Abstract

The guinea pig has been the most commonly used small animal species in preclinical studies related to asthma and COPD. The primary advantages of the guinea pig are the similar potencies and efficacies of agonists and antagonists in human and guinea pig airways and the many similarities in physiological processes, especially airway autonomic control and the response to allergen. The primary disadvantages to using guinea pigs are the lack of transgenic methods, limited numbers of guinea pig strains for comparative studies and a prominent axon reflex that is unlikely to be present in human airways. These attributes and various models developed in guinea pigs are discussed.

Keywords: Leukotrienes, Autonomic, Influenza, IL-5

1. Introduction

Guinea pigs have been the most commonly used small animal species in preclinical studies related to asthma and COPD [1]. Many fundamental processes, mediators and regulators of airways disease pathogenesis were discovered or demonstrated first in guinea pigs, including the Schultz–Dale (immediate type hypersensitivity) reaction, the actions of histamine, the cysteinyl-leukotrienes and their two receptors, beta adrenoceptor subtypes, thromboxane, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), eotaxin, alveolar macrophage derived neutrophil chemotactic factor(s) (leukotriene B4 and/or IL-8) and the roles of cAMP and inositol triphosphate in signal transduction [2-19]. Receptor pharmacology in guinea pigs more closely matches that of human receptor pharmacology than most other commonly used species [1,20,21] (Table 1, Figs. 1 and 2). Several breakthroughs in measuring lung mechanics were developed first in studies using this species, while models of the late phase response following an allergen challenge have been perfected in guinea pigs [22-27]. The emergence of transgenic mouse studies has and will continue to result in the diminished use of guinea pigs for modeling airways disease. This is unfortunate, as for many endpoints guinea pigs are superior to mice for studies of processes related to asthma and COPD [1,27-29]. These advantages as well as the disadvantages of using guinea pigs to study basic processes related to asthma and COPD pathogenesis are briefly reviewed.

Table 1.

Receptor antagonist pA2/pKb values at guinea pig and human receptors

| Receptor subtype | Guinea pig | Human |

|---|---|---|

| Muscarinic M3 | ||

| Atropine | 9.0, 9.5 | 9.1 |

| Ipratropium | 9.9, 9.6 | 9.3 |

| Methoctramine | 5.6, 5.6 | 5.3 |

| Pirenzepine | 6.7, 7.0 | 6.8 |

| Tiotropium | 9.97 | 9.99 |

| Leukotriene cysLT1 | ||

| ICI 198615 | 10.1 | 9.8 |

| SKF 104353 | 8.9 | 8.4 |

| MK-0476 | 9.3 | 9.1 |

| MK 571 | 9.4, 8.0 | 8.5 |

| ONO-1078 | 10.4 | 8.3 |

| FPL55712 | 7.5, 6.4 | 6.0, 6.5 |

| Neurokinin2 | ||

| SR 48968 | 9.1, 9.2, 9.4 | 9.0, 9.5, 9.5 |

| SCH 206272 | 7.7 | 8.2 |

| MEN10376 | 6.5 | 6.2, 6.3 |

| GR159897 | 8.2 | 8.6 |

| MDL103392 | 7.0 | 7.2 |

| Prostanoid TP | ||

| BAY u3405 | 8.1 | 9.0, 9.4 |

| AH 6809 | 5.3 | 5.5 |

| ICI 192605 | 10.0 | 9.5 |

| GR 32191 | 9.5 | 8.4 |

| AA2414 | 7.7 | 7.6 |

| β2 Adrenoceptor | ||

| Atenolol | 5.7 | 5.3 |

| ICI118551 | 8.2, 8.8, 9.2 | 9.1 |

| Propranolol | 8.6, 9.0 | 9.3, 9.4 |

| Endothelin ETB | ||

| BQ123 | <5 | <5 |

| SB209670 | 6.1 | 6.1 |

| Ro470203 | 5.6 | 5.4 |

| PD145065 | 6.8 | 7.7 |

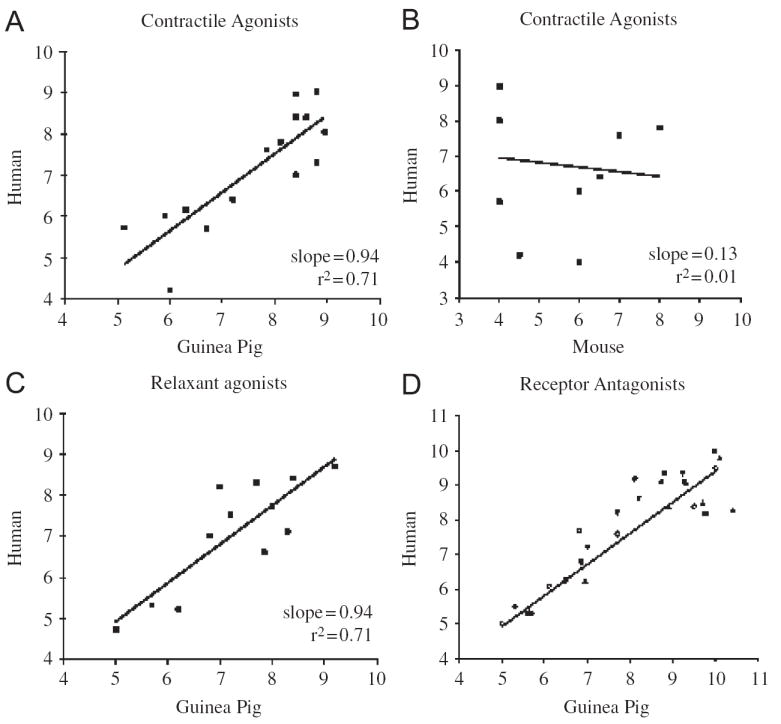

Fig. 1.

Potency estimates (pD2) and potency correlations for airway smooth muscle contractile and relaxant agonists in humans, guinea pigs and mice and the relationship between estimated potencies of receptor antagonists in guinea pig airways to that reported in studies using human airways. The potencies of contractile (panel A) and relaxant (panel C) agonists in guinea pigs are highly predictive of their potencies and efficacies (not shown) in human airways. This contrasts with murine airways (panel B), in which many contractile agonists implicated in asthma and COPD (LTC4, LTD4, histamine, NKA, PGD2) do not contract murine airway smooth muscle (for the purposes of graphic illustration, these agonists were given pD2 values of 4 in mice). Receptor antagonist potencies (pA2 and/or pKb values) in guinea pigs were also highly predictive of their potency in human airways. Data from studies of M3 (■), cysLT1, (▲), NK2, (▼), TP (◇) and ETB (○) receptor antagonists are depicted. See Table 1 for more details.

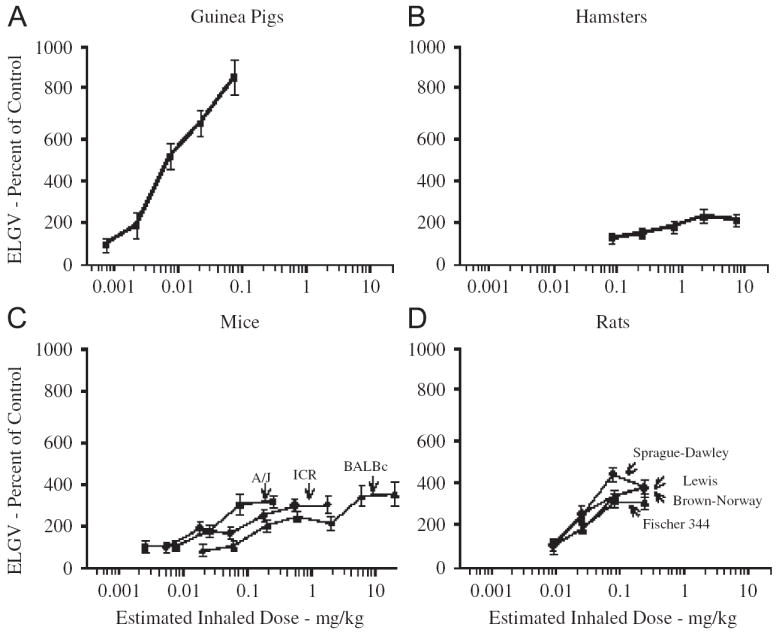

Fig. 2.

Methacholine-induced gas trapping in guinea pigs and hamsters and various strains of mice and rats. Data are the mean±SEM of 4–6 experiments and expressed as a percentage of the excised lung gas volume (ELGV) in unchallenged (control) animals of similar weight, sex, species and strain. Relative to other small mammalian species, guinea pigs are far more susceptible to gas trapping during bronchospasm. Figure modified from [308].

2. Anatomy and physiology

The anatomy and physiology of the guinea pig lung resembles that of humans [20,21,30-35]. A pseudo-stratified epithelium lines the trachea, mainstem bronchi and large intrapulmonary bronchi of both species [31,36]. Vagal afferent nerves, including C-fibers and mechanoreceptors, innervate the epithelium and subepithelial spaces [35,37]. Goblet cells and mucus glands are found in the large airways and their function is regulated both neuronally and by locally released autacoids [32,34,38]. A subepithelial vasculature is found between the epithelium and smooth muscle layer [30,39,40]. These features are similar in guinea pig and human airways but very different from that of the mouse, which largely lacks a subepithelial vasculature, and has few if any glands (but many goblet cells) and a sparsely innervated epithelium [28,41-43]. Neuroendocrine cells and neuroepithelial bodies are also localized to the epithelium of guinea pigs and humans [44-47].

