Abstract

This Classic article is a reprint of the original work by Albert P. Iskrant, MA, FAPHA, The Etiology of Fractured Hips in Females. An accompanying biographical sketch on Albert P. Iskrant, MA, FAPHA, is available at DOI 10.1007/s11999-010-1268-x. The Classic Article is ©1968 by the American Public Health Association and is reprinted with permission from Iskrant AP. The etiology of fractured hips in females. Am J Public Health. 1968;58:485–490. The article can also be accessed on the American Journal of Public Health web site at http://ajph.aphapublications.org/cgi/reprint/58/3/485.

Falls are the leading cause of all accidental deaths in elderly white women, and fractures usually of the lower limb account for most of the deaths. These appear to be chiefly associated with ‘‘bone fragility,” a condition most prevalent in elderly white women. Both osteoporosis and deaths from falls seem to be lower where the drinking water has a high fluoride content.

Falls are the leading cause of non-transport accidental death in all persons and the leading cause of all accidental death in elderly white females in the United States. About three-quarters of all deaths from falls occur to persons aged 65 and over. Almost 90 per cent of the deaths from falls in the white female are to persons 65 and over but only about two-thirds of the fall deaths to white males involve those 65 and over. In contrast to death, injury from falls is most frequent in youth.

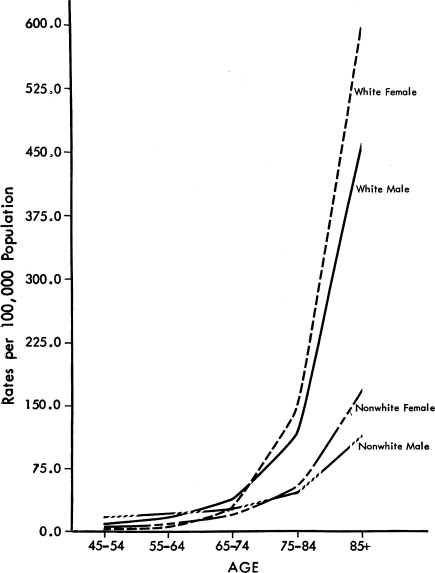

The death rate for falls is moderately high in the preschool child, extremely low in children of school age, and extremely high in the older age groups with rates increasing with age. For persons under 45 years of age, the highest rates are in infants under one year of age. Figure 1 shows the fall death rates for ages 45 and over for 1959–1961 and it may be noted that up to about age 65 male rates are higher than female and nonwhite higher than white. In the older age groups white females have the highest rates followed by white males, with nonwhite males having the lowest rates. Injuries from falls show somewhat the same sex pattern, with the male rate higher than the female throughout the school years, and the female rate becoming relatively higher with advancing age.

Fig. 1.

Annual death rates for falls by age, color, and sex, United States, 1959–1961, persons age 45 and over. Data for this figure were prepared using funds from PHS Research Grant RG-8262 from the National Institutes of Health, Public Health Service.

Studies of Injuries from Falls

Fracture is the most common type of injury involved in deaths from falls, with hip fracture the leading injury in elderly persons, especially females. A special tabulation prepared by the Illinois Department of Public Health, for deaths of residents of that state for the years 1957–1961, shows fractures responsible for over three-quarters of the deaths from falls. Fractures of the lower limb (N820-829) accounted for about half of these deaths and fractures of the skull and face for about one-fifth. Tabulations by sex and age were not prepared at that time but our information is that skull fractures decrease with age as a cause of death and fractures of the hip (femur) increase with age as a cause of death. Also, fractures of the femur become more common in elderly females. Falls “on the same level” increase in importance in elderly females more than in males.

From our epidemiologic studies on nonfatal injuries in several areas we note that, in the 65 and over age group, fractures are always a higher proportion of the injuries incurred in falls for females (47 per cent in age group 65–69 to 65 per cent in 80+) than for males (42 per cent to 49 per cent). “Hip fractures” as a percentage of fall injuries show even more of an excess in females and this percentage also increases with age (3 per cent to 30 per cent for females compared with 2 per cent to 10 per cent for males).

