Abstract

The significantly low rate of HIV infection and high rate of condom use among sex workers in Kolkata, India is partially attributable to a community-led structural intervention called the Sonagachi Project which mobilizes sex workers to engage in HIV education, formation of community-based organizations and advocacy around sex work issues. This research examines how Sonagachi Project participants mobilize collective identity and the manner in which collective identity influences condom use. Using purposive sampling methods, 46 Sonagachi Project participants were selected in 2005 for in-depth qualitative interviews. Taylor and Whittier’s (Taylor, V & Whittier, N (1992). Collective identities in social movement communities: lesbian feminist mobilization. In A. Morris & C. Mueller (Eds.) Frontiers in social movement theory. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press) model of identity-formation through boundaries, consciousness and negotiation was used to interpret results. Subjects mobilized collective identity by (1) building boundaries demarcating in-group sex workers from out-group members, (2) raising consciousness about sex work as legitimate labor and the transformative change that results from program participation, and (3) negotiating identity with out-group members. This research establishes a conceptual link between the boundaries, consciousness and negotiation framework of collective identity mobilization and condom use. Condom use among sex workers is motivated by each element of the boundaries, consciousness and negotiation model: condoms mark boundaries, enunciate the consciousness that sex with clients is legitimate labor, and help negotiate the identity of sex workers in interactions with clients.

Keywords: India; Community empowerment; Sex work; HIV; Women; Intervention, Condom use, Identity

Introduction

While HIV prevalence among sex workers in Indian cities like Bombay, Delhi and Chennai ranges from 50% to 90% (see Basu et al., 2004), seroprevalence among sex workers in Kolkata is 11% (UNAIDS, 2002). Reported condom use among sex workers in Kolkata rose from 3% in 1992 to 90% in 1999 (NACO, 1999, 2001). Scholars have argued that a peer-led intervention called the Sonagachi Project (SP) which utilizes sex workers engaging in HIV intervention efforts has played a significant role in changing attitudes among Sonagachi’s sex workers (Gangopadhyay et al., 2005) and reducing their sexual risk behavior (Basu et al., 2004; Jana & Singh, 1995).

Although scholars have emphasized the role of collective identity (CI) in the success of peer-led interventions like SP (Campbell & MacPhail, 2002; Latkin & Knowlton, 2005), few studies have sought to describe it, or explicitly link it to behavior change. Understanding the role of CI in empowering Sonagachi sex workers can fill several gaps in our knowledge. A lack of conceptual understanding of how the programs of SP and other peer-led interventions work limits the scope of efforts to replicate them. A conceptual framework that describes CI and the way it influences condom use can serve as a useful guide for replication efforts, especially in sites where differences in culture and context do not allow an easy or direct translation of the original intervention programs.

As a peer-led intervention seeking to change structural factors affecting HIV risk such as access to healthcare, the legal environment of sex work and societal perception of sex workers, SP has been described as a community-level structural intervention (CLSI) (Blankenship, Friedman, Dworkin, & Mantell, 2006). Evaluations of CLSIs have usually focused on individual-level outcomes and have largely ignored evaluating changes in the structures that they target (Blankenship et al., 2006). A conceptual definition of sex workers’ CI will facilitate efforts to measure and evaluate one of the key structural outcomes of a CLSI like SP that seeks to increase levels of community empowerment.

This research contributes to our understanding of the role of CI in HIV interventions by (1) describing how it is established by SP participants and (2) enunciating the conceptual link between CI and condom use.

Background

The Sonagachi project

SP began in 1992 as a peer-facilitated condom education program implemented by Durbar Mahila Samanwaya Committee (DMSC)1, a community organization run by sex workers. It now runs healthcare clinics providing services to 20,000 sex workers, a savings and banking co-operative that invests in community business enterprises, a dance–drama troupe that performs in public venues about sex worker issues, a support group for HIV positive sex workers, several schools for children of sex workers and a babu (long-term male clients) group that helps clients avoid being targeted by the police (Chakrabarty, 2004; Jana & Singh, 1995). Moreover, the intervention has been replicated in 49 sites all over West Bengal, India (Chakrabarty, 2004) and has been shown to increase condom use in replication sites (Basu et al., 2004).

Community empowerment and CI

Community empowerment has been described as the community gaining control of, and helping to solve, the problems confronting it (Rappaport, 1987). Portes (1998) identifies two broad domains of community resources that are targeted by community empowerment efforts: (1) the material resources and capital embedded in networks at the community level (see also Carpiano, 2006) and (2) the relational and social psychological resources available in social networks, community participation and social cohesion (see also Hawe & Shiell, 2000; Putnam, 1993). Scholars have identified these two resource domains as the two types of social capital that can potentially enrich a community (Bourdieu, 1986; Campbell & MacPhail, 2002; Carpiano, 2006). This paper focuses on community empowerment processes that target relational social capital. We argue that the relational, social-psychological and discursive processes that constitute this arm of empowerment can be described through the mobilization of CI. By studying the process of CI mobilization among sex workers in Sonagachi and linking it to condom use, we seek to construct a conceptual framework for a crucial aspect of community empowerment.

