Abstract

Importance of the field

In fibrosing diseases, scar tissue begins to replace normal tissue, causing tissue dysfunction. For instance, in lung fibrosis, foci of what resembles scar tissue form in the lungs, impeding the ability of patients to breath. These conditions represent a significant source of morbidity and mortality. More than 150,000 people in the US have some form of fibrotic lung disease, and the five-year mortality rate for these diseases can be as high as 80%. Despite this large unmet medical need, there are no FDA-approved therapies. Although our understanding of the causes and the biology of fibrosing diseases remains relatively poor, we have made impressive advances in identifying the major cell populations and many biochemical mediators that can drive this process. As a result, novel therapeutics are being developed based upon these discoveries.

Areas covered in this review

This review examines the experimental therapies currently under investigation as of late 2009 for a major class of lung fibrosis called idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF).

What the reader will gain

The reader will gain an overview of current experimental therapies for IPF.

Take home message

With the recent approval of Pirfenidone in Japan for use in IPF, and a rich pipeline of experimental therapies in various stages of clinical development, the future looks bright for new treatment options.

Keywords: Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, lung, fibrosis, fibroblast, fibrocyte, epithelial-mesenchymal transition

1. Introduction

Mammals have evolved a robust and rapid ability to form scar tissue in response to injury in order to contain the extent of damage. For instance, large wounds stimulate multiple sources of cells to produce granulation tissue in order to fill in the void. In addition to the proliferation of fibroblasts at the exposed surface of a wound, circulating monocytes can enter the wound and differentiate into fibroblast-like cells called fibrocytes [1-5]. Pericytes surrounding the microvasculature in and adjacent to the injury are rapidly stimulated to differentiate in fibroblast-like cells [6, 7]. Finally, epithelial cells have also been described to differentiate into fibroblast-like cells in vitro and may participate in wound repair in a process termed epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition [8, 9]. Having multiple sources of fibroblast-like cells then speeds the formation of the scar tissue and the closing of the wound. Unfortunately, having a strong and apparently hair-trigger capacity to respond to injury using multiple cell types has its drawbacks when they inappropriately form scar tissue.

Fibrosing diseases such as congestive heart failure, end stage kidney disease, and pulmonary fibrosis involve the inappropriate formation of scar tissue in an internal organ, and are associated with an estimated 45% of all deaths in the US [10]. There are at least 62 different fibrosing diseases, and there is no FDA-approved therapy [10]. In these diseases, insults to the tissue, such as ischemia in the heart or liver or particulate matter or toxins in the lungs, as well as unknown stimuli, initiate an apparently unnecessary scarring response. Fibroblast-like cells and extracellular matrix proteins such as collagen then begin to replace the normal tissue in an organ, leading to organ failure and death [10, 11].

In the lung, fibrotic diseases include idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) sarcoidosis and scleroderma with interstitial lung disease (SSc w/ILD). In addition, chronic severe asthma involves a fibrosis surrounding the airways, which tends then restrict the airways [12]. These conditions have a significant prevalence in the US compared to other serious medical conditions, and high mortality rates (Table 1). For example, 80% of IPF patients die within 5 years of diagnosis [13], and as with other fibrosing diseases, there are currently no FDA-approved anti-fibrotic therapeutics to treat this pathology. Even oxygen therapy fails to improve outcome [14].

Table 1. Prevalence and 5 year mortality rates among fibrotic pulmonary diseases.

| Disease | Prevalence in the US | 5 year mortality rate |

|---|---|---|

| Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis | 130,000 | 80% |

|

Scleroderma with Interstitial Lung

Disease |

36,000 | 60% |

| Severe Chronic Allergic Asthma | 440,000 | 50% |

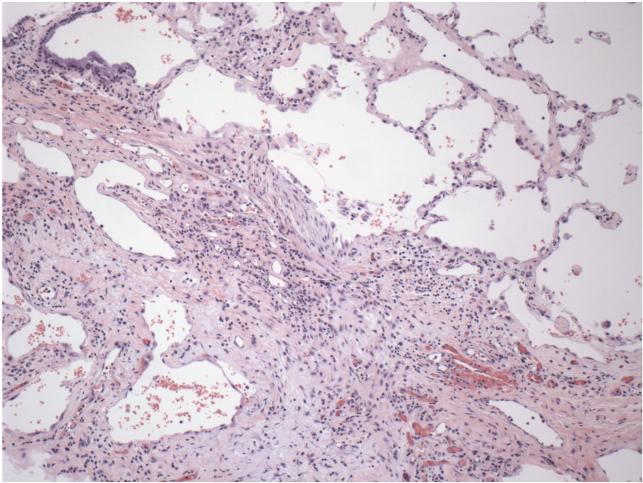

In this review, we will discuss the current state of development of therapies for IPF. Patients typically first notice that they are getting shortness of breath when they exercise. Since many conditions can cause shortness of breath, determining that a patient has IPF is somewhat difficult. Clinical criteria and radiological examination using high-resolution computed tomography can be used for the diagnosis [15]. A lung biopsy showing foci of fibroblast-like cells and collagen can be used for atypical cases, as well as for confirmation of the diagnosis (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Section of a lung from a patient with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis.

The section was stained with hematoxylin and eosin. A region of relatively normal lung is at upper right; the main mass of tissue in the center and lower left is fibrotic scar tissue that has replaced normal lung tissue. Figure is courtesy of Dr. Erica Herzog, Yale University School of Medicine, Internal Medicine - Pulmonary and Critical Care Division.

