Abstract

Objectives

Clinical response is typically observed in most adults with celiac disease (CD) after treatment with a gluten-free diet (GFD). The rate of mucosal recovery is less certain. The aims of this study were 1) to estimate the rate of mucosal recovery after GFD in a cohort of adults with CD, and 2) to assess the clinical implications of persistent mucosal damage after GFD.

Methods

The study group included adults with biopsy-proven CD evaluated at the Mayo Clinic who had duodenal biopsies at diagnosis and at least one follow-up intestinal biopsy to assess mucosal recovery after starting a GFD. The primary outcomes of interest were mucosal recovery and all-cause mortality.

Results

Of 381 adults with biopsy-proven CD, 241 (73% females) had both a diagnostic and follow-up biopsy available for re-review. Among these 241, the Kaplan-Meier rate of confirmed mucosal recovery at 2 years following diagnosis was 34% (95% CI: 27%–40%), and at 5 years was 66% (95% CI: 58%–74%). Most patients (82%) had some clinical response to GFD, but it was not a reliable marker of mucosal recovery (p=0.7). Serological response was associated with confirmed mucosal recovery (p=0.01). Poor compliance to GFD (p<.01), severe CD defined by diarrhea and weight loss (p<.001), and total villous atrophy at diagnosis (p<.001) were strongly associated with persistent mucosal damage. There was a trend toward an association between achievement of mucosal recovery and a reduced rate of all-cause mortality (HR = 0.13, 95% CI: 0.02–1.06, p = .06), adjusted for gender and age.

Conclusions

Mucosal recovery was absent in a substantial portion of adults with CD after treatment with a GFD. There was a borderline significant association between confirmed mucosal recovery (vs. persistent damage) and reduced mortality independent of age and gender. Systematic follow-up with intestinal biopsies may be advisable in patients diagnosed with CD as adults.

Keywords: cancer, celiac disease, mortality, prevalence, serology: sprue, antibodies

Introduction

Celiac disease (CD) is triggered by the ingestion of gluten present in cereals such as wheat, barley and rye in genetically-susceptible individuals.1 While severe complications can develop if unrecognized and untreated, a gluten-free diet (GFD) is an effective treatment that can alleviate symptoms and normalize antibodies and the intestinal mucosa in patients with CD.2, 3

Substantial clinical response is observed in most patients with CD after only a few weeks on a GFD. 4 However, mucosal recovery does not occur in all patients with CD in whom complete clinical response is achieved.5, 6 Also, there are asymptomatic cases of CD in the presence of severe mucosal damage.7

Up to 95% of CD diagnosed during childhood may have complete intestinal mucosal recovery within 2 years after starting a GFD.8 The rate of mucosal recovery after treatment with a GFD in adults with CD is less certain.5, 6, 9 10–12 Complete recovery of the intestinal mucosa in adults with CD may be obtainable, but often requires longer than 12 months of strict adherence to GFD.2, 13 Besides the obvious issue of poor adherence to GFD, other factors involved in persistence of intestinal damage in adults with treated CD are less clear.14 Documentation of mucosal recovery after treatment with a GFD may be clinically relevant because persistent mucosal damage appears to increase the risk of severe complications in patients with CD, even in the absence of symptoms.15 Persistent mucosal villous atrophy without symptoms has not been traditionally considered within the spectrum of refractory celiac disease (RCD), a rare condition characterized by severe malabsorption and persistent villous atrophy despite strict adherence to GFD.16–18 However, a minority of patients with treated CD, without symptoms but with persistent mucosal villous atrophy, may develop overt RCD or other complications over time.15

Diagnosed clinically-detected CD carries a modestly increased risk of mortality mainly attributable to malignancies, though strict adherence to a GFD may reduce this risk.19, 20 21–24 Two studies have suggested a significantly increased risk of mortality over time in patients with undiagnosed CD.25, 26 However, the association of undiagnosed CD with increased mortality is not universal nor is the association with increased malignancy.27, 28 Recently, a large study from Sweden demonstrated an elevated risk of death among patients with CD (Marsh stage 3), duodenal inflammation (Marsh stage 1–2) or latent CD, the latter defined as positive celiac serology in individuals with normal mucosa (Marsh stage 0).29, 30 The effect of persistent mucosal damage, despite treatment with a GFD, on “hard” outcomes (e.g., mortality) is unknown, as are the clinical factors associated with rate of mucosal recovery. It can be hypothesized that 1) persistent mucosal damage in adults with treated CD can in some cases lead to an increased risk of death over time, and 2) there are clinical factors that may be associated with a reduced rate of mucosal recovery.

The aims of the study are 1) to estimate the rate of mucosal recovery in response to a GFD in adults with biopsy-proven CD, 2) to identify clinical factors associated with persistent mucosal damage, and 3) to determine whether the persistence of mucosal damage after treatment with a GFD in adults with CD is associated with increased mortality.

Material and Methods

Subjects

The study group included only adults (age ≥18 years old) with biopsy-proven CD evaluated at the Mayo Clinic prior to 2008 who had duodenal biopsies at diagnosis and at least one follow-up intestinal biopsy to assess mucosal recovery after 5 months or more of diagnosis.

Data abstraction

Clinical data were retrospectively abstracted from the medical record. In the collection of data, clinical and laboratory data were abstracted from the medical record and listed according to either the date when the baseline (diagnostic) biopsy was taken or at the time of the first follow-up or subsequent biopsies. Compliance to the GFD was evaluated by review of dietary history obtained by a dietitian experienced in CD.14 The dietitian assessment closest to the time of the follow-up biopsies was used to grade compliance as follows: 1 = no evidence of gluten ingestion, 2 = rarely non-compliant, 3 = occasionally non-compliant, 4 = intermittently non-compliant and 5 = non-compliant. Using the previous scale, compliance to the GFD was summarized as follows: good (grades 1 or 2), moderate (grade 3), and poor (grades 4 or 5). Additionally, the causes of histological non-response were reviewed. Multiple mucosal biopsies from the distal part of the duodenum (4–6 biopsy specimens) were obtained in all patients, as previously recommended.1, 2 Pathology material (consisting largely of endoscopic biopsies from the small bowel) was re-reviewed in a standardized fashion. Histological lesions were classified according to the modified Marsh classification31, 32 using the worst histologic finding observed in the slide to characterize the lesion. Additional histologic parameters were systematically evaluated: the villous to crypt ratio and the percentage of intraepithelial lymphocytes (IELs) per 100 epithelial cells (normal cut-off: <40%).31, 32

Criteria of response to treatment with a gluten-free diet

Clinical

To clearly describe the clinical course of CD after gluten withdrawal, some arbitrary a priori definitions were used. “Clinical response” was defined as “complete” in the absence of diarrhea or any evidence of the presenting symptoms and “partial” when some clinical improvement was documented after treatment with a GFD but without return to normality.

