Abstract

Skin conductance level reactivity (SCLR) was examined as a moderator of the association between harsh parenting and child externalizing behavior. Participants were 251 boys and girls (8–9 years). Mothers and fathers provided reports of harsh parenting and their children’s externalizing behavior; children also provided reports of harsh parenting. SCLR was assessed in response to a socioemotional stress task and a problem-solving challenge task. Regression analyses revealed that the association between harsh parenting and externalizing behavior was stronger among children with lower SCLR, as compared to children with higher SCLR. SCLR may be a more robust moderator among boys compared to girls. Results are discussed with regard to theories on antisocial behavior and multiple-domain models of child development.

Externalizing behavior problems in childhood and their persistence in adolescence and adulthood are remarkably costly in terms of human suffering and societal expenditures (Foster, Jones, & the Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group, 2006). For example, Cohen (1998) estimated that high-risk antisocial youth may generate costs of $2 million, including costs of the criminal justice system as well as treatment and missed earnings of the offender and victim (as cited in Foster et al., 2006). Precise identification of risk factors and processes that potentiate or ameliorate them has the potential to advance understanding of externalizing problems and to curb this significant societal problem.

Harsh parenting refers to coercive acts and negative emotional expressions that parents direct toward children, including verbal aggression (e.g., yelling or name calling) and physical aggression (e.g., spanking or hitting; Chang, Schwartz, Dodge, & McBride-Chang, 2003). Harsh parenting is among the most reliable correlates of child aggressive and disruptive behavior (Gershoff, 2002), and mechanisms of transmission have been specified and supported empirically (Patterson, 2002). Nonetheless, children’s susceptibility to harsh parenting varies on the basis of temperamental and self-regulatory characteristics (Bates & Pettit, 2007). Some children exposed to parental aggression do not exhibit externalizing behavior problems, and even among those who do, variability exists. Contemporary developmental perspectives contend that individual differences in physiological responding shape the psychological and behavioral outcomes among children exposed to environmental stressors (Beauchaine, Gatzke-Kopp, & Mead, 2007; Cummings, El-Sheikh, Kouros, & Keller, 2007; El-Sheikh, Keller, & Erath, 2007; El-Sheikh & Whitson, 2006; Steinberg & Avenevoli, 2000). As such, physiological arousal in response to harsh discipline may influence children’s behavioral response. Skin conductance level reactivity (SCLR), which is measured as increase in skin conductance level from baseline to stressful or challenging laboratory tasks, is a relevant physiological marker because it appears to reflect sensitivity to aversive or punishing circumstances (Raine, 2002), as discussed in further detail below. In the present study, we adopted a biopsychosocial perspective and investigated whether SCLR to stressful or challenging laboratory tasks moderated the association between harsh parenting and child externalizing behavior.

Harsh Parenting and Child Externalizing Behavior

Numerous studies have linked harsh parenting with child externalizing behavior (Gershoff, 2002). The relation is likely reciprocal, and there is compelling evidence from longitudinal and intervention studies that harsh parenting contributes to externalizing behavior (Patterson, 2002; Pettit & Arsiwalla, 2008). It appears that parents who use harsh and coercive strategies when confronting child misbehaviors inadvertently foster further aggressive and disruptive behavior. According to social learning theory, exposure to parental aggression can disinhibit aggressive behavior, foster aggressive problem-solving scripts, and provide a model for aggressive responding that can generalize to other interpersonal situations (Bandura, 1977). Furthermore, in the context of repeated angry parent–child exchanges, coercive patterns often develop in which escalating aggressive behavior elicits submission and thus becomes entrenched through negative reinforcement (Patterson, 2002). Repeated involvement in parent–child conflict may also sensitize children to the cues of impending conflict, such that even harmless disagreements with others (e.g., peers) are interpreted as signs of conflict that, in turn, heighten distress and trigger aggressive reactions (Cummings & Davies, 1994). Likewise, attachment and emotional security theories suggest that emotional reactivity and negative representations of parent–child relationships in response to conflict may begin to generalize across time and settings (Davies, Harold, Goeke-Morey, & Cummings, 2002).

Despite the relatively robust association between harsh parenting and child externalizing behavior, a growing body of research has shown that child characteristics account for variability in the strength of this association (Bates & Pettit, 2007). For example, vulnerability factors that may heighten the relation between harsh parenting and child externalizing behaviors in early and middle childhood include irritable distress (Morris et al., 2002), temperamental inflexibility (Paterson & Sanson, 1999), fearfulness (Colder, Lochman, & Wells, 1997), and low conscientiousness (Prinzie et al., 2003). A common interpretation is that these individual differences leave children more or less susceptible to harsh and hostile parenting.

At the physiological level, SCLR is a potential moderator. SCLR refers to electrodermal reactivity caused by the activity of sweat glands, which are innervated solely by the sympathetic (SNS) component of the autonomic nervous system (ANS). The SNS is activated in response to perceived stress or threat, preparing the body for a “fight-or-flight” response by increasing heart rate and oxygen flow throughout the body (Boucsein, 1992). The SNS response both affects and reflects an individual’s response to stress. That is, the degree of SNS activation affects the physiological resources available to mount an active behavioral response (Porges, 2007) and also reflects the sensitivity of the individual to the circumstance (Boucsein, 1992). SCLR is a moderately stable individual difference in middle childhood (El-Sheikh, 2007) and has been shown to operate as a moderator in the context of family stress, including marital conflict (El-Sheikh et al., 2007), parental depressive symptoms (Cummings et al., 2007), and paternal antisocial behavior (Shannon, Beauchaine, Brenner, Neuhaus, & Gatzke-Kopp, 2007).

SCLR is also a marker of the behavioral inhibition system (BIS), a neurophysiological motivational system that governs sensitivity to aversive circumstances or avoidance of aversive circumstances (Beauchaine, 2001; Fowles, 1980). The function of the BIS is to inhibit behaviors when aversive consequences are anticipated (Gray, 1987). Individuals with a weak BIS may thus experience low fearfulness and exhibit disinhibited behavior when faced with cues of punishment (Fowles, Kochanska, & Murray, 2000). The BIS is usually activated, and SCLR is typically observed, in the context of aversive circumstances, such as presentation of affectively charged stimuli or cues of punishment. Thus, low SCLR in aversive conditions has been conceptualized as a marker of fearlessness, failure of avoidance learning, or punishment insensitivity (Raine, 2002). In support of this proposition, Matthys, van Goozen, Snoek, and van Engeland (2004) reported a correlation between response preservation following experimental punishment (i.e., “door-opening task”) and lower skin conductance levels during the experimental procedure, suggesting that children with lower SCLR during the task were relatively insensitive to punishment.

The Present Study

Lower SCLR, and perhaps punishment insensitivity, is found among some children with externalizing behavior problems. However, whether sympathetic underarousal also exacerbates other risk factors for externalizing behaviors (e.g., harsh parenting) is not well understood. The primary aim of the present study is to examine whether low SCLR operates as a vulnerability factor for child externalizing behavior in the context of harsh parenting, and thereby, to better understand profiles of risk for externalizing behavior.