A commonly-used animal model for pulmonary fibrosis is treatment of mice or rats with bleomycin [16]. Although the model does not completely mimic human pulmonary fibrosis (for instance the bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis resolves with time), one advantage of the model is that it is relatively rapid; fibrosis appears in the lungs 7-14 days after treatment with bleomycin. For clinical studies, two key measurements are generally used. The first is mortality, and the second is lung function. The latter can be measured using either spirometry, where the patient takes a deep breath and exhales into a machine that measures airflow rate and volume as a function of time, or diffusing capacity, where the patient inhales a breath of air containing a known amount of tracer carbon monoxide, holds their breath for 10 seconds, and then exhales, and the amount of carbon monoxide remaining in the exhaled air is measured; this then measures the ability of the lung to exchange a gas from the air to the blood.

A puzzling aspect of IPF is that rather than a single origin, such as in a tumor, multiple foci of scar tissue generally appear throughout the lungs and new foci appear with the progression of the disease [17]. Possibly because of the significant differences between the physiology of normal lung cells and the physiology of the fibrotic scar tissue, there are changes in the levels of many different markers in the lungs of IPF patients [18]. Although it is unclear if a change in the levels of a protein or other factor are associated with the cause of the fibrosis or are a secondary effect, a number of potential mediators/biomarkers of disease are currently being investigated [19, 20].

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis does not appear to involve classical inflammation such as occurs in rheumatic diseases like rheumatoid arthritis, and formal clinical trials or general clinical impressions and experience indicate that broad spectrum anti-inflammatory drugs, immunosuppressants, and immunomodulators such as corticosteroids, azathioprine, cyclophosphamide, prednisone, colchicines, and interferon γ-1b have little effect on disease progression in the majority of patients with IPF [21] [22] [14, 23] [24]. However, it is important to note that these results do not imply that immune cells play no role in the progression of disease. They only indicate that non-specific therapeutics do not appear to appropriately modulate the pathology of the disease. For example, monocyte-derived populations and their derived products have been strongly associated with both fibrosis progression and resolution, including in the lung [11, 25].

2. Therapeutics in Development

Based upon our current understanding of the key molecular events in fibrosis, and the poor response of IPF patients to a variety of existing drugs, several groups are trying new experimental therapeutics for the treatment of IPF (Table 2).

Table 2. Anti-fibrotics in development for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis.

| Company | Compound | Mechanism of action |

Route | Status of project |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intermune; Shionogi |

Pirfenidone | Unknown, reduces growth factors/ cytokines |

Oral | Approved in Japan; Submitted in US and Europe |

| Gilead | Ambrisentan | Endothelin antagonist | Oral | Phase III |

| Actelion | Macitentan | Endothelin antagonist | Oral | Phase III |

| Zambon, NIH | N-Acetylcysteine | NFkB activation inhibitor; antioxidant |

Oral | Phase III |

| UCLA (Wyeth) | Minocycline hydrochloride |

Parp-1 inhibitor | Oral | Phase III |

| Pfizer | Sildenafil (Revatio) | PDE5 inhibitor | Oral | Phase III |

| Celgene | Thalidomide (Thalomid) |

unknown, reduces collagen production |

Oral | Phase III |

| Novartis | Imatinib mesylate (Gleevec) |

Tyrosine kinase inhibitor |

Oral | Phase II |

| Wyeth | Etanercept (Enbrel) | soluble TNFα receptor | Subcut. | Phase II |

| Cornerstone Therapeutics/ Skyepharma |

Zileuton (Zyflo) | Leukotriene synthesis inhibitor; 5-LO inhibitor |

Oral | Phase II |

| Adeona/Pipex Therapeutics |

Tetrathiomolybdate (Coprexa) |

copper chelator | Oral | Phase II |

| Boehringer Ingelheim |

BIBF-1120 (Vargatef) |

VEGFR, FGFR, PDGFR Inhibitor |

Oral | Phase II |

| Centocor | CNTO-888 | Anti-CCL-2 mAb | IV | Phase II |

| INSERM | Octreotide | Somatostatin analog | IM | Phase II |

| Genzyme | GC-1008 | anti-TGF-β human monoclonal antibody |

IV | Phase I |

| FibroGen | FG-3019 | anti-CTGF human monoclonal antibody |

IV | Phase I |

| Promedior | PRM-151 | rhSAP, monocyte inhibitor |

IV | Phase I |

See text for details. Under Route, Subcut. indicates subcutaneous injection, IV indicates intravenous injection, and IM indicates intramuscular injection.

Pirfenidone

Pirfenidone is a small molecule drug administered orally, whose mechanism of action is currently unknown, and is under investigation for use in IPF by InterMune in the US (www.intermune.com) and by Shinogi in Japan (www.shionogi.co.jp/index_e.html). Pirfenidone inhibits collagen synthesis, down regulates the production of multiple cytokines, and blocks fibroblast proliferation and stimulation in response to cytokines in cell culture and in preclinical disease models. Pirfenidone has demonstrated activity in several experimental fibrotic conditions, including preclinical models of lung, kidney and liver fibrosis [26-41]. Pirfenidone is the only anti-fibrotic drug currently under investigation for the treatment of IPF to have successfully completed Phase 3 clinical testing. However, the results in the US studies were somewhat contradictory. Pirfenidone has been studied in multiple Phase 2 and three pivotal Phase 3 clinical trials for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) conducted by InterMune in the US and EU and by Shionogi in Japan. Shionogi sought and was granted regulatory approval in Japan in 2008 based upon a single initial Phase 3 study measuring changes in Forced Vital Capacity (FVC). Intermune has conducted two additional Phase 3 CAPACITY studies in the US and EU; however the results from the two studies were mixed. The primary endpoint of change in FVC at week 72 was not met in CAPACITY 1 (p=0.501), but was met with statistical significance in CAPACITY 2 (p=0.001), along with the secondary endpoints of categorical change in FVC and progression-free survival. Based upon these combined Phase 3 results, InterMune submitted an NDA for Pirfenidone to the US FDA in November of 2009.

