Abstract

Background

Frontotemporal dementia and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis are neurodegenerative diseases associated with TAR DNA-binding protein 43– and ubiquitin-immunoreactive pathologic lesions.

Objective

To determine whether survival is influenced by symptom of onset in patients with frontotemporal dementia and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.

Design, Setting, and Patients

Retrospective review of patients with both cognitive impairment and motor neuron disease consecutively evaluated at 4 academic medical centers in 2 countries.

Main Outcome Measures

Clinical phenotypes and survival patterns of patients.

Results

A total of 87 patients were identified, including 60 who developed cognitive symptoms first, 19 who developed motor symptoms first, and 8 who had simultaneous onset of cognitive and motor symptoms. Among the 59 deceased patients, we identified 2 distinct subgroups of patients according to survival. Long-term survivors had cognitive onset and delayed emergence of motor symptoms after a long monosymptomatic phase and had significantly longer survival than the typical survivors (mean, 67.5 months vs 28.2 months, respectively; P<.001). Typical survivors can have simultaneous or discrete onset of cognitive and motor symptoms, and the simultaneous-onset patients had shorter survival (mean, 19.2 months) than those with distinct cognitive or motor onset (mean, 28.6 months) (P=.005).

Conclusions

Distinct patterns of survival profiles exist in patients with frontotemporal dementia and motor neuron disease, and overall survival may depend on the relative timing of the emergence of secondary symptoms.

FRONTOTEMPORAL DEMENTIA (FTD) and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) form a clinicopathologic continuum. Clinically, features of motor neuron disease (MND) such as ALS or primary lateral sclerosis (PLS) may develop in patients with a behavioral or language variant of FTD, and prominent behavioral and language deficits can emerge in the course of ALS.1-4 Pathologically, tau-negative and α-synuclein–negative cases of FTD have characteristic lesions immunoreactive to TAR DNA-binding protein of approximately 43 kDa (TDP-43), and TDP-43–immunoreactive (TDP-ir) inclusions are also the characteristic lesions in the spinal cord and motor cortex of patients with ALS.5-7 The overlapping clinical and pathologic features in frontotemporal lobar degeneration with ubiquitin/TDP-43–positive inclusions and ALS suggest that the 2 disorders represent a TDP-43 proteinopathy spectrum despite the differences in initial clinical presentation.8,9 Patients who develop FTD followed by symptoms of MND are commonly given the diagnosis of FTD-MND,10,11 and those who develop ALS before dementia are frequently diagnosed as having ALS with dementia (ALS-D).12

One feature common to FTD-MND and ALS-D is short survival: the development of MND in FTD or cognitive symptoms in ALS is significantly associated with poor prognosis. Patients diagnosed with FTD-MND have significantly shorter survival than patients with FTLD with ubiquitinpositive inclusions without MND,13 and cognitively impaired patients with ALS also have shorter survival than cognitively normal patients with ALS.14 It is unclear how survival in FTD-MND (cognitive onset) compares with survival in ALS-D (motor onset). Here we review the history of a large series of patients with both FTD and MND from 4 academic medical centers. We analyzed the survival of patients with initial symptoms of FTD or ALS and evaluated whether survival is influenced by initial symptom type, the relative timing of cognitive and motor symptom onset, the type of cognitive symptom (behavioral vs motor), and the site of MND onset (bulbar vs limb).

