ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND

Young adults have a high prevalence of many preventable diseases and frequently lack a usual source of ambulatory care, yet little is known about their use of the emergency department.

OBJECTIVE

To characterize care provided to young adults in the emergency department.

DESIGN, SETTING, AND PARTICIPANTS

Cross-sectional analysis of visits from young adults age 20 to 29 presenting to emergency departments (N = 17,048) and outpatient departments (N = 14,443) in the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey and National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey.

MAIN MEASURES

Visits to the emergency department compared to ambulatory offices.

RESULTS

Emergency department care accounts for 21.6% of all health care visits from young adults, more than children/adolescents (12.6%; P < 0.001) or patients 30 years and over (8.3%; P < 0.001). Visits from young adults were considerably more likely to occur in the emergency department for both injury-related and non-injury-related reasons compared to children/adolescents (P < 0.001) or older adults (P < 0.001). Visits from black young adults were more likely than whites to occur in the emergency department (36.2% vs.19.2%; P < 0.001) rather than outpatient offices. The proportion of care delivered to black young adults in the emergency department increased between 1996 and 2006 (25.9% to 38.5%; P = 0.001 for trend). In 2006, nearly half (48.5%) of all health care provided to young black men was delivered through emergency departments. The urgency of young adult emergency visits was less than other age groups and few (4.7%) resulted in hospital admission.

CONCLUSIONS

A considerable amount of care provided to young adults is delivered through emergency departments. Trends suggest that young adults are increasingly relying on emergency departments for health care, while being seen for less urgent indications.

Key words: emergency care, ambulatory care, young adults

INTRODUCTION

Young adults represent a generally healthy population, yet their mortality rate is over twice that of adolescents and they have the highest rates of many preventable diseases.1–3 The rates of substance abuse, sexually transmitted illnesses, homicide, and motor vehicle accidents all peak in young adulthood.2 Additionally, young adults face triple the suicide rate of adolescents and have considerably higher rates of tobacco use, binge drinking, and illicit drug use.2,3

Despite preventable risks, young adults frequently lack a usual source of ambulatory care and infrequently receive preventive care aimed at the greatest threats to their health.4,5 Young adults are the most likely age group to lack health insurance, further hindering access to care and contributing to delayed treatments.4,6 The US Department of Health and Human Services established several national objectives through Healthy People 2010 aimed at improving access to care, reducing preventable diseases, and reducing mortality in young adults, yet little progress has been made.7,8

Determining where young adults access care is necessary to effectively implement policies to obtain these objectives. Little is known about young adults’ use of emergency departments, a setting in which they are not likely to receive routine preventive care. Several recent reports have highlighted the overcrowding, underfunding, and fragmentation of care faced by emergency departments,9,10 emphasizing the need to ensure appropriate use of resources and access to ambulatory care.

A comprehensive understanding of young adults’ use of emergency care is essential towards focusing evolving policy initiatives aimed at improving health care for this population. We used data from the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NAMCS) and National Hospital Ambulatory Care Survey (NHAMCS) between the years 1996–2006 to characterize the utilization of emergency department care by young adults age 20 to 29 in the United States. Our objectives were to examine emergency department utilization by young adults in relation to their use of ambulatory services, compare utilization to other age groups, describe trends in utilization over time, and evaluate the urgency of emergency department visits.

METHODS

Data Source

NHAMCS is a national cross-sectional survey of patient visits to emergency departments and outpatient departments located in general and short-stay hospitals.11 Similarly, NAMCS is a national survey of patient visits to office-based physicians.12 NHAMCS and NAMCS provide nationally representative data on the utilization and provision of ambulatory and emergency care in the United States but do not include visits to family planning centers, college or school based clinics.11,12 Both surveys employ a multistage probability design to select a stratified systematic sample of patient visits.11,12 NHAMCS uses a four-stage sampling design based on geographic areas, hospitals within these geographic areas, emergency departments and clinics within the hospital, and patients visits to these departments.11 NAMCS utilizes a three-stage sampling design based on geographic region, physician practices within these geographic areas, and patient visits to these practices.12 We used visit weights provided by NAMCS and NHAMCS to extrapolate to national estimates of utilization of ambulatory and emergency medical services.11,12

NAMCS and NHAMCS are both conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) with the U.S. Bureau of the Census acting as the field agents for data collection. Field representatives performed checks for data completeness and, when necessary, missing data were imputed by the NCHS based on physician specialty, geographic region, and primary diagnosis. A comprehensive explanation of the methods used for data collection, sampling, weighting, data imputation, and adjustment for physician non-response are available online at http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/ahcd.htm.

