Abstract

The Cys2/His2-type zinc finger proteins have been implicated in different cellular processes involved in plant development and stress responses. Through microarray analysis, a salt-responsive zinc finger protein gene ZFP179 was identified and subsequently cloned from rice seedlings. ZFP179 encodes a 17.95 kDa protein with two C2H2-type zinc finger motifs having transcriptional activation activity. The real-time RT-PCR analysis showed that ZFP179 was highly expressed in immature spikes, and markedly induced in the seedlings by NaCl, PEG 6000, and ABA treatments. Overexpression of ZFP179 in rice increased salt tolerance and the transgenic seedlings showed hypersensitivity to exogenous ABA. The increased levels of free proline and soluble sugars were observed in transgenic plants compared to wild-type plants under salt stress. The ZFP179 transgenic rice exhibited significantly increased tolerance to oxidative stress, the reactive oxygen species (ROS)-scavenging ability, and expression levels of a number of stress-related genes, including OsDREB2A, OsP5CS OsProT, and OsLea3 under salt stress. Our studies suggest that ZFP179 plays a crucial role in the plant response to salt stress, and is useful in developing transgenic crops with enhanced tolerance to salt stress.

Keywords: Rice, salt stress, transcription factor, zinc finger protein

Introduction

High salt is one kind of environmental stress affecting plant growth and crop productivity in some areas. Plants can initiate a number of molecular, cellular, and physiological changes to respond and adapt to salt stress. During these responses and adaptations, many salt stress-related genes are induced (Moons et al., 1997; van der Krol et al., 1999; Garg et al., 2002; Sakamoto et al., 2004). Among them, transcription factors (TFs) play critical roles in plant responses to salt stress via transcriptional regulation of the downstream genes responsible for plant tolerance to salt challenges. The Cys2/His2-type zinc finger proteins constitute one of the largest transcription factor families in eukaryotes (Kubo et al., 1998). A number of stress-responsive C2H2-type zinc finger proteins have been identified in various plant species. Several studies have reported that overexpression of some C2H2-type zinc finger protein genes resulted in both the activation of some stress-related genes and enhanced tolerance to salt, dehydration, and/or cold stresses (Sakamoto et al., 2000, 2004; Kim et al., 2001; Sugano et al., 2003). However, the roles of the C2H2-type zinc finger proteins in plant stress responses are still not well known.

Rice is one of the most important crops in world, and it is also the model for molecular biological research in monocots (Cantrell and Reeves, 2002). Several genes for this type of zinc finger protein have previously been identified in rice (Huang et al., 2005a, 2007; Xu et al., 2008). ZFP245, the first C2H2-type zinc finger protein identified in rice was induced by cold and drought stresses (Huang et al., 2005a). A salt inducible zinc finger gene ZFP182 could improve salt tolerance in transgenic tobacco and rice plants (Huang et al., 2007). Overexpression of ZFP252, a salt- and drought-inducible zinc finger protein gene conferred salt and drought tolerance (Xu et al., 2008). In this study, the isolation and functional characterization of a novel salt-responsive zinc finger protein gene, ZFP179 from rice, is reported here. In addition to salt stress, ZFP179 was induced by PEG 6000, H2O2, and ABA treatments. Transgenic rice plants overexpressing ZFP179 showed enhanced salt tolerance. Furthermore, it was suggested that ZFP179-mediated salt tolerance was involved in the ABA-dependent and -independent signalling pathways and the scavenging of reactive oxygen species in plants.

Materials and methods

Plant materials and stress treatments

Rice seeds (Oryza sativa L. subsp. japonica cv. Jiucaiqing) were sterilized with 0.1% HgCl2, germinated, and grown in the incubator according to Zhou et al. (2006). The seedlings at the 3-leaf stage were transferred from the basal nutrient solution to nutrient solution containing 200 mM NaCl, 20% PEG 6000 (providing an osmotic potential of –0.54 MPa), 0.1 mM H2O2 or 0.1 mM ABA for abiotic stresses. The seedlings were sampled at 0, 1, 3, 6, 12, 24, and 48 h after each treatment and immediately stored at –80 °C. The roots, leaves, culms, immature spikes, and flowering spikes at the adult stage were also harvested.

RNA isolation and first strand DNA synthesis

Total RNA from stress-treated and untreated rice seedlings were extracted using the Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, USA) according to the manufacturer's protocol. The RNA was sequentially treated with DNaseI(Promega, USA) at 37 °C for 15 min in order to remove the remaining genomic DNA. The first strand cDNA was synthesized with 2 μg of purified total RNA using the RT-PCR system (Promega, USA) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Cloning of ZFP179

By microarray analysis (our unpublished data), it was discovered that an EST probe (probe ID: Os.10411.1.S1_at) encoding a putative zinc finger protein was induced approximately 4.5-fold by salt stress. This EST sequence was used to search the rice genome database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) and the genomic sequence containing such an EST was downloaded for gene prediction. Then ZFP179 gene was amplified from total RNA prepared from rice seedlings by RT-PCR using the primers as follows: 5′-AGAGAAGAAGCGGAGAGCAA-3′ and 5′-TACAGACGCCAATTCAAT TC-3′.

Semi-quantitative RT-PCR

The PCR conditions are as follows: 0.5 μl RT product was amplified in a 25 μl volume containing 2.5 μl of 10× PCR buffer with MgCl2, 0.5 μl of 10 mM dNTPs, 1 μl of DMSO, and 1 μl Taq polymerase (Tiangen, Beijing). The constitutively expressed rice gene, OsRAC1, was amplified as the internal control (Huang et al., 2005b). The primers for OsRAC1 are as follows: sense: 5′-GGAACTGGTATGGTCAAGGC-3′; anti-sense: 5′-AGTCTCATGGATAACCGCAG-3′.

Quantitative real-time RT-PCR

Quantitative real-time PCR was performed as previously described by Huang et al. (2008). The ZFP179 primers (5′-ATGTGAATTGAATTGGCGTCT-3′ and 5′-ATCATCACGCTCCAAAATTTA-3′) were used for quantitative PCR analysis. The 18S-rRNA primers (5′-ATGGTGGTGACGGGTGAC-3′ and 5′-CAGACACTAAAGCGCCCGGTA-3′) were used for the normalization of the quantitative PCR analysis. For quantitative RT-PCR of stress-related genes in transgenic plants, the expression of four stress-related genes was analysed, including OsDREB2A (Dai et al., 2007), OsLea3 (Moons et al., 1997), OsP5CS (Igarashi et al., 1997), and OsProT (Igarashi et al., 2000). Relative quantification relates the PCR signal of the target transcript in the transgenic plants to that of the wild-type (WT) plants.

