Abstract

Context: In December 2005, in characterizing diabetes as an epidemic, the New York City Board of Health mandated the laboratory reporting of hemoglobin A1C laboratory test results. This mandate established the United States’ first population-based registry to track the level of blood sugar control in people with diabetes. But mandatory A1C reporting has provoked debate regarding the role of public health agencies in the control of noncommunicable diseases and, more specifically, both privacy and the doctor-patient relationship.

Methods: This article reviews the rationale for adopting the rule requiring the reporting of A1C test results, experience with its implementation, and criticisms raised in the context of the history of public health practice.

Findings: For many decades, public health agencies have used identifiable information collected through mandatory laboratory reporting to monitor the population's health and develop programs for the control of communicable and noncommunicable diseases. The registry program sends quarterly patient rosters stratified by A1C level to more than one thousand medical providers, and it also sends letters, on the provider's letterhead whenever possible, to patients at risk of diabetes complications (A1C level >9 percent), advising medical follow-up. The activities of the registry program are similar to those of programs for other reportable conditions and constitute a joint effort between a governmental public health agency and medical providers to improve patients’ health outcomes.

Conclusions: Mandatory reporting has proven successful in helping combat other major epidemics. New York City's A1C Registry activities combine both traditional and novel public health approaches to reduce the burden of an epidemic chronic disease, diabetes. Despite criticism that mandatory reporting compromises individuals’ right to privacy without clear benefit, the early feedback has been positive and suggests that the benefits will outweigh the potential harms. Further evaluation will provide additional information that other local health jurisdictions may use in designing their strategies to address chronic disease.

Keywords: Diabetes, disease registry, surveillance, privacy

In surveys conducted between 1994 and 2004, the proportion of New York City adults reporting having diabetes more than doubled, from 3.7 to 9.2 percent (New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene 2007, 2009b). Each year, New York City's adults with diabetes experience more than 20,000 diabetes-related hospitalizations, nearly 3,000 lower-extremity amputations, and 1,400 new cases of end-stage renal disease, with hospitalizations alone accounting for $481 million in medical costs (Kim, Berger, and Matte 2006). Diabetes is the fifth leading cause of death, and diabetes mortality rates are two to three times higher in blacks and Hispanics than in whites and two times higher in those living in low-income neighborhoods than in high-income neighborhoods (Kim, Berger, and Matte 2006; New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene 2008).

Controlling blood sugar (as measured by A1C levels), blood pressure, and LDL cholesterol can substantially reduce the risk of long-term complications of diabetes and decrease mortality (Adler et al. 2000; Davidson, Ansari, and Karlan 2007; Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Research Group 1993; Gaede et al. 2008; Stratton et al. 2000; UK Prospective Diabetes Study Group 1998). In New York City, as in the rest of the United States, control of these risk factors for complications is suboptimal. In a 2004 survey, less than 10 percent of New York City adults with diabetes had adequate control of three key predictors of mortality: blood sugar, blood pressure, and cholesterol. Furthermore, 22 percent—more than the city average—were smokers (Thorpe et al. 2009).

Faced with the increasing burden of diabetes and its complications in New York City's population, the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene reviewed both its existing disease control programs (e.g., tuberculosis, HIV infection, lead poisoning, hepatitis C infection) and its ongoing work in improving the quality of diabetes care to craft a strategy to address diabetes control. Features that the disease control programs have in common are mandatory reporting of test results, provision of test results to patients and/or providers, general education efforts, provision of treatment or resources to access care, and policy implementation.

In 2005, the department submitted a proposal to the New York City Board of Health that would require most laboratories to report to the department all A1C results for New York City residents (New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene 2005). Following a period of public comment, in late 2005 the board of health approved this proposal. In proposing a mandatory reporting system for A1C results, the department built on the experience of these existing disease control programs by establishing a disease surveillance system that would both track the condition in the population and directly support individuals who would stand to benefit from the program's efforts to control diabetes in New York City. It was also the first U.S. mandate requiring A1C results to be reported to a public health authority.

The decision to require mandatory reporting of A1C results has stirred controversy. Although the period of public comment attracted fairly modest attention, experts across various disciplines later published papers both supporting and opposing the measure (Banerji and Stewart 2006; Barnes, Brancati, and Gary 2007; Fairchild 2006; Fairchild and Alkon 2007; Fairchild, Bayer, and Colgrove 2007; Goldman et al. 2008b, 2008a; Krent et al. 2008; Mariner 2007; Monitoring Diabetes Treatment in New York City 2006; Steinbrook 2006). The appropriate role of public health and the use of traditional public health tools in the control of chronic disease were the principal issues raised in many of these papers, and this debate has become increasingly critical given the growing burden of chronic disease in the population (Frieden 2004).

This article, written by members of the department that implemented the program, presents the public health rationale for creating the A1C Registry, describes how registry data are collected and used, and considers the issues raised by critics, particularly the role of public health in chronic disease.

Public Health Rationale for the A1C Registry

Disease registries can improve outcomes in people with chronic conditions (Bodenheimer, Wagner, and Grumbach 2002a, 2002b; Gudbjörnsdottir et al. 2003; Kupersmith et al. 2007; Larsen, Cannon, and Towner 2003; Tsai et al. 2005). Registries provide a mechanism by which providers can identify individuals in greatest need of follow-up or referral and also monitor disease indicators in their patient population over time. In New York City, few health care providers have such systems in place. The department's position was that a population-based A1C registry could fill a critical gap in the health care system's infrastructure until such innovations as electronic medical records with a registry function were more widely adopted, enabling providers to monitor and improve diabetes care.

