Abstract

Motivation: We present a method for directly inferring transcriptional modules (TMs) by integrating gene expression and transcription factor binding (ChIP-chip) data. Our model extends a hierarchical Dirichlet process mixture model to allow data fusion on a gene-by-gene basis. This encodes the intuition that co-expression and co-regulation are not necessarily equivalent and hence we do not expect all genes to group similarly in both datasets. In particular, it allows us to identify the subset of genes that share the same structure of transcriptional modules in both datasets.

Results: We find that by working on a gene-by-gene basis, our model is able to extract clusters with greater functional coherence than existing methods. By combining gene expression and transcription factor binding (ChIP-chip) data in this way, we are better able to determine the groups of genes that are most likely to represent underlying TMs.

Availability: If interested in the code for the work presented in this article, please contact the authors.

Contact: d.l.wild@warwick.ac.uk

Supplementary information: Supplementary data are available at Bioinformatics online.

1 INTRODUCTION

Approaches to the elucidation of gene regulatory networks have often relied on the use of clustering methodologies, grouping genes on the basis of expression patterns over time, treatments and/or tissues. The genes in a given cluster are usually assumed to be potentially functionally related or to be influenced by common upstream factors. For example, Eisen et al. (1998) found that in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, genes that clustered together did indeed often share similar biological function, and a large number of subsequent authors have found the same, sometimes even being able to verify the results experimentally (e.g. Ihmels et al., 2002).

Application of these approaches to gene expression data have led to the recognition that gene regulation is often performed by regulatory programmes or transcriptional modules (TMs); sets of co-regulated genes that share a common biological function and are regulated by a common set of transcription factors. Ihmels et al. (2002) devised a method for identifying TMs by assigning genes to clusters in a context-dependent manner. A gene could be assigned to several clusters, resulting in overlapping TMs, a feature which is biologically meaningful since a gene could be involved in multiple biological processes.

Clustering on the basis of expression data alone, however, only indicates co-expression, and does not directly identify co-regulation. The expression patterns of genes in the same cluster may be correlated for reasons other than co-regulation—the effects of experimental measurement error may be important, for example. Due to the complexity of gene regulatory networks, as well as the limitations of any given source of noisy experimental data, it is advantageous to make TM inferences using multiple sources of data. In addition to gene expression data, a range of other data types have been used to enhance the reconstruction of gene networks. These include information about transcription factor binding derived from experimental techniques such as ChIP-chip, sequence data and even information derived from relevant scientific literature. Both Segal et al. (2003a) and Kundaje et al. (2005) have described methods to integrate expression and sequence data within the framework of a probabilistic graphical model, using the method of expectation maximization —a statistical technique for maximum likelihood estimation of model parameters from incomplete data. Segal et al. (2003b) applied a variant of this approach to infer regulatory modules in S.cerevisiae, together with their component regulators, under the assumption that the regulators themselves are transcriptionally regulated, at least under a subset of conditions. Bar-Joseph et al. (2003) described a method to integrate ChIP-chip and expression data based on an exhaustive iterative search over possible combinations of regulators, which identifies a subset of gene targets with highly correlated expression patterns.

Dirichlet process mixture models (DPMs; Antoniak, 1974; Ferguson, 1973) are a class of Bayesian non-parametric models that has been widely used for clustering (Dahl, 2006; Liu et al., 2006; Medvedovic and Sivaganesan, 2002; Medvedovic et al., 2004; Qin, 2006; Rasmussen et al., 2009; Rasmussen, 2000; Wild et al., 2002). DPMs have the interesting property that the prior probability of a new data point joining a cluster is proportional to the number of points already in that cluster, thus encoding a natural clustering tendency. Clustering strength is controlled via a hyperparameter α, which sets the expected number of clusters as a function of the number of clustered items. By inferring α we can therefore determine the posterior distribution of the number of clusters.

Hierarchical Dirichlet Process models [HDPMs as defined by Teh et al. (2006)] are the hierarchical extension of DPMs. They consist of a DPM for each of a number of different contexts, with the mixture components for each context being drawn from a master list of mixtures from the next level of the hierarchy. A wider range of HDPMs are reviewed in Teh and Jordan (2010). Reid et al. (2009) use a type of HDPM to identify TMs from transcription factor binding site sequence data. Gerber et al. (2007) use HDPMs to model gene expression programs in a variety of tissues.

Effective combination of different datasets can be an effective way to identify TMs. Liu et al. (2007) introduced a HDPM that assigns a DPM to each of a pair of datasets (e.g. gene expression and ChIP-chip) and connects them via a common hyperparameter, α. By producing combined results from the sampled clustering for both contexts, they are able to produce a form of flexible data integration. As we shall see below, the Liu et al. approach is a special case of the model we present in this article.

2 METHODS

Our aim is to cluster genes together on the basis of both gene expression and ChIP-chip (transcription factor binding site) information. We wish to identify the genes that possess the same clustering structure across both datasets, as these are more likely to represent underlying TMs and hence share specific biological function/s. We expect that the information coming from each dataset will be uncertain and possibly contradictory. Therefore, we wish to distinguish (on a gene-by-gene basis) between genes that can sensibly have their data fused and those for which there is contradiction.

2.1 The model

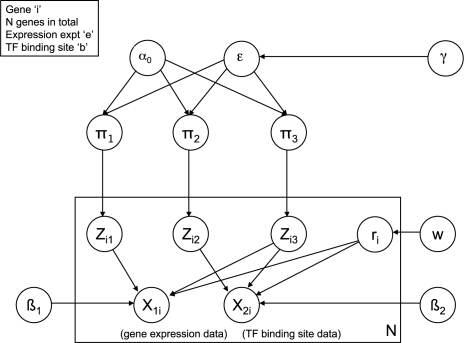

We construct our model (shown in Fig. 1) from a two-level hierarchy of DPMs. This model can be regarded as a modified version of the HDPM presented in Teh et al. (2006). A naïve use of HDPMs for data integration may fail since it assumes that all data sources are clustered identically. Our principal innovation is to include, for each gene, an indicator variable that determines whether the gene should join a cluster based on both data sources combined (via a product of likelihoods) or whether it should be clustered separately for each dataset.

