Abstract

Objective

To test the feasibility and effect of a smoking cessation intervention among sheltered homeless.

Methods

Homeless smokers were enrolled in a 12-week group counseling program plus pharmacotherapy (n=58).

Results

The mean number of sessions attended was 7.2, most participants used at least one type of medication (67%) and 75% completed 12-week end of treatment surveys. Carbon monoxide verified abstinence rates at 12 and 24 weeks were 15.5% and 13.6% respectively.

Conclusion

Results support the feasibility of enrolling and retaining sheltered homeless in a smoking cessation program. Counseling plus pharmacotherapy options may be effective in helping sheltered homeless smokers quit.

Keywords: smoking cessation, homeless, nicotine addiction, motivational interviewing, cognitive behavioral therapy

INTRODUCTION

National surveys indicate that 19.8% of adult Americans smoke, however among homeless people smoking rates are over 70%. 1–4 High smoking rates in this population are related to high rates of psychiatric and substance abuse disorders.5 People with these co morbid conditions are 2–4 times as likely to use tobacco as the general population. 3,6–8 Given the high rates of tobacco use, it is not surprising that homeless people are especially likely to die from tobacco-related diseases.9,10 Compared to the general population, death rates due to tobacco related cancer are twice as high among those using the shelter system. 9 In addition, the health consequences of smoking may be increased among homeless in the context of already compromised health due to poor nutrition, substance abuse, mental illness, chronic disease, and reduced access to care.3,10–13

Recent studies have found that homeless people are interested in smoking cessation and have tried to quit. In a study comparing the tobacco use characteristics of homeless and non-homeless smokers, Butler et al., found that homeless smokers had made a similar number of quit attempts in the previous year (3.6 for homeless vs. 3.5 for non homeless, p=.17) and expressed similar levels of interest in participating in a tobacco cessation program compared to non homeless.14 Another assessment of 236 homeless adults found that 72% had tried to quit at least once.2 In studies by Conner et al. and Arnsten et al., self efficacy, a previous quit attempt, and social support were associated with readiness to quit.2,15 Self efficacy was also associated with the availability of support for quitting efforts.

Despite the links between homelessness, substance abuse, mental illness, poor physical health and high rates of tobacco use, research addressing tobacco use and treatment among homeless people remains sparse. Okuyemi et al. tested two motivational interviewing (MI) treatment approaches: one targeted to smoking behaviors exclusively, and one targeted to smoking and other addictions or life events that could affect the ability to quit. In each arm of the study, participants received eight weeks of counseling plus Nicotine Replacement Therapy (NRT). At 26 weeks, the difference in cessation rates between the two study conditions (8.7% v. 17.4%) did not reach significance. The authors noted that the two treatment conditions were very similar, and the intervention may not have been of long enough duration, which may explain the lack of a significant difference in treatment effect size.16

In this study we examined the feasibility of enrolling and retaining a group of homeless clients in a 12-week smoking cessation intervention that combined group counseling based on Motivational Interviewing (MI) and Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) principles plus pharmacotherapy. We also examined the effects of the intervention on smoking abstinence rates among sheltered homeless clients living in New York City (NYC).

METHODS

Design and Procedure

The study was conducted between April 2007 and October 2008 in two sites located in NYC, one a shelter with a co-located outpatient substance abuse treatment program and the other a transitional residential treatment program for homeless clients. Both locations offer onsite psychiatric and substance abuse treatments for their clients, and serve a similar population, more than 50% of whom have a diagnosis of substance abuse and or mental illness.

We recruited clients to enroll in a one arm pilot study of 12 weeks of pharmacotherapy +MI+CBT. We also conducted baseline and 12-week surveys among 50 subjects living in the same shelter or transitional housing program who were aware of the cessation program but did not enroll.

The intervention was deployed in five waves. Each wave lasted 12 weeks (the length of the intervention) with an approximate four to six week lag between waves. Clients were recruited for three weeks prior to the start of the intervention via flyers posted at the study sites, staff referrals, and through a three-session tobacco education program presented at study sites’ community meetings and group counseling sessions. No significant differences in demographic or tobacco related variables were noted between participants from each wave.

Two masters level trained research assistants screened clients, obtained informed consent, and conducted in-person interviews at baseline, 12 and 24 weeks. Research staff read all data collection and consent forms to participants. The institutional review boards of New York University and the New York State Department of Health approved the study.

Participants

Eligible clients were male or female current smokers aged 18 and over, who smoked at least one cigarette per day, were living or receiving services at one of the study sites and were not currently receiving treatment for nicotine addiction. Carbon monoxide (CO) measurements were taken to confirm smoking status.

Using the same eligibility criteria, we also obtained consent to conduct a baseline and 12-week follow up surveys among clients participating in parallel treatment groups offered at the study sites (e.g., substance abuse treatment) but who did not choose to enroll in the intervention. This concurrent group of homeless smokers was enrolled, primarily, to assess baseline differences in attitudes about smoking and smoking characteristics between homeless smokers who chose to enroll in a program and those who did not.

