Summary

Clusters of complement-type ligand binding repeats in the LDL receptor family are thought to mediate the interactions with their various ligands. Apolipoprotein E, a key ligand for cholesterol homeostasis, has been shown to interact with LRP through these clusters. The segment comprising the receptor binding portion of ApoE (residues 130–149) has been found to have a weak affinity for isolated complement repeats. We have fused this region of ApoE to a high affinity CR from LRP (CR17) for structural elucidation of the complex. The interface reveals a motif that has previously been observed in CR domains with other binding partners, but with several novel features. Comparison to free CR17 reveals that very few structural changes result from this binding event, but significant changes in intrinsic dynamics are observed upon binding. NMR perturbation experiments suggest that this interface may be similar to several other ligand interactions with LDL receptors.

Keywords: ApoE, LRP, lipoprotein, Complement repeat, NMR structure

INTRODUCTION

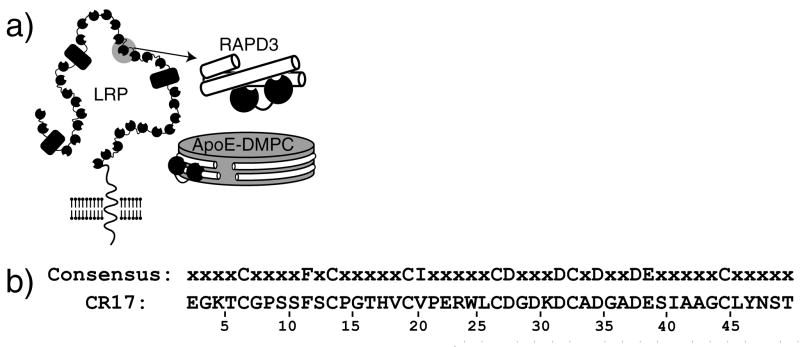

Members of the Low Density-lipoprotein Receptor (LDLR) family are responsible for the uptake of a variety of ligands, and are essential for cholesterol homeostasis 1; 2. Ligand interactions occur with ligand binding clusters of 2–11 Complement repeats (CRs) (Fig. 1a). Each CR is composed of 40–50 amino acids with the overall fold stabilized by three disulfide bonds and a high affinity calcium binding site 3; 4. A number of NMR and crystallographic structures of CRs have been solved, and the fold is highly conserved 5. Besides the consensus six cysteines and calcium coordinating residues, few residues are required for proper folding (Fig. 1b) 6. These domains therefore, are able to achieve the same fold with significant variation in their many surface exposed loops, which is thought to provide the basis for specificity toward various ligands1.

Figure 1.

a) Diagram of LRP with complement repeats (circles) and EGF & β-propeller domains shown together (rectangles) with CR17 highlighted. Schematic of a pair of CRs binding to the three helix bundle RAPD3 and hypothesized binding of CRs to ApoE-DMPC particles is shown on the right. b) Sequence of CR17 from LRP with minimum consensus for a CR domain.

The LDL receptor-related protein 1, referred to here as LRP, is responsible for the clearance of at least 30 ligands 2. This large 600kDa protein contains three complete clusters of CRs each of which are larger than the cluster of CRs in LDLR. Several studies have shown that these clusters of CRs in LRP, termed sLRPs, can interact with many ligands in vitro 7; 8. Like other members of this receptor family LRP can bind and internalize Apolipoprotein E (ApoE)-containing β-migrating very low density lipoproteins (β-VLDLs) 9; 10.

Apolipoprotein E is a physiologically relevant ligand for LDLR and LRP. It is found in several classes of lipoproteins and common variants are associated with type III hyperlipoproteinemia 11. Substantial evidence indicates that receptors recognize residues 140–150 12; 13; 14. Incorporation of peptides containing these residues into lipoprotein particles enhances particle uptake in vitro and in vivo 15; 16; 17. ApoE(130–149) has been shown to interact with each sLRP of LRP 18, and to isolated CRs with lower affinity 19. The lipid free crystal structure of the N-terminal domain of ApoE revealed that this region forms a helix, with solvent exposed lysines 20. However only upon lipid association does ApoE protein bind receptors with high affinity 21; 22.

Lipid association of ApoE can enhance receptor binding by several mechanisms. Since multiple copies of ApoE are embedded in lipoprotein particles, strings of CRs could bind to several ApoEs at once, creating an avidity effect 19; 23; 24 (Fig. 1a). A second possibility is that lipid binding causes a conformational change within ApoE to a form that binds the receptor more tightly. Although residues 130–150 maintain their helical structure, studies suggest that upon lipid binding, the four helix bundle unwinds and the microenvironments of residues in this region change 25; 26; 27; 28. A low resolution crystal structure of ApoE bound to dipalmitoylphosphatidylcholine (DPPC) particles also suggested that the helices reorient to form high affinity receptor sites 29.

Although no structures have been determined with a physiological ligand such as ApoE, structures of CRs in complex with binding partners have been determined, including the receptor associated protein (RAP) domains 1 and 3, the rhinovirus capsid, and the β-propeller domain of LDLR itself 30; 31; 32; 33. RAP is a folding chaperone for LRP, and can also block binding of several ligands of LRP 34; 35. RAPs three domains each form a three helix bundle capable of binding to pairs of CRs with varying affinities, RAPD3 being the highest 35; 36; 37 (Fig. 1a). RAPD3 has also been shown to interact with single CRs with affinities in the mid μM range 19. The structures of these ligands bound to various CRs all show basic residues from the ligand contacting a surface exposed aromatic residue and acidic residues that surround the calcium binding site. Computational and homology models have been proposed for the interface of ApoE with LA5 from LDLR 31; 38, but as of yet no structural information has been obtained for any ApoE-receptor interaction. To elucidate the structure of this interaction, we have used NMR titrations in combination with a fusion strategy to obtain specific structural information on the interface between ApoE(130–149) and CR17 of LRP.

RESULTS

Chemical shift perturbations of CR17 upon ligand binding

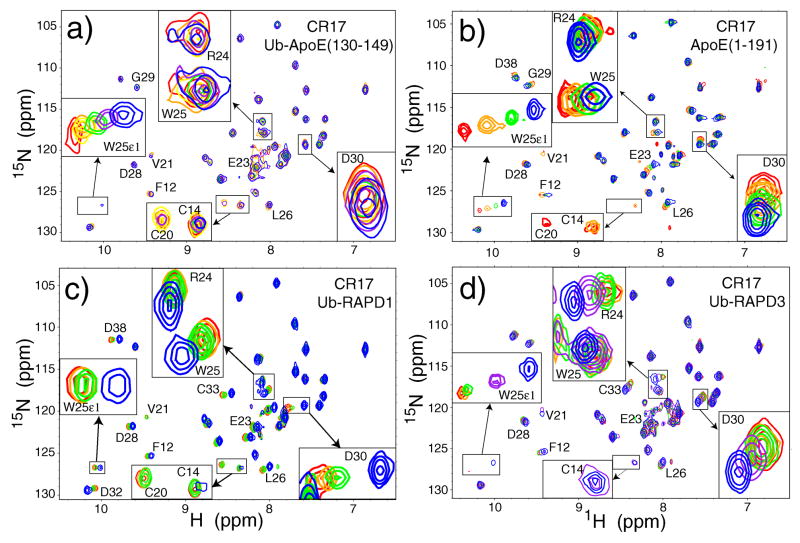

NMR titrations were first used to compare the binding of ApoE(130–149) (Ub-ApoE) and ApoE(1–191) to CR17. Due to solubility problems upon addition of excess ApoE(130–149) all titrations were done using a ubiquitin fused Ub-ApoE(130–149), which facilitated the solubility of the complex. Identical aliquots of 15N labeled CR/LAs were resuspended in either Ub-fused ligand or Ub, adjusted to pH 7.45, and mixed in various ratios to yield samples with varying concentrations of ligand but identical total protein concentration. Both ApoE constructs elicited similar perturbations upon binding (Fig. 2a, b) and caused a significant downfield shift of the Hε1 proton in the sidechain of W25 (numbering in Fig. 1b). Similar trends in perturbations were also seen for other highly perturbed resonances (F12, E23, R24, W25, L26) (Supp. Fig. 1a). Resonances for C14 and C20 also sharpened upon binding of both ApoE(130–149) and ApoE(1–191). Although the 15N resonance of D30 shifted downfield upon addition of both ApoE constructs, the amide 1H showed minor differences as did resonances for S13, C27, C33, D37, and S40. The binding affinities were calculated from the titrations using three different fitting methods as described previously 19, and showed that ApoE(1–191) had a higher affinity for CR17 than Ub-ApoE(130–149) (217 +/−20μM vs. 930 +/−90μM) (Supp. Fig. 1b).

