Abstract

Motivation: Ontologies and taxonomies have proven highly beneficial for biocuration. The Open Biomedical Ontology (OBO) Foundry alone lists over 90 ontologies mainly built with OBO-Edit. Creating and maintaining such ontologies is a labour-intensive, difficult, manual process. Automating parts of it is of great importance for the further development of ontologies and for biocuration.

Results: We have developed the Dresden Ontology Generator for Directed Acyclic Graphs (DOG4DAG), a system which supports the creation and extension of OBO ontologies by semi-automatically generating terms, definitions and parent–child relations from text in PubMed, the web and PDF repositories. DOG4DAG is seamlessly integrated into OBO-Edit. It generates terms by identifying statistically significant noun phrases in text. For definitions and parent–child relations it employs pattern-based web searches. We systematically evaluate each generation step using manually validated benchmarks. The term generation leads to high-quality terms also found in manually created ontologies. Up to 78% of definitions are valid and up to 54% of child–ancestor relations can be retrieved. There is no other validated system that achieves comparable results.

By combining the prediction of high-quality terms, definitions and parent–child relations with the ontology editor OBO-Edit we contribute a thoroughly validated tool for all OBO ontology engineers.

Availability: DOG4DAG is available within OBO-Edit 2.1 at http://www.oboedit.org

Contact: thomas.waechter@biotec.tu-dresden.de;

Supplementary Information: Supplementary data are available at Bioinformatics online.

1 INTRODUCTION

The advent of controlled vocabularies used for gene product annotation has had a deep impact on life science research (Bodenreider and Stevens, 2006; Howe et al., 2008), since it was a prerequisite for the analysis of high-throughput screens and the cross-referencing between databases of different model organisms and different types of data. Successful vocabularies in the life sciences range from formal ontologies defined in description logics such as SNOMED CT via directed acyclic graphs representing is-a and part-of relations such as the Gene Ontology (GO) (Ashburner et al., 2000) to hierarchical terminologies which define narrower and broader terms such as MeSH [www.nlm.nih.gov/mesh]. Over the past years, numerous ontologies have been created as evidenced by over 90 ontologies listed by the Open Biomedical Ontology (OBO) Foundry (Smith et al., 2007).

Creating ontologies is a labour-intensive, difficult, manual process, which is supported by dedicated ontology editors such as Protégé [protege.stanford.edu] and OBO-Edit (Day-Richter et al., 2007). Recently, there have been efforts to alleviate these difficulties through text-mining, which comprises a host of techniques from natural language processing to statistics. One such system is the Protégé plug-in TerMine (Frantzi et al., 2000), which suggests terms by analyzing the frequencies of word tuples in a text for a given query. Overall, text-mining has to address three problems to support ontology creation and extension: (i) generation of relevant ontology terms, (ii) their definitions and (iii) relationships between them. Tables 1–3 summarize the current state-of-the-art for these three problems. Table 1 shows that a number of systems have integrated linguistic and statistical filtering with machine learning achieving either high precision or recall. Table 2 shows the success rates of definition generation systems. In particular, the definitional question answering task (Voorhees, 2003) in the TREC 2003 information retrieval competition serves as a good evaluation benchmark. Existing systems achieved success rates of over 25%. The most difficult problem is taxonomy induction, since it requires the identification of entities and their relations in text. Table 3 shows recent results with success rates usually <50%. Besides evaluating ontology creation against benchmarks, one can assess how well semi-automated ontology creation and extension adheres to design guidelines as put forward among others by Schober et al. (2009).

Table 1.

Overview on term generation systems and their characteristics

| System | Characteristics |

Description | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Linguistic filtering | Statistical filtering | Machine learning | Context | ||

| NEURAL: Frantzi (1995) | ✓ | ✓ | Morphosyntactic patterns, list of suffixes, frequency, mutual information (Medicine), 70% recall | ||

| CLARIT: Evans Evans (1996) | ✓ | ✓ | NP parsers, statistical disambig., sub-compound generation, 240 Mb News corpus, 82% recall | ||

| TerMine: Frantzi et al. (2000) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | POS tagger; context defining words in the corpus, 75% precision within top 25% of terms | |

| OntoLearn: Navigli and Velardi (2004) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Comprehensive system including term, definition extraction and disambiguation; Tourism domain 0.80 precision 0.55 recall (estimated) |

| Text2Onto: Cimiano and Völker (2005) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Framework for ontology learning, algorithms for term and relation extraction |

| Lee et al. (2006) | ✓ | ✓ | Dependency parsing for relationship extraction for sub-units of GO concepts low precision 3.5% added (recall) | ||

| Wermter and Hahn (2006) | ✓ | ✓ | Comparison of statistics with filtering by frequency or linguistic information | ||

All methods use linguistic filtering, most methods statistical filtering, some methods use context information. The quality is given in terms of precision and recall (see ‘Methods’ section).

Table 3.

Overview on the quality of taxonomy induction

| Hearst (1992) | Precision > 90%, Recall << 10% |

| Caraballo (1999) | 33% Precision (strict), 60% Precision |

| Sanderson and Croft (1999) | 48% Precision (baseline 28%) |

| Cimiano et al. (2005) | F=0.33 (Finance), F=0.41 (Tourism) |

| Snow et al. (2004) | Maximal F-measure 14.2–35.9% |

| Snow et al. (2006) | 58% Precision, 20% Recall |

| Ryu and Choi (2006) | All Recall and Precision below 50% |

The F-measure is usually <50%. In information retrieval, quality is often measured as F-measure (F), the harmonic mean of precision and recall (see ‘Methods’ section).

Table 2.

