Abstract

This Classic article is a reprint of the original work by Ruth Jackson, MD, FACS, The Cervical Syndrome. An accompanying biographical sketch on Ruth Jackson, MD, FACS, is available at DOI 10.1007/s11999-010-1277-9. The Classic Article is ©1949 by The Dallas County Medical Society and is reprinted with permission from Jackson R. The cervical syndrome. Dallas Med J. 1949;35:139–146.

A second Classic Article, The Cervical Syndrome, is attached to this article as Electronic Supplementary Material (supplemental materials are available with the online version of CORR). This article is ©1955 by Lippincott Williams and Wilkins and is reprinted with permission from Jackson R. The cervical syndrome. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1955;5:138–148.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s11999-010-1278-8) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Richard A. Brand MD (✉) Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research, 1600 Spruce Street, Philadelphia, PA 19103, USA e-mail: dick.brand@clinorthop.org

The term Cervical Syndrome is used to classify a group of cases which presents definitely similar symptoms and clinical findings, the causative factor of which is irritation of the cervical nerve roots. To interpret adequately this syndrome one must have a knowledge of the anatomy and mechanics of the cervical spine, the segmental character of the cervical nerves, and the relationship between the cervical nerves and the sympathetic nervous system.

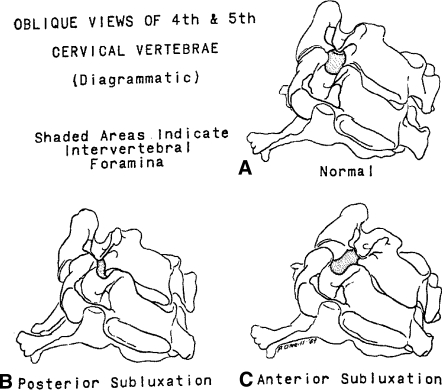

The facets of the cervical vertebrae are designed so that a great range of motion is possible in all directions. The foramina through which the nerve roots pass are bony canals whose vertical diameters are greater than the antero-posterior diameters. The position of the cervical facets prevents more than a minimum alteration of the vertical diameter, but allows changes in the anteroposterior diameter in mechanical derangements of the cervical spine. The posterior walls of the foramina are formed by the articular processes of the adjacent vertebrae, and the anterior walls and floors are formed by the grooves in the roots of the vertebral arches (Fig. 1A). The nerve roots leave the spinal cord at an angle which approximates a right angle, and they fill fairly snugly the foramina through which they pass. This makes them very vulnerable to irritation from any mechanical derangement of the cervical spine. Irritation of these nerves occurs before they divide into anterior and posterior primary rami.

Fig. 1.

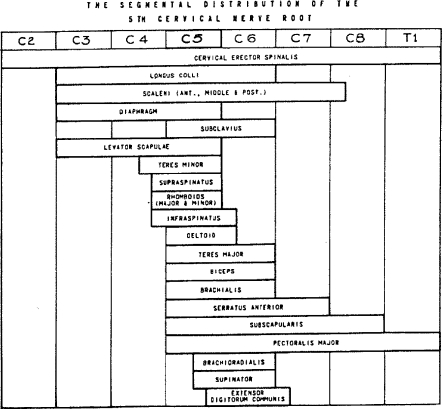

The distribution of the cervical nerves is segmental in character (Fig. 2) and there is a definite overlap of the nerve supply to adjacent segments in any given skin area. Irritation of a nerve root may cause pain and Paraesthesia anywhere along the segmental distribution of the nerve. Because of the reflex phenomenon of pain, painful irritation of a muscle may cause reflex pain anywhere along the segmental distribution of the nerve or nerves which supply that muscle. The segmental distribution of the cervical nerve roots, their sensory overlap, and the reflex phenomenon of pain make the exact localization of nerve root irritation somewhat difficult.

Fig. 2.

