Abstract

We have reported that epithelial adenosine 2B receptor (A2BAR) mRNA and protein are up-regulated in colitis, which we demonstrated to be regulated by tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α). Here, we examined the mechanism that governs A2BAR expression during colitis. A 1.4-kb sequence of the A2BAR promoter was cloned into the pFRL7 luciferase vector. Anti-microRNA (miRNA) was custom-synthesized based on specific miRNA binding sites. The binding of miRNA to the 3′-untranslated region (UTR) of A2BAR mRNA was examined by cloning this 3′-UTR downstream of the luciferase gene in pMIR-REPORT. In T84 cells, TNF-α induced a 35-fold increase in A2BAR mRNA but did not increase promoter activity in luciferase assays. By nuclear run-on assay, no increase in A2BAR mRNA following TNF-α treatment was observed. Four putative miRNA target sites (miR27a, miR27b, miR128a, miR128b) in the 3′-UTR of the A2BAR mRNA were identified in T84 cells and mouse colon. Pretreatment of cells with TNF-α reduced the levels of miR27b and miR128a by 60%. Over expression of pre-miR27b and pre-miR128a reduced A2BAR levels by >60%. Blockade of miR27b increased A2BAR mRNA levels by 6-fold in vitro. miR27b levels declined significantly in colitis-affected tissue in mice in the presence of increased A2BAR mRNA. Collectively, these data demonstrate that TNF-α-induced A2BAR expression in colonic epithelial cells is post-transcriptionally regulated by miR27b and miR128a and show that miR27b influences A2BAR expression in murine colitis.

Keywords: Diseases, G Proteins/Coupled Receptors (GPCR), Gene/Regulation, Methods/PCR, Protein, Receptors/Regulation, Adenosine 2B Receptor, Colitis, miR27b, miR128a, TNF-α

Introduction

There are 4 adenosine receptors: A1AR, A2AAR, A2BAR, and A3AR. A2BAR3 is the predominant adenosine receptor that is expressed in human colonic epithelial cells and colonic epithelial-derived cell lines, such as T84 (1). In intestinal epithelial cells, A2BAR couples with Gαs and activates adenylate cyclase. In the colonic epithelium, A2BAR regulates vectorial electrogenic ion secretion, a secretory pathway that results in movement of isotonic fluid into the lumen (2–4). Up-regulation of ion secretion during inflammation is believed to be an important process in inflammation-associated diarrhea (5, 6). In addition to its effect on ion transport, A2BAR mediates luminal secretion of interleukin-6 by polarized colonic epithelial cells, which results in neutrophil activation (7). Similarly, adenosine induces apical secretion of fibronectin, which potentiates the adhesion and invasion of Salmonella typhimurium through chemokine secretion (8).

We have observed that A2BAR mRNA and protein expression are up-regulated in human and animal models of inflammatory bowel disease (9). We have demonstrated that deletion of the A2BAR gene protects against murine colitis (10). In addition, A2BAR antagonists mitigate colonic inflammation in murine models of colitis (11), suggesting that A2BAR is a therapeutic target in inflammatory bowel disease and other intestinal inflammatory diseases. In this study, we examined the regulation of A2BAR expression in the colon by TNF-α, a critical proinflammatory cytokine that plays an important role in the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease and whose antagonism constitutes an effective therapeutic strategy for inflammatory bowel disease (12).

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

pFRL7 luciferase vector was a gift from Richard A. Hodin (13). TNF-α was from R&D Systems. The First-strand cDNA Synthesis kit was from Fermentas (catalogue no. K1612; Hanover, MD). Invitrogen Ncode microRNA (miRNA) First-strand cDNA Module kit was catalogue no. 45-6612. iQ SYBR Green Supermix was from Bio-Rad.

Pre-miRNAs and anti-miRNAs for 27b, 128a, and let 7c, and the lipid-based SiPort NeoFX transfection reagent for tranfection of pre-miRNAs were purchased from Ambion (Austin, TX). The cAMP immunoassay kit was from Applied Biosystems (Bedford, MA), isobutyl-1-methylxanthine was from Biomol Research Laboratories, Inc. (Plymouth Meeting, PA), adenosine was from Research Biochemicals International (Natick, MA), and dextran sodium sulfate (DSS, molecular weight 50,000) was from ICN Biomedicals (Aurora, OH).

Prediction of miRNA Targets for A2BAR Gene

To identify the targets of human miRNAs for the A2BAR receptor, we used PicTar software, an algorithm that identifies miRNA targets. The miRNA target database contains all animal miRNA sequences from miRBase. The sequence database was scanned against the 3′-untranslated regions (3′-UTRs) that have been predicted in all available species in Ensemble. The interface links each miRNA to a list of predicted gene targets. A2BAR has four putative miRNA target sites (miR27a, miR27b, miR128a, and miR128b) in the 3′-UTR of A2BAR mRNA. Fig. 3 shows the binding sites and target miRNA alignments for the A2BAR 3′-UTR.