METHODS

DATA COLLECTION

Patient data were collected from the Cognitive/Dementia Clinics and ALS Clinics at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota; University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia; Erasmus University Medical Center, Rotterdam, the Netherlands; and Radboud University Nijmegen Medical Center, Nijmegen, the Netherlands. The clinical FTD phenotype was determined using consensus criteria for FTD,15,16 including both behavioral and language variants. Patients were given the diagnosis of dementia if their cognitive symptoms were sufficiently severe to impair their daily functioning, including interference with interpersonal relationships, job performance, instrumental activities of daily living, or activities of daily living, and if the evaluating clinicians considered the cognitive deficits to be sufficiently severe to cause prominent deficits despite the motor symptoms. Patients were diagnosed with MND if they had clinical and laboratory evidence of upper and/or lower motor neuron dysfunction consistent with the diagnosis of ALS according to revised El Escorial criteria17 or of PLS or upper motor neuron–dominant MND according to proposed criteria.18,19 Patients with PLS20 were included if there was no family history to suggest hereditary spastic paraparesis or if they transitioned to ALS based on clinical and electrophysiological criteria during the disease course. Only 2 patients (1 each from the Mayo Clinic and Erasmus University Medical Center) were diagnosed with PLS in the setting of cognitive-onset FTD-MND. Throughout the rest of the article, we refer to these patients and patients with ALS collectively as having ALS.

Forty patients from the Mayo Clinic were identified by searching the Mayo Clinic electronic medical record system from January 1, 1998, to December 31, 2007, for patients with FTD-MND, ALS-D, and ALS with cognitive impairment sufficiently severe for dementia who were evaluated at the Dementia Clinic or ALS Clinic. Twenty-three patients were recruited from the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center during prospective evaluation for dementia and MND from January 1, 1998, to July 31, 2008. Patients from the Erasmus University Medical Center and the Radboud University Nijmegen Medical Center were recruited and evaluated prospectively for cognitive impairment and MND from January 1, 1995, to July 31, 2008, and 31 patients were identified as having dementia and MND. Medical records were reviewed for historical information including sex, age at cognitive symptom onset, age at motor symptom onset, age at evaluation, age at last follow-up, age at death (if available), cognitive symptoms, location of initial motor symptoms (bulbar vs limb onset), and neurological examination findings. Patients were included only if they were evaluated by cognitive behavioral neurologists with experience in FTD and/or by MND specialists with expertise in ALS. Patients were excluded if there was insufficient historical information on the cognitive or motor symptom: in 5 patients from the Mayo Clinic and 2 patients from the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, cognitive symptoms were found incidentally during evaluation for MND or motor symptoms were found incidentally during evaluation for cognitive symptoms without timing or history of symptomatic progression. These patients were older when they eventually presented for evaluation (mean age, 74.3 years; P<.001) but were otherwise similar in sex, FTD phenotype, and site of MND onset. To analyze the relative timing of cognitive and motor symptom onset, a normalized timing of cognitive symptom onset relative to motor symptom onset was calculated by assigning a negative or positive value to the absolute period between onset of cognitive symptoms and onset of motor symptoms. This normalized timing was considered negative if cognitive symptoms preceded motor symptoms (cognitive onset) and positive if cognitive symptoms followed motor symptoms (motor onset). Patients were considered to have simultaneous onset if they had concurrent onset of cognitive and motor symptoms.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 12.0 statistical software (SPSS Inc, Chicago, Illinois). Descriptive statistics were used to characterize the entire cohort as well as each clinical subgroup. We used t test to analyze differences in continuous variables and χ2 test to investigate differences in dichotomous variables (including sex, bulbar vs limb onset, social or executive vs language subtype) between groups. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis was used to compare disease duration in patients with FTD and MND according to onset symptom types. K-means cluster analysis was used to group all patients with FTD and MND into clusters using sex, age at symptom onset, type of onset symptom, period between symptoms, duration of disease, FTD phenotype (social or executive disorder, language disorder, or both), and MND phenotype (bulbar onset or limb onset). The Davies-Bouldin validity index21 was used to determine the optimal number of clusters. Cox proportional hazards regression was used to analyze factors associated with survival.

