Abstract

Background and Purpose

The purpose of this study was to determine whether 74 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), which had been associated with coronary heart disease, are associated with incident ischemic stroke.

Methods

Based on antecedent studies of coronary heart disease, we prespecified the risk allele for each of the 74 SNPs. We used Cox proportional hazards models that adjusted for traditional risk factors to estimate the associations of these SNPs with incident ischemic stroke during 14 years of follow-up in a population-based study of older adults: the Cardiovascular Health Study (CHS).

Results

In white CHS participants, the prespecified risk alleles of 7 of the 74 SNPs (in HPS1, ITGAE, ABCG2, MYH15, FSTL4, CALM1, and BAT2) were nominally associated with increased risk of stroke (one-sided P<0.05, false discovery rate=0.42). In black participants, the prespecified risk alleles of 5 SNPs (in KRT4, LY6G5B, EDG1, DMXL2, and ABCG2) were nominally associated with stroke (one-sided P<0.05, false discovery rate=0.55). The Val12Met SNP in ABCG2 was associated with stroke in both white (hazard ratio, 1.46; 90% CI, 1.05 to 2.03) and black (hazard ratio, 3.59; 90% CI, 1.11 to 11.6) participants of CHS. Kaplan-Meier estimates of the 10-year cumulative incidence of stroke were greater among Val allele homozygotes than among Met allele carriers in both white (10% versus 6%) and black (12% versus 3%) participants of CHS.

Conclusions

The Val12Met SNP in ABCG2 (encoding a transporter of sterols and xenobiotics) was associated with incident ischemic stroke in white and black participants of CHS.

Keywords: brain infarction, cerebrovascular accident, epidemiology, genetics, prevention, risk factors

Multiple reports based on twin studies1,2 and family studies3,4 have shown that genetics contributes to risk of stroke independently of traditional risk factors. Identifying gene variants that are associated with risk of ischemic stroke could shed light on the mechanisms of stroke pathology and potentially lead to new methods for treatment or prevention of this serious and complex disease.

Ischemic stroke and coronary heart disease (CHD) are vascular diseases that, although affecting different vascular beds, share many traditional risk factors such as age, sex, smoking, diabetes, and hypertension.5 Ischemic stroke and CHD also share major pathological processes such as atherosclerosis and thrombosis. We hypothesized that some gene variants associated with CHD would also be associated with ischemic stroke. We selected 74 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) that had been previously shown to be associated with CHD in at least one antecedent association study6 and tested whether the risk alleles of these 74 SNPs were associated with increased risk of incident ischemic stroke in a prospective population-based study of older adults, the Cardiovascular Health Study (CHS).7,8

Materials and Methods

Cardiovascular Health Study

CHS is a prospective population-based study of risk factors for cardiovascular disease, including CHD and stroke, in older adults. Men and women aged ≥65 years were recruited from random samples of individuals on Medicare eligibility lists in 4 US communities (Sacramento County, Calif; Washington County, Md; Forsyth County, NC; and Pittsburgh, Allegheny County, Pa) and from age-eligible members of the same households. Potential participants were excluded if they were institutionalized, not ambulatory at home, under hospice care, receiving radiation or chemotherapy for cancer, not expected to remain in the area for at least 3 years, or unable to be interviewed. CHS enrolled 5201 participants in 1989 to 1990. An additional 687 black participants entered the cohort in 1992 to 1993. Participants who did not donate DNA or who did not consent to the use of their DNA for studies by private companies (n=514) as well as participants for whom the amount of DNA samples were insufficient (n=130) were excluded, leaving 5244 participants available for a genetic study. The Institutional Review Board at each site approved the study methods, and all participants gave written informed consent. Details of CHS design7 and recruitment8 have been reported.

