Abstract

Background

In schizophrenia, working memory dysfunction is associated with altered expression of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA)A receptor α1 and α2 subunits in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC). In rodents, cortical α subunit expression shifts from low α1 and high α2 to high α1 and low α2 during early postnatal development. Because these two α subunits confer different functional properties to the GABAA receptors containing them, we determined whether this shift in α1 and α2 subunit expression continues through adolescence in the primate DLPFC, potentially contributing to the maturation of working memory during this developmental period.

Methods

Levels of GABAA receptor α1 and α2 subunit mRNAs were determined in the DLPFC of monkeys aged 1 week, 4 weeks, 3 months, 15–17 months (prepubertal), and 43–47 months (postpubertal) and in adult monkeys using in situ hybridization, followed by the quantification of α1 subunit protein by western blotting. We also performed whole-cell patch clamp recording of miniature inhibitory postsynaptic potentials (mIPSPs) in DLPFC slices prepared from pre- and postpubertal monkeys.

Results

The mRNA and protein levels of α1 and α2 subunits progressively increased and decreased, respectively, throughout postnatal development including adolescence. Furthermore, as predicted by the different functional properties of α1-containing versus α2-containing GABAA receptors, the mIPSP duration was significantly shorter in postpubertal than in prepubertal animals.

Conclusions

In contrast to rodents, the developmental shift in GABAA receptor α subunit expression continues through adolescence in primate DLPFC, inducing a marked change in the kinetics of GABA neurotransmission. Disturbances in this shift might underlie impaired working memory in schizophrenia.

Keywords: Adolescence, in situ hybridization, mIPSP, schizophrenia, western blot, working memory

The core features of schizophrenia include impairments in critical cognitive functions, such as working memory, that are dependent on the circuitry of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) (1,2). These cognitive abnormalities are found throughout the life span of affected individuals, including childhood and adolescence and at the initial onset of psychosis (3–6), which typically occurs during late adolescence or early adulthood (7). In primates, working memory performance progressively improves through adolescence (8,9), and this improvement is associated with increased involvement of DLPFC circuitry (10–12). Therefore, the working memory impairments in schizophrenia might reflect disturbances in the normal development of DLPFC circuitry (13,14).

In the DLPFC of subjects with schizophrenia, postmortem studies have consistently revealed alterations in markers of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) neurotransmission (15), such as lower levels of the mRNA encoding the 67-kDa isoform of glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD67), the enzyme principally responsible for GABA synthesis (16–21). Furthermore, these alterations are accompanied by abnormal expression of GABAA receptor α subunits. GABAA receptors are pentameric proteins that form a GABA-gated chloride channel with a typical 2α:2β:γ subunit stoichiometry. In the adult rodent brain, the most abundant subunit combinations, α1β2γ2 and α2β3γ2, constitute approximately 60% and 20% of GABAA receptors, respectively (22). In the DLPFC of subjects with schizophrenia, the levels of GABAAα1 mRNA were reported to be decreased (20), whereas immunoreactivity for the GABAA α2 subunit was increased (23).

In rodents, the expression of these two GABAAα subunits in the neocortex changes in opposite directions during early postnatal development: α1 subunit levels are low at birth and subsequently increase, whereas α2 subunit levels are high at birth and then decline (24). GABAA receptors containing α1 subunits have faster deactivation kinetics than those containing α2 subunits (25), providing a molecular basis for the production of fast versus slow inhibitory postsynaptic currents, respectively. Consistent with these findings, GABA neurotransmission kinetics becomes faster during early postnatal development in rodents, reaching adult values by postnatal Day 21, well before adolescence starts (26). Given that DLPFC GABA neurotransmission is essential for normal working memory function in adult monkeys (27,28), a developmental shift in α subunit expression might also play an important role in the protracted maturation of working memory performance in primates (8,9,11,12), and disturbances in this process might contribute to working memory impairments in schizophrenia. However, in the primate DLPFC, it is unknown whether the developmental shift in α subunit expression occurs early in development as in rodents or over a protracted time course that extends through adolescence.

To distinguish between these two possibilities, we quantified mRNA levels for GABAA receptor α1 and α2 subunits in the DLPFC of rhesus monkeys across six stages of postnatal development: 1 week, 1 month, 3 months, 15–17 months (prepuberty), 43–47 months (post-puberty), and adulthood. To determine the functional significance of these changes in transcript levels, we also evaluated the developmental changes in α1 subunit protein levels and the kinetics of GABAA receptor-mediated inhibitory postsynaptic potentials. Our findings indicate that the developmental changes in the expression of these two GABAA receptor subunits continues through adolescence in primates and therefore could contribute to the refinements in DLPFC circuitry required for the maturation of working memory performance.

Methods and Materials

Animals

We used 33 rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) that were categorized into six age groups ranging from 1-week-old to adulthood (Table 1). All animals used in this study were female except for subject 282. The housing of animals has been described previously (29). Housing and experimental procedures were conducted in accordance with guidelines set by the U.S. Department of Agriculture and the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and with approval of the University of Pittsburgh's Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. All animals were euthanized with an overdose of pentobarbital.

Table 1.

Monkeys Used in This Study

| Age Group | Monkey No. | Age (month) | Weight (kg) | Perfusiona | Prior Biopsyb | Menstrual Phase | Analysesd | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mRNA | Protein | Electrophysiology | |||||||