Study Design and Variable Creation

Our primary analyses focused on data from 2004 to 2006. All data presented are from 2004 to 2006 unless otherwise noted. To assess trends in utilization, we used data from 1996 to 2006.

We defined young adults as those between 20 and 29 years of age based on prior studies and because it represents a time period when many young adults lose their health insurance.5,6,13 We also re-ran key analyses defining young adults as 18 to 24 years of age to ensure that our findings were not dependent on the definition of young adult. To allow for gender comparisons, we excluded visits related to pregnancy.

To describe the chief complaints of young adults presenting to the emergency department, we grouped visits into general categories (e.g. injury, respiratory) based on classifications provided by NAMCS/NHAMCS and then present the three most common specific reasons for visits within each category.11,12 Reason for visit (RFV) codes were grouped, where clinically appropriate, to combine similar presenting complaints (e.g. we combined all lacerations into one category). In the tabulation, we provide a description of the presenting complaint along with the specific RFV codes.

We assessed the urgency of visits using the immediacy with which the patient should be seen, as assigned at triage, and the percent of visits resulting in either admission to the hospital or to an observation unit, consistent with prior studies.14,15

Analysis

We performed all statistical analyses using SAS version 9.1 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) and SAS callable SUDAAN (Research Triangle Institute, Research Triangle Park, NC, USA) to appropriately weight visits and account for the complex sampling design. We used χ2 test statistics to compare all proportions. All tests were two-tailed with P < 0.05 used to determine statistical significance.

We compared the proportion of total care that was delivered in the emergency department versus the ambulatory setting for young adults and other age groups (ED visits/total ED and ambulatory visits). We then used logistic regression to compare care delivered in the emergency department vs. ambulatory setting by age group (young adults (20–29 yrs) vs. children/adolescent (0–19 yrs) or older adults (≥30 yrs)) while controlling for potential confounders. To account for injury status, we developed separate logistic regression models for injury-related and non-injury-related visits. Based on established variables in NAMCS and NHAMCS, we defined an injury-related visit as any visit related to an injury, poisoning, or adverse effect of medical treatment. Based on prior literature and clinical significance,16 we included race, ethnicity, sex, insurance status, region of the county, metropolitan status (metropolitan sampling area or not), season, and day of week (weekend or weekday) when constructing the model.

Among young adults, we compared the proportion of care delivered in the emergency department across pre-specified demographic variables. We subsequently used logistic regression, stratified by injury status, to further compare care delivered in the emergency department vs. ambulatory setting by race while controlling for potential confounders, as above.

Finally, we used logistic regression models to assess trends in care delivered in the emergency department vs. ambulatory setting between 1996 and 2006. We tested our model to ensure that year functioned as a linear variable on the logit scale by examining odds ratio between each concurrent year for young adults. We developed separate models for different racial, ethnic, and age groups. We report p-values associated with beta coefficients on the logit scale for the trend in ED visits over the years studied. For ease of interpretation, we report proportion of care delivered in the ED over the years studied.

The NCHS employs strict release standards based on the relative standard error of the point estimate (greater than 30% considered unreliable) and the absolute number of visits (less than 30 considered unreliable).11,12 All values reported meet the established release criteria for national estimates.

This study was approved by the University of Rochester Research Subjects Review Board and the protocols used by NAMCS were approved by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) Institutional Review Board.17

RESULTS

Between 2004 and 2006, a total of 4,108 physicians participated in NAMCS (66% participation rate). During this same time period, a total of 714 emergency departments (89% participation) and 642 hospital-based outpatient departments (83.6% participation) encompassing 1,895 clinics (84.9% participation) participated in NAMCS. Table 1 reports unweighted and weighted characteristics of the data.

Table 1.