Airway smooth muscle in guinea pigs is both anatomically and functionally similar to that of human airway smooth muscle. Contractile and relaxant agonists of human airway smooth muscle have nearly identical potency and efficacy in guinea pig airway smooth muscle (Table 1;Fig. 1). Due to the size of the airways and thus the limited number of cells recoverable from guinea pigs, few studies of muscle proliferation and/or muscle synthesizing activity have been completed in guinea pigs. But smooth muscle hyperplasia has been observed in models of allergic inflammation [27,48]. Airway smooth muscle (and the epithelium) is also a major source of eotaxin in human and guinea pig airways [49,50]. In both species, isolated airway smooth muscle preparations display a spontaneous tone that has been attributed to locally produced autacoids. In human airways, this basal tone has been attributed to histamine and cysteinyl-leukotrienes released from resident mast cells [51]. In guinea pigs, basal tone is mediated by prostaglandin E2, formed tonically by cyclooxygenase-2 activity [52-55]. Human airways also have a tonic cyclooxygenase activity but may lack the EP1 receptors on the smooth muscle that mediate basal tone as seen in the guinea pig [55-57]. Similarly, there is evidence for a tonic cysLT1 receptor mediated regulation of airways in guinea pigs [58,59]. In both species, this basal tone mediated by autacoids appears to be manifest both in vivo and in vitro [58,60-62].

The autonomic innervation of airway smooth muscle in guinea pigs closely resembles that of humans [35]. Parasympathetic cholinergic nerves mediate contractions of human and guinea pig airway smooth muscle through the actions of acetylcholine acting on post-junctional muscarinic M3 receptors [63-67]. In both species, a basal level of cholinergic tone is measurable in vivo as evidenced by the bronchodilating effects of M3 receptor antagonists [35,68-70]. Also present in both species are prejunctional M2-like receptors that autoregulate (inhibit) acetylcholine release [64,71-73]. Other mediators regulating cholinergic tone prejunctionally, either inhibiting or facilitating acetylcholine release, act similarly in humans and in guinea pigs. These include PGE2, serotonin, tachykinins, beta adrenoceptor agonists, μ-opioid receptor agonists, and vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) and related peptide neurotransmitters [74]. In both species, nicotinic-cholinergic receptors mediate synaptic transmission in airway parasympathetic ganglia [35]. Sympathetic-adrenergic relaxant innervation is sparse and/or nonexistent in the intrapulmonary airways of both species (the guinea pig trachea is densely innervated by sympathetic adrenergic nerves). The primary functional relaxant innervation in both species is parasympathetic and noncholinergic in nature. VIP (and related peptides) and the gaseous transmitter nitric oxide (NO, synthesized from arginine by the the neuronal isoform of NO synthase) have been implicated in nonadrenergic–noncholinergic nerve-mediated relaxations of human and guinea pig airway smooth muscle [35,75-78]. VIP and NO synthase have both been identified in the airway parasympathetic nerves of human and guinea pig airways. Stimuli initiating reflex bronchospasm in human subjects evoke similar reflexes in the guinea pig [35]. Stimuli evoking cough in humans also evoke cough in guinea pigs [37]. It is debatable as to whether rats or mice possess a cough reflex. It has also been shown that rats and mice and dogs lack entirely a direct, functional nonadrenergic relaxant innervation of their airway smooth muscle [35,79,80].

Signal transduction in airway smooth muscle cells and in inflammatory cells is also very similar in human and guinea pig airways [81-95]. Smooth muscle contractions are associated with a rise in intracellular Ca+ + (following influx from extracellular spaces and release from intracellular stores) secondary to inositol phosphate turnover [67,96-98]. Contractile agonists likely work through receptors coupled to the G-protein Gq, which has been localized to or demonstrated functionally in airway smooth muscle in both species [81]. Some agonists are also coupled to Gi, which when activated can inhibit adenylate cyclase activity [99-102]. Relaxant agonists work in both species through the cyclic nucleotides cAMP (formed from ATP by adenylate cyclase) and cGMP (formed from GTP by soluble guanylate cyclase) as well as through Ca+ + activated K+ channels [94,103-106]. Cyclic nucleotides are subsequently inactivated by several isozymes of phosphodiesterase (PDE). PDE III, PDE IV and PDE V have all been identified in airway smooth muscle and in inflammatory cells in both guinea pigs and humans [92,94,107-113]. PDE VII, which has been implicated in regulating human immune responses, has not been studied in guinea pigs.

The immediate hypersensitivity response of human and guinea pig airways to allergen (smooth muscle contraction, mucus secretion, vasodilatation and plasma exudation) is attributable in large part to the actions of histamine and leukotrienes acting on histamine H1 receptors and leukotriene cysLT1 receptors [20,21,38,82,85-87,91,114-124]. Resident mast cells in the airways likely mediate this acute response to allergen challenge. In both species, airway mast cells are activated by the purine adenosine but are insensitive to substance P and contain little, if any, serotonin [121,125-128]. This contrasts with mice and rats. Histamine, LTC4 and LTD4 are largely inert in rat and mouse airways and mouse and rat mast cells store and release abundant serotonin [125,129-132]. Also unlike guinea pig and human lung mast cells, rat mast cells are degranulated by substance P [127,133,134]. Dissimilar to human lung mast cells, cross-linking of either IgE or IgG1 receptors activates guinea pig mast cells, whereas only IgE receptors appear to be functional in humans [135-137]. Murine mast cell activation is also largely IgE independent [138-140]. Some but not all studies also indicate that that unlike human mast cells, guinea pig (and mouse) mast cell activation is directly inhibited by corticosteroids [86,141-145].

The primary cell type found in bronchoalveolar lavage of both humans and guinea pigs is the alveolar macrophage. The guinea pig is thought to be more “eosinophilic” at baseline, as evidenced by the higher percentage of eosinophils recovered by lavage of unchallenged guinea pigs relative to that seen in humans and the presence of eosinophils in cross-sections through airways of seemingly healthy, unchallenged guinea pigs [25-27,95,146-148]. This may be due to a constituitive expression of the chemokines eotaxin and CCL5 (RANTES) in the airways of guinea pigs [49,149]. Upon challenge, lymphocytes, monocytes, eosinophils and neutrophils are recruited to the airways of guinea pigs with varying kinetics and numbers depending on the stimulus. Unlike that in human and mouse airways, the precise phenotypes of the monocytes and lymphocytes in the airways of guinea pigs have been poorly characterized [25,26,141,150].

3. Response to experimental challenges

3.1. Agonist mimicry studies

Mediators implicated in the pathogenesis of asthma and COPD produce inflammation and physiological responses in guinea pigs predictive of their role in these human respiratory diseases. Autacoids and neurotransmitters that evoke bronchospasm in human subjects, including the cysteinyl-leukotrienes, histamine, neurokinin A, platelet activating factor (PAF), substance P, bradykinin, endothelin, thromboxane, acetylcholine and other muscarinic receptor agonists all evoke bronchospasm in guinea pigs (Table 1; Fig. 1). In both species, a component of the response to these constricting agonists is reflex in nature [35]. Inflammatory autacoids, chemokines and cytokines including LTD4, LTB4, TNFα, IL-5, IL-8, IL-13, PAF and eotaxin induce inflammation and cellular infiltration into the airway wall and the airspaces of guinea pigs as they are likely to do or have been shown to produce in human subjects [11-13,87,147,151-175]. Mucus secretion and mucus production can be induced in both species by muscarinic receptor agonists, the cysteinyl-leukotrienes, elastase, TNFα, IL-13 and PAF [34,38,155,172,175-183].

3.2. Allergen challenge

The acute response to allergen challenge in guinea pigs is nearly identical to that evoked in atopic human subjects. A combination of H1 and cysLT1 receptor antagonists essentially abolishes the effects of allergen on lung mechanics [20,21,114-117,120,124]. Other mediators associated with the acute allergic response in humans including bradykinin, PGD2 and PAF have been recovered or demonstrated (through antagonism or inhibition) acutely following allergen challenge in guinea pigs [114,117,142-144,163,184-190]. Autacoids, chemokines and cytokines shown to be or likely to be formed secondary to the effects of histamine and leukotrienes, including PGE2, thromboxane, HETEs, IL-5, IL-13, eotaxin, nerve growth factor and bradykinin have also been recovered from the airways or found active based on functional studies in both species [12,13,49,114,143,146,147,149,158,161,185-187,189-208]. The late phase physiologic response in human subjects is largely inhibited by a combination of histamine and leukotriene receptor antagonists and is associated with an influx of eosinophils into the airway wall and air spaces [124,135,143,155,158]. Comparable results have been reported in studies of the late response in guinea pigs [25-27,86,120,121,141,145,155,162,192,195-197,201,204]. Therapeutics including steroids and anti-IL-5 prevent the late phase eosinophilia evoked by allergen challenge in both species [141,143,145,154,158,162,192,194-197,204]. An effect on airway nerves following allergen challenge has been documented in both human subjects and in guinea pigs [35,199].

