Abstract

We previously found that chronic alcohol consumption decreases the survival of mice bearing subcutaneous B16BL6 melanoma. The underlying mechanism is still not completely understood. Antitumor T cell immune responses are important to inhibiting tumor progression and extending survival. Therefore, we examined the effects of chronic alcohol consumption on the functionality and regulation of these cells in C57BL/6 mice that chronically consumed 20% (w/v) alcohol and subsequently were inoculated subcutaneously with B16BL6 melanoma cells. Chronic alcohol consumption inhibited melanoma-induced memory T cell expansion and accelerated the decay of interferon (IFN)-γ producing T cells in the tumor-bearing mice. Foxp3+CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells were not affected; however, the percentage of myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSC) was significantly increased in the peripheral blood and spleen. T cell proliferation as determined by carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester labeling experiments in vitro was inhibited by alcohol consumption relative to control water-drinking melanoma-bearing mice. Collectively, these data show that chronic alcohol consumption inhibits proliferation of memory T cells, accelerates the decay of IFN-γ producing CD8+ T cells, and increases MDSC, all of which could be associated with melanoma progression and reduced survival.

Keywords: Alcohol consumption, MDSC, Melanoma, Memory T cells, Interferon gamma

Introduction

Many dietary and nutritional factors modulate the immune response, both positively and negatively. Alcohol consumption is a dietary component, which when abused is generally immunosuppressive. A causative agent for cancers of the mouth, pharynx and larynx, esophagus, colorectum (men), and breast, alcohol consumption is also emerging as a risk factor for several other types of cancer [1]. Alcohol consumption is associated with enhanced metastasis of colorectal carcinoma to the liver [19] and with decreased survival of lung cancer patients [26]. Survival also is decreased in mice bearing subcutaneous melanoma tumors and consuming high levels of alcohol (20% w/v) [3]. The underlying factors leading to decreased survival in these melanoma-bearing mice are not completely known.

Melanoma cancers are immunogenic and the host immune system plays an important role in controlling tumor growth and metastasis [4, 18]. Results from clinical tumor immunotherapy trials indicate that the number and function of tumor-specific CD8+ T cells are critical to the survival of melanoma patients [32]. Tumors can produce multiple factors that induce specific cell populations that inhibit antitumor immune functions [5, 37]. At least three types of cells, Foxp3+CD4+CD25+ regulatory T (Treg) cells, Mac-1+Gr-1+ myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSC), and tumor associated macrophages (TAM) have been identified as key players that inhibit host antitumor immune activity by suppressing T cell proliferation, cytolytic activity and cytokine production [6, 8, 20, 23].

Previously, we showed in mice not inoculated with melanoma that chronic alcohol consumption decreased the overall number of T cells and that this induced T cell homeostatic proliferation of non-antigen-specific T cells expressing the memory phenotype [42]. However, the total numbers of T cells never return to normal levels. Melanoma induces the proliferation of tumor-specific memory T cells. These cells are important to the control of tumor progression and survival in melanoma patients [31, 41]. Because chronic alcohol consumption decreased T cell numbers in the absence of tumor, we examined the hypothesis that this would impact the generation of antigen-specific memory T cells. We found that alcohol consumption inhibited melanoma-specific CD8+ T cell expansion, and in addition accelerated loss of interferon (IFN)-γ producing T cells, and increased immunosuppressive MDSC.

Materials and methods

Animals and alcohol administration

Animal use and alcohol administration followed previously established procedures [43]. Briefly, female C57BL/6 mice at the age of 6–7 weeks were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, DE). After arrival the mice were single housed in plastic, filter toped cages in the Wegner Hall Vivarium at Washington State University according to the Principles of laboratory animal care (NIH publication No. 85023 revised 1985). The vivarium is accredited by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care and the animal protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. One week after arrival, the mice were randomly divided into two groups. One group of mice continued to drink water and the other was given 20% (w/v) of alcohol as the sole drinking source throughout the experimental period.

Tumor cell culture and inoculation

B16BL6 melanoma cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium supplemented with 10% of fetal bovine serum (FBS, Equitech-Bio Inc., Kerrville, TX). Cells at 50–70% confluence were harvested and resuspended in calcium-free, magnesium-free phosphate buffered saline (PBS) to a final concentration of 106 cells/ml. After 3–6 months of consuming alcohol, mice were injected subcutaneously with 2 × 105 cells into the right hip. They were euthanized at the indicated time points. Experiments were replicated as indicated in the figure legends. Similar results were obtained in mice consuming alcohol for 3–6 months before melanoma inoculation.

Flow cytometry and specific antibodies

The cellular phenotype and expression of melanoma-specific CD8+ T cells, FoxP3+ Treg cells, and IFN-γ producing CD8+ T cells were analyzed by flow cytometry following previously established procedures [42]. The following fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC), phycoerythrin (PE), peridinin chlorophyll protein (PerCP)-Cy5.5, or PE-Cy5.5 labeled anti-mouse antibodies were used. Anti-CD11b (M1/70), anti-Ly6C (AL-21), anti-CD4 (L3T4), anti-CD8 (53-6.7), anti-CD44 (IM7), anti-CD25 (PC-61), anti-CD124-PE (mIL-4R-M1), and anti-IFNγ (XMG1.2) were purchased from BD Biosciences Pharmingen (San Diego, CA). Anti-NK1.1 (PK136), anti-CD3 (145-2C11), anti-FoxP3 (MF-14), Anti-F4/80, anti-Gr-1 (RB6-8C5) were purchased from BioLegend (San Diego, CA).

