Abstract

Sanguinarine reductase is a plant enzyme that prevents the cytotoxic effects of benzophenanthridine alkaloids, which are the main phytoalexins of Papaveraceae. The enzyme catalyzes the reduction of sanguinarine, the most toxic benzophenanthridine, which re-enters the cytoplasm after its primary accumulation in the cell wall region has reached a threshold concentration. We present the sequence of the gene and protein of sanguinarine reductase isolated from cell cultures of Eschscholzia californica. High sequence similarities indicate that the enzyme evolved from a plant-specific branch of the ubiquitous Rossmann fold NAD(P)H/NAD(P)+ binding reductases, with NADP-dependent epimerases or hydroxysteroid reductases as the most likely ancestors. Based on the x-ray structure of a close homolog, a three-dimensional model of the spatial conformation and catalytic site of sanguinarine reductase was established and used for in silico screening of known three-dimensional structures. Surprisingly, the enzyme shares high structural similarity with enzymes of human and bacterial origin, which have similar functions as the plant homologs but bear little amino acid sequence similarity. Using site-directed mutagenesis, a series of recombinant enzymes was generated and assayed to reveal the impact of individual amino acids and peptides in the catalytic process. It appears that relatively few innovations were required to generate this selective catalyst for alkaloid detoxication, notably an insertion of 13 amino acids and the generation of a novel catalytic triad of Cys-Asp-His were sufficient.

Keywords: Evolution, Medicinal Chemistry, Mutant, Plant, Reductase, Eschscholzia Californica, Plant Secondary Metabolism, Alkaloid Biosynthesis, Homology Modeling of Enzymes, Plant Toxins

Introduction

The almost unlimited diversity of secondary metabolites in recent plant species reflects not only the evolution of specialized biosynthetic enzymes but also of several protective measures that make the production of these compounds compatible with the essential metabolism of the plants. Irrespective of whether the molecules provided by secondary biosynthesis are advantageous to the producing plant (e.g. in defense or communication), they threaten the fitness of the organism by draining building blocks and energy sources and bear the risk of intoxicating the producing organism. It is well established that plants rise to these challenges by separating secondary biosynthesis from the living cytoplasm, i.e. via compartmentalization and channeling of enzymes and metabolites. A less known but equally important mechanism of protection against self-intoxication is the coordinated expression of stress-protective and detoxifying enzymes. The value of protective and detoxifying enzymes is exemplified well by the management of the cytotoxic benzophenanthridine alkaloids, which are produced mainly in Papaverceae and some Ranunculaceae (1–3). The induction of biosynthesis of this alkaloid by pathogens and endogenous signals has been best investigated in cultured cells (4–6). The function of benzophenanthridine as highly effective antimicrobials through intercalation into double-stranded DNA and through interaction with various SH-dependent enzymes and transporters (7, 8), the strongest effects being exerted by sanguinarine (9, 10). Besides microbes, they are also toxic to plant cells not known to produce these alkaloids; low micromolar concentrations strongly inhibit the growth of cultured cells of Arabidopsis, Lycopersicum, and Nicotiana. In contrast, cells of Eschscholzia californica, which produce and excrete these alkaloids after elicitor contact, tolerate relatively high external concentrations (11). Most importantly, the benzophenanthridine-producing cells are not resistant per se to their own alkaloids but rather cope with them by a mechanism of metabolic detoxication; after the excreted benzophenanthridines reach a threshold content in the cell wall, they are reimported and immediately reduced to less toxic dihydro-benzophenanthridines by the cytoplasmic enzyme sanguinarine reductase. The fastest conversion is shown with sanguinarine, which is the most toxic among the benzophenanthridines. The resulting dihydrosanguinarine is further derivatized by late enzymes of alkaloid biosynthesis and thus yields less toxic products (11). In this way, sanguinarine reductase initiates a recycling process that allows the presentation of the cytotoxic benzophenanthridines as phytoalexins at the cellular surface and at the same time prevents self-intoxication by keeping their cytoplasmic concentration below critical limits (see Fig. 1). Loss of NADPH, which can occur in aged cells or after the plasma membrane permeability is compromised, leads to cytotoxic effects, such as DNA intercalation and enzyme inhibition. Thus, sanguinarine reductase is a key component in the protection of phytoalexin-producing cells from their own toxin. The enzyme was first detected in protein extracts from leaves and roots of Eschscholzia and isolated from cells of suspended culture (11). This study describes the cloning, sequencing, heterologous expression, and site-directed mutagenesis of the gene-encoding sanguinarine reductase. Homology modeling of the active site provides insights into the evolutionary origin of this enzyme and its catalytic mechanism.

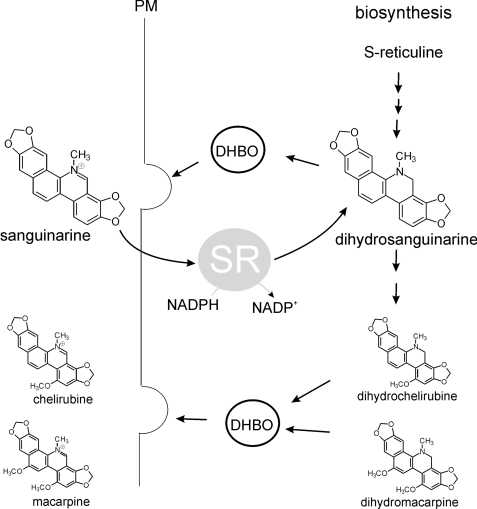

FIGURE 1.

Sanguinarine reductase and the metabolism of benzophenanthridines (according to Refs. 3 and 11). The last step of benzophenanthridine biosynthesis, catalyzed by dihydro-benzophenanthridine oxidase (DHBO), occurs in vesicles that export the oxidized alkaloids across the plasma membrane (PM). External benzophenanthridines, preferentially sanguinarine, are reabsorbed (by an unknown transport step) and, in the cytoplasm, are immediately reduced by the NADPH-dependent soluble enzyme sanguinarine reductase. The resulting dihydrosanguinarine is further decorated by the late reactions of alkaloid biosynthesis. Final products are symbolized by chelirubine and macarpine but contain more diverse benzophenanthridines.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell suspensions of E. californica were cultured and maintained in a 9–10 day growth cycle in Linsmaier-Skoog medium supplemented with the hormones 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid and α-naphthalene acetic acid (1 μm each). Cultivation was carried out on a gyratory shaker (100 rpm) at 24 °C under continuous light (∼7 μmol·m−2·s−1).