RESULTS

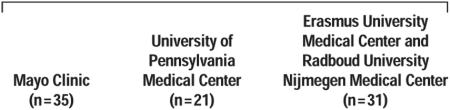

A total of 87 patients were identified as having symptoms of FTD and MND (Table 1). Patients were similar in sex, FTD phenotype, age at onset, age at death, and survival across the 4 sites. Fifty-nine patients (68%) had died, and 20 of the deceased patients (34%) had autopsies confirming TDP-43 pathologic lesions. Nineteen patients had pathologic findings of TDP-ir lesions affecting frontal neocortex, hippocampus, and hypoglossal nuclei and/or anterior horn cells, and 1 previously characterized patient with familial FTD-MND had TDP-ir lesions affecting the hippocampus, hypoglossal nuclei, and anterior horn cells but sparing the frontal neocortex.22

Table 1.

Basic Characteristics of Patients With Frontotemporal Dementia and Motor Neuron Disease

| Medical Center | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic |  |

Overall (N=87) |

||

| Female, No. (%) | 14 (40) | 10 (48) | 10 (32) | 34 (39) |

| Bulbar-onset MND, No. (%) | 18 (51) | 10 (48) | 18 (58) | 46 (53) |

| FTD subtype, No. (%) | ||||

| Social/executive dysfunction | 21 (60) | 14 (67) | 22 (71) | 57 (66) |

| Language | 6 (17) | 4 (19) | 4 (13) | 14 (16) |

| Both | 3 (9) | 2 (9) | 5 (16) | 10 (11) |

| Alzheimer disease–like | 5 (14) | 1 (4) | 0 | 6 (7) |

| EMG performed, No. (%) | 26 (74) | 21 (100) | 18 (58) | 65 (75) |

| Follow-up after second symptom, mean (median), mo | 7.5 (7) | 11.8 (10) | 19.0 (18) | 11.2 (10) |

| Died, No./Autopsy performed, No. | 16/6 | 15/3 | 28/11 | 59/20 |

| Cognitive symptom onset before motor symptom onset, No. | 26 | 11 | 23 | 60 |

| Age at onset, mean (median), y | 59.7 (60) | 56.8 (57) | 57.3 (55) | 58.3 (58) |

| Duration until motor symptom onset, mean (median), mo | 20.3 (18) | 32.3 (25) | 28.5 (18) | 25.7 (19) |

| Died, No. (%) | 15 (58) | 8 (73) | 20 (87) | 43 (72) |

| Overall disease duration, mean (median), mo | 34.6 (30) | 48.8 (47) | 51.7 (43) | 44.0 (34) |

| Disease duration after motor symptom onset, mean (median), mo | 14.3 (13) | 16.5 (14) | 23.9 (21) | 18.3 (14) |

| Simultaneous onset, No. | 3 | 2 | 3 | 8 |

| Age at onset, mean (median), y | 61.0 (68) | 63.0 (63) | 65.0 (73) | 63.0 (68) |

| Died, No. (%) | 1 (33) | 0 | 3 (100) | 4 (50) |

| Overall disease duration, mean (median), mo | 23.7 (24) | 21.0 (21) | 13.7 (14) | 19.3 (18)a |

| Motor symptom onset before cognitive symptom onset, No. | 6 | 8 | 5 | 19 |

| Age at onset, mean (median), y | 58.3 (58) | 57.4 (56) | 55.8 (51) | 57.3 (57) |

| Duration until cognitive symptom onset, mean (median), mo | 14.7 (9) | 11.0 (8) | 13.2 (5) | 12.7 (8) |

| Died, No. (%) | 0 | 7 (88) | 5 (100) | 12 (63) |

| Overall disease duration, mean (median), mo | 33.3 (27) | 31.9 (30) | 37.4 (39) | 34.3 (31) |

| Disease duration after cognitive symptom onset, mean (median), mo | 18.6 (18) | 21.9 (21) | 24.2 (30) | 21.4 (20) |

Abbreviations: EMG, electromyography; FTD, frontotemporal dementia; MND, motor neuron disease.

Significantly different from patients with cognitive onset (P<.001) and motor onset (P=.02).

