Abstract

Transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder (TCC) ranks 4th in incidence of all cancers in the developed world, yet the mechanisms of its origin and progression remain poorly understood. There are also few useful diagnostic or prognostic biomarkers for this disease. We have combined a transgenic mouse model for invasive bladder cancer (UPII-SV40Tag mice) with DNA microarray technology, in order to determine molecular mechanisms involved in early TCC development and to identify new biomarkers for detection, diagnosis and prognosis of TCC. We have identified genes that are differentially expressed between the bladders of UPII-SV40Tag mice and their age-matched wild type (WT) littermates at 3, 6, 20 and 30 weeks of age. These are ages which correspond to premalignant, carcinoma in-situ, and early and later stage invasive TCC, respectively. Our preliminary analysis of the microarray data sets has revealed approximately 1,900 unique genes differentially expressed (≥ 3-fold difference at one or more time points) between WT and UPII-SV40Tag urothelium during the time course of tumor development. Among these, there were a high proportion of cell cycle regulatory genes and proliferation signaling genes that are more strongly expressed in the UPII-SV40Tag bladder urothelium. We show that several of the genes upregulated in UPII-SV40Tag urothelium, including RacGAP1, PCNA, and Hmmr are expressed at high levels in superficial bladder TCC patient samples. These findings provide insight into the earliest events in the development of bladder TCC as well as identify several promising early stage biomarkers.

Transitional cell carcinoma (TCC) of the bladder causes substantial morbidity and mortality and has the 4th highest incidence of all cancers in the developed world, with an estimated 70,000 new cases and predicted to occur in the US in 2009 (1). The number one correlate with bladder cancer is smoking. The majority of newly diagnosed cases (~2/3) are confined to the urothelium (do not breach the lamina propria) and are hence “superficial” or superficially invasive (2). There are a few commercially available urine-based tests for screening and surveillance for bladder cancer, but none of these can detect premalignancy (3, 4). Cytologic abnormalities of the urothelium are associated with carcinoma in situ (CIS), and urine cytology is positive in 90% of cases because of cell shedding into the urine due to loss of cellular adhesiveness. However cytology has a very low sensitivity and specificity for detection of lower grade TCC. Also, CIS is frequently associated with synchronous urothelial tumors of any stage. Strong indirect evidence indicates this lesion is a likely precursor of invasive carcinoma, but direct evidence in humans is lacking (5). Urothelial CIS has a high likelihood (>80%) of progressing to invasive carcinoma if left untreated. Patients with TCC require frequent cystoscopic examination. If a tumor is found, treatment is transurethral resection (TUR) and intravesical treatment. Cystectomy is required for invasive TCC confined to the bladder (6). Traditional prognostic factors (tumor stage, and grade) do not sufficiently predict disease course or prognosis in the individual patient. Long-term study results clearly indicate that the ability to intervene at early stages and to monitor the success of treatment requires the definition of early markers for bladder cancer. It is therefore of vital importance to identify gene expression changes that occur during these early stages of bladder carcinogenesis and progression.

In an attempt to generate a mouse model for bladder cancer progression, investigators in the laboratory of Xue-Ru Wu have engineered transgenic mice carrying a low copy number of the SV40 large T (SV40T) oncogene, expressed under the control of the bladder urothelium specific murine uroplakin II promoter (UPII-SV40Tag mice) (7). The SV40T oncogene can bind and inactivate the p53 and Rb tumor suppressor genes (8), both of which are frequently mutated in human bladder TCC (9). In quiescent cells Rb is bound to E2F family transcription factors, suppressing their ability to activate transcription of genes required for DNA replication, nucleotide metabolism, DNA repair and cell cycle progression (8, 10). SV40T blocks the Rb-mediated repression of E2F proteins, thereby inducing expression of E2F-regulated such as cyclins E, A and D1, chk1, fen1, BRCA1 and many others. UPII-SV40Tag mice develop a condition closely resembling human CIS starting as early as 6 weeks of age. This condition eventually progresses to invasive TCC from 6 months of age onward. Histological examination of the bladder CIS lesions closely mimics the human histology (7).

There has been extensive effort in recent years aimed at identifying genetic markers, small biomolecules, and proteins, as biomarkers for bladder cancer diagnosis, prediction of recurrence, as well as for surrogate endpoints in chemoprevention trials (3, 11). Ideally such biomarkers should be detectable by non-invasive means, should be accurate, sensitive and provide a viable alternative to cystoscopy, which is invasive and can have a sensitivity as low as 70% (12). In spite of the identification of several promising markers by several groups, none have yet been able meet these criteria (13–15). Therefore the search for non-invasive biomarkers (ie. in urine) demands a more guided approach. To this end we have combined the UPII-SV40Tag mouse model for bladder cancer progression with Affymetrix microarray technology to determine the gene transcription profiles of urothelium from the UPII-SV40Tag mice and age matched non-transgenic littermates (WT), at different times during the course of tumor development. We have identified approximately 1,900 unique genes differentially expressed (≥ 3-fold difference at one or more time points) between WT and UPII-SV40Tag urothelium during the time course of tumor development. Among these, there were a high proportion of cell cycle regulatory genes and proliferation signaling genes that were more strongly expressed in the UPII-SV40Tag bladder urothelium.

Materials and Methods

UPII-SV40Tag transgenic mice

UPII-SV40Tag mice were previously generated in the laboratory of Xue-Ru Wu (NYU School of Medicine, Kaplan Comprehensive Cancer Center) on an FVB/N background (7), and were a generous gift. All mice referred to as UPII-SV40Tag were hemizygous for transgene expression. Wild type control mice were age matched from the same litters as the transgenics. Genotypes were determined by PCR from tail genomic DNA preps using the following primers for the SV40Tag: 5′-TTCATGCCCTGAGTCTTCCAT-3′ and 5′-GCCAGGAAAATGCTGATAAAAATG-3′.