The cervical nerve roots are composed of motor and sensory fibers only, as compared with the thoracic and upper two lumbar nerve roots which contain white rami communicantes of the sympathetic nervous system as well. The sympathetic nervous system has its connection with the cervical nerve roots through the upper two thoracic nerves which join the cervical part of the sympathetic trunk via their anterior primary rami, and Proceed upwards to the cervical ganglia. Gray rami communicantes pass from the superior cervical sympathetic ganglia to the anterior rami of the upper four cervical nerves. Two gray rami communicantes from the middle cervical ganglia and two from the inferior cervical ganglia pass to the anterior rami of the lower four cervical nerves. All are distributed with the divisions of the cervical nerves. Other gray rami communi-cans either pass directly or indirectly to most of the cranial nerves, and peripheral branches pass to the pharynx, the heart, and the arteries of the head, neck, and arms. The post ganglionic fibers which invest the internal carotid artery give branches to the third, fourth, and fifth cranial nerves and supply the back of the orbit, the dilator muscle of the pupil, and the smooth muscle of the upper eyelid. Other post ganglionic fibers reach the vestibular portion of the ear by way of the plexus which surrounds the vertebral artery and the fibers which extend to the basilar artery and its internal auditory branch. Stimulation of the post ganglionic fibers may give rise to symptoms and clinical findings such as: swelling and stiffness of the fingers, blurring of vision, ptosis of the eyelid, dilatation of the pupil, and vertigo. These may appear, to the casual observer, to have no relationship to the other symptoms and clinical findings associated with irritation of the cervical nerve roots.

Irritation of the cervical nerve roots occurs as a result of some mechanical derangement in or about the intervertebral foramina. The most common cause of irritation is abnormal motion or subluxation of the joints of the cervical spine (Fig. 1B–C) which occurs as a result of sprain, stretching, or relaxation of the ligamentous and capsular structures. Other causes are: ruptured or protruding intervertebral discs, hypertrophic changes and osteophyte formation in or about the intervertebral foramina, swelling of capsular structures from inflammatory and allergic reactions or from hemorrhage. Any sudden unguarded motion of the neck, or any prolonged relaxation of the neck in an abnormal position may cause a subluxation with actual locking of the facets on one side. Other causative factors may be relaxation of the supporting structures of the cervical spine which may be part of a general process due to illness or increasing age. Poor posture with markedly rounded shoulders causes an increase in hyperextension of the neck and the development of posterior subluxations of the cervical spine. The “loose-jointed” type of posture predisposes to nerve root irritation. The thoughtless roughness in the handling of patients when under a general anesthetic has been responsible for cervical nerve root irritation in many instances.

Cervical nerve root irritation may occur at any age, but the greatest number of patients who seek relief from their symptoms are in the third and fourth decades of life.

The whip-lash type of injury, as described by Davis, is responsible for the greatest percentage of cervical nerve root irritations. This type of injury is caused by a sudden forceful movement of the neck in any direction with a sudden recoil in the opposite direction. Such injuries cause typical sprains of varying degrees with subluxation of the articular processes and stretching, tearing, or avulsion of, and varying amounts of hemorrhage into, the ligamentous and capsular structures. Automobile accidents are responsible for the greatest number of such injuries. However, falls, blows on the head or chin, a sudden forceful pull on the arms, and many other apparently trivial injuries may cause a whip-lash, or a sudden “popping” of the neck. Symptoms may occur immediately or may be delayed weeks, months, or years. The injury is considered insignificant usually, but as time passes there occurs further stretching of the ligamentous and capsular structures which permits more abnormal motion or subluxation of the joints with resulting nerve root irritations.

Rupture or protrusion of one or more intervertebral discs may occur at the time of the injury, or much later as a result of some very trivial injury inasmuch as the relaxation of the ligamentous and capsular support makes the discs more vulnerable to rupture. Ruptured discs may or may not cause immediate nerve root irritation, depending upon the location of the protrusion or herniation.

The amount of irritation, and hence the symptoms and clinical findings, are not dependent upon the extent of the derangement inasmuch as minimal derangements may cause minimal symptoms. Individual variations in the mechanics involved and of pain tolerance may account for this.

The diagnosis of cervical nerve root irritation is based on the history, symptoms, clinical and X-ray findings.

A careful history will reveal an injury to the neck which may have occurred immediately preceeding the onset of the symptoms or weeks, months, or years before. Usually the injury itself is of little significance to the patient.

An analysis of the histories on four hundred (400) cases with cervical nerve root irritation has revealed that all cases can be grouped according to their symptoms. Each case will fall into one of the following classifications:

Patients with acute symptoms following a recent injury.

Patients with chronic symptoms of long duration.

Patients with severely acute well localized pain who have had previous chronic symptoms. In this group of cases the acute symptoms are caused by: sudden hyperextension of the neck as in stooping over to brush the teeth, wash the face or pick up something; sudden turning of the head as in throwing a ball or any other object; and many other apparently simple activities such as reaching backwards, catching one’s self with the hand to prevent a fall or even turning over in bed. These patients usually get sudden severe pain at the tip of the shoulder, which makes them think that the shoulder has been injured, or they get severe pain in the chest or in the muscles of the posterior part of the shoulder girdle which resembles pleurisy. Many of them have a sensation of “blacking out.”