Serological

Serological response was defined as a negative tTGA result and/or EMA result at follow-up (either seroconversion when positive serology was documented at diagnosis or simply a negative serologic test at follow-up when serology at diagnosis was unavailable).

Histological

“Mucosal recovery” was defined by a villous to crypt ratio of 3 to 1 or higher based on the average ratio previously reported in non-celiac control subjects and the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) Technical Review on Celiac Sprue recommendations.2 13 The number of IELs per 100 epithelial cells was not considered criteria for mucosal recovery because 1) the finding is nonspecific and other environmental factors unrelated to CD may cause intraepithelial lymphocytosis,33, 34 and 2) reduction of IELs (specially γδ+ population) after treatment with a GFD can take years to occur.35, 36 However, intraepithelial lymphocytosis (defined as >40 IELs per 100 epithelial nuclei)31, 32 was documented when present. “Histological improvement” was arbitrarily defined by an increase of villous to crypt ratio ≥2.0 points in the follow-up biopsy with respect to the baseline.

Statistical analysis

Data were summarized by descriptive statistics, including counts and percentages for categorical data and medians and ranges for continuous parameters. For data collected around the time of first follow-up biopsy, patients with confirmed mucosal recovery were compared to those with persistent damage. In particular, continuous data was compared between groups using a Wilcoxon Rank Sum Test, while categorical data was compared using Chi-Square Test or Fisher’s Exact Test as appropriate. Ordinal data was tested for a linear trend in the binary proportions using a Cochran-Armitage Trend Test. Data measured repeatedly within subjects was tested for a significant change from time of diagnosis to first follow-up biopsy using Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test for continuous data, and McNemar’s Test for categorical data. In addition, the Kaplan-Meier (KM) method was used to estimate overall survival and rate of mucosal recovery from time of diagnostic biopsy. Cox proportional hazards regression was used to test for association between clinical factors and time-to-mucosal recovery, and between mucosal recovery and overall survival. For the latter, a multivariable model was fit including age and gender as adjusting covariates, and mucosal recovery as a time-dependent variable. Furthermore, to include all patients (even those without diagnostic or follow-up biopsy information) so as to reduce chance of selection bias, a category of unknown mucosal recovery was appropriately designated and defined in the model. An adjusted hazard ratio and 95% confidence interval (CI) are reported to summarize the risk of death in patients with confirmed mucosal recovery relative to those with confirmed persistent damage. A P-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were carried out using SAS (version 8.2, SAS Institute, Cary, NC) or Splus (version 8.0, Insightful, Seattle, WA) software packages.

Ethical issues

This study was approved by the institutional review board of the Mayo Clinic.

Results

Patients

Three-hundred-eighty-one adults with CD seen in the Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology at Mayo Clinic prior to 2008 were considered for inclusion. Of these, 73 patients did not have the diagnostic intestinal biopsy available for re-review and an additional 67 did not have a follow-up biopsy performed during their clinical follow-up. Thus, for most analyses, we included only the 241 patients with both diagnostic and follow-up biopsy data available. The cohort of 241 CD patients was predominately female (n=176, 73%) with a median (range) age at CD diagnosis of 47 years (18–84). Approximately two-thirds (n=162, 67%) of patients had one follow-up biopsy, while the remaining one-third (n=79, 33%) of patients had more than one (range, 2 – 8). Clinical presentation of CD was classical in 157 (65%) patients, atypical in 76 (32%) patients, and silent in 8 (3%) patients. Severe CD (defined by the presence of diarrhea and weight loss) was present in 87 (36%) patients. Among the 239 of 241 patients with a diagnostic biopsy prior to GFD, all had some degree of intestinal villous atrophy (Marsh type 3), and nearly half (n=118, 49%) had total villous atrophy. The biopsy showed partial villous atrophy in 2 patients in whom the confirmatory biopsy was taken after the onset of non-medical supervised GFD for 9 and 28 months, respectively. Serology results at the time of CD diagnosis was available for a subset of the 241 patients, including 110 (46%) with an anti-tissue transglutaminase antibodies (tTGA) result and 116 (48%) with an endomysial antibodies (EMA) result. Among the 110 tTGA-tested patients, 93 (85%) were positive with a median (range) titer of 83 U (20–250). For the 116 patients with an EMA result at time of diagnosis, 89 (77%) tested positive with a median (range) titer of 1:160 (1:5–1:2560). Among the 27 patients who tested EMA negative, most were found to have partial villous atrophy (n=23, 85%). Overall, a total of 160 (66%) had either tTGA or EMA at the time of CD diagnosis, of whom 126 (79%) tested positive. Autoimmune diseases other than CD were observed in 21% of patients. These conditions included either hypothyroidism (n=16), dermatitis herpetiformis (n=11), hyperthyroidism (n=8), type 1 diabetes mellitus (n=6), Crohn’s disease (n=2), autoimmune hepatitis (n=1), or ulcerative colitis (n=1). In addition, some patients had multiple autoimmune disorders including hypothyroidism with either dermatitis herpetiformis (n=2), hepatitis (n=1), or lupus (n=1). (Table 1)

Table 1.

Summary of Cohort at Time of CD Diagnosis

| Variable | Total (n=241) |

|---|---|

| Age at CD diagnosis* | 47 (18, 84) |

| Gender | |

| . Male | 65 (27%) |

| . Female | 176 (73%) |

| Decade of CD diagnosis | |

| . 1970s | 2 (1%) |

| . 1980s | 6 (2%) |

| . 1990s | 47 (20%) |

| . 2000s | 186 (77%) |

| Clinical presentation | |

| . Classical | 157 (65%) |

| . Atypical | 76 (32%) |

| . Silent | 8 (3%) |

| Diarrhea | 157 (65%) |

| Weight loss | 109 (45%) |

| Severe CD | 87 (36%) |

| Autoimmune disease | 49 (21%) |

| Positive tTGA at CD diagnosis | 93/110 (85%) |

| tTGA titer at CD diagnosis* | 83 (20, 250) |

| Positive EMA at CD diagnosis | 89/116 (77%) |

| EMA titer at CD diagnosis* | 160 (5, 2560) |

| Positive tTGA or EMA at CD diagnosis | 126/160 (79%) |

| Intraepithelial lymphocytes at CD diagnosis* | 75 (20, 200) |

| Villous atrophy at CD diagnosis | |

| . Partial | 123 (51%) |

| . Total | 118 (49%) |

| Villous to crypt ratio at CD diagnosis* | 0.2 (0.0,2.0) |

Median (Min, Max)

