SYNOPSIS

A substantial number of people living with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) have never received HIV medical care despite the benefits of early entry to care. The United States has no population-based system that can be used to estimate the number of people who have never received HIV care or to monitor the reasons that care is delayed. Although local efforts to describe unmet need and barriers to care have been informative, nationally representative data are needed to increase the number of people who enter care soon after diagnosis.

Legal requirements to report all CD4 counts and all HIV viral load levels (indicators of HIV care) in most states now make national estimates of both care entry and non-entry feasible. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and five state and local health department jurisdictions are testing and evaluating methods for a standardized supplemental HIV surveillance system to characterize HIV-infected people across the U.S. who have not entered HIV care after their diagnosis. This article reviews the context, rationale, and potential contributions of a nationally representative surveillance system to monitor delays in receiving HIV care, and provides data from the formative phase of the CDC pilot project.

Entering medical care soon after diagnosis is essential if people living with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) are to benefit from life-prolonging HIV care. The early initiation of antiretroviral therapy may reduce treatment-related complications, improve immune function, and, along with prophylaxis for opportunistic infections, reduce HIV-related morbidity and mortality.1–15 Early HIV medical care also provides additional opportunities for prevention counseling, which may reduce further HIV transmission.2,15,16 Despite the advantages of early care and a publicly funded system designed to improve access to HIV care,17 a substantial number of HIV-infected people are not receiving HIV care. Using national HIV/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) surveillance data through 2001, Fleming et al. estimated that approximately 33% of people who were aware of their HIV serostatus were not receiving ongoing HIV medical care.18

The HIV-prevention strategic plan of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) aims to increase the proportion of people who enter HIV medical care within three months after learning their diagnosis from 50% to 80%.19,20 However, the United States has no population-based system that can be used to estimate the number of people who have never received HIV care or that can be used to monitor the reasons that care is delayed. Such information would be useful to program planners in determining the resources needed to provide services to all HIV-infected people and in designing strategies to overcome barriers to HIV care.

The Never in Care (NIC) pilot project, a population-based supplement to the national surveillance system, was conceived to enumerate and describe people in the U.S. who have a diagnosis of HIV infection but who have never received HIV medical care. We review the history of efforts to quantify unmet need for HIV care, explain how the NIC project builds on these efforts, provide data from the formative phase of the pilot project, and describe the contributions that the NIC project, as a supplemental system, could potentially make to a comprehensive national HIV/AIDS surveillance system.

EFFORTS TO QUANTIFY UNMET NEED FOR HIV CARE

Requirements for assessment of unmet need

Administered by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), the Ryan White Comprehensive AIDS Resources Emergency (CARE) Act provides services to more than 500,000 people living with HIV infection in the U.S. The federal government allocates more than $2.1 billion annually for Ryan White CARE Act programs, which provide primary medical care, medications, and support services for people who would otherwise not have access. The Ryan White CARE Act was first enacted by Congress in 1990 and has been reauthorized three times—in 1996, 2000, and 2006. During this time, HRSA has expanded the requirements for reporting met and unmet need.

The Ryan White CARE Act Amendments of 2000 directed HRSA grantees to assess the needs of people living with HIV/AIDS, particularly those from disproportionately affected and historically underserved populations who are aware of their serostatus but who have yet to receive HIV-related health services.21 In 2003, HRSA introduced a framework developed by the University of California, San Francisco, for grantees to use to estimate met and unmet need. The framework called for the integration of two types of data: (1) data on a jurisdiction's population of HIV-infected people who are aware of their infection and (2) data on the number of HIV-infected people receiving care, based on laboratory reports of CD4 T-lymphocyte count and HIV viral load or the prescription of antiretroviral medications.22 Beginning in 2005, receipt of federal funding through the Ryan White CARE Act required an assessment of HIV medical care utilization.