FIGURE 3.

TNF-α pretreatment down-regulates miR27b and miR128a levels. A, T84 cells were pretreated with or without TNF-α. Cells were harvested after 2 h, and total RNA was extracted from the cells. A2BAR mRNA levels were determined by real-time PCR. Data represent the mean ± S.E. (error bars) of two independent experiments; n = 6. B, T84 cells were pretreated with or without TNF-α, and total RNA was extracted. miR27b and miR128a levels were measured using specific primers and normalized to 5.8S. Data represent mean ± S.E. of two independent experiments; n = 6.

Cloning of 3′-UTR of A2BAR with Predicted miRNA Target Sequences

The 402-bp 3′-UTR of A2BAR, encompassing the predicted miRNA sequences, was inserted into the multiple cloning site of the pMIR-REPORT luciferase miRNA expression reporter (Applied Biosystems catalogue no. AM5795) with HindIII and SpeI.

miRNA Reverse Transcription

Total RNA was extracted using TRI reagent (MRC, Inc.). Reverse transcription was performed per the Invitrogen Ncode miRNA first-strand cDNA module kit protocol.

Nuclear Run-on Assay

Nuclear run-on assay was performed according to the protocol of Dr. Yan (14). Briefly, nuclei were isolated from T84 cells that were untreated or treated with 10 ng/ml TNF-α for 2–4 h. Cells (5 × 107) were pelleted in a test tube and washed twice with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline. Cells were then lysed on ice for 10 min in lysis buffer, containing 0.3 m sucrose, 0.4% (v/v) Nonidet P-40, 10 mm Tris-HCl at pH 7.4, 10 mm NaCl, and 3 mm MgCl2.

After centrifugation (15 min at 500× g), the nuclear pellet was resuspended and subjected to an additional 5-min lysis to remove any remaining intact cells. Following centrifugation, the nuclei were purified by centrifugation through a 2.0 m sucrose cushion. The nuclei were resuspended in 300 μl of transcription buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 150 mm KCl, 5 mm MgCl2, 0.5 mm MnCl2, 1 mm dithiothreitol, 0.1 mm EDTA, 10% glycerol).

After sequential pretreatment with 1 μl of 50 μg/ml RNase A and 2.5 μl (100 units) of RNasin (Promega, Madison, WI), the in vitro elongation reaction was initiated with 0.25 mm each ATP, GTP, CTP, and UTP. The reaction proceeded for 25 min at 30 °C. After incubation with RNase-free DNase, RNA was extracted with phenol-chloroform, precipitated with ammonium acetate and isopropyl alcohol, washed with 70% ethanol, and dissolved in water. cDNA was synthesized with the Fermentas First-strand synthesis system and amplified by real-time PCR using A2BAR-specific primers and 18S as an internal control.

Cell Culture

T84 cells were grown and maintained in culture as described (15) in a 1:1 mixture of Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium and F-12 medium, supplemented with penicillin (40 mg/liter), streptomycin (90 mg/liter), and 5% fetal bovine serum. Confluent stock monolayers were subcultured by trypsinization.

Experiments were performed using cells plated for 7–8 days on permeable supports of 4.5-cm2 inserts. Inserts (0.4-μm pore size; Costar, Cambridge, MA) were rested in wells that contained medium until steady-state resistance was achieved, as described (16, 17). Caco2-BBe cells and HT29-Cl.19A cells were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium, supplemented with 14 mmol/liter NaHCO3, 10% fetal bovine serum, and penicillin/streptomycin (Invitrogen).

Real-time PCR

Real-time PCR was performed using the iCycler sequence detection system (Bio-Rad). Briefly, 50 ng of reverse-transcribed cDNA was amplified (40 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s and 55 °C for 1 min), using 10 μm gene-specific primers.

The primers were: mouse A2BAR forward, ATGCAGCTAGAGACGCAAGA and reverse, GTTGGTGGGGGTCTGTAATG; human A2BAR forward, TTCTGCACTGACTTCTACGG and reverse, TTTATACCTGAGCGGGACAC; mature miR27b forward, TTCACAGTGGCTAAGTTCTGC and reverse, universal qPCR primer provided in the kit (Invitrogen Ncode miRNA First-strand cDNA synthesis and reverse transcription qPCR kit); mature miR128a forward, TCACAGTGAACCGGTCTCTTTT and reverse, universal qPCR primer.