CD, celiac disease; tTGA, tissue transglutaminase antibody; EMA, endomysial antibody

Histology at first follow-up biopsy

For all 241 patients that underwent a first follow-up biopsy to assess mucosal recovery, the time since diagnostic biopsy ranged from approximately 5 months to 35 years. Of note, 14 (6%) patients had a follow-up biopsy between 5 and 6 months after a GFD; in all others, the follow-up biopsy was taken after at least 6 months on a GFD. To determine whether rate of confirmed mucosal recovery was dependent on duration, time from diagnostic biopsy (baseline biopsy) to first follow-up biopsy was trichotomized into three categories: <2 years, 2–5 years, and >5 years. The first follow-up biopsy was taken within 2 years of diagnostic biopsy in 165 (68%) patients, between 2–5 years in 51 (21%) patients, and after 5 years in 25 (11%) patients. Among 165 patients with a first follow-up biopsy <2 years after their diagnostic biopsy, mucosal recovery was confirmed in 58 (35%) patients. Conditional on having a first follow-up biopsy 2–5 years after diagnostic biopsy, mucosal recovery was confirmed in 22 (43%) of 51 patients. Conditional on having the first follow-up biopsy >5 years after diagnostic biopsy, mucosal recovery was confirmed in 10 (40%) of 25 patients. Since the mucosal recovery rate did not significantly change across time categories (p=0.40 from Cochran-Armitage Trend Test), the mucosal recovery rate of the entire group at time of first follow-up biopsy is expressed as the overall proportion, or 37%. (Table 2)

Table 2.

Extent of Disease and Mucosal Recovery at Time of 1st Follow-Up Biopsy

| Variable | Total (n=241) |

Persistent Damage (n=151) |

Mucosal Recovery (n=90) |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time since diagnostic biopsy | 0.40α | |||

| . <2 years | 165 (68%) | 107 (71%) | 58 (64%) | |

| . 2–5 years | 51 (21%) | 29 (19%) | 22 (24%) | |

| . >5 years | 25 (10%) | 15 (10%) | 10 (11%) | |

| Clinical presentation | 0.98 | |||

| . Classical | 157 (65%) | 99 (66%) | 58 (64%) | |

| . Atypical | 76 (32%) | 47 (31%) | 29 (32%) | |

| . Silent | 8 (3%) | 5 (3%) | 3 (3%) | |

| Histological improvement | 108 (45%) | 20 (13%) | 88 (99%) | <.001 |

| Intraepithelial lymphocytes * | 40 (10, 140) | 40 (10, 140) | 20 (10, 100) | <.001 |

| Intraepithelial lymphocytes categories |

<.001α | |||

| . <30 | 83 (36%) | 26 (17%) | 57 (68%) | |

| . 30–40 | 70 (30%) | 50 (34%) | 20 (24%) | |

| . >40 | 80 (34%) | 73 (49%) | 7 (8%) | |

| Intraepithelial lymphocytosis | 80 (34%) | 73 (49%) | 7 (8%) | <.001 |

| Villous to crypt ratio * | 2.0 (0.0, 5.0) | 1.0 (0.0, 2.5) | 3.0 (0.0, 5.0) | <.001 |

| Compliance to GFD | <.01α | |||

| . Good | 156 (66%) | 89 (61%) | 67 (75%) | |

| . Moderate | 49 (21%) | 31 (21%) | 18 (20%) | |

| . Poor | 31 (13%) | 27 (18%) | 4 (4%) | |

| Clinical response at 1st f/u biopsy |

192 (82%) | 119 (81%) | 73 (83%) | 0.70 |

| Positive tTGA at 1st f/u biopsy |

55/162 (34%) | 42/100 (42%) | 13/62 (21%) | 0.01 |

| tTGA conversion† | 44/79 (56%) | 26/51 (51%) | 18/28 (64%) | 0.25 |

| tTGA response | 100/154 (65%) | 55/96 (57%) | 45/58 (78%) | 0.01 |

| Positive EMA at 1st f/u biopsy |

23/124 (19%) | 20/75 (27%) | 3/49 (6%) | <.01 |

| EMA conversion† | 36/50 (72%) | 20/32 (63%) | 16/18 (89%) | 0.05 |

| EMA response | 93/116 (80%) | 51/71 (72%) | 42/45 (93%) | 0.01 |

Median (min, max) reported; P-value from Wilcoxon Rank Sum Test

P-value from Cochran-Armitage Trend Test

% based on those who tested positive at diagnosis

GFD, gluten-free diet; tTGA, tissue transglutaminase antibody, EMA, endomysial antibody

Villous architecture

Histological improvement and mucosal recovery were confirmed in 108 (45%) and 90 (37%) patients, respectively, at the time of the first follow-up biopsy. From the 121 patients with partial villous atrophy at diagnosis, 57 (45%) had achieved mucosal recovery while the remaining 64 (55%) had persistent mucosal damage (60 with unchanged partial villous atrophy and 4 with progression to total villous atrophy). From the 118 patients with total villous atrophy at diagnosis, mucosal recovery was confirmed in 33 (28%) patients, and total villous atrophy was downgraded to partial villous atrophy in 52 (44%) patients while remaining unchanged in the other 66 (56%) patients. Clinical presentation at diagnosis of CD (i.e., classical, atypical, or silent) was not associated with mucosal recovery at the time of first follow-up biopsy after GFD (p=0.98).