| 1W | 193 | .2 | NA | ● | ● | ||||

| 194 | .2 | NA | ● | ● | |||||

| 199 | .2 | .5 | ● | ● | |||||

| 201 | .2 | .4 | ● | ● | |||||

| 4W | 196 | 1 | NA | ||||||

| 197 | 1 | NA | ● | ||||||

| 200 | 1 | .6 | ● | ||||||

| 209 | 1 | .6 | ● | ||||||

| 12W | 192 | 3 | .8 | ● | |||||

| 198 | 3 | .8 | ● | ||||||

| 203 | 3 | .9 | ● | ||||||

| 212 | 3 | 1.1 | ● | ||||||

| 230 | 3 | 1.1 | ○ | ● | |||||

| 234 | 3 | .9 | ○ | ● | |||||

| 241 | 3 | 1.0 | ○ | ● | |||||

| 245 | 3 | 1.2 | ○ | ● | |||||

| Pre-Puberty | 240 | 16 | 2.3 | ○ | ● | ● | |||

| 255 | 17 | 2.6 | ○ | ● | ● | ||||

| 264 | 15 | 2.5 | ○ | ● | ● | ● | |||

| 265 | 15 | 2.4 | ○ | ● | ● | ● | |||

| 268 | 17 | 2.5 | ○ | ○ | ● | ||||

| Post-Puberty | 236 | 43 | 6.1 | ○ | ○ | Luteal | ● | ||

| 238 | 44 | 4.5 | ○ | ○ | Follicular | ● | |||

| 239 | 43 | 5.5 | ○ | Luteal | ● | ● | |||

| 246 | 43 | 4.6 | ○ | ○ | Follicular | ● | |||

| 249 | 44 | 6.2 | ○ | Follicular | ● | ||||

| 258 | 47 | 6.3 | ○ | Follicular | ● | ||||

| 267 | 46 | 5.7 | ○ | ○ | ● | ||||

| 269 | 46 | 4 | ○ | ○ | ● | ||||

| Adult | 248 | 93 | 8.8 | ○ | ○ | Luteal | ● | ||

| 259 | 104 | 6.4 | ○ | Luteal | ● | ● | |||

| 260 | 138 | 9.5 | Luteal | ● | ● | ||||

| 282c | 109 | 11.7 | ● | ||||||

W, week.

Open circles indicate monkeys were given an overdose of pentobarbital (30 mg/kg) and perfused transcardially with ice-cold modified artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF).

Open circles indicate monkeys who had a prior biopsy. Two to four weeks before perfusion with ACSF, a small block of tissue containing dorsal area 9 and the medial bank of the principal sulcus was surgically excised from the rostral third of the principal sulcus in the left hemisphere.

Monkey 282 was a male.

Closed circles indicate monkeys used in the indicated type of study.

Analysis of mRNA Levels by In Situ Hybridization

Of the 28 animals used in this analysis (Table 1), 16 were perfused transcardially with ice-cold modified artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) with the following composition (in mmol/L): sucrose 210, NaCl 10.0, KCl 1.9, Na2HPO4 1.2, NaHCO3 33.0, MgCl2 6.0, CaCl2 1.0, glucose 10.0, and kynurenic acid 2.0; pH 7.3–7.4 when bubbled with 95% O2–5%CO2. Four of these animals (Table 1) underwent a biopsy of a nonhomotopic region of the left DLPFC 2 to 4 weeks before perfusion for in vitro slice physiology studies (30). After the brains were removed, the right frontal lobe was blocked coronally, frozen, and stored at −80°C. Serial cryostat sections (16 μm) containing the caudal principal sulcus of the right DLPFC were cut from fresh-frozen coronal tissue blocks and thaw-mounted onto glass slides. From each animal, two sections spaced at 224 μm were processed for both GABAA receptor α1 and α2 subunit mRNAs. In situ hybridization was performed as previously described (19) using 35S-labeled sense and antisense riboprobes (Supplement 1).

Radioactivity of hybridized probes was detected by autoradiographic films and then by nuclear emulsion (Supplement 1). Film optical density of signals was measured within the contours of DLPFC area 46 (Supplement 1) and expressed as nanocuries per gram of tissue by reference to radioactive Carbon-14 standards (ARC, St. Louis, Missouri) exposed on the same film. In the same area, the optical density was also measured in cortical traverses from the pial surface to the white matter to assess the expression levels in each cortical layer (Supplement 1). For this laminar analysis, we used the animals in the 1-week-old, prepuberty, and adult age groups. All cortical optical density measures were corrected by subtracting background optical density measures in the white matter.

To assess the effect of postnatal development on the expression levels of both α1 and α2 subunit mRNAs, an analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed using mean optical density measures as the dependent variable and age group as the main effect. Duncan's post hoc test was used for multiple comparisons between age groups with α = .05.

Assessment of Potential Confounding Factors on mRNA Expression

To assess the potential effects of perfusion with modified ACSF on the measures of mRNA levels, a two-sample t test was performed to compare the optical density measures of GABAA receptor α1 and α2 mRNAs between 3-month-old monkeys with and without modified ACSF perfusion (n = 4 for each group). Similarly, the effect of prior biopsy on mRNA expression was assessed by conducting a two-sample t test comparing the optical density measures between postpubertal and adult monkeys with (n = 4) and without (n = 5) a prior biopsy. To assess the possible effects of sex steroids on the expression of α subunits (31,32), phase of menstrual cycle was determined for the postpubertal and adult animals by measuring serum levels of estradiol and progesterone obtained immediately before euthanasia in 8 of 9 animals. For the remaining adult animal, records of observed menstruation indicated that she had very stable cycles, which predicted that she was in luteal phase at the time of euthanasia. The effect of menstrual status on α1 and α2 mRNA levels was tested by ANOVA with menstrual status as a main effect and age group as a blocking factor.

Analysis of Protein Levels by Western Blot

Twelve animals belonging to three age groups, 1 week, prepubertal, and adult (n = 4 for each) were used in this analysis (Table 1). Because of the limited availability of tissue from one of the adult animals (subject 248), a 43 month-old (postpubertal) monkey (subject 239) was included as an adult animal. Animals were divided into four triads composed of one animal per age group, and each triad was processed on the same gels.

Protein levels of GABAA receptor α1 subunit were measured by Western blot with anti-GABAA receptor α1 subunit and anti-actin antibodies (Supplement 1). The protein content of GABAA receptor α1 subunit was expressed relative to the actin content of the same sample. The specificity of the anti-GABAA receptor α1 subunit antibody was confirmed by immunoblot using brain samples from GABAA receptor α1 subunit knockout mice (kindly provided by Dr. A Leslie Morrow, University of North Carolina) (33); protein levels of the α2 subunit could not be determined because a specific antibody was unavailable. The effect of postnatal development on GABAA receptor α1 subunit expression was assessed by ANOVA with the relative GABAA receptor α1 protein level as a dependent variable, age group as a main effect, and triad as a blocking factor. A Duncan's post hoc test with α = .05 was conducted for multiple comparisons between age groups.