Participants completed a baseline clinic examination that included a medical history interview, physical examination, and blood draw.9 Baseline self-reported myocardial infarction (MI) or stroke was confirmed by information from the clinic examination or by review of medical records or physician questionnaires.10 Cardiovascular events during follow-up were identified at semiannual contacts, which alternated between clinic visits and telephone calls. Suspected events were adjudicated according to standard criteria by a physician review panel using information from medical records, brain imaging studies,11 and, in some cases, interviews with the physician, participant, or a proxy informant.12 Medicare use files were searched to ascertain events that may have been missed.13

At baseline, 722 of the 5244 participants available for a genetic study had a history of stroke or MI. Because the risk of incident ischemic stroke might be influenced by whether a patient had a prior stroke or MI, these 722 participants were excluded from the analysis, leaving 4522 (3849 white and 673 black) participants in this genetic study of first incident ischemic stroke. Baseline characteristics of these 4522 participants are presented in Table 1. During follow-up, 642 participants had an incident nonprocedure-related stroke, and 47 of these 642 had an MI before their stroke, leaving 595 stroke events. Of these 595 stroke events, 72 (12%) were hemorrhagic, 46 (8%) were not classified for type, and the remaining 477 stroke events were classified as ischemic stroke events, the end point for this analysis.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of CHS Participants in This Ischemic Stroke Study

| Characteristic | Whites | Blacks |

|---|---|---|

| No. of individuals in this analysis | 3849 | 673 |

| Male | 1575 (41) | 243 (36) |

| Age, mean (SD), years | 72.7 (5.6) | 72.9 (5.7) |

| Body mass index, mean (SD), kg/m2 | 26.3 (4.5) | 28.5 (5.6) |

| Smoking, current | 423 (11) | 113 (17) |

| Diabetes | 511 (13) | 151 (23) |

| Impaired fasting glucose | 522 (14) | 92 (14) |

| Hypertension | 2110 (55) | 490 (73) |

| LDL cholesterol, mean (SD), mg/dL | 130 (36) | 129 (36) |

| HDL cholesterol, mean (SD), mg/dL | 54 (16) | 58 (15) |

| Total cholesterol, mean (SD), mg/dL | 212 (39) | 210 (39) |

Data presented as number of participants (%) unless otherwise indicated.

Covariates

Risk estimates for ischemic stroke were adjusted for the following traditional risk factors: diabetes mellitus (defined by fasting serum glucose levels of at least 126 mg/dL or the use of either insulin or oral hypoglycemic medications), impaired fasting glucose (defined as a fasting glucose levels of 110 to 125 mg/dL14), hypertension (defined by systolic blood pressure of at least 140 mm Hg, diastolic blood pressure of at least 90 mm Hg, or a physician’s diagnosis of hypertension plus the use of antihypertensive medications10), current smoking, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and body mass index. Other covariates included atrial fibrillation, carotid intima media thickness, and genotypes. Atrial fibrillation was identified on the basis of 12-lead resting electrocardiograms performed at the baseline examination. Tracings were read for atrial fibrillation or flutter at the CHS Electrocardiography Reading Center.15 Ultrasonography of the common and internal carotid arteries was also performed at baseline. The intima media thickness was defined as the mean of the maximum intima media thicknesses of the near and far walls of the left and right carotid arteries.16 Genotypes of the CHS participants were determined by a multiplex method that combines polymerase chain reaction, allele-specific oligonucleotide ligation assays, and hybridization to oligonucleotides coupled to Luminex 100TM xMAP microspheres (Luminex, Austin, Texas) followed by detection of the spectrally distinct microsphere on a Luminex 100 instrument (Supplemental text in reference 6).6

Prespecification of Risk Alleles for 74 Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms Investigated in CHS

For each of the 74 SNPs that were genotyped in CHS, we prespecified a risk allele based on antecedent data (Supplemental Table I in reference 6). For 14 of the 74 SNPs, genetic associations with CHD have been previously published.17–21 The remaining 60 SNPs were associated with MI in one or more antecedent studies of MI as described (Supplemental Text and Table II in reference 6).

Statistics

Because the risk estimate for gene variants can differ between whites and blacks, we investigated the association of SNPs with incident ischemic stroke in CHS in each race separately. We conducted analyses of time to primary end point. Follow-up began at CHS enrollment and ended on the date of incident stroke of any type, incident MI, death, loss to follow-up, or June 30, 2004, whichever occurred first. The median follow-up time was 11.2 years (11.9 years for the 1989 to 1990 cohort and 10.7 years for the black cohort).