Fig. 1.

Graphical representation of the model presented in this article. The parameters are defined in Section 2.

The genes are assigned to three contexts, each defining a clustering partition via a DPM. One context contains the genes that are fused across the two datasets. The other two contexts are for the unfused genes, one clustering solely on the basis of expression data and the other using the transcription factor binding dataset. The fusion indicator variables are learnt as part of the inference process (carried out via a Gibbs sampler), allowing us to determine the posterior probability that any given gene will be fused.

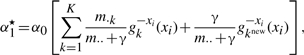

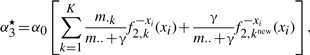

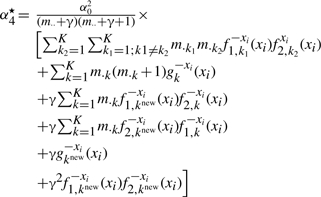

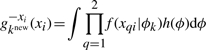

We define our model as follows [using the same notation as Teh et al. (2006)]. We have n genes, for each of which we have two sets of measurements (expression and ChIP-chip). Each gene can either be considered for the two datasets separately or we can fuse them together, giving a single (product) likelihood. This gives us three contexts overall. Let xji be the observed response for i-th gene in the j-th context. Note that when sampling, genes can flip from a fused to unfused state and vice versa.

Each context j∈{1, 2, 3} has a countably infinite number of mixture components, of which K are occupied. Each component k∈{1, …, K} has a mixture weight denoted by πjk and a parameter vector θjk, where the set of parameters may be different for the different contexts.

Each gene is assigned to a mixture component via the indicator variable Zij, giving us the following equations.

| (1) |

The conditional likelihood for each gene is then:

| (2) |

where Lj is the likelihood we assign to model the data and θjk are the parameter values for mixture component k in context j.

These are assigned the stick-breaking prior associated with the Dirichlet process (Teh et al., 2006)

| (3) |

where Vjk are mutually independent and Vjk ∼ Be(1, α) which we write Stick(α). Marginalizing over the mixture weights gives us a DPM for each context. Similarly, ϵ are the mixture weights for the second level of the Dirichlet process hierarchy. Again, these are assigned a stick-breaking prior and marginalized over, so that they do not have to be considered explicitly in the analysis.

| (4) |

| (5) |

The hyperparameters α0 and γ are the concentration parameters for the two levels of the Dirichlet process hierarchy. α0 is shared across all three contexts, representing the prior belief that they are all representing the same biological system and hence we should expect the same number of underlying TMs. These can be inferred and therefore are assigned vague gamma priors as follows.

| (6) |

| (7) |

We choose the component likelihoods to reflect the nature of the two datasets. For the expression data, we discretize the measured value for each gene into three levels, representing under-, over- or unchanged expression. This is something of a simplifying assumption, but makes our analysis more robust to the non-Gaussian noise typical of gene expression data, and is an approach that has been shown to be effective (see e.g. Gerber et al., 2007; Savage et al., 2009). We therefore choose the component likelihood for the expression data to be a naïve Bayes model, constructed from a product of multinomial distributions.

For the ChIP-chip data, we have statistical (P-value) information as to whether or not a given transcription factor binds to a given gene. By thresholding these values, we obtain sparse binary data, indicating whether binding has occurred. We choose to model these data using a so-called ‘bag-of-words’ model, e.g. a multinomial likelihood over transcription factors. This has the advantage that only counts over genes are important, meaning that a large number of zeros in the data can be handled safely. Note that in both cases we choose to apply (conjugate) Dirichlet priors.

For the expression data, we have

| (8) |

where Ba=∑bβab and Na=∑b xab, a is the index over features and b is the index over discrete data values. The βab are the Dirchlet prior hyperparameters, which in this case are all set to 0.5 (the Jeffreys' value).

For the ChIP-chip data, we have

| (9) |

where B=∑a βa and N=∑a xa, and a is the index over features. The βa are the Dirichlet prior hyperparameters, which in this case are all set to 0.5 (the Jeffreys' value). The above two equations are obtained from Equation (2) for a particular cluster k by integrating out the parameters θ.

We encode the notion of data fusion for a given gene i by allowing the possibility of taking the product of likelihoods over the two datasets. So, if the likelihood parameters for contexts one and two are given by θ1i and θ2i, we have the following equations.

We introduce an extra latent variable ri for each gene with

| (10) |

If ri=1 (corresponding to a fused gene) then:

| (11) |

And if ri=0 (corresponding to an unfused gene) then:

| (12) |

| (13) |

This defines three contexts. Unlike the HDPM, we have

| (14) |

| (15) |

| (16) |

| (17) |

where F0(j) represents the marginal distribution of θj under F0. The hierarchical Dirichlet process structure allows sharing of clusters across the unfused and fused contexts. For example, an unfused gene can be allocated to the same cluster as fused genes for gene expression but allocated to a different cluster (shared by different fused genes) for transcription factors.

We choose to fix w=0.5 for the analyses in this article, representing that we have no prior knowledge of the degree to which these datasets should fuse. We note that it is also straightforward to sample from w and we run a test of this, the results of which can be seen in Table 3. Details of the algorithm to implement this model, in particular a Gibbs sampler, can be found in Appendix A.

Table 3.

The BHI scores for galactose utilization with Harbison et al. ChIP data, for comparison with Table 1

| Similarity matrix | w | No. of genes | BHI (all) | BHI (bp) | BHI (mf) | BHI (cc) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| fused genes | 0.5 | 72 | 0.49 ± 0.01 | 0.42 ± 0.01 | 0.35 ± 0.01 | 0.49 ± 0.01 |

| fused genes | 1 | 205 | 0.39 ± 0.01 | 0.22 ± 0.01 | 0.19 ± 0.01 | 0.37 ± 0.01 |

| fused genes | sampled | 56 | 0.49 ± 0.01 | 0.40 ± 0.01 | 0.32 ± 0.01 | 0.49 ± 0.01 |

The Lee et al. ChIP data are used in this article to mimick the Liu et al. analysis. The results here show that the Harbison et al. data result in a greater number of fused genes, with similar overall BHI scores. Also shown are results for a run where w is sampled using a Gibbs sampler. This shows a small degradation over the w=0.5 .case.

