Abstract

Motivation: Next-generation sequencing technologies have enabled the sequencing of several human genomes in their entirety. However, the routine resequencing of complete genomes remains infeasible. The massive capacity of next-generation sequencers can be harnessed for sequencing specific genomic regions in hundreds to thousands of individuals. Sequencing-based association studies are currently limited by the low level of multiplexing offered by sequencing platforms. Pooled sequencing represents a cost-effective approach for studying rare variants in large populations. To utilize the power of DNA pooling, it is important to accurately identify sequence variants from pooled sequencing data. Detection of rare variants from pooled sequencing represents a different challenge than detection of variants from individual sequencing.

Results: We describe a novel statistical approach, CRISP [Comprehensive Read analysis for Identification of Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs) from Pooled sequencing] that is able to identify both rare and common variants by using two approaches: (i) comparing the distribution of allele counts across multiple pools using contingency tables and (ii) evaluating the probability of observing multiple non-reference base calls due to sequencing errors alone. Information about the distribution of reads between the forward and reverse strands and the size of the pools is also incorporated within this framework to filter out false variants. Validation of CRISP on two separate pooled sequencing datasets generated using the Illumina Genome Analyzer demonstrates that it can detect 80–85% of SNPs identified using individual sequencing while achieving a low false discovery rate (3–5%). Comparison with previous methods for pooled SNP detection demonstrates the significantly lower false positive and false negative rates for CRISP.

Availability: Implementation of this method is available at http://polymorphism.scripps.edu/∼vbansal/software/CRISP/

Contact: vbansal@scripps.edu

1 INTRODUCTION

Genome-wide association studies, using dense panels of common variants, have been enormously successful in identifying genomic loci for various diseases. However, the associated variants can explain only a small fraction of the heritability of most common traits (Maher, 2008). Rare variants or variants with a low minor allele frequency are not interrogated in genome-wide association studies and could explain a large fraction of the missing heritability of common diseases (Manolio et al., 2009). In comparison with common variants, the catalog of rare variants in the human genome is highly incomplete. Sequencing of a large number of individuals is required for finding rare sequence variants. With the availability of several next-generation sequencing platforms, the cost of DNA sequencing has dropped dramatically over the past few years and has made it feasible to sequence complete human genomes. Sequencing of the genomes of J. C. Venter (Levy et al., 2007) and James Watson (Wheeler et al., 2008) marked the beginning of the era of personal genomes. Next-generation sequencers such as the Illumina Genome Analyzer (GA) and ABI SOLiD have enabled the sequencing of several individual genomes in the past 2 years (Bentley et al., 2008; Kim et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2008).

The size of the human genome makes it infeasible to routinely sequence the complete genomes of hundreds of individuals. Nonetheless, it is feasible to sequence targeted regions of the human genome in hundreds to thousands of individuals in an individual laboratory (Stratton, 2008). A single run of the Illumina GA can be used to sequence an entire human genome to 2× coverage.1 Alternatively, it can be used to sequence 1 Mb of the human genome to 6000× coverage. Sequencing a large number of individuals simultaneously requires a high level of multiplexing. The Illumina GA allows multiplexed sequencing of eight samples per run (one on each lane) and also sequencing of up to 96 samples using DNA barcodes. To bypass the limited multiplexing and to reduce sample preparation and sequencing costs, an alternate approach is to pool genomic DNA from multiple individuals and sequence the pooled DNA samples (Sham et al., 2002). Pooled sequencing can be used to identify rare variants in targeted regions of the genome in large populations. Nejentsev et al. (2009) utilized pooled sequencing to resequence 10 candidate genes for type I diabetes and identified four rare variants that lowered disease risk.

Post-sequencing, the first objective is to identify all polymorphic sites. To overcome the high error rates of next-generation sequencing instruments and to ensure the sampling of both alleles at each variant site, individual genomes are typically sequenced to 20–30× depth of coverage. A number of tools have been developed to align millions of short reads with multiple errors to a reference sequence (Langmead et al., 2009; Li et al., 2008; Li and Durbin, 2009; Li,R et al., 2009; Rumble et al., 2009). Some of these tools also identify single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) by leveraging base-quality values across multiple reads covering the same position and have been successfully used to identify SNPs in individual genome sequencing projects (Bentley et al., 2008). Most of these SNP calling methods have been designed to identify SNPs from sequencing of individual genomes. The lack of methods for pooled SNP detection from next-generation sequencing data has motivated recent work on designing new methods for this purpose. Druley et al. (2009) demonstrated that it is feasible to identify rare variants with a minor allele frequency below the average sequencing error rate from pooled sequencing by using a highly accurate subset of the base calls for variant detection. Several studies have evaluated the ability to detect rare SNPs and estimate allele frequencies from pooled sequencing (Ingman and Gyllensten, 2009; Out et al., 2009). Novel approaches have been described for designing pooled sequencing experiments (Hajirasouliha et al., 2008; Prabhu and Pe'er, 2009) to achieve various objectives.