Analysis of Miniature Inhibitory Postsynaptic Potentials in DLPFC Slices

The surgical procedures to obtain tissue blocks for electrophysiologic experiments have been previously described (30). Tissue blocks containing portions of DLPFC areas 46 and 9 from prepubertal (n = 3 animals; three hemispheres) and postpubertal (n = 2 animals; four hemispheres) monkeys (Table 1) were sectioned in the coronal plane to generate 350-μm-thick slices. Using these slices, miniature inhibitory postsynaptic potentials (mIPSPs) were recorded from layer 2/3 pyramidal neurons (n = 11 cells for each of two age groups) by whole-cell current clamp recordings (Supplement 1). For each cell, at least 300 nonoverlapping events were included to generate automatically an average mIPSP for each cell. The amplitude, the 10%–90% rise time and the decay time constant (determined by fitting an exponential function to the 10%–90% decay phase) were determined for the average mIPSP for each cell and compared between the two age groups. Statistical significance was assessed by using Student's t test with α = .05.

Results

Specificity of Riboprobes for GABAA Receptor α1 and α2 Subunit mRNAs

In emulsion-coated slides, the expression of GABAA receptor α1 and α2 subunit mRNAs was detected as accumulations of silver grains around Nissl-stained nuclei (see Figure in Supplement 1), indicating specific hybridization within the cytoplasm for each mRNA. Labeled cells were identified as neurons by the faint Nissl staining of their large nuclei, distinguishing them from unlabeled glial cells with intensely stained, small nuclei. Specificity of the antisense riboprobes was also confirmed by examination of sections treated with sense riboprobes, which did not produce signal above background on film autoradiograms.

Postnatal Changes in GABAA Receptor α1 and α2 Subunit mRNA Expression in Monkey DLPFC

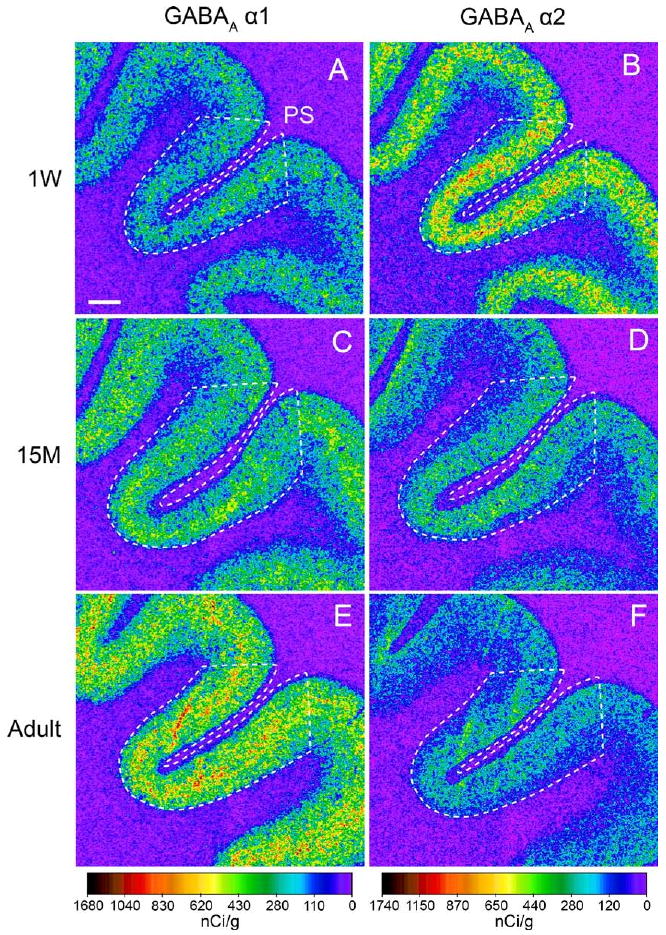

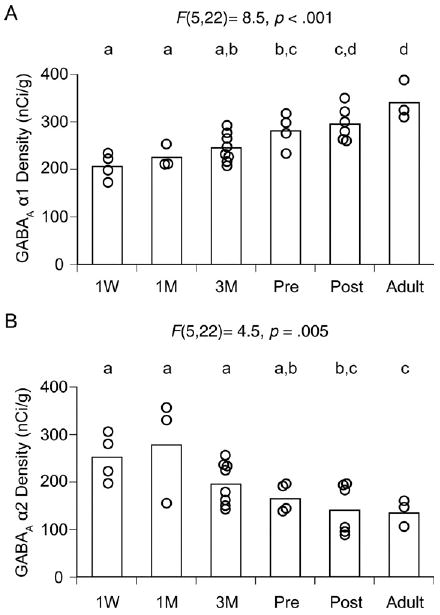

In DLPFC area 46, α1 subunit mRNA expression appeared to increase, whereas α2 subunit mRNA expression appeared to decrease across postnatal development (Figure 1). The ANOVA revealed a significant effect of age on the expression levels of both α1 [F(5,22) = 8.5, p < .001] and α2 [F(5,22) = 4.5, p = .005] subunit mRNAs (Figure 2). Post hoc analyses revealed significant differences (p < .05) in the expression levels of both mRNAs between 1-week-old, prepubertal (15–17 months of age), and adult animals (Figure 2). From 1-week-old to prepubertal animals, mean α1 subunit mRNA levels increased by 36%, whereas α2 subunit mRNA levels decreased by 35%. From prepubertal to adult animals, α1 subunit mRNA levels increased by 21%, whereas α2 subunit mRNA levels decreased by 18%.

Figure 1.

Postnatal development of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA)A receptor subunit mRNA expression in area 46 of monkey dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC). Representative film autoradiograms show changes in GABAA receptor α1 (A, C, E) and α2 (B, D, F) mRNA expression in area 46 from 1-week-old (1W) (A, B), 15-month-old (15M) (C, D), and adult (E, F) monkeys. The signal intensity for α1 mRNA increases, whereas that for α2 mRNA decreases, during postnatal development. The optical densities of hybridization signals are presented in a pseudo-color manner according to the calibration scales at the bottom for each mRNA. The optical density for each mRNA was quantified within areas indicated by broken lines. PS, the principal sulcus. Scale bar = 1 mm (applies to all panels).

Figure 2.