Figure 2.

Titrations of a) Ub-ApoE(130–149), b) ApoE(1–191), c) Ub-RAPD1, d) Ub-RAPD3 into CR17. Residues undergoing strong changes are labeled and in some cases expanded. HSQC spectra following titrations are overlayed and colored from blue (no ligand) to purple, green, orange, and red (highest concentration of ligand).

Titrations of CR17 were also performed with Ub-RAPD3 and Ub-RAPD1 to compare the interface between ApoE and the two RAP domains. A downfield shift in the sidechain indole Hε1 resonance of W25 was observed in all cases, but the perturbation was less pronounced upon RAPD1 binding than upon RAPD3 binding (Fig. 2c, d). Many of the same amide resonances were perturbed upon RAP binding, however the direction of the shifts differed compared to shifts upon ApoE binding. Residues F12, L26, R24 showed similar shifts to that seen with ApoE, but W25 and D30 shifted in different directions compared to ApoE binding. The appearance of sharp cross peaks for C14 and C20 was observed upon RAPD1 binding, but with RAPD3 both residues completely disappeared. Both RAP domains also caused perturbations at C33, not seen in ApoE titrations. Additionally RAPD1 caused significant changes in D32, D38, L46 and Y47. Both Ub-RAPD1 and Ub-RAPD3 had relatively high affinities for CR17 (96 +/− 12μM, 35 +/− 4μM respectively) (Supp. Fig. 1b).

Chemical shift perturbation of ApoE(130–149) upon CR17 binding

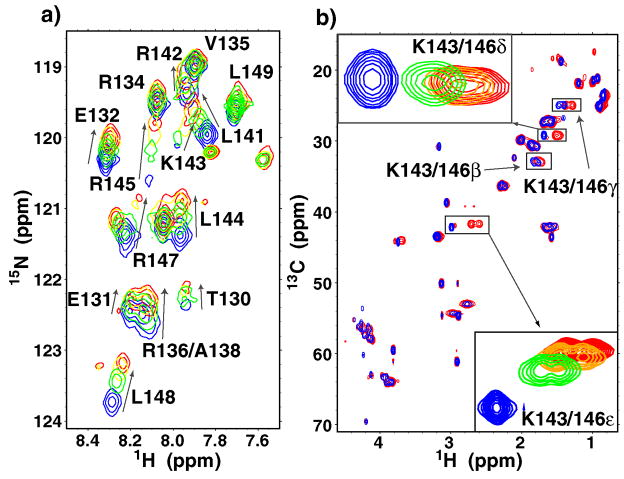

To examine changes within ApoE(130–149) upon binding CR17, uniformly 13C-15N-labeled ApoE(130–149) peptide was prepared with an additional Tyr at the N-terminus for quantification. In contrast to the reverse titration, no solubility problems were encountered adding excess CR17 to the ApoE(130–149) sample. Comparisons of Cα and Hα chemical shifts to random coil values indicated that much of the peptide is helical, even in the unbound state 39 (Supp. Fig. 2). Cross peaks for T130, S139, H140, K143, R145, K146, and R147 were weak or invisible suggesting presence of intermediate exchange dynamics or multiple conformations. The addition of CR17 caused an upfield shift in nearly all 15N resonances consistent with higher helical content (Fig. 3a). Titrations monitored by 1H-13C HSQCs showed large upfield shifts for β, γ, δ, and ε protons of K143 and K146 (Fig. 3b). The changes in these two lysines were by far the largest in the ApoE(130–149) peptide. The Cα and Hα shifts upon CR17 binding also indicated higher helicity especially within residues 138–146 (Supp. Fig. 2). From the titration data, the affinity of the peptide for CR17 was calculated to be 780 +/− 180μM, very similar to the value obtained for Ub-ApoE(130–149) binding to CR17 (930 +/− 90μM).

Figure 3.

a) 1H-15N HSQCs overlays of ApoE(130–149) peptide (blue), and with 0.6mM (green), 1.2mM (yellow) and 1.8mM CR17 (red). Lines indicate direction of shifts upon CR17 binding. b) 1H-13C HSCQ overlay of the same samples from a).

Structure of CR17

To understand perturbations on CR17 from the binding of various ligands we sought to solve the solution structure at physiological pH. NOE-based distance restraints were derived from 3D 15N-separated NOESY-HSQC, 3D 13C-separated NOESY-HSQC and 3D 13C-15N separated HMQC-NOESY-HSQC (herein referred to as (H)CNH NOESY). Analysis with Ambiguous Restraint for Iterative Assignment (ARIA2) 40 yielded a total of 971 distance restraints (759 unambiguous and 212 ambiguous). Initial structures calculated without disulfide restraints showed the expected fold and disulfide-bonding pattern seen in all previous structures of CRs solved to date (C1–C3, C2–C4, C4–C6). In addition 9 NOEs were observed in the 13C NOESY between sidechains of disulfide bonded cysteines (Hα-Hβ or Hβ-Hβ). A large downfield shift of the 13C carbonyl of W25 compared to the random coil value (177.34 vs. 173.6ppm) along with the preceding 15N of L26 (125.87 vs. 122.2ppm) is in agreement with its role in calcium coordination as reported previously for CR3 and CR841; 42. Amide exchange experiments only showed weak protection for amides W25, L26, D32, and E39 and no protection for any other residues. Restraint statistics are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Refinement statistics for structure determination of CR17 and CR17-ApoE(130–149)

| NMR Constraints | CR17 | CR17-ApoE(130–149) |

|---|---|---|

| Distance Constraints | ||

| Total unambiguous NOEs | 759 | 1138 (192)(1) |

| Intra-residue | 169 | 217 (59)(1) |

| Sequential (|i – j| = 1) | 152 | 289 (40)(1) |

| Medium-range (|i – j| < 4) | 148 | 248 (36)(1) |

| Long-range (|i – j| > 5) | 200 | 384 (57)(1) |

| Intermolecular* | 49 | |

| Ambiguous | 212 | 876 |

| Hydrogen bonds | 3 | 3 |

| Dihedral angle restraints | 44 | 78 |

| φ | 22 | 39 |

| ψ | 22 | 39 |

| Structural Statistics | ||

| Violations (mean and s.d.) | ||

| Distance constraints (Å) | 0.0555 +/− 0.0031 | 0.0459+/− 0.0038 |

| Dihedral Angle Constraints (°) | 0.7575 +/− 0.03415 | 0.5681 +/− 0.1294 |

| Max distance constraint violation (Å) | 0.4251 +/− 0.03415 | 0.433 +/− 0.03277 |

| Max dihedral angle violation (°) | 3.1276 +/− 1.291 | 3.441 +/− 1.132 |

| Deviations from idealized geometry | ||

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.0013 +/−0.00009 | 0.0016+/−0.00001 |

| Bond angles (°) | 0.2613 +/−0.0106 | 0.3325 +/− 0.0117 |

| Impropers (°) | 0.129 +/− 0.0122 | 0.177 +/− 0.0152 |

| Average pairwise r.m.s. deviation (Å) (20 structures) | ||

| All backbone atoms | 0.92 +/− 0.18(2) | 0.64 +/− 0.13(2) |

| All heavy atoms | 1.13 +/− 0.19(2) | 0.76 +/− 0.11(2) |

| All backbone atoms | 0.83 +/− 0.15(3) | |

| All heavy atoms | 1.11 +/− 0.16(3) | |

| Rmsd between structures (Å) (4) | ||

| All backbone atoms | 1.29 | |

| All heavy atoms | 1.75 | |

| Ramachandran Plot Statistics (%) | ||

| Most favored regions | 73.9(1) | 74.2(2) |

| Additionally allowed regions | 25.3 | 24.9 |

| Generously allowed regions | 0.6 | 0.6 |

| Disallowed regions | 0.2 | 0.3 |

Unambiguous restraint between ApoE(130–149) and CR17 (residues 1–50)

Unambiguous NOEs for only the GS linker and ApoE(130–149) region.