Villous to crypt ratio and intraepithelial lymphocytes

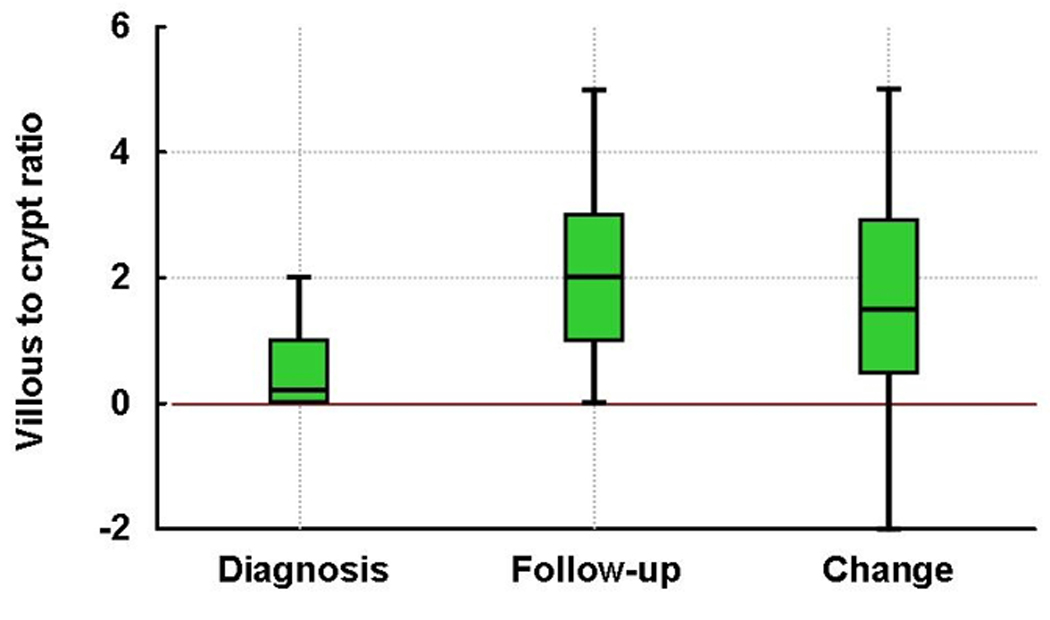

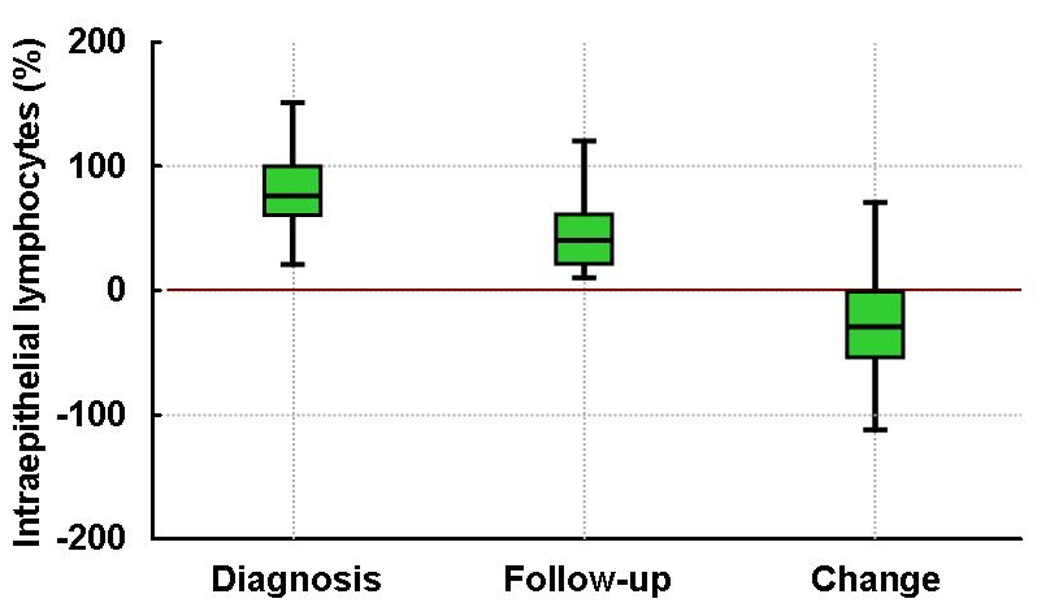

At the time of diagnostic biopsy, the median (range) villous to crypt ratio and percentage of intraepithelial lymphocytes were 0.2 (0.0–2.0) and 75 (20–200), respectively. Overall, the median (range) villous to crypt ratio and percentage of intraepithelial lymphocytes at the first follow-up biopsy were 2.0 (0.0–5.0) and 40 (10–140), respectively. The villous to crypt ratio was significantly higher at the first follow-up biopsy than at the diagnostic biopsy, while the percentage of intraepithelial lymphocytes was significantly lower (both p<.001). (Figure)

Figure.

Villous to crypt ratio and number of intraepithelial lymphocytes in adult patients with untreated and treated celiac disease: Note the significant improvement on villous to crypt ratio (Panel A) and significant decrease in the number of intraepithelial lymphocytes (Panel B) after treatment with a gluten-free diet (both p<.001). Red line is the reference for change from diagnosis to follow-up data.

Intraepithelial lymphocytosis was observed in only 7 (8%) patients with confirmed mucosal recovery at the time of the first follow-up biopsy, compared to 73 (49%) patients without confirmed mucosal recovery (p<.001).

Dietary Compliance Assessment

Assessment of compliance to GFD by dietitian interview was available in 236 (98%) patients and unknown in 5 patients. Among those assessed, compliance was good in 156 (66%) patients, moderate in 49 (21%), and poor in 31 (13%). Among the 236 patients with a known compliance status, 89 achieved mucosal recovery and 147 had persistent mucosal injury at the time of first follow-up biopsy. For those who achieved mucosal recovery, the number of patients with good, moderate, and poor compliance to GFD was 67 (75%), 18 (20%), and 4 (4%), respectively. In comparison, patients with persistent mucosal damage at first follow-up biopsy were significantly less compliant to GFD (good, moderate, and poor compliance of 61%, 21%, and 18%, respectively; p = 0.003). (Table 2)

Symptoms

Sufficient clinical data to assess symptomatic response to a GFD at the time of first follow-up biopsy were available in 235 (98%) patients. Of these, clinical response was observed in 192 (82%) patients (n=132 complete and n=60 partial) and absent in the remaining 43 (18%) patients (n=28 without mucosal recovery and n=15 with mucosal recovery). The diagnosis of CD was supported in the 28 patients with characteristic histology of CD but without both clinical and histological response to GFD by the presence of positive serology sometime during clinical evolution (n=21) or HLA-DQ2 (n=19) or else biopsy-proven dermatitis herpetiformis (n=2) and the absence of any alternative cause of villous atrophy (n=28).

Despite complete or partial clinical response, 119 (62%) of 192 patients with clinical response were found to have persistent damage at their follow-up biopsy. There was no association between clinical response and mucosal recovery at the time of first follow-up biopsy (p=0.70).

Serology

Tissue transglutaminase antibodies results were available in 162 (67%) patients at the time of first follow-up biopsy, of whom 107 (66%) were negative and 55 (34%) were positive. From time of diagnosis to first follow-up biopsy, patients who were sero-tested at both time points demonstrated an improvement in tTGA result (p<.001). In particular, of the 79 patients tested at follow-up who previously had a positive tTGA result at diagnostic biopsy, 44 (56%) became seronegative. Seroconversion of tTGA was documented in 18 (64%) of 28 and 26 (51%) of 51 patients with and without mucosal recovery confirmation at the time of first follow-up biopsy, respectively (p=0.25).