Visits from Young Adults age 20–29 Recorded in the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NAMCS) and the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NHAMCS) between 2004 and 2006

| Unweighted Visits | Weighted Visits (k) (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Total | 31,491 | 263,044 |

| Ambulatorya | 14,443 | 206,198 (78.4%) |

| EDb | 17,048 | 56,846 (21.6%) |

| Gender | ||

| Women | 19,501 | 170,368 (64.8%) |

| Men | 11,990 | 92,676 (35.2%) |

| Race | ||

| White | 22,933 | 213,282 (81.1%) |

| Black | 7,078 | 38,948 (14.8%) |

| Asian | 880 | 7,523 (2.9%) |

| Otherc | 600 | 3,292 (1.2%) |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Hispanicd | 5,534 | 35,701 (13.6%) |

| Metropolitan | ||

| Urban | 28,136 | 229,622 (87.3%) |

| Non-urban | 3,355 | 33,422 (12.7%) |

| Region | ||

| Northeast | 8,407 | 49,558 (18.8%) |

| Midwest | 6,851 | 64,374 (24.5%) |

| South | 10,287 | 99,564 (37.9%) |

| West | 5,946 | 49,547 (18.8%) |

| Insurance | ||

| Private | 11,637 | 147,737 (56.2%) |

| Public | 8,519 | 43,902 (16.7%) |

| Uninsurede | 7,333 | 39,212 (14.9%) |

| Otherf | 4,002 | 32,193 (12.2%) |

Number of visits with percentage of visits in parentheses. K indicates thousands of visits

aAmbulatory data are from NAMCS and the outpatient portion of NHAMCS

bEmergency department data are from the emergency department portion of NHAMCS

cIncludes Native Hawaiian, American Indian, Alaskan Native, and more than one race

dHispanic ethnicity, any race

eIncludes charity care, no charge, and self-pay

fIncludes worker’s compensation, other forms of payment, and unknown source of expected payment

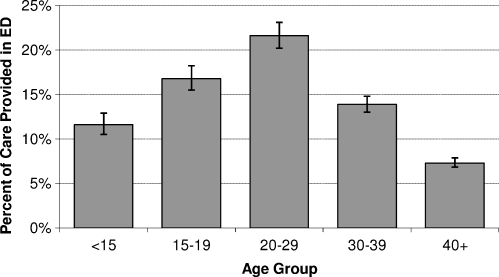

Emergency Department Use

Figure 1 demonstrates the percent of all care that was delivered in the emergency department to different age groups. Visits from young adults were considerably more likely to occur in the emergency department compared to other ages (Fig. 1; P < 0.001 for all comparisons to young adults). Compared to children and adolescents, visits from young adults were more likely to occur in the emergency department for both injury-related (45.3% vs. 35.9%; AOR 1.2, 95% CI 1.1–1.4) and non-injury-related reasons (16.2% vs. 8.9%; AOR 2.0, 95% CI 1.8–2.2). Compared to adults 30 years and over, visits from young adults in their 20s were also more likely to occur in the emergency department for injury-related (45.3% vs. 23.8%; AOR 2.4, 95% CI 2.1–2.7) and for non-injury-related reasons (16.2% vs. 6.2%; AOR 2.8, 95% CI 2.5–3.0).

Figure 1.

Percent of Total Care Delivered in the Emergency Department by Age Group in the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NAMCS) and the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NHAMCS) between 2004 and 2006. *P < 0.001 for all comparisons to young adults (20–29 years/old).

Tables 2 shows the percent of care delivered in the emergency department to young adults with different demographic characteristics for both injury-related and non injury-related visits. Young adult men received less care overall and more of their total care in the emergency department compared to young women for non-injury related complaints. A greater proportion of care was delivered to black young adults in the emergency room compared to whites for both non-injury related and injury-related reasons. Further, visits from young adults without insurance or with public insurance were more likely to occur in the ED than young adults with private insurance.

Table 2.

Percent of Total Care Delivered in the Emergency Department to Young Adults Age 20–29 in the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NAMCS) and the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NHAMCS) between 2004 and 2006

| Characteristic | Outpatient Visits (k) | ED Visits (k) | %ED (CI) | Pa | Adjusted OR (CI)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Injury Related Visit | |||||

