While several forms of tremor are common in multiple sclerosis (MS), orthostatic tremor (OT) has not been reported20.

A 38 year old female, diagnosed with clinically definite relapsing remitting MS at the age of 27, presented following initial improvement from a relapse affecting ambulation, complaining of tremor affecting her legs associated with an intense feeling of unsteadiness. The tremor was not present when sitting but appeared upon standing (see video). It was reduced but not relieved by walking. Neurological examination demonstrated increased tone in the legs, ankle clonus, pyramidal weakness in the left leg (MRC grade 4), symmetrical hyperreflexia, extensor plantar responses, mild left upper limb dysmetria, mild bilateral heel-shin ataxia, impaired proprioception at the hallux bilaterally and absent vibration sense to the knee. These examination findings had remained stable for several years (outside of acute relapses) and until she developed OT had not prevented independent ambulation.

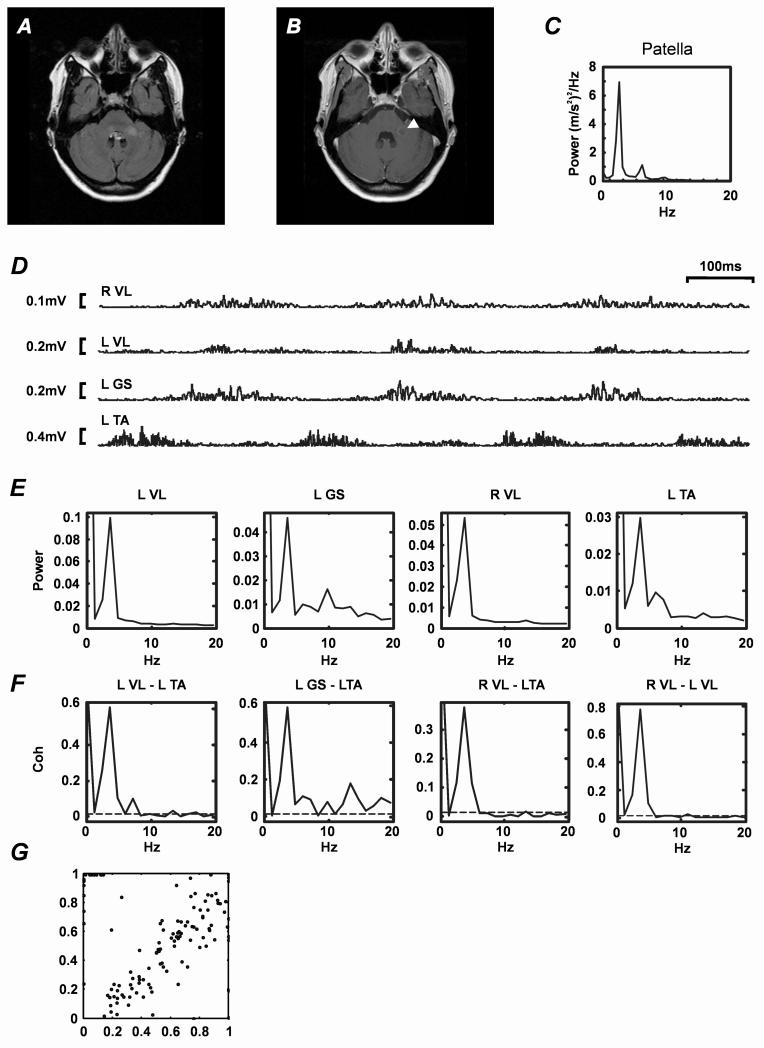

MRI showed active disease with several periventricular lesions in frontal and parietal cortex, and one lesion within the left brachium pontis (Figure A), which enhanced with gadolinium (Figure B).

Figure. Radiology and clinical neurophysiology.

A. MRI brain. Axial FLAIR sequence showing left middle cerebellar peduncle (brachium pontis) lesion consistent with demyelination. B. Equivalent axial gadolinium enhanced T1-weighted MRI sequence. Note that the area of active inflammation (indicated by arrow head) co-localises with the lesion shown in A. C. Tremor power spectrum (data obtained from accelerometer attached to the left patella during stance). D. Rectified EMG recorded from left tibialis anterior (L TA), left gastrocnemius-soleus (L GS), left vastus lateralis (L VL) and right vastus lateralis (R VL) muscles while the patient was standing. Each trace represents one second of data. EMG bursts have a duration of approximately 100 ms (see timebase, top right). Voltage calibration bars are shown to the left of each trace. E. EMG power spectra (expressed as a fraction of total power) derived from EMG recordings illustrated in A (data length 340s). F. Intermuscular coherence spectra. Muscle pairs used to calculate coherence spectra are indicated above each plot. Data points above the dashed lines indicate significant coherence (P<0.05)15 G. Phase resetting plot. Each point represents the effects of one tendon tap stimulus delivered to the patella tendon. Abscissa represents phase of 4Hz oscillation in patella acceleration prior to a tap and ordinate represents phase one cycle following stimulation; phase in both cases is expressed as a fraction of an oscillation cycle. Linear dependence indicates that the tap stimulus did not affect the phase of ongoing tremor.