2.2 Special cases of the model

Our model has two special cases that are of interest and represent alternative ways of approaching data integration. w=0 gives us the model of Liu et al. (2007). In this model, there is no direct data fusion (in the sense that all the ri=0). Instead, information is shared via a common hyperparameter, α0, between the clustering for each dataset. Each dataset is therefore clustered (almost) separately, but benefiting from this weak sharing of information via the hyperparameter. w=1 gives us simple data integration by taking the product of likelihoods and forcing all genes to be part of a single clustering partition. With w=1, only the fused context is used (genes can never be unfused) and so we have a straightforward DPM with a product of likelihoods over the two datasets.

2.3 Extracting modules from the posterior samples

Once we have explored the model space using Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) sampling, we wish to extract useful results from the samples. In particular, we wish to identify TMs, which in our model correspond to groups of genes that fused with high probability and that are often found in the same fused cluster. This is a non-trivial challenge, as each MCMC sample contains a large number of parameters (mixture component labels for each gene in each of three contexts, ri for each gene, plus the global hyperparameters). We therefore require a way to summarize the results. To do this, we choose to form a posterior similarity matrix (Fritsch and Ickstadt, 2009). From this we will extract a clustering partition, which will correspond to transcriptional modules. The posterior similarity matrix is an (ngenes × ngenes) matrix where each element gives the posterior probability that a given pair of genes are found in the same cluster (and hence also in the same context). These values can be estimated simply by counting the MCMC samples in the appropriate way.

A major advantage of our model is that it identifies how likely each gene is to be fused (estimated from the ri values over MCMC samples). By rejecting genes with low P(ri=1 | x), we can identify more tightly defined TMs. For this article, we choose to define ‘fused’ as being P(ri=1 | x)≥0.5 (the prior value we assign to w for the full model).

From the posterior similarity matrix, we extract the most likely cluster partition using the method of Fritsch and Ickstadt (2009), which minimizes a defined loss function that is equivalent to maximizing the adjusted Rand index between estimated and true clustering partitions. We note that this represents a summarization of the full results implicit in the analysis. Some kind of compromise of this nature is inevitable, simply due to the richness of the posterior distribution of our model. As we shall demonstrate, this approach still leads to superior results and hence biological insight.

We can also extract other useful quantities from the posterior MCMC samples. For example, the 1D marginal distributions of the hyperparameters, the number of fused clusters and the number of fused genes are all easily determined.

2.4 Quality measures

We are interested in identifying TMs with well-defined biological function/s. Our quality measures should therefore reflect this. We choose two measures, both using the Gene Ontology (GO) database.

The first measure is the Biological Homogeneity Index (BHI; Datta and Datta, 2006). This is a global measure of how biologically homogeneous a given clustering partition is (as measured here using GO annotations). Clusters where many genes share annotations will lead to a high BHI score and vice versa. Perfect agreement for all GO terms (which is highly unlikely) would lead to a score of unity.

We compute error estimates of these BHI scores by performing 10 random combinations of the 20 MCMC chains (chosen via bootstrap sampling, eg. so that a given chain may be selected multiple times), finding in each case the clustering partition and hence the BHI score. This gives us a measure of any uncertainty due to inadequate mixing of the MCMC chains.

The second measure is to find GO terms that are over-represented in any given module, relative to the background population of genes. We use the R package GOstats (Falcon and Gentleman, 2007) to apply a hypergeometric test to each GO term in each cluster. We apply this analysis to all GO terms in the three ontologies (cellular component, molecular function and biological process). We account for the dependent, hierarchical structure of the ontologies using the relevant option in the call to the GOstats function ‘hyperGTest’. We correct for multiple hypotheses using a Bonferroni correction.

2.5 Data

We perform two different analyses in this article, in each case analysing data from S.cerevisiae. To facilitate comparison with earlier work, in both cases we use ChIP-chip data from Lee et al. (2002) to provide information on transcription factor binding activity. This dataset contains nearly 4000 interactions between regulators and promoter regions, representing 6270 yeast genes and 106 transcriptional regulators.1.

We use two different gene expression datasets in the two analyses. The first one (referred to subsequently as the galactose utilization data) is taken from a subset of the expression dataset of Ideker et al. (2001), which has been widely used for the validation of clustering methods (Savage et al., 2009; Yao et al., 2008; Yeung et al., 2003). These data are a series of expression measurements across 20 experiments representing systematic perturbations of the yeast galactose utilization pathway. The subset used consists of 205 genes whose expression patterns reflect four functional categories (biosynthesis, protein metabolism and modification; energy pathways, carbohydrate metabolism and catabolism; nucleobase, nucleoside, nucleotide and nucleic acid metabolism; transport), based on GO annotations. However, as Yeung et al. (2003) note, since this array data may not fully reflect these functional categories, these classifications should be used with caution.

For the other analysis (referred to as the cell cycle data), we use gene expression measurements of the mitotic yeast cell cycle of Cho et al. (1998), which was chosen to facilitate direct comparison with the results of Liu et al. (2007), who also analysed this data. For this dataset, we keep only the genes that were identified as having a Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway, following the procedure of Liu et al. (2007). We note that there are small differences in the number of genes selected in this way (949 versus 1165 in this article), due to differences in the version of the KEGG database used.

2.6 Data processing

For both expression datasets, we discretize the data into three levels. This has two benefits. First, it makes our analysis more robust to the non-Gaussian (and hence hard to model) noise distribution of the data. Secondly, it makes the task of data modelling more straightforward. To optimize the binning of the data, we use the Bayesian Hierarchical Clustering (BHC) package (Savage et al., 2009) to find an optimized binning and assume that this will then also be reasonably optimal for this analysis.

