Abstract

Stineman MG, Kwong PL, Kurichi JE, Prvu-Bettger JA, Vogel WB, Maislin G, Bates BE, Reker DM. The effectiveness of inpatient rehabilitation in the acute postoperative phase of care after transtibial or transfemoral amputation: study of an integrated health care delivery system. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2008;89:1863-72.

Objective

To compare outcomes between lower-extremity amputees who receive and do not receive acute postoperative inpatient rehabilitation within a large integrated health care delivery system.

Design

An observational study using multivariable propensity score risk adjustment to reduce treatment selection bias.

Setting

Data compiled from 9 administrative databases from Veterans Affairs Medical Centers.

Participants

A national cohort of veterans (N=2673) who underwent transtibial or transfemoral amputation between October 1, 2002, and September 30, 2004.

Interventions

Not applicable.

Main Outcome Measures

One-year cumulative survival, home discharge from the hospital, and prosthetic limb procurement within the first postoperative year.

Results

After reducing selection bias, patients who received acute postoperative inpatient rehabilitation compared to those with no evidence of inpatient rehabilitation had an increased likelihood of 1-year survival (odds ratio [OR]=1.51; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.26–1.80) and home discharge (OR=2.58; 95% CI, 2.17–3.06). Prosthetic limb procurement did not differ significantly between groups.

Conclusions

The receipt of rehabilitation in the acute postoperative inpatient period was associated with a greater likelihood of 1-year survival and home discharge from the hospital. Results support early postoperative inpatient rehabilitation following amputation.

Keywords: Amputation, Continuity of patient care, Delivery of health care, integrated, Lower-extremity, Outcome and process assessment (health care), Rehabilitation, Selection bias

Studying the needs and outcomes of people after transtibial or transfemoral amputation is critical at this time. In the United States, more than 60,000 major lower-extremity amputations were recorded in VHA facilities between 1989 and 19981 and more than 83,000 in Medicare facilities between 1969 and 1997.2 Changes in both VHA and Medicare policies are stimulating shifts from inpatient to outpatient services without empirical evidence either supporting or not supporting those services.

Despite the expected growth of the population of patients with lower-extremity amputation, their complex functional needs have been greatly understudied, and studies of rehabilitation interventions after amputation are urgently needed.3 A search of the Cochrane and Medline databases (November 2007) for studies related to either dysvascular or traumatic amputation failed to identify any experimental or quasi-experimental trials that addressed the effects of rehabilitation services on outcomes. One study4 applied multivariable techniques to adjust for patients’ propensity to receive rehabilitation. Results showed significantly higher likelihoods of community discharge from nursing homes among patients who received rehabilitation across 5 diagnostic categories, but there were too few amputees to conduct the analysis for this sixth diagnostic group. A second study5 found that longer periods of inpatient rehabilitation were associated with improved physical functioning among a cohort of 146 patients after traumatic amputation at a single trauma center. This study did not include dysvascular amputees. Previous studies of the effects of rehabilitation after amputation have largely been descriptive.6,7

Although only prospective RCTs can assign a causal effect of treatment to outcome differences, issues of clinical equipoise and blinding would make trials designed to test the efficacy of rehabilitation difficult. To achieve equipoise, it is necessary to meet the therapeutic obligation of being reasonably certain that the net therapeutic advantage of a set of interventions is of equal advantage to individual trial participants in both the treatment and control groups, respectively.8 Such a trial would require the prospective identification of patients with equal clinical candidacy for inpatient rehabilitation services followed by the random division of those patients into groups that would receive and not receive inpatient rehabilitation. Although current literature does not confirm or refute the benefit of rehabilitation, current clinical wisdom supports it.

We believe that the random withholding of services considered clinically beneficial would be hard to justify. Consequently, we sought an observational study design that could take advantage of natural variations in care provision across the nation within the large, highly integrated VHA system of care to study the effectiveness of acute postoperative inpatient rehabilitation. There are few, if any, available sources of longitudinal data in the private sector that address the benefits of alternative rehabilitation care patterns or associated long-term outcomes. Thus, we used administrative data from the VHA to determine if outcomes differ in a large population of veterans who received and did not receive rehabilitation services while still hospitalized after traumatic or dysvascular amputations.

Investigators in other clinical disciplines have used naturally occurring variation in service patterns to compare alternative treatment outcomes.9–12 With observational studies, it is essential to recognize that the decision to provide a particular treatment is generally based on a clinical assessment of the patient’s potential to benefit and service availability.13 Consequently, selection for a particular treatment pattern depends on patient- and facility-level characteristics, which may also influence outcomes. The effect of this clinical decision-making process can lead to selection bias, rendering the comparison of those who do and do not receive a pattern of care as treatment and control, respectively, noncomparable with regard to outcomes. Vogel et al14 documented the presence of selection bias in stroke rehabilitation within the VHA, and so we expected and looked for selection bias in the decision to provide rehabilitation to veterans with lower-extremity amputation. Finding such bias, we applied propensity score risk adjustment methods15 to evaluate the effects of a particular rehabilitation pattern of services among veterans with lower-extremity amputation.

The spectrum of rehabilitation services that can be provided is very wide. Within the VHA, as in the private sector, patients may or may not be referred to rehabilitation services after surgical amputation. Initial referral corresponds to entry into the rehabilitation continuum within the VHA; the referral may occur before surgical amputation, after amputation while the patient is still hospitalized, or only after the patient is discharged from the hospital. Entry into the continuum is initialized by an inpatient rehabilitation consultation and assessment. After consultation and initial assessment, patients may receive no more services, receive generalized consultative services consisting of the provision of various therapies, or be admitted onto a specialized rehabilitation bed unit.

It is essential to disentangle the effects of both structure and process when evaluating patient outcomes along the continuum of inpatient rehabilitation services received. There is substantial variability in where services occurred, when they began, and what types of rehabilitation services were delivered. We recognized that combining the multitude of rehabilitation care patterns into a single study would confound the analysis of outcomes. Based on Donabedian’s conceptualization of structure, process, and outcome,16 adapted by Hoenig et al17 for stroke rehabilitation, we developed a specific framework (the time, place, and type of services framework) as the foundation for this work to classify those patterns and to better understand the continuum of rehabilitation services received. This framework is intended to describe rehabilitation services and the integration of those services within the broader scope of the other types of health care being provided. The time, place, and type of services framework characterizes care patterns based on where, when, and what types of rehabilitation services are received. Time is measured relative to the surgical amputation date and associated hospital admission and discharge dates distinguishing among acute preoperative, acute postoperative, and postacute (posthospital discharge) phases. Place reflects setting (inpatient, outpatient, home), and type refers to the type(s) of services received. This study is the first in a series intending to look at patient outcomes according to a particular pattern of rehabilitation care. The purpose of the study was to analyze the benefits of what is referred to as the acute inpatient postoperative care pattern.