Detection of SNPs from pooled sequencing requires methods over and above those used to identify SNPs from sequencing of diploid or haploid genomes. For a diploid genome, the frequency of a variant allele is either 0.5 (heterozygous) or 1 (alternate homozygous). At a sequence coverage of ∼30×, one can expect to observe the variant allele sufficient number of times to distinguish it from sequencing errors that are unlikely to reach the same threshold as that of a variant allele (Bentley et al., 2008). In contrast, for pooled sequencing, the frequency of a variant allele is a function of the population allele frequency and the size of the pool. For a singleton heterozygous variant allele in a pool of 25 diploid individuals, one would expect 2% of the reads to carry the variant allele. However, with an average sequencing error rate of 1%, the same signal could be observed just due to an excess of sequencing errors. Increasing the sequence coverage can help to distinguish moderately frequent alleles from sequencing errors, but additional signals are needed to reliably detect rare alleles. To determine these signals, one requires some understanding of the characteristics of sequencing errors of next-generation sequencing platforms. In comparison with base calls that represent variant alleles, base calls that represent sequencing errors are more likely to cluster on one strand of the DNA (sequencing error rates on the forward and reverse strands are likely independent), cluster in a subset of positions in reads (toward the 3′-end of the read for Illumina reads) and have lower base-quality values. Further, sequencing errors that are a function of the local sequence context (the nucleotides flanking the base in the read) (Dohm et al., 2008) are expected to be systematically over or underrepresented across multiple DNA pools at the same position.

In this article, we demonstrate how these signals can be used to reliably identify SNPs from pooled sequencing data. We have developed a novel statistical approach that is able to identify rare variants by comparing the distribution of allele counts across multiple DNA pools using contingency tables. To detect common variants, we utilize individual base-quality values to compute the probability of observing multiple non-reference base calls due to sequencing errors alone. Additionally, we incorporate information about the distribution of reads on the forward and reverse strands and the size of the pools to filter out false variants.

To illustrate the power of our method, we utilize two independent pooled sequencing datasets generated using the Illumina GA: (i) 50 individuals sequenced in two pools of 25 each across a 200 kb region on chromosome 9 and (ii) 48 individuals sequenced in six equi-sized pools across two genes of the human genome spanning 188 kb of DNA sequence. For both datasets, we compare the pooled SNP calls to SNPs identified from individual sequencing of the same set of samples to estimate the sensitivity and specificity of CRISP. For one of the datasets, our method was able to identify 86% of the variants identified by individual sequencing with a false positive rate of 5–6%. By comparison with previously proposed methods for pooled SNP detection (Druley et al., 2009; Koboldt et al., 2009), we show that CRISP has significantly lower false positive and false negative rates.

2 METHODS

Our objective is to utilize sequenced reads from multiple DNA pools to identify SNPs. We assume that the reads for each pool have been aligned to the corresponding reference sequence. For each position, we consider the entire set of reads across all pools that cover this position. We utilize multiple signals to distinguish sequencing errors from real variants:

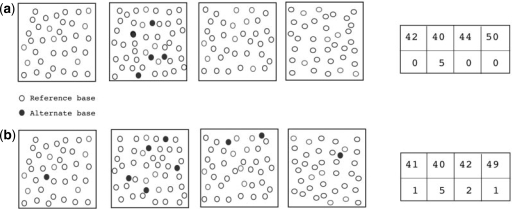

In the absence of a variant, the frequency of the reads with a nucleotide different from the reference base at a particular position should be similar across multiple pools. The intuition being that sequencing errors, especially those that depend upon the local sequence context, are likely to be shared across reads in multiple pools. In contrast, presence of a rare variant in a pool is expected to result in an excess of reads with the alternate allele as compared with the other pools. We use a contingency table approach to compute a P-value for the null hypothesis in the absence of a SNP (see Fig. 1 for an illustration of this idea).

