Abstract

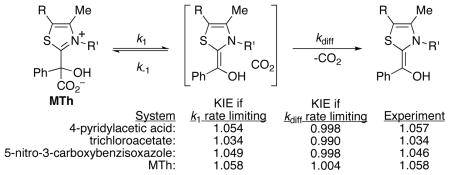

The mechanism of decarboxylations in water and the catalysis of mandelylthiamin (MTh) decarboxylation by pyridinium ions is explored. It has been recently proposed that a decarboxylation step forming an intermediate molecule/CO2 pair is reversible, and that pyridinium ions catalyze the MTh decarboxylation by trapping the intermediate, preventing reversion to MTh. A calculation of the barrier for the back reaction goes against this proposal, as the diffusional separation of CO2 would be on the order of 10,000 times faster. A comparison of predicted and experimental isotope effects for a series of decarboxylations including the MTh reaction shows in each case the absence of significant reversibility of the decarboxylation step. An alternative origin of the pyridinium catalysis of decarboxylation is proposed, based on the formal binding of the pyridinium ions to the decarboxylation transition state.

Catalysis is normally understood as resulting from the reduction of activation barriers. Within this idea, the impact of a mechanistic step’s catalysis is limited by the degree to which the step is rate limiting and by the size of the barrier before catalysis. A series of recent papers on biomimetic decarboxylations by Kluger and coworkers appears to expand this view of catalysis,1 as the proposed catalyzed step is the diffusion apart of two neutral simple molecules, normally a nearly barrierless process. By extension, this same phenomenon was suggested to be important in enzymatic catalysis. We find here that the experimental observations in the decarboxylation studied are not consistent with the mechanism and nature of catalysis previously proposed, and we present a more mundane alternative mechanism.

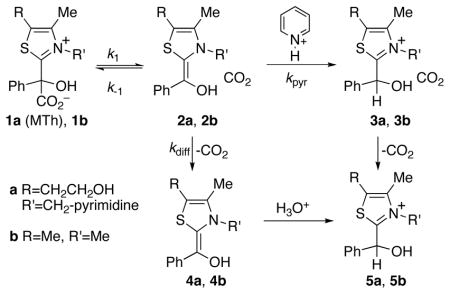

Mandelylthiamin (MTh, 1a) undergoes decarboxylation in water at pH 5 to 7 with a rate constant of 3 × 10−4 s−1.1b This decarboxylation is accelerated, up to a factor of 4, in the presence of pyridinium ions. Notably, N-ethylpyridinium ions and neutral protic acids provide no catalysis. To explain these observations, Kluger and coworkers proposed that the decarboxylation step affording the intermediate enol/CO2 cage 2a is reversible and “overwhelmingly reverts to the carboxylate” in the absence of catalyst, i.e. k−1 ≫ kdiff. Within this proposal, pre-associated pyridinium ions would catalyze the reaction by trapping 2a, preventing reversion to MTh.

This mechanism requires that the reaction of the two adjacent but neutral closed-shell molecules in 2a be faster than their diffusional separation. However, from known CO2 diffusion constants2 and Einsteinian diffusion theory,3 a free CO2 molecule in water diffuses on average 5 Å in about 20 ps or 10 Å in about 80 ps. Moreover, the reformation of MTh from 2a should not be barrierless; M06-2x/6-31+G**/PCM(water)4 calculations place the enthalpic and free-energy barriers for formation of model 1b from complex 2b at 6.3 and 8.5 kcal/mol,5 leading to a predicted k−1 of 4 × 106 s−1. This suggests that reformation of MTh should be on the order of 10,000 times slower than diffusion, precluding the proposed catalytic mechanism.

The experimental 13C kinetic isotope effect (KIE) of 1.058 for the uncatalyzed reaction1c of MTh at 25 °C provides more direct evidence against the literature mechanism. We investigated the MTh decarboxylation as well as the mechanism of three contrasting decarboxylations in water (4-pyridylacetic acid,6,7 trichloroacetate,8 and 5-nitro-3-carboxybenzisoxazole9) by our standard process in which KIE predictions for mechanistic possibilities are compared with the experimental values. Predicted KIEs for fully rate-limiting decarboxylation steps in these reactions were based on transition structures located in M06-2x/PCM calculations. If subsequent diffusional separation of the CO2 from 2b (or analogous intermediates for the other molecules) were fully rate limiting, the KIE would be the equilibrium isotope effect for the formation of the intermediate times the KIE for the diffusion step. The necessary equilibrium isotope effects for the four reactions were based on calculated structures and were in a range from 0.989 to 1.003; this corresponds perfectly with known equilibrium 13C isotope effects for typical decarboxylations in water.10 A KIE for the diffusion step of 1.0007 was assumed based on the experimental effect on the diffusion coefficient for 12CO2/13CO2 in water.11

