Abstract

Several human monoclonal antibodies (hmAbs) exhibit relatively potent and broad neutralizing activity against HIV-1, but there has not been much success in using them as potential therapeutics. We have previously hypothesized and demonstrated that small engineered antibodies can target highly conserved epitopes that are not accessible by full-size antibodies. However, their potency has not been comparatively evaluated with known HIV-1-neutralizing hmAbs against large panels of primary isolates. We report here the inhibitory activity of an engineered single chain antibody fragment (scFv), m9, against several panels of primary HIV-1 isolates from group M (clades A–G) using cell-free and cell-associated virus in cell line-based assays. M9 was much more potent than scFv 17b, and more potent than or comparable to the best-characterized broadly neutralizing hmAbs IgG1 b12, 2G12, 2F5 and 4e10. It also inhibited cell-to-cell transmission of HIV-1 with higher potency than enfuvirtide (t-20, Fuzeon). M9 competed with a sulfated CCR5 N-terminal peptide for binding to gp120-CD4 complex, suggesting an overlapping epitope with the coreceptor binding site. M9 did not react with phosphatidylserine (pS) and cardiolipin (CL), nor did it react with a panel of autoantigens in an antinuclear autoantibody (ANA) assay. We further found that escape mutants resistant to m9 did not emerge in an immune selection assay. these results suggest that m9 is a novel anti-HIV-1 candidate with potential therapeutic or prophylactic properties, and its epitope is a new target for drug or vaccine development.

Key words: HIV, AIDS, antibodies, scFv, microbicides, therapeutics, vaccines

Introduction

Several human monoclonal antibodies (hmAbs) that target conserved structures of the HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein (Env) exhibit relatively potent and broad HIV-1 neutralizing activity. 2F5,1 and 4E10,2,3 bind to conserved linear epitopes in the membrane proximal external region of gp41; 4E10 has the broadest cross-reactivity, although its neutralizing activity appears to be assay dependent.4 B12 binds to a conformationally invariant surface on gp120 and its epitope overlaps the CD4-binding site (CD4bs).5–7 2G12 binds to a conserved carbohydrate epitope on gp120.8 These antibodies have been studied in animal models and human clinical trials. They showed potential as prophylactics, but have not demonstrated much promise as therapeutics.9–12 In a mouse model, b12 treatment allowed very rapid virus escape.13 In human clinical trials, 2F5, 4E10 and 2G12 were not able to significantly reduce viremia for prolonged periods of time. 2G12 was recently shown to affect HIV-1 replication in humans, but the effect was weak.9 It appears that these antibodies do not exhibit potency and breadth of neutralization to such an extent that they can significantly reduce virus replication and inhibit or block the generation of resistant virus. One possible reason is that HIV-1 has acquired the ability to escape neutralization by antibodies generated by the immune system using a variety of mechanisms, including sterically restricted access to conserved epitopes.14 Thus, the virus could quickly develop resistance to naturally occurring neutralizing HIV-1-specific antibodies; however, engineered antibody fragments of smaller size may be able to gain access to the highly guarded conserved structures of the Env. Such small fragments targeting sterically restricted regions on the Env could exhibit neutralization activity superior to large antibody molecules. In addition, small antibody fragments may have advantages over full-length antibody molecules in penetrating lymphoid tissues where the virus replicates.

Antibodies to CD4-induced (CD4i) epitopes are frequently found in HIV-1-infected individuals, and are thought to primarily target the coreceptor binding site.15 These polyclonal antibodies can bind and potently neutralize different subtypes of HIV-1 and the divergent HIV-2 in the presence of soluble CD4 (sCD4), indicating that the CD4i coreceptor binding surface is highly conserved.15 On average though, these polyclonal antibodies are weak neutralizers in the absence of sCD4. Similarly, anti-CD4i mAbs exhibit limited neutralizing activity in vitro, likely due to restricted access to their epitopes.14 Antibody fragments derived from anti-CD4i mAbs that target the coreceptor binding site, e.g., Fab X5 and Fab m16, have been shown to potently neutralize a variety of HIV-1 primary isolates from different clades.16,17 The crystal structure of an HIV-1 gp120 core complexed with CD4 and Fab X5 showed that the epitope of Fab X5 includes highly conserved gp120 amino acid residues.18 The functional importance for virus entry and the sequence conservation make the coreceptor binding site an attractive potential target for development of antibody-based and small molecule entry inhibitors.

We have previously reported the selection of m9 from an scFv X5 mutant library by sequential antigen panning, and its improved binding and neutralization activities.19 M9 differed from its parental X5 at three residues: S181T, D229G and T251N. These three changes substantially enhance m9’s breadth and potency over the parental X5, but the potency of m9 has not been comparatively evaluated with the best-characterized HIV-1-neutralizing hmAbs against large panels of primary isolates. Here, we report m9’s inhibitory activity against several panels of primary HIV-1 isolates from group M (clades A-G) using cell-free and cell-associated virus in cell line-based assays. M9 exhibited superior activity compared to the best-characterized HIV-1-neutralizing hmAbs IgG1 b12, 2F5, 4E10 and 2G12, and scFv 17b. It also inhibited cell-to-cell transmission of HIV-1 with higher potency than enfuvirtide (T-20, Fuzeon). To explore the mechanism of m9’s potent neutralization activity, we measured the binding of m9 to gp120-CD4 complex in the presence of a sulfated CCR5 N-terminal peptide (R5Nt). Unlike X5 and 17b, m9 competed with R5Nt for binding to the gp120-CD4 complex, suggesting that the m9 epitope overlaps to a greater extent with the coreceptor binding site compared to those of 17b and the parental X5. We further tested m9 in an immune selection assay for generation of m9-resistant virus mutants, and in the antinuclear autoantibody (ANA) assay for the autoreactivity of m9 with a panel of autoantigens. The results suggest that m9 is a novel anti-HIV-1 candidate with potential therapeutic or prophylactic properties, and its conserved epitope is a new target for drug or vaccine development.