| Total | 179,355 | 34,599 | 16.2 (14.9–17.5) | ||

| Gender | <0.001 | ||||

| Women | 125,788 | 22,727 | 15.3 (14.0–16.7) | 1.0 | |

| Men | 53,567 | 11,872 | 18.1 (16.6–19.8) | 1.3 (1.1–1.5) | |

| Race | <0.001 | ||||

| White | 148,605 | 23,797 | 13.8 (12.6–15.1) | 1.00 | |

| Black | 22,673 | 9,601 | 29.8 (26.4–33.3) | 2.4 (2.0–2.8) | |

| Asian | 5,926 | 618 | 9.5 (7.3–12.1) | 0.6 (0.4–0.8) | |

| Otherc | 2,151 | 583 | 21.3 (15.7–28.3) | 1.5 (0.9–2.4) | |

| Ethnicity | 0.21 | ||||

| Non-Hispanic | 155,935 | 29,628 | 16.0 (14.6–17.4) | 1.0 | |

| Hispanicd | 23,420 | 4,971 | 17.5 (15.4–19.9) | 1.0(0.8–1.2) | |

| Insurance | <0.001 | ||||

| Private | 115,579 | 11,178 | 8.8 (7.9–9.8) | 1.0 | |

| Public | 27,575 | 9,318 | 25.3 (22.4–28.4) | 3.2 (2.6–3.9) | |

| Uninsurede | 18,881 | 10,783 | 36.4 (32.3–40.7) | 5.5 (4.5–6.8) | |

| Otherf | 17,320 | 3,320 | 16.1 (12.8–20.0) | 1.8 (1.4–2.4) | |

| Metropolitang | 0.51 | ||||

| Urban | 157,622 | 29,905 | 16.0 (14.7–17.3) | 1.0 | |

| Non-urban | 21,733 | 4,694 | 17.8 (13.1–23.7) | 1.0 (0.6–1.5) | |

| Region | 0.07 | ||||

| Northeast | 34,305 | 6,246 | 15.4 (12.8–18.4) | 1.0 | |

| Midwest | 44,196 | 8,523 | 16.2 (13.6–19.1) | 1.2 (0.9–1.7) | |

| South | 66,746 | 14,415 | 17.8 (15.6–20.2) | 1.2 (0.9–1.5) | |

| West | 34,108 | 5,415 | 13.7 (11.9–15.8) | 1.1 (0.8–1.5) | |

| Day | <0.001 | ||||

| Weekday | 174,932 | 25,269 | 12.6(11.6–13.7) | 1.0 | |

| Weekend | 4,423 | 9,330 | 67.8 (60.9–74.1) | 14.7 (11.1–19.6) | |

| Season | 0.11 | ||||

| Winter | 41,281 | 9,035 | 18.0 (15.1–21.3) | 1.0 | |

| Spring | 51,720 | 8,371 | 13.9 (11.9–16.2) | 0.8 (0.6–1.1) | |

| Summer | 42,191 | 8,708 | 17.1 (14.5–20.1) | 1.2 (0.8–1.6) | |

| Fall | 44,163 | 8,485 | 16.1 (13.4–19.2) | 0.9 (0.6–1.2) | |

| Injury-Related Visit | |||||

| Total | 26,842 | 22,247 | 45.3 (42.2–48.5) | ||

| Gender | 0.72 | ||||

| Women | 12,047 | 9,807 | 44.9 (41.2–48.6) | 1.0 | |

| Men | 14,796 | 12,440 | 45.7 (41.8–49.6) | 1.1 (0.9–1.3) | |

| Race | <0.001 | ||||

| White | 23,762 | 17,118 | 41.9 (38.6–45.3) | 1.0 | |

| Black | 2,162 | 4,511 | 67.6 (61.1–76.5) | 2.5 (1.7–3.5) | |

| Asian | 609 | 369 | 37.8 (23.2–55.0) | 0.9 (0.4–1.7) | |

| Other c | 310 | 249 | 44.5 (26.0–64.7) | 0.9 (0.3–2.7) | |

| Ethnicity | 0.94 | ||||

| Non-Hispanic | 22,829 | 18,951 | 45.4 (42.0–48.8) | 1.0 | |

| Hispanicd | 4,014 | 3,296 | 45.1 (39.0–51.4) | 1.0 (0.7–1.4) | |

| Insurance | <0.001 | ||||

| Private | 13,872 | 7,108 | 33.9 (29.9–38.1) | 1.0 | |

| Public | 3,088 | 3,922 | 56.0 (49.1–62.6) | 2.4 (1.7–3.3) | |

| Uninsurede | 2,339 | 7,209 | 75.5 (67.8–81.9) | 5.2 (3.3–8.0) | |

| Otherf | 7,544 | 4,008 | 34.7 (29.0–40.9) | 1.1 (0.8–1.5) | |

| Metropolitang | 0.83 | ||||

| Urban | 22,958 | 19,137 | 45.5 (42.1–48.9) | 1.0 | |

| Non-urban | 3,885 | 3,110 | 44.5 (36.5–52.7) | 1.0 (0.6–1.5) | |

| Region | 0.20 | ||||

| Northeast | 4,563 | 4,445 | 49.3(42.7–56.0) | 1.0 | |

| Midwest | 6,631 | 5,025 | 43.1 (38.2–48.2) | 0.8 (0.5–1.1) | |