Features and Uses of the A1C Registry

The registry's information is used to monitor glycemic control over time in the population (e.g., surveillance activities) and to disseminate tools to support medical providers and their patients (see table 1). Laboratories that conduct A1C testing for New York City residents (regardless of the laboratory's location) and are already reporting electronically other laboratory test results to the department are subject to the mandate. Laboratories report test results to the department using a secure file transmission method. Although laboratories that provide incomplete data or fail to report may be fined or have their permits revoked under the city's health code, no such actions have yet been taken.

TABLE 1.

Features of the A1C Registry

| Feature | |

|---|---|

| Who reports? | Laboratories (within or outside New York City) with a New York State license and serving New York City residents that already report electronically via file upload to the department for other reportable conditions |

| What is reported? | Test records for individuals who have had an A1C test done at a mandated laboratory, within 24 hours of the result |

| What information is required? | • A1C test result |

| • Date of test | |

| • Name of testing facility | |

| • Name of ordering facility/provider and address | |

| • Name of person tested, his/her address and date of birth | |

| Who can receive information? | The treating medical provider(s) (defined as the individual provider and/or institution that ordered the last test) or the person who was the subject of the test |

| How do providers receive information? | • Individual providers receive a quarterly patient roster, ordered by A1C level, by mail. |

| • Facilities receive similar rosters for all providers linked to that facility. | |

| • Patients who opt out are not included in rosters. | |

| How do patients receive information? | • Letters are sent to patients 18 years and older who have A1C >9 percent or who are overdue for testing. |

| • Patients who opt out do not receive a letter. | |

| Can patients opt out? | • Patients can opt out of the interventions, including receiving letters or being on provider rosters, by contacting the department by phone, post, or online. |

| • Patients cannot opt out of the registry, as laboratory reporting is mandatory. |

Surveillance Activities

The department analyzes registry data to assess variations in testing patterns, health care utilization, and glycemic control by age, sex, geographic location (i.e., zip code or borough), and type of health care facility (e.g., hospital, federally qualified health center, solo practice). The general laboratory reporting rule governing the A1C mandate does not require reporting race and ethnicity, so data on these variables are incomplete. Longitudinal analyses will examine changes in patients’ level of glycemic control over several years for cohorts defined by year of entry into the registry.

Supporting Patient Care

The goals of the department's provider and patient tools are (1) to raise providers’ awareness regarding the level of glycemic control in their patient panels; (2) to enable providers to take action for those at highest risk; and (3) to inform and guide patients who are at risk for complications to return to care and discuss treatment with their providers.

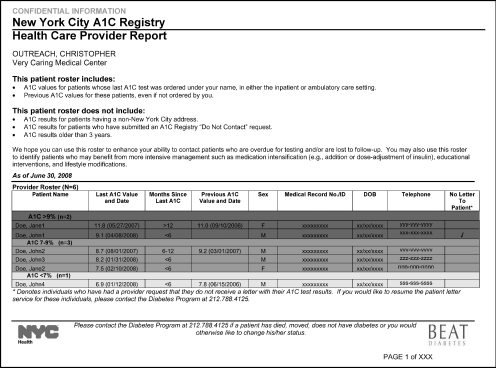

The department sends individual health care providers a quarterly report listing their patients’ two most recent A1C tests. The registry defines the person or institution that ordered the most recent test as the patient's treating medical provider, and thus the result of the previous A1C test is provided even if ordered by another provider. Patients in the registry are listed in order from highest A1C test result to lowest (figure 1), with those above 9 percent highlighted in red. This ranking enables the rapid identification of those patients most in need of additional support, such as making phone calls to return to care and reviewing charts to determine whether treatment for blood glucose, blood pressure, and/or cholesterol should be intensified or referred to specialists or care management. The registry reports include the entire patient panel for a given provider, regardless of insurance coverage. Some insurance plans provide similar A1C profiles for covered patients, but New York City providers typically care for patients covered by several health insurance plans.

Figure 1.

Sample Report to Providers Summarizing Their Patients’ A1C Results

Note: For a larger, color version, see http://www.nyc.gov/html/doh/downloads/pdf/diabetes/diabetes-provider-report.pdf.

The department also sends providers a facility-level report listing A1C results for all patients whose most recent test was ordered by that facility. These reports then can be used to initiate, maintain, and monitor institutional quality improvement activities.

The department does not plan to publish provider-level information, nor does it routinely share information with others outside the department regarding how any one health care facility is implementing the registry services.

The department sends a letter to patients eighteen years of age or older with elevated A1C values (above 9 percent), informing them of their most recent test result, explaining the risk of complications, and recommending that the patient schedule a return appointment. The letter, in both English and Spanish, also gives the patient a set of questions to ask the provider at the next visit (figure 2). A letter informing patients who are several months overdue for an A1C test will be initiated in the summer of 2009. This outreach service to patients is currently offered at no cost to medical providers, based on a written agreement authorizing the department to send the letters to patients on behalf of the facilities, using their letterhead.

Figure 2.

Sample Patient Letter, Sent on Provider Letterhead

Note: For a larger, color version, see http://www.nyc.gov/html/doh/downloads/pdf/diabetes/diabetes-patient-letter.pdf.

