Abstract

In neural stem cells, basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) and epidermal growth factor (EGF) promote cell proliferation and self-renewal. In the bFGF- and EGF-responsive neural stem cells, β1-integrin also plays important roles in crucial cellular processes, including proliferation, migration, and apoptosis. The cross-talk of the signaling pathways mediated by these growth factors and β1-integrin, however, has not been fully elucidated. Here we report a novel molecular mechanism through which bFGF or EGF promotes the proliferation of mouse neuroepithelial cells (NECs). In the NECs, total β1-integrin expression levels and proliferation were dose-dependently increased by bFGF but not by EGF. EGF rather than bFGF strongly induced the increase of β1-integrin localization on the NEC surface. bFGF- and EGF-induced β1-integrin up-regulation and proliferation were inhibited after treatment with a mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase inhibitor, U0126, which indicates the dependence on the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway. Involvement of β1-integrin in bFGF- and EGF-induced proliferation was confirmed by the finding that NEC proliferation and adhesion to fibronectin-coated dishes were inhibited by knockdown of β1-integrin using small interfering RNA. On the other hand, apoptosis was induced in NECs treated with RGD peptide, a small β1-integrin inhibitor peptide with the Arg-Gly-Asp motif, but it was independent of β1-integrin expression levels. Those results suggest that regulation of β1-integrin expression/localization is involved in cellular processes, such as proliferation, induced by bFGF and EGF in NECs. The mechanism underlying the proliferation through β1-integrin would not be expected to be completely identical, however, for bFGF and EGF.

Keywords: Epithelial Cell, Extracellular Matrix, Glycoprotein, Growth Factors, Integrin, Lipid Raft, Neural Stem Cell, N-Glycosylation

Introduction

Neural stem cells (NSCs)3 are defined as undifferentiated neural cells with a high potential for proliferation and the capacity for self-renewal with retention of multipotency (1–4). During development, NSCs have the capability to generate brain-forming cells, such as neurons, astrocytes, and oligodendrocytes. The application of NSCs to cell-based transplantation is a very attractive and promising strategy for regenerative and restorative medicine (5–7).

The fate of NSCs (self-renewal, proliferation, differentiation, survival, and death) is regulated by intracellular programs mediated by a number of transcription factors or epigenetic modifications, including DNA methylation, histone modification, and non-coding RNA expression (8–11). Furthermore, the signaling pathways of various growth factors, the extracellular matrix, and cell adhesion molecules present in specific microenvironments or niche in NSCs are also known to play important roles in maintenance of the stem cell population (12–18). In particular, basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) and epidermal growth factor (EGF) are primary mitogens to promote proliferation of NSCs through the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway in vitro (19–22). The responses of NSCs to those growth factors are thought to be related to their lineage and to the microenvironment of the particular region of the brain in which they are located (23). Although both growth factors stimulate similar complements of intracellular signaling pathways, the bFGF-signaling pathway is more complex (24). The difference in the time course of the Ras-MAPK pathway by both growth factors is considered to be the cause of differential cellular responses (25).

In addition to bFGF and EGF, integrins are also important components for NSC fate regulation. The integrins are cell surface receptor proteins of extracellular matrix components, such as fibronectin, laminin, collagen, tenascin-R, and vitronectin. The integrins not only mediate cell adhesion but also modulate the signals, for instance, downstream of growth factor receptors (26–30). The integrins are heterodimeric proteins composed of α and β subunits. Five major integrin pairs, α5β1, α6β1, αvβ1, αvβ5, and αvβ8, are expressed in NSCs (31, 32). Among them, β1-integrins, a common component of certain integrin heterodimers, are highly expressed in NSCs and can be used as a marker protein for NSC selection (19, 32, 33). The β1-integrin regulates migration with β6-integrin and proliferation with αv- or α5-integrin in neural precursor cells (31). Furthermore, the β1-integrin activates the MAPK pathway in NSCs that contributes to NSC maintenance. The β1-integrin signaling synergizes with growth factor signaling and is thought to promote neural progenitor cell survival (19, 34). On the cell surface, β1-integrin is distributed in surface microdomains, such as lipid rafts (35). The β1-integrin-containing lipid rafts play important roles in coordination with Notch and the EGF receptor for the maintenance of stemness (12). However, the cross-talk of signaling pathways mediated by bFGF/EGF and β1-integrin has never been fully elucidated. In this study, we investigated the involvement of β1-integrin in bFGF- and EGF-mediated cell fate regulation in mouse embryonic neuroepithelial cells (NECs) that are rich in NSCs.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

bFGF and EGF were purchased from Peprotech (Rocky Hill, NJ). U0126 (an inhibitor of MEK) was purchased from Sigma. RGD peptide was purchased from BIOMOL (Plymouth, PA).

NEC Culture

NECs, which are known to be rich in NSCs (36), were isolated from telencephalons of an ICR strain of mouse embryos of embryonic day 14.5 (E14.5), as described previously (36, 37). NECs were cultured in N2-supplemented Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium/F-12 medium (DMEM/F-12) containing 10 or 50 ng/ml of bFGF or EGF (Peprotech) on dishes coated with poly-l-ornithine (Sigma) and bovine fibronectin (Sigma) at 37 °C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere. Mice used for cell preparation were treated according to the guidelines of the Laboratory Animal Service Committee of the Medical College of Georgia.

Immunocytochemistry

Immunocytochemical analysis of NECs was performed as described previously (38, 39). In brief, NECs cultured in N2-supplemented DMEM/F-12 with or without 1 mm RGD peptide on poly-l-ornithine- and fibronectin-coated Chamber Slides (Nalge Nunc International, Naperville, IL) were fixed with PBS containing 4% paraformaldehyde. After permeabilization and blocking with PBS containing 0.1% Triton X-100 and 1% bovine serum albumin for 1 h, the cells were stained with anti-nestin monoclonal antibody (BD Biosciences) and anti-β1-integrin polyclonal antibody (M106; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA) overnight and then with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (Invitrogen) and rhodamine-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG antibodies (Chemicon, Temecula, CA) for 2 h. Hoechst 33258 (Sigma) was used to stain the nuclei. The stained NECs were photographed under a Nikon Eclipse TE300 fluorescent microscope (Nikon Instruments, Melville, NY) equipped with a Magnafire digital charge-coupled device camera (Optronics, Goleta, CA).