Individual differences in children’s SCLR may influence the link between harsh parenting and externalizing behavior. For example, SCLR may serve as a marker of children’s subjective experience of harsh parenting and the learning processes that occur in the context of harsh parent–child interactions. It is plausible that children who exhibit lower SCLR do not experience sufficient arousal in the context of harsh parental discipline to associate their inappropriate behavior with aversive emotional consequences or feelings of guilt, thereby reducing the effectiveness of harsh discipline as punishment (Hoffman, 1983, 1994; Raine, 2002). Furthermore, their relatively low arousal level may not disrupt cognitive processing in the context of harsh parent–child interactions, thus allowing these children to observe and perhaps learn from their parents’ coercive and aggressive behavior. Conversely, children who exhibit higher SCLR may experience harsh parenting behavior as more aversive physiologically and thus experience the punishing properties of harsh discipline. Although potentially more effective as an immediate behavioral suppressant among children who exhibit higher SCLR, harsh parenting may have unintended negative implications for these children as well. For example, at any level of SCLR, harsh discipline may generate feelings of rejection and fail to evoke empathic distress or direct attention to the consequences of one’s actions on others (Hoffman, 1983, 1994; Kochanska, 1993, 1997).

In the present study, we hypothesized that an association between harsh parenting and child externalizing behavior would exist among children who exhibited either higher or lower SCLR to stressful and challenging laboratory tasks; that is, we expected this relation to hold for all children to some extent. However, we anticipated that the association between harsh parenting and child externalizing behavior would be stronger among children who exhibited lower SCLR as compared to children who exhibited higher SCLR.

We tested this hypothesis using a relatively large and diverse, community-based sample and both child and parent reports of harsh parenting. Including both child and parent reports of harsh parenting allowed us to eliminate common informant bias in some analyses and to consider whether the hypothesized vulnerability function of lower SCLR would hold across independent perspectives on harsh parenting. Both perspectives are important: Parents are well positioned to assess their own behavior, whereas children’s subjective experience of harsh parenting may have greater implications for their physiological response and behavioral adjustment. SCLR was measured in response to a moderate socioemotional stress task (i.e., hearing an interadult argument) and a problem-solving challenge task (i.e., star tracing). Although we expected that hypotheses would be supported in similar ways across these tasks, we examined SCLR to each task separately, to evaluate whether the moderating role of SCLR is task specific or generalizes across stressful and challenging situations.

Given sex and ethnic differences in electrodermal activity (Boucsein, 1992), rates of externalizing behavior (e.g., Aber, Brown, & Jones, 2003), and responses to parental discipline (e.g., Kerr, Lopez, Olson, & Sameroff, 2004; Lansford, Deater-Deckard, Dodge, Bates, & Pettit, 2004), we controlled for these variables (as well as socioeconomic status [SES]) and also considered whether the moderating role of SCLR differed by sex or ethnicity. In addition, due to the common comorbidity of externalizing and internalizing problems (Hinden, Compas, Howell, & Achenbach, 1997) and a rationale for our hypotheses that is most relevant to “pure” externalizing problems (Keiley, Lofthouse, Bates, Dodge, & Pettit, 2003), we controlled for child-reported internalizing symptoms in analyses. We included child-reported internalizing symptoms and parent-reported externalizing behaviors, as parents and children are considered useful informants of these respective problems (Loeber, Green, & Lahey, 1990). Finally, we controlled for marital conflict to assess the direct and interactive associations of harsh parenting with child externalizing behavior independent of another significant family stressor (Cummings & Davies, 1994).

Method

Participants

Two hundred and fifty-one families participated, including 128 girls and 123 boys with a mean age of 8.23 years (SD = 0.73). Children were recruited from three school districts surrounding a small Southeastern town. Families were eligible to participate if children were in second or third grade, two parents were present in the home, and families had been living together for at least 2 years. Exclusion criteria included diagnoses of physical illness, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, learning disability, or mental retardation. Participating couples were married or had been living together for a substantial time period (M = 10 years, SD = 5.67), but due to misunderstandings, 10 families had been living together for less than 2 years (M = 1.1 years, SD = 0.28). Most children (73%) lived with both biological parents; 24% lived with their biological mom and a stepfather or mother’s live-in boyfriend, and the remaining 3% lived mostly with their biological father and a stepmother. The sample was representative of the communities from which it was drawn, with 64% European Americans and 36% African Americans (U.S. Census Bureau, 2005). The Hollingshead Index (Hollingshead, 1975) was used to determine SES and indicated that participating families represented the entire range of SES levels (1–5). Specifically, 25% were in Levels 1 or 2 (e.g., semiskilled workers), 34% were in Level 3 (e.g., skilled workers), and 41% were in Levels 4 and 5 (e.g., professionals). Sampling procedures allowed recruitment of both European American and African American families across a wide range of SES. Families were compensated monetarily for their participation.

Data for the present study were available from 100% of children, 96% of mothers, and 82% of fathers, and complete data on variables used in regression analyses were available for 88%–89% of families (n = 221–223) depending on the analysis. Participants with or without complete data did not differ on any variables included in the present study except that participants without complete data had slightly higher parent-reported harsh parenting, t(248) = 2.01, p < .05. Correlations among study variables and dummy-coded variables representing missing data on study variables (0 = missing, 1 = available) were significant in only 3 out of 110 possible cases (< 3%), and child externalizing behavior (the dependent variable) was not correlated with the missingness of any study variable. Complete case analysis is unlikely to bias regression coefficients when there is no relation between the dependent variable and the missingness of other study variables (Allison, 2003).

Procedure

Families visited the university laboratory for one session during which both parents and children completed questionnaires and children participated in a physiological assessment session. Electrodes were attached to the child during a 10-min warm-up period in which research assistants conversed with the parent and child to help the child relax. Next, the child was told that the parent would leave but would be next door for the remainder of the assessment session. Children were then allowed to acclimate to the laboratory for 2 min without their parent present. Skin conductance level (SCL) was then measured for a 3-min baseline period. Next, SCL was recorded while children listened to a 3-min audiotaped argument between a man and woman (i.e., socioemotional stress task). Children were randomly assigned to hear either an angry disagreement about in-laws or leisure activities. A similar number of boys and girls across each of the two ethnic groups were exposed to each theme. The validity of this task for assessing children’s physiological reactivity to socioemotional stress has been demonstrated in numerous studies (El-Sheikh, 2001, 2005, 2007; El-Sheikh, Harger, & Whitson, 2001). In addition, many studies have demonstrated that children respond with negative affect to enacted simulations of similar argument episodes, further supporting the designation of this task as a stress task (e.g., Cummings, Ballard, El-Sheikh, & Lake, 1991; Goeke-Morey, Cummings, Harold, & Shelton, 2003). This socioemotional stress task is referred to as the “stress task” throughout the remainder of the article.

Following a 6-min recovery period after the stress task, SCL was also measured during a star-tracing task, in which children were asked to trace a star using only a mirror image as a visual guide (mirror tracer; Lafayette Instrument Company, Lafayette, IN). This task is considered a problem-solving challenge task, and has been used to elicit SCLR or other forms of physiological reactivity in many studies (Allen & Matthews, 1997; El-Sheikh, 2007). This problem-solving challenge task is referred to as the “challenge task” throughout the remainder of the article. A fixed order of laboratory tasks was used because the focus of the study was on individual differences in physiological responding rather than task-specific responses per se. At the end of the session, children listened to a resolution of the argument for ethical purposes.