Regardless of the nerve root or roots which may be irritated all patients complain of a certain amount of stiffness and pain in the neck. Many of them complain of a burning sensation at the base of the neck or between the shoulders and of a popping sensation when the head is turned in a certain way.

If the upper roots, C2, C3 and C4, are irritated they may complain of occipital headaches, often typical of migraine, with pain radiating to the eyes and behind the ears, blurring of vision, dizziness and nausea especially when attempting to lie down, numbness of the side of the neck, tension and “knots” in the neck and shoulder muscles, and swelling and stiffness of the fingers. If the fourth and perhaps the fifth nerve roots are irritated they may complain of shortness of breath, palpitation of the heart, pain in the chest, and localized pain in the muscles between the neck and shoulder joint, or between or about the shoulder blades. Irritation of the fifth nerve root is most common and other symptoms are: pain at the tip of the shoulder, in the middle of the arm, sometimes near the elbow in the extensor muscles of the forearm, and numbness and tingling of the thumb and/or index finger. Stiffness of the shoulder and/or weakness of the arm with inability to comb the hair, fasten a brassiere, or to reach the hip pocket are frequent complaints. Irritation of the sixth and seventh nerve roots may cause pain in the shoulder, arm, forearm, wrist, chest and numbness and tingling of the index, middle and perhaps the ring fingers.

All or any of the symptoms may be acute or chronic or intermittent. Usually the symptoms are multiple and the patients have been treated for neuritis, migraine, arthritis, bursitis, and fibrositis. Many of these patients have been treated for heart disease, i.e.; “pseudo-angina pectoris.”

In all instances the symptoms are aggravated by certain motions and positions of the neck. Sewing, reading, driving a car, or any occupation or pleasure which necessitates holding the neck in flexion, hyperextension, rotation or lateral bending for any length of time increases the symptoms. Aggravation of symptoms are found in women just prior to or during menstruation and in both sexes during upper respiratory infections and during emotional strain and fatigue. In most instances the symptoms are worse at night and the patients have difficulty sleeping. Many patients sleep on more than one pillow, which causes flexion of the neck. Some sleep without any pillow which leaves no support beneath the neck, and some sleep in the prone position which necessitates marked rotation of the neck. All these positions, as well as the relaxation of the supporting structures of the neck during sleep, tend to aggravate the symptoms.

The clinical findings vary somewhat with the nerve roots involved, but all have certain findings in common. Localized tender areas are found anywhere along the segmental distribution of the nerve roots which are irritated. All patients have variable amounts of limitation of motion of the neck in lateral bending, rotation, flexion and extension, and all have tenderness just lateral to the spinous processes of the neck on one or both sides. Tender areas over the occiput and behind the ears are found when the second, third, and fourth roots are irritated. Dilatation of the pupil and slight drooping of the eyelid on the side of the irritation are present in about five percent of these cases. Localized myalgic areas and muscle spasm in the ridge and lower portion of the trapezius and in the supraspinatus muscle or tendon are fairly constant findings in fourth nerve root irritation. In fifth nerve root irritation such areas are found in the rhomboid muscles, at the tip of the shoulder, at the insertion of the deltoid, and not infrequently in the extensor muscles of the forearm. Tenderness in the anterior and lateral chest wall and over the sternum is often found. Varying degrees of limitation of glenohumeral motion in abduction, internal and external rotation occur in about twenty percent of these cases. This is due to pain and to an adhesive capsulitis, which results from the prolonged protective reaction of voluntary immobilization. Many of these patients develop calcareous deposits in the tendons (usually the supraspinatus) of the musculo-tendinous cuff. The deposition of calcium in this region is doubtless due to the circulatory changes which occur as a result of muscle spasm and limitation of motion. Paraesthesias over the distribution of the cutaneous branch of the axillary nerve occur almost constantly. The biceps and triceps reflexes may be altered or absent in fifth, sixth, and seventh nerve root irritation, and there may be, in a small percentage of cases, irregular paraesthesias of the arm, forearm, thumb and fingers.

Pressure over the involved nerve root or roots and the compression test may reproduce the radicular pain, but do not give much added information as far as diagnosis is concerned.