Theoretical framework

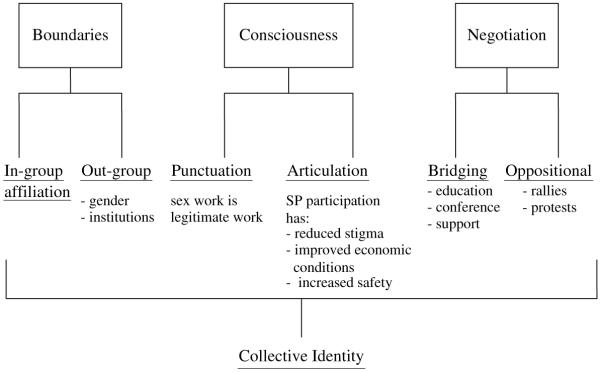

Given the established body of work on CI in social movement scholarship, we draw on the work of social movement theorists who argue that CI formation is a key aspect of community mobilization and collective action (Melucci, 1985; Snow & McAdam, 2000). Taylor and Whittier (1992) describe CI mobilization as (1) the formation of boundaries differentiating movement actors from outsiders, (2) the establishment of consciousness that infuses meaning into group identification, and (3) the negotiation of identity where it is made visible and politicized to the outside world. This paper builds on their framework of boundaries, consciousness and negotiation (BCN) to examine the mobilization of CI by SP participants (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

The BCN model.

While scholars have emphasized the importance of social identity in health-related behaviors (Campbell & Mac-Phail, 2002; Hawe & Shiell, 2000; Putnam, 1993), research has not traced the manner in which mobilization of this collective identity can influence health behaviors like condom use. We seek to address this theoretical gap by conceptually linking the BCN framework to condom use.

Methods

Sample

In-depth semi-structured interviews were conducted with 46 participants of SP. Since we were interested in distilling the elements of CI fostered by SP participation, purposive sampling was utilized to select key informants from the membership roster of Durbar who had been long-standing SP participants. Participants included 36 female sex workers and 10 non-sex worker Durbar staff members. Of the sex workers, two worked in Sonagachi, but didn’t live there, while the others lived and worked in brothels in Sonagachi. Institutional review board clearance was obtained from Durbar and the relevant U.S. universities.

Data collection and analysis

Interviews were audio recorded, conducted in Bengali by the authors, translated into English and transcribed for textual analysis. The QSR N6 software was used to analyze the data. The BCN model was used to set up an initial coding framework. Subsequent codes that expanded the model emerged from the data. Coding was done by the lead author and reviewed by the other authors. Codes and coded text were retained for analysis when there was agreement between the authors about them.

Results

The results indicate that the CI mobilized by SP participants can be described by a more detailed and enunciated form of the BCN framework, and that each process constituting the BCN model influences condom use.

The BCN framework

While Taylor and Whittier’s (1992) BCN framework was a useful starting point in the analysis of the data, emergent themes from the interviews necessitated adding conceptual detail to the framework in order to fully describe CI formation among SP participants.

Participants constructed boundaries through a simultaneous process of building in-group affiliation with other SP participants and inculcating a sense of opposition to institutions and societal processes outside the group that have victimized them as sex workers. The concepts of in-group affiliation and out-groups add contours to Taylor and Whittier’s (1992) notion of boundaries and illustrate how boundaries are erected by participants.

Consciousness was established through the development of two types of narratives: one which challenged dominant discourse by casting sex work as legitimate work, and a second which encouraged continued participation in SP by attributing transformative change to SP membership. We draw on Snow and Benford’s (1992) work on social movement frames to identify these two narratives as components of an interpretive schema: the first performs a punctuating function by emphasizing conditions of social injustice, while the second articulates a reason for membership. Punctuation and articulation add to Taylor and Whittier’s (1992) notion of consciousness by highlighting the discursive processes that are engaged in order to create meaning.

Negotiation of identity was accomplished through two processes: (1) bridging activities established links with outside members through education, performance and mobilization and (2) oppositional activities countered negative attitudes and oppressive action in hostile communities. By describing bridging and oppositional engagement, we anchor Taylor and Whittier’s (1992) concept of negotiation in processes that transmit identity to an outside audience.

We found that each of the processes described by the BCN framework influenced the use of condoms.

Boundaries

Taylor and Whittier (1992) note that boundaries emerge from affirming the structures and values of the group, while withdrawing from those of dominant society. SP participants illustrate this process through the formation of ingroup affiliations and the creation of out-groups.

In-group affiliation: SP participants express a strong sense of solidarity with fellow sex workers in general and with fellow SP participants, specifically. Invoking her body as the site of resistance where the politics of empowerment wage a constant battle, one participant says:

Usha2 is in my heart. I think of other Durbar programs as my body parts – as much a part of me as my hands and legs. They are simply inseparable from me.

Another participant defines the entire Indian sex worker community as a virtual reference group for herself. Expressing her belief in the importance of solidarity in such a group, she says:

One stick is feeble. Ten sticks together have immense strength and can fight back collectively. If the day comes, when all of India’s sex workers join Durbar, then all will benefit by it. We can demand the rights of the worker, but if I say this alone, then Parliament won’t listen to me.

Affirming her link to her mother’s community, the daughter of a sex worker and an SP participant says:

I’ve got proposals for marriage from traditional families but I told them that I would marry only if they accept me as a sex-worker’s daughter. I have ended up marrying the son of a sex worker.

Creating out-groups: Durbar members erect boundaries to delineate themselves from groups and institutions they feel victimized by.

Gender boundaries: Past experiences of being victimized by men have led many women in Durbar to define themselves as women exploited by men and male norms. Many SP participants expressed opposition to abusive husbands. Describing her plight after her family was unable to provide her husband with the dowry he demanded, one Durbar member denounces him, while pronouncing her empathy for other women sharing her situation:

I never got any love from my husband. He used to beat me regularly. I want no girl to get tortured like this.