Small animal Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)

Mice were imaged using a Signa 1.5 T MR scanner. The mice were anesthetized using isoflurane inhalation anesthesia, and contrast was injected via the tail vein. In order to validate the MR imaging method of in vivo tumor detection in a mouse model, we scanned and subsequently sacrificed mice at 3, 4, 6, 8 and 12 months of age, and compared image and histopathologic assessment of the genitourinary tract. T2 weighted and T1 weighted plus contrast images were obtained for each mouse.

RNA isolation

Normal urothelium, hyperplastic/CIS urothelium, or TCC tissue was dissected from the bladder wall and snap frozen. Total cell RNA was isolated by homogenization of frozen tissue using TriReagent (Molecular Research), followed by standard organic extraction and precipitation and purification on RNeasy RNA purification columns (Quiagen). Purity and yield were determined by UV absorbance over the range of 220–320 nm. Total RNA was extracted from each human bladder-derived cell line using TRIzol (Molecular Research Center, Cincinnati, OH) according to manufacturer’s instructions. RNA concentrations were determined using a SmartSpec Plus Spectrophotometer (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA).

DNA microarrays

All DNA microarray procedures were performed in the LSUHSC-S DNA Array Research Core Facility. Probe synthesis and array hybridization was performed using established methods provided by Affymetrix. Briefly, two μg of purified urothelial cell RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA, using a T7 promoter-(dT)24 primer. Following second strand synthesis, biotin-labeled cRNA was generated from the double-stranded template using T7 RNA polymerase. The quality of the cRNA probe was verified by running an aliquot on an agarose gel. Exactly 20 μg of the labeled cRNA was hybridized to the Affymetrix GeneChip® Mouse Expression Set 430 chip for 16 h at 45C in 300ml of pre-mixed hybridization solution containing labeled hybridization control prokaryotic genes (bioB, bioC, bioD, and cre). Replicate spots for each control gene are present on the chip. Chips were washed in the GeneChip® Fluidics Station automatic washer and scanned on the GeneArray® fluorometric scanner. The data files were then transferred to one of the DNA Array Research Core computers for analysis.

Biometric analysis of microarray data

Identification of gene expression differences between microarrays was conducted within the DNA Array Core by Drs. Marjan Trutschl and Urska Cvek (Department of Computer Science and Mathematics, LSU-S). Affymetrix GeneChip Operating Software (GCOS, Affymetrix, Inc., Santa Clara, CA) and the R project (16) were used to analyze the data, combined with proprietary visualization software developed at LSU-S Laboratory for Advanced Biomedical Informatics. The total number of chips analyzed for this project was as follows: 4 time points (3, 6, 20 and 30 weeks) x 2 mouse types (and UPII-SV40Tag and nontransgenic littermates) x 2 replicate bladder urothelium RNA preps (except for the 6 week nontransgenic sample, which only had a single sample) for a total of 15 chips. We identified the genes expressed in the urothelium of UPII-SV40Tag and nontransgenic littermates at the four time points. Signal values and fold changes were determined by GCOS. Heatmap visualization was generated by using the WT to UPII-SV40Tag fold changes at each of the time points (3, 6, 20 and 30). The difference is marked as upregulated (red) if the fold change between the UPII-SV40Tag and WT was greater than 1, and downregulated (green), if it was smaller than 1. We used the Ingenuity Pathways Analysis software package (Ingenuity Systems Inc.) to explore signaling pathway and cell function ontologies between groups.

Semi-quantitative reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)

Semi-quantitative RT-PCR was performed essentially as previously described (17, 18). RNA (~2μg/reaction) was used to generate cDNA and the appropriate individual pairs of 20–30mer oligonucleotides (50 pmoles/reaction) for the test genes (Table 1) were used to amplify DNA from the cDNA. Semi-quantitative PCR was performed by using 100μl reaction volumes and taking 33μl aliquots at 25, 30, and 35 cycles. The expression of mRNA for the cytoskeletal protein β-Actin or 36B4, the gene for the ribosomal phosphoprotein P0, which are both ubiquitously expressed, was determined for each RNA sample to control for variations in RNA quantity. 10μl of each reaction was electrophoresed in a 2% agarose gel containing ethidium bromide. The gel was then developed using GelDoc XR system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) and quantified using Quantity One (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA).

Table 1.

The primer pairs are shown in the 5′ to 3′ direction, and are designated m for mouse and h for human.

