Abstract

Study Objectives:

A reduction in core temperature and an increase in the distal-proximal skin gradient (DPG) are reported to be associated with shorter sleep onset latencies (SOL) and better sleep quality. Ramelteon is a melatonin MT-1/MT-2 agonist approved for the treatment of insomnia. At night, ramelteon has been reported to shorten SOL. In the present study we tested the hypothesis that ramelteon would reduce core temperature, increase the DPG, as well as shorten SOL, reduce wakefulness after sleep onset (WASO), and increase total sleep time (TST) during a daytime sleep opportunity.

Design:

Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, cross-over design. Eight mg ramelteon or placebo was administered 2 h prior to a 4-h daytime sleep opportunity.

Setting:

Sleep and chronobiology laboratory.

Participants:

Fourteen healthy adults (5 females), aged (23.2 ± 4.2 y).

Measurements and Results:

Primary outcome measures included core body temperature, the DPG and sleep physiology (minutes of total sleep time [TST], wake after sleep onset [WASO], and SOL). We also assessed as secondary outcomes, proximal and distal skin temperatures, sleep staging and subjective TST. Repeated measures ANOVA revealed ramelteon significantly reduced core temperature and increased the DPG (both P < 0.05). Furthermore, ramelteon reduced WASO and increased TST, and stages 1 and 2 sleep (all P < 0.05). The change in the DPG was negatively correlated with SOL in the ramelteon condition.

Conclusions:

Ramelteon improved daytime sleep, perhaps mechanistically in part by reducing core temperature and modulating skin temperature. These findings suggest that ramelteon may have promise for the treatment of insomnia associated with circadian misalignment due to circadian sleep disorders.

Citation:

Markwald RR; Lee-Choing TL; Burke TM; Snider JA; Wright KP. Effects of the melatonin MT-1/MT-2 agonist ramelteon on daytime body temperature and sleep. SLEEP 2010;33(6):825-831

Keywords: Ramelteon, body temperature, melatonin agonist, daytime sleep, thermoregulation

INSOMNIA IS A COMMON SYMPTOM OF CIRCADIAN SLEEP DISORDERS.1 CIRCADIAN SLEEP DISORDERS ARE A SPECIAL CLASS OF SLEEP DISORDERS THAT are often associated with misalignment between internal biological time and the desired or imposed sleep-wakefulness schedule.1–3 The resulting circadian misalignment leads to sleep occurring at an internal biological time when the circadian clock is promoting wakefulness. Humans usually initiate sleep on the downward slope of the circadian body temperature rhythm,4 when the rate of change of core temperature and peripheral heat loss are maximal and when endogenous levels of melatonin begin to rise.5,6 A close temporal relationship between sleep and core body temperature (CBT) has been found, such that sleep is optimal during the biological night when CBT is low and endogenous melatonin levels are high.4,6,7

Administration of exogenous melatonin during the biological day, when endogenous melatonin levels are low, has been shown to reduce CBT,8–11 increase peripheral heat loss,12–15 and improve sleep.16 The increase in peripheral heat loss is reported to be negatively correlated with sleep onset latency (SOL).17–19 Heat loss following exogenous melatonin administration has been primarily determined by measuring skin temperature levels at the hands and feet13,20,21 and by calculating the distal-proximal gradient (DPG) in skin temperature.18 The DPG was first developed by subtracting fingertip temperature from a site on the forearm22 and has been modified by others18,23 to be calculated as the difference in distal skin temperature sites on the hands and feet minus skin temperature levels at proximal sites, such as the chest. The sensitivity of the DPG method has been tested in a number of thermoregulatory challenges.24 Heat loss has also been assessed through thermo-imaging of the palmar and dorsal surfaces of the hand and fingers21 and measurement of cutaneous blood flow.12,13,25 During the biological night, exogenous melatonin administration decreases SOL with little effect on sleep architecture26; whereas during the biological day, exogenous melatonin administration decreases SOL10,27–29 and wakefulness after sleep onset (WASO)9 and increases total sleep time (TST).9,27,30

Ramelteon is a sleep promoting therapeutic approved for the treatment of insomnia that acts specifically on melatonin MT-1 and MT-2 receptors with a greater affinity and a longer half-life than melatonin at these receptors.31 Additionally, ramelteon has no affinity for the cytosolic MT-3 receptor.31 At night, ramelteon has been reported to decrease SOL and thereby increase TST in healthy sleepers on the first night sleeping in a novel environment.32 Ramelteon was also reported to decrease SOL in older adults with chronic insomnia over 5 weeks of treatment.33 Further, a 6-month study showed that nightly ramelteon administration reduced both electroencephalographic (EEG) determined latency to persistent sleep as well as subjective SOL in adults with chronic primary insomnia.34

The influence of ramelteon on thermoregulatory physiology and daytime sleep in humans is unknown. If improvements in daytime sleep following ramelteon are associated with decreases in CBT and increases in peripheral heat loss, such findings may provide information regarding possible physiological mechanisms by which ramelteon improves sleep during the biological day. Furthermore, showing the efficacy of ramelteon for improving sleep during the biological day would provide support for testing the application of ramelteon in the treatment of insomnia due to circadian sleep disorders (e.g., jet lag, shift work, delayed sleep phase). Therefore, we tested the hypothesis that ramelteon (8 mg) would reduce CBT and increase DPG under controlled bed rest conditions, as well as decrease SOL and WASO and increase TST in a daytime sleep opportunity. We also hypothesized that a greater change in DPG would be associated with a shorter SOL.

