Abstract

Objective To test the effectiveness of a comprehensive specific care plan in decreasing the rate of functional decline in patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease compared with usual care in memory clinics.

Design Cluster randomised trial.

Setting 50 memory clinics in France.

Participants Patients with Alzheimer’s disease (mini-mental state examination score 12-26). 1131 patients were included: 574 from 26 clinics in the intervention group, and 557 from 24 clinics in the usual care (control) group. Memory clinics were the unit of randomisation.

Intervention The intervention included a comprehensive standardised twice yearly consultation for patients and their caregivers, with standardised guidelines for the management of problems identified during the assessment.

Main outcome measures The primary outcome measure was change on the Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study-activities of daily living scale assessed at 12 and 24 months. Secondary outcome measures were the rate of admission to institutional care and mortality.

Results At two years the assessment was completed by 58.4% (n=335) of patients in the intervention group and 61.6% (n=343) in the control group. The rate of functional decline at two years did not differ between the groups. The annual rate of change on the Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study-activities of daily living was estimated at −5.73 (95% confidence interval −6.89 to −4.57) in the intervention group and −5.96 (−7.05 to −4.86) in the control group (P=0.78).

Conclusion A comprehensive specific care plan in memory clinics had no additional positive effect on functional decline in patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease. Future research should aim to determine the effects of more direct involvement of general practitioners.

Trial registration ClinicalTrials.gov NCT00480220.

Introduction

Several authoritative groups have published consensus guidelines for the care of patients with Alzheimer’s disease and suggested regular follow-up, with evaluation and management of behavioural disturbances, psychoses, and depression; active monitoring and support of the caregiver’s emotional and physical health; and consideration of treatment with specific drugs.1 2 3 4 The guidelines are based mostly on the scientific literature. They also include some empirical guidelines; for example, on the frequency of follow-up assessments. However, the literature reveals some serious deficits in the quality of patient management in clinical practice.5 6

Randomised trials of interventions aiming to improve outcomes for patients with dementia are few, and those that do exist have reported limited impacts in primary and residential care.7 8 9 Because of the multifaceted nature of Alzheimer’s disease, comprehensive, guideline based interventions for dementia care would seem to be a well suited approach. Some questions remain, however, about the setting in which follow-up and comprehensive assessments should be carried out (primary care versus memory clinics), as well as the feasibility and real impact of these guidelines. To our knowledge, no large scale interventional studies integrating a comprehensive, guideline based, intervention for care of patients with dementia in memory clinics have been carried out to date.

We carried out a cluster randomised trial at national level to test the effectiveness of a comprehensive specific care plan in decreasing the rate of functional decline in community dwelling patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease compared with usual care in memory clinics.

Methods

Our study was a nationwide trial using a cluster randomised design to compare an intervention group receiving a comprehensive specific care plan for Alzheimer’s disease with a control group receiving usual care. Memory clinics in university or general hospitals constituted the unit of randomisation, with patients as the unit of analysis. Through the use of this design we minimised the risk of contamination between patients because our intervention concerned doctor practice.

Patients in the intervention group were evaluated every six months at the clinic, with supplementary consultations if considered necessary by the doctor. Investigators informed the patient’s general practitioner about the care plan after each visit. Patients in the control group were evaluated annually. Unrestricted by the study protocol the doctor in charge of the patient determined the frequency of other consultations between these visits. Patients in the control group were managed according to each centre’s usual practice. We obtained written informed consent from the patients and their caregivers before beginning the protocol specific procedures. The trial is reported according to the consolidated standards of reporting trials statement10 and its extensions to cluster randomised trials11 and to non-drug interventions.12

Participants

The centres were memory clinics in university or general hospitals. The centres selected were considered to have sufficient expertise in both the diagnosis and the management of Alzheimer’s disease and sufficient recruitment capacities for this study. We asked doctors in each centre to include consecutive patients who met the criteria of the National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke/Alzheimer Disease and Related Disorders Association13 for probable or possible Alzheimer’s disease, with a mini-mental state examination14 score between 12 and 26. Participants were required to be living in the community, not participating in any other research programme, and to have a caregiver.

Investigators in the university hospitals were asked to recruit the first 30 eligible patients who agreed to take part in the study, and in the general hospitals the first 20 patients.

Generation of allocation sequence

Allocation was based on clusters rather than patients, and the sequence was concealed until interventions were assigned. The nature of the intervention meant that neither care providers nor patients could be blinded to the intervention received. Allocation to intervention was based on a randomisation procedure stratified by hospital teaching status (university or general hospital), specialty of the centre (neurology, psychiatry, or geriatric medicine), and membership to a previous national Alzheimer’s disease research programme network.15 We decided on this stratification to minimise imbalances across centres. A computer generated randomisation procedure was used by a statistician independent of the centres (Toulouse University).

Intervention

The specific care plan for Alzheimer’s disease was developed by a multidisciplinary working group (neurologists, geriatricians, psychiatrists, and general practitioners) mandated by the French Ministry of Health as part of the French government’s first plan of action for Alzheimer’s disease in 2001. It was based on data from the scientific literature1 2 3 16 17 18 and on the personal experience of members of the working group, taking into account the opinions and experience of the French Alzheimer Association, representatives of the medical and social sectors, and members of care teams.