Because of HRSA's requirement that its grantees estimate unmet need, some jurisdictions have a rich source of local data that characterize HIV-infected people who are not receiving HIV care. In addition, HRSA's Special Projects of National Significance Outreach Initiative, designed to refine and evaluate strategies to help underserved HIV-infected people access care, has provided additional data on unmet need.23 Several other studies have added to the knowledge base about unmet need and barriers to HIV care, including the HIV Cost and Services Utilization Study, a nationally representative survey of adults living with HIV receiving care in the U.S.24–38

Limitations of current data

The framework used by HRSA grantees to estimate need provides an operational definition of unmet need and allows HRSA grantees flexibility in choosing the method that is most suitable for their local laboratory reporting data. However, differing methods may limit jurisdictional comparisons of the levels of unmet need: that is, data may be more comparable within a jurisdiction than among multiple jurisdictions (especially with regard to subpopulations or trends over time).38,39 Although local efforts to describe unmet need and barriers to care have been informative, nationally representative data are needed to increase the number of people who enter care soon after diagnosis.

Research, including the national HIV Cost and Services Utilization Study described previously, has been primarily retrospective (i.e., focused on people who delayed HIV care after they had entered care). Descriptions of unmet need have tended to focus on people who made fewer than the recommended number of primary care visits or who were not prescribed antiretroviral therapy despite clinical indications. Few studies have described people who have never received HIV care, and these few studies were not population-based.40

Historically, the capacity to describe unmet need by the use of surveillance data (per the HRSA-recommended framework) has been limited by the existence of laws requiring laboratories to report results of CD4 and HIV viral load tests ordered as part of HIV medical care. However, HIV surveillance reporting requirements have evolved. In 1999, CDC recommended the national reporting of HIV diagnoses.41 In 2001, the Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists (CSTE) urged all states to improve HIV surveillance by reporting CD4 cell counts and HIV viral load.42 By 2004, laws in all 50 states mandated the reporting of HIV diagnoses, CD4 cell counts, and HIV viral load results.43 However, the specific values of CD4 cell counts and HIV viral load required to be reported differed by jurisdiction.42 For example, some states required only the reporting of CD4 cell counts and viral loads below or above a specified threshold (i.e., for CD4 counts, those potentially predictive of AIDS; for viral loads, detectable virus).

The use of CD4 cell counts and HIV viral load to estimate met and unmet need for HIV medical care necessitates the reporting of all CD4 or all HIV viral load test results, without restriction to specific values. Unless all CD4 or all HIV viral load test results are required to be reported, the presence or absence of that information is not a meaningful indicator of HIV care or the absence of HIV care.43

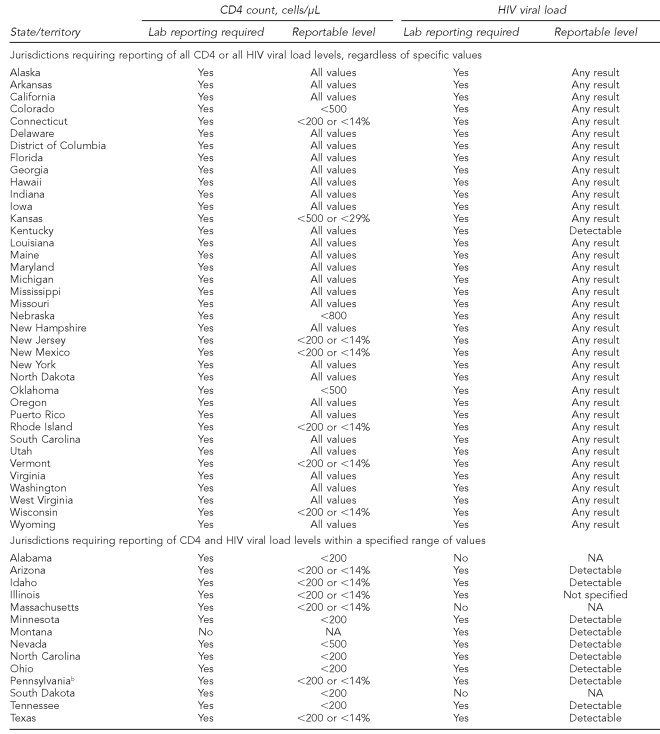

Shifts in federal policy and changes in state reporting requirements have increased the availability of data that can be used to estimate unmet need. According to the CSTE, as of 2008, 36 of the 50 states required reporting of all CD4 cell counts or all HIV viral loads, regardless of the specific values. Table 1 details state reporting requirements. As more states have removed restrictions on reportable values of CD4 cell counts and HIV viral load, the capacity to characterize unmet need by the use of routinely collected surveillance data has increased. Systematically reporting all HIV diagnoses, CD4 cell counts, and HIV viral loads is a critical step in establishing standardized national population data that can be used to estimate unmet need.