Expression levels of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA)Areceptor α1 and α2 subunit mRNAs in the monkey dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) during development. The optical densities for α1 (A) and α2 (B) subunit mRNAs within area 46 of each animal are individually plotted for each age group. The mean values for each age group are indicated as bars. During postnatal development, α1 mRNA levels increased, whereas α2 mRNA levels declined. Age groups that do not share the same letter are statistically different at alpha = .05. These findings demonstrate that the shift in α subunit expression is a progressive and protracted process that lasts through adolescence. M, months; Pre, prepuberty; Post, postpuberty; W, week.

Laminar Changes in Expression of α1 and α2 Subunit mRNAs

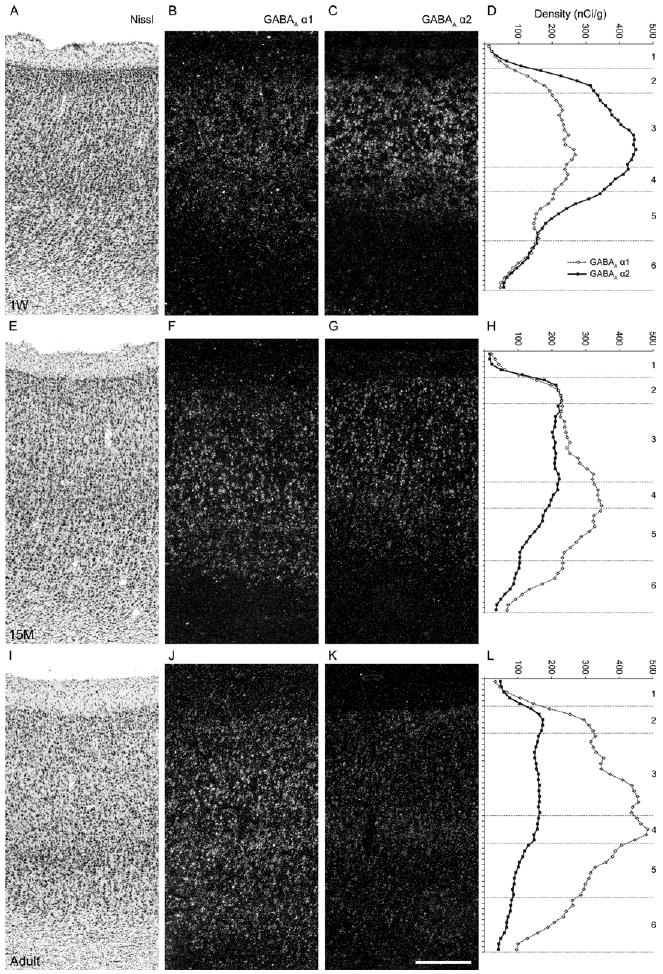

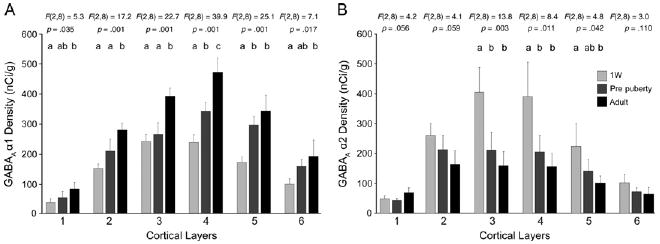

Across cortical layers, the expression patterns of α1 and α2 subunit mRNAs differed among animals of three developmental stages: 1 week, prepuberty, and adulthood (Figure 3). The expression of α1 subunit mRNA significantly increased [for all, F(2,8) > 5.2, p < .036, Figure 4] in all layers with age. In contrast, the expression of α2 mRNA decreased in all layers except for layer 1, and the ANOVA revealed significant effects of age in layers 3, 4, and 5 [for all, F(2,8) > 4.8, p < .043, Figure 4].

Figure 3.

Developmental changes in gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA)Areceptor α1 and α2 subunit mRNA expression across cortical layers. Serial sections from 1-week-old (A, B, C), 15-month-old (E, F, G), and adult (I, J, K) monkeys were Nissl-stained (A, E, I) or hybridized with antisense riboprobes for α1 (B, F, J) or α2 (C, G, K) subunit mRNAs. Panels B, F, J and C, G, K show darkfield photomicrographs of emulsion-dipped sections. The expression patterns of α1 and α2 subunit mRNAs detected by the emulsion autoradiograms matched well with the mean optical density plots from film autoradiograms (D, H, and L) across cortical layers for both subunit mRNAs. Numbers at far right indicate cortical layers. Scale bar = 300 μm (applies to all photomicrograph panels). M, months; W, week.

Figure 4.

Cortical layer comparisons of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA)Areceptor α1 and α2 subunit mRNA expression among 1 week, prepuberty, and adult groups of monkeys. The means (± SD) of GABAA receptor α1 (A), and α2 (B) subunit expression levels in each age group were plotted across cortical layers. For the α1 subunit, layers 2–3 showed a prominent increase during adolescence, whereas layer 5 showed a significant increase in the preadolescent period. For the α2 subunit, the magnitude of changes was greater during the preadolescent period. Age groups that do not share the same letter are statistically different at α = .05. W, week.

Interestingly, the developmental changes in expression were more prominent in certain layers at different ages for each subunit. For the α1 subunit, layer 5 showed a significant increase in the preadolescent period, whereas layers 2 and 3 showed prominent increases between prepuberty and adulthood (Figures 3 and 4), a pattern of change consistent with the general “inside-out” pattern of cortical development. For the α2 subunit, the magnitude of changes was greater during the preadolescent period across cortical layers (Figures 3 and 4).

Effects of Potential Confounding Factors on mRNA Expression

Neither perfusion nor prior biopsy had a significant effect on mRNA levels for α1 (p = .12 for perfusion, p = .23 for prior biopsy) or α2 (p = .55 for perfusion, p = .86 for prior biopsy) subunits. Menstrual status did not have a significant effect on α1 [F(1,6) = 2.2, p = .19] or α2 [F(1,6) = .02, p = .88] subunit mRNA levels in post-adolescent animals.

