Abstract

In our continued attempts to identify novel and effective pan-Bcl-2 antagonists, we have recently reported a series of compound 2 (Apogossypol) derivatives, resulting in the chiral compound 4 (8r). We report here on synthesis and evaluation on its optically pure individual isomers. Compound 11 (BI-97C1), the most potent diastereoisomer of compound 4, inhibits the binding of BH3 peptides to Bcl-XL, Bcl-2, Mcl-1 and Bfl-1 with IC50 values of 0.31, 0.32, 0.20 and 0.62 μM, respectively. The compound also potently inhibits cell growth of human prostate cancer, lung cancer and lymphoma cell lines with EC50 values of 0.13, 0.56 and 0.049 μM, respectively and shows little cytotoxicity against bax−/−bak−/− cells. Compound 11 displays in vivo efficacy in transgenic mice models and also demonstrated superior single-agent antitumor efficacy in a prostate cancer mouse xenograft model. Therefore, compound 11 represents a potential drug lead for the development of novel apoptosis-based therapies against cancer.

Introduction

Programmed cell-death (apoptosis) plays critical roles in the maintenance of normal tissue homeostasis, ensuring a proper balance of cell production and cell loss.1, 2 Defects in the regulation of programmed cell death promote tumorgenesis, and also contribute significantly to chemoresistance.3, 4 B-cell lymphoma/leukemia-2 (Bcl-2) family proteins are central regulators of this process.5–7 To date, six anti-apoptotic members of the Bcl-2 family have been identified and characterized, including Bcl-2, Bcl-XL, Mcl-1, Bfl-1, Bcl-W and Bcl-B. Given that over-expression of anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins occurs in many human cancers and leukemias, these proteins are very attractive targets for the development of novel anticancer agents.8–10 Members of the Bcl-2 family proteins also include pro-apoptotic effectors such as Bak, Bax, Bad, Bim and Bid that are antagonized by anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins via heterodimerization3 involving a hydrophobic crevice on the surface of anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins and the alpha-helix BH3 dimerization domain of pro-apoptotic members.5 Thus, molecules that mimic the BH3 domain of pro-apoptotic proteins may be effective in either inducing apoptosis and/or in abrogating the ability of anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 proteins to inhibit cancer cell death.

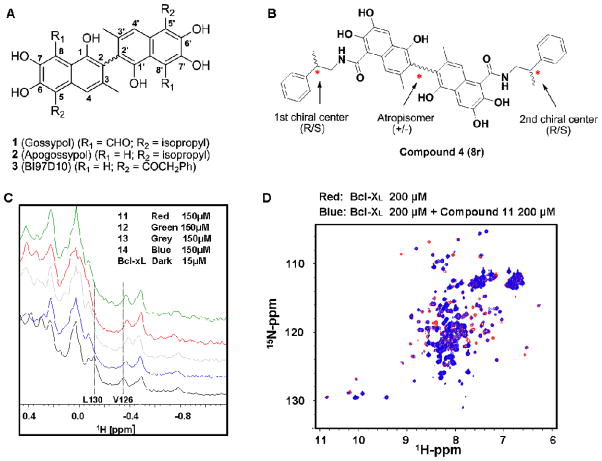

We and others have reported that the natural product 1 (Gossypol) (Figure 1A) is a potent inhibitor of Bcl-2, Bcl-XL and Mcl-1, functioning as a BH3 mimic11–15. The (−) atropisomer of compound 1 is currently in phase II clinical trials (AT101), displaying single-agent antitumor activity in patients with advanced malignancies.13–15 Given that compound 1 may have off-target effects likely due to two reactive aldehyde groups, we designed compound 2 (Apogossypol) (Figure 1A), a molecule that lacks these aldehydes, but retains activity against anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins in vitro.16 Recently, we further compared the efficacy and toxicity in mice of compounds 1 and 2. Our preclinical in vivo data show that compound 2 has superior efficacy and markedly decreased toxicity compared to 1.17 We also evaluated the single-dose pharmacokinetic characteristics of compound 2 in mice. Compound 2 displayed superior blood concentrations over time compared to compound 1, due to slower clearance.18 These observations indicate that compound 2 is a promising lead compound for further development of cancer therapies.

Figure 1.

(A) Structure of compounds 1, 2 and 3. (B) Structure of compound 4 (8r). (C) NMR binding studies. Aliphatic region of the 1H-NMR spectrum of Bcl-XL (15 μM, black) and Bcl-XL in the presence of compound 11 (150 μM, red), 12 (150 μM, green), 13 (150 μM, grey) and 14 (150 μM, blue). (D) Superposition of 2D [15N,1H]-TROSY spectra of free Bcl-XL (200 μM; red) and after addition of compound 11 (200 μM; blue).

Recently, we reported the separation and characterization of atropisomers of compound 2.19 These studies revealed that the racemic compound 2 is as effective as its individual isomers in vitro.19 We further reported the synthesis and evaluation of 5,5′ amide and ketone substituted compound 2 derivatives.20, 21 Among these derivatives, compound 3 (BI-79D10) and 4 (8r)20, 21 displayed improved in vitro and in vivo efficacy compared to compound 2 (Figure 1A and 1B). However, compound 4 has three centers of chirality and is a mixture of diastereisomers (Figure 1B). Chirality has a significant effect on the behavior of compounds in vitro and in vivo partially because different enantiomers and diastereoisomers have different physical, chemical and pharmacology properties. In principle, different enantiomers or diastereoisomers should be treated as different compounds. Indeed, the (−) atropisomer of compound 1 displayed a markedly differential activity compared to its natural racemic mixture. On the basis of these premises, in this current work, we focus our attention on preparing four optically pure isomers (11–14) of compound 4 (Scheme 1) followed by further investigation of their in vitro and in vivo activities.

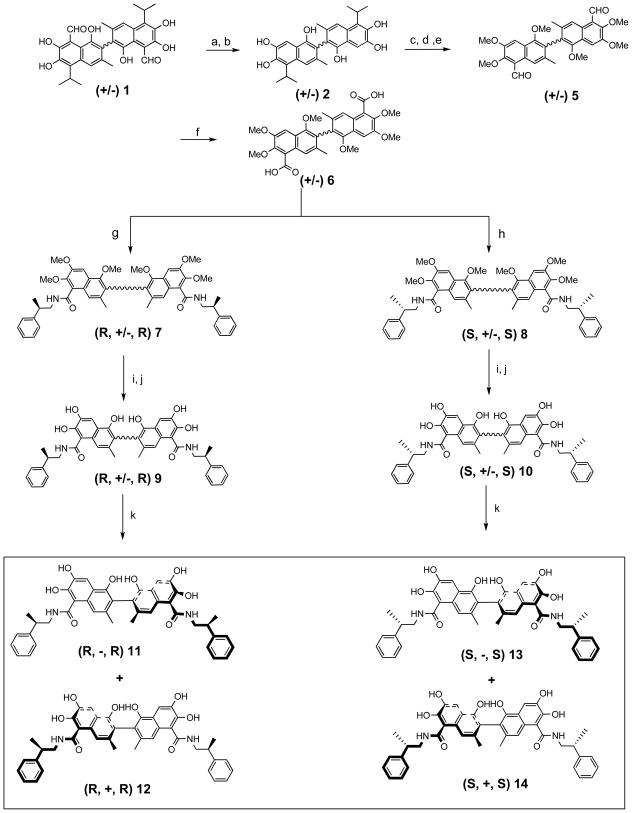

Scheme 1.

Reagents and conditions: (a) NaOH, H2O, reflux; (b) H2SO4; (c) DMS, K2CO3; (d) TiCl4, Cl2CHOCH3, rt; (e) HCl, H2O (f) NaClO2, H2O2, KH2PO4, CH3CN, rt; (g) (R)-(+)-β-Methylphenethylamine, EDCI, NH2R, HOBT, rt (h) (S)-(−)-β-Methylphenethylamine, EDCI, NH2R, HOBT, rt (i) BBr3, CH2Cl2 (j) HCl, H2O (k) Chiral column chromatography separation.

Results and Discussion

We had recently reported that compound 4 was a promising inhibitor of Bcl-XL and Bcl-2 with improved in vitro and in vivo efficacy compared to compound 2.20 However, compound 4 was not optically pure having two centers of chirality generated from 2-phenyl propyl groups (Figure 1B). In addition, compound 4 displayed axial chirality due to restricted rotation around the binaphthyl bond (Figure 1B). Therefore, it was attractive to explore whether optically pure isomers of compound 4 presented different in vitro and in vivo activities. A synthetic route (Scheme 1) was developed to prepare optically pure isomers. Synthesis of atropisomers (+/−) 2, (+/−) 5 and (+/−) 6 had been previously reported.20 The racemic carboxylic acid (+/−) 6 was then coupled with optically pure chiral amines, (R)-β-methylphenethylamine and (S)-β-methylphenethylamine, respectively, in the presence of 1-ethyl-3-(3′-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide (EDCI) at room temperature to give atropoisomers (R, +/−, R) 7 and (S, +/−, S) 8, respectively.22 Subsequent demethylation of the compound (R, +/−, R) 7 and (S, +/−, S) 8 using boron tribromide afforded atropisomers (R, +/−, R) 9 and (S, +/−, S) 10, respectively.23 The atropisomers (R, +/−, R) 9 were readily resolved using a liquid chiral column chromatography to afford two optically pure isomers (R, −, R) 11 and (R, +, R) 12 (Scheme 1). The atropisomers (S, +/−, S)-10 were similarly resolved to afford the other two optically pure isomers (S, −, S)-13 and (S, +, S)-14 (Scheme 1). The optical configuration and purity of each atropisomer was determined using a polorimeter and liquid chiral column chromatography (Table 1 and Supporting Information Figure 1). The optical rotation ([a]) generated by atropisomer (axial chirality) and 2-phenyl propyl groups in compound 4 was approximately +/− 18.5 ° and 33.5 °, respectively (Table 1).