Table 1.

CD4 and HIV viral load reporting requirements as of December 2008: 50 U.S. states, Puerto Rico, and the District of Columbiaa

aCouncil of State and Territorial Epidemiologists HIV Surveillance Assessment

bAlthough state law in Pennsylvania does not require reporting of all CD4 or all HIV viral load values, city law in Philadelphia does, making Philadelphia eligible to participate in the Never in Care project.

HIV = human immunodeficiency virus

μL = micrograms/liter

NA = not applicable

THE NEVER IN CARE PROJECT

How the NIC project builds on efforts to quantify unmet need

The NIC project builds on recent shifts in policy and HIV reporting regulations that enhance the feasibility of using standardized methods for characterizing people who have never received HIV care. The purpose of the NIC pilot project is to test and evaluate methods for a supplemental HIV surveillance system to describe a particular aspect of unmet need, specifically delayed entry into HIV care. The NIC pilot is focused on HIV-infected people who received an HIV diagnosis three to 15 months before the date of selection and have never received HIV care.

Eligibility was restricted to those more recently diagnosed, because formative work indicated that project staff would be more successful in contacting these people for interviews using the available contact information, which was collected at the time of diagnosis. Although those who have never received HIV care do not represent the entire population considered by HRSA to have unmet need for HIV services,22 this population was chosen as the focus of the NIC project because there is less information about it, the population can be clearly defined, and the definition can be applied consistently across jurisdictions. A focus on HIV-infected people who have not entered HIV care allows for rigorous testing of case identification and data collection methods and provides a foundation for broadening case definitions to include not only people who have never received HIV care, but also people who have received HIV care but who are not currently in care. The NIC pilot uses HIV/AIDS surveillance data to identify the population of interest, a strategy that has the advantage of being population-based and that has been proven to be one of the most promising strategies among those promoted by HRSA's framework for assessing unmet need.44

The design of the NIC pilot addresses recommendations from the Institute of Medicine (IOM) report “Measuring What Matters: Allocation, Planning and Quality Assessment for the Ryan White CARE Act,” which urges collaboration between HRSA and CDC and other agencies to estimate the number of people who have a diagnosis of HIV infection but who are not in care,45 at least for the subpopulation of people who have never received care. After methods have been validated for characterizing people who have never received care, adjustments in the methods might be made to include people who are not receiving care consistently or as often as recommended.

Description of the pilot project and findings from formative work

CDC is funding five state and local health department jurisdictions to implement the NIC pilot from September 2005 through September 2010 to test and evaluate methods to identify, locate, and interview people reported as HIV infected three to 15 months previously, who have never received HIV medical care. Through an objective review process, Indiana, New Jersey, Washington State, New York City, and Philadelphia were selected to participate in the pilot.

The NIC pilot adheres to the confidentiality and security protections required for all HIV surveillance data. Pilot areas adhere to local regulations pertaining to locating and contacting NIC-eligible participants. People eligible for NIC are located and contacted by using information from the HIV/AIDS Reporting System (HARS) database or through physicians, HIV testing centers, or case management service providers. State laws and regulations protect surveillance information, limit the uses of data for purposes not related to public health, and impose criminal penalties for the inappropriate disclosure of surveillance data.46 Each project area has been granted a Certificate of Confidentiality, which protects the NIC data held by the state or city health department from subpoena. At the federal level, surveillance data are held under the Federal Assurance of Confidentiality, which protects data held by CDC from subpoena.47

To determine eligibility for the NIC project, pilot project areas use local HIV/AIDS case and HIV laboratory databases and, if available, supplemental databases (e.g., Ryan White Title I, Ryan White Title II, and the AIDS Drug Assistance Program). The NIC pilot criteria for identifying people who have never entered care include people who have had a diagnosis of HIV infection reported in one of the five pilot areas, are at least 90 days post-diagnosis, and have had no CD4 or HIV viral load results reported to the relevant pilot area's HIV/AIDS surveillance system. Applying these criteria by using HIV/AIDS surveillance data potentially identifies the population of HIV-infected people whose diagnosis was made during a specified eligibility period and who met the criteria for “never in care.” This population serves as a sampling frame from which to select eligible people to be approached for interview.