Internal controls were: human18S forward, CCCCTCGATGCTCTTAGCTGAGTGT and reverse, CGCCGGTCCAAGAATTTCACCTCT; mouse 36B4 forward, TCCAGGCTTTGGGCATCA and reverse, CTTTATCAGCTGGACATCACTCAG; human 5.8S forward, AGGACACATTGATCATCGACACTTCGA and reverse, universal qPCR primer; mouse SnoRNA55 forward, TGACGACTCCATGTGTCTGAGCAA and reverse, universal qPCR primer. Fold induction was calculated using the Ct method (ΔΔCT = (Ct target − Ct internal control) treatment − (Ct target − Ct internal control) nontreatment), and the final data were derived from 2−ΔΔCT.

Experimental Animals

The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Emory University approved all procedures that were performed on the animals. In addition, all experiments were conducted in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, published by the U.S. Public Health Service.

Six-week-old C57BL/6 mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME) and bred at our facility. They were maintained on a 12-hour light-dark cycle and allowed free access to pelleted diet and tap water at controlled temperatures (25 ± 2 °C).

Induction of DSS-Colitis

Colitis was induced in male C57BL/6 mice by ad libitum oral administration of 3% (w/v) DSS in tap water for 6 days. Age-matched male wild-type C57BL/6 mice that received tap water served as controls. Mice were observed daily and evaluated for changes in body weight and the development of clinical symptoms.

Transient Transfection of Pre-miR and Anti-miR

To study the regulation of A2BAR by miRNA, pre-miR27b and/or pre-miR128a (A2BAR target miRNAs) and a plasmid that contained the associated miR27b and miR128a binding sites in A2BAR (pMIR-3′-UTR) were co-transfected into subconfluent Caco2-BBe cells. The binding of miRNAs to A2BAR 3′-UTR mRNA was reflected by pMIR-REPORT luciferase activity. Anti-miR27b and/or anti-miR128a was introduced into HT29 cells to study the blockade of miR27b and miR128a. Endogenous A2BAR mRNA levels were measured by real-time PCR 48 h after transfection. The positive control for blocking efficiency was anti-miR let 7c, which regulates high mobility group A2 (HMGA-2) mRNA.

cAMP Measurement

HT29-Cl.19A cells were washed and equilibrated with Hanks' solution; then, the cells were untreated or treated with 100 μm adenosine (basolateral). cAMP measurements were made in whole cell lysates in the presence of 1 mm 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine using a competitive cAMP immunoassay kit according to the manufacturer's protocol. Luminescence was read on a Luminoscan Ascent (Thermo Labsystems, Needham Heights, MA).

To study the suppression of endogenous miRNA function, anti-miR27b and anti-miR128a (Ambion AM17000, 17100) were introduced into HT29 cells, and A2BAR signaling was measured by estimating the levels of adenosine-mediated cAMP production with and without transfection of the blockers.

Statistical Analysis

All data are expressed as means ± S.E. Statistical analysis was performed by Student's t test or analysis of variance (Prism 4.0; GraphPad, San Diego, CA). A p value < 0.05 was regarded as significant.

RESULTS

TNF-α Does Not Affect A2BAR Promoter Activity

Our previous studies demonstrated that A2BAR mRNA and protein were up-regulated in cells that were pretreated with TNF-α. To understand better the regulation of A2BAR, we performed experiments using a luciferase reporter construct that contained the A2BAR promoter (pFRL7 1.4A2BAR). The 5′-flanking region of A2BAR was obtained from Homo sapiens chromosome 17S from the PAC (P1-derived artificial chromosome) RPCI-1 121M24 map 17p11 (a gift from Dr. R. Reinhardt, Max Planck Institute for Molecular Genetics, Berlin, Germany) by PCR, yielding a 1.4-kb fragment of the region. The human A2BAR promoter sequence was submitted to NCBI GenBank under accession number DQ 351340. The isolated 1.4-kb and 2.5-kb fragments were subsequently cloned into the pFRL7 luciferase vector (13) at the KpnI and NcoI restriction sites to yield the pFRL7 1.4 A2BAR plasmid. The transcriptional start site, as determined by rapid amplification of cDNA ends using the Gene Racer kit (Invitrogen), was 119 bp upstream of the translational start site.

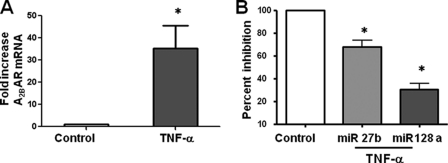

COS-7 or Caco2-BBe cells were transfected with pFRL7 1.4A2BAR and treated 72 h later with TNF-α for 6 h. As shown in Fig. 1, the relative luciferase activity in pFRL7 1.4 A2BAR total lysates (11.6 ± 1.3) was ∼10 times greater than that in empty vector transfectants (1.9 ± 0.13). TNF-α, however, did not increase A2BAR promoter activity (11.01 ± 0.3), despite the increase in A2BAR mRNA levels (9). Also, TNF-α had no effect on luciferase activity from a longer 2.5-kb fragment of the A2BAR promoter.