Table 1.

Optical Activity and Chiral HPLC Purity of four Diastereoisomers of Compound 4.

| Compd | Optical Activity | Optical rotation [α] (C = 0.1 in EtOH) | HPLC Purity (−) : (+) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 14 | (S, +, S) | −9.7 ± 0.5° | 0.49 : 99.51 |

| 10 | (S, +/−, S) | −29.0 ± 1.0° | 49.43 : 50.57 |

| 13 | (S, −, S) | −49.0 ± 1.0° | 99.13 : 0.87 |

| 11 | (R, −, R) | +17.7 ± 0.5° | 99.50 : 0.5 |

| 9 | (R, +/−, R) | +35.0 ± 0.5° | 49.8 : 50.2 |

| 12 | (R, +, R) | +53.0 ± 1.5° | 0.39 : 99.61 |

| 4 | (RS, +/−, RS) | +1.0 ± 0.5° | 48.16 : 51.84 |

|

(R) | +34.2 ± 0.1° a* | 99 : 1 |

|

(S) | −32.8 ± 0.1° b* | 99 : 1 |

Optical activity [α]22/D + 35.0°, C = 1 in Ethanol, commercially available from Sigma-Aldrich.

Optical activity [α]22/D − 35.0°, C = 1 in Ethanol, commercially available from Sigma-Aldrich.

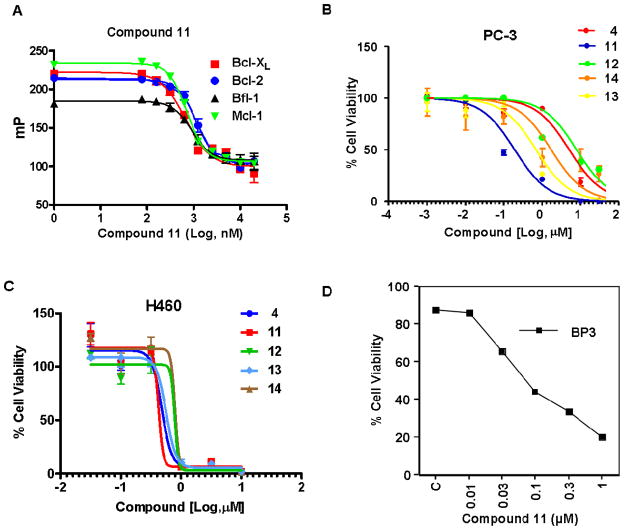

Four pure diastereoisomers, namely compounds 11, 12, 13, 14, were first tested by one-dimensional 1H nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy (1D-1H NMR) binding assays against Bcl-XL, as we reported previously (Figure 1C).24 Compounds 11–14 displayed significant binding to Bcl-XL in these assays (Figure 1C). However, compared to other diastereoisomers, compound 11 induced larger chemical shift perturbations in the active site methyl groups (region between −0.38 and 0.42 ppm) in the one-dimensional 1H-NMR spectrum of Bcl-XL (Figure 1C). To confirm the result from the one-dimensional 1H-NMR binding assay, we also produced uniformly 15N-labeled Bcl-XL and measured 2D [15N,1H]-TROSY correlation spectra in the absence and presence of compound 11 (Figure 1D). Compound 11 displayed low to submicromolar binding affinity to Bcl-XL, as qualitatively evaluated by the nature of the shifts at the ligand/protein ratio of 1:1. To further confirm these results, we evaluated the binding affinity of four pure isomers 11–14 using Isothermal Titration Calorimetry assay (ITC), competitive fluorescence polarization assays (FPA) and cell viability assays (Figure 2, Tables 2 and 3). In agreement with NMR binding assays, compound 11 displayed tight binding affinity to Bcl-XL with a Kd value of 0.11 μM in the ITC assay, which is 4–20 times more potent than other isomers 12–14 in the same assay (Table 2). Compound 11 also displayed the best inhibitory properties against Bcl-XL in the FP assay compared to the other pure isomers 12–14 and isomer mixture 4, with an IC50 value of 0.31 μM (Figure 2B). Compound 11 also displayed superior cell membrane permeability compared to other compounds (12–14) (Table 4). Consistent with NMR binding, ITC, FPA and cell permeability data, compound 11 was more effective compared to other compounds (4, 12–14) in inhibiting growth of PC3 cells, which expressed high levels of Bcl-XL. The EC50 value of 11 in killing PC3 cells was 0.13 μM, hence 4–36 fold more potent than other compounds (4 and 12–14) (Figure 2B and Table 3). Overall, considering both in vitro binding and displacement assays and cell killing properties, we concluded that anti-Bcl-XL properties of optically pure isomers 11–14 were affected largely by the atropisomers, with the (−) isomers being consistently more potent than the corresponding (+) isomers. This was in agreement with previous observations that lead to the selection of (−) 1 (Gossypol, AT101) for clinical trials.13 In fact, atropisomers (−) 1 and (+) 1 bound to Bcl-XL with IC50 values of 0.48 and 0.54 μM, respectively, in FPA assays while their EC50 values in killing PC3 cells were 3.3 and 17.8 μM, respectively.13 Compound 11 was more potent compared to (−) 1 in both assays.

Figure 2.

(A) Fluorescence polarization-based competitive binding curves of compound 11 for Bcl-XL (red squares), Bcl-2 (blue dots), Bfl-1 (dark up triangle) and Mcl-1 (green up triangle) (B) Inhibition of cell growth by compound 4 (red dots), 11 (blue dots), 12 (green dots), 13 (yellow dots) and 14 (orange dots) in the PC-3 human prostate cancer cell line. Cells were treated for 3 days and cell viability was evaluated using ATP-LITE assay. (C) Inhibition of cell growth by compound 4 (deep blue dots), 11 (red square), 12 (green down triangle), 13 (light blue diamonds) and 14 (grey up triangle) in the H460 human lung cancer cell line. Cells were treated for 3 days and cell viability was evaluated using ATP-LITE assay. (D) Inhibition of cell growth by compound 11 (dark square) in the human BP3 cell line. Apoptosis was monitored by Annexin V-FITC assays.

Table 2.

Cross-activity of Diastereoisomers of 4 against Bcl-XL, Bcl-2, Mcl-1 and Bfl-1 in Fluorescence Polarization displacement assays and binding to Bcl-xL as measured via Isothermal Titration Calorimetry.

| Compound | IC50 (μM) FPA | Kd (μM) ITC | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IC50 | Bcl-XL | Bcl-2 | Bfl-1 | Mcl-1 | Bcl-XL |

| 11 | 0.31 ± 0.05 | 0.32 ± 0.05 | 0.62 ± 0.04 | 0.20 ± 0.02 | 0.1 |

| 12 | 0.68 ± 0.09 | 1.14 ± 0.09 | 0.59 ± 0.07 | 0.18 ± 0.02 | 2.4 |

| 13 | 0.44 ± 0.02 | 0.43 ± 0.01 | 0.75 ± 0.07 | 0.24 ± 0.02 | 0.4 |

| 14 | 0.65 ± 0.06 | 0.43 ± 0.03 | 0.77 ± 0.05 | 0.24 ± 0.02 | 2.0 |

| 4 | 0.39 ± 0.02 | 0.66 ± 0.02 | 0.42 ± 0.09 | 0.33 ± 0.02 | ND |

ND = Not determined

Table 3.

Efficacy (EC50 values in μM) of diastereoisomers of compound 4 against prostate cancer cells (PC3), lung cancer cells (H460) and lymphoma cell (BP3).

| Compound | PC3a* | H460a* | BP3b* |

|---|---|---|---|

| EC50, μM | EC50, μM | EC50, μM | |

| 11 | 0.13 ± 0.02 | 0.42 ± 0.09 | 0.049 |

| 12 | 4.64 ± 1.07 | 0.78 ± 0.10 | 0.072 |

| 13 | 0.47 ± 0.10 | 0.56 ± 0.08 | 0.31 |

| 14 | 1.61 ± 0.45 | 0.80 ± 0.09 | 0.12 |

| 4 | 2.45 ± 0.50 | 0.47 ± 0.18 | 0.61 |

Determined using the ATP-LITE assay

Determined using Annexin V-FITC and propidium iodide assay

Table 4.

