Abstract

Light quality and, in particular, its content of blue light is involved in plant functioning and morphogenesis. Blue light variation frequently occurs within a stand as shaded zones are characterized by a simultaneous decrease of PAR and blue light levels which both affect plant functioning, for example, gas exchange. However, little is known about the effects of low blue light itself on gas exchange. The aims of the present study were (i) to characterize stomatal behaviour in Festuca arundinacea leaves through leaf gas exchange measurements in response to a sudden reduction in blue light, and (ii) to test the putative role of Ci on blue light gas exchange responses. An infrared gas analyser (IRGA) was used with light transmission filters to study stomatal conductance (gs), transpiration (Tr), assimilation (A), and intercellular concentration of CO2 (Ci) responses to blueless PAR (1.80 μmol m−2 s−1). The results were compared with those obtained under a neutral filter supplying a similar photosynthetic efficiency to the blueless PAR filter. It was shown that the reduction of blue light triggered a drastic and instantaneous decrease of gs by 43.2% and of Tr by 40.0%, but a gradual stomatal reopening began 20 min after the start of the low blue light treatment, thus leading to new steady-states. This new stomatal equilibrium was supposed to be related to Ci. The results were confirmed in more developed plants although they exhibited delayed and less marked responses. It is concluded that stomatal responses to blue light could play a key role in photomorphogenetic mechanisms through their effect on transpiration.

Keywords: Leaf growth, light, photomorphogenesis, photosynthesis, tall fescue

Introduction

Light quality is considered to play a key role in plant architecture and the dynamics of vegetation (Kasperbauer and Hunt, 1992; Ballaré et al., 1997), through wavelengths known as morphogenetically active radiation (MAR) (Varlet-Grancher et al., 1993a). During plant development, the light phylloclimate (Chelle, 2005) changes as a result of (i) geometric interactions between incident light and phytoelements of the plant canopy and (ii) optical properties of vegetal stands. Geometric interactions lead to the formation of shaded zones which occur both within plants and between plants. Light phylloclimate variations also result from the optical properties of the leaves (Smith, 1982), i.e. their photosynthetic pigments that mainly absorb in the blue and red wavelengths. Therefore, shaded zones within a plant canopy are also characterized by a decrease in (i) the red:far-red ratio (R:FR), (ii) the photosynthetically active radiation (PAR, 400–700 nm) including (iii) a decrease in a large part of the blue light (350–500 nm). As a result, there are spatial, temporal, and directional light quality variations within a stand due to environmental factors such as the sun's course, cloudiness or the wind (Combes et al., 2000; Escobar-Gutiérrez et al., 2009). These variations in light quality (i.e. in the solar radiation spectrum) act as photomorphogenic signals sensed by plants through their photoreceptors. Variations in blue light level are perceived by two main photoreceptors: cryptochromes and phototropins (Lin, 2002) which are two systems acting as photon counters (Smith, 1982) in ultraviolet A (UVA) and blue light. Cryptochromes are active within the range of 390–530 nm with a fairly flat response between 390 nm and 480 nm (Ahmad et al., 2002), whereas phototropin activity shows a clear peak at 450 nm (Christie et al., 1998). In practice, UVA and blue light signals are usually characterized by the photon irradiance integrated over various wavebands within the 350–500 nm region (Varlet-Grancher et al., 1993b). The perception of blue light through these photoreceptors allows plants to sense their nearby environment and, in particular, the intensity of competition for light. Consequently, blue light is known to trigger a large variety of photomorphogenic (sensu lato) responses in plants (Casal and Alvarez, 1988; Ballaré and Casal, 2000; Christie and Briggs, 2001) through a range of mechanisms at the molecular, cellular (Lasceve et al., 1999), and organ levels (Cosgrove and Green, 1981).

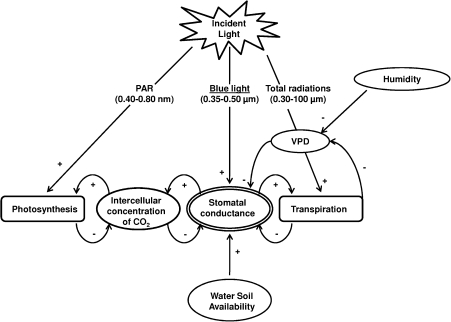

Besides its morphogenic effects, blue light also influences plant functioning. At the leaf scale, fluctuations in blue light involve changes in both energy balance components (Jones, 1992) and in gas exchange dynamics through stomatal functioning. Blue light effects on stomatal behaviour have been a topical issue for several decades (Zeiger et al., 1987; Gautier, 1991; Shimazaki et al., 2007; Lawson, 2009). For example, it has been well documented that blue light pulses induced a transient stomatal opening in various species (Assmann, 1988), that may be important for the optimization of water use efficiency (Karlsson and Assmann, 1990). Nevertheless, the blue-light regime is embedded within a tangled network of interacting environmental factors that concomitantly affect stomatal functioning which, in turn, modifies these factors (Fig. 1). Briefly, the blue light effect on stomata could lead to variations of intercellular CO2 concentration (Ci) and, consequently, of leaf assimilation rate which also depends on electron flow supplied by the PAR. Besides, leaf transpiration rate is both mediated by incident thermal radiation and by stomatal opening. Such mediation of leaf transpiration by blue light has been little studied (Brogardh, 1975; Karlsson, 1986) despite the effects of transpiration on plant water status and, consequently, on plant growth (Bradford and Hsiao, 1982).

Fig. 1.

Conceptual model of the stomatal control by environmental factors and consequences on gas exchange.

In addition, specific studies on blue light are complex as this wavelength domain is also active on PAR-dependent mechanisms. In most studies, the lack of blue light was compensated for by saturating photosynthesis with red light backgrounds. Because of the higher relative response of photosynthesis to red light (McCree, 1972), such treatments did not allow photosynthetic and light quality effects on stomata to be separated. Moreover, Sager and colleagues (Sager et al., 1982, 1988) have demonstrated that, under artificial light, the best indicator of photosynthetic utilization of a radiation source was not PAR level (or PFD; photosynthetic flux density) but photosynthetic efficiency.

Summarizing, our current understanding of the effect of blue light on stomatal functioning mainly comes from studies where blue light has been added (e.g. pulses). The opposite situation, i.e. when blue light is lacking or present at low levels, is also ecologically relevant as shaded zones are characterized by the sudden attenuation of blue light. Nevertheless, there is little knowledge available on stomatal responses in these conditions. It might be supposed that low blue light levels with a constant PAR would lead to stomatal closure. However, the complex and numerous feedbacks and feedforwards (Fig. 1) that occur at the stomatal level lead us to believe that the stomatal closure induced by a low blue light level would trigger a decrease in the intercellular concentration of CO2 which may, in turn, induce stomatal reopening.