In the absence of a variant, the number of reads with a nucleotide different from the reference base should not be significantly greater than that expected based on the sequencing error rate. Utilizing the individual base-quality values and the Chernoff bound (Chernoff, 1952), we compute an upper bound on the probability of observing s reads with an alternate allele out of n reads in a pool due to sequencing errors alone. The P-value corresponding to this bound is computed independently for the forward and reverse strand since a low P-value for one strand alone is indicative of strand-specific sequencing errors.

The minimum allele frequency of a variant allele in a pool with h haploid DNA sequences is

, assuming equal representation of the h haplotypes in the pool. In the presence of a variant, the number of reads supporting the variant allele in any pool should not be significantly lower than

, assuming equal representation of the h haplotypes in the pool. In the presence of a variant, the number of reads supporting the variant allele in any pool should not be significantly lower than  times the depth of coverage. We use a one-sided binomial test to compute a P-value for this deviation.

times the depth of coverage. We use a one-sided binomial test to compute a P-value for this deviation.

Fig. 1.

Illustration of how comparison of allele counts across multiple DNA pools can be used to distinguish rare variants from sequencing errors. (a) Four sequenced pools are represented as boxes with each base call shown as a circle. All five of the alternate base calls are present in a single pool. The P-value of the contingency table corresponding to four pools is 0.002 suggesting that the five base calls represent a rare SNP rather than sequencing errors. (b) Five of the nine alternate base calls are present in a single pool. The P-value of the corresponding contingency table is 0.24 indicating that the presence of five alternate base calls in a single pool is likely due to sequencing errors alone.

In the next few sections, we present the mathematical description of the methods used to compute P-values for the absence of a SNP and subsequently describe how these P-values can be combined together to distinguish SNPs from sequencing errors.

2.1 Modeling aligned sequence reads as a contingency table

In a resequencing study, a set of targeted regions are sequenced in a population of individuals. We consider a set of targeted regions of total length L nucleotides resequenced in N diploid individuals using k DNA pools with N/k individuals each to an average depth of coverage 2NC/k per pool. Here, C is the average coverage per haplotype in the pool. For simplicity, we assume that the number of individuals per pool is identical, however, this is not necessary.

Our objective is to identify positions in the sequenced region for which at least one of the 2N haplotypes carries a base different from the reference base. These positions correspond to what are commonly known as SNPs or more precisely, single nucleotide variants. Consider a position p in the sequenced region and let A represent the reference base at this position and B be the most frequent non-reference base across all pools. Let ri denote the observed number of aligned reads covering the position p for the i-th pool (1≤i≤k) of which ai represent the alternate allele B.2 Let e1, e2,…, ek represent the average sequencing error rates in the k pools. In the absence of a SNP, all reads with the alternate allele represent sequencing errors. Assuming that all sequencing error rates ei are approximately equal (a valid assumption if all pools are sequenced using the same sequencing platform), the reads with the alternate allele should be more or less randomly distributed across the k pools. Alternately, in the presence of a SNP, a large fraction of the alternate reads should cluster into a few pools. Under the null hypothesis, the fraction of reads with the alternate allele is the same across the k pools. This is also true for SNPs whose frequency is identical across the k pools. However, such SNPs are likely to be common SNPs and detectable using other methods.

The number of reads with the reference and alternate alleles at a particular position across the k pools can be modeled as a contingency table T0 with two rows and k columns with row sums: A = ∑iai and R−A = ∑iri−ai and column sums ri (1≤i≤k):

| Col 1 | Col 2 | …… | Col k | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Row 1 | r1 − a1 | r2 − a2 | …… | rk−ak | R − A |

| Row 2 | a1 | a2 | …… | ak | A |

| Total | r1 | r2 | …… | rk | R |

Furthermore, the probability of the observed read counts under the null hypothesis can be defined as the probability of the table T0:

| (1) |

The significance or the P-value associated with the observed table T0 is defined as the sum of all 2 × k contingency tables with identical row and column sums that have equal or lower probability than the observed table. Formally, we are interested in computing the sum:

where Γ represents the set of all 2 × k contingency tables with the same marginal sums as T0 and P(T) for any table T is defined by Equation 1.

