Abstract

Zeolites containing transition metal ions (TMI) often show promising activity as heterogeneous catalysts in pollution abatement and selective oxidation reactions. In this paper, two aspects of research on the TMI Cu, Co and Fe in zeolites are discussed: (i) coordination to the lattice and (ii) activated oxygen species. At low loading, TMI preferably occupy exchange sites in six-membered oxygen rings (6MR) where the TMI preferentially coordinate with the oxygen atoms of Al tetrahedra. High TMI loadings result in a variety of TMI species formed at the zeolite surface. Removal of the extra-lattice oxygens during high temperature pretreatments can result in auto-reduction. Oxidation of reduced TMI sites often results in the formation of highly reactive oxygen species. In Cu-ZSM-5, calcination with O2 results in the formation of a species, which was found to be a crucial intermediate in both the direct decomposition of NO and N2O and the selective oxidation of methane into methanol. An activated oxygen species, called α-oxygen, is formed in Fe-ZSM5 and reported to be the active site in the partial oxidation of methane and benzene into methanol and phenol, respectively. However, this reactive α-oxygen can only be formed with N2O, not with O2. O2 activated Co intermediates in Faujasite (FAU) zeolites can selectively oxidize α-pinene and epoxidize styrene. In Co-FAU, CoIII superoxo and peroxo complexes are suggested to be the active cores, whereas in Cu and Fe-ZSM-5 various monomeric and dimeric sites have been proposed, but no consensus has been obtained. Very recently, the active site in Cu-ZSM-5 was identified as a bent [Cu-O-Cu]2+ core (Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 18908-18913). Overall, O2 activation depends on the interplay of structural factors such as type of zeolite, size of the channels and cages and chemical factors such as Si/Al ratio and the nature, charge and distribution of the charge balancing cations. The presence of several different TMI sites hinders the direct study of the spectroscopic features of the active site. Spectroscopic techniques capable of selectively probing these sites, even if they only constitute a minor fraction of the total amount of TMI sites, are thus required. Fundamental knowledge of the geometric and electronic structure of the reactive active site can help in the design of novel selective oxidation catalysts.

1. Introduction

The interaction of O2 with the surface atoms in the micropores and channels of zeolites has been studied since the 1960’s. It was recognized at that time that the adsorption enthalpy of N2 in zeolite A (LTA, Figure 1A) was systematically higher than that of O2, because of the quadrupolar moment of N2. The pressure-swing-adsorption (PSA) process was developed to separate O2 and N2 from air on an industrial scale.1-6 The adsorption enthalpy of O2 at zero coverage is 15-20 kJ/mol. The adsorbed molecule is coordinated end-on to the exchangeable cations, thus making the infrared (IR) inactive stretching vibration of O2 active. The measured values range from 1555 – 1552 cm−1 for alkali and alkaline earth exchanged zeolites, slightly below the 1556 cm−1 measured by Raman spectroscopy for gaseous O2.7-9 However, for the O2 in interaction with Cu+ in FAU, O=O stretching vibrations at 1256 and 1180 cm−1 were recently measured.10 These were ascribed to O2 interacting with Cu+ in sites II and III of the FAU framework, respectively (See Figure 1B). This red shift points to a significant weakening of the O=O bond due to electron transfer from Cu+ to the π* antibonding orbitals of O2.

Figure 1.

Industrially most important zeolite structures: A) LTA, B) X and Y (FAU topology), C) ZSM-5 (MFI topology), D) MOR, E) FER and F) *BEA. The symbols I, I′, II, II′, III, and III′ indicate exchangeable cation sites in LTA and FAU. The lines represent the O atoms; the corners Si or Al atoms. ZSM-5, MOR and FER are also known as pentasil zeolites.

Such an electron transfer was already observed in the 1970’s by Klier and coworkers in zeolite A loaded with TMI.11-14 Thus, Cr(II)-A reversibly adsorbs one O2 per Cr(II) at room temperature (RT). The spectral changes point to the reaction:

And similarly for Cu+:

Fe2+ in zeolite A does not bind O2 at RT, but upon heating in O2 Fe2+ is oxidized to Fe3+ and the formation of a Fe3+ -O- Fe3+ species was suggested.14

At about the same time Lunsford and coworkers prepared faujasite-type zeolites (Figure 1B) loaded with amine complexes of Cu2+ and Co2+.15, 16 The Co-amine complexes take up O2 at RT to form the corresponding mononuclear superoxo complexes, identified by their characteristic UV-VIS and EPR spectra. These mononuclear superoxo complexes were unstable due to their mobility in the zeolitic cavities and evolved slowly into dinuclear peroxo complexes.17, 18 Later on, bulky Co complexes were synthesized in the supercages of zeolite Y. These complexes were trapped in the supercages and could not diffuse through the zeolitic cavity system. Upon interaction with O2 stable mononuclear superoxo complexes were obtained.18

In the search for new and improved heterogeneous catalysts for pollution abatement and selective oxidation, research was redirected to TMI in mordenite (MOR) and MFI-type zeolites (Figure 1C and D), with ZSM-5 (a zeolite with MFI topology) as the most prominent example. In this paper we discuss the activation of O2 by TMI in these zeolite topologies with special emphasis on selective oxidation of hydrocarbons and catalytic decomposition of N2O and NO into N2 and O2. After a short introduction on the fundamentals of zeolite structures, this contribution presents an overview on the present state of knowledge of the coordination of TMI with surface oxygen. Several excellent reviews have been published on the catalytic oxidation of organic substrates by TMI in zeolites or on other supports.19-24 In this paper we will focus mainly on the first row transition metals Cu, Fe and Co in zeolites. As some of these coordinated TMI are able to activate O2 or N2O under moderate conditions, understanding their geometric and electronic structures might lead to the development of novel active and selective oxidation catalysts.

2. Zeolites

Zeolites are three-dimensional microporous silicates. The primary building unit is the [SiO4]−4 tetrahedron. It forms a three-dimensional network by corner-sharing of the 4 oxygen atoms and leads to charge neutral network.1, 25 Due to the crystalline ordering, zeolites contain ordered pores and cavities that have characteristic shapes and sizes. 176 different structure types are known.26 Some of these can be found in nature as minerals, but most are synthetic materials. Corner sharing and strictly alternating negatively charged Al and positively charged P tetrahedra, [AlO4]−5 and [PO4]−3, can also be used as primary tetrahedral units. They give the so-called crystalline, microporous AlPO materials. Some of them are isostructural with the silicates, others do not have a siliceous counterpart. Zeolites are represented with three letters codes, that are under the supervision of the structure commission of the International Zeolite Association (IZA).26, 27

Isomorphous substitution is the replacement of a cation in the lattice by another cation with approximately the same size but with different charge. The most important is the substitution of Si4+ by Al3+, thus giving an overall negative charge to the framework. This charge is neutralized by exchangeable cations, located in the channels or cages of the structure. The amount of exchangeable cations is expressed by the cation exchange capacity (CEC). In principle the degree of Al for Si substitution ranges from zero (Si/Al = infinity) to Si/Al = 1. Whatever the Si/Al ratio, the isomorphous substitution obeys Loewenstein’s rule: two Al tetrahedra cannot be neighbors sharing an oxygen atom.1 Thus, an Al tetrahedron must share its 4 oxygens with 4 Si tetrahedra, and with Si/Al = 1 a strict alternation of Si- and Al-tetrahedra occurs in the structure. Such is the case for zeolite A (LTA).

In industrial applications the most important zeolites are Linde Type A zeolite (LTA), FAU, MFI and MOR. Their idealized structures are shown in Figure 1. Table 1 summarizes their unit cell dimensions and typical sizes of their channels/cages. The dimensions of the zeolite pores allow for separation of molecules on the basis of their sizes, the so-called molecular sieving effect. In catalysis this property is often referred to as shape selectivity.25 An example is the cracking of alkanes in acid MFI-type zeolites. Here the zeolite pores allow only the linear molecules to enter the pores containing the acid sites that regulate the cracking. Branched molecules are excluded from the pores and hence do not react.28

Table 1.