Whatever is the causative mechanism of nerve root irritation the clinical findings are the same. Perhaps electromyography may be of some value in localization and differentiation of the irritative factors, but the segmental character of the cervical nerves, the sensory over-lap, and the reflex phenomenon make exact localization of the nerve root or roots involved difficult. The author believes that irritation of a single nerve root occurs in only a small percentage of cases, and that this accounts for the multiplicity of symptoms and clinical findings. However, many of the findings are difficult to understand on the basis of an exact anatomical explanation, for example: why should irritation from an injection of novocaine about the fourth nerve root cause momentary pain or tingling of the little and ring fingers?

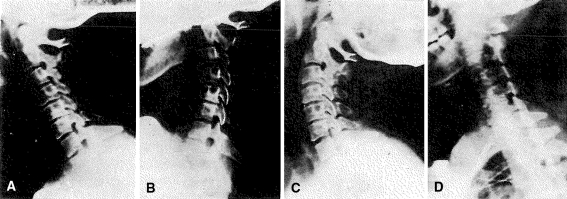

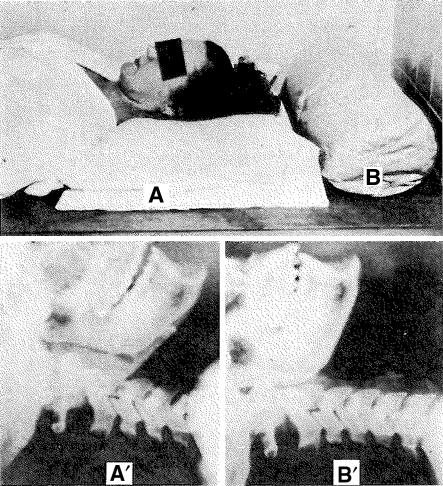

X-ray films of the cervical spine should be made in all cases. The author uses the technique described by Davis. Three lateral views are made with the patient in the upright position and with the X-ray tube at seventy-two inches from the casette. The films are made with the patient looking straight ahead, with the chin on the chest, and with the neck in hyperextension (Fig. 3). The straight lateral view reveals the presence of muscle spasm of the neck muscles as evidenced by the obliteration of the normal forward curve of the cervical spine (Fig. 3A) and in some cases a segmental reversal of the curve. The chin on the chest view reveals forward subluxations, and the hyperextension view reveals posterior subluxations of the bodies of the vertebrae (Fig. 3B–C). It must be remembered, however, that the amount or extent of the subluxations is not indicative of the amount or extent of the nerve root irritation. It is the author’s opinion that subluxations in the cervical spine are abnormal and occur because of stretching, tearing or undue relaxation of the ligamentous and capsular structures.

Fig. 3A–D.

(A) Straight lateral film shows loss of normal forward curve, narrowing of intervertebral spaces between C4 and C5 and C5 and C6, and lipping posteriorly of C5 and C6. (B) Forward flexion view shows forward subluxation of C2 on C3 and C3 on C4. (C) Hyperextension view shows posterior subluxation of C2 on C3 and C3 on C4. Note fixation of C4, C5 and C6 in all positions. Motion occurs above and below these vertebrae. (D) Oblique view shows antero-posterior narrowing of intervertebral foramina between C4 and C5, and C5 and C6.

Single subluxations occur in about fifteen percent of the cases and about one-half of these occur between C4 and C5. About eighty-five percent of the cases show more than one subluxation and some of these show as many as four subluxations.

Approximately forty percent of the cases show definite narrowing of one or more intervertebral spaces (Fig. 3). This is indicative of ruptured discs, but there is no way of ascertaining from the X-ray films just when the ruptures occurred. Hypertrophic changes, marginal lipping or osteophyte formation do not indicate how long a ruptured disc has been present, nor do they indicate the age of the patient. These changes are initiated by the mechanical derangement and for psychological reasons they should not be designated as arthritis. Nature is only making an effort to overcome the mechanical stress and strain by attempting to immobilize the adjacent vertebrae. The author has noted that fixation of the vertebrae adjacent to narrowed discs is a constant finding and that motion and subluxations occur above or below these vertebrae (Fig. 3). The onset of acute episodes in most of these cases is due to a recent injury or sprain with nerve root irritation above or below the level of the fixed vertebrae.

X-ray films made in the oblique position give additional information concerning the foramina (Fig. 3D). Hypertrophic changes or spur formation projecting into the intervertebral foramina, and antero-posterior narrowing of the foramina can be demonstrated. Oblique views made in flexion and in hyperextension reveal which position causes the greatest antero-posterior alteration or narrowing of the foramina.