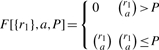

2.2 Computing significance of a 2 × k contingency table

The χ2 test is commonly used to estimate the significance of contingency tables. However, the P-values derived from the χ2 distribution are known to deviate from the true P-values when some of the entries in the contingency table are small. Indeed, many of the entries in the 2 × k contingency table (especially the ai values) are expected to be close to 0 or even 0. Therefore, it is preferable to compute the significance using an exact test. For k = 2, the number of tables in Γ is bounded by the row-sum A and the P-value can be computed exactly using the Fisher exact test for 2 × 2 tables. However, computing the significance of a 2 × k table for larger values of k requires significant computational effort since the number of tables that need to be examined grows exponentially with k. Mehta and Patel (1980) proposed a network algorithm to compute the P-value of a 2 × k table without enumerating all feasible tables. We provide a simple recursive formulation for computing the P-value of a 2 × k table that is similar to the approach of Mehta and Patel (1980). We define a function F that expresses the sum of probabilities of tables T with probability less than or equal to that of the table T0, i.e. the P-value of T0, as the sum of probabilities of multiple 2 × (k − 1) contingency tables:

where r′ = min(rk, A). The base case is defined as:

|

It is easy to see that  is equal to the P-value of the table T0. Therefore, the P-value can be computed exactly using a simple recursive algorithm. The running time of this algorithm is a function of both the number of columns k and the value A. For k = 2, the P-value can be computed exactly for all values of A. As k increases, the maximum value of A for which the P-value can be computed exactly decreases. For tables with large k and A, an alternate way to compute the P-value is by simulating many random contingency tables with the same marginal sums as T0 and counting the number of tables T′ with probability P(T′)≤P(T0). We have implemented a simple Monte Carlo scheme to estimate the significance of a 2 × k table:

is equal to the P-value of the table T0. Therefore, the P-value can be computed exactly using a simple recursive algorithm. The running time of this algorithm is a function of both the number of columns k and the value A. For k = 2, the P-value can be computed exactly for all values of A. As k increases, the maximum value of A for which the P-value can be computed exactly decreases. For tables with large k and A, an alternate way to compute the P-value is by simulating many random contingency tables with the same marginal sums as T0 and counting the number of tables T′ with probability P(T′)≤P(T0). We have implemented a simple Monte Carlo scheme to estimate the significance of a 2 × k table:

Monte Carlo method to estimate P-value

Initialize t=0

Initialize an array P of size R with P[i] = p for r1 +··· +rp−1≤i≤r1+···+rp (1≤i≤k)

For i=1,…, k, set ai = 0

- For i=1,…, N, do the following:

- Set

- For a = 1,…, A, do

- Randomly select an integer r in the interval [a, R]

- Set j = P[r] and swap the elements P[a] and P[r]

, aj = aj + 1

, aj = aj + 1

- If P(T′) ≤ P(T0): t = t + 1

- For any pool j chosen in step (2), set aj = 0

The estimated P-value is

Each iteration of the loop in Step 4 can be implemented in O(A) time. Therefore, the overall running time of the whole procedure is O(NA + R + k). For A ≪ R, the procedure is much faster than an alternate implementation with O(NR) running time. In practice, we use one of the two methods: the exact recursive algorithm and the Monte Carlo method to compute a P-value for each contingency table depending upon the values of k and A. For the Monte Carlo method, 104–105 permutations were used to compute the P-value.

2.3 Probability of multiple sequencing errors using quality values

The contingency table approach described in the previous section evaluates the significance of the distribution of the reads with the alternate allele across multiple pools. It utilizes information about the number of reads with the reference and alternate allele in each pool and does not use information about base-quality values. Base calls generated by next-generation sequencing instruments are accompanied by base-quality values that represent estimates of the accuracy of each base call. While these base-quality values are not as accurate as Phred scores for Sanger sequencing, they do contain useful information about the accuracy of individual base calls. For example, if the average sequencing error rate is 0.01, one can expect about 10 in 1000 base calls to be sequencing errors. If one observes 30 non-reference base calls at a particular position with 1000× coverage, it indicates the presence of a variant allele rather than sequencing errors. More formally, we can define the P-value for the null hypothesis that s alternate base calls at a position with n base calls all represent sequencing errors:

| (2) |

where Q1, Q2,…, Qn represent the quality values of the n base calls. Assuming independence between base calls, this probability can be computed using the distribution of the sum of n independent Bernoulli random variables with success probabilities p1, p2,…, pn where pi = 10−0.1×Qi. The probability of the sum X = X1 + X2 +···+Xn of n independent Bernoulli random variables deviating from its mean μ = ∑ipi can be bounded using the Chernoff bound (Chernoff, 1952):

where s = (1 + δ)μ. Using this equation, we can compute an upper bound on the P-value of observing s of n reads with an alternate alleles due to sequencing errors alone. This P-value is computed for each strand separately and by considering the base calls for each pool independently. This test complements the contingency table-based P-value since it tests for the over-abundance of alternate alleles within each pool beyond what is expected based on the sequencing error rate.