Assay of GUS expression

Based on the rice genome information deposited in GenBank (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov), the putative promoter sequence of ZFP179 was determined. Then a fragment of approximate 1.5 kb upstream of the translation start site of ZFP179 was amplified from rice genomic DNA and cloned into pCAMBIA1301 at the sites of HindIII and BglII. The construct was subsequently transformed into rice callus via Agrobacterium-mediated transformation. For stress treatments, rice callus were kept in 150 mM NaCl solution or 20% PEG 6000. The rice callus kept in double distilled water (ddH2O) served as a control. After 12 h of treatment, rice callus was rapidly washed with ddH2O. Histochemical analysis of GUS expression was performed by incubating the rice callus in X-gluc buffer at 37 °C overnight (Couteaudier et al., 1993).

Transcriptional activation analysis in yeast cells

The transcriptional activation activity of ZFP179 was determined as previously described (Zheng et al., 2009). DNA fragments containing the whole ORF of ZFP179 was inserted into the EcoRI/SmaI sites of the pGBKT7 vector to create the pGBKT7-ZFP179 construct. According to the protocol of the manufacturer (Stratagene, USA), pGBKT7-ZFP179, the positive control pGBKT7-53+pGADT7-T, and the negative control pGBKT7 plasmids were used to transform the AH109 yeast strain. The transformed strains were streaked onto SD/–Trp or SD/–Trp–His–Ade plates, and the trans-activation activity of each protein was evaluated according to their growth status and the activity of β-galactosidase.

Generation of transgenic rice plants

The full-length ORF of ZFP179 was inserted into the plant binary vector pCAMBIA1301 to construct pCAMBIA1301-ZFP179. Then the ZFP179 gene under the control of the CaMV 35S promoter was transformed into rice (Oryza sativa L. subsp. japonica cv. Zhonghua11) by the Agrobacterium-mediated transformation method (Hiei et al., 1994).

Analysis of transgenic plants for salt and oxidative stress tolerance

To evaluate the performance of the transgenic rice plants under salt stress, the seeds of the T3 transgenic lines and the WT were germinated and grown in half-strength Murashige and Skoog (1/2MS) medium plus 0 mM, 150 mM or 250 mM NaCl for 2 weeks under a long-day photoperiod (16/8 h light/dark) (Huang et al., 2007). The shoot length and fresh weight of each ZFP179 transgenic plant or wild-type plant were measured. For survival experiments, the seeds of the T3 transgenic lines and the WT were germinated and grown in basal nutrient solution. 20-d-old rice plants were treated by 100 mM or 150 mM NaCl solution for 6 d and allowed to recover for 7 d. Seedlings which did not grow were considered as dead (Xiong and Yang, 2003). For oxidative stress, the seeds of transgenic and WT were geminated and grown on 1/2MS medium supplied with 0 mM, 30 mM or 50 mM H2O2 for 2 weeks under a long-day photoperiod. The shoot length of each ZFP179 transgenic plant and wild-type plant was measured.

Measurement of proline and soluble sugar contents

The seedlings at the four-leaf stage were used for biochemical analysis. WT and ZFP179-ox plants were transferred from the basal nutrient solution to nutrient solution containing 100 mM NaCl. After 6 d of salt treatment, the content of proline and soluble sugars in WT and transgenic lines without or with salt treatment were determined by the sulphosalicylic acid method (Troll and Lindsley, 1955) and the anthrone method (Morris, 1948).

ABA sensitivity test of transgenic plants

The T3 generation of ZFP179 transgenic plants were used in the ABA sensitivity test. For the ABA sensitivity test of transgenic rice at the seedling stage, the seeds were germinated on 1/2MS medium plates. Geminated rice plantlets at the same stage as the transgenic rice and WT control were transformed to 1/2MS medium with different concentrations of ABA (0 μM, 5 μM. and 10 μM ABA). Twelve days after growth in the greenhouse with the temperature at 26 °C, root length was measured (Lu et al., 2009).

Measurements of POD and SOD activities

One gram of frozen leaves of the T3 transgenic lines or the wild type was homogenized in 1 ml of ice-cold solution containing 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.8), 20% glycerol, and 1% PVP. The homogenates were then centrifuged at 10 000 g for 30 min. The aliquots of supernatants were used for the analysis of POD and SOD activities, as previously described by Yang et al. (2009).

In vivo detection of H2O2 deposition

In vivo H2O2 deposition was detected in the control and salt-treated leaves. In vivo infiltration of 3, 3-diaminobenzidine (DAB) was performed to detect H2O2 accumulation sites in the leaf tissues caused by salt. The protocol was followed according to Orozco-Cardenas and Ryan (1999).

Results

Cloning and sequence analysis of ZFP179

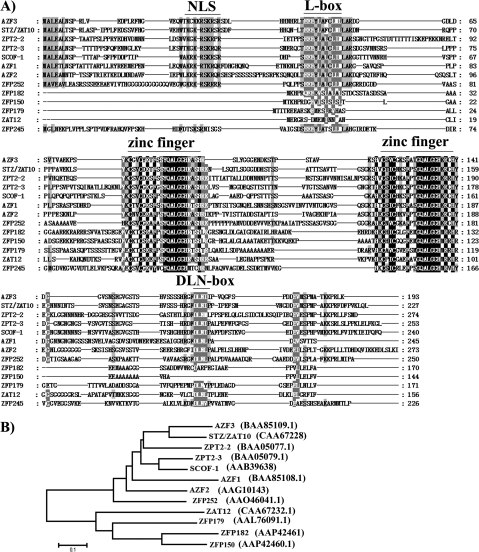

The ZFP179 gene containing a complete ORF of 516 bp was cloned by RT-PCR from total RNA prepared from rice seedlings. The predicted protein product of ZFP179 comprises 171 amino acids with the calculated molecular mass of 17.95 kDa. The ZFP179 protein contains two C2H2-type zinc fingers, with a plant-specific QALGGH motif in each zinc finger domain. A homology search against the GenBank database showed that ZFP179 was homologous to many plant C2H2-type zinc finger proteins, especially in finger domains (Fig. 1A). Like most reported C2H2-type zinc finger proteins, ZFP179 contains a DLN-box/EAR-motif with a consensus of DLN at the C-terminus, but it lacks a B-box functioning as a putative nuclear localization signal (NLS) (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1.