The intervention comprised a standardised twice yearly consultation for patients and their caregivers, as well as standardised guidelines for the management of any identified problems (see web extra).19

Step 1

Because of the high level of complications throughout the course of Alzheimer’s disease, we highlighted the necessity of comprehensive standardised evaluations every six months in memory clinics, including cognitive and non-cognitive assessment. As part of the specific care plan the evaluation covered the patients’ and caregivers’ knowledge of the disease; functional dependency; progression of cognitive decline; review of drugs, including cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine; nutritional status; gait disorders and walking capacities; behavioural symptoms; caregivers’ psychological and physical health; and legal questions about the safety of the patient. We used the mini-mental state examination14 to measure cognitive decline, the activities of daily living20 and instrumental activities of daily living21 scales to measure functional capacities and the level of help required for these activities by the patient, the mini nutritional assessment22 to assess nutritional status, the neuropsychiatric inventory to evaluate behavioural disturbances,23 and the one leg balance test24 to measure gait disorders. In addition, we used the Zarit burden interview to evaluate the burden on caregivers.25

Step 2

For each area assessed we outlined a standardised management protocol that could be initiated when necessary, based on the results of the comprehensive assessment. Full details of these protocols are available at http://cm2r.enamax.net/onra/images/stories/fiches_plasa.pdf and summarised in the web extra. The use of these protocols as well as other care strategies initiated by the doctor was recorded every six months using a standardised form (see web extra).

The specific care plan for Alzheimer’s disease mainly focused on non-drug interventions, except for the item on specific drugs. For each area evaluated, we designed different types of supporting material. Written material was intended for the investigator and his or her team and reviewed the details of each intervention (evaluation tools and their interpretation, and the various possibilities of non-drug and, if appropriate, drug management). The study team also produced a CD-ROM about the care plan, including all the tools and the care management plan. This served as a resource for the training of study investigators and was supplied to each of the centres in the intervention group. A second package of written support material was intended for the caregivers and patients’ relatives, to improve their knowledge and understanding of the disease and to offer solutions to any problems. These documents also gave telephone or email contacts of available support groups and services.

The doctors in the intervention group received a training session on the specific care plan during a collective meeting before the recruitment period. A second training session was planned one year after the beginning of the study. The aim of the training sessions was to standardise practices and the use of assessment tools between centres and to present standardised care guidelines for each aspect of the disease evaluated.

Usual care

Memory clinics in France were implemented at first to help general practitioners to diagnose Alzheimer’s disease. During the study period, usual care in these clinics could be summarised as diagnosis with no systematic follow-up (unless patients made appointments) or an annual consultation (usually involving a mini-mental state examination).

In this trial we asked doctors in the memory clinics in the control arm to provide their patients with usual care. At the end of the study all documents used in the intervention arm were made available to these doctors.

Outcome measures

This study (PLASA, Plan de Soin et d’Aide dans la maladie d’Alzheimer or “specific care and assistance plan for Alzheimer disease”) tested the primary hypothesis that the specific care plan would decrease the decline in functional capacities in patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease, as measured on the Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study-activities of daily living scale.26 This tool is a caregiver rated questionnaire of 23 items assessing functional capacities, with scores ranging from 0 to 78; the highest score represents full functioning with no impairment. The questionnaire was administered to the entire cohort at inclusion and at the follow-up visits at one and two years. The secondary outcome measures were the rate of admission to institutional care and mortality.

Sample size

Our primary hypothesis was that patients in the intervention group would have a lower level of dependency at 24 months compared with patients in the control group. We considered an effect size of 0.3 to be a significant benefit in the intervention group—that is, 0.3 standard deviations less functional decline, as indicated by the change in score on the Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study-activities of daily living scale, in the intervention group compared with the control group. In our original power calculations, we determined that a sample size of 240 participants in each group would result in 90% power to detect such a difference using a two tailed test with an α level of 0.05. Taking into account the estimated rate of attrition in patients with dementia,27 28 we planned to recruit 600 patients within each group. In our sample size calculation we did not take into account the clustering effect induced by the design (randomisation of clusters). Indeed, this study was planned in 2001, before the publication of the extension of the consolidated standards of reporting trials statement to cluster randomised trials.11 Nevertheless, the statistical analysis was carried out as recommended by these international guidelines.

Statistical analysis

The primary analysis was done on an intention to treat basis—that is, included all randomised participants. We used both an imputation of mean value and a more complex approach (longitudinal mixed model) that does not impute data in the case of missing outcomes.