Among the 124 (51%) patients for whom an EMA result was available at the time of first follow-up biopsy, 101 (81%) were negative and 23 (19%) were positive. Similar to tTGA results, patients who were EMA-tested at both time points demonstrated an improvement in EMA result from time of diagnosis to time of the first follow-up biopsy (p<.001). In 50 patients tested at follow-up who previously had a positive EMA at time of diagnosis, 36 (72%) became seronegative. Seroconversion of EMA was documented in 16 (89%) of 18 and 20 (63%) of 32 patients with and without mucosal recovery confirmation at the time of first follow-up biopsy, respectively (p=0.05).

Histologic findings in the second (or subsequent) follow-up biopsies

Seventy-nine (33%) patients had at least one additional follow-up biopsy subsequent to their first follow-up biopsy (n=50 patients who had one additional biopsy, n=9 patients who had two additional biopsies, and n=20 patients who had three or more additional biopsies). Among patients who showed persistent damage at their first follow-up biopsy, mucosal recovery was later confirmed in 34 (59%) of 58 patients with subsequent biopsies. Thus, after a median (range) follow-up duration of 19 months (5–420 months), the overall rate of confirmed mucosal recovery at 2 years following diagnosis was 34% (95% CI: 27%–40%), and 66% (95% CI: 58%–74%) after 5 years. The median time to confirmed mucosal recovery was approximately 3.8 years. Overall, mucosal recovery was confirmed in 124 patients at some time during clinical follow-up, 105 of whom were confirmed within 5 years.

The relationship between mucosal recovery and timing of first follow-up biopsy (from diagnostic biopsy) with mucosal recovery and timing of second follow-up biopsy (from initial follow-up biopsy) is summarized in Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary Table 2.

Strength of association between clinical factors and mucosal recovery

Among clinical factors evaluated around time of CD diagnosis, only severe clinical presentation and total villous atrophy were found to be associated with a lower rate of confirmed mucosal recovery (p<.001 for both; univariate analysis). In particular, the rate of mucosal recovery for CD patients with a severe clinical presentation is about half of that as those without a severe presentation, and is reduced nearly 3-fold in those with total versus partial villous atrophy. (Table 3)

Table 3.

Strength of association among clinical characteristics and mucosal recovery confirmation

| Clinical Characteristic | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis (per 10-year increase) | 0.94 (0.83 – 1.06) | 0.32 |

| Male gender (vs. female) | 0.86 (0.57–1.28) | 0.45 |

| Total villous atrophy at diagnosis (vs. partial) | 0.36 (0.24–0.52) | <.001 |

| Classical presentation of CD (vs. atypical) | 0.74 (0.50–1.09) | 0.13 |

| Severe CD (vs. non-severe CD) | 0.49 (0.33–0.72) | <.001 |

CD, celiac disease

Survival

The overall cohort of n=381 CD patients were followed over time for all-cause mortality. A total of 17 patients were determined to have died during the first 10-years of follow-up, 11 who had been evaluated at least once during follow-up for mucosal recovery. Among these 11 patients, all but one patient had shown evidence of persistent damage up to their last biopsy before death. There was a borderline significant association between confirmed mucosal recovery (vs. persistent damage) and reduced mortality (HR= 0.13; 95% CI, 0.02–1.06; p = .06) adjusted for gender and age. Among the 10 patients who died without prior mucosal recovery confirmation, cancer was the most common cause of death (Table 4).While autoimmune diseases other than CD were observed in 21% of patients, the presence of an autoimmune disease was not associated with mortality in this cohort (HR=1.34; 95% CI, 0.48–3.70; p=0.58).

Table 4.

Age and cause of death in 17 patients who died during clinical follow-up according to follow-up intestinal biopsy status

| Case | Mucosal recovery/IELs (%)* |

Duration from last biopsy to death, years |

Age at death/gender |

Cause of death |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | No/80 | 0.3 | 70/M | Enteropathy-type T-cell lymphoma |

| 2 | No/80 | 0.5 | 74/M | Enteropathy-type T-cell lymphoma |

| 3 | No/100 | 0.5 | 72/M | Heart failure secondary to giant cell myocarditis |

| 4 | No/60 | 0.6 | 61/M | Progressive inflammatory- destructive central nervous system disorder (autopsy diagnosis) |

| 5 | Yes/20 | 0.9 | 77/M | Interstitial pneumonia |

| 6 | No/60 | 1.0 | 68/M | Metastatic lung cancer |

| 7 | No/60 | 1.1 | 67/M | Streptococcal meningitis |

| 8 | No/100 | 1.3 | 65/F | Refractory celiac disease type 2 with enteropathy- type T-cell lymphoma |

| 9 | No/80 | 1.4 | 49/F | Diffuse anaplastic large-cell lymphoma (nodal site) |

| 10 | No/40 | 2.1 | 77/F | Hepatocarcinoma |

| 11 | Unknown | 2.9 | 84/F | Community-acquired bacterial pneumonia |

| 12 | Unknown | 2.9 | 50/F | Systemic lupus erythematous |

| 13 | No/100 | 3.1 | 66/F | Metastatic neuroendocrine carcinoid of the rectum |

| 14 | Unknown | 4.3 | 54/M | Sepsis secondary to acute cholecystitis |

| 15 | Unknown | 5.6 | 74/F | Acute lower extremity ischemia and sepsis |

| 16 | Unknown | - | 78/M | Acute myelogenous leukemia |

| 17 | Unknown | - | 61/M | Severe malnutrition with emaciation and anasarca |

IELs (%), intraepithelial lymphocytes per 100 epithelial cells

Discussion

The principal findings are: 1) mucosal recovery did not occur in a substantial portion of adults with CD for years following diagnosis (rate of confirmed mucosal recovery only 34% at 2 years; 95% CI: 27%–40%), 2) there was a borderline significant association between confirmed mucosal recovery (vs. persistent damage) and reduced mortality (HR= 0.13; 95% CI, 0.02–1.06; p = .06) independent of age and gender, and 3) poor compliance to GFD, total villous atrophy at diagnosis of CD, and severe clinical presentation were associated with persistence of intestinal damage in adults with treated CD.

A novel finding of this study is the fact that persons with mucosal recovery after treatment with a GFD may have a clinically relevant lower risk of all-cause mortality than patients with persistent mucosal damage. Moreover, the causes of death in most patients with persistent mucosal damage were CD-related complications such as refractory CD,16 lymphoma,37 hepatocellular carcinoma,38 and Streptococcal infections.39Thus, histological documentation of mucosal recovery by systematic follow-up with duodenal biopsies appears to be a relevant clinical end-point in adults with CD.

