Abstract

Motivation: The medical imaging and image processing techniques, ranging from microscopic to macroscopic, has become one of the main components of diagnostic procedures to assist dermatologists in their medical decision-making processes. Computer-aided segmentation and border detection on dermoscopic images is one of the core components of diagnostic procedures and therapeutic interventions for skin cancer. Automated assessment tools for dermoscopic images have become an important research field mainly because of inter- and intra-observer variations in human interpretations. In this study, a novel approach—graph spanner—for automatic border detection in dermoscopic images is proposed. In this approach, a proximity graph representation of dermoscopic images in order to detect regions and borders in skin lesion is presented.

Results: Graph spanner approach is examined on a set of 100 dermoscopic images whose manually drawn borders by a dermatologist are used as the ground truth. Error rates, false positives and false negatives along with true positives and true negatives are quantified by digitally comparing results with manually determined borders from a dermatologist. The results show that the highest precision and recall rates obtained to determine lesion boundaries are 100%. However, accuracy of assessment averages out at 97.72% and borders errors' mean is 2.28% for whole dataset.

Contact: skockara@uca.edu

1 INTRODUCTION

Melanoma is the fifth most common malignancy in the US. Invasive and in-situ melanoma has rapidly become one of the leading cancers in the world. Malignant melanoma, the most deadly form of skin cancer, is one of the most rapidly increasing cancers. 62 480 incidences and 8420 deaths are the estimated numbers in the USA in 2008 (Jemal et al., 2008). In malignant melanoma, early diagnosis is particularly important since melanoma can be cured with a simple excision operation. Dermoscopy, also known as dermatoscopy, is one of the major non-invasive skin imaging techniques that is extensively used in the diagnosis of melanoma and other skin lesions. This imaging technique offers more visible image subsurface structures when compared to conventional clinical images (Argenziano et al., 2002; Fleming et al., 1998). Dermoscopy also helps identifying various morphological features; for instance, blotches, streaks, blue-white areas, dots/ globules and pigment networks (Menzies et al., 2003). Because of these unique features, screening errors can be reduced at the inspection. In addition, greater differentiation between difficult lesions, such as pigmented Spitz nevi, clinically equivocal lesions can be provided (Steiner et al., 1993).

Dermoscopic assessment remains one of the most critical steps in the diagnosis and subsequent treatment of malignant melanoma. Recent improvements in imaging techniques have led to the automated discovery of lesions. Traditionally, assessment of tumor margins is done manually by a dermatologist. The recognition of cancerous regions is a time consuming and error prone process, and it is innate in the nature of the human inspection. Unfortunately, for inexperienced dermatologists, dermoscopy may actually lower the diagnostic accuracy (Binder et al., 1995). The use of a fast and reliable computerized system could markedly increase the number of examined images for the existence of cancer regions. Moreover, the computerized image analysis is able to minimize the effect of inter- and intra-observer variability. Inter-observer variability is defined in terms of the decisions assigned between different observers on the same subject. However, intra-observer variability is defined in terms of the decisions assigned within the observer; for instance, the same dermatologist judges differently on the same image at different times. Therefore, unlike inexperienced dermatologists, when it comes to trying to minimize the chance of diagnostic errors, it is important to develop computerized image analysis techniques. These techniques alleviate the difficulty and subjectivity of visual interpretations which are the major contributors to the diagnostic errors (Celebi et al., 2009).

In the investigation of melanoma, delineation of region-of-interest is the first and key step in the automated analysis of skin lesion images for many reasons. First and foremost, the border structure provides important information for accurate diagnosis. Asymmetry, border irregularity and abrupt border cutoff are of many clinical features calculated based on the border lesion. Furthermore, the extraction of other important clinical indicators such as atypical pigment networks, globules and blue–white areas critically depends on the border detection (Schaefer et al., 2009a, b).

At the first stage for analysis of dermoscopy images, automated border detection is usually being applied (Celebi et al., 2007a, b). There are many factors that make automated border detection complex, e.g. low contrast between the surrounding skin and the lesion, fuzzy and irregular lesion border, intrinsic artifacts such as cutaneous features (air bubbles, blood vessels, hairs and black frames) to name a few (Celebi et al., 2009). According to Celebi et al. (2009) automated border detection can be divided into four sections: pre-processing, segmentation, post-processing and evaluation. Pre-processing step involves color space transformation (Pratt, 2007), contrast enhancement (Delgado et al., 2008) and artifacts removal (Celebi, 2008; Geusebroek, 2003; Lee 1997; Perreault and Hébert, 2007; Schmid, 1999; Wighton 2008; Zhou 2008). Segmentation step involves partitioning of an image into disjoint regions (Sonka et al., 2007). Post-processing step is used to obtain the lesion border (Celebi, 2007a, b; Melli, 2006; Iyatomi, 2006). Evaluation step involves dermatologists' evaluations on the border detection results. In this study, a proximity graph representation approach to detect regions and borders in skin lesions for dermoscopic images is introduced. This approach is based on a soft kinetic data structure (SKDS): graph spanners.