Contact is initiated with people selected. During the formative phase of the project, the pilot project areas conducted a trial run of sampling frame construction by identifying people who met the NIC eligibility criteria among those diagnosed between November 2005 and December 2006. These estimates represent the best available data from HARS and associated laboratory databases, before verification of never-in-care status required by the NIC project protocol. Among the 10,090 people who were diagnosed during this 12-month period and reported to HIV/AIDS surveillance systems in these areas by February 28, 2007, 2,119 (21%) had not entered care as of December 31, 2007.

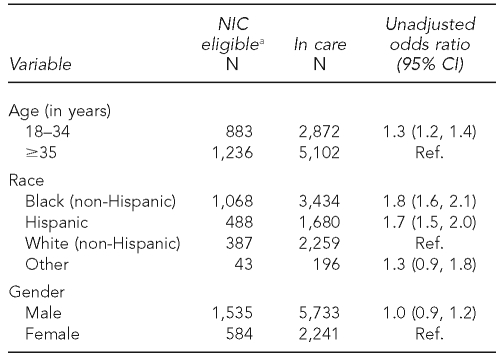

Across the pilot project areas, the percentage of people diagnosed in the 12-month period who met the NIC project definition ranged from 20% to 25%. Table 2 shows that people who met the NIC project definition were more likely to be younger, African American, and Hispanic than those diagnosed in the same period for whom there was evidence of care entry.

Table 2.

People diagnosed with HIV from November 2005 to December 2006 and reported to HIV surveillance by February 2007 in Indiana, Philadelphia, New Jersey, New York City, and Washington State

aRefers to people who have had a diagnosis of HIV infection reported in one of the five pilot areas, are at least 90 days post-diagnosis, and have had no CD4 or HIV viral load results reported to the relevant pilot area's HIV/AIDS surveillance system

HIV = human immunodeficiency virus

NIC = Never in Care

CI = confidence interval

Ref. = referent group

AIDS = acquired immunodeficiency syndrome

Percentages of people never in care derived from HARS and associated laboratory data alone are likely overestimates, because of CD4 and viral load reporting delays and because some people without evidence of care entry should not be included. As mentioned, the NIC protocol requires verification of never-in-care status. Verification is accomplished through (1) review of incoming CD4 and HIV viral load results; (2) investigation into other events, such as death or change of residence (which are associated with not having a reported CD4 or HIV viral load result, but nonetheless render a person ineligible to be counted as never in care in the jurisdiction); and (3) review of HIV counseling, testing, and partner services records containing information on whether linkage to care was successful. Those remaining eligible after this initial screening process are approached for participation and asked additional screening questions, including questions about entry to care. NIC pilot methods for identifying and interviewing eligible people have been described in more detail elsewhere.48

All five pilot areas administer a 30-minute structured interview to those determined to be eligible to describe the following: demographic characteristics, barriers to and facilitators of HIV medical care, met and unmet need for HIV-related ancillary services, social support, HIV testing history, and possible modes of exposure to HIV. Blood is collected by fingerstick and tested by a central laboratory to assess CD4 cell count and HIV viral load. In addition, four of the pilot areas (Indiana, New York City, Philadelphia, and Washington State) are conducting a 60-minute qualitative interview to allow participants to respond in their own words rather than selecting from investigator-defined responses to questions about health-care utilization, illness perception, stigma, and access to HIV information.

The five pilot areas funded to implement the NIC pilot are also participating in the Medical Monitoring Project (MMP), a supplemental HIV surveillance system that collects data on people receiving HIV medical care in the U.S.49 The MMP collects clinical and behavioral data from people receiving HIV medical care. If interview response rates are adequate, the five state and local health department jurisdictions participating in both the NIC project and the MMP should be able to assemble complementary descriptions of met and unmet need among people who are receiving HIV care and people who have never received care.