METHODS

Subjects

Fourteen healthy adults (5 females; age 23.2 ± 4.2 y (mean ± SD), body mass index 22.5 ± 2.7 kg/m2) participated. Women were studied during the follicular phase of the menstrual cycle to control for effects of decreased responsiveness to daytime melatonin administration during the luteal phase.35 Participants underwent a medical evaluation at the Clinical and Translational Research Center (CTRC) at the University of Colorado–Boulder. Participants were admitted into the study if they were free of any medical conditions as determined by medical and psychiatric history, physical examination, blood chemistries, 12-lead clinical electrocardiogram, and urine toxicology for drug use. Exclusion criteria were: current smoker; living at Denver/Boulder altitude (1600 m) < 1 year; known medical, psychiatric, or sleep disorder; habitual sleep duration < 6 h or > 9 h, and taking any medication. Study procedures were approved by the University of Colorado–Boulder IRB and the Scientific Advisory and Review Committee of the CTRC. Participants gave written informed consent, and all procedures were performed according to the Declaration of Helsinki.

Study Design

A randomized, within-subject, crossover, placebo-controlled research design was used, in which participants spent 2 separate days in the laboratory separated by one week. Both visits occurred on the same day of the week. Each laboratory visit was preceded by a one-week consistent sleep-wakefulness schedule, verified by call-ins to a time-stamped recorder, actigraphy recordings (Actiwatch-L, Mini Mitter Respironics, Bend, OR), and sleep logs. Participants refrained from caffeine, nicotine, and over-the-counter drugs. Urine toxicology and breath alcohol testing (Lifeloc Technologies Model FC10, Wheat Ridge, CO) verified participants were free of drugs each visit.

Ramelteon and placebo administration were double-blind. Computerized implementation of treatment allocation was performed by the CTRC pharmacist who provided pills identical in appearance in numbered containers. Participants received either ramelteon or rice-powder filled placebo pills on the first visit with the alternate condition administered on the second visit. The allocation sequence was concealed until interventions were assigned and data prepared for statistical analysis.

Experimental Procedures

Participants were admitted ∼1 h 50 min after their habitual wake time to control for circadian phase within individuals between visits. Shortly after arrival to the lab, participants were prepared for polysomnography (PSG) and temperature physiology recordings. Participants were studied using a modified constant routine protocol in which they remained awake, seated in a semi-recumbent position in a hospital bed with the head raised at ∼35 degrees. Participants were studied in sound attenuated and temperature controlled rooms, under dim light conditions (< 8 lux maximum), and in an environment free of time cues. One exception to the latter was that participants were informed in the consent form that they would be asked to sit in bed awake for ∼4 h out of each ∼10 h study visit. Throughout the protocol, participants wore light tee shirts, and blankets covered them up to the waistline to provide similar microclimate conditions at the skin temperature recording sites. A prepared lunch was given of the same quantity and dietary composition for both visits to control for the thermoregulatory effects of digestion and absorption. The lunch was served at the same time each visit and occurred 1 h 45 min prior to pill administration. The timing of the meal was designed so that ramelteon would be rapidly absorbed and to reduce effects of hunger on the subsequent sleep episode. Core and skin temperature physiology and daytime sleep measurements were performed during the biological day on the circadian rise of the CBT rhythm. Core and skin temperature recordings began ∼2.5 h following habitual wake time. Ramelteon or placebo was administered after 2 h sitting in bed. Two hours after drug administration, the bed was lowered to the supine position, and the lights were turned off for a 4-h sleep opportunity (Figure 1). If participants awoke before the end of the sleep opportunity, they were instructed to continue lying in bed and try to sleep.

Figure 1.

Protocol timeline

Protocol events were scheduled according to habitual bed and wake times. The example shows a protocol for a participant with a habitual wake time of 07:00. Participants were admitted to the laboratory ∼1 h 50 min after their scheduled wake time. Pill administration is denoted by the arrow and occurred 2 h after admission and 2 h prior to the 4-h sleep opportunity.

Temperature Recording

Core temperature was measured via an ingested temperature pill that transmitted internal temperature by radio frequency to an external unit placed around the participant's waist (Vital Sense, Mini Mitter Respironics, Bend, OR). Proximal and distal skin temperatures were measured via thermopatches placed inferior to the left clavicle, at the location of the subclavian vein (Tsub), and the left dorsal foot (Tft) respectively. The DPG was calculated as the difference between the (Tft) and the (Tsub) thermopatches. Core and skin body temperatures were analyzed for 2.67 h prior to the PSG recorded sleep opportunity.

