History and Physical Examination

A 17-year-old girl presented with a 1-month history of right knee pain after repeated strenuous martial art training. She had no medical history. Point tenderness during palpation of the posteromedial aspect of the knee was noted. The rest of the physical examination was within normal limits and laboratory data were entirely normal.

Radiography (Fig. 1), ultrasound (Fig. 2), MRI (Fig. 3), and CT (Fig. 4) of the right knee were performed.

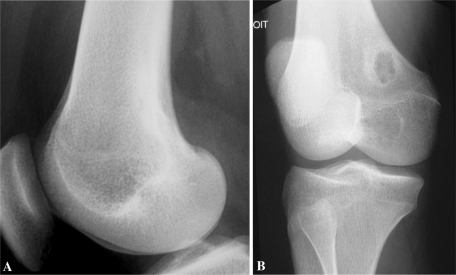

Fig. 1A–B.

(A) A lateral radiograph of the knee shows a cortically based lucency of the posteromedial aspect of the medial femoral condyle. (B) On the oblique view, the lesion appears well limited by a sclerotic rim.

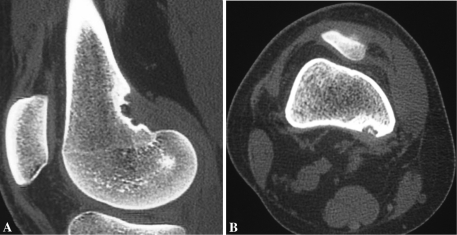

Fig. 2.

The ultrasound showed a juxtacortical mass responsible for cortical erosion.

Fig. 3A–C.

Sagittal (A) T1- and (B) T2-weighted MR images and (C) an axial fat-saturated T1-weighted MR image after gadolinium injection show a cortical lesion of the medial femoral condyle at the origin of the medial head of the gastrocnemius muscle. The lesion appears hypointense on (A) T1-weighted and (B) T2-weighted images (C) with a marked enhancement after contrast injection. A dark rim surrounding the lesion is evident.

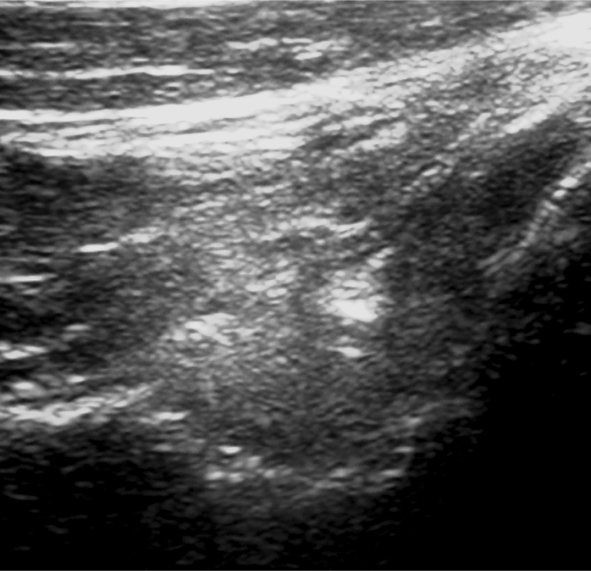

Fig. 4A–B.

(A) Sagittal and (B) axial two-dimensional CT scan reformats show cortical erosion at the origin of the medial head of the gastrocnemius muscle. (A, B) Spiculations of the cortical margin and (B) small calcifications are seen in the lesion.

Based on the history, physical examination, laboratory studies, and imaging studies, what is the differential diagnosis?

Imaging Interpretation

A lateral radiograph of the knee (Fig. 1A) showed an area of cortically based lucency with sclerotic margins along the posteromedial margin of the distal femoral metaphysis. On the oblique view (Fig. 1B), the lesion was well limited and surrounded by a sclerotic margin.

Ultrasound investigation (Fig. 2A) showed an oval-shaped soft tissue mass of heterogeneous echotexture associated with an erosion of the posteromedial femoral cortex. The patient had point tenderness in response to transducer pressure in this area.

Because of cortical erosion, MRI was performed and showed a 3- × 2-cm lesion with low signal intensity on spin echo T1-weighted (Fig. 3A) and T2-weighted (Fig. 3B) images at the right medial gastrocnemius origin. There was marked enhancement after intravenous gadolinium administration (Fig. 3C). There was neither medullar involvement nor soft tissue edema.

CT scans revealed erosion and cortical irregularity at the origin of the medial head of the gastrocnemius muscle (Fig. 4). Spiculations of the cortical margin and small calcifications were seen in the mass (Fig. 4B).