Pore sizes, typical unit cell compositions and dimensionality of the channel systems of LTA, FAU MFI, MOR, FER and *BEA.26

| Zeolite topology |

Pore sizes (Å) | Unit cell | Channel system |

|---|---|---|---|

| LTA | 8-ring: 4.1 × 4.1 | |Na+12 (H2O)m| [Al12Si12 O48] | 3-dimensional |

| FAU | 12-ring: 7.4 × 7.4 | (Ca2+Mg2+Na+2)29 (H2O)m| [Al58Si134 O384] | 3-dimensional |

| MFI | 10-ring: 5.1 × 5.5 10-ring: 5.3 × 5.6 |

|Na+n (H2O)m| [AlnSi96-n O192] | 3-dimensional |

| MOR | 12-ring: 6.5 × 7.0 8-ring: 2.6 × 5.7 |

|Na+8 (H2O)m| [Al8Si40 O96] | 1-dimensional |

| FER | 10-ring: 4.2 × 5.4 8-ring: 3.5 × 4.8 |

|Mg2+2Na+2 (H2O)m| [Al6Si30 O72]- | 2-dimensional |

| *BEA | 12-ring: 6.6 × 6.7 12-ring: 5.6 × 5.6 |

|Na+7(H2O)m | [Al7Si57 O128] | 3-dimensional |

Another area of zeolite research is the immobilization of homogeneous catalysts. In FAU zeolites for instance, TMI complexes exchanged in the supercages are readily accessible for reagents (unlike the TMI exchanged in the sodalite cages,29 that are only accessible through a 6MR). After reaction, a simple filtration suffices to separate the catalyst from the reaction products. This separation is often problematic in the case of homogeneous catalysts. As an example, superoxo and peroxo complexes have been obtained in the supercages of zeolite Y by interaction of O2 with cobalt-amine complexes, immobilized in the supercages of zeolite Y.18 There are several ways to synthesize these complexes in the supercages, the preferred procedure depending on the type of complex. If the complexes are stable under exchange conditions, cationic and smaller than the free diameter of the 12 membered ring (MR) giving access to the supercages, they can be exchanged from aqueous solution. Other syntheses involve the adsorption of appropriate ligands in the zeolite, pre-exchanged with TMI, or the complexes can be synthesized in situ e.g. in the supercages of FAU-type zeolites.18, 19, 30

TMI can in principle substitute for Si4+ or Al3+ in the zeolitic structures during synthesis, resulting in a zeolite lattice containing TMI. Parameters to be taken into account are: (i) size and charge of the TMI; (ii) pH of the synthesis medium; (iii) the ability of the TMI to adopt tetrahedral coordination with oxygen atoms. In most cases, the amount of TMI incorporated in the lattice by hydrothermal synthesis is very limited. The two most common examples are Ti4+ and Fe3+. Ti4+ exchanged in silicalite for instance is called TS-1 and is found to be an active catalyst in converting benzene with hydrogen peroxide into phenol.31-33 Fe3+ in the lattice is often due to the presence of impurity in zeolite synthesis, but it can also be added as a reagent into the synthesis mixture. One of the problems with TMI in the lattice is thermal stability. Upon high temperature treatment, some of the TMI in the structure are extracted and found as so-called extra-lattice TMI, which can be monomeric, dimeric or appear as oligomers.34 All of them are possible catalytic sites.

Aqueous ion exchange is the most commonly used method for preparing zeolites with TMI located at exchange sites. The resulting material contains aqueous TMI in the pores and cavities of the zeolite. Upon high temperature treatment water is removed and the TMI coordinates to surface oxygens of the exchange sites. These sites have been compiled by Mortier a long time ago.35 They are crystallographically well defined in the case of zeolites with low Si/Al ratios such as LTA, FAU and MOR (Figure 1). This is much less so for zeolites with high Si/Al ratios such as MFI.

As aqueous solutions of TMI can be acidic, the exchange reaction can be accompanied by side reactions such as the exchange of protons and partial lattice destruction. To avoid these side effects other exchange techniques have been developed, including solid state exchange,36-38 or simply buffering the aqueous solution.39, 40

3. Coordination of TMI in zeolite channels and cages

As mentioned above, isomorphous substitution of Al3+ for Si4+ renders the zeolite framework negatively charged. This negative charge is compensated by extra-framework cations located in the pores or cages of the zeolite. As these cations are not part of the framework, they can be exchanged by other cations, in particular TMI. The actual location depends on several factors among which are the Si/Al ratio, the total amount of TMI, charge of the TMI, exchange method and conditions (pH and temperature being the most important).

Initially, the TMI will occupy the most favorable exchange sites and try to maximize their coordination number. In FAU for instance, after dehydration, the TMI are preferably located inside the hexagonal prisms (sites I, Figure 1B) and in the sodalite cages (sites I′, Figure 1B). At higher loadings, the more accessible exchange sites in the supercages (accessible through 12 membered oxygen rings (12MR)) are occupied (sites II and III, Figure 1B). Among these sites, sites I′ and II are the most important. Both are six-membered oxygen rings (6MR). In MFI, TMI are located in the ten-membered ring (10MR) channels or at channel intersections. They are coordinated to six-membered rings containing one or two Al tetrahedra, but 5MR with one Al cannot be excluded. The same holds for MOR with its 12MR and 8MR channel system.35

TMI coordinated to the zeolite lattice have typical spectroscopic signatures, i.e. d-d transitions and EPR spectra. These spectra are usually reasonably resolved at low loadings of TMI. In the work of Wichterlova and co-workers,41-46 three exchange sites are discerned for Co ions in pentasil zeolites and Beta (*BEA), denoted as α, σ and γ sites. In Figure 2A, an overview of these sites is shown and their location in ZSM-5 is given in Figure 2B. Co2+ exchanged into one of these sites results in a characteristic set of d-d transitions in the UV-vis spectrum as shown in Table 2. Using chemometric techniques Verberckmoes et al. identified three different types of coordination sites for Co2+ in LTA and FAU zeolites from their ligand field absorption spectrum: trigonal and pseudo-tetrahedra sites in site I′, II and II′ and a pseudo-octahedral in site I (only in FAU) (Figure 1).47, 48

Figure 2.

A) Local framework structures of α, β and γ sites in the MOR, ferrierite (FER), MFI and Beta (*BEA) zeolites.41 B) crystallographic position of these sites in ZSM-5.49 Reproduced by permission of the PCCP Owner Societies.

Table 2.

| Zeolite | Energy (cm−1) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Site: | α | β | γ |

| MFI | 15 100 | 16 000, 17 150, 18600, 21 200 | 20 100, 22 000 |

| MOR | 14 800 | 15 900, 17 500, 19 200, 21 100 | 20 150, 22 050 |

| FER | 15 000 | 16 000, 17 100, 18 700, 20 600 | 20 300, 22 000 |

| *BEA | 14 600 | 15 500, 16 300, 17 570, 21 700 | 18 900, 22 060 |

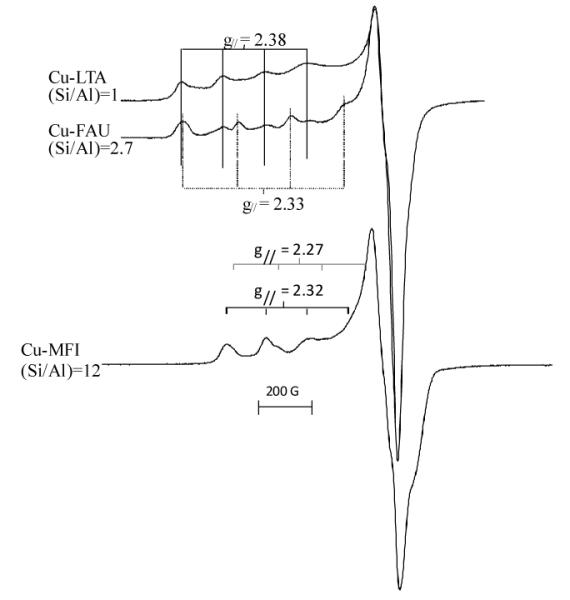

In the work of Schoonheydt and co-workers,49-54 a set of Cu-containing zeolites was studied with UV-vis-NIR absorption and EPR spectroscopies. Examples of EPR spectra are shown in Figure 3, and the d-d transitions and EPR parameters of these Cu2+ sites are summarized in Table 3. For Cu2+ in FAU and LTA, 3 d-d transitions are resolved with the most intense band in the region 10500 – 11000 cm−1 and two weaker bands around 12500 cm−1 and 15000 cm−1. The corresponding EPR spectra reveal two signals, one with gll = 2.37-2.41 common for LTA and FAU and one with gll = 2.30-2.34, not found in LTA. For MOR and MFI the d-d transitions occur at higher energies and overlap such that only a broad band is observed at around 14000 cm−1. This d-d spectrum is accompanied by 2 EPR signals with characteristic gll values of 2.30-2.33 and 2.26-2.28. The g⊥ values are all situated in the 2.09 - 2.05 range but the hyperfine splitting in the perpendicular region is not well resolved.

