Abstract

We review the role of cadherins and cadherin-related proteins in human cancer. Cellular and animal models for human cancer are also dealt with whenever appropriate. E-cadherin is the prototype of the large cadherin superfamily and is renowned for its potent malignancy suppressing activity. Different mechanisms for inactivating E-cadherin/CDH1 have been identified in human cancers: inherited and somatic mutations, aberrant protein processing, increased promoter methylation, and induction of transcriptional repressors such as Snail and ZEB family members. The latter induce epithelial mesenchymal transition, which is also associated with induction of “mesenchymal” cadherins, a hallmark of tumor progression. VE-cadherin/CDH5 plays a role in tumor-associated angiogenesis. The atypical T-cadherin/CDH13 is often silenced in cancer cells but up-regulated in tumor vasculature. The review also covers the status of protocadherins and several other cadherin-related molecules in human cancer. Perspectives for emerging cadherin-related anticancer therapies are given.

The epithelial–mesenchymal transition is a critical stage in malignancy. Changes in the type and levels of cadherins a cell expresses can promote or suppress this transition.

INTRODUCTION—DYSREGULATION OF CADHERIN FAMILY MEMBERS IN CANCER

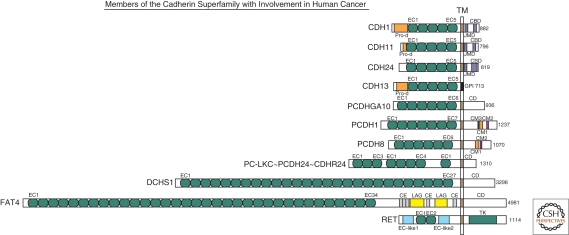

Cell–cell adhesion determines cell polarity and participates in cell differentiation and in establishment and maintenance of tissue homeostasis. During oncogenesis, this organized adhesion is disturbed by genetic and epigenetic changes, resulting in changes in signaling, loss of contact inhibition, and altered cell migration and stromal interactions. A major class of cell–cell adhesion molecules is the cadherin superfamily. Its prototypic member, E-cadherin, was characterized as a potent suppressor of invasion and metastasis in seminal studies dating back to the 1990s (reviewed by van Roy and Berx 2008). Since then, many more cadherins and cadherin-related proteins have been identified (Fig. 1) (reviewed by Hulpiau and van Roy 2009), and an increasing number has been implicated in cancer as putative tumor suppressors or as proto-oncogenic proteins. Here we discuss the structural and functional aberrations of cadherin family members in cancer and their roles in cancer initiation and progression.

Figure 1.

Schematic overview of representative human members of the cadherin superfamily with reported involvement in cancer (modified after Hulpiau and van Roy 2009). All proteins are drawn to scale and aligned at their transmembrane domain (TM). Their total sizes are indicated on the right (number of amino acid residues). The following protein domains are shown: CBD, (conserved cadherin-specific) catenin binding domain; CD, unique cytoplasmic domain; CE, Cysteine-rich EGF repeat-like domain; CM1 to CM3, conserved motifs in the CDs of δ-protocadherins; EC, extracellular cadherin repeat; GPI, glycosylphosphatidylinositol anchor; JMD, (conserved cadherin-specific) juxtamembrane domain; LAG, laminin A globular domain; Pro-d, prodomain; TK, tyrosine kinase domain. On the basis of a phylogenetic analysis (Hulpiau and van Roy 2009), it was proposed that protocadherin LKC (PC-LKC or protocadherin-24) should be renamed (CDHR24).

E-CADHERIN

Most human tumors are carcinomas derived from epithelial tissues, in which E-cadherin is the prototypic cadherin. Epithelial tumors often lose E-cadherin partially or completely as they progress toward malignancy (reviewed by Birchmeier and Behrens 1994; Christofori and Semb 1999; Strumane et al. 2004). Epithelial ovarian cancers are exceptional because expression of E-cadherin in inclusion cysts, derived from ovarian surface epithelium with little or no E-cadherin, appears to be essential for tumorigenesis in this organ (Sundfeldt 2003; Naora and Montell 2005). Another exception is inflammatory breast cancer, a distinct and aggressive form of breast cancer in which the expression of E-cadherin is consistently elevated regardless of the histologic type or molecular profile of the tumor (Table 1) (Alpaugh et al. 1999; Kleer et al. 2001). However, most studies have shown both strong anti-invasive and antimetastatic roles for E-cadherin (Frixen et al. 1991; Vleminckx et al. 1991; Perl et al. 1998). The possible functional implications, which were reviewed recently (Jeanes et al. 2008), include the sequestering of β-catenin in an E-cadherin-catenin adhesion complex (Fig. 3), leading to inhibition of its function in the canonical Wnt pathway (Fig. 4), besides inhibition of EGF receptor signaling and contribution to epithelial apico-basal polarization. We focus here on the different mechanisms for E-cadherin inactivation in malignant tumors, which include mutations, epigenetic silencing, and increased endocytosis and proteolysis (Fig. 2; Table 1).

Table 1.

Representative abnormalities of cadherin superfamily members in cancer

| Protein | Human gene | Tumor-associated abnormalities | Tumor type1 | Clinical correlates2 | Selected references |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E-cadherin | CDH1 | LOH | Numerous | Malignant progression | (Reviewed in Strumane et al. 2004) |

| Promoter methylation | Numerous | Malignant progression | (Reviewed in Strumane et al. 2004) | ||

| Germline mutations | Gastric (DGC) Breast (ILC) |

Hereditary diffuse gastric cancer (HDGC) syndrome |

(Guilford et al. 1998) | ||

| Somatic mutations | Breast (ILC) Gastric (DGC) Pancreas |

Highly invasive growth pattern | (Berx et al. 1998) | ||

| Up-regulated expression | Epithelial ovarian cancer | Tumorigenesis | (Reviewed in Sundfeldt 2003; Naora and Montell 2005) | ||

| Overexpression | Breast (IBC) | Promotes tumor emboli formation | (Kleer et al. 2001) | ||

| N-cadherin | CDH2 | Up-regulation (cadherin switching) | Breast Pancreatic Prostate Melanoma |

Enhanced migration and invasion, increased metastasis; poor prognosis | (Reviewed in Hazan et al. 2004; Wheelock et al. 2008) |

| P-cadherin | CDH3 | Up-regulation (cadherin switching) | Breast Gastric Pancreatic (PDAC) |

Enhanced migration and invasion, poor prognosis | (Paredes et al. 2005; Taniuchi et al. 2005) |

| Down-regulation | Melanoma | Increased invasion and metastasis | (Sanders et al. 1999) | ||

| R-cadherin | CDH4 | Promoter methylation | Colorectal Gastric |

Early event | (Miotto et al. 2004) |

| Cadherin-11 = OB-cadherin | CDH11 | Up-regulation (cadherin switching) | Breast Prostate |

High grade cancer; prostate cancer metastasis to bone | (Bussemakers et al. 2000; Tomita et al. 2000; Chu et al. 2008) |

| VE-cadherin | CDH5 | Overexpression | Melanoma | Vasculogenic mimicry; malignant progression | (Hendrix et al. 2001) |

| T-cadherin | CDH13 | Decreased expression | Breast | Increased tumorigenesis | (Lee 1996) |

| Promoter methylation | Breast Lung (NSCLC) Prostate Colon (adenomas and CRC) Pancreas Gastric HCC Esophageal adenocarcinoma Bladder Chronic myeloid leukemia |

Increased tumorigenesis; malignant progression; early recurrence; poor prognosis | (Sato et al. 1998; Maruyama et al. 2001; Toyooka et al. 2001; Toyooka et al. 2002; Roman-Gomez et al. 2003; Hibi et al. 2004; Sakai et al. 2004; Kim et al. 2005; Wang et al. 2007; Brock et al. 2008; Jin et al. 2008; Yan et al. 2008) | ||

| LOH and promoter methylation | Ovary Skin (BCC and SCC) Diffuse large B cell lymphoma HCC |

Tumor invasion; increased cell proliferation and resistance to apoptosis | (Kawakami et al. 1999; Takeuchi et al. 2002a; Takeuchi et al. 2002b; Ogama et al. 2004; Chan et al. 2008) | ||

| Expression in intratumoral endothelium | Tumor models HCC |

Adiponectin-(co)receptor; increased angiogenesis and tumor progression | (Wyder et al. 2000; Adachi et al. 2006; Philippova et al. 2006; Riou et al. 2006; Hebbard et al. 2008) | ||

| Cadherin 24 | CDH24 | Nonsense mutation | Acute myeloid leukemia | NA | (Ley et al. 2008) |

| LKC-protocadherin=cadherin-related protein 24 | PCDH24=PCLKC | Reduced expression | Colon Liver Kidney |

NA | (Okazaki et al. 2002) |

| Clustered protocadherins | PCDHBx, PCDHGx | Mutations (mostly missense) | Pancreas | NA | (Jones et al. 2008) |

| PCDGGx | Promoter methylation | Astrocytomas Breast |

NA | (Waha et al. 2005) (Miyamoto et al. 2005) |

|

| Protocadherin-1 | PCDH1 | Decreased expression | Medulloblastoma | Unfavorable survival; independent prognosticator | (Neben et al. 2004) |

| Protocadherin-8 | PCDH8 | Reduced transcription, somatic missense, LOH, homozygous deletion, promoter methylation | Breast (tumors and cancer cell lines) | Reduced estrogen receptor and progesterone receptor | (Yu et al. 2008) |

| Protocadherin-9 | PCDH9 | Missense mutation | Pancreas | NA | (Jones et al. 2008) |

| Protocadherin-10 = OL-protocadherin | PCDH10 | Frequent promoter methylation | Nasopharyngeal Esophageal Breast Gastric HCC Hematological (multiple) |

Decreased overall survival in stage I-III gastric cancer patients | (Miyamoto et al. 2005; Ying et al. 2006; Ying et al. 2007; Yu et al. 2009) |

| Protocadherin-17 | PCDH17 | Nonsense and missense mutations | Pancreas | NA | (Jones et al. 2008) |

| Protocadherin-18 | PCDH18 | Missense mutations | Pancreas | NA | (Jones et al. 2008) |

| Protocadherin-20 | PCDH20 | Promoter methylation | Lung (NSCLC) | Shorter overall survival; stage-independent prognosticator | (Imoto et al. 2006) |

| Protocadherin-11Y=PC-protocadherin | PCDH11Y | Increased expression | Prostate | Androgen-resistance; apoptosis-resistance | (Chen et al. 2002; Terry et al. 2006) |

| FAT4 | FAT4 | Promoter methylation | Breast | NA | (Qi et al. 2009) |

| RET | RET | Constitutive activation | Thyroid Multiple endocrine neoplasia |

Causative | (reviewed by Kondo et al. 2006; Zbuk and Eng 2007) |

1BCC, basal cell carcinoma; CRC, colorectal carcinoma; DGC, diffuse gastric carcinoma; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; IBC, inflammatory breast carcinoma; ILC, invasive lobular carcinoma; NSCLC, nonsmall cell lung carcinoma; PDAC, pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma; SCC, squamous cell carcinoma.

