Abstract

Background

Current physician practices are not effective in adequately evaluating and treating patients for osteoporosis. While dual-energy xray absorptiometry is the gold standard in evaluating bone mineral density, calcaneal quantitative ultrasound has emerged as a low-risk and low-cost alternative.

Questions/purposes

We estimated the prevalence of abnormal bone mineral density with calcaneal quantitative ultrasound and developed criteria for risk stratification in female and male orthopaedic patients.

Methods

We enrolled 500 patients (331 women, 169 men) with a mean age of 67 years (range, 55–94 years) and screened them for osteoporosis with calcaneal quantitative ultrasound. Multivariate logistic regression was used to identify predictors of low bone mineral density and a risk model was developed.

Results

Quantitative ultrasound identified 154 patients with low bone mineral density at the time of enrollment. The prevalence of abnormal bone mineral density was 31% (women: 38%, men: 17%). Multivariate analysis demonstrated age, female gender, smoking, wrist fracture, and spinal deformities independently predicted low bone mineral density. The probability of low bone mineral density among patients with more than one risk factor was greater than 50% among women and greater than 30% among men.

Conclusions

Low bone mineral density is common among orthopaedic outpatients. Age, female gender, smoking, wrist fractures, and spinal deformities are independent risk factors for osteoporosis. We present a probability model designed to assist orthopaedic surgeons in identifying high-risk patients and initiating adequate preventative measures.

Level of Evidence

Level I, diagnostic study. See Guidelines for Authors for a complete description of levels of evidence.

Introduction

Osteoporotic fractures are a major public health problem, with over 1.5 million injuries occurring each year in the United States [24]. Despite evidence from randomized placebo-controlled trials that bisphosphonates [3, 14, 18], selective estrogen receptor modulators [8], calcitonin [26], and teriparatide [25] decrease fracture risk (above and beyond calcium and vitamin D), several studies document less than 1/3 of patients are effectively evaluated and treated for osteoporosis [15, 27, 30, 32]. A review of a large managed-care database found only 2.8% of women older than 50 years with distal radius fractures subsequently underwent a bone mineral density (BMD) test (dual-energy xray absorptiometry [DXA] scan of the hip and spine) and 22.9% were treated with medication targeting osteoporosis [9]. A decade later, these numbers have not improved: only 21% of distal radius fracture patients evaluated in our medical center were subsequently evaluated for osteoporosis [28]. As such, current physician practices remain ineffective in adequately evaluating and treating patients for osteoporosis, particularly after fragility fractures.

DXA is currently the gold standard for assessing BMD. Its use, however, is often limited by availability, cost, and radiation exposure. Quantitative ultrasound (QUS) has emerged as a new technology that can accurately predict fracture risk; it is portable, inexpensive, and easy to perform in the outpatient setting and is a useful tool in identifying patients for future DXA analysis [2, 11, 12, 16, 20, 33]. In one large study of 6189 postmenopausal women over 65 years of age from 4 centers QUS used alone or sequentially with DXA reportedly accurately identified patients at risk for future fracture who would benefit from further treatment [2]. QUS, however, is not widely known to orthopaedic surgeons.

We therefore (1) determined the prevalence of abnormal BMD among orthopaedic outpatients using QUS; (2) identified predictors of low BMD; and (3) developed a probability model for risk stratification in this patient population.

Patients and Methods

Following approval by our Institutional Review Board, we recruited patients from our outpatient orthopaedic clinic between January and March 2008. Our clinic serves an urban tertiary-care medical center. Represented subspecialties include hand and upper extremity, foot and ankle, sports medicine and arthroscopy, arthroplasty, musculoskeletal oncology, spine, trauma, and rheumatology. During this time period, there was no standardized osteoporosis program for patients in our department. All 2790 patients 55 years or older seen during those three months were eligible for inclusion (there were no additional exclusion criteria). A research assistant (JS) approached 930 of these patients in random fashion to discuss the study protocol and 500 chose to participate, for a response rate of 54%. The 500 patients who agreed to participate form the basis of this report. There were 331 women and 169 men with an average age of 67 years (range, 55–94 years) (Table 1). Power analysis indicated a minimum sample size of 100 patients in each age group would provide 80% power to detect an odds ratio of 2.5 between patients with normal and low BMD based on the presence or absence of suspected risk factors.

Table 1.