Endothelin receptor antagonists (Bosentan, Ambrisentan, Macitentan)

Endothelin receptor antagonists have demonstrated anti-fibrotic activity in preclinical models of pulmonary fibrosis due to their ability to block fibroblast contraction of collagen fibers and ability to reduce fibroblast activation [42-44]. Bosentan is a small molecule dual endothelin receptor antagonist administered orally. Bosentan was previously approved by the FDA for use in the treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension as Tracleer™. An initial Phase 2 study of Bosentan in IPF patients (the BUILD-1 study) did not meet its primary endpoint of change from baseline up to month 12 in exercise capacity, and Bosentan also failed to show efficacy in a similar BUILD-2 study in scleroderma/ ILD patients. A Phase 3 study investigating the drug for efficacy in a selected subgroup of IPF patients with biopsy-proven IPF and little radiographic honeycombing also recently failed. Phase III trials of the endothelin receptor antagonists Ambrisentan (Gilead Sciences) and Macitentan (Actelion Pharmaceuticals) are currently underway.

N-Acetylcysteine (Fluimucil™)

N-Acetylcysteine (NAC), also known as Fluimucil™, is an amino acid supplement classified as a natural product which is administered orally. NAC was investigated for use in IPF by the Zambon Group, SA (www.clinicaltrials.gov). NAC increases levels of the anti-oxidant glutathione [45], which can protect tissues from oxidant induced damage, a potential side effect of the common use of azathioprine in IPF patients. A single Phase 3 study of NAC with prednisone and azathioprine compared to prednisone and azathioprine in IPF patients did meet its primary endpoint of vital lung capacity and single-breath carbon monoxide diffusing capacity (Dlco) [46]. At one year, the decline in vital capacity was significantly less severe in those receiving NAC compared with those given placebo (relative difference: 9%, p<0.02). Dlco also deteriorated less in those given NAC (relative difference: 24%, p=0.003). The NIH IPF net is currently conducting a three-arm Phase III trial (PANTHER-IPF) of NAC compared to a combination of NAC, azathioprine, and prednusone, or placebo.

Minocycline hydrochloride

Minocycline hydrochloride is a broad spectrum tetracycline antibiotic administered orally, which is being studied in an investigator-initiated Phase 3 clinical study of IPF patients (www.clinicaltrials.gov). In addition to its antimicrobial properties, minocyline has also demonstrated anti-inflammatory and anti-angiogenic effects in preclinical models and clinical studies [47]. Although this trial initiated in 2005, no results have been reported.

Sildenafil (Revatio™)

Sildenafil in a small molecule phosphodiesterase 5 (PDE5) inhibitor administered orally and is under investigation in IPF by Pfizer (www.pfizer.com). Sildenafil, although better known as the active ingredient in Viagra™ and approved for use in erectile disfunction, is also approved under the trade name Revatio™ for the treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH). Recent data have suggested that many patients with IPF have PAH [48], and PAH is associated with poor survival. An initial Phase 1/2 clinical trial demonstrated that Sildenafil could improve exercise tolerance in IPF patients with PAH [49]. A second small Phase 2 study by independent investigators was recently reported which did not show a significant difference in exercise tolerance between Sildenafil and placebo [50]. A larger Phase 3 study by Pfizer is currently ongoing and was scheduled to complete in 2009, but no results have been reported.

Thalidomide (Thalomid™)

Thalidomide is an anti-angiogenic and anti-inflammatory small molecule drug administered orally and is under investigation in IPF by Celgene (www.celgene.com). Thalidomide, which is sold as Thalomid™ for the treatment of multiple myeloma, has shown efficacy in preventing fibrosis in the bleomycin lung model [51] that correlated with reductions in interleukin-6 (IL-6), Transforming Growth Factor β (TGF-β and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) expression. An initial open label uncontrolled Phase 2 clinical trial was conducted in 19 IPF patients given 400 mg of oral thalidomide daily for 12 months. Results on lung function have not been presented from this trial, but a report indicating positive effects on reducing chronic cough in IPF patients has been presented [52], and a new Phase 3 clinical trial for the prevention and treatment of chronic cough in IPF has been initiated.

Imatinib mesylate (Gleevec™)

Imatinib mesylate, better known as Gleevec™, is a tyrosine kinase inhibitor administered orally and under investigation in IPF by Novartis (www.novartis.com). Imatinib mesylate was initially designed and approved for the treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), due to its potent inhibition of the bcr-abl tyrosine kinase, however it also potently inhibits the PDGFR tyrosine kinase and the stem cell factor receptor c-kit tyrosine kinase. PDGF-mediated fibroblast activation has been implicated in IPF [53], and imatinib mesylate inhibits preclinical models of pulmonary fibrosis [54-58]. An initial Phase 2 clinical trial was conducted in 120 IPF patients comparing 600 mg of imatinib mesylate to placebo, but the drug failed to improve survival or changes in forced vital capacity (FVC) [59]. A smaller Phase 2 clinical trial in SSc w/ILD patients recently completed with more positive results. 30 patients with severe SSc were given 400 mg of Gleevec daily. A presentation at the 2009 meeting of the American College of Rheumatology meeting indicated that after one year of treatment, the patients had improvements in lung function ranging from 9.6 to 11 percent as assessed by FVC and diffusion capacity.

Etanercept (Enbrel™)

Etanercept, better known as Enbrel™, is an anti-inflammatory biologic drug product administered by subcutaneous injection under investigation in IPF by Wyeth (www.wyeth.com). Etanercept is a soluble form of TNFα-receptor that blocks its interaction with ligand. TNFα in combination with IL-13 induces TGF-β production from monocytes, and etanercept administration significantly prevents fibrosis in the bleomycin model [60]. An initial randomized, prospective, double-blind Phase 2 clinical trial was conducted in 88 IPF patients comparing 25 mg twice weekly subcutaneous etanercept to placebo [61]. The primary endpoint was a change in percent predicted FVC and DLco over 48 weeks. Although there were no statistical differences in the predefined endpoints, a trend toward reduction in death or disease progression was observed in post hoc analysis.