2NA: not analyzed in this study.

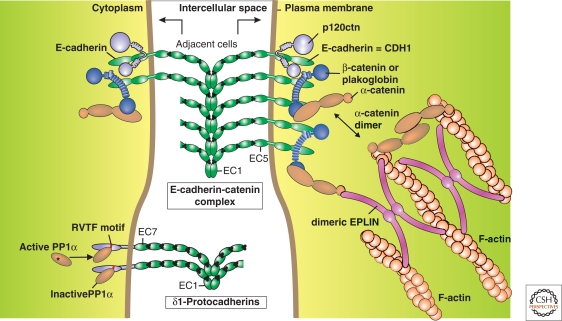

Figure 3.

Schematic overview of the E-cadherin-catenin complex and of δ1-protocadherins at the junction between two adjacent cells (modified, with permission, from Redies et al. 2005; van Roy and Berx 2008). Top: The armadillo catenins p120ctn and β-catenin/plakoglobin bind to, respectively, membrane-proximal and carboxy-terminal halves of the cytoplasmic domain of E-cadherin. This increases junction strength and stability. As extensively described in the literature, both β-catenin and p120ctn also have cancer-related roles in the cytoplasm and in the nucleus. Monomeric α-catenin binds to the E-cadherin cytoplasmic domain via β-catenin, whereas dimeric α-catenin can bind and cross-link filamentous actin (F-actin). Moreover, dimeric EPLIN forms a link between the E-cadherin-catenin complex and F-actin. See text for more details and references. Bottom: The evidence for the depicted δ1-protocadherins structure is circumstantial, but the following features are typical: seven extracellular cadherin repeats (EC) instead of five and a completely different cytoplasmic domain with conserved motifs (CM). The CM3 or RVTF motif has been shown to interact with phosphatase PP1α, probably resulting in its inactivation (reviewed in Redies et al. 2005).

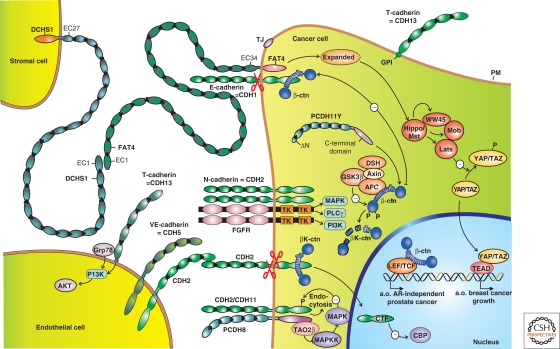

Figure 4.

Selection of expression patterns and activities of members of the cadherin superfamily in cancer. Three cell types are partly depicted: a cancer cell, an endothelial cell, and another type of stromal cell. Protein domains in green are strongly homologous to those in the prototypic E-cadherin/CDH1. Domains in other colors deviate substantially in structure and function. Black dots represent Ca2+ ions. Arrows with minus sign symbols refer to direct or indirect inhibitory influences. Cadherins shown at the cancer cell surface are expressed at the apical membrane (T-cadherin/CDH13 above the tight junction, TJ), or at lateral membranes (E-cadherin/CDH1, N-cadherin/CDH2, cadherin-11/CDH11). The latter three probably occur as cis-homodimers. CDH1 is frequently inactivated in cancer cells, whereas the “mesenchymal” cadherins CDH2 and CDH11 are often up-regulated. CDH2 can interact with fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR), potentiating its signaling through the enzymes MAPK, PLCγ, and PI3K. Cadherins are prone to proteolytic processing (scissors symbols), which releases either the ectodomain or a carboxy-terminal fragment (CTF). In the case of CDH2, this CTF has been shown to enter the nucleus and inhibit the CREB binding protein (CBP). On neural activation, CDH2 and CDH11 associate with protocadherin-8 (PCDH8 or Arcadlin), which results in activation of the MAPKKK TAO2β, eventually leading to endocytosis of the cadherins. PCDH8 is often silenced in cancer cells, but it is unclear whether this is causally linked to up-regulation of mesenchymal cadherins. The transcriptional activity of β-catenin (β-ctn) in a nuclear complex with LEF/TCF, leads, amongst other effects, to androgen receptor (AR)-independent prostate cancer growth. This phenomenon is inhibited by sequestration of β-ctn by E-cadherin or by degradation of β-ctn after phosphorylation (-P) by GSK3β. Degradation of β-ctn occurs in a cytoplasmic degradation complex with APC (adenomatous polyposis coli protein), Axin, and Disheveled (DSH). However, nuclear β-ctn-LEF/TCF activity is stimulated by an unknown mechanism by a cytoplasmic variant of protocadherin-11Y (PCDH11Y) lacking a signal peptide because of a truncated aminoterminus (ΔN). Tumor-associated endothelial cells express VE-cadherin/CDH5, CDH2, and T-cadherin/CDH13. The latter is linked to the PM via a glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) anchor and signals via secreted Grp78/BiP to an anti-apoptotic PI3K-AKT pathway. Dachsous-1 (DCHS1) and FAT4 are both huge cadherin-related proteins, interacting with each other in heterophilic (different protein types) and heterotypic (different cell types) ways. Silencing of human FAT4 is seen in breast cancer and its activation is linked in an unresolved way to the Hippo-YAP pathway, which controls organ size in Drosophila and is affected in several human cancers. See text for details and references. (a.o.) Amongst others; (EC) extracellular cadherin repeat; (PM) plasma membrane; (TK) tyrosine kinase domain.

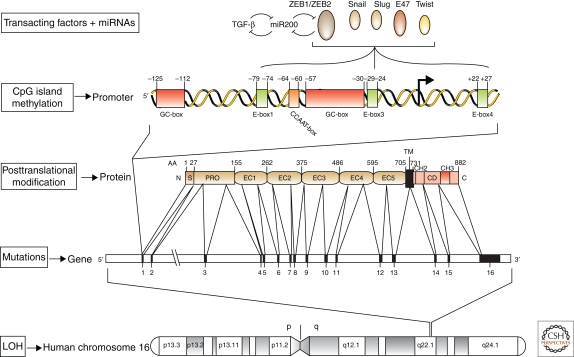

Figure 2.

Various levels at which E-cadherin expression is regulated in human tumors (modified, with permission, from van Roy and Berx 2008). The E-cadherin gene CDH1 is on chromosome 16q22.1 (depicted at the bottom). This region frequently shows loss of heterozygosity (LOH) in different human carcinoma types. Specific inactivating mutations are scattered throughout the whole coding region and are particularly abundant in sporadic lobular breast cancer and diffuse gastric cancer. Germline mutations can also occur; they cause the hereditary diffuse gastric cancer syndrome. Furthermore, post-translational modifications, such as phosphorylation and glycosylation, and proteolytic processing can affect E-cadherin protein functionality. Epigenetic silencing has been associated with CpG methylation in the CDH1 promoter region or with direct binding of specific transcriptional repressors to E-box sequences in this region. The transcriptional repressors ZEB1/δEF1 and ZEB2/SIP1 are repressed in epithelia by the miRNAs of the miR-200 family. In turn, the ZEB transcription factors down-regulate transcription of the miR-200 genes. Thus, a biphasic regulatory system controls the balance between the epithelial and mesenchymal status in response to incoming signals. TGF-β in the tumor microenvironment can induce the expression of ZEB proteins, at least in part by down-regulating the miR-200 family members. This results in a self-enhancing loop that leads to epithelial dedifferentiation and invasion. See text for more details and references. AA, amino acid position; C, carboxy-terminal end; CD, cytoplasmic domain; EC, extracellular cadherin repeat; N, amino-terminal end; PRO, propeptide; S, signal peptide; TM, transmembrane region. The arrows point to the transcriptional initiation start.

Loss of Heterozygosity and Inactivating Mutations in Cancer

Studies on loss of heterozygosity (LOH) of chromosome 16q21-22 hinted at a role for E-cadherin in human cancer (Fig. 2; Table 1). Following the mapping of the human E-cadherin gene CDH1 to chromosome 16q22.1 (Natt et al. 1989; Berx et al. 1995b), several studies showed frequent LOH of 16q in gastric, prostate, hepatocellular and esophageal carcinomas (reviewed by Strathdee 2002; Strumane et al. 2004). LOH at 16q is frequent particularly in breast cancer, where it occurs in ∼50% of all ductal carcinomas (Cleton-Jansen et al. 2001), and even more frequently in lobular breast cancer (Berx et al. 1996).