FIGURE 1.

TNF-α does not affect A2bAR promoter activity. The 1.4-kb fragment upstream of the A2BAR coding region was cloned into the pFRL7 luciferase vector. Cells were transfected with pFRL7 1.4 A2BAR or empty vector and untreated or treated with 20 ng/ml TNF-α for 6 h. Cells were lysed, and luciferase activity was measured. Data represent mean ± S.E. (error bars) of four independent experiments; n = 6. Open bars represent no treatment, and gray bars represent TNF-α treatment.

TNF-α Does Not Increase mRNA Transcription

To clarify the effect of TNF-α on A2BAR transcription, we performed nuclear run-on assays using nuclei from vehicle- or TNF-α-treated T84 cells. After in vitro elongation with dNTPs, the RNA was extracted, and novel A2BAR mRNA synthesis was quantified by real-time PCR using A2BAR-specific primers. There was no significant difference in A2BAR mRNA levels between vehicle- and TNF-α treated nuclei. These data indicate that TNF-α does not affect A2BAR transcription and suggest that TNF-α regulates A2BAR by a post-transcriptional mechanism. This experiment was repeated three times, each yielding similar results.

TNF-α Down-regulates miR27b and miR128a

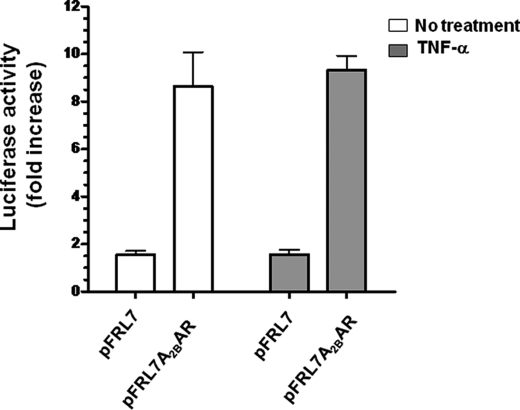

One of the primary mechanisms by which gene expression is post-transcriptionally regulated is miRNA. We determined whether A2BAR was regulated by miRNA. First, we performed an on-line search of miRNAs using the pictar and targetscan databases and identified four putative miRNA target sites (miR27a, miR27b, miR128a, and miR128b) in the 3′-UTR of A2BAR mRNA (Fig. 2). All four miRNAs were expressed in T84 cells.

FIGURE 2.

Schematic of miR27b and miR128a target sites in the 3′-UTR of A2BAR. We performed an on-line search of the miRNA using the pictar and targetscan databases and identified four putative miRNA target sites (miR27a, miR27b, miR128a, and miR128b) in the 3′-UTR of A2BAR mRNA. The binding sites and target miRNA alignment for the A2BAR 3′-UTR are shown.

To determine the effect of TNF-α on miRNA and A2BAR mRNA levels, we pretreated T84 cells for various times with TNF-α (10 ng/ml). Pretreatment of T84 cells with TNF-α increased A2BAR mRNA levels by ∼35-fold, (*p < 0.03, n = 6) (Fig. 3A) compared with untreated cells.

Pretreatment with TNF-α reduced the levels of miR27b and miR128a by 60% (*p < 0.001, n = 6) (Fig. 3B), whereas miR27a and miR128b levels were unaffected (data not shown). These data establish a direct correlation between A2BAR mRNA and the miR27b and miR128a miRNAs.

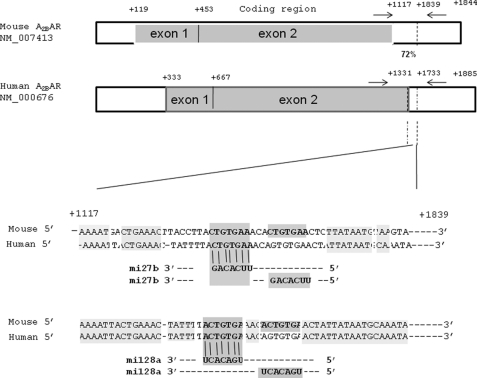

Pre-miR27b and -miR128a and Anti-miR27b and -miR128a Regulate A2BAR mRNA Levels and Function