Measures

SCLR

Children’s SCL (expressed in microsiemens) was measured continuously throughout the laboratory session. Two Ag-AgCl electrodes filled with isotonic NaCl electrode gel were placed on the volar surfaces of distal phalanges of the first and second fingers of the nondominant hand using small Velcro bands. The area of gel contact was carefully controlled through the use of double-sided adhesive collars with a 1-cm hole in the center. A constant sinusoidal (AC) voltage (0.5 V rms) was used to avoid biasing the electrodes. A 16-channel A–D converter was used to digitize and amplify the signals. Software from the James Long Company (Caroga Lake, NY) was used to collect assessments at 1,000 readings per second. Averages for each of the three periods (baseline, response to stress task, response to challenge task) were calculated. As is typical in psychophysiological research, 7% of participants did not have skin conductance data due to equipment failure or measurement artifacts.

An SCL change score in response to each task was calculated by subtracting the initial SCL baseline score from SCL during the respective task. Notably, children’s SCL significantly increased from baseline in response to both the stress task, t(234) = −10.02, p < .01, and challenge task, t(231) = −16.86, p < .01 (see Table 1 for means and standard deviations). In accord with the law of initial values, to eliminate the influence of baseline SCL on skin conductance level reactivity, SCLR was computed as a residualized change score. The residualized change score is the residual variance when the respective SCL change score is regressed on baseline SCL. Two outliers (> 3 SD from the mean) were removed for analyses with SCLR to the challenge task, and six were removed for analyses with SCLR to the stress task. SCLR to the stress and challenge tasks were moderately correlated (see Table 2).

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for Girls and Boys

| Girls |

Boys |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | t | |

| Marital conflict (parents)a | 4.15 | 4.74 | 4.27 | 4.66 | 0.21 |

| Harsh parenting (parents)a | 5.67 | 3.66 | 6.06 | 3.77 | 0.83 |

| Harsh parenting (child)a | 4.39 | 4.04 | 6.57 | 5.45 | 3.56*** |

| SCL baselinea | 5.13 | 3.53 | 6.51 | 5.23 | 2.36* |

| SCL-stress taska | 5.99 | 4.06 | 7.60 | 5.89 | 2.44* |

| SCL-challenge taska | 7.97 | 4.97 | 9.56 | 6.42 | 2.12* |

| SCLR–stress taskb | −0.08 | 1.25 | −0.12 | 1.33 | −0.20 |

| SCLR–challenge taskb | 0.03 | 2.25 | −0.22 | 2.52 | −0.80 |

| Internalizing (child)c | 0.09 | 0.87 | −0.09 | 0.82 | −1.69 |

| Externalizing (parents)d | 49.52 | 6.91 | 47.91 | 7.63 | −1.76 |

Note. SCL levels expressed in microsiemens. SCL = skin conductance level; SCLR = skin conductance level reactivity.

Values are raw scores.

Values are unstandardized residualized change scores.

Values are averaged z scores.

Values are T scores.

p < .05.

p < .001.

Table 2.

Means, Standard Deviations, and Correlations Among Study Variables

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Sex | — | ||||||||||

| 2. Age (months) | −.16** | — | |||||||||

| 3. Ethnicity | .04 | −.08 | — | ||||||||

| 4. SES | −.03 | .07 | −.21** | — | |||||||

| 5. Marital conflict (parents) | −.01 | .04 | .16* | −.09 | — | ||||||

| 6. Harsh parenting (parents) | −.05 | .04 | .01 | .02 | .39*** | — | |||||

| 7. Harsh parenting (child) | −.22*** | −.06 | .09 | .04 | −.06 | .15* | — | ||||

| 8. SCLR–stress task | .01 | .01 | −.11 | .10 | .12 | .05 | −.02 | — | |||

| 9. SCLR–challenge task | .05 | .05 | −.19** | .11 | .06 | −.01 | −.16* | .51*** | — | ||

| 10. Internalizing (child) | .11 | −.13* | .12 | −.03 | −.01 | .06 | .31*** | .05 | −.04 | — | |

| 11. Externalizing (parents) | −.05 | .03 | .01 | −.12 | .15* | .43*** | .19** | −.13 | −.13* | .14* | — |

| M | — | 98.71 | — | 37.38 | 4.21 | 5.86 | 5.47 | −0.10 | −0.09 | 0.00 | 48.73 |

| SD | — | 8.64 | — | 9.92 | 4.69 | 3.71 | 4.90 | 1.29 | 2.38 | 0.85 | 7.30 |

Note. The number of participants included in analysis ranged from 224 to 251. For gender, boys are coded as 0 and girls are coded as 1. For ethnicity, European Americans are coded as 0 and African Americans are coded as 1. SCLR = skin conductance level reactivity.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Marital conflict

Mothers and fathers reported their own and their spouses’ verbal and physical aggression in the past year on the Conflict Tactics Scale, which has well-established reliability and validity (CTS2; Straus, Hamby, Boney-McCoy, & Sugarman, 1996). Parents rated their use of 18 behaviors during conflict on a 7-point scale, ranging from 0 (never) to 6 (more than 20 times). Mothers’ and fathers’ reports were averaged to create a marital conflict score; internal consistency was high (cross-subscale, cross-informant, cross-referent α = .85).

Harsh parenting

Mothers, fathers, and children completed the Parent–Child Conflict Tactics Scale (CTSPC; Straus, 1999), which is widely used to assess harsh parenting (Yodanis, Hill, & Straus, 2001). The CTSPC has well-established psychometric properties (Straus, 1999). Subscales utilized in the present study assessed the frequency of verbal aggression (e.g., shouted, yelled, or screamed; said he/she would send you away; five items rated on a 7-point scale) and physical aggression (e.g., spanked you on the bottom with bare hand; slapped you on the face or head or ears; nine items rated on a 7-point scale) that parents directed toward the child in the past year (ranging from never to more than 20 times). Mothers’ and fathers’ reports of their own and their spouses’ verbal (M = 6.43, SD = 4.04) and physical (M = 5.29, SD = 4.46) aggression toward the child were averaged to create a parent-reported harsh parenting score (cross-subscale, cross-reporter, cross-referent α = .82). Child reports of both parents’ verbal (M = 4.94, SD = 4.91) and physical (M = 5.99, SD = 6.16) aggression were also averaged to create a composite child-reported harsh parenting score with high internal consistency (cross-subscale, cross referent α = .88). Any instances of verbal aggression toward children were reported by 96% of parents and 86% of children, and any instances of physical aggression toward children were reported by 95% of parents and 89% of children (for high rates of “corporal punishment’ throughout the United States, especially in the Southern United States, see Straus & Stewart, 1999).

Child internalizing symptoms

Children completed the Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI; Kovacs, 198) via interview. The CDI is well established and known to have good reliability and validity (Kovacs, 1985). Internal consistency was α = .95 in the present sample. In addition, children completed the Revised Children’s Manifest Anxiety Scale (RCMAS; Reynolds & Richmond, 1979) via interview. This measure also has well-established reliability and validity (Reynolds & Richmond, 1979), and high internal consistency in the present study (α = .91). Children’s reports on the CDI and RCMAS were correlated, r = .46, p < .001; these scores were standardized and averaged to yield a composite score for child internalizing symptoms.