The results are summarized in Table 1. The experimental KIEs do not fit at all with those predicted for rate-limiting diffusion, but the KIE predictions based on fully rate-limiting decarboxylation steps are strikingly accurate. Across the board, these results exclude significant reversibility of the decarboxylation step.

Table 1.

Experimental versus M06-2x/6-31+G**/PCM-predicted 13C KIEs (12k/13k) for decarboxylations in water.

| system and mechanistic assumption | predicted KIE | experimental KIE |

|---|---|---|

| 4-pyridylacetic acid, 25 °C | ||

| rate limiting decarboxylation | 1.054a,b | 1.057c |

| rate limiting diffusion | 0.998 | |

| trichloroacetate, 70.4 °C | ||

| rate limiting decarboxylation | 1.034b,d | 1.034e |

| rate limiting diffusion | 0.990 | |

| 5-nitro-3-carboxybenzisoxazole, 20 °C | ||

| rate limiting decarboxylation | 1.049b | 1.046f |

| rate limiting diffusion | 0.998 | |

| MTh, 25 °C | ||

| k1 fully rate limiting | 1.058b | 1.058g |

| kdiff fully rate limiting | 1.004 | |

| k−1≥ 3 × kdiff | ≤1.018 |

For the MTh decarboxylation, one must consider an intermediate case in which the decarboxylation step and the subsequent diffusion/pyridinium trapping steps are each partially rate limiting. Assuming propositionally the literature mechanism, the observed rate constant kobs would be governed by eq 1. The right hand side of eq 1 can never exceed k1, so the maximum possible acceleration by pyridinium catalysis, kmax/kuncat, is limited by eq 2. No catalysis is possible if kdiff ≫ k−1. The experimentally observed acceleration of at least a factor of 4 would imply that k−1 ≥ 3 × kdiff. This leads to a maximum predicted KIE of 1.018. No realistic combination of alternative assumptions (i.e. among precedented KIEs for decarboxylation or diffusion or reasonable equilibrium isotope effects for formation of 2a) would lead to a 13C KIE approaching 1.058. In other words, the experimental 13C KIE for the uncatalyzed reaction unambiguously precludes sufficient reversibility in the decarboxylation step to allow any significant catalysis by pyridinium trapping of the intermediate. The catalysis must be explained in another way, and no other evidence discretely implicates reversibility.

| (1) |

| (2) |

The careful work of Kluger and coworkers excluded a number of alternative mechanisms, and one is left to conclude that the pyridinium ions catalyze the reaction by directly affecting the decarboxylation step itself. How? The cation/π interaction of pyridinium ions with arenes is strong in the gas phase,12 and it remains significant in aqueous solution.13 In passing from starting MTh to transition state, the phenyl group should become more electron rich and the thiaminium cation evolves into a neutral methylenedihydrothiazol (see the Supporting Information for a discussion of charges in 2). Both changes favor coordination. We supposed that the pyridinium could coordinate with either the phenyl group or the incipient methylenedihydrothiazol at the transition state. In support of the latter possibility, strong T-shaped and face-face stacked complexes of pyridinium with methylenedihydrothiazol were located, involving interaction energies (MP2/6-311G** + zpe) of 19.7 and 18.1 kcal/mol, respectively.

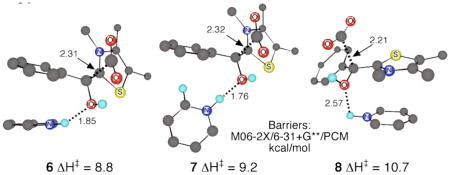

To explore the potential of a cation/π interaction to catalyze the decarboxylation of MTh, M06-2x/6-31+G**/PCM(water) calculations were employed to locate transition structures for decarboxylation of 1b complexed with pyridinium. Eighteen such structures were located with pyridinium in various positions and orientations, and eight of these had calculated formal transition state binding enthalpies (defined by the harmonic enthalpy versus that of the uncatalyzed transition structure and separate pyridinium) greater than 6 kcal/mol. The three lowest-enthalpy structures, 6–8, are shown; others are given in the Supporting Information. Structures 6 and 7 were lowest in the M06-2X calculations; structures 6 and 8 were lowest in MP2/6-311+G** single-point energies.