Polysomnographic Recording

Sleep recordings were obtained with Siesta digital sleep recorders (Compumedics USA Ltd, Charlotte, NC) using monopolar EEG channels referenced to contralateral mastoids according to the International 10-20 system (C3-A2, C4-A1, O1-A2 and F3-A2), right and left electroculograms (EOG), chin electromyogram (EMG), and electrocardiogram (ECG). Impedances were < 5 k ohms. Data were stored and sampled at a rate of 256 samples/ sec/ channel with a 12-bit A-D board. High-pass and low-pass digital filters for EEG and EOG were set at 0.10 Hz and 30 Hz, respectively. High-pass and low-pass digital filters for EMG were set at 10 and 100 Hz, respectively. Sleep was scored according to standard guidelines from brain region C3-A2.36 SOL was defined as the time from lights out to the onset of 3 continuous epochs of EEG-defined sleep. Subjective TST was assessed immediately after each sleep opportunity. One participant did not provide a subjective assessment of TST and was therefore not included in that analysis.

Data Analysis

Actigraphic analysis of sleep the week prior to each visit verified a similar amount of sleep between conditions with an average difference in TST of 0.01 h (± 0.30 SD).

The primary outcome variables for body temperature were CBT and the DPG. Post hoc analyses were also performed on Tsub and Tft. Data for each body temperature measure were averaged into 10-minute bins. Differences from pill administration were calculated for DPG measures to control for between-subject differences in the baseline distal skin temperature level. Data from 2 individuals were not used for the CBT analysis because of temperature pill malfunction. There were missing data for one individual for Tsub and 4 individuals for Tft because of technical difficulties. The 4 individuals who did not have Tft data were consequently not included in the DPG analysis. The allocation sequence resulted in a balanced design, despite these missing data. The primary outcome variables for sleep were TST, WASO, and SOL.

The effects of ramelteon versus placebo on each of the above variables were compared using repeated-measures analyses of variance (ANOVA) with Huynh Feldt degree of freedom correction factor to address heterogeneity of variance. Planned comparisons were conducted between each condition for every time bin for temperature and summary measures for sleep episode. Multiple comparisons were examined with Fisher least significant tests combined with a modified Bonferroni correction to reduce type I error. Data are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). A priori Pearson correlation coefficients were computed between DPG and SOL measures because findings from prior studies indicated relationships among these measures.18 In addition, post hoc Pearson correlation coefficients were computed for the change from baseline in CBT, Tsub, Tft or DPG, and sleep measures. Baseline temperature level was defined as the 40 minutes prior to pill administration and was compared to the average change in temperature for the 110 minutes following pill administration for the correlation analyses.

RESULTS

Body Temperature

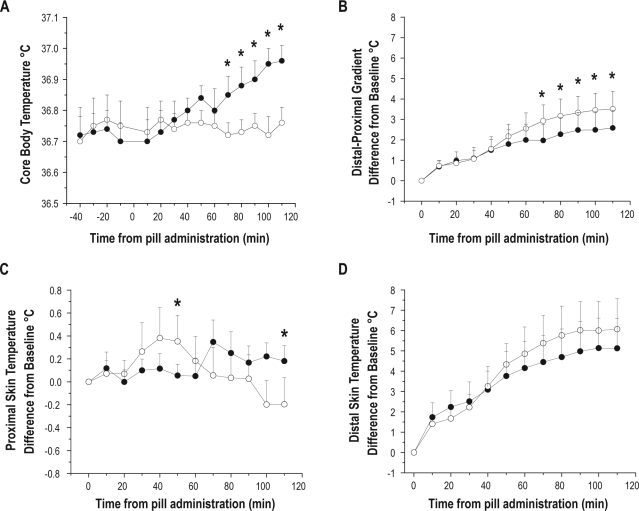

Ramelteon (8 mg) significantly attenuated the circadian rise in CBT (Figure 2A) and significantly increased the DPG (Figure 2B) compared with placebo. There was a significant main effect of time and interaction of drug by time for CBT (Table 1). Additionally, there was a significant main effect of time for the DPG. Planned comparisons revealed a significant difference in the ramelteon condition for the DPG beginning 50 min prior to the sleep opportunity. There was a significant interaction of condition by time (Table 1) for Tsub with significant differences between conditions at 50 min and 110 min after drug intake. There was a higher proximal temperature at 50 min and a lower proximal temperature at 110 min in the ramelteon condition (Figure 2C). We found a significant main effect of time for Tft (Figure 2D).

Figure 2.