An analysis of the acute pattern is intended to address the effects of relatively early inpatient rehabilitation services received that begin after surgery and are completed while the patient is still hospitalized; this sequence of services represents the most common inpatient rehabilitation pattern received among veterans with lower-extremity amputation.18 According to the time, place, and type of services framework, time is restricted to the acute postoperative period and place to the inpatient setting. Our study objective was to determine if receipt of formal rehabilitation (either generalized consultative or admission onto a specialized rehabilitation bed unit) post-operatively while still hospitalized after surgical amputation improved patient outcomes. Patients who received this early inpatient rehabilitation pattern were compared to patients who had no evidence of inpatient rehabilitation according to 3 outcomes: (1) 1-year cumulative survival, (2) home discharge from the surgical hospitalization, and (3) prosthetic procurement within 1 year. The VHA health care system is vastly different from other systems of care. Consequently, findings must be interpreted relative to the structure and processes of care that occur within that system.

METHODS

This observational study was approved by the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, PA, the Samuel S. Stratton VAMC in Albany, NY, and the Kansas City VAMC in Kansas City, MO, institutional review boards. Methods followed guidelines reported by the Transparent Reporting of Evaluations with Non-Randomized Designs statement19 for designing and reporting evaluation studies.

Patient Selection Criteria

Patient selection criteria were applied sequentially to identify the subset of the larger amputee population that either received the acute inpatient pattern or had no evidence of inpatient rehabilitation in the first year after surgical amputation (fig 1). The larger amputee sample included all veterans from 125 VAMCs in which surgical amputation was performed with hospital discharge dates between October 1, 2002, and September 30, 2004. Because of sample selection criteria (described below), patients were included from only 105 of the original facilities. Amputations by definition were transtibial, transfemoral, or hip disarticulation as identified by the following surgical procedure codes used by Mayfield et al20: codes 84.10, 84.13 to 84.19, and 84.91. Patients were excluded if the amputation involved toes only or if there was record of a previous lower-extremity amputation within 12 months preceding the hospitalization in which the amputation of interest occurred, referred to as the index surgical stay. Records with admission dates within 24 hours of the main hospitalization discharge date were concatenated onto the index surgical stay.

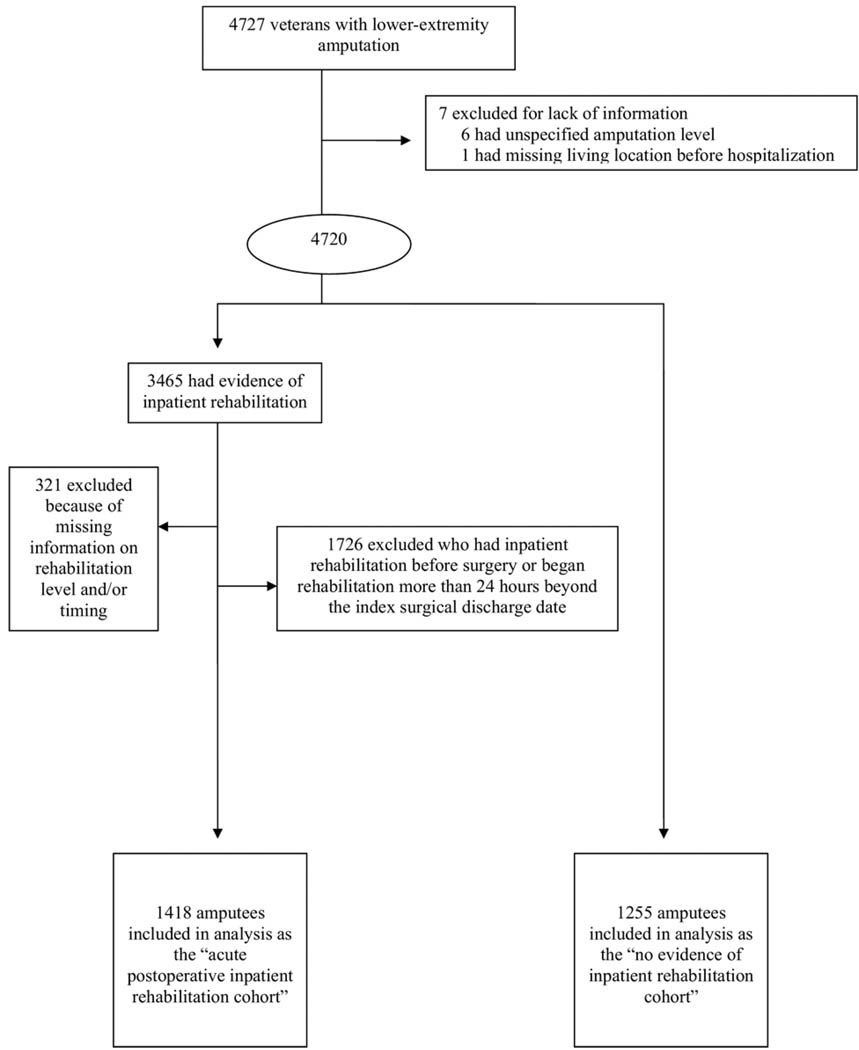

Fig 1.

Flow diagram of veterans with lower-extremity amputation included in this study.

A total of 7 patients were excluded because their records lacked information (6 had unspecified amputation level, 1 had missing living location before hospitalization). From the remaining large group (N=4720), we identified 2 cohorts: those with no evidence of rehabilitation (n=1255) and those with evidence of inpatient rehabilitation (n=3465) at some point within the first year after the amputation. Next, the acute postoperative inpatient cohort was defined from the 3465 case records. This process led to the exclusion of those patients who received inpatient rehabilitation outside the time frame defining the acute pattern. Specifically, applying criteria for defining the acute inpatient pattern as described below, the following patients were excluded: 304 patients who began rehabilitation before surgery, 206 who had rehabilitation extending beyond or beginning more than 24 hours after hospital discharge, and 1216 who received rehabilitation services in the acute postoperative period and after being discharged from the index surgical stay. Finally, we excluded 321 patients who had evidence of admission into the rehabilitation continuum but no record of a rehabilitation discharge date. We excluded these patients because we wanted to restrict our analysis to patients who experienced a rehabilitation process (with a beginning and end) rather than only a rehabilitation assessment. As a result, the acute postoperative inpatient rehabilitation cohort included 1418 lower-extremity amputees (30% of all amputees). These patients were compared with the 1255 amputees (26.5% of all amputees) in the cohort with no evidence of inpatient rehabilitation during the first postoperative year.