Drawing on her outrage at an absent father who used to be one of her mother’s clients, the daughter of a sex worker and a Durbar member expresses her opposition to the male clients of her mother when she states:

Those who come to our mothers at night abuse them during the day. They get sex workers pregnant and then forget about the women and children.

Institutional boundaries: Durbar members express a strong sense of alienation from institutions that have mistreated them, constructing a boundary that casts these institutions as oppressive agents. One participant describes her experiences at a hospital that helped forge her boundaries against institutional healthcare:

I gave birth in Medical College Hospital. After a test, I was declared HIV positive. Afterwards, no one touched me. The nurses would throw the baby on my lap. The baby was kept in a separate room. The hospital authorities killed my baby.

Comparing hospitals outside the community to the SP clinic she works in, a Durbar member highlights the boundary marking the separation of in-group SP service provision and out-group institutional healthcare provision:

In our STI clinic, anybody can use the services but in government hospitals, receiving services is cumbersome. Doctors and nurses in government hospitals do not behave well with STI patients. We are much more involved in our Durbar clinic so we never behave like that. In our clinic there is no stigma.

SP participants feel alienated from educational institutions that discriminate against their children. Describing her unsuccessful attempt to enroll her son in a school, one worker recalls:

We couldn’t convince the teachers that my son was an appropriate student for their “good” school - all because of my profession. The teachers said to me, “You’re being naive – he won’t fit in. Have you seen anything of this world?” I replied, “Yes, I have seen many things. Whatever you have seen is from your tainted, stigmatized glasses, but I see without your glasses. I have a clearer vision of the world.”

As women, and specifically as sex workers, Durbar members feel alienated from religious institutions, which they believe actively repress their rights and choices. A Hindu woman describes the stigma that her religious institution heaps on sex workers, noting:

The temple people do not know we’re sex workers. That’s why we can go to the temples. I doubt they’d let us in if they knew that we are from the red-light areas.

Expressing her frustration with institutional Islam, a Durbar member marks a strong boundary against religion of all kinds:

Muslim society won’t change. Islam will not accept it (sex work). I have talked to many other (Muslim) women who feel that religion will do nothing for us. I am not a Hindu or Muslim or Buddhist or Christian any more.

Finally, an unsympathetic society is cast as the outside group, indicted for its lack of support:

I do not think people in my village have any right to talk about me and my profession. Society does not have any right to point its finger at me because when I was in trouble, society did not take care of me.

SP members thus erect two types of boundaries: (1) those that highlight and build affiliation with the in-group and (2) those that identify oppressive institutions and elements in the out-group, fomenting opposition to them. Boundaries constitute a key aspect of CI mobilization: they identify allies in the mobilization process, while simultaneously marking out elements in the environment that need to be mobilized against.

Consciousness

Taylor and Whittier (1992) note that movement actors establish consciousness by attaching meaning to their group affiliation and collective action. Describing this meaning-making process further, Snow and Benford (1992) note that social movement actors draw on collective action frames or meaning schema that (1) perform a punctuating role by “underscoring the injustice of a social situation” (1992:137) and (2) articulate a narrative that constitutes a liberating interpretive framework. While the punctuation function highlights conditions at the broader societal level, articulation often leads to narratives of personal life-histories that are embedded in a new critical consciousness. We draw on the concept of collective action frame to flesh out the consciousness-establishing processes in SP. The collective action frame developed by SP participants (1) performs a punctuating function by accenting the legitimacy of sex work as a profession, thus establishing a narrative of social justice and (2) articulates a narrative that credits SP with transformative change in their personal lives, thus encouraging continued participation in the collective.

Punctuation – creating a narrative of social justice: Examining women’s movements in Kolkata, Ray (1998) notes that they are heavily influenced by Marxist ideologies that have been historically salient in the region. Ray identifies this broader ideology influencing movements as the “master” frame or overarching interpretive schema that operates in Kolkata. SP draws on the Marxist master frame of compensated labor in formulating its collective action frame. It establishes the narrative that sex work is legitimate work, thereby taking issue with societal forces that stigmatize it and consign it beyond the boundaries of accepted wage-earning.

Postulating the central thesis of this frame, one sex worker states:

Why should what I do not be accepted? Through sex work, my children and I can eat, I can pay my house rent. If a lawyer’s, teacher’s or doctor’s job is considered good work then why not mine? This is also a job. I do my work and earn my bread. I am a worker.

An important part of the enterprise of establishing the narrative of sex work being valid labor involves targeting the discursive practices that sex work is embedded in. Many SP participants express their preference for the term “jouno kormi” or “sex-worker” rather than the derogatory terms used to refer to them. One Durbar member describes the manner in which she took issue with an audience member at a conference who used the derogatory term “potita” to refer to her:

I was furious. I told him, “I know more (insults) – khanki, barbonita, noti, potita, vyasya, randi. These names are given by you. I am a sex worker. I stay in Sonagachi. I survive because of my pesha (occupation). You don’t help me out, so you don’t have any right to call me by that name. We have a name for ourselves and it is ‘sex-worker’. So I order you to call me by that name.”

The discourse of respect that this collective action frame accentuates allows coalitions to be established with members of other stigmatized groups, while amplifying boundaries against groups and institutions that work towards exacerbating the stigma.

Illustrating this process, one SP participant finds common ground with a client who works in a funeral home, while simultaneously distancing herself from the caste-based religious institutions that designate him as an untouchable because of his profession:

We have no religious constraints anymore. If we are guided by what religion says about caste, then how will we earn and eat? We get cart pullers, rickshaw-pullers, sweepers, people who burn the dead, everyone. One day I ran into a client by the Ganges river. I said, “Hey, boka-choda (stupid-fucker)3, what are you doing here?” He said, “Don’t you know we burn the dead here?” I said, “Whatever – let’s get some tea together.” This man – he respects what I do, so I do the same for him. I don’t care what religion says about this. This friendship matters to me. He didn’t insult me.