Western Blot Analysis

NECs, treated with or without growth factors, a chemical inhibitor, and RGD peptide in N2-supplemented DMEM/F-12, were lysed in a lysis buffer containing 1% Triton X-100, 10 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 150 mm NaCl, 5 mm EDTA, 2 mm Na3VO4, and a protease inhibitor mixture (Sigma). Protein concentration in the lysates was measured by the Bradford method using a protein assay kit (Bio-Rad). The same amount of protein present in the lysates was denatured in Laemmli sample buffer by boiling, applied to SDS-PAGE (10% polyacrylamide gels), and then transferred to a polyvinylidene fluoride membrane (GE Healthcare). After transfer, the membrane was fixed for 30 min in 0.4% paraformaldehyde at room temperature for detection of caspase-3 (39). Western blot analysis was performed using anti-β1-integrin polyclonal antibody (M106; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), anti-β-actin monoclonal antibody (AC-15; Sigma), anti-phospho-ERK (Thr202/Tyr204) monoclonal antibody (E10; Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA), and anti-ERK polyclonal antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.). Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse IgG antibody or anti-rabbit IgG antibody (GE Healthcare) was used as the secondary antibody. Protein bands that reacted with the antibodies were detected using Western Lightning Western blot Chemiluminescence Reagent Plus (PerkinElmer Life Sciences).

Cell Surface Protein Biotinylation Assay

Cell surface localization of β1-integrin was evaluated by a cell surface protein biotinylation assay. After washing NECs three times with ice-cold PBS, proteins expressed on the cell surface were biotinylated by treating the NECs with 0.5 mg/ml EZ-link sulfo-NHS-LC-biotin (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) for 30 min in PBS at 4 °C. Excess sulfo-NHS-LC-biotin was quenched for 20 min with 100 mm glycine in PBS at 4 °C. Then NECs were washed once with ice-cold PBS and lysed with a lysis buffer containing a protease inhibitor. Biotinylated cell surface proteins in the lysates were pulled down by gentle agitation in the presence of streptavidin-conjugated agarose (EMD Biosciences, Gibbstown, NJ) at 4 °C overnight, washed three times with the lysis buffer, denatured in Laemmli sample buffer by boiling, and subjected to Western blot analysis using anti-β1-integrin and anti-β-actin antibodies.

WST-8 Assay

The number of cultured NECs was measured by WST-8 assay using Cell Counting Kit-8 (DOJINDO, Kumamoto, Japan) (40). In brief, NECs were plated onto poly-l-ornithine- and fibronectin-coated 96-well plates and cultured in N2-supplemented DMEM/F-12 with or without bFGF or EGF (10 or 50 ng/ml), 1 or 5 μm U0126, and 10 nm siRNA for 1–3 days. Then the cells were incubated with 2-(2-methoxy-4-nitrophenyl)-3-(4-nitrophenyl)-5-(2,4-disulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium (WST-8) solution for 3 h at 37 °C. The spectrophotometric absorbance of WST-8-formazan produced by the dehydrogenase activity in living NECs was measured at a wavelength of 450 nm (reference, 650 nm) using a Benchmark Plus microplate spectrophotometer (Bio-Rad).

Real-time PCR Analysis

Real-time PCR was performed as described previously (41). In brief, total RNA samples were isolated from NECs using a TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen). cDNAs were synthesized from the total RNAs as templates using SuperScript III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen). Quantitative PCR assays were run on the iQcycler (Bio-Rad) using SYBR Green (Bio-Rad) as the detection method with the following settings: 94 °C for 2 min; 26–30 cycles of 94 °C for 20 s, 60 °C for 20 s, and 72 °C for 40 s; and 72 °C for 5 min. To determine PCR efficiencies, a calibration curve was constructed by serial dilution of a cDNA pool from all of the samples. Primer sets used for PCR were as follows: 5′-TTTTGCAACACCAAGCTCAC-3′ and 5′-TGTGACCTCAGCTGACAAGG-3′ for β1-integrin; 5′-AGC CAT GTA CGT AGC CAT CC-3′ and 5′-TCT CAG CTG TGG TGG TGA AG-3′ for β-actin. All primers were custom synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA). β-Actin was detected as a control housekeeping gene.

Terminal Deoxynucleotidyltransferase-mediated dUTP Nick End Labeling (TUNEL) Staining

Apoptotic NECs were detected with a TUNEL assay. In brief, NECs were plated onto chamber slides and cultured in N2-DMEM/F-12 in the presence or absence of 1 mm RGD peptide. Then the NECs were fixed for 1 h in PBS containing 4% paraformaldehyde at room temperature and permeabilized in 0.1% sodium citrate containing 0.1% Triton X-100 for 2 min at 4 °C. The NECs were stained with fluorescein-conjugated TUNEL reaction mixture (Roche Applied Science) for 1.5 h at 37 °C and then with Hoechst 33258 for 10 min. Stained NECs were photographed under a Nikon Eclipse TE300 fluorescent microscope equipped with a Magnafire digital charge-coupled device camera.

RNAi

Double-stranded RNAi or siRNAs (21-mer) targeting β1-integrin were purchased from Qiagen (Valencia, CA). The corresponding target mRNA sequences for the siRNAs were as follows: β1-integrin-A, CCAGCTAATCATCGATGCCTA; β1-integrin-B, AGGAGAACCACAGAAGTTTA; β1-integrin-C, CCCGACATCATCCCAATTGTA; β1-integrin-D, CTGGTCCATGTCTAGCGTCAA. AllStars siRNA was used as a negative control. NECs were transfected with siRNA using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's protocol (42). In brief, cultured NECs (day 4) were incubated in Hanks' balanced salt solution for 10 min at 37 °C and then carefully collected by pipetting. The NECs (1 × 106 cells/sample) were transfected using the reverse transfection method, and plated on 6-cm dishes. β1-Integrin-specific siRNA oligomers (final concentration, 10 nm) were diluted in 100 μl of N2-supplemented DMEM/F-12 and mixed with 1 μl of Lipofectamine RNAiMAX (Invitrogen). After incubation for 20 min at room temperature, the NECs were added into the siRNA complexes. The NECs transfected with an AllStars negative control siRNA were used as controls. The RNAi results were evaluated by quantitative real-time PCR.