This study focused on low blue light effects on stomata in order to quantify transpiration rate variations. Its objectives were (i) to characterize stomatal behaviour through leaf gas exchange measurement in response to a sudden and strong reduction in blue light, while maintaining relatively high PAR levels and equivalent photosynthetic efficiencies, and (ii) to test the putative role of Ci in blue light-induced gas exchange changes. Stomatal conductance, leaf transpiration, photosynthesis, and internal CO2 concentration were recorded on mature tall fescue (Festuca arundinacea) leaves submitted to different light treatments and to a range of CO2 concentrations.

Materials and methods

Plant material and growing conditions

Tall fescue clones (Festuca arundinacea Schreb. cv. Clarine) were planted in 0.4 l plastic pots filled with sand. Plants were grown in a cabinet at 80% relative humidity and were automatically watered eight times a day with a complete nutrient solution. The volume supplied to plants was varied from 30 ml d−1 to 80 ml d−1 according to their stage. Plants were grown under 380 μmol m−2 s−1 of PAR in a growth cabinet, with a 14 h photoperiod provided by metal halide lamps (HQI 400 W, Osram, France). Tall fescue clones were regularly produced in order to obtain plants at the same stage of development for gas exchange measurements.

Plants to be tested were transferred into a walk-in growth chamber for measurements where a 486 μmol m−2 s−1 PAR level was provided by metal halide lamps (HQI 400 W, Osram, France) with a 14 h photoperiod and a similar spectral composition to the growth cabinet.

The temperature in both growth cabinets was maintained at 19 °C both day and night.

Gas exchange measurements

Gas exchange measurements were performed using a portable infrared gas analyser (IRGA) (LI-6400; Li-Cor Inc, Lincoln, NE, USA) within a narrow leaf chamber (2×6 cm2; LI-6400-11). The top window was covered with Propafilm and had a PAR light sensor (GaAsp) beneath. The opaque base held a leaf temperature thermocouple (Li-6400-04). Stomatal conductance (gs), leaf transpiration rate (Tr), leaf photosynthesis (A), and intercellular concentration of CO2 (Ci), were then monitored in attached leaves under different light conditions and different CO2 concentrations. Data stored by the LI-6400 were automatically corrected by leaf area corresponding to the leaf portion enclosed within the leaf chamber.

Light treatments and measurements

UVA-blue light is defined as radiation in the range of 350–500 nm. In this study, in order to avoid UVA effects, both the walk-in and growth chambers were equipped with a polycarbonate filter that absorbed all radiation under 400 nm so that blue light was restricted to the range 400–500 nm.

The effects of low blue light on leaf gas exchange were studied by using light transmission filters on the top window of the leaf chamber. Low blue light levels (1.80 μmol m−2 s−1) were thus obtained with a Lee Filter HT 015 which also supplies high PAR levels (see detailed properties in Fig. 2A). The amount of transmitted PAR into the leaf chamber was calculated by using the optical properties of both transmission filters and the Propafilm fixed on the top of the leaf chamber (measured with the optical sphere and spectroradiometer Li-Cor 1800). The amount of blue light was calculated by using Equation 1 (de Berranger et al., 2005):

| (1) |

where BL is the quantity of blue light (μmol m−2 s−1) and Nλ is the photon flux density in the wavelength λ (μmol m−2 s−1 nm−1)

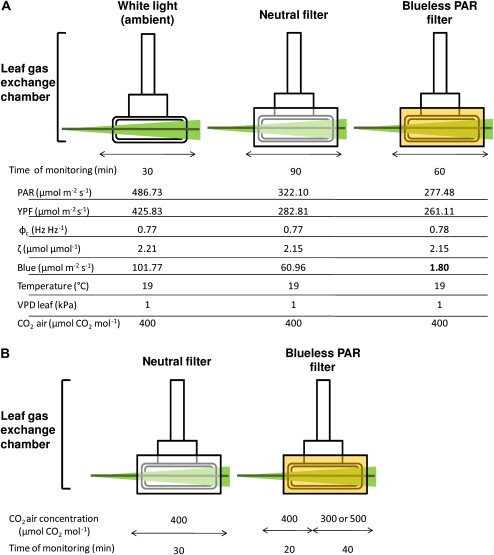

Fig. 2.

Experimental protocol. Light treatments were obtained by placing light transmission filters on the top window of the leaf chamber. Environmental parameters of each condition are specified. PAR, photosynthetically active radiation; YPF, yield photosynthetic efficiency; ϕc, phytochrome photoequilibrium; ζ, zeta red:far red ratio; VPD leaf, vapour pressure deficit; the UVA-blue domain was defined between 400 nm and 500 nm. (A) Experiment 1. Gas exchange responses to the light treatment. Leaves were first placed in the gas exchange chamber under the white light of the walk-in growth chamber. Each leaf was submitted to the sequence of three light treatments: white light (ambient), neutral shade, and blueless PAR. Results were obtained from a set of young plants (n=5) and then from more developed plants (n=5). (B) Experiment 2. Interaction between blueless PAR and intercellular CO2 concentrations. Leaves were put into the gas exchange chamber straight under the neutral filter. The blueless PAR filter was then placed on the gas exchange chamber for 60 min. In order to modify the Ci, two levels of CO2 air concentration were imposed (either 500 or 300 μmol CO2 mol−1) 20 min after the beginning of the low-blue light treatment. Except for the CO2, all of the other environmental conditions were maintained as described in Fig. 2A. Two plants were either submitted to an increase or a decrease of the CO2 air concentration.

In view of the very low quantity of blue light, it was considered that blue light was lacking under this filter. A neutral filter (Lee filter 216) was used as a control providing a photosynthetic efficiency similar to the blueless PAR filter (Fig. 2A). The calculation of photosynthetic efficiency corresponds to an integration in the PAR wavelengths of the PFD times the relative quantum yield of each waveband (Equation 2; de Berranger et al., 2005):

| (2) |

where Y is the photosynthetic efficiency (μmol m−2 s−1), Nλ is the photon flux density in the wavelength λ (μmol m−2 s−1 nm−1), and φλ is the relative quantum yield of each waveband λ.

The Lee 216 filter provided a neutral shade as it lowered the energy from all wavelengths of the incident light by about 25%. The effects of blue light were then analysed by comparing the results between blueless and neutral filters.