The “sex work is work” narrative that emerges through punctuation is analogous to other broad movement frames like “Black is beautiful” and “Equal pay for equal work” in the Black Pride and Women’s Rights movements in the U.S. Creating a frame that casts sex work as legitimate work has several implications: (a) by resonating with Marxist Bengal’s master frame of fairly compensated labor, it lays the foundation for developing links with other labor organizations; (b) it de-stigmatizes sex work; (c) it identifies elements that work towards stigmatizing sex work as sources of oppression, and therefore targets of change; and (d) it identifies the solution as the process of establishing sex work as a means of labor.

Articulation – Building a narrative for mobilization:Snow and Benford (1992) note that in articulating an ideology, a collective action frame builds a cogent narrative that helps in retaining members and mobilizing them for action. SP members articulate a frame that attributes a profound transformation in their lives to their participation in Durbar. Whereas punctuation builds a narrative for sex workers as a generalized category, articulation highlights the benefits of membership in a real collective such as Durbar and engaging in a tangible intervention such as SP. While punctuation provides the ideological rationale for change and empowerment, articulation identifies the actual activity that leads to such transformation: continued participation and engagement in SP.

Specifically, the articulation of this frame credits Durbar with helping them to (1) establish economic independence, (2) combat stigma and (3) increase physical safety.

Establishing economic independence: SP participants credit their participation in Durbar with an upswing in their economic status – a powerful narrative of transformation that builds strong group affiliation, helps recruit new members and lays the groundwork for collective action on behalf of the program. SP participants describe the manner in which this transformation occurred:

In the past, we were controlled by our madams, pimps and landlords. We had to pay money to local parties and goons. Now after becoming DMSC members, we are more financially secure. Durbar workers now verify that madams do not take more than what is owed to them. Through Durbar we pool our money to be able to buy shops, property, save funds in the Usha Cooperative and take out loans. This is how Adhiya (indentured labor) has been eradicated. I could not arrange two square meals for the family before, now I can do that. My dress, my appearance, everything has changed after coming to Durbar

Given the conditions of poverty that many sex workers live in, crediting Durbar with facilitating economic improvement casts it as a successful agent of change in the lives of sex workers.

Combating stigma: Many SP participants recall the stigma that they were subjected to prior to their association with Durbar, and the manner in which Durbar helped them find a voice. Two Durbar members note:

Before Durbar, people used to look down on us. When we’d go to the local police station or the party earlier, we were shooed off. Now I discuss my experiences as a sex worker openly. Before becoming a Durbar member, I couldn’t tell anyone where I worked. I couldn’t talk about my real profession. But now I’m proud to tell people about my work. Even my husband and children know everything.

Increasing safety: Durbar members attribute a transformation in their ability to protect themselves to their participation in SP. Describing the process in which they learned to assert themselves in potentially adverse situations, participants note:

Earlier, I would not be able to go help a girl even if she was being beaten up [by the pimp] in my doorway. But after coming to Durbar I’ve changed. Where earlier we used to run away from the police, leave alone talk to them, now we demand their time. They no longer put the blame on us when we complain. They give us respect. Credit goes to Durbar. Previously the goons were very coercive. The policemen, the Panchayat4 members – they all exploited us. They would say, ‘Randi5 go away, we don’t have any place for you sex workers’. Whenever we went to lodge any complaint at the police station they shooed us away. Now, after joining Durbar, when we go to the police station, the barababu (head-officer) always offers us a seat, they talk to us, serve us tea. Even the Panchayat members talk to us. Previously (before Durbar) the customers used many abusive words. Now if they utter one word, we return ten to them. They can’t cope with us anymore.

Articulating the process of gaining independence from the same actors who were cast as oppressive outsiders in the boundary-building process infuses meaning into the categories created by boundaries. The acknowledgement that participation in Durbar has precipitated emancipation from oppression is best summed up by a member who proclaims:

Durbar has shown me the light. Thus far, I was in darkness. We can talk about our rights because of Durbar. We can share our difficulties and depression with each other because of Durbar. I can engage my babu on equal terms because of Durbar. I do not tolerate any torture because of Durbar.

This articulation that SP membership has led to a transformation in dealings with the outside world encourages members to stay engaged in the program and enables the intervention to sustain itself over time.

The collective action frame established through punctuation and articulation constitutes the consciousness-raising component of collective identity mobilization. Participants counter stigma, develop pride in being sex workers and inculcate belief in their agency. Critical consciousness is established by underlining the social justice issues surrounding sex work and attaching political significance to the in-group and out-group categories created in the boundary-making process.

Negotiation

Taylor and Whittier (1992) note that the process of negotiation entails the communication and politicization of identity and consciousness to actors outside the group. Two strands of the negotiation process emerged from our data: (1) a process of bridging whereby SP members communicated their identity to receptive outsiders and possible allies through education, performance and mobilization and (2) an oppositional negotiation whereby identity was negotiated among hostile outsiders.

Bridging: SP has actively communicated its sex worker identity to receptive audiences, thus increasing its pool of allies, a process we define as bridging. It has participated in several outreach efforts like educational campaigns about HIV and has collaborated on projects with governmental institutions as well as the police and local power brokers (Chakrabarty, 2004; Cornish & Ghosh, 2007).