For the ChIP-chip dataset, we follow the procedure of Lee et al. (2002) and threshold the data at a P-value of 0.001, giving us a sparse dataset where the detections are robust, at the expense of a larger proportion of false negatives (Lee et al. estimate 6–10% false positives and that about one-third of the interactions are missed).

3 RESULTS

The results of each data integration analysis are rich and detailed. In this section, we consider a number of metrics and highlight significant aspects of the results for each dataset. For comparison, we also run clustering analyses using the BHC algorithm (Savage et al., 2009) to analyse the gene expression data alone. This gives us a baseline result with which to compare the data integration results.

It is important to assess the convergence of any MCMC analysis. All analyses on the galactose dataset comprise 20 MCMC chains, each of 50 000 samples (after removal of 10 000 burn-in samples). All analyses on the cell cycle data set comprise 20 MCMC chains, each of 5000 samples (after removal of 1000 burn-in samples). To speed up our subsequent analyses, we sparse sample each chain by a factor of 10.

We include as Supplementary Material plots of 1D hyperparameter posterior PDFs, both overall and for each MCMC chain. These demonstrate that the MCMC analyses are converging adequately. We also perform Geweke convergence tests (Geweke, 1992) on the hyperparameters of each chain (α0 and γ) for the w=0.5 case. For the galactose dataset, we find 30 of 40 tests (20 chains, 2 hyperparameters) have a z-score <2, with a maximum outlier of 3.48. For the cell cycle dataset, we find 28 of 40 tests have a z-score <2, with a maximum outlier of 5.53. We conclude that our chains are reasonably well (although not perfectly) mixed, although in both cases it is important that we combine multiple chains.

The algorithm is implemented in Matlab and run on 3 GHz cluster nodes (20 in parallel, one per MCMC chain). On the galactose utilization dataset (205 genes), the code produces 500 samples per chain per hour. On the cell cycle dataset (1165 genes), the code produces 40 samples per chain per hour. On a larger sample of 2332 genes [from the stress data of Gasch et al. (2000)], the code produces 10 samples per chain per hour. This scaling suggests that for large (genome-scale) datasets it may be of value to investigate (for example) fast variational methods as an alternative to MCMC.

3.1 Galactose utilization dataset

In Table 1, we give the BHI scores for different analyses of the galactose utilization dataset. The outcome from our model (fused genes and w=0.5) extracts a subset of 51 genes with an overall BHI score that is 9% (3 SDs) higher than for any other method, indicating a greater degree of biological functional coherence. We note that all methods are superior to the BHC result for expression data alone (BHI = 0.323), except for the ChIP only analyses.

Table 1.

The BHI scores for the galactose utilization dataset

| Similarity matrix | w | No. of genes | BHI (all) | BHI (bp) | BHI (mf) | BHI (cc) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fused genes | 0.5 | 51 | 0.49 ± 0.03 | 0.43 ± 0.05 | 0.40 ± 0.04 | 0.49 ± 0.03 |

| Fused genes | 1 | 205 | 0.37 ± 0.01 | 0.22 ± 0.01 | 0.19 ± 0.01 | 0.37 ± 0.01 |

| Unfused (expression only) | 0 | 205 | 0.38 ± 0.01 | 0.26 ± 0.02 | 0.22 ± 0.02 | 0.38 ± 0.01 |

| Unfused (expression only) | 0.5 | 154 | 0.37 ± 0.03 | 0.30 ± 0.02 | 0.23 ± 0.02 | 0.37 ± 0.03 |

| Unfused (ChIP chip only) | 0 | 205 | 0.28 ± 0.03 | 0.13 ± 0.01 | 0.11 ± 0.02 | 0.25 ± 0.03 |

| Unfused (ChIP chip only) | 0.5 | 154 | 0.20 ± 0.06 | 0.06 ± 0.03 | 0.07 ± 0.04 | 0.19 ± 0.07 |

| Context-averaged (Liu et al.) | 0 | 205 | 0.38 ± 0.01 | 0.26 ± 0.02 | 0.22 ± 0.01 | 0.38 ± 0.01 |

| Context-averaged | 0.5 | 205 | 0.40 ± 0.01 | 0.24 ± 0.01 | 0.20 ± 0.01 | 0.40 ± 0.02 |

| Context-averaged | 1 | 205 | 0.37 ± 0.01 | 0.22 ± 0.01 | 0.19 ± 0.01 | 0.37 ± 0.01 |

We compute the BHI scores for each GO (biological process, molecular function and cellular component) and an overall value. The fused genes are those with a posterior probability of being fused of at least 0.5. All other genes are classed as unfused. Context-averaged similarity matrices are simply constructed by averaging the posterior similarity matrix over both contexts (i.e. datasets). This is the method used by Liu et al. For comparison, the result obtained using the BHC algorithm on the gene expression data alone is 0.323.

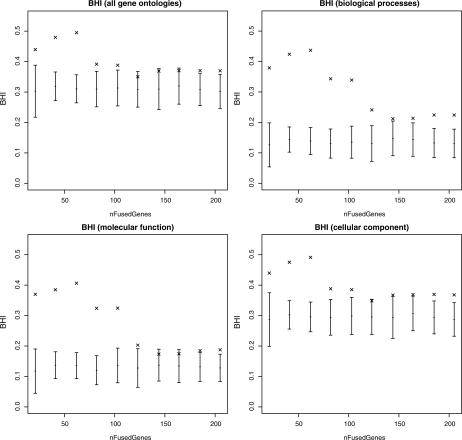

Figure 2 shows the variation of the BHI with the clustering partition resulting from keeping the top n genes, as sorted by P(ri=1 | x). There is a clear enriching effect on the BHI (and hence biological homogeneity) by selecting a subset of genes in this way.

Fig. 2.