Statistics calculations were limited to residues (7–45)

Statistics calculations were limited to residues (7–45, 130–146)

Pairwise rmsd was calculated between the average structures of CR17 & CR17-ApoE, limited to residues (7–45)

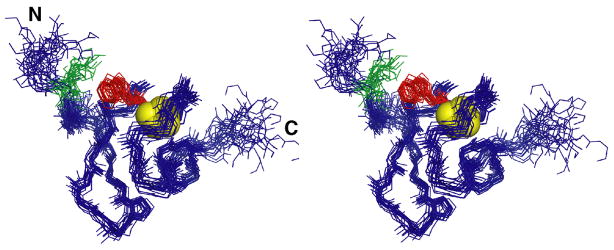

The 20 lowest energy structures of CR17 showed a well resolved core structure with a high degree of flexibility for the six N- and four C-terminal residues (Fig. 4). The calcium binding, disulfide bonding pattern and the overall fold (Greek Ω) match that described for several previously solved CR structures 4; 5; 41; 42; 43; 44, with the exception of the orientation of the N-terminal residues. Despite the absence of amide signals for all residues N-terminal to S11, five unambiguous NOEs were observed in the 13C NOESY between W25-K5 and W25-T6 revealing an intramolecular interaction involving K5 in the linker to CR16 and W25 in CR17. Because of these restraints, the N-terminal tail is bent back onto the surface of CR17. This interaction was likely transient, occurring on an intermediate timescale causing the observed line broadening.

Figure 4.

Stereo view of the backbone of the 20 lowest energy structures of CR17 shown in blue with sidechains of W25 (red) and K5 (green), with calcium ion as yellow spheres.

Fusion construct of CR17-ApoE(130–149)

Due to the weak affinity and fast kinetics of the interaction between CR17 and ApoE(130–149), obtaining specific contact information from intermolecular NOEs did not seem feasible. To circumvent this, a chimeric CR17-ApoE(130–149) fusion was constructed by appending the sequence for ApoE(130–149) at the C-terminus of CR17 with an 8 residue gly-ser linker. The same expression and refolding protocol used for CR17 successfully yielded fusion protein that was able to bind calcium with similar binding affinity to that of isolated CR17 (Supp. Fig. 3).

Comparisons of the 1H-15N HSQCs of CR17 and CR17-ApoE(130–149) showed that W25 Hε1, and the amides of F12, E23, R24, W25, L26, D28, G29 and D30 had the same shifts seen upon Ub-ApoE(130–149) binding to CR17 (Fig. 5). The overlay of the 1H-15N HSQC spectra and Cα region of the 1H-13C HSQC spectra for the fusion and the ApoE(130–149) peptide in the presence of CR17 showed identical trends in chemical shift perturbations for the ApoE (130–149) residues (Supp. Fig. 4). In addition the δ2 and δ3 resonances of W25 showed chemical shift perturbations in the ApoE fusion (Supp. Fig. 5a). Chemical shifts within the fused ApoE(130–149) region revealed an increase in helicity compared to free ApoE(130–149) peptide (Supp. Fig. 2). The same large upfield shifts for the side chain resonances of ApoE K143 and K146 that were seen in titrations of ApoE(130–149) with CR17 were also seen in the fusion (Supp. Fig. 5b, c). In order to test whether the suspected lysines of ApoE (K143, and K146) were causing perturbations within CR17, both were mutated to alanine within the fusion construct. The HSQC of this mutant (KKAA) showed none of the perturbations exhibited by wild type, including no change in the position of the W25 Hε1 resonance (Supp. Fig. 6). A degradation product isolated in the preparation of CR17-ApoE(130–149) was found to be CR17-ApoE(130–136), and the HSQC spectrum of this truncated construct also showed no changes to the above mentioned resonances (Fig. 5). Differences between CR17 and CR17-ApoE(130–136) were all localized at the far C-terminus of CR17, likely due to the presence of the linker.

Figure 5.

1H-15N HSQC overlays of CR17 (blue), CR17-ApoE(130–136) (green), and CR17-ApoE(130–149) (red). Large changes are labeled and expanded.

Native tryptophan fluorescence emission spectra were also recorded and compared for CR17, CR17-ApoE(130–149) and CR17-ApoE(130–136) as an additional method to test whether W25 (the sole tryptophan) was affected by the interaction. The emission spectra of CR17 and in the truncated fusion construct were indistinguishable, but a significant blue-shift was seen in the full length fusion construct (Supp. Fig. 7). This difference was lost upon treating with EDTA and DTT to reduce the disulfide bonds and completely unfold CR17. We were concerned about the possibility of an inter-molecular interaction between the ApoE(130–149) region on one molecule and CR17 on another. Changes in fluorescence signals were not concentration dependent (from 1μM to 100μM) indicating that the interaction is intra-molecular. Size exclusion chromatography also indicated that CR17-ApoE(130–149) is monomeric in solution.

Structure of the CR17-ApoE(130–149) fusion

The CR17-ApoE(130–149) fusion construct was used for NMR structural determination under the same solution conditions used for CR17. Despite the repetitive sequence of ApoE, we were able to assign all backbone and side chain resonances of the ApoE(130–149) region in the fusion protein. Secondary structure prediction using the chemical shift index showed helical propensity for residues 130–144 45. Dihedral restraints obtained from TALOS were also indicative of helical conformation for these same residues 46. Unambiguous i to (i+3) and (i+4) NOEs were observed in residues E131, E132, R134, V135, L137, A138, S139, and H140 confirming the helical nature of this region.

The number of NOE restraints within CR17 in the fusion construct was considerably higher than for the isolated CR17, as many broadened peaks became well resolved. In particular, R24 and H18 had poorly resolved resonances and yielded few restraints (7 and 2, respectively) in CR17, but were well resolved in the CR17-ApoE(130–149) fusion and yielded 20 and 9 restraints, respectively). Thus the precision of the structure of CR17 in the fusion is higher with backbone RMSDs (residues 7–45) of 0.64 +/− 0.13Ǻ compared to 0.92 +/− 0.18Ǻ in the isolated CR domain (Table 1, Fig. 6a). The ApoE(130–149) portion was also well-determined so that the overall RMSDs for the entire structure (residues 7–45 and 130–146) were 0.83 +/− 0.15 for backbone atoms and 1.11 +/− 0.16 for all heavy atoms.

Figure 6.

a) Stereo view of the backbone of the 20 lowest energy structures of CR17-ApoE(130–149). Colors are CR17 (blue), gly-ser linker (orange), and ApoE(130–149) (purple), calcium (yellow spheres), W25 sidechain (red), K143 and K146 sidechains (green). b) Interface of ApoE(130–149) (grey) and CR17 (green). Contacts for K143 to (W25, D28, D32, and D30) are shown as dashed lines.