| RT-PCR Primers for testing RNA from WT and UPII-SV40Tag mice | |

|---|---|

| Name | Sequences |

| mRacGAP1-5′ | GAGCCTCGAAAGATGGATAC |

| mRacGAP1-3′ | GCTGAATACTGCCAGATGTG |

| mAurkA-5′ | TCCTTCTAACTCCCAGCGTG |

| mAurkA-3′ | GAGCGTTTGCCAACTCAGTG |

| mAurkB-5′ | AGAAGAGCCGTTTCATCGTG |

| mAurkB-3′ | TCTTCTTGTGGCAGTAGGTC |

| mBrca-5′ | TGAAGGCAAGCTGCACTCTG |

| mBrca-3′ | AGTCCACTTCTCTCTATCAC |

| mC-Jun-5′ | TCTTGTGCCCCAAGAACGTG |

| mC-Jun-3′ | ATCTGTTGGGGCAAGTGGTG |

| mCcnb1-5′ | CCTGTGACAGTTACTGCTGC |

| mCcnb1-3′ | CATCAGAAAGCCTGACAC |

| mCcnd2-5′ | AAAGAGACCATCCCGCTGAC |

| mCcnd2-3′ | CTTCGATTTGCTCCTGGCAG |

| mSod3-5′ | GTTGAGAAGATAGGCGACAC |

| mSod3-3′ | ACCACGAAGTTGCCAAAGTC |

| mTtr-5′ | TCGCTGGACTGGTATTTGTG |

| mTtr-3′ | TCTTCCAGTACGATTTGGTG |

| m36B4-5′ | CAGCTCTGGAGAAACTGCTG |

| m36B4-3′ | GTGTACTCAGTCTCCACAGA |

| RT-PCR Primers for testing RNA from human bladder-derived cell lines | |

|---|---|

| Name | Sequences |

| hAurkB-5′ | GAGCTGAAGATTGCTGACTTC |

| hAurkB-3′ | CAGATCCACCTTCTCATTGTG |

| hCcnd2-5′ | AACAGAAGTGCGAAGAAGAG |

| hCcnd2-3′ | CACACAGAGCAATGAAGGTC |

| hRacGAP1-5′ | GATGGATACTATGATGCTGAATGTG |

| hRacGAP1-3′ | GCTTAGTTGAATGCTGCCAGATGTG |

| hβActin-5′ | CAACTGGGACGACATGGAGAA |

| hβActin-3′ | CCTTCTGCATCCTGTCGGCAA |

Cell lines

UM-UC-10, UM-UC-13 cells were cultured essentially as previously described in (19). Cells were cultured in 50% Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium low glucose/50% F12 medium (DMEM/F12) containing 10% fetal bovine serum. SV-HUC cells were cultured in F12+ media (F12 supplemented with 2.7g/L dextrose, 0.1mM non-essential amino acids, 0.2mM L-glutamine, 200U/L insulin, 1mg/ml human transferrin, 1mg/ml hydrocortisone) containing 5% FCS at 37° C in the humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2/95% air. Primary Human Urothelial cells (Pri-HUC, ScienCell Research Laboratories, San Diego, CA) were cultured according to manufacturer’s protocol. Pri-HUC’s were cultured in Urothelial cell medium (ScienCell catalog number 4321) supplemented with 1% urothelial cell growth supplement (UCGS, Cat. No. 4352) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin solution (P/S, Cat. No. 0503). All cells were cultured at 37° C in the humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2/95% air.

Immunohistochemical examination of human superficial bladder cancer specimens

Tissue obtained from transurethral resection was fixed in formalin and embedded in paraffin prior to sectioning. Paraffin sections of 4 μm were deparaffinized in xylene, 3 X 7 minutes, room temperature and rehydrated by stepwise washes in decreasing ethanol/H2O ratio (100% to 50%, followed by soaking in water). Sections were incubated in Superblock (Pierce Biotechnology Inc., Rockford, Ill.) blocking reagent for 1 hour at room temperature to block non-specific antigen sites. After washing 3X in PBS, slides were incubated overnight at 4°C with antibodies against RacGAP1, PON3, cytokeratin 19 (K19), and IL18 (Abcam Inc.); survivin (Birc5) and PCNA (Cell Signaling); and RHAMM (Santa Cruz). Colorimetric detection was performed according to the instructions for the Vectastain Elite ABC kit (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Fluorimetric detection was performed using Alexa-488-labeled secondary antibodies and sections were counterstained with DAPI. Slides were photographed on a Nikon TE300 microscope either with bright field or fluorescence conditions, with a CCD camera (Roper Scientific). Images were processed with IPLabs v3.55 software (Scanalytics Inc.).

Results

The UPII-SV40Tag model recapitulates invasive bladder TCC

In this study we have used the UPII-SV40Tag mouse model of bladder cancer progression, in combination with comprehensive DNA microarray analyses, to explore early events in the development of bladder cancer, and to identify potential biomarkers for bladder premalignancy. An initial goal was to better characterize the earliest macroscopic changes in bladder tissue in live UPII-SV40Tag mice using small animal magnetic resonance (MR) imaging techniques developed at the MD Anderson Cancer Center’s experimental animal imaging facility. We scanned and subsequently sacrificed mice at ages ranging from 6 weeks to 12 months of age, and compared MR image and histopathologic assessment of the genitourinary tract. An example of axial T1 post-contrast and T2 MR images of the urinary bladder of a 6 week old mouse that showed moderate irregular thickening of the urinary bladder mucosa which corresponded to histological findings of diffuse hyperplasia of the transitional epithelium is shown in figure 1 (Fig. 1d–f). At 38 weeks of age, MR imaging identified large, irregular contrast-enhancing masses within the bladder lumen, some of which had invaded into the surrounding abdominal cavity (Fig. 1, h,i, arrows). These tumors were carcinoid in appearance and without the delicate papillae that characterize papillary tumors. We found a close correlation between MR image and histologic detection of intravesical abnormalities in the mice in all age groups (Fig. 1, compare a,d, and g to other panels).

Figure 1.

H&E stain (panels a,d, and g) and MR images (b,c,e,f,h, and i) of the bladders of wild type littermates (WT, a–c) and transgenic mice at 6 weeks (d–f) and 38 weeks (g–i) of age. Arrows indicate a thickened mucosa in early stage TCC (f) and invasion into surrounding tissue for advanced TCC (h,i). Panels a, d and g were photographed at 100X magnfication.

Gene expression profile of bladder cancer progression

In parallel with the histologic and macroscopic characterization, we used Affymetrix DNA microarray technology to compare the gene transcription profiles of normal bladder urothelium (from non-transgenic littermates) with the urothelium of the UPII-SV40Tag mice, over time. We chose to examine mice at 3, 6, 20 and 30 weeks of age. These times for comparison encompass early stage changes that precede the appearance of CIS (3 weeks), CIS (6 weeks), and early and later stage TCC (20 and 30 weeks, respectively). Our determination of genes expressed in the urothelium at these time points revealed approximately 1,900 unique differentially expressed (≥3-fold difference) genes at one or more of the time points between the urothelium of UPII-SV40Tag mice and their age-matched wild type (WT) littermates (see supplemental table 1 for the full list). Figure 2 illustrates the clustering of the differentially expressed genes according their expression patterns over the time course. Genes more highly expressed in the UPII-SV40Tag bladders are shown in red and genes more strongly expressed in WT bladders are shown in green. Black bars indicate genes that are expressed at similar levels in both mouse lines for that time point. We focused attention on a group of genes with a high fold increase in expression in UPII-SV40Tag mice for all 4 time points (Fig. 2, expanded left panel). We reason that this group of genes could contain candidate biomarkers for both premalignant and later stage TCC. The time course of expression of some of the most strongly upregulated and downregulated genes are shown graphically (Fig. 3A, higher expression in UPII-SV40Tag; Fig. 3B, lower expression in UPII-SV40Tag). Interestingly some genes, like BRCA1, were strongly expressed in premalignant urothelium only at early stages of progression, with levels eventually dropping to near normal by later stages. We note a high proportion of genes involved in cell proliferation amongst the upregulated genes, and several structural and differentiation-related genes were among the downregulated genes. The microarray results were confirmed independently by RT-PCR for several of the genes (Fig. 4). For all genes tested to date, the relative direction of expression between WT and UPII-SV40Tag bladders was was the same for both the RT-PCR and microarray results.