Preparation of Native Sanguinarine Reductase Protein

The sanguinarine reductase protein of E. californica was prepared from the soluble proteins of cell suspension cultures and purified to homogeneity by a fast protein liquid chromatography-based procedure (11), which includes a typical purity test.

Partial Sequencing of the Sanguinarine Reductase Protein

5 μg of SR2 protein in 100 μl of 1% (w/v) ammonia bicarbonate buffer, pH 8.0, was reduced with 10 mm dithioerythritol, alkylated with 2% (w/v) 4-vinylpyridine, ultrafiltered, and dissolved in 50 mm fresh ammonia bicarbonate buffer, pH 8.0. 50 μl containing 1 μg of protein were digested with 200 ng of trypsin (sequencing grade). The resulting peptide mixture was separated by high pressure liquid chromatography, and the peak fractions obtained were analyzed in a matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight reflector mass spectrometer (REFLEX II, Bruker Daltonik, Bremen, Germany). Eight peptides were identified by their mass peaks, isolated, and subjected to N-terminal sequencing by the standard EDMAN procedure.

PCR-based Screening for the Sanguinarine Reductase Gene

Based on the codon usage table of E. californica, which can be found on the Kazusa Web site, a series of primers was derived from the previously mentioned peptide sequences and tested for their ability to amplify gene fragments via PCR from a cDNA library of E. californica, which served as template. The library had been established by GATEWAYTM technology with the CloneMinerTM kit (Invitrogen) (12). PCR was performed in an Eppendorf Mastercycler. The primers (F3, GAGGTTAGAGGTCTGGTTAG (forward) and R22, TGTTCAGCCTTTCTCTTCCA (reverse)), allowed the highest amplification of a 500-bp DNA fragment from the SR gene. This product was sequenced and used to generate primers for another PCR (forward, F12: TATCCAGAACAAGTTGATTGG; reverse, R22: see above). In this way, a 170-bp DNA fragment was amplified, which encodes a peptide sequence of the suggested active site. This DNA fragment was used as a probe for cDNA library screening (after labeling with alkaline phosphatase by the AlkPhosDirect labeling kit, GE Healthcare). 10 SR-positive clones were obtained, which were subcultured, and the plasmids were isolated (Wizard® Plus SV Minipreps DNA purification system, Promega) and subsequently tested for the presence of the SR gene by PCR with another pair of gene-specific primers (forward, F3; reverse, R30: AAAGGAGTAGTAACTTGAGA).

Cloning the SR Gene

A plasmid containing the complete SR gene was cloned in the pET23d vector and amplified in Escherichia coli, strain XL1 BLUE. To this end, the cDNA clone isolated from the Eschscholzia cDNA library (cf. above) was used as a template in a PCR with primers covering the 5′ and 3′ end of the SR gene (forward, F1: GCACCATGGCAGATTCATC; reverse: CGTCTCGAGAAAAGGAGTAGTAAC).

These primers contained restriction sites for NcoI and XhoI, respectively, that allowed the digestion and cloning of the obtained DNA fragments. These were isolated and ligated to the plasmid pET23d, which had been digested previously with the same restriction enzymes. The resulting plasmid was used to transform the E. coli strain XL1 Blue via electroporation. After pulsing and phenotypic expression, bacterial cell suspension was plated on LB-agar containing 100 μg/ml ampicillin and grown overnight at 37 °C. Bacteria of 3–5 colonies were subcultured, and the plasmids were isolated (cf. above) and sequenced. Plasmids containing the correctly inserted SR gene were used for the preparation of the recombinant enzyme.

Transformation of E. coli and Preparation of Recombinant Sanguinarine Reductase

Submerged cultures of E. coli BL21 were transformed with the plasmid pET23d, which contains the complete cDNA of the Eschscholzia californica sanguinarine reductase, wild type or mutated, fused with a His6 coding region. The bacteria were lysed by freezing and thawing in Tris/HCl buffer, 10 mm, pH 7.0, containing 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and treatment with lysozyme and RNase. The 100,000 × g supernatant was applied to a 1 ml Ni2+-Sepharose column (His-Trap, GE Healthcare), and the His-tagged protein was eluted with a gradient of 0–100 mm imidazole.

Site-directed Mutagenesis

Mutagenesis of the SR gene was performed via PCR on the circular plasmid pET23d, followed by digestion of the products with the restriction enzyme DpnI, which selectively splits methylated DNA (13). The used primers are collected in supplemental Table S1.

Activity Assay of Sanguinarine Reductase

SR enzyme activity was measured as the rate of formation of dihydrosanguinarine from added sanguinarine, i.e. an increase in fluorescence excited at 360 ± 20 nm and emitted at 460 ± 50 nm. Measurements were done in eight parallel assays in a 96-microwell plate, and the emission was monitored with a Dynatech fluorescence reader. Each well received 200 μl 10 mm Tris/HCl, pH 7.5, which contained an NADPH-regenerating system consisting of 1 mm glucose-6-phosphate, 20 μm NADP, and 10 milliunits/ml of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase, together with the enzyme to be examined. After 5 min of preincubation, the reaction was started by adding 70 μl of aqueous sanguinarine solution to reach the desired substrate concentration (0.5–4 μm), plus 2 mm glutathione (cf. below). The reaction was stopped after 10 s by adding 30 μl 1 m HCl. To approximate initial rates of conversion and to avoid inhibitory effects of the accumulating dihydrosanguinarine (cf. below), the concentration of enzyme protein was adjusted to convert <15% of the added sanguinarine. The product was quantified via calibration with dihydrosanguinarine (prepared from sanguinarine by reduction with NaBH4, 14). The spontaneous chemical conversion of sanguinarine, measured in parallel samples without enzyme, attained a value of <5% of the conversion rates of the wild type and up to 50% of the low-performing mutant enzymes. These data were subtracted from the fluorescence increase. Kinetic parameters (Km, Vmax) were obtained by nonlinear fitting of graphs showing initial conversion rates versus corresponding sanguinarine concentrations (GraphPad Prism 5 software, GraphPad, Inc.).