Aware of the high premium placed on art, literature and performance in Bengali culture, SP has distributed literature at the Kolkata Book Fair, a major cultural event (Chakrabarty, 2004) and formed a sex workers’ dance drama troupe that performs in many public venues. In 1998 it performed at the opening ceremony of the International AIDS Conference held in Geneva, Switzerland (Chakrabarty, 2004). The authors attended a production by the troupe organized in conjunction with a major local bank that had recently started allowing sex workers to open bank accounts. The audience, comprising the families of bank employees as well as sex workers, watched plays that addressed the issues and barriers facing sex workers.

SP has successfully implemented the CLSI in several sex work communities in Bengal by inviting outside sex workers to visit Sonagachi and participate in an immersion program where they learned the tenets of the SP model. In addition, SP peers move out to target communities and work with community members to set up sex worker unions. Describing strategies to align with sex workers with similar issues, one member recalls:

We would tell sex workers in Khidderpore… “we are sex workers, like you. We want the best for you. If we die as a result of HIV, our families will suffer.” We would also tell them that it is to our benefit to go to the clinic, get a thorough check-up. In the end they heard us and we now have a program there.

Presently, 49 of these programs operating on the SP model have been set up all over the state of West Bengal. Durbar has also organized four national conferences, drawing together 30,000 sex workers from other parts of India (Chakrabarty, 2004). Members have attended conferences all over the world. Recalling her experience at one of these, one participant states:

I spoke for 20 minutes and people were absolutely stunned to hear that illiterate Indian sex workers are capable of doing such good work. A number of people came and hugged me afterwards.

SP negotiates its message by aligning with civic institutional functions, cultural practices and the sex work identities of outside sex work communities. Cornish and Ghosh (2007) note that building links with elites and power brokers in the greater political and social structure allows Durbar to gain credibility, politicize its identity to outside audiences, and expand its network of support.

Oppositional negotiation: Fighting stigma and structural oppression, Durbar members have routinely negotiated their identity in hostile settings. Whereas bridging builds allies, oppositional negotiation enables participants to engage with oppressive processes and elements. One member recalls:

The local goons used to milk us for money, threaten us. The land ladies were also a menace. The police would randomly arrest us and our customers. No one helped us. We fought against illegal eviction and police and pimp torture. We (forced the) police, the dalals (brokers) and the malkins (madams) who force women into this profession to listen.

Often, the negotiation entailed a physical defense of members, principles and ideology. Participants describe several occasions where SP members mobilized to engage with police, pimps, violent clients and other hostile actors:

We decided that if anyone beats us, we will fight back. Once, we armed ourselves with sticks and scared a pimp off when he came to beat one of us. Another time, someone beat up our care educator. We caughthim, took him to the police and had him arrested. A sex worker in Khidderpore was tortured by local boys…they burnt her vagina with cigarettes. We went there, set up a stand and protested over a mike continuously until we had them arrested.

Our previous organizational secretary was harassed in Tollygunge. We organized hunger strikes, held rallies, then gheraoed (surrounded) the police station and had those people arrested.

Oppositional negotiation engages several actors and institutions defined as out-group members through the boundary-demarcation process. In a dynamic dialectical process aimed at creating safety, a sex-worker’s body and the private as well as public spaces she occupies become sites of resistance. Any encroachment of these spaces is defended and presents an opportunity to deploy oppositional consciousness.

The process of negotiation is the third crucial element of CI mobilization. It transforms consciousness into collective action, which in turn, roots SP members deeper in the sex work collective identity. Negotiating is crucial in building capacity in the community. Bridging and oppositional negotiation have led to better relationships with the police, pimps and other local power brokers, resulted in the establishment of health clinics, access to banking services, the rapid spread of the program to other sites and increased the visibility of SP, catapulting it onto the national and international stage. While it is beyond the scope of this paper to examine all the factors that influence the process of building material capacity, the process of negotiation links CI to capacity building and ensures the sustainability of the CLSI.

BCN and condom use: conceptually linking CI to behavior change

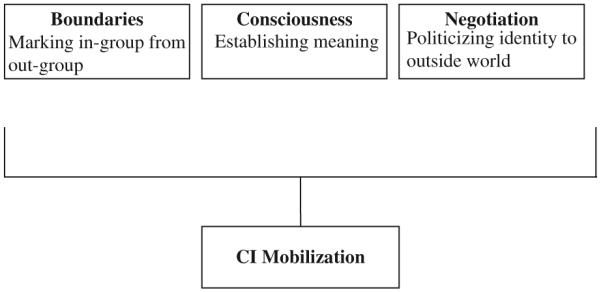

The BCN framework describes how SP members demarcate boundaries by (1) building affiliations with in-group members and constructing out-group boundaries along gender and institutional lines, (2) establishing consciousness through a collective action frame that interprets sex work as work and attributes personal transformation to SP participation and (3) negotiating their identity through bridging and oppositional engagement (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

The enunciated BCN framework.