Leukocyte isolation from blood

Peripheral blood leukocytes (PBL) were isolated with Lympholyte-M (Cedarlane Laboratories Limited, Burlington, NC) as described previously [42]. An appropriate number of isolated cells were suspended in PBS +0.1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) for further use.

Splenocyte isolation

Whole spleens were used to isolate lymphocytes using previously established procedures [42]. Total cell number and viability were determined with the Cell Viability Analyzer (Vi-Cell, Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA). Cells were resuspended in an appropriate volume of PBS + 0.1% BSA for further use.

Tumor infiltrating lymphocyte isolation

Tumors from mice were isolated and washed with ice-cold PBS + 0.1% BSA, passed through a wire mesh screen into ice-cold PBS + 0.1% BSA, and then centrifuged at 4°C for 10 min at 800×g. The cells were resuspended into 5 ml of warm PBS + 0.1% BSA and layered onto 5 ml of warm Lympholyte-M in a 15 ml tube. The tube was centrifuged at room temperature for 20 min at 800×g. The tumor infiltrating lymphocyte (TIL) at the interface were collected, counted and resuspended in appropriate amount of PBS + 0.1% BSA for further use.

Analysis of melanoma-specific CD8+ T cells

Melanoma-specific CD8+ T cells were determined by flow cytometry with PE-labeled T3700 tetramer and PE-Cy5-labeled CD8 anti-mouse monoclonal antibody. The H-2Db binding peptide of mouse gp100 (gp100), gp10025–33: EGSRNQDWL, was synthesized by Celtek Bioscience, LLC (Nashville, TN). The gp100/H-2Db tetramer (T3700) was synthesized by NIH Tetramer Facility and labeled with PE.

Analysis of Treg cells

Specific CD4+CD25+ Treg cells were identified by intracellular staining of FoxP3 according to manufacturer’s instructions with modification. Briefly, approximately 5 × 105 cells were incubated with anti-mouse CD32/16 monoclonal antibody (2.4G2) for 5–10 min. Then appropriate amount of anti-mouse CD4-PerCp and anti-mouse CD25-FITC were added to the cells and incubated on ice for 20 min in a dark chamber. After two washes with cold PBS + 0.1% BSA + 0.09% NaN3 buffer, cells were fixed with 100 μl of Cytofix/Cytoperm fixation solution (BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA) for 20 min. Cells then were washed with Cytofix/Cytoperm washing buffer twice and stained with appropriate amount of anti-mouse FoxP3 for 30 min. Then cells were washed twice with Cytofix/Cytoperm washing buffer and analyzed by flow cytometry.

Intracellular staining and analysis for IFN-γ

Splenocytes (1 × 106 cells) were stimulated with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate and ionomycin for 5 h. Then IFN- γ expression was determined by intracellular staining in CD8+ T cells according to procedures described previously [42].

CFSE labeling and T cell in vitro proliferation assay

Splenocytes (1 × 107) in 100 μl of PBS + 0.1% BSA were mixed thoroughly with 900 μl of 2.5 μM carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) in PBS. The mixture was incubated at 37°C for 8 min after which 30 ml of RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% FBS (complete medium) was added to terminate the CFSE staining. The cells were centrifuged for 5 min at 800×g. The cell pellet was suspended once with complete medium, centrifuged again, and then resuspended in complete medium at 108 cells/ml. Cells were cultured in anti-mouse CD3 monoclonal antibody coated 24-well plates. Each well contained 2 ml complete medium, 5 μg/ml anti-mouse CD28 monoclonal antibody, and 1 × 106 cells/ml. Cells were cultured at 37°C in an incubator containing 5% CO2 for 90 h. Then cells were harvested and washed with ice-cold PBS + 0.1% BSA. Anti-mouse CD32/16 monoclonal antibody was added to the pelleted cells to block non-specific Fcγ receptor binding, stained with anti-mouse CD8-PE/cy5, and then analyzed by flow cytometry [42]. Proliferation in CD8+ cells was determined based on the respective CFSE gated histograms.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed except were otherwise indicated with the Microsoft Excel statistical program. The results were expressed as mean ± SD. Significant differences between groups were determined using Student’s two-tailed t test. Values were considered different at P < 0.05. The data involving multiple group comparisons in Fig. 1 were analyzed by Graph Pad Prism software. Pair-wise comparisons as a function of weeks were determined by Dunnet’s multiple comparison test after ANOVA. Values were considered significant at P < 0.05.

Fig. 1.