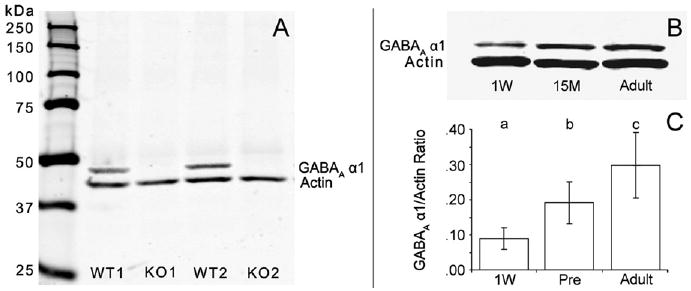

Postnatal Changes in GABAA Receptor α1 Subunit Protein Levels in Monkey DLPFC

In Western blot analyses, the anti-GABAA receptor α1 subunit antibody detected a single band near the predicted molecular weight of 51 kDa for the α1 subunit in protein samples prepared from the cortex of wild type mice; this band was absent in cortical samples from mice with a knockout of the GABAA receptor α1 subunit gene (Figure 5A). GABAA receptor α1 subunit protein levels progressively increased across the three postnatal developmental age groups studied (Figure 5B and 5C) in parallel to, but with a greater magnitude of increase than, α1 subunit mRNA levels. GABAA receptor α1 subunit protein levels increased by 110% from 1-week-old to prepubertal animals and by 60% from prepubertal to adult animals. The ANOVA revealed a significant effect of age [F(1,9) = 18.9, p = .003] on GABAA receptor α1 subunit protein levels, and the post hoc analysis demonstrated that the increases from 1-week-old to prepubertal animals and from prepubertal to adult animals were both significant (p < .05).

Figure 5.

Expression levels of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA)A receptor α1 subunit protein in the monkey dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) during development. (A) Immunoblot shows the specificity of the anti-GABAA receptor α1 subunit antibody by the presence of a single band of the appropriate MW in wildtype (WT) mice and the absence of this band in GABAA receptor α1 knockout (KO) mice. (B) Immunoblot shows both GABAA receptor α1 subunit and actin protein levels for one triad representing three ages: 1 week (1W), 15 months (15M), and adulthood. (C) Bar graph shows the significant [F(1,9) = 18.9, p < .003] effect of age on the mean (± SD) ratio of GABAA receptor α1 protein signal relative to actin signal for the 1 week, prepubertal, and adult age groups. Bars not sharing the same letter are significantly different (p < .05).

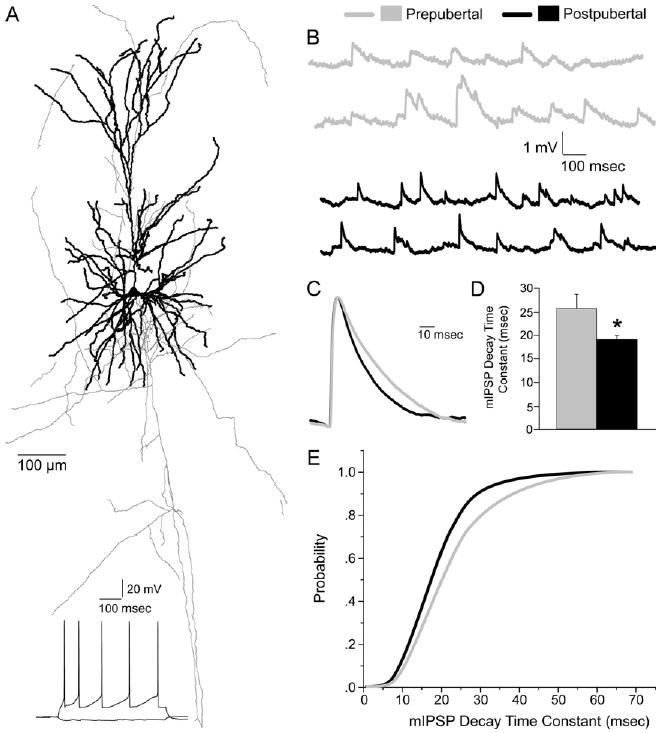

Electrophysiological Correlates of GABA Receptor Subunit Shift Across Adolescence

To test the functional significance of the progressive shift in expression of α1 versus α2 subunits through adolescence, we compared the properties of GABAA receptor-mediated mIPSPs recorded from layer 2/3 pyramidal neurons of pre- and postpubertal monkeys (Figure 6A and 6B). The amplitude and the 10%–90% rise time of the average mIPSP were not different between the two age groups (mIPSP amplitude: prepubertal, 1.29 ± .31 mV and postpubertal, 1.07 ± .12 mV, p = .5; mIPSP 10%–90% rise time: prepubertal, 2.02 ± .17 msec and postpubertal, 1.95 ± .08 msec, p = .7; n = 11 cells per age group). In contrast, the mIPSP decay time constant was significantly longer in neurons from prepubertal animals than in neurons from postpubertal animals (p < .05) (Figure 6C and D). This change was clearly demonstrated by the leftward shift of the cumulative probability distribution of the mIPSP decay time constant from prepubertal to postpubertal animals (Figure 6E). In addition to the shift in the α subunit composition of the GABAA receptors, differences in the mIPSP decay time constant could have been due, at least in part, to a developmentally regulated change in the membrane time constant of layer 2/3 pyramidal cells. However, the pyramidal cell membrane time constant did not differ between prepubertal (17.68 ± 1.77 msec) and postpubertal (16.35 ± 1.04 msec) monkeys.

Figure 6.

Changes in gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA)A receptor-mediated miniature inhibitory postsynaptic potentials (mIPSPs) during adolescence. (A) Reconstruction of the dendritic tree (thick lines) and axonal arbor (thin lines) of a representative pyramidal neuron in monkey dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) examined in this study. Trace below indicates the typical regular-spiking firing pattern of layer 3 pyramidal neurons. (B) Representative mIPSPs recorded from pyramidal neurons of prepubertal (gray traces) and postpubertal (black traces) monkeys. (C) Average mIPSPs obtained from at least 300 individual events recorded from two representative neurons were scaled to the same amplitude and superimposed, illustrating the longer decay time for neurons from prepubertal (gray trace) compared with postpubertal (black trace) monkeys. The mIPSP decay time constant becomes significantly faster during adolescence (prepubertal vs. postpubertal animals). (D) Bar graph summarizing the differences between age groups (Student's t test, *p < .05, n = 11 cells for each group). (E) Cumulative probability distribution curves of the mIPSP decay time constant in prepubertal (gray) and postpubertal (black) animals. The left shift of the curve from prepubertal to postpubertal animals indicates a higher fraction of shorter mIPSPs in postpubertal animals compared with prepubertal animals. A Kolmogorov-Smirnov test indicated a significant difference in the distribution (p < .05).