Guinea pigs share with mice the shortcoming of utilizing IgG1 as well as IgE in regulating the immediate hypersensitivity response to allergen [137-140]. Otherwise, guinea pigs are superior to mice and rats for modeling both the acute and late phase physiologic response to allergen. As mentioned above, the mediators of the acute response in humans and guinea pigs are histamine and the cysteinylleukotrienes. Histamine, LTC4 and LTD4 have no direct effects on murine or rat airway smooth muscle [129-131]. Murine and rat mast cells store and release 5-HT as their primary biogenic amine and 5-HT is the primary mediator of the acute response to allergen in these rodents [125,132]. Human and guinea pig mast cells store little, if any, 5-HT, and 5-HT is without effect on human airway smooth muscle [21,125,126]. The potent neural activator and vasoconstrictor serotonin, with both ionotropic and metabotropic receptors, likely has very different actions than the vasodilator histamine, which acts only on metabotropic receptors.

3.3. Cigarette smoke

As the lifespan of a guinea pig (2–3 years) is shorter in duration than the number of smoking pack years of the vast majority of patients with COPD, it is difficult to equate typical cigarette smoke exposure protocols in guinea pigs with the human condition of COPD. But the pathology of cigarette smoke exposure is similar in guinea pigs and humans. Features of the cigarette smoke-exposed lung of guinea pigs similar to that seen in COPD include an acute neutrophilia, a slowly developing but sustained recruitment of monocytes, alveolar destruction, mucus secretion, increased epithelial permeability, altered reflexes and pulmonary hypertension [209-219].

3.4. Viral infections

Guinea pigs are susceptible to infections by respiratory syncytial virus, influenza virus, parainfluenza virus and adenovirus, each of which having been associated with or used to model exacerbations of asthma and COPD [72,220-230]. In both humans and in guinea pigs, these infections are characterized by inflammatory cell recruitment (neutrophils, lymphocytes and eosinophils), bronchiolitis, enhanced cytokine gene expression, enhanced responsiveness to experimental challenge (cigarette smoke exposure, allergic inflammation) and airways hyperresponsiveness. These viral infections are particularly effective at altering nerve function in the airways of guinea pigs [72,231]. This may also be relevant to the pathogenesis of viral infections in human subjects [225,232].

3.5. Ozone

Ozone challenge has been used in human subjects and in animals to evoke an inflammatory response in the airways. Ozone produces an acute inflammatory response in the airways of guinea pigs along with a short-lived hyperresponsiveness to bronchoconstricting stimuli [233-235]. The acute inflammatory response to ozone is similar in human subjects and in guinea pigs, with an immediate influx of neutrophils and a coincident vascular leak as measured by serum constituents (urea, albumin) in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid [234,236-238]. More recent studies have documented an eosinophilia in the airways of guinea pigs and asthmatic subjects following ozone exposure [148,238-240]. Prostanoids may mediate some of the acute physiologic effects of ozone exposure, as they have been recovered in lavage and serum of ozone exposed guinea pigs and human subjects [241-243]. Ozone also acts in part on airway nerves to initiate airways hyperresponsiveness in human subjects and in guinea pigs [148,234,244]. Comparable inflammatory and physiologic effects in humans and in guinea pigs have been reported in studies with the occupational toxin toluene diisocyanate [245-249].

4. Pharmacology and therapeutic interventions

4.1. Receptor pharmacology

With few exceptions, the pharmacology of metabotropic and ionotropic receptors relevant to asthma and COPD is nearly identical in human and guinea pig airway preparations. Even more complex regulators of cell function related to neuronal and mast cell activation, second messenger formation and metabolism, and cytokine gene expression are nearly identical in these two species [20,21,35,37,73-77,83-86,94-97,101-103,108,109,143,145,-194]. The rank order of potency for airway smooth muscle contractile and relaxant agonists is nearly identical in guinea pigs and humans. Similarly, the rank order of potency of antagonists for these various receptors in guinea pigs predicts with nearly perfect fidelity the rank order of potency of these antagonists in the human airway (Table 1, Fig. 1).

Exceptions to the predictive value of guinea pig airway receptor pharmacology for that of humans include the expression of a cysLT2-like leukotriene receptor on guinea pig airway smooth muscle but not on human airway smooth muscle, and the expression of neurokinin1 receptors and contractile prostanoid EP1 receptors on the airway smooth muscle in guinea pigs but not in human airway smooth muscle [19,55,57,250-253]. Serotonin also contracts guinea pig (and mouse and rat) airway smooth muscle but not that of humans [21]. In human pulmonary vessels, a cysLT2-like receptor regulates several vascular endothelial functions [254]. This is not observed in guinea pig pulmonary vessels, where most effects are attributable to a homogeneous population of cysLT1 receptors [255]. Despite these exceptions, the utility of guinea pig airway preparations for pharmacological analyses relevant to asthma and COPD pathogenesis and therapy far exceeds that of mice or rats. Many contractile agonists considered relevant to the pathogenesis of asthma have no effect on murine (or rat) airway smooth muscle or are bronchodilators in mice and rats [21,79,80,129-131,256-258]. As mentioned previously, mouse and rat airway smooth muscle has no direct relaxant innervation [79,80]. Moreover, the beta adrenoceptors mediating airway smooth muscle relaxation in mice are the beta1 subtype, not the beta2 subtype as it is entirely in human and primarily in guinea pig airways [259]. Receptor agonist and antagonist potency and efficacy in rats and mice are also known to differ from that in humans, prompting some researchers to develop transgenic mice expressing human receptors [260-270]. This renders the mouse of limited utility in preclinical studies of many classes of therapeutic interventions designed for treating asthma and COPD.

4.2. Therapeutic interventions in experimental challenges

The guinea pig has had excellent predictive value for the effects of therapeutics used in the treatment of asthma and COPD. This includes therapeutics with established efficacy in human disease (β2 adrenoceptor agonists, anticholinergics, PDE inhibitors, steroids, cysLT1 recceptor antagonists, 5-lipoxygenase/five lipoxygenase activating protein (FLAP) inhibitors) and therapeutics with modest or no beneficial effects in human disease, including anti-IL-5 antibodies, anti-TNF antibodies, and bradykinin, histamine, thromboxane and PAF receptor antagonists [9,10,20,21,35,48,60,65,82,85-87,91,94,95,103,115,119,120,124,141,143,146,147,154-156,158,162-166,191,192,194-197,204,271-278]. A notable exception to this has been the many reports in guinea pigs showing beneficial effects of neurokinin receptor antagonists (see below). Therapeutics contra-indicated in human subjects with asthma and/or COPD including propranolol, ACE inhibitors and cyclooxygenase inhibitors have been shown to similarly exacerbate airway responses in guinea pigs [62,185,186,202,278-285].

The results of the studies in guinea pigs with therapeutics that provided only modest benefit in clinical trials in asthma deserve further discussion, as these studies could be misinterpreted as evidence that the guinea pig and other animal models have had poor predictive value for human disease. This has rarely been the case. Rather, it has been the interpretation of the results that has probably been incorrect. Implicit in many studies carried out in animals for much of the past 20 years has been the assumption that therapeutics that can prevent airways eosinophilia and the modest shifts in airways reactivity produced following one or several (rarely more than three) allergen challenges would be beneficial in asthma. It is now abundantly clear that the presence of eosinophils in the airways is neither sufficient nor necessary for producing asthma. It is also clear that while most asthmatics are allergic, only a minority of allergic patients develop asthma. This makes the typical model of allergic asthma in animals of questionable relevance or similarity to the disease asthma. In this light, studies in guinea pigs were highly predictive of the effects of therapeutics such as anti-IL-5 and PAF receptor antagonists in human subjects. Both IL-5 and PAF are potent eosinophil chemoattractants, and blockers of both reduced airways eosinophilia evoked by allergen challenge.

5. Drawbacks

5.1. Axon reflex

The pioneering work of Lundberg and others showing that activation of the peripheral terminals of capsaicin sensitive nerves in the airways of rats and guinea pigs results in local tachykinin (substance P and neurokinin A) release that subsequently induce many of the characteristic features of asthma (bronchospasm, mucus secretion, vascular engorgement, plasma extravasation, inflammatory cell recruitment) lead to nearly two decades of intensive research into the role of the axon reflex in airways disease [35,286,287]. These studies revealed that tachykinin and capsaicin receptor pharmacology is very similar in human and guinea pig airways, and in both species tachykinins are metabolized in the lung by neutral endopeptidase [253,288-291]. Despite many important and fundamental discoveries relating to afferent nerve excitability, the axon reflex and tachykinin and capsaicin receptor pharmacology, it now seems likely that the axon reflex as it manifests in the lungs of guinea pigs and rats is not present in the human lung. This perhaps more than any other feature of the airways and lungs of guinea pigs is the greatest drawback to using guinea pigs to model asthma and COPD. The axon reflex seems to be relevant to every response of the guinea pig lung to experimental insults and challenges [190,206,245,248,286,287,292-294]. Given its profound influence over the airways of guinea pigs and the likely limited role of the axon reflex on human airway function, it seems imperative that the actions of peripherally released tachykinins in the airways of guinea pigs be considered and if possible blocked pharmacologically to minimize their effects when modeling asthma and/or COPD.