The department gives these facilities printed materials about the letter service, including the right to opt out, which can be displayed in patient care areas. Patients may refuse this service even before they receive a letter, by contacting the department by phone, post, or online using a web-based form (New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene 2009a). Those who opt out will not receive letters, and their results will not be listed on the provider or facility rosters. Because some individuals who might benefit from outreach may be excluded if their providers do not participate in the program, the department is also considering sending letters directly to patients whose last A1C was >9 percent and who have not had a subsequent test in twelve months and may no longer be in care.

Use of Personal Identifiers for Surveillance and Patient Care Activities

Personal identifiers are essential to enable both accurate surveillance and actions to improve the care of individual patients. When conducting chronic disease surveillance, repeat tests for a given individual need to be linked to each other so that estimates of the number of unique individuals are accurate. Without a unique patient identifier, personal identifiers are the only information for linking subsequent tests for a particular individual and removing duplicate results. Furthermore, the patient rosters contain information needed by providers to arrange a follow-up visit or to review a chart to determine whether the patients are receiving optimal medical therapy for blood sugar, blood pressure, or lipid control. Without identifiers, this would not be possible. Similarly, the patient letter could not be generated or mailed without identifiers, as it is addressed to the individual. As written in the health code, however, the department cannot release this personal, identifiable information to anyone other than the subject of the test (e.g., through the patient letter) or to his or her treating medical provider(s) (e.g., through the rosters).

Practical Experiences and Challenges

Surveillance Activities

Laboratory information systems typically are designed to record and store laboratory test information, to report a test result for a particular patient to the ordering provider, and to submit billing information. Creating a registry for surveillance or patient follow-up from such information has posed several challenges. First, some information still must be manually reviewed and updated to ensure that reports and letters are accurate and are being delivered to the correct person. For example, a facility telephone number that appears in the registry may be that of a hospital operator, not a patient appointment line; or a facility address may be a courier delivery location rather than a postal mailing address. In addition, linkages between providers and practices and between providers and patients need to be confirmed (e.g., a provider may have administrative ties to a hospital for admitting and referral but be in private practice; a patient may have a test ordered by a provider who was substituting for his or her regular provider).

A second challenge is data quality. Missing or incorrect information and nonstandardized data entry affect outreach activities (e.g., individuals without an address cannot receive a letter). Similar challenges have been confronted in the electronic laboratory reporting of communicable diseases (Nguyen et al. 2007).

A third challenge is determining who within the registry has diabetes as the health code does not require a diagnosis code to be submitted with test results. Because many providers use A1C as a screening test for diabetes, A1C test results reported to the registry include both people whose diabetes is well controlled and those who do not have diabetes. In June 2009, an expert group appointed by the American Diabetes Association, the International Diabetes Federation, and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes recommended adopting A1C ≥6.5 percent as a screening and diagnostic criterion for diabetes (International Expert Committee 2009). If adopted, the department can use an A1C value ≥6.5 percent to distinguish between those who have diabetes and those who do not.

By the spring of 2009, thirty-six of the thirty-seven originally mandated laboratories were regularly submitting data to the department, accounting for 97 percent of the expected reporting volume. The registry had received 4.2 million test results for nearly 1.8 million individuals, 42 percent of whom had had more than one test since January 15, 2006, including those who have since died or moved out of New York City.

Supporting Patient Care: The South Bronx Pilot

In anticipation of a South Bronx pilot project beginning in 2007, the department contacted 3,600 physicians across New York City (including the Bronx) in 2006 through its Public Health Detailing program (New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene 2009c) to inform them about the registry, its purpose, and the ability of patients to opt out of receiving letters. Shortly thereafter, in the fall of 2006, the department collaborated with several medical practices to develop tools to communicate A1C information to providers and patients, using the Vermont Diabetes Information System as a model (MacLean, Littenberg, and Gagnon 2006; MacLean et al. 2004).

In June 2007, after finalizing the provider and patient tools, the registry staff began soliciting the participation of sixty-nine Bronx health care facilities serving about 100,000 patients in the registry, including many residents of the South Bronx, a community with a high prevalence of diabetes. By the end of 2008, the department had sent 3,000 reports to more than 1,000 providers covering more than 73,000 patients, including nearly 9,000 high-risk individuals with A1C values above 9 percent. In the fall of 2008, the department began mailing letters to patients whose A1C values were above 9 percent. Over the course of a year, an estimated 12,000 letters will be sent to nearly 10,000 individuals. Providers caring for 83 percent of patients with elevated A1C tests in the department's South Bronx pilot have requested the patient letter service. This positive response suggests that this service is indeed filling a gap and that providers welcome this assistance in supporting patient care.

To promote the self-management of diabetes, the department offers providers additional tools to distribute to patients, such as glucose meters and strips, blood pressure–monitoring cuffs for home use, and free one-year memberships to Department of Parks and Recreation centers.

Evaluation

Feedback from providers will help the department learn how rosters are being used, what additional supports are needed, and whether the reports prompted change in the management of diabetes. A telephone survey is being conducted to determine whether the patient letter raises awareness of the risk of complications and if it prompts action by the patient (e.g., by scheduling an appointment, taking the letter to the next visit to the doctor). Preliminary results from the telephone survey conducted two to six months after patients were sent a letter found that approximately half the survey respondents remembered receiving the letter, 69 percent of whom reported that they would take the letter to their next visit, and 17 percent of whom said it prompted them to make an appointment. A health impact assessment will include monitoring A1C levels over time in the group of individuals cared for by facilities receiving reports and authorizing letters, as compared with those at facilities that have not received any registry services. Any knowledge gained will be used to adjust the intervention model and to target the future expansion of registry feedback and resources to high-need populations.