Multiple sequence alignment and phylogenetic tree analysis of amino acid sequences of ZFP179 with the other stress-responsive C2H2-type zinc finger proteins. (A) Multiple sequence alignment of amino acid sequences of ZFP179 with the other stress-responsive C2H2-type zinc finger proteins. Black boxes indicate the positions at which the residues are identical and grey boxes highlight the residues that are similar. AZF3 is included to show the positions in the domains of NLS, L-box, zinc finger, and DLN-box. (B) The phylogenetic tree of plant stress-responsive C2H2-type zinc finger proteins. The Neighbor–Joining tree was constructed with MEGA (version 4.1). Branch numbers represent a percentage of the bootstrap values in 1000 sampling replicates and the scale bar indicates branch lengths. The references for the amino acids sequence are Arabidopsis STZ/ZAT10, AZFs, ZAT12 (Lippuner et al., 1996; Sakamoto et al., 2000, 2004); soybean SCOF-1 (Kim et al., 2001), petunia ZPTs (van der Krol et al., 1999; Sugano et al., 2003), rice ZFP245 (Huang et al., 2005a), ZFP150 (Huang et al., 2005b), ZFP182 (Huang et al., 2007), and ZFP252 (Xu et al., 2008).

To investigate the evolutionary relationship among plant C2H2-type zinc finger proteins involved in stress responses, a phylogenetic tree was constructed using Neighbor–Joining method with the full-length amino acid sequences (Fig. 1B). The result revealed that ZFP179 was clustered with ZFP182, ZFP150, and ZAT12, whereas other stress responsive zinc finger proteins were categorized into another big branch.

Expression analysis of ZFP179

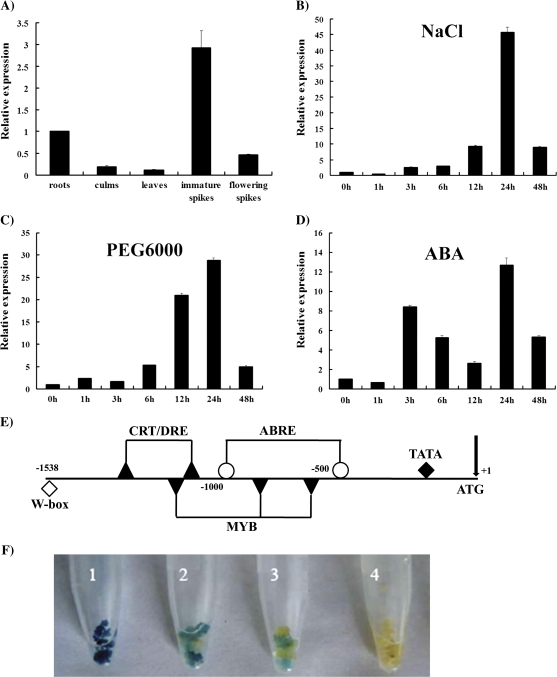

The expression profiles of ZFP179 were investigated in various rice tissues at the adult stage by real-time RT-PCR. The ZFP179 transcripts were detected in all organs tested, and the highest level was found in immature spikes and the lowest in leaves (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2.

Real-time PCR analysis for the expression patterns of ZFP179 in rice. (A) The mRNA expression of ZFP179 in various rice tissues. (B–D) Expression of ZFP179 in the seedlings under salt stress (200 mM NaCl), osmotic stress (20% PEG 6000) and exposed to 0.1 mM ABA, respectively. 18S-rRNA was used as an internal control. Data represent means and standard errors of three replicates. (E) Distribution of cis-elements in the promoter region of ZFP179. DNA sequences similar to the stress-related cis-elements are indicated as follows: open circles, ABRE; closed triangles, CRT/DRE; closed inverted triangles, MYB recognition site; open diamonds, W-box; closed diamonds, TATA. (F) ZFP179 promoter is responsive to salt stress in rice callus. GUS expressed under the control of CaMV 35S promoter (1) and ZFP179 promoter (2, 3, and 4) in rice callus. For salt and osmotic stresses, rice callus were put in 150 mM NaCl (2) and 20% PEG 6000 (3). The rice callus kept in water served as control (4).

In addition, real-time RT-PCR was performed to examine the expression pattern of ZFP179 in rice seedlings under different stress conditions. Under salt stress, the transcripts of ZFP179 began to increase 3 h after NaCl treatment and gradually accumulated up to 24 h (Fig. 2B). For PEG 6000 stress, it was observed that ZFP179 was up-regulated 1 h after treatment and was maintained constant up to 24 h (Fig. 2C). The expression of ZFP179 was also induced by an exogenous 0.1 mM ABA treatment (Fig. 2D).

The promoter sequence of ZFP179 was analysed through the MatInspector program (http://www.genomatix.de). The promoter sequence contains many putative stress-related cis-acting elements, such as ABRE, CRT/DRE, MYBRS (MYB recognition sites) and W-box (Fig. 2E). These stress-related cis-acting elements may be responsive to the stress-regulated expression of ZFP179. To examine whether the ZFP179 promoter is actually responsive to abiotic stress, ∼1.5 kb promoter region of ZFP179 was cloned to the upstream region of the β-glucuronidase (GUS) gene and then introduced into rice callus. Histochemical analysis showed strong GUS expression in rice callus under 150 mM NaCl and 20% PEG 6000, whereas no GUS expression was observed under H2O treatment (Fig. 2F).