5.2. Genetics

There are no published reports describing transgenic guinea pigs and given their gestation time (60–75 days) relative to that of mice (20–30 days), their smaller average litter size (4 vs. ≥7) and the maximum number of litters/ year (5 vs. 10), it seems unlikely that transgenic strains of guinea pigs will be available in the foreseeable future. Far less of the genome of guinea pigs is currently known relative to that of the mouse as well and this will limit discovery of the function of novel genes in the guinea pig and might limit the ability to monitor expression of known genes in response to experimental interventions. There are also very few strains of guinea pigs available for research. But many genes relevant to the pathogenesis of asthma and COPD have been cloned from guinea pigs (Tables 2 and 3). More recently, inflammation/infection related microarrays have been developed and validated to some extent in guinea pigs. Immunohistochemical and flow cytometric analyses are also possible in guinea pigs and siRNA gene silencing and adenoviral gene transfection have been used in guinea pigs [295-303].

Table 2.

Cloned and characterized guinea pig genes: autacoid and nerve related genes relevant to asthma and COPD

| Guinea pig | Human homolog | |

|---|---|---|

| Autacoid-related Genes | ||

| Histamine H1 receptor | [335,336] | [337] |

| Histamine H3 receptor | [338] | [339] |

| Histamine H4 receptor | [340] | [341] |

| Cyclooxygenase-2 | [342] | [343] |

| Prostanoid CRTH2 receptor | [344] | [345] |

| PAF receptor | [346] | [347] |

| PAF acetyl hydrolase | [348] | [349] |

| Leukotriene BLT receptor | [350,351] | [352] |

| Plasma prekallikrein | [353] | [354] |

| Bradykinin B2 receptor | [355] | [268] |

| Complement C3a receptor | [356] | [357] |

| Complement C3b receptor | [358] | [359] |

| Complement C5a receptor | [360] | [361] |

| Adenosine A1 receptor | [362] | [363] |

| Adenosine A2 receptor | [364] | [365] |

| 5-HT3 receptor | [366] | [367,368] |

| 5-HT transporter | [369] | [370] |

| Inducible NO synthase | [371] | [372] |

| Nerve-related genes | ||

| Nerve growth factor | [373] | [374] |

| β2-Adrenoceptor | [375] | [376] |

| VPAC2 receptor | [377] | [378] |

| NK1 receptor | [379] | [380] |

| NK2 receptor | [324] | [381] |

| NK3 receptor | [382] | [383] |

| TRPV1 | [290] | [291] |

| Preproenkephalin | [384] | [385] |

| μ-opioid receptor | [386] | [387] |

| Sigma1 receptor | [388] | [389] |

The lists of cloned guinea pig genes relevant to asthma and COPD that are summarized in Tables 2 and 3 were generated from PubMed journal and nucleotide databases. Unpublished sequences of many more guinea pig genes relevant to asthma and COPD are reported on the nucleotide database, including the genes for all 5 muscarinic receptors, both cysteinyl–leukotriene receptors, 4 NPY/peptide YY/pancreatic polypeptide receptors, 3 preprotachykinin genes, and various ion pumps and exchangers and sodium, potassium and chloride channels

Table 3.

Cloned and characterized guinea pig genes: immunity related and other miscellaneous genes relevant to asthma and COPD

| Guinea pig | Human homolog | |

|---|---|---|

| Cytokine and lymphocyte related genes | ||

| Interferon gamma | [390] | [391] |

| Interleukin-2 | [392] | [393] |

| Interleukin-5 | [394,395] | [396] |

| Interleukin-5 receptor | [397] | [398] |

| Interleukin-10 | [392] | [399] |

| Interleukin-12 | [400] | [401] |

| Tumor necrosis factor | [174] | [402] |

| CD1 | [403] | [404] |

| T-cell receptor | [405] | [406] |

| CD8α+β | [407] | [408,409] |

| FcGammaRI, RII, RIII | [410,411] | [412-414] |

| Chemokine, neutrophil and eosinophil-related genes | ||

| Eotaxin | [12,13] | [415] |

| Interleukin-8 | [416] | [417] |

| CCL5 (RANTES) | [418,419] | [420] |

| MCP-1 | [421] | [422] |

| GRO | [423] | [424] |

| Interleukin-8 receptor(s) | [425,426] | [427] |

| CCR3 receptor | [169] | [428] |

| CCR4 receptor | [429] | [430] |

| Major basic protein | [431] | [432] |

| Miscellaneous genes relevant to airways disease | ||

| VEGF | [5] | [14] |

| TGF-β | [392] | [433] |

| Surfactant protein-A | [434] | [435] |

| Alpha1-antitrypsin | [436] | [437] |

| MUC2 | [438] | [439] |

| MUC5AC | [438] | [440] |

| Glucocorticoid receptor | [441] | [442] |

| TIMP-2 | [443] | [444] |

| PPAR gamma | [445] | [446] |

Unpublished sequences of other immune-related genes relevant to asthma and COPD that are reported on the PubMed nucleotide database include various integrins and CD markers for immune cells as well as MCP-3

5.3. Cardiovascular system

Guinea pigs have been domesticated for centuries but were endemic to high altitude locations in South and Central America. Perhaps as an adaptation to this environment, guinea pigs have a remarkably low mean arterial blood pressure (30–50mmHg) relative to that of humans and other commonly used species (80–100mmHg) and are thus far more susceptible to cardiovascular collapse, as in anaphylaxis [2,141,292]. The guinea pig pulmonary circulation also responds only modestly to hypoxia, with a slight elevation in pulmonary arterial pressure relative to the response of humans, pigs or rats [304]. The extensive peptidergic afferent innervation of the bronchial vasculature and the axon reflex also makes the guinea pig particularly susceptible to a profound neurogenic inflammation, with coincident leukocyte recruitment, bronchospasm, vasodilatation, increased airway epithelial and endothelial permeability and mucus secretion. The axon reflex may be precipitated by changes in blood oxygen or carbon dioxide concentrations or pH [293,294,305].

5.4. Airways hyperresponsiveness

The key elements of the lung that regulate airways responsiveness—the airway smooth muscle, the innervation of the airways and lungs, the mast cells and the epithelium—function similarly in humans and in guinea pigs. As with all animals, however, models of human airways hyperresponsiveness in guinea pigs are woefully inadequate [1,306]. Key to quantifying airways hyperresponsiveness are the peculiarities of the forced expiratory maneuver [307]. There is no comparable respiratory maneuver in guinea pigs. Relative to other species, the guinea pig is considered “hyperresponsive” even at baseline, given their tendency to constrict excessively, leading to airway closure, gas trapping and ultimately collapse [308]. In vitro studies of guinea pig airway smooth muscle responsiveness do not support the notion that the guinea pig is uniquely responsive to contractile agonists. On the contrary, guinea pig airway smooth muscle closely resembles human airway smooth muscle (Fig. 1, Table 1). This latter observation is not surprising, given that smooth muscle from asthmatics studied in vitro show few if any signs of “hyperresponsiveness” [1]. Rather, the hyperresponsiveness in asthma and apparently in guinea pigs is only manifest within the context of the intact lung.

6. Conclusions

Guinea pigs offer many advantages in preclinical studies relevant to asthma and COPD. Receptor pharmacology in guinea pigs closely resembles that of the human airway. The airway response to allergen challenge is very similar to that of the human airways and very different from that of the mouse. The autonomic innervation of guinea pig airways is also very similar to that in humans. The responses to experimental interventions in guinea pigs parallel the responses seen in human subjects. These advantages are more significant than the several disadvantages, which include a prominent axon reflex in the airways, limited prospects for transgenic animals and few sufficiently different strains for comparative studies. As with all animal models, guinea pig models of airways hyperresponsiveness are inadequate. But the key elements of the airway that determine airways reactivity function similarly in humans and in guinea pigs.