Discussion

We found that the expression of mRNAs encoding GABAA receptor α1 and α2 subunits in monkey DLPFC exhibit opposite trajectories during an extended period of postnatal development; α1 subunit mRNA expression was the lowest in newborns, increased gradually with age, and was greatest in adults, whereas α2 subunit mRNA exhibited the highest levels in neonates and then progressively declined with the lowest levels of expression in adult animals (Figures 1–4). Similarly, Western blot analysis revealed a progressive increase in α1 subunit protein levels with age (Figure 5), and our previous study demonstrated a substantial reduction in α2 subunit immunoreactivity with age (29). For α1 subunit expression, the magnitude of the age-related changes was greater for protein than for mRNA measures (Figures 2 and 5). This difference might reflect developmental changes in translational or posttranslational mechanisms that regulate the turnover of the subunit proteins.

In the rodent neocortex, α1 expression becomes detectable during the first postnatal week and increases rapidly after postnatal Day 6, whereas α2 expression is already high at birth and declines thereafter. These expression changes in α1 and α2 subunits end in the adult levels of expression by postnatal Day 20, before adolescence starts (24). In contrast, in the current study, the expression levels of α1 and α2 subunits progressively changed with age, including significant differences between prepubertal and adult animals, indicating that the developmental regulation of α1 and α2 subunit expression is quite protracted, extending through adolescence in primate DLPFC. However, in the hippocampus and entorhinal cortex, α1 subunit expression is reported to be high in both neonatal rodents and primates (34–36), indicating that the timing of developmental changes in α1 and α2 subunit expression might differ across cortical areas.

Our electrophysiologic analysis revealed that the duration of mIPSPs in pyramidal neurons was shorter in postpubertal animals compared with prepubertal animals (Figure 6). Given that α1-subunit-containing GABAA receptors have faster deactivation kinetics than those containing α2 subunits (25), these data are consistent with the observed changes in the ratio of α1 to α2 subunit protein levels during adolescence and indicate that these changes occur at the single-synapse level, at least in inputs onto pyramidal neurons. However, it is important to note that expression changes in β and γ subunits might also contribute to the change in mIPSP decay time during development (25,37).

Variations in systemic levels of sex steroids are associated with changes in GABAA receptor α1 and α2 subunit mRNA levels in the hippocampus, but not in the cingulate cortex, of rats (31). Consistent with the latter finding, we did not detect a significant effect of menstrual status on the expression of either mRNA in monkey DLPFC, although we cannot exclude a limitation in statistical power because of the small sample size of our study. In concert, the existing data suggest that the effects of sex steroids are less pronounced, or absent, in the neocortex compared with the hippocampus. In addition, because the effects of sex steroids on the expression of GABAA receptor subunits have previously been evaluated only in rodents (32), potential differences between species need to be considered.

Previous studies have demonstrated substantial developmental refinements in pre- and postsynaptic markers of GABA neurotransmission in the inputs from the chandelier subset of GABA neurons to the axon initial segment of pyramidal neurons in monkey DLPFC. For example, the density of GABAA receptor α2 subunit-immunoreactive axon initial segments was greatest in preadolescent animals, declined during adolescence, and reached the lowest level in adult animals (29). However, given that α2 subunits are also present at other synaptic sites (38), the marked decrease in cortical α2 mRNA expression with age is likely to reflect a postnatal downregulation of the α2 subunit broadly in GABA synapses rather than selectively in those at axon initial segments. Consistent with this interpretation, a substantial reduction in α2 subunit-immunoreactive puncta, indicating reduced α2 subunit expression in the neuropil (presumably at axosomatic and axodendritic synapses), was detected in post-adolescent animals compared with younger animals (29). Similarly, given that the α1 subunit is ubiquitously and abundantly expressed in the adult cortex (22,39), the postnatal increase in α1 subunit mRNA levels across cortical layers suggests that this increase is likely to occur at a large proportion of cortical GABA synapses. Taken together, these findings suggest that during postnatal development, the composition of GABAA receptors shifts from α2 to α1 subunits in diverse populations of GABA synapses on both pyramidal and GABA neurons.

In mature circuits, GABAA α1 and α2 subunits are differentially localized to the synapses made by two populations of basket cells onto the soma of pyramidal neurons; the α1 subunit predominates at synapses made by parvalbumin (PV)-positive basket cells (40), whereas the α2 subunit is postsynaptic to the axon terminals of PV-negative, putative cholecystokinin (CCK)-containing basket cells in adult rat hippocampus (41). Our findings might reflect a developmental replacement of α2 sub-units with α1 subunits at synapses made by PV-containing basket cells on pyramidal neurons, whereas α2 subunits remain predominant in synapses made by CCK-containing basket cells into adulthood. In the developing primary visual cortex, experience-dependent plasticity relies on the recruitment of α1 subunit-containing GABAA receptors to inhibitory synapses on pyramidal neuron soma made by PV-containing basket cells (42). Therefore, the increase in α1 subunit at these synapses might also be crucial for engaging neuronal plasticity in the developing primate DLPFC.

In the cortex, PV-containing GABA neurons are extensively and mutually interconnected into networks (43) which play a central role in generating gamma band (30–80 Hz) oscillations (44) that are thought to provide a temporal structure for cortical information processing, including those dependent on DLPFC circuitry such as working memory (45). The generation of gamma oscillations requires strong and fast inhibitory connections among PV-containing neurons and between PV-containing basket neurons and pyramidal cells (44), which appear to be provided by the fast deactivation kinetics of α1 subunit-containing GABAA receptors in these synapses (40). Therefore, an increase in α1 subunit expression during development might be important for establishing the network properties required to efficiently generate the gamma oscillations associated with cognitive functions. Although the resolution of our findings does not reveal the type of GABAA receptors present at specific synapses, our electrophysiologic findings of faster kinetics of inhibitory inputs to pyramidal neurons are consistent with increased α1 subunit expression at inhibitory synapses on pyramidal neurons, such as those made by PV-containing basket neurons (40). Given that each PV-containing neuron innervates a large number of pyramidal neurons (15), faster inhibition by PV-containing neurons across postnatal development might contribute to an improved ability to synchronize populations of pyramidal neurons at high frequencies. Therefore, increased α1 subunit levels at the synapses between both PV-containing neurons and PV-containing and pyramidal neurons might have synergistic roles in the generation of cortical gamma band oscillations. Consistent with this interpretation, in humans both working memory performance (9,12) and gamma band power (46) increase across postnatal development, including adolescence, and into early adulthood.