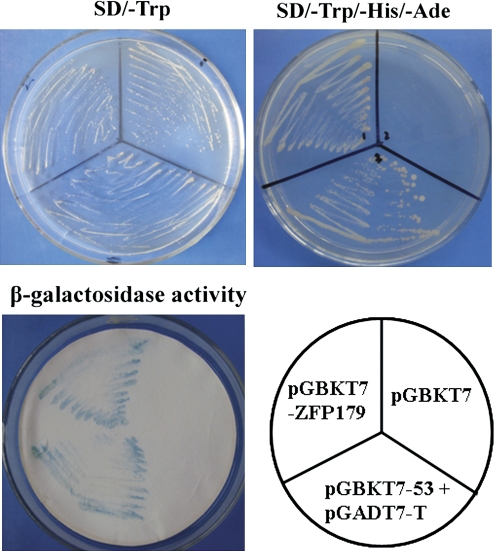

ZFP179 functions as a transcriptional activator in yeast

The transcriptional activity of ZFP179 was examined using a yeast hybrid system. A GAL4 DNA binding domain-ZFP179 fusion protein was expressed in yeast cells, which were assayed for their ability to activate transcription from the GAL4 sequence. ZFP179 promoted yeast growth in the absence of histidine and adenine, and showed β-galactosidase activity, while the vector control pGBKT7 did not (Fig. 3). The data confirmed that ZFP179 functions as a transcriptional activator in yeast.

Fig. 3.

Transcriptional activation of ZFP179 in yeast. A fusion protein of the GAL4 DNA binding domain and ZFP179 was expressed in yeast strain AH109. The vector pGBKT7 or pGBKT7-53 and pGADT7-T were expressed in yeast as a negative or a positive control. The culture solution of the transformed yeast was dropped onto SD plates with or without histidine and adenine. The plates were incubated for 3 d and subject to β-galactosidase assay. (This figure is available in colour at JXB online.)

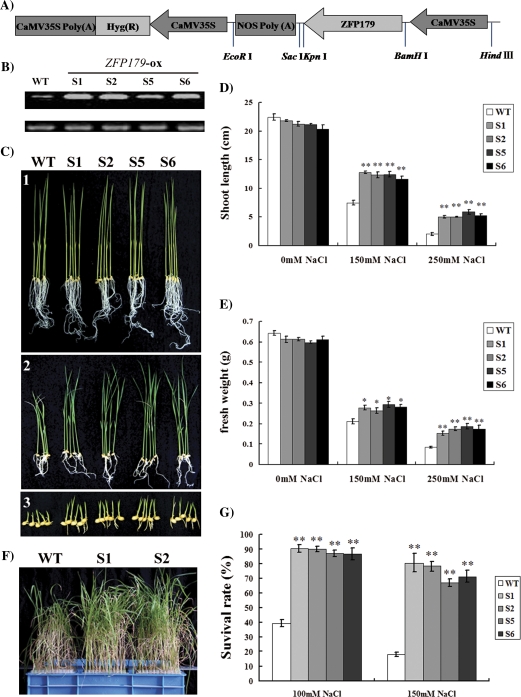

Overexpression of ZFP179 increases salt tolerance in rice

To study the physiological function of ZFP179, transgenic rice plants that overexpressed ZFP179 (ZFP179-ox plants) were generated. The positive transgenic plants were confirmed by genomic DNA PCR using hygromycin specific primers (data not shown) and RT-PCR using ZFP179 specific primers. With OsRAC1 as the reference gene, the T2 generation of the transgenic lines showed higher expression levels of ZFP179 than the WT control (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

Effect of ZFP179 overexpression on salt tolerance in transgenic rice plants. (A) The construction of transgenic vector of ZFP179. (B) The mRNA expression analysis of ZFP179 in the T2 generation of transgenic rice plants by semi-quantitative RT-PCR. (C) The seedlings of WT and transgenic lines geminated and grown on 1/2MS medium supplemented with 0 mM, 150 mM, and 250 mM NaCl (1–3). (D, E) The shoot length and fresh weight were measured. (F) Performance of WT and transgenic lines S1 and S2 after 6 d of 150 mM NaCl treatment and 7 d recovery. (G) Survival rates of WT and four transgenic lines in recovery after 100 mM or 150 mM NaCl treatment. Error bars indicate three replicates. (This figure is available in colour at JXB online.)

The effect of salt on the seedling development of the ZFP179 overexpression (ZFP179-ox) lines was investigated. Homozygous transgenic lines, S1, S2, S5, and S6 of the T3 generation were used to measure their performance under salt stress. The wild-type and ZFP179-ox transgenic rice seeds were germinated and grown on media containing 0, 150, and 250 mM NaCl for 2 weeks. It was observed that transgenic rice plants grew better than wild-type plants (Fig. 4C), as reflected by comparisons of shoot length (Fig. 4D) and fresh weight (Fig. 4E). For the survival rates assay, 20-d-old transgenic and WT seedlings cultured in liquid medium were transferred to liquid medium with 100 mM or 150 mM NaCl for 6 d and then allowed to recover under normal conditions for 7 d. Plants that could not grow any more after the recovery were considered to be dead. After recovering for 7 d, more transgenic seedlings survived than WT plants which appeared to be mostly withered (Fig. 4F). The survival rates of transgenic lines were significant higher than those of WT plants (Fig. 4G). These results indicated that overexpression of ZFP179 in rice seedlings enhanced plant tolerance to salinity.

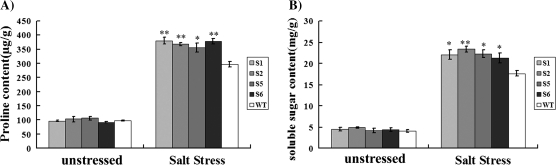

Overexpression of ZFP179 increases proline and soluble sugar contents under salt stress

Plant adaptation to environmental stresses is often associated with metabolic adjustment, such as the accumulation of proline and soluble sugars (Abraham et al., 2003). To investigate the physiological basis for the improved stress tolerance of transgenic rice, proline and soluble sugar levels were measured in the WT and ZFP179-ox plants under unstressed and salt-stressed conditions. After salt treatment for 6 d, ZFP179-ox plants accumulated an approximately 4-fold higher content of proline (Fig. 5A) and a 5-fold higher content of soluble sugars (Fig. 5B) than the plants did before salt stress, while the WT plants accumulated an approximately 3-fold higher content of proline and a 4-fold higher content of soluble sugars, respectively. The salt stress-induced increase of proline and soluble sugar content in the transgenic plants were significantly higher than those in wide-type plants, indicating that ZFP179 may regulate the accumulation of free proline and soluble sugar levels in rice seedlings under salt stress.