In this combined cohort, we analyzed whether survival was associated with the relative timing of cognitive and motor symptom onset. We limited this analysis to the 58 deceased patients after excluding 1 outlier with cognitive onset followed by ALS symptoms. In this deceased cohort, normalized timing of cognitive symptom onset was inversely correlated with survival (r=0.694) (Figure 1): survival was longer as cognitive symptoms appeared earlier relative to motor symptoms. However, cases also appeared to form distinct clusters. K-means cluster analysis was used to identify cluster membership, and an optimal number of 2 clusters was determined by the Davies-Bouldin index. Cluster 1 contained 15 patients who all had FTD as their onset symptom (cognitive onset), and cluster 2 contained 43 patients including both patients with cognitive onset and patients with motor onset. Patients in cluster 1 had significantly longer survival (mean, 67.5 months) than patients with a more typical survival in cluster 2 (mean, 28.2 months) (P<.001). Long-term survivors had delayed emergence of secondary symptoms (mean, 43.0 months) relative to typical survivors (mean, 11.2 months) (P<.001). The long-term survivors in cluster 1 were significantly more likely to have limb-onset MND than typical survivors (12 of 15 patients [80%] vs 11 of 43 patients [26%], respectively; P<.001). Long-term survivors otherwise were similar to typical survivors in age at onset, sex, and FTD phenotype (Table 2). Only 1 long-term survivor had PLS 8 months before death. Five of the long-term survivors went on to autopsy, and all had TDP-ir pathologic lesions.

Figure 1.

Relationship between normalized time of cognitive symptom onset and overall disease survival among deceased patients. Normalized time of cognitive symptom onset was derived by subtracting the date of cognitive symptom onset from the date of motor symptom onset. A negative value indicates cognitive onset; a positive value, motor onset.

Table 2.

Characteristics of Patients According to Survival Patterns

| Typical Survivors | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic |  |

Long-term Survivors (n=25) |

P Valuea |

|

| Female, No. (%) | 5 (62) | 21 (39) | 8 (32) | .31 |

| Died, No. (%) | 4 (50) | 39 (72) | 16 (64) | .40 |

| Age at onset, mean (SD), y | 63.0 (12.9) | 58.7 (10.2) | 58.5 (10.3) | .28 |

| Cognitive onset, No. (%) | 0 | 37 (69) | 22 (88) | <.001 |

| Bulbar onset, No. (%) | 5 (63) | 34 (63) | 7 (28) | .01 |

| Language-dominant cognitive symptoms, No. (%) | 3 (38) | 16 (30) | 7 (28) | .88 |

| Overall disease duration, mean (SD), mo | 19.2 (6.4) | 28.6 (8.8) | 69.3 (21.1) | <.001 |

| Disease duration until secondary symptom onset, mean (SD), mo | 0 | 12.4 (7.9) | 44.5 (21.6) | <.001 |

| Disease duration after secondary symptom onset, mean (SD), mo | 19.2 (6.4) | 15.1 (7.4) | 24.0 (15.5) | <.01 |

We used χ2 test and 1-way analysis of variance to determine differences between dichotomous and continuous variables, respectively.

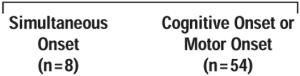

We extended the analysis to include patients still living at the last follow-up. Nine patients still living at the last follow-up had similarly long disease duration (mean, 77.1 months; range, 60-119 months) and represented additional long-term survivors. Long-term survivors were more likely to have cognitive onset than typical survivors (22 of 25 patients [88%] vs 37 of 62 patients [60%], respectively; P=.02). Among the 62 typical survivors, 17 patients (27%) had motor onset; 8 patients (13%) had simultaneous onset of cognitive and motor symptoms within the same month (χ2=10.8; P=.004). There was no difference in survival between patients who developed cognitive symptoms or motor symptoms first (Figure 2). However, patients with simultaneous onset had the shortest overall disease duration compared with patients with discrete cognitive or motor onset by Kaplan-Meier analysis (mean, 19.2 vs 28.6 months, respectively; P=.005).