Results

M9 potently inhibited the entry of cell-free HIV-1 in cell-line based assays

As previously reported, we isolated m6 and m9 from a scFv X5 mutant library using sequential antigen panning. Both m6 and m9 exhibited broad cross-reactivity in neutralizing HIV-1 primary isolates, but m9 exhibited slightly greater potency than m6 as measured by a luciferase reporter assay for HIV infection.19 Therefore, we conducted extensive testing of m9 neutralization activity in cell line-based pseudotyped virus neutralization assays to investigate its potential as an HIV-1 entry inhibitor. First, we tested m9 alone with two lab-adapted isolates (HXB-2 and JR-CSF) and five clade B and five clade C primary isolates in a U87 cell line-based assay, and with a panel of HIV-1 primary isolates from clades A, B, C, D and E in HOS cell line-based assay (Table 1). M9 neutralized 10 out of 12 isolates tested with IC50 ranging from 1 to 335 nM (the highest concentration used was 439 nM) in a U87 cell line-based assay. MuLV was used as a control in this assay. In the HOS cell line-based assay, m9 neutralized 9 out of 11 isolates tested. The clade A isolate (92UG029) and clade E isolate (CM243) were not sensitive to m9 at the highest concentration used. Human IgG from healthy individuals was used as a negative control. These data provide evidence for the broad cross-reactivity of m9.

Table 1.

Neutralization activity of m9 in U87 or HOS cell line-based assays against HIV-1 primary isolates from clades A, B, C, D and E

| HIV-1 isolate | Clade | Tropism | IC50 (nM) in U87 cells (R5/X4) | HIV-1 isolate | Clade | Tropism | IC50 (nM) in HOSCD4CCR5 cells |

| HXB-2 | B | CXCR4 | 1 | 92UG029 | A | R5 | >1,650 |

| JR-CSF | B | CCR5 | 151 | 89.6 | B | Dual | 171 |

| R5_1 | B | CCR5 | 92 | 92Ht593.1 | B | R5 | 483 |

| R5_2 | B | CCR5 | 49 | AD8 | B | R5 | 394 |

| DM_1 | B | Dual | 100/109 | R2 | B | R5 | 165 |

| DM_2 | B | Dual | 62/209 | BaL | B | R5 | 198 |

| DM_3 | B | Dual | 17/108 | JRCSF | B | R5 | 288 |

| R5_2 | C | CCR5 | >439 | JRFL | B | R5 | 388 |

| R5_4 | C | CCR5 | 158 | 93MW965.26 | C | R5 | 702 |

| DM_1 | C | Dual | 164/335 | Z2Z6 | D | R5 | 245 |

| DM_2 | C | Dual | >439 | CM243 | E | R5 | >1,650 |

| DM_3 | C | Dual | 170 | Percentage neutralized (%) | 82 | ||

| Percentage neutrallzed (%) | 83 | ||||||

Seven primary isolates from clade B and five from clade C were tested using U87 CCR5/CXCR4 as target cells in the PhenoSense Entry assay as described in Materials and Methods. The highest concentration tested in this assay was 439 nM (=13.3 µg/ml). A panel of 11 primary isolates from clade A, B, C, D and E were tested in a pseudovirus assay using HOSCD4CCR5 as target cells. highest concentration tested in this assay was 1,650 nM (=50 µg/ml). Percentage neutralized (%) is the percentage of isolates with IC50 below the maximum antibody concentration tested in each assay (439 nM in U87 cell line-based assay and 1,650 nM in HOSCD4CCR5 cell line-based assay).

Further pseudotyped virus neutralization assays were carried out to test m9 potency and neutralization breadth in comparison with scFv 17b and the four best-characterized broadly neutralizing mAbs b12, 2G12, 2F5 and 4E10. ScFv 17b is well characterized CD4i antibody and its epitope overlaps the coreceptor binding site. Although IgG1 17b is a weak neutralizing antibody, scFv 17b was reported to be relatively potent,14 especially as an sCD4-scFv 17b fusion protein.20 We tested m9 side-by-side with scFv 17b and the four mAbs against 15 Env cloned pseudoviruses from HIV-1 clades A, B and C in a TZM-bl cell line-based assay (Table 2). M9 was shown to be significantly more potent than scFv 17b, and also more potent than b12, 2G12, 2F5 in neutralizing this panel of primary isolates from different clades. M9 neutralized all isolates; however, the IC50 for one clade A isolate, Q259.d2.17, was about 1 µM (1,053 nM). ScFv 17b neutralized only two isolates from this panel (7%). 2G12 neutralized four clade B isolates (27%), but did not neutralize clades C and A isolates. Both b12 and 2F5 neutralized 60% of the isolates tested. B12 did not neutralize clade A isolates and 2F5 did not neutralize clade C isolates and one clade B isolate (PVO.4). 4E10 neutralized all the isolates in this panel.

Table 2.

Neutralization activity of m9 in TZM-bl cell line-based assay against HIV-1 primary isolates from clades A, B and C in comparison with scFv 17b, IgG1s b12, 2G12, 2F5 and 4E10

