Abstract

We use systems thinking to develop a strategic framework for analyzing the tobacco problem and we suggest solutions. Humans are vulnerable to nicotine addiction, and the most marketable form of nicotine delivery is the most harmful. A tobacco use management system has evolved out of governments’ attempts to regulate tobacco marketing and use and to support services that provide information about tobacco's harms and discourage its use. Our analysis identified 5 systemic problems that constrain progress toward the elimination of tobacco-related harm. We argue that this goal would be more readily achieved if the regulatory subsystem had dynamic power to regulate tobacco products and the tobacco industry as well as a responsive process for resourcing tobacco use control activities.

There have been numerous recent calls for a more systematic application of systems thinking to public health issues.1,2 Work to date has focused on the utility of systems modeling in general3 and of specific subclasses of systems approaches (e.g., organizational network analysis4,5). We use a social–ecology, or open systems, framework6 to analyze both the dynamics and the outcomes of tobacco control initiatives and to identify problems and possible solutions.

Aggregate tobacco use is the outcome of complex interactions between forces aimed at increasing use and those aimed at decreasing use, the balance of which can be influenced by governments’ policy frameworks. The primary relationship is between the industry and the smoker. This relationship has changed from one in which smokers were driving demand and the industry was essentially meeting that demand (Figure 1, path 1) to one in which modern marketing influences smokers and potential smokers to increase demand (Figure 1, path 2).

FIGURE 1.

Forces involved in the dynamics of tobacco use management.

As the problems caused by tobacco use mounted, governments came under pressure to intervene. Initial interventions were inadequate—tobacco use was too prevalent, and the industry was too powerful for strong action to be contemplated—thus, elimination of tobacco use became a long-term goal rather than an immediate policy. Governments gradually implemented rules to govern the industry (Figure 1, path 3), such as restrictions on advertising and other forms of promotion. They also established or supported the establishment of programs (Figure 1, path 4) to provide public information about cessation assistance and the harms of tobacco use (Figure 1, path 5). They have also acted more directly on smokers via taxes and laws to restrict where they can smoke (Figure 1, path 6). To date, these actions of governments have been largely imposed on the system, with changes negotiated between multiple government departments and ministries (e.g., economic, health, environment, and trade).

The existence of dedicated tobacco control legislation and the establishment of programs to constrain tobacco use make it useful to extend the open systems perspective and characterize tobacco control as a tobacco use management system. A management system has a set of dynamically interrelated elements and a framework of processes and structures to constrain its activities toward a goal—in this case, changing the level of tobacco use or the level of harm caused by its use. We position central government outside the tobacco use management system, because it acts only intermittently on it.

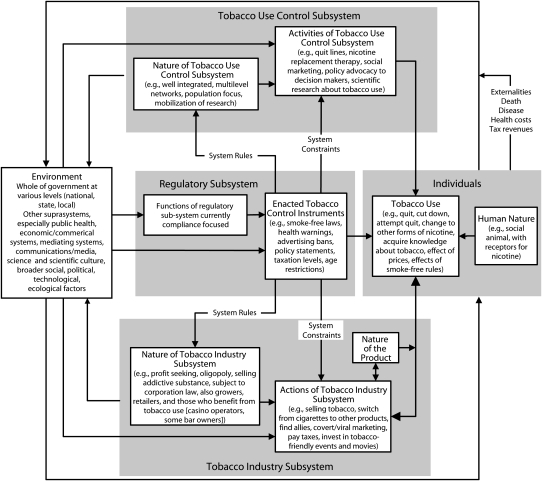

Figure 2 offers a more comprehensive description of how the tobacco use management system operates. The goal is not to build a complete model but to identify the smallest set of elements that need to be considered to understand how the system operates (each subsystem can be further elaborated as the need arises). The outputs (actions or behavior) of each subsystem are driven or motivated by 3 kinds of processes: (1) influences from the broader environment, (2) influences from the outputs of the other subsystems, and (3) influences from processes intrinsic to the nature of each subsystem, which can both motivate action independently and moderate the effects of inputs. These intrinsic capacities are currently determined largely from outside the tobacco use management system.

FIGURE 2.

Framework for investigating the social ecology of tobacco use.

We use an analysis of the structure of the tobacco use management system to identify problems that currently make the management of tobacco problematic. Two of the problems are fundamental, being associated with factors that are not amenable to change and, therefore, have to be managed continuously. The remaining 5 are systemic and are, at least in principle, amenable to resolution, although some of these 5 may need to be accepted as ongoing and thus managed instead of resolved.

INDIVIDUALS, TOBACCO USE, AND RELATED ACTIVITIES

At the core of the tobacco use management system are people using tobacco products. Users’ primary associations are with the tobacco industry (or their agents); the number and strength of these associations, largely represented by tobacco use, defines the state of the system at any time.