Experimental protocol

Experiment 1: gas exchange response to blueless PAR:

Gas exchange of the last fully expanded leaf was measured. Leaves were first placed in the gas exchange chamber under the white light of the walk-in growth chamber for 2 h of acclimation. Leaves were therefore allowed to reach a steady-state level of stomatal conductance for 2 h in order to achieve full stomatal activity. In this experiment, leaf temperature was set at 19 °C, the vapour pressure deficit (VPD) was fixed at 1 kPa, and the ambient CO2 level at 400 μmol CO2 mol−1 (the level set in the reference chamber of the Li-Cor 6400). Each leaf was then submitted to a sequence of three light treatments (Fig. 2A): white light (ambient-W), neutral shade (N), and blueless PAR (B–). Stomatal conductance, leaf transpiration, leaf photosynthesis, and internal CO2 concentration were recorded for 30 min under white light. Leaves were then submitted to the neutral light treatment (neutral light filter) for 90 min of monitoring. Finally, the blueless PAR filter was used immediately after the neutral treatment and gas exchange was measured for 60 min. Measurements were made on two sets of five plants. Gas exchange was first recorded on plants that reached the stage of three mature leaves on the main tiller and then on a second set of more developed plants: four to five mature leaves on the main axis and eight tillers (measurements were made on the axial tiller).

Experiment 2: interaction between blueless PAR and intercellular CO2 concentration:

In the second experiment (Fig. 2B), interactions between blueless PAR and intercellular CO2 concentration and their effects on stomatal conductance were studied. Gas exchange of the last fully expanded leaf was measured. Leaves were then put into the gas exchange chamber under the neutral filter for 2 h of acclimation. Leaf temperature, VPD, and CO2 concentration were fixed in the same way as in the first experiment. Leaf gas exchange was then recorded for 30 min under the neutral filter. The blueless PAR filter was finally placed on the gas exchange chamber for 60 min. Two levels of CO2 (either 300 or 500 μmol CO2 mol−1) were then imposed for 20 min after the start of the blueless PAR treatment. This experiment was repeated on four plants from the first set (younger ones): two experienced a decrease of ambient CO2 to 300 μmol CO2 mol−1, and two an increase to 500 μmol CO2 mol−1.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted in SAS 8.01 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed with the GLM procedure, in order to determine whether or not light treatment had a significant effect in gs, Tr, A, and Ci. Homocedasticity was verified by the random distribution in the residuals’ plot for all variables. Comparisons of gs, Tr, A, and Ci values among the light treatments (neutral versus blueless PAR) and among the different periods were performed using Scheffe's method (Steel and Torrie, 1980). The significance threshold was fixed at the 0.05 probability level (α) for all statistical tests. The assumption that residuals were normally distributed with a mean of zero was also verified for all variables.

The dynamics of stomatal conductance in response to treatments (light or CO2) were fitted by two non-linear models.

(i) Stomatal closure was fitted by the exponential decrease function:

| (3) |

where gs0 represents the stomatal conductance at the beginning of the blueless PAR treatment, kc is a time-inverse parameter, and t is time. The highest rate of stomatal closure occurred at t0.

(ii) Stomatal reopening was fitted by the function:

| (4) |

where gsmax represents the maximum stomatal conductance (asymptote), ko is a time-inverse parameter, and t is time.

Non-linear models were fitted using the least squares method (Steel and Torrie, 1980). Parameters were optimized using the Levenberg–Marquardt iterative method with automatic computation of the analytical partial derivatives. Initial seed values for the parameters depended on the variable being fitted (Escobar-Gutiérrez et al., 2009).

Results

Blueless PAR effects on stomatal conductance and transpiration

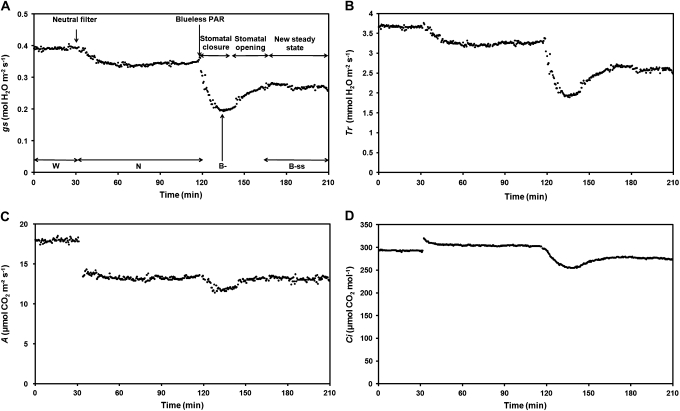

A typical gs response to light treatment in a younger plant is shown in Fig. 3A. This figure allowed the gs kinetic to be divided into four periods in order to quantify the stomatal response among plants: (i) gs initial values under the white light of the growing chamber (W), (ii) gs response to the neutral treatment which represents the control (N), (iii) the maximum effect of the blueless PAR treatment, i.e. minimal gs values (B–), due to a stomatal closure, and (iv) the stomatal reopening which led to new steady-states (B–ss). The overall data were then compiled into histograms in Fig. 4A (open bars) according to the periods defined previously.

Fig. 3.

Typical responses of stomatal conductance (A), transpiration rate (B), assimilation rate (C), and intercellular CO2 concentration (D) to the light treatments in a younger plant. Leaves were first placed under white light (W: PAR=486 μmol m−2 s−1, Blue=101 μmol m−2 s−1) and were then submitted to a neutral shade (N: PAR=322 μmol m−2 s−1, Blue=61 μmol m−2 s−1). Finally, blue light was reduced to 1.80 μmol m−2 s−1 (PAR=277 μmol m−2 s−1) while maintaining an equivalent photosynthetic efficiency. Distinction was made between minimal values reached under blueless PAR treatment: B– (maximum effect of the blueless PAR treatment) and the new steady-states reached 45 min after blue light reduction (B–ss).

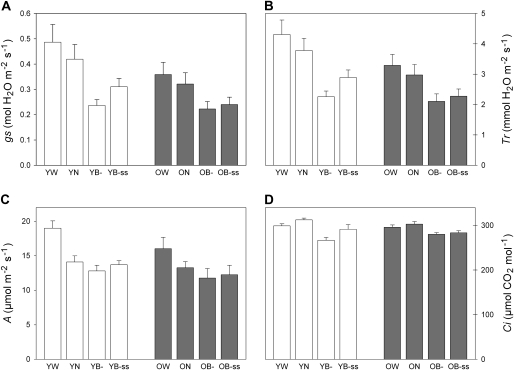

Fig. 4.

Leaf gas exchange responses to the different light conditions in young (Y) and older (O) plants. Stomatal conductance (A), transpiration rate (B), assimilation rate (C), and intercellular CO2 concentration (D) were measured under ambient light=white light (W: PAR=486 μmol m−2 s−1, Blue=101 μmol m−2 s−1), neutral shade (N: PAR=322 μmol m−2 s−1, Blue=61 μmol m−2 s−1), and blueless PAR for transient (B–) and steady-states (B–ss) responses (PAR=277 μmol m−2 s−1, Blue=1.80 μmol m−2 s−1). n=5 for both sets of plants. Results are mean values ±SD.