In an epidemiologic study carried out in a northeastern community on accidental injuries to elderly persons treated in hospitals, we found that about 85 per cent of the injuries were the result of falls. Females out-numbered males about three to one. Injuries from falls occurred outdoors more frequently than indoors for males, and indoors more frequently for females. Of the falls occurring indoors, no environmental cause was apparent in almost one-half the cases and almost all of these occurred “on the same level.” In some of these instances the victim stated that there was dizziness or a “spell,” but in many instances “just fell” was given as the reason. Of the “no apparent cause” injuries about one-half were hip fractures, and of the hip fractures almost two-thirds had “no apparent cause.”

Since then we have investigated fall injuries in other geographic areas and we consistently run into large numbers of hip fractures that seem to be associated with falls on the same level or with moderate trauma—casual ambulation or getting out of bed or a chair. In 1824, Cooper [1] noted that fractures of the neck of the femur were usually the result of “moderate” trauma. Others have called this “minimal” trauma and described it as that occuring without outside force. We have classified our cases of fractured femurs into falls on the same level (those caused by moderate trauma) and those caused by more severe trauma, including motor vehicle accidents. Where identification was possible the ratio of upper to lower femur was 6 to 1 for moderate trauma and 1 to 2 for more severe trauma. Also, the degree of trauma seemed to be higher in males than females and to decrease with age. To summarize from our findings: fractures of the upper femur seemed to be associated with moderate trauma, with advancing age, and with “femaleness.” It is interesting to note Bruns’s findings in 1882 that fractures of the upper (proximal) femur were 6 to 1 male to female in ages under 50 and 1 to 2.5 in ages over 50 [2].

When all fractures are considered, data from the National Health Survey show the peak rate in males in the 15–24 age group with a declining rate with increasing age. In females, however, the rate increases with age, reaching its peak in the 65 and over age group. Moreover, the fracture rate is higher in elderly females than elderly men. When only fractures of the femur are considered, the rate for females 65 and over is almost eight times that of males 65 and over (9 to 1.2). The rate for females 65 and over is higher than for any other age-sex group [3].

Osteoporosis

Our epidemiologic studies, in conjunction with a review of the literature, strongly suggest that hip fractures, especially in elderly females, are highly associated with “bone fragility.” The late Dr. Frank Reynolds of the New York State Health Department, who cooperated with us in our study on elderly persons, suggested that this “fragility” was osteoporosis. In reviewing the literature on the subject, it seemed that the condition was more prevalent in females than males and in white than nonwhite. These opinions were in accord with our previously observed pattern of the deaths from falls illustrated in Fig. 1.

It should be made clear at this point that there is no suggestion that osteoporosis causes all upper femur fractures, but that it is one of the factors associated with them. Whether the fracture precedes the fall or vice versa is a secondary point. What is important is that osteoporosis appears to increase the likelihood of a fracture of the upper femur in conjunction with moderate trauma. The association of osteoporosis and fractures does not preclude such studies as those by Boucher [4] on the maintenance of balance and Sheldon [5] on the control of posture and gait. As in other types of injury we reject the unicausal theory, but believe that bone fragility is one of the important factors associated with fractured hips and, therefore, death, hospitalization, and immobility.

We therefore approached Dr. Richmond Smith of Ford Hospital, Detroit, with a proposal for a cooperative study whereby a group of elderly white women would be examined for and classified by the degree of osteoporosis. We would then observe their injury experience and see if the incidence of fractured hips was higher in those with osteoporosis than in those without it. Some of the findings from the examination are presented in publications by Dr. Smith [6, 7]. The injury experience of the women and its relation to osteoporosis will be published by us jointly in the near future.