| South | 9,660 | 8,742 | 47.5 (41.6–53.5) | 0.8 (0.5–1.1) | |

| West | 5,989 | 4,035 | 40.3 (33.8–47.1) | 0.7 (0.5–1.1) | |

| Day | <0.001 | ||||

| Weekday | 25,741 | 15,222 | 37.2 (34.3–40.1) | 1.0 | |

| Weekend | 1,102 | 7,025 | 86.5 (80.4–90.8) | 9.9 (6.4–15.4) | |

| Season | 0.62 | ||||

| Winter | 6,100 | 5,029 | 45.2 (37.5–53.1) | 1.0 | |

| Spring | 7,694 | 5,520 | 41.8 (35.9–47.9) | 0.9 (0.6–1.3) | |

| Summer | 6,997 | 6,229 | 47.1 (40.7–53.6) | 1.2 (0.8–1.7) | |

| Fall | 6,052 | 5,469 | 47.5 (40.5–54.6) | 1.1 (0.7–1.6) | |

aChi square

bAdjusted for sex, race, ethnicity, insurance, and whether the visit was related to an injury, poisoning, or adverse effect of a medical treatment

cHispanic ethnicity, any race

dIncludes Native Hawaiian, American Indian, Alaskan Native, more than one race

eIncludes charity care, no charge, and self-pay

fIncludes worker’s compensation, other forms of payment, and unknown source of expected payment

gMetropolitan indicates metropolitan sampling area

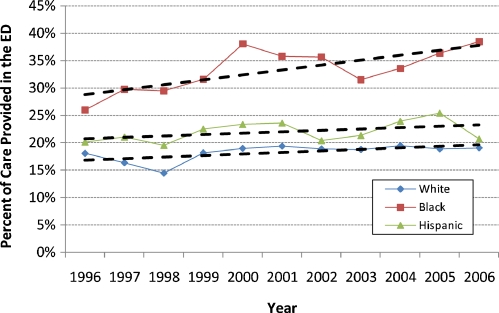

Trends in Emergency Department Use

The proportion of health care delivered to young adults in the emergency department increased from 19.1% in 1996 to 21.1% in 2006 (P = 0.005 for trend) while the proportion of care delivered in the emergency department remained stable for children and adolescents (13.0% in 1996 to 12.1% in 2006; P = 0.46 for trend) and patients 30 years and over (8.3% in 1996 to 9.0% in 2006; P = 0.92 for trend). The proportion for black young adults increased from 25.9% in 1996 to 38.5% in 2006 (P = 0.001 for trend) (Fig. 2). This rising trend was a result of both decreasing ambulatory utilization (9.92 million visits in 1996 to 8.83 million visits in 2006) and increasing utilization of the emergency department by black young adults (3.48 million in 1996 to 5.53 million visits in 2006). The trend was most pronounced in young black men with the proportion of care received in the emergency department rising from 35.4% in 1996 to 48.5% in 2006 (P = 0.03 for trend). Again, this rising trend was a result of both decreasing ambulatory utilization (2.80 million visits in 1966 to 2.26 million visits in 2006) and increasing utilization of the emergency department (1.54 million in 1966 to 2.13 million visits in 2006).

Figure 2.

Percent of Total Care Delivered in the Emergency Department (ED) to Young Adults age 20–29 in the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NAMCS) and the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NHAMCS). \ Hispanic ethnicity includes any race. † All young adults P = 0.005 for trend; Black P = 0.001 for trend; White P = 0.08 for trend; Hispanic P = 0.40 for trend; Children and adolescents P = 0.46 for trend (data not shown); Adults ≥30 P = 0.92 for trend (data not shown). All P-values obtained using logistic regression models to assess trends in care delivered in the ED vs. ambulatory setting with year as the independent variable.