The reason(s) that may explain the higher rate of persistent mucosal damage in this cohort are unknown. Most patients in this cohort had good clinical response to GFD, but persistent mucosal damage. However, it is possible that the well-known causes of symptomatic, non-responsive treated CD (e.g., gluten contamination) may also underlie persistent mucosal damage in some of our patients.40, 41 The overall rate of good adherence to GFD in our cohort (66%) is consistent with the rate observed in other adult populations;42–45 poor adherence to a GFD appears to be an obvious factor for persistent damage in a minority of our patients (13%). However, the fact that only 67 (43%) of 156 patients with good adherence to a GFD, as determined by the dietitian interview, achieved mucosal recovery suggests that occult gluten sources (either cross-contamination or inadvertent gluten ingestion that are difficult to identify) or other yet unknown factors (e.g., genetics, age-related, duration of gluten exposure before treatment) may play a role in persistence of mucosal injury in adults with treated CD. These findings further support the urgent necessity of standard labeling for gluten-free foods in the United States.46, 47

Inappropriate food labeling, poor awareness and education about CD, high rate of undetected CD, late intervention, American lifestyle (e.g., culture of “dining out” and easy access to fast-food restaurants), and the limited availability or high cost of gluten-free foods (without compensation for additional cost of maintaining a GFD) might be some factors that explain discrepancies in rate of mucosal recovery after treatment with a GFD among United States and countries with excellent rates of mucosal recovery in adults such as Finland.48, 49 13, 46, 50 Thus, good adherence to GFD is necessary for mucosal recovery, but does not guarantee mucosal recovery in all. Currently, there is not consensus on either the role of intestinal biopsy to monitor intestinal recovery or the most appropriate time of repeat the intestinal biopsy after treatment with a GFD in adults with CD. Our data suggests that the time to mucosal recovery in adults with treated CD is longer than 6 months. Accordingly, a follow-up biopsy, 12–24 months after the onset of treatment with a GFD may be advisable in adults with CD. In this cohort, clinical response after GFD was not associated with mucosal recovery, consistent with other previous reports.9, 15 51 Serological responses (either negative EMA or negative tTGA) were significantly associated with mucosal recovery, however, persistent mucosal damage may be present in the absence of EMA or tTGA in the serum. Thus, biopsy remains the best tool to evaluate mucosal response in adults with CD, although limited only to the proximal small-intestine, where healing seems to lag behind healing more distally.52

Interestingly, 4 patients with poor adherence to GFD achieved mucosal recovery, suggesting that the development of tolerance to gluten may be possible in some adults with biopsy-proven CD; 53–55 however, clinical or histological relapse of the disease (in some cases with a different phenotype) or complications may still occur over time.54, 56

Mucosal recovery in adults with CD may be obtainable after strict adherence to GFD but may require a longer time,13 especially in patients with total villous atrophy at diagnosis as suggested by the evidence of histological improvement (from total to partial villous atrophy) after treatment with a GFD in 44% of our patients with total villous atrophy at baseline. Thus, it is possible that a longer time on a strict GFD may result in mucosal recovery in some patients consistent with our finding that 59% patients with a second or subsequent follow-up biopsies achieved mucosal recovery. However, cautious interpretation of these data is recommended because second (or subsequent) follow-up biopsies were obtained in only one-third of our cohort. Lastly, our results, obtained in a specialized center for celiac disease care may not be applicable to patients who do not have access to expert dietary instruction.

Intraepithelial lymphocytosis improved after treatment with a GFD in 92% of patients with concomitant mucosal recovery. The reason for persistence of intraepithelial lymphocytosis in 7 of our patients with mucosal recovery is unknown, but may be related to gluten-independent factors.34 33, 57 On the contrary, intraepithelial lymphocytosis was observed in up to 49% of patients without mucosal recovery. The fact that 51% patients without mucosal recovery had normal IEL numbers, suggests that intraepithelial lymphocytosis may improve before complete mucosal recovery is achieved, consistent with the model of stages of spectrum of severity. 31 All patients who died within 10 years of follow-up without mucosal recovery had concurrent intraepithelial lymphocytosis in the last follow-up biopsy. Taken together, these findings further support previous reports on the clinical benefit that a GFD may have in the treatment of both mild enteropathy CD or severe CD.1, 9, 58

Potential limitations of this study are those related to a retrospective design--not all patients underwent follow up biopsies at uniform intervals, missing data, drop-outs, and potential of referral or selection bias. Analysis of both the rate of mucosal recovery and potential interventions to improve histological outcome in adults with CD in referral and population-based cohorts by a prospective study design appears to be justified.

In conclusion, we demonstrated that mucosal recovery is absent in a substantial portion of adults with CD after treatment with a GFD. Achievement of mucosal recovery after treatment with a GFD in adults with CD may be associated with a better survival as compared to patients with persistent mucosal damage. Systematic follow-up with intestinal biopsies may be advisable in patients diagnosed with celiac disease as adults.

Study Highlights

What is current knowledge?

Lifelong GFD is the only effective treatment to alleviate the symptoms, normalize antibodies and the intestinal mucosa in patients with CD.

Up to 95% of children with CD may achieve mucosal recovery within 2 years after starting treatment with a GFD. The rate of mucosal recovery after treatment with a GFD in adults with CD is less certain.

Persistent mucosal damage after treatment with a GFD may increase the risk of complications in adults with CD. However, the effect that persistent mucosal damage after treatment with a GFD may have on survival of adults with CD is unknown.

What is new here?

Mucosal recovery was absent in a substantial portion of adults with CD years after diagnosis (Kaplan-Meier 2-year mucosal recovery rate of 34%; median time to confirmed mucosal recovery of about 3.8 years).

There is a borderline significant association between confirmed mucosal recovery (vs. persistent damage) and reduced mortality (HR= 0.13; 95% CI, 0.02–1.06; p = .06) independent of age and gender

Systematic follow-up with intestinal biopsies may be advisable in patients diagnosed with CD as adults.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award/Training Grant in Gastrointestinal Allergy and Immunology Research T32 AI07047 (awarded to A.R.T.) and NIH grant DK57892 (J.A.M.)

Abbreviations

- CD

celiac disease

- CI

confidence interval

- EMA

endomysial antibody

- GFD

gluten-free diet

- IELs

intraepithelial lymphocytes

- RCD

refractory celiac disease

- tTGA

tissue transglutaminase antibody

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest/Study Support

Guarantor of the Article: Joseph A Murray

Specific Authors Contributions: Alberto Rubio-Tapia: conception, design, collection and interpretation of data, statistical analysis, and manuscript preparation; Mussarat W Rahim: data collection; Jacalyn A See: expert dietitian assessment, analysis of data, and manuscript preparation; Brian D. Lahr: collection of data, statistical analysis, and manuscript preparation; Tsung-Teh Wu: analysis of data and manuscript preparation; Joseph A. Murray: conception, design, funding, collection and interpretation of data, and manuscript preparation. All authors have reviewed and approved the final draft submitted.