The first fundamental problem for the management of tobacco use is that humans are social animals vulnerable to nicotine dependence. Dependence, as it emerges, is experienced as desire, not compulsion, so there are few potent “warning signals.” Dependence makes smokers unable to act rationally when informed of the harms of tobacco use. They also tend to underestimate the harm7,8: smoking does not feel harmful, the harms occur years after use commences, and the industry has cultivated a false controversy over the harms. Even when smokers admit smoking is harmful, they are ambivalent about the harm (because of the immediate constraints of the addiction) rather than unequivocally committed to quitting (because they enjoy smoking). Many believe smoking helps them manage stress,9 although beyond the moment such beliefs are ill originated: smokers who quit have less stress.10

Smokers also embed smoking into everyday cultural practices and rituals, something magnified by tobacco industry marketing strategies (e.g., creating associations between smoking and modernity).11–13 This normalization of use, along with the addictive nature of tobacco, means that progress to reduce tobacco use will continue to be slow. Our analysis suggests that any framework that presumes full human autonomy for tobacco use is false, and thus the free-market creed—which frames the tobacco problem as a consequence of autonomous individuals choosing harmful products rather than of the industry supplying those harmful products—is fundamentally flawed.

The failure of the system of users and suppliers to act in the long-term interests of users provides the main rationale for external, government intervention. Although we might expect smokers to have an intrinsic tendency to oppose restrictions on their actions if they feel such restrictions infringe on their freedoms, there is a positive association between the extent of tobacco control regulation and smokers’ support for further regulation.14 Smokers, in their more rational moments, realize that they have a problem that is beyond their volitional control.

TOBACCO INDUSTRY SUBSYSTEM

Although the tobacco industry subsystem can be extended to include such groups as growers and retailers, we focus on the major manufacturers and marketers of tobacco products, particularly cigarettes. In advanced Western industrialized countries such as the United States, a small group of companies, including Philip Morris and Brown & Williamson (BAT), dominates the cigarette market.

Until recently, the epidemiology of tobacco use has focused on the harmfulness of tobacco, particularly cigarettes, rather than on relative harmfulness. However, the experience in other countries—Sweden in particular—has changed that.15 Several authoritative reports have concluded that smokeless tobacco can be made far less harmful than can tobacco that is smoked.16–18 The second fundamental problem is that the forms of nicotine that are currently most attractive to consumers, such as cigarettes, are the most harmful and have the least prospect of having their harmfulness reduced.

The tobacco industry could have responded to the science about the harms19 by ceasing to make cigarettes or by ceasing to market them in ways that added value to the basic cigarette via packaging and chemicals to enhance taste, reduce harshness, and increase the amount of free nicotine, but they have not. In the past, manufacturers and marketers of tobacco colluded to deny the adverse health effects of smoking.20 They have used free-market logic to argue that they should be allowed to continue to market tobacco as long as it can be legally sold,11,21 and they continue to market aggressively, particularly in the developing world where there are few effective constraints. Indeed, the tobacco industry has been proactive in lobbying for a globalized free-trade environment.22 It has also attempted to undermine arguments for tobacco control by ghost authoring “scientific” reports purporting to show that tobacco control regulations do not work.23 Similarly, the industry's attempts to subvert the passage of the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control are well documented.24,25 It supports, or even funds, prevention programs it knows are either weak or ineffective. In addition, it has employed language that implies that tobacco controllers are extremist, alarmist zealots, whereas the industry is the voice of reason. When this fails it has reverted to litigation against those contesting their position.26 To date, these efforts have been successful, at least in delaying the decline of tobacco businesses, as they remain highly profitable.

Tobacco companies are commercial enterprises and thus are obliged to maximize value to their shareholders, typically by maximizing profits through increased sales of their products. They are dependent on continuing tobacco consumption. They are not motivated to harm their customers; this is against their long-term interests. However, they need to attract and retain customers, so if the harm is far enough in the future (to allow time for a profit to be made), doing harm is “acceptable” to them if the alternative is not having customers. As long as their products are net harmful, their central goal is diametrically opposed to the goal of the tobacco use management system (systemic problem number 1). Because of this incompatibility of goals, their public positioning is constrained. Because they cannot be seen to openly pursue their real goal, they are left to obfuscate, delay, and undermine what they think will work and “responsibly” support tobacco control actions that they believe will be ineffective.

The options for a profit-making tobacco industry are structurally and functionally constrained. If they could successfully market less harmful alternatives, they would have a potential solution. However, the search for alternatives has only identified smokeless products (either versions of the nicotine products currently used as cessation aids or cleaner forms of smokeless tobacco), and getting smokers to move to these products is not straightforward. Further, the big cigarette companies have generally not sold smokeless tobacco products. In the past, it has proved too difficult to develop business models that would move smokers away from combustible tobacco to less harmful alternatives while maintaining company profitability, but this may be changing.