RESULTS

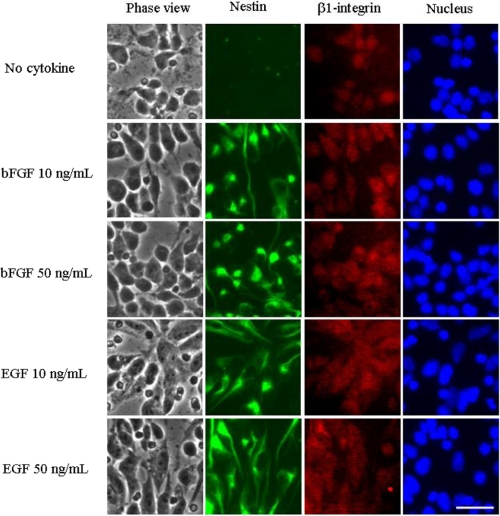

bFGF/EGF-induced Up-regulation of β1-Integrin in NECs

The NEC preparation consists mostly of NSCs capable of differentiating into mature astrocytes and neurons in vitro (36). To confirm that our primary NECs represent a valid model of NSCs, we examined the expression of nestin and β1-integrin, NSC marker proteins, in NECs cultured in the presence or absence of 10 and 50 ng/ml bFGF or EGF. As shown in Fig. 1, both nestin and β1-integrin were expressed in the majority of NECs (>95%) after culture with bFGF or EGF for 4 days. On the other hand, nestin staining was significantly less intense, and β1-integrin staining was slightly decreased after culture in the absence of bFGF and EGF for 4 days. Furthermore, we confirmed by RT-PCR that the stem cell marker Sox-2 (SRY (sex-determining region Y)-box 2) was also expressed in the NECs after culture in the presence of bFGF and EGF (data not shown). Those results clearly indicate that NECs, as well as NSCs, express NSC marker proteins.

FIGURE 1.

Expression of β1-integrin and nestin in mouse NECs. NECs were cultured in the presence or absence of 10 and 50 ng/ml bFGF or EGF for 4 days and immunostained with anti-nestin antibody (green) and anti-β1-integrin antibody (red). Nuclei were stained with Hoechst 33258 (blue). Scale bar, 50 μm.

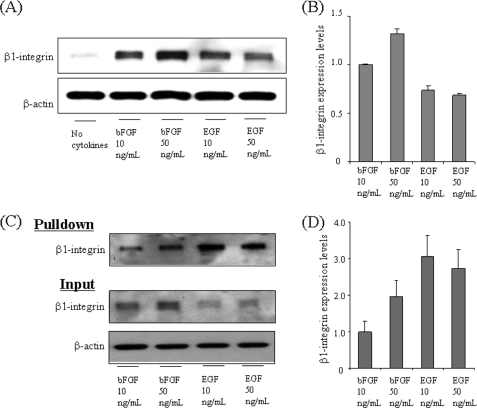

Using these NECs, we evaluated the effect of bFGF and EGF on β1-integrin expression. The total β1-integrin expression levels were significantly increased in bFGF- or EGF-stimulated NECs but less so in the absence of growth factors (Fig. 2A). As shown in Fig. 2B, the ratios of total β1-integrin expression levels in NECs stimulated with bFGF and EGF (normalized by the value in bFGF (10 ng/ml)) were 1.32 ± 0.05 in bFGF (50 ng/ml), 0.73 ± 0.04 in EGF (10 ng/ml), and 0.69 ± 0.01 in EGF (50 ng/ml). We also confirmed by RT-PCR that the mRNA expression levels of β1-integrin were equal to the expression levels of total β1-integrin protein (data not shown). We then quantified the cell surface β1-integrin expression levels in NECs. As shown in Fig. 2C, β1-integrin up-regulated by the growth factors was localized on the cell surface, especially in NECs treated with EGF. The ratios of cell surface β1-integrin expression levels in NECs stimulated with bFGF and EGF (normalized by the value in bFGF (10 ng/ml)) were 1.95 ± 0.45 in bFGF (50 ng/ml), 3.06 ± 0.58 in EGF (10 ng/ml), and 2.73 ± 0.53 in EGF (50 ng/ml) (Fig. 2D). The cell surface β1-integrin levels were drastically increased by EGF but not by bFGF (Fig. 2, B and D). As compared with a low concentration of bFGF (10 ng/ml), a high concentration of bFGF (50 ng/ml) induced an increase of the total and cell surface β1-integrin levels (1.32 ± 0.05-fold and 1.95 ± 0.45-fold, respectively). However, as compared with a low concentration of EGF (10 ng/ml), a high concentration of EGF induced a slight decrease of the total and cell surface expressions (0.94 ± 0.08-fold and 0.89 ± 0.28-fold, respectively). Those data present the first evidence to demonstrate growth factor-induced up-regulation of β1-integrin in NECs.

FIGURE 2.

bFGF- and EGF-induced up-regulation of β1-integrin in NECs. A, total cell lysates from NECs cultured in the presence or absence of 10 and 50 ng/ml of bFGF or EGF for 4 days were analyzed by Western blot with the anti-β1-integrin antibody and anti-β-actin antibody. β-Actin was detected as a loading control. B, the intensities of β1-integrin bands in A were quantified by Image J software (n = 3). C, to confirm the cell surface localization of β1-integrin, NECs cultured in the presence of 10 and 50 ng/ml bFGF or EGF for 4 days were biotinylated by treating the cells with sulfo-NHS-LC-biotin. After lysis, biotinylated cell surface proteins were pulled down with streptavidin-conjugated agarose. The cell lysates (Input) and pull-down were analyzed by Western blot. D, the intensities of β1-integrin bands in (C, Pulldown) were quantified by Image J software (n = 3).