Pre-miRNA precursors are small, partially double-stranded RNAs that mimic endogenous precursor miRNAs. To examine the regulation of A2BAR by miR27b and miR128a, we transfected T84 cells with pre-miR27b or pre-miR128a. Forty-eight hours after transfection, the cells were harvested, and A2BAR mRNA levels were determined by real-time PCR. As shown in Fig. 4A, transfection of pre-miR27b or pre-miR128a decreased A2BAR mRNA levels by 50% compared with untransfected cells (pre-miR27b 43.4 ± 4.83, *p < 0.001; pre-miR128a 30.3 ± 6.1, *p < 0.003), whereas 18S mRNA (control) was unaffected by pre-miR27b or pre-miR128a transfection. A commercial negative control pre-miRNA, containing a nontargeting sequence that had no homology to A2BAR, had no effect on A2BAR mRNA levels. These results demonstrate that miR27b and miR128a influence A2BAR mRNA levels.

FIGURE 4.

Pre-miR27b and -miR128a and anti-miR27b and -miR128a regulate A2BAR mRNA levels and function. A, T84 cells were transfected with pre-miR27b and pre-miR128a. Total RNA was extracted 48 h after transfection. A2BAR mRNA levels were measured by real-time PCR. Data represent mean ± S.E. (error bars) of two independent experiments; n = 6. B, colonic epithelial cells were transfected with anti-miR27b and anti-miR128a. Cells were harvested after 48 h, and total RNA was extracted from the cells. A2BAR mRNA levels were determined by real-time PCR. Data represent mean ± S.E.; n = 6. C, colonic epithelial cells were transfected with anti-miR27b and -miR128a. Cells were stimulated with adenosine for 7 min 48 h after tranfection. Total cell lysates were collected, and cAMP levels were estimated. Data represent mean ± S.E.; n = 10.

Next, we sought to determine the effect of inhibition of miR27b or miR128a on A2BAR mRNA. Cells were transfected with custom-synthesized blockers of the miR27b or miR128a binding sites, and A2BAR mRNA levels were measured by real-time PCR.

As shown in Fig. 4B, anti-miR27b and anti-miR128a increased A2BAR mRNA levels by 5.3 ± 0.9-fold (*p < 0.01) and 2.2 ± 0.02-fold (*p < 0.005), respectively, compared with vector-transfected cells. 18S mRNA did not change, demonstrating the specificity of the miR blockers for A2BAR mRNA. These data support the results of the pre-miRNA experiments and further demonstrate that miR27b and miR128a regulate A2BAR mRNA levels.

To determine whether the effects of miR27b and miR128a on A2BAR mRNA levels were reflected in functional alterations in A2BAR, we measured adenylate cyclase activity in HT29-Cl.19A cells that were transfected with anti-miR27b or anti-miR128a. Forty-eight hours after transfection, cells were treated basolaterally with adenosine (100 μm), and cAMP levels were measured. As shown in Fig. 4C, cAMP levels were significantly higher in miR27b (0.07 ± 0.01, *p < 0.02) and miR128a transfectants (0.08 ± 0.01, *p < 0.016) compared with untransfected cells (0.04 ± 0.004), suggesting that the up-regulation of A2BAR mRNA in anti-miR27b- and anti-miR128a-transfected cells effects an increase in A2BAR levels.

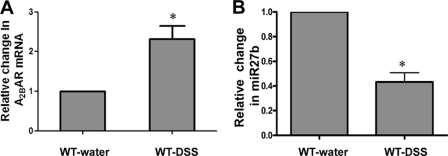

Elevations in A2BAR mRNA Levels during Colitis Correlate with Decreased miR27b Levels

We have shown that A2BAR mRNA and protein levels are increased during colitis. To determine whether miR27b or miR128a levels correlate inversely with A2BAR mRNA during colitis, we measured miR27b, miR128a, and A2BAR mRNA levels by real-time PCR in a DSS model of colitis. All mice that were fed 3% DSS for 7 days developed signs of severe colitis (clinical score: 9.4 ± 1.0; histological score: 9.1 ± 2.3), presented as bloody diarrhea and weight loss. Consistent with our previous observations (9), A2BAR mRNA levels increased 2.3 ± 0.3-fold (*p < 0.05), compared with control mice that received water (Fig. 5A). Notably, miR27b levels decreased 33.4 ± 6.6-fold (*p < 0.005) in colitic mice compared with control mice that received water (Fig. 5B). There was no change in miR128a levels (data not shown). These data demonstrate that there is an inverse correlation between miR27b and A2BAR mRNA, supporting evidence for a post-transcriptional mechanism of A2BAR regulation by miRNA.

FIGURE 5.