Figure 3.

Typical EPR spectra of Cu2+-LTA, Cu2+-FAU and Cu2+-MFI after dehydration in O2 at 450°C.

Table 3.

d-d transitions and EPR parameters of Cu2+ coordinated to six-membered oxygen rings in zeolites after dehydration (O2 at 450°C).54, 59

| zeolite | d-d transitions (cm−1) | gll | All ×10−4 cm−1 | g⊥ | A⊥ ×10−4 cm−1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LTA | 10500, 12200,15100 | 2.37-2.41 | 130-145 | 2.06-2.07 | 19 |

| FAU | 10300-10700, 12600,15000 |

2.36-2.41 | 120-145 | 2.06-2.08 | 19 |

| 2.30-2.34 | 171-188 | 2.05-2.07 | 19 | ||

| MOR, MFI | 14000(broad) | 2.30-2.33 | 156-180 | 2.04-2.07 | 3-25 |

| 2.26-2.28 | 168-192 | 2.05-2.07 | 3-25 |

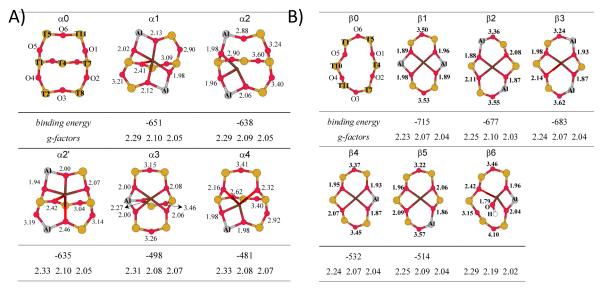

These spectra have traditionally been interpreted in terms of Cu2+ coordinating the 6MR’s in a trigonal configuration (C3v). The two EPR signals are then ascribed to 6MR’s in different crystallographic positions, such as sites I′ and II in FAU (Figure 1B), irrespective of the number of Al tetrahedra making up the 6MR’s. A ligand field analysis of the d-d transitions of Co2+ and Cu2+ in six-ring sites indicated that the TMI are not symmetrically coordinated in the center of the ring, but undergo an off-axial displacement.55-58 Detailed ab initio quantum-chemical analysis revealed that coordination of Cu2+ or Co2+ in a specific exchange site leads to a strong site distortion.49, 51-54 First, the TMI try to maximize their coordination number. Second, the oxygens of the Al tetrahedra are preferentially coordinated to the TMI. This leads to site distortion and the TMI is not located exactly in the center of the 6MR. This is shown in Figure 4 for Cu2+ coordinated to lattice O atoms in the α, β and γ site in ZSM-5. This distortion depends on the number of Al tetrahedra making up the coordination site. Thus, a TMI in one crystallographic exchange site can have several spectroscopic signatures, depending on the number of Al tetrahedra. All these studies taken together lead to the conclusion that both the crystallographic position of the exchange site and the number of Al tetrahedra making up the site determine the spectroscopic signatures of the TMI in that site (see Figure 4).

Figure 4.

The optimized Cu(II) coordination (brown) in the α (A), β (B) and γ (C) sites of ZSM-5 containing 1 or 2 lattice Al T-sites. The corresponding Cu-O distances (Å), Cu(II) binding energies (kcal mol−1) and g-factors of the distorted sites are given. The Cu(II) free sites are shown as α0, β0 and γ0. 49 Reproduced by permission of the PCCP Owner Societies.

At high TMI loading, additional less energetically favorable exchange sites are occupied providing fewer coordination bonds to lattice O-atoms. The spectroscopic signatures of TMI in these sites are much less resolved since at high TMI loadings various TMI species can co-exist: mononuclear, di- and oligonuclear clusters up to chains of TMI. Often, the classical techniques used to characterize TMI in zeolites, such as UV-vis absorption, EPR, XRD and EXAFS give averages of overlaying spectra. At higher TMI loadings, some of the paramagnetic TMI might be EPR silent due to anti-ferromagnetic coupling and dipolar broadening, and subtle changes in the ligand field of TMI at various sites result in the formation of overlapped unresolved absorption features. Further, EXAFS gives spectra which are a superposition from TMI in different sites. Thus it is extremely difficult to distinguish the contributions of a specific TMI site.

TMI sites can act as catalytic centers if they have open coordination sites and if they are readily accessible for guest molecules. In FAU zeolites, 6MR’s separate the sodalite cages from the supercages, and as a result the TMI located inside the sodalite cages are inaccessible to molecules, which cannot diffuse through the 6MR with a free diameter of ~0.23 nm. In MFI, TMI are located in the straight or zigzag 10MR channels which have a free diameter of −0.55 nm. These are the only sites that can contribute to the overall catalytic activity. Similar considerations can be made for other zeolites: the smaller the pores, the less accessible the sites. In addition, larger pores allow for faster diffusion of reagents to the active sites inside the zeolite crystals and for the efficient release of reaction products out of the zeolite crystals, thereby: i) liberating the active site faster for a second reaction, and ii) decreasing the probability of unwanted side reactions, thus increasing the selectivity.

TMI-loaded zeolites such as Co3+, Fe3+ and Cu2+ can undergo auto-reduction during high temperature pretreatment in He or vacuum. The auto-reduction of Fe3+ to Fe 2+ during He treatments is reported60-63 and confirmed by L and K edge XAS measurements.64-67 It was attributed to the dehydration and desorption of O2 from two Fe3+(OH)2 sites leaving two Fe2+(OH) species.62, 68 In Cu-zeolites, it has been reported that this auto-reduction can be achieved by dehydration of two Cu2+(OH) sites, resulting in a Cu+ and a Cu2+-O− site69 or a bridged binuclear Cu2+ site. In the latter case desorption of O2 gives two Cu+.70In Cu-FAU, the auto-reduction was suggested to involve the formation of “[AlO]+” Lewis acid sites as first described by Jacobs and Beyer,71 although the former process was also suggested. This auto-reduction for Cu-zeolites is confirmed by XAFS spectroscopy, showing a reduction of the number of O atoms constituting the first coordination shell and the observation of a feature at 8983 eV in the XANES spectra,72 assigned as the 1s → 4p transition in Cu+.73 In addition, monovalent copper in MFI is characterized by 2 typical luminescence bands around 470-490 nm and 520-540 nm, assigned to transitions from the 3d94s1 triplet state to the 3d10 singlet ground state.74-76 The 480 nm band is assigned to Cu+ coordinated to 3-4 oxygens of the 6MR in the sinusoidal channels of ZSM-5. The 540 nm emission is attributed to Cu+ coordinated to 2 oxygen atoms at channel intersections. As for Cu2+, the preferred oxygen atoms in the coordination sphere of Cu+ are those of the Si-O-Al bridges. What is still unclear is whether the sites of Cu+ are the same as those of Cu2+, in other words, whether or not the reduction of divalent copper is accompanied by a migration of Cu+ to a new coordination site.