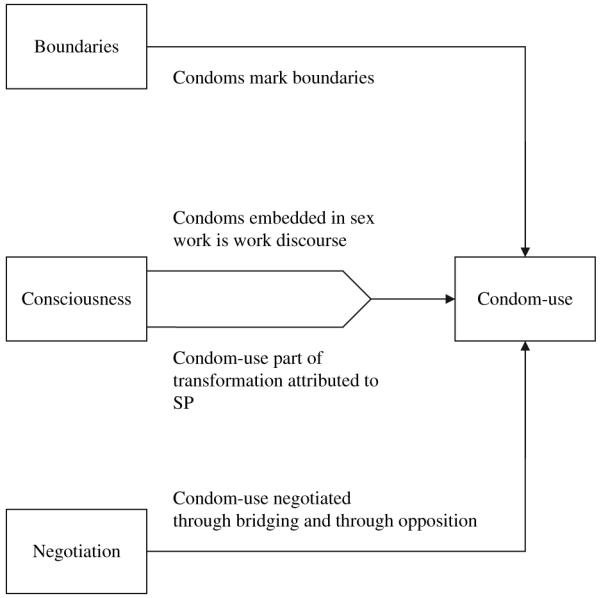

The question arises as to whether the BCN framework of CI can explain condom use among SP participants. Illustrating Campbell and MacPhail’s (2002) argument that condom use is “structured by social identities rather than individual decisions,” we demonstrate that condom use becomes a collective process, informed by each element of the BCN framework of CI (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Conceptually linking BCN to condom use.

The influence of boundaries: The use of condoms marks boundaries against men and non-SP sex workers. Regarding the latter’s reluctance to use condoms and attend health clinics, one participant says:

The general sex workers who don’t use condoms….- don’t take the disease seriously. They say, “Since I don’t have any disease, why should I go to the (Durbar) clinic?” We (SP members) aren’t like that….We know the dangers of HIV, the benefits of condoms. That’s the difference.

Other participants describe how they distance themselves from clients who do not use condoms:

Once, a customer took the condom off during sex. I was so angry, I slapped him and yelled at him so much that he never came back. Good riddance!

I kick them out if they don’t use a condom. Who do they think we are? We are not that stupid.

Gender boundaries are also evident in the way participants describe their wariness of long-term male clients whom they have set up house with and consider contextual husbands (Babus). Forged through adverse interactions with oppressive and sometimes violent men, their distrust of males informs their decision to use condoms, even with the closest men in their lives:

I am not sure whether my Babu is monogamous. Though he tells me he is, I cannot trust him absolutely. So in order to avoid infection, I use condoms. Using condoms (with my Babu) is a must. The mention of love upsets me. Men say that to get their way. When he said he loved me and wanted to be with me, I told him I would, only if he used a condom regularly. He’s accepted that.

Thus boundaries endure even against regular partners and facilitate condom use in long-term sexual relationships where regular use has been found to be generally low in other populations (Macaluso, Demand, Artz, & Hook, 2000).

The influence of consciousness – punctuation: The collective action frame casting sex work as labor results in Durbar members viewing condom use as a financial decision, as enunciated by a participant:

Those not using condoms, good bye to them. I say, “I am sorry, because if I am healthy, then I will get many other customers…if I get HIV, then that’s it.”

Condoms get inscribed into the work transaction and are transformed from health devices into integral tools of the sexual performance that form the backbone of the trade:

When the customer is erect and aroused, only then do I talk about condoms, otherwise there might be a chance of losing the clients.

Sometime we help clients in wearing them as well. Even if I have to educate him about why we must use condoms, I do so while I masturbate him. My hand keeps working while my mouth is talking.

Drawing on the “sex work is work” narrative and deploying their consciousness as professional workers, SP participants believe that they control clients’ physical responses in encounters that are sexually charged and characterized by consumption of alcohol. They note that this level of control allows them to negotiate condom use:

We don’t talk about condoms immediately. I have some maal (wine) with them. We talk a little and then I get him hard. Once he is sexually aroused, I bring out the condoms. He reaches such a state, drunk and erect that he is not able to refuse. I am very practical.

I encourage the customer if he wants to drink – I have better control then. Once he is aroused, I slip the condom on.

First I interact with the customer, share a few drinks, dance for him and then slowly arouse him by kissing him, masturbating him. When he is out of his mind with lust and drink, I ask him to put on a condom. This is strategy because when the customer gets excited, he is ready to do anything for sex.

The collective action frame that transforms condoms into performative and transactional devices can have startling results: whereas substance use and failure to negotiate condom use prior to engaging in the sexual encounter have often been identified as risk factors in other contexts, here they facilitate the worker’s negotiating power. One SP participant notes the collective manner in which these strategies are established:

We share strategies with each other. Those who prefer oral sex teach us ways to put on condoms with the mouth. By discussing our customers, we get to know new ways, new techniques to use condoms. I keep their words in mind.

Articulation: Participants’ discussion of condom use illustrates the elements of articulation whereby transformation in attitudes and behaviors regarding condoms is attributed to SP participation:

I learned to use condoms after joining Durbar. The knowledge that I’ve gained from Durbar, that HIV is a disease with no cure has given me the strength to insist on condoms.

I never liked using condoms before, even with customers who wanted to use them. I changed after I joined Durbar.

Condom use is thus influenced by the “sex work is work” narrative, as well as the articulation that Durbar participation has engendered transformative change in sex workers’ lives.

The influence of negotiation – bridging: Collective negotiation through bridging practices such as peer education and other educational activities have increased members’ knowledge about how to use a condom and the dangers of HIV infection. SP participants illustrate how they bring this knowledge to bear in their interactions with clients:

I cannot read, but since I’m a peer educator I know that if the condom is still oily, the expiration date hasn’t expired. I pass the air out of it and make him put it on. Afterwards, I take it off myself and dispose of it.

Using bridging tactics where they aligned with clients, participants amplified their common interests in protecting their families by safeguarding their health:

If they don’t want to use condoms, I tell them “you have your family and I too have mine. If I get infected today, then my children will suffer. And if I infect you, then your family will suffer. Why buy a disease from me for a few moments’ enjoyment?”