E-cadherin-inactivating mutations were first described in diffuse gastric cancer (Becker et al. 1993). In sporadic diffuse gastric cancer, somatic mutations preferentially cause skipping of exon 7 or 9, which results in in-frame deletions. Several truncations have also been reported in this histological subtype of tumors (Becker et al. 1994; Berx et al. 1998). Promoter hypermethylation, rather than LOH, accounts here for biallelic CDH1 silencing (Machado et al. 2001). In contrast to these mutation hotspots, E-cadherin inactivating mutations tend to be scattered along the CDH1 gene in sporadic lobular breast carcinomas (Berx et al. 1995a; Berx et al. 1996). In this highly infiltrating cancer type, most CDH1 mutations are out-of-frame mutations predicted to yield secreted truncated E-cadherin fragments or no stable protein. E-cadherin expression is silenced because the mutations are accompanied by CDH1 promoter methylation or LOH (Berx et al. 1996; Berx et al. 1998; Droufakou et al. 2001). Missense mutations are infrequent in these two subtypes of cancer but frequent in monophasic synovial sarcomas (Saito et al. 2001). E-cadherin mutations are rare in carcinomas of bladder, colon, endometrium, lung, esophagus, ovary, and thyroid, and in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (Risinger et al. 1994; Soares et al. 1997; Wijnhoven et al. 1999; Taddei et al. 2000; Endo et al. 2001; Vecsey-Semjen et al. 2002).

Familial aggregation of gastric cancer is well known. These familial cancers can be classified histopathologically into hereditary diffuse gastric cancer (HDGC), familial diffuse gastric cancer (FDGC), and familial intestinal gastric cancer. The International Gastric Cancer Linkage Consortium (IGCLC) established criteria for identifying HDGC families based on the incidence and onset of diffuse gastric cancer (Caldas et al. 1999). Gastric cancers with high incidence and with an index case of diffuse gastric cancer but not fulfilling the IGCLC criteria for HDGC are classified as FDGC (Oliveira et al. 2006).

Germline mutations in the E-cadherin gene were first described in 1998 by Guilford et al. (1998), who identified CDH1-inactivating mutations in three Maori families with early-onset diffuse gastric cancer. Since then, 68 families carrying germline CDH1 mutations have been identified worldwide (Carneiro et al. 2008). CDH1 mutations were found in 30.5% of HDGC families and 13.8% of FDGC families (reviewed in Oliveira et al. 2006). These mutations resemble sporadic mutations in that most of them are predicted to cause premature stop codons caused by nonsense, splice-site, or frameshift mutations. Only some of them were missense mutations (Pereira et al. 2006). Some of these E-cadherin missense mutants are subjected to ER quality control followed by ER-associated degradation (Simoes-Correia et al. 2008). Germline mutations are scattered along the entire gene.

Multiple cases of lobular breast cancer (including mixed ductal and lobular histology) have been reported in families with HDGC (Caldas et al. 1999; Pharoah et al. 2001; Brooks-Wilson et al. 2004; Suriano et al. 2005). The estimated cumulative lifetime risk of breast cancer in women from HDGC families with germline CDH1 mutations is 39% (Pharoah et al. 2001). Remarkably, CDH1 germline mutations can be associated with invasive lobular breast cancer in the absence of diffuse gastric cancer (Masciari et al. 2007). Most of these hereditary tumors are E-cadherin-negative, pointing to a double inactivating mechanism.

Predisposition to diffuse gastric cancer and lobular cancer in patients carrying germline mutations in the E-cadherin gene identify E-cadherin as a tumor suppressor (Dunbier and Guilford 2001). An in vivo role of E-cadherin in cancer progression was supported by demonstrating that expression of a dominant-negative E-cadherin mutant in a mouse pancreatic β-cell tumor model accelerated conversion of adenomas into carcinomas (Perl et al. 1998). In contrast, in mouse models specific loss of E-cadherin in the skin and the mammary gland is not sufficient for tumorigenesis (Boussadia et al. 2002; Tinkle et al. 2004; Tunggal et al. 2005). This ablation caused extensive cell death in the mammary gland, which indicates that the frequent loss of E-cadherin in epithelial cancers, including breast carcinomas, must be accompanied by oncogenic antideath mechanisms. This was shown by combining a floxed Cdh1 gene with the K14-Cre gene, which is expressed at low, stochastic levels in mammary epithelium (Derksen et al. 2006). No abnormalities were seen in these mice, but combined loss of E-cadherin and p53 resulted in accelerated development of malignant mammary carcinomas resembling human infiltrative lobular carcinomas. Ablating both tumor suppressors induced more metastatic spreading, anoikis resistance, and vascularization than loss of p53 alone.

Epigenetic Silencing of the E-cadherin Locus in Cancer

Promoter hypermethylation is an important epigenetic event associated with loss of E-cadherin gene expression during cancer progression (Fig. 2; Table 1). A large CpG island in the 5′ proximal promoter region of the E-cadherin gene (Berx et al. 1995b) shows aberrant DNA methylation in at least eight human carcinoma types and correlates with reduced E-cadherin protein expression (Graff et al. 1995; Yoshiura et al. 1995; Chang et al. 2002; Kanazawa et al. 2002). In cancer cell lines, promoter methylation of the E-cadherin gene is heterogeneous, dynamic, unstable, and associated with allele to allele variability (Graff et al. 1995; Graff et al. 1998; Graff et al. 2000). This is compatible with heterogeneous loss of E-cadherin protein expression, which might be influenced by the tumor microenvironment. CpG island methylation in the CDH1 gene seemingly increases during malignant progression of breast and hepatocellular carcinomas (Kanai et al. 2000; Nass et al. 2000).

Causal involvement of hypermethylation in E-cadherin repression is supported by the reactivation of functional E-cadherin in certain cancer cell lines on treatment with the demethylating agent 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine (5AzaC) (Graff et al. 1995; Yoshiura et al. 1995; Nam et al. 2004). Binding of the methyl-CpG binding proteins MeCP2 and MBP2 to the methylated CpG island of the repressed E-cadherin promoter results in recruitment of HDACs to the promoter area, leading to histone-3 (H3) deacetylation, which is essential for suppressing the methylated E-cadherin gene (Koizume et al. 2002). Interestingly, the methylated CDH1 promoter status in breast cancer cell lines seems to be part of a general transcriptional program that conforms with EMT and increased invasiveness, but diverges from the specific consequence of E-cadherin mutational inactivation (Lombaerts et al. 2006).

Transcriptional Silencing, EMT, and Cancer

Different repressors of E-cadherin transcription have been associated with the progression of multiple cancer types (Fig. 2). Increased Snail expression, common in ductal breast carcinomas, is strongly associated with reduced E-cadherin gene expression (Cheng et al. 2001). High-grade breast tumors and lymph-node positive tumors consistently show strong Snail expression (Blanco et al. 2002). A new role for Snail in tumor recurrence has been inferred from a reversible HER-2/neu-induced breast cancer mouse model (Moody et al. 2005). Also, abnormal expression of Slug has been associated with disease aggressiveness in metastatic ovarian and breast carcinoma (Elloul et al. 2005). Twist, another EMT-regulating transcription factor, is involved in breast tumor metastasis (Yang et al. 2004), and its expression rises as nodal involvement increases (Martin et al. 2005). Strong expression of SIP1/ZEB2, which is associated with loss of E-cadherin expression, was reported in gastric cancer of the intestinal type, but Snail does not seem to be involved in these tumors (Rosivatz et al. 2002). In contrast, Snail is up-regulated in diffuse gastric cancer, a tumor subtype frequently affected by E-cadherin inactivating mutations (Rosivatz et al. 2002). The transcription factor deltaEF1/ZEB1 seems to be downstream of Snail expression (Guaita et al. 2002). Knock-down of deltaEF1/ZEB1 in dedifferentiated human epithelial colon and breast cancer cell lines results in re-expression of E-cadherin and other epithelial differentiation markers (Eger et al. 2005; Spaderna et al. 2006; Spaderna et al. 2008). Though extensive data show that expression of E-cadherin repressors is inversely correlated with expression of E-cadherin, these results should be interpreted carefully because many data are based on RT-PCR and on the use of antibodies with poorly defined specificity.

Recently, induction of expression of E-cadherin transcriptional repressors has been inversely linked with the expression status of the von Hippel-Lindeau (VHL) tumor suppressor (reviewed in Russell and Ohh 2007). Loss of VHL is an early, requisite step in the pathogenesis of clear-cell renal cell carcinoma (CC-RCC) (Lubensky et al. 1996). Activation of HIFα proteins in cells devoid of VHL, including CC-RCC cells, induces transactivation of several E-cadherin repressors, e.g., SIP1/ZEB2 and Snail, which contributes to the particularly malignant character of this tumor type (Esteban et al. 2006; Krishnamachary et al. 2006; Evans et al. 2007).

Regulatory cross-modulation exists between different E-cadherin-repressing transcription factors and specific microRNAs (Fig. 2). Members of the miR-200 family and miR-205 directly target ZEB1/deltaEF1 and ZEB2/SIP1 mRNAs, thereby repressing ZEB1 and ZEB2 protein translation and hence increasing E-cadherin expression (Christoffersen et al. 2007; Hurteau et al. 2007; Burk et al. 2008; Gregory et al. 2008; Korpal et al. 2008; Park et al. 2008). Expression analysis of miRNAs in normal human tissues showed that the miRNAs targeting ZEB family members are particularly abundant in epithelial tissues (Liang et al. 2007). Experimental up-regulation of miR-200c in dedifferentiated metastatic breast cancer cells suppresses their invasive behavior (Burk et al. 2008). Alternatively, ZEB1/deltaEF1 represses transcription of miR-200 family members by binding to E-box elements in the promoter regions of polycistronic primary miRNAs encoding these miRNAs (Bracken et al. 2008; Burk et al. 2008). These different miRNAs are repressed both by TGF-β and by overexpression of the tyrosine phosphatase Pez, which results in EMT with loss of E-cadherin expression (Gregory et al. 2008). In turn, the EMT activator TGF-β2 is also down-regulated by these miRNAs, indicating that ZEB1/deltaEF1 induces a microRNA-mediated feed-forward loop, which can re-enforce EMT (Lopez and Hanahan 2002; Burk et al. 2008).