| Virus | Clade | Region | Pheno-type | IC50 (nM) in TZM-bl cells | |||||

| m9 | scFv 17b | b12 | 2G12 | 2F5 | 4E10 | ||||

| SF162.LS | B | US | R5 | 1 | 106 | 0.1 | 4 | 1 | 2 |

| QH0692.42 | B | Trinidad | R5 | 53 | >957 | 2 | 19 | 7 | 9 |

| SC422661.8 | B | Trinidad | R5 | 224 | >957 | 1 | 14 | 5 | 6 |

| PVO.4 | B | Italy | R5 | 59 | >957 | >335 | 8 | >335 | 44 |

| AC10.0.29 | B | US | R5 | 314 | >957 | 13 | >335 | 9 | 2 |

| Du123.6 | C | SA | R5 | 23 | >335 (785) | 1 | >335 | >335 | 1 |

| Du151.2 | C | SA | R5 | 320 | >957 | 9 | >335 | >335 | 5 |

| Du156.12 | C | SA | R5 | >335 (630) | >957 | 1 | >335 | >335 | 1 |

| Du172.17 | C | SA | R5 | 257 | >957 | 9 | >335 | >335 | 1 |

| Du422.1 | C | SA | R5 | 281 | >957 | 1 | >335 | >335 | 5 |

| Q23.17 | A | Kenya | R5 | 182 | >957 | >335 | >335 | 19 | 9 |

| Q168.a2 | A | Kenya | R5 | >335 (795) | >957 | >335 | >335 | 21 | 15 |

| Q461.e2 | A | Kenya | R5 | >335 (350) | >957 | >335 | >335 | 27 | 13 |

| Q769.d22 | A | Kenya | R5 | 92 | >957 | >335 | >335 | 3 | 3 |

| Q259.d2.17 | A | Kenya | R5 | >957 | >957 | >335 | >335 | 48 | 57 |

| Percentage neutralized (%) | 73 | 7 | 60 | 27 | 60 | 100 | |||

Neutralization was measured as a reduction in luciferase gene expression after a single round of infection of TZM-bl cells with HIV-1 Env pseudotyped viruses. Samples were assayed at multiple concentrations in duplicate. The highest concentration tested was 50 µg/ml for each antibody IgG1 and 29 µg/ml for antibody scFv fragment. Titers were calculated as the inhibitor concentrations causing a 50% reduction (IC50) of relative light units. IC50s in µg/ml were converted to nM for comparison. Percentage neutralized is the percentage of isolates with IC50 below the maximum antibody concentration (335 nM) tested. For m9 and scFv 17b, if the IC50 is over 335 nM, but below the maximum concentration tested (957 nM), the actual IC50 is indicated in parentheses.

Using the same TZM-bl cell line-based assay, the efficacy of m9 was further compared with 2F5 and 4E10 against another panel of primary isolates from clades A, B, C, D, AE and AG (Table 3). M9 exhibited higher potency than 2F5 and 4E10 in neutralizing this panel of isolates. M9 neutralized 89% of the isolates tested, while 2F5 and 4E10 neutralized 37 and 53%, respectively.

Table 3.

Neutralization activity of m9 in TZM-bl cell line-based assay against HIV-1 primary isolates from different clades in comparison with IgG1s 2F5 and 4E10

| Virus | Clade | Region | Tropism | IC50 (nM) | ||

| m9 | 2F5 | 4E10 | ||||

| 92UG_029 | A | Uganda | X4 | 13 | >201 | >201 |

| 00Ke_KeR2008 | A | Kenya | Dual | 36 | >201 | >201 |

| 89BZ_167 | B | Brazil | X4 | >990 | 0.2 | 1 |

| 92FR_BXO8 | B | France | R5 | 3 | 5 | 5 |

| 90US_873 | B | United States | R5 | 30 | 16 | 18 |

| 96tH_Np1538 | B | Thailand | R5 | 69 | 52 | >201 |

| 91US_4 | B | United States | R5 | 56 | >201 | >201 |

| 89SM_145 | C | Somalia | R5 | 83 | >201 | 40 |

| 01tZ_911 | C | Tanzania | R5 | 96 | >201 | >201 |

| 98US_MSC5016 | C | United States | R5 | 191 | >201 | 3 |

| 94IN_20635-4 | C | India | R5 | 7 | >201 | >201 |

| 93UG_065 | D | Uganda | X4 | 23 | >201 | >201 |

| 99UG_Ao8483M1 | D | Uganda | R5 | 175 | 50 | 221 |

| 98UG_57128 | D | Uganda | R5 | 168 | >201 | 74 |

| 00Ke_NKU3006 | D | Kenya | R5 | 76 | 17 | 18 |

| 90tH_CM240 | AE | Thailand | R5 | 26 | >201 | >201 |

| 02CM_1970LE | AG | Cameroon | R5 | >990 | >201 | >201 |

| 98US_MSC5007 | AG | United States | R5 | 50 | 43 | 18 |

| 02CM_0013BBY | AG | Cameroon | R5 | 122 | >201 | 13 |

| Percentage neutralized (%) | 89 | 37 | 53 | |||

The highest concentration tested was 30 µg/ml (equal to 990 nM of m9, and 201 nM of 2F5 or 4E10). Percentage neutralized is the percentage of isolates with IC50 below the maximum antibody concentration (201 nM) tested.

We previously reported increased efficacy of HIV-1 neutralization by some CD4i and gp41-specific antibodies at low CCR5 surface concentration.21 Here we tested m9 with a panel of clade C isolates in an M7-Luc cell line-based assay (Table 4). M7-Luc cells have much lower CCR5 surface density than TZM-bl cells. Five clade C isolates tested in the TZM-bl cell line-based assay, Du123.6, Du151.2, Du156.12, Du172.17 and Du422.1, were also included in this M7-Luc cell line-based assay for comparison. IgG1 b12 was previously tested against this panel of clade C isolates by measuring IC80 value, therefore the same assay conditions and inhibitory concentration (IC80) were used when testing m9 against this panel of clade C isolates. Both assays were carried out in the same laboratory. The results showed that m9 neutralized 76% (13 out of 17) of the clade C isolates with an average IC80 value significantly lower than that of IgG1 b12.22 B12 neutralized 56% (9 out of 17) of the isolates tested. For the same five clade C isolates, m9 showed an overall higher potency in M7-Luc assay (Table 4) than in TZM-bl assay (Table 2). This result is consistent with our previous finding that the coreceptor density on the target cell surface reversely affects the potency of CD4i antibodies, while it has little effect on the potency of CD4bs antibodies, e.g., b12.21

Table 4.

Neutralization activity of m9 in M7-Luc cell line-based assay against a panel of primary isolates from clade C

| HIV-1 isolate | IC80 (nM) in M7-Luc cells | |

| m9 | IgG1 b12* | |

| Du123.6 | 46 | 107 |

| Du151.2 | 271 | 335 |

| Du156.12 | 10 | >335 |

| Du172.17 | 17 | 194 |

| Du422.1 | 40 | 154 |

| Du174 | 20 | >335 |

| Du179 | 195 | >335 |

| Du368 | 838 | 201 |

| TV1 | 7 | nt |

| S080 | 23 | 221 |

| S021 | >1,815 | >335 |

| S009 | 3 | 335 |

| S018 | 739 | 13 |

| S007 | 69 | >335 |

| S180 | 59 | >335 |

| S017 | >1,815 | >335 |

| S103 | 152 | <13.4 |

| Percentage neutralized (%) | 76 | 56 |

Neutralization was measured as a reduction in luciferase gene expression after multiple rounds of infection of M7-Luc cells with HIV-1 Env pseudotyped viruses. Titers were calculated as the inhibitor concentrations causing a 80% reduction (IC80) of relative light units. Samples were assayed at multiple concentrations in duplicate. nt, not tested. *the neutralization activity of IgG1 b1222 against the same panel of clade C virus in the same assay as reference. Percentage neutralized is the percentage of isolates with IC50 below 335 nM.