Urgency of Emergency Department Visits

Visits to the emergency department by young adults were half as likely as other age groups to be triaged as immediate/emergent (less than 15 minutes; 11.3% vs. 5.4%; P < 0.001) and were more likely to be triaged less acutely (1–2 hours; 23.6% vs. 21.1%; P < 0.001) or nonurgently (15.9% vs. 12.3%; P < 0.001). Young adult visits to the emergency department were less likely to result in admission than other age groups (4.7% vs. 14.3%; P < 0.001) and were less likely to be monitored in observation units in the emergency department (0.4% vs. 0.9%; P < 0.001). Rates of admission to the hospital among young adults did not vary by gender (P = 0.2), race (P = 0.8), or ethnicity (P = 0.4).

Reasons for Emergency Department Visits

Table 3 describes the general categories of presenting complaints and lists the three most common reasons for visits per category. Young adults were most commonly seen for injury related visits (19.4% of visits).

Table 3.

Reasons for Emergency Department Visits from Young Adults age 20–29 and Most Common Complaints for each Category in the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NHAMCS) between 2004 and 2006

| Reasons for Visitsa | Percent of Visits |

|---|---|

| Injury | 19.4% |

| General or unspecific injury (55050 – 55750) | 5.5% |

| Laceration (51050 – 52300) | 4.5% |

| Motor vehicle accident (58050) | 2.4% |

| Gastrointestinal | 17.5% |

| Abdominal pain (15450 – 15453) | 9.6% |

| Nausea / Vomiting (15250, 15300) | 3.4% |

| Toothache (15001) | 2.5% |

| Musculoskeletal | 14.5% |

| Back pain (19050 – 19053; 19100 – 19101) | 5.0% |

| Neck symptoms (19000–19005) | 1.4% |

| Finger symptoms (19600–19603) | 1.4% |

| General complaint | 11.2% |

| Chest pain, excluding heart pain (10500 – 10503) | 3.8% |

| Rib or side pain (10551 – 10552) | 2.0% |

| Fever (10100) | 1.3% |

| Respiratory | 9.1% |

| Sore throat, cold, flu symptoms, nasal congestion (14550–14552; 14501, 14000) | 4.0% |

| Cough or sputum (14400, 14703) | 1.9% |

| Shortness of breath or dyspnea (14150,14200) | 1.8% |

| Neurology | 7.0% |

| Headache and migraine (12100, 23650) | 4.5% |

| Dizziness (12250) | 1.0% |

| Seizure (12050) | 0.7% |

| Genitourinary | 5.6% |

| Vaginal bleeding, metrorrhagia (17550, 17551) | 1.6% |

| Dysuria, increase frequency, urgency (16450, 16500) | 1.0% |

| Vaginal discharge, pain, itching (17600–17653) | 0.6% |

| Dermatology | 4.2% |

| Mental health | 2.8% |

| Otherb | 8.7% |

aNHAMCS reason for visit classification codes in parentheses

bOther includes visits related to infectious disease, cardiology, otolaryngology, blood disorders, endocrine disorders, social problems, other

Variable Definition

Defining young adult as adults age 18 to 24 did not change our key findings. Visits from young adults age 18–24 remained considerably more likely to occur in the emergency department compared to other children/adolescents (23.7 vs. 12.0; P < 0.001) or older adults (23.7 vs. 8.9; P < 0.001).

DISCUSSION

Young adults have the highest rates of many preventable conditions,2,3,18 yet frequently lack a consistent source of ambulatory care.4,6 This study demonstrates that a considerable proportion of care delivered to young adults, especially black and uninsured young adults, occurs in the emergency department, greater than any other age group. Moreover, the use of the emergency department by young adults is increasing, suggesting that the current trends will likely progress without significant policy transformation.

Previous studies have suggested that adolescents overutilize emergency care,15 but this is the first study to examine emergency department utilization and trends by young adults. Visits from young adults were considerably more likely to occur in the emergency department rather than in an outpatient office setting compared to other ages, including adolescents. This finding likely represents a combination of relative overutilization of emergency services and underutilization of primary care. Young adults’ reliance on the emergency department is likely driven by many factors including lack of insurance, limited preventive care, inadequate transition of care between providers, and a lack of a usual source of primary care.4–6 We found that visits from uninsured patients were more likely than privately insured patients to occur in the emergency department, but this did not entirely account for young adults’ increased use of the emergency department. After accounting for young adults’ insurance status, injury status, and demographic factors, care continued to be considerably more likely to occur in the emergency department compared to other age groups, emphasizing the need to ensure access to a usual source of primary care.

