Abstract

Background

Parkinson’s disease is a relatively common problem in geriatric patients with an annual incidence rate of 20.5 per 100,000. These patients are at increased risk for falls and resultant fractures. Several reports suggest total shoulder arthroplasty in patients with fractures has a relatively high rate of complications. Whether hemiarthroplasty reduces the rate of complications or improves pain or function is not known.

Questions/purposes

We therefore determined the ROM, pain, complications, and rate of failure of hemiarthroplasty for management of proximal humerus fractures in patients with Parkinson’s disease.

Patients and Methods

We retrospectively reviewed all eight hemiarthroplasties in patients with Parkinson’s disease for fracture of the proximal humerus between 1978 and 2005. Seven patients (seven shoulders) had a minimum of 2 years followup (mean, 9.9 years; range, 2–16 years).

Results

Postoperatively, the mean active abduction was 97°, mean external rotation was 38°, and internal rotation was a mean of being able to reach the level of the sacrum. The mean postoperative pain score was 2.5 points (on a scale of 1–5). There was a greater tuberosity nonunion in one patient and a superior malunion of the greater tuberosity in three patients. No patient had revision surgery.

Conclusions

The benefit of hemiarthroplasty for proximal humerus fractures in patients with Parkinson’s disease was marginal with three shoulders in seven patients having moderate to severe persistent pain and limited function postoperatively.

Level of Evidence

Level IV, therapeutic study. See Guidelines for Authors for a complete description of levels of evidence.

Introduction

Parkinson’s disease is a relatively common problem in geriatric patients, with an annual incidence of 20.5 per 100,000 [19]. These patients have an increased risk of falls [8, 10, 27, 29, 30]. Numerous authors have noted a difference in bone mineral density in this patient population, contributing to an increased risk for fracture [7, 12, 27, 30].

Two surgical options for treating fractures include total shoulder arthroplasty (TSA) and hemiarthroplasty. The literature contains only two reports regarding shoulder surgery in these patients [13, 14]. In a report of 15 patients with Parkinson’s disease who underwent TSA, Koch et al. [13] reported TSA was successful in this population for relieving pain, but the functional results were poor. Kryzak et al. [14] recently reported the results of 49 TSAs for osteoarthritis in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Most patients had improvement in pain, external rotation, and abduction. However, there was a 19% rate of early postoperative instability with eight of 43 shoulders having revision surgery.

An alternative approach is hemiarthroplasty. However, it is unknown whether hemiarthroplasty relieves pain or improves function or is associated with a lower dislocation rate.

Therefore, we determined the ROM, pain, complications, and rate of failure of hemiarthroplasty for treating proximal humerus fractures in patients with Parkinson’s disease.

Patients and Methods

We reviewed the records of all eight patients with Parkinson’s disease who underwent hemiarthroplasty for treatment of a proximal humerus fracture between 1978 and 2005. Patients were identified with the assistance of a computerized database containing the files of all patients who have had surgery at our institution. Seven patients (seven shoulders) with a minimum 2 years followup (mean, 9.9 years; range, 2–16 years) were included in the study. Two hemiarthroplasties were in women and five were in men. Five hemiarthroplasties were on the left and two were on the right. The mean age of the patients included in the study was 72 years (range, 60–84 years) at the time of surgery. No patients were specifically recalled for this study.

The severity of the patients’ Parkinson’s disease was quantified using the Hoehn and Yahr score [11] as determined from the neurology record. The Hoehn and Yahr system classifies the severity of Parkinson’s disease in five stages: Stage I, unilateral involvement; Stage II, bilateral involvement, without balance impairment; Stage III, balance impaired, mild to moderate functional disability; Stage IV, severely disabled, barely able to stand and walk unaided; and Stage V, confined to wheelchair. Six patients were classified as having Stage III Parkinson’s disease and one was classified as having Stage II disease (Table 1). All patients elected operative treatment after a detailed conversation of the risks, benefits, and alternatives to surgery with the patient and/or their family members.

Table 1.

Patient demographics and Neer result rating

| Patient | Parkinson’s stage | Fracture type | Postoperative pain* | Postoperative abduction (°) | Postoperative external rotation (°) | Postoperative internal rotation | Subluxation | Result rating |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | II | 4 part | 4 | 110 | 30 | Abdomen | Superior moderate | Unsatisfactory |

| 2 | III | Head splitting | 1 | 115 | 20 | L5 | Posterior mild | Satisfactory |

| 3 | III | Head splitting | 4 | 60 | 60 | L5 | Normal | Unsatisfactory |

| 4 | III | 4 part | 2 | 90 | 30 | Abdomen | Normal | Satisfactory |

| 5 | III | 4 part | 5 | 30 | 5 | Lateral ilium | Superior moderate | Unsatisfactory |

| 6 | III | 4 part | 1 | 175 | 60 | T6 | Anterior mild | Excellent |

| 7 | III | 3 part | 2 | 150 | 90 | Lateral ilium | Normal | Excellent |

* Shoulder pain was graded as absent (1 point), slight (2 points), present after unusual activity (3 points), moderate (4 points), or severe (5 points).