M9 potently inhibited cell-to-cell transmission of HIV-1.

Cell-to-cell transmission is likely a major route for HIV-1 infection in vivo.23 Therefore, we tested the inhibitory activity of m9 in a CCR5-dependent cell-to-cell transmission assay using HIV-1 JR-CSF (Table 5). In this cell-to-cell transmission assay, m9 was significantly more potent (lower IC50 and IC90) than the anti-HIV drug enfuvirtide, indicating that m9 can effectively block CCR5-dependent cell-to-cell transmission of HIV-1. M9 also showed higher potency than 2F5 and 4E10 that were included in this assay for comparison. These results suggest that m9 could exhibit potent activity in vivo where HIV-1 is thought to infect new cells mostly through this route.

Table 5.

Antiviral efficacy of m9 in CCR5-dependent cell-to-cell transmission assay

| Compound | IC50 (nM) | IC90 (nM) |

| AMD3100a | >10,000 | >10,000 |

| TAK779b | 3.0 | 6,420 |

| enfuvirtide | 35 | >1,000 |

| m9 | 0.066 | 2.3 |

| 4E10 | 1.4 | 9.1 |

| 2F5 | 1.5 | 6.4 |

The assay was performed as described in materials and methods.

Plerixafor (MOZOBIL); CXCR4 inhibitor, negative control.

CCR5 inhibitor, positive control.

M9 competed with a sulfated CCR5 N-terminal peptide (R5Nt) for binding to gp120-CD4 complex.

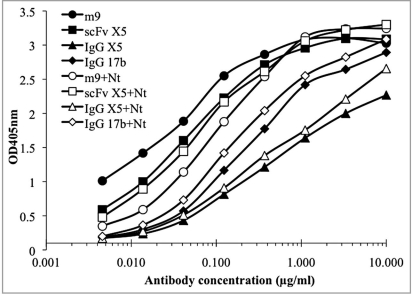

To explore the mechanism of the broad neutralization activity of m9, we did a competition ELISA of m9 with a sulfated R5Nt peptide which showed inhibitory activity by competing with cell-associated CCR5 on target cells.24 Like the parental antibody scFv X5, the binding of m9 to the Env was enhanced by sCD4.19 The Fab X5 epitope on the gp120 was revealed by the crystal structure in complex with a gp120 core and sCD4. It was also shown to overlap the coreceptor binding site on gp120. We hypothesized that m9 epitope is likely to be located close to the X5 epitope; however, antibody competition ELISA with R5Nt showed that only m9 competed with R5Nt for binding to gp120 complexed with sCD4 (Fig. 1). Neither scFv X5, nor IgG1 X5, nor IgG1 17b competed with R5Nt, indicating that the epitope of m9 is different from those of X5 and 17b. The competition of m9 with R5Nt may partially explain the improved neutralization potency and breadth of m9 compared to scFvs X5 and 17b. The potent neutralization activity of m9 suggests that its epitope may have potential use as a target for drug or vaccine development.

Figure 1.

Binding of m9, scFv X5, IgG1 X5 and IgG1 17b to gp120JRFL-CD4 complex in the presence and absence of CCR5 N-terminal peptide (Nt). one µg/ml of JRFLgp120 in complex with two-domain CD4 was directly coated on microplates. three-fold serially diluted biotinylated m9, scFv X5, IgG1 X5 and IgG1 17b were simultaneously added to the wells with (solid symbols) or without (empty symbols) 2 µg/ml (final concentration) of R5Nt. Bound biotinylated antibodies were revealed by horse radish peroxidase conjugates to streptavidin and ABtS substrate. Standard deviation was less than 5%.

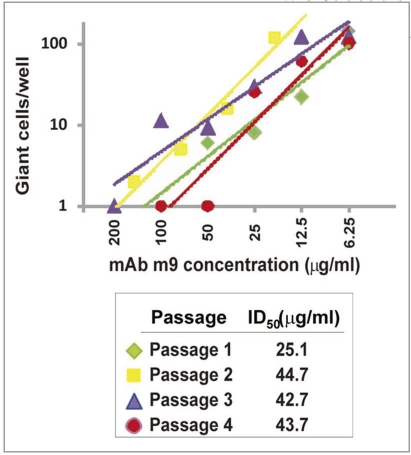

Generation of m9-resistant HIV-1 mutants is unlikely to occur.

M9 targets a highly conserved structure overlapping the functionally important coreceptor binding site, thus the emergence of m9-resistant viruses is of relatively low probability. We tested m9 for the possibility of generation of antibody-resistant HIV-1 mutants in tissue cultures. We performed serial passages of 89.6 in MT2 cells in the presence of serially diluted m9. Figure 2 shows the result from four serial passages in an immune selection assay. Even though the serially passaged virus was obtained each time from wells with concentrations well above the ID50 (about 12.5 µg/ml), the infectivity pattern was essentially the same on each occasion, indicating absence of very low concentrations of resistant virus during the time frame of this experiment. There was no observed trend for progressive increase in resistance on subsequent passages. The ID50s of the second, third, and fourth passages were close to two-fold higher than that of the first passage, but there was no difference in IC50 between repeated testing of unpassaged and first passaged virus (data not shown). The results indicate that the virus could replicate at low levels in the presence of inhibitory concentrations of m9, but such a process would be unlikely to result in selection of a virus resistant to neutralization by m9.

Figure 2.

Graphic representation of the results obtained from an immune selection assay. Giant cell numbers >60 were assigned values of 120 for graphing purposes, since the numbers in these cases were always uncountable and greater than 100. the lines shown are trend lines determined in excel. Squared regression coefficients were ≥0.9 in each case. Fifty percent inhibitory concentrations of m9 (IC50) were calculated by regression analyses as the concentrations at which 30 giant cells per well were observed.

M9 lacks reactivity with autoantigens.