Cox regression models were used to estimate hazard ratios of each SNP. In Model 1, Cox models were adjusted for baseline age (continuous) and sex. In Model 2, Cox models were adjusted for baseline age (continuous), sex, body mass index (continuous), current smoking, diabetes, impaired fasting glucose, hypertension, LDL cholesterol (continuous), and HDL cholesterol (continuous). Risk estimates were also further adjusted for 2 additional risk factors of ischemic stroke: atrial fibrillation and carotid intima media thickness. The SNP variable in the Cox models was coded as 0 for the nonrisk homozygote, 1 for those who carried one copy of the risk allele, and 2 for those who carried 2 copies of the risk allele. Thus, the hazard ratios represent the log-additive increase in risk for each additional copy of the risk allele a subject carried compared with the nonrisk homozygotes. Because we were testing the hypotheses that the allele associated with increased risk of CHD would also be associated with increased risk of ischemic stroke, we used a one-sided probability value to test the significance of the Cox model coefficients. Correspondingly, we estimated 90% CIs for the hazard ratios (for hazard ratios greater than one, there is 95% confidence that a true risk estimate is greater than the lower bound of a 90% CI). In white participants, this study had 80% or more power to detect associations between SNPs and incident ischemic stroke for SNPs that have relative risks of 1.3 and 1.5 (in an additive model) and risk allele frequencies of 0.13 and 0.05, respectively, assuming an alpha level of 0.05 and a one-sided test. In black participants, this study had 80% or more power to detect associations between SNPs and incident ischemic stroke for SNPs that have relative risks of 1.6 and 1.8 (in an additive model) and risk allele frequencies of 0.3 and 0.14, respectively. The cumulative incidence of stroke was estimated by the method of Kaplan and Meier. Data were analyzed using Stata Statistical Software.22

The influence of multiple testing was evaluated using the false discovery rate (FDR)23 to estimate the expected fraction of false-positives in a group of SNPs with probability values below a given threshold. An FDR of 1 would indicate that all the nominally associated results are expected to be false discoveries, and an FDR of 0 would indicate that none of the nominally associated results are expected to be false discoveries. FDR calculations were performed with R Statistical Software.24

Results

The baseline characteristics of the 3849 white and 673 black participants of CHS in this genetic study of ischemic stroke are presented in Table 1. There were 407 first incident ischemic stroke events in the white participants and 70 in the black participants during follow-up (median of 11.2 years). We investigated the association between incident ischemic stroke and 74 SNPs that had previously been found to be associated with CHD in one or more antecedent studies.6 Specifically, for each SNP, we asked if the allele that had been associated with increased risk of CHD (the risk allele) was also associated with increased risk of stroke.

In white participants of CHS, we found that the risk alleles of 7 of these 74 SNPs were nominally associated (P<0.05) with increased risk of stroke after adjusting for traditional risk factors (age, sex, body mass index, smoking, diabetes, impaired fasting glucose, hypertension, LDL cholesterol, and HDL cholesterol). These 7 SNPs were in HPS1, ITGAE, ABCG2, MYH15, FSTL4, CALM1, and BAT2. The additive (per allele) hazard ratios for stroke ranged from 1.15 to 1.49 (Table 2). In black participants of CHS, we found that the risk alleles of 5 SNPs (in KRT4, LY6G5B, EDG1, DMXL2, and ABCG2) were nominally associated (P<0.05) with increased risk of stroke after adjusting for traditional risk factors. The hazard ratios for these 5 SNPs ranged from 1.40 to 3.59 (Table 3). The risk estimates for the 11 SNPs that were associated with stroke in either whites or blacks (Tables 2 and 3) were essentially unchanged when further adjusted for atrial fibrillation and internal carotid artery intima media thickness (data not shown). The associations between incident ischemic stroke and all 74 SNPs are shown in Supplemental Table, available online at http://stroke.ahajournals.org.

Table 2.

Gene Variants Associated With Incident Ischemic Stroke in White Participants of CHS

| Gene | dbSNP ID | Risk Allele* | Allele Frequency† | HR‡ (90% CI) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HPS1 | rs1804689 | T | 0.30 | 1.23 (1.09–1.40) | 0.003 |

| ITGAE | rs220479 | C | 0.82 | 1.26 (1.08–1.48) | 0.008 |

| ABCG2 | rs2231137 | C | 0.95 | 1.46 (1.05–2.03) | 0.03 |

| MYH15 | rs3900940 | C | 0.29 | 1.15 (1.02–1.31) | 0.03 |

| FSTL4 | rs13183672 | A | 0.76 | 1.17 (1.01–1.35) | 0.04 |

| CALM1 | rs3814843 | G | 0.05 | 1.31 (1.02–1.68) | 0.04 |

| BAT2 | rs11538264 | G | 0.97 | 1.49 (1.02–2.16) | 0.04 |

Risk allele was defined to be the CHD risk allele as described in Supplemental Table 1 in reference 6.