Controversies: Privacy, Confidentiality, Public Health, and Clinical Care

The rule to mandate the reporting of A1C results and the creation of the registry has been controversial. Criticism has included arguments that the department had exceeded its authority, invading the privacy of persons with diabetes, potentially harming those whose names were in the registry, and interfering with otherwise positive relationships between providers and patients (Goldman et al. 2008b, 2008a; Krent et al. 2008; Mariner 2007). For example, Goldman and colleagues offered a blunt summary that “our community will be better served if Frieden [the health commissioner who requested A1C reporting] stays out of the examining room” (Goldman et al. 2008a). Conversely, some commentators praised the registry as a major step forward in addressing a modern epidemic using traditional public health tools. Fairchild commented, “The measure is [also] groundbreaking in that public health is responding to what it has taken to be a moral duty to meet the needs of, and indeed empower populations that have been inadequately served by the existing health care system” (Fairchild 2006, p. 175).

Privacy and the Right to Be Left Alone

One argument was that for chronic disease, “the general goal of improving public health is too vague and malleable a concept to justify depriving individuals of their personal privacy. A far more precise and principled concept of public health threat is necessary to justify involuntary reporting” (Mariner 2007, p. 123). Even though diabetes is not contagious, it threatens the longevity and quality of life of nearly one in eight adults in New York City (Thorpe et al. 2009). In the department's view, this warrants an urgent public health response, and its decision to initiate mandatory reporting for A1C was built on its experience with using confidential health information to improve the population's health. Whether tracking and preventing the spread of infectious disease, screening for chronic illness, providing primary care to the underserved, visiting newborns in their homes to help them stay healthy, providing immunizations, or controlling lead poisoning, public health workers in New York City and elsewhere have long directly contacted people with specific exposures or conditions at identifiable addresses and maintained confidential records on these individuals. Birth records, for example, were used in New York City more than a century ago to identify households for home visits to new mothers, a time-honored public health service that New York City resumed in 2003.

Privacy advocates have raised concerns because results will appear in the registry whether or not an individual wishes to have them reported; only intervention services can be declined. Requiring that individual consent be obtained for A1C reporting—or other disease reporting—poses several problems from a public health perspective. First, incomplete reporting for A1C would compromise the data analyses that are used to assess the burden of disease, evaluate the impact of interventions, and responsibly allocate government resources. For example, if reporting and intervention implementation focus on certain population subsets, the effectiveness of interventions may not hold true for the broader population. Second, while universal mandatory reporting may include people who do not want their results reported or to receive registry services, a significant proportion of people who would want to be part of the registry and would benefit from its services might not be offered the opportunity for inclusion because of varying practices in obtaining consent unrelated to patients’ preferences. This tension between potential individual harm and population benefit is a common theme in public health. In this case, the department and the board of health concluded that this program's potential benefit and reach outweigh the potential harm to individuals. Last, requiring consent for reporting could set a hazardous precedent for other notifiable disease reporting, severely hindering the control of communicable disease outbreaks and the detection of environmental exposures.

Confidentiality and Data Security

Whenever sensitive personal information is held by an organization, there are legitimate concerns about its intentional or inadvertent release. Critics have raised the specter of less beneficent government uses of data acquired about people with diabetes through mandatory reporting, such as limits to health insurance eligibility or reimbursement (Krent et al. 2008). Others have argued that electronic databases can be breached, potentially resulting in an unauthorized release of confidential data.

Several steps have been taken to minimize such dangers. The rule passed by the New York City Board of Health specifically states that A1C results may be released by the department only to individual patients or their treating medical providers. Even with the patients’ written consent, information cannot be sent directly to insurance companies or other entities. This policy is more restrictive than that for other notifiable diseases, for which data may be shared when the department judges that an overriding public health benefit is served by disclosure (e.g., to inform a worksite of exposure to meningitis or tuberculosis, for which prophylaxis is available). To ensure that confidentiality is maintained, the department complies with the New York State Public Health Law and the New York City Health Code, which are more restrictive than the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act. Department staff authorized to work with the registry data are required to follow strict policies and procedures pertaining to the handling of the data, which are based on the department's best practices (Myers et al. 2008). In the event there is a breach of confidential information, the department is legally obligated under local law to communicate the breach to the affected individuals.

Public Health and Chronic Disease

Some critics have raised fundamental questions about the appropriate role of public health agencies in managing chronic disease beyond such traditional activities as public education, voluntary screening, and identification of high-risk groups. Two commentators noted that A1C reporting presaged a more aggressive approach by public health officials (Goldman et al. 2008b; Mariner 2007).

Attention to chronic disease has grown and evolved as the burden of disease has shifted from communicable diseases to noncommunicable diseases (Frieden 2004). Mandatory public health reporting now encompasses many noncommunicable conditions, such as birth defects, cancer, occupational diseases, lead poisoning, tests for other heavy metals, and Alzheimer's disease (Birkhead and Maylahn 2000). As outlined by the Institute of Medicine, assessing the community's health through the collection and analysis of data is an expected role for government in ensuring the population's health (Institute of Medicine 1988). The required reporting of A1C test results to monitor glycemic control and identify those individuals at the highest risk of diabetes morbidity and mortality continues in this tradition.