I might be good looking but that doesn’t mean I cannot transmit disease. You have a family, so if I infect you and you infect your wife, your family is ruined.

Oppositional negotiation: As in other strategies comprising oppositional negotiation, condom use is often negotiated with resistant clients, where the alignment tactics of bridging efforts are set aside for a more confrontational approach. Attributing her emboldened and uncompromising stance towards condom use to her repeated engagement in oppositional negotiation, one member states:

I’ve fought off the police and pimps in the past – so now if customers doesn’t use a cap, then I kick them out the door.

Another participant roots herself in the collective by using the pronoun “we” when describing oppositional negotiation of condom use:

When customers abuse us for wanting to use condoms, we abuse back. We have to talk in their language. They say “we’ll go elsewhere”, so we say “go! And take your money with you.”

Whereas bridging influences condom use by providing access to a repertoire of alignment tactics that build mutual agreement about using condoms, oppositional negotiation allows participants to refuse to have sex with resistant clients. Condom use is thus influenced by the negotiation processes described by the third component of the BCN framework.

Discussion

This is the first study to explore a theoretical framework that links CI mobilization to intervention outcomes. By applying Taylor and Whittier’s (1992) framework to CI formation in Sonagachi, we construct a useful analytical lens that can be used to enunciate CI mobilization and explain how CI influences condom use. The BCN framework has implications for our theoretical understanding of community empowerment interventions, and for their future implementation.

Theoretical implications

The BCN model sheds light on key analytical concepts that have emerged in previous research on CLSIs and peer-led public health interventions.

BCN, social capital and empowerment: Scholars have criticized Putnam’s (1993) concept of relational social capital for being imprecise in definition, hard to operationalize in public health research and lacking analytical utility (DeFilippis, 2001; Portes, 1998). Carpiano (2006) suggests that public health research is better served by focusing on the material resources embedded in social networks, rather than its relational aspects. This research responds to such criticism by arguing that CI mobilization, as described by the BCN framework, is an analytically useful way to conceptualize the strengthening of relational social capital leading to an increase in the relational aspect of community empowerment. It ties together aspects of relational social capital such as community-level cohesiveness, engagement and consciousness (Campbell & MacPhail, 2002; Hawe & Shiell, 2000; Putnam, 1993): CI mobilization builds strong ties, establishes critical consciousness, inculcates identity, encourages engagement in action and identifies pathways to change in a community. Just as building material capacity results in a cache of resources for a community, CI leads to the establishment of a symbolic, discursive and relational reservoir that increases community empowerment. Anchored in the framework of the BCN model, CI allows us to sift through the analytical complexity of relational social capital and identify the manner in which it is harnessed in order to boost empowerment.

BCN and condom use: This is the first study, as far as the authors know, that links CI to condom use. Scholars have criticized the scholarship on peer and community-led interventions as being atheoretical (Milburn, 1995; Turner & Shepherd, 1999). Campbell and MacPhail (2002) point out that scholars examining these interventions have often conducted quantitative community trials which evaluate their effectiveness without identifying why they work. Taking a similar approach, a previous study involving one of the authors of this paper, proved that SP can be successfully replicated programmatically in a neighboring sex work site without explaining how SP affects decisions to use condoms (Basu et al., 2004). This study answers the call to unpack the manner in which peer-education and community-led interventions like SP work by embedding it in an analytical framework that links collectivization to condom use.

Practice implications

By linking CI to condom use, this research highlights the need for HIV interventions to focus on CI mobilization. Community empowerment interventions might increase their effectiveness by highlighting the manner in which condoms mark targeted sex workers from outsiders, attaching positive meaning to using condoms as part of sex work, and emphasizing the role of condoms in negotiating sex work identities to outsiders.

The BCN framework is a conceptual blueprint that can guide CLSI efforts to mobilize CI, even when the exact programs of SP cannot be replicated due to contextual differences. This is highlighted by the case of Mumbai, where sex work collectivization is non-existent, despite the significant presence of NGOs engaged in ensuring the welfare of sex workers (Shah, 2003). While the discourse of sex work as legitimate labor plugs into the Marxist frame in Bengal (Ray, 1998; Snow & Benford, 1992), it might not translate as easily in Bombay. Ray (1998) notes that Bombay’s feminist organizations are influenced by a frame of protection against violence and differ from the Marxist ideology influencing Kolkata’s women’s organizations. The BCN framework suggests that efforts to collectivize in Bombay would need to develop a collective action frame that is resonant with community members. The BCN framework thus provides an analytical tool to identify differences in mobilizational contexts and examine why some interventions do not transfer across sites. It allows replication efforts of community-led interventions to shift the focus from a rigid (and at times untenable) implementation of programs to mobilizational processes described by the framework.

Research implications

The results highlight several pathways for future research. The BCN framework lays the foundation for the construction of a measurement tool to evaluate the CI component of community empowerment. Measurement of the baseline and the post-intervention levels of CI among community members allows for an evaluation of a key structural outcome of structural intervention like SP.

The results conceptually link CI to condom use, providing a theoretical rationale to hypothesize a causal association. Future research needs to test this association.

Finally, the BCN framework can be used as a conceptual guide for future ethnographic research examining collectivization processes in HIV interventions. As an analytical lens, it can be used to examine the potential for collectivization and implementation of community-led interventions as well as frame process evaluations of these interventions.

Study limitations

There are several limitations to the research. Since Taylor and Whittier’s (1992) framework was used as an organizing coding scheme, it is possible that it skewed the interpretation of the data. While an inductive method was subsequently utilized to identify patterns in the data and ultimately led to the expansion of the original BCN model, future research needs to test the robustness of the framework.