Plasma stability, Microsomal stability, and Cell Membrane Permeability of diastereoisomers 11–14.

| Compound | Plasma stability (T = 1 h) | Microsomal Stability (T = 40 min) | Cell Permeability (LogPe) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 11 | 41% | 89.6 ± 7.0 % | −6.70 ± 0.30 |

| 12 | 28% | 83.4 ± 8.1 % | −7.69 ± 0.14 |

| 13 | 42% | 86.3 ± 7.0 % | −7.78 ± 0.06 |

| 14 | 41% | 91.6 ± 1.6 % | −7.85 ± 0.13 |

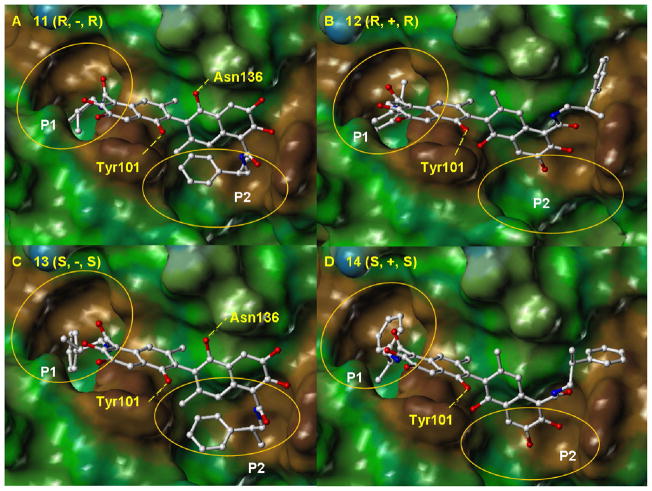

To further rationalize these observations, molecular docking studies of diastereoisomers 11–14 (Figure 3) into the BH3 binding groove in Bcl-XL were performed. These studies suggested that although the left half components of (−) and (+) atropisomers bound similarly to Bcl-XL, their right parts had remarkably different binding models (Figure 3). (−) Atropisomers 11 and 13 not only fully occupied the right hydrophobic pockets (P2) but also formed hydrogen bonding involving their 1′ hydroxyl groups on the right naphthalene ring (Figure 3A). On the contrary, (+) atropisomers 12 and 14 could not occupy the right hydrophobic pocket (P2) or form a hydrogen bond with their 1′ hydroxyl groups. The GOLD score of (−) atropisomer 11 was 39.03 which was greater than 34.16 for (+) atropisomer 12. In agreement with FPA and cell data for Bcl-XL, molecular docking studies further suggested that the two centers of chirality generated from 2-phenyl propyl groups had little effect for isomers 11–14 to bind to Bcl-XL. For example, compound 11 and 13 with reverse configurations on 2-phenyl propyl groups had very similar orientations in Bcl-XL (Figure 3A and 3C) and their GOLD score were very similar, with values of 39.03 and 39.78, respectively. This binding trend was also observed for compound 12 and 14 (Figure 3B and 3D), with similar gold score of 34.16 and 34.49, respectively. This was not unexpected given that these isomers only differ for the arrangement of a small hydrogen atom and methyl group on the chiral carbon on 2-phenyl propyl group. Based on these observations we decided not to explore the asymmetric synthesis of the (R, −, S) isomer but rather to focus our effects in the characterization of the (R, −, R) isomer, compound 11, as reported below.

Figure 3.

Molecular docking studies. Stereo views of docked structures of (A) Compound 11. (B) Compound 12. (C) Compound 13. (D) Compound 14 into Bcl-XL (PDB ID:2YXJ).

In additional to Bcl-XL, other members of the Bcl-2 family were known to play critical roles in cancer cell survival.25, 26 Therefore, we further evaluated the binding properties and specificity of isomers 11–14 against Bcl-2, Mcl-1 and Bfl-1 using FP assays (Table 2 and Figure 2C). All four isomers (11–14) displayed significant displacement properties against Bcl-2, Mcl-1 and Bfl-1 in FP assays with average IC50 values of 0.32, 0.22 and 0.65 μM, respectively (Table 2). To confirm the result from FP assays, we also produced uniformly 15N-labeled Mcl-1 protein and measured 2D [15N,1H]-TROSY correlation spectra in the absence and presence of compound 11 (Supporting Information Figure 2A). Compound 11 displayed a significant binding to Mcl-1, as qualitatively evaluated by the nature of the shifts at the ligand/protein ratio of 2:1. Compound 11 showed inhibitory properties against Bcl-2 compared to other compounds (4, 12–14), with an IC50 value of 0.32 μM in FP assays. Consistent with FPA data, compound 11 displayed best efficacies compared to other compounds (4, 12–14) in inhibiting growth of H460 cells, which expressed high level of Bcl-2.27–29 The IC50 values of 11 in killing H460 cells was 0.42 μM, hence approximately 2-fold more potent than compounds 12 and 14 (Table 2, 3 and Figure 2C). These observations were consistent with atropisomers (−) 1 and (+) 1, which bound to Bcl-2 with an IC50 value of 0.26 and 0.30 μM, respectively, in FPA assays and their EC50 value in killing MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells was around 2.0 and 10.0 μM, respectively.13 Compound 11 had similar binding affinity as other isomers (12–14) for Mcl-1 and Bfl-1 in FP assays, which could be due to structural difference of their BH3 binding pockets (Supporting Information Figure 2B and 2C) 30, 31

We further evaluated the ability of compounds 11–14 to induce apoptosis of the human BP3 cell line, which originated from a human diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL).20, 26 For these assays, we used Annexin V-FITC and propidium iodide (PI) double staining, followed by flow-cytometry analysis (Table 3). Compounds 11–14 effectively induced apoptosis of the BP3 cell line in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 2D, Table 3 and Supporting Information Figure 3A and 3B). In particular, compound 11 was most effective with an IC50 value of 0.049 μM, which was approximately two- to six-fold more potent than other diastereoisomers 12–14 (Figure 2D, Table 3 and Supplementary Figure 3A and 3B). The mRNA ratio of Bfl-1, Bcl-XL and Mcl-1 was approximately 10:3:1 in BP3 cell lines.26 However, we determined by Western Blot that BP3 cells expressed high levels of both Bfl-1 and Mcl-1.20 In agreement with these observations, the potent dual Bcl-XL and Bcl-2 antagonist ABT-73732 displayed no cytotoxic activity against BP3 cell lines presumably because ABT737 was not effective against Mcl-1 and Bfl-1.25, 32, 33

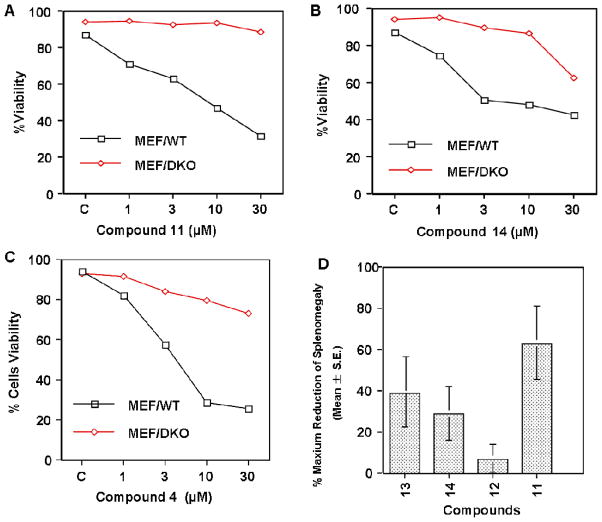

We next explored whether pure diastereoisomers 11–14 and diastereoisomer mixture 4 had cytotoxic properties against wild type mouse embryonic fibroblast cells (MEF/WT) and transformed Bax/Bak double knockout MEF cells (MEF/DKO) in which anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins lacked a cytoprotective phenotype.34, 35 Compound 11 displayed slight toxicity in Bak/Bak double knockout mouse embryonic fibroblast cells (MEF/DKO) at 30 μM while it killed almost 70% wild type mouse embryonic fibroblast cells (MEF/WT) at same concentration using FITC-Annexin V/PI assays (Figure 4A), implying that the compound 11 only displayed slight off-target effects. In contrast, compound 14 seemed almost equally effective in killing both MEF/WT and MEF/DKO at 30 μM (Figure 4B), suggesting that other possible killing mechanisms not related to Bcl-2 inhibition were induced by this compound. Accordingly, the mixture of isomers 4 displayed higher cytotoxicity in MEF/DKO cells at 3–30 μM compared to the optically pure isomer 11, indicating that the optically pure isomer was more selective (Figure 4C).

Figure 4.

