Abstract

Several important signaling pathways require NAD as substrate, thereby leading to significant consumption of the molecule. Because NAD is also an essential redox carrier, its continuous resynthesis is vital. In higher eukaryotes, maintenance of compartmentalized NAD pools is critical, but so far rather little is known about the regulation and subcellular distribution of NAD biosynthetic enzymes. The key step in NAD biosynthesis is the formation of the dinucleotide by nicotinamide/nicotinic acid mononucleotide adenylyltransferases (NMNATs). The three human isoforms were localized to the nucleus, the Golgi complex, and mitochondria. Here, we show that their genes contain unique exons that encode isoform-specific domains to mediate subcellular targeting and post-translational modifications. These domains are dispensable for catalytic activity, consistent with their absence from NMNATs of lower organisms. We further demonstrate that the Golgi-associated NMNAT is palmitoylated at two adjacent cysteine residues of its isoform-specific domain and thereby anchored at the cytoplasmic surface, a potential mechanism to regulate the cytosolic NAD pool. Insertion of unique domains thus provides a yet unrecognized enzyme targeting mode, which has also been adapted to modulate subcellular NAD supply.

Keywords: Energy Metabolism, Enzyme Structure, Mitochondria, NAD, NADH, Nicotinamide, Nucleoside Nucleotide Metabolism, Post-translational Modification, Protein Targeting

Introduction

The metabolism of NAD has emerged as a complex network of reactions with immediate impact on fundamental biological processes (1–3). Even though the vital importance of this molecule has long been recognized, the molecular mechanisms of its synthesis and their regulation have moved into focus only in recent years. Although the bioenergetic role of NAD in reversible electron transfer reactions has been known for decades, only now has it become clear that this nucleotide is also a versatile component of signal transduction pathways, in which it is permanently degraded (1–3). For example, PARP1 (poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1) mediates DNA repair and cell stress responses (4–6); NAD-dependent protein deacetylases, sirtuins, are involved in metabolic and life span regulation (7–10); and ADP-ribosyl cyclases use NAD to generate second messengers mediating calcium signaling (2, 11, 12). Because of the ongoing degradation in these reactions, continuous resynthesis of NAD is vital.

Although the molecular details of NAD synthesis are still far from being understood, the central role of nicotinamide mononucleotide adenylyltransferases (NMNATs)2 has been established (13–16). These enzymes catalyze the reaction at which all NAD biosynthetic pathways merge, the formation of the dinucleotide from NMN (or the nicotinic acid derivative, nicotinic acid mononucleotide) and ATP. Most NMNATs are homo-oligomers composed of ∼30-kDa subunits. In mammals, there are three compartment-specific isoforms that likely maintain independent subcellular NAD pools.

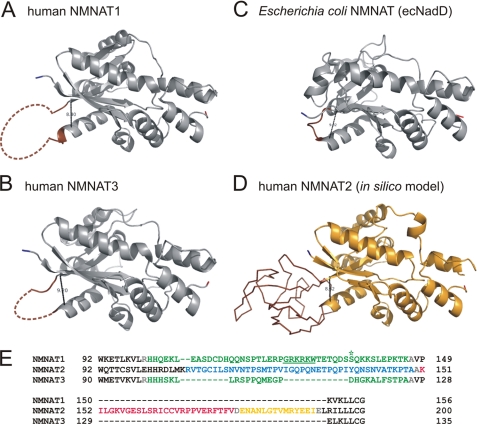

Three-dimensional structures of several NMNATs, including human isoforms 1 and 3, have been established (reviewed in Refs. 13 and 16). Interestingly, the subunit structures of both human NMNAT1 and NMNAT3 contain a region that could not be resolved by x-ray crystallography. Comparing the structures of bacterial and mammalian NMNATs, the overall fold has been highly conserved throughout evolution (13, 14, 16). However, bacterial NMNATs lack the stretch of amino acids that would correspond to the unresolved regions in human NMNAT1 and NMNAT3 (see Fig. 1, A–C).

FIGURE 1.

Structures of human and E. coli NMNATs. A–C, single subunits of human NMNAT1 (Protein Data Bank code 1kku) (A), human NMNAT3 (code 1nur) (B), and E. coli NMNAT (ecNadD; code 1k4k) (C) are shown. Bacterial NMNATs, e.g. ecNadD, exhibit a short loop (brown) that precedes the first β-strand of the second mononucleotide-binding motif βαβαβ. In crystal structures of NMNAT1 and NMNAT3, the corresponding regions could not be resolved and are represented as dashed lines. In this study, these regions are referred to as ISTIDs. The distances between the Cα atoms of the loop-flanking amino acids Met106 and Lys150 of NMNAT1, Leu104 and Glu129 of NMNAT3, and Gln96 and Leu102 of ecNadD are 8.40, 9.20, and 9.02 Å, respectively. D, a structural model of human NMNAT2 was generated using 3Djigsaw. Amino acids that represent ISTID2 of NMNAT2 (Lys107–Leu192) are displayed as a backbone and are shown in brown. The predicted distance between the Cα atoms of the flanking residues Met106 and Arg193 is 8.32 Å. E, ISTIDs in human NMNATs are encoded by distinct exonic regions. Exons 3 (green) of the NMNAT1 (Ensembl ENST00000377205) and NMNAT3 (ENST00000296202) transcripts encode His101–Lys146 and His99–Ala125, respectively. These stretches cover both ISTIDs of the enzymes and six additional N-terminal residues (NMNAT1, HHQEKL; and NMNAT3, HHHSKL). Both the nuclear localization signal of NMNAT1 (underlined) and Ser136 (asterisk), which is subject to protein kinase C-dependent phosphorylation, are present within ISTID1. For NMNAT2 (Ensembl ENST000002877113), the three successive exons 5 (Arg108–Ala149; blue), 6 (Lys151–Val176; red), and 7 (Asp178–Ile190; yellow) encode ISTID2. Here, Ala150, Asp177, and Glu191 (gray) derive from neighboring exons.

Mammalian NMNATs appear to fulfill specific regulatory roles in addition to their catalytic function. Human NMNAT1 and NMNAT3 were proposed to act as molecular chaperones (16, 17). Moreover, nuclear NMNAT1 activates PARP1 and thereby facilitates a caspase-independent pathway of apoptosis. This interaction is strongly reduced by phosphorylation of NMNAT1 at Ser136 (indicated in Fig. 1E), which is part of the unresolved region mentioned above (18). This region also contains a predicted nuclear localization signal that might mediate the targeting of NMNAT1 (19). Elevated NMNAT1 expression has been identified as a consequence of the genetic alteration in slowed Wallerian degeneration (WldS) mice (20, 21). Although NMNAT activity is increased, the cellular NAD concentration remains unchanged (21, 22). Therefore, the delay in axon degeneration following nerve transection in WldS mice may, at least in part, result from non-catalytic functions of NMNAT1, although the exact mechanism is still controversial (20, 23–26).