Analysis of 13C-NOESY and (H)CNH-NOESY spectra identified several NOEs between CR17 and ApoE(130–149) in the fusion construct. After initial refinement, a total of 49 unambiguous interfacial restraints were identified. The final lowest energy structures showed a well-defined structure for the ApoE region (1.01 +/− 0.22 Ǻ backbone, 1.48 +/− 0.27 Ǻ heavy atom within residues 130–146 of ApoE). Many of the restraints at the interface remained ambiguous, likely due to resonance overlap of many Arg and Leu sidechains within this region.

The ApoE forms an alpha helix running along the surface of CR17 with a slight bend at S139. W25 of CR17, K143 of ApoE and to a lesser degree K146 of ApoE(130–149) are directly involved in forming the interface. The side chain of K143 packs against the aromatic sidechain of W25 and points towards the acidic residues (D28, D30 and D32) around the calcium ion (Fig. 6b). The N-terminal part of the helix runs along the side of CR17 with A138 and V135 in ApoE packing against the side chains of R24 and C27 in CR17. E131 and E132 are on one side of the ApoE helix and appear to make an ionic interaction with R24 in CR17. On the other side of the ApoE helix, R134 appears to be making an ionic interaction with E23 and a hydrophobic interaction with L46 in CR17 (Fig. 6b). These interactions position the ApoE(130–149) helix in a unique rotational configuration (with respect to the long helical axis) along the surface of CR17.

The overall fold of CR17 was similar in the presence and absence of the ApoE(130–149) fusion as the RMSD between the average structures for residues 7–45 was 1.29Ǻ (backbone) and 1.61Ǻ (heavy atoms). The largest differences in CR17 occurred at the loop around C7 and at the C-terminal region (Fig. 7a). The difference around C7 is most likely because the ApoE(130–149) displaces the interaction between W25 and K5. The change at the C-terminal end is likely due to the presence of the linker tethering the ApoE(130–149). Only minor changes are seen around the calcium binding site including a slight shift in the position of the W25 sidechain.

Figure 7.

a) Structural alignment of the average structures of CR17 (blue) and CR17-ApoE(130–149) (red). Disulfide bonding cysteines (yellow) along with the sidechain of W25 are shown as sticks. b) Cartoon representation of CR17-ApoE(130–149) showing residues that become more ordered (blue) and more disordered (red). c) R1, R2, hNOE, and S2 measurements for CR17 (blue), CR17-ApoE(130–149) (red), and ApoE(Y130–149) (black). Order parameters (S2) were calculated from model free fitting of the 15N relaxation data.

Dynamics of CR17 and CR17-ApoE(130–149)

15N relaxation measurements were performed on both CR17 and CR17-ApoE(130–149) to examine any differences in the intrinsic dynamics of CR17 upon ligand binding. Comparisons of R1 and R2 relaxation rates between CR17 and CR17-ApoE(130–149) indicated that, as expected, the fusion construct tumbles as a larger protein (Fig. 7c). Several weak (C14, C20, V19, and V21) or absent (T6, K5, E4 and G3) amide cross peaks in CR17 sharpened both upon binding ApoE(130–149) as well as in the CR17-ApoE(130–149) fusion construct. Measurements of heteronuclear NOEs (hNOEs) indicated that residues E23, R24, W25, G29, G36, and D38 become more ordered when bound to ApoE(130–149). Interestingly, F12 and I41 showed the opposite effect (Fig. 7c). Comparisons of hNOE values between free ApoE(130–149) peptide and the ApoE region of CR17-ApoE(130–149) showed higher hNOEs in the fusion construct indicating that the ApoE is more ordered, but not quite ordered as the CR17 domain (Fig. 7c). Order parameters obtained from model free fitting of both CR17 and CR17-ApoE(130–149) indicated that residues 23–25 in the CR17 domain were indeed becoming more ordered in the fusion protein while residues 11–13 actually become more disordered upon binding ApoE(130–149).

DISCUSSION

A fusion of CR17 and ApoE(130–149) to examine the CR-ApoE interface

We previously showed that the ApoE(130–149) receptor binding region interacts specifically, albeit weakly, with several complement repeats including CR17 of LRP 19. Now we show that the ApoE(130–149) peptide binds CR17 very much like the full N-terminal domain (1–191) of ApoE, thus representing a minimal region within ApoE for receptor interaction. Slight differences in 1H and 15N perturbations in CR17 upon binding the ApoE constructs may be due to some conformational difference in the 140–149 region of ApoE, and likely also from the different solution conditions (notably inclusion of ubiquitin as a negative control in one of the experiments). The four-fold stronger affinity of the full N-terminal domain compared to the Ub-fused peptide is most likely due to the presence of R150 or other proximal residues in ApoE(1–191) forming additional contacts with CR17.

Due to the relatively weak interaction between CR17 and ApoE(130–149), structural elucidation of this complex required the construction of a fusion protein. A similar fusion approach had been used for solving the interface of the second protein interaction domain (PID) of FE65 with the C-terminal tail of APP and also for α-spectrin SH3 domain with an interacting decapeptide peptide 47; 48. Tethering of ApoE(130–149) to the C-terminus of CR17 will limit the binding mode, however, the 30Ǻ gly-ser linker together with the unstructured C-terminal tail of CR17, should allow the ApoE helix to access any surface of CR17. The fused ApoE(130–149) caused the same chemical shift perturbations in CR17 as Ub-ApoE(130–149) added to CR17 in trans (Supp Fig. 4). Despite this caveat, the fusion construct allowed for specific NOEs to be obtained revealing the structure of the interface, and was also used to examine dynamics of the bound form of CR17.

A conserved motif for CR-interface formation

The interface with ApoE(130–149) shares similarities with previously studied CR-protein complexes, with some novel features. Initial titrations suggested that the ApoE interface at least in part is similar to that of RAPD1 and RAPD3 as similar sets of residues showed perturbations. K143 and K146 of the ApoE helix contact the sidechain of W25 and form electrostatic interactions with the acidic residues around the calcium ion of CR17. This type of interface has been seen in all other structures of bound CR’s 1; 32, and had been predicted as the mode of ApoE binding to LA5 of LDLR both by comparison to the RAPD3 co-structure 31 and from rationally docked structures 38.

Both lysines showed large chemical shift changes upon CR17 binding and mutation of these two lysines to alanines impaired the intramolecular interaction in CR17-ApoE(130–149) (Supp. Fig. 6). We have previously shown this same double mutation in Ub-ApoE(130–149) decreased the binding affinity for CR17 by five-fold 19. Both K146 and K143 are at the interface, but contrary to the predicted models, it is K143, not K146, that faces the acidic cluster in CR17 (Fig. 6b). Surprisingly, compared to previous structures the amine of K143 was still 7Ǻ away from the carboxylate of D30 whereas the distance between the same aspartate (D29) and the binding lysine was less than 3Ǻ in both LA3 and LA4 bound to RAPD3. Mutation of this aspartate disrupted RAP binding 49 and similarly mutation of D30A in CR17 decreased the affinity for Ub-ApoE(130–149) nearly 10 fold 19. Therefore we speculate that D30 together with D28 and D32 (involved in Ca+2 binding) form a long-range electrostatic interaction with K143.