Thermoregulatory effects of ramelteon on core body temperature, the DPG, and proximal and distal skin temperature sites. Values expressed as means ± SEM. The open circles represent the ramelteon condition and closed circles represent the placebo condition. The 0 point denotes time that ramelteon or placebo were administered. (A) The melatonin agonist, ramelteon significantly reduced core temperature by attenuating the normal daytime circadian rise as seen in placebo. (B) The DPG was increased after ramelteon ingestion relative to placebo. (C) Proximal skin temperature measured at the subclavian vein (Tsub) (D) Distal skin temperature measured at the dorsal foot (Tft).

Table 1.

ANOVA results for thermoregulatory variables

| Measure | Drug | Time | D × T |

|---|---|---|---|

| CBT | F1,11 = 4.12, P = 0.067 | F10,110 = 2.88, P = 0.003* | F10,110 = 3.94, P = 0.00013* |

| DPG | F1,9 = 0.89, P = 0.370 | F10,90 = 11.09, P = 0.00000* | F10,90 = 1.49, P = 0.154 |

| Tsub | F1,12 = 0.078 | F10,120 = 1.04 | F10,120 = 3.09 |

| P = 0.79 | P = 0.41 | P = 0.002* | |

| Tft | F1,9 = 0.28 | F10,90 = 10.84 | F10,90 = 0.89 |

| P = 0.61 | P = 0.00000* | P = 0.55 | |

denotes a significant value.

Sleep Physiology

Ramelteon significantly reduced % wakefulness and WASO and significantly increased subjective and objective (PSG) TST (Table 2). Increased sleep duration primarily reflected significant increases in the percentage of stages 1 and 2 sleep, with nonsignificant changes in slow wave sleep (SWS), REM sleep, and SOL (Table 2).

Table 2.

EEG and subjective sleep measures

| Parameter | Placebo | Ramelteon | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stage 1 (% RT) | 6.0 ± 0.9 | 8.5 ± 1.1 | 0.035* |

| Stage 2 (% RT) | 34.4 ± 4.0 | 50.4 ± 3.4 | 0.0004* |

| Stage 3/4 (% RT) | 12.9 ± 2.3 | 11.5 ± 1.8 | 0.57 |

| REM (% RT) | 9.6 ± 1.7 | 8.5 ± 1.4 | 0.45 |

| Wakefulness (% RT) | 37.2 ± 6.8 | 21.0 ± 4.3 | 0.02* |

| SOL (min) | 8.1 ± 1.2 | 6.5 ± 1.0 | 0.33 |

| WASO (min) | 82.2 ± 15.7 | 45.7 ± 9.6 | 0.01* |

| TST (min) | 150.7 ± 16.2 | 193.9 ± 10.8 | 0.02* |

| Subjective TST (min) | 101.5 ± 15.4 | 177.5 ± 20.5 | 0.002* |

Sleep stages and % wakefulness are expressed relative to the 240-minute sleep opportunity recording time (RT).

denotes a significant value using the modified Bonferroni correction (P < 0.047).

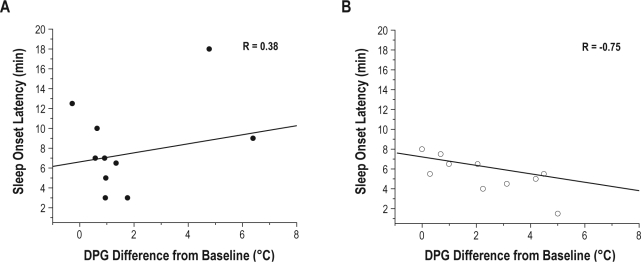

Correlations between Temperature and Sleep Physiology

In the placebo condition, there were no significant correlations for the DPG (Figure 3A, P = 0.28), CBT, Tsub, or Tft temperatures with any sleep measure. In the ramelteon condition, however, there were significant negative correlations for the DPG with SOL (Figure 3B, P = 0.013) and with percent of stage 1 sleep (r = −0.73, P = 0.02). Similarly, Tft was negatively correlated with SOL (r = −0.68, P = 0.03) and with percent of stage 1 sleep (r = −0.71, P = 0.02). Additionally, Tft was positively correlated with percent of stage 3-4 sleep (r = 0.69, P = 0.03). There were no significant correlations with CBT or Tsub and any sleep measure in the ramelteon condition. As shown in Figure 3A, two participants were outliers for the change in DPG during the placebo condition. Calculating the interquartile range (IQR) identified one subject as an extreme (IQR*3) and the other subject as a mild outlier (IQR*1.5). When these 2 individuals were removed from the placebo analysis, a significant negative correlation of −0.83 (P = 0.01) was observed between SOL and DPG, but not between DPG and any other sleep measure.

Figure 3.

Correlation between SOL and DPG. SOL (3 continuous epochs to sleep) and DPG were correlated such that a greater change in DPG was associated with a shorter SOL in the ramelteon condition (B) compared to placebo condition (A). The lines represent the best linear fit through the data.