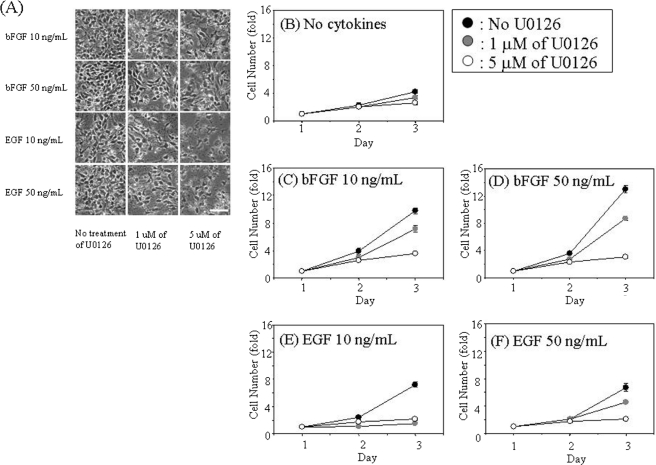

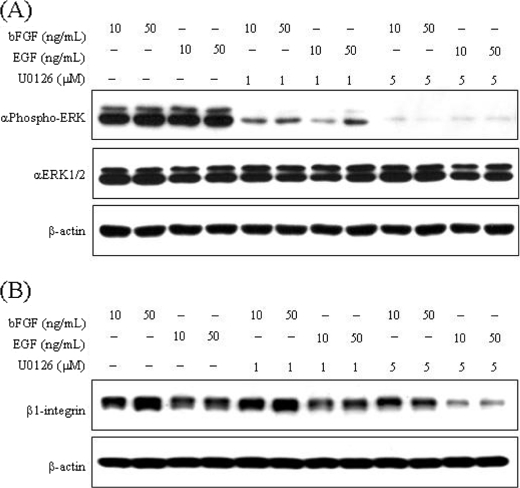

Involvement of the MAPK Pathway in bFGF/EGF-induced β1-Integrin Up-regulation in NECs

It is well known that bFGF and EGF induce activation of the MAPK-signaling pathway in NSCs. To elucidate the molecular mechanisms underlying the bFGF- and EGF-induced β1-integrin up-regulation, we evaluated the involvement of the MAPK pathway by treating NECs with U0126, an inhibitor of MEK (Fig. 3). Proliferation of NECs induced by bFGF and EGF was dose-dependently inhibited by U0126, especially in NECs cultured in the presence of EGF (Fig. 3, C–F). As shown in Fig. 4A, the phosphorylation of ERK (MAPK) induced by bFGF or EGF was drastically inhibited by U0126 in a dose-dependent manner. The inhibition was strong, as observed in NECs stimulated with 10 ng/ml EGF as compared with conditions in which the inhibition was achieved with other growth factors. Thus, U0126 inhibited the MAPK pathway in NECs as we had expected. Remarkably, as shown in Fig. 4B, β1-integrin up-regulation induced by bFGF or EGF was also inhibited by U0126; the inhibition was stronger in NECs stimulated with EGF as compared with those stimulated with bFGF. This result indicates that bFGF and EGF induce up-regulation of β1-integrin through the MAPK pathway.

FIGURE 3.

Effects of the MAPK inhibitor, U0126, on NEC proliferation through bFGF or EGF. A, phase views of NECs cultured in the presence of 10 and 50 ng/ml bFGF or EGF and treated with 1 and 5 μm U0126 or DMSO (control) for 3 days. Shown are the effects of the MAPK inhibitor U0126 on proliferation of NECs. NECs treated with 1 μm (gray circle), 5 μm (closed circle), or without (open circles) U0126 were cultured in N2-DMEM/F-12 without cytokines (B), with 10 ng/ml (C) and 50 ng/ml (D) bFGF, or with 10 ng/ml (E) and 50 ng/ml (F) EGF for 3 days (n = 3). The NEC numbers were measured by a highly sensitive and reproducible method, the WST-8 assay. The spectrophotometric absorbance of WST-8-formazan produced by cellular dehydrogenase activity, which is highly correlated with the number of living cells, was measured at a wavelength of 450 nm (reference, 650 nm).

FIGURE 4.

Effects of the MAPK inhibitor, U0126, on ERK activation and β1-integrin expression mediated by bFGF or EGF. A, NECs were cultured in the presence of 10 and 50 ng/ml bFGF or EGF and treated with 1 and 5 μm U0126 or DMSO (control) for 20 min prior to harvest, and then the total cell lysates were analyzed by Western blot with anti-phosphorylated ERK antibody, anti-ERK1/2 antibody, and anti-β-actin antibody. B, NECs were cultured in the presence of 10 and 50 ng/ml bFGF or EGF and treated with 1 and 5 mm of U0126 or DMSO (control) for 3 days prior to harvest, and then the total cell lysates were analyzed by Western blot with the anti-β1-integrin antibody and anti-β-actin antibody.

Correlation of bFGF/EGF-induced β1-Integrin Up-regulation and Proliferation in NECs

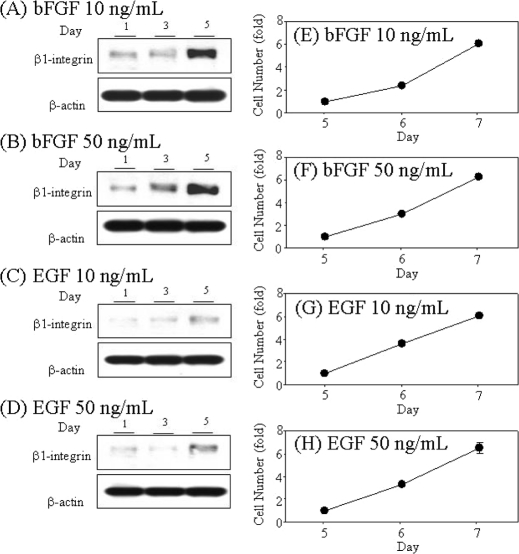

Next, we analyzed the time course of β1-integrin up-regulation induced by bFGF and EGF. As shown in Fig. 5, A and B, the total β1-integrin levels were increased in NECs cultured in the presence of bFGF in a time-dependent manner. The time-dependent gradual increase of the total β1-integrin levels was observed in NECs cultured in the presence of EGF (Fig. 5, C and D). Interestingly, the rate of bFGF- and EGF-induced proliferation was almost equal after long term culture (Fig. 5, E–H). Those results suggest the possibility that the effects of bFGF and EGF on NSC cell fates are mediated by β1-integrin.

