Abstract

Background

Untreated hip dysplasia can result in a degenerative process joint and secondary osteoarthritis at an early age. While most periacetabular osteotomies (PAOs) are performed to relieve symptoms, the osteotomy is presumed to slow or prevent degeneration unless irreparable damage to the cartilage has already occurred.

Questions/purposes

We therefore determined (1) whether changes in the thickness of the cartilage in the hip occur after PAO, and (2) how many patients had an acetabular labral tear and whether labral tears are associated with thinning of the cartilage after PAO.

Patients and Methods

We prospectively followed 22 women and four men with hip dysplasia with MRI before PAO and again 1 year and 2½ years postoperatively to determine if cartilage thinning (reflecting osteoarthritis) occurred. The thickness of the femoral and acetabular cartilage was estimated with a stereologic method. Three and one-half years postoperatively, 18 of 26 patients underwent MR arthrography to investigate if they had a torn acetabular labrum.

Results

The acetabular cartilage thickness differed between 1 and 2½ years postoperatively (preoperative 1.40 mm, 1 year postoperatively 1.47 mm, and 2½ years postoperatively 1.35 mm), but was similar at all times for the femoral cartilage (preoperative 1.38 mm, 1 year postoperatively 1.43 mm, and 2½ years postoperatively 1.38 mm.) Seventeen of 18 patients had a torn labrum. The tears were located mainly superior on the acetabular rim.

Conclusion

Cartilage thickness 2½ years after surgery compared with preoperatively was unchanged indicating the osteoarthritis had not progressed during short-term followup after PAO.

Introduction

Patients with hip dysplasia are prone to having osteoarthritis of the hip develop at a young age [5, 47]. The reasons for this are not fully understood, but it is generally believed the reduced contact area between acetabulum and the femoral head and a reduced abductor lever arm increase the contact pressures [1, 11, 24]. Such increased contact pressure reportedly results in degeneration (thinning) of cartilage and eventually osteoarthritis [5, 18, 26, 42].

The condition of the acetabular labrum is also important given reports suggesting a degenerated or damaged labrum initiates cartilage degeneration in dysplastic hips [12, 13, 19]. Arthroscopic studies suggest the labrum is affected in 55% to 96% of symptomatic hips [19, 20]. Labral tears presumably result from overload of the acetabular rim [13] and the high strain placed on the labrum from reduced bony support [23, 27].

PAO provides effective correction of hip dysplasia [23] relieves joint pain [17, 35] improves function [44], and one report suggests surgery may alter the natural history of hip dysplasia and improve hip longevity [45]. The preoperative integrity of cartilage is reportedly an important determinant of survival when performing PAO [14, 25, 34, 38], but it is important that the cartilage does not degenerate or further degenerate after PAO. We assume that improving the position of the existing contact surface at PAO will lead to decreased pressures and thereby avoid cartilage degeneration/thinning after PAO.

We therefore asked whether: (1) changes in the thickness of the cartilage in the hip occur after PAO, and (2) how many patients with PAO had acetabular labral tears and whether labral tears were associated with thinning of the cartilage after PAO.

Patients and Materials

We prospectively followed 22 women and four men presenting with 26 dysplastic hips who were scheduled for PAO. Their median age at the time of PAO was 39 years (range, 19–53 years). All patients had spherical femoral heads. The patients had a center-edge angle of Wiberg [46] of 24° or less, osteoarthritis degree 0 or 1 according to the classification of Tönnis [39], closed growth zones in the pelvis, a painful hip, and minimum 110° flexion in the hip. At the time of surgery we did not know if the patients had a labral tear before PAO and even if we suspected a tear, it would not have influenced our choice of treatment. We excluded patients with metal implants, neurologic illnesses, Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease, or sequelae from previous hip surgery. We also excluded patients for whom an intertrochanteric femoral osteotomy was planned. All 26 patients had MRI preoperatively, 25 returned for MRI 1 year postoperatively, and 21 returned 2½ years postoperatively. Eighteen of 26 patients agreed to undergo MR arthrography (MRA) 3½ years after PAO to determine whether they had an acetabular labral tear. The study was approved by our local ethical committee and all patients gave signed consent for participation in the study.