Increasing evidence shows that diverse solid tumors are hierarchically organized and sustained by a distinct subpopulation of cancer stem cells (CSCs). For breast cancer, Al-Haij et al. (2003) described a CD44high/CD24low cell population that had greater tumor-initiating capacity. Surprisingly, normal mammary epithelial cells could be induced to adopt the stem-cell like CD44high/CD24low expression profile when exposed to TGF-β or on conditional overexpression of the EMT inducing transcription factor Snail or Twist. The resulting population displayed mesenchymal and stem cell markers and acquired stem-cell like properties, including enhanced growth in mammosphere cultures and increased formation of soft agar colonies (Mani et al. 2008). Moreover, activation of the Ras/MAPK signaling pathway in primary human mammary epithelial cells appeared to be crucial for facilitating the emergence of CD44high/CD24low cells (Morel et al. 2008).

Endocytosis and Proteolytic Processing of E-cadherin in Cancer

Multiple mechanisms other than genetic and epigenetic silencing of E-cadherin could serve as alternative ways for disturbing or inhibiting normal E-cadherin function under pathological conditions. As reviewed (van Roy and Berx 2008), E-cadherin is removed from the plasma membrane by endocytosis and recycled to sites of new cell–cell contacts. Abnormal activation of proto-oncogenes, such as c-Met, Src, and EGFR, results in increased phosphorylation of tyrosine residues in the cytoplasmic domain of E-cadherin, which leads to recruitment of the E3-ubiquitin ligase Hakai and subsequently mediates internalization and ubiquitin-dependent degradation of E-cadherin (Fujita et al. 2002; Shen et al. 2008).

Because p120ctn participates in stabilizing the cadherin–catenin complex, many cancer types are characterized by loss or dislocalization of p120ctn (reviewed in van Hengel and van Roy 2007). We recently showed that p120ctn interacts with hNanos1, the human ortholog of the Drosophila zinc-finger protein, Nanos (Strumane et al. 2006). Transcription of hNanos1 mRNA is often suppressed on E-cadherin expression. Conditional expression of hNanos1 in human colon DLD1 cancer cells induces cytoplasmic translocation of p120ctn, up-regulates expression of membrane type 1-matrix metalloproteinase (MT1-MMP) at the mRNA and protein levels, and increases migratory and invasive abilities (Strumane et al. 2006; Bonnomet et al. 2008).

Moreover, matrix metalloproteinases, including stromelysin-1 (MMP3), matrilysin (MMP7), MMP9, and MT1-MMP (MMP14), cleave the E-cadherin ectodomain near the plasma membrane (Fig. 4) (Lochter et al. 1997; Davies et al. 2001; Noë et al. 2001; Covington et al. 2006; Symowicz et al. 2007). Several other proteases, such as the serine protease kallikrein 6 (Klk6), are up-regulated in human squamous skin carcinomas. Ectopic expression of Klk6 in keratinocytes induces E-cadherin ectodomain shedding in parallel with increased levels of mature ADAM10 proteinase (Klucky et al. 2007). Pancreatic adenocarcinomas often overexpress kallikrein-7, which can also generate soluble E-cadherin fragments that may function as pseudoligands to block normal E-cadherin interactions and promote invasion (Johnson et al. 2007). In epithelial ovarian carcinomas, the tumor cells maintain direct contact with ascites, which accumulates high concentrations of the solubilized E-cadherin ectodomain, and thereby promotes disruption of cell–cell junctions and metastatic dissemination (Symowicz et al. 2007). ADAM15, which is associated with progression of breast and prostate cancers, also generates a soluble E-cadherin ectodomain (Najy et al. 2008). This E-cadherin fragment appeared to stabilize heterodimerization of the HER2 (ErbB2) receptor tyrosine kinase with HER3, thus leading to Erk signaling, which stimulates both cell proliferation and migration.

The ectodomain of E-cadherin is also a substrate of secreted cathepsins B, L, and S, but not cathepsin C (Gocheva et al. 2006). This correlates with impaired malignant invasion on ablation of any of these three cathepsins in the mouse pancreatic islet cell carcinogenesis model, RIP1-Tag2, whereas tissue-specific cathepsin C knockout had no effect on either tumor formation or progression. Cathepsins are often secreted by various cells in the tumor microenvironment (Mohamed and Sloane 2006).

MESENCHYMAL CADHERINS AND P-CADHERIN

Loss of expression of E-cadherin (CDH1), P-cadherin (CDH3), or both in invasive tumor cell lines and malignant tissues from breast cancers, prostate cancers, and melanomas is often associated with induced expression of the mesenchymal N-cadherin (CDH2), generally referred to as cadherin switching (reviewed by Tomita et al. 2000; Hazan et al. 2004; Wheelock et al. 2008) (Table 1). E-cadherin down-regulation together with de novo N-cadherin expression is also observed in a Rip1-Tag2 mouse tumor model, in which tumor progression is accelerated by overexpression of IGF1R in the pancreatic β-cells (Lopez and Hanahan 2002). Normally, cadherin-11 (OB-cadherin or CDH11) (Fig. 1) is constitutively expressed in stromal and osteoblastic cells. Its misexpression in carcinoma cell lines and malignant breast and prostate tissues coincides with greater invasiveness and poor prognosis (Table 1) (Pishvaian et al. 1999; Bussemakers et al. 2000; Tomita et al. 2000). Manipulation of cadherin-11 expression in experimental metastasis models for breast and prostate cancers suggests that it promotes homing and migration to bone (Chu et al. 2008; Tamura et al. 2008). In human prostate cancers, cadherin-11 expression increases with progression from primary to metastatic disease in lymph nodes and particularly in bone (Chu et al. 2008).

E-cadherin repressors, such as Snail, ZEB2/SIP1, and Slug, can induce N-cadherin and cadherin-11 expression during EMT, suggesting that this cadherin switch is part of a transcriptional reprogramming of dedifferentiating epithelial cells (Cano et al. 2000; Vandewalle et al. 2005; Sarrio et al. 2008). Overexpression of N-cadherin in epithelial breast tumor cells induces a scattered morphology even when E-cadherin is present, and increases their motility, invasiveness, and metastatic capacity (Nieman et al. 1999; Hazan et al. 2000). This enhanced malignancy can be partly explained: Tumor cells, which express N-cadherin, are more able to interact with N-cadherin-positive tissues, including stroma and endothelium, potentially promoting their access to the vasculature and penetration and survival in secondary organs (Fig. 4) (Hazan et al. 1997; Hazan et al. 2000).

In contrast to the malignant contribution of N-cadherin overexpression in breast tumor cell models, mammary gland tumors arising in a bi-transgenic mouse model overexpressing both N-cadherin and ErbB2/HER-2/neu in a tissue-specific manner are not pathologically different from the tumors in single ErbB2/HER-2/neu transgenic mice (Knudsen et al. 2005). However, coexpression of N-cadherin with polyomavirus middle-T antigen in the mammary epithelium produces breast cancers with greater potential for metastasis to the lung (Hulit et al. 2007). N-cadherin did not enhance tumor onset but affected tumor progression by potentiating oncogenic ERK signaling, leading to MMP-9 up-regulation. These studies suggest that the effects of cadherin switching could occur late in tumor progression and that the impact of abnormal cadherin expression can depend on the cellular context. The concerted action of additional events, such as overexpression of FGF(R), loss of E-cadherin, or up-regulation of MMPs might be required together with N-cadherin up-regulation to promote mammary tumor invasion and metastasis in vivo. In breast cancer cells, N-cadherin and FGF2 synergistically increase migration, invasion, and secretion of extracellular proteases (Hazan et al. 2004).

Mechanistically, N-cadherin is believed to functionally interact with the FGF receptor, causing sustained downstream signaling by phospholipase Cγ, PI(3)K, and MAPK-ERK to promote cell survival, migration, and invasion (Fig. 4) (Suyama et al. 2002). Shedding of N-cadherin by proteases might stimulate FGFR signaling in neighboring cells. Furthermore, presenilin 1 (PS1)/γ-secretase cleaves N-cadherin in the cytoplasmic part to release a free carboxy-terminal 35-kDa fragment, which translocates to the nucleus and binds the transcriptional coactivator CBP (CREB binding protein) (Fig. 4) (Marambaud et al. 2003). This targets CBP for degradation and represses CBP/CREB-mediated transcription.

P-cadherin (CDH3) is expressed abnormally in basal-like breast carcinomas and in most pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas (Table 1) (Paredes et al. 2005; Taniuchi et al. 2005). The p120-catenin binding juxtamembrane domain (JMD) of P-cadherin could be crucial for the enhancement of invasion and migration caused by P-cadherin overexpression in these cancers (Paredes et al. 2004). The underlying mechanism is unclear, but small sequence differences between the JMDs of E-cadherin and P-cadherin might result in differential binding of interacting proteins and modulation of p120ctn functionality in case of association with P-cadherin (Paredes et al. 2007). In melanoma cell lines P-cadherin can counteract invasion (Van Marck et al. 2005), which appears to agree with the shift in human melanoma from active, membranous to cytoplasmic P-cadherin (Sanders et al. 1999).