Figure 2.

Preliminary hierarchical clustering of all four time points 3, 6, 20, and 30 weeks. The colors red, green, and black represent genes that are upregulated, downregulated, or no change, respectively, in the UPII-SV40Tag mice when compared to the WT littermates. The last cluster, cluster 8, has been enlarged and rescaled and represents genes that are highly upregulated at all four time points.

Figure 3.

A. Selected genes that were expressed at higher levels in UPII-SV40Tag urothelium relative to WT littermates are shown. Black bars indicate raw expression values for UPII-SV40Tag mice (n=2). Open bars indicate expression values for WT mice. B. Selected genes that were expressed at lower levels in UPII-SV40Tag urothelium relative to WT littermates.

Figure 4.

Confirmation of microarray data. RT-PCR was performed using the cDNA made from RNA extracted from the urothelium of 6 week old WT and 3 week old hemizygous mice (+/−) expressing SV40T antigen in the bladder under control of the Uroplakin II promoter.

Gene network and pathway analysis

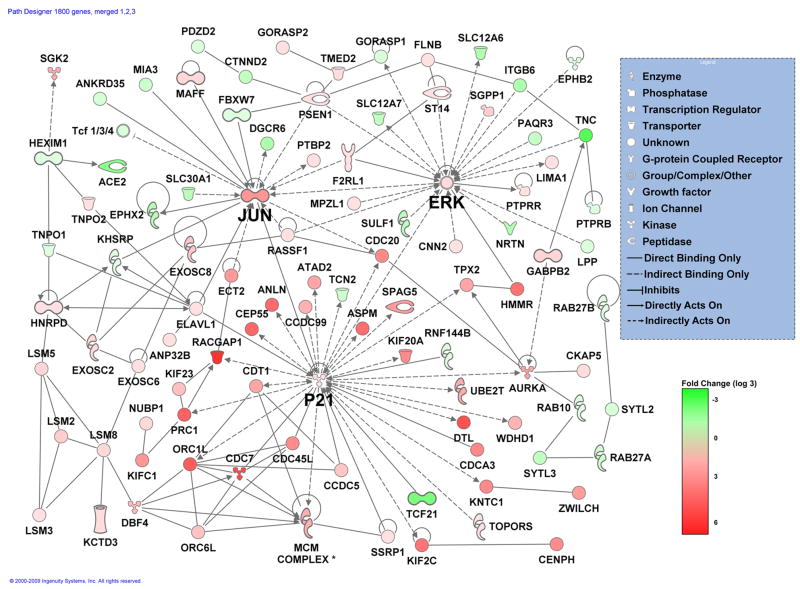

We next performed biometric analysis using the Path Explorer function in the Ingenuity Pathways Analysis software package (Ingenuity Systems Inc.) on the list of 1,900 differentially expressed genes (≥ 3-fold up or down at 1 or more time points), considering the expression differences between WT and UPII-SV40Tag mice separately for each time point. There was an average of 45 biological networks generated for the gene lists for each time point. Biological networks are defined as highly connected networks of up to 35 genes. A significance score based on a p-value calculation is assigned to each network and is displayed as a negative log of the p-value. The higher the score, the less likely it is that the set of genes from our list appearing in the network (focus genes) could be explained by random chance alone. See supplemental Table 2 for a full list of networks, their significance scores, number of focus molecules, relative direction of expression, and their top functions. The 30 top scoring gene networks were identical for all time points, although not all gene changes were the same in each network for each time point. This similarity between time points is expected since the same 1,900 gene list was used for each analysis, with only the fold difference between WT and UPII-SV40Tag varying between sets. The similarity indicates that most of the major gene expression changes start to take place as early as 3 weeks. It should be noted that the 3 week time point precedes the appearance of invasive TCC by several weeks, such that gene expression differences at this time could be considered representative of a premalignant state. The top scoring networks contain genes involved in cell cycle, DNA replication, recombination, and repair, cancer, cellular movement, and cellular assembly and organization. The merged image of the top 3 networks for the 3 week time point indicates three nodes centered on JUN, ERK, and P21, all key regulators of proliferative responses (Fig. 5). Some of the other genes that are upregulated in UPII-SV40Tag mice include those encoding centromere proteins Cenpa, Cenpf, Cenph; Aurora kinases A and B; cyclins ccnb1, ccnb2, ccne2, ccna2 and ccnf; cell division cycle proteins Cdc7, Cdc2a, Cdc20, Cdc6, Cdca3; kinesin-like family proteins, kifc1, kif2c, kif11, kif20a, kif 22, kif23; multiple minichromosome maintenance deficient proteins MCM2,4,5,6,7.8, and 10; other proliferation related proteins such as E2f8, Spbc24, Top2a, Brca1, RacGAP1, Hmmr, and others (Fig. 2, Fig. 5, and supplemental Table 1). Many of these genes are common with the SV40T/t-antigen cancer signature identified recently by Deeb et al, for human breast, prostate, and lung carcinomas (20). In addition, we have identified several genes that are suppressed in the UPII-SV40Tag bladders relative to wild type littermates, which includes a large proportion of structural and cell adhesion genes that appear to be related to the normal differentiated state of urothelium. Examples are genes encoding extracellular matrix proteins such as collagens Col1a1, Col1a2, Col6a2, Col3a1, laminin B1, and tenascin C; keratins krt2-5, krt1-15 and other intermediate filament proteins Dmn, Vim; as well as uroplakins upk1b and upk2 itself, and other tight junction proteins cldn8, ctnnb1, ctnnal1, ctnnd2, pcdhgc3, and cgnl1. Other downregulated genes that are potentially involved in the development of TCC include superoxide dismutase 3 (SOD3), cyclin D2 (ccnd2), transthyretin (Ttr), bone morphogenetic protein 2 (BMP2), and matrix metalloproteinase 2 (Mmp2). As in Figure 1, red and green indicates higher expression in the UPII-SV40Tag and WT bladders, respectively.