DISCUSSION

Administration of the melatonin MT-1/MT-2 agonist ramelteon (8 mg) 2 h prior to a daytime sleep opportunity reduced CBT, increased the DPG, initially increased and then decreased proximal skin temperature, and improved daytime sleep relative to placebo. Ramelteon improved daytime sleep as measured by increases in TST, stages 1 and 2 sleep, and a decrease in WASO. Ramelteon has been reported to significantly reduce SOL at night.32 We did not find a significant reduction in SOL in the ramelteon condition, perhaps due to a floor effect as we tested healthy young individuals without sleep problems during an afternoon sleep opportunity. The attenuation of the circadian rise in CBT following ramelteon administration was accompanied by changes in skin temperature as determined by proximal skin temperature and DPG. Finally, the magnitude of the increase in DPG and distal skin temperature were correlated with a faster latency to sleep in the ramelteon condition.

Together with findings from previous studies that have demonstrated a hypothermic effect of melatonin,8–11 the current findings suggest that the sleep promoting effect of ramelteon may be mediated in part through its ability to lower CBT. The magnitude of change in CBT observed with ramelteon administration was similar to that reported with exogenous melatonin.9 Perhaps more important to the initiation of sleep is the finding that ramelteon caused an increase in distal skin temperature and DPG, as the latter has been shown to predict SOL.18 We also found a greater change in DPG and distal skin temperature to be associated with less stage 1 sleep and a greater change in distal skin temperature to be associated with more stage 3-4 sleep. Previous research findings have demonstrated an increase in slow wave sleep in young and older individuals following skin warming.37 The present study provides further evidence that changes in skin temperature are associated with changes in sleep staging.

Melatonin and melatonin analogues appear to primarily influence skin blood flow as compared to other circulatory beds such as cerebral blood flow.23 Heat loss after the administration of exogenous melatonin has been reported to occur through vasodilation of peripheral skin blood vessels, presumably arterial-venous anastomoses in the hands and feet.12,13 The opening of these important thermoregulatory sites facilitates a high level of blood flow to the skin, thus creating a positive thermal gradient with the environment and allowing for the convective exchange of heat to occur.38 It is unclear mechanistically how ramelteon and melatonin are able to modulate skin temperature. It is possible that both the sympathetic noradrenergic vasoconstrictor and non-adrenergic active vasodilator systems that are involved in temperature regulation during cold and heat stress, respectively, contribute to the thermoregulatory changes observed.38 For example, it has been reported that daytime exogenous melatonin administration reduces the thermoregulatory set-point for vasoconstriction during whole body cooling.13 Additionally, whole body warming has been reported to result in a lower internal threshold for activation of the active cutaneous vasodilator system following melatonin administration.12 Further, in the rat caudal artery (an important site for thermoregulation), melatonin potentiated the vasoconstrictor response to an α-adrenergic agonist through MT-1 receptor activation, while causing vasodilation through MT-2 receptor activation.39 Taken together, these data suggest melatonin and/or melatonergic analogues may modulate temperature through central mediated changes in sympathetic outflow as well as peripheral activation of the membrane bound MT-1 and MT-2 receptors located on the smooth muscle cells of the vasculature.

The time course of the effects of ramelteon on CBT and proximal skin temperature suggests that thermoregulatory effects are first observed near the reported time of peak ramelteon concentration, approximately 45 minutes following administration.40 It is unknown specifically how changes in skin and core temperature are mechanistically involved with initiating and/or maintaining sleep. An increase in skin temperature may stimulate thermosensitive nerve endings located in the skin,41,42 the preoptic anterior hypothalamus (POAH),42 interfascicular part of the dorsal raphe nucleus,41,43,44 or other thermosensitive brain centers. Stimulation of these temperature sensitive neural circuits may affect sleep promoting brain areas and/or inhibit wakefulness-promoting brain areas. It has been demonstrated that cutaneous warming of proximal skin via a liquid filled, temperature-controlled whole-body thermosuit resulted in a decrease in SOL by 27%.45 Additionally, an effect of temperature manipulation on the neural activity of brain centers thought to be involved in sleep and wakefulness has been reported. Specifically, a subpopulation of warm-sensitive POAH neurons spontaneously increases its firing rate at sleep onset and experimental warming of the POAH induces a similar increase in this firing rate.46–48 Further, POAH thermosensitive neurons have been shown to affect the discharge rate of neurons located in areas known to regulate sleep and wakefulness.46 It has been proposed that a positive feedback loop exists where changes in CBT and heat loss both trigger and reinforce sleep onset.42,49 In this model, a reduction in the thermoregulatory set point that occurs during the transition from wakefulness to sleep results in further heat loss and a sustained reduction in CBT. Our findings are in agreement with previous research showing that changes in CBT may be less associated with decreases in SOL as compared to changes in skin temperature in younger and older adults.45,50

Ramelteon may also influence sleep physiology by binding to melatonin receptors in the central nervous system. As noted, the actions of melatonin are mediated by two G-protein coupled receptor subtypes, termed the MT-1 and MT-2 receptors.51 It has been hypothesized that the sleep promoting response is mediated by the MT-1 receptor subtype.51 Binding of melatonin to MT-1 receptors on the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) is reported to inhibit SCN electrical activity.52,53 The SCN projects to wakefulness and sleep promoting brain regions, and thus ramelteon may promote sleep during the biological daytime by inhibiting the circadian arousal signal.3,9 In contrast, when endogenous melatonin levels are high, ramelteon has less influence on sleep physiology, except for reductions in sleep latency.54 It is also possible that ramelteon promotes sleep during the biological day via binding to MT-2 receptors. The selective MT-2 analogue IIK7 is reported to promote NREM sleep in rats,55 thus challenging the previously held assumption of discrete MT-1 and MT-2 receptor mediated effects.