2 A SKDS

Today the need for processing continuously moving points in a wide range of application areas such as geographic information systems, networking, traffic control, weather forecasting and nearest neighbor search is more pervasive than ever. The ideal solution for maintaining and processing continuously moving points has not been thoroughly presented yet. However, there are two recent approaches for processing moving points; they are dynamic data structures (DDS) and kinetic data structures (KDS). DDS assume that the data points change their positions only at explicitly known time steps; thus, they are not adequate solution for maintaining and processing continuously moving points. The alternative approach to DDS is given in the context of computational geometry with KDS which are recently introduced by Basch et al. (1999). In KDS, it is assumed that points' motions are unknown but not arbitrary since equations of motions are assumed to be algebraic functions of time (typically linear or polynomially bounded) (Guibas et al., 1998). In other words, it is assumed that there are no sudden position leaps that cannot be defined by an algebraic function of time. KDSs consist of hierarchies of points that keep hierarchy updated for moving points. Superior form of KDS for dynamic points under unpredictable motions is called SKDS (Czumaj and Sohler, 2001). SKDSs are approximate data structures that are used to answer proximity queries. In the light of abovementioned definition of SKDS, to our knowledge, deformable spanner (DS) (Gao et al., 2006) is the first SKDS that maintains its structure under formerly unknown motion models in 3D.

DS supports all the criteria of uniformity, controllability, locality, being discrete and proximity based that a good KDS would provide (Alexandron et al., 2007; Russel and Guibas, 2005). These criteria facilitate spanner's usage in different application areas. Locality of edges is affected by a small subset of the total point set. This means that changes in one part of the graph do not generally affect the spanner edges in the other parts. There is only one uniform combinatorial element in the spanner that is called edge. Spanner is controllable to allow us to produce controllers (e.g. expansion ratio) capable of capturing the shape of the object with various degrees of tightness or looseness. Spanners are discrete; thus, their description does not include any geometric coordinates. Proximities in the spanner determine the local interactions and in turn local interactions determine the behavior of the moving points.

We consider the dermoscopy image's pixel colors in the context of computational geometry with SKDS. Our hypothesis is that: important characteristics (e.g. color combinations) of a skin lesion image can be obtained in a proximity graph representation by examining colors and their color-space (e.g. RGB) closeness relationships. Thus, we represent images as graphs to obtain color patterns. In order to represent an image as a graph, we take a cue from Gao et al. (2006) and produce graph spanner approach for image segmentation. High-level patterns from properties of unique colors represented in an image are exposed by a hierarchical graph spanner. SKDS approach we use—hierarchical graph spanner—representation (in short: balls hierarchy, BH) is explained in Section 2.2. Even though BH is capable of handling dynamic changes in images (e.g. video stream) in our case of detecting lesion borders in dermoscopy images; image pixels are static data points in 2D.

There exists numerous innovative graph-based image segmentation approaches in the literature. Shi et al. (1998) treated segmentation as a graph partitioning problem, and proposed a novel unbiased measure for segregating subgroups of a graph, known as the normalized cut (NC) criterion. More recently, Felzenszwalb and Huttenlocher (2004) developed a segmentation technique by defining a predicate for the existence of boundaries between regions, utilizing graph-based representations of images. However, our graph spanner method approaches image segmentation problem as an approximate shortest path finding problem with a given expansion ratio.

2.1 Notations and preliminaries

A Bi-level hierarchical representation is called clusters of balls (B) or BH. A pair (χ, d) is called metric space where χ is a point set and d is a distance function. d: χ × χ → [0, ∞) satisfying the d(u, v) = 0 if and only if points u and v are equal, and symmetry and triangle inequality hold for distance function d(u, v)=d(v, u), d(u, v)+d(v, z)≥d(u, z), respectively, where u, v and z are nodes in the hierarchy. B is in the metric (χ, d) and is a sequence of levels B0, B1,…, Bh where  .

.  indicates upper bound, h represents number of hierarchical levels, R represents radius at the highest level and ξ is a constant and called expansion ratio. This value determines how much a cluster ball will expand from one level to the upper level. For instance, v at level i+1 is a parent of u at level i is represented as Pi+1(ui)=v or P(ui)=vi+1, where u∈Bi, v∈Bi+1. Pj(ui)=v, j>i indicates that u at level i has v as a parent at level j where j≥i+1. Ci(vi+1)=u or C(vi+1)=ui indicates that u at level i is a child of v at level i + 1 or Ci(vj) = u, j>i, v's i-th level child is u. One node may have multiple children at the same level and has single parent. However, one node can be covered by multiple cluster balls from the upper levels. Neighbors of v where v ∈ Bi is represented as N(vi), N(vi) = {ui ∈ Bi, |uivi|≤ηrξi−1} where η is neighbor coefficient, r is minimum radius, and rξiis a radius at the level i. Ball v's neighbor at level i is represented as N(vi) = ui.

indicates upper bound, h represents number of hierarchical levels, R represents radius at the highest level and ξ is a constant and called expansion ratio. This value determines how much a cluster ball will expand from one level to the upper level. For instance, v at level i+1 is a parent of u at level i is represented as Pi+1(ui)=v or P(ui)=vi+1, where u∈Bi, v∈Bi+1. Pj(ui)=v, j>i indicates that u at level i has v as a parent at level j where j≥i+1. Ci(vi+1)=u or C(vi+1)=ui indicates that u at level i is a child of v at level i + 1 or Ci(vj) = u, j>i, v's i-th level child is u. One node may have multiple children at the same level and has single parent. However, one node can be covered by multiple cluster balls from the upper levels. Neighbors of v where v ∈ Bi is represented as N(vi), N(vi) = {ui ∈ Bi, |uivi|≤ηrξi−1} where η is neighbor coefficient, r is minimum radius, and rξiis a radius at the level i. Ball v's neighbor at level i is represented as N(vi) = ui.