The potent in vitro neutralization activity of m9 suggests that m9 may have potential for in vivo application as an HIV entry inhibitor for treatment of HIV-1 infection. To determine whether m9 may cause autoimmune response in clinical application and how specific the m9 epitope is, we tested the binding of m9 to phosphatidylserine (PS) and cardiolipin (CL) in an ELISA and a panel of autoantigens in an ANA assay (Table 6). M9 did not react with PS or CL, nor did it react with the panel of autoantigens in the ANA assay. Another CD4i antibody, IgG1 m16,17 was also tested in both assays and, similarly, did not show autoreactivity.

Table 6.

Lack of reactivity of m9 with autoantigens

| Antibodies | ELISA/SPR | AtheNA ANA Assay | |||||||||

| CL | PS | Ro | SSB (SSA) | Sm | RNP | Scl 70 | Jo1 | dsDNA | Centromere B | Histones | |

| Anti-gp120 | |||||||||||

| m9 (CD4i) | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| m16 (CD4i) | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Anti-gp41 | |||||||||||

| 4E10 | ++ | ++ | + | − | − | − | − | +/− | − | − | − |

| 2F5* | + | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | + |

The ANA assay was carried out using the AtheNA Multi-Lyte ANA system as described in Materials and Methods. The ELISA and SPR assays for antibody binding to PS and CL are previously described.46,47 M16, another CD4i antibody,25 was tested side-by-side with 4E10 and 2F5. SLE high cardiolipin serum was used as a positive control and gave positive scores for Ro, SSB, Sm, RNP, Scl 70, dsDNA and Histone. Reactivity of mAbs was scored based on the relative count: — for score <100 units, +/− for 120 > score > 100, and + for score >120. antigens are nuclear and cytoplasmic proteins: Ro, Rose antigen; SSA, Sjogren’s syndrome antigen; Sm, Smith antibodies; RNP, Ribonucleoprotein; Scl, scleroderma; Jo1, histidyl-transfer RNA synthase.

* ANA assay data for mAb 2F5 was previously published.46

Discussion

Here we report extensive characterization of m9 for potency and neutralization breadth in cell line-based assays. In this study, we used four different target cells (U87, HOS, TZM-bl and M7-Luc) in the cell line-based assays and the neutralization assays were conducted in several independent laboratories. The results of this study demonstrate that m9 can broadly and efficiently neutralize cell-free HIV-1 independent of virus tropism. In comparison with the best characterized HIV-1 neutralizing cross-reactive mAbs b12, 2F5, 4E10 and 2G12, m9 showed superior neutralization potency in cell line-based assays. M9 also exhibited higher potency than scFv 17b; ScFv 17b-CD4 fusion protein is under development as a microbicide.

We previously reported that the coreceptor concentration on the target cell surface affects the neutralization activity of some CD4i and gp41-specific mAbs.25 In this study, we observed the same phenomenon with m9. The same five clade C isolates (Du123, Du151, Du 156, Du172 and Du422) were included in both TZM-bl (Table 2) and M7-Luc (Table 4) cell line-based assays. M9 showed overall higher potency in the M7-Luc assay than in the TZM-bl assay, most likely due to the fact that M7-Luc cells have lower coreceptor density than TZM-bl cells.

M9 also potently inhibited cell-to-cell transmission of HIV-1 with potency greater than that of the entry inhibitor enfuvirtide. In this cell-to-cell transmission assay, we treated the effector cells with mitomycin C in order to induce cell death without impairing virus transmission. Mitomycin C was washed away before adding the effector cells to the target cells and visual inspection of the target cell monolayers was performed as part of the assay to confirm the integrity of the target cells. Virological synapses have been identified recently as a mechanism for virus transfer,26,27 but the effect of mitomycin C on the formation of virological synapses in this model system is still under study. In addition, the virological synapse is not necessarily the only mechanism of cell-to-cell transmission. Cell-associated virus is not necessarily internal to the cell and only transferred via the synapse. It can also be external to the cell, i.e., associated with the cell membrane and transferred by interaction of HIV Env between the two cells. Cell-to-cell transmission may be the dominant route for HIV transmission in vivo and in tissue cultures.23 The broad and potent neutralization activity of m9 suggests its potential as an anti-HIV-1 therapeutic or prophylactic agent.

Drug resistance is a major problem in HIV-1 prevention and therapy, and escape mutants could be a concern in clinical applications. We tested m9 in parallel with IgG1 b12 for the induction of antibody-resistant mutants of HIV-1 by in vitro passaging of the virus in the presence of the antibodies. Significantly, escape mutants resistant to IgG1 b12 soon emerged, but those resistant to m9 were not detected after three months of passaging.

In an attempt to explore the reason why m9 is more potent than the parental X5 and 17b, we did a competition ELISA with a sulfated CCR5 N-terminal peptide (R5Nt). The result showed that, unlike X5 and 17b, m9 competed with R5Nt for binding to gp120 complexed with sCD4, suggesting a shifted epitope of m9 on the coreceptor binding surface compared to X5 and 17b. The sulfated N-terminus and the second extracellular loop of CCR5 are critical for the binding of CCR5 to the HIV-1 Env.24 The competition of m9 with R5Nt may partially explain the improved neutralization potency and breadth of m9 compared to X5 and 17b. The potent and broad neutralization activity of m9 suggests that its epitope is conserved and may have potential use as a novel target for therapeutic agents.

To determine whether m9 may cause autoimmune disease in clinical application and the specificity of the epitope of m9, we tested its binding to PS and CL in an ELISA, and to a panel of autoantigens in an ANA assay. M9 did not react with PS or CL, or with the panel of autoantigens in the ANA assay (Table 6). Furthermore, in our cell cytotoxicity assay based on the production of ATP, m9 showed no cell cytotoxicity even at 6.6 µM (200 mg/L), the maximum concentration tested.

The potent in vitro neutralization activity, lack of reactivity with autoantigens and lack of cell cytotoxicity suggest that m9 may have potential as an HIV entry inhibitor for prevention and treatment of HIV-1 infection and AIDS. Alternatively, since m9 is a CD4i antibody fragment, an CD4-m9 fusion protein may show enhanced potency. M9 could possibly be used as an HIV-1-specific microbicide for prevention of sexually transmitted HIV-1. In this application, m9 or the m9-CD4 fusion protein could be used alone or in combination with HIV-1-specific or nonspecific microbicides, such as pH-modifying drugs,28 anionic polymers,29 non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs)28,30,31 and CCR5 inhibitors32–34 that are currently in clinical trials.32,34–40 In conclusion, our results suggest that m9 is a novel anti-HIV-1 candidate with potential as a therapeutic or prophylactic agent, and its epitope is a new target for drug or vaccine development.