To our knowledge, there have been no published studies in which ramelteon has been compared to melatonin on any outcome measure. Such a comparison between melatonin and its analogues could be useful. We believe that the future development of selective melatonin receptor agonists may provide more precise determination of the influence of melatonin receptor subtypes on human physiology. This may ultimately lead to more targeted therapies.

It is unclear why two of the participants when receiving placebo had a large DPG. Removing these individuals resulted in a significant correlation between DPG and SOL for the placebo condition. It is worth noting that in the placebo condition, only two participants had a DPG greater than 2°C, whereas more than half of participants had a DPG greater than 2°C in the ramelteon condition. Thus, ramelteon appears to have increased the magnitude and variance in the change of the DPG, increasing the likelihood of observing a significant relationship between the DPG and SOL.32

In conclusion, ramelteon improved objective and subjective markers of sleep during a daytime sleep episode. These effects were associated with thermoregulatory adjustments observed in response to ramelteon administration. The findings that ramelteon improves sleep during the biological day suggests that ramelteon may have potential as a therapeutic target for the treatment of insomnia associated with circadian rhythm sleep disorders in which sleep occurs at inappropriate biological times.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

This was an investigator initiated study supported by Takeda Pharmaceuticals, the makers of Ramelteon. Dr. Wright has consulted for Cephalon, Takeda, and Axon Labs and has financial interests in Zeo Inc. The other authors have indicated no additional financial conflicts of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by an investigator initiated grant from Takeda Pharmaceuticals North America, Inc., and by grants from The Howard Hughes Medical Institute Bioscience Grant in collaboration with the Biological Sciences Initiative at University of Colorado – Boulder and NIH MO1 - RR00051.

