Abstract

Objective

ABCG1 is highly expressed in macrophages and endothelial cells, two cell types that play important roles in the development of atherosclerosis. We generated Abcg1−/−Apoe−/− mice in order to understand the mechanism and cell types involved in changes in atherosclerosis following loss of ABCG1.

Methods and Results

Abcg1−/−Apoe−/− and Apoe−/− mice, and recipient Apoe−/− mice that had undergone transplantation with bone marrow from Apoe−/− or Abcg1−/−Apoe−/− mice were fed a western diet for 12–16 weeks prior to quantification of atherosclerotic lesions. These studies demonstrated that loss of ABCG1 from all tissues, or from only hematopoietic cells, was associated with significantly smaller lesions that contained increased numbers of TUNEL- and cleaved caspase-3-positive apoptotic Abcg1−/− macrophages. We also identified specific oxysterols that accumulate in the brain and macrophages of the Abcg1−/−Apoe−/− mice. These oxysterols promoted apoptosis and altered the expression of pro-apoptotic genes when added to macrophages in vitro.

Conclusion

Loss of ABCG1 from all tissues or from only hematopoietic cells, results in smaller atherosclerotic lesions populated with increased numbers of apoptotic macrophages, by processes independent of ApoE. Specific oxysterols identified in tissues of Abcg1−/−Apoe−/− mice may be critical as they induce macrophage apoptosis and the expression of pro-apoptotic genes.

Keywords: ABCG1, apolipoprotein E, atherosclerosis, apoptosis, Bid, Bok, oxysterols

Introduction

The ATP binding cassette transporter, subfamily G, member 1 (ABCG1) is one member of a large superfamily of membrane proteins that function to transport substrates across specific membranes.1, 2 Studies with Abcg1−/−LacZ knock-in mice have demonstrated that ABCG1 is expressed in numerous organs and cell types with particularly high expression in macrophages, endothelial and epithelial cells and neurons.3–7

Numerous studies have shown that ABCG1 can function to efflux cholesterol and/or other sterols from cells to various exogenous acceptors, including HDL.8 Studies with Abcg1−/− mice demonstrated that pulmonary macrophages accumulate massive levels of cholesterol and sterol esters, consistent with these cells being particularly sensitive to loss of function of this transporter.3, 6, 9, 10 These lipid-loaded Abcg1−/− pulmonary macrophages also undergo increased apoptosis.11 These data are consistent with the normal role of pulmonary macrophages in clearing cholesterol-containing surfactant from the extracellular space12 with ABCG1 then functioning to eliminate the sterols from the cells to maintain cellular sterol homeostasis.

Loss of ABCG1 from macrophages results in increased expression of multiple inflammatory genes, consistent with a stimulatory effect of the accumulating cellular sterols on inflammation.9, 11, 13 Earlier studies demonstrated that endothelial cells, like macrophages, express particularly high levels of ABCG1.14 Interestingly, administration of a western diet to Abcg1−/− mice was recently shown to increase the inflammatory status and sterol levels of endothelial cells.13 Taken together, these data suggest that loss of ABCG1 results in subtle or gross changes in cellular sterols that may result in induction of inflammatory genes and/or increased apoptosis in two cell types (endothelial cells and macrophages) that are known to play critical roles in the development of atherosclerosis.

Atherosclerosis is a complex disease that is characterized in the early stages by the accumulation of lipid-loaded macrophages (foam cells) in the intima.15 The initial findings that loss of ABCG1 led to the accumulation of sterol-loaded macrophages in the lungs of Abcg1−/− mice3, 6, 10, 11 suggested that hyperlipidemic mice lacking functional ABCG1 would exhibit accelerated atherosclerosis. However, Abcg1−/− mice have a normal plasma lipoprotein profile and thus do not develop significant atherosclerotic lesions even when fed a western diet.16 To assess the role of ABCG1 in the development of atherosclerosis, three groups independently performed bone-marrow transplant studies using donor cells from wild-type or Abcg1−/− C57BL/6 mice and recipient hyperlipidemic Ldlr−/− mice. Although the protocols used in these studies were similar, the conclusions were not; one group reported that transplantation of Abcg1−/− bone marrow led to either a modest but significant increase in atherosclerotic lesions in the Ldlr−/− recipient mice6, 17 or to no change in lesion size.17, 18 In contrast, Baldan et al.16 and Ranalleta et al.19 observed a significant decrease in lesion size in Ldlr−/− mice receiving Abcg1−/− cells. It remains to be determined whether these inconsistencies result from differences in the genetic backgrounds of the mice, from different concentrations of cholesterol in the diet or different treatment times that affect lesion progression.

Alternative mechanisms, that are not necessarily exclusive, were invoked to explain the unexpected decrease in lesion size noted in two of the transplantation studies.16, 19 Ranalletta et al.19 proposed that the Abcg1−/− macrophages secreted increased amounts of ApoE protein, a known anti-atherogenic protein. It was also suggested that increased expression of a second sterol transporter, ABCA1, in the Abcg1−/− macrophages might reduce sterol accumulation in the foam cells and thus impair lesion development.19 In contrast, Baldan et al.16 proposed that the smaller lesions were a result of increased apoptosis of the Abcg1−/− macrophages that populated the atherosclerotic lesions of Ldlr−/− mice. A role for ABCG1 in protection against apoptosis is consistent with studies showing that the lungs of Abcg1−/− mice contain increased TUNEL-positive apoptotic cells11 and overexpression of ABCG1 in cultured cells attenuates oxysterol-induced cell death possibly by stimulating the efflux of either 7β-hydroxycholesterol20 or 7-ketocholesterol21 to exogenous HDL.