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier survival analysis of patients with frontotemporal dementia and motor neuron disease according to survival grouping.

To further determine the effect of intersymptom duration on survival, we performed a multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression analysis using all patients. This analysis also included age at onset, sex, pattern of symptom onset (cognitive, motor, or simultaneous), and site of motor symptom onset. In the group as a whole, prognosis was better in those with longer intersymptom duration (hazard ratio [HR]=0.939/month; 95% confidence interval, 0.919-0.959; P<.001) and worse in those with bulbar-onset ALS (HR=1.751; 95% confidence interval, 1.006-3.050; P=.048). When typical and longterm survivors were analyzed separately, intersymptom duration continued to be a strong predictor of survival within each subgroup (typical survivors: HR = 0.925/month; P < .001; long-term survivors: HR = 0.951/month; P=.003). However, older age at onset (HR=0.913/year; 95% confidence interval, 0.843-0.988; P=.02) was associated with better prognosis only in the long-term survivors, and there was only a trend that bulbar-onset ALS was associated with worse outcome in the typical survivors (P=.11).

COMMENT

By combining data from 4 referral centers, we report the largest clinical series of patients who developed motor symptoms in the setting of FTD and dementia symptoms in the setting of ALS. In this large cohort, we were able to identify 2 unique subgroups of patients according to survival patterns. In addition to typical survivors, we discovered a group of patients with long-term survival characterized by mostly cognitive onset and delayed emergence of secondary symptoms with limbonset ALS.

In our large cohort, patients with FTD-MND or ALS-D have mean and median survival periods in keeping with previously reported values from smaller clinical11,14 and clinicopathologic13,23 series. We found that the relative timing of secondary symptom onset was a strong predictor of prognosis in our study among both typical and long-term survivors. The timing of secondary symptom onset may thus reflect in part the rate of stagewise disease progression regardless of cognitive or motor onset as progression rate is known to influence survival in ALS.24 Furthermore, survival in long-term survivors was inversely correlated with age at onset. It is not known whether age at onset is associated with prognosis in clinical FTD with TDP-ir pathologic lesions, but an older age at onset is associated with better survival in ALS without dementia.25 Thus, the similarities in prognostic factors between long-term survivors, typical survivors, and patients with typical ALS without dementia offer additional support that they form a clinicopathologic continuum.

The power of the large number of patients included in this study enabled us to identify the long-term survivors. One potential explanation for this distinct subgroup may be the differential anatomical involvement by pathologic lesions. In typical survivors, disease involving TDP-ir changes may be evident throughout prefrontal regions and the pyramidal system. The relative delay in onset between cognitive and motor systems is minimal, and the initial symptom at presentation is proportional to the volume of these regions within the frontal lobe. In contrast to the distributed model of TDP-ir pathologic lesions in typical survivors, long-term survivors may have focal onset of TDP-ir changes in prefrontal regions with subsequent involvement of the pyramidal system only following a long delay. Differences between these 2 groups were not detectable on autopsy as pathologic changes were insensitive to the relative timing of regional involvement, but future biomarkers of regionspecific involvement of TDP-ir pathologic lesions may provide some indication of biological differences between typical and long-term survivors. Other differences between these groups such as progranulin haplo-types may also account for the longer survival and should be ascertained in future prospective studies of FTD-MND and ALS-D.