Child externalizing behavior

Both parents completed the Personality Inventory for Children–2 (PIC–2; Lachar & Gruber, 2001). The Externalization composite is composed of Delinquency and Impulsivity/Distractibility subscales, which include items that assess aggression, impulsivity, disruptive behavior, delinquency, and noncompliance. The PIC–2 has demonstrated test–retest reliability, interrater reliability, as well as discriminant and construct validity (Lachar & Gruber, 2001; Wirt, Lachar, Klinedinst, & Seat, 1990). For example, the externalizing scale of the PIC–2 was correlated (r = .55) with teacher-reported behavior problems on the Student Behavior Survey (SBS; Lachar, Wingenfeld, Kline, & Gruber, 2000). Likewise, El-Sheikh (2001) found that mother-reported externalizing problems on the PIC–2 were correlated with teacher-reported externalizing problems (r = .48, p < .001) on the Child Behavior Checklist–Teacher Report Form (Achenbach, 1991). In the present study, the internal consistency (α) of the Externalization composite was .83 for mothers and .84 for fathers. Mothers’ and fathers’ reports were correlated, r = .39, p < .001, and were averaged to represent child externalizing problems. Forty-five children (18%) were within the borderline or clinical range (T ≥ 60) of externalizing problems based on at least one parent’s report on the PIC–2.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Means and standard deviations of study variables are shown separately for girls and boys in Table 1. Boys reported that their mothers and fathers used more harsh parenting, as compared to girls, and boys had higher SCL than girls.

Correlations among study variables and full-sample means and standard deviations are presented in Table 2. Several correlations emerged with demographic variables. Older children reported lower internalizing symptoms. African Americans had lower SES, exhibited lower SCLR to the challenge task, and reported more marital conflict, as compared to European Americans. In addition, parent-reported harsh parenting was modestly correlated with child-reported harsh parenting and moderately correlated with child externalizing behavior. Child-reported harsh parenting was correlated with lower SCLR to the challenge task and higher internalizing and externalizing problems. SCLR to the stress and challenge tasks were moderately correlated. Internalizing and externalizing problems were also correlated.

Plan of Analysis

Hierarchical multiple regression analyses were used to test the main hypothesis—the association between harsh parenting and child externalizing behavior would be exacerbated among participants with lower SCLR and attenuated among participants with higher SCLR. Age, sex, ethnicity, SES, internalizing symptoms, and marital conflict were entered in the first step of each regression analysis to control for potential confounds. Parent- or child-reported harsh parenting and SCLR to the stress task or challenge task were entered in the second step of each analysis. The product of the respective harsh parenting and SCLR variables was entered in the third step to represent their interaction (Aiken & West, 1991; Baron & Kenny, 1986), the two-way product of sex and both the respective harsh parenting and SCLR variables was entered in the fourth step, and the three-way product of sex and the respective harsh parenting and SCLR variables was entered in the fifth step. In total, four regression analyses were conducted, with the following combinations of primary predictors: (a) parent-reported harsh parenting and SCLR to the stress task, (b) parent-reported harsh parenting and SCLR to the challenge task, (c) child-reported harsh parenting and SCLR to the stress task, and (d) child-reported harsh parenting and SCLR to the challenge task. The outcome variable in all analyses was parent-reported externalizing behavior. All predictor variables were centered. Analyses revealed no evidence for three-way (Harsh Parenting × SCLR × Ethnicity) or four-way (Harsh Parenting × SCLR × Gender × Ethnicity) interactions involving ethnicity; given the exploratory nature of these analyses, no further information is presented.

Calculation of simple intercepts and simple slopes to probe significant interactions was conducted according to standard procedures (Aiken & West, 1991; Dearing & Hamilton, 2006). These analyses yielded intercepts and slopes representing the relations between the predictor (harsh parenting) and outcome (child externalizing behavior) at lower (−1 SD) and higher (+1 SD) levels of the moderator (SCLR). It is important to note that a significant interaction term indicates that the associations between the predictor and outcome variable at higher versus lower SCLR are different from one another. The significance of the slope itself indicates whether the magnitude of the slope is significantly different from zero at a particular level of SCLR.

Main Analyses

Parent-reported harsh parenting and SCLR-stress task

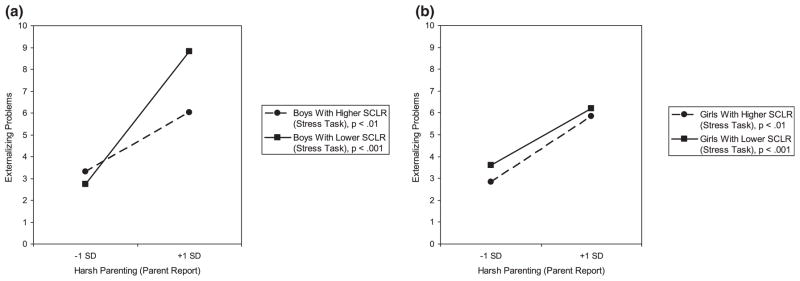

As shown in Table 3, higher levels of parent-reported harsh parenting and lower levels of SCLR-stress task were each independently associated with higher child externalizing behavior, above and beyond demographic variables, internalizing symptoms, and marital conflict. These main effects were qualified by a significant two-way interaction between harsh parenting and SCLR-stress task, which was itself qualified by a three-way interaction among harsh parenting, SCLR-stress task, and sex. Follow-up analyses revealed that harsh parenting was significantly associated with externalizing behavior among boys or girls with lower or higher SCLR-stress task. However, the association between harsh parenting and externalizing behavior was stronger among boys with lower SCLR-stress task, B = .79, SE = .12, p < .0001, as compared to boys with higher SCLR-stress task, B = .34, SE = .11, p < .01 (see Figure 1a). Among girls, the significant association between harsh parenting and externalizing behavior was not different at lower, B = .39, SE = .11, p < .001, versus higher, B = .45, SE = .14, p < .01, levels of SCLR-stress task (see Figure 1b).

Table 3.

SCLR as a Moderator of Parent-Reported Harsh Parenting

| Predictors | Externalizing behavior (parent report) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stress task |

Challenge task |

|||||

| βstep | ΔF | ΔR2 | βstep | ΔF | ΔR2 | |

| Step 1 | ||||||

| Age | .02 | 2.13 | .06 | .04 | 2.08 | .06 |

| Sex | −.08 | −.07 | ||||

| Ethnicity | −.06 | −.05 | ||||

| Socioeconomic status | −.10 | −.12 | ||||

| Internalizing symptoms | .14* | .13 | ||||

| Marital conflict | .14* | .14* | ||||

| Step 2 | ||||||

| Harsh parenting (parent report) | .45*** | 29.04 | .20*** | .46*** | 28.38 | .20*** |

| SCLR | −.16* | −.12* | ||||

| Step 3 | ||||||

| Harsh Parenting × SCLR | −.14* | 5.30 | .02* | −.20** | 11.02 | .04** |

| Step 4 | ||||||

| Harsh Parenting × Sex | −.11 | 1.15 | .01 | −.12 | 2.08 | .01 |

| SCLR × Sex | .05 | .11 | ||||

| Step 5 | ||||||

| Harsh Parenting × SCLR × Sex | .17* | 4.55 | .02* | .00 | 0.00 | .00 |

Note. n = 221 for stress task analysis; n = 223 for challenge task analysis. For gender, boys are coded as 0 and girls are coded as 1. For ethnicity, European Americans are coded as 0 and African Americans are coded as 1. SCLR = skin conductance level reactivity.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Figure 1.

(a) Associations between parent-reported harsh parenting and child externalizing behavior among boys with higher or lower skin conductance level reactivity (SCLR) to the stress task. A raw score of 6 on externalizing problems = T score of 50. (b) Associations between parent-reported harsh parenting and child externalizing behavior among girls with higher or lower SCLR to the stress task. A raw score of 5 on externalizing problems = T score of 50.