The examinations were performed on a 1.5-T scanner (Siemens Magnetom Symphony, Erlangen, Germany) using a body array surface coil to achieve the optimum balance between the largest possible field of view and the highest possible spatial resolution. Continuous ankle traction with a load of 10 kg was used during MRI to separate the acetabular and femoral cartilages. The traction was applied 5 minutes before the images were obtained. This regimen reportedly separates the surfaces sufficiently to make them distinct [28, 30]. A fat-suppressed 3-D fast low-angle shot (FLASH) sequence was obtained. The FLASH sequence allows thin slices and a 3-D data set to observe the articular cartilage with a high signal and high contrast. The imaging matrix was 256 × 256 and field of view was 220 × 220 mm with a section thickness of 1.5 mm. TR/TE was 60.0/11.0 ms, the flip angle was 50º, and the time of acquisition was 9.38 minutes. Double MRI of the first 13 included patients was performed preoperatively with complete repositioning of the patients and setup to obtain an estimate of precision of the method used calculated as limits of agreement [2]. We computed the levels of agreement (LOA) between repeated stereologic measurements of cartilage thickness obtained by double MRI. Given the first stereologic measurement for acetabular cartilage, we could expect with 95% confidence that the difference to the second measurement would be between −0.17 and 0.13 mm. For the femoral cartilage, the LOA was −0.18 to 0.1 mm.

Field inhomogeneity and gradient nonlinearity of an MR scanner will distort the images. To validate the resolution and spatial linearity of the system, phantom measurements were performed. A phantom (MRI Deluxe Phantom, Data Spectrum Corporation, Hillsborough, NC, USA) with a diameter of 21.6 cm containing inserts for measurement of resolution and linearity was used. The phantom was placed in the magnet’s isocenter and images were acquired using the sequence used for clinical imaging (T1 W 3-D Flash, slice thickness 1.5 mm, pixel resolution 0.43 × 0.43 mm). The spatial linearity and resolution were measured manually using Syngo on a Siemens MR workstation. To validate the linearity the distances between the parallel plates in the insert were measured and compared with the true dimensions as specified by the vendor. For validating the resolution the size of the rods in the resolution insert were measured and compared with the true dimensions. The measurements of both parameters were in good agreement with the dimensions specified by the phantom vendor.

We also investigated whether metallic artifacts from the screws inserted in the pelvis during the PAO posed a potential problem for the methods used. There were only minor artifacts from the titanium screws, and these were in the iliac bone and did not interfere with the measurements of cartilage thickness.

All patients had PAO using the transsartorial approach [40]. The incision was made from the anterior-superior iliac spine descending 6 cm distally. The fascia over the sartorius muscle was incised and the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve was exposed and was noticeable in the operation field throughout surgery. With this approach, the tensor fasciae latae muscle and the abductor muscles are kept intact and the sartorius muscle is split in the direction of the fiber. The pubic bone was osteotomized and under fluoroscopic control, and the ischial osteotomies and posterior iliac osteotomy were performed. The capsule was not opened for inspection of labral tears; we presumed the PAO would normalize the distribution of force in the joint and relieve the strain on the rim and the labrum and therefore alleviate any symptoms of a possible tear of the labrum. If a patient continuously experiences pain after PAO, we obtain an MRA to observe the labrum and if a tear is found, we offer the patient arthroscopy.

While in the hospital (4–5 days), the patients were seen daily by a physiotherapist for active hip ROM exercises. The patients were mobilized 6 hours postoperatively, and on the first day, patients were allowed 30 kg of weightbearing and given instructions in maintaining the weightbearing limit with the use of crutches. From the eighth postoperative week, the patients were allowed full weightbearing.