2.2 BH

Hierarchical representation of graph spanners is approximating the metric space with a hierarchy of nodes based upon a sampling of the data subsets. The construction of these sets should be guaranteed with the following properties (Gao et al., 2006):

Bh—the highest level cluster ball—covers entire set of points (χ) in the graph G.

Vertex set V initially exists from points where each point is a center of a cluster ball. Vi represents vertices at level i where these vertices are cluster balls' centers at level i. V =

and Vi ⊆ Vi−1.

and Vi ⊆ Vi−1.No cluster ball at the same level covers other ball's center. Therefore, d|c(Bik)c(Bim)|>rξi, where i is level, c(Bik) ∈ V represents center of a ball k at level i. Bik ∈ Bi, rξi or ri is radius at the level, and k ≠ m.

There is a geometrically decreasing order among the clusters; Bh, Bh−1,…, B0, where B0 is the original point set itself and only contains a single vertex cluster. The cluster Bi-where I = 0, 1, 2,…, h-is a ball with radius ri at level i.

Ball clusters are hierarchical. Bi is refined representation of one lower level cluster Bi−1. There is no lower level cluster which is not contained or covered by an upper level cluster. That means hierarchical representation of clusters is laminar family of sets.

Each edge in hierarchy connects some neighbor clusters at the same level in Bi (neighbor edge).

Some children clusters of Bi in Bi−1 are connected by edges (child edge).

Each Bi−1 cluster is covered by cluster in Bi(Bi−1⊆Bi). Therefore, |Bi−1|≥|Bi| where |Bi−1| represents number of clusters at level i−1. Equality holds only in the situation that each and every cluster becomes parent cluster of itself.

Maximum number of distance scales (number of levels) is

where t is maximum distance between any two nodes.

where t is maximum distance between any two nodes.According to coverage property ∀u∈Bi−1 with i ≤ h, ∃v∈Bi. Every cluster ball's center is covered by one upper level's cluster ball's center. A cluster ball can be covered by another concentric ball (u = v) at one upper level.

According to the separation property, u, v ∈ Bi+1 where u ≠ v, dG(u, v)≥rξi, and r is minimum radius (radius at the first level where i = 0).

Cousin property implies that two close points that belong to different balls at Bi are children of the same ball at Bk where i < k ≤ h (h, number of levels in the hierarchy). This implies that cousins will have common ancestor.

There exists a parent chain from a point u at level i to its parent at j, where j>i. This chain can be followed by: Pj(…(Pi+3(Pi+2(Pi+1(ui))))…) = v, u = v when u expands up to the level j (parent of itself).

There is no unique hierarchy even for the same point set. Different insertion order of points would result in different but equally good hierarchy construction.

If Ci(vi+1) = u or C(vi+1) = ui and u ≠ v, then N(vi) = ui. If a ball ui is a child of another ball vi+1 at upper level, then ui must be neighbor of vi. This implies that a ball cannot become a child before becoming a neighbor. This is because no position leap is assumed.

Next section clarifies how these properties are satisfied and applied to construct BH.

2.3 Hierarchy construction

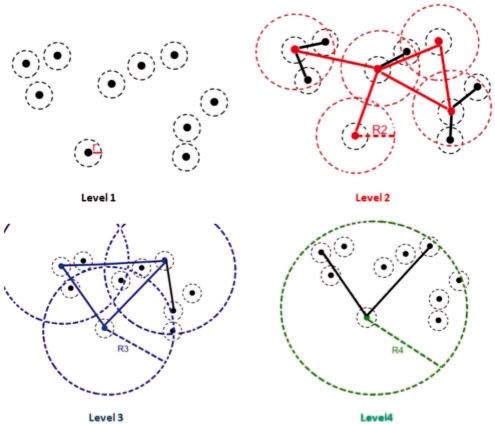

In this section, survivors, non-survivors and balls represent points. Ball is used in order to represent point with its radius-covering. Figure 1 illustrates BH construction steps for 10 points by using properties given in Section 2.2. In this illustration, hierarchy is consisting of four levels (property 9). Each level of the hierarchy is represented in different colors; black, red, blue and green colors, respectively. Dashed circles represent radius-covering at the level.

Fig. 1.

Hierarchy construction steps.

In the first level original data points exist with minimum radius r. Since minimum distance between closest color pairs (assuming in 3D RGB color space) in an image is 1, r is assigned as 1. As seen from the first level, since no other ball center is covered by any other ball, all survive (exist in the level). In the second level, only five points survive, since other points are covered by survivors with radius in the second level, R2. Non-survivor points become children of survivors. This relation is represented by child edges (see property 7 above) which are illustrated as steady black lines. R2 is expanded from minimum radius by expansion ratio (ξ); thus, R2 = rξ1. Superscript 1 represents level difference between level 2 and 1. Steady red lines in the second level represent neighbor edges (see property 6 above) which represent neighbor relations between any two survivor points (N(vi) = {ui ∈ Bi, |uivi| ≤ ηrξi−1}). Two survivors are neighbors if and only if distance between them is smaller than or equal to the neighbor coefficient (η) times radius at the level (R2). In the third level, there exist only three balls (blue) with radius R3=ξ2r, and a single non-survivor which becomes a child. Now, there are three neighbors (blue lines) in the third level. In level 4, there is only a single survivor (green) with two children. This survivor is called root and covers all existing points. Notice that in order a non-survivor point to become a child of a survivor point, it needs to be a neighbor of the survivor point in the previous level. Once hierarchy is constructed, BH keeps hierarchical representation of approximate shortest paths among all the existing points. Hierarchy construction time is O(n log n).