Parent-reported harsh parenting and SCLR-challenge task

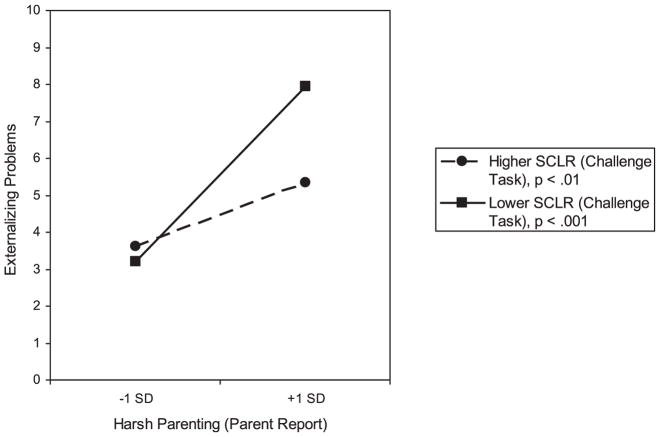

As shown in Table 3, higher levels of parent-reported harsh parenting and lower levels of SCLR to the challenge task were each uniquely associated with child externalizing behavior. An interaction emerged between harsh parenting and SCLR-challenge task, but no additional two- or three-way interactions with sex were found. Follow-up analyses revealed that the association between harsh parenting and externalizing behavior was stronger among children with lower SCLR-challenge task, B = .67, SE = .08, p < .0001, as compared to children with higher SCLR-challenge task, B = .24, SE = .08, p < .01 (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Associations between parent-reported harsh parenting and child externalizing behavior among boys and girls with higher or lower skin conductance level reactivity (SCLR) to the challenge task.

Note. For boys, a raw score of 6 on externalizing problems = T score of 50; for girls, a raw score of 5 on externalizing problems = T score of 50.

Child-reported harsh parenting and SCLR-stress task

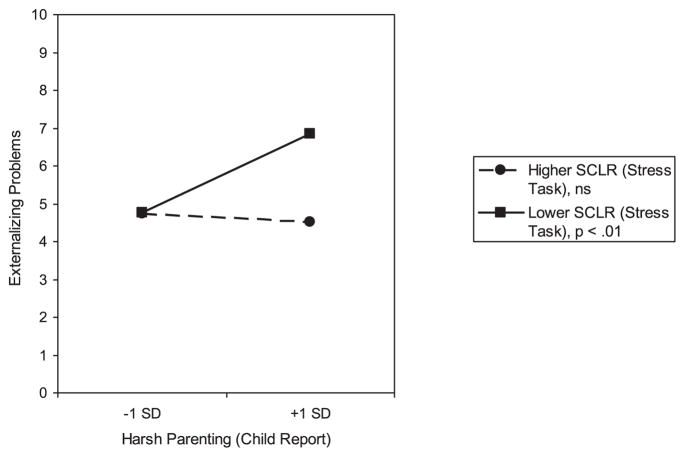

As shown in Table 4, lower SCLR to the stress task was uniquely associated with higher child externalizing behavior. In addition, the interaction between child-reported harsh parenting and SCLR-stress task was associated with child externalizing behavior. No interactions with sex were significant. Follow-up analyses revealed that the association between harsh parenting and externalizing behavior was significant among children with lower SCLR-stress task, B = .22, SE = .07, p < .01, but not among children with higher SCLR-stress task, B = −.02, SE = .08, ns (see Figure 3).

Table 4.

SCLR as a Moderator of Child-Reported Harsh Parenting

| Predictors | Externalizing behavior (parent report) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stress task |

Challenge task |

|||||

| βstep | ΔF | ΔR2 | βstep | ΔF | ΔR2 | |

| Step 1 | ||||||

| Age | .02 | 2.16 | .06* | .03 | 2.11 | .06 |

| Sex | −.07 | −.06 | ||||

| Ethnicity | −.05 | −.04 | ||||

| Socioeconomic status | −.10 | −.12 | ||||

| Internalizing symptoms | .15* | .13 | ||||

| Marital conflict | .15* | .14* | ||||

| Step 2 | ||||||

| Harsh parenting (child report) | .11 | 4.58 | .04* | .09 | 3.24 | .03* |

| SCLR | −.17* | −.14* | ||||

| Step 3 | ||||||

| Harsh Parenting × SCLR | −.14* | 4.15 | .02* | −.13* | 3.95 | .02* |

| Step 4 | ||||||

| Harsh Parenting × Sex | −.11 | 0.85 | .01 | −.13 | 1.14 | .01 |

| SCLR × Sex | .01 | .02 | ||||

| Step 5 | ||||||

| Harsh Parenting × SCLR × Sex | .08 | 0.80 | .00 | .16 | 2.65 | .01 |

Note. n = 221 for stress task analysis; n = 223 for challenge task analysis. For gender, boys are coded as 0 and girls are coded as 1. For ethnicity, European Americans are coded as 0 and African Americans are coded as 1. SCLR = skin conductance level reactivity.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Figure 3.

Associations between child-reported harsh parenting and child externalizing behavior among boys and girls with higher or lower skin conductance level reactivity (SCLR) to the stress task.

Note. For boys, a raw score of 6 on externalizing problems = T score of 50; for girls, a raw score of 5 on externalizing problems = T score of 50.

Child-reported harsh parenting and SCLR-challenge task

As shown in Table 4, lower SCLR to the challenge task was independently associated with higher child externalizing behavior. This main effect was qualified by a two-way interaction between child-reported harsh parenting and SCLR-challenge task. Follow-up analyses revealed that child-reported harsh parenting was significantly associated with externalizing behavior among children with lower SCLR-challenge task, B = .16, SE = .07, p < .05, but not among children with higher SCLR-challenge task, B = .01, SE = .08, ns (see Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Associations between child-reported harsh parenting and child externalizing behavior among boys and girls with higher or lower skin conductance level reactivity (SCLR) to the challenge task.

Note. For boys, a raw score of 6 on externalizing problems = T score of 50; for girls, a raw score of 5 on externalizing problems = T score of 50.

Discussion

The present study is the first, to our knowledge, to examine electrodermal reactivity (i.e., SCLR) as a moderator of the association between harsh parenting and child externalizing behavior. Analyses revealed support for the moderation hypothesis. Specifically, the association between harsh parenting and child externalizing behavior was stronger among children who exhibited lower SCLR, as compared to children who exhibited higher SCLR. One three-way interaction also emerged, suggesting that lower SCLR may be a more robust vulnerability factor among boys, as compared to girls. Hypotheses were tested using a relatively large and diverse, community-based sample, controlling for marital conflict, child-reported internalizing symptoms, and demographic variables. Moderation findings were consistent across child and parent reports of harsh parenting, and across laboratory tasks designed to be stressful and challenging. Findings of the present study advance the existing literature, providing evidence that individual differences in physiological reactivity, as indexed through SCLR, can function as a vulnerability factor in the association between harsh parenting and child externalizing behavior.

Lower SCLR was associated with child externalizing behavior, independent of marital conflict and harsh parenting, and also operated as a vulnerability factor for child externalizing behavior. That is, the association between harsh parenting and child externalizing behavior was stronger among children who exhibited lower SCLR, as compared to children who exhibited higher SCLR. Among boys, this pattern held across different informants of harsh parenting and across physiological reactivity in response to different laboratory tasks. The moderation pattern was also evident among girls in all but one case. Specifically, among girls, the association between parent-reported harsh parenting and externalizing behavior was not different at higher or lower levels of SCLR to the stress task.