VE-CADHERIN (CADHERIN-5) AND OTHER TYPE-II CADHERINS

The endothelial specific expression of VE-cadherin (cadherin-5) plays a key role in regulating vascular morphology and stability (Fig. 4) (Dejana 2004; reviewed by Cavallaro et al. 2006). Microarray studies revealed that VE-cadherin is overexpressed in aggressive human cutaneous and uveal melanoma cells, but not in nonaggressive or poorly aggressive melanoma (Table 1) (Bittner et al. 2000). On the other hand, formation of patterned networks of matrix-rich tubular structures in three-dimensional culture is characteristic of highly aggressive but not poorly aggressive melanoma cells (Maniotis et al. 1999). This vascular mimicry is clinically significant and increases the risk of metastatic disease (Warso et al. 2001). Aggressive melanoma cells in which VE-cadherin was repressed could not form vasculogenic-like networks (Hendrix et al. 2001), suggesting that tumor-associated misexpression of VE-cadherin (observed in melanoma cells) is instrumental in mimicking endothelial cells to form vasculogenic networks. Recently, VE-cadherin was found to be targeted to proteasome-mediated degradation by a transmembrane ubiquitin ligase of the Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (Mansouri et al. 2008). This resulted in a reduction of the steady-state levels of interacting catenins and in rearrangement of the actin cytoskeleton. This reprogramming and differentiation of endothelial cells accompanies loss of endothelial barrier function and vascular leakage, which could be relevant during Kaposi's sarcoma tumor formation (Mansouri et al. 2008).

Antiangiogenic tumor therapy is lately receiving much attention in the form of anti-VEGF therapy (Loges et al. 2008). Also VE-cadherin has become a target for inhibition of pathological angiogenesis. Monoclonal antibodies directed against VE-cadherin could inhibit angiogenesis and reduce tumor growth of experimental hemangiomas and gliomas (Corada et al. 2002; Cavallaro et al. 2006). Specificity for angiogenic tumor vasculature was further enhanced by targeting a VE-cadherin epitope that is at least partly engaged in trans-dimer formation, and thus is masked on established vessels (May et al. 2005). This therapy is antiangiogenic during neovascularization because de novo adherens junction formation is inhibited. The potential value of anti-VE-cadherin therapy was further shown by using a cyclic peptide directed against VE-cadherin to inhibit oxygen-induced retinal neovascularization (Navaratna et al. 2008). Regarding angiogenesis, it is worth mentioning that endothelial cells also express N-cadherin, R-cadherin (CDH4), and T-cadherin (cadherin-13; see the following discussion). N-cadherin is involved in recruitment (or binding) of pericytes, which stabilizes blood vessel formation (Cavallaro et al. 2006). The functions of T-cadherin and R-cadherin in endothelial cells are unclear. In gastrointestinal cancer, the CDH4 promoter is often methylated early in tumor progression, indicating that R-cadherin might be a tumor suppressor (Miotto et al. 2004).

Recently, the cytogenetically normal genome of a typical acute myeloid leukemia sample was fully sequenced and compared with the genome of normal skin cells of the same patient (Ley et al. 2008). Only ten genes with acquired mutations were identified, including a nonsense mutation in the ectodomain of cadherin-24 (CDH24). This type-II cadherin (Fig. 1) (Hulpiau and van Roy 2009) has received little attention. It is widely expressed in human tissues, binds p120 and β-catenin, and can mediate strong cell–cell adhesion (Katafiasz et al. 2003).

CADHERIN-13 (T-CADHERIN)

Cadherin-13 (CDH13), also called T(runcated)- or H(eart)-cadherin, is most peculiar. It is the only known cadherin that is membrane-anchored via a glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) anchor instead of transmembrane domains (Figs. 1 and 4). This explains its unusual location at apical instead of basolateral membranes in polarized epithelial cells (Ranscht and Dours-Zimmermann 1991). Nevertheless, the extracellular domain of CDH13 shows significant homology with the ectodomain of classical cadherins (Hulpiau and van Roy 2009), and its binding is indeed homophilic though relatively weak because of structural peculiarities (Vestal and Ranscht 1992; Dames et al. 2008). This binding weakness suggests that CDH13 functions mainly in signaling.

The human CDH13 gene is located on chromosome 16q24, and because it is frequently silenced in many different cancers, it has long been considered to be a tumor suppressor (Table 1) (Lee 1996; reviewed by Takeuchi and Ohtsuki 2001). Also, CDH13 LOH is frequently observed in major cancer types. In several of these studies, treatment of tumor cell lines with a demethylating agent or a histone deacetylase inhibitor reactivated CDH13 expression. Methylation of the CDH13 promoter was associated with recurrence of nonsmall-cell lung cancers after surgery (Brock et al. 2008). A genome-wide study of association of single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) with prostate cancer revealed four candidate susceptibility genes, including CDH13 (Thomas et al. 2008). Cdh13 expression was up-regulated in castrated mice but was down-regulated following androgen replacement, which is in line with androgen-responsive elements in its promoter region (Wang et al. 2007). Exogenous expression of CDH13 in DU145, a cell line derived from a prostate cancer metastasis, reduced tumorigenicity, whereas knockdown of CDH13 transcripts in BPH1, derived from benign prostate hyperplasia, facilitated tumorigenesis (Wang et al. 2007).

Other experiments point to several growth inhibitory effects of CDH13 (Lee 1996; Huang et al. 2003; Mukoyama et al. 2005; Yan et al. 2008), but the underlying mechanism is unclear. Overexpression of CDH13 in carcinoma or glioma cells causes G2/M cell cycle arrest (Huang et al. 2003). In the glioma study, arrest depended on expression of the CDK inhibitor p21CIP1 but not on expression of p53. Another study reported that CDH13 interferes with c-Jun oncogenic activity (Chan et al. 2008). Moreover, in vitro invasiveness of breast cancer cells was inhibited by exogenous expression of CDH13 (Lee et al. 1998). However, exceptions do occur: One highly invasive hepatoma cell line autonomously produces high levels of CDH13, and knockdown of this expression reduced invasion and migration activity (Riou et al. 2006).

The recently reported Cdh13 knockout mouse did not show spontaneous tumors or other overt phenotypic abnormality, but crossing it with the MMTV-polyomavirus-middle-T (MMTV-PyV-MT) transgenic mouse resulted in offspring with CDH13-deficient mammary tumors that were growth restricted and less vascularized (Hebbard et al. 2008). Nevertheless, these CDH3-deficient tumors had greater metastatic potential than wild-type MMTV-PyV-MT tumors, which might be explained by hypoxia-driven EMT (see also previous discussion). The discrepancy of these in vivo findings with the proposed tumor suppressor function of CDH13 could be partly because of the contribution of tumor vasculature.

Indeed, CDH13 was found to be induced in microvessels associated with tumors and metastases, whereas in normal tissues it was expressed only in larger vessels (Wyder et al. 2000). In hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), CDH13 is silenced in the cancer cells but overexpressed in the intratumoral endothelial cells (Adachi et al. 2006; Riou et al. 2006; Chan et al. 2008). In a two-chamber system, angiogenic factor FGF-2 derived from HCC cells induced CDH13 expression in sinusoidal endothelial cells (Adachi et al. 2006). Overexpression of CDH13 in a human microvascular endothelial cell line stimulated invasion of these nontumoral cells into multicellular spheroids of undifferentiated melanoma cells lacking CDH13 expression (Ghosh et al. 2007). Overexpression and homophilic ligation of CDH13 in endothelial cells stimulates their proliferation and migration, enhances their protection against oxidative stress, and stimulates angiogenesis under pathological conditions, apparently by potentiating factors such as VEGF (Philippova et al. 2006). Growth of CDH13-expressing MMTV-PyV-MT tumors transplanted in mammary fat pads of Cdh13-null recipient mice was slower than in wild-type mice, consolidating the nonautonomous effect of CDH13 on tumor growth (Hebbard et al. 2008).

How does CDH13 act as a stromal factor favoring tumor growth whereas the tumor cells themselves tend to silence its expression? On homophilic ligation of CDH13 on surfaces of endothelial cells it becomes linked to different interacting proteins, including Grp78/BiP (Philippova et al. 2008). The latter is normally retained within the ER but becomes surface exposed under pathological conditions. Endothelial cell survival is apparently promoted by surface exposed Grp78 via the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and Akt kinase pathway (Fig. 4). Another interesting CDH13 partner in endothelial cells is αvβ3 integrin. CDH13 colocalizes with this integrin mostly at the leading edge of migrating cells, which agrees with a proangiogenic CDH13 effect (Philippova et al. 2008).

CDH13 was also identified as a “third adiponectin receptor” (reviewed by Takeuchi et al. 2007). Adiponectin, secreted by adipocytes, is a hormone with insulin-sensitizing effects. In serum it exists as trimers, hexamers, or high molecular weight oligomers. CDH13 probably serves as coreceptor with the more classic adiponectin-receptor-1 and -2 for binding hexameric and larger adiponectin forms (Hug et al. 2004). The possible relevance of this coreceptor function of CDH13 to cancer is supported by evidence from the MMTV-PyV-MT mammary tumor system (Hebbard et al. 2008). When Cdh13 was ablated, adiponectin was no longer associated with the tumor vasculature and its serum levels increased. As adiponectin can sequester various growth factors, its CDH13-dependent accumulation in a tumoral microenvironment may favor both tumor-associated neoangiogenesis and tumor growth.

PROTOCADHERINS AND CANCER

As recently reviewed (Hulpiau and van Roy 2009), protocadherins differ in many aspects from classic cadherins (Figs. 1 and 3). They can be subdivided into clustered and nonclustered protocadherins, reflecting the localization of their genes in vertebrate genomes. Transcripts of clustered protocadherins are composed of one of many variable exons combined with a few constant exons. Three subfamilies of clustered protocadherins are discerned in mammals: α-, β-, and γ-protocadherins. Evidence for the involvement of clustered protocadherins in cancer is limited. In a global genomic analysis of pancreatic cancers, more than 23,000 pancreatic cancer-derived transcripts were sequenced (Jones et al. 2008) (Table 1). This revealed cancer-associated somatic missense mutations in some members of the clustered protocadherin subfamilies, but their functional relevance remains unclear. Other studies pointed at the involvement of methylation of the PCDHGA11 or PCDHGB6 promoter region in the development of astrocytomas or breast cancer (Miyamoto et al. 2005; Waha et al. 2005).