Sanguinarine reductase is inhibited irreversibly by its product, dihydrosanguinarine. As shown in supplemental Fig. 2, 0.1 μm dihydrosanguinarine exerts a strong inhibition that is not overcome by increasing substrate concentrations. This explains why the conversion of sanguinarine with NADPH does not saturate but slows down after the product has reached a threshold concentration (supplemental Fig. 2) (11). The conversion of sanguinarine with NADH displays saturation kinetics but proceeds at a much slower rate than with NADPH (∼25%; cf. Ref. 11).

In the present study, we assayed the kinetic parameters of purified sanguinarine reductase and mutant enzymes under conditions that likely prevail in the cytoplasm (concentration of NADPH far higher than that of NADH (29); 2–3 mm glutathione). Initial rates of sanguinarine reduction were thus determined with NADPH and in the presence of 2 mm glutathione. The latter compound spontaneously complexes sanguinarine (15) with a KD of 400 μm.3 Under such conditions, the substrate supply is controlled and stabilized by the dissociation of the sanguinarine-glutathione complex. Consequently, the rate of product formation slows down to ∼10% of the initial rate, and the enzyme displays saturation kinetics without significant product inhibition (supplemental Fig. 2). The resulting kinetic constants, especially the apparent Km, are therefore different from earlier estimates, obtained with NADH and in the absence of glutathione (11).

In intact cells, sanguinarine reductase most probably is not deactivated by its product, as dihydrosanguinarine is rapidly derivatized to alkaloids that are noninhibitory to the enzyme (11). Moreover, the decrease in product formation due to the complexing of sanguinarine with glutathione is likely to occur in the alkaloid-producing cells as well; the glutathione concentration of the cytoplasm of Eschscholzia cells is close to 2 mm, as determined by fluorescence mapping with the probe monochlorobimane (16).

Molecular Modeling

All calculations were performed on a Pentium IV 2.2 GHz-based Linux cluster. Using the molecular modeling program MOE 2008.10 (Chemical Computing Group), the SR sequence was aligned with the x-ray structure of 1XQ6 (chain A) using the BLOSOM35 substitution matrix (see Fig. 3) (17, 18). Ten structures were generated with subsequent energy minimization using the AMBER99 force field (19) and Born-Sovation (20). All structures were checked with respect to stereochemical quality with the PROCHECK software (21). Finally, all parameters for a good stereochemical quality of the structures were fulfilled by PROCHECK (88.4% in most favored region, 10.7% in additionally allowed regions, and 0.9% in generously allowed regions; no outliers). Except for two residues (Val105 and Tyr119), which are located at the inserted loop region of SR, the PROCHECK analysis showed that all residues are in favored or allowed regions. The conformation of bound NADPH was taken over from the template protein by superposition of the backbone structures of the SR model and of the 1XQ6 x-ray structure, followed by merging the cosubstrate to the model and subsequent energy optimization. The substrate sanguinarine was docked in the ethanolamine form to the active site using the automatic docking program GOLD (Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre; 22) with standard values given by the program. From the resulting 30 docking arrangements, the one with expected orientation of the ethanolamine close to NADPH and the active site S153 was used for further energy refinement to capture slight induced fit modifications of the protein active site. (All amino acid residues of the protein are fixed during the docking procedure.) The visual analysis of the docking results and the comparison between SR and 1XQ6 were carried out using MOE 2008.10 software (Chemical Computing Group).

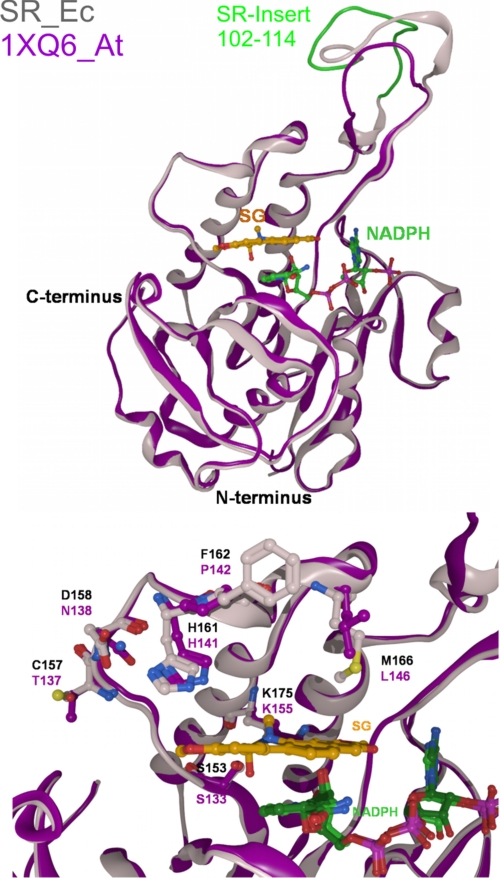

FIGURE 3.

Three-dimensional homology model of sanguinarine reductase (gray), based on the template protein 1XQ6 (magenta), with the docked substrate sanguinarine (SG) and NADPH.

Anti-sera Preparation and Western Blotting

Two laboratory rabbits were each injected intraperitoneally with 750 μg of the recombinant, His-tagged proteins SR or 1XQ6, dissolved in 300 μl Tris buffer (10 mm, pH 7.0) and mixed with 300 μl of complete Freund's adjuvant. Booster injections were made after 4 and 5 weeks with the same volumes containing 500 μg of antigen and incomplete Freund's adjuvant. After 6 weeks, the animals were bled, and the serum was tested for the desired antibodies by competitive enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay with the same antigens. The IgG fraction of the most reactive serum of each group was precipitated with 50% ammonia sulfate, resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (10 mm, pH 7.5, and 150 mm NaCl) to give the original serum volume, and dialyzed for 24 h with the same buffer at 4 °C.