Fig. 5.

The contents of free proline (A) and soluble sugars (B) in the ZFP179-ox and WT rice under 100 mM NaCl stress conditions.

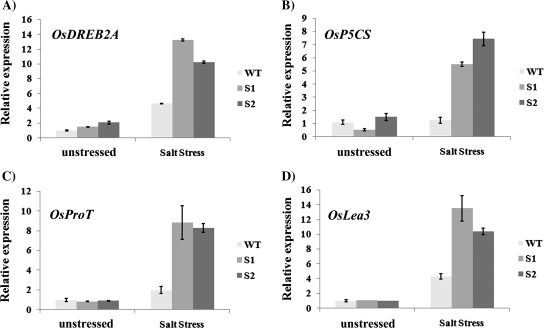

Expression of stress-related genes in ZFP179 transgenic rice plants

To elucidate the possible role of ZFP179 in response to salt stress further, the expression of several stress-related genes in ZFP179 transgenic lines and WT were analysed, including OsDREB2A encoding a DREB-type transcription factor, OsP5CS encoding pyrroline-5-carboxylate synthetase, OsProT encoding a proline transporter, and OsLea3 encoding a group 3 late embryogenesis abundant protein. Expression levels of all the genes analysed were induced by salt treatment both in WT control and transgenic rice plants (Fig. 6). Under salt treatment, the expression levels of all four stress-related genes in ZFP179-ox plants were increased more than those in WT plants. It is suggested that ZFP179 might be one upstream regulator of these genes and play an important role in regulating the stress-responsive genes.

Fig. 6.

Expression of stress-related genes in ZFP179-ox and WT rice. Total RNA was extracted from the rice seedlings at the four-leaf stage grown under control and salt treatments. (A–D) The transcript levels of OsDREB2A, OsP5CS, OsProT, and OsLea3 were measured by quantitative real-time PCR under unstressed conditions or 150 mM NaCl for 24 h, respectively. 18S-rRNA was used as an internal control. Data represent means and standard errors of three replicates.

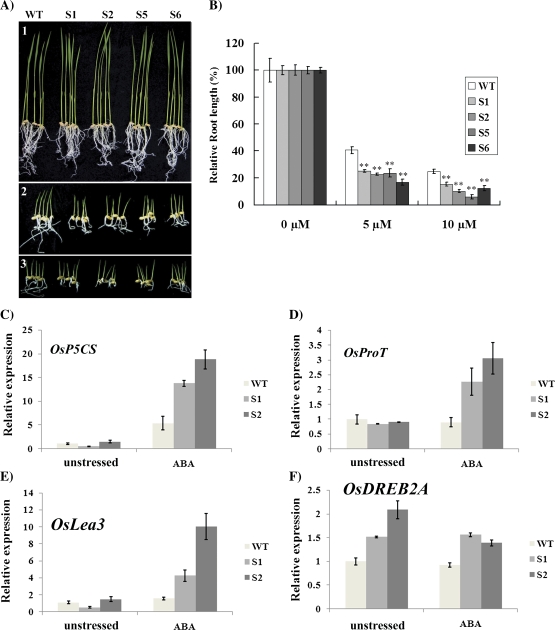

Overexpression of ZFP179 makes seedlings hypersensitive to ABA

The effect of ABA on seedling development of the ZFP179 overexpression (ZFP179-ox) lines was investigated. There were no significant differences between WT and the transgenic rice plants when shoot length and root length were compared in medium without ABA. However, as shown in Fig. 7A, the root length of WT growing on medium with 5 μM ABA was reduced to 40.6% of the control growing on medium without ABA, while root lengths of transgenic rice lines were arrested to 25.19%, 22.83%, 23.70%, and 16.91%, respectively. When the ABA concentration in the medium was elevated to 10 μM, the root lengths of WT rice were reduced to 24.81% of the control, while the root lengths of transgenic plants were arrested to 15.26%, 10.23%, 5.92%, and 12.5% of the control (Fig. 7B). The severity of ABA-induced growth arrest of root length was more significant in the transgenic lines than in the WT control (t test, P <0.01). The results indicated that ZFP179 increases the sensitivity of rice to ABA treatment. It was also found that the expression levels of OsP5CS, OsProT, and OsLea3 in ZFP179-ox plants had increased more compared with WT plants (Fig. 7C–E),while there was no significant difference between WT and transgenic rice for the expression level of OsDREB2A under ABA treatment (Fig. 7F).

Fig. 7.

Seedling development of ZFP179-ox transgenic rice plants under ABA treatment. (A) The WT control and transgenic lines were grown under 0 μM, 5 μM, and 10 μM ABA (1–3). (B) The relative root length of each WT and transgenic lines was measured and the error bars are based on three replicates. The values with significant difference according to the t test are indicated by asterisks (**, P ≤0.01). (C–F) The transcript levels of OsP5CS, OsProT OsLea3, and OsDREB2A were measured by quantitative real-time PCR under unstressed conditions and 0.1 mM ABA for 24 h, respectively. 18S-rRNA was used as an internal control. Data represent means and standard errors of three replicates. (This figure is available in colour at JXB online.)