Mouse embryonic fibroblast cells with wild-type (MEF/WT; dark square) or bax−/−bak−/− double knockout (MEF/DKO, red square) genotypes were treated with compounds 11, 14 and 4 at various concentrations and apoptosis was monitored by Annexin V-FITC assays. (A-C) Compounds 11, 14 and 4. (D) Effects of compounds 11–14 on shrinkage of Bcl-2 mouse spleen at a single intraperitoneal injection dose of 42 mg/kg. All shrinkage data are percentage of maximum reduction of mice spleen size.

Next, we examined the pharmacological properties of the isomers as chirality could greatly affect such properties due to stereoselective metabolism. To test the pharmacological properties of diastereoisomers 11–14, we determined their in vitro rat plasma stability, rat microsomal stability, and cell membrane permeability (Table 4). From these studies, we could conclude that compound 11 displayed superior cell membrane permeability compared to other diastereoisomers 12–14. The LogPe value of compound 11 was −6.7, which indicates good cell membrane permeability, while LogPe values of other compounds (12–14) were around −7.8, which corresponded to relative poor cell membrane permeability. Compound 11 also displayed relatively good microsomal stability (Table 4) in which the compound degraded 10.4 % after 40 minutes incubation in rat microsomal preparations. In contrast, compound 12 displayed decreased plasma and microsomal stability compared to other diastereoisomers. Compound 11 also displayed better chemical stability compared to other compounds (12–14) at different temperatures (Supporting Information Figure 5)

Hence, using a combination of NMR-based binding assays, FP assays, ITC assays, cytotoxicity assays and preliminary in vitro ADME data, we selected pan-Bcl-2 antagonists to be further tested in vivo models. Unlike currently available antagonists,32, 36 our compounds were effective in inhibiting several of the anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 proteins, hence were expected to display in vivo efficacy against a variety of mice models of cancer that relied on different Bcl-2 proteins for growth and progression. To test this hypothesis we selected two different models: Bcl-2 transgenic mouse model and prostate cancer xenograft model that relied on Mcl-1 overexpression. B-cells of the B6 transgenic mice overexpressed human Bcl-2 and accumulated in the spleen of mice.17, 20 Because we had determined that the spleen weight was highly consistent in age- and sex-matched Bcl-2-transgenic mice, varying by only ±2% among control Bcl-2 mice,17 the spleen weight was used as an end-point for assessing in vivo activity. We tested the in vivo activities of isomers 11–14 in two Bcl-2 transgenic mice with a single intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection at 42 mg/kg. In agreement with in vitro data, compound 11 displayed superior in vivo activity compared to other isomers (12–14) in this model. It induced more than 30% spleen weight reduction compared to ≤20% induced by other diastereoisomers. Since the maximum spleen shrinkage would be no more than 50% in this experimental model,20 these compounds induced near 65% maximal biological activity, while other isomers 12–14 induced ≤40% of maximum reduction in spleen weight at the same dose. In particular, compound 12 displayed weak in vivo activity, which was in consistent with its relatively weak cell activity and poor pharmacological properties. All mice tolerated the treatment well, with only mild signs of GI toxicity.

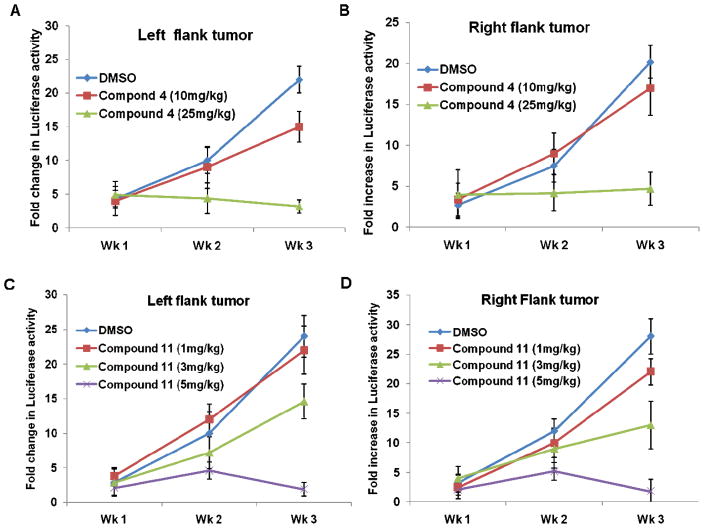

As mentioned, current available experimental treatments targeting Bcl-2 proteins failed to address Mcl-1 as a critical regulator of cancer survival. In fact, the potent Bcl-XL/Bcl-2 antagonist ABT-737 (Abbott Laboratories) and the Bcl-2 antisense Genasense (Genta) were not effective against cancer cells that overexpress Mcl-1.32,36 Therefore, to further examine the therapeutic potential of compound 11 as a single agent against tumors that relied on Mcl-1 for survival, compound 11 was evaluated side by side with compound 4 in a prostate cancer xenograft using the M2182 cell line. M2182 was a tumorigenic variant of normal prostate epithelial P69 cell and highly overexpressed Mcl-1.37–40 A quantity of 1 × 106 M2182 cells were injected subcutaneously in the left and right flanks of male athymic nude mice, and the tumors were allowed to grow to an average size of ≈ 75 mm3 prior to initiation of therapy. Compounds 4 and 11 were administrated (i.p.) every 2 days (total of nine injections) and compound 4 was injected at two doses, 10 and 25 mg/kg while compound 11 was administrated at three lower doses, 1, 3 and 5 mg/kg due to its superior in vitro properties compared to compound 4. Compound 11 and 4 displayed a marked inhibitory effect of tumor size compared with the control group (Figure 5A-D and Supporting Information Figure 5A and 5B). In fact, compound 11 at the dose of 5 mg/kg (Figure 5C, 5D, Supporting Information Figure 5A and 5B) and compound 4 at the dose of 25 mg/kg (Figure 5A and 5B) induced near complete inhibition of tumor growth in both flanks compared with their control groups. As anticipated, compound 11 displayed better tumor growth inhibitory effect compared to compound 4. Even at the dose of 3 mg/kg, compound 11 inhibited tumor growth to ~60% of the tumor volume in the control group (Figure 5C, 5D, Supporting Information Figure 5A and 5B) while compound 4 displayed weak inhibitory effect of tumor size at the dose of 10 mg/kg (Figure 5A and 5B). All mice tolerated the treatment well with no apparent signs of toxicity.

Figure 5.

Characterization of compounds 4 and 11 in tumor xenografts model. Tumor xenografts from M2182 cells were established in athymic nude mice on the left and right flanks. After establishing visible tumors of ~75-mm3, DMSO or compounds (4 or 11) were given (i.p.) every two days (total of nine injections). A minimum of five animals was used per experimental group. For in vivo imaging of tumors the mice were anesthetized and injected i.p. with 150 mg/kg luciferin and light emitted from each tumor was determined in a xenogen system with CCD camera using an integration time of 1 min. Luminescence measurements were made using Living Image software (version 2.50.1; Xenogen). At the end of the experiment, the animals were sacrificed, and the tumors were removed and photographed. (A) Left flank tumor treated with compound 4 at dose of 10 mg/kg and 25 mg/kg, respectively. (B) Right flank tumor treated with compound 4 at dose of 10 mg/kg and 25 mg/kg, respectively. (C) Left flank tumor treated with compound 11 at dose of 1, 3 and 5 mg/kg, respectively. (D) Right flank tumor treated with compound 11 at doses of 1, 3 and 5 mg/kg, respectively.

Conclusions

In summary, we synthesized and evaluated four diastereoisomers (11–14) of compound 4 in a variety of in vitro and in vivo assays. The optically pure compound 11 inhibits the binding of BH3 peptides to Bcl-XL, Bcl-2, Mcl-1 and Bfl-1 with IC50 values of 0.31, 0.32, 0.20 and 0.62 μM, respectively. The compound 11 also potently inhibits cell growth of human prostate cancer, lung cancer and BP3 B-cell lymphoma cell lines with EC50 values of 0.13, 0.56 and 0.049 μM, respectively. The compound 11 displays approximately 20-fold and 12-fold greater efficacy in inhibiting growth of PC-3 and BP3 cell, respectively, compared to the compound 4 which was previously disclosed. 20 Compound 11 also shows less cytotoxicity against bax−/−bak−/− cells compared to compound 4, indicating that it kills cancers cells predominantly via the intended mechanism. Compound 11 displays in vivo efficacy in transgenic mice in which Bcl-2 is overexpressed in splenic B-cells and also demonstrats superior single-agent antitumor efficacy compared to compound 4 in a prostate cancer mouse xenograft model that depends on Mcl-1 for survival. Considering the critical roles of anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins in tumorgenesis, chemoresistance, and the potent inhibitory activity of compound 11 against anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins, compound 11 represents a viable drug candidate for the development of novel apoptosis-based cancer therapies.