Frequency of the risk allele in white participants of CHS.

Hazard ratios (HRs) are adjusted for baseline age, sex, body mass index, current smoking, diabetes, impaired fasting glucose, hypertension, LDL cholesterol, and HDL cholesterol at baseline. HRs are per copy of the risk allele.

Table 3.

Gene Variants Associated With Incident Ischemic Stroke in Black Participants of CHS

| Gene | dbSNP ID | Risk Allele* | Allele Frequency† | HR‡ (90% CI) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KRT4 | rs89962 | T | 0.11 | 2.08 (1.48–2.94) | <0.001 |

| LY6G5B | rs11758242 | C | 0.89 | 2.28 (1.20–4.33) | 0.02 |

| EDG1 | rs2038366 | G | 0.74 | 1.59 (1.08–2.35) | 0.02 |

| DMXL2 | rs12102203 | G | 0.47 | 1.40 (1.03–1.90) | 0.04 |

| ABCG2 | rs2231137 | C | 0.95 | 3.59 (1.11–11.7) | 0.04 |

Risk allele was defined to be the CHD risk allele as described in Supplemental Table 1 in reference 6.

Frequency of the risk allele in black participants of CHS.

Hazard ratios (HRs) are adjusted for baseline age, sex, body mass index, current smoking, diabetes, impaired fasting glucose, hypertension, LDL cholesterol, and HDL cholesterol at baseline. HRs are per copy of the risk allele.

To account for multiple comparisons, we estimated the FDR23 for the set of SNPs found to be nominally associated with incident ischemic stroke in CHS participants. These FDRs were 0.42 for the 7 SNPs in white and 0.55 for the 5 SNPs in black participants of CHS.

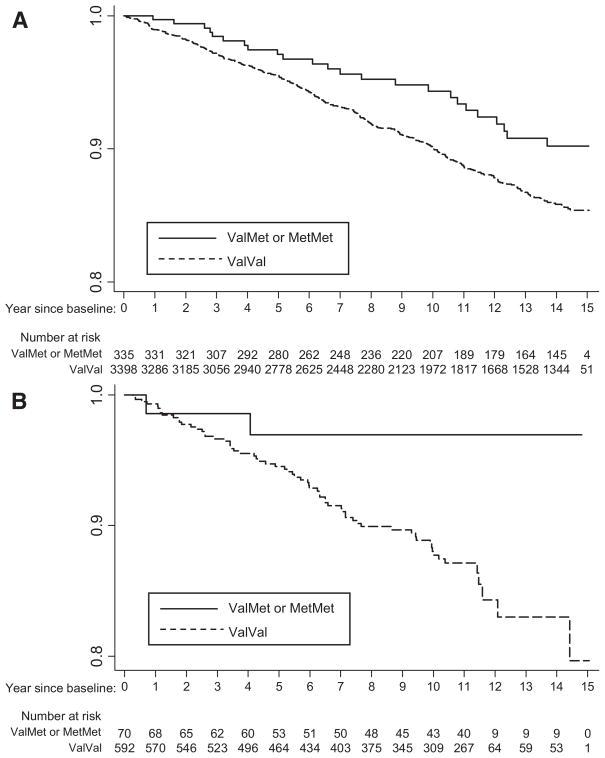

ABCG2 Val12Met (rs2231137) was the only SNP associated with incident ischemic stroke in both white and black participants of CHS. The risk of ischemic stroke was higher in Val allele homozygotes than in Met allele carriers. The adjusted hazard ratio for Val allele homozygotes, compared with Met allele carriers, was 1.50 (90% CI, 1.06 to 2.12) in whites and 3.62 (90% CI, 1.11 to 11.9) in black participants (Table 4). The 10-year cumulative incidence of ischemic stroke was greater in Val allele homozygotes than in Met allele carriers in both the white (10% versus 6%) and black (12% versus 3%; Figure) participants of CHS.

Table 4.