Control of Childhood Lead Poisoning: An Instructive Historical Precedent

While acknowledging the novelty of its A1C mandate, the department views the new rule as firmly within public health tradition. The use of mandatory laboratory reporting in managing childhood lead poisoning is similar to the A1C mandate and offers an interesting comparison of public health action and response. New York State mandated the reporting of blood-lead levels in 1993. Like diabetes, and in contrast to other mandated reporting requirements, lead poisoning is a noncommunicable disease and does not spread from person to person. Both disproportionately affect poor and minority communities and have the environment as a major contributing cause: lead in dust from gasoline and paint for lead poisoning and an “obesigenic” environment for type 2 diabetes, characterized by communities with an overabundance of high-calorie foods and a lack of access to fruits and vegetables or to physical activity resources (Auchincloss et al. 2008; Brownell and Horgen 2004; Morland and Filomena 2007; Sallis and Glanz 2009).

The reporting requirements and outreach activities related to the control of lead poisoning are similar to the registry program. By law, clinical laboratories must report all blood-lead levels for children, for whom elevated lead levels pose the greatest health threat, to the department's Lead Poisoning Prevention Program (LPPP). Because the LPPP receives all lead levels, whether or not elevated, it can determine the proportion of elevated tests and track citywide and community-based rates of elevated blood-lead levels. When the department receives an elevated result (for which the threshold has fallen over time), the program contacts the family and the medical provider to coordinate the child's management, provides treatment protocols, and arranges environmental assessments. Currently, the program follows affected children until their lead levels fall to below 10 mcg per deciliter, with such tracking facilitated by the reports of all blood-lead levels. As in the case of A1C test results, the department receives the laboratories’ results whether or not the patient or family wants them to be released, and contacts them without prior consent. Arguably, outreach during follow-up for an elevated blood-lead level is more intrusive than outreach to people with elevated A1C levels, as it includes home visits and multiple tests over time, and subsequent regulatory action may complicate tenant-landlord relations.

Despite these similarities, the public's reactions to these two mandated laboratory reporting requirements have differed. Attention to lead poisoning as a public health issue began during the period of social reform in the 1960s and 1970s. Environmental health advocates regarded lead poisoning as a disease of urban decay and government neglect (Berney 1993). According to this view, lead poisoning was a symptom of the confluence of poverty, poor housing stock, and racial discrimination. Children with lead poisoning were seen as innocent victims harmed by society and thus deserving of government assistance. Public health authorities typically were accused of inaction in identifying lead poisoning and ensuring its treatment. In contrast to diabetes, personal responsibility figured little in the effort to eradicate lead poisoning. Mothers were not blamed for “permitting” their children to ingest dust or paint chips. Instead, deteriorated housing stock, rather than individual behavior, was at fault. In the 1960s, lead-control advocates demanded the government's involvement to ensure treatment and prevent future harm through remediation of the environment. There was little question whether the government had the authority to assist children who suffered from lead poisoning; rather, the common view was that government had both the authority and the obligation to do so. This is evidenced by New York State law requiring that all children be tested for lead poisoning at ages one and two.

In contrast, type 2 diabetes, which typically strikes the adult population, has been perceived as a disease for which individuals are largely responsible through their personal behavior—eating too many calories, exercising too little—and, failing that, a disease managed by medical experts. According to this framework, people with diabetes are viewed as irresponsible, and thus identifying them might be stigmatizing. This line of thinking may explain the fear expressed by Goldman and colleagues that “a pilot intervention in the South Bronx could racialize diabetes and drive away from care the groups most in need of treatment and services” (Goldman et al. 2008b, p. 809). But the department views people with diabetes as no more blameworthy than children poisoned by lead and sees both as equally deserving of active public health intervention. While Goldman and colleagues raise an important point that targeting disadvantaged groups may raise issues of stigma and shame, the solution is a broader discussion of the ways that these populations are made more vulnerable to obesity and diabetes. The department believes that it would be unacceptable not to prioritize those populations subject to a disproportionate share of the disease burden and that an equitable public health response demands that more resources be directed to these groups (Frieden 2008).

In tracking A1C levels, the department is fulfilling its obligation to promote good diabetes care, just as it is meeting its responsibility to treat lead poisoning. As in the case of lead poisoning, other activities to reduce exposure to a disease-causing environment are crucial as well. Programs and policies to increase access to healthy foods and physical activity, which will help avert obesity and improve diabetes management, figure prominently in the department's efforts. The department sees the A1C test mandate as firmly within the tradition of public health surveillance for disease control, one in which the need for social protection is balanced against the need for individual privacy.

Clinical Care: Interference or Support of the Doctor-Patient Relationship?

Some critics have suggested that rather than helping providers identify and contact patients with poorly controlled diabetes, the department should try to improve access to care or give clinicians and patients more support for diabetes education and self-management (Goldman et al. 2008b; Mariner 2007). Mandatory reporting has often provoked controversy in the physician community (Birkhead and Maylahn 2000; Fairchild, Bayer, and Colgrove 2007). For example, tuberculosis reporting, mandated in New York City in 1897 and unquestioned today, was resisted by the medical profession with arguments that echo those now being raised about A1C reporting (Fairchild, Bayer, and Colgrove 2007; Frieden, Lerner, and Rutherford 2000). Physicians contended that public health doctors wished to usurp medical authority over patient care and that patients both lost privacy and stood to benefit little in management (antibiotics for effective tuberculosis treatment did not arrive for fifty more years). Medical societies complained publicly of “government paternalism,” language also used to criticize the A1C registry a century later (Fairchild, Bayer, and Colgrove 2007).