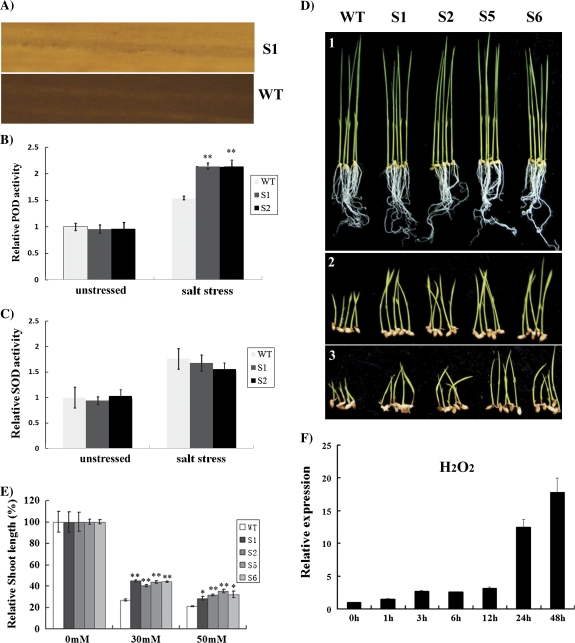

ZFP179 enhances the ROS scavenging ability and the tolerance to oxidative stress

H2O2 production was first visualized by a histochemical method with 3, 3-diaminobenzidine (DAB). After the 15-d-old rice seedlings of transgenic and WT plants were immersed in 150 mM NaCl for 2 d, the presence of H2O2 could be detected in all the experimental plants. Figure 8A showed that the generation of H2O2 was much less in ZFP179-ox than in WT plants. Abiotic stresses may increase the level of reactive oxygen species (ROS), and the accumulation of ROS is toxic to plant cells. To analyse whether the ROS scavenging enzymes contribute to the plant's tolerance to abiotic stress, the enzyme activity assays for peroxidase (POD) and superoxide dismutase (SOD) were conducted under unstressed and salt conditions. It was found that the POD activities of two transgenic lines were more increased compared with those in WT plants under salt stress (Fig. 8B). There was no significant difference of SOD activities between the two transgenic lines and WT plants under unstressed or salt conditions (Fig. 8C). Further, in the culture media containing 30 mM or 50 mM hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), ZFP179-ox plants showed more resistance to H2O2 than the WT plant (Fig. 8D). The relative shoot lengths of ZFP179-ox plants were significant higher than WT plants (Fig. 8E). This indicated that ZFP179 might mediate in the rice response to oxidative stress caused by H2O2. Furthermore, it was observed that the transcript level of ZFP179 was induced after 1 h treatment of H2O2 which was maintained constant for up to 48 h (Fig. 8F).

Fig. 8.

ZFP179 decreases H2O2 production and enhances POD activity and oxidative stress tolerance. (A) In vivo detection of H2O2 accumulation in plants exposed to salt stress via the DAB method. (B, C) The POD and SOD activities of transgenic plants under salt and unstressed conditions. (D, E) The seedlings and corresponding relative shoot length of WT and ZFP179-ox lines were germinated and grown on 1/2MS plus 0 mM, 30 mM, and 50 mM H2O2 for 14 d, respectively. Error bars are based on three replicates. (F) Expression of ZFP179 in the seedling under oxidative stress (H2O2).

Discussion

ZFP179 contains two typical C2H2 zinc finger domains and a DLN-box/EAR-motif located at its C-terminus. Several zinc finger proteins containing a DLN-box/EAR-motif have exhibited transcription repressive activities by transient analysis in plants, such as petunia ZPT2-3 (Sugano et al., 2003) and Arabidopsis STZ/ZAT10 (Sakamoto et al., 2004). ZFP179 showed transcriptional activation activity in yeast cells although it contains a DLN-box/EAR-motif. Similarly, the zinc finger proteins ThZF1 from salt cress (Xu et al., 2007) and CaZF from chickpea (Jain et al., 2009), both containing the DLN-box/EAR-motif, exhibited their transcriptional activation activities. Altogether, it is suggested that some unknown domains may affect the transcriptional activity of C2H2-type zinc finger proteins.

Several stress-related cis-acting elements, including ABREs, MYBREs, W-boxes, and CRT/DRE were found in the 1.5 kb promoter region of ZFP179 (Fig. 2G). These cis-acting elements and their corresponding transcription factors are important for ABA signalling or abiotic stress responses in plants (Abe et al., 1997; Yamaguchi-Shinozaki and Shinozaki, 2005, 2006; Nakashima et al., 2007). These cis-acting elements may be responsive for the stress-regulated expression of ZFP179. In addition to responses to abiotic stress, it was found that ZFP179 was also highly expressed in immature spikes, indicating that ZFP179 might also play a role in spike growth or development in rice.

In response to abiotic stress, many plants can accumulate compatible osmolytes, such as free proline and soluble sugars, to protect their subcellular structures from damage by adjusting the intracellular osmotic potential (Garg et al., 2002; Armengaud et al., 2004). To address the possible mechanism of the enhanced stress tolerance of the ZFP179-ox plants, the contents of proline and soluble sugars were ascertained in transgenic plants under normal growth and stress conditions. The data showed that ZFP179-ox plants accumulated more free proline and soluble sugars than WT under salt-stress conditions (Fig. 5). Quantitative real-time PCR results also showed that the proline synthetase gene (OsP5CS) and the proline transport gene (OsProT) had significantly higher expression levels in the ZFP179-ox lines than in the WT (Fig. 6B, C). However, overexpression of ZFP179 could not enhance the expression of stress-related genes, including OsP5CS, OsProT, and OsLea3 in transgenic rice plants under unstressed conditions. One possible explanation is that ZFP179 may mediate the activation of such stress-related genes accompanied by other stress-responsive regulators.

ABA plays a critical role in the osmotic stress response in plants. Under osmotic stress, the plant always initiates the ABA signalling transduction pathway to activate the expression of stress defence genes (Chinnusamy et al., 2004). Overexpression of some transcription factor genes, such as OsABI5 and OsZIP72 made the transgenic plants hypersensitive to exogenous ABA and resulted in abiotic stress tolerance (Zou et al., 2008; Lu et al., 2009). Our data showed that ZFP179-ox plants significantly increased plant sensitivity to exogenous ABA (Fig. 7), indicating that ZFP179 might play a role in the ABA signal transduction pathway during the stress responses. It was shown that the OsP5CS, OsProT, and OsLea3 genes were all more highly expressed in ZFP179-ox plants compared with WT plants under ABA treatment, suggesting that the regulation of these stress defence genes by ZFP179 under salt stress might be ABA dependent. Further, it was found that OsDREB2A encoding a DREB protein in rice was responsive to ZFP179 overexpression (Fig. 6A), suggesting that ZFP179 might be an upstream regulator of OsDREB2A under salt stress. Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that OsDREB2A was gradually induced within 24 h after salt treatment, but not induced by ABA (Dubouzet et al., 2003). Under ABA treatment, it was found that ZFP179-ox plants did not promote a higher expression of OsDREB2A compared with WT plants (Fig. 7F). Thus, OsDREB2A-regulated expression of some stress defence genes may be controlled by ZFP179 in an ABA-independent manner. Consistently, the Arabidopsis DREB2A has been shown to have a role in the regulation of some stress defence genes in plant responsiveness to drought and salt stresses through an ABA-independent signal transduction pathway (Liu et al., 1998). Altogether, it is suggested that ZFP179 may play important roles in response to salt stress both in ABA-dependent and -independent pathways.