Potential Competing Interests: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Green PH, Cellier C. Celiac disease. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1731–1743. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra071600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rostom A, Murray JA, Kagnoff MF. American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) Institute technical review on the diagnosis and management of celiac disease. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:1981–2002. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haines ML, Anderson RP, Gibson PR. Systematic review: The evidence base for long-term management of coeliac disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;28:1042–1066. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03820.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murray JA, Watson T, Clearman B, Mitros F. Effect of a gluten-free diet on gastrointestinal symptoms in celiac disease. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;79:669–673. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/79.4.669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bardella MT, Velio P, Cesana BM, Prampolini L, Casella G, Di Bella C, Lanzini A, Gambarotti M, Bassotti G, Villanacci V. Coeliac disease: a histological follow-up study. Histopathology. 2007;50:465–471. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2007.02621.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee SK, Lo W, Memeo L, Rotterdam H, Green PH. Duodenal histology in patients with celiac disease after treatment with a gluten-free diet. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57:187–191. doi: 10.1067/mge.2003.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brar P, Kwon GY, Egbuna II, Holleran S, Ramakrishnan R, Bhagat G, Green PH. Lack of correlation of degree of villous atrophy with severity of clinical presentation of coeliac disease. Dig Liver Dis. 2007;39:26–29. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2006.07.014. discussion 30–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wahab PJ, Meijer JW, Mulder CJ. Histologic follow-up of people with celiac disease on a gluten-free diet: slow and incomplete recovery. Am J Clin Pathol. 2002;118:459–463. doi: 10.1309/EVXT-851X-WHLC-RLX9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lanzini A, Lanzarotto F, Villanacci V, Mora A, Bertolazzi S, Turini D, Carella G, Malagoli A, Ferrante G, Cesana BM, Ricci C. Complete recovery of intestinal mucosa occurs very rarely in adult coeliac patients despite adherence to gluten free diet. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2009.03992.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grefte JM, Bouman JG, Grond J, Jansen W, Kleibeuker JH. Slow and incomplete histological and functional recovery in adult gluten sensitive enteropathy. J Clin Pathol. 1988;41:886–891. doi: 10.1136/jcp.41.8.886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ciacci C, Cirillo M, Cavallaro R, Mazzacca G. Long-term follow-up of celiac adults on gluten-free diet: prevalence and correlates of intestinal damage. Digestion. 2002;66:178–185. doi: 10.1159/000066757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Selby WS, Painter D, Collins A, Faulkner-Hogg KB, Loblay RH. Persistent mucosal abnormalities in coeliac disease are not related to the ingestion of trace amounts of gluten. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1999;34:909–914. doi: 10.1080/003655299750025390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Collin P, Maki M, Kaukinen K. Complete small intestine mucosal recovery is obtainable in the treatment of celiac disease. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59:158–159. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(03)01311-7. author reply 159–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pietzak MM. Follow-up of patients with celiac disease: achieving compliance with treatment. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:S135–S141. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaukinen K, Peraaho M, Lindfors K, Partanen J, Woolley N, Pikkarainen P, Karvonen AL, Laasanen T, Sievanen H, Maki M, Collin P. Persistent small bowel mucosal villous atrophy without symptoms in coeliac disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;25:1237–1245. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03311.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rubio-Tapia A, Kelly DG, Lahr BD, Dogan A, Wu TT, Murray JA. Clinical staging and survival in refractory celiac disease: a single center experience. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:99–107. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.10.013. quiz 352–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Malamut G, Afchain P, Verkarre V, Lecomte T, Amiot A, Damotte D, Bouhnik Y, Colombel JF, Delchier JC, Allez M, Cosnes J, Lavergne-Slove A, Meresse B, Trinquart L, Macintyre E, Radford-Weiss I, Hermine O, Brousse N, Cerf-Bensussan N, Cellier C. Presentation and long-term follow-up of refractory celiac disease: comparison of type I with type II. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:81–90. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.09.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cellier C, Delabesse E, Helmer C, Patey N, Matuchansky C, Jabri B, Macintyre E, Cerf-Bensussan N, Brousse N. Refractory sprue, coeliac disease, and enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma. French Coeliac Disease Study Group. Lancet. 2000;356:203–208. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)02481-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Corrao G, Corazza GR, Bagnardi V, Brusco G, Ciacci C, Cottone M, Sategna Guidetti C, Usai P, Cesari P, Pelli MA, Loperfido S, Volta U, Calabro A, Certo M. Mortality in patients with coeliac disease and their relatives: a cohort study. Lancet. 2001;358:356–361. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(01)05554-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peters U, Askling J, Gridley G, Ekbom A, Linet M. Causes of death in patients with celiac disease in a population-based Swedish cohort. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:1566–1572. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.13.1566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.West J, Logan RF, Smith CJ, Hubbard RB, Card TR. Malignancy and mortality in people with coeliac disease: population based cohort study. Bmj. 2004;329:716–719. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38169.486701.7C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Logan RF, Rifkind EA, Turner ID, Ferguson A. Mortality in celiac disease. Gastroenterology. 1989;97:265–271. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(89)90060-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Holmes GK, Prior P, Lane MR, Pope D, Allan RN. Malignancy in coeliac disease--effect of a gluten free diet. Gut. 1989;30:333–338. doi: 10.1136/gut.30.3.333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Collin P, Reunala T, Pukkala E, Laippala P, Keyrilainen O, Pasternack A. Coeliac disease--associated disorders and survival. Gut. 1994;35:1215–1218. doi: 10.1136/gut.35.9.1215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rubio-Tapia A, Kyle RA, Kaplan EL, Johnson DR, Page W, Erdtmann F, Brantner TL, Kim WR, Phelps TK, Lahr BD, Zinsmeister AR, Melton LJ, 3rd, Murray JA. Increased Prevalence and Mortality in Undiagnosed Celiac Disease. Gastroenterology. 2009 doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.03.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Metzger MH, Heier M, Maki M, Bravi E, Schneider A, Lowel H, Illig T, Schuppan D, Wichmann HE. Mortality excess in individuals with elevated IgA anti-transglutaminase antibodies: the KORA/MONICA Augsburg cohort study 1989–1998. Eur J Epidemiol. 2006;21:359–365. doi: 10.1007/s10654-006-9002-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lohi S, Maki M, Rissanen H, Knekt P, Reunanen A, Kaukinen K. Prognosis of unrecognized coeliac disease as regards mortality: A population-based cohort study. Ann Med. 2009:1–8. doi: 10.1080/07853890903036199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lohi S, Maki M, Montonen J, Knekt P, Pukkala E, Reunanen A, Kaukinen K. Malignancies in cases with screening-identified evidence of coeliac disease: a long-term population-based cohort study. Gut. 2009;58:643–647. doi: 10.1136/gut.2007.140970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ludvigsson JF, Montgomery SM, Ekbom A, Brandt L, Granath F. Small-intestinal histopathology and mortality risk in celiac disease. Jama. 2009;302:1171–1178. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Green PH. Mortality in celiac disease, intestinal inflammation, and gluten sensitivity. Jama. 2009;302:1225–1226. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.24.2344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marsh MN. Gluten, major histocompatibility complex, and the small intestine. A molecular and immunobiologic approach to the spectrum of gluten sensitivity ('celiac sprue') Gastroenterology. 1992;102:330–354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oberhuber G, Granditsch G, Vogelsang H. The histopathology of coeliac disease: time for a standardized report scheme for pathologists. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1999;11:1185–1194. doi: 10.1097/00042737-199910000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vande Voort JL, Murray JA, Lahr BD, Van Dyke CT, Kroning CM, Moore SB, Wu TT. Lymphocytic duodenosis and the spectrum of celiac disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:142–148. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2008.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kakar S, Nehra V, Murray JA, Dayharsh GA, Burgart LJ. Significance of intraepithelial lymphocytosis in small bowel biopsy samples with normal mucosal architecture. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:2027–2033. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07631.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Iltanen S, Holm K, Partanen J, Laippala P, Maki M. Increased density of jejunal gammadelta+ T cells in patients having normal mucosa--marker of operative autoimmune mechanisms? Autoimmunity. 1999;29:179–187. doi: 10.3109/08916939908998533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Iltanen S, Holm K, Ashorn M, Ruuska T, Laippala P, Maki M. Changing jejunal gamma delta T cell receptor (TCR)-bearing intraepithelial lymphocyte density in coeliac disease. Clin Exp Immunol. 1999;117:51–55. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1999.00948.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Catassi C, Fabiani E, Corrao G, Barbato M, De Renzo A, Carella AM, Gabrielli A, Leoni P, Carroccio A, Baldassarre M, Bertolani P, Caramaschi P, Sozzi M, Guariso G, Volta U, Corazza GR. Risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma in celiac disease. Jama. 2002;287:1413–1419. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.11.1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ludvigsson JF, Elfstrom P, Broome U, Ekbom A, Montgomery SM. Celiac disease and risk of liver disease: a general population-based study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:63–69. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2006.09.034. e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ludvigsson JF, Olen O, Bell M, Ekbom A, Montgomery SM. Coeliac disease and risk of sepsis. Gut. 2008;57:1074–1080. doi: 10.1136/gut.2007.133868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Abdulkarim AS, Burgart LJ, See J, Murray JA. Etiology of nonresponsive celiac disease: results of a systematic approach. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:2016–2021. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05917.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Leffler DA, Dennis M, Hyett B, Kelly E, Schuppan D, Kelly CP. Etiologies and predictors of diagnosis in nonresponsive celiac disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:445–450. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2006.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hogberg L, Grodzinsky E, Stenhammar L. Better dietary compliance in patients with coeliac disease diagnosed in early childhood. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2003;38:751–754. doi: 10.1080/00365520310003318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vahedi K, Mascart F, Mary JY, Laberenne JE, Bouhnik Y, Morin MC, Ocmant A, Velly C, Colombel JF, Matuchansky C. Reliability of antitransglutaminase antibodies as predictors of gluten-free diet compliance in adult celiac disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:1079–1087. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07284.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kluge F, Koch HK, Grosse-Wilde H, Lesch R, Gerok W. Follow-up of treated adult celiac disease: clinical and morphological studies. Hepatogastroenterology. 1982;29:17–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bardella MT, Molteni N, Prampolini L, Giunta AM, Baldassarri AR, Morganti D, Bianchi PA. Need for follow up in coeliac disease. Arch Dis Child. 1994;70:211–213. doi: 10.1136/adc.70.3.211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Niewinski MM. Advances in celiac disease and gluten-free diet. J Am Diet Assoc. 2008;108:661–672. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2008.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.See J, Murray JA. Gluten-free diet: the medical and nutrition management of celiac disease. Nutr Clin Pract. 2006;21:1–15. doi: 10.1177/011542650602100101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lee AR, Ng DL, Zivin J, Green PH. Economic burden of a gluten-free diet. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2007;20:423–430. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-277X.2007.00763.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Maki M, Mustalahti K, Kokkonen J, Kulmala P, Haapalahti M, Karttunen T, Ilonen J, Laurila K, Dahlbom I, Hansson T, Hopfl P, Knip M. Prevalence of Celiac disease among children in Finland. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2517–2524. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Virta LJ, Kaukinen K, Collin P. Incidence and prevalence of diagnosed coeliac disease in Finland: Results of effective case finding in adults. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2009:1–6. doi: 10.1080/00365520903030795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Campanella J, Biagi F, Bianchi PI, Zanellati G, Marchese A, Corazza GR. Clinical response to gluten withdrawal is not an indicator of coeliac disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2008;43:1311–1314. doi: 10.1080/00365520802200036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Murray JA, Rubio-Tapia A, Van Dyke CT, Brogan DL, Knipschield MA, Lahr B, Rumalla A, Zinsmeister AR, Gostout CJ. Mucosal atrophy in celiac disease: extent of involvement, correlation with clinical presentation, and response to treatment. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:186–193. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.10.012. quiz 125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hopman EG, von Blomberg ME, Batstra MR, Morreau H, Dekker FW, Koning F, Lamers CB, Mearin ML. Gluten tolerance in adult patients with celiac disease 20 years after diagnosis? Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;20:423–429. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e3282f4de6e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Matysiak-Budnik T, Malamut G, de Serre NP, Grosdidier E, Seguier S, Brousse N, Caillat-Zucman S, Cerf-Bensussan N, Schmitz J, Cellier C. Long-term follow-up of 61 coeliac patients diagnosed in childhood: evolution toward latency is possible on a normal diet. Gut. 2007;56:1379–1386. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.100511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shmerling DH, Franckx J. Childhood celiac disease: a long-term analysis of relapses in 91 patients. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1986;5:565–569. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kurppa K, Koskinen O, Collin P, Maki M, Reunala T, Kaukinen K. Changing phenotype of celiac disease after long-term gluten exposure. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2008;47:500–503. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31817d8120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Collin P, Wahab PJ, Murray JA. Intraepithelial lymphocytes and coeliac disease. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2005;19:341–350. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2005.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kurppa K, Collin P, Viljamaa M, Haimila K, Saavalainen P, Partanen J, Laurila K, Huhtala H, Paasikivi K, Maki M, Kaukinen K. Diagnosing mild enteropathy celiac disease: a randomized, controlled clinical study. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:816–823. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.11.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]