As we computed the Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study-activities of daily living scores by adding item responses, data were missing at the level of both items and scores. If five or fewer items were missing, we derived the score from non-missing items and reweighted the score to recover its true range, if more than five items were missing, we considered the score as missing. We then carried out the primary analysis using two statistical strategies, both done in agreement with the intention to treat principle. Firstly, we assessed the primary outcome by considering the crude change in the Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study-activities of daily living score—that is, the score at 24 months minus the score at baseline. A missing score was then handled by imputing the mean value (estimated from available data) of the group to which the patient was allocated. We then used a mixed model to analyse data, thus taking into account the correlation within patients and the clustering effect. Secondly, we used a longitudinal mixed model to analyse the primary outcome for data at baseline and at 12 and 24 months, which took into account the two levels of correlation: between repeated observations of individual patients and between patients within centres. In this second approach, we did not replace missing scores on the Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study-activities of daily living scale. The statistical model was then used to assess available data only.

For each group we estimated the intraclass correlation coefficient. We used Cox marginal models to assess time to admission to institutional care and death, taking into account the clustering effect. Statistical analyses were carried out using SAS software version 9.1.

Results

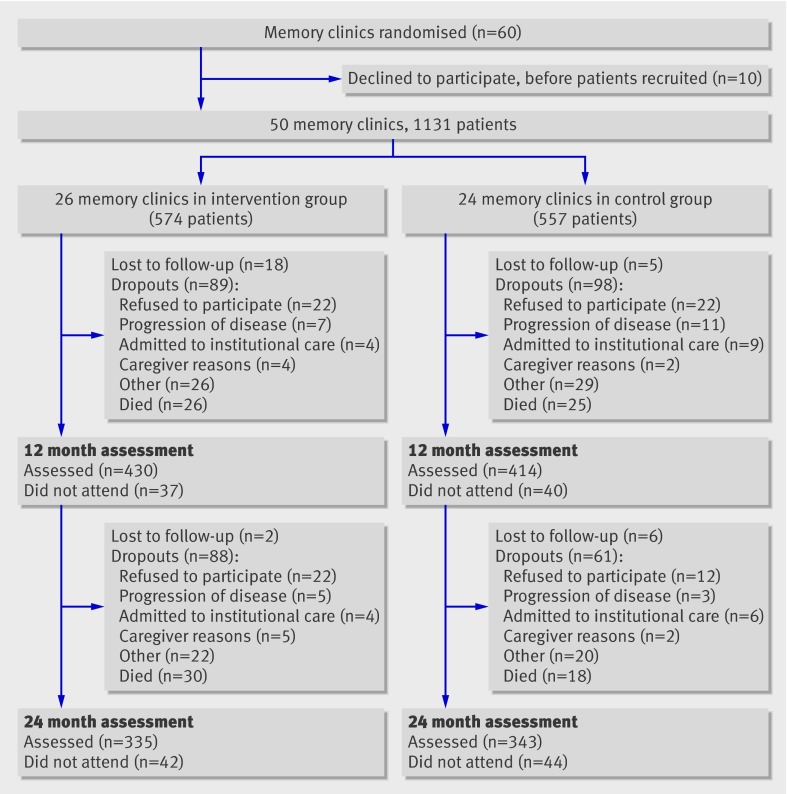

Sixty centres initially agreed to participate in this trial. Ten centres (three in the intervention group, seven in the control group) subsequently withdrew their consent, after randomisation and before the inclusion of patients. Thus, 26 memory clinics (10 in university hospitals, 16 in general hospitals) were randomised to the intervention group and 24 memory clinics (10 in university hospitals, 14 in general hospitals) to the control group (figure). Overall, 1131 patients were recruited in these 50 memory clinics between June 2003 and July 2005.

Flow of participants through study

Table 1 lists the baseline characteristics of the centres and participants by treatment group. The groups were well balanced. Dementia was mild to moderate as shown by an overall mean mini-mental state examination score of 19.7 (SD 4.0). Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors were widely prescribed; 79.0% (893/1131) of the entire cohort was receiving them at baseline before the first visit.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of memory clinics, patients with Alzheimer’s disease, and caregivers randomised to a specific care plan for the management of Alzheimer’s disease or to usual care (control). Values are numbers (percentages) unless stated otherwise

| Characteristics | Intervention group | Control group |

|---|---|---|

| Memory clinics: | n=26 | n=24 |

| University hospital | 10 (39) | 10 (42) |

| General hospital | 16 (62) | 14 (58) |

| Member of Alzheimer’s disease research programme network | 6 (23) | 7 (29) |

| No (interquartile range) of patients | 20 (18-30) | 22 (19-27) |

| Median (interquartile range) time to include first patient (months) | 0.7 (0.5-0.8) | 0.7 (0.6-0.9) |

| Patients: | n=574 | n=557 |

| Mean (SD) age (years) | 80.2 (5.9) | 80.2 (5.6) |

| Women | 382 (66.5) | 395 (70.9) |

| Median (interquartile range) duration of disease (years) | 3 (2-5) | 3 (2-5) |

| Median (interquartile range) time since diagnosis (years) | 1 (0-2) | 1 (0-2) |

| Mean (SD) MMSE score (0-30)* | 19.5 (3.9) | 20.0 (4.1) |

| Use of cholinesterase inhibitors at baseline | 439 (76.5) | 454 (81.5) |

| Median (interquartile range) No of non-dementia related drugs | 4 (2-6) | 4 (2-5) |