For Western analysis, the recombinant antigens and protein extracts from cell suspension cultures were separated by SDS-PAGE, and the proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (HybondTM-ECL, GE Healthcare) by semidry blotting. After a 24-h incubation with a blocking agent (Roti-BlockTM, Roth, Germany) at 4 °C, the blots were exposed for 1 h at room temperature to the indicated antisera and diluted 1:5000 with phosphate-buffered saline. After several washing steps, the bound primary antibodies were detected by bovine anti-rabbit antibodies labeled with horseradish peroxidase (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and visualized with the ECL detection reagent (GE Healthcare).

RESULTS

The Gene and Protein of Sanguinarine Reductase

Sanguinarine reductase (NAD(P)H:sanguinarine oxidoreductase) was isolated from cultured cells of E. californica as a soluble monomeric protein of 29.4 kDa that catalyzes the NAD(P)H-dependent reduction of benzophenanthridine alkaloids, preferentially sanguinarine (11, Fig. 1). In the present study, the amino acid sequence of SR was determined in two steps. First, eight peptides obtained by trypsin digestion of the pure protein were sequenced by the EDMAN procedure, thus covering 59% (162 amino acids) of the total protein (271 amino acids). Second, a collection of gene-specific primers was derived from the tryptic peptides and used to identify the coding DNA of sanguinarine reductase via PCR in a cDNA library of Eschscholzia established in our lab (23). A full-length cDNA clone was obtained from this library and also identified in an EST library of E. californica available at the Floral Genome Network (Cornell University). It contained both the sequence information from the tryptic peptides and of various DNA fragments amplified by PCR. Finally, the cDNA of SR was expressed in bacteria as a His-tagged recombinant protein, which after isolation yielded a functional enzyme (cf. below). Supplemental Fig. 1 displays the complete cDNA and protein sequence of sanguinarine reductase. The complete gene and protein sequence of SR has been submitted to the NCBI Database under accession no. GU338458. In silico analysis shows that a variety of plant proteins share high sequence similarity with this enzyme (Fig. 2, top). All homologs are members of the superfamily of “Rossmann fold NAD(P)H/NAD(P)+ binding proteins;” among the annotated proteins of this family, the closest sequence similarity is shown by 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenases and NAD-dependent epimerases/dehydrogenases. Among these homologs is a protein of unknown function that provides x-ray structural data that can be used as a template for the generation of a three-dimensional homology model (cf. below). The SR protein contains some unique residues that are not found in any of its homologs (Fig. 2, top). Among them, Cys157 deserves special attention; stoichiometric amounts of the SH-reactive compound iodoacetamide (2 nmol per nmol protein) almost completely block the initial activity of the purified genuine (native) enzyme (data not shown). As only two Cys are contained in the protein and Cys232 is conserved among most homologs including 1XQ6, this suggests that Cys157 is involved in the catalytic process.

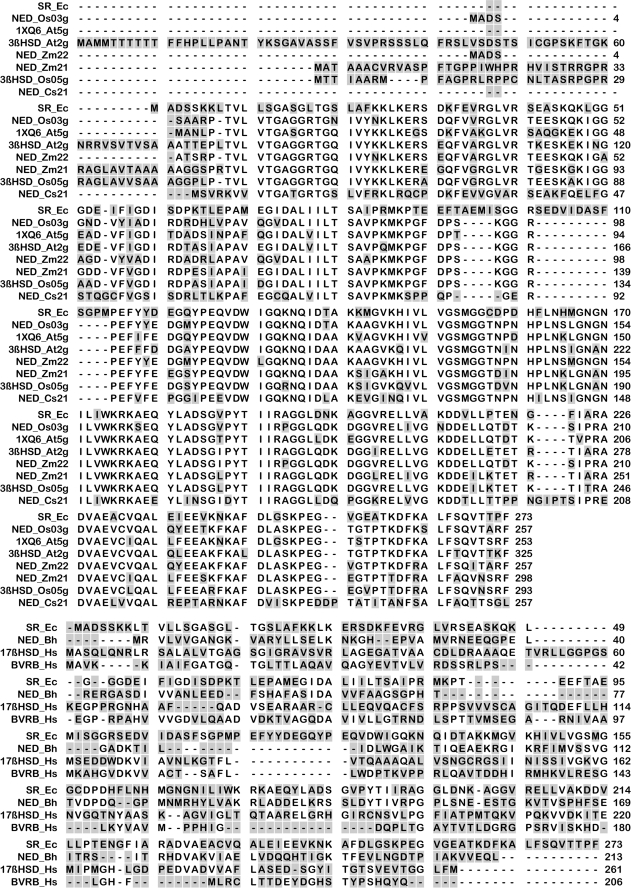

FIGURE 2.

Top, alignment of amino acid sequences of sanguinarine reductase and its closest sequence homologs. The NCBI Database was screened with the complete peptide sequence of sanguinarine reductase, using the BLASTp algorithm and the BLOSUM62 matrix. Nonidentical amino acids are marked in gray. NED, NAD-dependent epimerase/dehydratase; 3βHSD, 3-β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase. Supplemental Table 2 provides details of these proteins. Bottom, alignment of amino acid sequences of sanguinarine reductase and its closest structural homologs. The sequences refer to the three proteins with the highest structural similarities to the three-dimensional homology model of sanguinarine reductase, as shown in Figs. 4 and 5. Nonidentical amino acids are marked in gray. Supplemental Table 2 provides details of these proteins.