A standard deltopectoral approach was used in all patients. Heavy nonabsorbable suture was used for tuberosity fixation in all patients. All shoulders underwent soft tissue balancing using a combination of soft tissue techniques in conjunction with alteration of humeral head size to ensure smooth and stable motion with approximately 50% translation of the humeral head anteriorly and posteriorly with the arm in neutral position, full overhead elevation, and lateral rotation to at least 70° with the arm at 90° abduction. There were six Neer humeral components (Kirschner Medical Corp, Fairlawn, NJ) and one Cofield humeral component (Smith and Nephew, Memphis, TN). One of the humeral components was press fit and six were cemented.

Postoperatively, all patients wore a sling and passive ROM exercises were initiated under the supervision of a physical therapist and continued for 4 to 6 weeks. Subsequently, patients were advanced, again under the supervision of a physical therapist, to active-assisted ROM and gentle stretching by 12 weeks.

Patients typically were seen postoperatively in clinic at 2 weeks, 6 weeks, 3 months, 1 year, 2 years, and 5 years. After 5 years postoperatively, the patients returned every 5 years for repeat examination. We clinically assessed all patients having shoulder surgery using a standard shoulder analysis form [22]. The data were collected and recorded by the attending physician in the clinic at the most recent followup. Shoulder pain was graded as absent (1 point), slight (2 points), present after unusual activity (3 points), moderate (4 points), or severe (5 points). Active abduction and external rotation were recorded in degrees. Internal rotation was graded according to the posterior spinal region the thumb could reach.

The preoperative, initial postoperative, and most recent radiographs were reviewed by the authors (TJK, JWS, RHC) and consensus was obtained. Three shoulder radiographs were taken: a 40° posterior oblique radiograph with external rotation of the humerus, a 40° posterior oblique radiograph with internal rotation of the humerus, and an axillary radiograph. Preoperative radiographs, initial postoperative radiographs, and the most recent radiographs were available for all seven shoulders. The preoperative radiographs showed four shoulders with four-part fractures, two shoulders with head-splitting fractures, and one shoulder with a three-part fracture. The postoperative radiographs were reviewed to determine the presence of glenohumeral subluxation, humeral periprosthetic radiolucency, glenoid erosion, and healing of the tuberosities. Humeral periprosthetic radiolucency was defined as Grade 0 if there was no radiolucent line, Grade 1 if the line was 1 mm wide or less and incomplete, Grade 2 if the line was 1 mm wide and complete, Grade 3 if the line was 1.5 mm wide and incomplete, Grade 4 if the line was 1.5 mm wide and complete, Grade 5 if the line was 2 mm wide and incomplete, and Grade 6 if the line was 2 mm wide and complete [1, 15, 16, 20, 21, 23–26]. Glenohumeral subluxation was evaluated for the direction and amount of translation of the center of the prosthetic head relative to the center of the glenoid and was recorded as none, mild (< 25% translation), moderate (25% to 50% translation), or severe (> 50% translation).

Results

At the most recent followup, active abduction was a mean of 97°, external rotation was a mean of 38°, and internal rotation was a mean of being able to reach the level of the sacrum (Table 1). The mean postoperative pain score was 2.5 (on a scale of 1–5). None of the shoulders underwent revision arthroplasty.

Of the seven shoulders, four had glenohumeral subluxation observed on the most recent radiographs. Two had moderate superior subluxation, one had mild posterior subluxation, and one had mild anterior subluxation. Grade 1 humeral periprosthetic radiolucency was present in one shoulder and one had anterior glenoid erosion.

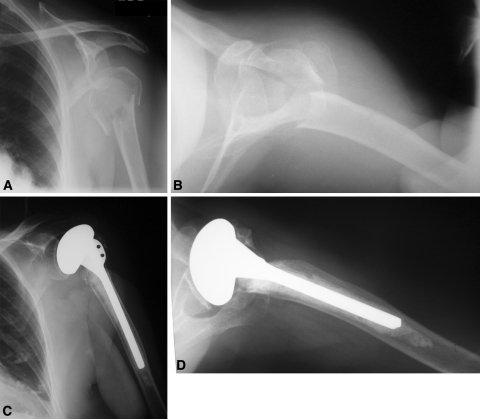

There was a greater tuberosity nonunion in one patient and a superior malunion of the greater tuberosity in three patients (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1A–D.