Database Description

Data were obtained from 9 VHA administrative databases used to track veterans’ health status and health care utilization. These databases included 4 inpatient datasets referred to as the PTF (main, procedure, bed section, surgery),21 2 outpatient care files (visit, event),22 the Beneficiary Identification Record Locator System death file,23 the National Prosthetics Patient Database,24 and the Functional Status and Outcomes Database.25 Our methods of data extraction have been described previously.26–28

Variable Definition

Patient-level characteristics included age, sex, marital status (married vs not married), living location before hospitalization (extended care, home, hospital), and clinical status. Amputation level was distinguished between transtibial and transfemoral amputation. Hip disarticulations were combined with transfemoral amputations because of too few occurrences (n=26) and because of similarities between the 2 groups. Clinical status included diagnoses that distinguished between amputation etiologies26,29 and comorbidities, 30,31 which were obtained by merging diagnostic codes from outpatient files 3 months before hospital admission to the main and bed section files up to the surgical date. We merged the codes to capture any conditions known to be present prior to hospitalization that might not have been coded during the index surgical stay. Length of time (in days) from hospital admission to the surgery, intensive care unit admission, and total number of bed sections in which treatment occurred approximated baseline complexity. Selected procedures were classified to approximate the extent and type of organ pathology.27

Facility-level characteristics included geographic region (Veterans Integrated Service Networks mapped into Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Service regions: Northeast, Southeast, Midwest, South Central, and Pacific Mountain), hospital bed size (≤126, 127–244, 245–362, and >362), and the presence of an accredited specialized rehabilitation bed unit within the VAMC where the amputation was performed. A year variable indicating fiscal year of treatment was also added to adjust for any changes in practice patterns over time that might have influenced care.

Specification of the “Acute Inpatient Postoperative Pattern”

Typically, once patients are admitted to the rehabilitation continuum, rehabilitation professionals assess the patient’s functional status over a span of up to 3 days to evaluate their potential for rehabilitation and to develop a care plan. This care plan may include the following: (1) no further treatment beyond the initial assessment, (2) continued generalized consultative rehabilitation, (3) outpatient rehabilitation, (4) home rehabilitation, or (5) admission onto a specialized rehabilitation bed unit. Once the patient has either met the rehabilitation goals or achieved maximum potential, the patient is discharged from the continuum. Patients selected for this study had to meet the definition for the acute postoperative pattern. Consequently, the intervention time period and place were restricted to the acute postoperative inpatient period, represented by rehabilitation episodes that occurred between the amputation and hospital discharge dates.

The treatment group consisted of those patients with evidence of acute postoperative inpatient rehabilitation, hereafter referred to as inpatient rehabilitation. The control group included those with no evidence of inpatient rehabilitation, hereafter referred to as no inpatient rehabilitation. To be in the inpatient rehabilitation group, there needed to be distinct dates of admission and discharge from the continuum in the Functional Status and Outcomes Database indicating a beginning and ending of inpatient rehabilitation care. There also needed to be evidence of generalized consultative care with or without treatment on a specialized rehabilitation bed unit. Generalized consultative care consisted of a program of therapy provided by the interdisciplinary rehabilitation team while patients remained in medical or other types of nonrehabilitation surgical beds. Specialized rehabilitation bed unit care included patients who were admitted for intensive rehabilitation (ie, receiving ≥3h/d of therapy).

Outcome Measures

Patients were followed from the surgical date to the 1-year amputation anniversary. Outcomes included home discharge from the hospital, prosthetic limb procurement within a year of surgery and 1-year survival. The PTF main and Beneficiary Identification Record Locator System databases were used to acquire mortality information, and methods have been described previously.26

Home discharge from the index surgical stay compared with other (hospital, extended care, death, other) was determined by the PTF main file, and prosthesis procurement was determined from the National Prosthetics Patient Database. Because our objective was to follow patients up to the 1-year amputation anniversary, patients still hospitalized at that time had their discharge disposition categorized as hospital regardless of what was indicated in their PTF main record.

The analysis evaluated associations between the receipt of inpatient rehabilitation and the 3 outcomes relative to a comparative group not receiving inpatient rehabilitation as described above.

Statistical Methods

Patient- and facility-level baseline characteristics

The statistical procedure emulates a randomized controlled trial by treatment groups through propensity adjustment.15 Baseline analyses summarized the degree to which patient- and facility-level selection bias influenced the likelihood of receiving inpatient rehabilitation treatment relative to receiving no inpatient rehabilitation, which served as the control. Significance testing was conducted through chi-square and Student t tests, with patients as the unit of analysis; P values were 2-sided, with statistical significance at P less than .05.

Propensity score risk adjustment

In observational studies, the effects of selection bias may be minimized by identifying patient- and facility-level variables that influence treatment selection and then removing their effects through statistical adjustment.15 Although such adjustment can only minimize the effects of observed variables, the effect of unobserved variables will be reduced to the extent to which they are correlated with the observed variables.32 We developed a propensity score for the pairwise treatment comparison through a multivariable logistic regression model with the receipt versus nonreceipt of rehabilitation treatment as the dependent variable.

This propensity model was maximally saturated in efforts to reduce as much selection bias as possible. Consequently, we included all available patient- and facility-level variables in the VHA databases that the clinician authors (M.G.S., B.E.B., D.M.R.) believed could possibly influence a patient’s selection for inpatient rehabilitation or outcomes. The treatment and control comparison was regressed on 54 patient-level and 8 facility-level variables (see variable definitions above). We tested the significance of statistical interactions and squared and cubic forms of continuous variables. Overall model performance was summarized by the c statistic measuring model discrimination.33 The resulting propensity scores represent the conditional probability of receiving rehabilitation, given status across the explanatory variables, and are applied to reduce treatment selection bias and increase precision in calculating treatment effects.15

The propensity scores were estimated for each veteran from the regression model, making it possible to stratify patients into equal-sized quintiles.34 Stratification by quintile has been shown empirically to remove more than 90% of the bias resulting from the variables used to create the score.15 Rather than applying the propensity score as a continuous measure, we divided the score into quintiles to accommodate any non-linearity present in the propensity score. Each quintile contained veterans with a discrete range in the predicted probability of receiving rehabilitation and was required to have at least 5 patients in the treatment groups to ensure sufficient overlap and common support between the groups.35 The achievement of common support refers to the presence of sufficient overlap between the treatment and control groups to compare outcomes once the propensity quintiles were formed. We obtained box-plots to compare the distributions of propensity between the no evidence of inpatient rehabilitation and the acute inpatient rehabilitation groups.

Testing for balance

The testing of balance is a way of measuring the success of the propensity methods in adjusting for each of the particular patient- and facility-level characteristics shown to influence treatment decisions. Balance was evaluated by determining the degree to which the acute inpatient rehabilitation and no inpatient rehabilitation groups were similar with respect to key variables before and after adjustment by the propensity quintiles. We addressed the degree to which statistical control for propensity score quintiles removed any differences between the distributions of observed variables comparing the treatment to control group through multivariable models. In these models (multiple linear or logistic regression, depending on variable structure), the dependent variables were patient- and facility-level characteristics. Treatment group (acute inpatient rehabilitation vs no evidence of inpatient rehabilitation) was the primary predicting variable. The magnitude of selection bias reduction associated with individual variables was determined by comparing the slope coefficient or OR of a treatment group before and after adjusting for the propensity quintiles. If the treatment group difference was no longer statistically significant (P<.05) when the propensity score quintiles were added to the regression model, the propensity adjustment was considered adequate to control for group differences associated with the explanatory variable. If the P value remained significant, then adjustment for propensity score quintile alone would not adequately control for imbalance between the groups, and that variable would need to be included as a predictor in the final outcome models.34,36

Modeling outcome differences

We compared inpatient rehabilitation to no inpatient rehabilitation using appropriate propensity score quintiles and any nonbalanced covariates to adjust for differences between the treatment and control groups. Separate multiple logistic regression analyses were performed for each outcome (treatment coded as “yes” or “no”). ORs and 95% CIs were used as measures of clinical effect size because they retain their validity when sampling is done on the basis of outcome status. The appropriate propensity score quintiles (coded as 4df dummy categories) were included in the logistic regression model to minimize selection bias.