Including harmonic gas phase entropy estimates with the M06-2x/PCM enthalpies, the predicted free-energy barrier for decarboxylation via 6 is at a 1 M standard state 1.8 kcal/mol below that of the uncatalyzed reaction. Allowing for an experimental pyridinium concentration of 0.4 M, the catalyzed reaction would be predicted to occur about 8 times faster than the uncatalyzed. Considering the difficulty of the calculation, and particularly the simplification of the entropy estimate, this striking agreement with experiment (within 0.4 kcal/mol) is to some degree fortuitous. Nonetheless, the calculated energetics are clearly consistent with an origin of the observed catalysis in pyridinium binding to the transition state.

An intriguing feature of the lowest-energy catalyzed transition structures is that they combine a cation/π face-face or T-shaped interaction with hydrogen bonding to the hydroxyl group. This chelating combination appears critical to the catalysis; the formal transition state binding is unsurprisingly much weaker in the many decarboxylation transition structures exhibiting only one of the interactions. This fits well with the observation that N-ethylpyridinium ions and neutral protic acids provide no catalysis. This simple catalysis by transition state binding is also consistent with the observation that the H/D solvent isotope effect on the catalysis is near unity.14

In summary, a comparison of predicted and experimental isotope effects shows that there is no significant reversibility in simple decarboxylations in water. From diffusion versus recombination rates, no reversibility is to be expected for the MTh decarboxylation. The calculations suggest that the catalysis that had been the evidence for reversibility arises from simple formal binding to the transition state.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank NIH grant # GM-45617 and The Robert A. Welch Foundation for financial support.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Complete descriptions of calculations and structures. (PDF). This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.(a) Hu Q, Kluger R. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:12242–12243. doi: 10.1021/ja054165p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Kluger R, Ikeda G, Hu Q, Cao P, Drewry J. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:15856–15864. doi: 10.1021/ja066249j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Mundle SOC, Rathgeber S, Lacrampe-Couloume G, Lollar BS, Kluger R. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:11638–11639. doi: 10.1021/ja902686h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Kluger R, Tittmann K. Chem Rev. 2008;108:1797–1833. doi: 10.1021/cr068444m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Kluger R, Rathgeber S. FEBS J. 2008;275:6089–6100. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2008.06739.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Longmuir IS, Forster RE, Woo CY. Nature. 1966;209:393–394. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Einstein A. Ann Phys. 1905;17:549–560. [Google Scholar]

- 4.The M06-2X calculations underestimate the free-energy barrier for the decarboxylation of model 1b versus experiment with MTh by 3 kcal/mol, but were chosen for their general strong performance and ability to estimate aromatic stacking interactions. (See Zhao Y, Truhlar DG. Acc Chem Res. 2008;41:157–167. doi: 10.1021/ar700111a.)

- 5.Enthalpic barriers were similar or higher in other calculations, e.g., 6.3 and 8.4 kcal/mol in MP2/6-311+G**/PCM//M06-2X and B3LYP/6-31+G* calculations, respectively.

- 6.Marlier JF, O’Leary MH. J Am Chem Soc. 1986;108:4896–4899. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sicinska D, Truhlar DG, Paneth P. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:7683–7686. doi: 10.1021/ja010791k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bigeleisen J, Allen TL. J Chem Phys. 1951;19:760–764. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lewis C, Paneth P, O’Leary MH, Hilvert D. 1993;115:1410–1413. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rishavy MA, Cleland WW. Can J Chem. 1999;77:967–977. [Google Scholar]

- 11.O’Leary MH. J Phys Chem. 1984;88:823–825. [Google Scholar]

- 12.(a) Tsuzuki S, Mikami M, Yamada S. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;109:8656–8662. doi: 10.1021/ja071372b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Singh NJ, Min SK, Kim DY, Kim KS. J Chem Theory Comput. 2009;5:515–529. doi: 10.1021/ct800471b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Acharya P, Plashkevych O, Morita C, Yamada S, Chattopadhyaya J. J Org Chem. 2003;68:1529–1538. doi: 10.1021/jo026572e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ikeda G. PhD Dissertation. University of Toronto; 2008. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.