Having accepted the harms, the industry needs to be seen as responsible marketers, working toward reducing the harmfulness of their products, and there is increasing activity on this front. Cigarette companies are now actively experimenting with marketing smokeless tobacco, including buying up or collaborating with smokeless tobacco companies. Philip Morris has actively supported the regulation of tobacco in the United States while concomitantly lobbying for limits to those powers.21 At this point it is unclear what prospects there actually are of replacing cigarettes with smokeless products and whether the tobacco industry's activity is a strategic attempt to guard against policies that might more rapidly phase out cigarettes.

TOBACCO USE CONTROL SUBSYSTEM

The tobacco use control subsystem consists of those institutional and other actors that are pursuing the reduction or elimination of tobacco use to reduce its harms or to financially profit from doing so (e.g., pharmaceutical companies that market cessation aids). It is constituted within the broad health system, although significant elements do not necessarily share this system's goals. Unlike the tobacco industry, in which a small number of large and powerful companies dominate, the tobacco use control subsystem is a diffuse and decentralized network with no clear center of power. It has grown in response to a perceived gap between the power of the industry and the capacity of government to effectively control it. For the most part, it has not had active populist support, except on the secondhand smoke issue. Its emergence as a counter to a system “out of control” has clear parallels with the environmental movement. Both began as wholly public interest networks that evolved to challenge externalities, which are harmful outcomes attributable to the inadequate regulation of corporate behavior. However, as pharmaceutical companies (in the tobacco control context) and energy companies (in the environmental context) have begun to see profitable opportunities, they have become useful allies, at least for some aspects of the agenda.

In many countries the power of this subsystem has increased to the point where it now has the capacity to reach smokers proactively through the mass media27 as well as an increasing range of cessation aids and vehicles for delivering them. This increase in functional capacity, from a relatively reactive focus on individuals to a more proactive focus on populations, is the one area of tobacco control in which functional change has been widely adopted. However, it lacks the dynamic capacity to adapt to ongoing activities from the other subsystems (particularly the industry) and to the external environment, thus constraining its capacity to control tobacco use.

Tobacco control infrastructure, apart from that created through the sale of cessation aids and health insurance policies, relies on government support, typically through health departments. However, this support is typically not tied to achievements. The health costs of smoking and the savings from effective control are treated as externalities and do not feed back into resources for prevention. In some jurisdictions, this systemic problem (systemic problem number 2) has been at least partly resolved by linking the resourcing of tobacco control initiatives to the estimated reduction in health care costs produced by preventing smoking or encouraging cessation (e.g., through health maintenance organizations in the United States and through the recent Council of Governments agreement to link health funding to tobacco prevalence reductions in Australia).

The other role assumed by the tobacco use control subsystem is to advocate rules to further constrain the industry. This oppositional role tends to produce a strong “them and us” framing—a polarizing Manichean fight against the “evil” tobacco industry. Although this may help keep the diverse coalition of interests together, it can become problematic because the antitobacco forces and the industry are, in truth, interdependent, and interdependent subsystems need to be able to switch between cooperation and competition as the situation requires. Newton28 provided an analysis of this point with regard to the environmental movement. When regulators begin to consider regulations that necessitate dialogue with the industry, tobacco control networks are caught in a quandary. Being separated from such deliberations, they tend to take an overly skeptical approach, especially when sections of the industry support proposed actions. A common benchmark in tobacco control is “the scream test”29: if the industry screams, the initiative must be worthwhile; if they do not (or, even worse, if they support a policy), it must be in some way flawed. Unfortunately, this transforms a reason for caution into a defining proscription, in effect precluding any support for actions that are in the joint interests of the tobacco industry and tobacco control or that involve industry cooperation.

The industry's emerging internal realignment on the need for tobacco product regulation and on the potential role of harm-reduced products could actually serve the interests of tobacco control. However, key actors within the tobacco control movement perceive it as a threat,30 and as a result much of their activity is designed to thwart or stalemate it, rather than treat it as a potential opportunity and look for possible benefits. There is a reluctance to consider alternative ways of delivering nicotine, except in the form of short-term cessation aids (e.g., nicotine gum). Governments have also been slow to analyze the implications of the industry repositioning. This has produced a stalemate as far as regulation of the industry and its products is concerned.31 Like all drug control coalitions, there is a high level of polarization between “harm minimization” and “zero tolerance” advocates, and fear of open conflict as well as the absence of a common goal help maintain the stalemate. The significant levels of polarization and stalemate within the tobacco use management system is systemic problem number 3, because it means that functional changes (e.g., switching to less harmful forms of nicotine delivery) are currently not negotiable, leaving only existing resources and incremental structural changes largely focused on smokers available for the control of tobacco use.