Plots of the BHI for the galactose dataset, showing the variation with different numbers of fused genes. Shown are the BHI results for each GO separately, plus all three combined. In all cases, selecting 100 or fewer genes leads to an increase in the BHI score. The error bars show a distribution of randomized BHI scores where the cluster sizes and number of clusters are kept the same but gene names are drawn randomly from the 205 genes in the galactose dataset. By comparison, this gives us a measure of the enrichment of the fused gene clusters.

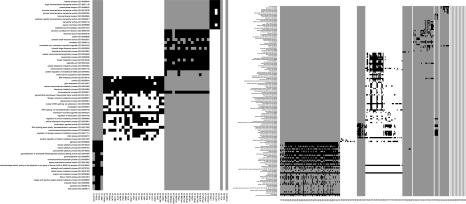

In Figure 3, we show a matrix of the significantly over-represented GO terms in each of the clusters we extract for the model (fused genes and w=0.5). Notable are the density of hits, and also the distinct block structure, which reflects that each cluster is tending to capture all the significance for given GO terms. These GO terms reflect the four functional categories previously identified in this data, but detailed inspection of the functional annotations of the genes in each cluster reveals a finer level of biological specificity than previously identified. Cluster 1 (counted from the left) comprises four genes involved in glycolysis and the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle. Cluster 2 represents genes involved in replication and RNA processing, while Cluster 3 comprises primarily ribosomal components. Cluster 4 comprises four hexose transporters, including at least one pseudogene, which, despite being non-functional, is nevertheless expressed.

Fig. 3.

Graphical representation of the significantly over-represented GO terms for each cluster of genes, for the galactose utilization (left) and cell cycle (right) datasets. Black indicates that a given gene is annotated with the relevant GO term and that the term is over-represented in that cluster.

Table 4 shows comparisons of over-represented GO terms with those obtained from the Liu method. In general, the data fusion GO terms are more enriched, with lower P-values and, in almost all cases, a higher proportion of the genes being annotated with the term.

Table 4.

Over-represented GO terms for one of the fused clusters extracted from the galactose utilization dataset (with w=0.5

| GO ID | Cluster | P-value | Count (fused) | Count (Liu) | GO term |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4365 | 1 | 9.8 × 10−6 | 2/4 | 3/9 | Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (phosphorylating) activity |

| 16 620 | 1 | 5.0 × 10−4 | 2/4 | 3/9 | Oxidoreductase activity, acting on aldehyde/oxo donors, NAD/NADP acceptor |

| 51 287 | 1 | 1.1 × 10−3 | 2/4 | 3/9 | NAD or NADH binding |

| 6096 | 1 | 3.6 × 10−8 | 4/4 | 9/9 | Glycolysis |

| 19 320 | 1 | 3.3 × 10−7 | 4/4 | 9/9 | Hexose catabolic process |

| 46 164 | 1 | 7.4 × 10−7 | 4/4 | 9/9 | Alcohol catabolic process |

| 16 052 | 1 | 3.3 × 10−6 | 4/4 | 9/9 | Carbohydrate catabolic process |

| 6094 | 1 | 1.9 × 10−5 | 3/4 | 7/9 | Gluconeogenesis |

| 46 364 | 1 | 1.2 × 10−4 | 3/4 | 7/9 | Monosaccharide biosynthetic process |

| 19 752 | 1 | 5.7 × 10−4 | 4/4 | 8/9 | Carboxylic acid metabolic process |

| 42 180 | 1 | 6.4 × 10−4 | 4/4 | 8/9 | Cellular ketone metabolic process |

| 6082 | 1 | 6.8 × 10−4 | 4/4 | 8/9 | Organic acid metabolic process |

| 6800 | 1 | 1.2 × 10−3 | 2/4 | 3/9 | Oxygen and reactive oxygen species metabolic process |

| 1950 | 1 | 1.7 × 10−4 | 3/4 | 7/9 | Plasma membrane enriched fraction |

| 5626 | 1 | 2.1 × 10−3 | 3/4 | 7/9 | Insoluble fraction |

| 5811 | 1 | 3.3 × 10−3 | 2/4 | 3/9 | Lipid particle |

| 16 251 | 2 | 8.9 × 10−5 | 5/23 | 7/84 | General RNA polymerase II transcription factor activity |

| 30 528 | 2 | 1.6 × 10−3 | 6/23 | 26/84 | Transcription regulator activity |

| 31 202 | 2 | 1.6 × 10−3 | 4/23 | 22/84 | RNA splicing factor activity, transesterification mechanism |

| 3677 | 2 | 6.1 × 10−3 | 6/23 | 14/84 | DNA binding |

| 16 070 | 2 | 9.2 × 10−12 | 19/23 | 53/84 | RNA metabolic process |

| 10 467 | 2 | 1.1 × 10−7 | 22/23 | 78/84 | Gene expression |

| 398 | 2 | 1.5 × 10−4 | 6/23 | 24/84 | Nuclear mRNA splicing via spliceosome |

| 375 | 2 | 2.3 × 10−4 | 6/23 | 26/84 | RNA splicing, via transesterification reactions |

| 45 449 | 2 | 4.1 × 10−4 | 6/23 | 29/84 | Regulation of transcription |

| 80 090 | 2 | 7.5 × 10−4 | 13/23 | 40/84 | Regulation of primary metabolic process |

| 34 961 | 2 | 1.2 × 10−3 | 17/23 | 52/84 | Cellular biopolymer biosynthetic process |

| 9059 | 2 | 2.9 × 10−3 | 17/23 | 52/84 | Macromolecule biosynthetic process |

| 51 171 | 2 | 6.1 × 10−3 | 8/23 | 31/84 | Regulation of nitrogen compound metabolic process |