Effects of chronic alcohol consumption on CD44hiCD8+ T cells. a Dot plot showing the gated CD8+ T cells in splenocytes. b Histogram showing the CD44hi cells in the gated splenic CD8+ T cells of melanoma-bearing mice. c Percentage of CD8+CD44hi cells in CD8+ splenocytes from non-tumor injected mice (Cont) and melanoma-bearing mice at the indicated time points after tumor inoculation. Circle alcohol-consuming mice. Square water-drinking mice. Alcohol group different from water group, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.001. Each group contained ten mice and the results are representative to two separate experiments

Results

Chronic alcohol consumption inhibits memory phenotype CD8+ T cell expansion in melanoma-bearing mice

We previously found that chronic alcohol consumption increased the percentage of CD44hiCD8+ memory phenotype T cells in mice not inoculated with melanoma by stimulating T cell homeostatic proliferation [42], and expected that tumor-specific memory T cells would similarly be expanded in mice inoculated with melanoma. To evaluate this possibility, we inoculated mice with B16BL6 melanoma drinking alcohol for 3 months. Alcohol consumption increased the percentage of memory T cells by 19% in non-tumor injected mice compared to mice drinking water (Fig. 1c). In water-drinking mice significant differences in the percentage of memory T cells were observed from 1 to 3 weeks after tumor inoculation compared to control mice not injected with tumor (P < 0.05). The peak response was a twofold increase at 2 weeks and this level was maintained at 3 weeks after inoculation. The percentage of memory T cells in alcohol-consuming mice was not different from mice not injected with tumor at 1 and 3 weeks after tumor inoculation (P > 0.05). A significant increase occurred at week 2; however, the percentage of increase was lower than in water-drinking mice (P < 0.05). These results indicate that alcohol consumption impairs tumor-induced memory T cell expansion. In addition these cells decline to control levels at 3 weeks in the alcohol-consuming mice, but not in the water-drinking mice.

Chronic alcohol consumption inhibits tumor-specific CD8+ T cell expansion

B16BL6 melanoma cells are immunogenic and they induce tumor-specific T cell expansion when inoculated into mice. These cells play essential roles in tumor surveillance and in the inhibition of tumor growth. We used a gp100/H-2Db (T3700) tetramer to examine the effects of chronic alcohol consumption on B16BL6 melanoma-specific CD8+ T cells [25]. We found that the melanoma-specific CD8+ T cells, like the memory T cells, reached a peak 2 weeks after tumor inoculation in both groups and then decreased at 3 weeks (Fig. 2b). The percentages were significantly lower in the alcohol-consuming compared to the water-drinking group at all time periods. The number of gp100-specific CD8+ T cells was 2.5-fold lower in the spleen of the alcohol-consuming mice than the water-drinking mice 3 weeks after tumor inoculation (Fig. 2c).

Fig. 2.

Chronic alcohol consumption decreases B16BL6 melanoma-associated gp100-specific CD8+ T cells. a Dot plot of the gp100/H-2Db tetramer (3700) positive CD8+ cells in the gated splenic CD8+ T cell population from melanoma-bearing mice after 3 weeks. b Percentage of gp100-specific T cells in the splenic CD8+ T cell population of melanoma-bearing mice at the indicated time points after tumor inoculation. Circle water-drinking mice. Square alcohol-consuming mice. ETOH group different from water group, *P < 0.05. c Number of gp100-specific CD8+ T cells in the spleen of melanoma-bearing mice 3 weeks after tumor inoculation. ETOH group different from water group, **P < 0.001. Each group contained ten mice and the results are representative to two separate experiments. ETOH Alcohol-consuming group, Water water-drinking group

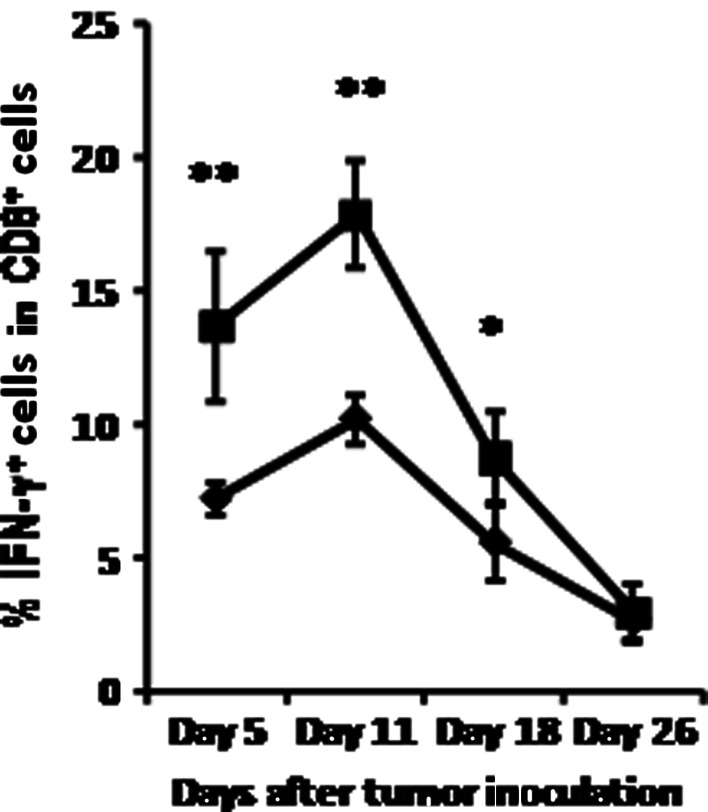

Chronic alcohol consumption accelerates the decay of IFN-γ producing CD8+ T cells in melanoma-bearing mice