In New York City, few health care providers have clinical information systems that allow them to view their diabetes patient panels stratified by A1C level or send notices to patients who have elevated A1C levels or are overdue for testing, encouraging them to return for care. The registry addresses this gap, offering resources to medical providers—a patient roster and letters to patients—that are otherwise not available and without which it can be difficult to provide optimal patient care. Rather than policing diabetes or using A1C data to penalize people with poorly controlled diabetes and castigate their providers, the department acts as a partner to providers with an intervention that bolsters, not undercuts, the doctor-patient relationship. The high rate of acceptance by health care facilities for the registry patient letter service demonstrates the perceived value of the registry services to health care providers.

Although registries have been identified as a key tool in chronic disease management, the department recognizes that a more comprehensive set of changes is needed to prevent diabetes and improve disease outcomes. In addition to efforts to promote physical activity and a healthier food environment (Frieden et al. 2008; New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene 2009d, 2009e; Silver and Bassett 2008), the department has undertaken a series of interventions to improve clinical care. To make sure that best practice standards are widely disseminated, the department offers provider education through a published series entitled “City Health Information,” which includes guidelines for managing diabetes (Berger, Silver, and Frieden 2005), as well as conditions such as high blood pressure, high cholesterol, and smoking. These guidelines are sent to every physician and nurse practitioner, as well as many other health care providers in New York City. The department also has conducted direct in-office visits, called Public Health Detailing (Larson et al. 2006; New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene 2009c), on the management of diabetes, obesity, high blood pressure, high cholesterol, and smoking, for thousands of New York City's primary care providers and staff. The department also maintains a publicly accessible library of patient education and self-management materials for use in clinics.

The department's Primary Care Information Project complements the registry's work through the promotion of a public health–oriented electronic health record (Frieden and Mostashari 2008). The goal is to implement an electronic health record with built-in decision support for key diseases like diabetes and hypertension in the practices of 2,500 health care providers. Expanded implementation and adoption will take several years, but if all providers used such integrated systems, there would be less need for the A1C registry, although as a citywide registry, it would still offer the advantage of assembling all reported A1C results for monitoring overall trends in the city over time, regardless of place of care.

New York City's efforts to provide access to medical care for diabetes extend beyond the department. The city has an extensive network of voluntary safety net medical providers. It also directly funds and delivers care through the New York City Health and Hospitals Corporation (HHC). HHC is a $5.4-billion public benefit corporation and the largest municipal hospital and health care system in the United States, with eleven acute care hospitals, six large diagnostic and treatment centers, and eighty community clinics serving nearly 50,000 patients with diabetes (Health and Hospitals Corporation 2009). Clearly, preventing diabetes and improving outcomes requires a multipronged effort for which the registry is but one important activity.

Conclusion

Mandatory disease reporting and accompanying public health interventions have helped alter the trajectory of major epidemics, balancing public interest and personal privacy. In our view, the department would be remiss in its obligation to the public if it did not attempt to improve the care of people with diabetes. Our experience in implementing the registry shows that it is feasible to use the existing electronic laboratory–reporting infrastructure to create a registry of patients with diabetes and to follow their levels of blood sugar control over time. It is too soon to determine whether the New York City A1C Registry will improve outcomes for people with diabetes, but the early feedback from the South Bronx pilot has been positive. A similar measure to mandate A1C reporting has since been implemented on a pilot basis by the San Antonio Metropolitan Health District in Texas (San Antonio Metropolitan Health District 2008), which serves a population with high rates of diabetes and its complications.

Resistance to New York City's public health approach to diabetes control may result at least in part from the continued attribution of the current epidemic to individual genetic susceptibility and personal lifestyle choices, neither of which invokes a sense of urgency or validates public health response. Yet diabetes threatens to reduce the life expectancy of today's young people, after years of steady gains. In the department's view, this fact calls for a vigorous response, including enhanced disease surveillance, outreach to those at risk, and reversal of the epidemic's underlying environmental causes. Building on the past experience of other disease control programs, the ability to track patients’ control of their blood sugar over time, together with provider and patient tools, could improve diabetes care and reduce its rising toll of complications and premature death.

Acknowledgments

For insightful comments on drafts, we are grateful to Thomas Farley and James Hadler. Jessica Leighton provided useful background and references on lead reporting. Angela Merges and Leslie Korenda provided registry and implementation statistics. Hadi Makki provided informatics expertise in both the initial proposal for and the development of the registry.