This study has a number of limitations. First, our observations are retrospective in nature. More patients had cognitive onset than motor onset from centers with long-established interests in dementing illnesses, although patients were equally likely to be seen at Cognitive/Dementia or ALS Clinics. Ascertainment bias may account for the longer range of intersymptom durations in cognitive-onset patients as dementia may delay subjective motor complaints; the smaller number of motor-onset patients also may be due in part to the recent recognition of dementia in ALS. Survival data were incomplete in some cases as patients were lost in follow-up. Only a proportion of cases had autopsy confirmation. The combination of FTD and MND nearly always correlated with TDP-ir pathologic lesions, although rare exceptions with a tau-positive disorder have been reported.8,26 Lastly, referral bias may exist in that most patients were referred by primary neurologists or primary care providers. However, with the low prevalence of FTD-MND and ALS-D in general clinical practice, this represents the largest multicenter study to date on the clinical features of patients with cognitive and motor TDP-43 involvement. Patients with ALS who have clinical or subclinical cognitive impairment but not dementia are beyond the scope of the current study, although more careful cognitive assessments should be included in future studies so that the severity of cognitive impairment can be correlated with prognosis. With these caveats in mind, we propose 2 groups of patients with combined FTD and ALS: typical survivors and long-term survivors. Survival is influenced by the intersymptom duration between initial and secondary symptoms, the symptom of onset, and the site of ALS onset. Patients with cognitive onset and significantly delayed emergence of motor symptoms should be identified for their atypical prognosis, and patients with simultaneous onset of cognitive and motor symptoms also may have an atypical prognosis. Future studies will be necessary to assess biological factors associated with prolonged disease duration for potential therapeutic strategies.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: This work was supported by the American Academy of Neurology Clinical Research Training Fellowship, grant 06-0204 from Prinses Beatrix Fonds, grants AG17586, AG15116, and NS44266 from the US Public Health Service, Roadmap Multidisciplinary Clinical Research Career Development Award Grant (K12/NICHD)-HD49078 from the National Institutes of Health, and the Robert H. and Clarice Smith and Abigail Van Buren Alzheimer’s Disease Research Program of the Mayo Foundation.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure: Dr Knopman serves on a data safety monitoring board for Sanofi-Aventis and is an investigator in a clinical trial sponsored by Elan Pharmaceuticals. Dr Boeve is an investigator in a clinical trial sponsored by Myriad Pharmaceuticals. Dr Petersen has been a consultant to GE Healthcare and has served on a data safety monitoring board in a clinical trial sponsored by Elan Pharmaceuticals.