THE REGULATORY SUBSYSTEM

The current rules under which tobacco use occurs have been static. They focus on product marketing and the conditions under which individuals can use tobacco (e.g., age restrictions and smoke-free rules) rather than on product attributes. They are a set of ad hoc rules implemented in the hope that they will make the problem go away rather than a structure designed to manage a problem. Most governance lies outside the tobacco use management system; in many countries, responsibility for implementing the various pieces of tobacco control legislation or regulation is not located in 1 central agency. Tobacco-specific laws constrain only some actions of the tobacco industry, and the rules under which the tobacco use control subsystem operates are from the broader health suprasystem, which governs such things as pharmaceuticals and health professional–client relationships. This fragmentation and lack of executive power means there is limited coordination, a serious lack of strategic capacity, and no power to respond to changing conditions. This is systemic problem number 4.

Governments are beginning to realize that a more dynamic regulatory framework is needed, with key functions delegated to an agency that is part of the tobacco use management system. The World Health Organization Framework Convention on Tobacco Control has articles encouraging product regulation. The US Congress passed legislation in 2009 to give the Food and Drug Administration regulatory powers over tobacco products and some aspects of tobacco marketing. This agenda-setting advance will provide some dynamic powers to regulate products; however, unless it can use these powers to help coordinate the entire tobacco use management system, there are risks it will come to be seen as operating in the interests of the tobacco industry, not of tobacco control. That said, it represents an important initial step toward providing the tobacco use management system with an integrated set of dynamic powers.

Effective regulatory agencies require the capacity to manage the problem comprehensively, and this requires the capability to strategically analyze both the problem and the tobacco use management system as a whole, including the ability to evaluate progress toward the development of new solutions. Models for this form of evaluation have been developed (e.g., by the International Agency for Research on Cancer32). A stronger regulatory subsystem should have the capacity to resolve the stalemates that currently slow progress in tobacco control.

EXTERNAL INFLUENCES

The main external influence on the tobacco use management system is the “whole of government” system, which encompasses all the modifiable parts of the 3 subsystems that jointly influence tobacco use and sets overarching goals that are presumably intended to integrate government strategies. A key issue for government is to decide which powers to delegate into the regulatory arm of the tobacco use management system and which to keep for itself, realizing that it does not have the capacity to actively manage the tobacco use management system (i.e., it is too preoccupied with other issues to become an effective part of the tobacco use management system). It, nevertheless, has to ensure that the tobacco use management system is constrained from acting in ways that threaten other social values that are as highly or more highly valued (e.g., economic stability).

Two main overlapping suprasystems also influence the functioning of the tobacco use management system. These are the public health system, which sets higher order goals for the tobacco use control subsystem, and the economic system, which largely determines the goals of the tobacco industry. These 2 suprasystems try to shape those aspects of the tobacco use management system that are within their control to be more consistent with their goals. They are likely to resist actions of the tobacco use management system (or its constituent parts) that threaten their goals. Further, they can act to preserve their integrity in ways that result in changes to the tobacco use management system regardless of the consequences for tobacco control; for example, they may enable deregulatory policies that provide tobacco companies with more freedom to market their products. Currently, both need to be engaged in attempts to change the tobacco use management system, but because neither is fully engaged by the issue and they have different broader goals, gaining consensus can be difficult, and there is generally no incentive to work toward a detailed resolution (systemic problem number 5).

Managing these broader dynamics, via the multiple and varied agents that influence them, is difficult, but if the relevant agents can be brought together and consensus achieved, rapid changes in fundamental system properties can occur (e.g., the current realignment of the rules for global finance). However, the slow, complex process being followed in the pursuit of effective tobacco control, or climate change management, reveals just how difficult the task of engaging adaptively with these forces is, owing to their competing priorities and the different perspectives they bring.

There are 2 other forms of external influence that warrant consideration: the “mediating systems” and broader external trends (social, political, technological, ecological, and so on) to which all systems are subject. Effects on the tobacco use management system from the latter (e.g., global warming, financial instability, and social and technological change) typically require system flexibility because they are usually not amenable to overarching control. Mediating systems, such as the mass media and science, provide processes and tools—including new cessation aids and means of distributing them—that allow subsystems to operate more effectively and, as such, are not directly concerned with the goals of the tobacco use management system, although actors using these tools need to conform to the process rules that these systems impose.