All analyses were performed using SAS.a

RESULTS

Patient- and Facility-Level Baseline Characteristics

Nearly three quarters (73.3% [n=3465]) of amputees received inpatient rehabilitation, 40.9% (n=2673) of whom met our selection criteria for acute postoperative inpatient rehabilitation. Of these 2673, 99.2% were men, average age was 67.4 years (median, 69y), and the majority had transtibial amputations (55.1%). The most common etiologies were problems with peripheral circulation (85.8%) and diabetes mellitus type 2 (64.9%). Trauma was present in only 13.8% of the patients. The average hospital stay was 32.1 days (median, 19d), and patients transferred to an average of 2.5 bed sections (median, 2) during their acute stay, with 7 patients still hospitalized at the first amputation anniversary. For patients receiving inpatient rehabilitation, average treatment lasted 12.5 days (median, 7d).

Table 1 shows baseline characteristics of the treatment and control groups. Over half (53% [n=1418]) of our sample received inpatient rehabilitation; of these, 80% received generalized consultative care only, and 20% were admitted onto a specialized rehabilitation bed unit. Table 1 shows that there are significant differences in patients between treatment groups in factors that may be related to the outcomes of interest. These findings underscore the need to statistically reduce selection bias when addressing treatment-related outcome differences. There were also statistically significant facility-level differences. Those patients whose surgical amputations occurred in hospitals with a smaller number of beds and in the midwest region of the United States were less likely to receive inpatient rehabilitation than those patients treated in larger hospitals and in other regions of the country.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics According to the Receipt of Acute Postoperative Inpatient Rehabilitation Services

| Characteristics | Received Acute Postoperative Inpatient Rehabilitation (n=1418) |

No Evidence of Inpatient Rehabilitation (n=1255) |

|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||

| Average age (y) | 67.2 (35–87) | 67.7 (26–95) |

| Sex (male) | 1406 (99.2) | 1245 (99.2) |

| Marital status (not married) | 765 (54.0) | 706 (56.3) |

| Living location before hospitalization‡ |

||

| Extended care | 88 (6.2) | 206 (16.4) |

| Home | 1294 (91.3) | 1005 (80.1) |

| Hospital | 36 (2.5) | 44 (3.5) |

| Transtibial amputation level‡ | 836 (59.0) | 637 (50.8) |

| Contributing etiologies | ||

| Previous amputation complication† |

131 (9.2) | 94 (7.5) |

| Systemic sepsis‡ | 145 (10.2) | 197 (15.7) |

| Comorbidities | ||

| Fluid and electrolyte disorders* |

300 (21.2) | 317 (25.3) |

| Hypertension‡ | 910 (64.2) | 687 (54.7) |

| Paralysis† | 64 (4.5) | 89 (7.1) |

| Renal failure* | 238 (16.8) | 256 (20.4) |

| Time from admission to surgery (d) |

8.3 | 13.8 |

| Procedures | ||

| Active pulmonary pathology* |

16 (1.1) | 29 (2.3) |

| Ongoing active cardiac pathology* |

177 (12.5) | 196 (15.6) |

| Serious nutritional compromise† |

63 (4.4) | 97 (7.7) |

| Severe renal disease† | 115 (8.1) | 146 (11.6) |

| ICU admission‡ | 534 (37.7) | 612 (48.8) |

| Average no. of bed sections (range)* |

2.6 (1–18) | 2.5 (1–18) |

NOTE. Values are n (range) or n (%). Only statistically significant amputation etiologies, comorbidities, and procedures are shown; region (5 categories) and total hospital bed size (4 categories) were both statistically significant P<.01 (data not shown).

Abbreviation: ICU, intensive care unit.

P<.05.

P<.01.

P<.001.

Propensity Risk-Adjustment Models

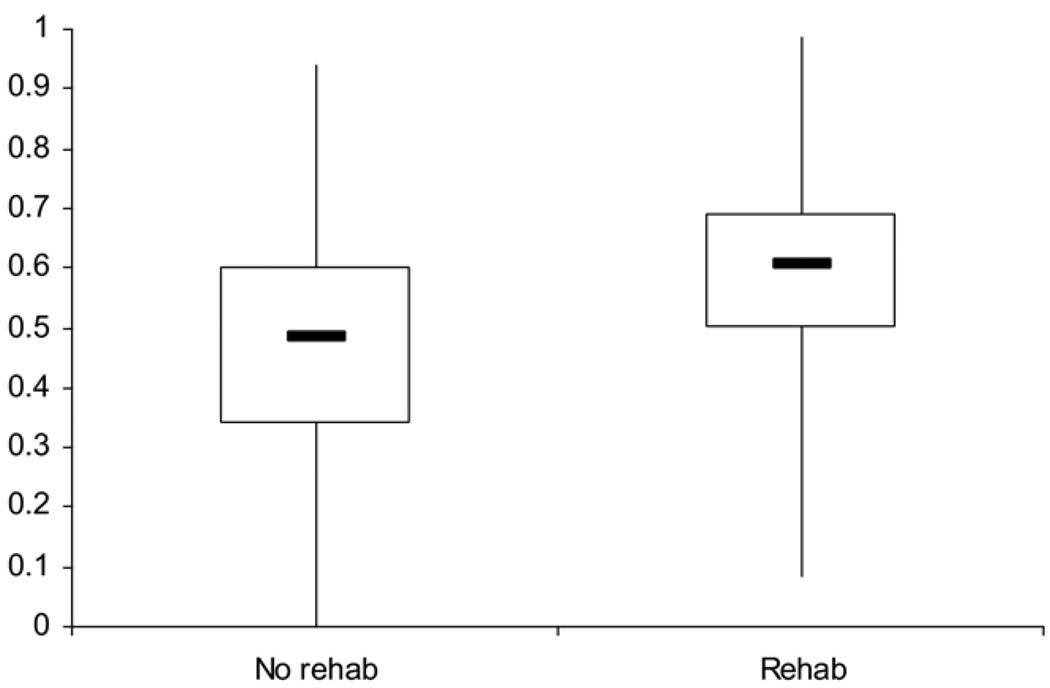

In the model comparing inpatient rehabilitation to no inpatient rehabilitation, the c statistic was .70, and the propensity scores ranged from 2.09×10−10 to .99 (table 2). The average propensity score for patients who received inpatient rehabilitation was .59 (95% CI, .31–.80) and .47 (95% CI, .18–.72) for those who did not.

Table 2.