Overview on the quality of definition extraction and definitional question answering

| Xu et al. (2003) | F=0.31, 1st rank in TREC2003 |

| Yang et al. (2003) | F=0.26, 2nd rank in TREC2003 |

| Echihabi et al. (2003) | F=0.27, 3rd rank in TREC2003 |

| Han et al. (2006) | F=0.16 |

| Degórski et al. (2008) | F=0.30 |

In the TREC2003 task on definitional question answering, the best system achieved a F-measure of F=0.31. In information retrieval, quality is often measured as F-measure (F), the harmonic mean of precision and recall (see ‘Methods’ section)

This article is organized as follows: first, we introduce DOG4DAG, the first tool for ontology generation within OBO-Edit. Second, we introduce the approach and system and then evaluate the quality of term, definition and relationship generation. Finally, we discuss how the system supports the design guidelines in Schober et al. (2009) and its limits.

2 THE OBO-EDIT PLUG-IN DOG4DAG

Before we describe the methods and results underlying our text-mining approach to ontology generation, we give an example demonstrating the functionality of the implemented system. DOG4DAG aims to support the work of ontology engineers, who create ontologies from scratch and extend existing ontologies, as well as biocurators, who annotate gene products with terms from the GO and other ontologies.

2.1 Example: ontology creation

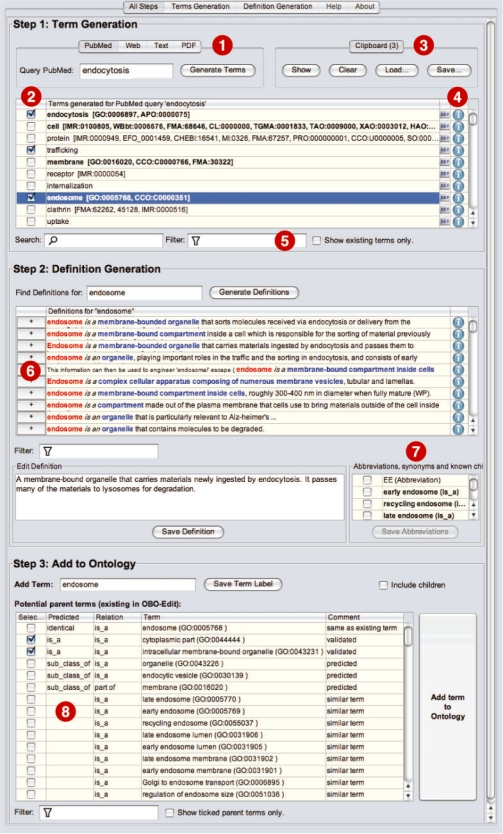

Figure 1 shows a screenshot of DOG4DAG with three panels for term generation (step 1), definition generation (step 2) and suggestion of parent terms (step 3). A user wishes to learn about endocytosis. DOG4DAG offers to either submit the query to PubMed or the Web or to upload text or PDF documents (Fig. 1 (1)). While PubMed is the default source for terminology, the web is often useful since full-text articles and other online resource such as clinical trials can be implicitly included in the search. PDFs are useful as a source if the user has e.g. a repository of full-text PDF articles covering the domain in question.

Fig. 1.

Screenshot of the OBO-Edit ontology generation tool showing the three steps ‘Term Generation’, ‘Definition Generation’ and ‘Add To Ontology’ for the example of adding and defining the term endosome.

Term generation: the user selects terms from the list of generated terms (Fig. 1 (2)), such as e.g. trafficking and endosome. The selected terms are added to the clipboard (Fig. 1 (3)). If the generated term exists already in other OBO ontologies then a corresponding reference is provided. Endocytosis is e.g. defined in GO and in the ascomycete phenotype ontology APO, whereas trafficking does not exist in any OBO ontology. Such references to OBO increase the confidence in the quality of the term and they allow the user to easily re-use terms and synonyms from other OBO-Ontologies. For each term, there are two icons (Fig. 1 (4)) to show the source of the term and move to the next step of definition generation. Searching and filtering terms (Fig. 1 (5)) allows the user to find specific terms. Filtering for example by ‘some’ to find terms similar to endosome brings up very relevant terms such as early endosome, recycling endosome, lysosome and liposome. If abbreviations for a term are found they are displayed (Fig. 1 (7)).

Definition generation: next, the user can define terms. Endosome is e.g. defined as ‘a membrane-bound organelle that sorts molecules received via endocytosis…’. The following definitions are also suitable and in fact all mention membrane, organelle or compartment. Clicking plus, the user can add definitions to a text field (Fig. 1 (6)) and revise them. Clicking the icon behind the definition reveals the source URL of the definition, which is kept and added as literature reference (dbxref) to the OBO file.

Taxonomy induction: in step 3, ‘Add to Ontology’, DOG4DAG predicts relations to ontology terms loaded in OBO-Edit (Fig. 1 (8)). For endosome known parents, cytoplasmic part and intracellular membrane-bound organelle are suggested and other parents are predicted from the definitions above, namely endocytic vesicle and organelle. Additionally, terms with strings similar to endosome are offered as parent candidates.

2.2 Example: biocuration

The above example demonstrates how the creation and extension of ontologies is supported. Additionally, DOG4DAG can be used directly for biocuration. By searching for a gene product relevant terms from known ontologies and novel terms are suggested. This not only helps biocurators directly in the annotation but also indirectly to identify other relevant ontologies and terms to be included in the ontology.

Let us consider the gene product Pax6. Pax6 is a ‘transcription factor playing a crucial role in the development of the eye’ according to DOG4DAG's definition generation. Querying with ‘Pax6’ brings up terms such as eye, development and aniridia. The first generated definition of the latter states that it is ‘a disease in which the iris fails to form normally’. The entry for aniridia also provides references to the disease ontology, GO biological processes and the human phenotype ontology (Robinson et al., 2008). With GO loaded in OBO-Edit, all generated terms similar to GO terms are shown in bold face. For Pax6 they are developmental process, transcription, neurogenesis or eye development. They correspond one-to-one to the UniProt [www.uniprot.org] annotations of human Pax6, which we use for validation.