Experimental Section

General Synthetic Procedures

Unless otherwise indicated, all reagents and anhydrous solvents (CH2Cl2, THF, diethyl ether, etc) were obtained from commercial sources and used without purification. All reactions were performed in oven-dried glassware. All reactions involving air or moisture sensitive reagents were performed under a nitrogen atmosphere. Silica gel or reverse phase chromatography was performed using prepacked silica gel or C-18 cartridges (RediSep), respectively. All final compounds were purified to > 95% purity, as determined by a HPLC Breeze from Waters Co. using an Atlantis T3 3 μM 4.6 mm × 150 mm reverse phase column. Compounds 11–14 were isolated using a CHIRALCEL OD-RH 5 μM 250 mm × 10 mm reverse phase chiral column and the enantiomeric purity of compounds 11–14 was analyzed using a CHIRALCEL OD-RH 5 μM 250 mm × 4.6 mm reverse phase chiral column on a HPLC from Water Corp. The eluant was a linear gradient with a flow rate of 5 mL/min for preparative and 1 mL/min for analytical column, respectively, from 60% A and 40% B to 20% A and 80% B in 15 min followed by 5 min at 100% B (Solvent A: H2O with 0.1% TFA; Solvent B: ACN with 0.1% TFA). Compounds were detected at λ = 254 nm. 1H NMR spectra were recorded on Bruker 600 MHz instruments. Chemical shifts are reported in ppm (δ) relative to 1H (Me4Si at 0.00 ppm). Coupling constant (J) are reported in Hz throughout. Mass spectral data were acquired on Shimadzu LCMS-2010EV for low resolution, and on an Agilent ESI-TOF for high resolution.

Compound 1 is commercially available from Yixin Pharmaceutical Co. HPLC purity 99.0%, tR = 12.50 min and synthesis of compounds 2, 4, 5 and 6 have been previously reported.20

1,1′,6,6′,7,7′-Hexamethoxy-3,3′-dimethyl-N5,N5′-bis(2-phenylpropyl)-2,2′-binaphthyl-5,5′-dicarboxamide (7)

Compound 6 (1.35 g, 2.45 mmol), EDCI (1.30 g, 6.76 mmol) and HOBT (910 mg, 6.76 mmol) were dissolved in 30 mL of dry CH2Cl2 and stirred at room temperature for 15 min under nitrogen atmosphere. (R)-β-methylphenethylamine (0.81 mL, 5.63 mmol) and N, N-diisopropylethylamine (1.7 mL, 9.8 mmol) were added and the reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 20 h. The mixture was then poured onto 100 mL of water and the solution was extracted with CH2Cl2 (3 × 100 mL). The ether extracts were washed with water and brine, dried over magnesium sulfate and filtered. Evaporation of the solvent in vacuo and the residue was purified by silica chromatography to give 1.46 g (76%) of compound 7 as a yellow solid. 1H NMR (600 MHz, CD3OD) δ 7.36 (s, 2H), 7.33 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 4H), 7.32 (t, J1 = 7.2 Hz, J2 = 6.6 Hz, 4H), 7.21 (m, 4H), 4.59(s, 4H), 3.98 (s, 6H), 3.85 (s, 6H), 3.76 (m, 2H), 3.63 (m, 2H), 3.54 (s, 3H), 3.53 (s, 3H), 2.01 (s, 3H), 2.00 (s, 3H), 1.38 (d, J1 = 6.0 Hz, 6H). HRMS calcd for C48H52N2O8 785.3796 (M + H), found 785.3790.

1,1′,6,6′,7,7′-Hexamethoxy-3,3′-dimethyl-N5,N5′-bis(2-phenylpropyl)-2,2′-binaphthyl-5,5′-dicarboxamide (8)

Compound 6 (1.0 g, 1.81 mmol), EDCI (960 mg, 5.0 mmol) and HOBT (181 mg, 1.34 mmol) were dissolved in 25 mL of dry CH2Cl2 and stirred at room temperature for 10 min under nitrogen atmosphere. (S)-β-methylphenethylamine (0.60 mL, 4.17 mmol) and N, N-diisopropylethylamine (1.26 mL, 7.3 mmol) were added and the reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 24 h. The mixture was then poured onto 50 mL of water and the solution was extracted with CH2Cl2 (3 × 100 mL). The ether extracts were washed with water and brine, dried over magnesium sulfate and filtered. Evaporation of the solvent in vacuo and the residue was purified by silica chromatography to give 0.87 g (60%) of compound 8 as a yellow solid. 1H NMR (600 MHz, CD3OD) δ (600 MHz, CD3OD) δ 7.48 (s, 2H), 7.36 (d, J = 6.0 Hz, 4H), 7.32 (t, J1 = 7.2 Hz, J2 = 7.2 Hz, 4H), 7.22 (m, 4H), 4.59 (s, 4H), 3.98 (s, 6H), 3.84 (s, 6H), 3.76 (m, 2H), 3.63 (m, 2H), 3.54 (s, 3H), 3.53 (s, 3H), 2.01 (s, 3H), 1.99 (s, 3H), 1.38 (d, J1 = 6.6 Hz, 6H). HRMS calcd for C48H52N2O8 785.3796 (M + H), found 785.3788.

1,1′,6,6′,7,7′-Hexahydroxy-3,3′-dimethyl-N5,N5′-bis(2-phenylpropyl)-2,2′-binaphthyl-5,5′-dicarboxamide (9)

0.65 mL of BBr3 solution (1.72 g, 6.85 mmol) was added dropwise into a solution of compound 7 (420 mg, 0.55 mmol) in 20 mL of anhydrous CH2Cl2 at −78 °C. Stirring was continued at −78 °C for 1 h, 0 °C for 1 h, and ambient temperature for 1 h. 50 grams of ice containing 10 mL of 6M HCl was added to the mixture and stirred for 30 min at room temperature. The aqueous layer was extracted with ethyl acetate (3 × 60 mL). The combined organic layer was washed with water, brine and dried over MgSO4. The solvent was concentrated in vacuo and the residue was purified using C-18 column chromatography followed by preparative HPLC (H2O/Acetonitrile) to give 150 mg of compound 9 (39%) as white-yellow solid. 1H NMR (600 MHz, CD3OD) δ 7.39 (d, J = 4.2 Hz, 2H), 7.19 (m, 4H), 7.15 (t, J1 = 6.0 Hz, J2 = 6.0 Hz, 4H), 7.03 (t, J1 = 6.0 Hz, J2 = 6.0 Hz, 2H), 6.89 (s, 1H), 6.81 (s, 1H), 3.49 (m, 4H), 3.02 (m, 2H), 1.72 (s, 3H), 1.71 (s, 3H), 1.25 (s, 3H), 1.24 (s, 3H). HRMS calcd for C42H40N2O8 701.2857 (M + H), found 701.2865. 100 mg of compound 9 was further purified using a CHIRALCEL OD-RH 5 μM 250 mm × 10 mm reverse phase chiral column to give 25 mg of compound 11 and 28 mg of compound 12, respectively.

(S)-1,1′,6,6′,7,7′-hexahydroxy-3,3′-dimethyl-N5-((R)-2-phenylpropyl)-N5′-((R)-2-phenylpropyl)-2,2′-binaphthyl-5,5′-dicarboxamide (11)

1H NMR (600 MHz, CD3OD) δ 7.57 (s, 2H), 7.37 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 4H), 7.33 (t, J1 = 7.2 Hz, J2 = 7.8 Hz, 4H), 7.22 (t, J1 = J2 = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 7.07 (s, 2H), 3.67 (m, 4H), 3.23 (m, 2H), 1.90 (s, 6H), 1.43 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 6H). 13C NMR (600 MHz, CD3OD) δ 169.73, 149.20, 144.64, 143.95, 133.86, 128.15, 127.17, 126.95, 126.10, 118.38, 116.60, 115.20, 114.37, 105.57, 46.40, 39.56, 19.33, 18.58. HPLC purity 99.0%, tR = 9.13 min. Enantiomeric purity 99.7%, tR = 12.35 min. HRMS calcd for C42H40N2O8 701.2857 (M + H), found 701.2854.

(R)-1,1′,6,6′,7,7′-hexahydroxy-3,3′-dimethyl-N5-((R)-2-phenylpropyl)-N5′-((R)-2-phenylpropyl)-2,2′-binaphthyl-5,5′-dicarboxamide (12)

1H NMR (600 MHz, CD3OD) δ 7.57 (s, 2H), 7.38 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 4H), 7.33 (t, J1 = 7.2 Hz, J2 = 7.8 Hz, 4H), 7.22 (t, J1 = J2 = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 6.99 (s, 2H), 3.75 (dd, J1 = 7.2 Hz, J2 = 13.2 Hz, 2H), 3.62 (dd, J1 = 7.2 Hz, J2 = 13.2 Hz, 2H), 3.20 (m, 2H), 1.89 (s, 6H), 1.42 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 6H). 13C NMR (600 MHz, CD3OD) δ 169.67, 149.18, 144.62, 144.54, 143.92, 133.85, 128.14, 127.16, 126.97, 126.12, 118.36, 116.59, 115.14, 114.35, 105.56, 46.34, 39.66, 19.63, 18.78. HPLC purity 99.0%, tR = 9.30 min. Enantiomeric purity 99.5%, tR = 10.28 min. HRMS calcd for C42H40N2O8 701.2857 (M + H), found 701.2848.