Distribution of Select Covariates* by Propensity Score Quintile According to Receipt of Acute Postoperative Inpatient Rehabilitation

| Covariates | 1 (2.09×10−10−0.37) | 2 (0.38–0.50) | 3 (0.51–0.59) | 4 (0.60–0.67) | 5 (0.68–0.99) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of patients | |||||

| No evidence of inpatient rehabilitation | 398 | 292 | 244 | 189 | 132 |

| Inpatient rehabilitation | 136 | 243 | 291 | 346 | 402 |

| Living location before hospitalization (home) (%) | |||||

| No evidence of inpatient rehabilitation | 23.9 | 36.6 | 44.3 | 45.0 | 56.8 |

| Inpatient rehabilitation | 25.7 | 37.0 | 44.0 | 46.2 | 55.5 |

| Living location before hospitalization (hospital) (%) | |||||

| No evidence of inpatient rehabilitation | 35.4 | 50.3 | 53.7 | 55.0 | 42.4 |

| Inpatient rehabilitation | 35.3 | 52.7 | 52.9 | 53.8 | 44.3 |

| Amputation level (transtibial) (%) | |||||

| No evidence of inpatient rehabilitation | 36.7 | 52.4 | 50.0 | 66.1 | 68.9 |

| Inpatient rehabilitation | 43.4 | 46.5 | 58.4 | 59.0 | 72.1 |

| Length of stay from admission to surgery (average) | |||||

| No evidence of inpatient rehabilitation | 25.8 | 9.8 | 8.5 | 6.1 | 7.6 |

| Inpatient rehabilitation | 15.1 | 9.5 | 7.3 | 6.8 | 7.1 |

| Systemic sepsis (%) | |||||

| No evidence of inpatient rehabilitation | 25.9 | 16.1 | 10.7 | 6.9 | 6.1 |

| Inpatient rehabilitation | 29.4 | 14.8 | 8.9 | 5.5 | 6.0 |

| Hypertension (%) | |||||

| No evidence of inpatient rehabilitation | 42.0 | 48.3 | 59.8 | 69.3 | 77.3 |

| Inpatient rehabilitation | 39.7 | 49.4 | 60.1 | 67.9 | 81.1 |

| Paralysis (%) | |||||

| No evidence of inpatient rehabilitation | 10.3 | 8.6 | 6.6 | 2.1 | 2.3 |

| Inpatient rehabilitation | 9.6 | 10.7 | 3.8 | 2.9 | 1.1 |

| ICU admission | |||||

| No evidence of inpatient rehabilitation | 70.4 | 53.1 | 38.5 | 21.2 | 32.6 |

| Inpatient rehabilitation | 64.7 | 57.6 | 39.9 | 28.9 | 22.4 |

NOTE. Facility-level characteristics including number of bed sections, region, and hospital bed size that were statistically significant in the propensity model were not included in the table because of space.

Abbreviation: ICU, intensive care unit.

Covariates presented that were considered either clinically important or that were statistically significant in the propensity model.

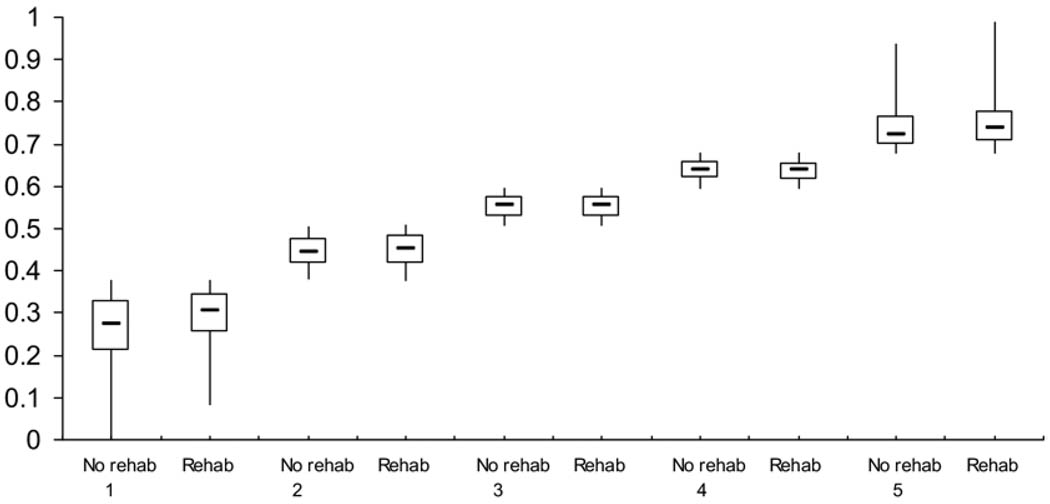

The boxplot in figure 2 shows substantial differences in the distribution of propensity comparing the acute inpatient rehabilitation treatment group to the no evidence of rehabilitation group. In contrast, the boxplot stratified by propensity quintile (fig 3) shows extensive overlap between these groups. There are few individuals in the groups outside the areas of overlap. This finding suggests sufficient overlap in the propensity score distribution between those patients receiving and not receiving inpatient rehabilitation to permit statistical comparisons between the groups. The number of veterans in the acute inpatient and no evidence of inpatient rehabilitation groups in each propensity strata was sufficient to ensure common support (see table 2).

Fig 2.

A nonparametric illustration of the overall distribution of propensity for treatment comparing the no evidence of rehabilitation group to the acute rehabilitation group. The overall distributions are shown through a boxplot comparing those who received and did not receive inpatient rehabilitation. The upper inner and lower horizontal lines are the 75th, 50th, and 25th percentiles, respectively. The lower and upper tips of the vertical lines represent the minimum and maximum values of propensity, respectively.

Fig 3.

A nonparametric illustration of the distribution of propensity for treatment comparing the no evidence of rehabilitation group to the acute rehabilitation group stratified by propensity quintile. The distributions are shown through a boxplot comparing those who received and did not receive inpatient rehabilitation by propensity quintile. The upper inner and lower horizontal lines are the 75th, 50th, and 25th percentiles, respectively. The lower and upper tips of the vertical lines represent the minimum and maximum values of propensity, respectively.

Test for Balance

Treatment group differences were substantially reduced within each of the propensity score quintiles. For example, a similarly high percentage of patients in the fifth quintile associated with the highest likelihood of receiving inpatient rehabilitation were admitted to the hospital from home in both treatment groups. In contrast, a similarly low percentage of patients in the first quintile associated with the lowest likelihood of receiving inpatient rehabilitation were admitted to the hospital from home in both treatment groups.

All variables with unadjusted statistically significant treatment group differences became balanced when selection criteria were applied for the acute inpatient pattern and the propensity score quintiles were added to the individual models.

Table 3 demonstrates the degree to which the propensity score quintiles removed statistical differences between the distributions of observed variables comparing the treatment to control group. All of the previously significant associations became nonsignificant after the propensity scores were added. For example, patients who received acute inpatient rehabilitation compared to those who did not were 1.05 times more likely to be admitted to the hospital from home rather than from long-term care (95% CI, 1.03–1.08; P<.001). After propensity scores were added to the logistic regression model, there was no longer a statistical difference between groups (OR= 1; 95% CI, .98–1.03; P=.85).