3 METHODS

Next, we describe how the generation of terms, definitions and parent–child relations is realized.

Term generation: we extract terms from English text, which we tokenize before POS-tagging, sentence identification, noun phrase and local abbreviation detection. As POS tagger, we use Ling-Pipe-Tagger [alias-i.com/lingpipe] trained on MEDLINE and the TNT tagger (Brants, 2000) trained on the Wall Street Journal corpus. We generally regard phrases with pattern [adj|verb]*[fill]{2}[noun]+ as noun phrases, where fill are fill words like of, the, for, etc. We group noun phrases to candidate concepts and select a representative label from all associated abbreviations and lexical variants. Nested terms, i.e. noun phrases within longer noun phrases, are expanded as separate candidate concepts. We rank candidate concepts, under consideration of all lexical variants and abbreviations, according to their relative importance by the term frequency−inverse document frequency (tf-idf) measure, a weighting method commonly used in information retrieval. It captures the importance of a term in a set of documents in relation to a corpus. As corpus we used all scientific abstracts listed in PubMed.

Definition generation: the method aims to generate definitions that will follow the definitional pattern ‘A is a B with property C’, meaning that A is defined through the more general term B and can be distinguished from other Bs by its unique characteristic C. For example, ‘Endocytosis (A) is the process (B) by which cells absorb molecules (such as proteins) from outside the cell by engulfing it with their cell membrane (C′) (from Wikipedia). The term to be defined, denoted as A, is used to create queries to retrieve web search results via Yahoo's BOSS and Microsoft's Live Search API. We perform a search for A as well as A combined with hyponym patterns (Hearst, 1992) of high confidence (‘A is a’, ‘A is an’, ‘A are’, ‘As are’), or lower confidence (‘such as A’, ‘A is’, ‘such A like’, ‘or other A’, ‘and other A’, ‘A including’ and ‘especially A’). For some queries, we restrict the search to sites typically containing definitional statements like answers.com, wikipedia.org and reference.com. Typically, 20–40 web searches are performed in parallel to retrieve the definitions for one term.

Definitions are ranked higher according to six criteria regarding the term A to be defined and the differentia C: first, the definition contains A literally; second, the definition starts with A; third, A is the definition's subject; forth, C starts with an ontology term; fifth, C starts with a noun phrase; sixth, the relation A is a B is found literally. The text processing is the same as for the term generation.

Ontology referencing: with the help of the Ontology Lookup Service developed by the EBI (Cote et al., 2006) we map newly generated terms to OBO terms and within OBO-Edit to the loaded ontology. Terms are regarded as similar if they show a Hamming distance of <20% of the length of the shorter term label or synonym. Hamming distance denotes the number of position two strings differ. We align strings from the beginning and include the length of overlapping tails in the distance.

Taxonomy induction: given definitions of the form ‘A is a B with property C’ we extract existing terms similar to B (again Hamming distance) as candidate parents in a parent–child relationship. All ontology terms are ranked starting with the identical term, known parents from other ontologies, predicted parents from confirmed definitions, predicted parents from generated definitions and finally terms syntactically similar to the term to define. We created an index over all ontology terms to allow fast searching and filtering.

Evaluation of the term generation: we used the GO (as of 14 November 2009) and 13 sub trees of MeSH2010 (as of 29 October 2009). We randomly selected 1000 terms from MeSH for term generation and 500 from MeSH and 500 from GO for definition generation (see Supplementary Tables S5 and S6). During the evaluation, terms have been automatically mapped to existing ontologies. For OBO, we use the EBI Ontology Lookup Service, Dec 2009) and for the Unified Medical Language System (UMLS) version 2006AB. Mappings are listed in Supplementary Table S4. For term generation completeness is measured in terms of recall, the ration of retrieved relevant terms from all known relevant terms. Precision quantifies the portion from all generated terms which are indeed relevant. The F-measure is the harmonic mean between precision and recall and allows to compare quality with respect to one numeric value.

Evaluation of the definition generation: to evaluate definition generation, for 500 GO and 500 MeSH terms 10 definitions were generated and manually labelled as either correct if they match the GO/MeSH definition or valid if they were at least sensible and relevant. All generated definitions are listed in Supplementary Tables S8 and S9. A definition was judged as correct if it followed the original GO/MeSH definition with structure ‘A is a B with property C’ by at least agreement in B followed by a reasonable good C, or alternatively agreement in C, given a reasonable good B, typically a more general or specific term than the original B (see examples in Table 4). If generated definitions matched the GO/MeSH definition exactly they were excluded since the likely source was the original definition. This happened five times out of 10 000 definitions. Since GO terms rarely appear literally in text, see e.g. (Ogren et al., 2004), definitions for GO terms have been evaluated excluding common pre- and post-fixes. Example for ‘myosin binding’ we generated for ‘myosin’ the definition ‘Myosin is a protein possessing multiple functions integral to muscle contraction, force generation, muscle development, and production of high-quality processed meats.’, which we compared to the original GO definition. We excluded the pre- and post-fixes ‘activation’, ‘activity’, ‘binding’, ‘regulation of’’, ‘localization’, ‘development’, ‘transport’, ‘catabolic process’, ‘metabolic process’, and ‘biosynthetic process’. This applied to 307 of the 500 GO terms. The quality for definition extraction is measures in terms of precision, recall and F-measure.

Table 4.