Under white light (W), the stomatal conductance in younger plants was 0.39–0.55 mol H2O m−2 s−1. The neutral light filter application (N) decreased gs by 13.7±3.7% and gs values remained stable afterwards. By contrast, blue light reduction (B–) to 1.80 μmol m−2 s−1 triggered, in all of the measured leaves, a transient drastic and instantaneous (in the order of 1 min) decrease of gs (Fig. 3A) by 43.2±4.5% compared with the neutral treatment (P <0.0001; Table 1A). A minimal stomatal conductance of 0.24±0.02 mol H2O m−2 s−1 was reached 19±2 min after blue light was withdrawn, after which a progressive increase in gs occurred into the blueless PAR treatment. gs values then stabilized (B–ss) at 0.31±0.03 mol H2O m−2 s−1, 45 min after the start of the blue light reduction, at 74.5±5.5% of values measured under the neutral filter. It was therefore considered that gs had reached a new and intermediate steady-state level significantly different from both the neutral treatment and from the minimum within the blueless PAR treatment (P <0.0001 and P <0.01, respectively; Table 1A).

Table 1.

Results of the ANOVA test (P values).

| (A) | YB– | YB–ss | |

| YN | gs | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Tr | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |

| A | <0.001 | ns | |

| Ci | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |

| YB– | gs | <0.01 | |

| Tr | <0.001 | ||

| A | <0.01 | ||

| Ci | <0.0001 |

| (B) | OB– | OB–ss | |

| ON | gs | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Tr | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |

| A | <0.0001 | <0.01 | |

| Ci | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |

| OB– | gs | ns | |

| Tr | <0.05 | ||

| A | <0.1 | ||

| Ci | <0.1 |

(A) Comparisons performed in less developed plants (Y) and (B) in more developed plants (O). Statistical tests were performed between stomatal conductance (gs), transpiration rate (Tr), assimilation rate (A), and intercellular concentration of CO2 (Ci) measured under the neutral treatment (N), the blueless PAR maximum effect (B–) ,and when new steady-states (B–ss) were reached. Ns, no statistical difference. n= 5 for both younger and older plants.

Similarly to gs, transpiration rates (Tr) were highest under the ambient light treatment (Fig. 3B), ranging from 3.66 to 4.91 mmol H2O m−2 s−1 (Fig. 4B, open bars). The application of the neutral treatment decreased the transpiration rate by 12.1±3.3% which then stabilized at 3.78±0.36 mmol H2O m−2 s−1. Under the blueless PAR treatment, Tr significantly decreased by 40.0±4.3% compared with the neutral treatment (P <0.0001; Table 1A) and then reached a minimal value of 2.26±0.17 mmol H2O m−2 s−1. Tr then increased and became stabilized 45 min after the blue light reduction, at 76.8±4.7% of the transpiration rate observed under the neutral conditions. A new steady-state level was reached as B–ss values were significantly different from the neutral and the minimum within the blueless PAR treatment (B–) (P <0.0001 and P <0.001, respectively; Table 1A).

Responses of gs (Fig. 4A, shaded bars), and Tr (Fig. 4B, shaded bars), were also measured on the set of older plants. Under ambient conditions gs and Tr were 0.31–0.42 mol H2O m−2 s−1 and 2.92–3.76 mmol H2O m−2 s−1, respectively. Under white light, these values were significantly lower than those found in younger plants (statistical test not shown). gs and Tr then decreased under neutral treatment by 10.5±1.5% and 10.0±1.4%, respectively. The absence of blue light triggered a significant decrease in gs by 30.7±3.8% and Tr by 29.1±3.4% (P <0.0001 for both gs and Tr; Table 1B). Minimal gs values were measured 26±5.75 min (data not shown) after the blue light reduction and finally reached steady-state levels at 75.0±4.0% and 76.7±3.7% of the neutral treatment for gs and Tr, respectively.

Absolute minimal values (B–) of gs and Tr were not significantly different between the two sets of plants, i.e. whatever plant stage the transient response (B–) of stomata lead to similar levels of stomatal conductance. Despite similar stomatal behaviour, gs and Tr responses to blueless PAR in older plants differ by their amplitude and by their response time. In these plants, gs and Tr decreased by 30.7% and 29.1% in response to blueless PAR instead of 43.2% and 40.0% in younger plants. Response to blueless PAR was also shifted by 7 min in older plants. This stomatal closure (kc) was conducted at 0.24% s−1 in more developed plants instead of 0.33% s−1 in the younger plants (Table 2). Stomatal reopening was also less marked in more developed plants as gs values were not significantly different between B– and B–ss periods (Table 1B). gs increased from 0.24 to 0.31 mol H2O m−2 s−1 in younger plants (+31.6%) whereas the stomatal reopening did not exceed 8.2% in older plants (from 0.22 to 0.24 mol H2O m−2 s−1). The rate of stomatal reopening (ko) was therefore only calculated in younger plants: ko= 0.10% s−1 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Rates of stomatal movements in response to blueless PAR in younger and older plants

| Younger plants | Older plants | ||

| CO2 air concentration (μmol CO2 mol−1) | 400 | 400 | 400 |

| Parameter (% s−1) | kc | ko | kc |

| Mean value | 0.33 | 0.10 | 0.24 |

| SD | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.06 |

Values were calculated after fitting of two non-linear functions (cf. statistical analysis). kc represents the rate of stomatal closure and ko the rate of stomatal opening. Mean values are shown ±SD. n=5 for each set of plants.

Blueless PAR effects on photosynthesis

A typical photosynthesis (A) response to light treatments, in younger plants, is shown in Fig. 3C, and data are summarized in Fig. 4C (open bars).

Mean A under white light was 19.01±0.94 μmol CO2 m−2 s−1. The neutral treatment decreased the assimilation rate to 14.10±0.79 μmol CO2 m−2 s−1. Such a decrease of 4.91 μmol CO2 m−2 s−1 seems to be related to the PAR reduction that occurred under the neutral filter (–165 μmol m−2 s−1; Fig. 2A). After 1 h of monitoring, the blueless PAR treatment was applied and triggered a slight decrease of the assimilation rate at 12.81±0.73 μmol CO2 m−2 s−1 (P <0.001; Table 1A). After 45 min, leaf photosynthesis stabilized at 13.71±0.51 μmol CO2 m−2 s−1 and therefore regained levels close to those found under the neutral treatment (difference not significant between these two treatments; Table 1A).

Mean A measured in older plants (Fig. 4C, shaded bars) was 16.00±1.47 μmol CO2 m−2 s−1 under white light. Photosynthesis kinetics under neutral and blueless PAR filters were similar to those observed in younger plants and afterwards stabilized at 12.25±1.23 μmol CO2 m−2 s−1 although it did not regain levels close to those found under the neutral treatment (P <0.01 between N and B–ss; Table 1B).