Potential contributions of national implementation of a never-in-care approach

If proven successful and implemented on a national scale, the NIC project could yield estimates of the number of HIV-infected people in the U.S. who have never accessed HIV care and could provide useful information for estimating the cost of addressing this unmet need. NIC project surveillance could be useful in developing and prioritizing strategies to increase the number of people who receive HIV care within three months of diagnosis. Such efforts are critical in addressing CDC's Advancing HIV Prevention goals of increasing access to HIV medical care and reducing HIV incidence.50

In an effort to increase the number of people who are aware of their HIV serostatus,50 CDC recommended expanding HIV testing and screening to all health-care settings.51 CDC's efforts to encourage HIV testing in nonclinical settings52 and make it routine in medical settings have increased the demand for HIV care services,17,53 but the impact of expanded testing on entry to care is unclear. Representative data on the number and characteristics of HIV-infected people who have never entered care are needed to evaluate this impact and monitor trends.

Information from the NIC project may help describe health-care access and utilization among people of minority races/ethnicities. Health-care access and utilization are often linked to socioeconomic status and race. In its 2003 report, “Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care,” the IOM described disparities in the quality of health care received by people of minority races/ethnicities.54 The NIC project is designed to uncover experiences with the health-care system that may have acted as barriers to HIV care. Such information may be useful in addressing one of the goals of CDC's HIV prevention strategic plan—to reduce the “disparities, stigma, and discrimination” that people of minority races/ethnicities may experience when accessing HIV care.20

Data on people who have never received HIV care may also provide further information for estimates of severity of need, on which HRSA bases decisions regarding allocation of Ryan White CARE Act funding for HIV-related care and support services.18 An expanded NIC project, used as a supplement to the national HIV/AIDS surveillance system, could serve as a critical tool for monitoring, evaluating, and improving initiatives so that all people with a diagnosis of HIV infection have the opportunity to initiate and continue care throughout all stages of disease.

The vision of a continuum of HIV prevention and treatment is incorporated throughout CDC's strategic plan for HIV prevention, recently extended through 2010.19,20 Achieving the benefits of prevention and treatment interventions requires optimizing each component of the continuum—from increasing the number of HIV-seronegative people who receive HIV-prevention services to increasing the numbers of people who are aware of their HIV serostatus, linking HIV-infected people to care, increasing the utilization of care and prevention services, and increasing adherence to prescribed therapies. The goals of CDC's strategic plan reflect the components of the continuum, and national HIV/AIDS surveillance activities are designed to monitor progress toward these goals: behavioral and incidence surveillance monitor progress in prevention,55 case surveillance monitors the expansion of HIV testing through reporting of new diagnoses,43 and the MMP monitors care.49 The strategic plan aims to increase the proportion of people who enter HIV medical care within three months after learning their diagnosis,20 but a mechanism to measure progress toward this goal is lacking. The NIC project, as a supplement to HIV/AIDS surveillance, could address these gaps and be a standardized system for monitoring delayed care entry.

CONCLUSIONS

Information about people who have a diagnosis of HIV infection but who are not currently in care, especially people who have never received HIV care, is limited. A supplemental surveillance system to collect data on people who have never entered HIV care would be an essential tool for uncovering patterns of HIV care utilization. Understanding the various factors that influence health-care utilization is critical to developing strategies for improving access to care for all HIV-infected people. Methods developed for the NIC pilot may contribute to a more comprehensive national HIV/AIDS surveillance system.

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate the efforts of the Never in Care (NIC) staff from the Indiana Department of Health, the New Jersey Department of Health and Senior Services, the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, the Philadelphia Department of Public Health, the Washington State Department of Health, and the Clinical Outcomes Team at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The authors are also grateful to the numerous people who contributed to the development of the NIC project, especially Barbara Bolden, Kathleen Brady, Susan Buskin, Maria Courogen, Dan Hillman, Samuel Jenness, Jim Kent, Michael Lillis, Alan Neaigus, Cheryl Pearcy, and Afework Wogayehu.

Footnotes

The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of CDC.

REFERENCES

- 1.Department of Health and Human Services (US), Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents. Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in HIV-1-infected adults and adolescents. 2009. Dec 1, [cited 2008 Nov 21]. Available from: URL: http://aidsinfo.nih.gov/contentfiles/AdultandAdolescentGL.pdf.