References

- 1.Canning BJ. Modeling asthma and COPD in animals: a pointless exercise? Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2003;3:244–50. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4892(03)00045-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Auer J, Lewis PA. The physiology of the immediate reaction of anaphylazis in the guinea pig. J Exp Med. 1910;12:151–75. doi: 10.1084/jem.12.2.151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brocklehurst WE. The release of histamine and formation of a slow-reacting substance (SRS-A) during anaphylactic shock. J Physiol. 1960;151:416–35. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1960.sp006449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burgess GM, Godfrey PP, McKinney JS, Berridge MJ, Irvine RF, Putney JW., Jr The second messenger linking receptor activation to internal Ca release in liver. Nature. 1984;309:63–6. doi: 10.1038/309063a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Connolly DT, Heuvelman DM, Nelson R, Olander JV, Eppley BL, Delfino JJ, et al. Tumor vascular permeability factor stimulates endothelial cell growth and angiogenesis. J Clin Invest. 1989;84:1470–8. doi: 10.1172/JCI114322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dale HH. The anaphylactic reaction of plain muscle in the guinea pig. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1913;4:167–223. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dale HH, Laidlaw PP. The physiological action of beta-iminazolylethylamine. J Physiol. 1910;41:318–44. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1910.sp001406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Vries C, Escobedo JA, Ueno H, Houck K, Ferrara N, Williams LT. The fms-like tyrosine kinase, a receptor for vascular endothelial growth factor. Science. 1992;255:989–91. doi: 10.1126/science.1312256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Farmer JB, Kennedy I, Levy GP, Marshall RJ. A comparison of the beta-adrenoreceptor stimulant properties of isoprenaline, with those of orciprenaline, salbutamol, soterenol and trimetoquinol on isolated atria and trachea of the guinea pig. J Pharm Pharmacol. 1970;22:61–3. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1970.tb08388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hartley D, Jack D, Lunts LH, Ritchie AC. New class of selective stimulants of beta-adrenergic receptors. Nature. 1968;219:861–2. doi: 10.1038/219861a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hunninghake GW, Gallin JI, Fauci AS. Immunologic reactivity of the lung: the in vivo and in vitro generation of a neutrophil chemotactic factor by alveolar macrophages. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1978;117:15–23. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1978.117.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jose PJ, Adcock IM, Griffiths-Johnson DA, Berkman N, Wells TN, Williams TJ, et al. Eotaxin: cloning of an eosinophil chemoattractant cytokine and increased mRNA expression in allergen-challenged guinea-pig lungs. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1994;205:788–94. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.2734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jose PJ, Griffiths-Johnson DA, Collins PD, Walsh DT, Moqbel R, Totty NF, et al. Eotaxin: a potent eosinophil chemoattractant cytokine detected in a guinea pig model of allergic airways inflammation. J Exp Med. 1994;179:881–7. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.3.881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Keck PJ, Hauser SD, Krivi G, Sanzo K, Warren T, Feder J, et al. Vascular permeability factor, an endothelial cell mitogen related to PDGF. Science. 1989;246:1309–12. doi: 10.1126/science.2479987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lands AM, Arnold A, McAuliff JP, Luduena FP, Brown TG., Jr Differentiation of receptor systems activated by sympathomimetic amines. Nature. 1967;214:597–8. doi: 10.1038/214597a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Piper PJ, Vane JR. Release of additional factors in anaphylaxis and its antagonism by anti-inflammatory drugs. Nature. 1969;223:29–35. doi: 10.1038/223029a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Robison GA, Butcher RW, Sutherland EW. Cyclic AMP Annu Rev Biochem. 1968;37:149–74. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.37.070168.001053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schultz WH. Physiological studies in anaphylaxis. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1910;9:181–7. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Snyder DW, Krell RD. Pharmacological evidence for a distinct leukotriene C4 receptor in guinea-pig trachea. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1984;231:616–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Muccitelli RM, Tucker SS, Hay DW, Torphy TJ, Wasserman MA. Is the guinea pig trachea a good in vitro model of human large and central airways? Comparison on leukotriene-, methacholine-, histamine- and antigen-induced contractions. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1987;243:467–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ressmeyer AR, Larsson AK, Vollmer E, Dahlen SE, Uhlig S, Martin C. Characterisation of guinea pig precision-cut lung slices: comparison with human tissues. Eur Respir J. 2006;28:603–11. doi: 10.1183/09031936.06.00004206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Amdur MO, Mead J. Mechanics of respiration in unanesthetized guinea pigs. Am J Physiol. 1958;192:364–8. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1958.192.2.364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pennock BE, Cox CP, Rogers RM, Cain WA, Wells JH. A noninvasive technique for measurement of changes in specific airway resistance. J Appl Physiol. 1979;46:399–406. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1979.46.2.399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Silbaugh SA, Mauderly JL. Noninvasive detection of airway constriction in awake guinea pigs. J Appl Physiol. 1984;56:1666–9. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1984.56.6.1666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Iijima H, Ishii M, Yamauchi K, Chao CL, Kimura K, Shimura S, et al. Bronchoalveolar lavage and histologic characterization of late asthmatic response in guinea pigs. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1987;136:922–9. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/136.4.922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hutson PA, Church MK, Clay TP, Miller P, Holgate ST. Early and late-phase bronchoconstriction after allergen challenge of non-anesthetized guinea pigs. I. The association of disordered airway physiology to leukocyte infiltration. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1988;137:548–57. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/137.3.548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meurs H, Santing RE, Remie R, van der Mark TW, Westerhof FJ, Zuidhof AB, et al. A guinea pig model of acute and chronic asthma using permanently instrumented and unrestrained animals. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:840–7. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Persson CG, Erjefalt JS, Korsgren M, Sundler F. The mouse trap. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1997;18:465–7. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(97)01142-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Persson CG. Con: mice are not a good model of human airway disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166:6–7. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2204001. discussion 8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hughes T. Microcirculation of the tracheobronchial tree. Nature. 1965;206:425–6. doi: 10.1038/206425a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dalen H. An ultrastructural study of the tracheal epithelium of the guinea-pig with special reference to the ciliary structure. J Anat. 1983;136:47–67. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Poblete MT, Garces G, Figueroa CD, Bhoola KD. Localization of immunoreactive tissue kallikrein in the seromucous glands of the human and guinea-pig respiratory tree. Histochem J. 1993;25:834–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jeffery PK. Structural, immunological and neural elements of the normal human airway wall. Oxford: Blackwell; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rogers DF. Motor control of airway goblet cells and glands. Respir Physiol. 2001;125:129–44. doi: 10.1016/s0034-5687(00)00209-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Canning BJ. Reflex regulation of airway smooth muscle tone. J Appl Physiol. 2006;101:971–85. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00313.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jeffery PK. Remodeling in asthma and chronic obstructive lung disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164:S28–38. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.supplement_2.2106061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Canning BJ, Mori N, Mazzone SB. Vagal afferent nerves regulating the cough reflex. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2006;152:223–42. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2006.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu YC, Khawaja AM, Rogers DF. Effects of the cysteinyl leukotriene receptor antagonists pranlukast and zafirlukast on tracheal mucus secretion in ovalbumin-sensitized guinea-pigs in vitro. Br J Pharmacol. 1998;124:563–71. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Miodonski A, Kus J, Tyrankiewicz R. Scanning electron micro-scopical study of tracheal vascularization in guinea pig. Arch Otolaryngol. 1980;106:31–7. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1980.00790250033007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tanaka H, Yamada G, Saikai T, Hashimoto M, Tanaka S, Suzuki K, et al. Increased airway vascularity in newly diagnosed asthma using a high-magnification bronchovideoscope. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;168:1495–9. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200306-727OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pack RJ, Al-Ugaily LH, Widdicombe JG. The innervation of the trachea and extrapulmonary bronchi of the mouse. Cell Tissue Res. 1984;238:61–8. doi: 10.1007/BF00215145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Choi HK, Finkbeiner WE, Widdicombe JH. A comparative study of mammalian tracheal mucous glands. J Anat. 2000;197(Part 3):361–72. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-7580.2000.19730361.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Widdicombe JH, Chen LL, Sporer H, Choi HK, Pecson IS, Bastacky SJ. Distribution of tracheal and laryngeal mucous glands in some rodents and the rabbit. J Anat. 2001;198:207–21. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-7580.2001.19820207.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Adriaensen D, Brouns I, Pintelon I, De Proost I, Timmermans JP. Evidence for a role of neuroepithelial bodies as complex airway sensors: comparison with smooth muscle-associated airway receptors. J Appl Physiol. 2006;101:960–70. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00267.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cutz E, Jackson A. Neuroepithelial bodies as airway oxygen sensors. Respir Physiol. 1999;115:201–14. doi: 10.1016/s0034-5687(99)00018-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Van Lommel A, Lauweryns JM. Postnatal development of the pulmonary neuroepithelial bodies in various animal species. J Auton Nerv Syst. 1997;65:17–24. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1838(97)00030-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Weichselbaum M, Sparrow MP, Hamilton EJ, Thompson PJ, Knight DA. A confocal microscopic study of solitary pulmonary neuroendocrine cells in human airway epithelium. Respir Res. 2005;6:115. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-6-115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gosens R, Bos IS, Zaagsma J, Meurs H. Protective effects of tiotropium bromide in the progression of airway smooth muscle remodeling. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171:1096–102. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200409-1249OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li D, Wang D, Griffinths-Johnson DA, Wells TN, Williams TJ, Jose PJ, et al. Eotaxin protein and gene expression in guinea pig lungs: constitutive expression and upregulation after allergen challenge. Eur Respir J. 1997;10:1946–54. doi: 10.1183/09031936.97.10091946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ghaffar O, Hamid Q, Renzi PM, Allakhverdi Z, Molet S, Hogg JC, et al. Constitutive and cytokine-stimulated expression of eotaxin by human airway smooth muscle cells. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159:1933–42. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.159.6.9805039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ellis JL, Undem BJ. Role of cysteinyl-leukotrienes and histamine in mediating intrinsic tone in isolated human bronchi. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;149:118–22. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.149.1.8111568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Orehek J, Douglas JS, Bouhuys A. Contractile responses of the guinea-pig trachea in vitro: modification by prostaglandin synthesisinhibiting drugs. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1975;194:554–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lambley JE, Smith AP. The effects of arachidonic acid, indomethacin and SC-19220 on guinea-pig tracheal muscle tone. Eur J Pharmacol. 1975;30:148–53. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(75)90093-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Charette L, Misquitta C, Guay J, Reindeau D, Jones TR. Involvement of cyclooxygenase 2 (COX-2) in intrinsic tone of isolated guinea pig trachea. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1995;73:1561–7. doi: 10.1139/y95-215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ndukwu IM, White SR, Leff AR, Mitchell RW. EP1 receptor blockade attenuates both spontaneous tone and PGE2-elicited contraction in guinea pig trachealis. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:L626–33. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1997.273.3.L626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ellis JL, Conanan ND. Prejunctional inhibition of cholinergic responses by prostaglandin E2 in human bronchi. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1996;154:244–6. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.154.1.8680688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Clarke DL, Belvisi MG, Smith SJ, Hardaker E, Yacoub MH, Meja KK, et al. Prostanoid receptor expression by human airway smooth muscle cells and regulation of the secretion of granulocyte colonystimulating factor. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2005;288:L238–50. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00313.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ellis JL, Undem BJ. Role of peptidoleukotrienes in capsaicinsensitive sensory fibre-mediated responses in guinea-pig airways. J Physiol. 1991;436:469–84. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.McAlexander MA, Myers AC, Undem BJ. Inhibition of 5-lipoxygenase diminishes neurally evoked tachykinergic contraction of guinea pig isolated airway. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1998;285:602–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Impens N, Reiss TF, Teahan JA, Desmet M, Rossing TH, Shingo S, et al. Acute bronchodilation with an intravenously administered leukotriene D4 antagonist, MK-679. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1993;147:1442–6. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/147.6_Pt_1.1442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mazzone SB, Canning BJ. An in vivo guinea pig preparation for studying the autonomic regulation of airway smooth muscle tone. Auton Neurosci. 2002;99:91–101. doi: 10.1016/s1566-0702(02)00053-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Szczeklik A, Sanak M. The broken balance in aspirin hypersensitivity. Eur J Pharmacol. 2006;533:145–55. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2005.12.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Roffel AF, Elzinga CR, Zaagsma J. Muscarinic M3 receptors mediate contraction of human central and peripheral airway smooth muscle. Pulm Pharmacol. 1990;3:47–51. doi: 10.1016/0952-0600(90)90009-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ten Berge RE, Roffel AF, Zaagsma J. The interaction of selective and non-selective antagonists with pre- and postjunctional muscarinic receptor subtypes in the guinea pig trachea. Eur J Pharmacol. 1993;233:279–84. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(93)90062-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Takahashi T, Belvisi MG, Patel H, Ward JK, Tadjkarimi S, Yacoub MH, et al. Effect of Ba 679 BR, a novel long-acting anticholinergic agent, on cholinergic neurotransmission in guinea pig and human airways. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;150:1640–5. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.150.6.7952627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Haddad EB, Patel H, Keeling JE, Yacoub MH, Barnes PJ, Belvisi MG. Pharmacological characterization of the muscarinic receptor antagonist, glycopyrrolate, in human and guinea-pig airways. Br J Pharmacol. 1999;127:413–20. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Preuss JM, Goldie RG. Muscarinic cholinoceptor subtypes mediating tracheal smooth muscle contraction and inositol phosphate generation in guinea pig and rat. Eur J Pharmacol. 1999;372:269–77. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(99)00213-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gross NJ, Skorodin MS. Role of the parasympathetic system in airway obstruction due to emphysema. N Engl J Med. 1984;311:421–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198408163110701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Molfino NA, Slutsky AS, Julia-Serda G, Hoffstein V, Szalai JP, Chapman KR, et al. Assessment of airway tone in asthma. Comparison between double lung transplant patients and healthy subjects. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1993;148:1238–43. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/148.5.1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kesler BS, Canning BJ. Regulation of baseline cholinergic tone in guinea-pig airway smooth muscle. J Physiol. 1999;518(Part 3):843–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.0843p.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Minette PA, Barnes PJ. Prejunctional inhibitory muscarinic receptors on cholinergic nerves in human and guinea pig airways. J Appl Physiol. 1988;64:2532–7. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1988.64.6.2532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Fryer AD, Jacoby DB. Parainfluenza virus infection damages inhibitory M2 muscarinic receptors on pulmonary parasympathetic nerves in the guinea-pig. Br J Pharmacol. 1991;102:267–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1991.tb12164.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Patel HJ, Barnes PJ, Takahashi T, Tadjkarimi S, Yacoub MH, Belvisi MG. Evidence for prejunctional muscarinic autoreceptors in human and guinea pig trachea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;152:872–8. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.152.3.7663798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Barnes PJ. Autonomic control of the respiratory system. Amsterdam: Harwood; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Li CG, Rand MJ. Evidence that part of the NANC relaxant response of guinea-pig trachea to electrical field stimulation is mediated by nitric oxide. Br J Pharmacol. 1991;102:91–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1991.tb12137.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ellis JL, Undem BJ. Inhibition by l-NG-nitro-l-arginine of nonadrenergic-noncholinergic-mediated relaxations of human isolated central and peripheral airway. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1992;146:1543–7. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/146.6.1543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ward JK, Barnes PJ, Springall DR, Abelli L, Tadjkarimi S, Yacoub MH, et al. Distribution of human i-NANC bronchodilator and nitric oxide-immunoreactive nerves. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1995;13:175–84. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.13.2.7542897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Fischer A, Hoffmann B. Nitric oxide synthase in neurons and nerve fibers of lower airways and in vagal sensory ganglia of man. Correlation with neuropeptides. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1996;154:209–16. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.154.1.8680682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Manzini S. Bronchodilatation by tachykinins and capsaicin in the mouse main bronchus. Br J Pharmacol. 1992;105:968–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1992.tb09086.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Szarek JL, Stewart NL, Spurlock B, Schneider C. Sensory nerveand neuropeptide-mediated relaxation responses in airways of Sprague–Dawley rats. J Appl Physiol. 1995;78:1679–87. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1995.78.5.1679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Billington CK, Penn RB. Signaling and regulation of G proteincoupled receptors in airway smooth muscle. Respir Res. 2003;4:2. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Chabot-Fletcher MC, Underwood DC, Breton JJ, Adams JL, Kagey-Sobotka A, Griswold DE, et al. Pharmacological characterization of SB 202235, a potent and selective 5-lipoxygenase inhibitor: Effects in models of allergic asthma. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1995;273:1147–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ellis JL. Role of soluble guanylyl cyclase in the relaxations to a nitric oxide donor and to nonadrenergic nerve stimulation in guinea pig trachea and human bronchus. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1997;280:1215–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ellis JL, Conanan N. l-citrulline reverses the inhibition of nonadrenergic, noncholinergic relaxations produced by nitric oxide synthase inhibitors in guinea pig trachea and human bronchus. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1994;269:1073–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Friedman BS, Bel EH, Buntinx A, Tanaka W, Han YH, Shingo S, et al. Oral leukotriene inhibitor (MK-886) blocks allergen-induced airway responses. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1993;147:839–44. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/147.4.839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Guhlmann A, Keppler A, Kastner S, Krieter H, Bruckner UB, Messmer K, et al. Prevention of endogenous leukotriene production during anaphylaxis in the guinea pig by an inhibitor of leukotriene biosynthesis (MK-886) but not by dexamethasone. J Exp Med. 1989;170:1905–18. doi: 10.1084/jem.170.6.1905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Hasday JD, Meltzer SS, Moore WC, Wisniewski P, Hebel JR, Lanni C, et al. Anti-inflammatory effects of zileuton in a subpopulation of allergic asthmatics. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161:1229–36. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.161.4.9904026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kume H, Takeda N, Oguma T, Ito S, Kondo M, Ito Y, et al. Sphingosine 1-phosphate causes airway hyper-reactivity by rhomediated myosin phosphatase inactivation. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2007;320:766–73. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.110718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Lavens-Phillips SE, Mockford EH, Warner JA. The effect of tyrosine kinase inhibitors on IgE-mediated histamine release from human lung mast cells and basophils. Inflamm Res. 1998;47:137–43. doi: 10.1007/s000110050303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Lynch OT, Giembycz MA, Daniels I, Barnes PJ, Lindsay MA. Pleiotropic role of lyn kinase in leukotriene B(4)-induced eosinophil activation. Blood. 2000;95:3541–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Malo PE, Bell RL, Shaughnessy TK, Summers JB, Brooks DW, Carter GW. The 5-lipoxygenase inhibitory activity of zileuton in in vitro and in vivo models of antigen-induced airway anaphylaxis. Pulm Pharmacol. 