We previously reported that chronic alcohol consumption increased the percentage of IFN-γ producing T cells in non-tumor injected mice [42]. Because of the important role that IFN-γ plays in the anti-tumor immune response to melanoma [7, 14, 24], we examined the effect of alcohol consumption on production of this cytokine in CD8+ T cells from the spleen as a function of time. Similar to our findings in non-tumor injected mice, the percentage of IFN-γ producing CD8+ T cells increased proportionately in alcohol consuming compared to water-drinking, melanoma-bearing mice at days 5 and 11: during the early stages of tumor growth (Fig. 3). However, by day 18 both experimental groups exhibited a significant decline in these cells that continued to day 26. The rate of decrease in the percentage of IFN-γ producing cells was more rapid in the alcohol-consuming mice than in the water-drinking mice.

Fig. 3.

Chronic alcohol consumption accelerates the decay of IFN-γ producing cells within the splenic CD8+ T cell population in the melanoma-bearing mice. Closed diamonds water-drinking mice. Closed squares alcohol-consuming mice. Alcohol-consuming group different from water consuming group, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.001. Each group contained ten mice and the results are representative to two separate experiments

Chronic alcohol consumption increases of MDSC but not Treg cells in melanoma-bearing mice

The results presented above indicate that chronic alcohol consumption inhibits memory and tumor-specific T cell proliferation, and accelerates loss of T cells that produce IFN-γ in tumor-bearing mice, suggesting that chronic alcohol consumption facilitates tumor-induced T cell anergy. These results lead us to study further the factors causing T cell dysfunction associated with melanoma. It is well documented that tumors induce specific cell populations that lead to T cell anergy [20]. At least three types of cells are associated with tumor-induced T cell anergy: MDSC, Treg cells, and TAM [6, 17, 20]. We examined if chronic alcohol consumption increased MDSC and Treg cells in melanoma-bearing mice.

MDSC are a heterogeneous cell population composed of immature myeloid cells such as monocytes, granulocytes and dendritic cells at different stages of differentiation [17]. Some MDSC can further differentiate into TAM within the tumor environment [34]. Besides the signature markers, Mac-1 (CD11b) and Gr-1, some of the MDSC also express CD124, which is the interleukin (IL)-4/IL-13 receptor alpha chain. Via this receptor, MDSC can be activated by IL-4 and IL-13 [10]. MDSC activated by IL-13 produces TGF-β to inhibit T cell function [35, 39]. The effects of melanoma on the CD11b+Gr-1+ MDSC are shown in Fig. 4. Gr-1+ cells can be divided into Gr-1hi and Gr-1int populations as shown in Fig. 4a, b. The CD11b+Gr-1int cells, but not CD11b+Gr-1hi cells, exhibit T cell suppressor function [45]. We found that chronic alcohol consumption significantly increased the CD11b+Gr-1int cell population in the PBL from melanoma-bearing mice compared to water-drinking mice (Fig. 4c). The CD11b+Gr-1hi cells were not different between the two groups (data not shown). The percentage of CD124+ cells also significantly increased in the MDSC (Fig. 4d).

Fig. 4.

Chronic alcohol consumption increases the percentages of MDSC in the PBL and of CD124+ cells in MDSC and CD11b+ cells. MDSC were determined 1 week after tumor inoculation. a Dot plot of CD11b+Gr-1int MDSC in the PBL of water-drinking mice. b Dot plot of CD11b+Gr-1int MDSC in the PBL of alcohol-consuming mice, respectively. c Percentage of CD11b+Gr-1int MDSC in the PBL. d Percentage of CD124+ cells in CD11b+Gr-1int MDSC cells. ETOH group significantly different from water group, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.001. ETOH Alcohol-consuming group, Water water-drinking group. Each group contained ten mice and the results are representative to two separate experiments

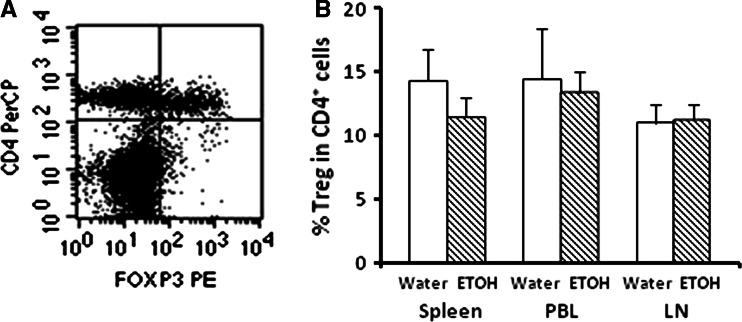

Treg cells comprise 5–10% of peripheral CD4+ T cells. Phenotypically they express IL-2 receptor alpha (CD25) on the cell surface and FOXp3 intracellularly. Thus, they are defined as FOXp3+CD4+CD25+ T cells [9, 13]. Functionally Treg modulate T cell function and play an important role in the control of autoimmune diseases. Additional research also indicates that these cells increase significantly in the lymphoid organs and tumors of tumor-bearing animals and cancer patients, and they facilitate tumor escape from immunosurveillance by inhibiting T cell functions and causing T cell anergy [46]. Thus, we examined if chronic alcohol consumption-induced T cell dysfunction in tumor-bearing mice by increasing Treg cells. We found that the percentages of these cells were not different between the two experimental groups in the spleen, PBL or lymph nodes of melanoma-bearing mice (Fig. 5). Thus, it is unlikely that they play an important role in the rapid disintegration of the CD8+ T cell-related immune responses in the alcohol-consuming mice.