1,1′,6,6′,7,7′-Hexahydroxy-3,3′-dimethyl-N5,N5′-bis(2-phenylpropyl)-2,2′-binaphthyl-5,5′-dicarboxamide (10)

0.45 mL of BBr3 solution (1.18 g, 4.73 mmol) was added dropwise into a solution of compound 8 (310 mg, 0.40 mmol) in 20 mL of anhydrous CH2Cl2 at −78 °C. Stirring was continued at −78 °C for 1 h, 0 °C for 1 h, and ambient temperature for 1 h. 50 grams of ice containing 10 mL of 6M HCl was added to the mixture and stirred for 1 h at room temperature. The aqueous layer was extracted with dichloromethane (3 × 50 mL). The combined organic layer was washed with water, brine and dried over MgSO4. The solvent was concentrated in vacuo and the residue was purified using C-18 column chromatography (H2O/Acetonitrile) to give 200 mg of compound 10 (72%) as white-yellow solid. 1H NMR (600 MHz, CD3OD) δ 7.56 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 2H), 7.39 (t, J1 = 6.0 Hz, J2 = 3.0 Hz, 4H), 7.35 (t, J1 = 6.0 Hz, J2 = 6.6 Hz, 4H), 7.23 (t, J1 = 6.0 Hz, J2 = 6.6 Hz, 2H), 7.06 (s, 1H), 6.99 (s, 1H), 3.76 (dd, J1 = 6.6 Hz, J2 = 11.4 Hz, 1H), 3.68 (m, 3H), 3.22 (m, 2H), 1.90 (s, 3H), 1.89 (s, 3H), 1.43 (m, 6H). HRMS calcd for C42H40N2O8 701.2857 (M + H), found 701.2853. 150 mg of compound 10 was further purified using a CHIRALCEL OD-RH 5 μM 250 mm × 10 mm reverse phase chiral column to give 50 mg of compound 13 and 58 mg of compound 14, respectively.

(S)-1,1′,6,6′,7,7′-hexahydroxy-3,3′-dimethyl-N5-((S)-2-phenylpropyl)-N5′-((S)-2-phenylpropyl)-2,2′-binaphthyl-5,5′-dicarboxamide (13)

1H NMR (600 MHz, CD3OD) δ 7.57 (s, 2H), 7.38 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 4H), 7.33 (t, J1 = 7.2 Hz, J2 = 7.8 Hz, 4H), 7.22 (t, J1 = 7.2 Hz, J2 = 7.8 Hz, 2H), 6.99 (s, 2H), 3.75 (dd, J1 = 7.8 Hz, J2 = 13.2 Hz, 2H), 3.62 (dd, J1 = 7.8 Hz, J2 = 13.2 Hz, 2H), 3.20 (m, 2H), 1.89 (s, 6H), 1.40 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 6H). 13C NMR (600 MHz, CD3OD) δ 169.66, 149.17, 144.62, 144.54, 143.92, 133.85, 128.13, 127.16, 126.96, 126.11, 118.36, 116.60, 115.15, 114.34, 105.55, 46.33, 39.66, 19.35, 18.67. HPLC purity 99.4%, tR = 9.31 min. Enantiomeric purity 99.1%, tR = 12.38 min. HRMS calcd for C42H40N2O8 701.2857 (M + H), found 701.2849.

(R)-1,1′,6,6′,7,7′-hexahydroxy-3,3′-dimethyl-N5-((S)-2-phenylpropyl)-N5′-((S)-2-phenylpropyl)-2,2′-binaphthyl-5,5′-dicarboxamide (14)

1H NMR (600 MHz, CD3OD) δ 7.57 (s, 2H), 7.37 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 3H), 7.33 (t, J1 = 7.2 Hz, J2 = 7.8 Hz, 4H), 7.22 (t, J1 = J2 = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 7.06 (s, 2H), 3.66 (m, 4H), 3.22 (m, 2H), 1.90 (s, 6H), 1.40 (s, J = 6.6 Hz, 6H). 13C NMR (600 MHz, CD3OD) δ 169.71, 149.16, 14.64, 144.58, 144.03, 133.84, 128.15, 127.16, 126.95, 126.09, 118.41, 116.56, 115.23, 114.41, 105.57, 46.40, 39.56, 19.34, 18.60. HPLC purity 98.6%, tR = 9.22 min. Enantiomeric purity 99.5%, tR = 10.57 min. HRMS calcd for C42H40N2O8 701.2857 (M + H), found 701.2852.

Molecular Modeling

Molecular modeling studies were conducted on a Linux workstation and a 64 3.2-GHz CPUs Linux cluster. Docking studies were performed using the crystal structure of Bcl-XL and Mcl-1 in complex with a BH3 mimetic ligand (Protein Data Bank code 2YXJ and 2NL9, respectively).30, 32, 41, 42 The ligand was extracted from the protein structure and was used to define the binding site for small molecules. Compounds 11–14 were docked into the Bcl-2 family protein by the GOLD 43 docking program using GoldScore 44 as the scoring function. The active site radius was set at 10 Å and 10 GA solutions were generated for each molecule. The GA docking procedure in GOLD 43 allowed the small molecules to flexibly explore the best binding conformations whereas the protein structure was static. The protein surface was prepared with the program MOLCAD 45 as implemented in Sybyl (Tripos, St. Louis) and was used to analyze the binding poses for studied small molecules.

Fluorescence Polarization Assays (FPAs)

A Bak BH3 peptide (F-BakBH3) (GQVGRQLAIIGDDINR) was labeled at the N-terminus with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) (Molecular Probes) and purified by HPLC. For competitive binding assays, 100 nM GST–Bcl-XL ΔTM protein was preincubated with the tested compound at varying concentrations in 47.5 μL PBS (pH=7.4) in 96-well black plates at room temperature for 10 min, then 2.5 μL of 100 nM FITC-labeled Bak BH3 peptide was added to produce a final volume of 50 μL. The wild-type and mutant Bak BH3 peptides were included in each assay plate as positive and negative controls, respectively. After 30 min incubation at room temperature, the polarization values in millipolarization units 46 were measured at excitation/emission wavelengths of 480/535 nm with a multilabel plate reader (PerkinElmer). IC50 was determined by fitting the experimental data to a sigmoidal dose-response nonlinear regression model (SigmaPlot 10.0.1, Systat Software, Inc., San Jose, CA, USA). Data reported are mean of three independent experiments ± standard error (SE). Performance of Bcl-2 and Mcl-1 FPA are similar. Briefly, 50 nM of GST-Bcl-2 or -Mcl-1 were incubated with various concentrations of compound (4 and 11–14) for 2 min, then 15 nM FITC-conjugated-Bim BH3 peptide 47 was added in PBS buffer. Fluorescence polarization was measured after 10 min.

Cell Viability and Apoptosis Assays

The activity of the compounds against human cancer cell lines (PC3, H460, H1299) were assessed by using the ATP-LITE assay (PerkinElmer). All cells were seeded in either 12F2 or RPMI1640 medium with 5 mM L-glutamine supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum (Mediatech Inc.), penicillin and streptomycin (Omega). For maintenance, cells were cultured in 5% FBS. Cells plated into 96 well plates at varying initial densities depending on doubling time. H460 and H1299 plated at 2000 cells/well, and PC3 at 3000 cells/well. Compounds were diluted to final concentrations with 0.1% DMSO. Prior to dispensing compounds onto cells, fresh 5% media was placed into wells. Administration of compounds occurred 24 hours after seeding into the fresh media. Cell viability was evaluated using ATP-LITE reagent (PerkinElmer) after 72 hours of treatment. Data were normalized to the DMSO control-treated cells using Prism version 5.01 (Graphpad Software).

The apoptotic activity of the compounds against BP3 cells was assessed by staining with Annexin V- and propidium iodide (PI). BP3 cell line was cultured in RPMI 1640 medium (Mediatech Inc., Herndon, VA 20171) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (Mediatech Inc., Herndon, VA 20171) and Penicillin/Streptomycin (Mediatech Inc., Herndon, VA 20171). Cells were cultured with various concentrations of compounds 4 and 11–14 for 1 – 2 days. The percentage of viable cells was determined by FITC-Annexin V- and propidium iodide (PI)-labeling, using an Apoptosis Detection kit (BioVision Inc.), and analyzing stained cells by flow cytometry (FACSort; Bectin-Dickinson, Inc.; Mountain View, CA). Cells that were annexin-V-negative and PI-negative were considered viable.

The apoptotic activity of compounds 4 and 11–14 against mouse embryonic fibroblast wild-type cells (MEF/WT) and mouse embryonic fibroblast BAX/Bak double knockout cells (DKO/MEF) was assessed by staining with Annexin V- and propidium iodide (PI). Wild-type MEF and DKO/MEF were seeded in 24-well plate at a seeding density of half a million per well (in 1 ml of DMEM medium supplemented by 10% FCS). Next day, compound was added to wild-type and DKO cells at final concentration of 0, 2.5, 5.0, 7.5, 10 and 30 μM. On the following day, floating cells were pooled with adherent cells harvested after brief incubation with 0.25% Trypsin/EDTA solution (Gibco/In-Vitrogen Inc.). Cells were centrifuged and supernatant was discarded, and cell pellet was re-suspended with 0.2 ml of Annexin-V binding buffer, followed by addition of 1 μl Annexin-FITC and 1 μl PI (propidium iodide). The percentage of viable cells was determined by a 3-color FACSort instrument and data analyzed by Flow-Jo program, scoring Annexin V-negative, PI-negative as viable cells.