| 5634 | 2 | 2.6 × 10−8 | 22/23 | 15/84 | Nucleus |

| 32 991 | 2 | 7.9 × 10−5 | 18/23 | 24/84 | Macromolecular complex |

| 5681 | 2 | 1.3 × 10−4 | 5/23 | 19/84 | Spliceosomal complex |

| 43 227 | 2 | 3.9 × 10−4 | 23/23 | 83/84 | Membrane-bounded organelle |

| 3735 | 3 | 1.3 × 10−21 | 16/17 | 75/75 | Structural constituent of ribosome |

| 6412 | 3 | 3.4 × 10−10 | 13/17 | 49/75 | Translation |

| 43 284 | 3 | 4.4 × 10−8 | 17/17 | 75/75 | Biopolymer biosynthetic process |

| 34 645 | 3 | 1.2 × 10−7 | 17/17 | 75/75 | Cellular macromolecule biosynthetic process |

| 9058 | 3 | 4.2 × 10−6 | 17/17 | 49/75 | Biosynthetic process |

| 19 538 | 3 | 7.2 × 10−6 | 13/17 | 49/75 | Protein metabolic process |

| 34 960 | 3 | 4.8 × 10−4 | 17/17 | 75/75 | Cellular biopolymer metabolic process |

| 43 170 | 3 | 9.4 × 10−4 | 17/17 | 75/75 | Macromolecule metabolic process |

| 33 279 | 3 | 3.7 × 10−21 | 16/17 | 75/75 | Ribosomal subunit |

| 5829 | 3 | 1.1 × 10−13 | 16/17 | 74/75 | Cytosol |

| 22 627 | 3 | 3.2 × 10−11 | 8/17 | 33/75 | Cytosolic small ribosomal subunit |

| 43 232 | 3 | 8.3 × 10−10 | 16/17 | 75/75 | Intracellular non-membrane-bounded organelle |

| 22 625 | 3 | 1.1 × 10−9 | 8/17 | 41/75 | Cytosolic large ribosomal subunit |

| 32 991 | 3 | 1.5 × 10−6 | 16/17 | 75/75 | Macromolecular complex |

| 44 422 | 3 | 1.1 × 10−4 | 16/17 | 75/75 | Organelle part |

| 32 040 | 3 | 5.4 × 10−3 | 3/17 | 7/75 | Small-subunit processome |

| 51119 | 4 | 2.8 × 10−9 | 4/4 | 11/12 | Sugar transmembrane transporter activity |

| 5353 | 4 | 3.2 × 10−7 | 3/4 | 10/12 | Fructose transmembrane transporter activity |

| 15578 | 4 | 3.2 × 10−7 | 3/4 | 10/12 | Mannose transmembrane transporter activity |

| 5355 | 4 | 4.6 × 10−7 | 3/4 | 10/12 | Glucose transmembrane transporter activity |

| 22891 | 4 | 3.3 × 10−5 | 4/4 | 12/12 | Substrate-specific transmembrane transporter activity |

| 5215 | 4 | 1.2 × 10−4 | 4/4 | 12/12 | Transporter activity |

| 8645 | 4 | 1.2 × 10−9 | 4/4 | 9/12 | Hexose transport |

| 8643 | 4 | 9.7 × 10−9 | 4/4 | 11/12 | Carbohydrate transport |

| 55085 | 4 | 1.4 × 10−5 | 4/4 | 12/12 | Transmembrane transport |

| 51234 | 4 | 8.3 × 10−3 | 4/4 | 12/12 | Establishment of localization |

| 5886 | 4 | 5.0 × 10−3 | 3/4 | 11/12 | Plasma membrane |

Also shown is a comparison with the GO terms extracted by the Liu et al. method. There is a general trend that the fused clusters are more highly GO enriched. For example, we have highlighted in bold all the cases where a cluster from one method shows a percentage of GO enrichment (for a given term) that is at least 1.5 times higher than the other method. Note that only GO terms appearing only in both cases are shown.

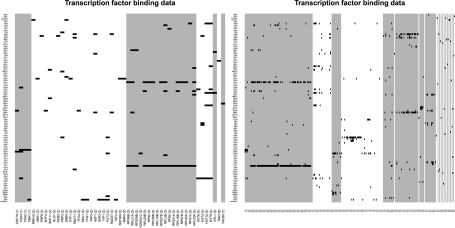

In Figure 4, we show the ChIP-chip data for the fused genes, sorted by cluster membership. The structure in this plot (horizontally aligned hits) shows certain transcription factors are contributing to the data integration and, like Segal et al. (2003b), we find that TMs are characterized by partly overlapping but distinct motif combinations.

Fig. 4.

The ChIP-chip data for the fused genes of the galactose utilization (left) and cell cycle (right) dataset analyses. The data have been sorted by the clustering partition. Black pixels indicate a transcription factor that binds to that gene. The different shades of grey show the clustering partition.

Table 3 shows some comparison analyses carried out using the Harbison et al. (2004) ChIP data in place of that of Lee et al. While the Harbison et al. data analysis finds more fused genes (72 versus 51), the BHI scores are comparable. We also run an analysis where we sample over w; in this case, the BHI scores are marginally worse and there are fewer fused genes (56) than for the w=0.5 case.

3.2 Cell cycle dataset

In Table 2, we give the BHI scores for different analyses of the cell cycle dataset. Again, our model (fused genes and w=0.5) gives the best results, although in this case the method of Liu et al. provides a slightly lower BHI score. In all cases, the data integration provides benefit over simply using gene expression data and the BHC algorithm (BHI = 0.285).

Table 2.