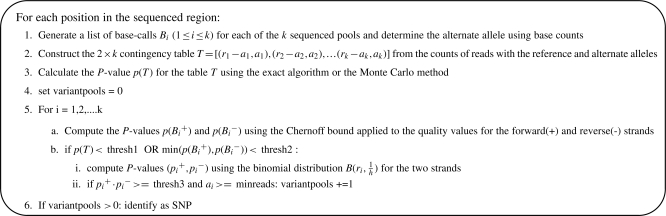

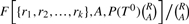

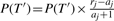

2.4 Calling SNPs from pooled sequence data using multiple statistics

The contingency table P-value represents the probability of the absence of a SNP at a particular position across multiple DNA pools. Positions for which the P-value was below a threshold (thresh1) were identified as potential SNPs. For the quality value-based P-values, we required the P-value for each strand to be below a threshold (thresh2) in at least one pool, for the position to be identified as a potential SNP. We required the quality value-based P-value to be below a threshold for both strands independently since a low P-value for one strand alone is indicative of strand-specific sequencing errors rather than the presence of a variant allele.

For each potential SNP, we further analyzed the reads within each pool and imposed additional filters to call the site as a SNP. For each pool, we evaluated if the fraction of alternate alleles was significantly lower than  , the minimum expected fraction in a pool with h haplotypes. Given a pool with s of n reads with the alternate allele, we used the binomial distribution to compute the probability of observing s or fewer successes in n trials with success probability

, the minimum expected fraction in a pool with h haplotypes. Given a pool with s of n reads with the alternate allele, we used the binomial distribution to compute the probability of observing s or fewer successes in n trials with success probability  . The probability was computed separately for the two strands. Pools for which the product of the probabilities for the forward and reverse strands was above a threshold (thresh3 = 0.01) were retained as SNPs. For each pool, we also required at least four reads with the alternate allele, at least one read with the alternate allele from each of the two strands and one or more reads with the alternate allele in the middle of the read (to avoid calling indels as SNPs). Positions for which one or more pools passed all filters were reported as the final set of SNPs. The full algorithm is described in Figure 2.

. The probability was computed separately for the two strands. Pools for which the product of the probabilities for the forward and reverse strands was above a threshold (thresh3 = 0.01) were retained as SNPs. For each pool, we also required at least four reads with the alternate allele, at least one read with the alternate allele from each of the two strands and one or more reads with the alternate allele in the middle of the read (to avoid calling indels as SNPs). Positions for which one or more pools passed all filters were reported as the final set of SNPs. The full algorithm is described in Figure 2.

Fig. 2.

Description of the algorithm CRISP for detection of SNPs using sequencing data from k DNA pools.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Pooled sequencing data

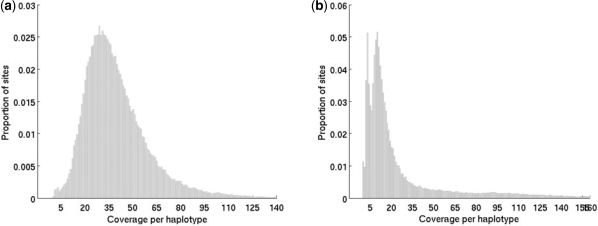

We assessed the performance of our method using two separate pooled sequencing datasets generated using the Illumina GA. The first of these datasets was generated from the sequencing of a 197 kb region on chromosome 9 of the human genome in 50 individuals using two pools with 25 individuals each (Bansal et al., 2010). The targeted region was amplified using multiple long-range polymerase chain reaction (LR-PCR) reactions in the 50 individuals and two pools were formed by equi-molar pooling of DNA from 25 individuals each. Each pool was sequenced using four lanes of the Illumina GA with 36 bp single ended reads. The average coverage of the two pools, based on the alignments, was ∼2080× (42× per haplotype) and 2500× (50× per haplotype), respectively (Fig. 3a). For this dataset, the 50 individuals were also sequenced individually using the Illumina GA to identify SNPs (O.Harismendy et al. unpublished data). This afforded us with the opportunity to compare the set of SNPs identified from the pooled sequencing with the set of SNPs determined from the individual sequencing and thereby obtain good estimates of the sensitivity and specificity of our method.