Many stress conditions lead to the accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) which are toxic to plant cells. ZFP179 may enhance ROS scavenging activity to reduce the accumulation of H2O2 induced by salt stress. In line with this idea, our data showed that the expression of ZFP179 was also induced by H2O2 treatment and overexpression of ZFP179 enhanced oxidation tolerance (Fig. 8), suggesting that ZFP179 might activate the antioxidant system in rice. Peroxidase (POD) is a very important ROS scavenging enzyme in plants. Our data showed that ZFP179 increased POD activity in rice seedlings under salt stress, however, SOD activity was not enhanced by ZFP179, indicating that ZFP179 might specifically regulate the activities of some ROS scavenging enzymes, such as POD. To understand further the interaction of ZFP179 and the ROS scavenging system, the activities of more ROS scavenging enzymes need to be measured.

In conclusion, when plants suffer from salt stress, ZFP179 might either enhance the expression of stress-defence genes, such as OsP5CS, OsProT, and OsLEA3, and the subsequent accumulation of free proline, soluble sugars, and Group 3 late embryogenesis abundant proteins through an ABA-dependent manner, or activate the expression of OsDREB2A through an ABA-independent pathway. Both types of response may increase the salt tolerance of plants. In addition, ZFP179 may enhance ROS-scavenging activity to remove the toxic ROS in plants induced by salt stress.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Program for New Century Excellent Talents in University (No. NCET-08-0795), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos 30971556, 30971758), the Research Fund for the Doctoral Program of Higher Education (No. 200803070036), a project from the State Key Laboratory of Crop Genetics and Germplasm Enhancement, the Jiangsu Enhancement Project for Graduate Students, and the Changjiang Scholars and Innovative Research Team in University (PCSIRT).