Bcl-2 Transgenic Mice Studies

Transgenic mice expressing Bcl-2 have been described as the B6 line.48 The BCL-2 transgene represents a minigene version of a t(14;18) translocation in which the human BCL-2 gene is fused with the immunoglobulin heavy-chain (IgH) locus and associated IgH enhancer. The transgene was propagated on the Balb/c background. These mice develop polyclonal B-cell hyperplasia with asynchronous transformation to monoclonal aggressive lymphomas beginning at approximately 6 months of age, with approximately 90% of mice undergoing transformation by the age of 12 to 24 months. All animals used here had not yet developed aggressive lymphoma.

Mouse Experiments

Compounds dissolved in 500 μL of solution (Ethanol: Cremophor EL: Saline = 10: 10: 80) were injected intraperitoneally to two age- and sex-matched B6Bcl2 mouse, while control-mice were injected intraperitoneally with 500 μL of the same formulation without compound. After 24 hours, B6Bcl2 mice were sacrificed by intraperitoneal injection of lethal dose of Avertin. Spleen was removed and weighed. The spleen weight of mice is used as an end-point for assessing activity as we determined that spleen weight is highly consistent in age- and sex-matched Bcl-2-transgenic mice in preliminary studies.17 Variability of spleen weight was within ±2% among control-treated age-matched, sex-matched B6Bcl2 mice.

M2182 Cell Lines and Stable Clones

M2182 progressed prostate cancer cells were obtained from Dr. Joy Ware (Virginia Commonwealth University, School of Medicine, Richmond, VA) and cultured as described.37 M2182 is a tumorigenic but non-metastatic variant of normal prostate epithelial P69 cells. pGL3 basic plasmid (Promega) was used to transfect M2182 cells using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Cells were then selected for 2 weeks in 200 μg/ml of hygromycin, and individual colonies were isolated, expanded, and maintained in 5 μg/ml hygromycin. The overexpression of luciferase in these clones was confirmed by measuring luciferase activity.

Human Prostate Cancer Xenografts in Athymic Nude Mice

M2182-Luc cells (1× 106) were injected s.c. in 100 μL of PBS in the left and right flanks of male athymic nude mice (NCRnu/nu, 4 weeks old, 20 g body weight) as described previously.40 After establishing visible tumors of ~75-mm3, requiring ~5–6 days, compound dissolved in 500 μL of solvent (ethanol/Cremophor EL/saline=10:10:80) were injected intraperitoneally (i.p.). The injections were given every 2 days for a total of nine injections. Three treatment groups were established for the experiment of compound 4, i.e., DMSO only, 10 mg/kg and 25 mg/kg of compound 4. Four treatment groups were established for the experiment of compound 11, i.e., DMSO only, 1 mg/kg, 3mg/kg and 5mg/kg of compound 11. A minimum of five animals was used per experimental condition. For in vivo imaging of tumors, the mice were anesthetized and injected i.p. with 150 mg/kg luciferin and light emitted from each tumor was determined using a Xenogen system with CCD camera with an integration time of 1 min. Luminescence measurements were made using Living Image software (version 2.50.1; Xenogen). At the end of the experiment, the animals were sacrificed, and the tumors were removed and photographed.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank NIH (Grant CA113318 to MP and JCR) and Coronado Biosciences (CSRA #08-02) for financial support.

Abbreviations list

- Bcl-2

B-cell lymphoma/leukemia-2

- EDCI

1-ethyl-3-(3′-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide

- 1D-1H NMR

one-dimensional 1H nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy

- SAR

Structure-activity relationship

- FPA

Fluorescence Polarization Assays

- ITC

Isothermal Titration Calorimetry

- WT

Wild type

- MEF

Mouse embryonic fibroblast cells

- DKO

Bax/Bak Double knockout

- MEF/DKO

Bax/Bak Double knockout mouse embryonic fibroblast cells

- ACN

Acetonitrile

- LC-MS

Liquid chromatography and tandem mass spectrometry

- HPLC

High-performance liquid chromatography

- TROSY

Transverse Relaxation-Optimized Spectroscopy

- ADME

Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, and Excretion

- DMSO

Dimethyl sulphoxide

- PAMPA

Parallel artificial membrane permeation assay

- FITC

Fluorescein isothiocyanate

- GST

Glutathione-S-transferase

- PBS

Phosphate-buffered saline

- SE

Standard error

- PI

Propidium iodide

- NADPH

Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate

- Rpm

Rotations Per Minute

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: An experimental section including information on isothermal titration calorimetry assays and in vitro ADME studies. This material is available free of charge via the internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Vaux DL, Korsmeyer SJ. Cell death in development. Cell. 1999;96:245–254. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80564-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reed JC. Dysregulation of apoptosis in cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:2941–2953. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.9.2941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johnstone RW, Ruefli AA, Lowe SW. Apoptosis: a link between cancer genetics and chemotherapy. Cell. 2002;108:153–164. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00625-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reed JC. Apoptosis-based therapies. Nature reviews Drug discovery. 2002;1:111–121. doi: 10.1038/nrd726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reed JC. Bcl-2 family proteins. Oncogene. 1998;17:3225–3236. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adams JM, Cory S. The Bcl-2 protein family: arbiters of cell survival. Science (New York, N Y ) 1998;281:1322–1326. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5381.1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gross A, McDonnell JM, Korsmeyer SJ. BCL-2 family members and the mitochondria in apoptosis. Genes & development. 1999;13:1899–1911. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.15.1899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang JL, Liu D, Zhang ZJ, Shan S, Han X, Srinivasula SM, Croce CM, Alnemri ES, Huang Z. Structure-based discovery of an organic compound that binds Bcl-2 protein and induces apoptosis of tumor cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2000;97:7124–7129. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.13.7124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Degterev A, Lugovskoy A, Cardone M, Mulley B, Wagner G, Mitchison T, Yuan J. Identification of small-molecule inhibitors of interaction between the BH3 domain and Bcl-xL. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:173–182. doi: 10.1038/35055085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reed JC. Bcl-2 family proteins: strategies for overcoming chemoresistance in cancer. Advances in pharmacology (San Diego, Calif ) 1997;41:501–532. doi: 10.1016/s1054-3589(08)61070-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kitada S, Leone M, Sareth S, Zhai D, Reed JC, Pellecchia M. Discovery, characterization, and structure-activity relationships studies of proapoptotic polyphenols targeting B-cell lymphocyte/leukemia-2 proteins. Journal of medicinal chemistry. 2003;46:4259–4264. doi: 10.1021/jm030190z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang M, Liu H, Guo R, Ling Y, Wu X, Li B, Roller PP, Wang S, Yang D. Molecular mechanism of gossypol-induced cell growth inhibition and cell death of HT-29 human colon carcinoma cells. Biochemical pharmacology. 2003;66:93–103. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(03)00248-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang S, Yang D. Small Molecular Antagonists of Bcl-2 family proteins. 2004/0214902. US patent applications series no. 2004:A1.