Differential Diagnosis

Periosteal osteosarcoma

Fibrous cortical defect

Stress fracture

Periosteal osteoid osteoma

Avulsive cortical irregularity

Cortical infection

Based on the history, physical examination, laboratory studies, and imaging studies, what is the diagnosis and how should the patient be treated?

Diagnosis

Avulsive cortical irregularity

Discussion and Treatment

The history, the typical location on the posteromedial margin of the distal femoral metaphysis where the medial head of the gastrocnemius muscle originates, and the imaging findings were consistent with avulsive cortical irregularity.

The differential diagnosis includes fibrous cortical defect, stress fracture, infection, periosteal osteoid osteoma, and periosteal osteosarcoma [2, 6]. A cortical defect is a benign intracortical focus of fibrous tissue. This lesion is extremely common; almost 1/3 of children will have one or more of this lesion develop. The lesion begins in a metaphyseal location but may extend into the diaphysis with skeletal growth. It appears as an oblong radiolucent focus. With time, a well-defined border of sclerosis will develop. In most instances, the lesion will regress, filling in with bone from the periphery to the center [11]. Stress fractures also can be seen in patients with strenuous physical activity. The midtibial shaft is a typical location. On radiographs, it presents as a thin lucent fracture line with periosteal reaction and cortical thickening [7]. When plain radiographs fail to reveal a fracture, the search for a cortical infraction may be accomplished with either CT or MRI [11]. Infection of the bone surface may result from contiguous spread from the medullary cavity or adjacent soft tissues or direct inoculation during an invasive procedure. Hematogenous inoculation of the bone surface in the absence of medullary involvement is unusual. The radiographic appearance of surface infection is variable. A focal radiolucent area may be seen in the cortex (intracortical abscess). Periosteal new bone may be unilamellar or multilamellar sometimes with a Codman triangle. Subperiosteal collections are best observed with ultrasound and MRI. Infection can be excluded by specific clinical history and laboratory results [11]. With periosteal osteoid osteoma, the patient presents with a specific clinical history: intense pain that is most severe at night. Pain relief usually can be achieved with NSAIDs. The lesion (the nidus) is round to oval, usually measures less than 1 cm in diameter, and occurs in the diaphysis or metaphysis of a bone. The nidus is usually a radiolucent focus but may be calcified to varying degrees. Thin-section CT is best suited to show the nidus [11]. Periosteal osteosarcoma is a surface osteosarcoma and it is mainly chondroblastic. It more often affects young patients (10–25 years old) and the middiaphysis. Radiographically, it presents as a fusiform juxtacortical mass with large cortical erosion and perpendicular periosteal reaction [7].

Avulsive cortical irregularity or cortical desmoid is a benign bone surface lesion first reported in 1951 by Kimmelstiel and Rapp according to Bernasek et al. [1], Bufkin [2], and Resnick and Greenway [10]. This lesion is observed almost exclusively on the posterior aspect of the medial condyle of femur, along the medial ridge of the linea aspera just above the adductor tubercle [2]. This location is the site of origin of the medial head of the gastrocnemius muscle and the transverse fibers of the adductor magnus [6, 10]. Perhaps the most widely accepted cause is a mechanically induced lesion related to an excessive avulsive stress at a site of attachment of a strong muscle [2, 6]. These repeated microavulsions elicit a hypervascular and fibroblastic response, which in turn stimulates added osteoclastic activity and bone resorption [2]. Avulsive cortical irregularity is extremely rare in locations other than the posterior aspect of the medial condyle, but documented cases also have been observed in the humerus, at the insertion of the pectoralis major [2, 6]. Avulsive cortical irregularity is seen mostly during the first and second decades of life [1, 2, 4–7, 10, 13]. The lesion is often bilateral [10, 11, 13]. Although most of these lesions are asymptomatic and discovered incidentally on routine radiographs (obtained for an unrelated reason), the most common symptom is pain that is increased with physical activity and relieved with rest [1, 2, 4].