Demographics and history of injury in the study population (n = 500)

| Characteristic | Number of patients | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| 55–64 years | 225 | 45 |

| 65–74 years | 163 | 33 |

| 75–94 years | 112 | 22 |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 331 | 66 |

| Male | 169 | 34 |

| Race | ||

| Caucasian or Asian | 384 | 77 |

| African American or Hispanic | 116 | 23 |

| Cigarette smoking | 42 | 8 |

| Immunosuppression | 33 | 7 |

| Thyroid medication/steroids | 84 | 17 |

| Physical activity < 30 minutes/week | 127 | 25 |

| Fracture as a child | 92 | 18 |

| History of fracture | ||

| Wrist fracture | 71 | 14 |

| Hip fracture | 25 | 5 |

| Spine fracture | 38 | 8 |

| Osteoarthritis | ||

| Spine | 134 | 27 |

| Hip | 81 | 16 |

| Knee | 124 | 25 |

| Shoulder | 90 | 18 |

| Hand | 143 | 29 |

| Foot/ankle | 72 | 14 |

| Other orthopaedic conditions | ||

| Spinal deformity | 88 | 18 |

| Current lower extremity fracture | 43 | 9 |

| Current upper extremity fracture | 40 | 8 |

| ACL or meniscal injury | 76 | 15 |

| Patellofemoral disorders | 144 | 29 |

| Rotator cuff tendonitis/tear | 183 | 31 |

| Foot and ankle tendonitis | 30 | 6 |

| Carpal tunnel syndrome | 65 | 13 |

| Trigger finger | 57 | 11 |

| Lateral epicondylitis | 34 | 7 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 26 | 5 |

At the time of enrollment, patients were given a one-page questionnaire to assess risk factors for osteoporosis and define their orthopaedic medical history. Once the questionnaire was completed, a research assistant reviewed answers with each patient to ensure accuracy and minimize ambiguity. The study-specific questionnaire included a risk assessment for osteoporosis based on well-established criteria [24] and a detailed evaluation of patients’ orthopaedic diagnoses. Known risk factors for osteoporosis such as smoking, immunosuppression, steroid and thyroid medication use, history of fracture, and low physical activity were tabulated. Patients were subsequently asked whether they had known diagnoses of osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, upper extremity or lower extremity fractures, spinal deformity (kyphosis and/or scoliosis), ACL or meniscal injury, patellofemoral pain, tendinosis in the foot and ankle, rotator cuff tendinosis or tear, carpal tunnel syndrome, trigger finger, and lateral epicondylitis. These diagnoses were identified by ICD-9 codes as the 15 most common conditions seen in our outpatient practice.

Osteoporosis screening was performed using calcaneal QUS (Achilles Express®; General Electric Corp, Madison, WI) on the day of enrollment. QUS measures two ultrasound variables of the calcaneus (velocity and broadband attenuation) to generate a stiffness index and T-score comparable to that obtained by DXA. Patient preparation and positioning typically takes 3 to 5 minutes and reports are generated within 30 to 60 seconds. Normative data used to generate T-scores was obtained from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey [23] with a precision of ± 2% of BMD for osteoporotic bone and less than 2% for nonosteoporotic bone. Although studies show T-scores obtained by QUS to correlate well with DXA [2, 20], they cannot be subjected to the diagnostic thresholds defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) for osteoporosis and osteopenia. Instead, generated T-scores are valuable to identify patients at risk for osteoporosis who would subsequently benefit from DXA scanning for definitive evaluation. Patients were stratified into two groups: low risk for abnormal BMD (T-score > −1) and high risk for abnormal BMD (T-score ≤ −1). The high risk group was the subject of further statistical analysis to identify other factors associated with abnormal BMD.

QUS measurements were obtained by one research assistant trained in the technique. Measurements were taken according to the guidelines published by the manufacturer [10]. For patients with an injured lower extremity who were unable to weightbear, measurements were taken on the noninjured extremity (n = 10). For all other patients, measurements were taken for both extremities and averaged (n = 490). Although the manufacturer suggests measuring the right foot (if available) when screening patients, we chose to obtain and average measurements from both feet to minimize differences stemming from extremity dominance. Since QUS measurements were obtained in an effort to further define patients at risk for osteoporosis, no therapeutic interventions were performed as a part of this study. Patients were given a copy of their results and told to follow up with their primary care physicians for discussion of further treatment.