Four weeks after discharge, rehabilitation was initiated by one of two physiotherapists specialized in orthopaedics. The patients came to the hospital for physiotherapy twice a week and each exercise session was 1 hour with a 30-minute aerobic and strength program followed by a 30-minute program of mobility and gait training in the hydrotherapy pool. Physiotherapy was ended 2 to 3 months after PAO when the physiotherapists assessed that the patient had achieved predetermined functional goals, eg, walking at speed without crutches and the ability to run.

After discharge from the hospital, the patients were seen by the physiotherapist at 8 weeks and by the surgeon at 8 and 24 weeks, 1, 2½, 5, and 10 years. AP hip radiographs were taken at each visit. Patients were asked to assess the degree of pain on a visual analog scale before surgery and 8 weeks after PAO, and a reduction in pain was observed 8 weeks after PAO (Table 1).

Table 1.

Evaluation of radiographic angles and pain before and 8 weeks after PAO in 26 hips

| Parameter | Preoperative | Postoperative | Difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Center-edge angle (degrees; range) | 13 (−27 to 24) | 31 (20 to 40) | 18 |

| Acetabular index angle (degrees; range) | 17 (39 to 7) | 2 (−4 to 10) | −15 |

| Visual analog scale | 7 (4 to 9) | 1 (0 to 4) | −6 |

To assess acetabular correction, the center-edge and acetabular index angles [39] were measured by one observer (IM) on AP radiographs of the pelvis preoperatively and postoperatively. The radiographic data showed correction of these indices (Table 1).