Previous postmortem studies have reported that muscimol binding to GABAA receptors was increased in the DLPFC of subjects with schizophrenia (47). However, in the same area, the levels of α1 subunit mRNA were found to be decreased (20), whereas α2 immunoreactivity in pyramidal neuron axon initial segments was increased (23). Because muscimol recognizes GABA binding sites in all types of GABAA receptors, understanding how these disease-associated differences in α subunit expression contribute to the increase in total GABAA receptor binding requires systematic evaluation of the expression of other GABAA receptor subunits in schizophrenia. It remains to be determined whether these changes in the expression of α subunits represent a primary pathology affecting postsynaptic GABAA receptors or a secondary process induced by the alterations in presynaptic GABA neurons (15). However, given the developmental profiles of α1 and α2 subunit expression observed in this study, the elevated α2 subunit expression and the decreased α1 mRNA levels in schizophrenia might reflect a developmental dysregulation of GABAA receptor α subunit expression in which the changes in subunit expression with age fail to undergo their full course. This disruption might contribute to the cognitive deficits in patients with schizophrenia by compromising neuronal plasticity and gamma band oscillations, both of which seem to be critical for the cognitive processes mediated by DLPFC circuitry (48).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression Young Investigator Award (TH) and by National Institute of Health grant MH051234 (DAL). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Mental Health or the National Institutes of Health.

David A. Lewis currently receives research support from the BMS Foundation, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Curridium Ltd., and Pfizer and in 2006-2008 served as a consultant to AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Hoffman-Roche, Lilly, Merck, Neurogen, Pfizer, Sepracor, and Wyeth.

Footnotes

All other authors reported no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

Supplementary material cited in this article is available online.