The Val Allele Homozygotes of ABCG2 Val12Met, Compared With the Met Allele Carriers Are Associated With Increased Risk of Incident Ischemic Stroke in Both White and Black Participants of CHS

| ABCG2 Genotype | Events, n | Total, n | Model 1* |

Model 2* |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (90% CI) | P | HR (90% CI) | P | ||||

| White | ValVal | 370 | 3398 | 1.58 (1.12–2.23) | 0.02 | 1.50 (1.06–2.12) | 0.03 |

| ValMet+MetMet | 24 | 335 | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | |||

| ValMet | 23 | 321 | |||||

| MetMet | 1 | 14 | |||||

| Black | ValVal | 66 | 592 | 3.80 (1.16–12.4) | 0.03 | 3.62 (1.11–11.9) | 0.04 |

| ValMet+MetMet | 2 | 70 | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | |||

| ValMet | 2 | 69 | |||||

| MetMet | 0 | 1 | |||||

Model 1 was adjusted for baseline age and sex. Model 2 was adjusted for baseline age, sex, body mass index, current smoking, diabetes, impaired fasting glucose, hypertension, LDL cholesterol, and HDL cholesterol.

Figure.

Comparison of Kaplan-Meier estimates of the cumulative incidence of ischemic stroke among Val allele homozygotes of the ABCG2 Val12Met and among Met allele carriers in white (A) and in black (B) participants of CHS.

Discussion

Among 74 genetic variants tested in CHS, we found that 7 were nominally associated with incident ischemic stroke in white participants and 5 were nominally associated with incident ischemic stroke in black participants. The FDRs of 0.42 (for the set of 7 associated SNPs in whites) and 0.55 (for the set of 5 associated SNPs in blacks) suggest that some of these nominally associated SNPs are true-positives. The most notable finding, consistent in both whites and blacks, was the association between the Val allele of ABCG2 Val12Met and increased risk of incident ischemic stroke.

Three of the 11 gene variants nominally associated with incident ischemic stroke in CHS had particularly notable associations with CHD in the antecedent studies. The first of these 3 gene variants was the Val allele of ABCG2 Val12Met (rs2231137). This gene variant had previously been found to be associated with angiographically defined severe coronary artery disease in 2 case–control studies.20

ABCG2 encodes the ATP-binding cassette, subfamily G, member 2, which is a protein that belongs to a large family of transporters. It is expressed on the cell surface of stem cells in bone marrow and skeletal muscle,25 progenitor endothelial cells that are capable of vasculogenesis in adipose tissue,26 and endothelial cells in blood vessels of the heart27 and brain.28 The ABCG2 protein has been reported recently to transport sterols.29,30 It is interesting to note that the related ATP-binding cassette proteins ABCA1,31 ABCG5, and ABCG832 are transporters of lipids; variants of these transporters have been shown to cause lipid disorders such as Tangier disease31 and sitosterolemia.32 However, a well-known function of the ABCG2 protein is to act as a multidrug transporter of anticancer drugs, and the ABCG2 protein is overexpressed in drug-resistant cancer cells.33 The Met variant of ABCG2 has been reported to confer lower drug resistance and have altered pattern of localization when compared with the Val variant.34 We speculate that the Met variant of the ABCG2 protein may function in the vascular endothelium and have an altered function as a transporter. Homozygotes of the Val allele of ABCG2 (88% of whites and 88% of blacks) were at higher risk of stroke than carriers of the Met allele in CHS. Because there were only 16 homozygotes of the Met allele, the Met homozygotes were pooled with heterozygotes and used as the reference group. The Met allele could also be considered to be a protective allele in that the Met allele carriers had a lower risk of incident ischemic stroke than the Val allele homozygotes.

The second of the 3 gene variants with notable findings in antecedent studies is the Ala allele of MYH15 Thr1125Ala (rs3900940). In addition to being associated with MI in 2 antecedent association studies,6 it was associated with increased risk of incident CHD in the white participants of the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study.21 MYH15 encodes myosin heavy polypeptide 15 and the Thr1125Ala SNP is located in the tail domain of the MYH15 protein.35 It is not clear how MYH15 might be involved in vascular biology or how the Ala substitution in MYH15 affects the risk of vascular disease.

The third gene variant with notable findings in antecedent studies is the G allele of rs3814843 in the 3′ untranslated region in CALM1. This SNP was associated with angiographically defined severe coronary artery disease in 2 case–control studies.20 CALM1 encodes calmodulin 1, which binds calcium and functions in diverse signaling pathways, including those involved in cell division,36 membrane trafficking,37 and platelet aggregation.38 The functional consequence of the rs3814843 SNP in the CALM1 gene remains to be investigated.