The BHI scores for the cell cycle dataset

| Similarity matrix | w | No. of genes | BHI (all) | BHI (bp) | BHI (mf) | BHI (cc) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fused genes | 0.5 | 266 | 0.33 ± 0.01 | 0.18 ± 0.02 | 0.17 ± 0.01 | 0.23 ± 0.01 |

| Fused genes | 1 | 1165 | 0.30 ± 0.01 | 0.09 ± 0.01 | 0.14 ± 0.01 | 0.20 ± 0.01 |

| Unfused (expression only) | 0 | 1165 | 0.28 ± 0.01 | 0.07 ± 0.01 | 0.14 ± 0.01 | 0.19 ± 0.01 |

| Unfused (expression only) | 0.5 | 898 | 0.31 ± 0.01 | 0.08 ± 0.01 | 0.16 ± 0.01 | 0.20 ± 0.01 |

| Unfused (ChIP chip only) | 0 | 1165 | 0.30 ± 0.01 | 0.05 ± 0.01 | 0.12 ± 0.02 | 0.24 ± 0.02 |

| Unfused (ChIP chip only) | 0.5 | 898 | 0.25 ± 0.03 | 0.06 ± 0.01 | 0.13 ± 0.03 | 0.21 ± 0.02 |

| Context-averaged (Liu et al.) | 0 | 1165 | 0.29 ± 0.01 | 0.09 ± 0.01 | 0.14 ± 0.01 | 0.20 ± 0.01 |

| Context-averaged | 0.5 | 1165 | 0.30 ± 0.01 | 0.08 ± 0.01 | 0.15 ± 0.01 | 0.20 ± 0.01 |

| Context-averaged | 1 | 1165 | 0.30 ± 0.01 | 0.09 ± 0.01 | 0.14 ± 0.01 | 0.20 ± 0.01 |

The fused genes are those with a posterior probability of being fused ≥0.5. All other genes are classed as unfused. Context-averaged similarity matrices are simply constructed by averaging the posterior similarity matrix over both contexts (i.e. datasets). This is the method used by Liu et al. For comparison, the result obtained using the BHC algorithm on just the gene expression data is 0.285.

In the Supplementary Material we show the posterior similarity matrix, sorted by cluster membership. The block-diagonal structure shows the core of each cluster clearly defined. In this figure, off-diagonal blocks may indicate one of two possibilities; it may mean that there is uncertainty in whether a set of genes should be assigned to one of the two clusters, or it may indicate a set of genes that should really belong simultaneously to two clusters. The two clusters in question (Clusters 3 and 4, counted from the left) do indeed share common GO annotations indicating metabolic function (Fig. 3). Cell cycle regulation is a complex interplay of many different external signals and intrinsic cell states (Bähler, 2005). The cell cycle is composed of at least four phases: S, synthesis phase wherein DNA is being replicated; G1, gap 1; M, mitosis where the yeast cell physically pulls chromosomes into the daughters and then separates; and G2, gap 2. The transitions between phases are critical checkpoints. There cell division is blocked by various conditions; for example, signals indicating there is DNA damage or incomplete DNA replication will block cells from going from S→G1. Thus, it would be expected that there may be multiple regulatory pathways, some of which likely overlap.

In Figure 3, we show a matrix of the significantly over-represented GO terms in each of the clusters we extract. As with the galactose utilization dataset, there is good block structure, although in this larger dataset there are some high-level GO terms that are significant in more than one cluster.

We identify 12 fused clusters in the data (excluding singletons). While the functional annotation of many of these correspond to those previously identified by Liu et al. (2007), there are some interesting differences. In addition to a cluster of genes involved in methionine and cysteine biosynthesis (Cluster 9), we identify a separate cluster for arginine and glutamine biosynthesis (Cluster 3). Cluster 1 comprises mainly ribosomal proteins, but also includes metabolic genes, which may be an indication of the importance of metabolic state in cell cycle progression. Interestingly, these include the same metabolic genes that comprise Cluster 1 in the galactose utilization dataset, suggesting that these genes represent a TM that is being co-regulated with ribosomal proteins in the cell cycle. This also highlights the value of perturbations (as used in the galactose utilization data) as a better experimental design to uncover underlying TMs than a study involving a natural biological process, such as the cell cycle. Cluster 7 contains several key genes associated with cell cycle regulation, as well as several genes involved with the M-phase, chromosome structure and repair. Cluster 11 contains several genes involved in the M→G2 phase transition.

4 DISCUSSION

Both gene expression and ChIP-chip data contain information about the biological functions of different genes, but it is non-trivial to combine them in a sensible way, both due to their noisy nature and also because co-expression and co-regulation may not necessarily be equivalent for all genes.

Our results show that by treating data fusion on a gene-by-gene basis, the model we present here is able to produce superior extraction of functionally coherent groups of genes from a combination of gene expression and ChIP-chip data. Our model also has special cases (given by w=0 and w=1) that produce data integration results that outperform the single dataset analyses (including a fast BHC clustering using expression data only). However, the model we present is both more flexible and outperforms these special cases in both the examples we have considered in this article.

The key innovation in our model is that the data integration is treated on a gene-by-gene basis. This allows crucial flexibility because we can distinguish between genes that are likely to be fused and those that are not. We can extract genes that are closely related on the basis of both datasets, while rejecting those that are not. It is these genes that are most likely to represent the underlying TMs.

Funding: This work was supported by the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EP/F027400/1, Life Sciences Interface).

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

Supplementary Material

APPENDIX A

A.1 THE ALGORITHM

We can perform inference for this model using MCMC sampling, by extending the sampler in section 5.1 of (Teh et al., 2006) in the following way.

Let Zji be the allocation of gene i in context j to a cluster. We initialize these randomly to one of K (≈ log(n)) initial clusters. Using the notation of Teh et al., we have the following equations.

| (A1) |

| (A2) |

For convenience, we define the following quantities.

| (A3) |

| (A4) |

| (A5) |

|

(A6) |

|

(A7) |

where for compactness of notation, we make the substitutions fji=Lj(xji|ϕjk) and fqi=Lq(xqi|ϕk) (and noting that the integrands are split over the two lines).

Updating w: if the w is given a beta prior distribution with parameters a and b then the full conditional distribution of w is beta with parameters a+∑ri and b+∑(1−ri). We choose a=b=2, encoding a weak preference for w=0.5.