Three hundred forty-six of the 500 patients had T-scores greater than −1, 134 patients had T-scores between −1 and −2.5, and 20 patients had T-scores less than −2.5. Patients with T-scores between −1 and −2.5 and those with T-scores less than −2.5 were considered at risk for osteoporosis and were grouped together for further analysis. Using a T-score criterion of −1 or less (n = 154, 31%), univariate analysis was performed to identify demographic variables and patient factors associated with low QUS values as compared to normal (n = 346, 69%). Fisher’s exact test was used to compare proportions between the two groups and the chi square test for assessing the relationship between abnormally low QUS values and age groups. Once significant univariate variables were identified, a multivariate logistic regression modeling was applied to determine independent predictors of low BMD. This model included all variables with p values of less than 0.20 identified by univariate analysis [19]. This allowed us to test 15 variables, which was appropriate given the number of patients with abnormally low QUS values based on our T-score definition [34]. Based on the final multivariate logistic regression model, we derived predicted probabilities of being at risk for osteoporosis according to the final set of five independent risk factors: age group, gender, smoking status, history of wrist fracture, and spinal deformity [13]. Statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS® software package (Version 16.0; SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL). Two-tailed values of p < 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

The prevalence of low QUS values in our patient population was 31%, with 38% of women and 15% of men at risk for osteoporosis. By age group, the risk for low QUS values was 23% (51 of 225) in patients 55 to 64 years old, 31% (50 of 163) for those between 65 and 74 years of age, and 47% (53 of 112) for those older than 75 years.

In the univariate analysis, older age, female gender, smoking, history of wrist or hip fracture, current upper extremity fractures, osteoarthritis of the spine, and spinal deformities were associated with low QUS values. Childhood fractures, low physical activity, steroid use, and immunosuppression were not associated with a decrease in BMD. No other common orthopaedic conditions were associated with low QUS values. Multivariate analysis demonstrated increasing age, female gender, smoking, wrist fractures, and spinal deformities independently predicted low QUS values in our patient population (Tables 2, 3). The odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals are presented as measures of risk and reflect increased risk based on older age, female gender, smoking, history of an adult wrist fracture, and spinal deformity. The likelihood ratio test is the maximum likelihood statistic for assessing significance in the multivariate logistic regression model with 3.84 as the value needed to reach significance for any predictor.

Table 2.

Demographics and injury characteristics for the normal and low BMD groups

| Characteristic | Normal BMD group | Low BMD group | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 346) | (n = 154) | ||

| Age | < 0.001*,† | ||

| 55–64 years | 174 (77) | 51 (23) | |

| 65–74 years | 113 (69) | 50 (31) | |

| 75–94 years | 59 (53) | 53 (47) | |

| Gender | < 0.001*,† | ||

| Female | 206 (62) | 125 (38) | |

| Male | 140 (83) | 29 (17) | |

| Cigarette smoking | < 0.001*,† | ||

| Yes | 19 (45) | 23 (55) | |

| No | 327 (71) | 131 (29) | |

| History of adult wrist fracture | < 0.001*,† | ||

| Yes | 33 (46) | 38 (54) | |

| No | 313 (73) | 116 (27) | |

| Spinal deformity | < 0.01*,† | ||

| Yes | 49 (56) | 39 (44) | |

| No | 297 (72) | 115 (28) | |

| Current upper extremity fracture | 0.01* | ||

| Yes | 20 (50) | 20 (50) | |

| No | 326 (71) | 134 (29) | |

| History of adult hip fracture | < 0.01* | ||

| Yes | 11 (44) | 14 (56) | |

| No | 335 (70) | 140 (30) | |

| Fracture as a child | 0.08 | ||

| Yes | 71 (77) | 21 (23) | |

| No | 275 (67) | 133 (33) | |

| Activity < 30 minutes/week | 0.15 | ||

| Yes | 81 (64) | 46 (36) | |

| No | 265 (71) | 108 (29) | |

| Osteoarthritis to the spine | 0.02* | ||

| Yes | 82 (61) | 52 (39) | |

| No | 264 (72) | 102 (28) | |

Low BMD was defined as a T-score −1 or less; all percentages are calculated horizontally and are shown in parentheses; *significant univariate predictor, Fisher’s exact test or Pearson chi square for age groups; †significant multivariate predictor, logistic regression modeling; BMD = bone mineral density.

Table 3.