FIGURE 5.

Involvement of responsiveness to bFGF or EGF, β1-integrin expression, and proliferation in NEC after long term culture. NECs were cultured in the presence of 10 ng/ml (A) and 50 ng/ml (B) bFGF or 10 ng/ml (C) and 50 ng/ml (D) EGF for 1, 3, and 5 days, and then the total cell lysates were blotted with the anti-β1-integrin antibody and anti-β-actin. Proliferations were analyzed after culture in the presence of 10 ng/ml (E) and 50 ng/ml (F) bFGF or 10 ng/ml (G) and 50 ng/ml (H) EGF for 5, 6, and 7 days (n = 3). The NEC numbers were measured by the WST-8 assay.

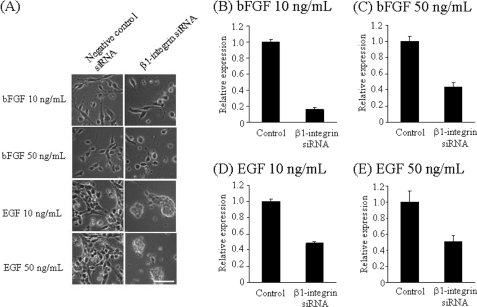

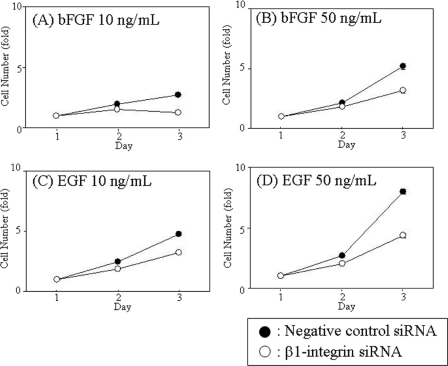

Effects of β1-Integrin Knockdown by siRNA on Proliferation of NECs

To confirm the functional roles of β1-integrin, we knocked down β1-integrin expression by transfecting NECs with β1-integrin siRNA in the presence of bFGF or EGF. As shown in Fig. 6A, the shape of bFGF-treated and β1-integrin siRNA-transfected NEC was slightly changed; it became round at 48 h after transfection. The morphological change was more significant in EGF-treated and β1-integrin siRNA-transfected NECs (Fig. 6A). Those changes can probably be attributed to the inhibition of NEC adhesion to fibronectin-coated dishes through β1-integrin.

FIGURE 6.

β1-Integrin gene knockdown by siRNA in NECs. A, phase views of NECs cultured in the presence of 10 and 50 ng/ml bFGF or EGF and transfected with 10 nm siRNA against β1-integrin or negative control siRNA at 48 h post-transfection using lipofection. Quantitative PCR analysis of β1-integrin mRNA levels in NECs after culture in the presence of 10 ng/ml (B) and 50 ng/ml (C) bFGF or 10 ng/ml (D) and 50 ng/ml (E) EGF and transfection with 10 nm siRNA against β1-integrin and negative control at 48 h post-transfection (n = 3). Scale bar, 100 μm.

Knockdown of β1-integrin in these cells was confirmed by quantitative PCR. The expression levels of β1-integrin mRNA were reduced to 16% in NECs treated with bFGF (10 ng/ml), 44% in NECs treated with bFGF (50 ng/ml), 49% in NECs treated with EGF (10 ng/ml), and 51% in NECs treated with EGF (50 ng/ml) by siRNA (Fig. 6, B–E). We then analyzed the proliferative abilities of these NECs. As shown in Fig. 7, the proliferation rates at 72 h post-transfection were also inhibited: 55% in NECs cultured in the presence of bFGF (10 ng/ml), 39% in NECs cultured in the presence of bFGF (50 ng/ml), 32% in NECs cultured in the presence of EGF (10 ng/ml), and 46% in NECs cultured in the presence of EGF (50 ng/ml). Therefore, we conclude that β1-integrin up-regulated by bFGF and EGF is involved in bFGF- and EGF-induced proliferation of NECs at least to a significant extent.

FIGURE 7.

Effects of β1-integrin knockdown by siRNA on proliferation of NECs. NECs transfected with β1-integrin siRNA (open circle) or negative control siRNA (closed circle) were cultured in N2-DMEM/F-12 with 10 ng/ml (A) and 50 ng/ml (B) bFGF or with 10 ng/ml (C) and 50 ng/ml (D) EGF for 3 days (n = 3). The NEC numbers were measured by the WST-8 assay.