3 THE HIERARCHY REPRESENTATION FOR DERMOSCOPY IMAGES

Data points for an image are pixel's RGB colors. Once all pixels are inserted into the BH, color pixels are segmented as illustrated in Figure 2. Note that, due to the nature of RGB space similar colors are close to each other. After the construction, hierarchy is ready for a proximity query e.g. nearest neighbors. A proximity query will return any pixel with the specified color and its geometric neighbors in color space (RGB or any color space). Firing a query is corresponding to tree traversal.

Fig. 2.

A sample hierarchy representation of a dermoscopy image.

As seen from Figure 2, the suspected cancer regions, borders and the background are available right after the indexing process. In Figure 2 each branch of the tree is corresponding to one of the segments; the background (branch 1), right outside the border (branch 2), right inside the border including border (branch 3) and the lesion (inside the border, branch 4), respectively. Once hierarchy is constructed, the segments can be easily extracted by a simple hierarchy traversal. Depending on applications, segmentation also contributes to image regions or border identification. In dermoscopy images, some edges of the lesions are clearly defined while some have poorly defined edges such as the basal cell carcioma. Different significant parts of these images are successfully identified by performing three unique queries to recognize: (i) cancer region, (ii) cancer region border and (iii) the entire background. It is observed after the experiments that smallest number of children branch under the root node always indicates border. Since dermatologists focus on borders for diagnosis, we also return borders (branch 3 in Fig. 2) as a result of border query. Note that this hierarchy indexing method does not require any initial seed point which means that BH is a global approach.

Most often networks and points in nature are dynamic. Points are moving towards or against applied stimuli. Therefore, dynamic update operations such as insert and expand in the BH have profound impact on adapting hierarchy for motions. The following section will introduce insert and expand operations in the pseudo codes.

4 IMPLEMENTATION

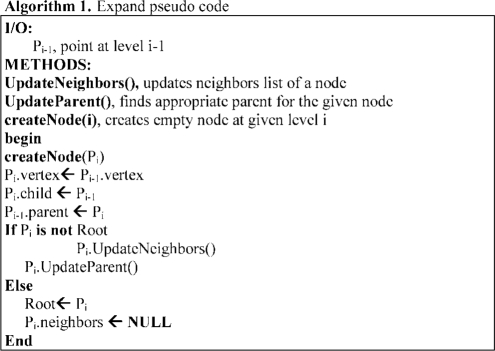

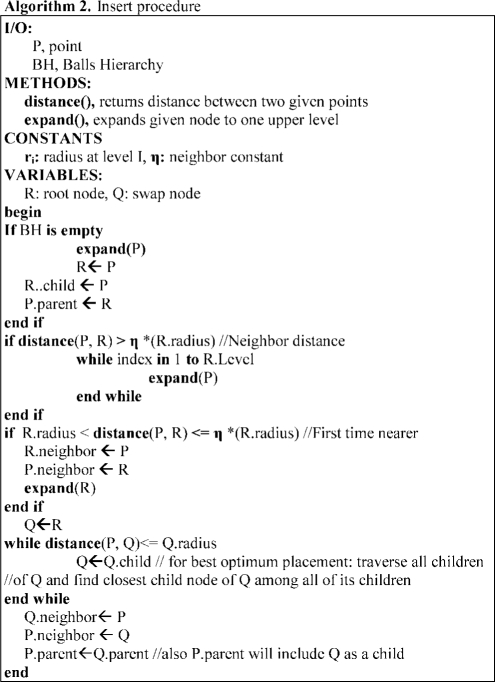

The most important operation in hierarchy construction is insert operation. To do that, first, expand operation is given as below.

A range of precision and computation time trade-offs have been implicated for using two different insertion schemes; optimum insertion and best optimum insertion respectively. Since precision is more important for us, we implemented best optimum insertion scheme as seen in Algorithm 2 below. This insertion scheme inserts new point into the best optimum place instead of the first optimum place found. In the best optimum insertion, the closest point among all other points is found by simply traversing the tree. To do that, in Algorithm 2 node Q's all children must be traversed. When the closest node is found among all the children, this closest node must be traversed recursively until no covering node (see property 3 in Section 2.2) is found. The last found node is called the best optimum place for insertion. Best optimum insertion scheme as a result succinctly provides higher precision and in turn leads to a better range query e.g. nearest neighbors.

5 RESULTS

BH method is tested on a set of 100 dermoscopy images obtained from the EDRA Interactive Atlas of Dermoscopy (Argenziano et al., 2002). These are 24-bit RGB color images with dimensions ranging from 577 × 397 to 1921 × 1285 pixels. The benign lesions include nevocellular nevi and dysplastic nevi.