Several investigators have conducted related research on interactions between other forms of family stress and SCLR as predictors of child externalizing behavior. For example, Shannon et al. (2007) reported that higher electrodermal reactivity conferred partial protection against conduct problems in the context of paternal antisocial behavior; children with lower electrodermal reactivity exhibited higher conduct problems at all levels of paternal antisocial behavior. Cummings et al. (2007) found that higher SCLR operated as a vulnerability factor for externalizing problems in the context of parental depressive symptoms for girls and boys. In a cross-sectional study, El-Sheikh (2005) found a stronger association between marital conflict and externalizing behavior among girls with higher SCLR as compared to girls with lower SCLR. In longitudinal analyses of the same sample, El-Sheikh et al. (2007) reported that SCLR interacted with marital conflict and child sex to predict increased externalizing behavior 2 years later. Specifically, marital conflict predicted increased externalizing problems among boys with lower SCLR (but not higher SCLR) and among girls with lower or higher SCLR.

The existence and direction of sex differences vary across these studies. Whereas some evidence has emerged for lower SCLR as a vulnerability factor in the context of marital conflict (El-Sheikh et al., 2007) and harsh parenting (the present study) among boys, the evidence is not consistent among girls. Potential explanations for the apparent sex difference include a higher prevalence of underaroused externalizing behavior among boys compared to girls (Marsee, Silverthorn, & Frick, 2005) or other sex differences in the types of externalizing behaviors most often exhibited by girls versus boys (Crick & Grotpeter, 1995). The moderating role of SCLR may also depend on the type of family stress exposure (e.g., parental depression, marital conflict, harsh parenting, paternal antisocial behavior). In addition, statistical control of internalizing symptoms in the present study may contribute to different findings for girls compared to other studies examining other types of family stress. Clearly, further research is needed to explicate sex differences in the moderating role of SCLR.

Low electrodermal reactivity and related measures of diminished SNS response to stress have been conceptualized as markers of fearlessness, failure of avoidance learning, or punishment insensitivity (Fowles et al., 2000; Matthys et al., 2004; Raine, 2002). Thus, a potential explanation for findings of the present study involves children’s responsiveness to harsh parental behavior. Parents’ attempts to socialize low-SCLR children through harsh punishment may be especially ineffective or counterproductive due to these children’s underarousal in the face of aversive circumstances. That is, children who exhibit lower electrodermal reactivity may not associate harsh parental responses to their misbehavior with negative physiological arousal or corresponding psychological distress; thus, such parenting strategies may not serve the intended purpose of reducing the likelihood that the misbehavior will occur again. Furthermore, underaroused (i.e., less fearful) children may be more likely to respond to harsh discipline with aggression and thereby trigger coercive parent–child exchanges associated with antisocial behavior (Dadds & Salmon, 2003; Patterson, 2002). Underaroused children, whose attention is unimpeded by high arousal, may also experience optimal physiological conditions for learning coercive and aggressive behaviors from their parents in the context of harsh discipline (Hoffman, 1983, 1994). The implications of underarousal for children’s subjective experience of harsh punishment and ability to learn from harsh punishment might help explain the development, maintenance, or intensification of conduct problems among children with psychopathic or callous-unemotional traits (Dadds & Salmon, 2003; Frick & Morris, 2004; Frick et al., 2003; Raine, 2002). It is important to emphasize that the present study did not test both physiological and psychological responses to harsh parenting; rather, results suggest that it would be informative for future research to do so.

Among children who exhibited higher electrodermal reactivity, the association between harsh parenting and child externalizing was attenuated, yet significant, when parent reports of harsh parenting were considered, but nonsignificant when child reports of harsh parenting were considered. Given that common informant variance may have inflated the association between parent-reported harsh parenting and child externalizing behavior, results of the present study provide only limited evidence that harsh parenting and child externalizing behavior are associated among children with higher electrodermal reactivity. On the one hand, negative features of harsh parenting, such as social learning and negative reinforcement of aggressive behavior (Patterson, 2002) as well as failure to foster moral internalization or concern for the victim of hurtful behavior (Hoffman, 1983; Kerr et al., 2004; Kochanska, 1993), would be expected to promote externalizing behavior among children with higher (and lower) SNS responses. However, such aggressogenic mechanisms may be partially counterbalanced by the tendency of SNS-sensitive children to associate their externalizing behavior unequivocally with aversive responses from their parents. Thus, harsh parenting may not result in increased conduct problems at home among children with higher electrodermal reactivity (to the same degree as among children with lower electrodermal reactivity). Nonetheless, harsh parenting may contribute to cross-context externalizing behavior, such as disruptive behavior at school, where children may not link externalizing behavior with the same degree of aversive consequences as they do at home. Hoffman (1983) suggested that children who fear power-assertive parental responses may comply with their parents at home but direct their anger toward less powerful figures outside of the home. Furthermore, harsh parenting can disrupt parent–child relationships and may thereby contribute to internalizing or other adjustment problems among children with higher or lower electrodermal reactivity (Gershoff, 2002).

As noted, prior research has also shown that certain temperamental characteristics moderate the association between harsh parenting and child externalizing behavior (Bates & Pettit, 2007). In addition, ethnicity and ethnic-related differences in the practice or interpretation of harsh punishment may moderate the relation between harsh parenting and child externalizing behavior (Lansford et al., 2004, 2005). Thus, whereas research has consistently linked harsh parenting with externalizing problems, studies suggest that the magnitude of the association varies based on individual and environmental characteristics. From a developmental psychopathology perspective, harsh parenting may represent a nonspecific environmental risk factor that is associated with different outcomes in different settings depending on individual characteristics, such as gender and autonomic arousal (Steinberg & Avenevoli, 2000).

If replicated and corroborated by more rigorous designs (e.g., longitudinal), results of the present study would have important implications for behavior management interventions. Contemporary behavior management programs for parents are moderately effective (McCart, Priester, Davies, & Azen, 2006), but room for improvement exists, such as in the domain of parental involvement and engagement (Dumas, Nissley-Tsiopinis, & Moreland, 2007). One challenge can be parental receptivity to cautions against harsh discipline. For example, it is not uncommon for parents to inform clinicians that their own parents’ harsh discipline corrected their conduct problems during childhood. Results of the present study suggest that differences between parents’ and their children’s physiological reactivity could explain differences between parents’ and their children’s behavioral responses to harsh discipline. That is, some children appear to be relatively insensitive to the punishing aspects of harsh discipline and also well suited physiologically to observe and potentially learn aggressive behavior from harsh parental behavior. Although their hypothesis is largely speculative, Dadds and Salmon (2003) suggested that punishment-insensitive children may be relatively less responsive even to appropriate discipline, such as time-out. Avoiding escalating cycles of punishment may be especially critical for these children, and close bonds and positive reinforcement are indispensable (Dadds & Salmon, 2003). A better understanding of factors that moderate children’s responses to various forms of parental discipline would certainly benefit prevention programs and behavior management interventions.

These findings and their interpretation must be considered in the context of several limitations of the present study. First, the amount of variance explained by interactions was relatively small, and findings must be interpreted accordingly. In addition, the consistency of findings across analyses must be interpreted with some caution because predictor variables used in separate analyses were correlated, increasing the likelihood of replication. We did not create cross-informant or cross-task composite scores for predictor variables because we wished to eliminate common informant bias in some analyses, account for both child and parent perspectives on harsh parenting, and represent physiological responses to stress as comprehensively as possible. In addition, we did not include child- and parent-reported harsh parenting variables in the same analysis because our aim was to determine whether the moderating role of SCLR was robust across informants of harsh parenting, without eliminating the meaningful shared variance between child and parent reports.