Zileuton (Zyflo™)

Zileuton, also known as Zyflo™, is a 5-lipoxygenase (5-LO) inhibitor administered orally and under investigation in IPF by Cornerstone Therapeutics (formerly Critical Therapeutics, www.crtx.com). 5-LO is an enzyme responsible for converting arachidonic acid into the leukotrienes LTB4 and LTC4. These leukotrienes have inflammatory and fibrotic properties and are upregulated in the lungs of IPF patients [62]. Zileuton is currently approved for the treatment of asthma, and has also been shown to inhibit inflammation and fibrosis in the bleomycin model [63]. An initial Phase 2 clinical trial with a planned enrollment of 140 IPF patients comparing six months of treatment of zileuton to azathioprine/prednisone is currently ongoing. The primary endpoint of this trial is change in LTB4 levels in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid following six months of treatment. Secondary endpoints are progression free survival, change in dyspnea, change in quality of life, and change in physiology.

Tetrathiomolybdate (Coprexa™)

Tetrathiomolybdate, also known as Coprexa™, is a small molecule copper chelator administered orally and under investigation in IPF by Adeona Pharmaceuticals (formerly Pipex Therapeutics, www.adeonapharma.com). Tetrathiomolybdate complexes copper to protein and itself, rendering the copper unavailable for cellular uptake [64]. It was originally developed for Wilson’s disease, and is also being developed as an anti-angiogenic agent for the treatment of cancer. Many angiogenic cytokines require normal levels of copper, and lowered copper levels reduce cytokine signaling while cellular copper requirements are met. Tetrathiomolybdate was shown to reduce fibrosis in the bleomycin model, and this effect was associated with inhibition of TNFα and TGF-β expression in lung homogenates [65, 66]. An initial single-center, open-label, Phase 1/2 clinical trial was completed in 20 patients with IPF that had evidence of disease progression despite treatment with prednisone +/− cytotoxic therapy. The trial tested 20mg oral tetrathiomolybdate twice a day for 12 months. Primary endpoints were safety, percent FVC, Dlco and exercise capacity (six minute walk distance), compared to baseline at 6 and 12 months. The only endpoint to reach statistical significance was the relative appearance of ground glass under high resolution computed tomography (HRCT). The current status of this program is unknown.

BIBF-1120

BIBF-1120, also known as vargatef, is a tyrosine kinase inhibitor with specificity for VEGF, PDGF, and FGF receptor kinases. It is administered orally and under investigation in IPF by Boehringer Ingelheim (www.boehringer-ingelheim.com). BIBF-1120 is also being tested in parallel in a variety of cancer trials. A related analogue in the series, BIBF-1000 has demonstrated efficacy in reducing the severity of histopathology and fibrotic gene expression in the rat bleomycin model when dosing was initiated at day 10 [56]. However, collagen protein was not quantitated. A 12 month, double blind, randomized, placebo-controlled Phase 2 trial comparing the effect of BIBF-1120 administered at oral doses of 50 mg qd, 50 mg bid, 100 mg bid and 150 mg bid versus placebo in 432 patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis is currently ongoing. The primary endpoint is the rate of decline in FVC, evaluated from baseline until 12 month of treatment, compared to placebo. Completion of the trial is expected in 2010.

CNTO-888

CNTO-888 is a monoclonal antibody targeting human chemokine ligand 2 (CCL-2), also known as monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 (MCP-1). It is administered by IV infusion and under investigation in IPF by Centocor (a division of J&J Phamaceuticals, www.centocor.com). CNTO-888 is also being tested in parallel in a variety of cancer trials. Several studies have demonstrated an increase in the levels of CCL-2 in the BAL fluid of IPF patients relative to controls [67-70]. In addition, similar antibodies to CNTO-888 targeting the homologous murine proteins JE and MCP-5, when used in combination, have demonstrated efficacy in reducing fibrosis in the bleomycin model when dosed concurrent to injury [71]. A 48 week, double blind, randomized, placebo-controlled Phase 2 trial comparing the effect of CNTO-888 administered by IV infusion every 4 weeks of 1 mg/kg, 5 mg/kg, or 15 mg/kg versus placebo in 120 patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis is currently ongoing. The primary endpoint is the rate of decline in pulmonary function, evaluated from baseline until 48 weeks of treatment, compared to placebo. Completion of the primary outcome of the trial is expected in 2012.

Octreotide

Octreotide is a somatostatin analog, and radiolabeled octreotide accumulates in the lungs of patients with IPF [72]. A Phase 2 trial of 30 mg octreotide injected IM every 4 weeks for 48 weeks in patients with IPF was started in France in 2006, with endpoints of lung function, lung appearance in HRCT, a 6 minute walking test, quality of life, and survival. Reports of this trial are not in the literature.

GC-1008

GC1008 is a pan-neutralizing IgG4 human antibody directed against all three isoforms of TGF-β. It is administered by IV infusion and under investigation in IPF by Genzyme (www.genzyme.com). TGF-β expression is increased in the lungs of patients with IPF relative to non fibrotic lung diseases and health controls [73]. In vitro, TGF-β is one of the most pro-fibrogenic cytokines known and in vivo is both necessary and sufficient for fibrotic disease induction and progression in many preclinical models including the bleomycin lung model [11]. GC-1008 has completed a Phase 1 open-label, multi-center, single-dose, dose-escalating trial, in 25 patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Dose levels from 0.3 mg/kg to 8 mg/kg were investigated and the primary endpoints were safety, tolerability and pharmacokinetic of GC-1008. Although this trial was initiated in 2005 and completed in 2008 no formal results have been disclosed and no new trial in pulmonary fibrosis has been described.