Electrophysiology showed no evidence of axial or appendicular tremor while seated, but as the patient stood tremor appeared in the legs and trunk. The tremor power spectrum obtained from an accelerometer affixed to the left patella (Figure C) showed a dominant peak at ~4Hz and a smaller sub-harmonic at ~8Hz. Raw rectified EMG recorded using adhesive electrodes from left tibialis anterior (gain 500-5000; band pass filtered 30Hz-2kHz; 5kHz digitization) whilst standing contained four 100ms bursts of EMG per second (Figure D). Frequency domain analysis (see normalised power spectra in Figure E) confirmed that the dominant frequency was ~4Hz. In the left gastrocnemius-soleus and tibialis anterior power spectra there were small additional 8-15Hz sub-peaks. Coherence analysis (see14 15) confirmed that there was significant unilateral and bilateral EMG-EMG coherence not only at tremor frequency but also in the 8-12Hz and 13-18Hz ranges, suggesting that other common frequencies might also be driving lower limb tremor (Figure F).

The effects of patella tendon stimulation on OT were also investigated (Figure G). The linear relationship between tremor phase before and after a tendon tap confirmed that this form of muscle afferent stimulation could not reset the phase of the tremor, as previously described in slow4 and fast OT16, 17.

Pharmacological treatment (i.e. clonazepam, levetiracetam, L-DOPA, gabapentin) was either ineffective or produced intolerable side effects.

Orthostatic tremor (OT) is a rare form of action tremor affecting the legs and trunk. It appears on standing, is associated with a profound and disabling sense of unsteadiness and is relieved by sitting, walking or the use of a support. Two types of OT are recognized: fast OT, characterised by bursts of muscle activity at 13-18 Hz 1-3; and slow OT 4, 5, with a frequency of 3-8 Hz.

Slow OT was first described in 1986 in a family with essential tremor5. Subsequently it has been described in patients with Parkinson’s disease and parkinsonism6-8, and in one patient two months after resection of a cavernoma involving the right brachium pontis 9 (cf. Figure A-B). Idiopathic slow OT, in the absence of primary or associated neurological disease has also been described 4.

In slow OT EMG recordings from leg, trunk and arm muscles demonstrate regular 70-120 ms bursts of activity in the 4-6 Hz range8. Coherence analysis reveals powerful coupling between EMG recorded from lower limb, upper limb and axial muscles both unilaterally and bilaterally, at tremor frequency, which is absent in controls under normal conditions 10 and patients with orthostatic myoclonus 8. Treatment with clonazepam is reportedly helpful; if there is associated parkinsonism anecdotal evidence to supports the use of L-dopa, dopamine receptor agonists or trihexyphenidyl, with or without clonazepam 11, 12.

Although OT has not previously been described in MS, the spastic-ataxic gait sometimes encountered in MS can be mistaken for OT22. This is partly because of the subjective sense of unsteadiness, but also because the frequency of clonus (~4 Hz) 23 can resemble tremor. Clonus, which is easily re-set by stimulating muscle afferents 24, did not contribute to the OT observed in our patient because her tremor could not be entrained by tendon vibration (see Fig. G).

Acknowledgement

Funded by The Wellcome Trust.

Research activities of MRB, KMF and SNB are supported by grants from The Wellcome Trust, MRC, BBSRC, EPSRC and UCB Pharma held by SNB.

Footnotes

Disclosure statement

MRB is employed by the NHS and NIHR. MED and HML are NHS employees. SNB and KMF are employees of Newcastle University.

SNB and KMF are engaged as consultants to Cambridge Pharmaceuticals on an unrelated project.

MED has received honoraria from BiogenIdec, Bayer Schering, Merck Serono and Teva.

HML, SNB, MRB and KMF have received travel grants from UCB Pharma.

The authors have no conflict of interest.

Video Legend

A. Standing. Initially the patient is seated and there is no lower limb or axial tremor. As she stands up marked axial and lower limb tremor appears. B. Walking. As the patient walks, with the aid of two sticks, the tremor appears to improve. However, there was no subjective change in the sensation of unsteadiness. C. Lower limb examination. The patient demonstrates evidence of mild heel-shin ataxia, which is worse on the left. D. Co-contraction. While supine the patient was asked to raise her legs with her feet in plantar flexion and to co-contract her leg muscles. During this manoeuvre there is no visible tremor (tremor can only be detected with accelerometry). E. Upper limb examination. Assessment of tremor in the upper limbs only demonstrated mild terminal tremor on the left. F. Eye movements. Only smooth pursuit was tested, which was normal.