Table 3.

Illustration of Balance for Key Clinical Characteristics Before and After the Application of Propensity Score Quintiles

| Covariate | Before Propensity Adjustment OR (95% CI) | After Propensity Adjustment OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Admission from home vs extended care | 1.05 (1.03–1.08), P=.001 | 1.00 (0.98–1.03), P=.85 |

| Admission from hospital vs extended care | 1.02 (0.99–1.05), P=.15 | 1.00 (0.98–1.03), P=.85 |

| Transtibial vs transfemoral | 1.06 (1.03–1.08), P<.001 | 1.00 (0.98–1.03), P=.72 |

| Paralysis | 0.92 (0.87–0.98), P=.005 | 0.99 (0.93–1.05), P=.73 |

| Systemic sepsis | 0.92 (0.89–0.96), P<.001 | 0.99 (0.95–1.04), P=.78 |

| Hypertension | 1.07 (1.04–1.10), P<.001 | 1.00 (0.97–1.03), P=.88 |

| ICU admission | 0.93 (0.90–0.95), P<.001 | 1.00 (0.97–1.03), P=.88 |

NOTE. Values are ORs and CIs. ORs, CIs, and P values associated with treatment group in models predicting key baseline clinical characteristics before and after adjustment for the 5 propensity score quintiles. The treatment variable is structured such that not receiving inpatient rehabilitation forms the reference group.

Abbreviation: ICU, intensive care unit.

Outcome Differences

Approximately 73.1% of patients who received inpatient rehabilitation compared to only 44.5% who did not were discharged home. Table 4 shows unadjusted outcome advantages for survival and prosthesis procurement. After propensity score risk adjustment, patients who received inpatient rehabilitation remained 1.51 times more likely to survive (95% CI, 1.26–1.8) and 2.58 times more likely to be discharged home (95% CI, 2.17–3.06) compared to patients with no inpatient rehabilitation (see table 4). There was no statistically significant difference in prosthetic limb procurement between the groups.

Table 4.

Frequency and Adjusted Outcomes Associated With the Receipt of Acute Postoperative Inpatient Rehabilitation Services

| Outcome | n (%) | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inpatient rehabilitation | |||

| 1-year survival | 1087 (76.7)* | 1.94 (1.64–2.30)* | 1.51 (1.26–1.80)* |

| Home discharge | 1036 (73.1)* | 3.39 (2.88–3.98)* | 2.58 (2.17–3.06)* |

| Prescription of a prosthetic limb | 315 (22.2)† | 1.45 (1.20–1.77)* | 1.18 (0.96–1.45) |

| No inpatient rehabilitation | |||

| 1-year survival | 789 (62.9) | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Home discharge | 558 (44.5) | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Prescription of a prosthetic limb | 206 (16.4) | 1.0 | 1.0 |

P<.001.

P<.01.

DISCUSSION

In this observational study involving veterans with lower-extremity amputation for largely nontraumatic etiologies, we found that acute postoperative inpatient rehabilitation was associated with improved outcomes. After adjusting for multiple factors that could confound comparisons among groups, inpatient rehabilitation patients were more likely to be discharged home and to survive 1 year postoperatively compared to those patients with no inpatient rehabilitation. The definition of acute rehabilitation applied in our study was broad. It included an inpatient program provided by an interdisciplinary rehabilitation team either through generalized consultation or on a specialized rehabilitation bed unit while veterans were still hospitalized for their amputations. Thus, this approach to studying outcomes differs from most reports that tend to be limited to the small proportion of the amputee population (9.6%–16%) that receives treatment within a designated rehabilitation bed either at an IRF in the private sector or on a specialized rehabilitation bed unit.6,7,37

It appears that the commonly articulated goals of acute postoperative rehabilitation to help patients with amputations regain sufficient mobility to return home are being realized. The positive influence on 1-year survival is consistent with findings for stroke rehabilitation.38,39 Improvements in mobility and general functioning could be enhancing survival among those patients with new amputations and making it possible for larger proportions of patients to return home from the hospital. We were unable to directly test mobility and other types of functional status as outcomes because that information is not collected on those who do not enter the rehabilitation continuum.

We recognize that RCTs remain the criterion standard for demonstrating efficacy. Observational studies intended to simulate trials can lead to positive findings later proven spurious through RCTs.40,41 However, such observational, naturalistic studies have supported effectiveness or lack of effectiveness in a variety of health care interventions, thus justifying RCTs that subsequently confirmed their findings.10–12,42,43 RCTs cannot be undertaken for all interventions in which benefit is unknown, particularly when strong beliefs about benefit make randomization difficult. Conversely, the results of observational studies can support effectiveness but must be interpreted cautiously.44 Although we adjusted for a rich set of patient- and facility-level factors, propensity scores can remove bias due to treatment selection differences resulting from unmeasured confounding factors only to the extent that the unmeasured and measured factors are correlated. Neither the magnitude of this correlation nor the degree to which selection bias is reduced can be completely known. Recognizing that unobserved covariates can potentially cause inaccurate effect size estimations, we applied all available patient- and facility-level information in our databases believed to have any potential of affecting the selection of patients for inpatient rehabilitation or outcomes in efforts to maximally reduce selection bias.34

A major advantage of our study was the ability to use VHA centralized data and organizational structure to obtain system-wide data for acute care and inpatient rehabilitation. The development of integrated care structures that cover interdisciplinary rehabilitation after acute care for disabling conditions is becoming a priority worldwide.45 The VHA has moved to the forefront of developing such integrated systems of health care in the United States.46–48 In addition to multifaceted electronic medical record data capturing and monitoring systems, the VHA mandates that rehabilitation potential be evaluated in the majority of amputees and has defined a continuum of rehabilitation services.49 Our results suggest that entrance into the rehabilitation continuum with receipt of some form of formal rehabilitation (generalized consultative or admission onto a specialized rehabilitation bed unit) during the inpatient postoperative period is effective. Most previous studies, which are limited to IRFs, view rehabilitation as being a separate episode outside the acute hospitalization (postacute care). In our study, all initial rehabilitation assessments occurred while patients were still being treated within nonrehabilitation bed sections within the acute hospital. Moreover, all rehabilitation treatment occurred during and within the acute hospitalization in which the amputation occurred.

Private sector data on rehabilitation (ie, collected by Medicare) are more limited than data collected by the VHA. Documentation of care is fragmented, and episodes are poorly linked. In contrast to the VHA, most data systems in the U.S. private sector do not map into one another. Although amputees in private sector hospitals may be seen by rehabilitation consultants, there is no administrative data source that tracks those services. Information is captured only on the small proportion of patients (<25%) who receive care in IRFs.6,7,37 Without a data source comparable to the rehabilitation continuum database in the VHA, it would be impossible to replicate this type of study in the private sector or in other nations. The private sector in the United States and health systems around the world deal with many of the same issues of clinical decision-making and rehabilitation after amputation as does the VHA. Consequently, our findings could have implications to the care of nonveterans and amputees in other nations, but the findings will need to be interpreted cautiously.