Materials and Methods

Cells, viruses, plasmids, gp120 and antibodies.

293T cells were purchased from ATCC. Other cell lines and HIV-1 isolates were obtained from the NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program (ARRRP). The HIV-1 strain 89.6 was obtained through ARRRP (reagent number 1966) from Dr. Ronald Collman. Recombinant Envs from primary isolates were obtained as described previously.41 The human mAbs b12, 2F5, 4E10, 2G12, 17b and peptide enfuvirtide were obtained from the ARRRP. IgG1 X5, Fabs X5 and m16 were produced in our laboratory. Horse radish peroxidase-conjugated streptavidin was purchased (Zymed Laboratories Inc., San Francisco, CA). M9 protein was produced as previously described.19,42

HIV-1 cell line-based neutralization assay.

Four cell lines, U87, HOS (Table 1), TZM-bl (Tables 2 and 3) and M7-Luc (Table 4) were used in cell line-based assays. U87 and HOS cell line-based assays were previously described.43 The TZM-bl assay was carried out by using an HIV-1 Env pseudotyping system and TZM-bl target cells containing a tat-inducible luciferase reporter and expressing CD4, CCR5 and CXCR4. The degree of virus neutralization by antibody was achieved by measuring luciferase activity as described previously.44 Inhibitory concentrations were determined as the concentrations required to reduce relative luminescence units (RLU) by 50% (IC50), 80% (IC80) or 90% (IC90) compared to the luciferase activity in virus control wells (no test sample). M7-Luc cell line-based assay (Table 4) is very similar to TZM-bl cell line-based assay, but the target M7-Luc cells express CCR5 and contain a tat-responsive Luc reporter gene. M7-Luc cell line-based assay requires multiple rounds of replication.44

CCR5-dependent cell-to-cell transmission assay.

The CCR5-dependent cell-to-cell HIV-1 transmission inhibition assay (Table 5) was also previously described.45 The assay uses the CD4-positive GHOST X4/R5 cell line as target cells for transmission of virus from MOLT-4/CCR5 cells (effector cells) chronically infected with HIV-1 JR-CSF derived from the molecular clone pYK-JRCSF. Twenty-four hours prior to the assay, the target cells were seeded in 96-well flat bottom microtiter plates at 104 cells per well. On the day of assay, effector cells were treated with mitomycin C (200 µg/ml) (Sigma-Aldrich) for 60 min at 37°C in order to induce cell death without impairing virus transmission, and were then washed once with media. Test articles were added to the target cells followed by 1,000 effector cells. The effector and target cells were incubated with test articles for 4 h, followed by 3 washes with media. Twenty hours after assay initiation, the assay media was removed and the cells were lysed by adding 100 µL lysis buffer containing 20 mM Tris, pH7.5, 50 mM NaCl, 0.5% Triton-X-100 with one cycle of freeze-thaw prior to testing the lysate using an HIV-1 p24 ELISA following the manufacturer’s instructions (PerkinElmer).

Competition ELISA of m9, X5 and 17b with R5Nt (position 2–15: DYQVSSPIY*DINY*Y, Y10 and Y14 are sulfated).

Competition ELISA with R5Nt was performed by directly coating 1 µg/ml gp120JRFL and sCD4 complex (prepared by mixing 1:2 molar ratio recombinant gp120 with two-domain sCD4 followed by incubation at room temperature for 30 min) on 96-well plates, followed by addition of three-fold serially diluted biotinylated m9 and control antibodies in the presence and absence of 2 µg/ml R5Nt. Bound antibodies were detected using horse radish peroxidase conjugated to streptavidin and ABTS as substrate for color development.

Immune selection assay.

HIV-1 strain 89.6 virus pools were prepared by propagation in MT2 suspension cell culture in Dulbecco’s Minimal Essential Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and antibiotics. Medium was harvested when nearly all cells in the suspension appeared to be giant cells by light microscopy. Infectivity of virus pools was determined by titration in MT2 cells. Fifty microliters of five-fold serial dilutions of virus suspension in DMEM media were placed in 96-well microtiter plates, and 150 µl of MT2 cells in DMEM medium were added to each well, 1 × 104 cells per well. The number of cells was added that generally grew to achieve 75–100% confluence by 7 days in culture. Plates were incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 3–7 days, and the number of giant cells per well was enumerated daily using light microscopy beginning on day 3 or 4. The virus dilution that resulted in appearance of a few giant cells on day 3–4, and nearly complete giant cell formation on day 6 or 7 was used forimmune selection assays. Immune selection assay was performed as follows: two-fold serial diluted mAbs with a start concentration of 150 or 200 µg/ml were prepared in DMEM medium and dispensed in 25 µl aliquots to 96-well tissue culture plates. Equal volumes of virus suspension containing virus dilutions determined above were added to each well. The mAb-virus suspension was incubated at room temperature for 30 min and cell suspension added to a total volume of 200 µl. Plates were incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 6–7 days. The number of giant cells per well was enumerated daily using light microscopy beginning on day 3–4. Virus was subjected to the sequential passages in serial dilutions of m9. For each subsequent passage, the medium from the wells that showed any number of giant cells was tested for infectivity. Virus recovered from the wells with the highest concentration of m9 that yielded growth on titration was used without passage for subsequent selection.

Autoimmunity test.