Apoptosis plays an important role in the development of atherosclerotic lesions.22–24 An increase in macrophage apoptosis in early lesions has been associated with decreased lesion progression.22 In contrast, an increase in macrophage apoptosis in advanced lesions is thought to promote the development of the necrotic core, a key factor in vulnerable plaque formation and acute thrombosis.24 The increase in apoptotic cells in lesions may result from the accumulation of unesterified cholesterol and/or oxysterols as these lipids are known to stimulate pro-apoptotic processes.25, 26 Support for a role for ABCG1 in preventing apoptosis16 came from studies showing that Abcg1−/− or Abcg1−/− Abca1−/− macrophages exhibit increased apoptosis in vitro compared to wild type cells after a challenge with oxLDL.27, 28

We now report that hyperlipidemic Apoe−/− mice lacking ABCG1 in all tissues or in hematopoietic cells only, exhibit decreased lesions, decreased aortic lesion calcification, and increased macrophage apoptosis as a result of the accumulation of specific pro-apoptotic oxysterols.

Materials and Methods

We fed a western diet for 12–16 weeks to Abcg1−/−Apoe−/− and Apoe−/− mice, and to recipient Apoe−/− mice that had undergone transplantation with bone marrow from Apoe−/− or Abcg1−/−Apoe−/− mice. Atherosclerotic lesion size, apoptosis and oxidized sterol concentrations in macrophages in these mice were determined. For details and further methods please see the online supplemental material (http://atvb.ahajournals.org).

Results

Characterization of Abcg1−/−Apoe−/− Mice

Endothelial cells of Abcg1−/− mice fed a western diet accumulate 7-ketocholesterol, a non-enzymatic product of cholesterol autoxidation.13 Abcg1−/− mice also exhibit decreased endothelium-dependent vasodilatation and decreased eNOS activity.13 Macrophages from Abcg1−/− mice also exhibit increased expression of inflammatory genes and accumulate intracellular 7-ketocholesterol.9, 11 In addition, loss of ABCG1 from macrophages has been reported to result in increased secretion of ApoE protein19, an anti-atherosclerotic protein.29

Consequently, to better understand the effect of loss of function of ABCG1 from all cell types, including macrophages and endothelial cells, and to remove any confounding effects that could arise from altered secretion of ApoE from macrophages, we generated Abcg1−/−Apoe−/− double knockout (DKO) mice. Analysis of the plasma showed that, compared to Apoe−/− mice, DKO mice had increased hemoglobin (14.0±0.67 vs. 12.68±0.96; p<0.04; n=10) and hematocrit values (40.42±1.94 vs. 36.8±2.14; p<0.03), but that lipid and lipoprotein levels and a broad array of hematology values did not significantly differ between the two genotypes (data not shown).

To accelerate the development of atherosclerosis, DKO and Apoe−/− mice were challenged with a western diet (21% fat and 0.2% cholesterol). After 16 weeks, analysis of plasma from DKO and Apoe−/− mice indicated that there was no significant difference in lipid levels (Supplemental Table I) or lipoprotein profile (Supplemental Fig. IA). Lungs of the DKO, but not the Apoe−/− mice appeared white and stained positive with Oil Red O, especially in areas enriched in Lac Z-expressing macrophages (Supplemental Fig. II, data not shown). In addition, red and white pulp of spleens of the DKO, but not Apoe−/− mice, contained cells that were positive for both Lac Z and Oil Red O (Supplemental Fig. II). Thus, multiple tissues of the DKO mice exhibited evidence of neutral lipid accumulation.

Abcg1−/−Apoe−/− Mice have Decreased Atherosclerotic Lesions Containing Increased Numbers of Apoptotic Macrophages

After 16 weeks on the western diet atherosclerotic lesions were determined both by en face analysis of the Sudan IV-stained descending aorta or following analysis of stained frozen sections (25–30 sections/mouse) of the aortic root.