Increased levels of A2BAR mRNA during colitis correlate with decreased miR27b levels. Age- and gender-matched C57BL/6 mice were fed with 3% DSS for 7 days, after which mice were killed and examined for severity of colitis. Total RNA was extracted from the colons of these mice. A2BAR mRNA (A) and miR27b (B) levels were measured compared with control mice. Data are represented as A2BAR mRNA normalized to 18S, and miR27b is normalized to SnoRNA55. Data are represented as mean ± S.E. (error bars) of two independent experiments; n = 3. WT, wild type.

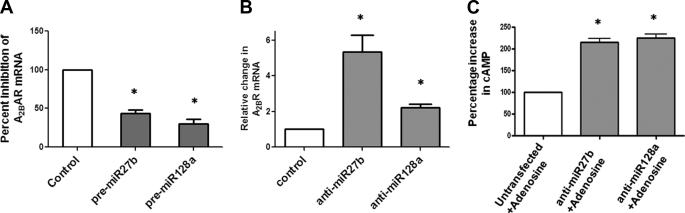

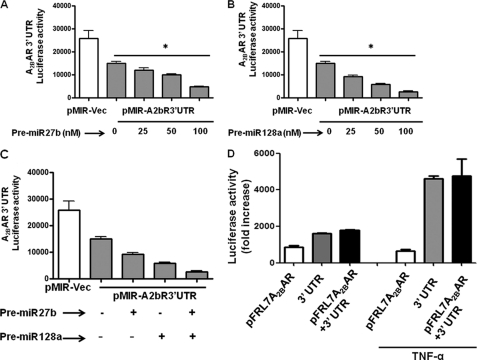

Pre-miR27b and Pre-miR128a Decrease A2BAR 3′-UTR Luciferase Activity

To confirm that miRNA functions through an interaction with the A2BAR 3′-UTR, we co-transfected pre-miR27b and/or pre-miR128a with the A2BAR 3′-UTR luciferase reporter construct pMIR-REPORT. As shown in Fig. 6, A and B, introduction of pre-miR27b or pre-miR128a significantly inhibited 3′-UTR-dependent A2BAR luciferase activity in a dose-dependent manner (25–100 nm, n = 8, *p < 0.0001). Further, co-transfection of pre-miR27b (50 nm) and pre-miR128a (50 nm) produced a robust additive inhibitory effect on luciferase activity (Fig. 6C). We performed the luciferase assay with an additional group, in which we co-transfected the A2BAR 3′-UTR and the A2BAR promoter. We observed no additional increase in luciferase activity beyond that induced by the 3′-UTR alone (Fig. 6D), suggesting that A2BAR expression is regulated by miRNA.

FIGURE 6.

Pre-miR27b and pre-miR128a decrease A2BAR 3′-UTR luciferase activity, and addition of A2BAR promoter to 3′-UTR does not influence luciferase activity. The 3′-UTR of the A2BAR-predicted miRNA binding target was inserted into the multiple cloning site of the pMIR-REPORT luciferase miRNA expression reporter vector. Pre-miR27b and pre-miR128a were co-transfected with A2BAR 3′-UTR pMIR-REPORT. Dose-dependent effect of pre-miR27b (A), dose-dependent effect of pre-miR128a (B), and additive effect of pre-miR27b and pre-miR128a (C) were demonstrated by luciferase assay. Data are represented as mean ± S.E. of two independent experiments; n = 12. D, transfection of 3′-UTR of A2BAR alone, pFRL7 1.4 A2BAR promoter alone, or 3′-UTR + pFRL7 1.4 A2BAR promoter together were transfected into Caco2-BBe cells with or without TNF-α treatment (20 ng/ml) for 6 h. Cells were lysed, and luciferase activity was measured. Data represent mean ± S.E. (error bars); n = 6.

DISCUSSION

miRNAs are short RNAs in introns and intergeneic regions that regulate gene expression. A large primary miRNA (pre-miRNA) is transcribed and processed to a pre-miRNA hairpin, which is converted in the cytoplasm into a mature miRNA that targets genes that harbor complementary sites in their 3′- or 5′-UTRs (18, 19). miRNAs are up- and down-regulated in several disease conditions. We have demonstrated that A2BAR protein levels increase after treatment with proinflammatory cytokines but that A2BAR promoter activity is unaltered. We also examined miRNAs in bioinformatics databases that were complementary to the A2BAR 3′-UTR to determine whether miR27b and miR128a regulated the levels of A2BAR mRNA and protein.