Homology Modeling Reveals the Catalytic Site of SR

To gain insight into the structure of the SR protein and its catalytic center, available x-ray data of the aforementioned 1XB6 protein from Arabidopsis thaliana was used as a basis for homology modeling. The resulting three-dimensional model (Fig. 3) contains the basic topology of a Rossmann fold NAD(P)H/NAD(P)+-binding site, with the typical GX(X)GXXG motif close to an α-helical domain (Gly14–20 in Fig. 2, top). Based on this model, the Protein Data Bank was searched for conserved three-dimensional structures using the FATCAT web server. As seen in Fig. 4, the sanguinarine reductase model displays close structural homologies with domains of NAD-dependent epimerase/dehydratase of Bacillus halodurans (NED-Bh), human biliverdin IX β reductase (BVRB-Hs), and human 17β hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase, type 8 (17βHSD-Hs) (cf. supplemental Table 2 for details of these proteins).

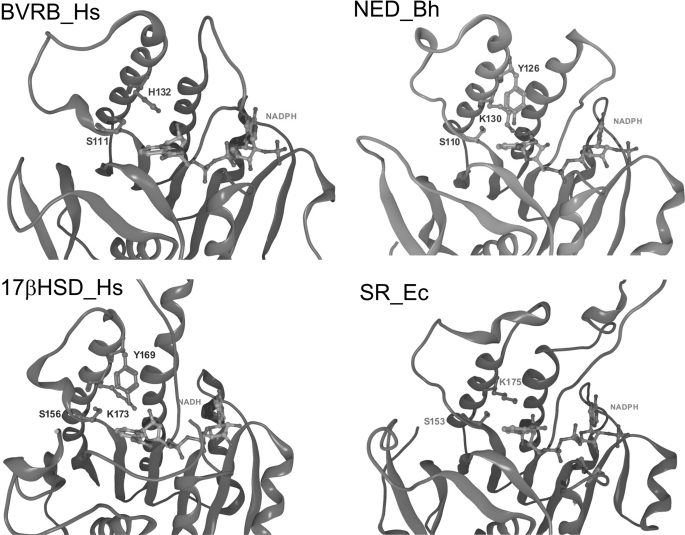

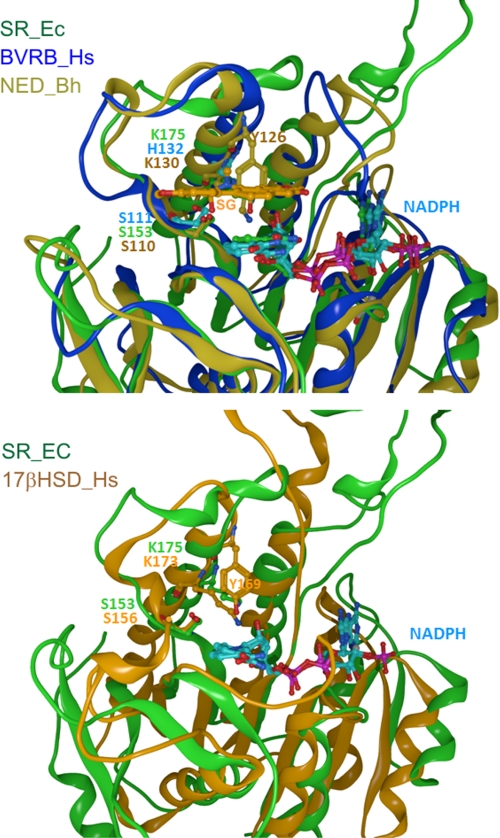

FIGURE 4.

The proteins with closest structural similarities to the three-dimensional model of sanguinarine reductase. The FATCAT Web server was used to screen the Uniprot_kb database with the three-dimensional data of 1XQ6. Structurally related proteins were identified with a backbone root meant square deviation value <2.5 Å. Numbers refer to substrate binding amino acids. SR_Ec, three-dimensional model of sanguinarine reductase, resolution 2.35 Å; BVRB-Hs, resolution 1.68 Å; 17βHSD_Hs, resolution 2.37 Å; and NED-Bh, resolution 1.86 Å.

The high structural coincidence of SR with these enzymes, which is demonstrated by the superpositions in Fig. 5, spans the Rossmann fold area and the adjacent substrate-binding site. The three enzymes contain similar pairs of substrate-interacting amino acids that consist of Ser plus a basic amino acid (Fig. 5): in human BVRB, the tetrapyrrole substrates are bound at Ser111 and His132 (although the latter may not directly be involved in the reaction (24, 25)); in human 17β-HSD type 8, estradiol is bound at Ser156 plus Lys173 (26), whereas 17β-HSD type 1 contains Ser142 and Lys159 as homologous substrate-interacting sites (27); in the bacterial NED-Bh, Ser110 plus Lys130 are at homologous positions. The latter two enzymes also contain a Tyr, which takes part in the catalytic process (Tyr126 and Tyr169, respectively). Analogously, the alkanolamine form of sanguinarine could be docked optimally into the homology model of sanguinarine reductase; the OH at C6 of the alkaloid is fixed by an H-bond to Ser153, which, in turn, is stabilized by Lys175. Thus, the C6 of the alkaloid substrate is positioned at a catalytic distance of 3.4 Å to the hybrid ion-transferring carbon of NADPH. In the template protein 1XQ6, which has no sanguinarine-reducing or other known enzymatic activity, similar positions are occupied by the amino acids Ser133 and Lys155. The high structural similarity between SR and its plant, human, and bacterial homologs (1XQ6, BVRB-Hs, 17βHSD-Hs, and NED-Bh) points to a similar mode of hydrogen transfer from NADPH to the respective substrates. Interestingly, the coinciding domains consist mainly of different amino acids as demonstrated by their low peptide sequence homology (Fig. 2, bottom). An overview of all homologs of sanguinarine reductase used in this study, identified by either amino acid sequence or three-dimensional structural similarity, is given in supplemental Table S2. Neither the closely homologous plant protein 1XQ6 nor any of the other modeled proteins shows sanguinarine-reducing activity. This emphasizes the importance of structural specifics of the SR protein as they are found in the upper, poorly conserved part of the SR molecule (Fig. 3 and see Fig. 7). First, near the putative catalytic site, i.e. close to the Rossmann fold area, SR contains a triad of equidistant amino acids Cys157, Asp158, and His161 that might form hydrogen bonds to one dioxolane (dioxymethylene) ring of sanguinarine. Two of these amino acids are different in the 1XQ6 template, which contains Thr instead of Cys and Asn instead of Asp. Second, the other dioxolane ring of the sanguinarine molecule is at H-bonding distance to Lys175. Third, Met166 is likely to undergo hydrophobic interactions with the aromatic ring system. This amino acid is localized at the border of a hydrophobic catalytic pocket and constricts its shape. (1XB6 contains Leu in the homologous position.) Fourth, apart from the active site, sanguinarine reductase contains two inserts that are 13- and 4-amino acids long and not present in any of the known SR homologs (cf. Fig. 2, top). In particular, the longer insert (cf. Figs. 3 and 5) could have a significant impact on the geometry of the active site, which cannot, however, be predicted within the limits of the present homology model.