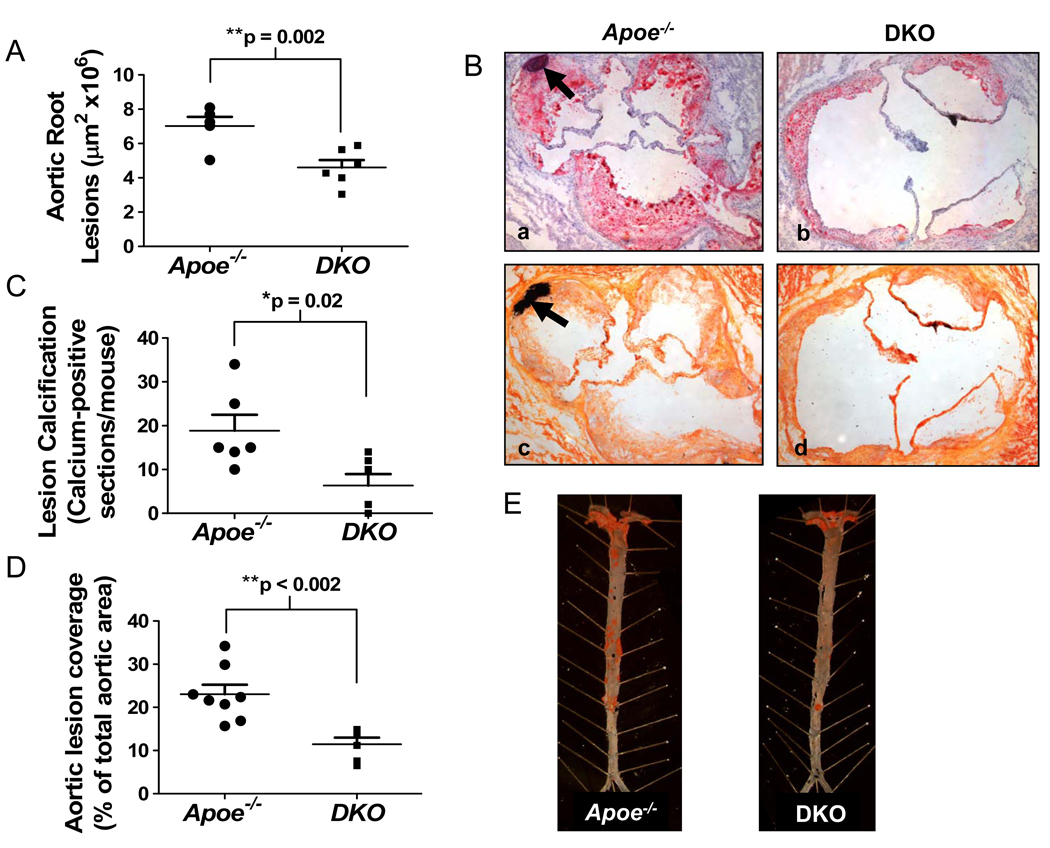

The data show that Abcg1−/−Apoe−/− mice had significantly smaller lesions than Apoe−/− mice in both the aortic root (Fig. 1A; Fig. 1B, panel b vs. a) and in the descending aorta (Fig. 1D, E). The lesions of the DKO mice contained numerous LacZ-positive macrophages (Supplemental Fig. III), thus ruling out the possibility that DKO macrophages do not enter the subendothelial space. Calcified deposits in the lesions of the aortic root, identified following staining of sections with either von Kossa or Oil Red O, hematoxylin and fast green, were significantly reduced in the Abcg1−/−Apoe−/− mice (Fig. 1C; Fig. 1B, panel d vs. c and b vs. a), consistent with the smaller lesions in the DKO mice. Photomicrographs taken at higher magnification illustrate that the calcium deposition occurs within the aortic lesions, adjacent to the medial layer (Supplemental Fig. IV).

Figure 1.

Atherosclerosis and lesion calcification are reduced in Abcg1−/−Apoe−/− as compared to Apoe−/− mice. DKO and Apoe−/− mice (6–8 mice per group) were fed a western diet for 16 weeks. (A) Frozen sections (25–30 sections/mouse; n=6 mice/group) from the aortic root were stained with Oil Red O and counter stained with hematoxylin and fast green before lesion areas were determined as described in the Methods. Each point represents an individual mouse. **p<0.01 (B) Shows representative Oil Red O-stained sections counter stained with hematoxylin and fast green (panels a and b) and adjacent sections stained with von Kossa stain (panels c and d). Calcification/calcium phosphate deposits, are indicated by arrows in panels a and c. (C) Quantification of lesion calcification. *p<0.05 (D) Lesions in the descending aorta were identified by en face analysis and quantified as described in the Methods (n=8 mice/group). **p<0.01 (E) Representative Sudan IV-stained aortas are shown from the two genotypes.

Loss of ABCG1 from Hematopoietic Cells Delays the Development of Atherosclerosis and Increases Apoptotic Macrophages in the Lesions, Independent of ApoE

To determine the relative importance of hematopoietic and non-hematopoietic Abcg1−/− cells on the observed changes in atherosclerosis noted in the Abcg1−/−Apoe−/− mice (Fig. 1), we performed bone marrow transplant studies wherein bone marrow from either Apoe−/− or DKO mice was transplanted into recipient Apoe−/− animals. After a 4 week recovery period, the mice were fed a western diet for 12 weeks. Analysis of the lungs of the Apoe−/− recipients indicated that mice that had been transplanted with DKO donor cells, but not those receiving Apoe−/− cells, contained Lac Z-positive cells and white patches consistent with lipid deposition in macrophages (data not shown).

Neither plasma lipid levels (Supplemental Table II) nor plasma lipoprotein profiles (Supplemental Fig. IB), were significantly different between the two groups of recipient Apoe−/− mice. Compared to wild type mice, all transplanted mice contained elevated levels of VLDL and LDL and low levels of HDL independent of the genotype of the donor cells (Supplemental Fig. IB; data not shown).

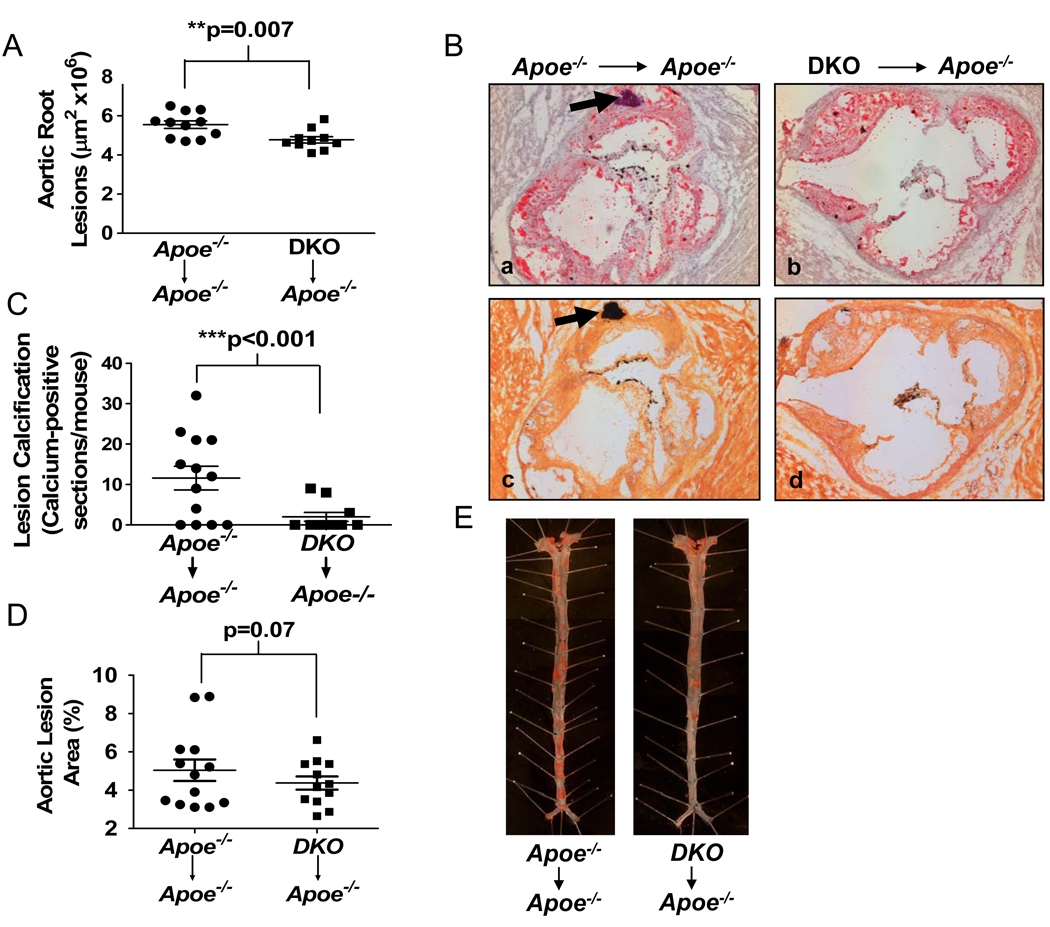

Quantification of the atherosclerotic lesions showed that they were significantly smaller in mice transplanted with DKO as compared to Apoe−/− donor bone marrow (Fig. 2A; Fig. 2B, panel b vs. a). Interestingly, and in agreement with the studies utilizing whole body DKO mice, calcification in the lesions of the aortic root was also significantly decreased in mice transplanted with Abcg1−/−Apoe−/− donor bone marrow (Fig. 2C; Fig. 2B, panel d vs. c and b vs. a), consistent with smaller lesions in the latter mice.

