and negative affect dimensions: Further evidence of reliability and validity. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2008;76(6):1022–1033. doi: 10.1037/a0013887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Striegel-Moore RH, DeBar L, Wilson G, Dickerson J, Rosselli F, Perrin N, et al. Health services use in eating disorders. Psychological Medicine. 2008;38(10):1465–1474. doi: 10.1017/S0033291707001833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Striegel-Moore RH, Leslie D, Petrill SA, Garvin V, Rosenheck RA. One-year use and cost of inpatient and outpatient services among female and male patients with an eating disorder: Evidence from a national database of health insurance claims. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2000;27(4):381–389. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(200005)27:4<381::aid-eat2>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Striegel-Moore RH, Perrin N, DeBar L, Wilson GT, Rosselli F, Kraemer HC. Screening for binge eating disorders using the Patient Health Questionnaire in a community sample. International Journal of Eating Disorders. doi: 10.1002/eat.20694. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Striegel-Moore RH, Rosselli F, Perrin N, Debar L, Wilson GT, May A, et al. Gender difference in the prevalence of eating disorder symptoms. International Journal of Eating Disorders. doi: 10.1002/eat.20625. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Striegel-Moore RH, Seeley JR, Lewinsohn PM. Psychosocial adjustment in young adulthood of women who experienced an eating disorder during adolescence. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2003;42(5):587–593. doi: 10.1097/01.CHI.0000046838.90931.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sysko R, Walsh B. A critical evaluation of the efficacy of self-help interventions for the treatment of bulimia nervosa and binge-eating disorder. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2008;41(2):97–112. doi: 10.1002/eat.20475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor JY, Caldwell CH, Baser RE, Faison N, Jackson JS. Prevalence of eating disorders among Blacks in the National Survey of American Life. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2007;40(Suppl):S10–14. doi: 10.1002/eat.20451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh B, Fairburn CG, Mickley D, Sysko R, Parides MK. Treatment of bulimia nervosa in a primary care setting. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;161(3):556–561. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.3.556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang PS, Lane M, Olfson M, Pincus HA, Wells KB, Kessler RC. Twelvemonth use of mental health services in the United States: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):629–640. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilfley DE, Bishop ME, Wilson G, Agras W. Classification of eating disorders: Toward DSM-V. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2007;40(Supl):S123–S129. doi: 10.1002/eat.20436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson GT, Grilo CM, Vitousek KM. Psychological treatment of eating disorders. American Psychologist. 2007;62(3):199–216. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.62.3.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson GT, Shafran R. Eating disorders guidelines from NICE. Lancet. 2005;365:79–81. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17669-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson GT, Sysko R. Frequency of binge eating episodes in bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder: Diagnostic considerations. International Journal of Eating Disorders. doi: 10.1002/eat.20726. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson GT, Vitousek KM, Loeb KL. Stepped care treatment for eating disorders. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68(4):564–572. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson GT, Wilfley DE, Agras W, Bryson SW. Psychological treatments of binge eating disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.170. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]