ABBREVIATIONS

- ANOVA

Analyses of variance

- CBT

Core body temperature

- CTRC

Clinical and Translational Research Center

- DPG

Distal proximal gradient

- ECG

Electrocardiogram

- EEG

Electroencephalography

- EMG

Electromyogram

- EOG

Electrooculogram

- IQR

Interquartile range

- PAOH

Preoptic anterior hypothalamus

- PSG

Polysomnography

- REM

Rapid eye movement sleep

- RT

Recording time

- SCN

Suprachiasmatic nucleus

- SEM

Standard error of the mean

- SOL

Sleep onset latency

- TST

Total sleep time

- SWS

Slow wave sleep

- Tft

Temperature site on dorsal left foot

- Tsub

Temperature site inferior to the left clavicle

- WASO

Wake after sleep onset

REFERENCES

- 1.Sack RL, Auckley D, Auger RR, et al. Circadian rhythm sleep disorders: part I, basic principles, shift work and jet lag disorders. Sleep. 2007;30:1460–83. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.11.1460. An American Academy of Sleep Medicine review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sack RL, Auckley D, Auger RR, et al. Circadian rhythm sleep disorders: part II, advanced sleep phase disorder, delayed sleep phase disorder, free-running disorder, and irregular sleep-wake rhythm. Sleep. 2007;30:1484–501. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.11.1484. An American Academy of Sleep Medicine review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sack RL, Hughes RJ, Edgar DM, Lewy AJ. Sleep-promoting effects of melatonin: at what dose, in whom, under what conditions, and by what mechanisms? Sleep. 1997;20:908–15. doi: 10.1093/sleep/20.10.908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Czeisler CA, Weitzman E, Moore-Ede MC, Zimmerman JC, Knauer RS. Human sleep: its duration and organization depend on its circadian phase. Science. 1980;210:1264–7. doi: 10.1126/science.7434029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Campbell SS, Broughton RJ. Rapid decline in body temperature before sleep: fluffing the physiological pillow? Chronobiol Int. 1994;11:126–31. doi: 10.3109/07420529409055899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zulley J, Wever R, Aschoff J. The dependence of onset and duration of sleep on the circadian rhythm of rectal temperature. Pflugers Arch. 1981;391:314–8. doi: 10.1007/BF00581514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dijk DJ, von Schantz M. Timing and consolidation of human sleep, wakefulness, and performance by a symphony of oscillators. J Biol Rhythms. 2005;20:279–90. doi: 10.1177/0748730405278292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dawson D, Gibbon S, Singh P. The hypothermic effect of melatonin on core body temperature: is more better? J Pineal Res. 1996;20:192–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079x.1996.tb00258.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hughes RJ, Badia P. Sleep-promoting and hypothermic effects of daytime melatonin administration in humans. Sleep. 1997;20:124–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reid K, Van den Heuvel C, Dawson D. Day-time melatonin administration: effects on core temperature and sleep onset latency. J Sleep Res. 1996;5:150–4. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2869.1996.t01-1-00006.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Satoh K, Mishima K. Hypothermic action of exogenously administered melatonin is dose-dependent in humans. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2001;24:334–40. doi: 10.1097/00002826-200111000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aoki K, Stephens DP, Zhao K, Kosiba WA, Johnson JM. Modification of cutaneous vasodilator response to heat stress by daytime exogenous melatonin administration. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2006;291:R619–24. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00117.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aoki K, Zhao K, Yamazaki F, et al. Exogenous melatonin administration modifies cutaneous vasoconstrictor response to whole body skin cooling in humans. J Pineal Res. 2008;44:141–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2007.00501.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krauchi K, Cajochen C, Wirz-Justice A. A relationship between heat loss and sleepiness: effects of postural change and melatonin administration. J Appl Physiol. 1997;83:134–9. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1997.83.1.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krauchi K, Pache M, von Arb M, Wirz-Justice A, Flammer J. Increased sleepiness and finger skin temperature after melatonin administration: A topographical infrared thermometry analysis. Sleep. 2002;25:A175–A. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wright KP, Jr, RN . Melatonin: from Molecules to Therapy. Hauppauge: Nova Science Publishers, Inc; 2007. Endogenous Versus Exogenous Effects of Melaton; pp. 547–69. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krauchi K, Cajochen C, Werth E, Wirz-Justice A. Warm feet promote the rapid onset of sleep. Nature. 1999;401:36–7. doi: 10.1038/43366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krauchi K, Cajochen C, Werth E, Wirz-Justice A. Functional link between distal vasodilation and sleep-onset latency? Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2000;278:R741–8. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2000.278.3.R741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lack L, Gradisar M. Acute finger temperature changes preceding sleep onsets over a 45-h period. J Sleep Res. 2002;11:275–82. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2869.2002.00312.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aoki K, Yokoi M, Masago R, Iwanaga K, Kondo N, Katsuura T. Modification of internal temperature regulation for cutaneous vasodilation and sweating by bright light exposure at night. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2005;95:57–64. doi: 10.1007/s00421-005-1392-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krauchi K, Cajochen C, Pache M, Flammer J, Wirz-Justice A. Thermoregulatory effects of melatonin in relation to sleepiness. Chronobiol Int. 2006;23:475–84. doi: 10.1080/07420520500545854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rubinstein EH, Sessler DI. Skin-surface temperature gradients correlate with fingertip blood flow in humans. Anesthesiology. 1990;73:541–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van der Helm-van Mil AH, van Someren EJ, van den Boom R, van Buchem MA, de Craen AJ, Blauw GJ. No influence of melatonin on cerebral blood flow in humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:5989–94. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-031107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Frank SM, Higgins MS, Fleisher LA, Sitzmann JV, Raff H, Breslow MJ. Adrenergic, respiratory, and cardiovascular effects of core cooling in humans. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:R557–62. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1997.272.2.R557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aoki K, Stephens DP, Saad AR, Johnson JM. Cutaneous vasoconstrictor response to whole body skin cooling is altered by time of day. J Appl Physiol. 2003;94:930–4. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00792.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhdanova IV, Wurtman RJ, Morabito C, Piotrovska VR, Lynch HJ. Effects of low oral doses of melatonin, given 2-4 hours before habitual bedtime, on sleep in normal young humans. Sleep. 