Second, the cross-sectional design precludes conclusions about directionality and causality. The extensive body of research linking harsh punishment with externalizing behavior lends support to our suggestion that harsh parenting can contribute to externalizing behavior. However, we acknowledge that this relation is likely reciprocal, and longitudinal and experimental research is needed to provide more rigorous support for the specific hypotheses of the present study. It is also important to note an alternative interpretation of our findings: The association between SCLR and child externalizing behavior is moderated by harsh parenting. We also note that parenting and other family factors may influence SCLR, especially earlier in development, until a point in childhood at which SCLR may become relatively stable and operate more like a moderator of family influences than a mediator (El-Sheikh, 2007).

A third limitation is that general child externalizing behaviors were measured by parent reports. It will be informative for future research to distinguish proactive and reactive forms of aggression as outcomes, given possible differences in their physiological correlates. It also will be important for future research to establish whether findings generalize to externalizing behavior in the school setting and to consider outcomes such as internalizing symptoms and peer relationships. In addition, although we have provided evidence for sex and physiological reactivity as moderators, a number of additional variables may moderate the association between harsh parenting and child externalizing behavior, including characteristics of the parents (e.g., goals), child (e.g., age), and their relationship (e.g., warmth; Gershoff, 2002).

SCLR to stressful or challenging laboratory tasks constitutes a moderately stable individual difference and has been validated extensively as a physiological marker of stress response across contexts (El-Sheikh, 2007). As such, SCLR likely reflects physiological responses to harsh parenting, as conceptualized in the present study, but SCLR was not measured directly in the context of harsh parenting. Examination of SCLR under naturalistic conditions, such as during interactions with parents, would be informative and would lend further credibility to the mechanisms we have discussed. Of note is that the pattern of moderation was consistent across the socioemotional stress and problem-solving challenge tasks in the present study. Future research is needed to examine stress responses to multiple tasks to clarify the qualities of tasks that elicit certain responses and the meaning of those responses.

Finally, although the full range of externalizing problems was represented in our study, most children were within the normal range. Findings should generalize to many children in the community but will not necessarily generalize to children with clinical levels of externalizing problems. It is especially important for future research to investigate the developmental course of externalizing problems as they relate to family stressors and child physiological responses and to determine how interactions between these environmental and individual factors contribute to transitions from nonclinical to clinical status (Beauchaine et al., 2007). In addition, findings may not generalize to children living in family arrangements other than the two-parent type of family included in the present study (e.g., single-parent families).

Despite these limitations, the present study sheds new light on the association between harsh parenting and child externalizing behavior. Evidence emerged for independent associations linking both harsh parenting and lower SCLR with child externalizing behavior, and SCLR consistently moderated the association between harsh parenting and child externalizing behavior. Children with lower electrodermal reactivity may be at greater risk for externalizing problems in the context of harsh parenting. Findings corroborate the importance of psychobiological approaches that examine interactions between family risk and physiological vulnerabilities to understand the development of psychopathology in children.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant RO1-HD046795 to the second and third authors. We wish to thank participating families and the staff of the Child Development Laboratory for data collection.

Contributor Information

Stephen A. Erath, Auburn University

Mona El-Sheikh, Auburn University.

E. Mark Cummings, University of Notre Dame.

References

- Aber JL, Brown JL, Jones SL. Developmental trajectories toward violence in middle childhood: Course, demographic differences, and response to school-based intervention. Developmental Psychology. 2003;39:324–348. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.39.2.324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM. Integrative guide for the 1991 CBCL/4-18, YSR, and CBCL–TRF profiles. Burlington: University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Allen MT, Matthews KA. Hemodynamic responses to laboratory stressors in children and adolescents: The influences of age, race, and gender. Psychophysiology. 1997;34:329–339. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1997.tb02403.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allison PD. Missing data techniques for structural equation modeling. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2003;112:545–557. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.112.4.545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Social learning theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates JE, Pettit GS. Temperament, parenting, and socialization. In: Grusec JE, Hastings PD, editors. Handbook of socialization. New York: Guilford; 2007. pp. 153–177. [Google Scholar]

- Beauchaine TP. Vagal tone, development, and Gray’s motivational theory: Toward an integrated model of autonomic nervous system functioning in psychopathology. Development and Psychopathology. 2001;13:183–214. doi: 10.1017/s0954579401002012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beauchaine TP, Gatzke-Kopp L, Mead HK. Polyvagal theory and developmental psychopathology: Emotion dysregulation and conduct problems from preschool to adolescence. Biological Psychology. 2007;74:174–184. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2005.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boucsein W. Electrodermal activity. New York: Plenum; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Chang L, Schwartz D, Dodge KA, McBride-Chang C. Harsh parenting in relation to child emotion regulation and aggression. Journal of Family Psychology. 2003;17:598–606. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.17.4.598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen M. The monetary value of saving high-risk youth. Journal of Quantitative Criminology. 1998;14:5–30. [Google Scholar]

- Colder CR, Lochman JE, Wells KC. The moderating effects of children’s fear and activity level on relations between parenting practices and childhood symptomatology. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1997;25:251–263. doi: 10.1023/a:1025704217619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crick NR, Grotpeter JK. Relational aggression, gender, and social-psychological adjustment. Child Development. 1995;66:710–722. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1995.tb00900.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Ballard M, El-Sheikh M, Lake M. Resolution and children’s responses to inter-adult anger. Developmental Psychology. 1991;27:462–470. [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Davies PT. Children and marital conflict: The impact of family dispute and resolution. New York: Guilford; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, El-Sheikh M, Kouros CD, Keller PS. Children’s skin conductance reactivity as a mechanism of risk in the context of parental depressive symptoms. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2007;48:436–445. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01713.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dadds MR, Salmon K. Punishment insensitivity and parenting: Temperament and learning as interacting risks for antisocial behavior. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2003;6:69–86. doi: 10.1023/a:1023762009877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies PT, Harold GT, Goeke-Morey MC, Cummings EM. Child emotional security and interparental conflict. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 2002;67(3):1–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dearing E, Hamilton LC. Contemporary advances and classic advice for analyzing mediating and moderating variables. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 2006;71(3, Serial No. 285) [Google Scholar]

- Dumas JE, Nissley-Tsiopinis J, Moreland AD. From intent to enrollment, attendance, and participation in preventive parenting groups. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2007;16:1–26. [Google Scholar]