Two unique queries are used to extract the desired region of the images. The first query is performed by looking for an entire branch of a directly related child node (DRCN) of the root node (RN). According to Figure 2, node 1, 33, 572 and 916 are DRCNs. Node zero is the RN. Each DRCN along with all their children nodes form one branch of the hierarchy. The hierarchy segments an image based on distance between colors and stores the pixel values in separated branches. Therefore, by querying each branch of the hierarchy, different color segment of an image can be obtained separately. For instance, the border of an indexed image can be archived by querying the entire branch of 33 in Figure 2. The second query is very similar to the first query except that the neighbors of children of all DRCN are included. This query yields an additional region of the image: the background. According to Figure 2, children of one are neighbors of 916's children.

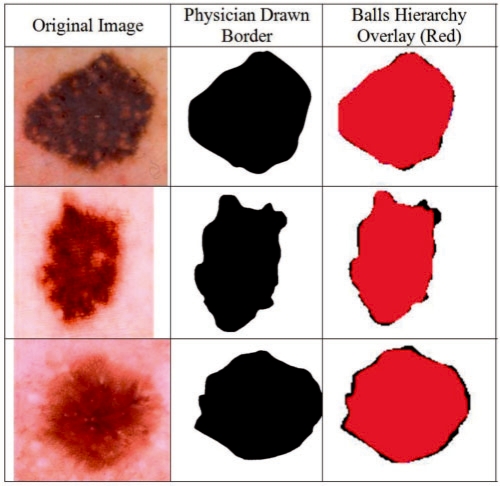

The BH based border detection errors are objectively quantified using dermatologist-determined borders as the ground truth. The BH detected border images overlaid on top of the dermatologist-determined border images. Quantative error metrics such as true/false positive/negative ratios found according to the overlay images. Figure 4 shows sample original images [which are selected among 100 images with the highest, lowest, and on average border error (BE) ratios]. The BH detected borders and interiors (e.g. combination of branches 3 and 4 of Fig. 2), overlaid images, and dermatologist-determined region are all illustrated, respectively, in Figure 4.

Fig. 4.

Overlay images.

Second, accuracy of our method is quantified by digitally comparing results with manually determined borders from a dermatologist. We evaluated border detection error of BH. Manual borders were obtained by selecting a number of points on the lesion border, connecting these points by a second-order B-spline and finally filling the resulting closed curve (Celebi, 2008). Using the dermatologist-determined borders, the automatic borders obtained from the BH are compared using three quantitative error metrics: BE, precision and recall. BE is developed by Gao et al. (1998) and Schaefer et al. (2009a, b), and given by

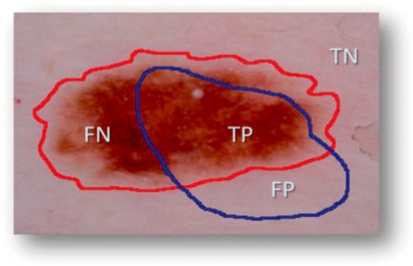

where ⊕ is exclusive OR operator, essentially underlines disagreement between target (ManualBorder, MB) and predicted (AutomaticBorder, AB) regions. Referring to information retrieval terminology, nominator of the BE means summation of false positive (FP) and false negative (FN). Denominator is obtained by adding true positive (TP) to false negatives (FN). An illustrative example is given in Figure 3. In the figure, assume that red and blue borders are drawn by a dermatologist and a non-expert, respectively. TP indicates correct lesion region found automatically. Similarly, TN shows healthy region (background) for both manual and computer assessment agreed on. FN and FP are labels for missed lesion and erroneous positive regions, respectively. Addition to BE, we also reported precision (positive predictive value) and recall (sensitivity) for each experimental image in Table 2. Note that all definitions run over number of pixels in the particular region.

Fig. 3.

Accuracy and error quantification.

Table 2.

Border errors, precision and recall of BH

| Img. ID | Border error (%) | Precision | Recall | Img. ID | Border error (%) | Precision | Recall |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.30 | 1 | 0.98 | 51 | 3.09 | 1 | 0.96 |