The ANA assay was carried out using the AtheNA Multi-Lyte ANA system II. AtheNA Multi-Lyte polystyrene beads used in the assay were conjugated with the following autoantigens: Ro, Rose antigen; SSA, Sjogren’s syndrome antigen; Sm, Smith antibodies; RNP, Ribonucleoprotein; Scl, scleroderma; Jo1, histidyl-transfer RNA synthas, Centromere B and Histone. Samples were diluted in 6 two-fold steps starting at 300 µg/ml. 10 µl of each dilution was added to 50 µl of bead suspension and the manufacturer’s suggested protocol was followed for performing the assay. ELISA and SPR assay for antibody binding to phospholipids were carried out as described earlier.46

Acknowledgements

We thank Drs. Robert Blumenthal, Peter Kwong and Michael Fung for their helpful discussions. We also thank Monogram Biosciences for performing U87 cell line-based assays, Clay Osterling for performing the CCR5-dependent cell-to-cell transmission assays, and Ms. Jenny Ng for help with preparation of the manuscript. This research was supported by the internal funds from The University of Hong Kong, by the NIH Intramural AIDS Targeted Antiviral Program (IATAP), the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research, and the Gates Foundation to DSD, by Federal funds from the NIH, National Cancer Institute, under Contract No. NO1-CO-12400, and by internal funds from Southern Research Institute. The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does the mention of trade names, commercial products or organizations imply endorsement by the US Government.

Abbreviations

- ABTS

2,2′-azinobis(3-ethylbenzthiazolinesulfonic acid)