4. Activated oxygen on TMI and its reactivity

4.1 Cu-zeolites

Auto-reduction is a crucial step in the catalytic decomposition of NO and N2O into N2 and O2 over Cuzeolite catalysts. Indeed, the oxygen atoms of N2O and NO are deposited on Cu+ with release of N2 and N2O respectively. In the rate limiting step, these deposited oxygen atoms recombine and desorb as molecular oxygen.29, 72, 77-80 The closer the deposited O species are located to each other, the faster is the recombination. This is shown in Figure 5 for the N2O decomposition over a range of Cu-exchanged zeolites. Here the amount of EPR-silent Cu2+ is used as a measure of the average Cu-Cu distance, as Cu2+ becomes EPR-inactive due to anti-ferromagnetic coupling or dipolar broadening between closely located Cu2+ cores. A smooth increase of the N2O decomposition activity with the amount of EPR-silent Cu has been observed in MOR, FER, and BEA catalysts.80 Notably, Cu-ZSM-5 shows a much higher activity for decomposing N2O, as can be seen in Figure 5. Clearly, a special type of active site must be present in ZSM-5. A similar trend was observed in the decomposition of NO. Cu- rich ZSM-5 samples (with Cu/Al>0.2) show much higher activity compared to other Cu-zeolites. In the work of Schoonheydt and coworkers, this was attributed to the presence of an unique Cu core with a characteristic absorption feature around 22 700 cm−1, which was detected by in situ UV-VIS absorption spectroscopy during catalytic decomposition of NO and N2O.77, 80

Figure 5.

Activity per Cu (TOF) for N2O decomposition as a function of the EPR silent Cu2+ in (◆) Cu-ZSM-5 (Si/Al=12) (▲) Cu-MOR (Si/Al=8.8), (•) Cu-BEA (Si/Al=9.8)and (■) Cu-FER (Si/Al=6.2). Reprinted from 80 with permission from Elsevier.

Interestingly, a similar absorption band was also observed after contacting Cu-ZSM-5 catalysts with high Cu/Al ratios (Cu/Al>0.25) with O2 at elevated temperatures.72, 81 As dioxygen is consumed in the process, the unique absorption may tentatively be assigned to an O-activated Cu species. Moreover, the active oxygen was found to selectively oxidize methane into methanol in a stoichiometric reaction, starting at 100°C (Figure 6).81, 82 During the reaction with CH4, the 22 700 cm−1 band disappears, indicating that the active Cu core in ZSM-5 is involved in both the catalytic decomposition of nitrogen oxides and the selective oxidation of methane.77, 80 The nature of the active Cu core was investigated in a combined UV-vis, EPR and EXAFS study and the obtained data were suggested to be consistent with a bis(μ-oxo) dicopper(III) core.72, 77 The energy of the absorption band and the Cu-Cu distance of 2.87 Å obtained by EXAFS were used to rule out the presence of a peroxo moiety which typically has longer Cu-Cu distances.83 From the amount of methanol produced, the number of active Cu centers was estimated to be approximately 5% of the total amount of Cu in Cu-ZSM-5, i.e. the species associated with the 22 700 cm−1 is a minority species.81, 82 As EXAFS shows the averaged data for all Cu sites in Cu-ZSM-5, it is not sensitive enough to probe these active Cu sites. As several Cu-oxygen species show absorption features in this region,84-90 no conclusive assignment can be made based on the UV-vis electronic absorption data alone.

Figure 6.

Fiber-optic UV–vis spectra of an O2 calcined (450°C) Cu-ZSM-5 (Si/Al=12, Cu/Al=0.54) during reaction with CH4 at a heating rate of 10 °C/min from RT up to 225 °C. The time interval between two spectra is 1.5 min or a temperature difference of 15 °C. Reprinted from 82 with permission from Elsevier.

Several DFT studies evaluated the possible binuclear Cu species formed in Cu-ZSM-5 upon calcination in O2. From the calculations of Yumura et al. both side-on peroxo and bis(μ-oxo) dicopper cores were found to be energetically favorable in the 10MR of ZSM-5.91 In the work of Goodman et al. and Bell and co-workers, several oxygen bridged binuclear Cu sites were proposed.92-94 In the work of Iwamoto et al.,95 and later others,96-100 an oxygen bridged Cu dimer was suggested to be formed during the auto-reduction of two hydrated Cu2+ cores. Aside from a Cu-Cu contribution in EXAFS data, no other spectroscopic evidence for such a core with bridging oxygen was presented to support the assignment. Computational studies have evaluated several possible core structures. Direct spectroscopic data are required that can selectively probe the active site, even if it is only a minority species. In fact, we have recently used the 22 700 cm−1 absorption band to resonance enhance the Raman vibrations of the catalytic site upon shooting a laser in this absorption band. In these studies the reactive intermediate is unambiguously defined as a bent [Cu-O-Cu]2+ core, a species not previously observed in Cu/O2 chemistry, as the catalytically active species. The details of these spectroscopic studies and the frontier orbitals involved in H-atom abstraction from CH4 are presented in reference 101.

In addition to this Cu core in Cu-ZSM-5, other Cu sites are capable of stoichiometric oxidation of methane in methanol.82 In Cu-MOR a similar absorption feature at 22 000 cm−1 was observed after O2 calcination, although much less intense than that of Cu-ZSM-5. This band also disappeared during reaction with CH4 at 150°C, and methanol was produced. Less active Cu cores were formed in FER and BEA. Here, a reaction temperature of 200°C is required to convert methane into methanol. In MOR, the amount of methanol produced after reaction at 200°C significantly increased, compared to the reaction at 150°C, indicating the presence of an additional core. Thus, while an activated Cu species, corresponding to the 22 700 cm−1 absorption band in ZSM-5 and MOR is capable of oxidizing CH4 at 100°C, another less active but unknown Cu species is present in the FER, BEA and MOR zeolites, that is capable of only oxidizing methane above 200°C.82

4.2 Fe-zeolites

Panov and co-workers reported the formation of the so-called α-O core in Fe-ZSM-5 upon reacting the zeolite with N2O,102-104 suggested to mimic the selective hydroxylation of methane into methanol by the enzyme sMMO.105-107 High temperature treatment in He, vacuum, H2 or steam generates the precursor for this α-O core and is referred to as α-Fe.108-113 Subsequent reaction of the Fe-zeolite with N2O at temperatures between 200 and 250°C results in the formation of α-O, a site capable of selectively oxidizing methane to methanol and benzene to phenol at room temperature. There is consensus that this active site cannot be formed with O2.114-116 Several studies address the comparison and differences between α-O and the active site in sMMO.61, 110, 117, 118 In the past decades, a number of structural assignments, often contradictory, have been made for the α-O and α-Fe sites and no consensus as to its structure has been attained thus far. Part of the controversy is due to the lack of a direct correlation between the reported spectroscopic data to the reactivity of these sites in the oxidation of CH4 or benzene. Based on Mössbauer spectroscopy and EXAFS data, the core was originally assigned to a bis(μ-oxo)diiron core, in analogy with the active site in sMMO.107 Later work suggested the formation of a Fe4+=O intermediate61, 119 or alternatively a Fe3+O.− radical120, 121 or two Fe3+O.− μ-OH bridged sites.113 The formation of an Fe3+O.− radical was tentatively suggested, based on the co-existence of signals at g=6.4 and g=2.018 in the EPR spectrum, assigned to Fe3+ and an O.− radical moiety, respectively.122 However, if an Fe3+-O−. core exists, the S=5/2 of Fe3+ should couple antiferromagnetically with the radical S=1/2, resulting in an overall S=2 ground state, which would not be detectable by X-band EPR spectroscopy at liquid N2 temperatures.123-125 Fe4+=O was ruled out since it would not contribute to the EPR spectrum at liquid N2 temperatures. However, the total amount of spin observed was not quantified with respect to the total Fe content. Thus it is not possible to judge whether the presence of EPR silent Fe centers, such as a Fe4+=O, can be excluded. Assigning these EPR features to the active site was based on their disappearance after interaction with CO at room temperature, but the more direct approach of measuring the EPR spectra after reaction with CH4, was not pursued. In combination with the above mentioned EPR study, X-ray absorption data were collected and presented as inconsistent with an Fe4+ species.120, 121, 126 However, these bulk techniques do not rule out the presence of a minor amount of catalytic Fe4+ in the presence of a large fraction of spectator sites. Thus no data exist that can unambiguously evaluate for the presence or absence of an Fe4+ core or relate it to the reactive α-O species. Recently, attempts have been undertaken to investigate the α-O site with UV-vis absorption and resonance Raman spectroscopy by Li and coworkers,127 and the α-site was tentatively assigned as a peroxo bridged binuclear Fe site, based on the observation of a stretch at 867 cm−1 and an electronic absorption band at 605 nm (16500 cm−1).