(A) AP and (B) lateral radiographs of a 74-year-old woman with Parkinson’s disease show a proximal humerus fracture sustained during a fall. She underwent a cemented hemiarthroplasty of the shoulder. (C) AP and (D) lateral radiographs taken 11 years after surgery show a nonunion of the greater tuberosity.

Discussion

Although Parkinson’s disease is a relatively common problem in geriatric patients with an annual incidence of 20.5 per 100,000 [19], the literature contains only a couple reports regarding shoulder surgery in these patients. We determined the ROM, pain, complications, and rates of failure of hemiarthroplasty for management of proximal humerus fractures in patients with Parkinson’s disease.

Our study however, does have some limitations. This is a retrospective review of seven patients with Parkinson’s disease who were treated with shoulder hemiarthroplasty for proximal humerus fractures. Owing to the small subset of patients and the retrospective nature of this study, there is not sufficient power to draw any conclusions regarding hemiarthroplasty for proximal humerus fractures in patients with Parkinson’s disease compared with those without fractures. Another limitation of this report is the lack of comparison of alternative methods of treatment for these patients.

Despite these limitations, our data suggest that some patients with Parkinson’s disease undergoing humeral head replacement for treatment of a proximal humerus fracture may have an improvement in pain and motion. Four of the seven shoulders however, showed evidence of subluxation on the most recent radiographs. Additionally, there was a greater tuberosity malunion in three patients and a nonunion in one.

The majority of the literature regarding arthroplasty for patients with Parkinson’s disease relates to the lower extremity where other authors also have noted substantial pain relief but poor functional results [5, 28]. In a review of 16 TSAs in 15 patients, Koch et al. [13] noted an overall improvement in pain, but functional results were poor. Kryzak et al. [14] recently reported results of TSA for osteoarthritis in 36 patients (49 shoulders) with Parkinson’s disease. In that study, patients experienced improvement in pain, external rotation, and abduction [14]. However, there was an increased rate of early postoperative instability with eight of 43 shoulders (19%) having revision surgery.

Poor functional results have been attributed to multiple reasons including increased muscle tone, severity of tremor, and an increased mortality rate of 1.6 to 3 times that of the general population [13]. Some authors also have noted a difference in bone mineral density in this patient population contributing to an increased risk of fracture [7, 12, 27, 30]. This decreased bone mineral density also can adversely impact bone healing in patients with Parkinson’s, further contributing to poor functional results, as it has been well established that anatomic bony union of the greater and lesser tuberosities to the shaft is essential for satisfactory shoulder function [2, 3, 9].

There are a few reports regarding elective joint arthroplasty of the lower extremity in patients with Parkinson’s disease showing substantial complication rates ranging from 26% to 100% [5, 18, 28]. In our seven patients with a mean followup of 9.9 years, no patient had revision surgery; however, four patients did have glenohumeral subluxation, the clinical importance of which is unclear. However, the ROM, pain, complications, and rate of failure of TSA for treatment of proximal humerus fractures are inferior when compared with TSA for treatment of osteoarthritis [1, 4, 6, 17].

Overall, we judged the results marginal with three of the seven patients having moderate to severe persistent pain and limited function postoperatively. Management of the patient with Parkinson’s disease requires a coordinated effort with the patient’s neurologist to maximize medical management of the disease. Additionally, these patients require adequate social support to try to ensure proper compliance with postoperative rehabilitation and restrictions, and institution of measures to help prevent additional falls.

Footnotes

Each author certifies that he or she has no commercial associations (eg, consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangements, etc) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article. J.W. Sperling is a consultant for Biomet. R.H. Cofield is a consultant for Smith & Nephew.

Each author certifies that his or her institution approved the human protocol for this investigation, and that all investigations were conducted in conformity with ethical principles of research.