In our previous studies, we observed the up-regulation of A2BAR by TNF-α in colonic epithelial cells and in the DSS mouse model of colitis (9). Using a pFLR7 promoter-reporter construct that contained either the 1.4-kb and 2.5-kb fragments of the A2BAR promoter, we found that TNF-α did not increase A2BAR promoter activity (Fig. 1). A2BAR, however, has been shown to be transcriptionally regulated during hypoxia through hypoxia inducible factor (HIF)-binding elements (20) and by b-myb (21) in endothelial cells and vascular smooth muscle cells, respectively. Our luciferase assays were performed with whole cell lysates, which should have harbored all of the transcription factors that regulate the promoter. Studies by our laboratory and others have noted the transcriptional regulation of genes by TNF-α by 4–6 h, suggesting that the transcriptional mechanism is active in our luciferase assay (22–24). Similarly, by nuclear run-on assay, we observed no increase in A2BAR transcription in response to TNF-α. Although the involvement of other cis- or trans-elements and signaling pathways that regulate A2BAR transcription further upstream of the 2.5-kb element cannot be ruled out with these assays, these data strongly suggest that TNF-α up-regulates A2BAR through a post-transcriptional mechanism. Thus, we speculated that A2BAR regulation was mediated by A2BAR-specific miRNAs. A search of bioinformatics databases identified miR27b and miR128a as containing target sequences in the 3′-UTR of A2BAR. Treatment of colonic epithelial cells with TNF-α inhibited miR27b and miR128a by 60%, which was associated with a 5-fold increase in A2BAR mRNA levels (Fig. 4, A and B). Colonic tissue from mice with DSS-induced colitis experienced a 50% reduction in miR27b levels (Fig. 5B). These findings implicated miR27b and miR128a in the regulation of A2BAR mRNA. Our studies were unable to determine the relative contribution of miR27b and miR128a because the consensus binding sites for them in the A2BAR 3′-UTR overlap significantly (Fig. 2).

miRNAs constitute a prominent class of regulatory genes in animals, representing ∼1% of all predicted genes, suggesting that sequence-specific, post-transcriptional regulatory mechanisms that are mediated by these small RNAs are ubiquitous (25–27). We tested this hypothesis using synthetic pre-miRNAs (miRNA precursor molecules) and a reciprocal set of anti-miRNAs. Pre-miRNAs are small, chemically modified, double-stranded RNA molecules that mimic endogenous mature miRNA molecules. These molecules are incorporated into the RNA-induced silencing complex, which is also responsible for miRNA activity. In contrast to miRNA expression vectors, pre-miRNAs can be used in dose-response studies because they can be introduced directly into the cell by transfection. Inside cells, pre-miRNAs up-regulate miRNA activity (28), enabling one to analyze miRNA function. Transfection of pre-miRNA reduced A2BAR mRNA levels in T84 cells (Fig. 4A). In reciprocal experiments, blockade of miR27b and miR128a, as a result of the introduction of specific anti-miRNAs, increased A2BAR mRNA levels (Fig. 4B). Anti-miRNAs also enhanced adenosine-mediated cAMP production (Fig. 4C), indicating an increase in A2BAR function and directly linking miR27b and miR128a to the regulation of A2BAR expression (29). miRNAs have important functions in the regulation of genes. Several studies have demonstrated that miRNAs govern basic cellular functions. Studies by Care et al. (30, 31) noted that miR133 and miR1 regulate cardiomyocyte hypertrophy. In our experiments, co-transfection of pre-miR27b or pre-miR128a with an A2BAR 3′-UTR reporter construct increased luciferase activity in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 6, A and B). Co-transfection of pre-miR27b and pre-miR128a resulted in the additive inhibition of luciferase activity (Fig. 6C). By luciferase assay, co-tranfection of the 3′-UTR of A2BAR and the A2BAR promoter resulted in no additional increase in luciferase activity beyond that induced by 3′-UTR alone, suggesting that miRNA plays the significant role in the regulation of A2BAR expression (Fig. 6D).

Recent bioinformatic and experimental evidence suggests that a substantial proportion of genes (>30%) are subject to miRNA-mediated regulation (32). Our studies on the possible function of miRNAs in colonic inflammation demonstrate that miR27b and miR128a are critical regulators of A2BAR expression. Because A2BAR antagonism ameliorates colitis, our results suggest that the regulation of A2BAR expression by targeting miRNAs might be an effective therapeutic strategy for colitis.

The nucleotide sequence(s) reported in this paper has been submitted to the GenBankTM/EBI Data Bank with accession number(s) DQ 351340.

- A2BAR

- adenosine 2B receptor

- TNF-α

- tumor necrosis factor α

- miRNA

- microRNA

- DSS

- dextran sodium sulfate

- UTR

- untranslated region

- qPCR

- quantitative PCR.