Blueless PAR effects on intercellular CO2 concentration (Ci)

Contrary to other variables, Ci was not directly measured by the IRGA. Ci is an estimated value derived from CO2 concentration, stomatal conductance to CO2, and transpiration and assimilation rates.

Estimated intercellular CO2 responses in younger plants are shown in Fig. 3D (typical response) and summarized in Fig. 4D (open bars). Under white light, mean Ci was 300.00±4.20 μmol CO2 mol−1. An increase of 5% in Ci was observed in response to the neutral treatment. Such an increase could be explained by the reduction of the CO2 assimilation rate which is greater (25% in younger plants) than the reduction of the CO2 influx (13.7%) due to the decrease in PAR. By contrast, blueless PAR led to a rapid decrease of Ci to a minimal value of 267.00±5.50 μmol CO2 mol−1 (P <0.0001; Table 1A), linked to the strong stomatal closure that occurred under blueless PAR conditions. Then an increase was observed leading in a new steady-state, reached 45 min after the blue light reduction, at 92.0±2.7% of Ci values measured under the neutral filter.

Figure 4D (shaded bars) shows the Ci response to light treatment in older plants. Ci level under white light was 295 μmol CO2 mol−1. The neutral filter application triggered an increase of Ci by 2.3±1.2% which is about half that observed in younger plants. This could arise from the moderate decrease of photosynthesis that occurred under the neutral treatment compared with younger plants, thus leading to a greater CO2 consumption. Under blueless PAR, Ci decreased by 7.5±1.4% (P <0.0001; Table 1B). No significant increase in Ci was found after 45 min of blueless PAR treatment (P >0.05; Table 1B). This could be related to the stomatal reopening which was less marked in older plants.

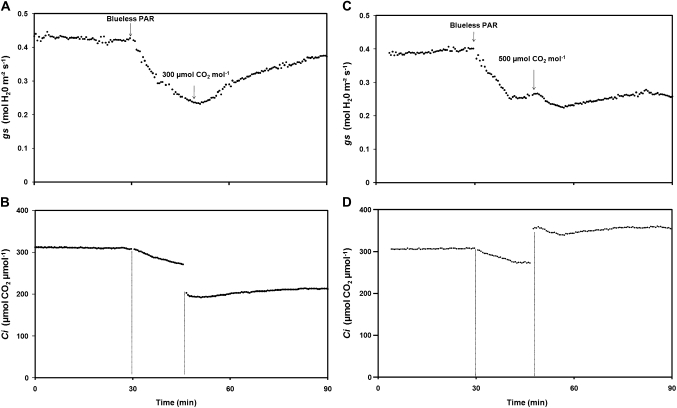

Impact of different intercellular CO2 concentrations on the blueless PAR stomatal response

The second experiment was only performed on younger plants which were submitted to different CO2 levels. Typical gs and Ci responses to each treatment are shown in Fig. 5. Under neutral treatment, mean gs values were 0.38–0.43 mol H2O m−2 s−1. Then the blueless PAR filter was applied and gs and Ci responded as described previously (Fig. 3A). Stomatal closure rates of 0.29% s−1 (Table 3) were in agreement with those calculated in the first experiment. CO2 air concentration changes were then imposed when gs values were minimal, i.e. 19 min after the beginning of the blueless PAR treatment, a value that was rounded up to 20 min. gs immediately responded to a decrease of the CO2 air concentration (Fig. 5A). In fact, decreasing the ambient CO2 concentration from 400 μmol CO2 mol−1 to 300 μmol CO2 mol−1 triggered a strong stomatal reopening. Then gs stabilized at levels close to those found under the neutral treatment, thus leading Ci to remain at sufficient levels in spite of the decrease by 100 μmol CO2 mol−1 of the CO2 air concentration (Fig. 5B). Nevertheless, the stomatal reopening (ko; Table 3) appeared to be slightly slower than that previously seen 20 min after the blue light reduction: 0.06% s−1 instead of 0.10% s−1 in these younger plants.

Fig. 5.

Typical stomatal conductance (gs, up) and intercellular concentration of CO2 (Ci, down) response to blueless PAR and to CO2 air concentration. Leaves were put into the gas exchange chamber straight under the neutral treatment (PAR=322 μmol m−2 s−1, Blue=61 μmol m−2 s−1) with 400 μmol CO2 mol−1. The blueless PAR treatment (PAR=277 μmol m−2 s−1, Blue=1.80 μmol m−2 s−1) was then applied, triggering a stomatal closure. (A, B) CO2 air concentration was set to 300 μmol CO2 mol−1 20 min after the blueless PAR treatment beginning. (C, D) CO2 air concentration was set to 500 μmol CO2 mol−1 20 min after the blueless PAR treatment began.

Table 3.

Different CO2 air concentration effects on the rate of stomatal opening (ko)

| Younger plants | |||

| CO2 air concentration (μmol CO2 mol−1) | 400 | 400 to 300 | 400 to 500 |

| Parameter (% s−1) | kc | ko | kc |

| Mean value | 0.29 | 0.06 | 0.46 |

| SD | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.03 |

CO2 concentration changes were performed when the blueless PAR effect on stomatal conductance was maximal (B–). kc and ko values were calculated after fitting of two non linear functions (cf. statistical analysis). n=2 for each treatment (300 and 500 μmol CO2 mol-1).

By contrast, an increase of CO2 air concentration from 400 μmol CO2 mol−1 to 500 μmol CO2 mol−1 (according to the same protocol) triggered an opposite response (Fig. 5C, D). In that case, gs further decreased in response to a higher CO2 air concentration down to a value equivalent to 63.0±1.6% of that measured under the neutral filter without CO2 modification. This step of stomatal closure was rapidly conducted with kc=0.46% s−1.

Discussion

Blueless PAR stomatal response and Ci involvement

The objective of this study was to quantify blueless PAR effects on stomatal conductance (gs) and its consequences on transpiration (Tr) in tall fescue. Despite the variability of gs absolute values (Fig. 4A), all leaves belonging to plants at the same stage exhibited similar gs (data not shown). This demonstrates that gs responses to the light treatment were similar and proportional to the initial conductance level as observed by Karlsson (1986). Further, a sudden blue light reduction from 60.96 μmol m−2 s−1 to 1.80 μmol m−2 s−1 triggered a transient drastic and instantaneous decrease of gs whatever the plant stage. Similar results have been reported by Zeiger (1984) in Xanthium strumarium and by Karlsson and Assmann (1990) in Hedera helix when blue light was switched off from a red light background. Stomatal responses under strongly or totally reduced blue light are poorly documented in comparison to the large body of literature dealing with the addition of blue light by pulses or continuous lighting (Iino et al., 1985; Karlsson, 1986; Zeiger et al., 1987; Assmann and Grantz, 1990). In these studies, an inverse kinetic, i.e. stomatal opening, was observed whatever the plant species and the range of blue light fluence rates tested, from 250 μmol m−2 s−1 (Iino et al., 1985) to 1.1 μmol m−2 s−1 (Karlsson, 1986). Moreover, blue light was generally superimposed on red light backgrounds and/or in plants exhibiting particular developments in relation to their light environment (e.g. plants kept in darkness or hypocotyls). However, both blue and red wavelengths play an important role in photomorphogenesis and photosynthesis, so that, in these studies, PAR-dependent responses of stomata to blue light could not be excluded (McCree, 1972; Zeiger, 1984).