Formation of this α-O and the subsequent hydroxylation of CH4 and benzene, could only be achieved after deposition of an O atom from N2O, but not after reaction with O2. Treatment of Fe-ZSM-5 with O2 was studied in the work of Sachtler and co-workers.128 In their Raman study, an adsorbed peroxide species was suggested to be formed bridging two Fe3+ centers. The presence of a peroxo intermediate was concluded based on a Raman feature at 730 cm−1 assigned as the O-O stretching vibration. Distinguishing vibrations involving O motions can be made upon 18O isotopic labeling, as these vibrations shift to lower frequencies. The work of Sachtler and co-workers shows a red shift of 32 cm−1 to 698 cm−1 when the Fe-ZSM-5 is reated with 18O2 confirming the involvement of extra-lattice O motion in the Fe complex. In Fe-zeolites, the presence of Fe dimers is suggested to be reflected by the presence of an absorption band in the 28 000-30 000 cm−1 region,129 but this assignment is debated.126 Interestingly however, a peroxo bridged Fe3+ dimer is suggested in the work of Sachtler as well as in the work of Li and co-workers, although the suggested peroxo stretches at 730 cm−1 and 867 cm−1 are very different.127, 128 More detailed spectroscopic investigation is thus required to further unravel the geometric and electronic structures of the oxygen bridged Fe dimers suggested to be formed from O2 and N2O. If it is in fact the case that both N2O and O2 treatments result in peroxo bridged Fe dimers, as suggested by Li and Sachtler respectively, it is important to understand how the different geometric and electronic structures (resulting in different peroxo stretches) contribute to their different reactivities. Only the N2O-activated form, the α-O (which is not formed with O2), is active in the selective oxidation of CH4 and benzene at room temperature.

O2 treatment of Fe-zeolites does not result in the formation of active sites for selective oxidation of methane and benzene. Rather, activated O2 species in Fe-zeolites catalyze the non-selective oxidation of hydrocarbons into COx and H2O at elevated temperatures (typically at 400°C or higher). This is observed in the selective catalytic reduction (SCR) of NO (similar as in Cu and Co-zeolites). At moderate temperatures (typically between 250-350°C), O2 is beneficial for the SCR of NO. O2 and activated O2 species have been suggested to: i) oxidize NO into NO2 or adsorbed NOy (with y=2,3) species, ii) reoxidize the TMI to its “proper” oxidation state for NO-NO2 conversion and adsorption,130-136 ii) remove carbonaceous deposits137 and, iv) oxidize hydrocarbons into more reactive oxygenated surface intermediates for NO reduction.138 At higher temperatures however, the presence of O2 results in a decreased reduction of NO, resulting in the typically observed volcano shaped conversion curves. The combustion of the hydrocarbons with the activated oxygen species is more dominant at these temperatures leaving less hydrocarbons for the reduction of NOx.40, 139, 140 Little is known, however, on the geometric and electronic structure of the intermediates involved in both the low and high temperature reactions.

4.3 Co and other first-row TMI-zeolites

Other first row transition metal ions, such as Ti, V, Cr and Mn have been reported to be active in either N2O decomposition or selective oxidation reactions. Recently, the presence of an α-O site in Mn-ZSM-5 was suggested after N2O treatment, similar to Fe-ZSM-5. This so called α-O results in the formation of an absorption band in the UV-vis spectra around 18 500 cm−1, and was suggested to be involved in the N2O decomposition in Mn-ZSM-5.141 No reactivity towards hydrocarbons is thus far reported for this species and as is the case for Fe-ZSM-5, the α-O in Mn-ZSM-5 cannot be formed with O2. Although Mn-zeolites have been reported to catalyze the selective oxidation of n-hexane with O2, the role of the Mn sites is not in O2 activation. The proposed role of Mn is rather to regulate the selective decomposition of the hexylhydroperoxo intermediate in this reaction.142 Isomorphously substituted V, Cr and Ti zeolites and mesoporous materials were found to be active in the photocatalytic partial oxidation of hydrocarbons with O2.143, 144 Supported isolated vanadium oxides on SiO2, TiO2, Al2O3 or mesoporous materials are often investigated in the selective oxidation of CH4 or methanol into formaldehyde with O2 at temperature above 400°C.145-151 Isomorphous substitution of Ti in the zeolite lattice, e.g. TS-1 zeolite, results in active catalysts for the liquid-phase catalytic oxidation of a variety of organic compounds with H2O2.

Co exchanged zeolites or Co incorporated in the lattice of AlPO’s has often been reported to be active in the selective oxidation of linear alkanes by O2.152, 153 Co exchanged X, Y zeolite or the mesoporous silica MCM-41 have been found to be active in the epoxidation of styrene with molecular oxygen in the presence of N,N-dimethyl formamide (DMF).154-156 A tentative reaction mechanism was proposed for the O2 oxidation of α-pinene and the epoxidation of styrene by Co exchanged FAU.155, 157 Activation of O2 in the presence of DMF at the Co sites is suggested to occur via a tetrahedrally coordinated CoIII-superoxo complex, with a typical absorption band at 620 nm (16130 cm−1) in the UV-vis absorption spectrum,155 followed by the oxidative addition to the C=C double bond of styrene and α-pinene.

5. Conclusions

This Forum contribution has reviewed the coordination of Cu2+, Fe3+ and Co2+ to surface oxygens in zeolites, as derived from spectroscopic and theoretical studies, the formation of activated oxygen species and their role in selective oxidation reactions. At low loadings, the coordination of the TMI is reasonably well understood. Cu2+ is found to coordinate in 6MR, distorting the ring in such a way as to obtain 4-fold coordination. In the case of Co2+, it can have 3-5 fold coordination. The resulting site distortion depends on the amount of Al tetrahedra making up that site. Thus, a TMI in one crystallographic exchange site can have several spectroscopic signatures, depending on the number of Al tetrahedra. As a result, both the crystallographic position of the exchange site and the number of Al tetrahedra making up the site determine the spectroscopic signature and thus the geometric and electronic structure of the TMI in that site.

Increasing the TMI loading increases the heterogeneity of the TMI species formed at the zeolite surface. This can result in the formation of di- and oligomeric species, requiring extra-lattice ligands (water, hydroxo and oxo ligands). Removal of these ligands during high temperature pretreatments can result in auto-reduction of the TMI as confirmed by XANES and UV-vis studies. Several mechanisms for auto-reduction have been suggested. However decisive spectroscopic evidence for the proposed intermediates is lacking.

The reduced TMI sites possess interesting properties. At room temperature, O2 is only weakly adsorbed in most zeolites, but superoxo complexes have been reported to be formed with Cu+ and Cr2+ in zeolite A. High temperature treatment in O2 leads to the formation a catalytically interesting core in Cu-ZSM-5, characterized by a distinct absorption band around 22 700 cm−1. A recent resonance Raman studied allowed assignment of this active site as a bent [Cu-O-Cu]2+ core.101 This species, corresponding to only about 5% of the total amount of Cu, is the crucial intermediate in both the direct decomposition of NO and N2O and the selective oxidation of methane into methanol in a stoichiometric reaction. Other Cu-zeolites, not containing this species, are also active in the selective oxidation of methane into methanol, but at higher temperature. Research is now directed toward: i) further understanding the electronic and geometric structure and reactivity of the bent [Cu-O-Cu]2+ core in the oxygen-activated Cu-ZSM-5 ii) obtaining more information on active sites in other Cu-zeolites; iii) devising a catalytic cycle for the methane-to-methanol conversion with Cu and Fe–zeolites, and iv) increasing the number of active sites.