Glossary

Abbreviations

- ABA

abscisic acid

- DREB

dehydration responsive element binding protein

- ABRE

abscisic acid responsive element

- CBF

C-repeat binding factor

- P5CS

pyrroline-5-carboxylate synthetase

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- POD

peroxidase

- SOD

superoxide dismutase

References

- Abe H, Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K, Urao T, Iwasaki T, Hosokawa D, Shinozaki K. Role of Arabidopsis MYC and MYB homologs in drought- and abscisic acid-regulated gene expression. The Plant Cell. 1997;9:1859–1868. doi: 10.1105/tpc.9.10.1859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abraham E, Rigo G, Szekely G, Nagy R, Koncz C, Szabados L. Light-dependent induction of proline biosynthesis by abscisic acid and salt stress is inhibited by brassinosteroid in Arabidopsis. Plant Molecular Biology. 2003;51:363–372. doi: 10.1023/a:1022043000516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armengaud P, Thiery L, Buhot N, Grenier-De March G, Savoure A. Transcriptional regulation of proline biosynthesis in Medicago truncatula reveals developmental and environmental specific features. Physiologia Plantarum. 2004;120:442–450. doi: 10.1111/j.0031-9317.2004.00251.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantrell RP, Reeves TG. The rice genome. The cereal of the world's poor takes center stage. Science. 2002;296:53. doi: 10.1126/science.1070721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinnusamy V, Schumaker K, Zhu JK. Molecular genetic perspectives on cross-talk and specificity in abiotic stress signaling in plants. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2004;55:225–236. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erh005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couteaudier Y, Daboussi MJ, Eparvier A, Langin T, Orcival J. The GUS gene fusion system (Escherichia coli β-D-glucuronidase gene), a useful tool in studies of root colonization by Fusarium oxysporum. Applied Environmental Microbiology. 1993;59:1767–1773. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.6.1767-1773.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai X, Xu Y, Ma Q, Xu W, Wang T, Xue Y, Chong K. Overexpression of an R1R2R3 MYB gene, OsMYB3R-2, increases tolerance to freezing, drought, and salt stress in transgenic Arabidopsis. Plant Physiology. 2007;143:1739–1751. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.094532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubouzet JG, Sakuma Y, Ito Y, Kasuga M, Dubouzet EG, Miura S, Seki M, Shinozaki K, Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K. OsDREB genes in rice, Oryza sativa L., encode transcription activators that function in drought-, high-salt- and cold-responsive gene expression. The Plant Journal. 2003;33:751–763. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2003.01661.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garg AK, Kim JK, Owens TG, Ranwala AP, Choi YD, Kochian LV, Wu RJ. Trehalose accumulation in rice plants confers high tolerance levels to different abiotic stresses. Procedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA. 2002;99:15898–15903. doi: 10.1073/pnas.252637799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiei Y, Ohta S, Komari T, Kumashiro T. Efficient transformation of rice (Oryza sativa L.) mediated by Agrobacterium and sequence analysis of the boundaries of the T-DNA. The Plant Journal. 1994;6:271–282. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1994.6020271.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J, Wang J, Zhang H. Rice ZFP15 gene encoding for a novel C2H2-type zinc finger protein lacking DLN box, is regulated by spike development but not by abiotic stresses. Molecular Biology Reports. 2005b;32:177–183. doi: 10.1007/s11033-005-2338-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J, Wang JF, Wang QH, Zhang HS. Identification of a rice zinc finger protein whose expression is transiently induced by drought, cold but not by salinity and abscisic acid. DNA Sequence. 2005a;16:130–136. doi: 10.1080/10425170500061590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J, Wang MM, Jiang Y, Bao YM, Huang X, Sun H, Xu DQ, Lan HX, Zhang HS. Expression analysis of rice A20/AN1-type zinc finger genes and characterization of ZFP177 that contributes to temperature stress tolerance. Gene. 2008;420:135–144. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2008.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J, Yang X, Wang MM, Tang HJ, Ding LY, Shen Y, Zhang HS. A novel rice C2H2-type zinc finger protein lacking DLN-box/EAR-motif plays a role in salt tolerance. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2007;1769:220–227. doi: 10.1016/j.bbaexp.2007.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Igarashi Y, Yoshiba Y, Sanada Y, Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K, Wada K, Shinozaki K. Characterization of the gene for delta1-pyrroline-5-carboxylate synthetase and correlation between the expression of the gene and salt tolerance in Oryza sativa L. Plant Molecular Biology. 1997;33:857–865. doi: 10.1023/a:1005702408601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Igarashi Y, Yoshiba Y, Takeshita T, Nomura S, Otomo J, Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K, Shinozaki K. Molecular cloning and characterization of a cDNA encoding proline transporter in rice. Plant and Cell Physiology. 2000;41:750–756. doi: 10.1093/pcp/41.6.750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain D, Roy N, Chattopadhyay D. CaZF, a plant transcription factor functions through and parallel to HOG and calcineurin pathways in Saccharomyces cerevisiae to provide osmotolerance. PLoS One. 2009;4 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005154. e5154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JC, Lee SH, Cheong YH, et al. A novel cold-inducible zinc finger protein from soybean, SCOF-1, enhances cold tolerance in transgenic plants. The Plant Journal. 2001;25:247–259. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2001.00947.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubo K, Sakamoto A, Kobayashi A, Rybka Z, Kanno Y, Nakagawa H, Takatsuji H. Cys2/His2 zinc-finger protein family of petunia: evolution and general mechanism of target-sequence recognition. Nucleic Acids Research. 1998;26:608–615. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.2.608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lippuner V, Cyert MS, Gasser CS. Two classes of plant cDNA clones differentially complement yeast calcineurin mutants and increase salt tolerance of wild-type yeast. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1996;271:12859–12866. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.22.12859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu G, Gao C, Zheng X, Han B. Identification of OsbZIP72 as a positive regulator of ABA response and drought tolerance in rice. Planta. 2009;229:605–615. doi: 10.1007/s00425-008-0857-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moons A, De Keyser A, Van Montagu M. A group 3 LEA cDNA of rice, responsive to abscisic acid, but not to jasmonic acid, shows variety-specific differences in salt stress response. Gene. 1997;191:197–204. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(97)00059-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris DL. Quantitative determination of carbohydrates with Dreywood's anthrone reagent. Science. 1948;107:254–255. doi: 10.1126/science.107.2775.254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakashima K, Tran LS, Van Nguyen D, Fujita M, Maruyama K, Todaka D, Ito Y, Hayashi N, Shinozaki K, Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K. Functional analysis of a NAC-type transcription factor OsNAC6 involved in abiotic and biotic stress-responsive gene expression in rice. The Plant Journal. 2007;51:617–630. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03168.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orozco-Cardenas M, Ryan CA. Hydrogen peroxide is generated systemically in plant leaves by wounding and systemin via the octadecanoid pathway. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciwences, USA. 1999;96:6553–6557. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.11.6553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakamoto H, Araki T, Meshi T, Iwabuchi M. Expression of a subset of the Arabidopsis Cys(2)/His(2)-type zinc-finger protein gene family under water stress. Gene. 2000;248:23–32. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(00)00133-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakamoto H, Maruyama K, Sakuma Y, Meshi T, Iwabuchi M, Shinozaki K, Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K. Arabidopsis Cys2/His2-type zinc-finger proteins function as transcription repressors under drought, cold, and high-salinity stress conditions. Plant Physiology. 2004;136:2734–2746. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.046599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugano S, Kaminaka H, Rybka Z, Catala R, Salinas J, Matsui K, Ohme-Takagi M, Takatsuji H. Stress-responsive zinc finger gene ZPT2-3 plays a role in drought tolerance in petunia. The Plant Journal. 2003;36:830–841. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2003.01924.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troll W, Lindsley J. A photometric method for the determination of proline. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1955;215:655–660. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Krol AR, van Poecke RM, Vorst OF, Voogt C, van Leeuwen W, Borst-Vrensen TW, Takatsuji H, van Der Plas LH. Developmental and wound-, cold-, desiccation-, ultraviolet-B-stress-induced modulations in the expression of the petunia zinc finger transcription factor gene ZPT2-2. Plant Physiology. 1999;121:1153–1162. doi: 10.1104/pp.121.4.1153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong L, Yang Y. Disease resistance and abiotic stress tolerance in rice are inversely modulated by an abscisic acid-inducible mitogen-activated protein kinase. The Plant Cell. 2003;15:745–759. doi: 10.1105/tpc.008714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu DQ, Huang J, Guo SQ, Yang X, Bao YM, Tang HJ, Zhang HS. Overexpression of a TFIIIA-type zinc finger protein gene ZFP252 enhances drought and salt tolerance in rice (Oryza sativa L.) FEBS Letters. 2008;582:1037–1043. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.02.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu S, Wang X, Chen J. Zinc finger protein 1 (ThZF1) from salt cress (Thellungiella halophila) is a Cys-2/His-2-type transcription factor involved in drought and salt stress. Plant Cell Reports. 2007;26:497–506. doi: 10.1007/s00299-006-0248-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K, Shinozaki K. Organization of cis-acting regulatory elements in osmotic- and cold-stress-responsive promoters. Trends in Plant Science. 2005;10:88–94. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2004.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K, Shinozaki K. Transcriptional regulatory networks in cellular responses and tolerance to dehydration and cold stresses. Annual Review of Plant Biology. 2006;57:781–803. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.57.032905.105444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z, Wu Y, Li Y, Ling HQ, Chu C. OsMT1a, a type 1 metallothionein, plays the pivotal role in zinc homeostasis and drought tolerance in rice. Plant Molecular Biology. 2009;70:219–229. doi: 10.1007/s11103-009-9466-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng XN, Chen B, Lu GJ, Han B. Overexpression of a NAC transcription factor enhances rice drought and salt tolerance. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2009;379:985–989. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.12.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou GA, Jiang Y, Yang Q, Wang JF, Huang J, Zhang HS. Isolation and characterization of a new Na+/H+antiporter gene OsNHA1 from rice (Oryza sativa L.) DNA Sequence. 2006;17:24–30. doi: 10.1080/10425170500224263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou M, Guan Y, Ren H, Zhang F, Chen F. A bZIP transcription factor, OsABI5, is involved in rice fertility and stress tolerance. Plant Molecular Biology. 2008;66:675–683. doi: 10.1007/s11103-008-9298-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]