References

- Adler AI, Stratton IM, Neil HA, Yudkin JS, Matthews DR, Cull CA, Wright AD, Turner RC, Holman RR. Association of Systolic Blood Pressure with Macrovascular and Microvascular Complications of Type 2 Diabetes (UKPDS 36): Prospective Observational Study. British Medical Journal. 2000;321(7258):412–19. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7258.412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auchincloss AH, Diez Roux AV, Brown DG, Erdmann CA, Bertoni AG. Neighborhood Resources for Physical Activity and Healthy Foods and Their Association with Insulin Resistance. Epidemiology. 2008;19(1):146–57. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e31815c480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerji MA, Stewart RB. A Public Health Approach to the Diabetes Epidemic: New York City's Diabetes Registry. Current Diabetes Reports. 2006;6(3):169–71. doi: 10.1007/s11892-006-0029-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes CG, Brancati FL, Gary TL. Mandatory Reporting of Noncommunicable Diseases: The Example of the New York City A1C Registry (NYCAR) American Medical Association Journal of Ethics. 2007;9(12):827–31. doi: 10.1001/virtualmentor.2007.9.12.pfor2-0712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger DK, Silver LD, Frieden TR. Diabetes Prevention and Management. City Health Information. 2005;24(1):1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Berney B. Round and Round It Goes: The Epidemiology of Childhood Lead Poisoning, 1950–1990. The Milbank Quarterly. 1993;71(1):3–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birkhead GS, Maylahn CM. State and Local Public Health Surveillance. In: Teutsch SM, Churchill RE, editors. Principles and Practice of Public Health Surveillance. New York: Oxford University Press; 2000. pp. 253–86. [Google Scholar]

- Bodenheimer T, Wagner EH, Grumbach K. Improving Primary Care for Patients with Chronic Illness. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2002a;288(14):1775–79. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.14.1775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodenheimer T, Wagner EH, Grumbach K. Improving Primary Care for Patients with Chronic Illness: The Chronic Care Model, Part 2. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2002b;288(15):1909–14. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.15.1909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownell KD, Horgen KB. Food Fight: The Inside Story of the Food Industry, America's Obesity Crisis, and What We Can Do about It. New York: McGraw-Hill/Contemporary Books; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson MB, Ansari A, Karlan VJ. Effect of a Nurse Directed Disease Management Program on Urgent Care/Emergency Room Visits and Hospitalizations in a Minority Population. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(2):224–27. doi: 10.2337/dc06-2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Research Group. The Effect of Intensive Treatment of Diabetes on the Development and Progression of Long-Term Complications in Insulin-Dependent Diabetes Mellitus. New England Journal of Medicine. 1993;329(14):977–86. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199309303291401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairchild AL. Public Health: Diabetes and Disease Surveillance. Science. 2006;313(5784):175–76. doi: 10.1126/science.1127610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairchild AL, Alkon A. Back to the Future? Diabetes, HIV, and the Boundaries of Public Health. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law. 2007;32(4):561–93. doi: 10.1215/03616878-2007-017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairchild AL, Bayer R, Colgrove J, Wolf D. Searching Eyes: Privacy, the State, and Disease Surveillance in America. Berkeley: University of California Press/New York: Milbank Memorial Fund; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Frieden TR. Asleep at the Switch: Local Public Health and Chronic Disease. American Journal of Public Health. 2004;94(12):2059–61. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.12.2059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frieden TR. New York City's Diabetes Reporting System Helps Patients and Physicians [letter to the editor] American Journal of Public Health. 2008;98(9):1543–44. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.142026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frieden TR, Bassett MT, Thorpe LE, Farley TA. Public Health in New York City, 2002–2007: Confronting Epidemics in the Modern Era. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2008;37(5):966–77. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyn108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frieden TR, Lerner BH, Rutherford BR. Lessons from the 1800s: Tuberculosis in the New Millennium. The Lancet. 2000;355(9209):1088–92. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02048-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frieden TR, Mostashari F. Health Care as if Health Mattered. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2008;299(8):950–52. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.8.950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaede P, Lund-Andersen H, Parving H, Pedersen O. Effect of a Multifactorial Intervention on Mortality in Type 2 Diabetes. New England Journal of Medicine. 2008;358(6):580–91. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0706245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman J, Kinnear S, Chung J, Rothman DJ. Goldman et al. American Journal of Public Health. 2008a;98(9):1544. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.121152. Respond. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman J, Kinnear S, Chung J, Rothman DJ. New York City's Initiatives on Diabetes and HIV/AIDS: Implications for Patient Care, Public Health and Medical Professionalism. American Journal of Public Health. 2008b;98(5):807–13. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.121152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gudbjörnsdottir S, Cederholm J, Nilsson PM, Eliasson B for the Steering Committee of Swedish National Diabetes Register. The National Diabetes Register in Sweden: An Implementation of the St. Vincent Declaration for Quality Improvement in Diabetes Care. Diabetes Care. 2003;26(4):1270–76. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.4.1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Health and Hospitals Corporation (HHC) HHC in Focus: Understanding Our Quality and Safety Performance. 2009. Available at http://www.nyc.gov/html/hhc/infocus/html/chronic/diabetes.shtmlaccessed May 22, 2009.