Fig. 3.

Empirical distribution of the sequence coverage per haplotype (one pool) in the two-pooled sequencing datasets: (a) 50 individuals in two pools and (b) 48 individuals in six pools.

The second pooled sequencing data that we utilized was obtained from the sequencing of two genes (188 kb of sequence) in 48 individuals using six pools with eight individuals each (Harismendy et al., unpublished). Each pool was sequenced using one lane of the Illumina GA using 36 bp reads. The average coverage per pool varied between 400–500× (25–30× per haplotype). However, there was some non-uniformity in the coverage from position to position resulting from the unequal pooling of the LR-PCR products (see Fig. 3b). Samples in each pool were indexed with barcodes before pooling. For the evaluation of our method, we ignored the barcode information and considered the reads from each lane as a single pool. The barcodes have previously been used to split the reads for each lane, create sequence files for each sample and call SNPs for each sample using the MAQ SNP caller (Harismendy et al., unpublished). This again enabled us to compare the SNP calls from the pooled data with the individual SNP calls.

3.2 Detection of SNPs from pooled sequencing datasets

The reads for each pool were aligned to the corresponding reference sequence (for the targeted regions) using the MAQ aligner (Li et al., 2008) (v0.7.1). For pooled SNP detection, we only considered reads with a MAQ mapping quality of 20 or more and with three or fewer mismatches to the reference sequence. We also filtered out base calls with a quality value below 17, i.e. base calls with an error probability >0.02. The algorithm CRISP (as described in Fig. 2) was applied to identify SNP sites for each of the two datasets. For the contingency table P-value, we chose a threshold of 10−4. At this threshold, the expected number of positions with a significant contingency table P-value across 2 × 105 positions is small. Further, additional filtering used to remove positions with low number of alternate alleles (Section 2.4) is likely to remove such false SNPs. For the quality score P-value, we chose a threshold of p = 1 − (1 − α)1/K = 10−7.3 with α = 0.01 and K = 2 × 105. This stringent threshold adjusted for testing of multiple positions and also accounted for the non-random correlation between sequencing errors at the same position which leads to over-inflated quality values.

For the chromosome 9 dataset, CRISP identified 665 SNPs across the two pools. Eight hundered and seventeen SNPs had previously been identified from the individual sequencing of the 50 samples in the two pools. Of the 665 pooled SNP calls, 627 were shared with the individual SNP calls, suggesting a false discovery rate of 5–6%. We further analyzed 190 SNPs that were not identified from the pooled sequencing data. Of these SNPs, 44 had low sequence coverage (<15× in one of the two pools). An additional 46 SNPs were specific to one of the 50 individuals indicating that this individual was poorly represented in the DNA pools. Ignoring the 46 SNPs specific to one individual and the 44 SNPs with low coverage, there were 727 SNPs called from the individual sequencing and CRISP was unable to identify 100 of these SNPs. Therefore, we can estimate a false negative rate of 13.7% for CRISP. Additional analysis showed that 75 of the 100 missed SNPs were singletons, i.e. called as SNPs in one sample each.

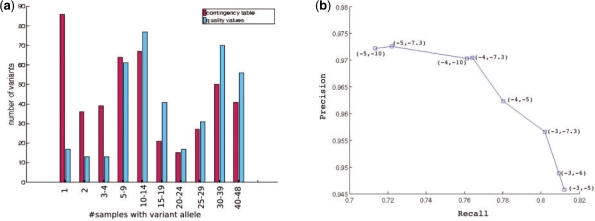

Similarly, CRISP called 541 SNPs across the six pools for the second dataset and 525 of these were shared with the 687 SNPs previously identified in the 48 samples. Therefore, we estimate that<3% (16/541) of the called variants are likely to be false. The false negative rate is higher likely due to the lower sequence coverage. Using this dataset, we contrasted the power of the contingency table approach and the quality values approach to detect SNPs with different allele frequencies (see Fig. 4a). For low frequency SNPs, the contingency table approach had greater power than the quality values-based approach that was able to identify common SNPs missed by the contingency table approach. This was not entirely unexpected, but demonstrated the ability of the contingency table approach to identify rare alleles and also illustrated the complementary nature of the two strategies.

Fig. 4.