Figure 5.

Gene interaction networks #1–3. Gene expression profiles of 3 week old WT and UPII-SV40Tag bladder urothelial tissue (n=2 for each group) were compared using Ingenuity microarray analysis software. Genes overexpressed and underexpressed in UPII-SV40T bladders compared to WT mice, at the 3 week time point, are shown in red and green, respectively.

Differentially expressed genes in human bladder-derived cell lines and in human superficial bladder cancer

Finally, we have attempted to determine the relevance of several of the differentially expressed genes to human bladder cancer. We first compared mRNA expression levels for several genes in human normal urothelial cells (primary HUCs), ‘premalignant’ urothelial cells (SV-HUC) and advanced TCC cells (UM-UC-10, UM-UC-13). We have recently described the UM-UC cells in detail (21). The UM-UC-10 cells were derived from a bladder tumor, have mutant p53, undetectable levels of Rb, and are non-tumorigenic in nude mice. The UM-UC13 cells were derived from a lymphatic metastasis, also have mutant p53 and undetectable RB, but are tumorigenic in nude mice. We observed that more than half of the genes tested by semi-quantitative RT-PCR were expressed as predicted in the human cell lines, such that genes overexpressed in the UPII-SV40Tag mice were more strongly expressed in the premalignant and malignant cell lines (Fig. 6A and data not shown). Conversely, Ccnd2, which was downregulated in the UPII-SV40Tag mice, is expressed only in the primary HUCs.

Figure 6.

A. Differentially expressed genes in human bladder derived cells. Semi-quantitative RT-PCR of 25, 30, and 35 cycles was performed on four human bladder cell lines using primers for four of the genes identified from the UPII-SV40Tag mouse microarray experiment. The relative expression was determined by a ratio of each sample to the most intense sample for that gene, which was assigned a value of one. B. Immunohistochemical detection of differentially expressed genes in paraffin sections of superficial bladder TCC. Sections were probed with antibodies for the indicated proteins and detected colorimetrically using horseradish peroxidase-coupled secondary antibodies, except for the RacGAP1 20X and Hmmr 40X panels which were detected by fluorescently tagged secondary antibodies.

Next we tested the expression of several differentially expressed genes in paraffin sections of high and low grade superficial bladder TCC samples that were excised by transurethral resection. We prioritized biomarkers for initial testing based on whether the genes were found to be highly expressed at all 4 time points (PCNA, Survivin, Hmmr, RacGAP1) as shown in figure 2, left panel; are cell surface proteins (PON3), or are secreted (IL18). We reason that such proteins would also have a higher likelihood of being detectable in urine. To date we have tested expression of 6 proteins in tumor samples from 12 patients (6 high grade and 6 low grade). All 6 of these proteins were detectable by immunohistochemical staining in the patient samples, with the strongest expression detected for RacGAP1, PCNA, and Hmmr (Fig. 6B, and data not shown). This expression also co-localized with expression of cytokeratin 19 (K19), a urothelial marker. Hmmr is expressed evenly throughout the cytoplasm, while PCNA is strongly expressed in the nuclei of hyperplastic urothelial cells, as previously described by others (Fig. 6B, lower row) (22, 23). We note that RacGAP1 is expressed in the cytoplasm, with prominent focal perinuclear staining, which is in agreement with our own immunocytochemical staining of bladder TCC cell lines (data not shown). It is not yet possible to determine whether there is a statistically significant difference in expression for any of the markers between high and low grade TCC due to the low sample size.

Discussion

These findings represent what is to our knowledge the first attempt to obtain a comprehensive gene expression profile of bladder premalignancy. This is part of our long term effort to identify biomarkers of the earliest stages bladder TCC, which could potentially predict occurrence and recurrence of bladder TCC. A more immediate aim of these studies is to identify potential biomarkers of early stage bladder TCC, that can be tested in patient urine, bladder wash and other tissue samples. We have identified approximately 1,900 genes that are differentially expressed (> 3-fold higher or lower) between the bladder urothelium of UPII-SV40Tag mice and their age-matched WT littermates at ages that encompass early stage changes that precede the appearance of CIS (3 weeks), CIS (6 weeks), and early and later stage TCC (20 and 30 weeks, respectively).

A large proportion of the genes upregulated in the UPII-SV40Tag urothelium are cell cycle regulatory and proliferation signaling genes. Many of these genes are common with the SV40T/t-antigen cancer signature identified recently by the laboratory of J.E. Green and collaborators, (20). These investigators used DNA microarrays to compare three transgenic mouse models for breast, lung, and prostate cancer, all based on tissue specific expression of SV40Tag, and found a common set of differentially expressed genes that are involved in cell proliferation, DNA repair and apoptosis. Of the 119 genes that comprise this T/t-antigen signature, 73 are found in our list of ~1,900 differentially expressed genes (61% identity), suggesting similarity between models. Most importantly, this same signature of genes was associated with the most aggressive tumor phenotype and poor prognosis in human breast, lung, and prostate cancer (20). Whether the same association exists with human bladder TCC remains to be determined. In addition to over-expressed genes, we have identified several genes that are suppressed in the UPII-SV40Tag bladders relative to wild type littermates. This includes structural and cell adhesion genes that appear to be related to the normal differentiated state of urothelium. These include genes encoding extracellular matrix proteins, intermediate filament proteins, as well as uroplakins and other tight junction proteins. Supplemental table 1 contains the full list of genes that were found to by differentially expressed (≥ 3-fold at one or more time points) between UPII-SV40Tag and WT littermate urothelium.