Figure 2.

Apoe−/− mice lacking ABCG1 in hematopoietic cells have reduced atherosclerotic lesions. Apoe−/− mice were transplanted with bone marrow from Apoe−/− or DKO mice before being fed a western diet for 12 weeks. All analyses were performed as described in Fig. 1. Lesion size (A) and calcification (C) in the aortic root sections (10–13 mice per group), and lesion size in the descending aorta (D) (13–16 mice per group) are shown, with each point representing one mouse. (B) Representative sections from the aortic root after staining with Oil Red O and counterstaining with hematoxylin and fast green (panels a and b) or adjacent sections stained with von Kossa stain (panels c, d). Arrows identify calcium deposits. (E) Representative Sudan IV-stained sections of the descending aorta. **p<0.01, ***p<0.001.

En face analysis of the descending aorta indicated a trend towards lower lesions in those mice receiving bone marrow from Abcg1−/−Apoe−/− mice, although the difference just failed to reach statistical significance (Fig. 2D, E). However, lesion coverage in the thoracic and abdominal sections, but not the proximal sections, were significantly smaller in mice transplanted with DKO cells (Supplemental Fig. V) consistent with slower lesion progression in mice receiving DKO donor cells.

Increased Macrophage Apoptosis in Lesions of DKO Mice

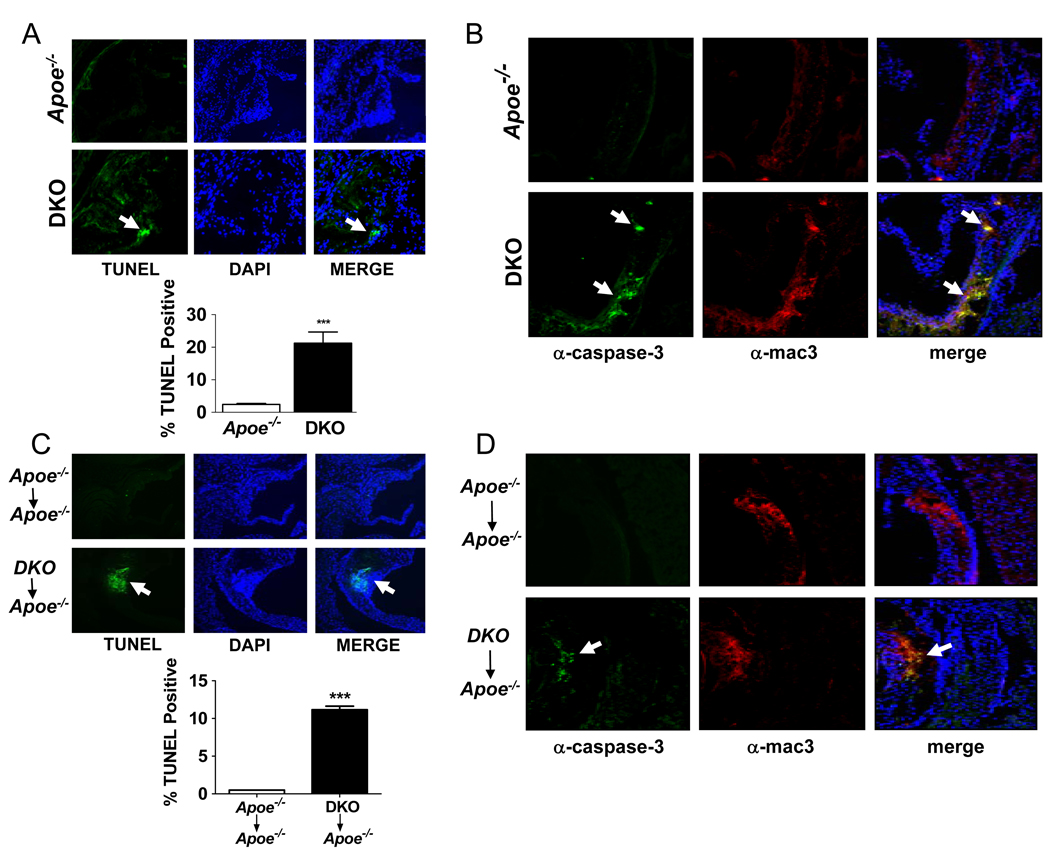

After 16 weeks on the western diet the aortic root lesions of DKO mice contained significantly greater numbers of TUNEL-positive cells, often present as multi-cell aggregates (Fig. 3A). A similar difference was seen in the bone marrow transplant studies wherein we observed a 22-fold increase in TUNEL-positive cells in lesions of Apoe−/− mice transplanted with DKO as compared to Apoe−/− donor cells (Fig. 3C).

Figure 3.

ABCG1 deficiency results in increased numbers of apoptotic macrophages in atherosclerotic lesions. The indicated whole body knockout mice (A, B) or bone marrow transplanted mice (C, D) were fed a western diet as described in Figs. 1–2. TUNEL- and DAPI-positive cells (green and blue, respectively) were determined in adjacent sections of the aortic roots (A, C) of the indicated mice. Aggregated TUNEL-positive cells are indicated by arrows. Graphs show the percentage of TUNEL-positive cells in the lesions. (B, D) Adjacent frozen sections were also stained with either antibody to cleaved caspase-3 (green foci marked by arrows) or macrophages (red). The merged images are also shown (B and D). The data are representative of multiple stained sections (n=15/sections/mouse; 3 mice/genotype). Data are expressed as mean ±SEM. *** p<0.001.