In 2001 and 2004, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Service published final rules implementing a new prospective payment system and policy changes regarding the case-mix diagnostic criteria used to determine which private sector programs were eligible to receive reimbursement as an IRF.50,51 From 2004 to 2006, there was an estimated 19.2% decline in the overall IRF caseload and a 13.5% reduction in the number of lower-extremity amputees treated.52 Moreover, substantial reductions in median length of stay for the general population treated in IRFs have been shown to be associated with increases in mortality at 80- to 180-day postdischarge follow-up.53 These results, coupled with our VHA-related findings, suggest that ongoing reductions in rehabilitation availability could have tangible and detrimental effects.

Study Limitations

There were some limitations in our study. Although there are clear differences in the structure and processes of services in the VHA and private sector health care systems, there is evidence that changes in the 1990s in the delivery of VHA health care are leading to reductions in variability across sectors.54 Clearly, however, outcomes might differ among women and nonveterans. Although recognizing differences in the populations treated, studies on veterans who tend to be poorer and of ethnic minorities could provide insight on the needs of some of the most vulnerable subgroups in the private sector. However, racial characteristics were not included in our analyses because of a great deal of missing information. Finally, it is important to recognize that, although the acute postoperative inpatient rehabilitation pattern studied here was the most common, it includes less than half the veterans who ultimately received some form of inpatient rehabilitation but who did not receive the acute pattern.

CONCLUSIONS

We offer the time, place, and type of services framework as a way to classify and understand the complexity of services received. This model takes into account the rehabilitation services received along a continuum. Moreover, the rehabilitation continuum is one of many interlocking continuums that operate in defining overall patient care. With this broad view, it becomes important to address how rehabilitation services relate temporally to the provision of other types of medical and surgical services. We cannot necessarily assume that other rehabilitation service patterns will have the same effects on outcomes as the acute inpatient pattern studied here. Future efforts will need to be directed at assessing the influence of a wide variety of rehabilitation care patterns on outcomes. The ultimate goal will be to determine the optimal integration of rehabilitation within the larger fabric of health care services.

Our study sheds light on the effectiveness of acute postoperative inpatient rehabilitation after amputation. Such findings are important in an era when the availability of such services may become increasingly restricted due to cost containment efforts in the United States and around the world. Because of the need to identify cohorts of patients that received sufficiently homogeneous rehabilitation treatments, this study was limited to those who received the acute postoperative inpatient pattern. The effectiveness of rehabilitation among the 43.5% of the amputee population who had some form of inpatient rehabilitation but who did not receive the acute pattern will need to be studied in the future. It will also be important to determine if there are incremental benefits of receiving rehabilitation services on an interdisciplinary, comprehensive, specialized, rehabilitation bed unit compared with receiving generalized consultative services.

In addition to addressing the associations of outcomes with other rehabilitative care patterns and for other rehabilitation diagnoses, future studies will also need to include the effects of home care and outpatient rehabilitation services. Our findings suggesting the overall benefit of rehabilitation support the development of RCTs to search for the individual treatment components most associated with better outcomes.

Acknowledgments

The opinions and conclusions of the authors are not necessarily those of the sponsoring agencies.

We thank Janice Duglas and Sharon Jayne, BSEd, who provided support in the preparation of the manuscript, and Clifford Marshall, MS, who developed and guided the group in applications of the Functional Status and Outcomes Database data.

Supported by the National Center for Medical Rehabilitation Research National Institutes of Health (grant no. RO1-HD042588); and resources and the use of facilities at the Samuel S. Stratton Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Albany, NY, and the Kansas City Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Kansas City, MO.

List of Abbreviations

- CI

confidence interval

- IRF

inpatient rehabilitation facility

- OR

odds ratio

- PTF

Patient Treatment File

- RCT

randomized controlled trial

- VAMC

Veterans Affairs Medical Center

- VHA

Veterans Health Administration

Footnotes

No commercial party having a direct financial interest in the results of the research supporting this article has or will confer a benefit on the authors or on any organization with which the authors are associated.

Supplier

a. Version 9.1; SAS Inc, 100 SAS Campus Dr, Cary, NC 27513-2414.

References

- 1.Mayfield JA, Reiber GE, Maynard C, Czerniecki JM, Caps MT, Sangeorzan BJ. Trends in lower limb amputation in the Veterans Health Administration, 1989–1998. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2000;37:23–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wrobel JS, Mayfield JA, Reiber GE. Geographic variation of lower-extremity major amputation in individuals with and without diabetes in the Medicare population. Diabetes Care. 2001;24:860–864. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.5.860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cumming JC, Barr S, Howe TE. Prosthetic rehabilitation for older dysvascular people following a unilateral transfemoral amputation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(4) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005260.pub2. CD005260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murray PK, Singer M, Dawson NV, Thomas CL, Cebul RD. Outcomes of rehabilitation services for nursing home residents. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2003;84:1129–1136. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(03)00149-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pezzin LE, Dillingham TR, MacKenzie EJ. Rehabilitation and the long-term outcomes of persons with trauma-related amputations. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2000;81(3):292–300. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(00)90074-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dillingham TR, Pezzin LE, Mackenzie EJ. Discharge destination after dysvascular lower-limb amputations. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2003;84:1662–1668. doi: 10.1053/s0003-9993(03)00291-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dillingham TR, Pezzin LE, MacKenzie EJ. Incidence, acute care length of stay, and discharge to rehabilitation of traumatic amputee patients: an epidemiologic study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1998;79:279–287. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(98)90007-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.London AJ. The moral foundations of equipoise and its role in international research. Am J Bioethics. 2006;6:48–51. doi: 10.1080/15265160600755599. discussion W42-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barnett TE, Chumbler NR, Vogel WB, Beyth RJ, Qin H, Kobb R. The effectiveness of a care coordination home telehealth program for veterans with diabetes mellitus: a 2-year follow-up. Am J Manag Care. 2006;12:467–474. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Connors AF, Jr, Speroff T, Dawson NV, et al. The effectiveness of right heart catheterization in the initial care of critically ill patients. SUPPORT Investigators. JAMA. 1996;276:889–897. doi: 10.1001/jama.276.11.889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Foster EM. Propensity score matching: an illustrative analysis of dose response. Med Care. 2003;41:1183–1192. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000089629.62884.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang IC, Frangakis C, Dominici F, Diette GB, Wu AW. Application of a propensity score approach for risk adjustment in profiling multiple physician groups on asthma care. Health Serv Res. 2005;40:253–278. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00352.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosenbaum PR. What are observational studies? Springer series in statistics: observational studies. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vogel WB, Rittman M, Bradshaw P, et al. Outcomes from stroke rehabilitation in Veterans Affairs rehabilitation units: detecting and correcting for selection bias. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2002;39:367–383. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB. The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika. 1983;70:41–55. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Donabedian A. Evaluating the quality of medical care. Milbank Mem Fund Q. 1966;44:166–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoenig H, Sloane R, Horner RD, Zolkewitz M, Duncan PW, Hamilton BB. A taxonomy for classification of stroke rehabilitation services. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2000;81:853–862. doi: 10.1053/apmr.2000.5569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Prvu-Bettger JA, Bates B, Kwong PL, Kurichi JE, Bidelspach DE, Stineman MG. Poster 49: when is inpatient rehabilitation delivered to veterans with a lower-extremity amputation? Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2007;88(10):e19. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Des Jarlais DC, Lyles C, Crepaz N. TREND Group. Improving the reporting quality of nonrandomized evaluations of behavioral and public health interventions: the TREND statement. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:361–366. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.3.361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mayfield JA, Reiber GE, Maynard C, Czerniecki JM, Caps MT, Sangeorzan BJ. Survival following lower-limb amputation in a veteran population. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2001;38:341–345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hines EJ. VIReC Research User Guide: FY2000 VHA Medical SAS Inpatient Datasets. Hines: Veterans Affairs Information Resource Center; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hines EJ. VIReC Research User Guide: FY2000 VHA Medical SAS Outpatient Datasets. Hines: Veterans Affairs Information Resource Center; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kubal JD, Webber S, Cooper DC, Waight S, Hynes DM. A primer on US mortality databases used in health services research. VIReC Insights. 2000;5:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pape T, Maciejewski M, Reiber G. The national prosthetics patient database (NPPD): a primary resource for nationwide VA durable medical equipment data. Hines: Veterans Affairs Information Resource Center; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 25.VHA Office of Information. [Accessed June 5, 2008];VHA corporate databases monograph. 2006 Available at: http://www.virec.research.va.gov/References/links/VHACorporateDatabaseMonograph2006Final.pdf.