Potential limitations of this study include the advanced age of CHS participants, who were ≥65 at enrollment; genetic association results obtained in the CHS cohort may have been affected by survival bias. Additionally, because CHD was the end point in the antecedent studies, variants that are associated with stroke but not with CHD would not have been tested in this study. Although the 74 SNPs investigated in this study had been found to be associated with CHD in antecedent studies and 16 of these 74 SNPs had also been found to be associated with MI in either the white or black participants of CHS,6 none of these 16 SNPs were associated with stroke in CHS. Although the failure to identify SNPs that were associated with both MI and stroke in CHS could be a reflection of genetic risk factor that differ between MI and stroke, it could also result from low power to detect associations in CHS. Finally, a fraction of the 74 SNPs we tested may have been false-positives in the antecedent studies of CHD.

Summary

In conclusion, we found that a subset of gene variants previously associated with CHD in antecedent studies were also associated with incident ischemic stroke in CHS; however, in CHS, none of these SNPs were associated with both MI and stroke. Notably, the Val allele of the Val12Met SNP in ABCG2 (which encodes a transporter of sterols and anticancer drugs) was associated with increased risk of incident ischemic stroke in both white and black participants of CHS. Nevertheless, results from this study should be further validated in other populations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the CHS participants. A full list of participating CHS investigators and institutions can be found at www.chs-nhlbi.org.

Sources of Funding

The research reported in this article was supported in part by contracts N01-HC-35129, N01-HC-45133, N01-HC-75150, N01-HC-85079 through N01-HC-85086, N01 HC-15103, N01 HC-55222, and U01 HL080295 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute with additional contribution from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. The genotyping was carried out in the genotyping core laboratory at Celera. The statistical analyses presented in this article were conducted at the University of Washington and were funded, in part, by Celera.

Footnotes

The online version of this article, along with updated information and services, is located on the World Wide Web at: http://stroke.ahajournals.org/cgi/content/full/40/2/363