REFERENCES

- 1.Strohmeier G. R., Reppert S. M., Lencer W. I., Madara J. L. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270, 2387–2394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barrett K. E., Huott P. A., Shah S. S., Dharmsathaphorn K., Wasserman S. I. (1989) Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 256, C197–C203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barrett K. E., Cohn J. A., Huott P. A., Wasserman S. I., Dharmsathaphorn K. (1990) Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 258, C902–C912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huang P., Lazarowski E. R., Tarran R., Milgram S. L., Boucher R. C., Stutts M. J. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 14120–14125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sugi K., Musch M. W., Field M., Chang E. B. (2001) Gastroenterology 120, 1393–1403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hecht G., Marrero J. A., Danilkovich A., Matkowskyj K. A., Savkovic S. D., Koutsouris A., Benya R. V. (1999) J. Clin. Invest. 104, 253–262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sitaraman S. V., Merlin D., Wang L., Wong M., Gewirtz A. T., Si-Tahar M., Madara J. L. (2001) J. Clin. Invest. 107, 861–869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Walia B., Castaneda F. E., Wang L., Kolachala V. L., Bajaj R., Roman J., Merlin D., Gewirtz A. T., Sitaraman S. V. (2004) Biochem. J. 382, 589–596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kolachala V., Asamoah V., Wang L., Obertone T. S., Ziegler T. R., Merlin D., Sitaraman S. V. (2005) Cell Mol. Life Sci. 62, 2647–2657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kolachala V. L., Vijay-Kumar M., Dalmasso G., Yang D., Linden J., Wang L., Gewirtz A., Ravid K., Merlin D., Sitaraman S. V. (2008) Gastroenterology 135, 861–870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kolachala V., Ruble B., Vijay-Kumar M., Wang L., Mwangi S., Figler H., Figler R., Srinivasan S., Gewirtz A., Linden J., Merlin D., Sitaraman S. (2008) Br. J. Pharmacol. 155, 127–137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.D'Haens G. (2003) Curr. Pharm. Des. 9, 289–294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Malo M. S., Mozumder M., Chen A., Mostafa G., Zhang X. B., Hodin R. A. (2006) Anal. Biochem. 350, 307–309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yan Y., Dalmasso G., Nguyen H. T., Obertone T. S., Sitaraman S. V., Merlin D. (2009) PLoS One 4, e5049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sitaraman S. V., Wang L., Wong M., Bruewer M., Hobert M., Yun C. H., Merlin D., Madara J. L. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 33188–33195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kolachala V., Asamoah V., Wang L., Srinivasan S., Merlin D., Sitaraman S. V. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 4048–4057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Merlin D., Jiang L., Strohmeier G. R., Nusrat A., Alper S. L., Lencer W. I., Madara J. L. (1998) Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 275, C484–C495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lytle J. R., Yario T. A., Steitz J. A. (2007) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 9667–9672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lai E. C. (2002) Nat. Genet. 30, 363–364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kong T., Westerman K. A., Faigle M., Eltzschig H. K., Colgan S. P. (2006) FASEB J. 20, 2242–2250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.St. Hilaire C., Yang D., Schreiber B. M., Ravid K. (2008) J. Cell. Biochem. 103, 1962–1974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Theiss A. L., Jenkins A. K., Okoro N. I., Klapproth J. M., Merlin D., Sitaraman S. V. (2009) Mol. Biol. Cell 20, 4412–4423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jobin C., Hellerbrand C., Licato L. L., Brenner D. A., Sartor R. B. (1998) Gut 42, 779–787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yu Y., Zeng H., Lyons S., Carlson A., Merlin D., Neish A. S., Gewirtz A. T. (2003) Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 285, G282–G290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lau N. C., Lim L. P., Weinstein E. G., Bartel D. P. (2001) Science 294, 858–862 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lai E. C. (2003) Curr. Biol. 13, R925–R936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lagos-Quintana M., Rauhut R., Lendeckel W., Tuschl T. (2001) Science 294, 853–858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lewis B. P., Shih I. H., Jones-Rhoades M. W., Bartel D. P., Burge C. B. (2003) Cell 115, 787–798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meister G., Landthaler M., Dorsett Y., Tuschl T. (2004) RNA 10, 544–550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carè A., Catalucci D., Felicetti F., Bonci D., Addario A., Gallo P., Bang M. L., Segnalini P., Gu Y., Dalton N. D., Elia L., Latronico M. V., Høydal M., Autore C., Russo M. A., Dorn G. W., 2nd, Ellingsen O., Ruiz-Lozano P., Peterson K. L., Croce C. M., Peschle C., Condorelli G. (2007) Nat. Med. 13, 613–618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen J. F., Mandel E. M., Thomson J. M., Wu Q., Callis T. E., Hammond S. M., Conlon F. L., Wang D. Z. (2006) Nat. Genet. 38, 228–233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nilsen T. W. (2007) Trends Genet. 23, 243–249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]