Fig. 5.

Alcohol consumption does not alter Foxp3+CD4+CD25+ Treg cells. Treg cells were determined 2 weeks after tumor inoculation. a Dot plot of Treg cells (upper right quadrant) in cells from the inguinal lymph nodes (LN). b Percentage of Foxp3+CD4+CD25+ Treg cells in the spleen, PBL and LN of melanoma-bearing mice

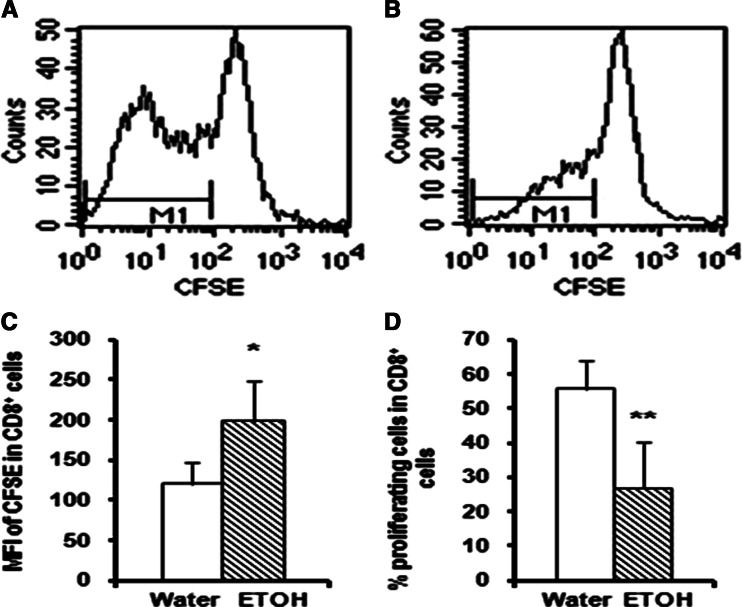

Chronic alcohol consumption compromises anti-CD3 activated T cell proliferation

Since alcohol consumption compromises tumor-induced CD8+ T cell expansion (Fig. 2), we further determined the responsiveness of T cells from the melanoma-bearing mice to T cell receptor stimulation in vitro. We stimulated splenocytes with anti-mouse CD3 and CD28 monoclonal antibodies and determined the decay in the fluorescence intensity of CFSE in the T cells as an indication of cell division. CFSE easily penetrates the cell membrane and gets into the cell. The intracellular esterases cleave the acetate groups to yield the fluorescent carboxyfluorescein molecule. Cell division causes sequential halving of the fluorescence intensity of CFSE. Thus, the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) reflects the proliferation of the labeled cells. A lower MFI indicates a higher proliferation rate. The results in Fig. 6 indicate that 90 h after anti-CD3/CD28 stimulation, the MFI of CD8+ T cells is significantly higher in the alcohol-consuming, tumor-bearing than in the water-drinking, tumor-bearing group (Fig. 6c). The percentage of proliferating CD8+ T cells in the CD8+ T cells of the alcohol-consuming, tumor-bearing mice was also significantly lower than the water-drinking, tumor-bearing animals (Fig. 6d). These results suggest that overall, chronic alcohol consumption impairs proliferation of CD8+ T cells in melanoma-bearing mice in response to anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 stimulation. Similar effects were observed in the proliferation of The CD4+ T cells (data not shown).

Fig. 6.

Effects of chronic alcohol consumption on T cell proliferation in vitro. Splenocytes were isolated from mice consuming alcohol for 3 months and inoculated with 2 × 105 B16BL6 sc for 2 weeks, labeled with CFSE and stimulated with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 monoclonal antibodies for 90 h. a, b Representative histograms indicating the MFI of CFSE in CD8+ T cells from water-drinking tumor-bearing mice and alcohol-consuming tumor-bearing mice, respectively. The marker (bar region) M1 stands for proliferating cells. c Histogram of the MFI of CFSE in CD8+ T cells, ETOH different from water, *P < 0.05. d Histogram of the percentage of proliferating cells in CD8+ T cells, ETOH different from water, **P < 0.001. Each group contained seven mice. ETOH Alcohol-consuming group, Water water-drinking group. The results are representative of two separate experiments

Discussion

In the present study, we demonstrated differential effects of chronic alcohol consumption on CD8+ T cells in mice not inoculated with melanoma and in melanoma-bearing mice. Without exogenous stimulation chronic alcohol consumption activates T cells as evidenced by the increase in CD8+ T cells expressing the memory phenotype and in the percentage of those cells producing IFN-γ (Fig. 1) and [42]. However, in the presence of continued melanoma growth in vivo, memory CD8+ T cell expansion is inhibited and IFN-γ producing CD8+ T cells disproportionately decrease in the alcohol-consuming mice.