Because of our preliminary findings at Ford Hospital and the statements in the literature, we expanded our hypothesis to all fractures. In the Ford Hospital group it appeared that osteoporosis was most associated with fractures of the wrist bones, radius, upper femur, and ankle bones. Bauer [8] reports on an increasing incidence of fracture of the “distal end of the forearm” in older women. Buhr and Cooke [9] and Alffram and Bauer [10] also reported such findings. Bauer suggested that women between 40 and 60 years of age with fracture of the distal end of the forearm would be likely candidates for fracture of the “proximal” end of the femur 15 to 20 years later.

Although the findings of our study in Ford Hospital will not be ready for publication for some time, we can state that there is a positive association between the incidence of fractures and the degree of osteoporosis in females over 45. There is also a positive association between the incidence of fractures and increasing age. The age-adjusted fracture rate of women with severe osteoporosis was about three times the rate of the “nonosteoporotic” women.

Contribution to Public Health

There may be a question of what all this has to do with injury prevention or how this knowledge can be used other than in changing the classification on the death certificate from accident to diseases of the bone. There are several ways in which this information may make a positive contribution to public health. It may:

Stimulate research into the role of bone fragility in injuries, trusting that increased knowledge of bone structure and injury thresholds will make a positive contribution to injury control.

Institute screening systems for elderly persons and institute treatment systems for those suspected of beginning osteoporosis.

Alert physicians to give special examinations to females who fracture their wrists, forearms, or ankles (possibly with moderate trauma) after age 40 and institute treatment of those with early, or predisposition to, osteoporosis.

Suggest some measures for all women at a certain age (possibly menopause) either individually through diet, estrogens, hormones, and so on, or through some mass measure such as fluoride added to the drinking water.

One of the treatment regimens for osteoporosis includes the use of sodium fluoride added to the diet. It is suggested that sodium fluoride may be successful in reversing the course of osteoporosis in patients over 40 years of age as bones may become more dense because dietary calcium is retained throughout treatment [11]. Research is obviously needed. It is also suggested that fluoridated water may strengthen bones in the elderly and thereby reduce deaths from falls [12].

Leone, et al., found that deaths from falls were lower in an area in Texas with natural fluoride than in an area in Massachusetts without fluoride. Also, it was found that the prevalence of osteoporosis, based on radiological findings, was higher in Framingham, Mass. (0.04 ppm) than in Bartlett, Tex. (8.0 ppm) or in Cameron, Tex. (0.4 ppm) [13].

Goggin, et al., conducted a study in Elmira, N. Y., to test the hypothesis that fluoride added to the water supply would reduce the incidence of femoral fractures in elderly women. Their results did not support this hypothesis, as far as women age 60 and over were concerned, with fluoride added to the water for five years [14].

A recent paper describing a study of persons living in different parts of North Dakota shows a lower prevalence of “reduced bone density,” especially in women, in high fluoride areas than in low fluoride areas [15].

We in the Division of Accident Prevention had the National Center for Health Statistics prepare tabulations of deaths from falls in white persons in 1960 in all “urban places” in the United States. We divided these into four groups: natural fluoride, fluoride added before 1955, fluoride added after 1955, and no fluoride. We found no lower rates in the places with added fluoride than in the places with no fluoride. We compared the rates for white females in naturally fluoridated urban places in states (with five or more urban places naturally fluoridated) with a random sample of urban places in the same states with nonfluoridated water. The following states were involved: California, Colorado, Illinois, Iowa, Louisiana, Michigan, and Texas. The death rate from falls was generally higher in the nonfluoridated urban places than in those with natural fluoridation. Texas was a notable exception, with the death rate for the 65 and over age groups somewhat higher in the fluoridated areas. In general in each of the four age groups, 65–69, 70–74, 75–84, and 85+, the death rate for falls in white females was lower in naturally fluoridated areas than in nonfluoridated areas (Table 1).