An activated oxygen species, called α-oxygen, is formed in Fe-ZSM-5. There is a lot of speculation as to the nature of this α-oxygen species. All involve mononuclear and binuclear Fe-oxo species. Its definitive spectroscopic characterization and assignment is also lacking. Consensus however does exist on its role in the selective oxidation of methane and benzene into methanol and phenol, respectively, at room temperature. The hydroxylation of benzene was converted in a catalytic system upon increasing the reaction temperature, favoring the desorption of phenol. In the reaction with CH4, increasing the temperature results in the decomposition of methanol into CO2 and H2O, as is the case in O2 activated Cu-ZSM-5. In contrast to Cu-ZSM-5 however, this reactive α-oxygen in Fe-ZSM-5 cannot be formed with O2 (i.e. only with N2O).

Treatment of Co-exchanged FAU with O2 is suggested to result in the formation of a CoIII-superoxo complex in FAU zeolite based on an absorption band at 620 nm. This superoxo species is found to be active in the epoxidation of styrene and the oxidation of α-pinene. Additional spectroscopic studies are needed to obtain insight into this O2-formed active CoIII site and the molecular mechanism of these reactions.

Overall, O2 activation depends on the interplay of structural factors such as zeolite type, size of the channels and cages and chemical factors such as Si/Al ratio and nature, charge and distribution of the cations. Spectroscopic techniques capable of selectively probing the active sites, even though they constitute only a minor fraction of the total amount of TMI sites, are thus required. The fundamental knowledge of the active site obtained from such studies can provide detailed mechanistic insight and assist in the design and development of novel selective oxidation catalysts.

Acknowledgments

P.J.S. acknowledges the I.W.T. and K.U. Leuven for graduate and post-doctoral fellowships and J.S.W acknowledges the NIH for a traineeship. This research was supported by the G.O.A. and the Long Term Structural Funding-Methusalem Funding by the Flemish Government (R.A.S., B.F.S.) and NIH Grant DK-31450 (E.I.S.).

References

- 1.Breck DW. Zeolite Molecular Sieves. Wiley & Sons; New York: 1974. p. 771. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shen DM, Bulow M, Siperstein F, Engelhard M, Myers AL. Adsorption. 2000;6:275–286. [Google Scholar]

- 3.McKee DW. US:3140933 US patent. 1964

- 4.Yang RT, Chen YD, Peck JD, Chen N. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 1996;35:3093–3099. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dunne JA, Mariwals R, Rao M, Sircar S, Gorte RJ, Myers AL. Langmuir. 1996;12:5888–5895. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chao CC. EP0,297,542,A2 Eur. Patent. 1983

- 7.Jousse F, DeLara EC. J. Phys. Chem. 1996;100:233–237. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jousse F, Larin AV, DeLara EC. J. Phys. Chem. 1996;100:238–244. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xu J, Mojet BL, van Ommen JG, Lefferts L. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2005;109:18361–18368. doi: 10.1021/jp052941+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Santra S, Archipov TE, Augusta B, Komnik H, Stoll H, Roduner E, Rauhut G. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2009 doi: 10.1039/b904152d. DOI: 10.1039/b904152d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klier K. Langmuir. 1988;4:13–25. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kellerman R, Hutta PJ, Klier K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1974;96:5946–5947. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kellerman R, Klier K. In: Molecular Sieves -II. Katzer JR, editor. Vol. 40. American Chemical Society; Washington, DC: 1977. p. 120. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lange JP, Klier K. Zeolites. 1994;14:462–468. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vansant EF, Lunsford JH. J. Phys. Chem. 1972;76:2860. &. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lunsford J. ACS Symp. Ser. 1977;40:473. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schoonheydt RA, Pelgrims J. J. Chem. Soc., Dalton Trans. 1981:914–922. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Devos DE, Knops-Gerrits PP, Parton RF, Weckhuysen BM, Jacobs PA, Schoonheydt RA. J.Incl. Phenom. Mol. Recognit. Chem. 1995;21:185–213. [Google Scholar]

- 19.De Vos DE, Dams M, Sels BF, Jacobs PA. Chem. Rev. 2002;102:3615–3640. doi: 10.1021/cr010368u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Corma A, Garcia H. Chem. Rev. 2002;102:3837–3892. doi: 10.1021/cr010333u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ratnasamy P, Srinivas D. Catal. Today. 2009;141:3–11. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Corma A. Chem. Rev. 1997;97:2373–2419. doi: 10.1021/cr960406n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Punniyamurthy T, Velusamy S, Iqbal J. Chem. Rev. 2005;105:2329–2363. doi: 10.1021/cr050523v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Viswanathan B, Jacob B. Catal. Rev. 2005;47:1–82. [Google Scholar]

- 25.van Bekkum H, Flanigen E, Jacobs PA, Jansen JC. Introduction to Zeolite Science and Practice. 2nd ed Elsevier; Amsterdam: 2001. p. 1018. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baerlocher C, McCusker LB. Database of Zeolite Structures. http://www.iza-structure.org/databases/

- 27.Treacy MMJ, Higgins JB. Collection of Simulated XRD Powder Patterns for Zeolites. 5th ed Elsevier; Amsterdam: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jacobs PA, Martens JA, van Bekkum EMFH, Jansen JC. Studies in Surface Science and Catalysis. Vol. Volume 58. Elsevier; 1991. Introduction to Acid Catalysis with Zeolites in Hydrocarbon Reactions; pp. 445–496. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smeets PJ, Sels BF, van Teeffelen RM, Leeman H, Hensen EJM, Schoonheydt RA. J. Catal. 2008;256:183–191. [Google Scholar]

- 30.De Vos DE, Sels BF, Jacobs PA. Adv. Catal. 2001;46:1–87. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Notari B. Innovation in Zeolite Materials Science. In: Grobet PJ, Mortier WJ, Vansant EF, Schulz-Ekloff G, editors. Stud. Surf. Sci. Catal. Vol. 37. Elsevier; Amsterdam: 1988. p. 413. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Clerici MG, Romano U. EP100,119,A1 Eur. Patent. 1983

- 33.Bellusi G, Giusti A, Esposito A, Buonomo F. EP226,257,A2 Eur. Patent. 1987

- 34.Pirngruber G. The fascinating chemistry of iron- and copper-containing zeolites. In: Valtchev V, Mintova S, Tsapatsis M, editors. Ordered Porous Materials. Elsevier; Amsterdam: 2008. p. 733. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mortier WJ. Compilation of extra framework sites in zeolites. Butterworth Sci. Ltd.; Guildford: 1982. p. 67. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Karge HG, Zhang Y, Beyer HK. Catal. Lett. 1992;12:147–156. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weitkamp J, Ernst S, Bock T, Kromminga T, Kiss A, Kleinschmit P. US:5545784 US Patent. 1994