It is well documented that tumors cause T cell anergy by producing tumor-derived factors and by inducing immune suppressor cells such as MDSC, TAM and Treg cells [27]. In some cancers tumor-derived factors increase Treg cells, which in turn induce T cell anergy [33]; however, we did not find any changes in the percentage of Treg cells in the alcohol-consuming tumor-bearing mice in the present study. Therefore, it is unlikely that these cells are involved in the T cell dysfunction induced by alcohol consumption in tumor-bearing mice. We did, however, show that MDSC are disproportionately increased in the alcohol-consuming, melanoma-bearing mice compared to their respective water-drinking controls. MDSC are induced by tumor-derived factors such as IL-6, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), etc. [20]. It is well documented that chronic alcohol consumption elevates the level of IL-6 in the blood and increases the production of GM-CSF [12, 36]. Results from in vivo and in vitro tumor models indicate that low doses of alcohol up-regulate VEGF expression [11, 38]. Whether this is also the case with chronic high dose alcohol consumption is not known. These studies indicate that chronic alcohol consumption has the potential to increase the cytokines and growth factors that are required for the induction of MDSC in the tumor-bearing mice.

Once MDSC are induced, these cells must be activated to suppress T cell function. It is known that IFN-γ produced by T cells plays an important role in the initiation of MDSC activation [10]. Thus, the expression of IFN-γ in T cells and CD124 (IL-13 receptor) in MDSC are crucial to MDSC activation. Alcohol consumption increases IFN-γ producing T cells in non-tumor-bearing mice [42] and also during the early stages of tumor growth (Fig. 3). It also increases the percentage of CD124+ expressing CD11b+Gr-1int MDSC (Fig. 4). This is further support for the hypothesis that chronic alcohol consumption enhances the generation and activation of MDSC. Activated MDSC produce IFN-γ and IL-13 to maintain self-activation [10]; however, how alcohol consumption further affects the production of IFN- γ and IL-13 as well as the diverse activities of these cells remains to be elucidated.

One of the important features of MDSC is the simultaneous activation of arginase I and inducible nitric oxide synthase [10]. Both enzymes use arginine as their substrate. With the increase and activation of MDSC, the availability of arginine is significantly decreased in the tumor-bearing host [28]. This arginine deficit arrests the cell-cycle at the G0–G1 stage in T lymphocytes due to a failure to up-regulate the expression of cyclin D3 and cyclin-dependent kinase 4 [29]. We previously found that chronic alcohol consumption significantly decreases the concentration of arginine in the plasma of B16BL6 melanoma-bearing mice compared to their water-drinking, tumor-bearing counterpart [22], and this finding underscores the significance of the associated increase of MDSC and dysfunction of T cells observed in the present study.

It is well recognized that nitric oxide is involved in the progression of melanoma as well as other tumors. Specifically, the metastatic B16BL6 melanoma cells used in this study express significantly higher levels of inducible nitric oxide synthase than the parent B16 cell line and the released nitric oxide is known to decrease the cytotoxicity of B16BL6-specific T cells [44]. Inducible nitric oxide synthase, which is upregulated by alcohol consumption [2, 15], also catalyzes the production of peroxinitrites through an arginine-dependent mechanism. Peroxinitrites inhibit the production of IFN-γ in T cells [21], and could be involved in the decreased IFN-γ that we observed as a function of late stage tumor growth (Fig. 3). Thus, the increase in MDSC and compromised expansion of memory T cells and tumor-specific T cells in the alcohol-consuming tumor-bearing mice could be associated with and ultimately be linked to availability of arginine; however, this requires further investigation.

For most types of cancers, the precise mechanism underlying the cause of death is still unknown. It is currently known that multiple factors, such as altered metabolism, cancer-induced cachexia, and impaired immune functions contribute to the cancer-related death. Interaction among these factors is not well known. However, a recent report indicates that certain CD4+ T cells might protect against tumor-induced cachexia [40]. We previously found that chronic alcohol consumption in mice bearing subcutaneous B16BL6 melanoma leads to a major loss in body fat which is reflected in a twofold increase in body weight loss at necropsy compared to melanoma-bearing mice drinking water [22]. This element of the cachectic response could be one factor that contributes to reduced survival in the alcohol-consuming mice. In the present study we found that chronic alcohol consumption impairs tumor-specific CD8+ T cell expansion and IFN-γ production, which are factors that critically affect host survival in tumor immunotherapy [16, 30]. Thus, the factors leading to decreased survival of melanoma-bearing mice chronically consuming alcohol are multifactorial.

In summary, chronic alcohol consumption inhibits tumor-induced memory T cell and tumor-specific T cell expansion, and accelerates the decay of IFN-γ producing T cells in B16BL6 melanoma-bearing mice. The dysfunction of T cells is consistent with the increase of MDSC in the tumor-bearing, alcohol-consuming mice.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism grants RO1AA07293 and KO5AA017149.