FIGURE 5.

Overlays of catalytic sites of sanguinarine reductase and homologous proteins. SR_Ec, three-dimensional model of sanguinarine reductase; BVRB_Hs, human biliverdin IX beta reductase; 17βHSD_Hs, human hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 8; NED_Bh, putative NAD-dependent epimerase/dehydratase, Bacillus halodurans. Docked NADPH is shown in both panels, and docked sanguinarine (SG) is shown in the upper panel.

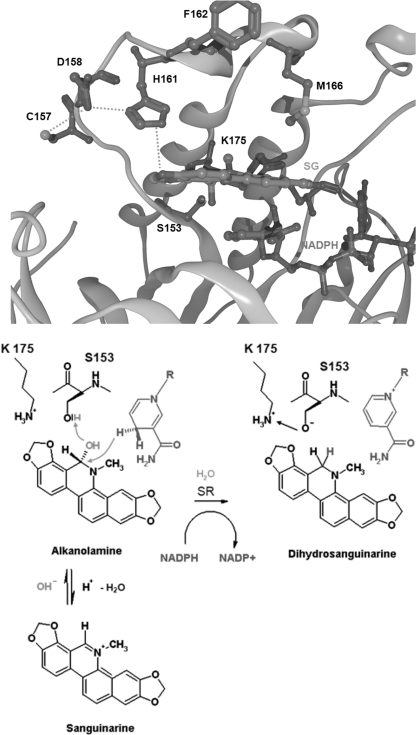

FIGURE 7.

Proposed mechanism of catalysis by sanguinarine reductase. SG, sanguinarine.

Essential Amino Acids of the Catalytic Center of Sanguinarine Reductase

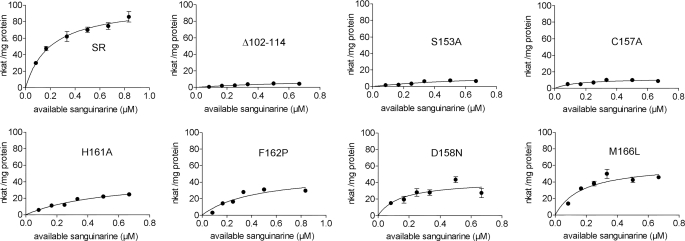

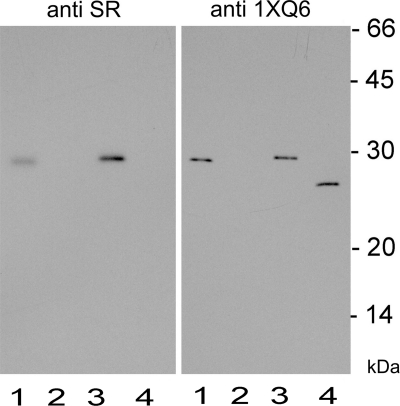

Site-directed mutagenesis was used to confirm the role in the catalytic process of the key amino acids as they were predicted by the three-dimensional model of SR. A series of recombinant, His-tagged mutant proteins were obtained in which selected amino acids were exchanged (mostly for Ala to minimize effects on secondary structure and conformation). The data collected in Table 1 and Fig. 6 have several implications. Even though the Km of some mutant enzymes was obtained with relatively low precision (due to limitations in the detection of nanomolar product concentrations in the presence of excess sanguinarine), a comparison of all kinetic parameters in Table 1 clearly indicates amino acids with a strong impact at the catalytic process. First, Ser153 is essential for SR activity, which supports the involvement of the Ser-Lys pair in the catalytic process, as proposed by the model. (As this pair is present at similar positions in all plant homologs and both amino acids are known to cooperate in catalysis, we did not consider the mutation of Lys175.) Second, Cys157 and His161 are likewise important for catalysis. Although the replacement of either amino acid causes a decay of catalytic efficiency to ∼15%, the mutation of His, but not of Cys, significantly increases the Km, which is consistent with a role of His in substrate binding. Cys most probably acts as the primary H-donor. Indirect evidence suggests that Thr can replace Cys without completely destroying SR catalysis; in some plants, SR activity was detected, although the homologous open reading frames contained only Thr codons at this position.4 Third, the exchange of Asp158 for Asn (as it is present in 1XQ6) does not affect enzyme activity severely. Asp obviously contributes to the H-bond arrangement more by its carbonyl moiety than its acidic −OH. Taken together, the latter data support the existence and function of the predicted catalytic triad Cys157, Asp158, and His161. The low catalytic activity remaining after the exchange of Cys and His may reflect some ability of water molecules to serve as donors or acceptors in the H-bond system. Fourth, the exchange of Met166 for Leu does not significantly affect the Km and catalytic efficiency, which is consistent with the prediction of the model that Met contributes to the shape of the hydrophobic catalytic pocket but not to substrate binding during catalysis. Its exchange for another hydrophobic amino acid (Ala) therefore might not significantly reduce the catalytic power. Fifth, the presence of Phe162 instead of Pro (as present in 1XQ6) appears also an important peculiarity of SR. Due to its distance from the catalytic center, Phe162 may provide a higher flexibility to the active site, i.e. a relief from the rigidity caused by Pro, rather than a direct influence at the catalytic process. Sixth, the deletion of the insert Ser102–Met114 results in the most severe decrease of enzymatic activity. This peptide apparently forms a loop in an area distant to the NADP-binding domain and the sanguinarine-binding site (cf. Figs. 3 and 5), i.e. with no direct influence at the active center shown in Fig. 7. It appears that this insert is important for the catalytic function through a strong allosteric influence at the dynamic properties of the enzyme protein. That sanguinarine reductase and the template protein 1XQ6 significantly differ in their spatial surface structure is supported by our immunological analysis; a rabbit antiserum raised against the recombinant SR protein detects this protein on Western blots but not the recombinant 1XQ6 protein, whereas an antibody against the recombinant 1XQ6 detects both proteins (Fig. 8). As the loop 102–114 represents the main structural difference between the three-dimensional structures of both proteins, it is likely that the anti-SR antibody preferentially detects this epitope and that our model correctly positioned this loop at the surface of the SR protein.