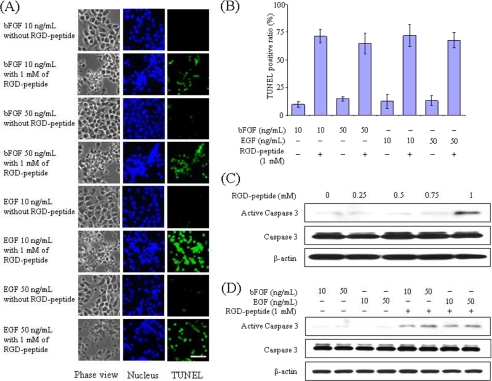

Involvement of β1-Integrin in NEC Survival

To further elucidate the functional roles of β1-integrins, we treated NECs with RGD peptide. RGD peptide is a small peptide with an Arg-Gly-Asp (RGD) motif that binds to integrin, which has been used as an antagonist to inhibit integrin functions (43–45). As shown in Fig. 8, A and B, NECs positive for TUNEL, an indicator of cell death, accompanied with DNA fragmentation were observed after treatment with 1 mm RGD peptide for 24 h. The percentages of TUNEL-positive cells were 71% in NECs cultured in the presence of bFGF (10 ng/ml), 65% in NECs cultured in the presence of bFGF (50 ng/ml), 72% in NECs cultured in the presence of EGF (50 ng/ml), and 68% in NECs cultured in the presence of EGF (50 ng/ml) (Fig. 8B). To confirm that the RGD peptide-mediated apoptosis is dependent on caspase-3, a critical executioner of the apoptosis or programmed cell death signaling, we analyzed the activation of caspase-3 by Western blot. As shown in Fig. 8C, active caspase-3 was detected after treatment of 1 mm of RGD peptide for 24 h. However, lower concentrations of RGD peptide did not induce caspase-3 activation in NECs. Furthermore, we confirmed the RGD peptide-mediated caspase-3 activation in NECs cultured in the presence of 10 and 50 ng/ml bFGF or EGF (Fig. 8D). Those results suggest that β1-integrin is involved not only in cellular proliferation but also in other cellular processes, such as the survival of NECs.

FIGURE 8.

Induction of apoptosis through caspase-3 by RGD peptide in NECs. A, phase view, TUNEL, and nuclear staining of NECs after treatment of 1 mm RGD peptide for 24 h. B, apoptosis ratio was quantified by counting the number of TUNEL-positive cells in A (n = 3–6). C, total cell lysates from NECs after culture in the presence of bFGF (10 ng/ml) and various concentrations of RGD peptide for 24 h were analyzed by Western blot with antibodies against caspase-3 and β-actin. D, NECs were lysed after culture in the presence of 10 and 50 ng/ml bFGF or EGF and treatment with or without 1 mm RGD peptide for 24 h, and then the total cell lysates were analyzed by Western blot with an anti-caspase-3 antibody and an anti-β-actin antibody. The RGD peptide inhibited NEC adhesion to fibronectin-coated dishes, and the NECs were easily removed by a washing procedure. Therefore, the ratio of apoptotic NECs may be much higher. Scale bar, 100 μm.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we showed that the proliferation of NECs through the MAPK pathway stimulated by bFGF or EGF was positively correlated with the total β1-integrin expression levels. The total β1-integrin expression and proliferation in NECs were increased by treatment with bFGF in a time- and dose-dependent manner. Although a long term culture condition is necessary, EGF also produced the same effect in a time- and dose-dependent manner. We also showed that EGF strongly induced β1-integrin expression on the NEC surface compared with bFGF. Those results indicate that β1-integrin up-regulation is essential for NEC proliferation through bFGF and EGF signaling. However, trafficking or internalization of β1-integrin and signaling mediated by β1-integrin in NECs cultured in the presence of bFGF or EGF would be expected to be different. Previous studies have indicated that the key differences between bFGF and EGF pathways are their responsiveness, which is a function of FRS2 (fibroblast growth factor receptor substrate 2) and the concentration of EGF receptor on the plasma membrane (24, 25). The bFGF-responsive NSCs are present as early as E8.5, but EGF-responsive NSCs emerge later in development (E11–E14) (46, 47). The NSCs from the mouse E14 striatum initially respond to bFGF only and then acquire EGF responsiveness later during in vitro development (48). The EGF-responsive NSCs at E14.5 have a relatively long cell cycle time as compared with FGF-responsive NSCs (29). In the bFGF-signaling pathway, more Grb2-SOS complex is recruited to the plasma membrane via phosphorylated FRS2 than those bound to receptors in the EGF pathway. On the other hand, a high EGF-receptor concentration shows prolonged phosphorylation of ERK1 or Elk, but this effect is not changed by increases of the bFGF receptor (24, 25). Furthermore, integrins share many common elements downstream of the growth factors, and they engage in a cross-talk with each other (28). In particular, three-dimensionally based cell culture conditions induce enhancement of the EGF receptor-β1-integrin interaction in breast cancer cells (49). Taken together, the difference in total β1-integrin expression levels in NECs stimulated by bFGF and EGF is thought to depend on the function of FRS2, expression levels of each growth factor receptor, coordination of the growth factor receptor and β1-integrin, and cell culture conditions (12, 27, 28, 49).

β1-Integrins are known to give rise to constitutive endocytosis and recycling (50). β1-Integrin is distributed in membrane microdomains (lipid rafts), and the microdomains contribute to integrin-fibronectin interaction-dependent adhesion and activation of the MAPK pathway in NECs (35). Furthermore, caveolin-1-dependent β1-integrin endocytosis plays a critical role in regulation of fibronectin matrix turnover (51). In addition, gangliosides and β1-integrin are required for maintenance of caveolae and plasma membrane domains (52). The functions of bFGF or EGF receptor are known to be modulated by glycosphingolipids in membrane microdomain (53, 54). Integrin-growth factor receptor cross-talk is strongly influenced by the glycosylation state in the ganglioside-enriched microdomains (55–58). Recently, it has been shown that a glycosphingolipid, lactosylceramide, regulates β1-integrin clustering and endocytosis (59). Integrin-associated Lyn kinase in lipid rafts also plays a critical role in neural cell survival (60). Those examples indicate that the functions of β1-integrin are dependent on its endocytosis, especially in bFGF-induced NECs. Our results suggest that the ratio of cell surface/total β1-integrin expression is decreased by bFGF but increased by EGF. Furthermore, we have found that the increases of total β1-integrin induced by bFGF were earlier than those induced by EGF after initiating the culture (Fig. 5, A–D). It was previously reported that endocytosis of β1-integrins is an early event in cellular migration promoted by such cell adhesion molecules as L1 (61). Therefore, β1-integrin endocytosis induced by bFGF signaling has been suggested to play an essential role in migration of NECs in the early term after initiating the culture.