Independent multivariate risk factors of being at risk for osteoporosis

| Predictor | Likelihood ratio test | p Value | Odds ratio | 95% confidence interval |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age group* | ||||

| Group 2 vs 1 | 3.9 | 0.04 | 1.6 | 1.2–2.4 |

| Group 3 vs 1 | 24.3 | < 0.001 | 3.7 | 2.2–6.3 |

| Group 3 vs 2 | 11.4 | < 0.001 | 2.5 | 1.5–4.3 |

| Gender, female vs male | 21.2 | < 0.001 | 3.0 | 1.8–4.8 |

| Smoking | 11.8 | < 0.001 | 3.5 | 1.7–7.0 |

| Wrist fracture | 10.8 | < 0.001 | 2.6 | 1.5–4.5 |

| Spinal deformity | 4.5 | 0.03 | 1.7 | 1.1–3.0 |

* Age groups: 1 = 55–64 years, 2 = 65–74 years, 3 = 75–94 years.

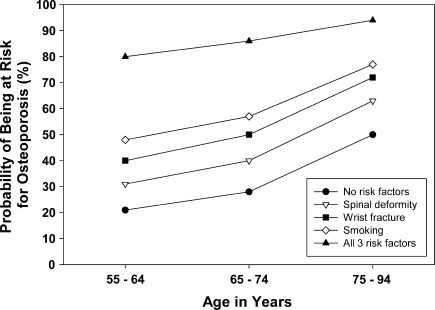

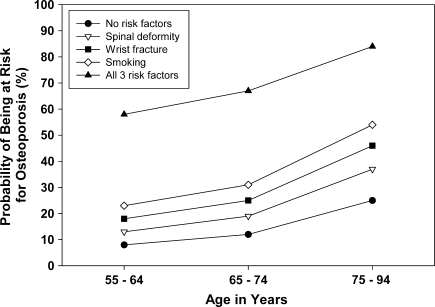

Based on the identified multivariate predictors of low QUS values, probabilities of detecting low values were calculated for both men and women with these characteristics. Women between the ages of 55 and 64 years with no other risk factors had a 21% probability of having low QUS values. In that same age group, one additional risk factor increased the probability to 30% to 48% and two risk factors increased it to 50% to 70%. Those with three risk factors had an 80% probability of having low QUS values. In the 75- to 94-year age group, the probability of low QUS values was 50% for women with no risk factors, 60% to 80% for those with one risk factor, and more than 80% for those with two risk factors (Table 4). Among men between 55 and 64 years of age, the probability of low QUS values was 8% if no other risk factors were present, 13% to 23% with one risk factor, and 28% to 44% with two risk factors, and 58% with three risk factors. In the 75- to 94-year age group, the probability of low QUS values was 25% for men with no risk factors, 37% to 54% for those with one risk factor, and over 60% for those with two risk factors (Table 5). The probabilities of having low QUS values for each individual risk factor and for all risk factors combined are shown for women (Fig. 1) and men (Fig. 2). The probabilities of low QUS values are higher in women than in men for each individual risk factor as well as for all risk factors combined. The probability of low QUS values for women and men over the age of 75 is over 80% once all three risk factors are present.

Table 4.

Probability of being at risk for osteoporosis in women for three age groups based on smoking status, wrist fracture history, and spinal deformity

| Age group (years) | Smoking status | Wrist fracture | Spinal deformity | Probability of low BMD (%) | 95% confidence interval |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 55–64 | − | − | − | 21 | 15–27 |

| 55–64 | − | − | + | 31 | 21–45 |

| 55–64 | − | + | − | 40 | 27–55 |

| 55–64 | + | − | − | 48 | 30–66 |

| 55–64 | − | + | + | 54 | 36–71 |

| 55–64 | + | − | + | 61 | 39–79 |

| 55–64 | + | + | − | 70 | 49–85 |

| 55–64 | + | + | + | 80 | 60–91 |

| 65–74 | − | − | − | 28 | 21–37 |

| 65–74 | − | − | + | 40 | 28–54 |

| 65–74 | − | + | − | 50 | 36–64 |

| 65–74 | + | − | − | 57 | 38–75 |

| 65–74 | − | + | + | 63 | 47–77 |

| 65–74 | + | − | + | 70 | 50–85 |

| 65–74 | + | + | − | 78 | 59–89 |

| 65–74 | + | + | + | 86 | 70–94 |

| 75–94 | − | − | − | 50 | 39–61 |

| 75–94 | − | − | + | 63 | 48–76 |

| 75–94 | − | + | − | 72 | 56–83 |

| 75–94 | + | − | − | 77 | 60–89 |

| 75–94 | − | + | + | 81 | 67–91 |

| 75–94 | + | − | + | 86 | 70–94 |

| 75–94 | + | + | − | 90 | 77–96 |

| 75–94 | + | + | + | 94 | 84–98 |

BMD = bone mineral density.