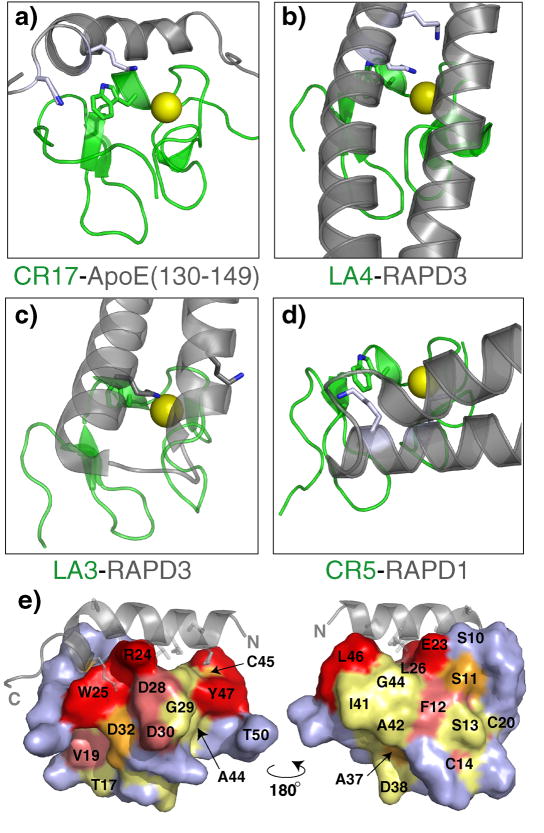

Unlike the interfaces of LA34 with RAPD3 31 and the HADDOCK model of CR56 bound to RAPD1 32, much of the ApoE helix contacts CR17 on the side rather than directly at the calcium binding site (Fig. 8a-d). Favorable ionic interactions involving the N-terminal half of ApoE(130–149) are likely positioning the helix on this face of CR17. To some degree these interactions result in a slight bend in the ApoE helix around S139. Since both S139 and H140 amide cross peaks are weak or invisible in the free and bound forms of ApoE(130–149) distortions may already be occurring in this part of the helix prior to binding. However since ApoE(1–191), with the fixed four helix bundle, can also interact with CR17, it is unlikely that this bend is critical for the interaction.

Figure 8.

Difference in orientation among CR-ligand interfaces for a) CR17-ApoE(130–149), b) LA4-RAPD3 (pdb 2FCW), c) LA4-RAPD3 (pdb 2FCW), d) CR5-RAPD1 (pdb 2FYL). Each interface is aligned relative to the CR17 part of CR17-ApoE(130–149) with CR in green and ligand in grey. Critical Trp/Phe and Lys residues at the interfaces are shown as sticks, and calcium ions are show as yellow spheres. e) Mapping of chemical shift perturbations from fusion of ApoE(130–149) (grey) on the surface CR17. Residues on CR17 are colored based on degree of perturbations; strong (red), medium (pink), weak (orange), no shift (yellow) and no data (blue). V21 is at the center of CR17, and therefore not visible in this representation.

The structure of ApoE(130–149) bound to CR17 likely represents the lipoprotein-associated receptor binding form of ApoE. This segment of the helix has been shown to still be helical after lipid association of ApoE 26; 29. All of the leucines, along with H140, in the ApoE helix face away from the CR17 interface, and are probably embedded in the lipid particles, as was seen in the NMR structure of DPC bound ApoE (126–183) 25. Lipid binding has been shown to further expose the sidechains of K143 and K146 25; 28 which could enhance receptor binding, as both of these residues form contacts with CR17.

Regions in CR17 show both increased and decreased backbone dynamics upon ApoE(130–149) binding

Decreased dynamics upon binding ApoE(130–149) primarily occurs at the binding interface (Fig. 7b). Dynamics measurements showed that ApoE(130–149) binding orders the loop around W25. The interaction may also be further ordering the calcium cage, which could explain the changes seen in hNOE values for E38, G29 and G36. Residues S11 and F12, which are on the opposite face of the molecule, became more disordered upon binding. Only a very slight structural change was observed for this region upon ApoE(130–149) binding, and it is likely that the chemical shift perturbations observed upon ApoE(130–149) binding are reporting intrinsic dynamics changes. These indirect effects could also explain the changes seen in V21, V19, C14 and C20, which also showed chemical shift perturbations but are not near the binding interface (Fig. 8e). Amide cross peaks for all four of these residues are broad in free CR17 but sharpen in the ApoE bound form, also revealing dynamic changes.

Prediction of other CR-ligand interfaces

Previous NMR chemical shift perturbation experiments with CR3 of LRP and the receptor binding domain of alpha 2 macroglobulin (α2M-RBD) 41 showed several similarities to our CR17 binding to ApoE(130–149). These include the large downfield shift in the indole of W23 (W25 in CR17), and the changes in cross peaks for F11, I19, E21, K24 and D30 (corresponding to F12, V21, E23, L26, and D32 in CR17). Like ApoE, α2M also has two critical lysine residues required for receptor binding 50. In light of these similarities it is likely that α2M binds CR3 with a similar interface, in which lysine 1370 or 1374 interacts with W23 of CR3 along with the acidic residues around the calcium ion. We can also speculate that some of the perturbations in CR3 (notably F11 and I19) were likely reporting intrinsic dynamic changes, just as they are in CR17.

Materials and Methods

Protein expression and purification

Cloning of CR17 (residues 2712–2754 of mature human LRP) in a modified pMMHb vector was previously described 19. Residues 130–149 of ApoE were PCR amplified and ligated into the modified pMMHb with an extra tyrosine at the N-terminus for quantitation. The fusion protein, CR17-ApoE(130–149), was constructed by re-cloning CR17 without a stop codon, then inserting PCR amplified ApoE(130–149) with an extra 4x(glycine-serine) linker at the 3′ BamH1 site to link the coding sequences. All mutants were made using either inverse PCR 51 or Quickchange (Stratagene) mutagenesis, and verified by DNA sequencing. Ubiquitin (Ub) fused RAPD1(19–112) was cloned as described previously for RAPD3(218–323) and ApoE(130–149) 19. A vector containing His-tagged human ApoE4(1–191) was a kind gift from S. Blacklow.

Ub-fused RAPD1, D3, and ApoE(130–149) expression vectors were introduced into BL21-DE3s, grown in LB to OD600 0.5, induced with 0.1mM IPTG isopropyl-beta-D-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) for 4 hrs at 37°C. Cells were harvested resuspended in TBS (50mM Tris pH 8.0 500mM NaCl), lysed by sonication, and the protein was purified by Ni-NTA (Qiagen), followed by size exclusion chromatography through Sephadex 75 (GE healthcare) in MB150 (20mM Hepes pH 7.45, 150mM NaCl, 10mM CaCl2, and 0.02% azide). Ub-ApoE(130–149) was further purified with an additional cation exchange (monoS) (GE healthcare) step prior to size exclusion. ApoE(1–191), were prepared as described previously 19. ApoE(130–149) peptide was expressed in BL21-DE3s at 37°C for 12 hours. Inclusion bodies were purified over Ni-NTA (Qiagen) in resolubilizing buffer (8M Urea, 50mM Tris (pH 8.0), 500mM NaCl). A gradient was run from resolubilizing buffer to thrombin cleavage buffer (50mM Tris, pH 8.0, 150mM NaCl, 2mM CaCl2, total volume 100mL), and peptide was eluted by cleavage with 4μg/column of active bovine thrombin at 25°C for 2 hours (30mL volume). A final HPLC purification by C18 reverse phase HPLC (15 × 300mm id column, Waters), in 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) with a gradient of 10 to 50% acetonitrile at 10 ml/min, yielded around 300μg pure peptide per liter growth media. All expressed constructs were analyzed by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry on a Voyager DE-STR (Applied Biosystems), in sinnapinic acid (Agilent). Protein was lyophilized from HPLC buffer and stored at −80°C.

ITC

Calcium binding was measured with a MicroCal VP-ITC calorimeter at 35°C. Dried protein was resuspended in Chelex (Biorad)-treated buffer (20mM Hepes (pH 7.45), 150mM NaCl, 0.02% azide). Complement repeats were titrated with 10 fold molar excess of CaCl2 in the same buffer. All data were analyzed in Origin 7.0 (OriginLab).