- 38.Sulikowski B, Find J, Karge HG, Herein D. Zeolites. 1997;19:395–403. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Iwamoto M, Yahiro H, Mine Y, Kagawa S. Chem. Lett. 1989:213–216. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Smeets PJ, Meng QG, Corthals S, Leeman H, Schoonheydt RA. Appl. Catal. B. 2008;84:505–513. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wichterlova B, Dedecek J, Sobalik Z. Catalysis by Unique Metal Ion Structures in Solid Matrices: From Science to Application. 2001;13:31–53. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dedecek J, Wichterlova B. J. Phys. Chem. B. 1999;103:1462–1476. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kaucky D, Dedecek JI, Wichterlova B. Microporous Mesoporous Mat. 1999;31:75–87. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dedecek J, Kaucky D, Wichterlova B. Microporous Mesoporous Mat. 2000;35-6:483–494. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dedecek J, Kaucky D, Wichterlova B, Gonsiorova O. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2002;4:5406–5413. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Drozdova L, Prins R, Dedecek J, Sobalik Z, Wichterlova B. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2002;106:2240–2248. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Verberckmoes AA, Weckhuysen BM, Pelgrims J, Schoonheydt RA. J. Phys. Chem. 1995;99:15222–15228. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Verberckmoes AA, Weckhuysen BM, Schoonheydt RA. Microporous Mesoporous Mat. 1998;22:165–178. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Groothaert MH, Pierloot K, Delabie A, Schoonheydt RA. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2003;5:2135–2144. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schoonheydt RA. Catal. Rev. 1993;35:129–168. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pierloot K, Delabie A, Verberckmoes A, Schoonheydt R. The Interplay between DFT and Conventional Quantum Chemistry: Coordination of Transition Metal Ions to Six-Rings in Zeolites. In: De Proft F, Langenaeker W, editors. Density Functional Theory, a bridge between chemistry and physics Geerlings. VUB University Press; Brussels: 1999. p. 169. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pierloot K, Delabie A, Groothaert MH, Schoonheydt RA. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2001;3:2174–2183. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Delabie A, Pierloot K, Groothaert MH, Weckhuysen BM, Schoonheydt RA. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2002;4:134–145. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Delabie A, Pierloot K, Groothaert MH, Schoonheydt RA, Vanquickenborne LG. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2002:515–530. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pierloot K, Delabie A, Ribbing C, Verberckmoes AA, Schoonheydt RA. J. Phys. Chem. B. 1998;102:10789–10798. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Verberckmoes A, Schoonheydt R, Ceulemans A, Delabie A, Pierloot K. Semi-emperical and ab-initio Calculations of the Spectroscopic properties of Co(II) coordinated in Zeolite A. In: Treacy M, Marcus B, Bisher M, Higgins J, editors. Proceed. of the 12th International Zeolite Conference; Warrendale: Materials Research Society; 1999. p. 387. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Klier K, Hutta PJ, Kellerman R. In: In Molecular Sieves -II. Katzer JR, editor. Vol. 40. American Chemical Society; Washington, DC: 1977. p. 108. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Klier K. Electronic structure of transition-metal ion containing zeolites. In: Centi G, Bell AT, Wichterlova B, editors. Catalysis by Unique Metal Structures in Solid Matrices– From Science to Applications. Kluwer Academic Press; Dordrecht: 2001. p. 115. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Schoonheydt RA. J. Phys. Chem. Solids. 1989;50:523–539. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Perez-Ramirez J, Mul G, Kapteijn F, Moulijn JA, Overweg AR, Domenech A, Ribera A, Arends I. J. Catal. 2002;207:113–126. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zecchina A, Rivallan M, Berlier G, Lamberti C, Ricchiardi G. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2007;9:3483–3499. doi: 10.1039/b703445h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lobree LJ, Hwang IC, Reimer JA, Bell AT. J. Catal. 1999;186:242–253. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Joyner R, Stockenhuber M. J. Phys. Chem. B. 1999;103:5963–5976. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Heijboer WM, Battiston AA, Knop-Gericke A, Havecker M, Mayer R, Bluhm H, Schlogl R, Weckhuysen BM, Koningsberger DC, de Groot FMF. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2003;107:13069–13075. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Battiston AA, Bitter JH, de Groot FMF, Overweg AR, Stephan O, van Bokhoven JA, Kooyman PJ, van der Spek C, Vanko G, Koningsberger DC. J. Catal. 2003;213:251–271. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Marturano P, Drozdova L, Pirngruber GD, Kogelbauer A, Prins R. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2001;3:5585–5595. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Heijboer WM, Battiston AA, Knop-Gericke A, Havecker M, Bluhm H, Weckhuysen BM, Koningsberger DC, de Groot FMF. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2003;5:4484–4491. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Garten RL, Delgass WN, Boudart M. J. Catal. 1970;18:90–107. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Larsen SC, Aylor A, Bell AT, Reimer JA. J. Phys. Chem. 1994;98:11533–11540. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Iwamoto M, Yahiro H, Tanda K, Mizuno N, Mine Y, Kagawa S. J. Phys. Chem. 1991;95:3727–3730. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Jacobs PA, Beyer HK. J. Phys. Chem. 1979;83:1174–1177. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Groothaert MH, van Bokhoven JA, Battiston AA, Weckhuysen BM, Schoonheydt RA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:7629–7640. doi: 10.1021/ja029684w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kau LS, Spirasolomon DJ, Pennerhahn JE, Hodgson KO, Solomon EI. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1987;109:6433–6442. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Nachtigallova D, Nachtigall P, Sierka M, Sauer J. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 1999;1:2019–2026. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Nachtigall P, Nachtigallova D, Sauer J. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2000;104:1738–1745. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Nachtigallova D, Nachtigall P, Sauer J. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2001;3:1552–1559. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Groothaert MH, Lievens K, Leeman H, Weckhuysen BM, Schoonheydt RA. J. Catal. 2003;220:500–512. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Dandekar A, Vannice MA. Appl. Catal. B. 1999;22:179–200. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kapteijn F, Marban G, RodriguezMirasol J, Moulijn JA. J. Catal. 1997;167:256–265. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Smeets PJ, Groothaert MH, van Teeffelen RM, Leeman H, Hensen EJM, Schoonheydt RA. J. Catal. 2007;245:358–368. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Groothaert MH, Smeets PJ, Sels BF, Jacobs PA, Schoonheydt RA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:1394–1395. doi: 10.1021/ja047158u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Smeets PJ, Groothaert MH, Schoonheydt RA. Catal. Today. 2005;110:303–309. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Tyeklar Z, Jacobson RR, Wei N, Murthy NN, Zubieta J, Karlin KD. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993;115:2677–2689. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Baldwin MJ, Ross PK, Pate JE, Tyeklar Z, Karlin KD, Solomon EI. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991;113:8671–8679. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Baldwin MJ, Root DE, Pate JE, Fujisawa K, Kitajima N, Solomon EI. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1992;114:10421–10431. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Mahapatra S, Halfen JA, Wilkinson EC, Pan GF, Cramer CJ, Que L, Tolman WB. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995;117:8865–8866. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Root DE, Mahroof-Tahir M, Karlin KD, Solomon EI. Inorg. Chem. 1998;37:4838–4848. doi: 10.1021/ic980606c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Chen P, Fujisawa K, Solomon EI. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122:10177–10193. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Chen P, Root DE, Campochiaro C, Fujisawa K, Solomon EI. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:466–474. doi: 10.1021/ja020969i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Maiti D, Fry HC, Woertink JS, Vance MA, Solomon EI, Karlin KD. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:264–265. doi: 10.1021/ja067411l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Yumura T, Takeuchi M, Kobayashi H, Kuroda Y. Inorg. Chem. 2009;48:508–517. doi: 10.1021/ic8010184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Rice MJ, Chakraborty AK, Bell AT. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2000;104:9987–9992. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Goodman BR, Schneider WF, Hass KC, Adams JB. Catal. Lett. 1998;56:183–188. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Goodman BR, Hass KC, Schneider WF, Adams JB. J. Phys. Chem. B. 1999;103:10452–10460. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Iwamoto M, Furukawa H, Mine Y, Uemura F, Mikuriya SI, Kagawa S. J. Chem Soc. Chem. Commun. 1986:1272–1273. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Sarkany J, Ditri JL, Sachtler WMH. Catal. Lett. 1992;16:241–249. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Da Costa P, Moden B, Meitzner GD, Lee DK, Iglesia E. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2002;4:4590–4601. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Palomino GT, Fisicaro P, Bordiga S, Zecchina A, Giamello E, Lamberti C. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2000;104:4064–4073. doi: 10.1021/jp993893u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Xamena F, Fisicaro P, Berlier G, Zecchina A, Palomino GT, Prestipino C, Bordiga S, Giamello E, Lamberti C. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2003;107:7036–7044. [Google Scholar]

- 100.Grunert W, Hayes NW, Joyner RW, Shpiro ES, Siddiqui MRH, Baeva GN. J. Phys. Chem. 1994;98:10832–10846. [Google Scholar]

- 101.Woertink JS, Smeets PJ, Groothaert MH, Vance MA, Sels BF, Schoonheydt RA, Solomon EI. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:18908–18913. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910461106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Panov GI, Sobolev VI, Kharitonov AS. J. Mol. Catal. 1990;61:85–97. [Google Scholar]

- 103.Panov GI, Sheveleva GA, Kharitonov AS, Romannikov VN, Vostrikova LA. Appl. Catal. A. 1992;82:31–36. [Google Scholar]