- Institute of Medicine. The Future of Public Health. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- International Expert Committee. International Expert Committee Report on the Role of the A1C Assay in the Diagnosis of Diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(7):1–8. doi: 10.2337/dc09-9033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim M, Berger DK, Matte TD. Diabetes in New York City: Public Health Burden and Disparities. New York: New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene; 2006. Available at http://www.nyc.gov/html/doh/downloads/pdf/epi/diabetes_chart_book.pdfaccessed July 6, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Krent HJ, Gingo N, Napp M, Moran R, Neal M, Paulas M, Sarna P, Suma S. Whose Business Is Your Pancreas? Potential Privacy Problems in New York City's Mandatory Diabetes Registry. Annals of Health Law. 2008;17(1):1–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kupersmith J, Francis J, Kerr E, Krein S, Pogach L, Kolodner RM, Perlin JB. Advancing Evidence-Based Care for Diabetes: Lessons from the Veterans Health Administration. Health Affairs. 2007;26(2):w156–68. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.2.w156. Millwood. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen DL, Cannon W, Towner S. Longitudinal Assessment of a Diabetes Care Management System in an Integrated Health Network. Journal of Managed Care Pharmacy. 2003;9(6):552–58. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2003.9.6.552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson K, Levy J, Rome MG, Matte TD, Silver LD, Frieden TR. Public Health Detailing: A Strategy to Improve the Delivery of Clinical Preventive Services in New York City. Public Health Reports. 2006;121(3):228–34. doi: 10.1177/003335490612100302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLean CD, Littenberg B, Gagnon M. Diabetes Decision Support: Initial Experience with the Vermont Diabetes Information System. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96(4):593–95. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.065391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLean CD, Littenberg B, Gagnon M, Reardon M, Turner PD, Jordan C. The Vermont Diabetes Information System (VDIS): Study Design and Subject Recruitment for a Cluster Randomized Trial of a Diabetes Registry in a Statewide Sample of Primary Care Practices. Clinical Trials. 2004;1(6):532–44. doi: 10.1191/1740774504cn051oa. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mariner WK. Medicine and Public Health: Crossing Legal Boundaries. Journal of Health Care Law & Policy. 2007;10(1):121–51. [Google Scholar]

- Monitoring Diabetes Treatment in New York City. The Lancet. 2006;367(9506):183. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68007-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morland K, Filomena S. Disparities in the Availability of Fruits and Vegetables between Racially Segregated Urban Environments. Public Health Nutrition. 2007;10(12):1481–89. doi: 10.1017/S1368980007000079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers J, Frieden TR, Bherwani KM, Henning KJ. Ethics in Public Health Research: Privacy and Public Health at Risk: Public Health Confidentiality in the Digital Age. American Journal of Public Health. 2008;98(5):793–801. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.107706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. Notice of Adoption to Amend Article 13 of the New York City Health Code. 2005. Available at http://www.nyc.gov/html/doh/downloads/pdf/public/notice-adoption-a1c.pdfaccessed May 22, 2009.

- Kim M, Berger DK, Matte TD, editors. New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance (BRFSS) Data, as Referenced in Diabetes in New York City: Public Health Burden and Disparities. New York: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. Summary of Vital Statistics 2007: The City of New York. Bureau of Vital Statistics. 2008. Available at http://www.nyc.gov/html/doh/downloads/pdf/vs/2007sum.pdfaccessed May 11, 2009.

- New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. Diabetes Prevention and Control Program—The New York City A1C Registry. 2009a. Available at http://www.nyc.gov/html/doh/html/diabetes/diabetes-nycar.shtmlaccessed May 22, 2009.

- New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. Epiquery: NYC Interactive Health Data System. 2009b. Available at http://www.nyc.gov/html/doh/html/epi/epiquery.shtmlaccessed May 22, 2009.

- New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. Public Health Detailing Program. 2009c. Available at http://home2.nyc.gov/html/doh/html/csi/csi-detailing.shtmlaccessed May 22, 2009.

- New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. Shape Up New York. 2009d. Available at http://www.nyc.gov/html/doh/html/cdp/cdp_pan_programs_comm.shtmlaccessed May 22, 2009.

- New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. SPARK! (Sport, Play, and Active Recreation for Kids!) 2009e. Available at http://www.nyc.gov/html/doh/html/cdp/cdp-spark.shtmlaccessed May 22, 2009.

- Nguyen TQ, Thorpe LE, Makki HA, Mostashari F. Benefits and Barriers to Electronic Laboratory Results Reporting for Notifiable Diseases: The New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene Experience. American Journal of Public Health. 2007;97(suppl. 1):S142–45. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.098996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sallis JF, Glanz K. Physical Activity and Food Environments: Solutions to the Obesity Epidemic. The Milbank Quarterly. 2009;87(1):123–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2009.00550.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- San Antonio Metropolitan Health District (Metro Health) State and City Officials Join Metro Health to Highlight Nation's Second Public Health Diabetes Registry. 2008. Available at http://www.sanantonio.gov/health/nr08DiabetesRegistryNC.htmlaccessed May 22, 2009.

- Silver L, Bassett MT. Food Safety for the 21st Century. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2008;300(8):957–59. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.8.957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinbrook R. Facing the Diabetes Epidemic—Mandatory Reporting of Glycosylated Hemoglobin Values in New York City. New England Journal of Medicine. 2006;354(6):545–48. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp068008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stratton IM, Adler AI, Neil HA, Matthews DR, Manley SE, Cull CA, Hadden D, Turner RC, Holman RR. Association of Glycaemia with Macrovascular and Microvascular Complications of Type 2 Diabetes (UKPDS 35): Prospective Observational Study. British Medical Journal. 2000;321(7258):405–12. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7258.405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorpe LE, Upadhyay UD, Chamany S, Garg R, Mandel-Ricci J, Kellerman S, Berger DK, Frieden TR, Gwynn C. Prevalence and Control of Diabetes and Impaired Fasting Glucose in New York City. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(1):57–62. doi: 10.2337/dc08-0727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai AC, Morton SC, Mangione CM, Keeler EB. A Meta-Analysis of Interventions to Improve Care for Chronic Illnesses. American Journal of Managed Care. 2005;11(8):478–88. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group. Intensive Blood-Glucose Control with Sulphonylureas or Insulin Compared with Conventional Treatment and Risk of Complications in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes (UKPDS 33) The Lancet. 1998;352(9131):837–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]