We used the Ingenuity Pathways Analysis software package to analyze the microarray data sets in order to identify the predominant cellular functions and signaling pathways that distinguish the earliest accessible stage of bladder TCC in the UPII-SV40T model. When we examined the biological networks that are derived from the 1,900 differentially expressed gene list, we noted that the top scoring networks contain genes involved in cell cycle, DNA replication, recombination, and repair, cancer, cellular movement, and cellular assembly and organization. The three highest scoring networks center on the activator protein 1(AP-1) transcription factor subunit, JUN; the MAP kinase extracellular signal-regulated kinase, ERK, and the cyclin dependent kinase inhibitor, P21 (Fig. 5). These are regulators of proliferative responses and are part of linked pathways all known to be affected by oncogenic mutations (24). AP-1 is a positive regulator of cell proliferation and transformation and its activity is stimulated in mouse skin tumorigenesis models by the tumor promoter TPA (12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate) (25). A direct link between between MAPK signaling and AP-1 activity has been established from studies in which kinase deficient forms of ERK could inhibit AP-1 activation by several stimuli (26, 27). Those findings have led to several studies, including our own, aimed at understanding the mechanism of suppression of MAP kinase signaling and/or AP-1 activity by the vitamin A metabolite all-trans retinoic acid (ATRA), an efficient suppressor of tumor formation in several epithelial cancer models (28–30). Our recent studies have shown that the B-Raf/Mek/Erk MAP kinase pathway is a target for the chemopreventive activity of ATRA in the mouse 2-stage skin carcinogenesis model (29). The present gene network analysis suggests that this same pathway could also be a target for prevention of bladder TCC, and will guide future experiments for testing potential chemopreventive and/or therapeutic drugs such as ATRA.

In an effort to narrow our candidate list of biomarkers to those most likely to be involved in the earliest stages of TCC, we have focused on genes differentially expressed at the 3 week time point. Amongst these genes, we have further focused on those which also remain highly differentially expressed at later time points, with the expectation that such genes could also serve a markers for later stage TCC (Fig. 2, left panel). Also, in order to increase the likelihood of detection by antibodies in urine samples, we are paying closest attention to proteins that are secreted or are known to reside in the plasma membrane, and with few exceptions, those which have been previously detected in urine or bladder tissue by other investigators. These in include hyaluronan mediated motility receptor (Hmmr/Rhamm), which has been identified as highly expressed in early stage (Ta, T1), and later stage (T2-4) bladder TCC (22); proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) (23), autocrine motility factor receptor (AMFR) (31) and others. We have tested for expression of several candidate genes that are upregulated in UPII-SV40Tag mice at all 4 time points (RacGAP1, PCNA, Survivin, and Hmmr), are upregulated and secreted (IL18) and are upregulated and expressed at the cell surface (PON3), in paraffin sections of high and low grade superficial bladder TCC samples. We detect all of these proteins to varying degrees in the tumor samples, with the highest levels detectable for RacGAP1, PCNA and Hmmr (Fig. 6B). This data, while preliminary, provides strong support for further testing and validation of these genes as biomarkers for superficial (early stage) TCC. We have also begun testing for expression of these proteins in urine samples from a recently completed Phase II, randomized, placebo controlled chemoprevention trial (N01 CN85186, PI: A. Sabichi) that was designed to test whether celecoxib can prevent recurrence in patients successfully treated by TUR for non-muscle invasive bladder cancer. In this trial, urine samples were collected over the course of treatment every 3 months for 18 months after curative therapy (TUR plus BCG), or until the time of recurrence (~30% of patients). It is anticipated that single markers or combinations of markers can be validated for prediction of recurrence, and possibly for prediction of response to therapy. In the future we will also focus attention on proteins predicted to be downregulated in premalignant urothelium, such as uroplakin II, bone morphogenetic protein 2 (BMP2), and superoxide dismutase 3 (SOD3). These could serve as negative markers for recurrence.

We have identified genes that are differentially expressed in premalignant urothelia, in a mouse model for aggressive bladder TCC. This group of genes now serves as a promising pool of candidates for biomarkers for early stage TCC, as well as a source for gaining insight into the earliest events preceding early stage TCC and/or CIS. Future experiments are aimed at validating promising biomarkers in larger numbers of patient tumor samples and in urine, as well as exploring the molecular roles of individual differentially regulated genes (eg. Hmmr) in bladder premalignancy and early stage bladder TCC.

Supplementary Material

The complete list of unique differentially expressed (≥3-fold difference) genes at one or more of the time points between the urothelium of UPII-SV40Tag mice and their age-matched wild type (WT) littermates. The numbers in the columns for each time point are expressed in a log 3 scale, such that a value of +1 indicates a 3-fold higher expression, +2 indicates a 9-fold higher expression, etc, in the UPII-SV40Tag urothelium compared to WT. A list of differentially expressed genes in which there is a ≥2-fold difference between UPII-SV40Tag and WT mice contains approximately 3,500 genes and is available upon request.