- El-Sheikh M. Parental drinking problems and children’s adjustment: Vagal regulation and emotional reactivity as pathways and moderators of risk. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2001;110:499–515. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.110.4.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Sheikh M. The role of emotional responses and physiological reactivity in the marital conflict-child functioning link. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2005;46:1191–1199. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.00418.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Sheikh M. Children’s skin conductance level and reactivity: Are these measures stable over time? Developmental Psychobiology. 2007;49:180–186. doi: 10.1002/dev.20171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Sheikh M, Harger J, Whitson SM. Exposure to interparental conflict and children’s adjustment and physical health: The moderating role of vagal tone. Child Development. 2001;72:1617–1636. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Sheikh M, Keller PS, Erath SA. Marital conflict and risk for child maladjustment over time: Skin conductance level reactivity as a vulnerability factor. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2007;35:715–727. doi: 10.1007/s10802-007-9127-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Sheikh M, Whitson SA. Longitudinal relations between marital conflict and child adjustment: Vagal regulation as a protective factor. Journal of Family Psychology. 2006;20:30–39. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.20.1.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster EM, Jones D the Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group. Can a costly intervention be cost-effective? An analysis of violence prevention. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2006;63:1284–1291. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.11.1284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowles DC. The three arousal model: Implications of Gray’s two-factor learning theory for heart rate, electrodermal activity, and psychopathy. Psychophysiology. 1980;17:87–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1980.tb00117.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowles DC, Kochanska G, Murray K. Electrodermal activity and temperament in preschool children. Psychophysiology. 2000;37:777–787. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frick PJ, Cornell AH, Bodin SD, Dane HA, Barry CT, Loney BR. Callous-unemotional traits and developmental pathways to severe conduct problems. Developmental Psychology. 2003;39:246–260. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.39.2.246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frick PJ, Morris AS. Temperament and developmental pathways to conduct problems. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2004;33:54–68. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3301_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gershoff ET. Corporal punishment by parents and associated child behaviors and experiences: A meta-analytic and theoretical review. Psychological Bulletin. 2002;128:539–579. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.128.4.539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goeke-Morey MC, Cummings EM, Harold GT, Shelton KH. Categories and continua of destructive and constructive marital conflict tactics from the perspective of U.S. and Welsh children. Journal of Family Psychology. 2003;17:327–338. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.17.3.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray JA. The psychology of fear and stress. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Hinden BR, Compas BE, Howell DC, Achenbach TM. Covariation of the anxious-depressed syndrome during adolescence: Separating fact from artifact. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1997;65:6–14. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.1.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman ML. Affective and cognitive processes in moral internalization. In: Higgins ET, Ruble DN, Hartup WW, editors. Social cognition and social development: A sociocultural perspective. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1983. pp. 236–274. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman ML. Discipline and internalization. Developmental Psychology. 1994;30:26–28. [Google Scholar]

- Hollingshead AB. Four factor index of social status. Unpublished manuscript 1975 [Google Scholar]

- Keiley MK, Lofthouse M, Bates JE, Dodge KA, Pettit GS. Differential risks of covarying and pure components in mother and teacher reports of externalizing and internalizing behavior across ages 5 to 14. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2003;31:267–283. doi: 10.1023/a:1023277413027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr DCR, Lopez NL, Olson SL, Sameroff AJ. Parental discipline and externalizing behavior problems in early childhood: The roles of moral regulation and child gender. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2004;32:369–383. doi: 10.1023/b:jacp.0000030291.72775.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochanska G. Toward a synthesis of parental socialization and child development in early development of conscience. Child Development. 1993;64:325–347. [Google Scholar]

- Kochanska G. Multiple pathways to conscience for children with different temperaments: From toddler-hood to age 5. Developmental Psychology. 1997;33:228–240. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.33.2.228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M. The Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI) Psychopharmacological Bulletin. 1985;21:995–998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachar D, Gruber CP. Personality Inventory for Children. 2. Los Angeles, CA: Western Psychological Services; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Lachar D, Wingenfeld SA, Kline RB, Gruber CP. Student behavior survey manual. Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Lansford JE, Chang L, Dodge KA, Malone PS, Oburu P, Palmerus K, et al. Physical discipline and children’s adjustment: Cultural normativeness as a moderator. Child Development. 2005;76:1234–1246. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2005.00847.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lansford JE, Deater-Deckard K, Dodge KA, Bates JE, Pettit GS. Ethnic differences in the link between physical discipline and later adolescent externalizing behaviors. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2004;45:801–812. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00273.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loeber R, Green SM, Lahey BB. Mental health professionals’ perception of the utility of children, mothers, and teachers as informants on childhood psychopathology. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1990;19:136–143. [Google Scholar]

- Marsee MA, Silverthorn P, Frick PJ. The association of psychopathic traits with aggression and delinquency in non-referred boys and girls. Behavioral Sciences and the Law. 2005;23:803–817. doi: 10.1002/bsl.662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthys W, van Goozen SHM, Snoek H, van Engeland H. Response preservation and sensitivity to reward and punishment in boys with oppositional defiant disorder. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2004;13:362–364. doi: 10.1007/s00787-004-0395-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCart MR, Priester PE, Davies WH, Azen R. Differential effectiveness of behavioral parent-training and cognitive behavioral therapy for antisocial youth: A meta-analysis. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2006;34:527–543. doi: 10.1007/s10802-006-9031-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris AS, Silk JS, Steinberg L, Sessa FM, Avenevoli S, Essex MJ. Temperamental vulnerability and negative parenting as interacting predictors of child adjustment. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2002;64:461–471. [Google Scholar]

- Paterson G, Sanson A. The association of behavioural adjustment to temperament, parenting and family characteristics among 5-year-old children. Social Development. 1999;8:293–309. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR. The early development of coercive family processes. In: Reid JB, Patterson GR, Snyder J, editors. Antisocial behavior in children and adolescents: A developmental analysis and model for intervention. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2002. pp. 25–44. [Google Scholar]

- Pettit GS, Arsiwalla DD. Commentary on special section on “bidirectional parent–child relationships”: The continuing evolution of dynamic, transactional models of parenting and youth behavior problems. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2008;36:711–718. doi: 10.1007/s10802-008-9242-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porges SW. The polyvagal perspective. Biological Psychology. 2007;74:116–143. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2006.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prinzie P, Onghena P, Hellinckx W, Griettens H, Ghesquiere P, Coplin H. The additive and interactive effects of parenting and children’s personality on externalizing behaviour. European Journal of Personality. 2003;17:95–117. [Google Scholar]

- Raine A. Biosocial studies of antisocial and violent behavior in children and adults: A review. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2002;30:311–326. doi: 10.1023/a:1015754122318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds CR, Richmond BO. Factor structure and content validity of “What I Think and Feel”: The Revised Children’s Manifest Anxiety Scale. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1979;43:281–283. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4303_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon KE, Beauchaine TP, Brenner SL, Neuhaus E, Gatzke-Kopp L. Familial and temperamental predictors of resilience in children at risk for conduct disorder and depression. Development and Psychopathology. 2007;19:701–727. doi: 10.1017/S0954579407000351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L, Avenevoli S. The role of context in the development of psychopathology: A conceptual framework and some speculative propositions. Child Development. 2000;71:66–74. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA. Child-report, adult-recall, and sibling versions of the Revised Conflict Tactics Scale. Durham, NC: Family Research Laboratory; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Hamby SL, Boney-McCoy S, Sugarman DB. The revised Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS-2): Development and preliminary psychometric data. Journal of Family Issues. 1996;17(3):283–316. [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Stewart JH. Corporal punishment by American parents: National data on prevalence, chronicity, severity, and duration, in relation to child and family characteristics. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 1999;2:55–70. doi: 10.1023/a:1021891529770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. United States Census 2005. 2005 Retrieved March 2, 2009, from http://www.census.gov/

- Wirt RD, Lachar D, Klinedinst JK, Seat PD. Multidimensional description of child personality: A manual for the Personality Inventory of Children. Los Angeles, CA: Western Psychological Services; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Yodanis CL, Hill KA, Straus MA. Tabular summaries of methodological characteristics of research using the Conflict Tactics Scale. Durham, NC: Family Research Laboratory; 2001. [Google Scholar]