Nearly half of all care provided to young black men in 2006 was delivered through emergency departments, considerably more than white young adults. Medical care was more likely to be delivered in the emergency department for both non-injury and injury-related complaints. Over the past decade, the number of ambulatory visits from black young adults has declined while the use of emergency services has increased. Black young adults’ greater use of the emergency department for health care may be related to several factors including barriers in accessing primary care, disparities in preventive care services, or inequalities in preventive counseling and health education.4,5,19 Improving access to appropriate ambulatory health care services with a consistent and culturally competent care provider could potentially help reduce disparities and improve overall health outcomes in young adults.

During a time when emergency departments are over-burdened,9,10 our results suggest that young adults, especially young black men, are becoming increasingly dependent on the emergency department for health care. While the use of the emergency department is certainly appropriate for many injuries and urgent medical complaints, we found that young adult visits were triaged as less urgent and required lower rates of admission to the hospital than other age groups, implying that ambulatory services would suffice for at least a portion of these visits. While young adults’ use of emergency care represents a small fraction of overall care provided by emergency departments, potential overuse has cost implications and places burdens on emergency departments while hindering continuity of care. Future initiatives, however, should focus on improving primary care for young adults, rather than limiting young adults’ access to emergency care.

Access to a usual source of primary care is associated with many improved health outcomes and lower rates of preventable hospitalizations and ED use.20,21 Improving access to primary care for young adults will require a multifaceted approach including improving transitions between providers, expanding health care coverage, and increasing awareness about the importance of a usual source of care. Historically, inadequate emphasis has been placed on ensuring adequate transition of care between pediatric and adult-focused providers,22–25 leaving many patients without a usual source of care as they become young adults.4 Additionally, transition of care often occurs at a time when many young adults lose health insurance coverage, further hindering access to care. Further advocacy is needed to support continuity of care across the transition into adulthood and to work towards expanding health care coverage. The Commonwealth Fund has proposed several potential options and policies to extend health coverage to young adults.6,26–28 Additionally, several states have adopted measures to extend coverage and several federal bills have been proposed,29–33 but tangible measures have yet to take hold nationally.

The use of NAMCS and NHAMCS data has several limitations. First, NAMCS and NHAMCS are visit-based, not person-based, and do not include visits to family planning centers, college or school based clinics, potentially leading to a small underestimation in the total amount of ambulatory care provided to young adults and an overestimation in the proportion of care received in the emergency department. In contrast, racial differences in college enrollment may lead to an underestimation of the disparity in utilization found in our analyses. Overall, the majority of health visits to college clinics occur at an age less than twenty-two, likely minimizing the effect on our analyses. Second, appropriateness of ED care is intrinsically very difficult to adequately measure. Our analyses concerning the acuity of emergency department visits were based on urgency at triage and hospital admission rates, similar to other studies.14,15 While these measures are imperfect and do not necessarily equate to appropriateness of ED visits, they do provide basic surrogate measures of acuity. Lastly, we do not have data on patients’ past medical history, health status, or whether a patient has an established primary care physician.

CONCLUSIONS

A considerable amount of care provided to young adults in the United States is delivered through emergency departments. Trends further suggest that young adults are increasingly relying on emergency departments for health care while being seen for less urgent indications. Emergency care of young adults is a vital component of overall healthcare, but ensuring adequate access to primary care remains essential towards improving health outcomes among young adults. Efforts to improve access to care for young adults will require a multifaceted approach aimed at expanding insurance coverage for young adults, facilitating adequate transitions between pediatric and adult providers, and ensuring a usual source of ambulatory care.

Acknowledgements

Dr. Fortuna received support from the Center for Primary Care, University of Rochester. The authors thank the Center for Primary Care for support of this project.

Conflict of Interest None disclosed.

References

- 1.Sexually transmitted disease surveillance 2007. Atlanta: U.S.Department of Health and Human Services; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Park MJ, Paul MT, Adams SH, Brindis CD, Irwin CE., Jr The health status of young adults in the United States. J Adolesc Health. 2006;39:305–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2008). Results from the 2007 National survey on drug use and health: National findings. Rockville, MD, Office of Applied Studies, NSDUH Series H-34, DHHS Publication No. SMA 08-4343.