Table 5.

Probability of being at risk for osteoporosis in men for three age groups based on smoking status, wrist fracture history, and spinal deformity

| Age group (years) | Smoking status | Wrist fracture | Spinal deformity | Probability of low BMD (%) | 95% confidence interval |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 55–64 | − | − | − | 8 | 5–13 |

| 55–64 | − | − | + | 13 | 7–24 |

| 55–64 | − | + | − | 18 | 10–31 |

| 55–64 | + | − | − | 23 | 11–42 |

| 55–64 | − | + | + | 28 | 15–47 |

| 55–64 | + | − | + | 35 | 16–59 |

| 55–64 | + | + | − | 44 | 23–67 |

| 55–64 | + | + | + | 58 | 32–80 |

| 65–74 | − | − | − | 12 | 7–19 |

| 65–74 | − | − | + | 19 | 10–32 |

| 65–74 | − | + | − | 25 | 15–40 |

| 65–74 | + | − | − | 31 | 16–52 |

| 65–74 | − | + | + | 37 | 21–56 |

| 65–74 | + | − | + | 44 | 23–68 |

| 65–74 | + | + | − | 54 | 32–75 |

| 65–74 | + | + | + | 67 | 43–85 |

| 75–94 | − | − | − | 25 | 16–36 |

| 75–94 | − | − | + | 37 | 22–54 |

| 75–94 | − | + | − | 46 | 30–63 |

| 75–94 | + | − | − | 54 | 32–74 |

| 75–94 | − | + | + | 60 | 39–77 |

| 75–94 | + | − | + | 67 | 42–85 |

| 75–94 | + | + | − | 75 | 53–89 |

| 75–94 | + | + | + | 84 | 64–94 |

BMD = bone mineral density.

Fig. 1.

A graph shows the probability of being at risk for osteoporosis for women in three age groups based on having none of the three risk factors identified (wrist fracture, spinal deformity, smoking), each single risk factor alone, and the combination of all three risk factors.

Fig. 2.

A graph shows the probability of being at risk for osteoporosis for men in three age groups based on having none of the three risk factors identified (wrist fracture, spinal deformity, smoking), each single risk factor alone, and the combination of all three risk factors.

Discussion

Current practices do not effectively evaluate and treat patients for osteoporosis. Among orthopaedic patients in particular, one study suggests that patients are not adequately evaluated and treated for underlying abnormalities in bone metabolism [28]. We therefore identified orthopaedic patients at risk for osteoporosis by determining the prevalence of abnormal BMD, recognizing predictors of abnormal BMD and developing a probability model for risk stratification in this patient population.

Our study has several inherent limitations. First, the use of QUS as a screening method for osteoporosis is still controversial. While QUS accurately predicts BMD and fracture risk [2, 11, 12, 16, 20, 33], DXA scan continues to be the gold standard to quantify BMD [2, 16, 20]. We chose to evaluate patients with QUS as this presents a quick, low-cost, and low-risk alternative to DXA scanning: according to Medicare reimbursement rates, the cost of an axial DXA scan (Common Procedural Terminology Code 77080) ranges from $80 to $110 while QUS (Common Procedural Terminology Code 76977) ranges from $30 to $54 [4]. Although we did not confirm our diagnoses using DXA scan, we believe the established correlation between QUS and DXA in detecting low QUS values and fracture risk justifies its use in this study [11, 33]. Second, when using QUS, the WHO definition for osteoporosis cannot be applied. We therefore separated patients into two groups based on their T-scores, using a clinically and statistically suitable cutoff of −1 for osteoporosis risk. Although our high-risk group parallels the WHO definition of osteopenia and osteoporosis, different cutoff points could have been used in delineating our patient groups. It is also important to note the WHO criteria for osteoporosis and osteopenia do not always accurately reflect fracture risk and up to 50% of those who suffer hip and other nonvertebral fractures do not have osteoporosis by BMD testing [29, 31, 35]. In addition, we did not control for body mass index and this may influence the data analysis and relative risk. Finally, one must consider the possibility of selection bias. We attempted to minimize this by recruiting patients in our clinic with no specific exclusion criteria other than age. Furthermore, age and gender distributions were similar in patients who agreed to participate when compared to those who declined. We thus believe our patient sample is representative of our clinic’s overall patient population. Given our patients were drawn from an urban tertiary-care center, however, generalizing our results to other populations should be made with caution.