- 14.Wang G, Nikolovska-Coleska Z, Yang CY, Wang R, Tang G, Guo J, Shangary S, Qiu S, Gao W, Yang D, Meagher J, Stuckey J, Krajewski K, Jiang S, Roller PP, Abaan HO, Tomita Y, Wang S. Structure-based design of potent small-molecule inhibitors of anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 proteins. Journal of medicinal chemistry. 2006;49:6139–6142. doi: 10.1021/jm060460o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mohammad RM, Wang S, Aboukameel A, Chen B, Wu X, Chen J, Al-Katib A. Preclinical studies of a nonpeptidic small-molecule inhibitor of Bcl-2 and Bcl-X(L) [(−)-gossypol] against diffuse large cell lymphoma. Mol Cancer Ther. 2005;4:13–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Becattini B, Kitada S, Leone M, Monosov E, Chandler S, Zhai D, Kipps TJ, Reed JC, Pellecchia M. Rational design and real time, in-cell detection of the proapoptotic activity of a novel compound targeting Bcl-X(L) Chemistry & biology. 2004;11:389–395. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2004.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kitada S, Kress CL, Krajewska M, Jia L, Pellecchia M, Reed JC. Bcl-2 antagonist apogossypol (NSC736630) displays single-agent activity in Bcl-2-transgenic mice and has superior efficacy with less toxicity compared with gossypol (NSC19048) Blood. 2008;111:3211–3219. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-09-113647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Coward L, Gorman G, Noker P, Kerstner-Wood C, Pellecchia M, Reed JC, Jia L. Quantitative determination of apogossypol, a pro-apoptotic analog of gossypol, in mouse plasma using LC/MS/MS. Journal of pharmaceutical and biomedical analysis. 2006;42:581–586. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2006.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wei J, Rega MF, Kitada S, Yuan H, Zhai D, Risbood P, Seltzman HH, Twine CE, Reed JC, Pellecchia M. Synthesis and evaluation of Apogossypol atropisomers as potential Bcl-xL antagonists. Cancer Lett. 2009;273:107–113. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.07.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wei J, Kitada S, Rega MF, Stebbins JL, Zhai D, Cellitti J, Yuan H, Emdadi A, Dahl R, Zhang Z, Yang L, Reed JC, Pellecchia M. Apogossypol derivatives as pan-active inhibitors of antiapoptotic B-cell lymphoma/leukemia-2 (Bcl-2) family proteins. Journal of medicinal chemistry. 2009;52:4511–4523. doi: 10.1021/jm900472s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wei J, Kitada S, Rega MF, Emdadi A, Yuan H, Cellitti J, Stebbins JL, Zhai D, Sun J, Yang L, Dahl R, Zhang Z, Wu B, Wang S, Reed TA, Lawrence N, Sebti S, Reed JC, Pellecchia M. Apogossypol derivatives as antagonists of antiapoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins. Mol Cancer Ther. 2009;8:904–913. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-1050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yamanoi Y, Nishihara H. Direct and selective arylation of tertiary silanes with rhodium catalyst. J Org Chem. 2008;73:6671–6678. doi: 10.1021/jo8008148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Royer RE, Deck LM, Vander Jagt TJ, Martinez FJ, Mills RG, Young SA, Vander Jagt DL. Synthesis and anti-HIV activity of 1,1′-dideoxygossypol and related compounds. J Med Chem. 1995;38:2427–2432. doi: 10.1021/jm00013a018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rega MF, Leone M, Jung D, Cotton NJ, Stebbins JL, Pellecchia M. Structure-based discovery of a new class of Bcl-xL antagonists. Bioorg Chem. 2007;35:344–353. doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2007.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wesarg E, Hoffarth S, Wiewrodt R, Kroll M, Biesterfeld S, Huber C, Schuler M. Targeting BCL-2 family proteins to overcome drug resistance in non-small cell lung cancer. Int J Cancer. 2007;121:2387–2394. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brien G, Trescol-Biemont MC, Bonnefoy-Berard N. Downregulation of Bfl-1 protein expression sensitizes malignant B cells to apoptosis. Oncogene. 2007;26:5828–32. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li J, Viallet J, Haura EB. A small molecule pan-Bcl-2 family inhibitor, GX15-070, induces apoptosis and enhances cisplatin-induced apoptosis in non-small cell lung cancer cells. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2008;61:525–534. doi: 10.1007/s00280-007-0499-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Voortman J, Checinska A, Giaccone G, Rodriguez JA, Kruyt FA. Bortezomib, but not cisplatin, induces mitochondria-dependent apoptosis accompanied by up-regulation of noxa in the non-small cell lung cancer cell line NCI-H460. Mol Cancer Ther. 2007;6:1046–1053. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ferreira CG, Span SW, Peters GJ, Kruyt FA, Giaccone G. Chemotherapy triggers apoptosis in a caspase-8-dependent and mitochondria-controlled manner in the non-small cell lung cancer cell line NCI-H460. Cancer Res. 2000;60:7133–7141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee EF, Czabotar PE, Smith BJ, Deshayes K, Zobel K, Colman PM, Fairlie WD. Crystal structure of ABT-737 complexed with Bcl-xL: implications for selectivity of antagonists of the Bcl-2 family. Cell death and differentiation. 2007;14:1711–1713. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang H, Cowan-Jacob SW, Simonen M, Greenhalf W, Heim J, Meyhack B. Structural basis of BFL-1 for its interaction with BAX and its anti-apoptotic action in mammalian and yeast cells. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:11092–11099. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.15.11092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oltersdorf T, Elmore SW, Shoemaker AR, Armstrong RC, Augeri DJ, Belli BA, Bruncko M, Deckwerth TL, Dinges J, Hajduk PJ, Joseph MK, Kitada S, Korsmeyer SJ, Kunzer AR, Letai A, Li C, Mitten MJ, Nettesheim DG, Ng S, Nimmer PM, O’Connor JM, Oleksijew A, Petros AM, Reed JC, Shen W, Tahir SK, Thompson CB, Tomaselli KJ, Wang B, Wendt MD, Zhang H, Fesik SW, Rosenberg SH. An inhibitor of Bcl-2 family proteins induces regression of solid tumours. Nature. 2005;435:677–681. doi: 10.1038/nature03579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cory S, Adams JM. Killing cancer cells by flipping the Bcl-2/Bax switch. Cancer cell. 2005;8:5–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wei MC, Zong WX, Cheng EH, Lindsten T, Panoutsakopoulou V, Ross AJ, Roth KA, MacGregor GR, Thompson CB, Korsmeyer SJ. Proapoptotic BAX and BAK: a requisite gateway to mitochondrial dysfunction and death. Science (New York, N Y ) 2001;292:727–730. doi: 10.1126/science.1059108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vogler M, Weber K, Dinsdale D, Schmitz I, Schulze-Osthoff K, Dyer MJ, Cohen GM. Different forms of cell death induced by putative BCL2 inhibitors. Cell Death Differ. 2009;16:1030–1039. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2009.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.van de Donk NW, Kamphuis MM, van Dijk M, Borst HP, Bloem AC, Lokhorst HM. Chemosensitization of myeloma plasma cells by an antisense-mediated downregulation of Bcl-2 protein. Leukemia. 2003;17:211–219. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lebedeva IV, Sarkar D, Su ZZ, Kitada S, Dent P, Stein CA, Reed JC, Fisher PB. Bcl-2 and Bcl-x(L) differentially protect human prostate cancer cells from induction of apoptosis by melanoma differentiation associated gene-7, mda-7/IL-24. Oncogene. 2003;22:8758–8773. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bae VL, Jackson-Cook CK, Maygarden SJ, Plymate SR, Chen J, Ware JL. Metastatic sublines of an SV40 large T antigen immortalized human prostate epithelial cell line. Prostate. 1998;34:275–282. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0045(19980301)34:4<275::aid-pros5>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sarkar D, Su ZZ, Vozhilla N, Park ES, Gupta P, Fisher PB. Dual cancer-specific targeting strategy cures primary and distant breast carcinomas in nude mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:14034–14039. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506837102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Su ZZ, Sarkar D, Emdad L, Duigou GJ, Young CS, Ware J, Randolph A, Valerie K, Fisher PB. Targeting gene expression selectively in cancer cells by using the progression-elevated gene-3 promoter. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:1059–1064. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409141102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bruncko M, Oost TK, Belli BA, Ding H, Joseph MK, Kunzer A, Martineau D, McClellan WJ, Mitten M, Ng SC, Nimmer PM, Oltersdorf T, Park CM, Petros AM, Shoemaker AR, Song X, Wang X, Wendt MD, Zhang H, Fesik SW, Rosenberg SH, Elmore SW. Studies leading to potent, dual inhibitors of Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL. J Med Chem. 2007;50:641–662. doi: 10.1021/jm061152t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Czabotar PE, Lee EF, van Delft MF, Day CL, Smith BJ, Huang DCS, Fairlie WD, Hinds MG, Colman PM. Structural insights into the degradation of Mcl-1 induced by BH3 domains. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104:6217–6222. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701297104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jones G, Willett P, Glen RC, Leach AR, Taylor R. Development and validation of a genetic algorithm for flexible docking. Journal of molecular biology. 1997;267:727–748. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Eldridge MD, Murray CW, Auton TR, Paolini GV, Mee RP. Empirical scoring functions: I. The development of a fast empirical scoring function to estimate the binding affinity of ligands in receptor complexes. J Comput Aided Mol Des. 1997;11:425–445. doi: 10.1023/a:1007996124545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Teschner M, Henn C, Vollhardt H, Reiling S, Brickmann J. Texture mapping: a new tool for molecular graphics. J Mol Graph. 1994;12:98–105. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(94)80074-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sattler M, Liang H, Nettesheim D, Meadows RP, Harlan JE, Eberstadt M, Yoon HS, Shuker SB, Chang BS, Minn AJ, Thompson CB, Fesik SW. Structure of Bcl-xL-Bak peptide complex: recognition between regulators of apoptosis. Science (New York, N Y ) 1997;275:983–986. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5302.983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ramjaun AR, Tomlinson S, Eddaoudi A, Downward J. Upregulation of two BH3-only proteins, Bmf and Bim, during TGF beta-induced apoptosis. Oncogene. 2007;26:970–981. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Katsumata M, Siegel RM, Louie DC, Miyashita T, Tsujimoto Y, Nowell PC, Greene MI, Reed JC. Differential effects of Bcl-2 on T and B cells in transgenic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:11376–11380. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.23.11376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.