Considerably more information is available about the nonclustered protocadherins, a family comprising 10 members in man and other mammals (Hulpiau and van Roy 2009). In the same large-scale analysis of pancreatic cancers (Jones et al. 2008), missense mutations were found in protocadherin-9, -17, and -18. Expression of protocadherin-1 (PCDH1) in medulloblastoma patients predicted survival (Table 1) (Neben et al. 2004).

In breast cancer, protocadherin-8 (PCDH8) was proposed as a candidate tumor suppressor (Table 1) (Yu et al. 2008), as several somatic missense mutations affecting the ectodomain or a conserved motif in the cytoplasmic domain were found in tumor samples and cell lines (Yu et al. 2008). Proliferation and migration of breast cancer cell lines was inhibited by forced expression of wild type PCDH8 but not by two of the ectodomain missense mutations. Moreover, the E146K mutation, assumed to affect a calcium-coordinating amino acid in PCDH8, conferred a transformed phenotype on “normal” MCF10A cells (Yu et al. 2008). Contrary to common descriptions, PCDH8 is not the homolog but the close paralog of the paraxial protocadherin (PAPC) of Xenopus laevis (Hulpiau and van Roy 2009). So one should be careful when interpreting PCDH8 functions based on the numerous reported findings on Xenopus PAPC (e.g., Unterseher et al. 2004). Interestingly, neural stimulation induces a short isoform of Arcadlin (= rat Pcdh8) in hippocampal synapses, where it associates with N-cadherin and cadherin-11 (Fig. 4) (Yasuda et al. 2007). Induction of this isoform activated a MAPKKK, TAO2β, triggering a signaling pathway leading to endocytosis of N-cadherin. Whether the putative tumor suppressor activity of PCDH8 is based on a similar phenomenon is unknown.

Within the same protocadherin subfamily, protocadherin-10 (PCDH10 or OL-protocadherin) and protocadherin-20 (PCDH20) were also proposed as tumor suppressors (Table 1). First, strong evidence was reported for frequent epigenetic inactivation of PCDH10 in various human cancers but not in matched normal tissues (Miyamoto et al. 2005; Ying et al. 2006; Ying et al. 2007; Yu et al. 2009). For gastric cancer, PCDH10 methylation was detected at early stages of carcinogenesis and was associated with poor prognosis (Yu et al. 2009). Ectopic PCDH10 expression in nasopharyngeal and esophageal carcinoma cell lines reduced clonogenicity, anchorage-independent growth, migration potential, and in vitro invasion into Matrigel (Ying et al. 2006). Re-expression of PCDH10 in gastric cancer cells inhibited tumor growth in mice, induced cell apoptosis, and inhibited cell invasion (Yu et al. 2009). Also, the promoter of the PCDH20 gene is frequently methylated in human tumors, specifically in nonsmall-cell lung cancers (Imoto et al. 2006). Again, ectopic expression in a carcinoma cell line reduced clonogenicity and anchorage-independent growth. The molecular mechanisms underlying these tumor suppressive functions of protocadherins are unknown.

In contrast to the previously mentioned protocadherins, protocadherin-11Y (PCDH11Y, also named protocadherin-PC) is a candidate proto-oncogene. Human PCDH11X and PCDH11Y are highly homologous and are located in the hominid-specific nonpseudoautosomal homologous region Xq21.3/Yp11.2, which had undergone duplication by transposition from the X to the Y chromosome after the divergence of the hominid and chimpanzee lineages. In other words, PCDH11Y is found exclusively in man (Blanco et al. 2000). Transcription occurs mainly in the brain. The encoded PCDH11 proteins belong to the δ1-protocadherin subfamily (Vanhalst et al. 2005).

The start codon in the PCDH11X transcript is absent from the PCDH11Y transcript because of a short genomic deletion. Use of an AUG further downstream results in a PCDH11Y protein lacking the signal peptide and therefore remaining cytoplasmic (Fig. 4) (Chen et al. 2002). Transcription of PCDH11Y is up-regulated in apoptosis-resistant cell variants compared with the parental prostate carcinoma cell line LNCaP. PCDH11Y mRNA levels are increased in androgen-refractory prostate cancers, and its ectopic expression in human prostate cancer cell lines induced anchorage-independent growth in hormone-deprived medium and tumorigenicity in castrated nude mice (Terry et al. 2006). Its expression correlated with occurrence of nuclear β-catenin and with increased TCF/Lef transcriptional activity (Yang et al. 2005; Terry et al. 2006). Recently, an interesting link was established between Wnt/β-catenin signaling and androgen independence during prostate cancer progression (Placencio et al. 2008; Schweizer et al. 2008; Wang et al. 2008). Although β-catenin coimmunoprecipitated with PCDH11Y (Chen et al. 2002), the interaction between the two proteins is not direct (our unpublished data).

OTHER CADHERIN-RELATED MOLECULES AND CANCER

Expression of the mRNA and protein of a cadherin-related protein, named protocadherin LKC or PC-LKC and later renamed protocadherin-24 (Fig. 1), was reported to be reduced in carcinomas derived from the colon, liver, and kidney (Table 1) (Okazaki et al. 2002). Ectopic expression of this cadherin-related protein in human colorectal carcinoma cells (HCT116) reduced tumorigenicity in nude mice by an unknown mechanism.

Another interesting cadherin-related protein is Fat4, which has 34 cadherin repeats and is the homologue of Drosophila Fat (Fig. 1) (Hulpiau and van Roy 2009). In the fly, Fat modulates cell contact inhibition and organ size by functioning upstream of the (Hippo/Salvador)-(Warts/Mats)-Yorkie-Scalloped signaling pathway (reviewed in Harvey and Tapon 2007; Zeng and Hong 2008; Zhao et al. 2008). Several components of this pathway are protein kinases or adaptors, whereas Yorkie is a transcriptional coactivator that is inactivated by cytoplasmic retention on Hippo activation, and Scalloped belongs to the TEAD transcription factor family. Fat appears to be upstream in this pathway and to signal through Expanded, a Merlin-like protein, or through inhibition of Dachs (not to be confused with Dachsous or Ds), an atypical myosin that inhibits Warts. The mechanism by which Expanded activates the Hippo/Salvador complex is unknown. Anyhow, removal of Fat induces overgrowth of imaginal disc tissues. Also, Fat functions in planar cell polarity processes. There is no evidence for homophilic binding in trans between cells expressing Fat (Matakatsu and Blair 2006). In contrast, the ectodomain of Fat can interact with the ectodomain of another huge cadherin-related protein, Dachsous (Ds), on juxtaposed cell surfaces (Figs. 1 and 4). The Fat-Ds interaction can be compared with ligand-receptor binding rather than to cell–cell adhesion, and it might function mainly to activate the intracellular domain of Fat. The intracellular domain of Ds seems to contribute to growth control also independently of the Fat intracellular domain (Matakatsu and Blair 2006).

Each of the Hippo pathway components mentioned above is conserved in mammals, in which the pathway can be abbreviated as (Mst1/Mst2)-(LATS/Mob/WW45)-(YAP/TAZ)-TEAD (Fig. 4). Several of these proteins or their corresponding genes are mutated, silenced, or overexpressed in human tumors and mouse cancer models (reviewed in Harvey and Tapon 2007). A putative role for mammalian Fat4 as tumor suppressor remained unproven until recently, when Qi et al. (2009) reported that biallelic Fat4 inactivation conferred tumorigenicity to a mouse mammary epithelial cell line (Table 1). Re-expression of Fat4 in Fat4-deficient tumor cells suppressed their tumorigenicity. Moreover, Fat4 expression was lost in many human breast tumor cell lines and primary tumors, and this silencing was associated with human Fat4 promoter methylation. Nonetheless, loss of Fat4 by itself is insufficient to generate tumors, as Fat4 knockout mice show various defects, explainable by defective planar cell polarity signaling, but no tumors (Saburi et al. 2008). No association with cancer has been reported for mammalian Dachsous homologs.

The human RET protein is a proto-oncogenic receptor tyrosine kinase with cadherin-like domains in the ectodomain. Bioinformatic analysis and molecular modeling revealed the presence of 4 cadherin-like domains in vertebrate Ret proteins (Fig. 1) (Anders et al. 2001). It was suggested that Ret resulted from recombination of a tyrosine kinase receptor gene and an ancestral cadherin gene during early metazoan evolution. Whether RET can be considered a cell adhesion receptor is undetermined, but its involvement in cancer is beyond doubt (reviewed by Kondo et al. 2006; Zbuk and Eng 2007). Glial cell derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) ligands and GNDF receptor-α bind the extracellular domain of RET, leading to RET dimerization and autophosphorylation. Constitutive activation can result from missense mutations in Cys residues in the ectodomain or from fusion to PTC in a chimeric oncoprotein. The resulting cancers are various sporadic thyroid carcinomas as well as familial cancers such as the multiple endocrine neoplasias MEN2A and MEN2B (Table 1). The role of the cadherin domains in the RET ectodomain is unknown.

CONCLUSIONS AND PERSPECTIVES

The effectiveness of conventional anticancer treatment is often limited by serious toxicity. Even after 30 years of conventional therapies (surgery, irradiation, chemotherapy, and combinations thereof), overall survival from metastatic cancer has not improved much. Among the causes of therapeutic failure are the lack of adequate tumor specificity and the development of drug resistance. Future anticancer drugs should be made more effective and more selective: They should act on or somehow exploit the specific molecular abnormalities driving malignant progression.

Research during the past 20 years has shown that dysregulation of cadherins contributes to different aspects of cancer progression, including drug resistance, angiogenesis, cancer cell invasion, and metastasis. Thus, cadherins and their regulators can become valuable diagnostic and prognostic indicators, as well as potential therapeutic targets.