1996;19:423–31. doi: 10.1093/sleep/19.5.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dollins AB, Zhdanova IV, Wurtman RJ, Lynch HJ, Deng MH. Effect of inducing nocturnal serum melatonin concentrations in daytime on sleep, mood, body temperature, and performance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:1824–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.5.1824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gilbert SS, van den Heuvel CJ, Dawson D. Daytime melatonin and temazepam in young adult humans: equivalent effects on sleep latency and body temperatures. J Physiol. 1999;514:905–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.905ad.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Holmes AL, Gilbert SS, Dawson D. Melatonin and zopiclone: the relationship between sleep propensity and body temperature. Sleep. 2002;25:301–6. doi: 10.1093/sleep/25.3.301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wyatt JK, Dijk DJ, Ritz-de Cecco A, Ronda JM, Czeisler CA. Sleep-facilitating effect of exogenous melatonin in healthy young men and women is circadian-phase dependent. Sleep. 2006;29:609–18. doi: 10.1093/sleep/29.5.609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pandi-Perumal SR, Srinivasan V, Poeggeler B, Hardeland R, Cardinali DP. Drug insight: the use of melatonergic agonists for the treatment of insomnia-focus on ramelteon. Nat Clin Pract Neurol. 2007;3:221–8. doi: 10.1038/ncpneuro0467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zammit G, Schwartz H, Roth T, Wang-Weigand S, Sainati S, Zhang J. The effects of ramelteon in a first-night model of transient insomnia. Sleep Med. 2009;10:55–9. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2008.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Roth T, Seiden D, Sainati S, Wang-Weigand S, Zhang J, Zee P. Effects of ramelteon on patient-reported sleep latency in older adults with chronic insomnia. Sleep Med. 2006;7:312–8. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2006.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mayer G, Wang-Weigand S, Roth-Schechter B, Lehmann R, Staner C, Partinen M. Efficacy and safety of 6-month nightly ramelteon administration in adults with chronic primary insomnia. Sleep. 2009;32:351–60. doi: 10.1093/sleep/32.3.351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cagnacci A, Soldani R, Laughlin GA, Yen SS. Modification of circadian body temperature rhythm during the luteal menstrual phase: role of melatonin. J Appl Physiol. 1996;80:25–9. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1996.80.1.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rechtschaffen A, Kales A. A manual of standardized terminology, techniques and scoring system for sleep stages of human subjects. Los Angeles: UCLA Brain Information Service/Brain Research Institute; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Raymann RJ, Swaab DF, Van Someren EJ. Skin deep: enhanced sleep depth by cutaneous temperature manipulation. Brain. 2008;131:500–13. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Charkoudian N. Skin blood flow in adult human thermoregulation: how it works, when it does not, and why. Mayo Clin Proc. 2003;78:603–12. doi: 10.4065/78.5.603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Masana MI, Doolen S, Ersahin C, et al. MT(2) melatonin receptors are present and functional in rat caudal artery. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2002;302:1295–302. doi: 10.1124/jpet.302.3.1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kato K, Hirai K, Nishiyama K, et al. Neurochemical properties of ramelteon (TAK-375), a selective MT1/MT2 receptor agonist. Neuropharmacology. 2005;48:301–10. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2004.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lowry C, Lightman S, Nutt D. That warm fuzzy feeling: brain serotonergic neurons and the regulation of emotion. J Psychopharmacol. 2009;23:392–400. doi: 10.1177/0269881108099956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Van Someren EJ. More than a marker: interaction between the circadian regulation of temperature and sleep, age-related changes, and treatment possibilities. Chronobiol Int. 2000;17:313–54. doi: 10.1081/cbi-100101050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cronin MJ, Baker MA. Physiological responses to midbrain thermal stimulation in the cat. Brain Res. 1977;128:542–6. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(77)90180-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Werner J, Bienek A. The significance of nucleus raphe dorsalis and centralis for thermoafferent signal transmission to the preoptic area of the rat. Exp Brain Res. 1985;59:543–7. doi: 10.1007/BF00261345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Raymann RJ, Swaab DF, Van Someren EJ. Cutaneous warming promotes sleep onset. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2005;288:R1589–97. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00492.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Alam N, Szymusiak R, McGinty D. Local preoptic/anterior hypothalamic warming alters spontaneous and evoked neuronal activity in the magno-cellular basal forebrain. Brain Res. 1995;696:221–30. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)00884-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McGinty D, Alam MN, Szymusiak R, Nakao M, Yamamoto M. Hypothalamic sleep-promoting mechanisms: coupling to thermoregulation. Arch Ital Biol. 2001;139:63–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.McGinty D, Szymusiak R. Keeping cool: a hypothesis about the mechanisms and functions of slow-wave sleep. Trends Neurosci. 1990;13:480–7. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(90)90081-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gilbert SS, van den Heuvel CJ, Ferguson SA, Dawson D. Thermoregulation as a sleep signalling system. Sleep Med Rev. 2004;8:81–93. doi: 10.1016/S1087-0792(03)00023-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Raymann RJ, Van Someren EJ. Diminished capability to recognize the optimal temperature for sleep initiation may contribute to poor sleep in elderly people. Sleep. 2008;31:1301–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dubocovich ML. Melatonin receptors: role on sleep and circadian rhythm regulation. Sleep Med. 2007;8(Suppl 3):34–42. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2007.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jin X, von Gall C, Pieschl RL, et al. Targeted disruption of the mouse Mel(1b) melatonin receptor. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:1054–60. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.3.1054-1060.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liu C, Weaver DR, Jin X, et al. Molecular dissection of two distinct actions of melatonin on the suprachiasmatic circadian clock. Neuron. 1997;19:91–102. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80350-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Roth T, Stubbs C, Walsh JK. Ramelteon (TAK-375), a selective MT1/MT2-receptor agonist, reduces latency to persistent sleep in a model of transient insomnia related to a novel sleep environment. Sleep. 2005;28:303–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fisher SP, Sugden D. Sleep-promoting action of IIK7, a selective MT2 melatonin receptor agonist in the rat. Neurosci Lett. 2009;457:93–6. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2009.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]