Just as our economic systems produce waste, tobacco use produces externalities that the system itself does not manage. These include death and disease, the associated health care costs, and tax revenues in most countries. As we have noted, one major reason for the continuing tobacco problem is that these externalities, which should provide powerful motivators for action and resources, do not have a strong impact, because they are not dynamically integrated with tobacco use management.

CHANGING COMPLEX SYSTEMS

Problems such as tobacco—with overlapping suprasystems contending for their management (e.g., the health system vs the economic system) and with parts owing to human nature, characteristics of tobacco, and the constraints the environment places on human activity that are beyond the scope of human institutions to solve—are notoriously difficult to resolve and for this reason are sometimes called “wicked” problems.33 The nature of the solution to wicked problems emerges only as the problem begins to be tackled and its dynamic reactions to change become understood. Wicked problems do not have simple solutions.

Systems are also typically unable to change their functions from within, and they may be unable to exercise internal powers for enacting change when there is polarization and stalemate between or within their subsystems.34 Stalemate occurs where the system fails to operate to achieve its goals and there are forces strong enough to resist needed change. Although social and economic organizations are purposeful by definition,35 stalemated systems come as close to being purposeless as is possible. Maruyama36 spoke of a “goal moratorium” to communicate a strikingly similar situation. Stalemate typified early attempts to manage tobacco use, where the willingness of the government to regulate was matched by the capacity of the industry to resist.

The search for solutions requires the dynamic capacity to analyze facts and to situate them within the values and priorities of the society, realizing that sometimes simple solutions (e.g., prohibition or leaving the problem to market forces) can actually be counterproductive. It is therefore imperative that the system have the capacity to be dynamically adaptive, which requires delegating as much regulatory capacity as possible to the tobacco use management system. That said, governments need to remain involved at some level. They have a responsibility to act for the benefit of the entire society, not of particular interests.37 One of the great unspoken truths of government is that it is impossible to simultaneously meet all its espoused goals and the aspirations of all interest groups, so compromises have to be made. Part of the art of government is to shape these compromises to accommodate as many interests as possible, and there may be similar constraints on enforcing rules once implemented.

Relevant social and economic factors should be considered in the debate as to what changes are required. Particular instruments may be seen as precedents for actions in other areas that the government may not want to contemplate, such as calls for parallel actions to control alcohol use or support for toxin-reduced oral tobacco as part of a harm minimization strategy that may conflict with broader philosophical positions espoused by the government (e.g., “zero tolerance” in drug control). Sometimes the ideal innovation is not pursued because of a reluctance to engage overlapping suprasystems that may successfully contest the change. The change that is pursued is thus limited to areas within the sphere of influence of supportive societal forces. This is understandable, as systems tend to be inherently conservative and will generally act to limit changes to those that are minimally disruptive to their own interests. Finding ways to overcome this inertia is a challenge but sometimes needs to be confronted.

The first and most critical step in system reform is to identify the goals the system needs to pursue (including new or revised ones) and to work out what systemic changes are required to most effectively achieve the most ambitious goals. This requires analyzing the implications that both goals and mechanisms have for other societal interests, such as the impact on employment in the tobacco industry, effects on tax revenues, and the changed amenity value of smoke-free places. Once such an analysis is in place, there can be an informed social process for negotiating change.38 It is reasonable to seek, or accept, compromise only after we have worked out what is in principle achievable, because then we have a sense of what is being given up.

Truly adaptive systems should have an inbuilt and dynamic capacity to produce the internal changes that are needed to confront the problem they are set up to manage. There are 3 broad ways systems can be regulated: (1) by changing rules about what existing parts of the system are allowed to do, that is, changing system constraints (e.g., antitrust laws, restrictions on sales to minors, restrictions on advertising, extra resources for a smoking cessation service, allowing a new cessation drug onto the market); (2) by adding new elements or subsystems to change the balance of forces (e.g., introducing tobacco control programs to counter industry influence); and (3) by changing the nature of existing subsystems to make them more consistent with the system goals (e.g., restructuring tobacco marketers so that they are no longer driven by commercial imperatives to try to increase tobacco use). This is regulation designed to affect system rules, and thus the very nature of organizations, and what they are motivated to do.

The latter 2 forms of regulation would introduce functional changes in the system. Our analysis demonstrates that fundamental changes are needed in all 3 of the subsystems that provide institutional influences on tobacco use. This widens the range of potential solutions to reform the tobacco use management system so that it can achieve its goals more effectively.