In order to separate PAR-dependent and photomorphogenic responses, light transmission filters were used that ensure an equivalent photosynthetic efficiency and exhibit similar properties for the phytochrome photoequilibrium (ϕc) and the R:FR ratio (ζ), as reported in Fig. 2A. As expected, steady-state levels of assimilation rate measured under the blueless PAR condition were close to those found under the neutral treatment (Fig. 4). On the other hand, cutting the supply of blue light strongly reduced gs that, surprisingly, did not stay at its minimal values but reached a steady-state at an intermediate level (Fig. 4A), particularly in younger plants. It was hypothesized that this stomatal reopening may be in relation to the constant photosynthetic demand related to the electron flow that occurred under the blueless PAR treatment. This treatment triggered a rapid stomatal closure which reduced the CO2 uptake and thus Ci (Fig. 5). Once CO2 stocks are consumed by photosynthesis, one or more signals may therefore induce stomatal reopening thus allowing the leaf to maintain a constant assimilation rate. However, gs did not regain its initial levels observed under the neutral filter but reached a new stomatal equilibrium which may be balanced between the blueless PAR signal (closure) and the photosynthetic demand through Ci (opening). The results from the Ci level manipulation confirmed the potential implication of Ci in the stomatal behaviour in response to blueless PAR, in particular, for stomatal reopening. In fact, a reduction of external CO2 concentration during the blueless PAR treatment triggered a strong stomatal reopening thus allowing leaves to maintain sufficient Ci to ensure constant photosynthesis (Fig. 5B). By contrast, an increase of external CO2 concentration triggered an additional stomatal closure that enhanced the blueless PAR effect as Ci was no longer limiting (Fig. 5D). These results strengthened the notion of CO2 stomatal control as reported by Morison and Gifford (1983), which would modulate the blue light response of stomata (Lasceve et al., 1993). Further, the steady-state response of gs to Ci could be controlled by photosynthetic electron transport which is therefore sensitive to the balance between the light and dark reactions of photosynthesis (Messinger et al., 2006). Moreover, the amplitude of stomatal responses involves signal exchanges, other than Ci, between the mesophyll and epidermal cells, including guard cells (Mott, 2009).

Blueless PAR perception and possible molecular mechanisms

According to the literature, stomatal responses to blue light could be mediated by photoreceptors located in the stomata, for example, phototropins which are involved in photomovement. In addition, other studies have proposed zeaxanthin, located in guard cell chloroplasts, as a molecule having the dual function of a blue light and a CO2 sensor that mediates blue-light-specific stomatal opening (Srivastava and Zeiger, 1995a, b; Zeiger and Zhu, 1998; Zhu et al., 1998). Two main mechanisms have so far been identified. First, these photoreceptors may control proton extrusion (Raschke and Humble, 1973). We could therefore hypothesize that low blue light may inactivate plasma membrane H+-ATPase thus leading to stomatal closure (Shimazaki et al., 2007). More recently, Vahisalu and colleagues (2008) have also identified the SLAC1 gene, preferentially expressed in guard cells, that encodes an essential subunit for S-type anion channels. These channels seem to function as central regulators of stomatal closure induced by several factors such as light, CO2, humidity, and ABA (Keller et al., 1989; Schroeder and Hagiwara, 1989; Vahisalu et al., 2008). Thus, in our study, the low blue light conditions could, through these channels, activate an anion efflux and cause membrane depolarization (which controls K+ channels) and finally induce stomata closure.

Variability of stomatal responses to blue light

It has been shown that the magnitude of the stomatal responses to blue light could depend on environmental factors such as CO2 concentration but it could also differ between and within plant species. Indeed, Loreto et al. (2009) have shown that stomatal conductance in Platanus and Nicotiana leaves is relatively insensitive to blue light increase whereas, in general, it stimulates stomatal functioning (Zeiger, 1984). These results could be explained by the experimental conditions because blue light was changed from 0% to 80% of PAR (fixed at 300 μmol m−2 s−1) thus modifying the energy balance and photosynthetic efficiency components. Consequently, the PAR-dependent effects on stomatal conductance discussed above cannot be excluded. This hypothesis is strengthened by the fact that the apparent stability of stomatal conductance was explained by changes in mesophyll conductance, partly due to chloroplastic rearrangements.

In our study, all Festuca leaves tested exhibited similar stomatal behaviour in response to low blue light. However, leaves of more developed plants exhibited delayed and less marked gs decreases to blueless PAR. This behaviour highlights the importance of plant developmental stage on blue light stomatal sensitivity which could be explained by (i) an ‘age effect’ (Field, 1987) and/or by (ii) the important nutritive needs of more developed plants and, in particular, related to water status. Hormonal signals could therefore be involved, for example, abscisic acid (ABA) that also controls stomatal closure (Raschke, 1987; Roelfsema and Hedrich, 2005). As a consequence, variations in blue light stomatal responses, observed within a stand, could be related not necessarily to intraspecific genetic variability but to differential blue-light sensitivities, which are therefore dependent on the ontogenic development.

Blueless PAR effects at stomatal scale: a link with the blue light modulation of leaf growth through leaf transpiration?

In this study it has been demonstrated that blueless PAR triggers a rapid stomatal closure followed by a decrease of leaf transpiration by 41.1%. This is consistent with other studies although the inverse response was described, i.e. blue light pulses that triggered transpiration rate increases (Brogardh, 1975; Johnsson et al., 1976; Karlsson, 1986). Moreover, low blue light is also known to enhance leaf growth (Gautier and Varlet-Grancher, 1996) independently from PAR level (Christophe et al., 2006). Several hypotheses which are not exclusive could be put forward in order to explain this enhanced growth by low blue light levels. On the one hand, biochemical and biomolecular mechanisms could be involved, for example, blue light effects on auxin transport (Thornton and Thimann, 1967), on cell division (Munzner and Voigt, 1992) or on cell wall extension (Folta et al., 2003). On the other hand, blue light effects on leaf growth could be approached through its effects on stomatal conductance and therefore on transpiration. In fact, Martre et al. (2001) and Parrish and Wolf (1983) showed that leaf growth and leaf transpiration are highly correlated. Such a link between blue light, growth, and water status has also been made by Cosgrove and Green (1981). These authors demonstrate that an addition of blue light strongly inhibits hypocotyl growth by decreasing the yielding properties of cell walls and thus modifying cell turgor pressure.