| Median No (interquartile range) of chronic diseases | 2 (1-3) | 2 (1-3) |

| Living arrangements: | ||

| Live alone | 187 (32.6) | 163 (29.3) |

| Live with spouse | 305 (53.1) | 289 (51.9) |

| Other | 82 (14.3) | 105 (18.8) |

| Caregivers: | n=574 | n=557 |

| Mean (SD) age (years) | 64.6 (13.7) | 65.1 (13.6) |

| Women | 380 (66.2) | 339 (61.0) |

| Live with patient | 309 (54.0) | 332 (59.8) |

| Spouse of patient | 271 (47.2) | 278 (49.9) |

| Child of patient | 255 (44.4) | 234 (42.0) |

| Other relationship with patient | 48 (8.4) | 45 (8.1) |

MMSE=mini-mental state examination.

*Higher scores represent better function.

In total, 58.4% (n=335) of patients in the intervention group and 61.6% (n=343) in the control group were assessed at the two year follow-up visit. Death was the main reason for early stopping of the study (56 in intervention group, 43 in control group). The reasons for stopping did not differ significantly between the groups at 24 months.

Disease progression and main outcome measures

Functional decline did not differ significantly between the two groups over the two years of follow-up, regardless of the method used for data analysis (table 2). The annual decrease in the Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study-activities of daily living score in the control group was estimated at −5.96 (95% confidence interval −7.05 to −4.86) in the control group and −5.73 (−6.89 to −4.57) in the intervention group (P=0.78; table 2). After imputation of group mean values for missing data, the intraclass correlation coefficient for the intervention group was 0.093 (95% confidence interval 0.042 to 0.193) and for the control group was 0.091 (0.040 to 0.193).

Table 2.

Mean scores on Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study-activities of daily living (ADCS-ADL) scale at baseline and at 12 and 24 months. Values are means (standard deviations) unless stated otherwise

| Variables | ADCS-ADL score (0-78) | Crude change or estimate | P values | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 12 months | 24 months | |||

| Descriptive data*: | |||||

| Intervention group | 53.0 (15.6); n=548 | 49.4 (17.6); n=328 | 43.4 (18.4); n=224 | — | — |

| Control group | 51.1 (16.3); n=546 | 46.7 (17.1); n=315 | 42.4 (18.1); n=257 | — | — |

| Analysis using imputation of group mean values for missing data†: | |||||

| Intervention group (n=574) | 53.0 (15.2) | 49.5 (13.4) | 43.4 (11.6) | −9.6 (15.1)‡ | — |

| Control group (n=557) | 51.1 (16.2) | 46.5 (14.2) | 42.0 (13.0) | −9.1 (15.5)‡ | 0.990 |

| Analysis with no imputation for missing data§: | |||||

| Group effect (intervention v control) | — | — | — | 1.157 | 0.46 |

| Time effect (years) | — | — | — | −5.956 | <0.001 |

| Interaction group×time | — | — | — | 0.226 | 0.78 |

*Only patients with scores.

†Missing data handled by imputing mean value of group to which patients were allocated plus analysis using mixed model, taking into account clustering effect.

‡Score at 24 months minus score at baseline.

§Mixed model taking into account both longitudinal nature of data and correlation induced by randomisation of clusters. Intervention effect assessed through interaction term that expresses how intervention influences time effect. Annual decrease for ADCS-ADL score was thus −5.96 in control group versus −5.73 in intervention group.

The risk of being admitted to institutional care or mortality did not differ significantly between the intervention group compared with the control group at two years (admission to institutional care, hazard ratio 0.95, 95% confidence interval 0.67 to 1.36, P=0.79; mortality, 0.80, 0.51 to 1.25, P=0.32). For the 221 cases admitted to institutional care the mean time to admission did not differ between the groups: 371.2 (SD 196.0) days in the intervention group compared with 368.1 (SD 210.8) days in the control group (P=0.9088). The reasons for admission did, however, differ between the groups. Patients in the control group were mostly admitted because of worsening medical conditions (61.5% v 38.5% in intervention group) whereas patients in the intervention group were mostly admitted due to reasons related to caregivers (70.59% v 29.41% in control group; P=0.0046).

Table 3 summarises progression of the disease, as measured by the standardised tools. As a result of the study methodology, these data were only collected in the intervention group. At two years the decline in activities of daily living was −1.14 (95% confidence interval −1.27 to −1.02) and in instrumental activities of daily living was −1.86 (−2.07 to −1.65).

Table 3.