TABLE 1.

Kinetic parameters of recombinant, His-tagged sanguinarine reductase and mutants prepared by site-directed mutagenesis

Data are based on nonlinear fitting of graphs of initial rates of NADP-dependent dihydrosanguinarine formation versus sanguinarine concentration (Fig. 6). Data are means ± S.D. (n = 8); the S.D. of Vmax/Km is the calculated sum of S.D. (%) of Vmax and Km.

| Enzyme | Vmax | Km | Vmax/Km | Vmax/Km |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| nkat/mg | μm | % | ||

| SR | 100 ± 6.4 | 0.19 ± 0.04 | 531 ± 145 | 100 |

| Δ102–114, deletion | 10.7 ± 3.6 | 0.78 ± 0.41 | 13.7 ± 11.8 | 2.5 |

| S153A | 16.0 ± 6.3 | 0.75 ± 0.46 | 21.3 ± 21.1 | 4.0 |

| C157A | 12.0 ± 1.6 | 0.15 ± 0.06 | 80.0 ± 42.7 | 15.1 |

| H161A | 47.9 ± 8.2 | 0.58 ± 0.17 | 82.6 ± 38.0 | 15.6 |

| F162P | 51.2 ± 7.1 | 0.44 ± 0.12 | 116 ± 47.7 | 22.0 |

| D158N | 46.8 ± 8.1 | 0.19 ± 0.10 | 250 ± 174 | 47.1 |

| M166L | 61.5 ± 6.2 | 0.18 ± 0.05 | 342 ± 129 | 64.5 |

FIGURE 6.

Initial rates of NADPH-dependent product formation versus substrate concentration by wild type and mutant sanguinarine reductases used in this study. All enzymes are His-tagged, recombinant proteins. The assay was run in the presence of 2 mm glutathione, which complexes the substrate sanguinarine. Free substrate concentrations are thus estimated from the complex dissociation constant (400 μm) and the applied sanguinarine concentration (0–4 μm). Data are means with SD (n = 8), corrected for the (small) rates of spontaneous product formation in the absence of enzyme.

FIGURE 8.

Sanguinarine reductase and its close plant homolog 1XQ6 can be distinguished immunologically. Western blots were prepared after SDS-PAGE of the recombinant, His-tagged proteins, sanguinarine reductase or 1XQ6, and of homogenates made from cell suspension cultures of E. californica and A. thaliana. The blots were incubated with rabbit polyclonal antisera raised against the recombinant proteins 1XQ6 or SR, as indicated. Bound primary antibodies were visualized by peroxidase-tagged anti-rabbit antibodies (as described under “Experimental Procedures”). lane 1, cell homogenate of E. californica, 2 μg of protein; lane 2, cell homogenate of A. thaliana, 2 μg of protein; lane 3, recombinant sanguinarine reductase, His-tagged, 5 ng of protein; lane 4, recombinant 1XQ6, His-tagged, 5 ng protein. The anti-SR anti-serum detects the recombinant SR protein and the genuine SR protein in the cell extract of Eschscholzia. The anti-1XQ6 anti-serum detects the recombinant 1XQ6 protein and the SR protein. (The protein 1XQ6 is not expressed in the used cell culture of Arabidopsis but was detectable with the same anti-serum in a protein extract of Arabidopsis plants; see footnote 4.)

Seen together with the complete lack of sanguinarine reducing activity of the 1XQ6 protein, the properties of the mutant enzymes support the three-dimensional model of sanguinarine reductase as introduced in Fig. 3. Based on this model and in analogy with mechanistic data of biliverdin IX β reductase (24, 28), the following catalytic mechanism is proposed (Fig. 7): the alkanolamine form of sanguinarine is fixed in a binding pocket, mainly consisting of hydrophobic amino acids, by the conserved Ser153. Both dioxolane rings of the alkaloid are bound by a) a triad of H-bonds originating from Cys157 connected to Asp158 and His161 and b) the side chain of Lys175. Electron transfer is initiated by attacking the C6 of sanguinarine with the hydride ion of NADPH and the OH group at C6 with a proton originating from Ser153. The anionic form of Ser is then stabilized by the −NH3+ group of Lys175. Removal of OH− followed by water formation completes the reduction process.

DISCUSSION

Our data clearly show that sanguinarine reductase is a member of the Rossman fold enzyme superfamily. The available x-ray structures indicate that members of this family share high structural similarity even over large distances of molecular evolution. The low sequence homology between the bacterial, animal, and plant members further shows that essential similar structural elements are formed by different peptide sequences and thus might have evolved independently from several ancestor proteins. Although the plant homologs of SR that were identified by their high sequence homology bear little sequence similarity with the structural homologs identified among the available x-ray structures of bacterial and human proteins, they display similar enzyme activities, i.e. mostly NAD-dependent sugar phosphate epimerases/dehydratases or hydroxysteroid dehydrogenases/isomerases. In all cases, the essential catalytic domain is formed by a Rossmann-type NAD(P)H-binding site plus a neighboring area containing a substrate interacting dyad of Ser and Lys/His. The numerous homologs found in plant and animal protein databases (e.g. >100 plant proteins with an e value <1e−10) indicate that proteins with this core structure are widely distributed. It appears that sanguinarine reductase evolved from such an ubiquitously available precursor of the Rossmann superfamily via two main mutations, which were positively selected under the pressure of benzophenanthridine toxicity: 1) an insert of 13 amino acids (Ser102–Met114) and 2) the change of Thr137 to Cys157, which allows to establish the H-bond triad Cys157, Asp158, and His161. We do not exclude that other specific elements of the SR molecule, which have not yet been investigated by mutation, might also contribute to the catalytic activity, e.g. around the insert Ala94– Ile97.