(a) Comparison of SNPs identified from the second pooled sequencing dataset using two independent statistics: contingency table P-value and quality values-based P-value. Only SNPs that were also identified from the individual sequencing of the 48 samples are shown. (b) Precision–recall curve for SNPs identified by CRISP from the second pooled dataset using different thresholds for the two P-values: contingency table P-value and the quality values-based P-value. The P-value thresholds (log base 10) are shown for each point on the curve.

To evaluate the effect of changing the P-value thresholds on the true positive and false negative rates, we plotted a precision–recall curve for the second pooled dataset using different pairs of thresholds for the two P-values (Fig. 4b). As for any statistic, choosing a lower cutoff for either of the two P-values decreased the true positive rate (recall) while increasing the precision. However, reducing the thresholds below certain values (10−4 for the contingency table P-value and 10−10 for the quality values-based P-value) did not improve the precision further but reduced the true positive rate. More sophisticated strategies can be used for selecting the thresholds, e.g. by using a set of known SNPs to learn the optimum thresholds using the precision–recall curve.

3.3 Comparison of performance with previous methods

For comparison, we also applied two previously published methods, SNPseeker (Druley et al., 2009) and VarScan (Koboldt et al., 2009), to identify SNPs from the two-pooled sequencing datasets. SNPseeker was run with the default options (error model was generated using a phiX control lane and bases 3–12 were used for variant calling). For running VarScan, the reads were aligned using Bowtie (Langmead et al., 2009) and variants called using the easyrun option. For SNPseeker, we reduced the P-value cutoff to 0.001 from 0.05 to improve the specificity. Similarly for VarScan, we increased the –min-read2 parameter to 4 and –min-var-freq parameter to 1/(No. of haplotypes per pool) to reduce the number of false positives. We also utilized the default MAQ SNP caller (maq.pl easyrun -N haplotypes -E 0) to identify SNPs. For MAQ, we used a Q60 threshold for calling SNPs. All methods (except CRISP) were applied separately on each pool and the SNP calls merged across the pools for each dataset. Table 1 details the number of true positives and false positives for each of the two datasets using different methods.

Table 1.

Comparison of the number of false positive and false negative SNP calls using CRISP, SNPseeker, VarScan and MAQ (pooled) for the two datasets

| 50 samples in two pools |

48 samples in six pools |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Method | No. of SNPs | False positives | False negatives | No. of SNPs | False positives | False negatives |

| CRISP | 665 | 38 (5.6%) | 190/817 | 541 | 16 (3%) | 162/687 |

| SNPSeeker | 739 | 307 (41%) | 385/817 | 508 | 199 (39%) | 378/687 |

| VarScan | 1849 | 1244 (67%) | 212/817 | 715 | 234 (33%) | 206/687 |

| MAQ (pooled) | 367 | 279 (76%) | 729/817 | 948 | 681 (71%) | 420/687 |

From the table, it is clear that CRISP significantly outperforms all other methods. The power of SNPSeeker was likely reduced compared with other methods since it only uses a subset of base calls for variant detection. The specificity of each method could potentially be improved by increasing the respective thresholds used for calling SNPs or by giving more weight to SNPs called in more than one pool. However, the sensitivity for all methods at the default thresholds was lower than that for CRISP.

4 CONCLUSIONS

We have presented a novel approach that systematically combines two different statistical approaches to identify both rare and common SNPs from massively parallel sequencing of DNA pools using the Illumina GA. Detection of SNPs from pooled sequence data requires different strategies than those used to identify SNPs from individual genome sequencing. We have demonstrated that modeling of aligned reads across multiple pools using a contingency table can be used to identify rare SNPs present at frequencies comparable to the sequencing error rate. Comparison of allele counts across multiple pools is especially powerful to identify rare alleles. Most previous methods do not utilize information from multiple pools to identify variants. We have demonstrated the better performance of this method in comparison with several other existing methods for pooled SNP calling using two-pooled sequencing datasets with different depths of pooling generated using the Illumina GA platform.

In this article, we focused on detection of SNPs. Indels represent an important class of small-sequence variation that can be identified from short read sequence data. Our method, in particular the contingency table approach should be extendable for identifying indels from pooled sequencing. Previous papers have focused on the estimation of allele frequency from pooled sequencing data. We believe that accurate estimate of allele frequency is not difficult once SNPs have been identified reliably. Moreover, pooling imbalances are likely to influence the allele frequency estimates irrespective of the method used to estimate the frequency.