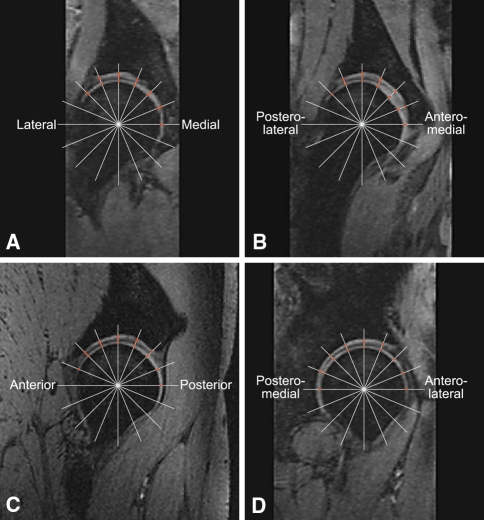

To measure the thickness of the acetabular and femoral cartilage, we used our earlier developed stereologic method that is reliable and time-efficient (requiring approximately 20 minutes per hip) [21, 22]. Stereologic methods are used to obtain quantitative information regarding 3-D structures based on observations from section planes or projections [33]. Stereology can be used to minimize the workload using sampling and still provide reliable quantitative information about the whole structure of interest. This method is based on four images through the center of the femoral head: a true coronal, a true sagittal, an oblique coronal 45° forward angled, and an oblique coronal 45° backward angled. On each of the four images, a grid of 15 to 20 radial test lines was selected and located randomly on the images and where the test lines intercepted the cartilage, the orthogonal distance through the cartilage was measured manually in software (Grain 32, Dimac, and KT Algorithms, Aarhus, Denmark) designed for stereologic purposes (Fig. 1). The approximately 60 to 80 measured distances were summed and the mean thickness of the acetabular and femoral cartilage, respectively, was calculated. Systematic uniformly random sampling ensured the location of the test lines intercepting the cartilage was sampled with the same probability. Therefore, we did not need to use anatomic landmarks to compare preoperative and postoperative cartilage thickness. One observer (IM) measured cartilage thickness on all images. The contrast of the MR images was not adjusted before or during measuring because this may change the appearance of the cartilage boundaries and thus affect the thickness measurements. The cartilage measures were not affected by partial volume because we used center MR images (through the center of the femoral head). It was not difficult to differentiate the labrum from the cartilage on the images. As noted previously, 18 of the 26 patients agreed to undergo MRA 3½ years after PAO to investigate if they had an acetabular labral tear. Applying standardized aseptic technique and guided by fluoroscopy, 8 mL of diluted gadolinium contrast media (Gd-DTPA 2 mmol/L; Magnevist, Schering, Berlin, Germany) was injected into the hip through an anterior approach. Before injection, the intraarticular position of the needle point was verified by injecting a few drops of iodinated contrast media. There were no adverse affects. MRA was performed using the same 1.5-T scanner as used for MRI in this study. Initially, three scout sequences in the axial, sagittal, and coronal planes were obtained. This was followed by T1-weighted sequences with fat suppression: true coronal, oblique axial (parallel to the femoral neck), oblique coronal 45° forward angled, and oblique coronal 45° backward angled (TR/TE 376/20, slice thickness 4 mm, field of view 220 × 220, matrix 256 × 256). Finally, a coronal STIR sequence through the entire pelvis was performed (TR/TE 410/27, TI 170, field of view 400 × 400, matrix 256 × 256). MRA and intraarticular contrast injections were performed by a senior radiologist (JG) specialized in musculoskeletal MRI. All images were assessed by masked rereadings separated by 4 weeks and it was noted where the labral tears were located on the acetabular rim (Fig. 2). The criteria for labral tears seen with MRA were (1) displacement or (2) absence of the labrum; (3) contrast media through the base of the labrum causing detachment with or without displacement; and intrasubstance (4) linear; (5) cystic; or (6) irregular presence of contrast media. Intermediate signal intensity and irregular margins were interpreted as degenerative changes [41].

Fig. 1A–B.

On each of four reconstructed MR images, (A) lateral-medial, (B) posterolateral-anteromedial, (C) anteroposterior, and (D) posteromedial-anterolateral, a grid of 15 to 20 radial test lines was superimposed, and where the test lines intercepted the cartilage, the orthogonal distance through the cartilage was measured manually. The approximately 60 to 80 measured distances were summed, and the mean thickness of the acetabular and femoral cartilage was calculated.

Fig. 2.

The mean acetabular and femoral cartilage thickness and SD in 26 dysplastic hips estimated with MRI and stereology before and after periacetabular osteotomy are shown.

Data for cartilage thickness were normally distributed and we used a repeated measures ANOVA to determine differences in cartilage thickness between preoperative and 1 and 2½ years postoperatively. Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS 11.0 (Chicago, IL) software package.

Results

The acetabular cartilage was thicker (p = 0.04) 1 year after surgery compared with 2½ years postoperatively. Preoperatively, the mean thickness of the acetabular cartilage was 1.40 mm (SD 0.16), 1 year postoperatively 1.47 mm (SD 0.13), and 2½ years postoperatively 1.35 (SD 0.16). The femoral cartilage was unchanged 2½ years postoperatively compared with preoperatively (Fig. 2). The mean thickness for the femoral cartilage before surgery was 1.38 mm (SD 0.18), 1 year postoperatively 1.43 mm (SD 0.13), and 2½ years postoperatively 1.38 mm (SD 0.16).

Seventeen of 18 patients had labral tears at 3½ years, and in the one patient without a tear, degenerative changes of the labrum were identified. At the rereadings of the images, the radiologist reproduced the results regarding presence of labral tears in all cases. The tears were located mainly superior on the acetabular rim and in some cases, the tears extended anterosuperiorly and posterosuperiorly. All tears were identified by contrast media through the base of the labrum (Fig. 3) causing detachment with or without displacement in some cases in combination with linear intrasubstance. Because only one of the patients examined with MRA did not have a labral tear, we did not test for an association between labral tears and cartilage thickness.

Fig. 3.

An axial MRA view shows an anterosuperior labral tear in which intraarticular contrast medium outlines a detachment of the labrum.