REFERENCES

- 1.Phukan J, Pender NP, Hardiman O. Cognitive impairment in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6(11):994–1003. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70265-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rippon GA, Scarmeas N, Gordon PH, et al. An observational study of cognitive impairment in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Arch Neurol. 2006;63(3):345–352. doi: 10.1001/archneur.63.3.345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ringholz GM, Appel SH, Bradshaw M, Cooke NA, Mosnik DM, Schulz PE. Prevalence and patterns of cognitive impairment in sporadic ALS. Neurology. 2005;65(4):586–590. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000172911.39167.b6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murphy JM, Henry RG, Langmore S, Kramer JH, Miller BL, Lomen-Hoerth C. Continuum of frontal lobe impairment in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Arch Neurol. 2007;64(4):530–534. doi: 10.1001/archneur.64.4.530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Neumann M, Sampathu DM, Kwong LK, et al. Ubiquitinated TDP-43 in frontotemporal lobar degeneration and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Science. 2006;314(5796):130–133. doi: 10.1126/science.1134108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dickson DW, Josephs KA, Amador-Ortiz C. TDP-43 in differential diagnosis of motor neuron disorders. Acta Neuropathol. 2007;114(1):71–79. doi: 10.1007/s00401-007-0234-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Josephs KA. Frontotemporal dementia and related disorders: deciphering the enigma. Ann Neurol. 2008;64(1):4–14. doi: 10.1002/ana.21426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mackenzie IR, Baborie A, Pickering-Brown S, et al. Heterogeneity of ubiquitin pathology in frontotemporal lobar degeneration: classification and relation to clinical phenotype. Acta Neuropathol. 2006;112(5):539–549. doi: 10.1007/s00401-006-0138-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Josephs KA, Parisi JE, Knopman DS, Boeve BF, Petersen RC, Dickson DW. Clinically undetected motor neuron disease in pathologically proven frontotemporal lobar degeneration with motor neuron disease. Arch Neurol. 2006;63(4):506–512. doi: 10.1001/archneur.63.4.506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Josephs KA, Petersen RC, Knopman DS, et al. Clinicopathologic analysis of frontotemporal and corticobasal degenerations and PSP. Neurology. 2006;66(1):41–48. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000191307.69661.c3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hodges JR, Davies R, Xuereb J, Kril J, Halliday G. Survival in frontotemporal dementia. Neurology. 2003;61(3):349–354. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000078928.20107.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Strong MJ, Grace GM, Freedman M, et al. [Accessed October 31, 2008];Frontotemporal syndromes in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: consensus criteria for diagnosis. doi: 10.1080/17482960802654364. http://www.ftdalsconference.ca/downloads/ftdals_consensus.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Josephs KA, Knopman DS, Whitwell JL, et al. Survival in two variants of taunegative frontotemporal lobar degeneration: FTLD-U vs FTLD-MND. Neurology. 2005;65(4):645–647. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000173178.67986.7f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Olney RK, Murphy J, Forshew D, et al. The effects of executive and behavioral dysfunction on the course of ALS. Neurology. 2005;65(11):1774–1777. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000188759.87240.8b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McKhann GM, Albert MS, Grossman M, Miller B, Dickson D, Trojanowski JQ. Work Group on Frontotemporal Dementia and Pick’s Disease. Clinical and pathological diagnosis of frontotemporal dementia: report of the Work Group on Frontotemporal Dementia and Pick’s Disease. Arch Neurol. 2001;58(11):1803–1809. doi: 10.1001/archneur.58.11.1803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Neary D, Snowden JS, Gustafson L, et al. Frontotemporal lobar degeneration: a consensus on clinical diagnostic criteria. Neurology. 1998;51(6):1546–1554. doi: 10.1212/wnl.51.6.1546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brooks BR, Miller RG, Swash M, Munsat TL. World Federation of Neurology Research Group on Motor Neuron Diseases. El Escorial revisited: revised criteria for the diagnosis of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Other Motor Neuron Disord. 2000;1(5):293–299. doi: 10.1080/146608200300079536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gordon PH, Cheng B, Katz IB, et al. The natural history of primary lateral sclerosis. Neurology. 2006;66(5):647–653. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000200962.94777.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pringle CE, Hudson AJ, Munoz DG, Kiernan JA, Brown WF, Ebers GC. Primary lateral sclerosis: clinical features, neuropathology and diagnostic criteria. Brain. 1992;115(pt 2):495–520. doi: 10.1093/brain/115.2.495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Josephs KA, Dickson DW. Frontotemporal lobar degeneration with upper motor neuron disease/primary lateral sclerosis. Neurology. 2007;69(18):1800–1801. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000277270.99272.7e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Davies D, Bouldin D. A cluster separation measure. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 1979;1(4):224–227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Seelaar H, Schelhaas HJ, Azmani A, et al. TDP-43 pathology in familial frontotemporal dementia and motor neuron disease without Progranulin mutations. Brain. 2007;130(pt 5):1375–1385. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Forman MS, Farmer J, Johnson JK, et al. Frontotemporal dementia: clinicopathological correlations. Ann Neurol. 2006;59(6):952–962. doi: 10.1002/ana.20873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chiò A, Mora G, Leone M, et al. Piemonte and Valle d’Aosta Register for ALS (PARALS). Early symptom progression rate is related to ALS outcome: a prospective population-based study. Neurology. 2002;59(1):99–103. doi: 10.1212/wnl.59.1.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sleegers K, Brouwers N, Maurer-Stroh S, et al. Progranulin genetic variability contributes to amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurology. 2008;71(4):253–259. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000289191.54852.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kovacs GG, Majtenyi K, Spina S, et al. White matter tauopathy with globular glial inclusions: a distinct sporadic frontotemporal lobar degeneration. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2008;67(10):963–975. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e318187a80f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]