Human NMNAT2 was localized to the Golgi complex, whereas NMNAT3 is a mitochondrial protein (27, 28). Except for the characterization of their catalytic properties (27, 29), the roles of these isoforms have been poorly investigated. In particular, the molecular mechanisms of their subcellular targeting have remained unknown. The Golgi localization of NMNAT2 is puzzling because little is known about NAD-dependent processes in this compartment. Moreover, the precise localization, in particular, whether NMNAT2 resides within the lumen of this organelle, has not been established so far.

Because in mammals mitochondrial NAD is not exchangeable with the cytosol, NMNAT3 presumably participates in the maintenance of the organellar nucleotide pool. Besides the NAD requirement for biological oxidation, in mitochondria, a number of important NAD-consuming regulatory reactions take place, including ADP-ribosylation of glutamate dehydrogenase (10, 30) and NAD-dependent deacetylation of both acetyl-CoA synthetase (31) and carbamoyl-phosphate synthetase (32).

This study was based on the intriguing presence of the unresolved region in human NMNAT1 and its potential role in signaling and subcellular targeting. We hypothesized that additional functional domains could have been acquired by NMNATs of higher eukaryotes to mediate non-catalytic functions such as subcellular localization and regulatory interactions. Our analyses indeed demonstrate that all three human NMNAT genes contain unique exons encoding isoform-specific sequence insertions. These domains have evolved to mediate subcellular targeting, post-translational modifications, and regulatory functions, and we therefore designate them as isoform-specific targeting and interaction domains (ISTIDs).

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Antibodies and Reagents

Antibodies against the calcium-independent mannose 6-phosphate receptor (Abcam), GM130 (Golgi matrix protein of 130 kDa; BD Biosciences), FLAG tag (Sigma), and green fluorescent protein (JL-8, Invitrogen), as well as Alexa Fluor (Invitrogen)-conjugated and horseradish peroxidase (Thermo Scientific)-conjugated secondary antibodies, were applied according to the manufacturers' recommendations. Mouse anti-ERGIC53 antibody was a kind gift of Dr. Jaakko Saraste (University of Bergen). Brefeldin A (BFA), nocodazole, 2-bromopalmitate (2-BP), proteinase K, firefly luciferase, and luciferin were purchased from Sigma. 4′,6-Diamidino-2-phenylindole and MitoTracker CMXRos were purchased from Invitrogen. All restriction enzymes were from Takara. [U-14C]palmitic acid was obtained from PerkinElmer Life Sciences.

Cloning and in Vitro Mutagenesis

Eukaryotic expression vectors encoding the wild-type NMNAT cDNAs were described previously (27). The NMNAT2 open reading frame was additionally cloned into pCMV/Myc/cyto/eGFP. Mutations in NMNAT cDNAs were generated by PCR-based in vitro mutagenesis. The pFLAG-CMV4-ISTID2-eGFP plasmid was generated by cloning the enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP) open reading frame into pFLAG-CMV4, followed by insertion of the sequence coding for the peptide Val109–Leu192 of human NMNAT2.

Cell Culture

HeLa S3 cells were grown in Ham's F-12 medium (Lonza) supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (Biochrom) and 100 units of penicillin/100 μg of streptomycin (Lonza). Transient transfections were performed using Effectene (Qiagen). For pharmacological treatments, cells were incubated with 5 μg/ml BFA for 30 min or with 10 μm nocodazole for 180 min. 2-BP was added to cells at the time of transfection to a final concentration of 25 μm. After 18 h of incubation, cells were harvested or fixed for immunocytochemistry.

NMNAT Activity Assay

The assay was based on luciferase activity coupled to ATP synthesis in the reverse reaction of NMNAT. The increase in luminescence was recorded as relative light units. Cells were harvested 48 h after transfection by scraping in lysis buffer (25 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 150 mm NaCl, 0.5% (v/v) Triton X-100, and 0.4 mm Pefabloc SC) and disrupted by applying 20 strokes through a 23-gauge needle. Luminescence was measured with a BMG FLUOstar Optima plate reader. Reaction mixtures (200 μl) contained HeLa S3 cell extract, reaction buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 200 mm NaCl, and 1 mm MgCl2), 3 mm inorganic pyrophosphate, 0.5 mm luciferin, and 0.2 μg of luciferase. The reaction was started by the addition of 2 mm NAD+.

Immunocytochemistry

Cells were fixed in 3.7% (v/v) formaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline, followed by methanol for 10 min at −20 °C or permeabilization with 0.5% (v/v) Triton X-100. Primary and Alexa Fluor 488- or Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated secondary antibodies were diluted in complete cell culture medium. Nuclei were stained with 1 μg/ml 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole. Mitochondria were visualized by staining with MitoTracker CMXRos. Images were taken with a DMI6000B inverse epifluorescence microscope (Leica Microsystems) equipped with a 100× oil immersion objective (numerical aperture, 1.40).

Proteinase K Digestion

Cells were resuspended in ice-cold lysis buffer (250 mm sucrose, 10 mm Hepes-KOH (pH 7.4), 150 mm NaCl, and 1 mm CaCl2) and disrupted by ultrasound. Samples were diluted 1:2 in lysis buffer supplemented with 100 μg/ml proteinase K with or without 2% (v/v) Triton X-100. For controls, only buffer or buffer containing Triton X-100 was added. After 60 min at 4 °C, digestion was stopped by the addition of 5 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride.

In Vivo Palmitoylation

Cells were preincubated with serum-free medium containing 0.1% (w/v) fatty acid-free bovine serum albumin in the presence or absence of 100 μm 2-BP for 1 h at 37 °C. Labeling was performed by incubation with 10 μCi/ml [U-14C]palmitic acid in the same medium for 1 h at 37 °C. Cells were then washed in phosphate-buffered saline and lysed in 1% (v/v) Triton X-100, 50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 150 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, and 0.4 mm Pefabloc SC. The extracts were mixed with nonreducing SDS sample buffer and separated by SDS-PAGE. The dried gel was subjected to autoradiography. In parallel, immunoblot analyses were performed to control for expression.