Tryptophan fluorescence measurements of intramolecular interaction

To determine whether the ApoE(130–149) was interacting with the fused CR17, native tryptophan fluorescence was used to monitor effects of binding. CR17, CR17-ApoE(130–149), and CR17-ApoE(130–136) were resuspended into 20mM Hepes (pH 7.4), 150mM NaCl, 10mM CaCl, 0.02% azide. An equal aliquot of protein (10 μM) was resuspended with 10mM EDTA instead of CaCl2 and treated with 10mM DTT at 55°C for 30 minutes to measure the intrinsic fluorescence of the completely unfolded protein. Fluorescence emission spectra were collected on a Fluoromax-2 spectrofluorimeter (Spex) at 35°C using excitation at 293nm. All spectra were normalized to the appropriate buffer blank.

NMR titrations

CR17 was titrated with various ligands and monitored by 1H,15N HSQC at 307°K. In order to minimize secondary effects in the titrations, identical aliquots of 15N labeled CR17 constructs were resuspended in either a solution of Ub-fused ligand or Ub (both in 20mM Hepes (pH 7.45), 150mM NaCl, 10mM CaCl2, and 0.02% azide in 10% D2O). The pH was adjusted to 7.45, and the Ub/Ub-fused ligand samples were mixed in various ratios to yield samples with varying concentrations of ligand but identical total protein concentration. Since ApoE(1–191) did not have the ubiquitin tag, the second aliquot of CR17 was resuspended into matched buffer for the titrations. To examine chemical shift perturbations of the ApoE(130–149) peptide, a similar strategy was used in which 100μM 15N labeled ApoE(130–149) was resuspended with buffer alone or in a solution containing 1.8mM CR17, and subsequently mixed in different ratios. 1H-15N HSQCs as well as 2D 1H-13C HNCO, and 1H-13C HSQC spectra were collected at 298°K. The 15N chemical shift perturbation (CSP) was scaled down by 9.8, and total CSP was calculated from the square root of the sum of the squares of the 1H and 15N changes. KDs were calculated from the titrations as described previously 19.

NMR experiments

Spectra were collected at 307°K on either a Bruker Avance III 600 MHz or a Varian VS 800 MHz spectrometer, both equipped with a cryoprobe. 15N-13C labeled CR17 was resuspended in 20mM D18 Hepes (pH 7.45), 50mM NaCl, 5mM CalCl2, 10% D2O and 0.02% sodium azide (final conc. 0.8mM). Addition of 50mM D7-Arginine and 50mM D5-Glutamic acid (Cambridge Isotope Labs) was necessary for sample stability and improved linewidths 52. Backbone resonances were assigned with 3D CBCA(CO)NH 53, 3D CBCANH 54, and 3D HNCO 55. Sidechain assignments were made with 3D (H)CC(CO)NH 56, 3D 15N-separated NOESY-HSQC (150msec mixing time) 57, 3D 13C-15N separated HMQC-NOESY-HSQC (e.g. (H)CNH NOESY, 150msec mixing time) 58, 3D HCCH TOCSY 59, and 3D 13C-separated NOESY-HSQC (150msec mixing time) 60 spectra as described previously 61. Spin systems for residues not visible in amide resolved experiments were assigned with the 3D HCCH-TOCSY and connectivity established with NOESY spectra. The NOESY spectra were also used to unambiguously assign all of the aromatic resonances. Additional 1H-15N HSQC and 1H-13C HSQCs were collected for CR17 at 298°K to directly compare the chemical shifts to CR17-ApoE(130–149). CR17-ApoE(130–149) fusion (0.8mM) was assigned in the same manner as CR17 except that all spectra were collected at 298°K and the sample was exchanged into 100% deuterated buffer prior to collection of 3D HCCH TOCSY, 3D 13C-NOESY and 3D HCCH COSY spectra.

13C,15N ApoE(130–149) peptide was dissolved in 20mM D-18-Hepes (Cambridge Isotope Labs) pH 7.45, 150mM NaCl, 2mM EDTA (D-12) (Cambridge Isotope Labs), 0.02% sodium azide at a final concentration of 0.5mM. The peptide resonances were assigned using 1H-15N HSQC, CBCA(CO)NH, CBCANH, HNCO, HCC(CO)NH, and 1H-13C HSQC experiments. Data were processed using Azara (Wayne Boucher and the Department of Biochemistry, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK) and analyzed in Sparky (T. D. Goddard and D. G. Kneller, SPARKY 3, University of California, San Francisco).

For dynamics measurements, 15N labeled samples were prepared at final concentrations of ~0.6mM in the same buffer used for assignments. Standard Bruker sequences for relaxation measurements were recorded at 298°K with the following delay times: for T1 (0.001, 0.08, 0.14, 0.3, 0.5, 0.9, 1.5, 3.0 sec) and for T2 (14.4, 28.8, 43.2, 57.6, 72, 100.8, 129.6, 158.4, 201.6 msec). Duplicate 1H-15N heteronuclear NOE experiments were collected in an interleaved manner with and without 1H saturation and a 6 sec recycle delay. Data were processed in NMR pipe 62 and analyzed in Sparky. Peak intensities for T1 and T2 were fit to decaying exponentials in Sparky, with errors taken from the uncertainty of the fit. NOE measurements were calculated by the ratio of peak heights, and error determined by the standard deviation between duplicate experiments. Relaxation data were analyzed using the model free approach 63 assuming isotropic tumbling with the program Tensor2 (Martin Blackledge, Institut de Biologie Structurale, Grenoble, France). For amide exchange measurements, a 0.3mM sample of 15N labeled CR17/CR17-ApoE was dried with buffer, resuspended in 100% D2O, and rapidly scanned with a series of 15 minute HSQC experiments.

CR17 Structure determination

Peak lists from 15N-NOESY, (H)CNH-NOESY and 13C-NOESY, were used as inputs for ARIA2/CNS iterative assignment calculations40. Pseudo-calcium coordination restraints (18 total) were added to specify the octahedral geometry around the calcium binding site as used for several NMR structures of CR domains 32; 41; 42; 64. After initial refinement without disulfide restraints showed that the expected disulfide pattern (C1–C3, C2–C5, C4–C6) in CR17, the 3 disulfide bonds were included as distance restraints, and later as covalent bonds in the final refinement. Dihedral angle restraints (44 total) were predicted from NH, H, Hα, CO, Cα, and Cβ resonance shifts using TALOS 46. Slowly exchanging amides (W25, L26 and E39) from amide exchange experiments, and H-bonding donor acceptor pairs were identified from partially refined structures. Final calculations with calcium were done in CNS 1.2 using the distance geometry simulated annealing (dgsa) protocol 65, with 6 direct distance restraints to the calcium ion as used previously 32. The top 20 (of 100) calculated structures were selected based on minimum restraint violation and deviation from ideal stereochemistry. Structural and restraint statistics for these 20 lowest energy structures are listed in Table 1.