Discussion

Untreated hip dysplasia can result in a degenerative process in the joint and eventually secondary osteoarthritis at an early age. We assume that the reduction of excessive joint pressure achieved at PAO promotes the processes involved in cartilage repair and thus prevents cartilage degeneration/thinning after PAO. We therefore asked whether: (1) changes in the thickness of the cartilage in the hip occur after PAO, and (2) how many patients with PAO had acetabular labral tears and whether labral tears were associated with thinning of the cartilage after PAO.

We acknowledge limitations to our study. First, in some patients it was difficult to identify the interface between femoral and acetabular cartilage, although traction was used during MRI to separate the acetabular and femoral cartilage. The traction approach has been used by several authors [16, 28, 30, 31], and is not always well received by patients. We applied 10 kg of traction and found it separated the femoral and acetabular cartilage sufficiently in the patients with little muscle tissue around the hip, whereas the same load had a smaller separating effect on heavier patients with well-developed muscles. We did not apply heavier traction because it possibly would have been uncomfortable for the patients. This may have resulted in an underestimation of the mean cartilage thickness because the areas not fully separated were in the center of the joint where cartilage is thicker compared with the periphery. Second, we had no functional outcome measures although such measures would have been appropriate to collect prospectively. Had we done so, we could have documented the physical function of the included patients before and after surgery and determined whether cartilage thickness is associated with functional outcome. If there is only a weak association between cartilage thickness (or thinning) and function, cartilage thickness may not be a good surrogate for symptoms or progression of osteoarthritis. Third, the use of randomization in stereology and averaging of thickness eliminates the possibility of measuring the same places in the cartilage layer before and after surgery (PAO). Instead, we measured approximately 60 to 80 distances in randomized regions of the acetabular and in the femoral cartilage in each hip, and these measures were averaged so the mean thickness of the acetabular and femoral cartilage could be obtained. Systematic uniform random sampling ensured that all regions of the cartilage were sampled with the same probability before and after the PAO. However, if local areas of cartilage were thinning with time we could not detect such changes and if they were small regions, the mean thickness would be not be substantially less given the large number of points.

We found the mean thickness of the femoral and the acetabular cartilage was unchanged 2½ years compared with preoperatively and we interpret this as suggesting there were no major degenerative changes short-term after PAO. We also found the acetabular cartilage was 0.12 mm thicker 1 year after surgery compared with 2½ years after surgery. This may be explained as an effect of inflammation [8, 9] and concomitant swelling in response to surgery [3]. Another explanation may be cartilage thickness dynamically adapts to increased exercise by hypertrophy [5]. During the first year after PAO, the patients are likely to be more active than before surgery as a result of reduced pain, increased function, and participation in the postoperative rehabilitation program. The first 8 postoperative weeks, the patients are allowed to weightbear with only 30 kg but after that, they put full weight on the surgically treated leg and there are no restrictions for participation in physical activity. Our data suggest cartilage thickness 2½ years after PAO is similar to that before surgery, therefore, we do not know if the increased thickness 1 year after PAO is an indication of regeneration or degeneration of cartilage or if it is a random result. Geometric distortions of the MR images are ruled out as an explanation because our MR physicist has validated the resolution and spatial linearity of the system, and the same protocol was used at all scannings. Others have shown [36] cartilage thickness can be analyzed with high accuracy by an MRI fat-suppressed FLASH sequence with high resolution like we used. The person performing the measurements practiced the method before performing the actual and recorded measures to become experienced in making similar judgments in all images and therefore, the finding of thicker acetabular cartilage is not likely to be a systematic error of measurements. Yet, the increased cartilage thickness is small and within the LOA for our method so we consider it a random result.