Protein Structure Prediction

The protein sequence of human NMNAT2 (UniProt Q9BZQ4-1) was subjected to comparative structural modeling by 3Djigsaw (33) using the structure of human NMNAT1 (Protein Data Bank code 1kku) (34) as template. Secondary structure predictions were performed using Porter (35), Sable (36), Jpred3 (37), ProfKing (38), SSpro (39), and PSIPRED (40). Additionally, the GenTHREADER method (41) from the PSIPRED server was used for fold recognition. The prediction outputs were analyzed using PyMOL (42) for molecular visualization of Protein Data Bank files and estimation of molecular distances and ClustalX (43) and Jalview (44) for displaying the secondary structure consensus.

Multiple Sequence Alignments of Vertebrate NMNATs and PAML (Phylogenetic Analysis by Maximum Likelihood) Statistical Analysis

Sequences of NMNAT orthologs from vertebrate species were retrieved from the Ensembl Database (release 53) (45) or predicted using GeneWise (46). Only completely sequenced genes with fewer than three amino acid insertions/deletions compared with the human sequence were considered. To obtain multiple DNA sequence alignments, the corresponding protein sequences were aligned using MUSCLE (47) and prepared with PAL2NAL (48) for codon alignments and to remove gaps. The underlying phylogeny was obtained using PHYLIP protml (49). Substitution rates were calculated using PAML (50) to obtain the nonsynonymous-to-synonymous substitution rate ratio (ω = dN/dS), with ω values <1, =1, and >1 indicating purifying selection, neutral evolution, and diversifying (positive) selection, respectively. For each of the three sets of orthologous genes, a two-fixed-sites model (model E) was applied (51). Protein sites were divided into two classes. The first class (0) contained all amino acid residues of the NMNATs except the ISTID amino acids, which accounted for the second class (1). Model E was compared with model C, which assumes equal evolutionary rates for all sites. The model comparisons were conducted by likelihood ratio tests, which assume that the 2Δln L is approximately χ2 distributed.

RESULTS

Human NMNATs Contain Isoform-specific Insertions within the Highly Conserved Catalytic Core Structure

Comparison of the tertiary structures of human NMNAT1 and NMNAT3 with their homolog from Escherichia coli (ecNadD) revealed that the striking structural similarity is interrupted by a variable region, which precedes β-strand 4 of the common Rossmann fold (Fig. 1, A–C). Because no crystal structure of NMNAT2 has been reported, we attempted to generate a structural model. PSIPRED secondary structure prediction and structural alignment with human NMNAT1 (Protein Data Bank code 1kku) (34) were performed to build a model using the 3Djigsaw server (Fig. 1D). The result suggests that NMNAT2 exhibits a topology that is highly similar to NMNAT1 and NMNAT3, including a region, covered by Lys107–Leu192 (Fig. 1E), that sticks out of the predicted globular structure (Fig. 1D, highlighted in brown). The distance between the flanking amino acids, Met106 and Arg193, is strikingly similar to that between the respective residues in NMNAT1 (Leu106 and Lys150) (Fig. 1A), NMNAT3 (Leu104 and Glu129) (Fig. 1B), and ecNadD (Glu96 and Leu102) (Fig. 1C). However, no structural template was found by this approach that would allow us to reliably predict the fold of this region in NMNAT2. To achieve a more accurate model for the stretch from Lys107 to Leu192, we conducted comprehensive in silico secondary structure predictions based on different comparative methods (supplemental Fig. S1). Importantly, the prediction consensus for the secondary structure elements that form the conserved catalytic fold (supplemental Fig. S1, lines 2–7) is in agreement with the established structures of NMNAT1 (Protein Data Bank code 1kku) and NMNAT3 (code 1nur) (28) (supplemental Fig. S1, line 9) and verifies the three-dimensional structural model of NMNAT2. Only threading of the NMNAT2 protein sequence onto the structure of NADPH-dependent prostaglandin E2 9-reductase (rabbit; Protein Data Bank code 1q5m) (52) resulted in an alignment, which also covered the ISTID of NMNAT2. The predicted fold based on this alignment (supplemental Fig. S1, line 8) is consistent with the comparative predictions and strengthens the consensus.

Multiple sequence alignments of NMNATs and their three-dimensional structures (Fig. 1) showed that Glu107–Lys146, Lys107–Leu192, and Leu105–Ala125 of human NMNAT1, NMNAT2, and NMNAT3, respectively, represent sequences that are highly specific for the individual isoforms. Therefore, these regions in human NMNATs may have arisen as additional insertions into the common globular structure to provide non-catalytic functions. Indeed, both the predicted nuclear localization signal of NMNAT1 (Fig. 1E, underlined) and the phosphorylation site regulating NMNAT1-PARP1 interaction (asterisk) reside here. Notably, the respective sequences are encoded by separate exons in the human NMNAT isoforms (Fig. 1E). The insertions in NMNAT1 and NMNAT3 are encoded by a single exon, whereas for NMNAT2, three respective exons were found. On the basis of their distinct functional roles (see below), we refer to these sequences as ISTIDs.

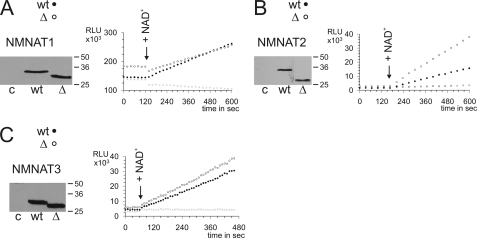

ISTIDs in Human NMNATs Are Dispensable for Catalytic Activity

Because of the high structural similarity of the overall folds and the absence of a corresponding region in bacterial NMNAT homologs, we considered that the ISTIDs in human NMNATs might be dispensable for catalytic activity. To test this assumption, we generated mutants lacking residues Glu107–Lys146 (NMNAT1_ΔISTID1), Val109–Leu192 (NMNAT2_ΔISTID2), and Leu105–Ala125 (NMNAT3_ΔISTID3) (see supplemental Fig. S2 for an illustration of all constructs used in this study). These deletions were unlikely to cause significant structural distortions in the remaining parts of the proteins. For example, structural modeling of NMNAT2_ΔISTID2 by 3Djigsaw suggested the NMNAT-specific overall fold to be unaffected by the deletion (data not shown). HeLa S3 cells were transfected with plasmids encoding the deletion mutants and whole cell extracts were subjected to a luciferase-coupled enzyme assay (Fig. 2). Overexpression of any of the constructs resulted in a strong increase in overall NMNAT activity compared with non-transfected cells. Therefore, the impact of endogenous NMNAT activities was negligible when comparing the activities of the different constructs. Remarkably, the catalytic activities of all ISTID deletion mutants were at least comparable to the corresponding wild-type activities. Thus, the ISTIDs are fully dispensable for the enzymatic function of human NMNATs. Interestingly, compared with the wild-type protein, the activity of NMNAT2_ΔISTID2 was at least doubled (Fig. 2B).