Original and the best generated definition for four GO and four MeSH terms

| Original | Generated | |

|---|---|---|

| Gene ontology | ||

| Integrin biosynthetic process (GO:0045112) The chemical reactions and pathways resulting in the formation of integrins, a large family of transmembrane proteins that act as receptors for cell-adhesion molecules. | 4th: integrin is a heterodimer transmembrane protein that plays a critical role in cellular adhesion and migration during the inflammation and immune response. ( eng.umd.edu) | Correct |

| Anion channel activity (GO:0005253) Catalysis of the energy-independent passage of anions across a lipid bilayer down a concentration gradient. | 1st: Anion channel is an integral membrane protein or more typically an assembly of several proteins. (cogsci.uni-osnabrueck.de) | Valid |

| Benzoate metabolic process (GO:0018874) The chemical reactions and pathways involving benzoate, the anion of benzoic acid, a fungistatic compound widely used as a food preservative; […] | 1st: Benzoate is a common carbon source in nature that is funnelled directly to the widely distributed benzoyl-coenzyme A (benzoyl-CoA) central pathway. (mic.sgmjournals.com) | Valid |

| Cerebral cortex development (GO:0021987) The progression of the cerebral cortex over time from its initial formation until its mature state. The cerebral cortex is the outer layered region of the telencephalon. | 1st: cerebral cortex is a layer of nerve cells forming a convoluted outer shell over the brain, […] in which much of the thinking or higher intellectual activity of the brain takes place. (www.hermes-press.com) | Valid |

| Medical subject headings | ||

| Flucytosine (D005437) A fluorinated cytosine analog that is used as an antifungal agent. | 1st: Flucytosine is a fluorine analog of cytosine […], leading to inhibition of thymidylate synthetase and disruption of DNA synthesis. (emedicine.medscape.com) | Correct |

| Cystoscopy (D003558) Endoscopic examination, therapy or surgery of the urinary bladder. | 3rd: cystoscopy is an examination of the bladder […] using a flexible, miniature telescope […] (www.nuffielhealth.com) | Correct |

| Xanthomonas campestris (D016959) A species of gram-negative, aerobic bacteria that is pathogenic for plants. | 1st: Xanthomonas campestris is a Gram-negative plant-pathogenic bacterium […] (yemic.sgmjournals.org) | Correct |

| Trypanosoma brucei gambiense (D014347) A hemoflagellate subspecies of parasitic protozoa that causes Gambian or West African sleeping sickness in humans. The vector host is usually the tsetse fly (Glossina). | 1st: Trypanosoma brucei gambiense is a blood borne, flagellated protozoan which is transmitted to humans and animals via the tsetse fly (Glossina spp.). (etd.lib.ttu.edu) | Correct |

Definition are manually labelled as either correct if they match the GO/MeSH definition or valid if they contain useful information. For each generated definition the rank of retrieval (1st, 2nd, 3rd or 4th) is shown.

4 RESULTS

DOG4DAG is the first ontology generation systems that has been thoroughly validated in the life science domain. It is fully integrated into the established ontology editor OBO-Edit and supports the creation and extension of OBO ontologies by semi-automatically generating terms, definitions and parent–child relationships from text and web search results. As the quality of these suggestions made by automatic methods is of great importance for the overall usefulness and acceptance, we systematically evaluated it.

4.1 Evaluation of term generation

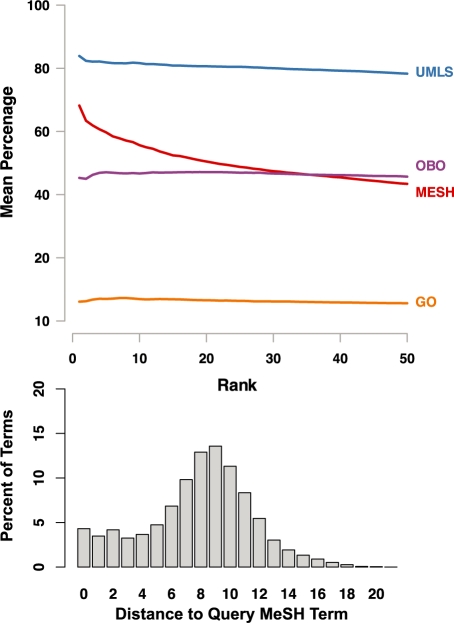

As the relevance of terms is often subjective, we evaluated the quality by checking how many generated terms are already part of existing manually designed ontologies. This reveals whether significant noun phrases according to our term generation have a similar structure to the manually defined terms. For 1000 randomly selected terms from MeSH (see Supplementary Table S3) we generated terms on the basis of text from 250 PubMed abstracts per MeSH term and mapped the generated terms to GO, MeSH, OBO, and UMLS. Figure 2 (top) shows the mean percentage of generated terms which exist as term in these ontologies. For all generated terms and mapping to the ontologies, see Supplementary Table S4. Relatively independent of the number of terms, over 80% of the generated terms are similar to UMLS terms. Over 40% of the generated terms exist in OBO or MeSH. Results for UMLS are best since it is the largest terminology with nearly 10 million terms which include GO, MeSH and OBO terms. This shows that our notion of statistically significant noun phrases is a good approximation to manually defined term labels. The numbers for GO are lower (13%) since the GO terms usually do not appear literally in text. We analyzed the distance of the query MeSH term to the generated term if it exists in MeSH. Figure 2 (bottom) shows that 15% of terms map out the direct neighbourhood, i.e. are synonyms, siblings, parent, children, etc., having a distance to the query term ≤3. Around 20% of terms are semantically distant and have a distance >10. Thus, the generated terms represent several possibly relevant aspects of the documents.

Fig. 2.

The mean percentage of generated terms from UMLS, MeSH, OBO and GO in the top-k ranked generated terms and their distance to the randomly selected query MeSH term used to retrieve 250 PubMed abstracts. The generated terms show both, a high proportion of terms similar to existing ontology terms, justifying the notion of noun phrases as term candidates, and a certain variance of distances of generated terms to the query MeSH term, thus mapping out the neighbourhood of the query MeSH term as well as addressing other aspects of the document set.