Results of assessments in intervention group during follow-up. Values are means (standard errors)

| Mixed model | Baseline (n=574) | 12 months (n=430) | 24 months (n=335) |

|---|---|---|---|

| ADL score (0-6)* | 5.35 (0.06); n=574 | 4.79 (0.07); n=428 | 4.21 (0.09); n=331 |

| IADL score (0-8)* | 4.26 (0.17); n=573 | 3.18 (0.17); n=415 | 2.40 (0.18); n=320 |

| MMSE score (0-30)* | 19.44 (0.18); n=574 | 17.90 (0.23); n=415 | 15.75 (0.29); n=326 |

| MNA score (0-30)† | 23.87 (0.22); n=571 | 23.30 (0.22); n=423 | 22.73 (0.25); n=324 |

| NPI score (0-144)‡ | 18.26 (1.20); n=573 | 19.05 (1.17); n=425 | 19.85 (1.26); n=329 |

| Zarit burden interview score (0-88)‡ | 24.14 (0.92); n=573 | 26.62 (0.93); n=423 | 29.10 (1.06); n=324 |

MMSE=mini-mental state examination; ADL=activities of daily living; IADL=instrumental activities of daily living; MNA=mini nutritional assessment; NPI=neuropsychiatric inventory.

*Higher scores represent better function.

†Higher scores represent better nutritional status.

‡Higher scores represent worse symptoms.

Table 4shows the frequency of use of the standardised care protocols. In the intervention group at baseline a median of six protocols were used per patient. This number tended to decrease during follow-up (median of three protocols used at both one and two years). The use of protocols relating to the disclosure of the diagnosis and knowledge of the disease decreased noticeably during follow-up. A similar situation was seen for protocols relating to management of nutrition, probably due to the stability of nutritional status in this group during follow-up. Behavioural problems increased by about 1.6 points on the neuropsychiatric inventory scale during the two years, but the use of protocols relating to such problems decreased over time: 31.8% (182/574) at baseline and 21.9% (73/335) at two years. In line with the increase in functional dependency, the use of protocols for functional decline, respite care and admission to institutional care increased during the study.

Table 4.

Frequency of use and type of care management protocols in intervention group during follow-up. Values are numbers (percentages) unless stated otherwise

| Protocols | Baseline (n=574) | 12 months (n=430) | 24 months (n=335) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median (interquartile range) No used per patient | 6 (4-9) | 3 (1-6) | 3 (1-5) |

| Type: | |||

| Disclosure of diagnosis | 392 (68.3) | 23 (5.4) | 5 (1.5) |

| Verification of patient’s knowledge of the disease | 415 (72.4) | 37 (8.6) | 7 (2.1) |

| Verification of caregivers’ knowledge of the disease | 466 (81.5) | 207 (48.4) | 156 (46.7) |

| Nutritional status | 223 (38.9) | 115 (26.9) | 79 (23.7) |

| Exercise training | 260 (45.4) | 147 (34.4) | 104 (31.1) |

| Gait disorders and walking capacities | 151 (26.4) | 87 (20.3) | 71 (21.3) |

| Functional dependency | 91 (15.9) | 115 (26.9) | 92 (27.5) |

| Behavioural symptoms (non-drug or drug related) | 182 (31.8) | 114 (26.6) | 73 (21.9) |

| Depression | 178 (31.1) | 81 (18.9) | 53 (15.9) |

| Sleep disorders | 108 (18.9) | 58 (13.6) | 28 (8.4) |

| Home care services | 218 (38.2) | 138 (32.2) | 93 (27.8) |

| Respite care | 86 (15.0) | 71 (16.6) | 69 (20.7) |

| Admission to institutional care | 45 (7.9) | 41 (9.6) | 45 (13.5) |

Discussion

The results of the primary intention to treat analysis of this trial showed no difference in the rate of functional decline, as measured by the Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study-activities of daily living scale, between patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease randomised to a specific care plan and those randomised to usual care. To our knowledge, this is the first nationwide randomised clinical trial to test the effectiveness of guideline based care interventions for Alzheimer’s disease delivered in memory clinics. We chose to carry out this trial in memory clinics because in many countries, memory clinics with multidisciplinary teams have been established to facilitate the early detection and management of dementia. Although some claim that these clinics merely prescribe and monitor drug treatment, such clinics are becoming increasingly integrated into standard care for dementia in many countries. Memory clinics are also more knowledgeable about the management of complex conditions associated with their specialty.

After randomisation of the centres, the intervention and control groups were well balanced at baseline. The annual rate of change in Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study-activities of daily living scores was −5.73 in the intervention group compared with −5.96 in the control group. This rate of progression remains globally similar to the changes seen in most patients enrolled in placebo groups of clinical trials.29 A phase II trial testing the efficacy of tarenflurbil reported an annual rate of change in Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study-activities of daily living score of −8.31 at 12 months in patients with Alzheimer’s disease randomised to the placebo group.30 As in our study, most of the patients in the placebo group (97%) in the tarenflurbil trial were users of acetylcholinesterase inhibitors. Another study reported a deterioration of the Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study-activities of daily living score of 6.95 points at 12 months in 281 patients in the placebo group of a study evaluating the efficacy of growth hormone secretagogue (71.2% were using anti-dementia drugs at inclusion).31 The statistical analyses in these studies were similar to ours, using an intention to treat method. It must be noted, however, that we included patients regardless of age or comorbidities, unlike drug trials, which have more strict inclusion criteria. Our trial was a pragmatic trial as defined by previous investigators.32 Our population is therefore probably closer to a “real world” situation. In another randomised controlled trial, the researchers tested the effectiveness of a collaborative care model to improve the quality of care for patients with Alzheimer’s disease in primary care.7 One hundred and fifty three patients were randomised. For one year the team, led by an advanced practice nurse working with the patients’ family caregiver, used standard protocols to identify, monitor, and treat behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia, stressing non-drug management in the intervention group. The researchers showed a significant improvement in behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia in this group. However, cognitive and functional decline did not differ between the groups. The annual rate of change in Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study-activities of daily living scores reported by researchers in their control group was −4.2 at 12 months, but the last observation carried forward method was used in their analysis, which is a potential source of bias. Indeed, the last observation carried forward technique assumes that patients remain stable over time from the time of drop out, which is unlikely in a chronic progressive condition such as Alzheimer’s disease. This technique therefore underestimates the rate of decline and some researchers are beginning to doubt this type of analysis in the specialty of dementia.33 We used both an imputation of mean value and a more complex approach (longitudinal mixed model), which does not impute data in the case of missing outcomes.