FIGURE 2.

ISTIDs of human NMNATs are dispensable for catalytic activity. The NMNAT activities of ISTID deletion mutants (Δ, ○) NMNAT1_ΔISTID1 (A), NMNAT2_ΔISTID2 (B), and NMNAT3_ΔISTID3 (C) overexpressed in HeLa S3 cells were determined and compared with those of the respective wild-type proteins (wt, ●). The use of comparable amounts of expressed protein was verified by Western blotting as shown. Extracts from non-transfected cells were used as controls in both activity measurements (×) and Western blots (c). Reactions were started by the addition of NAD+ (arrows). All experiments were performed at least twice in duplicates. Representative data sets are shown. RLU, relative light units. Note that purified recombinant human NMNATs exhibit relative catalytic activities of ∼20:1:2 (NMNAT1/NMNAT2/NMNAT3) (27).

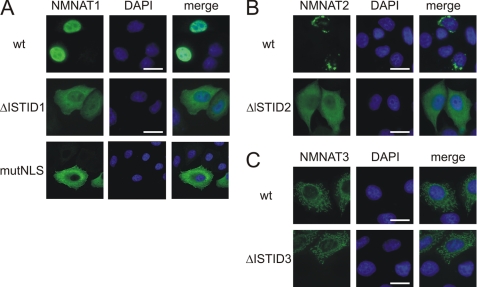

ISTIDs of NMNAT1 and NMNAT2 Mediate Subcellular Targeting

Deletion of the respective ISTID sequences dramatically changed the subcellular locations of NMNAT1 and NMNAT2 (Fig. 3, A and B). Both deletion mutants were distributed throughout the cytoplasm. The localization of NMNAT1_ΔISTID1 is in agreement with the redistribution of the NMNAT1 mouse homolog when mutated in the nuclear localization signal (53). As shown in Fig. 3A (lower panels), human NMNAT1 targeting indeed depends on the predicted nuclear localization signal (GRKRKW) because substitution of these residues with alanines also caused redistribution of the protein to the cytoplasm. Wild-type NMNAT2 predominantly localized to the cis-Golgi complex (Fig. 3B and supplemental Fig. S3). In contrast to the observations regarding NMNAT1 and NMNAT2, deletion of ISTID3 did not alter the mitochondrial localization of NMNAT3 (Fig. 3C).

FIGURE 3.

ISTIDs of human NMNAT1 and NMNAT2 mediate subcellular localization. The intracellular distribution of NMNAT ISTID deletion mutants of NMNAT1 (A), NMNAT2 (B), and NMNAT3 (C) was compared with that of the corresponding wild-type proteins (wt). The proteins were overexpressed in HeLa S3 cells, and their subcellular distribution was revealed by FLAG immunocytochemistry. For A (lower panels), Gly124–Trp129 (GRKRKW) within ISTID1 of NMNAT1 were mutated to alanine residues. Cell nuclei were visualized by 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) staining (shown in blue). Scale bars = 10 μm. mutNLS, mutant nuclear localization signal.

NMNAT2 Localizes to the cis-Golgi and Endoplasmic Reticulum (ER)-Golgi Intermediate Compartment

Immunostaining of NMNAT2 largely repeated the perinuclear Golgi ribbon structure of the cis-Golgi marker GM130. Furthermore, NMNAT2 was located in the proximity of the ER-Golgi intermediate compartment, as it co-localized with ERGIC53 (supplemental Fig. S3). NMNAT2 was far less detectable in peripheral subcompartments of the secretory pathway, such as the trans-Golgi network, as well as late or early endosomes, as revealed by co-staining of the calcium-independent mannose 6-phosphate receptor (supplemental Fig. S3) or EEA1 (early endosome antigen 1) (data not shown).

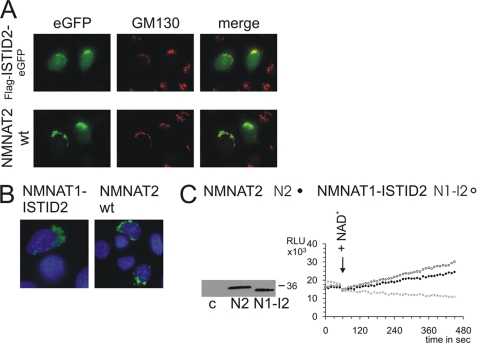

NMNAT Attachment to the Golgi by ISTID2 Minimizes Catalytic Activity

To verify a role for ISTID2 in targeting to the Golgi complex, we analyzed a construct consisting of an N-terminal FLAG tag followed by Val109–Leu192 (ISTID2) and C-terminal eGFP, termed FLAG-ISTID2-eGFP (cf. supplemental Fig. S2). This fusion protein indeed tended to localize to the Golgi complex (Fig. 4A), whereas part of the protein was also detected in the nucleus, as observed for eGFP alone. Remarkably, replacement of ISTID1 with ISTID2 in NMNAT1 led to a specific Golgi localization of the protein (NMNAT1-ISTID2), just as observed for wild-type NMNAT2 (Fig. 4B). These observations strongly support the function of ISTID2 in Golgi targeting. Strikingly, the recombinant NMNAT1-ISTID2 protein exhibited substantially reduced catalytic activity, which became comparable to the low wild-type NMNAT2 activity (Fig. 4C). This observation suggests that attachment of NMNAT to the Golgi complex via ISTID2 strongly inhibits catalytic activity. Indeed, as shown above (Fig. 3B), NMNAT2 lacking its ISTID2 relocalized to the cytosol and was at least twice as active compared with the wild-type enzyme (Fig. 2B).

FIGURE 4.

ISTID2 mediates targeting to the Golgi complex and reduces catalytic activity. A, wild-type (wt) NMNAT2 bearing a C-terminal eGFP tag (NMNAT2-eGFP) and the FLAG-ISTID2-eGFP fusion protein were overexpressed in HeLa S3 cells to determine their subcellular localization. B, a mutant construct of NMNAT1 (NMNAT1-ISTID2) in which ISTID1 was replaced with ISTID2 from NMNAT2 was overexpressed in HeLa S3 cells. The proteins were visualized by FLAG immunocytochemistry. C, substitution of ISTID1 with ISTID2 in NMNAT1 redirected the protein to the Golgi complex and reduced the activity to the level of wild-type NMNAT2. Note that purified recombinant wild-type NMNAT1 is ∼20 times more active compared with wild-type NMNAT2 (27). The experimental details were identical to those described in the legend to Fig. 2. RLU, relative light units; c, control.