CR17-ApoE(130–149) Structure determination

Peak lists extracted from 15N-, (H)CNH, and 13C-NOESY spectra collected for the CR17-ApoE(130–149) fusion construct were used for iterative assignments/structural calculations in ARIA2/CNS in the same way as for CR17. Initial refinement showed that the CR17 domain adopted the same overall fold as determined for CR17 alone. Backbone dihedrals and secondary structure for CR17-ApoE(130–149) were predicted using TALOS and CSI 45; 46. Several unambiguous restraints between CR17 and ApoE(130–149) obtained from the (H)CNH NOESY and 13C-NOESY spectra were included as long range (1.8–6.0 ) restraints. Additional restraints for these calculations included 78 dihedral angle, 3 H-bonds, 18 pseudo-calcium coordination, and 3 disulfide bonds. To minimize ambiguity, assignments for H2O and D2O experiments were kept separate as minor deviations in resonance shifts between these samples were seen. Final calculations including the calcium ion were performed exactly as for CR17, and final statistics are listed in Table 1.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grant AG025343

Abbreviations

- ApoE

Apolipoprotein E

- CR

complement-type repeat

- EDTA

ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid

- HPLC

high performance liquid chromatography

- HSQC

heteronuclear single quantum coherence

- LA

ligand binding repeat of LDLR

- LDLR

Low density lipoprotein receptor

- LRP LDL

Receptor-related protein 1

- NOE

nuclear Overhauser effect

- hNOE

1H 15N heteronuclear NOE

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- sLRP

ligand binding cluster of LRP

Footnotes

Accession Codes:

Coordinates and NMR assignment data for both CR17 and CR17-ApoE(130-149) have been deposited to the PDB (2knx, 2kny), and BRMB (accession numbers 16482, 16483). Structure figures were made in PyMOL 66.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Blacklow SC. Versatility in ligand recognition by LDL receptor family proteins: advances and frontiers. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2007;17:419–26. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2007.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Herz J, Strickland DK. LRP: A multifunctional scavenger and signaling receptor. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:779–784. doi: 10.1172/JCI13992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown MS, Herz J, Goldstein JL. LDL-receptor structure: Calcium cages, acid baths and recycling receptors. Nature. 1997;388:629–30. doi: 10.1038/41672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fass D, Blacklow S, Kim PS, Berger JM. Molecular basis of familial hypercholesterolaemia from structure of LDL receptor module. Nature. 1997;388:691–693. doi: 10.1038/41798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rudenko G, Deisenhofer J. The low-density lipoprotein receptor: ligands, debates and lore. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2003;13:683–9. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abdul-Aziz D, Fisher C, Beglova N, Blacklow SC. Folding and binding integrity of variants of a prototype ligand-binding module from the LDL receptor possessing multiple alanine substitutions. Biochem J. 2005;44:5075–85. doi: 10.1021/bi047575j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Croy JE, Shin WD, Knauer MF, Knauer DJ, Komives EA. All three LDL receptor homology regions of the LDL receptor-related protein (LRP) bind multiple ligands. Biochemistry. 2003;42:13049–57. doi: 10.1021/bi034752s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Neels JG, van den Berg BMM, Lookene A, Olivecrona G, Pannekoek H, van Zonneveld AJ. The second and fourth cluster of class A cysteine-rich repeats of the low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein share ligand binding properties. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:31305–11. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.44.31305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beisiegel U, Weber W, Ihrke G, Herz J, Stanley KK. The LDL-receptor-related protein, LRP, is an apolipoprotein E-binding protein. Nature. 1989;341:162–4. doi: 10.1038/341162a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kowal RC, Herz J, Goldstein JL, Esser V, Brown MS. Low density receptor-related protein mediates uptake of cholesteryl esters derived from apolipoprotein E-enriched lipoproteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:5810–5814. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.15.5810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rall SCJ, Weisgraber KH, Innerarity TL, Mahley RW. Structural basis for receptor binding heterogeneity of apolipoprotein E from type III hyperlipoproteinemic subjects. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1982;79:4696–700. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.15.4696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weisgraber KL, Innerarity TL, Harder KJ, Mahley RW, Milne RW, Marcel YL, Sparrow JT. The Receptor Binding Domain Of Human Apolipoprotein E. J Biol Chem. 1983;258:12348–12354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lalazar A, Weisgraber KH, Rall SCJ, Gilad H, Innerarity TL, Levanon AZ, Boyles JK, Amit B, Gorecki M, Mahley RW, Vogel T. Site-specific Mutagenesis of human apolipoprotein E. Receptor binding activity of variants with single amino acids substitutions. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:3542–3545. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zaiou M, Arnold KS, Newhouse YM, Innerarity TL, Weisgraber KH, Segall ML, Phillips MC, Lund-Katz S. Apolipoprotein E;-low density lipoprotein receptor interaction. Influences of basic residue and amphipathic alpha-helix organization in the ligand. J Lipid Res. 2000;41:1087–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mims MP, Darnule AT, Tovar RW, Pownall HJ, Sparrow DA, Sparrow JT, Via DP, Smith LC. A nonexchangeable apolipoprotein E peptide that mediates binding to the low density lipoprotein receptor. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:20539–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Datta G, Chaddha M, Garber DW, Chung BH, Tytler EM, Dashti N, Bradley WA, Gianturco SH, Anantharamaiah GM. The receptor binding domain of apolipoprotein E, linked to a model class A amphipathic helix, enhances internalization and degradation of LDL by fibroblasts. Biochem J. 2000;39:213–220. doi: 10.1021/bi991209w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Datta G, Garber DW, Chung BH, Chaddha M, Dashti N, Bradley WA, Gianturco SH, Anantharamaiah GM. Cationic domain 141–150 of apoE covalently linked to a class A amphipathic helix enhances atherogenic lipoprotein metabolism in vitro and in vivo. J Lipid Res. 2001;42:959–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Croy JE, Brandon T, Komives EA. Two apolipoprotein E mimetic peptides, apoE(130–149) and apoE(141–155)2, bind to LRP1. Biochemistry. 2004;34:7328–35. doi: 10.1021/bi036208p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guttman M, Prieto JH, Croy JE, Komives EA. Decoding of lipoprotein - receptor interactions; Properties of ligand binding modules governing interactions with ApoE. Biochemistry. 2010;49:1207–16. doi: 10.1021/bi9017208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wilson C, Wardell MR, Weisgraber KH, Mahley RW, Agard DA. Three-dimensional structure of the LDL receptor-binding domain of human apolipoprotein E. Science. 1991;252:1817–1822. doi: 10.1126/science.2063194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Innerarity TL, Pitas RE, Mahley RW. Binding of arginine-rich (E) apoprotein after recombination with phospholipid vesicles to the low density lipoprotein receptors of fibroblasts. J Biol Chem. 1979;254:4186–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gupta V, Narayanaswami V, Budamagunta MS, Yamamato T, Voss JC, Ryan RO. Lipid-induced extension of apolipoprotein E helix 4 correlates with low density lipoprotein receptor binding ability. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:39294–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608085200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mahley RW, Innerarity TL, Rall SC, Weisgraber KH. Plasma lipoproteins: apolipoprotein structure and function. J Lipid Res. 1984;25:1277–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pitas RE, Innerarity TL, Mahley RW. Cell surface receptor binding of phospholipids protein complexes containing different ratios of receptor-active and inactive E apoprotein. J Biol Chem. 1980;255:5454–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Raussens V, Slupsky CM, Sykes BD, Ryan RO. Lipid-bound structure of an apolipoprotein E-derived peptide. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:25998–26006. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301753200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fisher CA, Ryan RO. Lipid binding-induced conformational changes in the N-terminal domain of human apolipoprotein E. J Lipid Res. 1999;40:93–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fisher C, Abdul-Aziz D, Blacklow SC. A two-module region of the low-density lipoprotein receptor sufficient for formation of complexes with apolipoprotein E ligands. Biochem J. 2004;43:1037–44. doi: 10.1021/bi035529y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lund-Katz S, Zaiou M, Wehrli S, Dhanasekaran P, Baldwin F, Weisgraber KH, Phillips MC. Effects of lipid interaction on the lysine microenvironments in apolipoprotein E. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:34459–64. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005265200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Peters-Libeu CA, Newhouse Y, Hatters DM, Weisgraber KH. Model of biologically active apolipoprotein E bound to dipalmitoylphosphatidylcholine. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:1073–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M510851200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rudenko G, Henry L, Henderson K, Ichtchenko K, Brown MS, Goldstein JL, Deisenhofer J. Structure of the LDL receptor extracellular domain at endosomal pH. Science. 2002;298:2353–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1078124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fisher C, Beglova N, Blacklow SC. Structure of an LDLR-RAP complex reveals a general mode for ligand recognition by lipoprotein receptors. Mol Cell. 2006;22:277–83. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jensen GA, Andersen OM, Bonvin AM, Bjerrum-Bohr I, Etzerodt M, Thøgersen HC, O’Shea C, Poulsen FM, Kragelund BB. Binding site structure of one LRP-RAP complex: implications for a common ligand-receptor binding motif. J Mol Biol. 2006;362:700–716. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Verdaguer N, Fita I, Reithmayer M, Moser R, Blaas D. X-ray structure of a minor group human rhinovirus bound to a fragment of its cellular receptor protein. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2004;11:429–34. doi: 10.1038/nsmb753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Herz J, Goldstein JL, Strickland DK, Ho YK, Brown MS. 39-kDa protein modulates binding of ligands to low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein/alpha 2-macroglobulin receptor. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:21232–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bu GJ, Geuze HJ, Strous GJ, Schwartz AL. 39 kDa receptor-associated protein is an ER resident protein and molecular chaperone for LDL receptor-related protein. EMBO J. 1995;14:2269–2280. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07221.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee D, Walsh JD, Migliorini M, PY, Cai T, Schwieters CD, Krueger S, Strickland DK, Wang YX. The structure of receptor-associated protein (RAP) Protein Sci. 2007;16:1628–40. doi: 10.1110/ps.072865407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Andersen OM, Schwarz FP, Eisenstein E, Jacobsen C, Moestrup SK, Etzerodt M, Thøgersen HC. Dominant thermodynamic role of the third independent receptor binding site in the receptor-associated protein RAP. Biochem J. 2001;40:15408–17. doi: 10.1021/bi0110692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Prévost M, Raussens V. Apolipoprotein E-low density lipoprotein receptor binding: study of protein-protein interaction in rationally selected docked complexes. Proteins. 2004;55:874–84. doi: 10.1002/prot.20080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wishart DS, Sykes BD, Richards FM. Relationship between Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Chemical Shift and Protein Secondary Structure. J Mol Biol. 1991;222:311–333. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(91)90214-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rieping W, Habeck M, Bardiaux B, Bernard A, Malliavin TE, Nilges M. ARIA2: automated NOE assignment and data integration in NMR structure calculation. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:381–382. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dolmer K, Huang W, Gettins PG. NMR solution structure of complement-like repeat CR3 from the low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein. Evidence for specific binding to the receptor binding domain of human alpha(2)-macroglobulin. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:3264–3269. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.5.3264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Huang W, Dolmer K, Gettins PG. NMR solution structure of complement-like repeat CR8 from the low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:14130–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.20.14130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Daly NL, Scanlon MJ, Djordijevic JT, Kroon PA, Smith R. Three-dimernsional structure of a cysteine-rich repeat from the low-density lipoprotein receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:6334–6338. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.14.6334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Simonovic M, Dolmer K, Huang W, Strickland DK, Volz K, Gettins PGW. Calcuim Coordination and pH dependence of the calcium affinity of ligand-binding repeat CR7 from the LRP. Comparision with related domains from the LRP and the LDL receptor. Biochemistry. 2001;40:15127–15134. doi: 10.1021/bi015688m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wishart DS, Sykes BD. The 13C Chemical-Shift Index: A Simple Method for the Identification of Protein Secondary Structure Using 13C Chemical-Shift Data. J Biomol NMR. 1994;4:171–180. doi: 10.1007/BF00175245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cornilescu G, Delaglio F, Bax A. Protein backbone angle restraints from searching a database for chemical shift and sequence homology. J Biomol NMR. 1999;13:298–302. doi: 10.1023/a:1008392405740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Li H, Koshiba S, Hayashi F, Tochio N, Tomizawa T, Kasai T, Yabuki T, Motoda Y, Harada T, Watanabe S, Inoue M, Hayashizaki Y, Tanaka A, Kigawa T, SY Structure of the C-terminal phosphotyrosine interaction domain of Fe65L1 complexed with the cytoplasmic tail of amyloid precursor protein reveals a novel peptide binding mode. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:27165–78. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M803892200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Candel A, Conejero-Lara F, Martinez J, van Nuland N, Bruix M. The high-resolution NMR structure of a single-chain chimeric protein mimicking a SH3–peptide complex. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:687–692. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Andersen OM, Christensen LL, Christensen PA, Sørensen ES, Jacobsen C, Moestrup SK, Etzerodt M, Thogersen HC. Identification of the minimal functional unit in the low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein for binding the receptor-associated protein (RAP). A conserved acidic residue in the complement-type repeats is important for recognition of RAP. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:21017–21024. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M000507200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nielsen KL, Holtet TL, Etzerodt M, Moestrup SK, Gliemann J, Sottrup-Jensen L, Thogersen HC. Identification of residues in alpha-macroglobulins important for binding to the alpha2-macroglobulin receptor/Low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:12909–12. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.22.12909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Clackson T, Detlef G, Jones P. In: PCR, a Practical Approach. McPherson M, Quirke P, Taylor G, editors. IRL Press; Oxford: 1991. p. 202. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Golovanov AP, Hautbergue GM, Wilson SA, LYL A simple method for improving protein solubility and long-term stability. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:8933–9. doi: 10.1021/ja049297h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Grzesiek S, Bax A. An Efficient Experiment For Sequential Backbone Assignment of Medium-Sized Isotopically Enriched Proteins. J Magn Reson. 1992;99:201–207. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Grzesiek S, Bax A. Correlating backbone amide and side chain resonances in larger proteins by multiple relayed triple resonance NMR. J Am Chem Soc. 1992;114:6291–6293. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kay LE, Ikura M, Tschudin R, Bax A. Three-dimensional triple-resonance NMR spectroscopy of isotopically enriched proteins. J Magn Reson. 1990;89:496–514. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2011.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Clowes RT, Boucher W, Hardman CH, Domaille PJ, Laue ED. A 4D HCC(CO)NNH experiment for the correlation of aliphatic side-chain and backbone resonances in 13C/15N-labelled proteins. J Biomol NMR. 1993;3:349–354. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Talluri S, Wagner G. An Optimized 3D NOESY–HSQC. J Magn Reson. 1996;112:200–205. doi: 10.1006/jmrb.1996.0132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kay LE, Clore GM, Bax A, Gronenborn AM. Four-dimensional heteronuclear triple-resonance NMR spectroscopy of interleukin-1 beta in solution. Science. 1990;249:411–4. doi: 10.1126/science.2377896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bax A, Clore GM, Gronenborn AM. Proton-proton correlation via isotropic mixing of carbon-13 magnetization, a new three-dimensional approach for assigning proton and carbon-13 spectra of carbon-13-enriched proteins. J Magn Reson. 1990;88:425–431. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zuiderweg ERP, McIntosh LP, Dahlquist FW, Fesik SW. Three-dimensional carbon-13-resolved proton NOE spectroscopy of uniformly carbon-13-labeled proteins for the NMR assignment and structure determination of larger molecules. J Magn Reson. 1990;86:210–216. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lougheed JC, Domaille PJ, Handel TM. Solution structure and dynamics of melanoma inhibitory activity protein. J Biomol NMR. 2002;22:211–23. doi: 10.1023/a:1014961408029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Delaglio F, Grzesiek S, Vuister G, Zhu G, Pfeifer J, Bax A. NMRPipe: a multidimensional spectral processing system based on UNIX pipes. J Biomol NMR. 1995;6:277–293. doi: 10.1007/BF00197809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lipari G, Szabo A. Model-free approach to the interpretation of nuclear magnetic resonance relaxation in macromolecules. 1. Theory and range of validity. J Am Chem Soc. 1982;104:4546–4559. [Google Scholar]

- 64.North CL, Blacklow SC. Solution structure of the sixth LDL-A module of the LDL receptor. Biochem J. 2000;39:2564–71. doi: 10.1021/bi992087a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Brunger AT. Version 1.2 of the Crystallography and NMR System. Nature Protocols. 2007;2:2728–2733. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.DeLano WL. DeLano Scientific. San Carlos; CA, USA: 2002. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.