FG-3019

FG-3019 is a human monoclonal antibody directed against Connective Tissue Growth Factor (CTGF). It is administered by IV infusion and under investigation in IPF by Fibrogen (www.fibrogen.com). CTGF is implicated in the pathogenesis of IPF and is considered a common pathway of various profibrotic processes [74] [75]. Preclinical models of lung fibrosis demonstrate that FG-3019 reduces scarring associated with CTGF and excess deposition of matrix components (www.fibrogen.com). FG-3019 has completed a Phase 1 open-label, single dose, sequential-group, dose-escalation study in 21 patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Dose levels of 1 mg/kg, 3 mg/kg, and 10 mg/kg were investigated and the primary endpoints were safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics, and immunogenicity of FG-3019. No dose limiting toxicities were reported. Although this trial was completed in 2004, no new trials in pulmonary fibrosis using FG-3019 have been described.

PRM-151

PRM-151 is a recombinant human form of serum amyloid P component (SAP). It is administered by IV infusion and under investigation in IPF by Promedior. PRM-151 specifically targets the monocyte cell population, irrespective of the profibrotic stimulus driving the pathology. In vitro data and in vivo data in preclinical models demonstrate that SAP is broadly effective at blocking the fibrotic process downstream of multiple types of injury and under multiple cytokine stimulation conditions [76-79] [80]. Promedior initiated a Phase 1 study with PRM-151 testing the safety and tolerability of increasing IV doses of PRM-151 in healthy volunteers and IPF patients in July of 2009. Results are expected in early 2010.

3. Conclusion

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis is a fibrosing disease of the lung with a high prevalence and high mortality rate, and no FDA-approved therapeutics. Work using both the bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis rodent model, and studies on tissue from patients, has led to the development of a variety of possible therapeutics which are being tested in human clinical trials.

4. Expert opinion

The significant unmet medical need represented by fibrotic pulmonary diseases has attracted developers of a number of investigational therapeutics; however, most are at a very early stage of clinical development (Table 2). With few exceptions, each of these approaches targets inhibition of a single stimulatory agent. Given the large number of potential chemical mediators driving the fibrotic process in any given tissue, this functional redundancy will likely lead to sub-optimal efficacy with existing experimental therapies under investigation and potentially a requirement for combinatorial therapy similar to current practices in cancer. In addition, several of the cytokines and chemokines that are currently targeted, such as TGF-β, have additional beneficial properties in non-fibrotic tissues. As a result, systemic blockade of TGF-β activity leads to aberrant side effects in animal models and in human patients, further limiting the dosages allowable, and thereby potential efficacy. However, we are encouraged by the approval in Japan, and the possible approval in the US and Europe, of pirfenidone as a new therapeutic option for IPF, and we hope that more of the potential therapeutics described above will prove successful in treating, either alone or in combination, this terrible disease.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Erica Herzog, Yale University School of Medicine, for Figure 1.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest

RH Gomer is a co-founder of, and ML Lupher is an employee of, Promedior Inc. Both authors have equity in and stock options from Promedior. This work was supported in part by NIH R01 HL083029.

Contributor Information

Richard H. Gomer, Texas A&M University, Biology MS 3258, College Station, TX 77843.

Mark L. Lupher, Jr., Discovery Research, Promedior, Inc. 371 Phoenixville Pike, Malvern, PA 19355.