- 104.Sobolev VI, Kharitonov AS, Paukshtis YA, Panov GI. J. Mol. Catal. 1993;84:117–124. [Google Scholar]

- 105.Dubkov KA, Sobolev VI, Talsi EP, Rodkin MA, Watkins NH, Shteinman AA, Panov GI. J. Mol. Catal. A. 1997;123:155–161. [Google Scholar]

- 106.Dubkov KA, Sobolev VI, Panov GI. Kinet. Catal. 1998;39:72–79. [Google Scholar]

- 107.Ovanesyan NS, Shteinman AA, Dubkov KA, Sobolev VI, Panov GI. Kinet. Catal. 1998;39:792–797. [Google Scholar]

- 108.Kubanek P, Wichterlova B, Sobalik Z. J. Catal. 2002;211:109–118. [Google Scholar]

- 109.Ribera A, Arends I, de Vries S, Perez-Ramirez J, Sheldon RA. J. Catal. 2000;195:287–297. [Google Scholar]

- 110.Knops-Gerrits PP, Goddard WA. J. Mol. Catal. A. 2001;166:135–145. [Google Scholar]

- 111.Hensen EJM, Zhu Q, Hendrix M, Overweg AR, Kooyman PJ, Sychev MV, van Santen RA. J. Catal. 2004;221:560–574. [Google Scholar]

- 112.Sun KQ, Zhang HD, Xia H, Lian YX, Li Y, Feng ZC, Ying PL, Li C. Chem. Commun. 2004:2480–2481. doi: 10.1039/b408854a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Dubkov KA, Ovanesyan NS, Shteinman AA, Starokon EV, Panov GI. J. Catal. 2002;207:341–352. [Google Scholar]

- 114.Ivanov AA, Chernyavsky VS, Gross MJ, Kharitonov AS, Uriarte AK, Panov GI. Appl. Catal. A. 2003;249:327–343. [Google Scholar]

- 115.Yuranov I, Bulushev DA, Renken A, Kiwi-Minsker L. J. Catal. 2004;227:138–147. [Google Scholar]

- 116.Roy PK, Pirngruber GD. J. Catal. 2004;227:164–174. [Google Scholar]

- 117.Ovanesyan NS, Sobolev VI, Dubkov KA, Panov GI, Shteinman AA. Russ. Chem. Bull. 1996;45:1509–1510. [Google Scholar]

- 118.Shilov AE, Shteinman AA. Accounts of Chemical Research. 1999;32:763–771. [Google Scholar]

- 119.Jia JF, Sun Q, Wen B, Chen LX, Sachtler WMH. Catal. Lett. 2002;82:7–11. [Google Scholar]

- 120.Pirngruber GD, Grunwaldt JD, van Bokhoven JA, Kalytta A, Reller A, Safonova OV, Glatzel P. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2006;110:18104–18107. doi: 10.1021/jp063812b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Pirngruber GD, Grunwaldt JD, Roy PK, van Bokhoven JA, Safonova O, Glatzel P. Catal. Today. 2007;126:127–134. [Google Scholar]

- 122.Berrier E, Ovsitser O, Kondratenko EV, Schwidder M, Grunert W, Bruckner A. J. Catal. 2007;249:67–78. [Google Scholar]

- 123.Neidig ML, Decker A, Choroba OW, Huang F, Kavana M, Moran GR, Spencer JB, Solomon EI. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:12966–12973. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605067103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Solomon EI, Wong SD, Liu LV, Decker A, Chow MS. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2009;13:99–113. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2009.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Krzystek J, England J, Ray K, Ozarowski A, Smirnov D, Que L, Telser J. Inorg. Chem. 2008;47:3483–3485. doi: 10.1021/ic800411c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Pirngruber GD, Roy PK, Prins R. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2006;8:3939–3950. doi: 10.1039/b606205a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Xia HA, Sun KQ, Sun KJ, Feng ZC, Li WX, Li C. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2008;112:9001–9005. [Google Scholar]

- 128.Gao ZX, Kim HS, Sun Q, Stair PC, Sachtler WMH. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2001;105:6186–6190. [Google Scholar]

- 129.Capek L, Kreibich V, Dedecek J, Grygar T, Wichterlova B, Sobalik Z, Martens JA, Brosius R, Tokarova V. Microporous Mesoporous Mat. 2005;80:279–289. [Google Scholar]

- 130.Hamada H, Kintaichi Y, Sasaki M, Ito T, Tabata M. Appl. Catal. 1991;70:L15–L20. [Google Scholar]

- 131.Komatsu T, Nunokawa M, Moon IS, Takahara T, Namba S, Yashima T. J. Catal. 1994;148:427–437. [Google Scholar]

- 132.Ham SW, Choi H, Nam IS, Kim YG. Catal. Lett. 1996;42:35–40. [Google Scholar]

- 133.Eng J, Bartholomew CH. J. Catal. 1997;171:27–44. [Google Scholar]

- 134.Schay Z, James VS, Pal-Borbely G, Beck A, Ramaswamy AV, Guczi L. J. Mol. Catal. A. 2000;162:191–198. [Google Scholar]

- 135.Delahay R, Kieger S, Tanchoux N, Trens P, Coq B. Appl. Catal. B. 2004;52:251–257. [Google Scholar]

- 136.Sjovall H, Olsson L, Fridell E, Blint R. J. Appl. Catal. B. 2006;64:180–188. [Google Scholar]

- 137.d’Itri JL, Sachtler WMH. Appl. Catal. B. 1993;2:L7–L15. [Google Scholar]

- 138.Montreuil CN, Shelef M. Appl. Catal. B. 1992;1:L1–L8. [Google Scholar]

- 139.Chen HY, Voskoboinikov T, Sachtler WMH. J. Catal. 1999;186:91–99. [Google Scholar]

- 140.Parvulescu VI, Grange P, Delmon B. Catal. Today. 1998;46:233–316. [Google Scholar]

- 141.Radu D, Glatzel P, Gloter A, Stephan O, Weckhuysen BM, de Groot FMF. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2008;112:12409–12416. [Google Scholar]

- 142.Zhan BZ, Moden B, Dakka J, Santiesteban JG, Iglesia E. J. Catal. 2007;245:316–325. [Google Scholar]

- 143.Anpo M, Kim TH, Matsuoka M. Catal. Today. 2009;142:114–124. [Google Scholar]

- 144.Hu Y, Wada N, Tsujimaru K, Anpo M. Catal. Today. 2007;120:139–144. [Google Scholar]

- 145.Herman RG, Sun Q, Shi CL, Klier K, Wang CB, Hu HC, Wachs IE, Bhasin MM. Catal. Today. 1997;37:1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 146.Bronkema JL, Bell AT. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2007;111:420–430. [Google Scholar]

- 147.Berndt H, Martin A, Bruckner A, Schreier E, Muller D, Kosslick H, Wolf GU, Lucke B. J. Catal. 2000;191:384–400. [Google Scholar]

- 148.Koranne MM, Goodwin JG, Marcelin G. J. Catal. 1994;148:378–387. [Google Scholar]

- 149.Parmaliana A, Arena F. J. Catal. 1997;167:57–65. [Google Scholar]

- 150.Baltes M, Cassiers K, Van Der Voort P, Weckhuysen BM, Schoonheydt RA, Vansant EF. J. Catal. 2001;197:160–171. doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2004.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Deo G, Wachs IE. J. Catal. 1994;146:323–334. [Google Scholar]

- 152.Thomas JM, Raja R, Sankar G, Bell RG. Nature. 1999;398:227–230. [Google Scholar]

- 153.Thomas JM. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1999;38:3589–3628. [Google Scholar]

- 154.Tang QH, Wang Y, Liang J, Wang P, Zhang QH, Wan HL. Chem. Commun. 2004:440–441. doi: 10.1039/b314864e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Sebastian J, Jinka KM, Jasra RV. J. Catal. 2006;244:208–218. [Google Scholar]

- 156.Tang QH, Zhang QH, Wu HL, Wang Y. J. Catal. 2005;230:384–397. [Google Scholar]

- 157.Patil MV, Yadav MK, Jasra RV. J. Mol. Catal. A. 2007;277:72–80. [Google Scholar]