The most compelling data for the involvement of the cadherin family in cancer progression are available for E-cadherin. The causal relationship between E-cadherin dysfunction and cancer progression has been convincingly shown both in vitro and in vivo. Furthermore, the clinical relevance of E-cadherin deficiency has been confirmed by immunohistochemical evidence of changes in E-cadherin expression and localization in most human cancers (reviewed in Strumane et al. 2004). Consequently, circulating cadherin fragments received as much attention as potential cancer markers (reviewed in De Wever et al. 2007). Indeed, multiple cadherins are targets for ectodomain shedding because of elevated protease activity in the tumoral microenvironment. However, current experimental data support the use only of soluble N-cadherin as a circulation tumor marker for prostate and pancreas cancers. Expression of N-cadherin and cadherin-11 might be used as indicators of unfavorable diagnosis or poor prognosis because they are normally not expressed in epithelia but are frequently up-regulated in invading cancer cells. A cyclic pentapeptide, ADH-1, has been developed as an extracellular N-cadherin antagonist for use as a systemic anticancer agent (reviewed by De Wever et al. 2007; Mariotti et al. 2007). ADH-1 has entered clinical testing, and has been reported to have significant antitumor activity in a mouse model for pancreatic cancer (Shintani et al. 2008) and to strongly potentiate chemotherapy of human melanoma xenografts (Augustine et al. 2008).

Various aberrations that negatively affect E-cadherin can occur during cancer progression, such as mutations, promoter methylation, and transcriptional repression. In sporadic diffuse gastric cancer and possibly in HDGC, CDH1 mutations are accompanied by epigenetic silencing of the second allele (Grady et al. 2000). This opens the way for future E-cadherin-directed epigenetic therapy by using DNA methylation inhibitors (e.g., 5AzaC) and histone deacytelase inhibitors (e.g., trichostatin A; Wu et al. 2007), both of which have been shown to reactivate E-cadherin expression in vitro. It is noteworthy that several protocadherins were recently reported to be silenced by promoter methylation in cancers. Nonetheless, one has to consider that reactivating expression of cell–cell adhesion molecules in cancer cells may trigger intrinsic or acquired resistance to anticancer drug-induced apoptosis (St Croix and Kerbel 1997).

Further, transcriptional deregulation of epithelial differentiation has been much explored lately (Peinado et al. 2007). As pointed out previously, different transcriptional repressors of E-cadherin have been identified, such as Twist, Snail, and ZEB family members and their respective miRNA regulators. Because of the central role of these transcription factors in EMT and their possible contribution to tumorigenesis, they can be regarded as candidates for molecular targeting (Berx et al. 2007). Specifically inhibiting them by small interfering RNA (siRNA) or by chemical compounds could improve the management of malignant cancer by enhancing E-cadherin expression. Expression of these EMT-driving transcriptional repressors has also been associated with anti-apoptotic functions, poor response to pharmacological treatments, and chemoresistance (Yauch et al. 2005; Shah and Gallick 2007). Identification of an EMT signature in tumors could therefore be instrumental to developing more effective therapeutics. For this, we should carefully investigate the aberrations in signaling pathways driving EMT in different tumor types to enable use of pathway-specific inhibitors as anti-invasive cancer therapies. For instance, TGF-β is a strong inducer of EMT: It stabilizes and induces the expression of different E-cadherin repressors and can enhance the cancer stem cell phenotype (Mani et al. 2008). Long-term use of TGF-β antagonists has been shown to be effective in reducing metastasis in experimental mouse models (Akhurst 2002) and could therefore be a means to block pathological EMT in cancer.

In conclusion, it is most important to investigate further the pleiotropic effects of different cadherins, protocadherins, and other cadherin-related molecules during cancer progression. This implies unraveling complex regulatory pathways, including molecular inducers, signaling pathways, and molecular effectors, under both physiological and pathological conditions. This is well advanced for classic cadherins, but for numerous other members of the cadherin superfamily, it is still in its infancy. Such scrutiny might eventually lead to development of better tailored anticancer therapies based on cadherin-targeting strategies.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was funded by grants from the FWO, the Geconcerteerde Onderzoeksacties of Ghent University, the Belgian Federation against Cancer, the Association for International Cancer Research (Scotland), and FP7 (TUMIC) of the European Union. We acknowledge Dr. Amin Bredan for critical reading of the manuscript, and the members of our research groups for valuable discussions.