4.2 Evaluation of definition generation

Definition generation was evaluated 2-fold: first, on a benchmark set of 50 questions of the TREC2003 definitional question answering task and second, on manually created definitions of existing GO and MeSH terms.

Evaluation (TREC2003): We evaluated the definition extraction method based on questions and answers of the TREC2003 task on definitional question answering (Voorhees, 2003). Given a document corpus, this task required participants to find answers for the questions. In our validation the aim was to prove, that searching the web with our definitional patterns and ranking is suitable to retrieve definitions. For a definitional question like ‘Who is Charles Lindberg?’ or ‘What is a golden parachute?’ the definitions for the contained noun phrase ‘Charles Lindberg’ and ‘golden parachute’ have been generated. For 50 questions, the generated definitions have been manually compared with the answers given by the assessors board. For 20 questions out of 50 (40%) the top candidate definition was a correct definition. In 74% (37/50) of the cases a correct definition was found in the top 5 and in 90% (45/50) a correct definition could be found in the top 10 terms. For only five questions the method failed to find correct definitions. These results are in line with the top competition results with 0.21 precision of the best system (Liu et al., 2003; Table 2). See Supplementary Table S7 for all questions, generated definitions and manual curation.

Evaluation (MeSH and GO definitions): the comparison to TREC2003 is encouraging and allows to compare the method to the state-of-the-art, but does not cover the life sciences. For a specific evaluation against biomedical ontologies, we compared the generated to manually created definitions. On the whole, nearly all GO and MeSH terms have definitions with an average of 24 words (GO) and 30 words (MeSH) and contain 2.4 ontology terms (GO) and 5.7 (MeSH) (Table 5). To assess how well- generated definitions can approximate manually created definitions, we randomly selected 500 GO and 500 MeSH terms (listed in Supplementary Tables S5 and S6) and manually verified whether generated definitions matched the GO/MeSH definition or in another case gave useful information. For these 1000 terms, we generated 10 definitions each. All 10 000 generated definitions were manually verified whether they matched the GO/MeSH definition (correct) or were proper definitions of acceptable quality (valid).

Table 5.

Proportion of terms from in MeSH and GO containing parent terms, ancestor terms or other existing terms in their definitions

| All GO | All MeSH | |

|---|---|---|

| Total | 28 814 | 29 348 |

| Terms with definition | 99.1 | 96.0 |

| Words in definition | 24.3 (±15.3) | 30.2 (±19.3) |

| Terms in definition | 2.4 (±2.3) | 5.7 (±4.1) |

| ≥ 1 term in definition | 88.0 | 97.2 |

| ≥ 1 ancestor in definition | 54.1 | 56.2 |

| ≥ 1 parent in definition | 15.8 | 36.6 |

Nearly all of GO an MeSH terms are defined. 54.1–56.2% of terms are defined via an ancestor, 15.8–36.6% via a parent term.

A number of example definitions and whether they were considered as correct or only valid are provided in Table 4. The complete list of all generated definitions is given in Supplementary Tables S8 and S9.

The top definition was in over 40% valid, meaning that is was a proper definition containing useful information about the term. The results increased to 55% (GO) and 78% (MeSH) for the top 10 definitions (Table 6). Over half of these 78% were actually correct definitions showing that the automated definitions are by and large of accetable quality for interactive ontology generation.

Table 6.

Evaluation of generated definitions for 500 GO and 500 MeSH terms

| 500 GO (%) |

500 MeSH (%) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Correct | Valid | Correct | Valid | |

| Top 1 | 21.9 | 41.2 | 32.0 | 47.0 |

| Within top 5 | 27.8 | 54.6 | 49.8 | 72.6 |

| Within top 10 | 27.8 | 54.6 | 53.6 | 78.2 |

For 22−38% of terms the top ranked definition captured aspects of the true definition, in 41−47% it was a valid definition, but not similar to the original one. Within the top 10 ranked definitions a valid definition was found for 55−78% of terms.

4.3 Evaluation of taxonomy induction

Parent–child relations from definition: taxonomy induction, i.e. finding parent–child relationships, is an easy problem if one has a definition of the form ‘A is a B with property C’, where B is the parent of A. Nearly all definitions in GO and MeSH mention at least one term. But, Table 5 also shows that only 16% (GO) and 37% (MeSH) contain the parent in the definition. However, it increases to over 50% when B is not necessarily the parent but an ancestor of the defined term. Interestingly, some of the sub-ontologies, namely organism, anatomy, geography and cellular component provide much better results with values of over 70% (for a detailed break down see Supplementary Tables S1 and S2). As a consequence, DOG4DAG uses its generated definitions as source for predicted parents.

Based on the 10 000 definitions generated for 1000 terms in Section 4.2, we tested how many definitions contain the parent or an ancestor of the term the definition was generated for (Table 7). For 13% (GO) and the 26% (MeSH) the top 10 generated definitions contained the direct parent term, thus DOG4DAG will predict it. For 38% (GO) and 54% (MeSH) the top 10 generated definitions contained an ancestor term, thus DOG4DAG will predict some correct, but indirect, ancestor relationship. For the vast majority of GO and MeSH terms already the top ranked generated definition contains the parent/ancestor. The numbers for ancestors within the top 10 generated definitions correspond nicely to the manual curations in Table 6, with a correct definition in the top 10 for 28% of the GO and 54% of the MeSH terms.

Table 7.

Evaluation of taxonomic information contained in generated definitions for 500 GO and 500 MeSH terms

| 500 GO (%) |

500 MeSH (%) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parent | Ancestor | Parent | Ancestor | |

| Contained in top 1 | 12.2 | 32.4 | 20.2 | 37.0 |

| Contained in top 10 | 13.4 | 38.0 | 26.0 | 54.4 |

For 26% of the 500 randomly selected MeSH terms the parent and for 54% some ancestor could be found in the top 10 generated definitions.