Disclosures

M.M.L., C.M.R., D.S., L.A.B., A.R.A., and J.J.D. are employees with ownership interest in Celera and have contributed to the study design, interpretation of data, and writing of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Brass LM, Isaacsohn JL, Merikangas KR, Robinette CD. A study of twins and stroke. Stroke. 1992;23:221–223. doi: 10.1161/01.str.23.2.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bak S, Gaist D, Sindrup SH, Skytthe A, Christensen K. Genetic liability in stroke: a long-term follow-up study of Danish twins. Stroke. 2002;33:769–774. doi: 10.1161/hs0302.103619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Welin L, Svardsudd K, Wilhelmsen L, Larsson B, Tibblin G. Analysis of risk factors for stroke in a cohort of men born in 1913. N Engl J Med. 1987;317:521–526. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198708273170901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jousilahti P, Rastenyte D, Tuomilehto J, Sarti C, Vartiainen E. Parental history of cardiovascular disease and risk of stroke. A prospective follow-up of 14 371 middle-aged men and women in Finland. Stroke. 1997;28:1361–1366. doi: 10.1161/01.str.28.7.1361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rosamond W, Flegal K, Friday G, Furie K, Go A, Greenlund K, Haase N, Ho M, Howard V, Kissela B, Kittner S, Lloyd-Jones D, McDermott M, Meigs J, Moy C, Nichol G, O’Donnell CJ, Roger V, Rumsfeld J, Sorlie P, Steinberger J, Thom T, Wasserthiel-Smoller S, Hong Y. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2007 update: a report from the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Circulation. 2007;115:e69–171. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.179918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shiffman D, O’Meara ES, Bare LA, Rowland CM, Louie JZ, Arellano AR, Lumley T, Rice K, Iakoubova O, Luke MM, Young BA, Malloy MJ, Kane JP, Ellis SG, Tracy RP, Devlin JJ, Psaty BM. Association of gene variants with incident myocardial infarction in the Cardiovascular Health Study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28:173–179. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.153981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fried LP, Borhani NO, Enright P, Furberg CD, Gardin JM, Kronmal RA, Kuller LH, Manolio TA, Mittelmark MB, Newman A, et al. The Cardiovascular Health Study: design and rationale. Ann Epidemiol. 1991;1:263–276. doi: 10.1016/1047-2797(91)90005-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tell GS, Fried LP, Hermanson B, Manolio TA, Newman AB, Borhani NO. Recruitment of adults 65 years and older as participants in the Cardiovascular Health Study. Ann Epidemiol. 1993;3:358–366. doi: 10.1016/1047-2797(93)90062-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cushman M, Cornell ES, Howard PR, Bovill EG, Tracy RP. Laboratory methods and quality assurance in the Cardiovascular Health Study. Clin Chem. 1995;41:264–270. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Psaty BM, Kuller LH, Bild D, Burke GL, Kittner SJ, Mittelmark M, Price TR, Rautaharju PM, Robbins J. Methods of assessing prevalent cardiovascular disease in the Cardiovascular Health Study. Ann Epidemiol. 1995;5:270–277. doi: 10.1016/1047-2797(94)00092-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Longstreth WT, Jr, Bernick C, Fitzpatrick A, Cushman M, Knepper L, Lima J, Furberg CD. Frequency and predictors of stroke death in 5888 participants in the Cardiovascular Health Study. Neurology. 2001;56:368–375. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.3.368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Price TR, Psaty B, O’Leary D, Burke G, Gardin J. Assessment of cerebrovascular disease in the Cardiovascular Health Study. Ann Epidemiol. 1993;3:504–507. doi: 10.1016/1047-2797(93)90105-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ives DG, Fitzpatrick AL, Bild DE, Psaty BM, Kuller LH, Crowley PM, Cruise RG, Theroux S. Surveillance and ascertainment of cardiovascular events. The Cardiovascular Health Study. Ann Epidemiol. 1995;5:278–285. doi: 10.1016/1047-2797(94)00093-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.American Diabetes Association. Report of the Expert Committee on the Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes Care. 1997;20:1183–1197. doi: 10.2337/diacare.20.7.1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rautaharju PM, MacInnis PJ, Warren JW, Wolf HK, Rykers PM, Calhoun HP. Methodology of ECG interpretation in the Dalhousie program; NOVACODE ECG classification procedures for clinical trials and population health surveys. Methods Inf Med. 1990;29:362–374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.O’Leary DH, Polak JF, Wolfson SK, Jr, Bond MG, Bommer W, Sheth S, Psaty BM, Sharrett AR, Manolio TA. Use of sonography to evaluate carotid atherosclerosis in the elderly. The Cardiovascular Health Study. CHS Collaborative Research Group. Stroke. 1991;22:1155–1163. doi: 10.1161/01.str.22.9.1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shiffman D, Ellis SG, Rowland CM, Malloy MJ, Luke MM, Iakoubova OA, Pullinger CR, Cassano J, Aouizerat BE, Fenwick RG, Reitz RE, Catanese JJ, Leong DU, Zellner C, Sninsky JJ, Topol EJ, Devlin JJ, Kane JP. Identification of four gene variants associated with myocardial infarction. Am J Hum Genet. 2005;77:596–605. doi: 10.1086/491674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shiffman D, Rowland CM, Louie JZ, Luke MM, Bare LA, Bolonick JI, Young BA, Catanese JJ, Stiggins CF, Pullinger CR, Topol EJ, Malloy MJ, Kane JP, Ellis SG, Devlin JJ. Gene variants of VAMP8 and HNRPUL1 are associated with early-onset myocardial infarction. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:1613–1618. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000226543.77214.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Iakoubova OA, Tong CH, Chokkalingam AP, Rowland CM, Kirchgessner TG, Louie JZ, Ploughman LM, Sabatine MS, Campos H, Catanese JJ, Leong DU, Young BA, Lew D, Tsuchihashi Z, Luke MM, Packard CJ, Zerba KE, Shaw PM, Shepherd J, Devlin JJ, Sacks FM. Asp92Asn polymorphism in the myeloid IgA Fc receptor is associated with myocardial infarction in two disparate populations: CARE and WOSCOPS. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:2763–2768. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000247248.76409.8b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Luke MM, Kane JP, Liu DM, Rowland CM, Shiffman D, Cassano J, Catanese JJ, Pullinger CR, Leong DU, Arellano AR, Tong CH, Movsesyan I, Naya-Vigne J, Noordhof C, Feric NT, Malloy MJ, Topol EJ, Koschinsky ML, Devlin JJ, Ellis SG. A polymorphism in the protease-like domain of apolipoprotein(a) is associated with severe coronary artery disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27:2030–2036. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.141291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bare LA, Morrison AC, Rowland CM, Shiffman D, Luke MM, Iakoubova OA, Kane JP, Malloy MJ, Ellis SG, Pankow JS, Willerson JT, Devlin JJ, Boerwinkle E. Five common gene variants identify elevated genetic risk for coronary heart disease. Genet Med. 2007;9:682–689. doi: 10.1097/gim.0b013e318156fb62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stata Statistical Software: Release 9. College Station, TX: Stata Corp; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a new and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc B. 1995:1289–1300. [Google Scholar]