The essential function of sanguinarine reductase as protection against self-intoxication is supported by our actual preliminary findings that the enzyme is overexpressed upon contact of cultured cells with sanguinarine or other benzophenanthridines and that the activity of sanguinarine reductase as well as typical sequences of the coding DNA are present in a variety of benzophenanthridine-producing plants.4 An analysis of evolutionary relationships arising from these data is under way in our laboratory.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The help with the EDMAN sequencing of sanguinarine reductase by Drs. K.-P. Rücknagel and A. Schierhorn, Max-Planck-Forschungsstelle für Enzymologie der Proteinfaltung (Halle, Germany) is gratefully acknowledged. We also thank Professor G. Sawers, Martin-Luther-University of Halle-Wittenberg, Institute of Biology, Department of Microbiology, Halle, Germany for linguistic help.

This work was supported by the German Research Council (Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft).

The amino acid sequence of this protein can be accessed through NCBI Protein Database under NCBI accession number GU338458.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Tables S1 and S2 and Figs. 1 and 2.

H.-H. Rüttinger, M. Vogel, and W. Roos, unpublished data.

H. Müller and W. Roos, unpublished data.

- SR

- sanguinarine reductase

- BVRB-Hs

- human biliverdin IX β reductase

- 17βHSD-Hs

- human 17β hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase

- NED-Bh

- NAD-dependent epimerase/dehydratase of Bacillus halodurans.

REFERENCES

- 1.Zenk M. H. (1994) Pure Appl. Chem. 66, 2023–2028 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ziegler J., Facchini P. J. (2008) Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 59, 735–769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Klein M., Roos W. (2009) in Plant-derived Natural Products: Synthesis, Function, and Application (Osbourn A. E., Lanzotti V. eds) pp. 229–269, Springer Science+Business Media, New York, New York [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blechert S., Brodschelm W., Hölder S., Kammerer L., Kutchan T. M., Mueller M. J., Xia Z. Q., Zenk M. H. (1995) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 92, 4099–4105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roos W., Evers S., Hieke M., Tschope M., Schumann B. (1998) Plant Physiol 118, 349–364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haider G., Kislinger T., Kutchan T. M. (1997) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 241, 606–610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schmeller T., Latz-Brüning B., Wink M. (1997) Phytochemistry 44, 257–266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wink M., Schmeller T., Latz-Brüning B. (1998) J. Chem. Ecol. 24, 1881–1937 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Faddeeva M. D., Beliaeva T. N. (1997) Tsitologiia 39, 181–208 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ulrichová J., Dvorák Z., Vicar J., Lata J., Smrzová J., Sedo A., Simánek V. (2001) Toxicol. Lett. 125, 125–132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weiss D., Baumert A., Vogel M., Roos W. (2006) Plant Cell Environ 29, 291–302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schwartze W. (2007) The Cellular Control of Phospholipase A2 as an Element of Signal Transfer That Triggers Alkaloid Biosynthesis in Eschscholzia californica. Ph.D. thesis, Martin-Luther-University, Halle, Germany [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weiner M. P., Costa G. L., Schoettlin W., Cline J., Mathur E., Bauer J. C. (1994) Gene 151, 119–123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tanahashi T., Zenk M. H. (1990) Phytochemistry 29, 1113–1122 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bartak P., Simanek V., Vlčkova M., Ulrichova J., Vespalec R. (2003) J. Phys. Org. Chem. 16, 803–810 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Herrmann S. (2003) Investigation of the GSH-Dependence of PLA2 Activity in Eschscholzia californica by Means of Fluorescence Microscopy. Diploma thesis, Martin-Luther-University, Institute of Pharmaceutical Biology, Halle, Germany [Google Scholar]

- 17.Henikoff S., Henikoff J. G. (1992) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 89, 10915–10919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Henikoff S., Henikoff J. G. (1993) Proteins 17, 49–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Case D. A., Cheatham T. E., 3rd, Darden T., Gohlke H., Luo R., Merz K. M., Jr., Onufriev A., Simmerling C., Wang B., Woods R. J. (2005) J. Comput. Chem. 26, 1668–1688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pellegrini E., Field M. J. (2002) J. Phys. Chem. 106, 1316–1326 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Laskowski R. A., MacArthur M. W., Moss D. S., Thornton J. M. (1993) J. Appl. Crystallogr. 26, 283–291 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jones G., Willett P., Glen R. C., Leach A. R., Taylor R. (1997) J. Mol. Biol. 267, 727–748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Viehweger K., Schwartze W., Schumann B., Lein W., Roos W. (2006) Plant Cell 18, 1510–1523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pereira P. J., Macedo-Ribeiro S., Párraga A., Pérez-Luque R., Cunningham O., Darcy K., Mantle T. J., Coll M. (2001) Nature Struct. Biol. 8, 215–220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith L. J., Browne S., Mulholland A. J., Mantle T. J. (2008) Biochem. J. 411, 475–484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen Z., Kastaniotis A. J., Miinalainen I. J., Rajaram V., Wierenga R. K., Hiltunen J. K. (2009) FASEB J. 23, 3682–3691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lukacik P., Kavanagh K. L., Oppermann U. (2006) Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 248, 61–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maines M. D. (2005) Physiology 20, 382–389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moller I. M. (2001) Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 52, 561–591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.