Parent–child relations from co-occurrences: pattern-based methods as discussed above are known to show high precision but very low recall (Hearst, 1992). To investigate whether more data could increase the number of predictions, we also validated a statistical approach based on similarity of document vectors. The key idea is to represent all terms as high dimensional binary document vector, which indicates whether the term is present in the documents or not. Next, the distance between two terms is defined as the cosine similarity of their document vectors. In the second phase of the algorithm, a graph is defined. If two terms have distance below a given threshold, then an edge between the two terms is added. The graph is undirected and hence not yet suitable to infer parent–child relations. This is achieved by identifying the most central term in the graph and defining this term as root. A similar method has been described in (Heymann and Garcia-Molina, 2006) in the context of social networks and image tagging.

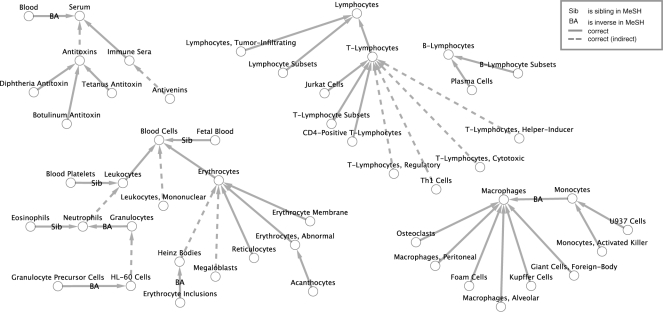

With this statistical approach we obtained 23 270 parent–child relations for MeSH. Depending on the threshold (see Fig. 3), the statistical approach achieves a precision of 27% with recall of 2%. If nearly correct relations are considered precision increases to 34% (Table 8). The statistical approach demonstrates that taxonomic relationships can be predicted without linguistic information, although not for all areas, and not for the whole MeSH. As a positive example consider Figure 3, which shows relations for the MesH term blood with over 60% correctly identified parent-child relations. Since the approach is computationally intensive (generated terms have to be found in all documents and pairwise distance has to be computed), it is not feasible to run it on a desktop computer and is hence not part of the plug-in.

Fig. 3.

Generated taxonomy for MeSH sub tree ‘Blood’. Result for co-occurrence-based taxonomy induction as described in Section 4.3 using a maximum of 10 000 000 documents per node and a threshhold of 0.01.

Table 8.

Precision, recall and F-measure for automatic induction of MeSH using document-wise co-occurrences in PubMed abstracts

| Threshhold Heymann alg. | Precision AB | Recall AB | F-measure AB | Precision AB|A..B|BA | Recall AB|A..B|BA | F-measure AB|A..B|BA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MeSH | 0.5 | 0.28 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.34 | 0.02 | 0.04 |

| MeSH | 0.1 | 0.15 | 0.11 | 0.13 | 0.21 | 0.17 | 0.19 |

| MeSH | 0.01 | 0.12 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.19 | 0.20 | 0.19 |

Results AB only regard relations as correct which exist in MeSH, while AB|A..B|BA also regards prediction of ancestors or the inverse direct relations as correct.

4.4 Runtime

In DOG4DAG, processing terms from 250 scientific abstracts takes 3–4 s and a 250 page PDF document 7 s. Generating definitions for a term takes <5 s. This allows DOG4DAG to be part of an interactive application, such as the OBO-Edit Ontology Generation plug-in.

5 DISCUSSION

In the following sections, we will discuss DOG4DAG in relation to other tools supporting aspects of automatic ontology creation and will take position on how DOG4DAG's input complies to the design guidelines proposed by (Schober et al., 2009).

5.1 Ontology learning tools

Over the past few years some text-mining approaches and systems for ontology learning have been developed such as TerMine, Text2Onto, OntoLT for Protégé or Ontolearn.

TerMine based on the C-value method (Frantzi et al., 2000) retrieves and ranks multi-word phrases. Since 15% of all MeSH terms and synonyms, as well as most gene names consist of a single word, DOG4DAG's inclusion of single words as terms is an important extension not present in TerMine. DOG4DAG achieves this by ranking terms according to their relative importance (tf-idf). The grouping of all lexical variants and abbreviations leads to better frequency counts and less noise. Text2Onto (Cimiano and Völker, 2005) is an ontology learning framework including a graphical user interface which supports terminology recognition, hypernymic and mereological relationship extraction. The OntoLT Protégé Plug-in [olp.dfki.de/OntoLT/OntoLT.htm] includes rule-based extraction of candidate terms and relations based on linguistic features of provided texts. Both systems build on strong linguistic foundations but require user input prior to the generation of terms or relations, such as the creation of rules in Text2Onto and an annotated corpus of documents for OntoLT (Buitelaar et al., 2004). Our evaluation in Alexopoulou et al. (2008) showed, that the term generation of DOG4DAG performs equally or better than other state-of-the-art systems like Text2Onto and TerMine.

5.2 Design guidelines

An important question is whether generated terms satisfy naming guidelines proposed for manually created terms as put forward by Schober et al. (2009). The authors comprehensively evaluated existing open biomedical ontologies and defined a number of guidelines for naming concepts to reach acceptance by the community. This is satisfied by all term generation approaches since they are based on text, which should be the output of the community in question. In DOG4DAG, this is additionally satisfied by supporting generation of terms from PubMed abstracts, web queries, text files and repositories of PDF documents. According to Schober et al., abbreviations should be captured with the terms. This is indeed the case in DOG4DAG, which groups variations of terms and their abbreviations. Schober et al. promote the avoidance of ambiguity. In DOG4DAG, ambiguous terms are easily identified through their generated definitions and can hence be avoided. Schober et al. also recommend to avoid negations and conjunction in terms. Since negations and conjunctions are rarely used directly in text, DOG4DAG does not suffer from this problem. We found that for in total 420 000 terms generated for the evaluation in section 4.1 only 10 contained the words without, excluding or not and only 462 the word and Schober et al. also emphasize the importance of term re-use. DOG4DAG supports the re-use of existing ontology terms by checking whether terms or their discovered variants exist in other OBO ontologies. If this is the case, the use of the existing term label is recommended and it is offered to include the terms descendants.