REFORMING THE TOBACCO USE MANAGEMENT SYSTEM

The heart of the tobacco problem is that humans enjoy using nicotine, they are vulnerable to becoming dependent, and they currently prefer the source of nicotine (cigarettes) that is the most harmful to their long-term health. We have identified 5 systemic problems with the current tobacco use management system that make the effective management of tobacco more difficult: (1) tobacco is marketed to consumers by for-profit companies whose goal to sell more tobacco is at odds with the espoused societal goal of reducing use, (2) the tobacco use control system has limited dynamic capacity to create and meet demand for smoking cessation and prevention services, (3) the tobacco control community is split over the priority accorded to use reduction versus harm reduction, (4) there is no dynamic capacity of what is currently a rudimentary regulatory subsystem, and (5) much of the control of key subsystems is exercised by competing suprasystems with little focal interest in the problem.

Our analysis explains why individuals have reduced capacity to act in their best interests and why there is a need to strengthen and increase the flexibility of the regulatory subsystem to further regulate the tobacco use industry subsystem in addition to strengthening the tobacco use control subsystem. Further, the tobacco use management system is currently polarized with respect to its goal: reduce tobacco use versus reduce tobacco harms. There is a disconnect between the espoused goal to eliminate tobacco use and the attributes of the system that is currently in place, which is designed to manage use. Part of the problem is that the goals of eliminating tobacco use and eliminating tobacco-related harms coexist only while they share the same strategies (e.g., assisting cessation), but when the strategies diverge—as they do with respect to reducing the harmfulness of products because it might slow progress in the elimination of tobacco—there is a risk of coalition schism, and there has been stalemate in this area.

Disagreement within the tobacco control movement over the need and the capacity for engagement with the tobacco industry reinforces this stalemate. Although separation was probably useful when the focus was on tobacco use (where the goals are diametrically opposed), it does not work for harm reduction (where the goals, in principle, converge considerably). The past equation of harm and use reduction was predicated on the assumption, now known to be false, that all tobacco products are equivalently harmful.17 Research is urgently needed to assess both the viability and the threats of accepting a focus on harm-reduced products (including smokeless nicotine) as part of a solution.31,39 There is also an urgent need to build consensus on the purpose of tobacco control and to reshape the tobacco use management system to be able to pursue that purpose as effectively as possible. In the absence of a strategy for eliminating tobacco use on a timescale comparable to that required to develop less harmful products, there is a moral obligation to provide continuing tobacco users with the least harmful products possible. We believe that the purpose of the tobacco use management system should be to minimize tobacco-related harms, with the management of tobacco use a key means to that end.

At present, the tobacco use management system lacks the strategic capacity to coordinate the various stakeholders and adapt to the dynamic situation. Most of the current strategic capacity is marginalized within the tobacco use control subsystem. It is apparent that the regulatory subsystem of the tobacco use management system needs to be strengthened and given dynamic capacity. Achieving the correct balance of powers delegated into the system will not be easy, and government needs to be prepared to review the powers it refers to ensure they continue to be adequate to the task. All this needs to be done in ways that are acceptable to overlapping suprasystems and that are cognizant of the fact that human nature and the nature of nicotine products constrains what is possible. The powers need to provide coordinating capacity so that appropriate support programs for individuals can complement actions directed at the tobacco industry. Given the competing goals within the system, transparency will also be critical. Specific elements of reform include the need for greater regulatory control over tobacco products, more fundamental constraints on the way the tobacco industry operates, and a strengthening of the tobacco use control subsystem.

The tobacco use control subsystem needs to be given the capacity to support stronger prevention efforts, to both grow demand for smoking cessation and support efforts to quit. This will require more resources and, more importantly, allocation of resources tied to achievements. Developing a funding model where resources for tobacco control are linked to services provided, with mechanisms to ensure this is done in a cost-effective way, could achieve this. There is also a need to ensure that tobacco controllers from outside the regulatory subsystem are treated as stakeholders in the tobacco control strategy the system adopts, to ensure that their existing knowledge is used, and to minimize any suspicion that regulation of the industry is not in the best interests of the overall system.

The chief regulatory need is for the tobacco industry to be managed more effectively, something Food and Drug Administration regulation of tobacco will facilitate. The regulatory subsystem needs powers to effectively eliminate inappropriate tobacco marketing, manage reductions in tobacco toxicities, and, at least for the more toxic products, increasingly restrict engineering features that add to consumer appeal. There are 2 broad ways this might be approached: (1) strengthening the current regulatory framework to coerce the industry into acting in ways that it would otherwise resist or (2) engineering fundamental and functional reform of the tobacco industry.

Strategies that realign acceptability and availability with relative harmfulness (e.g., price or banning flavor enhancers for more harmful products) could address the relative availability and attractiveness of nicotine products. While cigarettes remain the most attractive nicotine product to consumers, a free-market solution to the problem is not possible.