| 2 | 1.46 | 1 | 0.99 | 52 | 1.86 | 1 | 0.99 |

| 3 | 0.90 | 1 | 0.999 | 53 | 2.60 | 1 | 0.96 |

| 4 | 2.10 | 1 | 0.98 | 54 | 0.00 | 1 | 1 |

| 5 | 1.10 | 1 | 0.98 | 55 | 0.02 | 1 | 1 |

| 6 | 2.30 | 1 | 0.99 | 56 | 4.81 | 1 | 0.96 |

| 7 | 0.50 | 1 | 1 | 57 | 2.60 | 1 | 0.98 |

| 8 | 0.75 | 1 | 1 | 58 | 2.03 | 1 | 0.98 |

| 9 | 0.44 | 1 | 1 | 59 | 1.67 | 1 | 0.99 |

| 10 | 0.00 | 1 | 1 | 60 | 0.00 | 1 | 1 |

| 11 | 0.00 | 1 | 1 | 61 | 1.00 | 1 | 0.99 |

| 12 | 1.70 | 1 | 0.97 | 62 | 2.43 | 1 | 0.98 |

| 13 | 3.60 | 1 | 0.93 | 63 | 1.93 | 1 | 0.99 |

| 14 | 0.00 | 1 | 1 | 64 | 0.17 | 1 | 1 |

| 15 | 2.30 | 1 | 0.96 | 65 | 0.05 | 1 | 1 |

| 16 | 1.99 | 1 | 0.98 | 66 | 3.10 | 1 | 0.96 |

| 17 | 2.98 | 1 | 0.95 | 67 | 3.10 | 1 | 0.96 |

| 18 | 2.00 | 1 | 0.99 | 68 | 1.13 | 1 | 0.99 |

| 19 | 2.67 | 1 | 0.98 | 69 | 0.27 | 1 | 1 |

| 20 | 2.40 | 1 | 1 | 70 | 2.68 | 1 | 0.96 |

| 21 | 1.98 | 1 | 0.99 | 71 | 4.80 | 1 | 0.89 |

| 22 | 2.76 | 1 | 0.98 | 72 | 2.68 | 1 | 0.94 |

| 23 | 2.85 | 1 | 0.98 | 73 | 0.56 | 1 | 0.99 |

| 24 | 4.95 | 1 | 0.91 | 74 | 3.10 | 1 | 0.94 |

| 25 | 2.00 | 1 | 0.96 | 75 | 3.00 | 1 | 0.92 |

| 26 | 5.30 | 1 | 0.92 | 76 | 5.30 | 1 | 0.9 |

| 27 | 3.20 | 1 | 0.98 | 77 | 1.00 | 1 | 0.98 |

| 28 | 3.30 | 1 | 0.96 | 78 | 7.45 | 1 | 0.89 |

| 29 | 2.30 | 1 | 0.98 | 79 | 6.36 | 1 | 0.9 |

| 30 | 2.78 | 1 | 0.97 | 80 | 4.43 | 1 | 0.9 |

| 31 | 2.98 | 1 | 0.99 | 81 | 0.43 | 1 | 0.99 |

| 32 | 3.05 | 1 | 0.96 | 82 | 3.50 | 1 | 0.92 |

| 33 | 0.90 | 1 | 1 | 83 | 4.78 | 1 | 0.91 |

| 34 | 0.89 | 1 | 1 | 84 | 1.00 | 1 | 0.99 |

| 35 | 0.00 | 1 | 1 | 85 | 2.94 | 1 | 0.98 |

| 36 | 1.23 | 1 | 0.98 | 86 | 4.10 | 1 | 0.9 |

| 37 | 1.00 | 1 | 0.99 | 87 | 2.56 | 1 | 0.95 |

| 38 | 2.20 | 1 | 0.98 | 88 | 2.99 | 1 | 0.94 |

| 39 | 0.05 | 1 | 1 | 89 | 1.34 | 0.99 | 0.98 |

| 40 | 1.23 | 1 | 0.98 | 90 | 4.20 | 1 | 0.91 |

| 41 | 3.56 | 1 | 0.99 | 91 | 2.72 | 1 | 0.93 |

| 42 | 0.78 | 1 | 1 | 92 | 2.23 | 1 | 0.97 |

| 43 | 2.80 | 1 | 0.99 | 93 | 0.55 | 1 | 0.99 |

| 44 | 5.59 | 1 | 0.93 | 94 | 8.24 | 1 | 0.9 |

| 45 | 1.89 | 1 | 0.97 | 95 | 1.42 | 1 | 0.99 |

| 46 | 0.10 | 1 | 1 | 96 | 2.86 | 1 | 0.93 |

| 47 | 1.58 | 1 | 0.99 | 97 | 4.00 | 1 | 0.93 |

| 48 | 0.00 | 1 | 1 | 98 | 0.84 | 1 | 0.97 |

| 49 | 2.60 | 1 | 0.98 | 99 | 6.17 | 1 | 0.89 |

| 50 | 3.10 | 1 | 0.97 | 100 | 0.62 | 1 | 0.99 |

Figure 4 demonstrates how our method is compared quantitatively against dermatologist drawn image. In the figure left is original image, middle is dermatologist drawn image, and right (red area) is automatically found border image which is overlaid on top of the manually drawn image. In the experiments for 100 dermoscopy images dataset, the expansion ratio constant is determined by randomly chosen three sample images as shown in Table 1. As a result, the expansion ratio is chosen as 1.5 since this value was maximizing both precisions and recalls for three sample images as seen in Table 1. In Table 2 results for 100 images are displayed. For 100 images, BH's BE's mean is 2.28% (and σ = 3.01), precision's mean is ∼1.0 (and σ = 0.001) and recall's mean is 0.97 (σ = 0.003). The results show that accuracy of assessment averages out at 97.72%. A rough comparison of our findings with Schaefer et al. (2009a, b) and Celebi et al. (2008) showed that the mean errors of our method are obviously less than their results.

Table 1.