Integrins are N-glycan-carrying proteins. α5β1-integrin contains 14 and 12 putative N-glycosylation sites on the α5 and β1 subunits, respectively (62, 63). N-Glycosylation of the I-like domain of β1-integrin is essential to both the heterodimer formation and biological function of the subunits (62). N-Glycans are required for the activation but not for the localization of gp130 in NECs (64). Sialylation on the non-reducing terminus of N-glycans of α5β1-integrin plays an important role in cell adhesion (65). Alterations of N-glycans on integrins could also regulate their cis interactions with membrane-associated proteins, including the epidermal growth factor receptor (66, 67). Together, N-glycosylation of β1-integrin modulates its functions and may regulate cell surface expressions and localizations by changing its intracellular trafficking in NSCs.

In this study, the NEC adhesions to fibronectin-coated dishes after culture in the presence of EGF were strongly inhibited at 48 h post-transfection of β1-integrin siRNA, as compared with transfection with the control siRNA. On the other hand, NEC adhesion after culture in the presence of bFGF and β1-integrin siRNA was only slightly inhibited, and the NECs were changed to be round shapes (Fig. 6A). Those results suggest that β1-integrin must be a major component for the adhesion of NECs to fibronectin-coated dishes in EGF-stimulated NECs. We cannot rule out the possibility that other adherent components, such as NCAM, L1, and cadherin, may also play a role in this process. Additionally, β1-integrin endocytosis-mediated signaling might maintain adhesion in bFGF-stimulated NECs. Furthermore, the proliferative abilities of NECs induced by bFGF or EGF were inhibited at 72 h post-transfection of β1-integrin siRNA (Fig. 7). β1-Integrin inhibition may lead to a decrease in Shc phosphorylation resulting in failure to recruit Grb2 and, consequently, to activate the Ras-MAPK pathway (68).

Another interesting aspect of our study concerns the RGD peptide-induced apoptosis of NECs through caspase-3 activation. Although 50 ng/ml bFGF or EGF slightly inhibited apoptosis, no difference in the apoptosis ratio was observed in bFGF- and EGF-stimulated NECs (Fig. 8, A–D). The results indicate that the RGD peptide- induced apoptosis through caspase-3 activation in NEC is not dependent on differences in the expression levels of β1-integrin or in localization through bFGF or EGF signalings.

In conclusion, our study demonstrates that the bFGF or EGF differentially induces up-regulation of β1-integrin and that this effect is correlated with NEC proliferation. Our study also illustrates that the bFGF- or EGF-induced β1-integrin expression/localization mechanisms in NECs are different. Further studies will be required to thoroughly elucidate the functional roles and expression/localization mechanisms of β1-integrin through different growth factor signalings in NSCs.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants NS11853 and NS26994. This work was also supported by a grant from the Children's Medical Research Foundation (Chicago, IL) (to R. K. Y.) and a start-up fund from the Medical College of Georgia (to M. Y.).

- NSC

- neural stem/progenitor cell

- bFGF

- basic fibroblast growth factor

- DMEM/F-12

- Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium/F-12 medium

- En

- embryonic day n

- ERK

- extracellular signal-regulated kinase

- MAPK

- mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase

- NEC

- neuroepithelial cell

- siRNA

- small interfering RNA

- TUNEL

- terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP nick-end labeling

- WST-8

- 2-(2-methoxy-4-nitrophenyl)-3-(4-nitrophenyl)-5-(2,4-disulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium

- MEK

- mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase kinase

- EGF

- epidermal growth factor

- PBS

- phosphate-buffered saline

- RNAi

- RNA interference.