1994;7:73–9. doi: 10.1006/pulp.1994.1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Peachell PT, Undem BJ, Schleimer RP, MacGlashan DW, Jr, Lichtenstein LM, Cieslinski LB, et al. Preliminary identification and role of phosphodiesterase isozymes in human basophils. J Immunol. 1992;148:2503–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Seow CJ, Chue SC, Wong WS. Piceatannol, a Syk-selective tyrosine kinase inhibitor, attenuated antigen challenge of guinea pig airways in vitro. Eur J Pharmacol. 2002;443:189–96. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(02)01534-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Torphy TJ. Phosphodiesterase isozymes: molecular targets for novel antiasthma agents. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;157:351–70. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.157.2.9708012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Underwood DC, Osborn RR, Kotzer CJ, Adams JL, Lee JC, Webb EF, et al. SB 239063, a potent p38 MAP kinase inhibitor, reduces inflammatory cytokine production, airways eosinophil infiltration, and persistence. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2000;293:281–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Salari H, Yeung M, Howard S, Schellenberg RR. Increased contraction and inositol phosphate formation of tracheal smooth muscle from hyperresponsive guinea pigs. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1992;90:918–26. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(92)90464-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Marmy N, Mottas J, Durand J. Signal transduction in smooth muscle cells from human airways. Respir Physiol. 1993;91:295–306. doi: 10.1016/0034-5687(93)90107-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Janssen LJ. Ionic mechanisms and Ca(2+) regulation in airway smooth muscle contraction: do the data contradict dogma? Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2002;282:L1161–78. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00452.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Pyne NJ, Grady MW, Shehnaz D, Stevens PA, Pyne S, Rodger IW. Muscarinic blockade of beta-adrenoceptor-stimulated adenylyl cyclase: the role of stimulatory and inhibitory guanine-nucleotide binding regulatory proteins (Gs and Gi) Br J Pharmacol. 1992;107:881–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1992.tb14541.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Roffel AF, Meurs H, Elzinga CR, Zaagsma J. Muscarinic M2 receptors do not participate in the functional antagonism between methacholine and isoprenaline in guinea pig tracheal smooth muscle. Eur J Pharmacol. 1993;249:235–8. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(93)90438-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Ostrom RS, Ehlert FJ. Comparison of functional antagonism between isoproterenol and M2 muscarinic receptors in guinea pig ileum and trachea. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1999;288:969–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Sarria B, Naline E, Zhang Y, Cortijo J, Molimard M, Moreau J, et al. Muscarinic M2 receptors in acetylcholine-isoproterenol functional antagonism in human isolated bronchus. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2002;283:L1125–32. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00084.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Corompt E, Bessard G, Lantuejoul S, Naline E, Advenier C, Devillier P. Inhibitory effects of large Ca2+-activated K+ channel blockers on beta-adrenergic- and NO-donor-mediated relaxations of human and guinea-pig airway smooth muscles. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 1998;357:77–86. doi: 10.1007/pl00005141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Morin C, Sirois M, Echave V, Gomes MM, Rousseau E. Relaxing effects of 5-oxo-ETE on human bronchi involve BK Ca channel activation. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2007;83:311–9. doi: 10.1016/j.prostaglandins.2007.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Jones TR, Charette L, Garcia ML, Kaczorowski GJ. Interaction of iberiotoxin with beta-adrenoceptor agonists and sodium nitroprus-side on guinea pig trachea. J Appl Physiol. 1993;74:1879–84. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1993.74.4.1879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Ellis JL, Conanan ND. Effect of potassium channel blockers on relaxations to a nitric oxide donor and to nonadrenergic nerve stimulation in guinea pig trachea. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1994;271:782–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Torphy TJ, Undem BJ, Cieslinski LB, Luttmann MA, Reeves ML, Hay DW. Identification, characterization and functional role of phosphodiesterase isozymes in human airway smooth muscle. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1993;265:1213–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Fernandes LB, Ellis JL, Undem BJ. Potentiation of nonadrenergic noncholinergic relaxation of human isolated bronchus by selective inhibitors of phosphodiesterase isozymes. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;150:1384–90. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.150.5.7952568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Ellis JL, Conanan ND. Modulation of relaxant responses evoked by a nitric oxide donor and by nonadrenergic, noncholinergic stimulation by isozyme-selective phosphodiesterase inhibitors in guinea pig trachea. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1995;272:997–1004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Banner KH, Moriggi E, Da Ros B, Schioppacassi G, Semeraro C, Page CP. The effect of selective phosphodiesterase 3 and 4 isoenzyme inhibitors and established anti-asthma drugs on inflammatory cell activation. Br J Pharmacol. 1996;119:1255–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb16030.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Thirstrup S, Dahl R, Nielsen-Kudsk F. Interaction between prostaglandins and selective phosphodiesterase inhibitors in isolated guinea-pig trachea in vitro. Eur J Pharmacol. 1997;333:215–21. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(97)01145-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Bernareggi MM, Belvisi MG, Patel H, Barnes PJ, Giembycz MA. Anti-spasmogenic activity of isoenzyme-selective phosphodiesterase inhibitors in guinea-pig trachealis. Br J Pharmacol. 1999;128:327–36. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Schmidt DT, Watson N, Dent G, Ruhlmann E, Branscheid D, Magnussen H, et al. The effect of selective and non-selective phosphodiesterase inhibitors on allergen- and leukotriene C(4)-induced contractions in passively sensitized human airways. Br J Pharmacol. 2000;131:1607–18. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Undem BJ, Pickett WC, Adams GK., 3rd Antigen-induced sulfidopeptide leukotriene release from the guinea pig superfused trachea. Eur J Pharmacol. 1987;142:31–7. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(87)90650-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Adams GK, 3rd, Lichtenstein L. In vitro studies of antigen-induced bronchospasm: effect of antihistamine and SRS-A antagonist on response of sensitized guinea pig and human airways to antigen. J Immunol. 1979;122:555–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Bjorck T, Dahlen SE. Leukotrienes and histamine mediate IgE-dependent contractions of human bronchi: pharmacological evidence obtained with tissues from asthmatic and non-asthmatic subjects. Pulm Pharmacol. 1993;6:87–96. doi: 10.1006/pulp.1993.1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Dahlen SE, Hansson G, Hedqvist P, Bjorck T, Granstrom E, Dahlen B. Allergen challenge of lung tissue from asthmatics elicits bronchial contraction that correlates with the release of leukotrienes C4, D4, and E4. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1983;80:1712–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.6.1712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Evans TW, Rogers DF, Aursudkij B, Chung KF, Barnes PJ. Inflammatory mediators involved in antigen-induced airway microvascular leakage in guinea pigs. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1988;138:395–9. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/138.2.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Kusner EJ, Buckner CK, Dea DM, DeHaas CJ, Marks RL, Krell RD. The 5-lipoxygenase inhibitors ZD2138 and ZM230487 are potent and selective inhibitors of several antigen-induced guinea-pig pulmonary responses. Eur J Pharmacol. 1994;257:285–92. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(94)90140-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Lamm WJ, Lai YL, Hildebrandt J. Histamine and leukotrienes mediate pulmonary hypersensitivity to antigen in guinea pigs. J Appl Physiol. 1984;56:1032–8. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1984.56.4.1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Martin TJ, Broadley KJ. Mediators of adenosine- and ovalbumeninduced bronchoconstriction of sensitized guinea-pig isolated airways. Eur J Pharmacol. 2002;451:89–99. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(02)02197-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Nijkamp FP, Ramakers AG. Prevention of anaphylactic bronchoconstriction by a lipoxygenase inhibitor. Eur J Pharmacol. 1980;62:121–2. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(80)90489-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Redkar-Brown DG, Aharony D. Inhibition of antigen-induced contraction of guinea pig trachea by ICI 198,615. Eur J Pharmacol. 1989;165:113–21. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(89)90776-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Roquet A, Dahlen B, Kumlin M, Ihre E, Anstren G, Binks S, et al. Combined antagonism of leukotrienes and histamine produces predominant inhibition of allergen-induced early and late phase airway obstruction in asthmatics. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;155:1856–63. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.155.6.9196086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Kushnir-Sukhov NM, Brown JM, Wu Y, Kirshenbaum A, Metcalfe DD. Human mast cells are capable of serotonin synthesis and release. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;119:498–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Fink MA, Gardner CE. Anaphylaxis in guinea pig: improbability of release of serotonin in the Schultz–Dale reaction. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1958;97:554–7. doi: 10.3181/00379727-97-23803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Ali H, Leung KB, Pearce FL, Hayes NA, Foreman JC. Comparison of the histamine-releasing action of substance P on mast cells and basophils from different species and tissues. Int Arch Allergy Appl Immunol. 1986;79:413–8. doi: 10.1159/000234011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Bjorck T, Gustafsson LE, Dahlen SE. Isolated bronchi from asthmatics are hyperresponsive to adenosine, which apparently acts indirectly by liberation of leukotrienes and histamine. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1992;145:1087–91. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/145.5.1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Lulich KM, Paterson JW. An in vitro study of various drugs on central and peripheral airways of the rat: a comparison with human airways. Br J Pharmacol. 1980;68:633–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1980.tb10854.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Martin TR, Gerard NP, Galli SJ, Drazen JM. Pulmonary responses to bronchoconstrictor agonists in the mouse. J Appl Physiol. 1988;64:2318–23. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1988.64.6.2318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Yiamouyiannis CA, Stengel PW, Cockerham SL, Silbaugh SA. Effect of bronchoconstrictive aerosols on pulmonary gas trapping in the A/J mouse. Respir Physiol. 1995;102:97–104. doi: 10.1016/0034-5687(95)00044-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Eum SY, Norel X, Lefort J, Labat C, Vargaftig BB, Brink C. Anaphylactic bronchoconstriction in BP2 mice: interactions between serotonin and acetylcholine. Br J Pharmacol. 1999;126:312–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Joos GF, Pauwels RA. The in vivo effect of tachykinins on airway mast cells of the rat. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1993;148:922–6. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/148.4_Pt_1.922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Joos GF, Lefebvre RA, Bullock GR, Pauwels RA. Role of 5-hydroxytryptamine and mast cells in the tachykinin-induced contraction of rat trachea in vitro. Eur J Pharmacol. 1997;338:259–68. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(97)81929-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Fahy JV, Fleming HE, Wong HH, Liu JT, Su JQ, Reimann J, et al. The effect of an anti-IgE monoclonal antibody on the early- and late-phase responses to allergen inhalation in asthmatic subjects. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;155:1828–34. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.155.6.9196082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Ishizaka T, Tomioka H, Ishizaka K. Degranulation of human basophil leukocytes by anti-gamma E antibody. J Immunol. 1971;106:705–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Regal JF. Immunoglobulin G- and immunoglobulin E-mediated airway smooth muscle contraction in the guinea pig. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1984;228:116–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Oettgen HC, Martin TR, Wynshaw-Boris A, Deng C, Drazen JM, Leder P. Active anaphylaxis in IgE-deficient mice. Nature. 1994;370:367–70. doi: 10.1038/370367a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Miyajima I, Dombrowicz D, Martin TR, Ravetch JV, Kinet JP, Galli SJ. Systemic anaphylaxis in the mouse can be mediated largely through IgG1 and Fc gammaRIII. Assessment of the cardiopulmonary changes, mast cell degranulation, and death associated with active or IgE- or IgG1-dependent passive anaphylaxis. J Clin Invest. 1997;99:901–14. doi: 10.1172/JCI119255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Hamelmann E, Takeda K, Schwarze J, Vella AT, Irvin CG, Gelfand EW. Development of eosinophilic airway inflammation and airway hyperresponsiveness requires interleukin-5 but not immunoglobulin E or B lymphocytes. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1999;21:480–9. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.21.4.3659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Chand N, Hess FG, Nolan K, Diamantis W, McGee J, Sofia RD. Aeroallergen-induced immediate asthmatic responses and late-phase associated pulmonary eosinophilia in the guinea pig: effect of methylprednisolone and mepyramine. Int Arch Allergy Appl Immunol. 1990;91:311–4. doi: 10.1159/000235133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Cohan VL, Undem BJ, Fox CC, Adkinson NF, Jr, Lichtenstein LM, Schleimer RP. Dexamethasone does not inhibit the release of mediators from human mast cells residing in airway, intestine, or skin. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1989;140:951–4. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/140.4.951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Liu MC, Proud D, Lichtenstein LM, Hubbard WC, Bochner BS, Stealey BA, et al. Effects of prednisone on the cellular responses and release of cytokines and mediators after segmental allergen challenge of asthmatic subjects. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;108:29–38. doi: 10.1067/mai.2001.116004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Schleimer RP, Undem BJ, Meeker S, Bollinger ME, Adkinson NF, Jr, Lichtenstein LM, et al. Dexamethasone inhibits the antigen-induced contractile activity and release of inflammatory mediators in isolated guinea pig lung tissue. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1987;135:562–6. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1987.135.3.562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Toward TJ, Broadley KJ. Early and late bronchoconstrictions, airway hyper-reactivity, leucocyte influx and lung histamine and nitric oxide after inhaled antigen: effects of dexamethasone and rolipram. Clin Exp Allergy. 2004;34:91–102. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2004.01833.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Van Oosterhout AJ, Ladenius AR, Savelkoul HF, Van Ark I, Delsman KC, Nijkamp FP. Effect of anti-IL-5 and IL-5 on airway hyperreactivity and eosinophils in guinea pigs. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1993;147:548–52. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/147.3.548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Underwood DC, Osborn RR, Newsholme SJ, Torphy TJ, Hay DW. Persistent airway eosinophilia after leukotriene (LT) D4 administration in the guinea pig: modulation by the LTD4 receptor antagonist, pranlukast, or an interleukin-5 monoclonal antibody. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1996;154:850–7. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.154.4.8887574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Yost BL, Gleich GJ, Jacoby DB, Fryer AD. The changing role of eosinophils in long-term hyperreactivity following a single ozone exposure. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2005;289:L627–35. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00377.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Asano K, Nakamura M, Oguma T, Fukunaga K, Matsubara H, Shiomi T, et al. Differential expression of CCR3 ligand mRNA in guinea pig lungs during allergen-induced inflammation. Inflamm Res. 2001;50:625–30. doi: 10.1007/PL00000244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Frew AJ, Moqbel R, Azzawi M, Hartnell A, Barkans J, Jeffery PK, et al. T lymphocytes and eosinophils in allergen-induced late-phase asthmatic reactions in the guinea pig. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1990;141:407–13. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/141.2.407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Atkins PC, Valenzano M, Goetzl EJ, Ratnoff WD, Graziano FM, Zweiman B. Identification of leukotriene B4 as the neutrophil chemotactic factor released by antigen challenge from passively sensitized guinea pig lungs. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1989;83:136–43. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(89)90488-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Beeh KM, Kornmann O, Buhl R, Culpitt SV, Giembycz MA, Barnes PJ. Neutrophil chemotactic activity of sputum from patients with COPD: role of interleukin 8 and leukotriene B4. Chest. 2003;123:1240–7. doi: 10.1378/chest.123.4.1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Erin EM, Williams TJ, Barnes PJ, Hansel TT. Eotaxin receptor (CCR3) antagonism in asthma and allergic disease. Curr Drug Targets Inflamm Allergy. 2002;1:201–14. doi: 10.2174/1568010023344715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Flood-Page P, Menzies-Gow A, Phipps S, Ying S, Wangoo A, Ludwig MS, et al. Anti-IL-5 treatment reduces deposition of ECM proteins in the bronchial subepithelial basement membrane of mild atopic asthmatics. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:1029–36. doi: 10.1172/JCI17974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Hay DW. Pharmacology of leukotriene receptor antagonists. More than inhibitors of bronchoconstriction. Chest. 1997;111:35S–45S. doi: 10.1378/chest.111.2_supplement.35s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Howarth PH, Babu KS, Arshad HS, Lau L, Buckley M, McConnell W, et al. Tumour necrosis factor (TNFalpha) as a novel therapeutic target in symptomatic corticosteroid dependent asthma. Thorax. 2005;60:1012–8. doi: 10.1136/thx.2005.045260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Kraneveld AD, van Ark I, Van Der Linde HJ, Fattah D, Nijkamp FP, Van Oosterhout AJ. Antibody to very late activation antigen 4 prevents interleukin-5-induced airway hyperresponsiveness and eosinophil infiltration in the airways of guinea pigs. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1997;100:242–50. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(97)70231-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Leckie MJ, ten Brinke A, Khan J, Diamant Z, O’Connor BJ, Walls CM, et al. Effects of an interleukin-5 blocking monoclonal antibody on eosinophils, airway hyper-responsiveness, and the late asthmatic response. Lancet. 2000;356:2144–8. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)03496-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Lilly CM, Chapman RW, Sehring SJ, Mauser PJ, Egan RW, Drazen JM. Effects of interleukin 5-induced pulmonary eosinophilia on airway reactivity in the guinea pig. Am J Physiol. 1996;270:L368–75. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1996.270.3.L368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Lo SK, Everitt J, Gu J, Malik AB. Tumor necrosis factor mediates experimental pulmonary edema by ICAM-1 and CD18-dependent mechanisms. J Clin Invest. 1992;89:981–8. doi: 10.1172/JCI115681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161.Morse B, Sypek JP, Donaldson DD, Haley KJ, Lilly CM. Effects of IL-13 on airway responses in the guinea pig. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2002;282:L44–9. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00296.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162.Nabe T, Yamashita K, Miura M, Kawai T, Kohno S. Cysteinyl leukotriene-dependent interleukin-5 production leading to eosinophilia during late asthmatic response in guinea-pigs. Clin Exp Allergy. 2002;32:633–40. doi: 10.1046/j.0954-7894.2002.01329.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 163.Page CP. The role of platelet activating factor in allergic respiratory disease. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1990;30(Suppl. 1):99S–106S. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1990.tb05475.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 164.Portanova JP, Christine LJ, Rangwala SH, Compton RP, Hirsch JL, Smith WG, et al. Rapid and selective induction of blood eosinophilia in guinea pigs by recombinant human interleukin 5. Cytokine. 1995;7:775–83. doi: 10.1006/cyto.1995.0093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 165.Renzetti LM, Gater PR. Ro 45-2081, a TNF receptor fusion protein, prevents inflammatory responses in the airways. Inflamm Res. 1997;46(Suppl. 2):S143–4. doi: 10.1007/s000110050146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 166.Renzetti LM, Paciorek PM, Tannu SA, Rinaldi NC, Tocker JE, Wasserman MA, et al. Pharmacological evidence for tumor necrosis factor as a mediator of allergic inflammation in the airways. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1996;278:847–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 167.Richards IM, Griffin RL, Oostveen JA, Morris J, Wishka DG, Dunn CJ. Effect of the selective leukotriene B4 antagonist U-75302 on antigen-induced bronchopulmonary eosinophilia in sensitized guinea pigs. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1989;140:1712–6. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/140.6.1712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 168.Richman-Eisenstat JB, Jorens PG, Hebert CA, Ueki I, Nadel JA. Interleukin-8: an important chemoattractant in sputum of patients with chronic inflammatory airway diseases. Am J Physiol. 1993;264:L413–8. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1993.264.4.L413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 169.Sabroe I, Conroy DM, Gerard NP, Li Y, Collins PD, Post TW, et al. Cloning and characterization of the guinea pig eosinophil eotaxin receptor, C–C chemokine receptor-3: blockade using a monoclonal antibody in vivo. J Immunol. 1998;161:6139–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 170.Sehmi R, Cromwell O, Taylor GW, Kay AB. Identification of guinea pig eosinophil chemotactic factor of anaphylaxis as leukotriene B4 and 8(S),15(S)-dihydroxy-5,9,11,13(Z,E,Z,E)-eicosatetraenoic acid. J Immunol. 1991;147:2276–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 171.Shi HZ, Xiao CQ, Zhong D, Qin SM, Liu Y, Liang GR, et al. Effect of inhaled interleukin-5 on airway hyperreactivity and eosinophilia in asthmatics. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;157:204–9. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.157.1.9703027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 172.Tamaoki J, Nakata J, Tagaya E, Konno K. Effects of roxithromycin and erythromycin on interleukin 8-induced neutrophil recruitment and goblet cell secretion in guinea pig tracheas. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:1726–8. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.7.1726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]