Strengths and weaknesses of the study

This work was a national multicentre study, which enabled the follow-up of a population of patients with Alzheimer’s disease living in both urban and rural (through the general hospitals) environments. In France, as only specialists are allowed to initiate treatments for dementia there is no real difference between patients with Alzheimer’s disease followed in these centres and patients followed in other clinical settings. We must, however, stress that this population was not representative of all patients with Alzheimer’s disease because we included only community dwelling patients with an identified caregiver. Regarding the selection of patients within centres, we asked each centre to include all consecutive outpatients presenting to the centre and meeting the study inclusion criteria during the study period. The inclusion period took longer than expected. Despite the time spent on administrative issues that delayed the opening of some centres, we cannot completely eliminate the possibility that some investigators did not strictly select all consecutive eligible patients. This deviation was probably most often related to time constraints: an investigator who sees several potentially eligible patients may decide to include only the first owing to lack of time. Also, it is possible that investigators selected a priori those patients who were more likely to be compliant to the study protocol, especially as the investigators knew the type of intervention they had to provide. However secondary bias associated with this type of selection is probably not a problem in our study given the fact that patients in both groups were comparable at baseline.

Some limitations must be discussed when interpreting the lack of effect of the intervention in our study. The first is a contamination between groups due to the long duration of the study and recruitment period. In 2004, the French government released a second plan of action for Alzheimer’s disease, which emphasised the broad implementation of memory clinics as well as structured follow-up of patients. To investigate the potential effects of this on the study results, we recovered post hoc the characteristics of the frequency of follow-up and management procedures in memory clinics from the control arm. The results indicated that most of the memory clinics proposed regular follow-up during the trial. In fact, a visit at six months was organised in 18 of the 24 centres, with systematic evaluation of the mini-mental state examination carried out by all centres (dependency was evaluated in a standardised manner in 12 of the 18 centres). The six other centres systematically carried out an annual consultation, with, in all cases standardised evaluations of the mini-mental state examination and of dependency. The other evaluation tools were rarely used.

The second limitation concerns the adherence to and diversity of programme recommendations. Reductions in adherence to the interventional protocols would be expected to reduce the effectiveness of the interventions. Although the investigators recorded the frequency of use of the standardised protocols, it was difficult to assess overall adherence to the intervention because of its complexity and multifaceted nature. Due to the diversity of the intervention, although the data collection form relative to the intervention protocols was standardised, the choice of the type of specific interventions used and the timing of their use were at the discretion of the doctor. Moreover, we do not know if the proposed management strategies were adequately implemented at home and how receptive caregivers or general practitioners were to our written instructions. Furthermore, assessors were not blinded to intervention status; blinding is more difficult in non-drug trials.34 Finally, we did not take into account the clustering effect in our sample size calculation. Data were, however, analysed taking into account this clustering effect and we can consider that lack of power probably did not result in the non-significant difference between groups.

Conclusions

In this randomised clinical trial of 1131 community dwelling older patients with Alzheimer’s disease, we could find no clear benefit of comprehensive evaluation and targeted management every six months in memory clinics for reducing long term functional decline. This finding underlines the fact that this kind of broad intervention does not convey benefit in activities of daily living and may have little public health value. Alzheimer’s disease is a complex and heterogeneous condition. Consequently, to have a beneficial effect on disease progression it may be that interventions must be targeted towards patients at particular risk of decline or we may need to develop a more effective intervention and ensure that it is correctly implemented in all patients. This study suggests that the contribution of advice to caregivers and general practitioners alone is not sufficient. Future research is needed to determine whether functional decline can be improved by more direct involvement of general practitioners or by using case manager programmes.