REFERENCES

- 1.McKay R. (1997) Science 276, 66–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Temple S., Alvarez-Buylla A. (1999) Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 9, 135–141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gage F. H. (2000) Science 287, 1433–1438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yanagisawa M., Yu R. K. (2007) Glycobiology 17, 57R–74R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lindvall O., Kokaia Z. (2010) J. Clin. Invest. 120, 29–40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jeong S. W., Chu K., Jung K. H., Kim S. U., Kim M., Roh J. K. (2003) Stroke 34, 2258–2263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Björklund A., Lindvall O. (2000) Nat. Neurosci. 3, 537–544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fukuda S., Taga T. (2005) Anat. Sci. Int. 80, 12– 18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kohyama J., Kojima T., Takatsuka E., Yamashita T., Namiki J., Hsieh J., Gage F. H., Namihira M., Okano H., Sawamoto K., Nakashima K. (2008) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 18012–18017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hsieh J., Gage F. H. (2004) Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 14, 461–469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hsieh J., Nakashima K., Kuwabara T., Mejia E., Gage F. H. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 16659–16664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Campos L. S., Decker L., Taylor V., Skarnes W. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 5300–5309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li L., Xie T. (2005) Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 21, 605–631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang J., Li L. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 9499–9503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Whittemore S. R., Morassutti D. J., Walters W. M., Liu R. H., Magnuson D. S. (1999) Exp. Cell Res. 252, 75–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Loulier K., Lathia J. D., Marthiens V., Relucio J., Mughal M. R., Tang S. C., Coksaygan T., Hall P. E., Chigurupati S., Patton B., Colognato H., Rao M. S., Mattson M. P., Haydar T. F., Ffrench-Constant C. (2009) PLoS Biol. 7, e1000176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ellis S. J., Tanentzapf G. (2010) Cell Tissue Res. 339, 121–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Campos L. S. (2005) BioEssays 27, 698–707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Campos L. S., Leone D. P., Relvas J. B., Brakebusch C., Fässler R., Suter U., ffrench-Constant C. (2004) Development 131, 3433–3444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xiao Z., Kong Y., Yang S., Li M., Wen J., Li L. (2007) Cell Res. 17, 73–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Learish R. D., Bruss M. D., Haak-Frendscho M. (2000) Brain Res. Dev. Brain Res. 122, 97–109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yanagisawa M., Nakamura K., Taga T. (2005) J. Biochem. 138, 285–291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kalyani A. J., Mujtaba T., Rao M. S. (1999) J. Neurobiol. 38, 207–224 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schlessinger J. (2004) Science 306, 1506–1507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yamada S., Taketomi T., Yoshimura A. (2004) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 314, 1113–1120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liao H., Huang W., Schachner M., Guan Y., Guo J., Yan J., Qin J., Bai X., Zhang L. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 27927–27936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yamada K. M., Even-Ram S. (2002) Nat. Cell Biol. 4, E75–E76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schwartz M. A., Ginsberg M. H. (2002) Nat. Cell Biol. 4, E65–E68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Streuli C. H. (2009) J. Cell Sci. 122, 171–177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Andressen C., Adrian S., Fässler R., Arnhold S., Addicks K. (2005) Eur. J. Cell Biol. 84, 973–982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jacques T. S., Relvas J. B., Nishimura S., Pytela R., Edwards G. M., Streuli C. H., ffrench-Constant C. (1998) Development 125, 3167–3177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hall P. E., Lathia J. D., Miller N. G., Caldwell M. A., ffrench-Constant C. (2006) Stem Cells 24, 2078–2084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nagato M., Heike T., Kato T., Yamanaka Y., Yoshimoto M., Shimazaki T., Okano H., Nakahata T. (2005) J. Neurosci. Res. 80, 456–466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Leone D. P., Relvas J. B., Campos L. S., Hemmi S., Brakebusch C., Fässler R., Ffrench-Constant C., Suter U. (2005) J. Cell Sci. 118, 2589–2599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yanagisawa M., Nakamura K., Taga T. (2004) Genes Cells 9, 801–809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fukuda S., Abematsu M., Mori H., Yanagisawa M., Kagawa T., Nakashima K., Yoshimura A., Taga T. (2007) Mol. Cell Biol. 27, 4931–4937 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nakashima K., Wiese S., Yanagisawa M., Arakawa H., Kimura N., Hisatsune T., Yoshida K., Kishimoto T., Sendtner M., Taga T. (1999) J. Neurosci. 19, 5429–5434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yanagisawa M., Taga T., Nakamura K., Ariga T., Yu R. K. (2005) J. Neurochem. 95, 1311–1320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Suzuki Y., Takeda Y., Ikuta T. (2008) Anal. Biochem. 378, 218–220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yu R. K., Yanagisawa M. (2007) J. Neurochem. 103, Suppl. 1,39– 46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dasgupta S., Silva J., Wang G., Yu R. K. (2009) J. Neurosci. Res. 87, 3591–3599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhao M., Yang H., Jiang X., Zhou W., Zhu B., Zeng Y., Yao K., Ren C. (2008) Mol. Biotechnol. 40, 19–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Watson P. M., Humphries M. J., Relton J., Rothwell N. J., Verkhratsky A., Gibson R. M. (2007) Mol. Cell Neurosci. 34, 147–154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Suri S. S., Rakotondradany F., Myles A. J., Fenniri H., Singh B. (2009) Biomaterials 30, 3084–3090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Buckley C. D., Pilling D., Henriquez N. V., Parsonage G., Threlfall K., Scheel-Toellner D., Simmons D. L., Akbar A. N., Lord J. M., Salmon M. (1999) Nature 397, 534–539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tropepe V., Sibilia M., Ciruna B. G., Rossant J., Wagner E. F., van der Kooy D. (1999) Dev. Biol. 208, 166–188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Martens D. J., Tropepe V., van Der Kooy D. (2000) J. Neurosci. 20, 1085–1095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ciccolini F., Svendsen C. N. (1998) J. Neurosci. 18, 7869–7880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang F., Weaver V. M., Petersen O. W., Larabell C. A., Dedhar S., Briand P., Lupu R., Bissell M. J. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 14821–14826 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.del Pozo M. A., Alderson N. B., Kiosses W. B., Chiang H. H., Anderson R. G., Schwartz M. A. (2004) Science 303, 839–842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shi F., Sottile J. (2008) J. Cell Sci. 121, 2360–2371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Singh R. D., Marks D. L., Holicky E. L., Wheatley C. L., Kaptzan T., Sato S. B., Kobayashi T., Ling K., Pagano R. E. (2010) Traffic 11, 348–360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yates A. J., Rampersaud A. (1998) Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 845, 57–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hakomori S., Igarashi Y. (1995) J. Biochem. 118, 1091–1103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hakomori S. I. (2008) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1780, 325–346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kazui A., Ono M., Handa K., Hakomori S. (2000) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 273, 159–163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Toledo M. S., Suzuki E., Handa K., Hakomori S. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 16227–16234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Murozuka Y., Watanabe N., Hatanaka K., Hakomori S. I. (2007) Glycoconj. J. 24, 551–563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sharma D. K., Brown J. C., Cheng Z., Holicky E. L., Marks D. L., Pagano R. E. (2005) Cancer Res. 65, 8233–8241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chudakova D. A., Zeidan Y. H., Wheeler B. W., Yu J., Novgorodov S. A., Kindy M. S., Hannun Y. A., Gudz T. I. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 28806–28816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Panicker A. K., Buhusi M., Erickson A., Maness P. F. (2006) Exp. Cell Res. 312, 299–307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Isaji T., Sato Y., Fukuda T., Gu J. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 12207–12216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gu J., Isaji T., Sato Y., Kariya Y., Fukuda T. (2009) Biol. Pharm. Bull. 32, 780–785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yanagisawa M., Yu R. K. (2009) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 386, 101–104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhuo Y., Chammas R., Bellis S. L. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 22177–22185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gu J., Zhao Y., Isaji T., Shibukawa Y., Ihara H., Takahashi M., Ikeda Y., Miyoshi E., Honke K., Taniguchi N. (2004) Glycobiology 14, 177–186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Shigeta M., Shibukawa Y., Ihara H., Miyoshi E., Taniguchi N., Gu J. (2006) Glycobiology 16, 564–571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Faraldo M. M., Deugnier M. A., Thiery J. P., Glukhova M. A. (2001) EMBO Rep. 2, 431–437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]