The list of biological networks generated from the 1,900 differentially expressed genes, for each time point, using the Ingenuity Pathways Analysis software package (Ingenuity Systems Inc.). The score is a significance score based on a p-value calculation, assigned to each network and is displayed as a negative log of the p-value. The higher the score, the less the likelihood that the set of genes from our list appearing in the network (focus genes) could be explained by random chance alone. The Focus Mol column indicates the number of genes from the 1,900 gene list that appear in the network. The Up/Down ratio is the number of focus genes for which expression is increased and decreased in UPII-SV40Tag compared to WT mice. For example the ratio of 32/3 for network #1 in the 3 week column indicates that 32 of the 35 focus genes were expressed more strongly in the UPII-SV40Tag urothelium than in WT, and that 3 of the 35 focus genes were expressed at lower levels in the UPII-SV40Tag urothelium than in WT. The Top Functions column indicates the major cellular functions for each biological network. C, Cancer; CAO, Cellular Assembly and Organization; GE, Gene Expression; CC, Cell Cycle; DRRR, DNA Replication, Recombination, and Repair; AAM, Amino Acid Metabolism; CD, Cellular Development; LM, Lipid Metabolism; SMB, Small Molecule Biochemistry; CVD, Cardiovascular Disease; CGP, Cellular Growth and Proliferation; CM, Cellular Movement; TM, Tissue Morphology; CMB, Carbohydrate Metabolism; CS, Cell Signaling; GD, Genetic Disorder; RPTM, RNA Post-Transcriptional Modification; CFM, Cellular Function and Maintenance; CSDF, Cardiovascular System Development and Function; CTCSI, Cell-To-Cell Signaling and Interaction; CMP, Cell Morphology; GID, Gastrointestinal Disease; PTM, Post-Translational Modification; AD, Auditory Disease; CCP, Cellular Compromise; CI, Cardiac Infarction; DM, Drug Metabolism; ESD, Endocrine System Disorders; HSDF, Hematological System Development and Function; MT, Molecular Transport; HD, Hematological Disease; ID, Inflammatory Disease; MD, Metabolic Disease; PD, Protein Degradation; RSD, Reproductive System Disease; SMD, Skeletal and Muscular Disorders; CDT, Cell Death; CTDF, Connective Tissue Development and Function; ESDF, Endocrine System Development and Function; HSDF, Hair and Skin Development and Function; ILSDF, Immune and Lymphatic System Development and Function; IR, Immune Response; NAM, Nucleic Acid Metabolism; ND, Neurological Disease; OD, Organ Development; RUD, Renal and Urological Disease; SMSDF, Skeletal and Muscular System Development and Function; VF, Viral Function; NTD, Nutritional Disease; RPD, Respiratory Disease; PF, Protein Folding; RSDF, Respiratory System Development and Function.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Dr. Xue-Ru Wu for generously providing the UPII-SV40Tag mice. We thank Paula Polk in the LSUHSC-Shreveport DNA Array Research Core Facility for excellent technical assistance. We also thank Dr. H. Barton Grossman (Department of Urology, Univ. of Texas-M.D. Anderson Cancer Center) for the UM-UC cell lines.

Footnotes

Grant support: Grant from the Feist-Weiller Cancer Center, Louisiana Board of Regents, NIH/INBRE P20 RR16456, and NCI CA116324.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Hao Y, Xu J, Thun MJ. Cancer Statistics, 2009. CA Cancer J Clin. 2009 doi: 10.3322/caac.20006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Prout GR., Jr Bladder carcinoma and a TNM system of classification. J Urol. 1977;117:583–90. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)58544-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Budman LI, Kassouf W, Steinberg JR. Biomarkers for detection and surveillance of bladder cancer. Can Urol Assoc J. 2008;2:212–21. doi: 10.5489/cuaj.600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Konety B, Lotan Y. Urothelial bladder cancer: biomarkers for detection and screening. BJU Int. 2008;102:1234–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.07965.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bostwick DG, Ramnani D, Cheng L. Diagnosis and grading of bladder cancer and associated lesions. Urol Clin North Am. 1999;26:493–507. doi: 10.1016/s0094-0143(05)70197-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sabichi AL, Lerner SP, Grossman HB, Lippman SM. Retinoids in the chemoprevention of bladder cancer. Curr Opin Oncol. 1998;10:479–84. doi: 10.1097/00001622-199809000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang ZT, Pak J, Shapiro E, Sun TT, Wu XR. Urothelium-specific expression of an oncogene in transgenic mice induced the formation of carcinoma in situ and invasive transitional cell carcinoma. Cancer Res. 1999;59:3512–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ahuja D, Saenz-Robles MT, Pipas JM. SV40 large T antigen targets multiple cellular pathways to elicit cellular transformation. Oncogene. 2005;24:7729–45. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cordon-Cardo C, Zhang ZF, Dalbagni G, et al. Cooperative effects of p53 and pRB alterations in primary superficial bladder tumors. Cancer Res. 1997;57:1217–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dimova DK, Dyson NJ. The E2F transcriptional network: old acquaintances with new faces. Oncogene. 2005;24:2810–26. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lodde M, Fradet Y. The detection of genetic markers of bladder cancer in urine and serum. Curr Opin Urol. 2008;18:499–503. doi: 10.1097/MOU.0b013e32830b86d1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lam T, Nabi G. Potential of urinary biomarkers in early bladder cancer diagnosis. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2007;7:1105–15. doi: 10.1586/14737140.7.8.1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shariat SF, Karakiewicz PI, Ashfaq R, et al. Multiple biomarkers improve prediction of bladder cancer recurrence and mortality in patients undergoing cystectomy. Cancer. 2008;112:315–25. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harris LD, De La Cerda J, Tuziak T, et al. Analysis of the expression of biomarkers in urinary bladder cancer using a tissue microarray. Mol Carcinog. 2008;47:678–85. doi: 10.1002/mc.20420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alvarez A, Lokeshwar VB. Bladder cancer biomarkers: current developments and future implementation. Curr Opin Urol. 2007;17:341–6. doi: 10.1097/MOU.0b013e3282c8c72b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Foundation R. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna: R Foundation for statistical computing; 2007. R Developmental Core Team. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Clifford J, Chiba H, Sobieszczuk D, Metzger D, Chambon P. RXRalpha-null F9 embryonal carcinoma cells are resistant to the differentiation, anti-proliferative and apoptotic effects of retinoids. Embo J. 1996;15:4142–55. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xu H, Cheepala S, McCauley E, et al. Chemoprevention of skin carcinogenesis by phenylretinamides: retinoid receptor-independent tumor suppression. Clin Cancer Res. 2006a;12:969–79. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Clifford JL, Sabichi AL, Zou C, et al. Effects of novel phenylretinamides on cell growth and apoptosis in bladder cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2001;10:391–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Deeb KK, Michalowska AM, Yoon CY, et al. Identification of an integrated SV40 T/t-antigen cancer signature in aggressive human breast, prostate, and lung carcinomas with poor prognosis. Cancer Res. 2007;67:8065–80. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sabichi A, Keyhani A, Tanaka N, et al. Characterization of a panel of cell lines derived from urothelial neoplasms: genetic alterations, growth in vivo and the relationship of adenoviral mediated gene transfer to coxsackie adenovirus receptor expression. J Urol. 2006;175:1133–7. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)00323-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kong QY, Liu J, Chen XY, Wang XW, Sun Y, Li H. Differential expression patterns of hyaluronan receptors CD44 and RHAMM in transitional cell carcinomas of urinary bladder. Oncol Rep. 2003;10:51–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Inagaki T, Ebisuno S, Uekado Y, et al. PCNA and p53 in urinary bladder cancer: correlation with histological findings and prognosis. Int J Urol. 1997;4:172–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.1997.tb00166.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dhillon AS, Hagan S, Rath O, Kolch W. MAP kinase signalling pathways in cancer. Oncogene. 2007;26:3279–90. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Angel P, Szabowski A, Schorpp-Kistner M. Function and regulation of AP-1 subunits in skin physiology and pathology. Oncogene. 2001;20:2413–23. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Frost JA, Geppert TD, Cobb MH, Feramisco JR. A requirement for extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) function in the activation of AP-1 by Ha-Ras, phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate, and serum. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:3844–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.9.3844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Watts RG, Huang C, Young MR, et al. Expression of dominant negative Erk2 inhibits AP-1 transactivation and neoplastic transformation. Oncogene. 1998;17:3493–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Niles RM. Signaling pathways in retinoid chemoprevention and treatment of cancer. Mutat Res. 2004;555:81–96. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2004.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cheepala SB, Yin W, Syed Z, et al. Identification of the B-Raf/Mek/Erk MAP kinase pathway as a target for all-trans retinoic acid during skin cancer promotion. Mol Cancer. 2009;8:27. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-8-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cheepala SB, Syed Z, Trutschl M, Cvek U, Clifford JL. Retinoids and skin: Microarrays shed new light on chemopreventive action of all-trans retinoic acid. Mol Carcinog. 2007;46:634–9. doi: 10.1002/mc.20346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Korman HJ, Peabody JO, Cerny JC, Farah RN, Yao J, Raz A. Autocrine motility factor receptor as a possible urine marker for transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder. J Urol. 1996;155:347–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The complete list of unique differentially expressed (≥3-fold difference) genes at one or more of the time points between the urothelium of UPII-SV40Tag mice and their age-matched wild type (WT) littermates. The numbers in the columns for each time point are expressed in a log 3 scale, such that a value of +1 indicates a 3-fold higher expression, +2 indicates a 9-fold higher expression, etc, in the UPII-SV40Tag urothelium compared to WT. A list of differentially expressed genes in which there is a ≥2-fold difference between UPII-SV40Tag and WT mice contains approximately 3,500 genes and is available upon request.