References

- 1.Weinberger DR, Berman KF, Zec RF. Physiologic dysfunction of dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in schizophrenia. I. Regional cerebral blood flow evidence. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1986;43:114–124. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1986.01800020020004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goldman-Rakic PS. Working memory dysfunction in schizophrenia. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1994;6:348–357. doi: 10.1176/jnp.6.4.348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davidson M, Reichenberg A, Rabinowitz J, Weiser M, Kaplan Z, Mark M. Behavioral and intellectual markers for schizophrenia in apparently healthy male adolescents. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:1328–1335. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.9.1328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saykin AJ, Shtasel DL, Gur RE, Kester DB, Mozley LH, Stafiniak P, Gur RC. Neuropsychological deficits in neuroleptic naive patients with first-episode schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51:124–131. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950020048005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Green MF. Schizophrenia from a Neurocognitive Perspective: Probing the Impenetrable Darkness. Boston: Allyn and Bacon; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cosway R, Byrne M, Clafferty R, Hodges A, Grant E, Abukmeil SS, et al. Neuropsychological change in young people at high risk for schizophrenia: Results from the first two neuropsychological assessments of the Edinburgh High Risk Study. Psychol Med. 2000;30:1111–1121. doi: 10.1017/s0033291799002585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lewis DA, Lieberman JA. Catching up on schizophrenia: Natural history and neurobiology. Neuron. 2000;28:325–334. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00111-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Diamond A. Normal development of prefrontal cortex from birth to young adulthood: Cognitive functions, anatomy and biochemistry. In: Stuss DT, Knight RT, editors. Principles of Frontal Lobe Function. London: Oxford University Press; 2002. pp. 466–503. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Luna B, Garver KE, Urban TA, Lazar NA, Sweeney JA. Maturation of cognitive processes from late childhood to adulthood. Child Devel. 2004;75:1357–1372. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00745.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alexander GE, Goldman PS. Functional development of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex: An analysis utilizing reversible cryogenic depression. Brain Res. 1978;143:233–249. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(78)90566-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alexander GE. Functional development of frontal association cortex in monkeys: Behavioral and electrophysiological studies. Neurosciences Res Prog Bull. 1982;20:471–479. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Crone EA, Wendelken C, Donohue S, van Leijenhorst L, Bunge SA. Neurocognitive development of the ability to manipulate information in working memory. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:9315–9320. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510088103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weinberger DR. Implications of normal brain development for the pathogenesis of schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1987;44:660–669. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1987.01800190080012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lewis DA, Levitt P. Schizophrenia as a disorder of neurodevelopment. Ann Rev Neurosci. 2002;25:409–432. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.25.112701.142754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lewis DA, Hashimoto T, Volk DW. Cortical inhibitory neurons and schizophrenia. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6:312–324. doi: 10.1038/nrn1648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Akbarian S, Kim JJ, Potkin SG, Hagman JO, Tafazzoli A, Bunney WE, Jr, Jones EG. Gene expression for glutamic acid decarboxylase is reduced without loss of neurons in prefrontal cortex of schizophrenics. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1995;52:258–266. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950160008002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Volk DW, Austin MC, Pierri JN, Sampson AR, Lewis DA. Decreased glutamic acid decarboxylase67 messenger RNA expression in a subset of prefrontal cortical gamma-aminobutyric acid neurons in subjects with schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57:237–245. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.3.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guidotti A, Auta J, Davis JM, Gerevini VD, Dwivedi Y, Grayson DR, et al. Decrease in reelin and glutamic acid decarboxylase67 (GAD67) expression in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57:1061–1069. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.11.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hashimoto T, Bergen SE, Nguyen QL, Xu B, Monteggia LM, Pierri JN, et al. Relationship of brain-derived neurotrophic factor and its receptor TrkB to altered inhibitory prefrontal circuitry in schizophrenia. J Neurosci. 2005;25:372–383. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4035-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hashimoto T, Arion D, Unger T, Maldonado-Aviles JG, Morris HM, Volk DW, et al. Alterations in GABA-related transcriptome in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex of subjects with schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry. 2008;13:147–161. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4002011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Straub RE, Lipska BK, Egan MF, Goldberg TE, Callicott JH, Mayhew MB, et al. Allelic variation in GAD1 (GAD67) is associated with schizophrenia and influences cortical function and gene expression. Mol Psychiatry. 2007;12:854–869. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mohler H. GABA(A) receptor diversity and pharmacology. Cell Tissue Res. 2006;326:505–516. doi: 10.1007/s00441-006-0284-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Volk DW, Pierri JN, Fritschy JM, Auh S, Sampson AR, Lewis DA. Reciprocal alterations in pre- and postsynaptic inhibitory markers at chandelier cell inputs to pyramidal neurons in schizophrenia. Cereb Cortex. 2002;12:1063–1070. doi: 10.1093/cercor/12.10.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fritschy JM, Paysan J, Enna A, Mohler H. Switch in the expression of rat GABAA-receptor subtypes during postnatal development: An immunohistochemical study. J Neurosci. 1994;14:5302–5324. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-09-05302.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Farrant M, Nusser Z. Variations on an inhibitory theme: Phasic and tonic activation of GABA(A) receptors. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6:215–229. doi: 10.1038/nrn1625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hollrigel GS, Soltesz I. Slow kinetics of miniature IPSCs during early postnatal development in granule cells of the dentate gyrus. J Neurosci. 1997;17:5119–5128. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-13-05119.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rao SG, Williams GV, Goldman-Rakic PS. Destruction and creation of spatial tuning by disinhibition: GABAA blockade of prefrontal cortical neurons engaged by working memory. J Neurosci. 2000;20:485–494. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-01-00485.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sawaguchi T, Matsumura M, Kubota K. Delayed response deficits produced by local injection of bicuculline into the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in Japanese macaque monkeys. Exp Brain Res. 1989;75:457–469. doi: 10.1007/BF00249897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cruz DA, Eggan SM, Lewis DA. Postnatal development of pre- and post-synaptic GABA markers at chandelier cell inputs to pyramidal neurons in monkey prefrontal cortex. J Comp Neurol. 2003;465:385–400. doi: 10.1002/cne.10833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gonzalez-Burgos G, Kroener S, Zaitsev AV, Povysheva NV, Krimer LS, Barrionuevo G, Lewis DA. Functional maturation of excitatory synapses in layer 3 pyramidal neurons during postnatal development of the primate prefrontal cortex. Cereb Cortex. 2008;18:626–637. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhm095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weiland NG, Orchinik M. Specific subunit mRNAs of the GABAA receptor are regulated by progesterone in subfields of the hippocampus. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1995;32:271–278. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(95)00087-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Biggio G, Follesa P, Sanna E, Purdy RH, Concas A. GABAA-receptor plasticity during long-term exposure to and withdrawal from progesterone. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2001;46:207–241. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7742(01)46064-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kralic JE, Korpi ER, O'Buckley TK, Homanics GE, Morrow AL. Molecular and pharmacological characterization of GABA(A) receptor alpha1 subunit knockout mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2002;302:1037–1045. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.036665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Laurie DJ, Wisden W, Seeburg PH. The distribution of thirteen GABAA receptor subunit mRNAs in the rat brain. III. Embryonic and postnatal development. J Neurosci. 1992;12:4151–4172. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-11-04151.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hornung JP, Fritschy JM. Developmental profile of GABAA-receptors in the marmoset monkey: Expression of distinct subtypes in pre- and postnatal brain. J Comp Neurol. 1996;367:413–430. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19960408)367:3<413::AID-CNE7>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kanaumi T, Takashima S, Iwasaki H, Mitsudome A, Hirose S. Developmental changes in the expression of GABAA receptor alpha 1 and gamma 2 subunits in human temporal lobe, hippocampus and basal ganglia: An implication for consideration on age-related epilepsy. Epilepsy Res. 2006;71:47–53. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2006.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Houston CM, Hosie AM, Smart TG. Distinct regulation of beta2 and beta3 subunit-containing cerebellar synaptic GABAA receptors by calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II. J Neurosci. 2008;28:7574–7584. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5531-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nusser Z, Sieghart W, Benke D, Fritschy JM, Somogyi P. Differential synaptic localization of two major γ-aminobutyric acid type A receptor α subunits on hippocampal pyramidal cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:11939–11944. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.21.11939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fritschy JM, Mohler H. GABAA-receptor heterogeneity in the adult rat brain: Differential regional and cellular distribution of seven major subunits. J Comp Neurol. 1995;359:154–194. doi: 10.1002/cne.903590111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Klausberger T, Roberts JD, Somogyi P. Cell type- and input-specific differences in the number and subtypes of synaptic GABAAreceptors in the hippocampus. J Neurosci. 2002;22:2513–2521. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-07-02513.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ny'ri G, Freund TF, Somogyi P. Input-dependent synaptic targeting of α2 subunit-containing GABAA receptors in synapses of hippocampal pyramidal cells of the rat. Eur J Neurosci. 2001;13:428–442. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2001.01407.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Katagiri H, Fagiolini M, Hensch TK. Optimization of somatic inhibition at critical period onset in mouse visual cortex. Neuron. 2007;53:805–812. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kisvarday ZF, Beaulieu C, Eysel UT. Network of GABAergic large basket cells in cat visual cortex (Area 18): Implication for lateral disinhibition. J Comp Neurol. 1993;327:398–415. doi: 10.1002/cne.903270307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bartos M, Vida I, Jonas P. Synaptic mechanisms of synchronized gamma oscillations in inhibitory interneuron networks. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8:45–56. doi: 10.1038/nrn2044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jensen O, Kaiser J, Lachauz JP. Human gamma-frequency oscillations associated with attention and memory. Trends Neurosci. 2007;30:317–324. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2007.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Uhlhaas PJ, Roux F, Singer W, Haenschel C, Sireteanu R, Rodriguez E. Development of task-related neural synchrony reflects maturation and restructuring of cortical networks in humans. Soc Neuroscience Online Abstract. 2007;791:11. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Benes FM, Vincent SL, Marie A, Khan Y. Up-regulation of GABA-A receptor binding on neurons of the prefrontal cortex in schizophrenic subjects. Neuroscience. 1996;75:1021–1031. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(96)00328-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lewis DA, Gonzalez-Burgos G. Neuroplasticity of neocortical circuits in schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacol Rev. 2008;33:141–165. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.