References

- 1.Pazzaglia P, Sabattini L, Lugaresi E. Su di un singolare disturbo della stazione eretta (observazione di tre casi) Riv Sper Freniatr. 1970;94:450–457. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heilman KM. Orthostatic tremor. Archives of neurology. 1984;41(8):880–881. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1984.04050190086020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thompson PD, Rothwell JC, Day BL, et al. The physiology of orthostatic tremor. Archives of neurology. 1986;43(6):584–587. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1986.00520060048016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Uncini A, Onofrj M, Basciani M, Cutarella R, Gambi D. Orthostatic tremor: report of two cases and an electrophysiological study. Acta neurologica Scandinavica. 1989;79(2):119–122. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.1989.tb03722.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wee AS, Subramony SH, Currier RD. “Orthostatic tremor’ in familial-essential tremor. Neurology. 1986;36(9):1241–1245. doi: 10.1212/wnl.36.9.1241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim JS, Lee MC. Leg tremor mimicking orthostatic tremor as an initial manifestation of Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 1993;8(3):397–398. doi: 10.1002/mds.870080331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thomas A, Bonanni L, Antonini A, Barone P, Onofrj M. Dopa-responsive pseudo-orthostatic tremor in parkinsonism. Mov Disord. 2007;22(11):1652–1656. doi: 10.1002/mds.21621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leu-Semenescu S, Roze E, Vidailhet M, et al. Myoclonus or tremor in orthostatism: an under-recognized cause of unsteadiness in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2007;22(14):2063–2069. doi: 10.1002/mds.21651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Benito-Leon J, Rodriguez J, Orti-Pareja M, Ayuso-Peralta L, Jimenez-Jimenez FJ, Molina JA. Symptomatic orthostatic tremor in pontine lesions. Neurology. 1997;49(5):1439–1441. doi: 10.1212/wnl.49.5.1439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sharott A, Marsden J, Brown P. Primary orthostatic tremor is an exaggeration of a physiological response to instability. Mov Disord. 2003;18(2):195–199. doi: 10.1002/mds.10324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gerschlager W, Munchau A, Katzenschlager R, et al. Natural history and syndromic associations of orthostatic tremor: a review of 41 patients. Mov Disord. 2004;19(7):788–795. doi: 10.1002/mds.20132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wills AJ, Brusa L, Wang HC, Brown P, Marsden CD. Levodopa may improve orthostatic tremor: case report and trial of treatment. Journal of neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry. 1999;66(5):681–684. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.66.5.681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elble RJ, Koller WC. Tremor. Johns Hopkins University Press; Baltimore: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baker SN, Olivier E, Lemon RN. Coherent oscillations in monkey motor cortex and hand muscle EMG show task-dependent modulation. The Journal of physiology. 1997;501(Pt 1):225–241. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1997.225bo.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Evans CM, Baker SN. Task-dependent intermanual coupling of 8-Hz discontinuities during slow finger movements. The European journal of neuroscience. 2003;18(2):453–456. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02751.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Britton TC, Thompson PD, van der Kamp W, et al. Primary orthostatic tremor: further observations in six cases. Journal of neurology. 1992;239(4):209–217. doi: 10.1007/BF00839142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Spiegel J, Fuss G, Krick C, Dillmann U. Impact of different stimulation types on orthostatic tremor. Clin Neurophysiol. 2004;115(3):569–575. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2003.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gabellini AS, Martinelli P, Gulli MR, Ambrosetto G, Ciucci G, Lugaresi E. Orthostatic tremor: essential and symptomatic cases. Acta neurologica Scandinavica. 1990;81(2):113–117. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.1990.tb00944.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Manto MU, Setta F, Legros B, Jacquy J, Godaux E. Resetting of orthostatic tremor associated with cerebellar cortical atrophy by transcranial magnetic stimulation. Archives of neurology. 1999;56(12):1497–1500. doi: 10.1001/archneur.56.12.1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alusi SH, Worthington J, Glickman S, Bain PG. A study of tremor in multiple sclerosis. Brain. 2001;124(Pt 4):720–730. doi: 10.1093/brain/124.4.720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Trip SA, Wroe SJ. Primary orthostatic tremor associated with a persistent cerebrospinal fluid monoclonal IgG band. Mov Disord. 2003;18(3):345–346. doi: 10.1002/mds.10328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alusi SH, Glickman S, Aziz TZ, Bain PG. Tremor in multiple sclerosis. Journal of neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry. 1999;66(2):131–134. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.66.2.131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wallace DM, Ross BH, Thomas CK. Motor unit behavior during clonus. J Appl Physiol. 2005;99(6):2166–2172. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00649.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rossi A, Mazzocchio R, Scarpini C. Clonus in man: a rhythmic oscillation maintained by a reflex mechanism. Electroencephalography and clinical neurophysiology. 1990;75(2):56–63. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(90)90152-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pittock SJ, McClelland RL, Mayr WT, Rodriguez M, Matsumoto JY. Prevalence of tremor in multiple sclerosis and associated disability in the Olmsted County population. Mov Disord. 2004;19(12):1482–1485. doi: 10.1002/mds.20227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]