References

- 1.Antuna SA, Sperling JW, Cofield RH. Shoulder hemiarthroplasty for acute fractures of the proximal humerus: a minimum five-year follow-up. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2008;17:202–209. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2007.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Antuna SA, Sperling JW, Sanchez-Sotelo J, Cofield RH. Shoulder arthroplasty for proximal humeral malunions: long-term results. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2002;11:122–129. doi: 10.1067/mse.2002.120913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boileau P, Krishnan SG, Tinsi L, Walch G, Coste JS, Mole D. Tuberosity malposition and migration: reasons for poor outcomes after hemiarthroplasty for displaced fractures of the proximal humerus. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2002;11:401–412. doi: 10.1067/mse.2002.124527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cofield RH. Total shoulder arthroplasty with the Neer prosthesis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1984;66:899–906. doi: 10.2106/00004623-198466060-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Duffy GP, Trousdale RT. Total knee arthroplasty in patients with parkinson’s disease. J Arthroplasty. 1996;11:899–904. doi: 10.1016/S0883-5403(96)80130-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Edwards TB, Kadakia NR, Boulahia A, Kempf JF, Boileau P, Nemoz C, Walch G. A comparison of hemiarthroplasty and total shoulder arthroplasty in the treatment of primary glenohumeral osteoarthritis: results of a multicenter study. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2003;12:207–213. doi: 10.1016/S1058-2746(02)86804-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fink HA, Kuskowski MA, Orwoll ES, Cauley JA, Ensrud KE. Association between Parkinson’s disease and low bone density and falls in older men: the osteoporotic fractures in men study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:1559–1664. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53464.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Genever RW, Downes TW, Medcalf P. Fracture rates in Parkinson’s disease compared with age- and gender-matched controls: a retrospective cohort study. Age Ageing. 2005;34:21–24. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afh203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gerber C, Yian EH, Pfirrmann CAW, Zumstein MA, Werner CML. Subscapularis muscle function and structure after total shoulder replacement with lesser tuberosity osteotomy and repair. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87:1739–1745. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.D.02788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grimbergen YA, Munneke M, Bloem BR. Falls in Parkinson’s disease. Curr Opin Neurol. 2004;17:405–415. doi: 10.1097/01.wco.0000137530.68867.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoehn MM, Yahr MD. Parkinsonism: onset, progression and mortality. Neurology. 1967;17:427–442. doi: 10.1212/wnl.17.5.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kamide N, Fukuda M, Miura H. The relationship between bone density and the physical performance of ambulatory patients with Parkinson’s disease. J Physiol Anthropol. 2008;27:7–10. doi: 10.2114/jpa2.27.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koch LD, Cofield RH, Ahlskog JE. Total shoulder arthroplasty in patients with Parkinson’s disease. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1997;6:24–28. doi: 10.1016/S1058-2746(97)90067-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kryzak TJ, Sperling JW, Schleck CD, Cofield RH. Total shoulder arthroplasty in patients with Parkinson’s disease. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2009;18:96–99. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2008.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kumar S, Sperling JW, Haidukewych GH, Cofield RH. Periprosthetic humeral fractures after shoulder arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86:680–689. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200404000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mileti J, Sperling JW, Cofield RH. Shoulder arthroplasty for the treatment of postinfectious glenohumeral arthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85:609–614. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200304000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Neer CS, 2nd, Watson KC, Stanton FJ. Recent experience in total shoulder replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1982;64:319–337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oni OO, Mackenney RP. Total knee replacement in patients with Parkinson’s disease. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1985;67:424–425. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.67B3.3997953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rajput AH. Epidemiology of Parkinson’s disease. Can J Neurol Sci. 1984;11(1 suppl):156–159. doi: 10.1017/s0317167100046321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rice RS, Sperling JW, Miletti J, Schleck C, Cofield RH. Augmented glenoid component for bone deficiency in shoulder arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466:579–583. doi: 10.1007/s11999-007-0104-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sanchez-Sotelo J, O’Driscoll S, Morrey BF. Periprosthetic humeral fractures after total elbow arthroplasty: treatment with implant revision and strut allograft augmentation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84:1642–1650. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.84B8.12902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith AM, Barnes SA, Sperling JW, Farrell CM, Cummings JD, Cofield RH. Patient and physician-assessed shoulder function after arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88:508–513. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.00132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sperling JW, Antuna SA, Sanchez-Sotels J, Schleck C, Cofield RH. Shoulder arthroplasty for arthritis after instability surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84:1775–1781. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200210000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sperling JW, Cofield RH, O’Driscoll SW, Torchia ME, Rowland CM. Radiographic assessment of ingrowth total shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2000;9:507–513. doi: 10.1067/mse.2000.109384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sperling JW, Cofield RH, Rowland CM. Neer hemiarthroplasty and Neer total shoulder arthroplasty in patients fifty years old or less: long-term results. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1998;80:464–473. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199804000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Strickland JP, Sperling JW, Cofield RH. The results of two-stage re-implantation for infected shoulder replacement. J Bone Joint Surg. Br. 2008;90:460–465. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.90B4.20002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vaserman N. Parkinson’s disease and osteoporosis. Joint Bone Spine. 2005;72:484–488. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2004.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weber M, Cabanela ME, Sim FH, Frassica FJ, Harmsen WS. Total hip replacement in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Int Orthop. 2002;26:66–68. doi: 10.1007/s00264-001-0308-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wielinski CL, Erickson-Davis C, Wichmann R, Walde-Douglas M, Parashos SA. Falls and injuries resulting from falls among patients with Parkinson’s disease and other parkinsonian syndromes. Mov Disord. 2005;20:410–415. doi: 10.1002/mds.20347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zuckerman LM. Parkinson’s disease and the orthopaedic patient. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2009;17:48–55. doi: 10.5435/00124635-200901000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]