CRISP has been implemented in python and accepts read alignments in the generic SAM format (Li,H. et al., 2009). The method is compatible with any short read alignment program and potentially applicable to sequence data from sequencing platforms other than the Illumina GA. From the perspective of computational efficiency, the main bottleneck is computing the P-value of a large number of contingency tables. We have attempted to make this computation highly efficient. CRISP took 1 h to analyze the first dataset (with two pools) and 4 h to identify SNPs for the second dataset on a single CPU.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to thank Dr Nicholas Schork for supporting this work, members of SGM who generated the sequence data used in this paper and Dr. Vineet Bafna for suggesting an efficient scheme for simulating random contingency tables.

Funding: Scripps Translational Science Institute Clinical Translational Science Award (National Institutes of Health U54RR02504-01).

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

Footnotes

1Assuming a yield of ∼6 Gb per run.

2We ignore reads that have a base different from both A and B.

REFERENCES

- Bansal V, et al. Accurate detection and genotyping of SNPs utilizing population sequencing data. Genome Res. 2010;10:537–545. doi: 10.1101/gr.100040.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentley DR, et al. Accurate whole human genome sequencing using reversible terminator chemistry. Nature. 2008;456:53–59. doi: 10.1038/nature07517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chernoff H. A measure of asymptotic efficiency for tests of a hypothesis based on the sum of observations. Ann. Math. Stat. 1952;23:493–507. [Google Scholar]

- Dohm JC, et al. Substantial biases in ultra-short read data sets from high-throughput DNA sequencing. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:e105. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Druley TE, et al. Quantification of rare allelic variants from pooled genomic DNA. Nat. Methods. 2009;6:263–265. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajirasouliha I, et al. Optimal pooling for genome re-sequencing with ultra-high-throughput short-read technologies. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:32–40. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingman M, Gyllensten U. SNP frequency estimation using massively parallel sequencing of pooled DNA. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2009;17:383–386. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2008.182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JI, et al. A highly annotated whole-genome sequence of a Korean individual. Nature. 2009;460:1011–1015. doi: 10.1038/nature08211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koboldt DC, et al. VarScan: variant detection in massively parallel sequencing of individual and pooled samples. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2283–2285. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langmead B, et al. Ultrafast and memory-efficient alignment of short DNA sequences to the human genome. Genome Biol. 2009;10:R25. doi: 10.1186/gb-2009-10-3-r25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy S, et al. The diploid genome sequence of an individual human. PLoS Biol. 2007;5:e254. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, et al. Mapping short DNA sequencing reads and calling variants using mapping quality scores. Genome Res. 2008;18:1851–1858. doi: 10.1101/gr.078212.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1754–1760. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, et al. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2078–2079. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li R, et al. Soap2: an improved ultrafast tool for short read alignment. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1966–1967. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maher B. Personal genomes: the case of the missing heritability. Nature. 2008;456:18–21. doi: 10.1038/456018a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manolio TA, et al. Finding the missing heritability of complex diseases. Nature. 2009;461:747–753. doi: 10.1038/nature08494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta C, Patel N. A network algorithm for the exact treatment of the 2× k contingency table. Commun. Stat. Simul. Comput. 1980;9:649–664. [Google Scholar]

- Nejentsev S, et al. Rare variants of IFIH1, a gene implicated in antiviral responses, protect against type 1 diabetes. Science. 2009;324:387–389. doi: 10.1126/science.1167728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Out AA, et al. Deep sequencing to reveal new variants in pooled DNA samples. Hum. Mutat. 2009;30:1703–1712. doi: 10.1002/humu.21122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prabhu S, Pe'er I. Overlapping pools for high-throughput targeted resequencing. Genome Res. 2009;19:1254–1261. doi: 10.1101/gr.088559.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rumble SM, et al. SHRiMP: accurate mapping of short color-space reads. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2009;5:e1000386. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sham P, et al. DNA Pooling: a tool for large-scale association studies. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2002;3:862–871. doi: 10.1038/nrg930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stratton M. Genome resequencing and genetic variation. Nat. Biotechnol. 2008;26:65–66. doi: 10.1038/nbt0108-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, et al. The diploid genome sequence of an asian individual. Nature. 2008;456:60–65. doi: 10.1038/nature07484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler DA, et al. The complete genome of an individual by massively parallel DNA sequencing. Nature. 2008;452:872–876. doi: 10.1038/nature06884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]