Our data suggested approximately 1/3 of orthopaedic outpatients had low BMD by QUS. The prevalence of low QUS values in our patient population was 38% (125 of 331) among women and 17% (29 of 169) among men. Among those affected by low QUS values, 81% were women and 19% were men. These numbers likely reflect the ethnic and geographic makeup of our practice (serving a diverse metropolitan area) and parallel national statistics, which estimate 35% to 50% of women and 20% to 35% of men are affected by osteopenia or osteoporosis [24].

Having established the prevalence of abnormal BMD in our patient population, we sought to further identify and define clinical risk factors for low QUS values. Further knowledge and identification of risk factors for osteoporosis among orthopaedic outpatients should aid their treating physicians in adequately targeting those in need of further testing and/or treatment. Previously identified risk factors for low BMD include a history of fragility fracture, family history of osteoporosis, low physical activity, and low body mass index [17]. The Study of Osteoporotic Fractures identified age, weight, muscle strength, and estrogen use as the strongest factors to influence bone mass in elderly women [1]. A number of studies document fractures of the distal radius, proximal humerus, spine, and hip are all associated with an increase in the risk of subsequent fracture [5–7, 21, 22]. Our multivariate regression model analyzing lifestyle factors, as well as medical and orthopaedic histories, identified age, gender, wrist fractures, smoking, and spinal deformities as strong, independent predictors of low QUS values among orthopaedic outpatients. Other factors such as steroid use and low physical activity, however, were not predictive of low QUS values. Among our patient population, a fracture of the distal radius was a strong multivariate predictor of osteoporosis risk. Since wrist fractures occur in a younger age group than hip or vertebral fractures, patients with these injuries offer a unique opportunity to initiate preventative strategies. To date, few patients with distal radius fracture are adequately treated for their underlying bone disease [28]. Orthopaedic surgeons should thus be particularly mindful of this high-risk group.

As a final step, factors identified by multivariate analysis as predictors of low QUS values were used to construct a probability model to determine risk for osteoporosis among orthopaedic patients. While one typically expects elderly patients to have osteopenia or osteoporosis, our analysis revealed a high probability of detecting abnormal BMD by QUS in younger age groups. Among patients 55 to 64 years old with wrist fractures, the probability of abnormal BMD was 40% among women and 18% among men. Adding smoking as a risk factor increased the probability of low QUS values to 70% in women and 44% among men. In patients presenting with spinal deformities, the probability of low QUS values was 30% to 60% in women and 13% to 37% in men depending on the age group. These numbers highlight the essential role orthopaedic surgeons should have in identifying patients at risk and ensuring proper evaluation and treatment for underlying osteoporosis.

Our study revealed low QUS values are common among orthopaedic outpatients. Increasing age, female gender, smoking, wrist fracture, and spinal deformities were identified as independent risk factors for low QUS values and osteoporosis. A case-finding strategy utilizing our clinically based probability assessment may be helpful in identifying patients most at risk for future fractures, and orthopaedic surgeons should aggressively target these high-risk patients for evaluation and management of their metabolic bone disease. Additional research validating the use of this model in a clinical setting would be invaluable, as would studies examining the association between QUS use in an outpatient setting and evaluation and treatment rates for osteoporosis in our patient population.

Footnotes

One or more of the authors (TDR) have received funding from Procter and Gamble, Cincinnati, OH.

Each author certifies that his or her institution approved the human protocol for this investigation, that all investigations were conducted in conformity with ethical principles of research, and that informed consent for participation in the study was obtained.

This work was performed at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center.