- 2.Chun TW, Justement JS, Moir S, Hallahan CW, Maenza J, Mullins JI, et al. Decay of the HIV reservoir in patients receiving antiretroviral therapy for extended periods: implications for eradication of virus. J Infect Dis. 2007;195:1762–4. doi: 10.1086/518250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Egger M, May M, Chene G, Phillips AN, Ledergerber B, Dabis F, et al. Prognosis of HIV-1-infected patients starting highly active antiretroviral therapy: a collaborative analysis of prospective studies. Lancet. 2002;360:119–29. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)09411-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fisher JD, Cornman DH, Osborn CY, Amico KR, Fisher WA, Friedland GA. Clinician-initiated HIV risk reduction intervention for HIV-positive persons: formative research, acceptability, and fidelity of the Options Project. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2004;37(Suppl 2):S78–87. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000140605.51640.5c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hammer SM, Saag MS, Schechter M, Montaner JS, Schooley RT, Jacobsen DM, et al. Treatment for adult HIV infection: 2006 recommendations of the International AIDS Society—USA Panel. Top HIV Med. 2006;14:827–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hisada M, O'Brien TR, Rosenberg PS, Goedert JJ. Virus load and risk of heterosexual transmission of human immunodeficiency virus and hepatitis C virus by men with hemophilia. The Multicenter Hemophilia Cohort Study. J Infect Dis. 2000;181:1475–8. doi: 10.1086/315396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaplan JE, Hanson D, Dworkin MS, Frederick T, Bertolli J, Lindegren ML, et al. Epidemiology of human immunodeficiency virus-associated opportunistic infections in the United States in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;1(30 Suppl):S5–14. doi: 10.1086/313843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lalani T, Hicks C. Does antiretroviral therapy prevent HIV transmission to sexual partners? Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2008;10:140–5. doi: 10.1007/s11908-008-0025-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lichtenstein K, Armon C, Moorman A, Buchacz K, Brooks J the HOPS Investigators. Initiation of antiretroviral therapy at higher CD4+ T cell counts reduces incidence of nucleoside analogue toxicities acutely and risk for later development with continued use of these agents in the HIV outpatient (HOPS) cohort. Presented at the 4th International AIDS Society Conference on HIV Pathogenesis, Treatment, and Prevention; 2007 Jul 22–25; Sydney, Australia. [Google Scholar]

- 10.McNaghten AD, Hanson DL, Jones JL, Dworkin MS, Ward JW. Effects of antiretroviral therapy and opportunistic illness primary chemoprophylaxis on survival after AIDS diagnosis. AIDS. 1999;13:1687–95. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199909100-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moore RD, Keruly JC. CD4+ cell count 6 years after commencement of highly active antiretroviral therapy in persons with sustained virologic suppression. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:441–6. doi: 10.1086/510746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Palella FJ, Jr, Deloria-Knoll M, Chmiel JS, Moorman AC, Wood KC, Greenberg AE, et al. Survival benefit of initiating antiretroviral therapy in HIV-infected persons in different CD4+ cell strata. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138:620–6. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-8-200304150-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Phillips AN, Gazzard BG, Clumeck N, Losso MH, Lundgren JD. When should antiretroviral therapy for HIV be started? BMJ. 2007;334:76–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39064.406389.94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Quinn TC, Wawer MJ, Sewankambo N, Serwadda D, Li C, Wabwire-Mangen F, et al. Rakai Project Study Group. Viral load and heterosexual transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:921–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200003303421303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Richardson JL, Milam J, McCutchan A, Stoyanoff S, Bolan R, Weiss J, et al. Effect of brief safer-sex counseling by medical providers to HIV-1 seropositive patients: a multi-clinic assessment. AIDS. 2004;18:1179–86. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200405210-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kamb ML, Fishbein M, Douglas JM, Jr, Rhodes F, Rogers J, Bolan G, et al. Efficacy of risk-reduction counseling to prevent human immunodeficiency virus and sexually transmitted diseases: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1998;280:1161–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.13.1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cheever LW, Lubinski C, Horberg M, Steinberg JL. Ensuring access to treatment for HIV infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45(Suppl 4):S266–74. doi: 10.1086/522549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fleming PL, Byers RH, Sweeney PA, Daniels D, Karon JM, Janssen RS. HIV prevalence in the United States, 2000; Presented at the 9th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; 2002 Feb 24–28; Seattle. [cited 2008 Nov 22]. Also available from: URL: http://www.retroconference.org/2002/abstract/13996.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US) HIV prevention strategic plan through 2005. 2001. Jan, [cited 2009 Oct 30]. Available from: URL: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/resources/reports/psp/pdf/prev-strat-plan.pdf.