The list of biological networks generated from the 1,900 differentially expressed genes, for each time point, using the Ingenuity Pathways Analysis software package (Ingenuity Systems Inc.). The score is a significance score based on a p-value calculation, assigned to each network and is displayed as a negative log of the p-value. The higher the score, the less the likelihood that the set of genes from our list appearing in the network (focus genes) could be explained by random chance alone. The Focus Mol column indicates the number of genes from the 1,900 gene list that appear in the network. The Up/Down ratio is the number of focus genes for which expression is increased and decreased in UPII-SV40Tag compared to WT mice. For example the ratio of 32/3 for network #1 in the 3 week column indicates that 32 of the 35 focus genes were expressed more strongly in the UPII-SV40Tag urothelium than in WT, and that 3 of the 35 focus genes were expressed at lower levels in the UPII-SV40Tag urothelium than in WT. The Top Functions column indicates the major cellular functions for each biological network. C, Cancer; CAO, Cellular Assembly and Organization; GE, Gene Expression; CC, Cell Cycle; DRRR, DNA Replication, Recombination, and Repair; AAM, Amino Acid Metabolism; CD, Cellular Development; LM, Lipid Metabolism; SMB, Small Molecule Biochemistry; CVD, Cardiovascular Disease; CGP, Cellular Growth and Proliferation; CM, Cellular Movement; TM, Tissue Morphology; CMB, Carbohydrate Metabolism; CS, Cell Signaling; GD, Genetic Disorder; RPTM, RNA Post-Transcriptional Modification; CFM, Cellular Function and Maintenance; CSDF, Cardiovascular System Development and Function; CTCSI, Cell-To-Cell Signaling and Interaction; CMP, Cell Morphology; GID, Gastrointestinal Disease; PTM, Post-Translational Modification; AD, Auditory Disease; CCP, Cellular Compromise; CI, Cardiac Infarction; DM, Drug Metabolism; ESD, Endocrine System Disorders; HSDF, Hematological System Development and Function; MT, Molecular Transport; HD, Hematological Disease; ID, Inflammatory Disease; MD, Metabolic Disease; PD, Protein Degradation; RSD, Reproductive System Disease; SMD, Skeletal and Muscular Disorders; CDT, Cell Death; CTDF, Connective Tissue Development and Function; ESDF, Endocrine System Development and Function; HSDF, Hair and Skin Development and Function; ILSDF, Immune and Lymphatic System Development and Function; IR, Immune Response; NAM, Nucleic Acid Metabolism; ND, Neurological Disease; OD, Organ Development; RUD, Renal and Urological Disease; SMSDF, Skeletal and Muscular System Development and Function; VF, Viral Function; NTD, Nutritional Disease; RPD, Respiratory Disease; PF, Protein Folding; RSDF, Respiratory System Development and Function.