NMNAT2 Associates with the External Surface of the Golgi Complex by Cysteine Palmitoylation

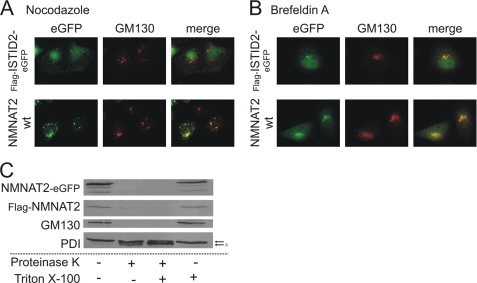

We then studied the distribution of wild-type NMNAT2 and the FLAG-ISTID2-eGFP fusion protein following treatment of cells with nocodazole or BFA, which both specifically disrupt Golgi structures. Nocodazole induces a block of secretory transport that causes a dispersion of the perinuclear Golgi ribbon into functional ministacks (54). Both wild-type NMNAT2 and the FLAG-ISTID2-eGFP fusion protein were found at these structures after treatment of cells with nocodazole as indicated by the co-localization with GM130 (Fig. 5A). On the other hand, BFA induces ER redistribution of luminal Golgi proteins (55). GM130 and several other proteins that are associated at the cytosolic surface of the Golgi complex are partially resistant to BFA-induced ER redistribution (56, 57) and rather move along retrograde tubules to ER exit sites (58). As shown in Fig. 5B, both wild-type NMNAT2 and FLAG-ISTID2-eGFP co-localized preferentially with GM130, rather than with the ER, after BFA treatment. These observations indicate that NMNAT2 is not a luminal protein.

FIGURE 5.

NMNAT2 localizes to the cytoplasmic surface of the Golgi complex. The influence of nocodazole (10 μm, 180 min) and BFA (5 μg/ml, 30 min) on the subcellular localization of NMNAT2-eGFP or FLAG-ISTID2-eGFP is shown in A and B, respectively. GM130, a cis-Golgi-associated marker protein, was immunostained for comparison. C, a protease protection assay was performed to determine the topology of NMNAT2 association with the Golgi complex. HeLa S3 cells overexpressing C-terminally eGFP-tagged or N-terminally FLAG-tagged wild-type (wt) NMNAT2 protein were gently disrupted and subjected to proteinase K digestion in the presence or absence of Triton X-100. In subsequent Western blot analyses, the digestion of NMNAT2 as well as of the Golgi marker protein GM130 (which faces the cytosolic surface) and the luminal ER-resident marker protein-disulfide isomerase (PDI) was probed using specific antibodies. Bands corresponding to protein-disulfide isomerase are indicated by arrows. The asterisk indicates the cleavage product of protein-disulfide isomerase.

To test this, HeLa S3 cells overexpressing wild-type NMNAT2 (either fused with eGFP or endowed with a FLAG tag) were gently homogenized to preserve intracellular organelles. The lysates were incubated with proteinase K in the absence or presence of detergent. As shown in Fig. 5C, both NMNAT2 proteins were readily degraded, independent of the presence of detergent, similar to GM130. In contrast, luminal proteins such as ER-localized protein-disulfide isomerase were far less susceptible to degradation in the absence of detergent (Fig. 5C). Consequently, NMNAT2 is most likely located at the cytosolic surface of the Golgi complex.

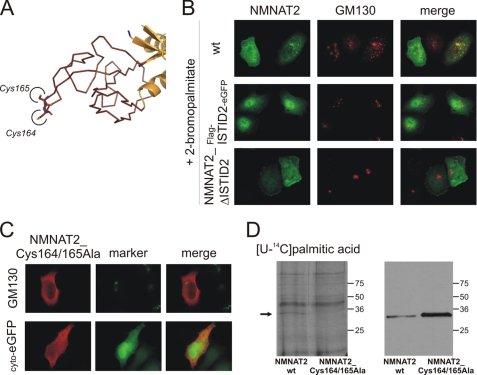

This topology suggested that targeting of NMNAT2 to the Golgi does not depend on classical co-translational translocation into the ER. Closer inspection of its predicted structure revealed two adjacent cysteines, Cys164 and Cys165, at the very tip of the ISTID predicted fold (Fig. 6A). Such an arrangement appeared intriguing, as it might serve to anchor a protein to intracellular membranes by palmitoylation. This supposition was tested using HeLa S3 cells transiently transfected with plasmids encoding wild-type NMNAT2 or the FLAG-ISTID2-eGFP fusion protein. After 18 h of expression in the presence of the palmitoylation inhibitor 2-BP, both proteins failed to associate with the Golgi complex and localized to the cytoplasm instead (Fig. 6B). As shown in Fig. 6C, mutant NMNAT2 in which both cysteines were replaced with alanines (NMNAT2_Cys164/165Ala) displayed the same cytoplasmic localization as observed for the ISTID2 deletion mutant NMNAT2_ΔISTID2 (Fig. 3B). This redistribution was also observed for single substitution mutants in which either Cys164 or Cys165 was replaced (data not shown). Finally, in vivo palmitoylation was verified by incubation of transfected HeLa S3 cells with 14C-labeled palmitic acid. In addition to the background labeling of endogenous proteins, a distinct band at ∼34 kDa was detected (Fig. 6D, left panel). This band corresponded to wild-type NMNAT2 as confirmed by Western blotting (Fig. 6D, right panel). We noted that the cysteine mutant NMNAT2_Cys164/165Ala was consistently more strongly expressed than the wild-type protein (Fig. 6D, right panel). Nevertheless, only expression of the wild-type (but not the mutant) protein resulted in detectable palmitoylation of NMNAT2.

FIGURE 6.