5.3 Biocuration

Winnenburg et al. (2008) conclude that manual curation of literature is necessary for high-quality annotation but can be supported by automated methods. Systems like Textpresso (Müller et al., 2004) successfully support manual curation and recently have been estimated to speed up the curation process of C.elegans proteins to GO cellular components at least 8-fold (Van Auken et al., 2009).

Integrated in the GO annotation process described by Hill et al. (2008), DOG4DAG helps to identify appropriate ontology annotation terms, by showing the GO terms used in literature and in the same way collecting the literature reference to include in the annotation record. In cases where novel terms need to be created DOG4DAG will help to define and place the new term in the GO.

Definitions of terms in ontologies are important, but cumbersome to define. As Table 5 showed nearly all GO and MeSH terms are defined. However, for more specialized ontologies, this is not the case. In over 90 OBO ontologies, there are 99 418 terms without definition. Thus, there is a huge potential to save manual labor when defining terms using DOG4DAG.

5.4 Limitations

There are two major limitations: the ability to compose terms and the ability to extract specific relations.

Composition of terms: currently, there are many efforts to understand the composition of ontology terms following patterns (Mungall, 2004; Ogren et al., 2004). In Aranguren et al. (2008) the authors discussed two design patterns for terms. DOG4DAG does not support such a composition process. However, DOG4DAG's filtering of terms helps to realize the value partition pattern. For example, after a search for ‘stem cell’ one can filter to keep only terms containing ‘stem cell’ obtaining among others the value partition ‘mesenchymal’, ‘hematopoetic’ and ‘neural’.

Extraction of specific relations: the second limitation of DOG4DAG is the extraction of relations as promoted in (Smith et al., 2005; Soldatova and King, 2005). The latter, also mentions that ontologies should contain axioms. DOG4DAG only deals with extraction of parent–child relationships. Since part of speech tagging is used there is in principle the possibility to extract relations from verb phrases. But since this requires both terms to appear in one sentence, the coverage would be much lower and is therefore currently omitted.

6 CONCLUSION

Overall, the above results show a high number of existing ontology terms among the generated terms, show the ability to generate valid definitions for up to 78% of terms, and show the prediction of up to 54% taxonomic relations to parents or ancestors in MeSH or GO. Thus, our results demonstrate that text-mining can support ontology engineers with highly relevant terms, definitions and parent–child relations. Ontologies are unlikely to be ever fully automatically generated, but text-mining can contribute to a semi-automated interactive creation process, which satisfies accepted design guidelines.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We gratefully acknowledge Götz Fabian, Marcel Hanke and Atif Iqbal for their support developing the GUI; the OBO Edit Working Group and especially Amina Abdulla for support with OBO-Edit; David Hill and Midori Harris for giving insights into the GO curation process; the EBI Ontology Lookup Service; Robert Stevens and Simon Jupp for their early feedback on the term generation method; Rainer Winnenburg, Christof Winter and Anne Tukkannen for the critical assessment of the final article; Alexander Mestiashvili for keeping all services up and running.

Funding: BMBF Projects Go3R (0315489A); GoOn (01MQ09009); FORMAT (03FO1132); the EU project PONTE (FP7-247945).

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

REFERENCES

- Alexopoulou D, et al. Terminologies for text-mining; an experiment in the lipoprotein metabolism domain. BMC Bioinformatics. 2008;9(Suppl. 9):S2. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-S4-S2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aranguren M, et al. Ontology design patterns for bio-ontologies: a case study on the cell cycle ontology. BMC Bioinformatics. 2008;9(Suppl. 5):S1. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-S5-S1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashburner M, et al. Gene Ontology: tool for the unification of biology. The Gene Ontology Consortium. Nat. Genet. 2000;25:25–29. doi: 10.1038/75556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodenreider O, Stevens R. Bio-ontologies: current trends and future directions. Brief. Bioinform. 2006;7:256. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbl027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brants T. Proceedings of the 6th Conference on Applied Natural Language Processing. Morristown, NJ, USA: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2000. TnT: a statistical part-of-speech tagger; pp. 224–231. [Google Scholar]

- Buitelaar P, et al. The Semantic Web: Research and Applications. Vol. 3053. Berlin / Heidelberg: Springer; 2004. A Protégé plug-in for ontology extraction from text based on linguistic analysis; pp. 31–44. of LNCS. [Google Scholar]

- Caraballo SA. Proceedings of the 37th annual meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics on Computational Linguistics. Morristown, NJ, USA: 1999. Automatic construction of a hypernym-labeled noun hierarchy from text; pp. 120–126. Association for Computational Linguistics. [Google Scholar]

- Cimiano P, Völker J. Text2Onto - a framework for ontology learning and data-driven change discovery. In: Montoyo A, et al., editors. Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Applications of Natural Language to Information Systems (NLDB) Vol. 3513. Alicante, Spain: Springer; 2005. pp. 227–238. of LNCS. [Google Scholar]

- Cimiano P, et al. Learning concept hierarchies from text corpora using formal concept analysis. J. Artif. Int. Res. 2005;24:305–339. [Google Scholar]

- Cote R, et al. The Ontology Lookup Service, a lightweight cross-platform tool for controlled vocabulary queries. BMC Bioinformatics. 2006;7:97. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day-Richter J, et al. Obo-edit—an ontology editor for biologists. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:2198–2200. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degó#rski L, et al. Proceedings of the Sixth International Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC'08) Marrakech, Morocco: European Language Resources Association; 2008. Definition extraction using a sequential combination of baseline grammars and machine learning classifiers. [Google Scholar]