- 26.Bates B, Stineman MG, Reker D, Kurichi JE, Kwong FP. Risk factors associated with mortality in a male veteran population following transtibial or transfemoral amputation. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2006;43:917–928. doi: 10.1682/jrrd.2006.03.0030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kurichi JE, Kwong PL, Reker DM, Bates BE, Marshall CR, Stineman MG. Clinical factors associated with prescription of a prosthetic limb in elderly veterans. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55:900–906. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01187.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kurichi JE, Stineman MG, Kwong PL, Bates BE, Reker DM. Assessing and using comorbidity measures in elderly veterans with lower extremity amputations. Gerontology. 2007;53:255–259. doi: 10.1159/000101703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.American Medical Association. International classification of diseases, 9th rev. Los Angeles: AMA Pr; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Comorbidity Software (ver 3.1) Rockville: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2005. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, Coffey RM. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998;36:8–27. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199801000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhou Z, Lan P. Discussion of statistical and regulatory issues with the application of propensity score analysis to nonrandomized medical device clinical studies. J Biopharm Stat. 2007;17:25–27. doi: 10.1080/10543400601044691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hanley JA, McNeil BJ. The meaning and use of the area under a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. Radiology. 1982;143:29–36. doi: 10.1148/radiology.143.1.7063747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.D’Agostino RB., Jr Propensity score methods for bias reduction in the comparison of a treatment to a non-randomized control group. Stat Med. 1998;17:2265–2281. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19981015)17:19<2265::aid-sim918>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dehejia RH, Wahba S. Causal effects in nonexperimental studies: reevaluating the evaluation of training programs. J Am Stat Assoc. 1999;94:1053–1062. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rubin D, Thomas N. Combining propensity score matching with additional adjustments for prognostic covariates. J Am Stat Assoc. 2000;95:573–585. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dillingham TR, Pezzin LE. Postacute care services use for dysvascular amputees: a population-based study of Massachusetts. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;84:147–152. doi: 10.1097/01.phm.0000154899.49528.05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Langhorne P, Duncan P. Does the organization of postacute stroke care really matter? Stroke. 2001;32:268–274. doi: 10.1161/01.str.32.1.268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stroke Unit Trialists’ Collaboration. Collaborative systematic review of the randomised trials of organised inpatient (stroke unit) care after stroke. BMJ. 1997;314:1151–1159. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cameron E, Pauling L. Supplemental ascorbate in the supportive treatment of cancer: prolongation of survival times in terminal human cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1976;73:3685–3689. doi: 10.1073/pnas.73.10.3685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Moertel CG, Fleming TR, Creagan ET, Rubin J, O’Connell MJ, Ames MM. High-dose vitamin C versus placebo in the treatment of patients with advanced cancer who have had no prior chemotherapy. A randomized double-blind comparison. N Engl J Med. 1985;312:137–141. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198501173120301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kramer AM, Steiner JF, Schlenker RE, et al. Outcomes and costs after hip fracture and stroke. A comparison of rehabilitation settings. JAMA. 1997;277:396–404. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Leibowitz AB. Who benefits from pulmonary artery catheterization? Crit Care Med. 2003;31:2805–2806. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000098850.60438.D4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stukel TA, Fisher ES, Wennberg DE, Alter DA, Gottlieb DJ, Vermeulen MJ. Analysis of observational studies in the presence of treatment selection bias: effects of invasive cardiac management on AMI survival using propensity score and instrumental variable methods. JAMA. 2007;297:278–285. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.3.278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fuchs H. [Services and benefits for medical rehabilitation and integrated health care]. [German] Rehabilitation (Stuttg) 2004;43:325–334. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-828495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Haugh R. Reinventing the VA. Civilian providers find valuable lessons in a once-maligned health care system. Hosp Health Netw. 2003;77:50–52. 55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jha AK, Perlin JB, Kizer KW, Dudley RA. Effect of the transformation of the Veterans Affairs Health Care System on the quality of care. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2218–2227. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa021899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Perlin JB, Kolodner RM, Roswell RH. The Veterans Health Administration: quality, value, accountability, and information as transforming strategies for patient-centered care. Am J Manag Care. 2004;10:828–836. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Office of Quality and Performance (10Q) FY 2005 VHA executive career field network director performance measurement system and JCAHO hospital core measures (Technical manual) Washington (DC): Veterans Health Administration; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), HHS. Medicare program: prospective payment system for inpatient rehabilitation facilities. Final rule. Fed Regist. 2001:41315–41430. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), HHS. Medicare program: changes to the criteria for being classified as an inpatient rehabilitation facility. Final rule. Fed Regist. 2004:25752–25776. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.The Moran Co. [Accessed June 5, 2008.];Utilization trends in inpatient rehabilitation: update through Q II 2006. Available at: http://www.aha.org/aha/content/2006/pdf/2006septmoranreport.pdf.

- 53.Ottenbacher KJ, Smith PM, Illig SB, Linn RT, Ostir GV, Granger CV. Trends in length of stay, living setting, functional outcome, and mortality following medical rehabilitation. JAMA. 2004;292:1687–1695. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.14.1687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rosenthal GE, Kaboli PJ, Barnett MJ. Differences in length of stay in Veterans Health Administration and other United States hospitals: is the gap closing? Med Care. 2003;41:882–894. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200308000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]