What is already known on this topic

Non-drug treatments, including patient education, social support, and regular follow-up, are recommended to manage Alzheimer’s disease

What this study adds

Comprehensive evaluations and targeted management of patients with Alzheimer’s disease in memory clinics every six months did not slow functional decline

Future focus may be on those patients with particular risks of cognitive and functional decline

Future research needs to determine the benefits on functional decline of more direct involvement of general practitioners or using case manager programmes

We thank the investigators from the following hospitals for help with data collection for the PLASA study: Albi General Hospital: Alain Quinçon; Ales General Hospital: Liliane Peju; Anger University Hospital: Gilles Berrut; Annecy General Hospital: Francoise Picot; Bar Le Duc General Hospital: Gabrielle De Guio; Bordeaux University Hospital: Muriel Rainfray; Brest University Hospital: Armelle Gentric; Carcassonne General Hospital: Christian Tannier; Carvin General Hospital: Nathalie Taillez; Chambéry General Hospital: Françoise Declippeleir, Claude Hohn; Champcueil General Hospital: Marie Françoise Maugourd; Dieppe General Hospital: Thierry Pesque; Elbeuf General Hospital: Thibault Simon; Grasse General Hospital: Jacques Ribiere; Grenoble University Hospital: Alain Franco; Lannemezan General Hospital: Serge Bordes; Lavaur General Hospital: Françoise De Pemille; Le Havre General Hospital: Isabelle Landrin; Lens General Hospital: Olivier Senechal; Lille University Hospital: Jean Roche, Florence Pasquier; Lyon University Hospital: Marc Bonnefoy; Marseille University Hospital: Bernard Michel; Montpellier University Hospital: Claude Jeandel, Jacques Touchon; Nice General Hospital: Jean Yves Giordana; Nice University Hospital: Patrice Brocker, Philippe Robert, Olivier Guerin; Nimes General Hospital: Denise Strubel; Niort General Hospital: Jean Albert Chaumier; Paris General Hospital: Bernard Durand-Gasselin; Paris General Hospital: Michel Samson; Paris University Hospital: Joel Belmin, Sylvie Legrain, Anne Sophie Rigaud, Laurent Teillet, Marc Verny, Sylvie Pariel; Pau General Hospital: François de la Fournière; Plaisir General Hospital: Olivier Drunat; Reims University Hospital: François Blanchard; Rennes University Hospital: Pierre Jouanny; Roubaix General Hospital: Pierre Forzy; Rouen General Hospital: Moynot; Rouen University Hospital: Philippe Chassagne, Didier Hannequin, Frédérique Dugny, Caroline Levasseur; Saint Dizier General Hospital: Anne Aubertin; Sezanne General Hospital: Elisabeth Quignard; Valenciennes General Hospital: Pascale Leurs; Vannes General Hospital: Christian Le Provost; Villejuif General Hospital: Dorin Feteanu, Christophe Trivalle; Wasquehal General Hospital: Frigard. We also thank M C Cazes for administrative support and Julie Léger for her statistical help. The CD-ROM was produced with financial support from the French Ministry of Health.

Contributors: FN, SA, SG-G, and BV conceived and designed the study. SG-G, SA, and FN acquired the data. SA, FN, SG-G, CC, BG, and BV analysed and interpreted the data. FN, SA, NC, and BV prepared the manuscript. BG provided information on independent statistical analysis. All authors critically reviewed the manuscript and approved the final version to be published, had full access to all data in the study, and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. FN, SA, SG-G, and BV are guarantors.

Funding: This study was supported by a grant from the French Ministry of Health (PHRC 02-006-01). The sponsor had no role in the study.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the unified competing interest form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare (1) no financial support for the submitted work from anyone other than their employer; (2) no financial relationships with commercial entities that might have an interest in the submitted work; (3) no spouses, partners, or children with relationships with commercial entities that might have an interest in the submitted work; and (4) no non-financial interests that may be relevant to the submitted work.

Ethical approval: This study was approved by the institutional review board and ethics committee of Toulouse University (France).

Data sharing: No additional data available.