Table 1.

| Age groups | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 65–69 | 70–74 | 75–84 | 85+ | 65+ | 75+ | |

| White female | ||||||

| Natural fluoride | 4.03 | 18.85 | 69.05 | 351.82 | 50.33 | 111.61 |

| No fluoride | 11.46 | 27.37 | 91.67 | 375.45 | 62.72 | 142.33 |

| White male | ||||||

| Natural fluoride | 15.78 | 33.75 | 69.44 | 252.07 | 46.37 | 98.10 |

| No fluoride | 22.82 | 36.89 | 88.41 | 325.91 | 58.64 | 124.79 |

It may be noted that for white females the ratio of deaths in “no fluoride” to “natural fluoride” urban places is highest in the age group 65–69 and decreases with age. For elderly white males in the same areas the death rate also is lower in the “fluoride” than the “non-fluoride” urban places but not to the same degree.

To the extent, then, that the death rate for falls indicates the relative prevalence of osteoporosis, it appears that naturally fluoridated drinking water results in a lower incidence of osteoporosis. The lack of association with artificially fluoridated water may be attributed to exposure too late in life, or not prolonged enough to influence the development of osteoporosis. It will be interesting to see the effect of added fluoride when exposure is prolonged and occurs earlier in life (say before menopause). Further research is obviously needed.

Summary

Falls are the leading cause of non-transport accidental deaths in all persons and the leading cause of all accidental deaths in elderly white females. Fractures, usually of the lower limb, account for most of these deaths.

While the death rate for falls is higher in males than females and non-white than white in childhood and early adulthood, patterns are reversed in older years with the elderly white female having by far the highest rates.

Fractures, and therefore deaths from falls, appear to be positively associated with “bone fragility,” especially osteoporosis, a condition considered most prevalent in elderly white females.

The prevalence of osteoporosis and deaths from falls appears to be lower in areas with high fluoride content in the drinking water, especially in elderly white women.

References

- 1.Cooper, A. P. A Treatise on Dislocations and on Fractures of the Joints (4th ed.). London, 1824.

- 2.Brans, P. Die Allgemeine Lehre von den Knochen-bruchen. Deutsche Chirurgie. Vol. 27, Pt. I. Stuttgart, 1882.

- 3.US Public Health Service, National Center for Health Statistics. Types of Injuries, Ser. 10, No. 8 (Apr.), 1964, and unpublished tabulations from the National Health Survey.

- 4.Boucher, C A. Falls in the Home. The Medical Officer (Oct. 16), 1959, pp. 194–195.

- 5.Sheldon, J. H. On the Natural History of Falls in Old Age. Brit. M. J. (Dec. 10), 1960, pp. 1685–1690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Smith RW, Jr, Walker RR. Femoral Expansion in Aging Women: Implications for Osteoporosis and Fractures. Science. 1964;145:156–157. doi: 10.1126/science.145.3628.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith RW, Jr, Rizek J. Epidemiologic Studies of Osteoporosis in Women of Puerto Rico and Southeastern Michigan With Special Reference to Age, Race, National Origin and to Other Related or Associated Findings. Clin. Orthopaedics & Related Res. 1966;45:31–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bauer GCH. Epidemiology of Fracture in Aged Persons: A Preliminary Investigation in Fracture Etiology. Ibid. 1960;17:219–225. doi: 10.1007/s11999-010-1312-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buhr, A. J., and Cooke, A. M. Fracture Patterns. The Lancet (Mar. 14), 1959, pp. 531–536. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Alffram P, Bauer GCH. Epidemiology of Fractures of the Forearm. J. Bone & Joint Surg. 1962;44-A:105–114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rich C, Ensinck J. Effect of Sodium Fluoride on Calcium Metabolism of Human Beings. Nature. 1961;191:184–185. doi: 10.1038/191184a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stare, F. J. Fluoridation Advocated. Letter to the Editor, New York Times (Apr. 19), 1963, p. 42.

- 13.Leone NC, et al. The Effects of the Absorption of Fluoride. Arch. Indus. Health. 1960;21:326–327. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goggin JE, et al. Incidence of Femoral Fractures in Postmenopausal Women. Pub. Health Rep. 1965;80:1005–1012. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bernstein, D. S., et al. The Prevalence of Osteoporosis in High and Low Fluoride Areas of North Dakota. J.A.M.A. (in press). [PubMed]