Cysteine-specific palmitoylation within ISTID2 anchors NMNAT2 at the Golgi complex. A, the tertiary structure prediction for NMNAT2 suggests that Cys164 and Cys165 are located at the very tip of ISTID2. B, FLAG-tagged wild-type (wt) NMNAT2, the ISTID2 deletion mutant (NMNAT2_ΔISTID2), or the FLAG-ISTID2-eGFP fusion protein was overexpressed in HeLa S3 cells in the presence of 25 μm 2-BP to inhibit protein palmitoylation. The endogenous 2-BP-resistant Golgi marker GM130 was immunostained for comparison. C, substitution of Cys164 and Cys165 with alanine caused relocalization of NMNAT2 to the cytoplasm. After overexpression in HeLa S3 cells, the double mutant NMNAT2_Cys164/165Ala was visualized by FLAG immunocytochemistry. The endogenous Golgi marker GM130 or coexpressed cytosolic eGFP (cyto-eGFP) was used for comparison. D, shown is the in vivo palmitoylation of NMNAT2. HeLa S3 cells overexpressing FLAG-tagged wild-type NMNAT2 or mutant NMNAT2_Cys164/165Ala were incubated with [14C]palmitic acid. Cell extracts were separated by SDS-PAGE and subjected to autoradiography (left panel) and FLAG immunoblot analyses (right panel). The arrow indicates a radiolabeled band (∼34 kDa) that corresponds to FLAG-tagged wild-type NMNAT2.

NMNAT3 Is Targeted to Mitochondria by Its N Terminus

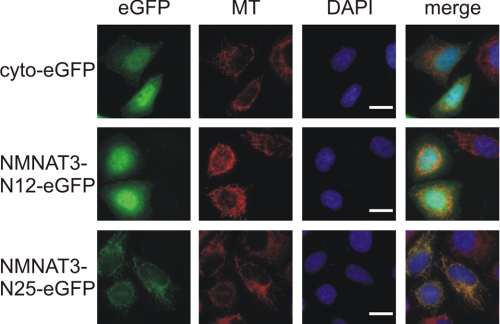

Because mitochondrial targeting of NMNAT3 was independent of its ISTID (Fig. 3C), we tested whether it was mediated by the N-terminal amino acids, as generally observed for matrix proteins. Expression vectors were generated encoding the first 12 or 25 amino acids of NMNAT3, N-terminally fused to eGFP. When overexpressed in HeLa S3 cells, the construct with only 12 N-terminal amino acids of NMNAT3 localized to the cytosol, whereas the first 25 amino acids were sufficient to direct eGFP to the mitochondria (Fig. 7).

FIGURE 7.

Mitochondrial targeting of NMNAT3 is mediated by its N-terminal sequence. The N-terminal 12 or 25 amino acids of human NMNAT3 were fused N-terminally to cytosolic eGFP (cyto-eGFP). The resulting constructs (NMNAT3-N12-eGFP and NMNAT3-N25-eGFP, respectively) were overexpressed in HeLa S3 cells. The proteins were visualized by their intrinsic eGFP fluorescence. Mitochondria were stained with MitoTracker CMXRos (MT; shown in red). The cell nuclei were visualized by 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) staining (shown in blue). Scale bars = 10 μm.

ISTIDs Evolved under Differential Selective Pressure

The experimental observations revealed that the ISTIDs carry important isoform-specific functions. Although the ISTIDs of human NMNAT1 and NMNAT2 mediate different subcellular targeting and post-translational modifications, no such role was detected for ISTID3. Given their functional diversity, the ISTIDs might have evolved under differential selective pressure. This notion was supported by estimations of the rates of nucleotide substitutions in the genes of vertebrate NMNAT orthologs (Table 1) based on multiple sequence alignments (supplemental Fig. S4, A–C). The ISTIDs of NMNAT1 and NMNAT2 appear to have evolved rather independently compared with the remaining catalytic part of the protein. In contrast, the ISTID of NMNAT3 apparently evolved neutrally, not being subject to selective pressure. These results are fully in line with the functional analyses of the ISTIDs of the three NMNAT isoforms.

TABLE 1.

Estimation of evolutionary pressure on ISTIDs

Annotated NMNAT sequences of various vertebrate species (see Fig. S4, A–C) were analyzed using PAML as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Substitution rate ratios (ω) were estimated separately for ISTIDs and the remaining sequences of the respective NMNAT isoforms.

| Substitution rate ratios (ω) according to two-fixed-sites model E |

Predicted selective pressure on ISTID | Statistical significance of model E compared with |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ISTID (ω1) | NMNAT excluding ISTID (ω0) | ln L | Model E, adjusted, ω1 = 1 | Model C, w0 = ω1 | ||

| NMNAT1 | 0.39 | 0.1 | −5727.9 | Purifying | **a | ** |

| NMNAT1ΔNLSb | 0.59 | 0.1 | −5593.7 | * | ** | |

| NMNAT2 | 0.038 | 0.02 | −5308.0 | Purifying | ** | ** |

| NMNAT3 | 0.88 | 0.1 | −2890.2 | Neutral | NSc | ** |

a **, p < 0.001 (likelihood ratio test, degrees of freedom = 2); *, p < 0.05 (likelihood ratio test, degrees of freedom = 2).

b The analyses were conducted after removing the highly conserved predicted nuclear localization signal in the ISTID sequences of NMNAT1 (cf. Fig. S4, A–C).

c NS, not significant (p > 0.05; likelihood ratio test, degrees of freedom = 2).

DISCUSSION

Several observations of this study support the conclusion that NMNATs from higher eukaryotes have acquired specific sequence insertions for subcellular targeting and post-translational modifications and to mediate regulatory functions. Apparently, the rather unusual subcellular distribution of these enzymes has evolved under strong selective pressure, indicating that their activity in the different subcellular compartments is essential for the development of higher eukaryotes.

ISTID1 and ISTID2 Have Acquired Highly Specialized Functions for Targeting and Regulation

Our data demonstrate that ISTID2 contains a targeting motif that directs NMNAT2 to the Golgi complex. Moreover, the protein is post-translationally modified, i.e. by palmitoylation, within its ISTID. Significantly, similar characteristics were found for nuclear NMNAT1 in a region here identified as its ISTID. ISTID1 of NMNAT1 contains both the signal directing the protein to its subcellular destination (Fig. 3A) and a site for post-translational modification (18) (cf. Fig. 1E). Because prokaryotic NMNATs do not contain ISTIDs, these domain insertions may have arisen as an evolutionary advantage for higher eukaryotes to carry specific functions beyond their catalytic activity. As we have demonstrated, the ISTIDs of all three human NMNATs are fully dispensable for their catalytic activities. Furthermore, comparisons of coding sequences for the individual NMNAT isoforms and their corresponding ISTIDs among vertebrates suggest that the compositions of ISTID1 and ISTID2 have evolved under selective pressure (Table 1). This suggestion is consistent with the observed functional properties of these ISTIDs.