On true lateral plain radiographs, the lesion usually appears as a shallow concave irregular osteolytic area originating on the surface of the cortex. The lesion is best seen in the slightly oblique position and appears as a round or oval eccentric well-circumscribed osteolytic area. The lesion may be surrounded by a sclerotic margin that indicates the healing phase in the evolution [2]. Radiographs also can show bony spiculation associated with compact mature periosteal proliferation that simulates malignancy [2, 4]. Nuclear bone scintigraphy is normal or shows increased tracer uptake along the lesion site [3]. Ultrasound findings are not well described in the literature. In our patient, ultrasonography showed a hypoechoic mass of adjacent soft tissues with cortical excavation and hyperemia on color Doppler imaging. CT scans allow better appreciation of cortical erosion and periosteal reaction at the origin of the medial head of the gastrocnemius and distal fibers of the adductor magnus. Small fragments of resorbing bone or tiny cortical fragments occasionally are seen in the lesion [8]. MRI shows a juxtacortical lesion with low signal on T1-weighted images and increased signal on T2-weighted images with moderate enhancement after intravenous gadolinium administration [6]. Areas of slightly increased marrow signal on T2-weighted images and marrow enhancement adjacent to the lesion have been described [3, 9, 12].

Histologic examination shows fibroblastic spindle cells that produce large amounts of collagen. Large areas of hyalinization and fibrocartilage and small fragments of bone may be scattered in the fibrous tissue [4, 5].

The diagnosis of avulsive cortical irregularity is based on the history in conjunction with a highly characteristic location and imaging features. In cases with a typical appearance, biopsy is not required. The clinical symptoms usually completely resolve [6, 9]. The radiographic alterations usually involute or leave residual smooth cortical irregularities [1, 4, 7].

Because the imaging characteristics of our patient’s lesion suggested avulsive cortical irregularity, we did not consider a biopsy necessary. The patient’s symptoms resolved completely with nonoperative treatment (analgesics) and rest within 3 weeks of onset. She remained asymptomatic with 2 years of followup.

Footnotes

Each author certifies that he or she has no commercial associations (eg, consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangements, etc) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article.

Each author certifies that his or her institution approved the reporting of this case report, that all investigations were conducted in conformity with ethical principles of research.

This work was performed at the Institut Kassab d’Orthopédie.

References

- 1.Bernasek TL, Sim FH, Wold LE, Beabout JW, Shives TC, Dunitz SJ. Avulsive cortical irregularities. Orthopedics. 1987;10:1423–1425. doi: 10.3928/0147-7447-19871001-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bufkin WJ. The avulsive cortical irregularity. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med. 1971;112:487–492. doi: 10.2214/ajr.112.3.487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Connolly SA, Davies KJ, Connolly LP. Avulsive cortical irregularity and F-18 FDG PET. Clin Nucl Med. 2006;31:87–89. doi: 10.1097/01.rlu.0000196412.26592.b7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dunham WK, Marcus NW, Enneking WF, Haun C. Developmental defects of the distal femoral metaphysis. J. Bone Joint Surg Am. 1980;62:801–806. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Greenspan A, Remagen W. Differential Diagnosis of Tumors and Tumor-like Lesions of Bones and Joints. 2. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott-Raven; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hyman AA, Heiser WJ, Kim SE, Norfray JF. An excavation of the distal femoral metaphysis: a magnetic resonance imaging study. A case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1995;77:1897–1901. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199512000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kenan S, Abdelwahab IF, Klein MJ, Hermann G, Lewis MM. Lesions of juxtacortical origin (surface lesions of bone) Skeletal Radiol. 1993;22:337–357. doi: 10.1007/BF00198395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pennes DR, Braunstein EM, Glazer GM. Computed tomography of cortical desmoid. Skeletal Radiol. 1984;12:40–42. doi: 10.1007/BF00373175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Posch TJ, Puckett ML. Marrow MR signal abnormality associated with bilateral avulsive cortical irregularities in a gymnast. Skeletal Radiol. 1998;27:511–514. doi: 10.1007/s002560050429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Resnick D, Greenway G. Distal femoral cortical defects, irregularities, and excavations. Radiology. 1982;143:345–354. doi: 10.1148/radiology.143.2.7041169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Seeger LL, Yao L, Eckardt JJ. Surface lesions of bone. Radiology. 1998;206:17–33. doi: 10.1148/radiology.206.1.9423647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sklar DH, Phillips JJ, Lachman RS. Case Report 683. Distal metaphyseal femoral defect (cortical desmoid; distal femoral cortical irregularity) Skeletal Radiol. 1991;20:394–396. doi: 10.1007/BF01267672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yamazaki T, Maruoka S, Takahashi S, Saito H, Takase K, Nakamura M, Sakamoto K. MR findings of avulsive cortical irregularity of the distal femur. Skeletal Radiol. 1995;24:43–46. doi: 10.1007/BF02425946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]