- 20.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US) HIV prevention strategic plan: extended through 2010. 2007. Oct, [cited 2009 Oct 30]. Available from: URL: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/resources/reports/psp.

- 21. Ryan White CARE Act Amendments of 2000. Public Law 106-345. 106th Congress (2nd session)

- 22.Health Resources and Services Administration (US) Reauthorization letter on unmet need, 2003. [cited 2008 Nov 22]. Available from: URL: http://hab.hrsa.gov/tools/unmetneed/letter.htm.

- 23.Tobias C, Cunningham WE, Cunningham CO, Pounds MB. Making the connection: the importance of engagement and retention in HIV medical care. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2007;21(Suppl 1):S3–8. doi: 10.1089/apc.2007.9992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chesney MA, Smith AW. Critical delays in HIV testing and care. Am Behav Sci. 1999;42:1162–74. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Conviser R, Pounds MB. The role of ancillary services in client-centered systems of care. AIDS Care. 2002;14(Suppl 1):S119–31. doi: 10.1080/09540120220150018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cunningham CO, Sohler NL, Korin L, Gao W, Anastos K. HIV status, trust in health care providers, and distrust in the health care system among Bronx women. AIDS Care. 2007;19:226–34. doi: 10.1080/09540120600774263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cunningham WE, Andersen RM, Katz MH, Stein MD, Turner BJ, Crystal S, et al. The impact of competing subsistence needs and barriers on access to medical care for persons with human immunodeficiency virus receiving care in the United States. Med Care. 1999;37:1270–81. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199912000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gardner LI, Marks G, Metsch LR, Loughlin AM, O'Daniels C, del Rio C, et al. Psychological and behavioral correlates of entering care for HIV infection: the Antiretroviral Treatment Access Study (ARTAS) AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2007;21:418–25. doi: 10.1089/apc.2006.0115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Giordano TP, White AC, Jr, Sajja P, Graviss EA, Arduino RC, Adu-Oppong A, et al. Factors associated with the use of highly active antiretroviral therapy in patients newly entering care in an urban clinic. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2003;32:399–405. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200304010-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Krawczyk CS, Funkhouser E, Kilby JM, Kaslow RA, Bey AK, Vermund SH. Factors associated with delayed initiation of HIV medical care among infected persons attending a southern HIV/AIDS clinic. South Med J. 2006;99:472–81. doi: 10.1097/01.smj.0000215639.59563.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lain MA, Valverde M, Frehill LM. Late entry into HIV/AIDS medical care: the importance of past relationships with medical providers. AIDS Care. 2007;19:190–4. doi: 10.1080/09540120600970903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Meyerson BE, Klinkenberg WD, Perkins DR, Laffoon BT. Who's in and who's out: use of primary medical care among people living with HIV. Am J Public Health. 2007;97:744–9. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.090654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Montoya ID, Trevino RA, Kreitz DL. Access to HIV services by the urban poor. J Community Health. 1999;24:331–46. doi: 10.1023/a:1018730203059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Raveis VH, Siegel K, Gorey E. Factors associated with HIV-infected women's delay in seeking medical care. AIDS Care. 1998;10:549–62. doi: 10.1080/09540129848415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rumptz MH, Tobias C, Rajabiun S, Bradford J, Cabral H, Young R, et al. Factors associated with engaging socially marginalized HIV-positive persons in primary care. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2007;21(Suppl 1):S30–9. doi: 10.1089/apc.2007.9989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Samet JH, Freedberg KA, Stein MD, Lewis R, Savetsky J, Sullivan L, et al. Trillion virion delay: time from testing positive for HIV to presentation for primary care. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:734–40. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.7.734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shapiro MF, Morton SC, McCaffrey DF, Senterfitt JW, Fleishman JA, Perlman JF, et al. Variations in the care of HIV-infected adults in the United States: results from the HIV Cost and Services Utilization Study. JAMA. 1999;281:2305–15. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.24.2305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hayes C, Gambrell A, Young S, Conviser R. Using data to make decisions: planning HIV/AIDS care under the Ryan White CARE Act. AIDS Educ Prev 2005. 17(6 Suppl B):17–25. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2005.17.Supplement_B.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ikard K, Janney J, Hsu LC, Isenberg DJ, Scalco MB, Schwarcz S, et al. Estimation of unmet need for HIV primary medical care: a framework and three case studies. AIDS Educ Prev 2005. 17(6 Suppl B):26–38. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2005.17.Supplement_B.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tobias CR, Cunningham W, Cabral HD, Cunningham CO, Eldred L, Naar-King S, et al. Living with HIV but without medical care: barriers to engagement. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2007;21:426–34. doi: 10.1089/apc.2006.0138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Guidelines for national human immunodeficiency virus case surveillance, including monitoring for human immunodeficiency virus infection and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. MMWR Recomm Rep. 1999;48(RR-13):1–27. 29-31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gibson JM, Mokotoff E Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists Position Statements. Laboratory reporting of clinical test results indicative of HIV infection: new standards for a new era of surveillance and prevention. 2004. [cited 2008 Nov 22]. Available from: URL: http://www.cste.org/ps/2004pdf/04-ID-07-final.pdf.