The N-terminal Sequence of NMNAT3 Rather than ISTID3 Is Important for Mitochondrial Targeting

ISTID3 is not required for the targeting of NMNAT3 to mitochondria (Fig. 3C). The majority of nuclear encoded mitochondrial proteins follow the presequence pathway, which depends on the recognition of their N-terminal targeting sequence (59, 60). This pathway is likely to apply to NMNAT3 because its N-terminal sequence mediated mitochondrial localization of eGFP. Indeed, targeting of a matrix protein by an internal peptide sequence would be difficult to comprehend based on the known mitochondrial import pathways. It appears likely therefore that ISTID3 does not have a targeting function, consistent with the predicted lack of evolutionary pressure. However, it cannot be excluded that ISTID3 serves other functions, which have so far not been recognized.

Anchoring of NMNAT2 at the Golgi Complex May Regulate Cytosolic NAD Supply

Another important result of this study is the identification of the mechanism for targeting NMNAT2 to cis- and medial-Golgi structures. ISTID2 is essential and sufficient to mediate Golgi association because it directed eGFP as well as NMNAT1 to the same location as found for wild-type NMNAT2. Moreover, our results document that NMNAT2 is attached to the cytosolic surface of the Golgi complex via cysteine palmitoylation in ISTID2. Taking into account that initial membrane contact is a prerequisite for palmitoyl transfer (61), these results suggest that ISTID2 directs NMNAT2 to membranes of the Golgi complex, whereas reversible palmitoylation anchors it there.

NMNAT2 catalyzes both NAD+ synthesis and NAD+ cleavage at rates that are ∼20 times lower compared with NMNAT1 (27). The significant enhancement of catalytic activity when palmitoylation is precluded may provide an unusual mechanism for enzymatic regulation. The enzyme might be membrane-anchored in an inactive form to maintain a pool of NAD biosynthetic capacity, which can be made readily available to the cytosol when needed. The observation that association of NMNAT1 with the Golgi complex (when ISTID1 was replaced with ISTID2) also resulted in a considerable reduction of the catalytic activity lends support to this concept. Moreover, mutation of the cysteines that are targets for palmitoylation led to cytosolic localization of the protein (Fig. 6C) and was accompanied by a significantly higher catalytic activity (data not shown). Further studies should explore under which conditions NMNAT2 might be detached from the Golgi complex by depalmitoylation. Besides this intriguing but still speculative mechanism, several other possibilities can be considered to explain the rather unexpected subcellular localization of NMNAT2. A general impact of NMNAT2 on Golgi structure and function can most probably be excluded due to the tissue-specific expression (29, 62, 63). The NAD-consuming poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase isoforms tankyrase 1 and tankyrase 2 and the NAD-binding CtBP1 (C-terminal binding protein-1) splice variant CtBP3/BARS-50 were localized to the Golgi apparatus (64–66) and may therefore represent potential functional interaction partners.

In conclusion, the results of this study have revealed highly specialized subcellular targeting modes for distinct enzyme isoforms that catalyze a vital metabolic reaction. The acquisition of ISTIDs, inserted into the catalytic folds, has not only enabled individual targeting but also provided the possibility to mediate regulatory functions. Although the ISTID of NMNAT1 participates in the regulation of PARP1 activity in the nucleus (18), transient palmitoylation of ISTID2 may have a critical role in the maintenance of the cytosolic NAD homeostasis by controlling the active state of NMNAT2. The identification of ISTIDs as functional units in mammalian NMNATs thus provides a molecular basis for isoform-specific non-catalytic functions of these important enzymes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Nathalie Reuter for support regarding protein structure prediction and Dr. Jaakko Saraste for helpful discussions and provision of antibodies. We are grateful to the Genome Center at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis for providing access to data on the lamprey (Petromyzon marinus) genome.

This work was supported by the National Research Council of Norway and the University of Bergen.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1–S4 and additional references.

- NMNAT

- nicotinamide mononucleotide adenylyltransferase

- ISTID

- isoform-specific targeting and interaction domain

- BFA

- brefeldin A

- 2-BP

- 2-bromopalmitate

- eGFP

- enhanced green fluorescent protein

- ecNadD

- E. coli NadD

- ER

- endoplasmic reticulum.