Cite this as: BMJ 2010;340:c2466

Web Extra. Extra material supplied by the author

Summary of intervention

Graphical depiction of intervention

Standardised record form

References

- 1.Lyketsos CG, Colenda CC, Beck C, Blank K, Doraiswamy MP, Kalunian DA, et al. Task Force of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry. Position statement of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry regarding principles of care for patients with dementia resulting from Alzheimer disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2006;14:561-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Small GW, Rabins PV, Barry PP, Buckholtz NS, DeKosky ST, Ferris SH, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of Alzheimer disease and related disorders. Consensus statement of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry, the Alzheimer’s Association, and the American Geriatrics Society. JAMA 1997;278:1363-71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grossberg GT, Desai AK. Management of Alzheimer’s disease. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2003;58:331-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Waldemar G, Dubois B, Emre M, Georges J, McKeith IG, Rossor M, et al. Recommendations for the diagnosis and management of Alzheimer’s disease and other disorders associated with dementia: EFNS guideline. Eur J Neurol 2007;14:e1-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gifford DR, Holloway RG, Frankel MR, Albright CL, Meyerson R, Griggs RC, et al. Improving adherence to dementia guidelines through education and opinion leaders: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med 1999;131:237-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chodosh J, Mittman BS, Connor KI, Vassar SD, Lee ML, DeMonte RW, et al. Caring for patients with dementia: how good is the quality of care? Results from three health systems. J Am Geriatr Soc 2007;55:1260-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Callahan CM, Boustani MA, Unverzagt FW, Austrom MG, Damush TM, Perkins AJ, et al. Effectiveness of collaborative care for older adults with Alzheimer disease in primary care: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2006;295:2148-57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vickrey BG, Mittman BS, Connor KI, Pearson ML, Della Penna RD, Ganiats TG, et al. The effect of a disease management intervention on quality and outcomes of dementia care: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med 2006;145:713-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chenoweth L, King MT, Jeon YH, Brodaty H, Stein-Parbury J, Norman R, et al. Caring for Aged Dementia Care Resident Study (CADRES) of person-centred care, dementia-care mapping, and usual care in dementia: a cluster-randomised trial. Lancet Neurol 2009;8:317-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moher D, Schulz KF, Altman DG, for the CONSORT Group. The CONSORT statement: revised recommendations for improving the quality of reports of parallel-group randomised trials. Lancet 2001;357:1191-4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Campbell MK, Elbourne DR, Altman DG, for the CONSORT group. The CONSORT statement: extension to cluster randomised trials. BMJ 2004;328:702-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boutron I, Moher D, Altman DG, Schulz KF, Ravaud P, for the CONSORT Group. Extending the CONSORT statement to randomized trials of nonpharmacologic treatment: explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med 2008;148:295-309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of the Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurology 1984;34:939-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 1975;12:189-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gillette-Guyonnet S, Nourhashémi F, Andrieu S, Cantet C, Micas M, Ousset PJ, et al. The REAL.FR research program on Alzheimer’s disease and its management: methods and preliminary results. J Nutr Health Aging 2003;7:91-6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fillit H, Cummings J. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of Alzheimer’s disease in a managed care setting: Part II—pharmacologic therapy. Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) Managed Care Advisory Council. Manag Care Interface 2000;13:51-6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harvey RJ. A review and commentary on a sample of 15 UK guidelines for the drug treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 1999;14:249-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Doody RS, Stevens JC, Beck C, Dubinsky RM, Kaye JA, Gwyther L, et al. Practice parameter: management of dementia (an evidence-based review). Report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology 2001;56:1154-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Perera R, Heneghan C, Yudkin P. Graphical method for depicting randomised trials of complex interventions. BMJ 2007;334:127-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Katz S, Ford AB, Moskowitz RW, Jackson BA, Jaffe MW. The index of ADL: a standardized measure of biological and psychosocial function. JAMA 1963;185:914-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lawton MP, Brody EM. Assessment of older people: self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist 1969;9:179-86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guigoz Y, Vellas B, Garry PJ. Assessing the nutritional status of the elderly: the mini nutritional assessment as part of the geriatric evaluation. Nutr Rev 1996;54:59-65S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cummings JL, Mega M, Gray R, Rosenberg-Thompson S, Carusi DA, Gornbein J. The neuropsychiatric inventory: comprehensive assessment of psychopathology in dementia. Neurology 1994;44:2308-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vellas B, Wayne SJ, Romero L, Baumgartner RN, Rubenstein LZ, Garry PJ. One-leg balance is an important predictor of injurious falls in older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc 1997;45:735-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zarit SH, Todd PA, Zarit JM. Subjective burden of husbands and wives as caregivers: a longitudinal study. Gerontologist 1986;26:260-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Galasko D, Benett D, Sano M, Ernesto C, Thomas R, Grundman M, et al. An inventory to assess activities of daily living for clinical trials in Alzheimer’s disease. The Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 1997;11(suppl 2):33-9S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fillenbaum GG, Peterson B, Welsh-Bohmer KA, Kukull WA, Heyman A. Progression of Alzheimer’s disease in black and white patients: the CERAD experience, part XVI. Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurology 1998;51:154-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Koss E, Peterson B, Fillenbaum GG. Determinants of attrition in a natural history study of Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 1999;13:209-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schneider LS, Sano M. Current Alzheimer’s disease clinical trials: methods and placebo outcomes. Alzheimers Dement 2009;5:388-97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wilcock GK, Black SE, Hendrix SB, Zavitz KH, Swabb EA, Laughlin MA. Efficacy and safety of tarenflurbil in mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease: a randomised phase II trial. Lancet Neurol 2008;7:483-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sevigny JJ, Ryan JM, van Dyck CH, Peng Y, Lines CR, Nessly ML; MK-677 Protocol 30 Study Group. Growth hormone secretagogue MK-677. No clinical effect on AD progression in a randomized trial. Neurology 2008;71:1702-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schwartz D, Lellouch J. Explanatory and pragmatic attitudes in therapeutical trials. J Chronic Dis 1967;20:637-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Molnar FJ, Hutton B, Fergusson D. Does analysis using “last observation carried forward” introduce bias in dementia research? CMAJ 2008;179:751-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Boutron I, Tubach F, Giraudeau B, Ravaud P. Blinding was judged more difficult to achieve and maintain in nonpharmacologic than pharmacologic trials. J Clin Epidemiol 2004;57:543-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Summary of intervention

Graphical depiction of intervention

Standardised record form