Footnotes

An erratum to this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00262-010-0854-9

References

- 1.(2007) Food, nutrition, physical activity, and the prevention of cancer; a global perspective. World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research, Washington, DC

- 2.Baraona E, Zeballos GA, Shoichet L, Mak KM, Lieber CS. Ethanol consumption increases nitric oxide production in rats, and its peroxynitrite-mediated toxicity is attenuated by polyenylphosphatidylcholine. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2002;26:883–889. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blank SE, Meadows GG. Ethanol modulates metastatic potential of B16BL6 melanoma and host responses. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1996;20:624–628. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1996.tb01664.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boon T, Coulie PG, Van den Eynde BJ, van der Bruggen P. Human T cell responses against melanoma. Annu Rev Immunol. 2006;24:175–208. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.24.021605.090733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dunn GP, Bruce AT, Ikeda H, Old LJ, Schreiber RD. Cancer immunoediting: from immunosurveillance to tumor escape. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:991–998. doi: 10.1038/ni1102-991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elgert KD, Alleva DG, Mullins DW. Tumor-induced immune dysfunction: the macrophage connection. J Leukoc Biol. 1998;64:275–290. doi: 10.1002/jlb.64.3.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Finbloom DS, Larner AC, Nakagawa Y, Hoover DL. Culture of human monocytes with granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor results in enhancement of IFN-gamma receptors by suppression of IFN-gamma-induced expression of the gene IP-10. J Immunol. 1993;150:2383–2390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Finn OJ. Cancer immunology. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2704–2715. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra072739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fontenot JD, Gavin MA, Rudensky AY. Foxp3 programs the development and function of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:330–336. doi: 10.1038/ni904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gallina G, Dolcetti L, Serafini P, De Santo C, Marigo I, Colombo MP, Basso G, Brombacher F, Borrello I, Zanovello P, Bicciato S, Bronte V. Tumors induce a subset of inflammatory monocytes with immunosuppressive activity on CD8+ T cells. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:2777–2790. doi: 10.1172/JCI28828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gu JW, Bailey AP, Sartin A, Makey I, Brady AL. Ethanol stimulates tumor progression and expression of vascular endothelial growth factor in chick embryos. Cancer. 2005;103:422–431. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hong F, Kim WH, Tian Z, Jaruga B, Ishac E, Shen X, Gao B. Elevated interleukin-6 during ethanol consumption acts as a potential endogenous protective cytokine against ethanol-induced apoptosis in the liver: involvement of induction of Bcl-2 and Bcl-x(L) proteins. Oncogene. 2002;21:32–43. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hori S, Nomura T, Sakaguchi S. Control of regulatory T cell development by the transcription factor Foxp3. Science. 2003;299:1057–1061. doi: 10.1126/science.1079490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kakuta S, Tagawa Y, Shibata S, Nanno M, Iwakura Y. Inhibition of B16 melanoma experimental metastasis by interferon-gamma through direct inhibition of cell proliferation and activation of antitumour host mechanisms. Immunology. 2002;105:92–100. doi: 10.1046/j.0019-2805.2001.01342.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khanna D, Kan H, Fang Q, Xie Z, Underwood BL, Jain AC, Williams HJ, Finkel MS. Inducible nitric oxide synthase attenuates adrenergic signaling in alcohol fed rats. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2007;50:692–696. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0b013e318158de08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Klebanoff CA, Gattinoni L, Restifo NP. CD8+ T-cell memory in tumor immunology and immunotherapy. Immunol Rev. 2006;211:214–224. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2006.00391.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kusmartsev S, Gabrilovich DI. Immature myeloid cells and cancer-associated immune suppression. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2002;51:293–298. doi: 10.1007/s00262-002-0280-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mackensen A, Carcelain G, Viel S, Raynal MC, Michalaki H, Triebel F, Bosq J, Hercend T. Direct evidence to support the immunosurveillance concept in a human regressive melanoma. J Clin Invest. 1994;93:1397–1402. doi: 10.1172/JCI117116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maeda M, Nagawa H, Maeda T, Koike H, Kasai H. Alcohol consumption enhances liver metastasis in colorectal carcinoma patients. Cancer. 1998;83:1483–1488. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19981015)83:8<1483::AID-CNCR2>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marigo I, Dolcetti L, Serafini P, Zanovello P, Bronte V. Tumor-induced tolerance and immune suppression by myeloid derived suppressor cells. Immunol Rev. 2008;222:162–179. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00602.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mazzoni A, Bronte V, Visintin A, Spitzer JH, Apolloni E, Serafini P, Zanovello P, Segal DM. Myeloid suppressor lines inhibit T cell responses by an NO-dependent mechanism. J Immunol. 2002;168:689–695. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.2.689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Núñez NP, Carter PA, Meadows GG. Alcohol consumption promotes body weight loss in melanoma-bearing mice. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2002;26:617–626. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2002.tb02583.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ostrand-Rosenberg S. Immune surveillance: a balance between protumor and antitumor immunity. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2008;18:11–18. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2007.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ostrand-Rosenberg S, Clements VK, Terabe M, Park JM, Berzofsky JA, Dissanayake SK. Resistance to metastatic disease in STAT6-deficient mice requires hemopoietic and nonhemopoietic cells and is IFN-gamma dependent. J Immunol. 