Given the small sample size, results cannot be generalized to a wider population. Rather, the purpose of this qualitative study is to build theory, highlighting conceptual definitions and linkages. Future research using a representative sample and quantitative methods needs to test the concepts described in this research.

Given the sensitive nature of the subject matter, social desirability may have influenced interviews. We attempted to limit this through the use of multiple interviewers of both genders.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Center for HIV Identification, Prevention and Treatment Services for funding this research, as well as Dr. Kim Blankenship, Dr. Jeannette Ickovics and the CIRA NIMH Fellows for providing valuable feedback. Above all, we would like to thank the incredible women and men of DMSC for participating in this research.

Footnotes

Also called Durbar, which means “unstoppable”.

An SP microfinancing collective.

Used as a friendly street greeting.

Local governmental body.

Derogatory term for prostitutes.

References

- Basu I, Jana S, Rotheram-Borus M, Swendeman D, Lee S, Newman P, et al. HIV prevention interventions among sex workers in India. JAIDS. 2004;36(3):845–852. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200407010-00012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blankenship K, Friedman S, Dworkin S, Mantell J. Structural Interventions: Concepts, challenges and opportunities for research. Journal of Urban Health. 2006;83(1):59–72. doi: 10.1007/s11524-005-9007-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu P. The forms of capital. In: Richardson JG, editor. Handbook of theory and research for the sociology of education. Greenwood; New York: 1986. pp. 241–258. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell C, MacPhail C. Peer education, gender and the development of critical consciousness: participatory HIV prevention by South African youth. Social Science & Medicine. 2002;55:331–345. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00289-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpiano R. Towards a neighborhood, resource-based theory of social capital for health: can Bourdieu and Sociology help? Social Science & Medicine. 2006;62:165–175. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakrabarty I. Influence of rights-based approach in achieving success in HIV program and in improving the life of sex workers. Durbar Mahila Samanwaya Committee Publication; Kolkata, India: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Cornish F, Ghosh R. The necessary contradictions of “community-led” health promotions: a case-study of HIV prevention in an Indian red-light district. Social Science & Medicine. 2007;64:496–507. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeFilippis J. The myth of social capital in community development. Housing Policy Debate. 2001;12:781–806. [Google Scholar]

- Gangopadhyay D, Chanda M, Sarkar K, Niyogi S, Chakraborty S, Saha M, et al. Evaluation, of sexually transmitted diseases/Human Immunodeficiency Virus intervention programs for sex workers in Kolkata, India. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2005;32:680–684. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000175399.43457.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawe P, Shiell A. Social capital and health promotion: a review. Social Science & Medicine. 2000;51:871–885. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00067-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jana S, Singh S. Beyond medical model of STD intervention – lessons from Sonagachi. Indian Journal of Public Health. 1995;39:125–131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latkin C, Knowlton A. Micro-social structural approaches to HIV prevention: a social-ecological perspective. AIDS Care. 2005;17:S102–S113. doi: 10.1080/09540120500121185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macaluso M, Demand M, Artz L, Hook E. Partner type and condom use. AIDS. 2000;14:537–546. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200003310-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melucci A. The symbolic challenge of contemporary movements. Social Research. 1985;52:781–861. [Google Scholar]

- Milburn K. A critical review of peer education with young people with special reference to sexual health. Health Education Research. 1995;10:407–410. doi: 10.1093/her/10.4.407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National AIDS Control Organization [NACO] Executive summary: female sex workers and their clients. 1999 Retrieved December 2006. Available from. http://naco.nic.in/vsnaco/indianscene/executive1.htm.

- National AIDS Control Organization (NACO) Combating HIV/AIDS in India, 2001-2001. 2001 Retrieved December 2006. Available from. http://naco.nic.in/vsnaco/indianscene/country.htm.

- Portes A. Social capital: its origins and applications in modern sociology. Annual Review of Sociology. 1998;24:1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam R. The prosperous community: social capital and public life. American Prospect. 1993;13:35–42. [Google Scholar]

- Rappaport J. Terms of empowerment/exemplars of prevention: toward a theory for community psychology. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1987;15:121–148. doi: 10.1007/BF00919275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray R. Women’s movements and political fields: a comparison of two Indian cities. Social Problems. 1998;45:21–36. [Google Scholar]

- Shah S. Sex work in the global economy. New Labor Forum. 2003;12(1):74–81. [Google Scholar]

- Snow D, Benford R. Master frames and cycles of protest. In: Morris A, Mueller C, editors. Frontiers in social movement theory. Yale University Press; New Haven, CT: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Snow D, McAdam D. Identity work processes in the context of social movements: clarifying the identity/movement nexus. In: Stryker Sheldon, Owens Timothy, White Robert., editors. Self, Identity, and social movements. U Minnesota Press; Minneapolis, MN: 2000. pp. 41–67. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor V, Whittier N. Collective identities in social movement communities: lesbian feminist mobilization. In: Morris A, Mueller C, editors. Frontiers in social movement theory. Yale University Press; New Haven, CT: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Turner G, Shepherd G. A method in search of a theory: peer education and health promotion. Health Education Research. 1999;14:235–247. doi: 10.1093/her/14.2.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNAIDS Epidemiological fact sheets on HIV/AIDS and sexually transmitted infections: India. 2002 2002 fact-sheet. Retrieved December 2006. Available from. http://www.unaids.org/hivaidsinfo/statistics/fact_sheets/pdfs/India_en.pdf.