Benchmark results for different expansion ratios for three sample images

| Expansion ratio | 1.2 | 1.5 | 2.0 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Precision | Image 1 | 0.927 | 0.975 | 0.976 |

| Image 2 | 0.881 | 0.882 | 0.878 | |

| Image 3 | 0.977 | 0.939 | 0.930 | |

| Recall | Image 1 | 1 | 0.995 | 0.995 |

| Image 2 | 0.999 | 1 | 0.999 | |

| Image 3 | 1 | 1 | 0.999 | |

6 COMPARISON AND DISCUSSION

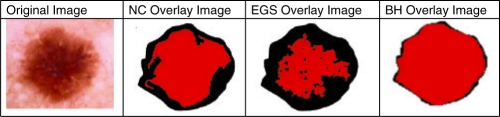

In this section, existing graph based image segmentation methods NCs method (Shi and Malik, 1997), the efficient graph based segmentation method (EGS) (Felzenszwalb and Huttenlocher, 2004), and the BH are compared with respect to efficiency on lesion border detection and computation complexities on dermoscopy images. C++ source codes for NC and EGS obtained from authors' websites. In Figure 5, results for a single lesion image generated from NC, EGS and BH overlaid, respectively, on the physician drawn ground truth image. As shown in Figure 5, much better results are obtained from BH.

Fig. 5.

Segmentation results from NC, EGS and BH from left to right.

In NC, minimization of the normalized cost function is NP hard. This method down-samples the original image then conducts initial segmentation in down-sampled image and finally initial segmentation is expanded to the original image. Its computation complexity is O(n3). Therefore, it only works on small sized images (e.g. 100 × 90). NC is a supervised method which requires expected number of clusters as a parameter. It is efficient on finding global segments; however, its efficiency reduces greatly if there are noises or tiny blemishes in the image. As seen in Figure 5, that degrades efficiency of the method for border detection in lesions since border regions have similar features with noise. Overall average precision of NC for 100 dermoscopy image dataset is 100%; however, average recall is 67% which makes NC inefficient for border detection in dermoscopy images.

However, EGS is able to preserve details in low-variability image regions (e.g. shadow regions) while ignoring details in high variability regions. Therefore, as seen from illustration in Figure 5, high variability regions in the interior of border (holes) are segmented as different regions. In this approach, results will be considerably affected by outliers since even two segments with low weight edge between them are combined as a single segment. Even though the computational complexity is O(n log n), in order to make the method more robust to outliers; definition of the difference between two regions needs to be changed. However, finding correct definition of difference is NP hard. The threshold function is the key element to determine the size of the segments. Variability on threshold changes results drastically. In this approach, when threshold is low, accuracy becomes high and computation speed reduces significantly. Overall average precision of EGS for 100 dermoscopy images is 100%; however, average recall is 55% which makes EGS also inefficient for border detection in dermoscopy images.

The BH is capable of accurately locating segments and has following features. First, it locates all local, non-local and global segments in a single hierarchical structure. Global segments are represented at higher levels in the hierarchy, non-local segments are represented in middle levels of the hierarchy, and local segments are represented in lower levels of the hierarchy. Second, it is a seedless and non-supervised method which does not require prior knowledge about expected number of clusters. Third, it is dynamic. Since it is a SKDS, it is capable of updating hierarchy according to dynamic changes. This dynamic nature may lead to analyzing dynamic behavior of changes in segments by time. Fourth, inherently hierarchical classes of special structures are hold in the hierarchy. There is inherent hierarchical structuring in nature. For instance, in a scene object parts exist in objects and lower-level features exist in object-parts in a hierarchical fashion. Although these spatial patterns (objects, object-parts, etc.) are quite different, they are manifested in different levels of the BH. Finally, unlike EGS and NC, BH has single parameter which is called expansion ratio. As seen from Table 1, change in expansion ratio does not affect results significantly unlike in EGS. The complexity of the BH is O(n log n); however, it runs in near linear time with respect to number of graph edges. In addition, the complexity of dynamic update operation is O(log n). Detail precision, recall, BE rates are listed for BH in Table 2.

7 CONCLUSION

In this study, a novel approach for automatic detection of skin lesions: BH is presented. The BH is a SKDS that keeps proximity graph representation in hierarchical form. It maintains geometric closeness relations among the point sets (colors). This data structure builds a hierarchical decomposition of a connected graph with certain properties (see Section 2.2 for properties).

Our approach is examined on a set of 100 dermoscopy images. Error rates: false positives and false negatives along with true positives and true negatives are quantified by digitally comparing results with manually determined borders from a dermatologist as the ground truth. The assessments obtained from our method are quantitatively analyzed with respect to BEs, precisions and recalls. Moreover, visual outcome showed that our method effectively delineated targeted lesions. Results proved that accuracy of automated assessments with the BH averages 97.72% which is higher than previously proposed methods. Also, BH is compared against well-known graph based segmentation methods on dermoscopy images and BH outperformed these methods. As a result, our approach finds both the lesions and the lesion borders with high precision rates.

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

REFERENCES

- Alexandron G, et al. Kinetic and dynamic data structures for convex hulls and upper envelopes. Comput. Geometr. Theory Appl. 2007;36:144–158. [Google Scholar]

- Argenziano G, et al. Dermoscopy: a Tutorial. Milan, Italy: EDRA Medical Publishing and New Media; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Basch J, et al. Data structures for mobile data. J. Algorithms. 1999;31:1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Binder M, et al. Epiluminescence microscopy. A useful tool for the diagnosis of pigmented skin lesions for formally trained dermatologists. Arch. Dermatol. 1995;31:286–291. doi: 10.1001/archderm.131.3.286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celebi ME, et al. Unsupervised border detection in dermoscopy images. Skin Res. Technol. 2007a;13:454–462. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0846.2007.00251.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celebi ME, et al. A methodological approach to the classification of dermoscopy images. Comput. Med. Imag. Graphics. 2007b;31:362–373. doi: 10.1016/j.compmedimag.2007.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celebi ME, et al. Border detection in dermoscopy images using statistical region merging. Skin Res. Technol. 2008;14:347–353. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0846.2008.00301.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celebi ME, et al. Lesion border detection in dermoscopy images. Comput. Med. Imag. Graphics. 2009;33:148–153. doi: 10.1016/j.compmedimag.2008.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czumaj A, Sohler C. Proceedings of the 12th Annual ACM-SIAM Symposium on Discrete Algorithms. Washington, DC, USA: 2001. Soft kinetic data structures; pp. 865–872. [Google Scholar]