2002;169:5796–5804. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.10.5796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Overwijk SS, Tsung A, Irvine KR, Parkhurst MR, Goletz TJ, Tsung K, Caroll MW, Liu C, Moss B, Rosenberg SA, Restifo NP. gp100/pmel 17 is a murine tumor rejection antigen: induction of “self”-reactive, tumoricidal T cells using high-affinity, altered peptide ligand. J Exp Med. 1998;188:277–286. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.2.277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Paull DE, Updyke GM, Baumann MA, Chin HW, Little AG, Adebonojo SA. Alcohol abuse predicts progression of disease and death in patients with lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 2005;80:1033–1039. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2005.03.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rabinovich GA, Gabrilovich D, Sotomayor EM. Immunosuppressive strategies that are mediated by tumor cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2007;25:267–296. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rodriguez PC, Ochoa AC. Arginine regulation by myeloid derived suppressor cells and tolerance in cancer: mechanisms and therapeutic perspectives. Immunol Rev. 2008;222:180–191. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00608.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rodriguez PC, Quiceno DG, Ochoa AC. l-Arginine availability regulates T-lymphocyte cell-cycle progression. Blood. 2007;109:1568–1573. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-06-031856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rosenberg SA, Dudley ME. Adoptive cell therapy for the treatment of patients with metastatic melanoma. Curr Opin Immunol. 2009;21:233–240. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2009.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rosenberg SA, Dudley ME. Cancer regression in patients with metastatic melanoma after the transfer of autologous antitumor lymphocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101(Suppl 2):14639–14645. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405730101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rosenberg SA, Restifo NP, Yang JC, Morgan RA, Dudley ME. Adoptive cell transfer: a clinical path to effective cancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:299–308. doi: 10.1038/nrc2355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Serafini P, Mgebroff S, Noonan K, Borrello I. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells promote cross-tolerance in B-cell lymphoma by expanding regulatory T cells. Cancer Res. 2008;68:5439–5449. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sica A, Bronte V. Altered macrophage differentiation and immune dysfunction in tumor development. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:1155–1166. doi: 10.1172/JCI31422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sinha P, Clements VK, Ostrand-Rosenberg S. Interleukin-13-regulated M2 macrophages in combination with myeloid suppressor cells block immune surveillance against metastasis. Cancer Res. 2005;65:11743–11751. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Spies CD, Lanzke N, Schlichting U, Muehlbauer S, Pipolo C, von Mettenheim M, Lehmann A, Morawietz L, Nattermann H, Sander M. Effects of ethanol on cytokine production after surgery in a murine model of gram-negative pneumonia. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2008;32:331–338. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00567.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Swann JB, Smyth MJ. Immune surveillance of tumors. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:1137–1146. doi: 10.1172/JCI31405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tan W, Bailey AP, Shparago M, Busby B, Covington J, Johnson JW, Young E, Gu JW. Chronic alcohol consumption stimulates VEGF expression, tumor angiogenesis and progression of melanoma in mice. Cancer Biol Ther. 2007;6:1211–1217. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-07-0427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Terabe M, Matsui S, Park JM, Mamura M, Noben-Trauth N, Donaldson DD, Chen W, Wahl SM, Ledbetter S, Pratt B, Letterio JJ, Paul WE, Berzofsky JA. Transforming growth factor-beta production and myeloid cells are an effector mechanism through which CD1d-restricted T cells block cytotoxic T lymphocyte-mediated tumor immunosurveillance: abrogation prevents tumor recurrence. J Exp Med. 2003;198:1741–1752. doi: 10.1084/jem.20022227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang Z, Zhao C, Moya R, Davies JD. A novel role for CD4+ T cells in the control of cachexia. J Immunol. 2008;181:4676–4684. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.7.4676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yamshchikov G, Thompson L, Ross WG, Galavotti H, Aquila W, Deacon D, Caldwell J, Patterson JW, Hunt DF, Slingluff CL., Jr Analysis of a natural immune response against tumor antigens in a melanoma survivor: lessons applicable to clinical trial evaluations. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:909s–916s. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang H, Meadows GG. Chronic alcohol consumption in mice increases the proportion of peripheral memory T cells by homeostatic proliferation. J Leukoc Biol. 2005;78:1070–1080. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0605317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang H, Meadows GG. Chronic alcohol consumption perturbs the balance between thymus-derived and bone marrow-derived natural killer cells in the spleen. J Leukoc Biol. 2008;83:41–47. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0707472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang XM, Xu Q. Metastatic melanoma cells escape from immunosurveillance through the novel mechanism of releasing nitric oxide to induce dysfunction of immunocytes. Melanoma Res. 2001;11:559–567. doi: 10.1097/00008390-200112000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhu B, Bando Y, Xiao S, Yang K, Anderson AC, Kuchroo VK, Khoury SJ. CD11b + Ly-6C(hi) suppressive monocytes in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Immunol. 2007;179:5228–5237. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.8.5228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zou W. Regulatory T cells, tumour immunity and immunotherapy. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:295–307. doi: 10.1038/nri1806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]