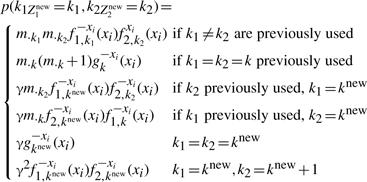

Updating r and t: the parameters ri and t are updated jointly. ri is the indicator as to whether or not gene i is fused. t is an identifier for a given mixture component, such that Zi=t means that gene i belongs to mixture component t. The full conditional distribution is

|

(A8) |

|

(A9) |

noting that is a given Z is not new, it has already been used previously, and where

|

(A10) |

|

(A11) |

|

(A12) |

|

(A13) |

| (A14) |

| (A15) |

|

(A16) |

| (A17) |

| (A18) |

If new values are to be drawn then they should be drawn in the following way. If ri=1 then

| (A19) |

If ri=0 and only Z1 is new

|

(A20) |

If ri=0 and only Z2 is new

| (A21) |

If ri=0 and Z1 and Z2 are new

|

(A22) |

where k1=knew, k2=knew+1 represents the creation of two new clusters of which one contains only x1i and the other only contains x2i.

Footnotes

REFERENCES

- Antoniak C. Mixtures of Dirichlet processes with applications to Bayesian nonparametric problems. Ann. Stat. 1974;2:1152–1174. [Google Scholar]

- Bähler J. Cell-cycle control of gene expression in budding and fission yeast. Ann. Rev. Genet. 2005;39:69–94. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.39.110304.095808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bar-Joseph Z, et al. Computational discovery of gene modules and regulatory networks. Nat. Biotechnol. 2003;21:1337–1342. doi: 10.1038/nbt890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho R, et al. A genome-wide transcriptional analysis of the mitotic cell cycle. Mol. cell. 1998;2:65–73. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80114-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahl D. Model-based clustering for expression data via a Dirichlet process mixture model. In: Do K.-A, et al., editors. Bayesian Inference for Gene Expression and Proteomics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2006. pp. 201–218. [Google Scholar]

- Datta S, Datta S. Methods for evaluating clustering algorithms for gene expression data using a reference set of functional classes. BMC Bioinformatics. 2006;7:397. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisen M. Cluster analysis and display of genome-wide expression. Proc. Natl Acad.Sci.USA. 1998;95:14863–14868. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.25.14863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falcon S, Gentleman R. Using GOstats to test gene lists for GO term association. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:257. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson T. A Bayesian analysis of some nonparametric problems. Ann. Stat. 1973;1:209–230. [Google Scholar]

- Fritsch A, Ickstadt K. Improved criteria for clustering based on the posterior similarity matrix. Bayesian Anal. 2009;4:367–392. [Google Scholar]

- Gasch A, et al. Genomic expression programs in the response of yeast cells to environmental changes. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2000;11:4241–4257. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.12.4241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerber G, et al. Automated discovery of functional generality of human gene expression programs. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2007;3:e148. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0030148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geweke J. Evaluating the accuracy of sampling-based approaches to calcualting posterior moments. In: Bernardo JM, et al., editors. Bayesian Statistics 4. New York: Oxford University Press; 1992. pp. 169–193. [Google Scholar]

- Harbison C, et al. Transcriptional regulatory code of a eukaryotic genome. Nature. 2004;431:99–104. doi: 10.1038/nature02800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ideker T, et al. Integrated genomic and proteomic analyses of a systematically perturbed metabolic network. Science. 2001;292:929–934. doi: 10.1126/science.292.5518.929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ihmels J, et al. Revealing modular organization in the yeast transcriptional network. Nat. Genet. 2002;31:370–377. doi: 10.1038/ng941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kundaje A, et al. Combining sequence and time series expression data to learn transcriptional modules. IEEE/ACM Trans. Comput. Biol. Bioinform. 2005;2:202. doi: 10.1109/TCBB.2005.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee T, et al. Transcriptional regulatory networks in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Science. 2002;298:799. doi: 10.1126/science.1075090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, et al. Context-specific infinite mixtures for clustering gene expression profiles across diverse microarray dataset. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:1737–1744. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, et al. Bayesian hierarchical model for transcriptional module discovery by jointly modeling gene expression and chip-chip data. BMC Bioinformatics. 2007;8:283. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-8-283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medvedovic M, Sivaganesan S. Bayesian infinite mixture model based clustering of gene expression profiles. Bioinformatics. 2002;18:1194–1206. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/18.9.1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medvedovic M, et al. Bayesian mixture model based clustering of replicated microarray data. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:1222–1232. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin ZS. Clustering microarray gene expression data using weighted Chinese restaurant process. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:1988–1997. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen C, et al. Modeling and visualizing uncertainty in gene expression clusters using Dirichlet process mixtures. IEEE/ACM Trans. Computat. Biol. Bioinform. 2009;6:615–628. doi: 10.1109/TCBB.2007.70269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen CE. The infinite Gaussian mixture model. In: Solla SA, et al., editors. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 12. Cambridge: MIT Press; 2000. pp. 554–560. [Google Scholar]

- Reid J, et al. Transcriptional programs: modelling higher order structure in transcriptional control. BMC Bioinformatics. 2009;10:218. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savage RS, et al. R/BHC: fast Bayesian hierarchical clustering for microarray data. BMC Bioinformatics. 2009;10:242. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segal E, et al. Genome-wide discovery of transcriptional modules from DNA sequence and gene expression. Bioinformatics. 2003a;19:273–282. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segal E, et al. Module networks: Discovering regulatory modules and their condition specific regulators from gene expression data. Nat. Genet. 2003b;34:166–176. doi: 10.1038/ng1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teh YW, Jordan MI. Hierarchical Bayesian nonparametric models with applications. In: Lid Hjort N, et al., editors. Bayesian Nonparametrics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2010. pp. 158–207. [Google Scholar]

- Teh YW, et al. Hierarchical Dirichlet processes. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 2006;101:1566–1581. [Google Scholar]

- Wild D, et al. A Bayesian approach to modeling uncertainty in gene expression clusters. 3rd International Conference on Systems Biology. 2002 [Google Scholar]

- Yao J, et al. Genome-scale cluster analysis of replicated microarrays using shrinkage correlation coefficient. BMC Bioinformatics. 2008;9:288. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeung K, et al. Clustering gene-expression data with repeated measurements. Genome Biol. 2003;4:R34. doi: 10.1186/gb-2003-4-5-r34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.