- DMEM

Dulbecco’s minimal essential medium escape

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/mabs/article/11416

References

- 1.Muster T, Steindl F, Purtscher M, Trkola A, Klima A, Himmler G, et al. A conserved neutralizing epitope on gp41 of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 1993;67:6642–6647. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.11.6642-6647.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zwick MB, Labrijn AF, Wang M, Spenlehauer C, Saphire EO, Binley JM, et al. Broadly neutralizing antibodies targeted to the membrane-proximal external region of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 glycoprotein gp41. J Virol. 2001;75:10892–10905. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.22.10892-10905.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stiegler G, Kunert R, Purtscher M, Wolbank S, Voglauer R, Steindl F, et al. A potent cross-clade neutralizing human monoclonal antibody against a novel epitope on gp41 of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2001;17:1757–1765. doi: 10.1089/08892220152741450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Binley JM, Wrin T, Korber B, Zwick MB, Wang M, Chappey C, et al. Comprehensive cross-clade neutralization analysis of a panel of anti-human immunodeficiency virus type 1 monoclonal antibodies. J Virol. 2004;78:13232–13252. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.23.13232-13252.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burton DR, Pyati J, Koduri R, Sharp SJ, Thornton GB, Parren PW, et al. Efficient neutralization of primary isolates of HIV-1 by a recombinant human monoclonal antibody. Science. 1994;266:1024–1027. doi: 10.1126/science.7973652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roben P, Moore JP, Thali M, Sodroski J, Barbas CF, 3rd, Burton DR. Recognition properties of a panel of human recombinant Fab fragments to the CD4 binding site of gp120 that show differing abilities to neutralize human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 1994;68:4821–4828. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.8.4821-4828.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhou T, Xu L, Dey B, Hessell AJ, Van Ryk D, Xiang SH, et al. Structural definition of a conserved neutralization epitope on HIV-1 gp120. Nature. 2007;445:732–737. doi: 10.1038/nature05580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Calarese DA, Lee HK, Huang CY, Best MD, Astronomo RD, Stanfield RL, et al. Dissection of the carbohydrate specificity of the broadly neutralizing anti-HIV-1 antibody 2G12. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:13372–13377. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505763102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Trkola A, Kuster H, Rusert P, Joos B, Fischer M, Leemann C, et al. Delay of HIV-1 rebound after cessation of antiretroviral therapy through passive transfer of human neutralizing antibodies. Nat Med. 2005;11:615–622. doi: 10.1038/nm1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Armbruster C, Stiegler GM, Vcelar BA, Jager W, Koller U, Jilch R, et al. Passive immunization with the anti-HIV-1 human monoclonal antibody (hMAb) 4E10 and the hMAb combination 4E10/2F5/2G12. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2004;54:915–920. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkh428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferrantelli F, Hofmann-Lehmann R, Rasmussen RA, Wang T, Xu W, Li PL, et al. Post-exposure prophylaxis with human monoclonal antibodies prevented SHIV89.6P infection or disease in neonatal macaques. Aids. 2003;17:301–309. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200302140-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ruprecht RM, Ferrantelli F, Kitabwalla M, Xu W, McClure HM. Antibody protection: passive immunization of neonates against oral AIDS virus challenge. Vaccine. 2003;21:3370–3373. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(03)00335-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Poignard P, Sabbe R, Picchio GR, Wang M, Gulizia RJ, Katinger H, et al. Neutralizing antibodies have limited effects on the control of established HIV-1 infection in vivo. Immunity. 1999;10:431–438. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80043-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Labrijn AF, Poignard P, Raja A, Zwick MB, Delgado K, Franti M, et al. Access of antibody molecules to the conserved coreceptor binding site on glycoprotein gp120 is sterically restricted on primary human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 2003;77:10557–10565. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.19.10557-10565.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Decker JM, Bibollet-Ruche F, Wei X, Wang S, Levy DN, Wang W, et al. Antigenic conservation and immunogenicity of the HIV coreceptor binding site. J Exp Med. 2005;201:1407–1419. doi: 10.1084/jem.20042510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moulard M, Phogat SK, Shu Y, Labrijn AF, Xiao X, Binley JM, et al. Broadly cross-reactive HIV-1-neutralizing human monoclonal Fab selected for binding to gp120-CD4-CCR5 complexes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:6913–6918. doi: 10.1073/pnas.102562599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang MY, Shu Y, Sidorov I, Dimitrov DS. Identification of a novel CD4i human monoclonal antibody Fab that neutralizes HIV-1 primary isolates from different clades. Antiviral Res. 2004;61:161–164. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2003.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang CC, Tang M, Zhang MY, Majeed S, Montabana E, Stanfield RL, et al. Structure of a V3-containing HIV-1 gp120 core. Science. 2005;310:1025–1028. doi: 10.1126/science.1118398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang MY, Shu Y, Rudolph D, Prabakaran P, Labrijn AF, Zwick MB, et al. Improved breadth and potency of an HIV-1-neutralizing human single-chain antibody by random mutagenesis and sequential antigen panning. J Mol Biol. 2004;335:209–219. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2003.09.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dey B, Del Castillo CS, Berger EA. Neutralization of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 by sCD4-17b, a single-chain chimeric protein, based on sequential interaction of gp120 with CD4 and coreceptor. J Virol. 2003;77:2859–2865. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.5.2859-2865.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Choudhry V, Zhang MY, Harris I, Sidorov IA, Vu B, Dimitrov AS, et al. Increased efficacy of HIV-1 neutralization by antibodies at low CCR5 surface concentration. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;348:1107–1115. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.07.163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bures R, Morris L, Williamson C, Ramjee G, Deers M, Fiscus SA, et al. Regional clustering of shared neutralization determinants on primary isolates of clade C human immunodeficiency virus type 1 from South Africa. J Virol. 2002;76:2233–2244. doi: 10.1128/jvi.76.5.2233-2244.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dimitrov DS, Willey RL, Sato H, Chang LJ, Blumenthal R, Martin MA. Quantitation of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection kinetics. J Virol. 1993;67:2182–2190. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.4.2182-2190.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Farzan M, Vasilieva N, Schnitzler CE, Chung S, Robinson J, Gerard NP, et al. A tyrosine-sulfated peptide based on the N terminus of CCR5 interacts with a CD4-enhanced epitope of the HIV-1 gp120 envelope glycoprotein and inhibits HIV-1 entry. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:33516–33521. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007228200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Choudhry V, Zhang MY, Sidorov IA, Louis JM, Harris I, Dimitrov AS, et al. Cross-reactive HIV-1 neutralizing monoclonal antibodies selected by screening of an immune human phage library against an envelope glycoprotein (gp140) isolated from a patient (R2) with broadly HIV-1 neutralizing antibodies. Virology. 2007;363:79–90. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2007.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Piguet V, Sattentau Q. Dangerous liaisons at the virological synapse. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:605–610. doi: 10.1172/JCI22812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hubner W, McNerney GP, Chen P, Dale BM, Gordon RE, Chuang FY, et al. Quantitative 3D video microscopy of HIV transfer across T cell virological synapses. Science. 2009;323:1743–1747. doi: 10.1126/science.1167525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hughes LM, Griffith R, Aitken RJ. The search for a topical dual action spermicide/microbicide. Curr Med Chem. 2007;14:775–786. doi: 10.2174/092986707780090972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cummins JE Jr, Denniston M, Mayer KH, Pickard R, Novak RM, Graham P, et al. Mucosal innate immune factors in secretions from high-risk individuals immunized with a bivalent gp120 vaccine. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2007;23:748–754. doi: 10.1089/aid.2006.0233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.D’Cruz OJ, Uckun FM. Novel broad-spectrum thiourea non-nucleoside inhibitors for the prevention of mucosal HIV transmission. Curr HIV Res. 2006;4:329–345. doi: 10.2174/157016206777709519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.D’Cruz OJ, Uckun FM. Dawn of non-nucleoside inhibitor-based anti-HIV microbicides. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2006;57:411–423. doi: 10.1093/jac/dki464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lederman MM, Veazey RS, Offord R, Mosier DE, Dufour J, Mefford M, et al. Prevention of vaginal SHIV transmission in rhesus macaques through inhibition of CCR5. Science. 2004;306:485–487. doi: 10.1126/science.1099288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Garzino-Demo A. Chemokines and defensins as HIV suppressive factors: an evolving story. Curr Pharm Des. 2007;13:163–172. doi: 10.2174/138161207779313696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nikolic DS, Garcia E, Piguet V. Microbicides and other topical agents in the prevention of HIV and sexually transmitted infections. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2007;5:77–88. doi: 10.1586/14787210.5.1.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ketas TJ, Klasse PJ, Spenlehauer C, Nesin M, Frank I, Pope M, et al. Entry inhibitors SCH-C, RANTES and T-20 block HIV type 1 replication in multiple cell types. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2003;19:177–186. doi: 10.1089/088922203763315678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kawamura T, Bruse SE, Abraha A, Sugaya M, Hartley O, Offord RE, et al. PSC-RANTES blocks R5 human immunodeficiency virus infection of Langerhans cells isolated from individuals with a variety of CCR5 diplotypes. J Virol. 2004;78:7602–7609. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.14.7602-7609.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Suresh P, Wanchu A. Chemokines and chemokine receptors in HIV infection: role in pathogenesis and therapeutics. J Postgrad Med. 2006;52:210–217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reeves JD, Piefer AJ. Emerging drug targets for antiretroviral therapy. Drugs. 2005;65:1747–1766. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200565130-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McGowan I. Microbicides: a new frontier in HIV prevention. Biologicals. 2006;34:241–255. doi: 10.1016/j.biologicals.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Keller MJ, Herold BC. Impact of microbicides and sexually transmitted infections on mucosal immunity in the female genital tract. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2006;56:356–363. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2006.00436.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang MY, Shu Y, Phogat S, Xiao X, Cham F, Bouma P, et al. Broadly cross-reactive HIV neutralizing human monoclonal antibody Fab selected by sequential antigen panning of a phage display library. J Immunol Methods. 2003;283:17–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2003.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Barbas CF, Burton DR, Scott JK, Silverman GJ. Phage Display: A Laboratory Mannual. Cold Spring Harbor: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang MY, Xiao X, Sidorov IA, Choudhry V, Cham F, Zhang PF, et al. Identification and characterization of a new cross-reactive human immunodeficiency virus type 1-neutralizing human monoclonal antibody. J Virol. 2004;78:9233–9242. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.17.9233-9242.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Montefiori DC. Evaluating neutralizing antibodies against HIV, SIV and SHIV in luciferase reporter gene assays. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lackman-Smith C, Osterling C, Luckenbaugh K, Mankowski M, Snyder B, Lewis G, et al. Development of a comprehensive human immunodeficiency virus type 1 screening algorithm for discovery and preclinical testing of topical microbicides. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52:1768–1781. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01328-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Haynes BF, Fleming J, St. Clair EW, Katinger H, Stiegler G, Kunert R, et al. Cardiolipin polyspecific autoreactivity in two broadly neutralizing HIV-1 antibodies. Science. 2005;308:1906–1908. doi: 10.1126/science.1111781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Alam SM, McAdams M, Boren D, Rak M, Scearce RM, Gao F, et al. The role of antibody polyspecificity and lipid reactivity in binding of broadly neutralizing anti-HIV-1 envelope human monoclonal antibodies 2F5 and 4E10 to glycoprotein 41 membrane proximal envelope epitopes. J Immunol. 2007;178:4424–4435. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.7.4424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]