REFERENCES

- 1.Belenky P., Bogan K. L., Brenner C. (2007) Trends Biochem. Sci. 32, 12–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berger F., Ramírez-Hernández M. H., Ziegler M. (2004) Trends Biochem. Sci. 29, 111–118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ying W. (2008) Antioxid. Redox Signal. 10, 179–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hassa P. O., Haenni S. S., Elser M., Hottiger M. O. (2006) Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 70, 789–829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kraus W. L. (2008) Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 20, 294–302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schreiber V., Dantzer F., Ame J. C., de Murcia G. (2006) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 7, 517–528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dali-Youcef N., Lagouge M., Froelich S., Koehl C., Schoonjans K., Auwerx J. (2007) Ann. Med. 39, 335–345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Denu J. M. (2005) Trends Biochem. Sci. 30, 479–483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Finkel T., Deng C. X., Mostoslavsky R. (2009) Nature 460, 587–591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haigis M. C., Guarente L. P. (2006) Genes Dev. 20, 2913–2921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fliegert R., Gasser A., Guse A. H. (2007) Biochem. Soc. Trans. 35, 109–114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guse A. H., Lee H. C. (2008) Sci. Signal. 1, re10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lau C., Niere M., Ziegler M. (2009) Front. Biosci. 14, 410–431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Magni G., Amici A., Emanuelli M., Orsomando G., Raffaelli N., Ruggieri S. (2004) Curr. Med. Chem. 11, 873–885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Magni G., Orsomando G., Raffelli N., Ruggieri S. (2008) Front. Biosci. 13, 6135–6154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhai R. G., Rizzi M., Garavaglia S. (2009) Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 66, 2805–2818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhai R. G., Zhang F., Hiesinger P. R., Cao Y., Haueter C. M., Bellen H. J. (2008) Nature 452, 887–891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Berger F., Lau C., Ziegler M. (2007) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 3765–3770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schweiger M., Hennig K., Lerner F., Niere M., Hirsch-Kauffmann M., Specht T., Weise C., Oei S. L., Ziegler M. (2001) FEBS Lett. 492, 95–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Araki T., Sasaki Y., Milbrandt J. (2004) Science 305, 1010–1013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mack T. G., Reiner M., Beirowski B., Mi W., Emanuelli M., Wagner D., Thomson D., Gillingwater T., Court F., Conforti L., Fernando F. S., Tarlton A., Andressen C., Addicks K., Magni G., Ribchester R. R., Perry V. H., Coleman M. P. (2001) Nat. Neurosci. 4, 1199–1206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anderson R. M., Bitterman K. J., Wood J. G., Medvedik O., Cohen H., Lin S. S., Manchester J. K., Gordon J. I., Sinclair D. A. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 18881–18890 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Conforti L., Fang G., Beirowski B., Wang M. S., Sorci L., Asress S., Adalbert R., Silva A., Bridge K., Huang X. P., Magni G., Glass J. D., Coleman M. P. (2007) Cell Death Differ. 14, 116–127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sasaki Y., Vohra B. P., Lund F. E., Milbrandt J. (2009) J. Neurosci. 29, 5525–5535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang J., Zhai Q., Chen Y., Lin E., Gu W., McBurney M. W., He Z. (2005) J. Cell Biol. 170, 349–355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang J., He Z. (2009) Cell Adh. Migr. 3, 77–87 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Berger F., Lau C., Dahlmann M., Ziegler M. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 36334–36341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang X., Kurnasov O. V., Karthikeyan S., Grishin N. V., Osterman A. L., Zhang H. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 13503–13511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sorci L., Cimadamore F., Scotti S., Petrelli R., Cappellacci L., Franchetti P., Orsomando G., Magni G. (2007) Biochemistry 46, 4912–4922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Herrero-Yraola A., Bakhit S. M., Franke P., Weise C., Schweiger M., Jorcke D., Ziegler M. (2001) EMBO J. 20, 2404–2412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hallows W. C., Lee S., Denu J. M. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 10230–10235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nakagawa T., Lomb D. J., Haigis M. C., Guarente L. (2009) Cell 137, 560–570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Contreras-Moreira B., Bates P. A. (2002) Bioinformatics 18, 1141–1142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Garavaglia S., D'Angelo I., Emanuelli M., Carnevali F., Pierella F., Magni G., Rizzi M. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 8524–8530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pollastri G., McLysaght A. (2005) Bioinformatics 21, 1719–1720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Adamczak R., Porollo A., Meller J. (2005) Proteins 59, 467–475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cole C., Barber J. D., Barton G. J. (2008) Nucleic Acids Res. 36, W197–W201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ouali M., King R. D. (2000) Protein Sci. 9, 1162–1176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pollastri G., Przybylski D., Rost B., Baldi P. (2002) Proteins 47, 228–235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McGuffin L. J., Bryson K., Jones D. T. (2000) Bioinformatics 16, 404–405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McGuffin L. J., Jones D. T. (2003) Bioinformatics 19, 874–881 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.DeLano W. L. (2002) The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, DeLano Scientific LLC, San Carlos, CA [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chenna R., Sugawara H., Koike T., Lopez R., Gibson T. J., Higgins D. G., Thompson J. D. (2003) Nucleic Acids Res. 31, 3497–3500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Clamp M., Cuff J., Searle S. M., Barton G. J. (2004) Bioinformatics 20, 426–427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hubbard T. J., Aken B. L., Ayling S., Ballester B., Beal K., Bragin E., Brent S., Chen Y., Clapham P., Clarke L., Coates G., Fairley S., Fitzgerald S., Fernandez-Banet J., Gordon L., Graf S., Haider S., Hammond M., Holland R., Howe K., Jenkinson A., Johnson N., Kahari A., Keefe D., Keenan S., Kinsella R., Kokocinski F., Kulesha E., Lawson D., Longden I., Megy K., Meidl P., Overduin B., Parker A., Pritchard B., Rios D., Schuster M., Slater G., Smedley D., Spooner W., Spudich G., Trevanion S., Vilella A., Vogel J., White S., Wilder S., Zadissa A., Birney E., Cunningham F., Curwen V., Durbin R., Fernandez-Suarez X. M., Herrero J., Kasprzyk A., Proctor G., Smith J., Searle S., Flicek P. (2009) Nucleic Acids Res. 37, D690–D697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Birney E., Clamp M., Durbin R. (2004) Genome Res. 14, 988–995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Edgar R. C. (2004) Nucleic Acids Res. 32, 1792–1797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Suyama M., Torrents D., Bork P. (2006) Nucleic Acids Res. 34, W609–W612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Felsenstein J. (1989) Cladistics 5, 164–166 [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yang Z. (1997) Comput. Appl. Biosci. 13, 555–556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yang Z., Swanson W. J. (2002) Mol. Biol. Evol. 19, 49–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Couture J. F., Legrand P., Cantin L., Labrie F., Luu-The V., Breton R. (2004) J. Mol. Biol. 339, 89–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sasaki Y., Araki T., Milbrandt J. (2006) J. Neurosci. 26, 8484–8491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yang W., Storrie B. (1998) Mol. Biol. Cell 9, 191–207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lippincott-Schwartz J., Yuan L. C., Bonifacino J. S., Klausner R. D. (1989) Cell 56, 801–813 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nakamura N., Rabouille C., Watson R., Nilsson T., Hui N., Slusarewicz P., Kreis T. E., Warren G. (1995) J. Cell Biol. 131, 1715–1726 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Seemann J., Jokitalo E., Pypaert M., Warren G. (2000) Nature 407, 1022–1026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mardones G. A., Snyder C. M., Howell K. E. (2006) Mol. Biol. Cell 17, 525–538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bolender N., Sickmann A., Wagner R., Meisinger C., Pfanner N. (2008) EMBO Rep. 9, 42–49 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Neupert W., Herrmann J. M. (2007) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 76, 723–749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Resh M. D. (2006) Sci. STKE 2006, re14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Raffaelli N., Sorci L., Amici A., Emanuelli M., Mazzola F., Magni G. (2002) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 297, 835–840 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yalowitz J. A., Xiao S., Biju M. P., Antony A. C., Cummings O. W., Deeg M. A., Jayaram H. N. (2004) Biochem. J. 377, 317–326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chi N. W., Lodish H. F. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 38437–38444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lyons R. J., Deane R., Lynch D. K., Ye Z. S., Sanderson G. M., Eyre H. J., Sutherland G. R., Daly R. J. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 17172–17180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Weigert R., Silletta M. G., Spanò S., Turacchio G., Cericola C., Colanzi A., Senatore S., Mancini R., Polishchuk E. V., Salmona M., Facchiano F., Burger K. N., Mironov A., Luini A., Corda D. (1999) Nature 402, 429–433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.