- 4.Callahan ST, Cooper WO. Uninsurance and health care access among young adults in the United States. Pediatrics. 2005;116:88–95. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fortuna RJ, Robbins BW, Halterman JS. Ambulatory care among young adults in the United States. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:379–85. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-6-200909150-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kriss JL, Collins SR, Mahato B, Gould E, Schoen C. Rite of passage? Why young adults become uninsured and how new policies can help, update. The Commonwealth Fund. 38, 1-24. New York, NY; 2008. [PubMed]

- 7.Park MJ, Brindis CD, Chang F, Irwin CE., Jr A midcourse review of the healthy people 2010: 21 critical health objectives for adolescents and young adults. J Adolesc Health. 2008;42:329–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Healthy People 2010: Understanding and improving health. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hospital-based emergency care: At the breaking point. Washington: The National Academies Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kellermann AL. Crisis in the emergency department. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1300–3. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp068194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Center for Health Statistics. NCHS public-use data files and documentation: National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NHAMCS). Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/ahcd/ahcd_questionnaires.htm. Last Accessed 2-4-2010.

- 12.National Center for Health Statistics. NCHS public-use data files and documentation: National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NAMCS). Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/ahcd/ahcd_questionnaires.htm. Last Accessed 2-4-2010.

- 13.Preventive care of adults ages 19 years and older. Rochester Community Practice Guideline. Monroe County Medical Society: Rochester; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hostetler MA, Auinger P, Szilagyi PG. Parenteral analgesic and sedative use among ED patients in the United States: combined results from the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NHAMCS) 1992-1997. Am J Emerg Med. 2002;20:83–7. doi: 10.1053/ajem.2002.31578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ziv A, Boulet JR, Slap GB. Emergency department utilization by adolescents in the United States. Pediatrics. 1998;101:987–94. doi: 10.1542/peds.101.6.987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pitts SR, Niska RW, Xu J, Burt CW. National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2006 emergency department summary. Natl Health Stat Report 2008;1-38. [PubMed]

- 17.National Center for Health Statistics Institutional Review Board. Protocol #2003-05 National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey. http://www.cdc.gov/namcs/data/akin2.pdf, 2-12-2003. Department of Health and Human Services, National Center for Health Statistics. 11-28-2007.

- 18.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies. The NSDUH Report: Treatment for Past Year Depression among Adults. 1-3-2008. Rockville, MD.

- 19.Callahan ST, Hickson GB, Cooper WO. Health care access of Hispanic young adults in the United States. J Adolesc Health. 2006;39:627–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.How is a shortage of primary care physicians affecting the quality and cost of medical care? White Paper. Philadelphia: American College of Physician; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Richman I, Clark S, Sullivan A, Catalano J. National study of thee relation of primary care shortages to emergency department utilization. Acad Emerg Med. 2007;14:279–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2007.tb01788.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.A consensus statement on health care transitions for young adults with special health care needs. Pediatrics. 2002;110:1304-1306. [PubMed]

- 23.Reiss JG, Gibson RW, Walker LR. Health care transition: youth, family, and provider perspectives. Pediatrics. 2005;115:112–20. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McDonagh JE, Viner RM. Lost in transition? Between paediatric and adult services. BMJ. 2006;332:435–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.332.7539.435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reiss J, Gibson R. Health care transition: destinations unknown. Pediatrics. 2002;110:1307–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Collins SR. Rising numbers of uninsured young adults: Causes, consequences, and new policies. Committee on Oversight and Government Reform, United States House of Representatives, Subcommittee on Federal Workforce, Postal Service, and the District of Columbia; 4-29-2008.

- 27.Davis K, Schoen C. Putting the U.S. health system on the path to high performance. Committee on Ways and Means, U.S. House of Representatives; 3-11-2009.

- 28.Schoen C. The Commonwealth Fund Commission on a High Performance Health System, The path to a high performance U.S. Health System: A 2020 Vision and the Policies to Pave the Way. The Commonwealth Fund; 2-19-2009.

- 29.Collins SR, Nicholson JL, Rustgi SD. An analysis of leading congressional health care bills, 2007-2008: Part I, Insurance Coverage. Commonwealth Fund 2009;1223:1-114.

- 30.Curtis R, Neuschler E. Affording shared responsibility for universal coverage: Insights from California. Health Aff (Millwood); 2009. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Davis K. Uninsured in America: problems and possible solutions. BMJ. 2007;334:346–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39091.493588.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Davis K. Universal coverage in the United States: lessons from experience of the 20th century. J Urban Health. 2001;78:46–58. doi: 10.1093/jurban/78.1.46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Long SK. On the road to universal coverage: impacts of reform in Massachusetts at one year. Health Aff (Millwood) 2008;27:w270–84. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.4.w270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]