In principle, governments could act to change the types of organizations involved in the marketing of tobacco, but this would be difficult because it involves rules that are in the domain of higher-order systems (e.g., those associated with corporations law). However, changing the industry may actually be a more effective strategy than trying to externally constrain the existing industry.40–42 From a strategic perspective the latter is akin to a situation where management is at liberty to adapt via structural refinements to the system for which they are responsible (e.g., by targeting new market segments with their existing product range, by changing their production processes, or by refining their product mix), but they are not at liberty to change the function of the system (e.g., by manufacturing different products or changing their performance criteria to not focus exclusively on return to shareholders, such as “triple bottom line”43).

In the case of tobacco, we have an industry structured to maximize growth-marketing products, the use of which government policy seeks to reduce. Our analysis suggests that government is reluctant to resolve this contradiction partly because it would involve changing rules that emanate from the broader overlapping systems or suprasystems (e.g., corporate governance rules). Unless these powerful forces are prepared to allow tobacco to be an exception, the tobacco use management system will continue to operate with a subsystem whose goals are antithetical to those of the system as a whole. Whatever the theoretical benefits, the range of stakeholders who would need to be consulted is tacitly assumed to be too broad to justify action, and the locus of action is within a system (whole of government) for which tobacco use has very little salience. Thus, the level of commitment required to get a satisfactory solution, one without hidden traps, would be difficult to achieve. The failure of governments to effectively regulate the industry arguably prolongs the problem, and it feeds both public cynicism about government15 and the misperception that “smoking can't be all that dangerous, or the government would have banned it,” which undermines other actions.

In the absence of interventions aimed at changing the nature of the industry itself, tobacco companies will continue to do whatever they can to promote their existing products. However, increasing government (e.g., that of Australia33) realization that complex problems like tobacco use require solutions that cross system boundaries and the parallel issue of a growth-oriented industry operating in a market where external constraints should lead to a contraction are generating some interest in instituting changes that are fundamental and comprehensive. This provides the opportunity for a consensus to be constructed for enacting the fundamental reforms that would adapt the tobacco use management system for meeting the challenge of reducing tobacco-related harm. In the interim, our approach should provide a framework for more comprehensive analysis of the tobacco problem, including identifying research needs.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported primarily by the Inaugural Sally Birch Fellowship in Cancer Control, awarded to D. Young, under the auspices of the Cancer Council Australia. It was also supported by ARC linkage between the Cancer Council Victoria and Monash University (grant LP0669043).

Human Participant Protection

This study was derived from secondary data and did not use human participants, so no approval was required.

References

- 1.Leischow SJ, Milstein B. Systems thinking and modeling for public health practice. Am J Public Health 2006;96(3):403–405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McLeroy K. Thinking of systems. Am J Public Health 2006;96(3):402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Cancer Institute Systems thinking: potential to transform tobacco control. : Greater Than the Sum: Systems Thinking In Tobacco Control Bethesda, MD: US Dept of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute; 2007:37–60 National Cancer Institute Tobacco Control Monograph No. 18. NIH publication 06-6085 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Joffe M, Mindell J. Complex causal process diagrams for analyzing the health impacts of policy interventions. Am J Public Health 2006;96:473–479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Cancer Institute Understanding and managing stakeholder networks. In: Greater Than the Sum: Systems Thinking in Tobacco Control. Bethesda, MD: US Dept of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute; 2007:147–184 National Cancer Institute Tobacco Control Monograph No. 18. NIH publication 06-6085 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Trist E, Emery F, Murray H, The Social Engagement of Social Science—A Tavistock Anthology— The Socio-Ecological Perspective Vol. 3 Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press; 1997 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Borland R. What do people's estimates of smoking related risk mean? Psychol Health 1997;12(4):513–521 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Slovic P. Smoking: Risk, Perception & Policy New York: Sage Publications; 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Balmford J, Borland R. What does it mean to want to quit? Drug Alcohol Rev 2008;27(1):21–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Siahpush M, Borland R, Scollo M. Smoking and financial stress. Tob Control 2003;12:60–66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reid R. Globalizing Tobacco Control Bloomington: Indiana University Press; 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Martini S, Sulistyowati M. The Determinants of Smoking Behavior Among Teenagers in East Java Province, Indonesia Washington, DC: World Bank, Health, Nutrition and Population Division; 2005. HNP Discussion Paper, Economics of Tobacco Control Paper No. 32 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Young D, Yong H-H, Borland R, et al. Prevalence and correlates of roll-your-own smoking in Thailand and Malaysia: results of the ITC-SEA survey. Nicotine Tob Res 2008;10(5):907–916 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Young D, Borland R, Hastings G, et al. Australian smokers support stronger regulatory controls on tobacco: findings from ITC 4-countries survey. Aust N Z J Public Health 2007;31(2):164–169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Foulds J, Ramstrom L, Burke M, et al. Effect of smokeless tobacco (snus) on smoking and public health in Sweden. Tob Control 2003;12(4):349–359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Royal College of Physicians Harm Reduction in Nicotine Addiction: Helping People Who Can't Quit. A Report by the Tobacco Advisory Group of the Royal College of Physicians London: Royal College of Physicians; 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Broadstock M. Systematic Review of the Health Effects of Modified Smokeless Tobacco Products Christchurch, New Zealand: Christchurch School of Medicine and Health Sciences; 2007. New Zealand Health Technology Assessment Report 10(1) [Google Scholar]