Antero-posterior views of the cervical spine give little added information, and should be made at the discretion of the examining doctor.

In ninety percent of the patients who have given occipital headaches or migraine as a symptom, the author has found subluxations of C2 on C3, and of C3 on C4 in the other ten percent. This probably indicates that irritation of the third nerve root is responsible for most of the headaches. However, there may be a sympathetic factor responsible for these headaches due to irritation of the nerve roots and reflex stimulation of the post ganglionic fibers from the superior cervical ganglion.

The severity and duration of the symptoms and the clinical and X-ray findings govern the treatment of these cases. In any event the treatment must be individualized. Conservative or nonsurgical treatment will give the best results. From the beginning, the patient should be taught that the symptoms can be relieved by fairly simple measures, but that there must be an adjustment of every-day activities to the mechanical derangement of his neck.

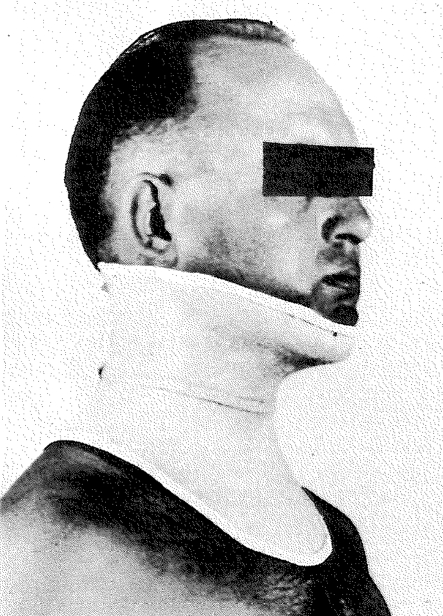

Patients who are seen immediately following an injury to the neck should have the benefit of some type of collar immobilization for about three weeks. Figure 4 shows the collar recently perfectly by the author and Mr. Cecil Wren, brace-maker. If there is actual locking of the facets one-half percent novocaine should be injected about the involved facets. It may be necessary to apply halter traction for two to four days before the collar is applied. The correct application of the traction is extremely important. The knees should be flexed and the upper portion of the body elevated to prevent an uncomfortable pull on the abdominal muscles. The line of traction should be straight and either flexion or hyperextension should be avoided.

Fig. 4.

Cervical support made of Celastic.

The patients with subacute and chronic symptoms may require the injection of novocaine into the myalgic areas for relief of pain. The injection may be made in the neck muscles and about the involved nerve root or roots. Occipital headaches can be relieved by injecting about the occipital nerves. Breaking of the pain reflex with a local anesthetic, if done correctly, gives immediate relief of pain which lasts for days, weeks, or months. There may be some residual soreness from the injection for 24 to 36 hours, but the acute symptoms will subside at once. Diathermy treatments daily or three times each week help to relieve pain and muscle spasm.

If the general posture is poor, shoulder straps are often of great value in the relief of pain and discomfort. Correct postural habits must be taught and the patients should learn the mechanics involved for the relief of symptoms and the prevention of future attacks. They should avoid holding the neck in flexion or hyperextension for any length of time. Reading in bed should be avoided. Reading stands to hold the reading material at eye level, lowering desk chairs or raising desks, raising or lowering the automobile seat, and many other simple adjustments are of great benefit.

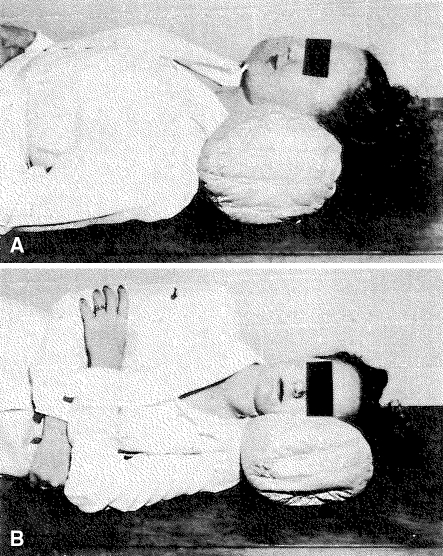

Because many patients complained of aggravation of symptoms while in bed, and because correct sleeping posture is important in the treatment of these patients, the author designed a special pillow which has been the greatest adjunct in treatment. The pillow fits the normal contour of the neck and keeps the neck straight while the patient is sleeping (Figs. 5A–B, 6B′). The conventional pillow causes flexion of the neck (Fig. 6A–A′) and aggravates the symptoms. In some instances this “cervical contour pillow” gives relief of symptoms without other treatment.