One of the late events in apoptosis involves cleavage of the precursor form of caspase-3 to form an active protease.30 To identify cells undergoing apoptosis within the lesions of the aortic root, frozen sections from the aortic roots of mice were immunostained with antibodies to macrophages and to the cleaved form of caspase-3. Analysis of multiple stained sections indicated that lesions of Apoe−/− mice had few active caspase-3-positive cells, whereas numerous active caspase-3-positive cells, often present as aggregates, were present in the lesions of DKO mice (Fig. 3B) and in Apoe−/− mice that were the recipients of the DKO bone marrow (Fig. 3D). These tissue sections also stained positive for macrophages when co-stained with anti-mac3 (Fig. 3B–D). Analysis of the merged figures showed that cleaved caspase-3-positive and anti-mac3-positive cells co-localize in the lesions of mice lacking ABCG1 (Figs. 3B, D), thus identifying the apoptotic cells as macrophages. Interestingly, cleaved caspase-3- or TUNEL-positive endothelial cells were never observed in any section suggesting that loss of ABCG1 from endothelial cells did not result in accelerated apoptosis in vivo (data not shown).

Taken together, the data from studies with whole body DKO mice and following bone marrow transplantation demonstrate that loss of ABCG1 from hematopoietic cells alone is sufficient to slow the progression of atherosclerotic lesions. This is associated with an increase in the number of apoptotic cells in the lesions and decreased calcification within the lesion. All these changes occur by mechanisms that are independent of ApoE.

Identification of Specific Oxysterols Accumulating in Abcg1−/−Apoe−/− Macrophages

Identification of specific sterols that accumulate within macrophages in atherosclerotic lesions is complicated by the inability to obtain sufficient numbers of cells. Consequently, we performed bronchoalveolar lavage on Apoe−/− and Abcg1−/−Apoe−/− mice and recovered alveolar macrophages. Analyses of these samples using isotope dilution mass spectrometry identified a number of oxysterols, including 24-, 25-, and 27-hydroxycholesterols that accumulate in the Abcg1−/−Apoe−/− and Abcg1−/− cells compared to wild type or Apoe−/− cells (Table 1). We also show that, compared to Apoe−/− mice, 25- and 27-hydroxycholesterol levels are significantly increased in the brains of the DKO mice (Table 1). Hence, the increase in the levels of these enzymatically synthesized oxysterols is not limited to macrophages.

Table 1.

Macrophages and brain sterol levels are given as µg or ng sterol/mg protein (macrophages) or /mg wet weight (brain), respectively. Macrophages were isolated from 5 mice/genotype and combined for sterol analysis. Brain sterols were determined for individual brains (8 brains/genotype) and the mean and SE provided.

| Genotype | Cholesterol (µg/mg) |

24(S)-OH- cholesterol (ng/mg) |

25-OH- cholesterol (ng/mg) |

27-OH- cholesterol (ng/mg) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Macrophages: | 21.57 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.6 | |

| WT | |||||

| Abcg1−/− | 115.95 | 4.7 | 62.1 | 17.9 | |

| Apoe−/− | 48.78 | 3.6 | 41.9 | 4.1 | |

| Abcg1−/−Apoe−/− | 93.95 | 4.1 | 52.6 | 19.8 | |

| Brain: | 16.43 ± 0.3 |

42.03 ± 1.7 |

0.03 ± 0.003 |

0.31 ± 0.008 |

|

| Apoe−/− | |||||

| Abcg1−/−Apoe−/− | 17.17 ± 0.6 |

50.06 ± 4.3 |

0.07* ± 0.009 |

0.47** ± 0.02 |

|

p<0.005;

p<0.00005

Abcg1−/− Bone Marrow-derived Macrophages Display a Pro-apoptotic Phenotype and Altered Sensitivity to Oxysterols