References

- 1.Bauer DC, Browner WS, Cauley JA, Orwoll ES, Scott JC, Black DM, Tao JL, Cummings SR. Factors associated with appendicular bone mass in older women The Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group. Ann Intern Med. 1993;118:657–665. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-118-9-199305010-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bauer DC, Gluer CC, Cauley JA, Vogt TM, Ensrud KE, Genant HK, Black DM. Broadband ultrasound attenuation predicts fractures strongly and independently of densitometry in older women: a prospective study Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157:629–634. doi: 10.1001/archinte.157.6.629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Black DM, Delmas PD, Eastell R, Reid IR, Boonen S, Cauley JA, Cosman F, Lakatos P, Leung PC, Man Z, Mautalen C, Mesenbrink P, Hu H, Caminis J, Tong K, Rosario-Jansen T, Krasnow J, Hue TF, Sellmeyer D, Eriksen EF, Cummings SR. Once-yearly zoledronic acid for treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1809–1822. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa067312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Web site. Available at: http://www.cms.hhs.gov/PFSlookup/02_PFSSearch.asp#TopOfPage. Accessed September 8, 2009.

- 5.Clinton J, Franta A, Polissar NL, Neradilek B, Mounce D, Fink HA, Schousboe JT, Matsen FA., III Proximal humerus fracture as a risk factor for subsequent hip fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91:503–511. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.G.01529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cooper C, Melton LJ., III Epidemiology of osteoporosis. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 1992;3:224–229. doi: 10.1016/1043-2760(92)90032-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cuddihy MT, Gabriel SE, Crowson CS, O’Fallon WM, Melton LJ., III Forearm fractures as predictors of subsequent osteoporotic fractures. Osteoporos Int. 1999;9:469–475. doi: 10.1007/s001980050172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ettinger B, Black DM, Mitlak BH, Knickerbocker RK, Nickelsen T, Genant HK, Christiansen C, Delmas PD, Zanchetta JR, Stakkestad J, Gluer CC, Krueger K, Cohen FJ, Eckert S, Ensrud KE, Avioli LV, Lips P, Cummings SR. Reduction of vertebral fracture risk in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis treated with raloxifene: results from a 3-year randomized clinical trial. Multiple Outcomes of Raloxifene Evaluation (MORE) Investigators. JAMA. 1999;282:637–645. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.7.637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Freedman K, Kaplan F, Bilker W, Strom B, Lowe R. Treatment of osteoporosis: are physicians missing an opportunity? J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2000;82:1063–1070. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200008000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.GE Healthcare Web site. Lunar Achilles Express. Available at: https://www2.gehealthcare.com/portal/site/usen/menuitem.e8b305b80b84c1b4d6354a1074c84130/?vgnextoid=433f720dc3240210VgnVCM10000024dd1403RCRD&productid=333f720dc3240210VgnVCM10000024dd1403. Accessed September 8, 2009.

- 11.Grabe DW, Cerulli J, Stroup JS, Kane MP. Comparison of the Achilles Express ultrasonometer with central dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry. Ann Pharmacother. 2006;40:830–836. doi: 10.1345/aph.1G549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hans D, Dargent-Molina P, Schott AM, Sebert JL, Cormier C, Kotzki PO, Delmas PD, Pouilles JM, Breart G, Meunier PJ. Ultrasonographic heel measurements to predict hip fracture in elderly women: the EPIDOS prospective study. Lancet. 1996;348:511–514. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(95)11456-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harrell FE, Lee KL, Mark DB. Multivariate prognostic models: issues in developing models, evaluating assumptions and adequacy, and measuring and reducing errors. Stat Med. 1996;15:361–387. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0258(19960229)15:4<361::AID-SIM168>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harris ST, Watts NB, Genant HK, McKeever CD, Hangartner T, Keller M, Chesnut CH, III, Brown J, Eriksen EF, Hoseyni MS, Axelrod DW, Miller PD. Effects of risedronate treatment on vertebral and nonvertebral fractures in women with postmenopausal osteoporosis: a randomized controlled trial. Vertebral Efficacy with Risedronate Therapy (VERT) Group. JAMA. 1999;282:1344–1352. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.14.1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hosam KK, Hussain MS, Tariq S, Perry HM, III, Morley JE. Failure to diagnose and treat osteoporosis in elderly patients hospitalized with hip fractures. Am J Med. 2000;109:326–328. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9343(00)00457-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huopio J, Kröger H, Honkanen R, Jurvelin J, Saarikoski S, Alhava E. Calcaneal ultrasound predicts early postmenopausal fractures as well as axial BMD: a prospective study of 422 women. Osteoporos Int. 2004;15:190–195. doi: 10.1007/s00198-003-1534-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kanis JA. Risk stratification. In: Cooper C, Gehlbach SH, Lindsay R, eds. Prevention and Treatment of Osteoporosis. London, UK: Informa; 2005:43–56.