References

- 1.Paget J. Lectures on Surgical Pathology Delivered at the Royal College of Surgeons of England. Wilson and Ogilvy; London: 1853. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bucala R, Spiegel L, Chesney J, Hogan M, Cerami A. Circulating fibrocytes define a new leukocyte subpopulation that mediates tissue repair. Mol Med. 1994;1:71–81. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chesney J, Bacher M, Bender A, Bucala R. The peripheral blood fibrocyte is a potent antigen-presenting cell capable of priming naive T cells in situ. ProcNatlAcadSciUSA. 1997;94(12):6307. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.12.6307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chesney J, Metz C, Stavitsky AB, Bacher M, Bucala R. Regulated production of type I collagen and inflammatory cytokines by peripheral blood fibrocytes. JImmunol. 1998;160(1):419–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abe R, Donnelly SC, Peng T, Bucala R, Metz CN. Peripheral blood fibrocytes: differentiation pathway and migration to wound sites. JImmunol. 2001;166(12):7556–62. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.12.7556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Friedman SL. Mechanisms of hepatic fibrogenesis. Gastroenterology. 2008 May;134(6):1655–69. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lin SL, Kisseleva T, Brenner DA, Duffield JS. Pericytes and perivascular fibroblasts are the primary source of collagen-producing cells in obstructive fibrosis of the kidney. Am J Pathol. 2008 Dec;173(6):1617–27. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.080433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kalluri R, Weinberg RA. The basics of epithelial-mesenchymal transition. J Clin Invest. 2009 Jun;119(6):1420–8. doi: 10.1172/JCI39104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thiery JP, Acloque H, Huang RY, Nieto MA. Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions in development and disease. Cell. 2009 Nov 25;139(5):871–90. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wynn TA. Fibrotic disease and the T(H)1/T(H)2 paradigm. NatRev Immunol. 2004;4(8):583. doi: 10.1038/nri1412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lupher ML, Jr., Gallatin WM. Regulation of fibrosis by the immune system. Adv Immunol. 2006;89:245–88. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2776(05)89006-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schmidt M, Sun G, Stacey MA, Mori L, Mattoli S. Identification of circulating fibrocytes as precursors of bronchial myofibroblasts in asthma. J Immunol. 2003 Jul 1;171(1):380–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.1.380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Olson AL, Swigris JJ, Lezotte DC, Norris JM, Wilson CG, Brown KK. Mortality from pulmonary fibrosis increased in the United States from 1992 to 2003. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007 Aug 1;176(3):277–84. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200701-044OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Douglas WW, Ryu JH, Schroeder DR. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: Impact of oxygen and colchicine, prednisone, or no therapy on survival. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000 Apr;161(4 Pt 1):1172–8. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.161.4.9907002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schmidt SL, Sundaram B, Flaherty KR. Diagnosing fibrotic lung disease: when is high-resolution computed tomography sufficient to make a diagnosis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis? Respirology. 2009 Sep;14(7):934–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2009.01626.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chua F, Gauldie J, Laurent GJ. Pulmonary fibrosis: searching for model answers. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2005 Jul;33(1):9–13. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2005-0062TR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hanak V, Ryu JH, de Carvalho E, Limper AH, Hartman TE, Decker PA, et al. Profusion of fibroblast foci in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis does not predict outcome. Respir Med. 2008 Jun;102(6):852–6. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2008.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Konishi K, Gibson KF, Lindell KO, Richards TJ, Zhang Y, Dhir R, et al. Gene expression profiles of acute exacerbations of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009 Jul 15;180(2):167–75. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200810-1596OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Strieter RM, Mehrad B. New mechanisms of pulmonary fibrosis. Chest. 2009 Nov;136(5):1364–70. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-0510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.du Bois RM. Strategies for treating idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2010 Feb;9(2):129–40. doi: 10.1038/nrd2958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Selman M, King TE, Pardo A. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: prevailing and evolving hypotheses about its pathogenesis and implications for therapy. Ann Intern Med. 2001 Jan 16;134(2):136–51. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-134-2-200101160-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Davies HR, Richeldi L. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: current and future treatment options. Am J Respir Med. 2002;1(3):211–24. doi: 10.1007/BF03256611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fiorucci E, Lucantoni G, Paone G, Zotti M, Li BE, Serpilli M, et al. Colchicine, cyclophosphamide and prednisone in the treatment of mild-moderate idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: comparison of three currently available therapeutic regimens. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2008 Mar-Apr;12(2):105–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.King TE, Jr., Albera C, Bradford WZ, Costabel U, Hormel P, Lancaster L, et al. Effect of interferon gamma-1b on survival in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (INSPIRE): a multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2009 Jul 18;374(9685):222–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60551-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Prasse A, Muller-Quernheim J. Non-invasive biomarkers in pulmonary fibrosis. Respirology. 2009 Aug;14(6):788–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2009.01600.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brook NR, Waller JR, Bicknell GR, Nicholson ML. The experimental agent pirfenidone reduces pro-fibrotic gene expression in a model of tacrolimus-induced nephrotoxicity. J Surg Res. 2005 May 15;125(2):137–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2004.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Iyer SN, Hyde DM, Giri SN. Anti-inflammatory effect of pirfenidone in the bleomycin-hamster model of lung inflammation. Inflammation. 2000 Oct;24(5):477–91. doi: 10.1023/a:1007068313370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oku H, Shimizu T, Kawabata T, Nagira M, Hikita I, Ueyama A, et al. Antifibrotic action of pirfenidone and prednisolone: different effects on pulmonary cytokines and growth factors in bleomycin-induced murine pulmonary fibrosis. European journal of pharmacology. 2008 Aug 20;590(1-3):400–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2008.06.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mansoor JK, Decile KC, Giri SN, Pinkerton KE, Walby WF, Bratt JM, et al. Influence of pirfenidone on airway hyperresponsiveness and inflammation in a Brown-Norway rat model of asthma. Pulmonary pharmacology & therapeutics. 2007;20(6):660–8. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2006.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tian XL, Yao W, Guo ZJ, Gu L, Zhu YJ. Low dose pirfenidone suppresses transforming growth factor beta-1 and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1, and protects rats from lung fibrosis induced by bleomycina. Chin Med Sci J. 2006 Sep;21(3):145–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schelegle ES, Mansoor JK, Giri S. Pirfenidone attenuates bleomycin-induced changes in pulmonary functions in hamsters. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1997 Dec;216(3):392–7. doi: 10.3181/00379727-216-44187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kehrer JP, Margolin SB. Pirfenidone diminishes cyclophosphamide-induced lung fibrosis in mice. Toxicol Lett. 1997 Feb 7;90(2-3):125–32. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4274(96)03845-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Iyer SN, Wild JS, Schiedt MJ, Hyde DM, Margolin SB, Giri SN. Dietary intake of pirfenidone ameliorates bleomycin-induced lung fibrosis in hamsters. The Journal of laboratory and clinical medicine. 1995 Jun;125(6):779–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang F, Wen T, Chen XY, Wu H. Protective effects of pirfenidone on D-galactosamine and lipopolysaccharide-induced acute hepatotoxicity in rats. Inflamm Res. 2008 Apr;57(4):183–8. doi: 10.1007/s00011-007-7153-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Di Sario A, Bendia E, Macarri G, Candelaresi C, Taffetani S, Marzioni M, et al. The anti-fibrotic effect of pirfenidone in rat liver fibrosis is mediated by downregulation of procollagen alpha1(I), TIMP-1 and MMP-2. Dig Liver Dis. 2004 Nov;36(11):744–51. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2004.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kaibori M, Yanagida H, Yokoigawa N, Hijikawa T, Kwon AH, Okumura T, et al. Effects of pirfenidone on endotoxin-induced liver injury after partial hepatectomy in rats. Transplantation proceedings. 2004 Sep;36(7):1975–6. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2004.08.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kaibori M, Yanagida H, Uchida Y, Yokoigawa N, Kwon AH, Okumura T, et al. Pirfenidone protects endotoxin-induced liver injury after hepatic ischemia in rats. Transplantation proceedings. 2004 Sep;36(7):1973–4. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2004.08.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tsuchiya H, Kaibori M, Yanagida H, Yokoigawa N, Kwon AH, Okumura T, et al. Pirfenidone prevents endotoxin-induced liver injury after partial hepatectomy in rats. Journal of hepatology. 2004 Jan;40(1):94–101. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2003.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Garcia L, Hernandez I, Sandoval A, Salazar A, Garcia J, Vera J, et al. Pirfenidone effectively reverses experimental liver fibrosis. Journal of hepatology. 2002 Dec;37(6):797–805. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(02)00272-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Oku H, Nakazato H, Horikawa T, Tsuruta Y, Suzuki R. Pirfenidone suppresses tumor necrosis factor-alpha, enhances interleukin-10 and protects mice from endotoxic shock. European journal of pharmacology. 2002 Jun 20;446(1-3):167–76. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(02)01757-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tada S, Nakamuta M, Enjoji M, Sugimoto R, Iwamoto H, Kato M, et al. Pirfenidone inhibits dimethylnitrosamine-induced hepatic fibrosis in rats. Clinical and experimental pharmacology & physiology. 2001 Jul;28(7):522–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1681.2001.03481.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schroll S, Arzt M, Sebah D, Nuchterlein M, Blumberg F, Pfeifer M. Improvement of bleomycin-induced pulmonary hypertension and pulmonary fibrosis by the endothelin receptor antagonist Bosentan. Respiratory physiology & neurobiology. 2009 Nov 28; doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2009.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mutsaers SE, Marshall RP, Goldsack NR, Laurent GJ, McAnulty RJ. Effect of endothelin receptor antagonists (BQ-485, Ro 47-0203) on collagen deposition during the development of bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis in rats. Pulmonary pharmacology & therapeutics. 1998 Apr-Jun;11(2-3):221–5. doi: 10.1006/pupt.1998.0142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Park SH, Saleh D, Giaid A, Michel RP. Increased endothelin-1 in bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis and the effect of an endothelin receptor antagonist. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 1997 Aug;156(2 Pt 1):600–8. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.156.2.9607123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Atkuri KR, Mantovani JJ, Herzenberg LA. N-Acetylcysteine--a safe antidote for cysteine/glutathione deficiency. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2007 Aug;7(4):355–9. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2007.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Demedts M, Behr J, Buhl R, Costabel U, Dekhuijzen R, Jansen HM, et al. High-dose acetylcysteine in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. The New England journal of medicine. 2005 Nov 24;353(21):2229–42. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa042976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rempe S, Hayden JM, Robbins RA, Hoyt JC. Tetracyclines and pulmonary inflammation. Endocr Metab Immune Disord Drug Targets. 2007 Dec;7(4):232–6. doi: 10.2174/187153007782794344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lettieri CJ, Nathan SD, Barnett SD, Ahmad S, Shorr AF. Prevalence and outcomes of pulmonary arterial hypertension in advanced idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Chest. 2006 Mar;129(3):746–52. doi: 10.1378/chest.129.3.746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Collard HR, Anstrom KJ, Schwarz MI, Zisman DA. Sildenafil improves walk distance in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Chest. 2007 Mar;131(3):897–9. doi: 10.1378/chest.06-2101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jackson RM, Glassberg MK, Ramos CF, Bejarano PA, Butrous G, Gomez-Marin O. Sildenafil Therapy and Exercise Tolerance in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Lung. 2009 Dec 12; doi: 10.1007/s00408-009-9209-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tabata C, Tabata R, Kadokawa Y, Hisamori S, Takahashi M, Mishima M, et al. Thalidomide prevents bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis in mice. J Immunol. 2007 Jul 1;179(1):708–14. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.1.708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Horton MR, Danoff SK, Lechtzin N. Thalidomide inhibits the intractable cough of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Thorax. 2008 Aug;63(8):749. doi: 10.1136/thx.2008.098699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hetzel M, Bachem M, Anders D, Trischler G, Faehling M. Different effects of growth factors on proliferation and matrix production of normal and fibrotic human lung fibroblasts. Lung. 2005 Jul-Aug;183(4):225–37. doi: 10.1007/s00408-004-2534-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Li M, Abdollahi A, Grone HJ, Lipson KE, Belka C, Huber PE. Late treatment with imatinib mesylate ameliorates radiation-induced lung fibrosis in a mouse model. Radiation oncology (London, England) 2009;4:66. doi: 10.1186/1748-717X-4-66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vuorinen K, Gao F, Oury TD, Kinnula VL, Myllarniemi M. Imatinib mesylate inhibits fibrogenesis in asbestos-induced interstitial pneumonia. Experimental lung research. 2007 Sep;33(7):357–73. doi: 10.1080/01902140701634827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chaudhary NI, Roth GJ, Hilberg F, Muller-Quernheim J, Prasse A, Zissel G, et al. Inhibition of PDGF, VEGF and FGF signalling attenuates fibrosis. Eur Respir J. 2007 May;29(5):976–85. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00152106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Aono Y, Nishioka Y, Inayama M, Ugai M, Kishi J, Uehara H, et al. Imatinib as a novel antifibrotic agent in bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis in mice. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2005 Jun 1;171(11):1279–85. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200404-531OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Daniels CE, Wilkes MC, Edens M, Kottom TJ, Murphy SJ, Limper AH, et al. Imatinib mesylate inhibits the profibrogenic activity of TGF-beta and prevents bleomycin-mediated lung fibrosis. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2004 Nov;114(9):1308–16. doi: 10.1172/JCI19603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Daniels CE, Lasky JA, Limper AH, Mieras K, Gabor E, Schroeder DR. Imatinib Treatment for Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis: Randomized Placebo-controlled Trial Results. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010 Mar 15;181(6):604–10. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200906-0964OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fichtner-Feigl S, Strober W, Kawakami K, Puri RK, Kitani A. IL-13 signaling through the IL-13alpha2 receptor is involved in induction of TGF-beta1 production and fibrosis. Nature medicine. 2006 Jan;12(1):99–106. doi: 10.1038/nm1332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Raghu G, Brown KK, Costabel U, Cottin V, du Bois RM, Lasky JA, et al. Treatment of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis with etanercept: an exploratory, placebo-controlled trial. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2008 Nov 1;178(9):948–55. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200709-1446OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wilborn J, Bailie M, Coffey M, Burdick M, Strieter R, Peters-Golden M. Constitutive activation of 5-lipoxygenase in the lungs of patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. J Clin Invest. 1996 Apr 15;97(8):1827–36. doi: 10.1172/JCI118612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Failla M, Genovese T, Mazzon E, Gili E, Muia C, Sortino M, et al. Pharmacological inhibition of leukotrienes in an animal model of bleomycin-induced acute lung injury. Respir Res. 2006;7:137. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-7-137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Khan G, Merajver S. Copper chelation in cancer therapy using tetrathiomolybdate: an evolving paradigm. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2009 Apr;18(4):541–8. doi: 10.1517/13543780902845622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Brewer GJ, Ullenbruch MR, Dick R, Olivarez L, Phan SH. Tetrathiomolybdate therapy protects against bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis in mice. J Lab Clin Med. 2003 Mar;141(3):210–6. doi: 10.1067/mlc.2003.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Brewer GJ, Dick R, Ullenbruch MR, Jin H, Phan SH. Inhibition of key cytokines by tetrathiomolybdate in the bleomycin model of pulmonary fibrosis. Journal of inorganic biochemistry. 2004 Dec;98(12):2160–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2004.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Shinoda H, Tasaka S, Fujishima S, Yamasawa W, Miyamoto K, Nakano Y, et al. Elevated CC chemokine level in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid is predictive of a poor outcome of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respiration; international review of thoracic diseases. 2009;78(3):285–92. doi: 10.1159/000207617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Car BD, Meloni F, Luisetti M, Semenzato G, Gialdroni-Grassi G, Walz A. Elevated IL-8 and MCP-1 in the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid of patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and pulmonary sarcoidosis. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 1994 Mar;149(3 Pt 1):655–9. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.149.3.8118632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Capelli A, Di Stefano A, Gnemmi I, Donner CF. CCR5 expression and CC chemokine levels in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Eur Respir J. 2005 Apr;25(4):701–7. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00082604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Suga M, Iyonaga K, Ichiyasu H, Saita N, Yamasaki H, Ando M. Clinical significance of MCP-1 levels in BALF and serum in patients with interstitial lung diseases. Eur Respir J. 1999 Aug;14(2):376–82. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3003.1999.14b23.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Murray LA, Argentieri RL, Farrell FX, Bracht M, Sheng H, Whitaker B, et al. Hyper-responsiveness of IPF/UIP fibroblasts: interplay between TGFbeta1, IL-13 and CCL2. The international journal of biochemistry & cell biology. 2008;40(10):2174–82. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2008.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lebtahi R, Moreau S, Marchand-Adam S, Debray MP, Brauner M, Soler P, et al. Increased uptake of 111In-octreotide in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. J Nucl Med. 2006 Aug;47(8):1281–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Khalil N, O’Connor RN, Unruh HW, Warren PW, Flanders KC, Kemp A, et al. Increased production and immunohistochemical localization of transforming growth factor-beta in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. American journal of respiratory cell and molecular biology. 1991 Aug;5(2):155–62. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb/5.2.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Frazier K, Williams S, Kothapalli D, Klapper H, Grotendorst GR. Stimulation of fibroblast cell growth, matrix production, and granulation tissue formation by connective tissue growth factor. J Invest Dermatol. 1996 Sep;107(3):404–11. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12363389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lasky JA, Ortiz LA, Tonthat B, Hoyle GW, Corti M, Athas G, et al. Connective tissue growth factor mRNA expression is upregulated in bleomycin-induced lung fibrosis. Am J Physiol. 1998 Aug;275(2 Pt 1):L365–71. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1998.275.2.L365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Pilling D, Buckley CD, Salmon M, Gomer RH. Inhibition of fibrocyte differentiation by serum amyloid P. J Immunol. 2003 Nov 15;171(10):5537–46. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.10.5537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Haudek SB, Xia Y, Huebener P, Lee JM, Carlson S, Crawford JR, et al. Bone marrow-derived fibroblast precursors mediate ischemic cardiomyopathy in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006 Nov 28;103(48):18284–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608799103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Pilling D, Roife D, Wang M, Ronkainen SD, Crawford JR, Travis EL, et al. Reduction of bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis by serum amyloid P. J Immunol. 2007 Sep 15;179(6):4035–44. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.6.4035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Naik-Mathuria B, Pilling D, Crawford JR, Gay AN, Smith CW, Gomer RH, et al. Serum amyloid P inhibits dermal wound healing. Wound Repair Regen. 2008 Mar-Apr;16(2):266–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2008.00366.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lin SL, Castano AP, Nowlin BT, Lupher ML, Jr., Duffield JS. Bone marrow Ly6Chigh monocytes are selectively recruited to injured kidney and differentiate into functionally distinct populations. J Immunol. 2009 Nov 15;183(10):6733–43. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Raghu G, Weycker D, Edelsberg J, Bradford WZ, Oster G. Incidence and prevalence of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006 Oct 1;174(7):810–6. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200602-163OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Robinson D, Jr., Eisenberg D, Nietert PJ, Doyle M, Bala M, Paramore C, et al. Systemic sclerosis prevalence and comorbidities in the US, 2001-2002. Curr Med Res Opin. 2008 Apr;24(4):1157–66. doi: 10.1185/030079908x280617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.McNearney TA, Reveille JD, Fischbach M, Friedman AW, Lisse JR, Goel N, et al. Pulmonary involvement in systemic sclerosis: associations with genetic, serologic, sociodemographic, and behavioral factors. Arthritis Rheum. 2007 Mar 15;57(2):318–26. doi: 10.1002/art.22532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Zureik M, Neukirch C, Leynaert B, Liard R, Bousquet J, Neukirch F. Sensitisation to airborne moulds and severity of asthma: cross sectional study from European Community respiratory health survey. BMJ. 2002 Aug 24;325(7361):411–4. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7361.411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]