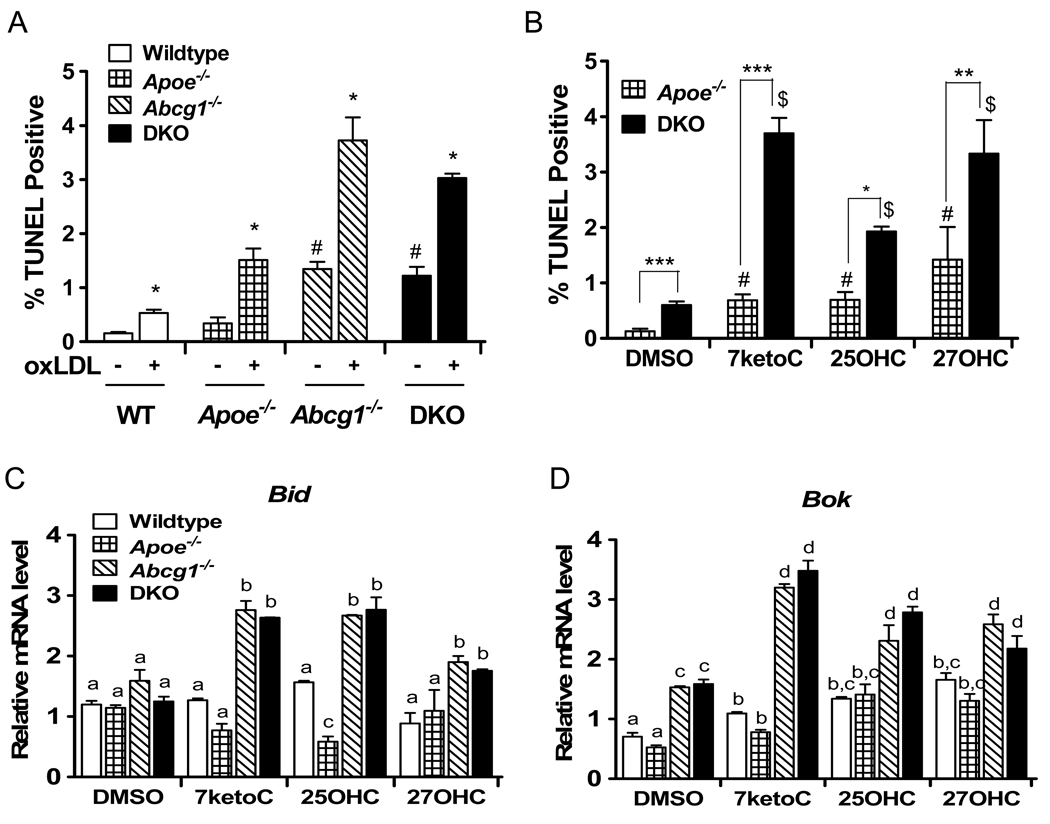

The data of Fig. 4A show that after 7 days in culture, Abcg1−/− and Abcg1−/−Apoe−/− bone marrow derived macrophages (BMDM) exhibited a 3- to 6-fold increase in TUNEL-positive cells, as compared to wild type or Apoe−/− cells. Although exposure of all these cells to oxidized LDL (oxLDL) for 8 h increased TUNEL staining, the highest levels of apoptosis/TUNEL staining were seen when cells lacked ABCG1 (Fig. 4A), consistent with the proposal that ABCG1 is critical for limiting apoptosis in response to lipid-loading. As expected, oxLDL treatment of wild type, Apoe−/− , Abcg1−/− or Abcg1−/−Apoe−/− BMDMs increased the expression of the LXR target genes Abca1 and Srebp1c and the anti-apoptotic gene Aim (Supplemental Fig. VI A–C).

Figure 4.

Macrophages lacking ABCG1 exhibit increased apoptosis in response to oxLDL or oxysterols and enhanced induction of pro-apoptotic genes. BMDMs in quadruplicate were differentiated in L929-conditioned media containing 10% FBS. After 7 days the media was replaced with media containing 0.2% BSA media ± oxidized LDL (50 µg/ml) (A) or the indicated oxysterol (10 µM) (B–D). After 8 h the number of TUNEL-positive apoptotic cells (total cells >1000 cells/field; 6 fields/genotype) (A, B) or the mRNA levels of Bid and Bok (C, D) were determined. Data are expressed as mean ±SEM and are representative of two experiments. (A) * p<0.001, significantly different than (−) oxLDL; # p<0.001, significantly different than WT and Apoe−/−. (B) #, p <0.001 significantly different than Apoe−/− DMSO-treated; $, p<0.001 significantly different than DKO DMSO-treated. (C, D) a,b,c,d bars with different letters are significantly different from one another at the level of p<0.001.

Based on the finding that specific oxysterols accumulate in alveolar macrophages and the brains of Abcg1−/−Apoe−/− mice (Table 1), we next investigated whether cells lacking ABCG1 and/or ApoE are particularly sensitive to these same oxysterols. In the absence of added oxysterols, the number of BMDMs undergoing apoptosis was 4-fold greater in Abcg1−/−Apoe−/− as compared to Apoe−/− cells (Fig. 4B, DMSO). Addition of 10 µM 7-ketocholesterol, 25-hydroxycholesterol or 27-hydroxycholesterol increased the number of TUNEL-positive cells (Fig. 4B). Importantly, the percent of apoptotic cells was greatest following addition of oxysterols to the DKO BMDMs (Fig. 4B).

The increased sensitivity of cells lacking ABCG1 to oxysterol-induced apoptosis suggested that these cells might also exhibit altered expression of genes involved in apoptosis. Consequently, we performed a PCR-based screen to identify apoptotic genes that were altered after exposure of cells to 50 µg/ml ox-LDL (data not shown). Confirmation of altered gene expression came from subsequent RT-qPCR analysis that showed that incubation of cells with specific oxysterols increased the expression of Bid and Bok, two members of the Bcl-2 pro-apoptotic gene family (Fig. 4C, D). Importantly, expression of Bid and Bok was higher in DKO or Abcg1−/− BMDMs as compared to wild type or Apoe−/− cells (Fig. 4C, D).

Discussion

We report here on the generation and initial characterization of Abcg1−/−Apoe−/− mice. Studies with both whole body Abcg1−/−Apoe−/− mice and following bone marrow transplantation into Apoe−/− mice demonstrate that atherosclerotic lesion progression is reduced when mice lack ABCG1 either in all tissues or in macrophages and other hematopoietic cells (Figs. 1, 2). In preliminary studies we also noted that neutrophils accumulated in the adventitia, adjacent to lesions of Apoe−/− and Abcg1−/−Apoe−/− transplanted mice (data not shown) consistent with increased inflammation. Despite this latter finding, and the observation that endothelial cells lacking ABCG1 exhibit increased inflammatory properties13, the current data suggest that the decrease in lesion size is dependent upon loss of ABCG1 from hematopoietic cells and occurs by processes independent of ApoE. Whether the profound decrease in calcium deposition in the atherosclerotic lesions (Fig. 1, 2 and Supplemental Fig. IV) is simply a consequence of the smaller lesions or is a consequence of the increase in apoptotic macrophages in the lesions will require additional studies.

The importance of macrophage apoptosis in affecting early lesion development was initially reported by Arai et al.22 as a result of studies with mice lacking the anti-apoptotic gene Aim. Importantly, the expression of Aim is largely restricted to macrophages.22 Arai et al. demonstrated a remarkable (>90%) attenuation of atherosclerotic lesions in hyperlipidemic Aim−/−Ldlr−/− mice, as compared to Aim+/+Ldlr−/− mice.22 These data suggested that increased apoptosis of macrophages limited early development and progression of atherosclerotic lesions.22 Strikingly, in the current study we show that cells lacking ABCG1 are more susceptible to oxysterols/induced apoptosis despite increased expression of Aim mRNA.

The current data extend a previous report where it was shown that atherosclerotic lesions were decreased in Apoe−/− recipient mice following repopulation with Abcg1−/−Apoe+/+ cells, as compared to Abcg1+/+Apoe+/+ (wild type) bone marrow.16 However, the interpretation of the latter result was complicated by the fact that expression of ApoE in the donor marrow cells is sufficient to attenuate atherosclerosis in recipient Apoe−/− mice.31 It was further complicated by the report that loss of ABCG1 from macrophages resulted in increased secretion of ApoE.18 Although we have not been able to confirm the latter finding, the current data demonstrate that the decrease in lesion progression following deletion of ABCG1 can occur independent of ApoE.