- 18.Life Sciences Research Office Differentiating the Health Risks of Categories of Tobacco Products; 2009. Available at: http://www.lsro.org/articles/dtr_0209_pr.html. Accessed March 24, 2009

- 19.US Dept of Health and Human Services Reducing the Health Consequences of Smoking: 25 Years of Progress. A Report of the Surgeon General Washington, DC: US Dept of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 1989. DHHS Publication No. (CDC) 89-8411 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Francey N, Chapman S. “Operation Berkshire”: the international tobacco companies’ conspiracy. BMJ 2000;321(7257):371–374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Benson P. Good clean tobacco: Philip Morris, biocapitalism, and the social course of stigma in North Carolina. Am. Ethnol 2008;35(3):357–380 [Google Scholar]

- 22.McDaniel PA, Intinarelli G, Malone RE. Tobacco industry issues management organizations: creating a global corporate network to undermine public health. Global Health 2008;4:2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Davis RM. British American tobacco ghost-authored reports on tobacco advertising bans by the International Advertising Association and JJ Boddewyn. Tob Control 2008;17:145–146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.World Health Organization. Killing for Profit. Tobacco Industry Monitoring Report; October–December 2002. Available at: http://www.who.int/tobacco/media/en/tob-ind-monitoring02.pdf. Accessed May 26, 2008.

- 25.Mamudu HM, Hammond R, Glantz S. Project Cerberus: tobacco industry strategy to create an alternative to the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. Am J Public Health 2008;98(9):1630–1642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Studlar DT. Tobacco Control: Comparative Politics in the United States and Canada Peterborough, Ontario: Broadview Press; 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 27.National Cancer Institute The Role of the Media in Promoting and Reducing Tobacco Use Bethesda, MD: US Dept of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute; June 2008. National Cancer Institute Tobacco Control Monograph No. 19. NIH publication 07-6242 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Newton TJ. Creating the new ecological order? Elias and actor-network theory. Acad Manage Rev 2002;27(4):523–540 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chapman S. Public Health Advocacy and Tobacco Control: Making Smoking History London: Wiley-Blackwell; 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Britton J, Edwards R. Tobacco smoking, harm reduction, and nicotine product regulation. Lancet 2008;371(9610):441–445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Warner KE. Will the next generation of “safer” cigarettes be safer? J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2005;27(10):543–550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.International Agency for Research on Cancer Methods for Evaluating Tobacco Control Policies Lyon, France: IARC Press; 2008. IARC Handbooks of Cancer Prevention: Tobacco Control. Vol. 12 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Commonwealth of Australia Tackling Wicked Problems Canberra, Australia: Australian Public Service Commission; 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gloster MJ. A Grounded Socio Ecological Theory of Managing Active Adaptation of Stalemated Social Systems, in Localised Vortical Environments [dissertation] New South Wales, Australia: Southern Cross University; 1999 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ackoff RL, Emery FE. On Purposeful Systems London, United Kingdom: Tavistock Publications; 1972 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maruyama M. Mindscapes, management, business policy, and public policy. Acad Manage Rev 1982;7(4):612–619 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Finn P. Sovereign people, a public trust. : Finn P, Essays on Law and Government: Principles and Values Sydney, Australia: Law Book Company; 1995:1–33 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Young D, Borland R, Coghill K. An actor network theory analysis of policy innovation for smoke-free places: understanding change in complex systems. Am J Public Health 2010;100(7):1208–1217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gilmore AB, Britton J, Arnott D, et al. The place for harm reduction and product regulation in UK tobacco control policy. J Public Health (Oxf) 2009;31(1):3–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Borland R. A strategy for controlling the marketing of tobacco products: a regulated market model. Tob Control 2003;12(4):374–382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Borland R. Why not seek clever regulation? A reply to Liberman. Tob Control 2006;15(4):339–340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Callard C, Thompson D, Collishaw N. Curing the Addiction to Profits: A Supply-Side Approach to Phasing Out Tobacco Ottawa, Ontario: Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives; 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 43.Elkington J. Towards the sustainable corporation: win-win-win business strategies for sustainable development. Calif Manage Rev 1994;36(2):90–100 [Google Scholar]