Although the present work was conducted at the leaf scale, extrapolations at the whole plant level within a stand remain ecologically coherent as shaded zones could be localized just affecting small parts of the plant. Such work would nevertheless require further experiments at the plant scale coupled with modelling approaches in order (i) to establish the quantitative relationships between stomatal responses and actually perceived blue light and (ii) to confirm the hypothesis of a whole plant transpiration modulation by blue light and to quantify hydric pathway involvement (through stomata) in the regulation of leaf growth by blue light.

Acknowledgments

We thank Arnaud Philipponneau and Cédric Perrot for their great technical assistance and Poitou-Charentes region for financial support.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- A

rate of CO2 assimilation

- Ci

intercellular concentration of CO2

- gs

stomatal conductance

- MAR

morphogenetically active radiation

- PAR

photosynthetically active radiation

- PFD

photosynthetic flux density, ϕc, phytochromes photoequilibrium

- ζ

red/far red ratio

- Tr

transpiration rate

- VPD

vapour pressure deficit

References

- Ahmad M, Grancher N, Heil M, Black RC, Giovani B, Galland P, Lardemer D. Action spectrum for cryptochrome-dependent hypocotyl growth inhibition in arabidopsis. Plant Physiology. 2002;129:774–785. doi: 10.1104/pp.010969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assmann SM. Enhancement of the stomatal response to blue-light by red-light, reduced intercellular concentrations of CO2, and low vapor-pressure differences. Plant Physiology. 1988;87:226–231. doi: 10.1104/pp.87.1.226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assmann SM. The cellular basis of guard cell sensing of rising CO2. Plant, Cell and Environment. 1999;22:629–637. [Google Scholar]

- Assmann SM, Grantz DA. Stomatal response to humidity in sugarcane and soybean: effect of vapor-pressure difference on the kinetics of the blue-light response. Plant, Cell and Environment. 1990;13:163–169. [Google Scholar]

- Ballaré CL, Casal JJ. Light signals perceived by crop and weed plants. Field Crops Research. 2000;67:149–160. [Google Scholar]

- Ballaré CL, Scopel AL, Sanchez RA. Foraging for light: photosensory ecology and agricultural implications. Plant, Cell and Environment. 1997;20:820–825. [Google Scholar]

- Bradford KJ, Hsiao TC. Physiological responses to moderate water stress. In: Lange OL, Nobel PS, Osmond CB, Ziegler H, editors. 1982. Encyclopedia of plant physiology (new series), Vol. 12B: Physiological plant ecology. II. Water relations and carbon assimilation. Berlin: Springer-Verlag, 264–324. [Google Scholar]

- Brogardh T. Regulation of transpiration in Avena: responses to red and blue-light steps. Physiologia Plantarum. 1975;35:303–309. [Google Scholar]

- Casal JJ, Alvarez MA. Blue-light effects on the growth of Lolium multiflorum Lam. leaves under natural radiation. New Phytologist. 1988;109:41–45. [Google Scholar]

- Chelle M. Phylloclimate or the climate perceived by individual plant organs: What is it? How to model it? What for? New Phytologist. 2005;166:781–790. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2005.01350.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christie JM, Briggs WR. Blue light sensing in higher plants. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2001;276:11457–11460. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R100004200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christie JM, Reymond P, Powell GK, Bernasconi P, Raibekas AA, Liscum E, Briggs WR. Arabidopsis nph1: a flavoprotein with the properties of a photoreceptor for phototropism. Science. 1998;282:1698–1701. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5394.1698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christophe A, Moulia B, Varlet-Grancher C. Quantitative contributions of blue light and PAR to the photocontrol of plant morphogenesis in Trifolium repens (L.) Journal of Experimental Botany. 2006;57:2379–2390. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erj210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Combes D, Sinoquet H, Varlet-Grancher C. Preliminary measurement and simulation of the spatial distribution of the morphogenetically active radiation (MAR) within an isolated tree canopy. Annals of Forest Science. 2000;57:497–511. [Google Scholar]

- Cosgrove DJ, Green PB. Rapid suppression of growth by blue-light: biophysical mechanism of action. Plant Physiology. 1981;68:1447–1453. doi: 10.1104/pp.68.6.1447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Berranger C, Christophe A, Gautier H, Varlet-Grancher C. Caract.xls : un outil pour estimer les caractéristiques spectrales du rayonnement lumineux actif sur la croissance et le développement des plantes. Cahiers Techniques de l'INRA. 2005;54:21–36. [Google Scholar]

- Escobar-Gutiérrez AJ, Combes D, Rakocevic M, de Berranger C, Eprinchard-Ciesla A, Sinoquet H, Varlet-Grancher C. Functional relationships to estimate morphogenetically active radiation (MAR) from PAR and solar broadband irradiance measurements: the case of a sorghum crop. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology. 2009;149:1244–1253. [Google Scholar]

- Field CB. Leaf-age effects on stomatal conductance. In: Zeiger EF, Farquhar GD, Cowan IR, editors. Stomatal function. Vol. 17. Stanford, California, USA: Stanford University Press; 1987. pp. 367–384. [Google Scholar]

- Folta KM, Pontin MA, Karlin-Neumann G, Bottini R, Spalding EP. Genomic and physiological studies of early cryptochrome 1 action demonstrate roles for auxin and gibberellin in the control of hypocotyl growth by blue light. The Plant Journal. 2003;36:203–214. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2003.01870.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gautier H. Physiologie des stomates. Réponse à la lumière bleue des protoplastes de cellules de garde. Toulouse: Université Paul Sabatier; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Gautier H, Varlet-Grancher C. Regulation of leaf growth of grass by blue light. Physiologia Plantarum. 1996;98:424–430. [Google Scholar]

- Iino M, Ogawa T, Zeiger E. Kinetic properties of the blue-light response of stomata. Proceedings of The National Academy of Sciences, USA. 1985;82:8019–8023. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.23.8019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnsson M, Issaias S, Brogardh T, Johnsson A. Rapid, blue-light-induced transpiration response restricted to plants with grass-like stomata. Physiologia Plantarum. 1976;36:229–232. [Google Scholar]