- 24.R Development Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing, reference index version 2.3.0. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhou S, Schuetz JD, Bunting KD, Colapietro AM, Sampath J, Morris JJ, Lagutina I, Grosveld GC, Osawa M, Nakauchi H, Sorrentino BP. The ABC transporter Bcrp1/ABCG2 is expressed in a wide variety of stem cells and is a molecular determinant of the side-population phenotype. Nat Med. 2001;7:1028–1034. doi: 10.1038/nm0901-1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miranville A, Heeschen C, Sengenes C, Curat CA, Busse R, Bouloumie A. Improvement of postnatal neovascularization by human adipose tissue-derived stem cells. Circulation. 2004;110:349–355. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000135466.16823.D0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meissner K, Heydrich B, Jedlitschky G, Meyer Zu Schwabedissen H, Mosyagin I, Dazert P, Eckel L, Vogelgesang S, Warzok RW, Bohm M, Lehmann C, Wendt M, Cascorbi I, Kroemer HK. The ATP-binding cassette transporter ABCG2 (BCRP), a marker for side population stem cells, is expressed in human heart. J Histochem Cytochem. 2006;54:215–221. doi: 10.1369/jhc.5A6750.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang W, Mojsilovic-Petrovic J, Andrade MF, Zhang H, Ball M, Stanimirovic DB. The expression and functional characterization of ABCG2 in brain endothelial cells and vessels. Faseb J. 2003;17:2085–2087. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-1131fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Janvilisri T, Venter H, Shahi S, Reuter G, Balakrishnan L, van Veen HW. Sterol transport by the human breast cancer resistance protein (ABCG2) expressed in Lactococcus lactis. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:20645–20651. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301358200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Janvilisri T, Shahi S, Venter H, Balakrishnan L, van Veen HW. Arginine-482 is not essential for transport of antibiotics, primary bile acids and unconjugated sterols by the human breast cancer resistance protein (ABCG2) Biochem J. 2005;385:419–426. doi: 10.1042/BJ20040791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oram JF. Tangier disease and ABCA1. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1529:321–330. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(00)00157-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schmitz G, Langmann T, Heimerl S. Role of ABCG1 and other ABCG family members in lipid metabolism. J Lipid Res. 2001;42:1513–1520. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maliepaard M, van Gastelen MA, de Jong LA, Pluim D, van Waardenburg RC, Ruevekamp-Helmers MC, Floot BG, Schellens JH. Overexpression of the BCRP/MXR/ABCP gene in a topotecan-selected ovarian tumor cell line. Cancer Res. 1999;59:4559–4563. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mizuarai S, Aozasa N, Kotani H. Single nucleotide polymorphisms result in impaired membrane localization and reduced ATPase activity in multidrug transporter ABCG2. Int J Cancer. 2004;109:238–246. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Desjardins PR, Burkman JM, Shrager JB, Allmond LA, Stedman HH. Evolutionary implications of three novel members of the human sarcomeric myosin heavy chain gene family. Mol Biol Evol. 2002;19:375–393. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a004093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moisoi N, Erent M, Whyte S, Martin S, Bayley PM. Calmodulin-containing substructures of the centrosomal matrix released by micro-tubule perturbation. J Cell Sci. 2002;115:2367–2379. doi: 10.1242/jcs.115.11.2367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tyteca D, van Ijzendoorn SC, Hoekstra D. Calmodulin modulates hepatic membrane polarity by protein kinase C-sensitive steps in the basolateral endocytic pathway. Exp Cell Res. 2005;310:293–302. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2005.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Oury C, Sticker E, Cornelissen H, De Vos R, Vermylen J, Hoylaerts MF. ATP augments von Willebrand factor-dependent shear-induced platelet aggregation through Ca2+-calmodulin and myosin light chain kinase activation. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:26266–26273. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M402032200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.