Lammers et al.17 recently reported that atherosclerotic lesions of Ldlr−/−Apoe+/+ mice were increased following transplantation with Abcg1−/−Apoe−/− bone marrow.17 However the finding that the transplanted mice expressed ApoE in many non-hematopoietic cells makes comparison with the current studies difficult. This same group has previously reported either no change or an increase6, 18 in lesion size following transplantation of Abcg1−/− bone marrow into hyperlipidemic Ldlr−/− mice. Whether these differences in lesion progression relate to differences in serum cholesterol levels32 or to differences in genetic background of the mice, length of time on different diets, and the extent of the disease remains unclear at the current time.

The result of the present, as well as previous work are consistent with a more important role of the ABCG1 transporter for efflux of a number of oxysterols than for efflux of cholesterol.5, 20, 21, 33, 34 Loss of this transporter thus leads to a higher accumulation of 7-β-hydroxycholesterol, 7-ketocholesterol, 24-, 25- and 27-hydroxycholesterol than of cholesterol. The accumulation of the side-chain oxidized oxysterols is surprising in view of their physiochemical properties which allow them to pass biomembranes at a much higher rate than cholesterol.35 Not only oxysterols, but also desmosterol, an intermediate in the cholesterol biosynthetic pathway, has been shown to accumulate in ABCG1 deficient cells.34 Cytotoxic and apoptotic properties of the side-chain oxidized oxysterols are well documented35, 36 and it is shown here that exposure of macrophages lacking ABCG1 to 7-ketocholesterol, 25-hydroxycholesterol and 27-hydroxycholesterol leads to increased apoptosis.

To summarize, our results are consistent with the possibility that at least part of the apoptotic effects of a loss of the ABCG1 transporter is due to the accumulation of oxysterols. We also demonstrate that loss of ABCG1 from macrophages results in increased expression of the two pro-apoptotic genes Bid and Bok. Whether such changes in pro-apoptotic genes is sufficient to contribute to the increased apoptosis, despite an increase in the expression of the anti-apoptotic gene Aim is unknown.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Drs. A. Fogelman and M. Navab for providing Apoe−/− mice.

Sources of Funding

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (NIH30568 to P.A.E. and A.J.L.; NIH68445 to P.A.E.; HL086566 and DK063491 to R.K.T.; and HL094322 to A.J. L.), grants from the Laubisch Fund (to PAE and A.J.L.), and grants from the Swedish Council and Swedish Brain Power (to I.B.).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures

None

References

- 1.Dean M, Hamon Y, Chimini G. The human ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter superfamily. J Lipid Res. 2001;42:1007–1017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Higgins CF, Linton KJ. The ATP switch model for ABC transporters. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2004;11:918–926. doi: 10.1038/nsmb836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kennedy MA, Barrera GC, Nakamura K, Baldan A, Tarr P, Fishbein MC, Frank J, Francone OL, Edwards PA. ABCG1 has a critical role in mediating cholesterol efflux to HDL and preventing cellular lipid accumulation. Cell Metab. 2005;1:121–131. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tarr PT, Edwards PA. ABCG1 and ABCG4 are coexpressed in neurons and astrocytes of the CNS and regulate cholesterol homeostasis through SREBP-2 .10.1194/jlr.M700364-JLR200. J. Lipid Res. 2008;49:169–182. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M700364-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bojanic DD, Tarr PT, Gale GD, Smith DJ, Bok D, Chen B, Nusinowitz S, Lovgren-Sandblom A, Bjorkhem I, Edwards PA. Differential expression and function of ABCG1 and ABCG4 during development and ageing. J Lipid Res. 2010;51:161–181. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M900250-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Out R, Hoekstra M, Hildebrand RB, Kruit JK, Meurs I, Li Z, Kuipers F, Van Berkel TJ, Van Eck M. Macrophage ABCG1 deletion disrupts lipid homeostasis in alveolar macrophages and moderately influences atherosclerotic lesion development in LDL receptor-deficient mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:2295–2300. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000237629.29842.4c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang N, Yvan-Charvet L, Lutjohann D, Mulder M, Vanmierlo T, Kim TW, Tall AR. ATP-binding cassette transporters G1 and G4 mediate cholesterol and desmosterol efflux to HDL and regulate sterol accumulation in the brain. Faseb J. 2008;22:1073–1082. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-9944com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tarr PT, Tarling EJ, Bojanic DD, Edwards PA, Baldan A. Emerging new paradigms for ABCG transporters. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1791:584–593. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2009.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baldan A, Gomes AV, Ping P, Edwards PA. Loss of ABCG1 results in chronic pulmonary inflammation. J Immunol. 2008;180:3560–3568. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.5.3560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baldan A, Tarr P, Vales CS, Frank J, Shimotake TK, Hawgood S, Edwards PA. Deletion of the transmembrane transporter ABCG1 results in progressive pulmonary lipidosis. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:29401-–29410. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606597200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wojcik AJ, Skaflen MD, Srinivasan S, Hedrick CC. A critical role for ABCG1 in macrophage inflammation and lung homeostasis. J Immunol. 2008;180:4273–4282. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.6.4273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wright JR. Immunoregulatory functions of surfactant proteins. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:58–68. doi: 10.1038/nri1528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Terasaka N, Yu S, Yvan-Charvet L, Wang N, Mzhavia N, Langlois R, Pagler T, Li R, Welch CL, Goldberg IJ, Tall AR. ABCG1 and HDL protect against endothelial dysfunction in mice fed a high-cholesterol diet. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:3701–3713. doi: 10.1172/JCI35470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O'Connell BJ, Denis M, Genest J. Cellular physiology of cholesterol efflux in vascular endothelial cells. Circulation. 2004;110:2881–2888. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000146333.20727.2B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lusis AJ. Atherosclerosis. Nature. 2000;407:233–241. doi: 10.1038/35025203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baldan A, Pei L, Lee R, Tarr P, Tangirala RK, Weinstein MM, Frank J, Li AC, Tontonoz P, Edwards PA. Impaired development of atherosclerosis in hyperlipidemic Ldlr−/− and ApoE−/− mice transplanted with Abcg1−/− bone marrow. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:2301–2307. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000240051.22944.dc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lammers B, Out R, Hildebrand RB, Quinn CM, Williamson D, Hoekstra M, Meurs I, Van Berkel TJ, Jessup W, Van Eck M. Independent protective roles for macrophage Abcg1 and Apoe in the atherosclerotic lesion development. Atherosclerosis. 2009;205:420–426. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2009.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Out R, Hoekstra M, Habets K, Meurs I, de Waard V, Hildebrand RB, Wang Y, Chimini G, Kuiper J, Van Berkel TJ, Van Eck M. Combined deletion of macrophage ABCA1 and ABCG1 leads to massive lipid accumulation in tissue macrophages and distinct atherosclerosis at relatively low plasma cholesterol levels. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28:258–264. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.156935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ranalletta M, Wang N, Han S, Yvan-Charvet L, Welch C, Tall AR. Decreased atherosclerosis in low-density lipoprotein receptor knockout mice transplanted with Abcg1−/− bone marrow. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:2308–2315. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000242275.92915.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Engel T, Kannenberg F, Fobker M, Nofer JR, Bode G, Lueken A, Assmann G, Seedorf U. Expression of ATP binding cassette-transporter ABCG1 prevents cell death by transporting cytotoxic 7beta-hydroxycholesterol. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:1673–1680. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.03.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Terasaka N, Wang N, Yvan-Charvet L, Tall AR. High-density lipoprotein protects macrophages from oxidized low-density lipoprotein-induced apoptosis by promoting efflux of 7-ketocholesterol via ABCG1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:15093–15098. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704602104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arai S, Shelton JM, Chen M, Bradley MN, Castrillo A, Bookout AL, Mak PA, Edwards PA, Mangelsdorf DJ, Tontonoz P, Miyazaki T. A role for the apoptosis inhibitory factor AIM/Spalpha/Api6 in atherosclerosis development. Cell Metab. 2005;1:201–213. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tabas I. Consequences and therapeutic implications of macrophage apoptosis in atherosclerosis: the importance of lesion stage and phagocytic efficiency. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25:2255–2264. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000184783.04864.9f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gautier EL, Huby T, Witztum JL, Ouzilleau B, Miller ER, Saint-Charles F, Aucouturier P, Chapman MJ, Lesnik P. Macrophage apoptosis exerts divergent effects on atherogenesis as a function of lesion stage. Circulation. 2009;119:1795–1804. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.806158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Feng B, Yao PM, Li Y, Devlin CM, Zhang D, Harding HP, Sweeney M, Rong JX, Kuriakose G, Fisher EA, Marks AR, Ron D, Tabas I. The endoplasmic reticulum is the site of cholesterol-induced cytotoxicity in macrophages. Nat Cell Biol. 2003;5:781–792. doi: 10.1038/ncb1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Myoishi M, Hao H, Minamino T, Watanabe K, Nishihira K, Hatakeyama K, Asada Y, Okada K, Ishibashi-Ueda H, Gabbiani G, Bochaton-Piallat ML, Mochizuki N, Kitakaze M. Increased endoplasmic reticulum stress in atherosclerotic plaques associated with acute coronary syndrome. Circulation. 2007;116:1226–1233. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.682054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yvan-Charvet L, Ranalletta M, Wang N, Han S, Terasaka N, Li R, Welch C, Tall AR. Combined deficiency of ABCA1 and ABCG1 promotes foam cell accumulation and accelerates atherosclerosis in mice. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:3900–3908. doi: 10.1172/JCI33372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baldan A, Pei L, Lee R, Tarr P, Tangirala RK, Weinstein MM, Frank J, Li AC, Tontonoz P, Edwards PA. Impaired Development of Atherosclerosis in Hyperlipidemic Ldlr−/− and ApoE−/− Mice Transplanted With Abcg1−/− Bone Marrow. 10.1161/01.ATV.0000240051.22944.dc. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:2301–2307. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000240051.22944.dc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Curtiss LK, Boisvert WA. Apolipoprotein E and atherosclerosis. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2000;11:243–251. doi: 10.1097/00041433-200006000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Salvesen GS, Abrams JM. Caspase activation - stepping on the gas or releasing the brakes? Lessons from humans and flies. Oncogene. 2004;23:2774–2784. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Boisvert WA, Spangenberg J, Curtiss LK. Treatment of severe hypercholesterolemia in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice by bone marrow transplantation. J Clin Invest. 1995;96:1118–1124. doi: 10.1172/JCI118098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Out R, Hoekstra M, Meurs I, de Vos P, Kuiper J, Van Eck M, Van Berkel TJ. Total body ABCG1 expression protects against early atherosclerotic lesion development in mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27:594–599. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000257136.24308.0c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Burgess BL, Parkinson PF, Racke MM, Hirsch-Reinshagen V, Fan J, Wong C, Stukas S, Theroux L, Chan JY, Donkin J, Wilkinson A, Balik D, Christie B, Poirier J, Lutjohann D, Demattos RB, Wellington CL. ABCG1 influences the brain cholesterol biosynthetic pathway but does not affect amyloid precursor protein or apolipoprotein E metabolism in vivo. J Lipid Res. 2008;49:1254–1267. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M700481-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yvan-Charvet L, Welch C, Pagler TA, Ranalletta M, Lamkanfi M, Han S, Ishibashi M, Li R, Wang N, Tall AR. Increased inflammatory gene expression in ABC transporter-deficient macrophages: free cholesterol accumulation, increased signaling via toll-like receptors, and neutrophil infiltration of atherosclerotic lesions. Circulation. 2008;118:1837–1847. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.793869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bjorkhem I, Diczfalusy U. Oxysterols: friends, foes, or just fellow passengers? Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2002;22:734–742. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.0000013312.32196.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nishio E, Watanabe Y. Oxysterols induced apoptosis in cultured smooth muscle cells through CPP32 protease activation and bcl-2 protein downregulation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;226:928–934. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.1452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.