Footnotes

Editors: W. James Nelson and Elaine Fuchs

Additional Perspectives on Cell Junctions available at www.cshperspectives.org

REFERENCES

- Adachi Y, Takeuchi T, Sonobe H, Ohtsuki Y 2006. An adiponectin receptor, T-cadherin, was selectively expressed in intratumoral capillary endothelial cells in hepatocellular carcinoma: Possible cross talk between T-cadherin and FGF-2 pathways. Virchows Archiv 448:311–318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akhurst RJ 2002. TGF-β antagonists: Why suppress a tumor suppressor? J Clin Invest 109:1533–1536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Hajj M, Wicha MS, Benito-Hernandez A, Morrison SJ, Clarke MF 2003. Prospective identification of tumorigenic breast cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100:3983–3988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alpaugh ML, Tomlinson JS, Shao ZM, Barsky SH 1999. A novel human xenograft model of inflammatory breast cancer. Cancer Res 59:5079–5084 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anders J, Kjaer S, Ibanez CF 2001. Molecular modeling of the extracellular domain of the RET receptor tyrosine kinase reveals multiple cadherin-like domains and a calcium-binding site. J Biol Chem 276:35808–35817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Augustine CK, Yoshimoto Y, Gupta M, Zipfel PA, Selim MA, Febbo P, Pendergast AM, Peters WP, Tyler DS 2008. Targeting N-cadherin enhances antitumor activity of cytotoxic therapies in melanoma treatment. Cancer Res 68:3777–3784 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker K-F, Atkinson MJ, Reich U, Huang H-H, Nekarda H, Siewert JR, Höfler H 1993. Exon skipping in the E-cadherin gene transcript in metastatic human gastric carcinomas. Hum Mol Genet 2:803–804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker KF, Atkinson MJ, Reich U, Becker I, Nekarda H, Siewert JR, Höfler H 1994. E-cadherin gene mutations provide clues to diffuse type gastric carcinomas. Cancer Res 54:3845–3852 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berx G, Cleton-Jansen A-M, Nollet F, de Leeuw WJF, van de Vijver MJ, Cornelisse C, van Roy F 1995a. E-cadherin is a tumor/invasion suppressor gene mutated in human lobular breast cancers. EMBO J 14:6107–6115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berx G, Staes K, van Hengel J, Molemans F, Bussemakers MJG, van Bokhoven A, van Roy F 1995b. Cloning and characterization of the human invasion suppressor gene E-cadherin (CDH1). Genomics 26:281–289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berx G, Cleton-Jansen A-M, Strumane K, de Leeuw WJF, Nollet F, van Roy FM, Cornelisse C 1996. E-cadherin is inactivated in a majority of invasive human lobular breast cancers by truncation mutations throughout its extracellular domain. Oncogene 13:1919–1925 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berx G, Becker K-F, Höfler H, van Roy F 1998. Mutation Update: Mutations of the human E-cadherin (CDH1) gene. Hum Mutat 12:226–237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berx G, Raspe E, Christofori G, Thiery JP, Sleeman JP 2007. Pre-EMTing metastasis? Recapitulation of morphogenetic processes in cancer. Clin Exp Metastas 24:587–597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birchmeier W, Behrens J 1994. Cadherin expression in carcinomas: Role in the formation of cell junctions and the prevention of invasiveness. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer 1198:11–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bittner M, Meitzer P, Chen Y, Jiang Y, Seftor E, Hendrix M, Radmacher M, Simon R, Yakhini Z, BenDor A, et al. 2000. Molecular classification of cutaneous malignant melanoma by gene expression profiling. Nature 406:536–540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco P, Sargent CA, Boucher CA, Mitchell M, Affara NA 2000. Conservation of PCDHX in mammals; expression of human X/Y genes predominantly in brain. Mamm Genome 11:906–914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco MJ, Moreno-Bueno G, Sarrio D, Locascio A, Cano A, Palacios J, Nieto MA 2002. Correlation of Snail expression with histological grade and lymph node status in breast carcinomas. Oncogene 21:3241–3246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnomet A, Nawrocki-Raby B, Strumane K, Gilles C, Kiletzky C, Berx G, van Roy F, Polette M, Birembaut P 2008. The E-cadherin-repressed hNanos1 gene induces tumor cell invasion by upregulating MT1-MMP expression. Oncogene 27:3692–3699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boussadia O, Kutsch S, Hierholzer A, Delmas V, Kemler R 2002. E-cadherin is a survival factor for the lactating mouse mammary gland. Mech Develop 115:53–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bracken CP, Gregory PA, Kolesnikoff N, Bert AG, Wang J, Shannon MF, Goodall GJ 2008. A double-negative feedback loop between ZEB1-SIP1 and the microRNA-200 family regulates epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Cancer Res 68:7846–7854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brock MV, Hooker CM, Ota-Machida E, Han Y, Guo MZ, Ames S, Glockner S, Piantadosi S, Gabrielson E, Pridham G, et al. 2008. DNA methylation markers and early recurrence in stage I lung cancer. New Engl J Med 358:1118–1128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks-Wilson AR, Kaurah P, Suriano G, Leach S, Senz J, Grehan N, Butterfield YSN, Jeyes J, Schinas J, Bacani J, et al. 2004. Germline E-cadherin mutations in hereditary diffuse gastric cancer: Assessment of 42 new families and review of genetic screening criteria. J Med Genet 41:508–517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burk U, Schubert J, Wellner U, Schmalhofer O, Vincan E, Spaderna S, Brabletz T 2008. A reciprocal repression between ZEB1 and members of the miR-200 family promotes EMT and invasion in cancer cells. EMBO Rep 9:582–589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bussemakers MJG, Van Bokhoven A, Tomita K, Jansen CFJ, Schalken JA 2000. Complex cadherin expression in human prostate cancer cells. Int J Cancer 85:446–450 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldas C, Carneiro F, Lynch HT, Yokota J, Wiesner GL, Powell SM, Lewis FR, Huntsman DG, Pharoah PDP, Jankowski JA, et al. 1999. Familial gastric cancer: overview and guidelines for management. J Med Genet 36:873–880 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldas C, Carneiro F, Lynch HT, Yokota J, Wiesner GL, Powell SM, Lewis FR, Huntsman DG, Pharoah PDP, Jankowski JA, et al. 2000. The transcription factor Snail controls epithelial-mesenchymal transitions by repressing E-cadherin expression. Nat Cell Biol 2:76–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cano A, Perez-Moreno MA, Rodrigo I, Locascio A, Blanco MJ, del Barrio MG, Portillo F, Nieto MA 2000. The transcription factor Snail controls epithelial-mesenchymal transitions by repressing E-cadherin expression. Nat Cell Biol 2:76–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carneiro F, Oliveira C, Suriano G, Seruca R 2008. Molecular pathology of familial gastric cancer, with an emphasis on hereditary diffuse gastric cancer. J Clin Pathol 61:25–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavallaro U, Liebner S, Dejana E 2006. Endothelial cadherins and tumor angiogenesis. Exp Cell Res 312:659–667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan DW, Lee JMF, Chan PCY, Ng IOL 2008. Genetic and epigenetic inactivation of T-cadherin in human hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Int J Cancer 123:1043–1052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang HW, Chow V, Lam KY, Wei WI, Yuen APW 2002. Loss of E-cadherin expression resulting from promoter hypermethylation in oral tongue carcinoma and its prognostic significance. Cancer 94:386–392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen MW, Vacherot F, De La Taille A, Gil-Diez-De-Medina S, Shen R, Friedman RA, Burchardt M, Chopin DK, Buttyan R 2002. The emergence of protocadherin-PC expression during the acquisition of apoptosis-resistance by prostate cancer cells. Oncogene 21:7861–7871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng CW, Wu PE, Yu JC, Huang CS, Yue CT, Wu CW, Shen CY 2001. Mechanisms of inactivation of E-cadherin in breast carcinoma: Modification of the two-hit hypothesis of tumor suppressor gene. Oncogene 20:3814–3823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christoffersen NR, Silahtaroglu A, Orom UA, Kauppinen S, Lund AH 2007. miR-200b mediates post-transcriptional repression of ZFHX1B. RNA 13:1172–1178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christofori G, Semb H 1999. The role of the cell-adhesion molecule E-cadherin as a tumour-suppressor gene. Trends Biochem Sci 24:73–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu K, Cheng CJ, Ye X, Lee YC, Zurita AJ, Chen DT, Yu-Lee LY, Zhang S, Yeh ET, Hu MC, et al. 2008. Cadherin-11 promotes the metastasis of prostate cancer cells to bone. Mol Cancer Res 6:1259–1267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleton-Jansen AM, Callen DF, Seshadri R, Goldup S, McCallum B, Crawford J, Powell JA, Settasatian C, van Beerendonk H, Moerland EW, et al. 2001. Loss of heterozygosity mapping at chromosome arm 16q in 712 breast tumors reveals factors that influence delineation of candidate regions. Cancer Res 61:1171–1177 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corada M, Zanetta L, Orsenigo F, Breviario F, Lampugnani MG, Bernasconi S, Liao F, Hicklin DJ, Bohlen P, Dejana E 2002. A monoclonal antibody to vascular endothehal-cadherin inhibits tumor angiogenesis without side effects on endothelial permeability. Blood 100:905–911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covington MD, Burghardt RC, Parrish AR 2006. Ischemia-induced cleavage of cadherins in NRK cells requires MT1-MMP (MMP-14). Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 290:F43-F51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dames SA, Bang E, Haussinger D, Ahrens T, Engel J, Grzesiek S 2008. Insights into the low adhesive capacity of human T-cadherin from the NMR structure of Its N-terminal extracellular domain. J Biol Chem 283:23485–23495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies G, Jiang WG, Mason MD 2001. Matrilysin mediates extracellular cleavage of E-cadherin from prostate cancer cells: A key mechanism in hepatocyte growth factor/scatter factor-induced cell-cell dissociation and in vitro invasion. Clin Cancer Res 7:3289–3297 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Wever O, Derycke L, Hendrix A, De Meerleer G, Godeau F, Depypere H, Bracke M 2007. Soluble cadherins as cancer biomarkers. Clin Exp Metastas 24:685–697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dejana E 2004. Endothelial cell-cell junctions: Happy together. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 5:261–270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derksen PWB, Liu XL, Saridin F, vanderGulden H, Zevenhoven J, Evers B, vanBeijnum JR, Griffioen AW, Vink J, Krimpenfort P, et al. 2006. Somatic inactivation of E-cadherin and p53 in mice leads to metastatic lobular mammary carcinoma through induction of anoikis resistance and angiogenesis. Cancer Cell 10:437–449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Droufakou S, Deshmane V, Roylance R, Hanby A, Tomlinson I, Hart IR 2001. Multiple ways of silencing E-cadherin gene expression in lobular carcinoma of the breast. Int J Cancer 92:404–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunbier A, Guilford P 2001. Hereditary diffuse gastric cancer. Adv Cancer Res 83:55–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eger A, Aigner K, Sonderegger S, Dampier B, Oehler S, Schreiber M, Berx G, Cano A, Beug H, Foisner R 2005. DeltaEF1 is a transcriptional repressor of E-cadherin and regulates epithelial plasticity in breast cancer cells. Oncogene 24:2375–2385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elloul S, Elstrand MB, Nesland JM, Trope CG, Kvalheim G, Goldberg I, Reich R, Davidson B 2005. Snail, Slug, and Smad-interacting protein 1 as novel parameters of disease aggressiveness in metastatic ovarian and breast carcinoma. Cancer 103:1631–1643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endo K, Ashida K, Miyake N, Terada T 2001. E-cadherin gene mutations in human intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. J Pathol 193:310–317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esteban MA, Tran MG, Harten SK, Hill P, Castellanos MC, Chandra A, Raval R, O'Brien T, Maxwell PH 2006. Regulation of E-cadherin expression by VHL and hypoxia-inducible factor. Cancer Res 66:3567–3575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans AJ, Russell RC, Roche O, Burry TN, Fish JE, Chow VWK, Kim WY, Saravanan A, Maynard MA, Gervais ML, et al. 2007. VHL promotes E2 box-dependent E-cadherin transcription by HIF-mediated regulation of SIP1 and snail. Mol Cell Biol 27:157–169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frixen UH, Behrens J, Sachs M, Eberle G, Voss B, Warda A, Löchner D, Birchmeier W 1991. E-cadherin-mediated cell-cell adhesion prevents invasiveness of human carcinoma cells. J Cell Biol 113:173–185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita Y, Krause G, Scheffner M, Zechner D, Leddy HEM, Behrens J, Sommer T, Birchmeier W 2002. Hakai, a c-Cbl-like protein, ubiquitinates and induces endocytosis of the E-cadherin complex. Nat Cell Biol 4:222–231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh S, Josh MB, Ivanov D, Feder-Mengus C, Spagnoli GC, Martin I, Erne P, Resink TJ 2007. Use of multicellular tumor spheroids to dissect endothelial cell-tumor cell interactions: A role for T-cadherin in tumor angiogenesis. FEBS Lett 581:4523–4528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gocheva V, Zeng W, Ke DX, Klimstra D, Reinheckel T, Peters C, Hanahan D, Joyce JA 2006. Distinct roles for cysteine cathepsin genes in multistage tumorigenesis. Genes Dev 20:543–556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grady WM, Willis J, Guilford PJ, Dunbier AK, Toro TT, Lynch H, Wiesner G, Ferguson K, Eng C, Park JG, et al. 2000. Methylation of the CDH1 promoter as the second genetic hit in hereditary diffuse gastric cancer. Nat Genet 26:16–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graff JR, Greenberg VE, Herman JG, Westra WH, Boghaert ER, Ain KB, Saji M, Zeiger MA, Zimmer SG, Baylin SB 1998. Distinct patterns of E-cadherin CpG island methylation in papillary, follicular, Hurthle's cell, and poorly differentiated human thyroid carcinoma. Cancer Res 58:2063–2066 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graff JR, Herman JG, Lapidus RG, Chopra H, Xu R, Jarrard DF, Isaacs WB, Pitha PM, Davidson NE, Baylin SB 1995. E-cadherin expression is silenced by DNA hypermethylation in human breast and prostate carcinomas. Cancer Res 55:5195–5199 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graff JR, Gabrielson E, Fujii H, Baylin SB, Herman JG 2000. Methylation patterns of the E-cadherin 5′CpG island are unstable and reflect the dynamic, heterogeneous loss of E-cadherin expression during metastatic progression. J Biol Chem 275:2727–2732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory PA, Bert AG, Paterson EL, Barry SC, Tsykin A, Farshid G, Vadas MA, Khew-Goodall Y, Goodall GJ 2008. The miR-200 family and miR-205 regulate epithelial to mesenchymal transition by targeting ZEB1 and SIP1. Nat Cell Biol 10:593–601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guaita S, Puig I, Franci C, Garrido M, Dominguez D, Batlle E, Sancho E, Dedhar S, De Herreros AG, Baulida J 2002. Snail induction of epithelial to mesenchymal transition in tumor cells is accompanied by MUC1 repression and ZEB1 expression. J Biol Chem 277:39209–39216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guilford P, Hopkins J, Harraway J, McLeod M, McLeod N, Harawira P, Taite H, Scoular R, Miller A, Reeve AE 1998. E-cadherin germline mutations in familial gastric cancer. Nature 392:402–405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey K, Tapon N 2007. The Salvador-Warts-Hippo pathway - an emerging tumour-suppressor network. Nat Rev Cancer 7:182–191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazan RB, Kang L, Whooley BP, Borgen PI 1997. N-cadherin promotes adhesion between invasive breast cancer cells and the stroma. Cell Adhes Commun 4:399–411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]