All but one patient examined with MRA had a labral tear and we observed degenerative changes of the labrum in the patient who did not have a tear. We did not examine the patients for labral tears preoperatively, therefore, we cannot document that the tears were present before surgery. However, others have found labral tears were present in 64% to 78% of patients with symptomatic hip dysplasia [7, 15]. On the rereadings of MRA, the detection of labral tears was reproduced completely by the radiologist. Others also have reported MRA is a reliable radiographic tool for diagnosing acetabular labral tears [4, 6]. Labral tears may be associated with cartilage disorders in hip dysplasia [10, 29, 32], and we presume there is an association between labral tears and cartilage thinning. Because 17 of 18 patients had labral tears, we could not test for an association between labral tears and cartilage thickness.

The preoperatively and postoperatively measured angles of our patients correspond well with those reported by others [18, 35, 37, 43]. We observed a large reduction in pain 8 weeks after surgery compared with before, also reported by others [17, 35, 44], and PAO performed for the treatment of hip dysplasia evidently reduces the pain.

We did not find gross thinning of the cartilage 2½ years after PAO with the applied stereologic method, although most patients had labral tears. We speculate this is because PAO normalizes the distribution of force in the joint and relieves the strain on the cartilage and the labrum.

Acknowledgments

We thank nurse Jeanette Slot, Department of Radiology, secretary Britta R. Bundgaard, Department of Radiology, and secretary Karen Fousing, Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Aarhus University Hospital, Denmark, for great contributions to the organization of examinations.

Footnotes

One or more of the authors (IM) have received funding from the Danish Rheumatism Association, Aase and Ejnar Danielsens Foundation, and Doctor Soren Segel and Johanne Wiibroe Segel’s Research Foundation.

Each author certifies that his or her institution approved the human protocol for this investigation, that all investigations were conducted in conformity with ethical principles of research, and that informed consent for participation in the study was obtained.

This work was performed at the University Hospital of Aarhus, Aarhus, Denmark.