- Delgado D, et al. Independent histogram pursuit for segmentation of skin lesions. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2008;55:157–161. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2007.910651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felzenszwalb PF, Huttenlocher DP. Efficient graph-based image segmentation. Int. J Comput. Vision. 2004;59:167–181. [Google Scholar]

- Fleming MG. Techniques for a structural analysis of dermatoscopic imagery. Comput, Med. Imag. Graphics. 1998;22:375–389. doi: 10.1016/s0895-6111(98)00048-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao J, et al. Segmentation of dermatoscopic images by stabilized inverse diffusion equations. Proc. IEEE Int. Conf. Image Process. 1998;3:823–827. [Google Scholar]

- Gao J, et al. Deformable spanners and applications. Comput. Geometry: Theory Appl. 2006;35:2–19. doi: 10.1016/j.comgeo.2005.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geusebroek J.-M, et al. Fast anisotropic gauss filtering. IEEE Trans Image Process. 2003;12:938–43. doi: 10.1109/TIP.2003.812429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guibas LJ. Kinetic data structures—a state of the art report. In: Agarwal PK, et al., editors. Proceedings of Workshop Algorithmic Foundation Robot. Wellesley, MA: A.K. Peters; 1998. pp. 191–209. [Google Scholar]

- Iyatomi H, et al. Quantitative assessment of tumor extraction from dermoscopy images and evaluation of computer-based extraction methods for automatic melanoma diagnostic system. Melanoma Res. 2006;16:183–190. doi: 10.1097/01.cmr.0000215041.76553.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jemal A, et al. CA: Cancer J. Clinicians. 2008;58:71–96. doi: 10.3322/CA.2007.0010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee TK, et al. A software approach to hair removal from images. Comp. Biol. Med. 1997;27:533–43. doi: 10.1016/s0010-4825(97)00020-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melli R, et al. Comparison of color clustering algorithms for segmentation of dermatological images. In: Cleary KR, Galloway R.L. Jr., editors. Progress in Biomedical Optics and Imaging. Vol. 7. San Diego, CA, USA: SPIE; 2006. pp. 3S1–3S9. Bellingham, Washington. [Google Scholar]

- Menzies SW, et al. An Atlas of Surface Microscopy of Pigmented Skin Lesions: Dermoscopy. Sydney, Australia: McGraw-Hill; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Perreault S, Hébert P. Median filtering in constant time. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2007;16:2389–94. doi: 10.1109/tip.2007.902329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratt WK. Digital Image Processing: PIKS Inside. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Russel D, Guibas LJ. Exploring protein folding trajectories using geometric spanners. Pacific Symp. Biocomp. 2005:42–53. doi: 10.1142/9789812702456_0005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi J, Malik J. Proceedings of IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. San Juan, Puerto Rico: 1997. Normalized cuts and image segmentation; pp. 731–737. [Google Scholar]

- Shi J, et al. Proceedings of 1998 International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP'98) Vol. 1. Chicago, IL: 1998. Image and video segmentation: the normalized cut framework; pp. 943–947. [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer G, et al. Proceedings of IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP 2009). Cairo, Egypt: 2009a. Skin lesion extraction in dermoscopic images based on colour enhancement and iterative segmentation; pp. 3361–3364. [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer G, et al. Proceedings of the Ninth International Conference on Information Technology and Applications in Biomedicine (ITAB 2009). Larnaca, Cyprus: 2009b. Skin lesion segmentation using cooperative neural network edge detection and colour normalisation. [Google Scholar]

- Schmid P. Segmentation of digitized dermatoscopic images bytwo-dimensional color clustering. IEEE Trans Med. Imaging. 1999;18:164–171. doi: 10.1109/42.759124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonka M, et al. Cengage-Engineering. 2 2007. Image processing, analysis, and machine vision. [Google Scholar]

- Steiner K, et al. Statistical evaluation of epiluminescence dermoscopy criteria for melanocytic pigmented lesions. J. Amer. Acad. Dermatol. 1993;29:581–588. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(93)70225-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wighton P, et al. Dermoscopic hair disocclusion using inpainting. In: Reinhardt JM, Pluim J.PW, editors. Proceedings of the SPIE Medical Imaging 2008 Conference. Vol. 6914. San Deigo, CA, USA: SPIE; 2008. pp. 691427–691427-8. Bellingham, Washington. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou H, et al. Feature-preserving artifact removal from dermoscopy images. In: Reinhardt JM, Pluim J.PW, editors. Proceedings of the SPIE Medical Imaging 2008 Conference. Vol. 6914. San Deigo, CA, USA: SPIE; 2008. pp. 69141B.1–69141B.9. Bellingham, Washington. [Google Scholar]