- 43.Glynn MK, Lee LM, McKenna MT. The status of national HIV case surveillance, United States 2006. Public Health Rep. 2007;122(Suppl 1):63–71. doi: 10.1177/00333549071220S110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Perkins D, Meyerson BE, Klinkenberg D, Laffoon BT. Assessing HIV care and unmet need: eight data bases and a bit of perseverance. AIDS Care. 2008;20:318–26. doi: 10.1080/09540120701594784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Institute of Medicine, Committee on the Ryan White CARE Act. Measuring what matters: allocation, planning, and quality assessment for the Ryan White CARE Act. Washington: National Academies Press; 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gostin LO, Lazzarini Z, Flaherty KM. Legislative survey of state confidentiality laws, with specific emphasis on HIV and immunization. 2007. [cited 2008 Nov 22]. Available from: URL: http://www.epic.org/privacy/medical/cdc_survey.html.

- 47. Public Health Service Act. The Public Health and Welfare. U.S.C. Title 42 (2005)

- 48.Johnson CH, Bertolli J, Reed JB. JSM [Joint Statistical Meetings] Proceedings, Section on Statistics in Epidemiology. Alexandria (VA): American Statistical Association; 2008. Identifying and interviewing persons with a recent HIV diagnosis not yet receiving medical care; pp. 601–8. the Never in Care project. [Google Scholar]

- 49.McNaghten AD, Wolfe MI, Onorato I, Nakashima AK, Valdiserri RO, Mokotoff E, et al. Improving the representativeness of behavioral and clinical surveillance for persons with HIV in the United States: the rationale for developing a population-based approach. PloS ONE. 2007;2:e550. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Advancing HIV prevention: new strategies for a changing epidemic —United States, 2003. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2003;52(15):329–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Branson BM, Handsfield HH, Lampe MA, Janssen RS, Taylor AW, Lyss SB, et al. Revised recommendations for HIV testing of adults, adolescents, and pregnant women in health-care settings. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006;55(RR-14):1–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Revised guidelines for HIV counseling, testing and referral and revised recommendations for HIV screening of pregnant women. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2001;50(RR-19):1–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Saag MS. Opt-out testing: who can afford to take care of patients with newly diagnosed HIV infection? Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45(Suppl 4):S261–5. doi: 10.1086/522548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Institute of Medicine. Unequal treatment: confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. Washington: National Academies Press; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lee LM, McKenna MT. Monitoring the incidence of HIV infection in the United States. Public Health Rep. 2007;122(Suppl 1):72–9. doi: 10.1177/00333549071220S111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]