References

- 1.Armand M, Lepisto J, Tallroth K, Elias J, Chao E. Outcome of periacetabular osteotomy: joint contact pressure calculation using standing AP radiographs, 12 patients followed for average 2 years. Acta Orthop. 2005;76:303–313. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bland JM, Altman DG. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet. 1986;1:307–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Calvo E, Palacios I, Delgado E, Sánchez-Pernaute O, Largo R, Egido J, Herrero-Beaumont G. Histopathological correlation of cartilage swelling detected by magnetic resonance imaging in early experimental osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2004;12:878–886. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2004.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chan YS, Lien LC, Hsu HL, Wan YL, Lee MS, Hsu KY, Shih CH. Evaluating hip labral tears using magnetic resonance arthrography: a prospective study comparing hip arthroscopy and magnetic resonance arthrography diagnosis. Arthroscopy. 2005;21:1250. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2005.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cooperman DR, Wallensten R, Stulberg SD. Acetabular dysplasia in the adult. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1983;175:79–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Freedman BA, Potter BK, Dinauer PA, Giuliani JR, Kuklo TR, Murphy KP. Prognostic value of magnetic resonance arthrography for Czerny stage II and III acetabular labral tears. Arthroscopy. 2006;22:742–747. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2006.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fujii M, Nakashima Y, Jingushi S, Yamamoto T, Noguchi Y, Suenaga E, Iwamoto Y. Intraarticular findings in symptomatic developmental dysplasia of the hip. J Pediatr Orthop. 2009;29:9–13. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0b013e318190a0be. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goldring MB, Marcu KB. Cartilage homeostasis in health and rheumatic diseases. Arthritis Res Ther. 2009;11:224. doi: 10.1186/ar2592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goldring MB, Otero M, Tsuchimochi K, Ijiri K, Li Y. Defining the roles of inflammatory and anabolic cytokines in cartilage metabolism. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67(suppl 3):iii75–iii82. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.098764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guevara CJ, Pietrobon R, Carothers JT, Olson SA, Vail TP. Comprehensive morphologic evaluation of the hip in patients with symptomatic labral tear. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;453:277–285. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000246536.90371.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hipp JA, Sugano N, Millis MB, Murphy SB. Planning acetabular redirection osteotomies based on joint contact pressures. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1999;364:134–143. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199907000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jacobsen S. Adult hip dysplasia and osteoarthritis: studies in radiology and clinical epidemiology. Acta Orthop Suppl. 2006;77:1–37. doi: 10.1080/17453670610045614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klaue K, Durnin CW, Ganz R. The acetabular rim syndrome: a clinical presentation of dysplasia of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1991;73:423–429. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.73B3.1670443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kralj M, Mavcic B, Antolic V, Iglic A, Kralj-Iglic V. The Bernese periacetabular osteotomy: clinical, radiographic and mechanical 7–15-year follow-up of 26 hips. Acta Orthop. 2005;76:833–840. doi: 10.1080/17453670510045453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leunig M, Podeszwa D, Beck M, Werlen S, Ganz R. Magnetic resonance arthrography of labral disorders in hips with dysplasia and impingement. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004;418:74–80. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200401000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Llopis E, Cerezal L, Kassarjian A, Higueras V, Fernandez E. Direct MR arthrography of the hip with leg traction: feasibility for assessing articular cartilage. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008;190:1124–1128. doi: 10.2214/AJR.07.2559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.MacDonald SJ, Hersche O, Ganz R. Periacetabular osteotomy in the treatment of neurogenic acetabular dysplasia. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1999;81:975–978. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.81B6.9700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Matta JM, Stover MD, Siebenrock K. Periacetabular osteotomy through the Smith-Petersen approach. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1999;363:21–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McCarthy JC, Noble PC, Schuck MR, Wright J, The Lee J, Otto E. Aufranc Award: The role of labral lesions to development of early degenerative hip disease. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001;393:25–37. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200112000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McCarthy JC, Noble PC, Schuck MR, Wright J, Lee J. The watershed labral lesion: its relationship to early arthritis of the hip. J Arthroplasty. 2001;16:81–87. doi: 10.1054/arth.2001.28370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mechlenburg I. Evaluation of Bernese periacetabular osteotomy: prospective studies examining projected load-bearing area, bone density, cartilage thickness and migration. Acta Orthop Suppl. 2008;79:4–43. doi: 10.1080/17453690610046558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mechlenburg I, Nyengaard JR, Gelineck J, Soballe K. Cartilage thickness in the hip joint measured by MRI and stereology: a methodological study. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2007;15:366–371. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2006.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mechlenburg I, Nyengaard JR, Romer L, Soballe K. Changes in load-bearing area after Ganz periacetabular osteotomy evaluated by multislice CT scanning and stereology. Acta Orthop Scand. 2004;75:147–153. doi: 10.1080/00016470412331294395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Michaeli DA, Murphy SB, Hipp JA. Comparison of predicted and measured contact pressures in normal and dysplastic hips. Med Eng Phys. 1997;19:180–186. doi: 10.1016/S1350-4533(96)00051-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Murphy S, Deshmukh R. Periacetabular osteotomy: preoperative radiographic predictors of outcome. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2002;405:168–174. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200212000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Murphy SB, Ganz R, Muller ME. The prognosis in untreated dysplasia of the hip: a study of radiographic factors that predict the outcome. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1995;77:985–989. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199507000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nakamura S, Yorikawa J, Otsuka K, Takeshita K, Harasawa A, Matsushita T. Evaluation of acetabular dysplasia using a top view of the hip on three-dimensional CT. J Orthop Sci. 2000;5:533–539. doi: 10.1007/s007760070001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nakanishi K, Tanaka H, Nishii T, Masuhara K, Narumi Y, Nakamura H. MR evaluation of the articular cartilage of the femoral head during traction: correlation with resected femoral head. Acta Radiol. 1999;40:60–63. doi: 10.1080/02841859909174404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Neumann G, Mendicuti AD, Zou KH, Minas T, Coblyn J, Winalski CS, Lang P. Prevalence of labral tears and cartilage loss in patients with mechanical symptoms of the hip: evaluation using MR arthrography. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2007;15:909–917. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2007.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nishii T, Nakanishi K, Sugano N, Masuhara K, Ohzono K, Ochi T. Articular cartilage evaluation in osteoarthritis of the hip with MR imaging under continuous leg traction. Magn Reson Imaging. 1998;16:871–875. doi: 10.1016/S0730-725X(98)00009-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nishii T, Nakanishi K, Sugano N, Naito H, Tamura S, Ochi T. Acetabular labral tears: contrast-enhanced MR imaging under continuous leg traction. Skeletal Radiol. 1996;25:349–356. doi: 10.1007/s002560050094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nishii T, Tanaka H, Sugano N, Miki H, Takao M, Yoshikawa H. Disorders of acetabular labrum and articular cartilage in hip dysplasia: evaluation using isotropic high-resolutional CT arthrography with sequential radial reformation. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2007;15:251–257. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nyengaard JR. Stereologic methods and their application in kidney research. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1999;10:1100–1123. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V1051100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Peters CL, Erickson JA, Hines JL. Early results of the Bernese periacetabular osteotomy: the learning curve at an academic medical center. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88:1920–1926. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.00515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pogliacomi F, Stark A, Wallensten R. Periacetabular osteotomy: good pain relief in symptomatic hip dysplasia, 32 patients followed for 4 years. Acta Orthop. 2005;76:67–74. doi: 10.1080/00016470510030346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schnier M, Eckstein F, Priebsch J, Haubner M, Sittek H, Becker C, Putz R, Englmeier KH, Reiser M. [Three-dimensional thickness and volume measurements of the knee joint cartilage using MRI: validation in an anatomical specimen by CT arthrography] [in German] Rofo. 1997;167:521–526. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1015574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Siebenrock KA, Scholl E, Lottenbach M, Ganz R. Bernese periacetabular osteotomy. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1999;363:9–20. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199906000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Steppacher SD, Tannast M, Ganz R, Siebenrock KA. Mean 20-year followup of Bernese periacetabular osteotomy. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466:1633–1644. doi: 10.1007/s11999-008-0242-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tönnis D. Congenital Dysplasia and Dislocation of the Hip in Children and Adults. Berlin, Germany: Springer; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Troelsen A, Elmengaard B, Soballe K. A new minimally invasive transsartorial approach for periacetabular osteotomy. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90:493–498. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.01399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Troelsen A, Jacobsen S, Bolvig L, Gelineck J, Rømer L, Søballe K. Ultrasound versus magnetic resonance arthrography in acetabular labral tear diagnostics: a prospective comparison in 20 dysplastic hips. Acta Radiol. 2007;48:1004–1010. doi: 10.1080/02841850701545839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Trousdale RT, Ekkernkamp A, Ganz R, Wallrichs SL. Periacetabular and intertrochanteric osteotomy for the treatment of osteoarthrosis in dysplastic hips. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1995;77:73–85. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199501000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Valenzuela RG, Cabanela ME, Trousdale RT. Sexual activity, pregnancy, and childbirth after periacetabular osteotomy. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004;418:146–152. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200401000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bergayk AB, Garbuz DS. Quality of life and sports-specific outcomes after Bernese periacetabular osteotomy. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2002;84:339–343. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.84B3.12421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wenger DR, Bomar JD. Human hip dysplasia: evolution of current treatment concepts. J Orthop Sci. 2003;8:264–271. doi: 10.1007/s007760300046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wiberg G. Studies on dysplastic acetabula and congenital subluxation of the hip joint. Acta Orthop Scand Suppl. 1939;58:1–132. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yanagimoto S, Hotta H, Izumida R, Sakamaki T. Long-term results of Chiari pelvic osteotomy in patients with developmental dysplasia of the hip: indications for Chiari pelvic osteotomy according to disease stage and femoral head shape. J Orthop Sci. 2005;10:557–563. doi: 10.1007/s00776-005-0942-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]