- 18.Karpf D, Shapiro D, Seeman E, Ensrud K, Johnston C, Conrad C, Silvano A, Harris S, Santora A, Hirsch L, Oppenheimer L, Thompson D. Prevention of nonvertebral fractures by alendronate: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 1997;277:1159–1164. doi: 10.1001/jama.277.14.1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Katz MH. Multivariable Analysis: A Practical Guide for Clinicians. 2nd ed. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2006:96–116.

- 20.Khaw KT, Reeve J, Luben R, Bingham S, Welch A, Wareham N, Oakes S, Day N. Prediction of total and hip fracture risk in men and women by quantitative ultrasound of the calcaneus: EPIC-Norfolk prospective population study. Lancet. 2004;363:197–202. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)15325-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lauritzen JB, Schwarz P, McNair P, Lund B, Transbol I. Radial and humeral fractures are predictors of subsequent hip, radial or humeral fractures in women, and their seasonal variation. Osteoporos Int. 1993;3:133–137. doi: 10.1007/BF01623274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mallmin H, Ljunghall S, Persson I, Naessen T, Krusemo UB, Bergstrom R. Fracture of the distal forearm as a forecaster of subsequent hip fracture: a population-based cohort study with 24 years of follow-up. Calcif Tissue Int. 1993;52:269–272. doi: 10.1007/BF00296650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes.htm. Accessed September 9, 2009.

- 24.National Osteoporosis Foundation. Available at: http://www.nof.org. Accessed September 9, 2009.

- 25.Neer RM, Arnaud CD, Zanchetta JR, Prince R, Gaich GA, Reginster JY, Hodsman AB, Eriksen EF, Ish-Shalom S, Genant HK, Wang O, Mitlak BH. Effect of parathyroid hormone (1–34) on fractures and bone mineral density in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1434–1441. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200105103441904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reginster J, Deroisy R, Lecart M, Sarlet N, Zegels B, Jupsin I, Longueville M, Franchimont P. A double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-finding trial of intermittent nasal salmon calcitonin for prevention of postmenopausal lumbar spine bone loss. Am J Med. 1995;98:452–458. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9343(99)80344-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Riggs BL, Melton LJ., III The prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. N Engl J Med. 1992;327:620–627. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199208273270908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rozental TD, Makhni EC, Day CS, Bouxsein ML. Improving evaluation and treatment for osteoporosis following distal radial fractures: a prospective randomized intervention. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90:953–961. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.G.01121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schuit SC, Klift M, Weel AE, Laet CE, Burger H, Seeman E, Hofman A, Uitterlinden AG, Leeuwen JP, Pols HA. Fracture incidence and association with bone mineral density in elderly men and women: the Rotterdam Study. Bone. 2004;34:195–202. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smith MD, Ross W, Ahern MJ. Missing a therapeutic window of opportunity: an audit of patients attending a tertiary teaching hospital with potentially osteoporotic hip and wrist fractures. J Rheumatol. 2001;28:2504–2508. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stone KL, Seeley DG, Lui LY, Cauley JA, Ensrud K, Browner WS, Nevitt MC, Cummings SR, Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group BMD at multiple sites and risk of fracture of multiple types: long-term results from the Study of Osteoporotic Fractures. J Bone Miner Res. 2003;18:1947–1954. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2003.18.11.1947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Torgerson DJ, Dolan P. Prescribing by general practitioners after an osteoporotic fracture. Ann Rheum Dis. 1998;57:378–379. doi: 10.1136/ard.57.6.378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Trimpou P, Bosaeus I, Bengtsson BA, Landin-Wilhelmsen K. High correlation between quantitative ultrasound and DXA during 7 years of follow-up. Eur J Radiol. 2009 January 7 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Vittinghoff E, McCulloch CE. Relaxing the rule of ten events per variable in logistic and Cox regression. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;165:710–718. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwk052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wainwright SA, Marshall LM, Ensrud KE, Cauley JA, Black DM, Hillier TA, Hochberg MC, Vogt MT. Orwoll ES; Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group. Hip fracture in women without osteoporosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:2787–2793. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-1568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]