Fig. 5A–B.

Note complete relaxation and straight position of the neck in positions (A) and (B).

Fig. 6A–B.

(A) Conventional pillow. Note deep crease between chin and neck. (B) Contour pillow. (A′) Lateral X-ray made with patient’s head on a conventional pillow. (B′) Film made with patient’s neck on contour pillow.

The stiff shoulders should be treated by novocaine injections, diathermy, and intensive physical therapy. Only occasionally is it necessary to manipulate such shoulders under a general anesthetic. Vitamin E given intramuscularly and Tolserol by mouth in the subacute and chronic cases give relief of muscle spasm or tension in many instances.

Emotional stress and strain should be eliminated in all cases, if possible.

The importance of cervical investigation in any patient with head, neck, chest, shoulder and arm pain cannot be over-stressed. The usual diagnosis of neuritis, bursitis, periarthritis, myositis, fibrositis, myofascitis, pseudo-angina pectoris and migraine should not be made until cervical nerve root irritation has been ruled out entirely. Usually these conditions are only manifestations of cervical nerve root irritation.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

References

- Hanflig SS. Pain in Shoulder-girdle, Arm, and Precordium Due to Foramina! Compression of Nerve Roots. Arch, Surg. 1943;46:652–663. [Google Scholar]

- Michelson, J. J., Mixter, W. J.: Pain and Disability of Shoulder and Arm Due to Herniation of Nucleus Pulposes of Cervical Disc: New England Med. Jr. 231–279–287, Aug. 24, ’44 and 231–490 Oct. 5, ’44.

- Bisgard JD. Arthritis of the Cervical Spine, Some Neurological Manifestations. J. A. M. A. 1932;98:1961–1965. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, E. L. & Oppenheimer, A.: A Common Lesion of the Cervical Spine Responsible for Segmental Neuritis: Own. Ind. Med. W; 427–440, 1936.

- Spurling, R. G. & Scoville, W. B.: Lateral Rupture of Cervical Intervertebral Disc—Common Cause of Shoulder and Arm Pain, S. G. & O. 78: 350–358, April, ’44.

- Davis, Arthur G.: Injuries of the Cervical Spine, J. A. M. A. 127: 149–156.

- Brazier, Watkins, Michelsen: Electromyography in Differential Diagnosis of Ruptured Cervical Disc. Archives of Neurology and Psychiatry, 56: 651–659, 1946. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Semmes RE, Murphy F. The Syndrome of Unilateral Rupture of the Sixth Cervical Intervertebral Disc. J. A. M. A. 1943;121:1209–1214. [Google Scholar]

- Forester O. The Dermatomes in Man. Brain. 1933;56:1–39. [Google Scholar]

- Nachlas, I. W.: Scalenius Anticus Syndrome or Cervical Foraminal Compression. Southern Med. Jr. 35: 663–667, July ’42.

- Nachlas, I. W.: Brachialgia, Jr. B. & J. Surg. 26: 177–184, Jan. ’44.

- Bucy, P. C. & Chenault, H.: Compression of Seventh Cervical Nerve Root by Herniation of Disc. J. A. M. A. 126: 26–27, Sept. 2, ’44.

- Stookey B. Compression of Spinal Cord and Nerve Root by Herniation of Nucleus Pul-posus in Cervical Region. Arch. Surg. 1940;40:417–432. [Google Scholar]

- Cramer, F., McGowan, F. J.: Role of Nucleus Pulposus in Pathogenesis of so-called Recoil Injuries of the Cord. S. G. & O. 79: 516–521, Nov. ’44.

- Codman EA. The Shoulder. Boston: The Author; 1934. [Google Scholar]

- Bradford FK, Spurling RG. The Intervertebral Disc. Springfield: Thomas; 1941. [Google Scholar]

- McNaughton, F. L.: Neurological Aspects of Shoulder Pain. Shoulder Lesions. Moselly, H. F. Springfield, Thomas, 1945.

- Kellgren JH, Lewis T. Pain, Lewis. New York: MacMillan; 1942. [Google Scholar]

- Oppenheimer, A.: “The Swollen Atrophic Hand.” S. G. & O. Oct. ’38. 67: 446–450.

- Cunningham A. Textbook of Anatomy. : Oxford Univ. Press; 1937. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.