- Jones HG. Plants and microclimate: a quantitative approach to environmental plant physiology. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson PE. Blue-light regulation of stomata in wheat seedlings. 1. Influence of red background illumination and initial conductance level. Physiologia Plantarum. 1986;66:202–206. [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson PE, Assmann SM. Rapid and specific modulation of stomatal conductance by blue-light in ivy (Hedera helix): an approach to assess the stomatal limitation of carbon assimilation. Plant Physiology. 1990;94:440–447. doi: 10.1104/pp.94.2.440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasperbauer MJ, Hunt PG. Root size and shoot root ratio as influenced by light environment of the shoot. Journal of Plant Nutrition. 1992;15:685–697. [Google Scholar]

- Keller BU, Hedrich R, Raschke K. Voltage-dependent anion channels in the plasma membrane of guard cells. Nature. 1989;341:450–453. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb07608.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lasceve G, Gautier H, Jappe J, Vavasseur A. Modulation of the blue-light response of stomata of Commelina communis by CO2. Physiologia Plantarum. 1993;88:453–459. [Google Scholar]

- Lasceve G, Leymarie J, Olney MA, Liscum E, Christie JM, Vavasseur A, Briggs WR. Arabidopsis contains at least four independent blue-light-activated signal transduction pathways. Plant Physiology. 1999;120:605–614. doi: 10.1104/pp.120.2.605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson T. Guard cell photosynthesis and stomatal function. New Phytologist. 2009;181:13–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2008.02685.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin CT. Blue light receptors and signal transduction. The Plant Cell. 2002;14:S207–S225. doi: 10.1105/tpc.000646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loreto F, Tsonev T, Centritto M. The impact of blue light on leaf mesophyll conductance. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2009;60:2283–2290. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erp112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martre P, Cochard H, Durand JL. Hydraulic architecture and water flow in growing grass tillers (Festuca arundinacea Schreb.) Plant, Cell and Environment. 2001;24:65–76. [Google Scholar]

- Mc Cree KJ. The action spectrum absorptance and quantum yield of photosynthesis in crop plants. Agricultural Meteorology. 1972;9:191–216. [Google Scholar]

- Messinger SM, Buckley TN, Mott KA. Evidence for involvement of photosynthetic processes in the stomatal response to CO2. Plant Physiology. 2006;140:771–778. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.073676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morison JIL, Gifford RM. Stomatal sensitivity to carbon-dioxide and humidity: a comparison of two C3 and two C4 grass species. Plant Physiology. 1983;71:789–796. doi: 10.1104/pp.71.4.789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mott KA. Opinion: stomatal responses to light and CO2 depend on the mesophyll. Plant, Cell and Environment. 2009;32:1479–1486. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2009.02022.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munzner P, Voigt J. Blue-light regulation of cell-division in. Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Plant Physiology. 1992;99:1370–1375. doi: 10.1104/pp.99.4.1370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parrish DJ, Wolf DD. Kinetics of tall fescue leaf elongation: responses to changes in illumination and vapor-pressure. Crop Science. 1983;23:659–663. [Google Scholar]

- Raschke K. Action of abscisic acid on guard cells. In: Zeiger E, Farquhar GD, Cowan IR, editors. Stomatal function. Vol. 11. Stanford, California, USA: Stanford University Press; 1987. pp. 253–279. [Google Scholar]

- Raschke K, Humble GD. No uptake of anions required by opening stomata of Vicia faba: guard cells release hydrogen ions. Planta. 1973;115:47–57. doi: 10.1007/BF00388604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roelfsema MRG, Hedrich R. In the light of stomatal opening: new insights into ‘the watergate’. New Phytologist. 2005;167:665–691. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2005.01460.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sager JC, Edwards JL, Klein WH. Light energy-utilization efficiency for photosynthesis. Transactions of the ASAE. 1982;25:1737–1746. [Google Scholar]

- Sager JC, Smith WO, Edwards JL, Cyr KL. Photosynthetic efficiency and phytochrome photoequilibria determination using spectral data. Transactions of the ASAE. 1988;31:1882–1889. [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder JI, Hagiwara S. Cytosolic calcium regulates ion channels in the plasma membrane of Vicia faba guard cells. Nature. 1989;338:427–430. [Google Scholar]

- Shimazaki KI, Doi M, Assmann SM, Kinoshita T. Light regulation of stomatal movement. Annual Review of Plant Biology. 2007;58:219–247. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.57.032905.105434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith H. Light quality, photoperception, and plant strategy. Annual Review of Plant Physiology. 1982;33:481–518. [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava A, Zeiger E. Guard-cell zeaxanthin tracks photosynthetically active radiation and stomatal apertures in Vicia faba leaves. Plant, Cell and Environment. 1995a;18:813–817. [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava A, Zeiger E. The inhibitor of zeaxanthin formation, dithiothreitol, inhibits blue-light-stimulated stomatal opening in. Vicia faba. Planta. 1995b;196:445–449. [Google Scholar]

- Steel RGD, Torrie JH. Principles and procedures of statistics: a biometrical approach. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Thornton RM, Thimann KV. Transient effects of light on auxin transport in the Avena coleoptile. Plant Physiology. 1967;42:247–257. doi: 10.1104/pp.42.2.247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vahisalu T, Kollist H, Wang Y-F, et al. SLAC1 is required for plant guard cell S-type anion channel function in stomatal signalling. Nature. 2008;452:487–491. doi: 10.1038/nature06608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varlet-Grancher C, Moulia B, Sinoquet H, Russell G. Crop structure and light microclimate: characterization and applications. Versailles: INRA; 1993a. [Google Scholar]

- Varlet-Grancher C, Moulia B, Sinoquet H, Russell G. Spectral modification of light within plant canopies: how to quantify its effects on the architecture of the plant stand. In: Varlet-Grancher C, Moulia B, Sinoquet H, editors. Crop structure and light microclimate. characterization and applications. Versailles: INRA; 1993b. pp. 427–451. [Google Scholar]

- Zeiger E. Blue light and stomatal function. In: Senger H, editor. Blue light effects in biological systems. Berlin, West Germany; NY, USA: Springer-Verlag; 1984. pp. 484–494. [Google Scholar]

- Zeiger E, Iino M, Shimazaki KI, Ogawa T. The blue-light response of stomata: mechanism and function. In: Zeiger E, Farquhar GD, Cowan IR, editors. Stomatal function. Vol. 9. Stanford, California, USA: Stanford University Press; 1987. pp. 209–227. [Google Scholar]

- Zeiger E, Zhu JX. Role of zeaxanthin in blue light photoreception and the modulation of light–CO2 interactions in guard cells. Journal of Experimental Botany. 1998;49:433–442. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu J, Talbott LD, Jin X, Zeiger E. The stomatal response to CO2 is linked to changes in guard cell zeaxanthin. Plant, Cell and Environment. 1998;21:813–820. [Google Scholar]