- Echihabi A, et al. Proceedings of the 12th Text Retrieval Conference (TREC-2003) Gaithersburg, Maryland: 2003. Multiple-engine question answering in TextMap; pp. 772–781. [Google Scholar]

- Evans DA, Zhai C. Proceedings of the 34th annual meeting on Association for Computational Linguistics. Morristown, NJ, USA: Association for Computational Linguistics; 1996. Noun-phrase analysis in unrestricted text for information retrieval; pp. 17–24. [Google Scholar]

- Frantzi K, Ananiadou . Technical report. Department of Computing of Manchester Metropolitan University; 1995. Statistical measures for terminological extraction. [Google Scholar]

- Frantzi K, et al. Automatic recognition of multi-word terms: the C-value/NC-value method. Int J. on Dig. Lib. 2000;3:115–130. [Google Scholar]

- Han K.-S, et al. A definitional question answering system based on phrase extraction using syntactic patterns. IEICE - Trans. Inf. Syst. 2006;E89-D:1601–1605. [Google Scholar]

- Hearst MA. Proceedings of the 14th conference on Computational linguistics. Morristown, NJ, USA: Association for Computational Linguistics; 1992. Automatic acquisition of hyponyms from large text corpora; pp. 539–545. [Google Scholar]

- Heymann P, Garcia-Molina H. Technical Report 2006–10. Stanford University; 2006. Collaborative creation of communal hierarchical taxonomies in social tagging systems. [Google Scholar]

- Hill D, et al. Gene ontology annotations: what they mean and where they come from. BMC Bioinformatics. 2008;9(Suppl. 5):S2. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-S5-S2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howe D, et al. Big data: The future of biocuration. Nature. 2008;455:47–50. doi: 10.1038/455047a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JB, et al. Automatic extension of Gene Ontology with flexible identification of candidate terms. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:665–670. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B, et al. WWW '03: Proceedings of the 12th international conference on World Wide Web. New York, NY, USA: ACM; 2003. Mining topic-specific concepts and definitions on the web; pp. 251–260. [Google Scholar]

- Müller HM, et al. Textpresso: an ontology-based information retrieval and extraction system for biological literature. PLoS Biol. 2004;2:e309. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mungall CJ. Obol: integrating language and meaning in bio-ontologies: conference papers. Comp. Funct. Genomics. 2004;5:509–520. doi: 10.1002/cfg.435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navigli R, Velardi P. Learning domain ontologies from document warehouses and dedicated web sites. Comput. Linguist. 2004;30:151–179. [Google Scholar]

- Ogren PV, et al. The compositional structure of gene ontology terms. Pacific Symposium on Biocomputing. 2004:214–225. doi: 10.1142/9789812704856_0021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson PN, et al. The human phenotype ontology: a tool for annotating and analyzing human hereditary disease. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2008;83:610–615. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryu P.-M, Choi K.-S. Proceedings of the 2nd Workshop on Ontology Learning and Population: Bridging the Gap between Text and Knowledge. Sydney, Australia: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2006. Taxonomy learning using term specificity and similarity; pp. 41–48. [Google Scholar]

- Sanderson M, Croft BW. SIGIR '99: Proceedings of the 22nd annual international ACM SIGIR conference on Research and development in information retrieval. New York, NY, USA: ACM; 1999. Deriving concept hierarchies from text; pp. 206–213. [Google Scholar]

- Schober D, et al. Survey-based naming conventions for use in obo foundry ontology development. BMC Bioinformatics. 2009;10:125. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith B, et al. Relations in biomedical ontologies. Genome Biol. 2005;6:R46. doi: 10.1186/gb-2005-6-5-r46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith B, et al. The OBO Foundry: coordinated evolution of ontologies to support biomedical data integration. Nat. Biotechnol. 2007;25:1251–1255. doi: 10.1038/nbt1346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snow R, et al. Learning syntactic patterns for automatic hypernym discovery. In: Saul LK, et al., editors. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 17. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 2004. pp. 1297–1304. [Google Scholar]

- Snow R, et al. ACL-44: Proceedings of the 21st International Conference on Computational Linguistics and the 44th annual meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics. Morristown, NJ, USA: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2006. Semantic taxonomy induction from heterogenous evidence; pp. 801–808. [Google Scholar]

- Soldatova LN, King RD. Are the current ontologies in biology good ontologies? Nat. Biotechnol. 2005;23:1095–1098. doi: 10.1038/nbt0905-1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Auken K, et al. Semi-automated curation of protein subcellular localization: a text mining-based approach to gene ontology (go) cellular component curation. BMC Bioinformatics. 2009;10:228. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voorhees EM. Overview of the TREC 2003 Question Answering Track. Proceedings of the 12th Text Retrieval Conference (TREC-2003) 2003:54–68. [Google Scholar]

- Wermter J, Hahn U. ACL-44: Proceedings of the 21st International Conference on Computational Linguistics and the 44th annual meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics. Morristown, NJ, USA: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2006. You can't beat frequency (unless you use linguistic knowledge): a qualitative evaluation of association measures for collocation and term extraction; pp. 785–792. [Google Scholar]

- Winnenburg R, et al. Facts from text: can text mining help to scale-up high-quality manual curation of gene products with ontologies? Brief. Bioinform. 2008;9:466–478. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbn043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J, et al. Trec 2003 QA at BBN: Answering definitional questions. Proceedings of the 12th Text Retrieval Conference (TREC-2003) 2003:98–106. [Google Scholar]

- Yang H, et al. Qualifier in TREC-12 QA main task. Proceedings of the 12th Text Retrieval Conference (TREC-2003) 2003:480–488. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.