Intervention

Counseling Intervention

Participants received 12, 50-minute weekly sessions of group therapy over a 12-week period that incorporated both MI and CBT principles. Both MI and CBT have been applied to smoking cessation with promising results.14,17–21 MI focuses on increasing motivation for change and consolidating commitment while CBT focuses on changing perceptions about smoking, quitting, and managing related negative moods and behaviors that may be associated with smoking and relapse. 22, 23

Groups were conducted at both study sites and were led by a licensed masters level social worker following a semi structured manual. Before the study began, the social worker attended a five day Certified Tobacco Treatment Specialist Training.24 She also received specific training on MI and CBT and was supervised weekly by the Clinical Director of Addiction Services for Project Renewal, a non-profit organization that provides medical, psychiatric and social services to homeless at several locations in New York City, including the study sites. Prior to study enrollment, the manual was pretested among 33 subjects in four separate groups, revised, and then pilot tested with one group of 10 clients.

The first three weeks of the intervention employed MI techniques that included exploring motivation and confidence for quitting, reasons for quitting, the pros and cons of smoking, the mechanism of addiction, nicotine as a drug parallel to other abused substances, and other life events that may affect motivation and confidence such as housing, lack of social support and stress. The fourth session was the quit day which included an overview of pharmacotherapy. The remaining sessions employed CBT that focused on identifying situations, activities, thoughts and moods that are associated with patterns of tobacco use, planning for trigger situations through self-monitoring exercises, rehearsing relapse prevention skills for coping with triggers and smoking urges, learning cognitive strategies to reduce negative moods and stress, role playing assertiveness to address social pressure to smoke and practicing relaxation skills.25,26 For clients who continued to demonstrate ambivalence regarding quitting, the facilitator returned to MI techniques while continuing to cover the content for those sessions.

Several components of the intervention were tailored to specific challenges revealed during the pretest phase. The structural adaptations included lengthening the intervention from 8 to 12 weeks and adding visual and experiential learning activities that provided concrete representations of the concepts covered in group. These changes addressed the need for repetition in a population with low literacy levels and high rates of cognitive impairment.27–29 The content adaptations included focusing on challenges associated with boredom and a lack of structure in daily life that is characteristic of homelessness, developing realistic alternative behaviors and pleasurable activities for this low income and often socially isolated population, and addressing other addictions.30

Pharmacotherapy

At week four of the intervention, participants who were ready to quit were offered an eight-week course of NRT (patch, gum lozenge, or inhaler), bupropion, or varenicline. Because these medications are effective in treating tobacco dependence and none have been demonstrated as more effective in this population, participants were offered a choice of medications after an overview of the proper use, benefits, and side effects associated with each.18 NRT was provided onsite in two-week supplies; doses were based on the number of cigarettes smoked per day. Bupropion and varenicline were prescribed for one month at a time. Study participants were given a prescription to obtain these medications, which are available free through the New York State Medicaid program (two three-month courses per year). Adherence was assessed through self report at each session. At the end of each session, participants were asked to recall how much medication they took (e.g., number of patches, pieces of gum per day) during the preceding 7 days.

Incentives

In return for their time and effort, we gave participants a $10 gift card after completing each assessment (i.e., 12 and 24 week surveys)

Measures

Measures of feasibility included adherence to prescribed pharmacotherapy, mean number of sessions attended and rates of survey completion at 12 and 24 weeks.

The baseline and follow-up survey questions were adapted from validated tobacco and health survey instruments and pretested during the manual development period.31 Baseline assessment included demographics, smoking and quitting history and psychosocial variables. Nicotine dependence was measured with the Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence and depression was measured with the Beck Depression Inventory.32,33 Biener and Abrams’ readiness to quit ladder was used to measure clients’ willingness to quit smoking on a scale of 1 (no interest in quitting) to 10 (has quit smoking).34 Five-point Likert scales were used to measure confidence to quit (one=very confident to five=not confident) and importance of quitting (one=very important to five=not important). Clients were also asked how much they thought smoking was affecting their health (not at all/just a little/a lot).

The primary cessation outcome measures were 12 and 24 week CO confirmed 7-day point-prevalence abstinence defined as having smoked no cigarettes for the previous seven days and confirmed by a carbon monoxide measure of 10 or less. Additional outcome measures included a quit attempt during the 12 week intervention period (yes/no) and changes in cigarettes smoked per day.

Tracking and retention

Study participants signed a release which allowed us to gather contact information from their charts at the time of enrollment. At end of treatment we updated contact information. The 12-week and 24-week follow-up surveys were scheduled to take place at the original intervention sites. If study participants were no longer at the sites, we worked with case managers or program directors to update contact information and referred to the discharge plan. Discharge plans included client housing referrals, a family or friend contact and a vocational contact. Reminder letters were sent out 4 weeks prior to the 24 week survey dates and, if there was a contact telephone number, phone calls were made 2 weeks prior to survey dates. For clients who did not have updated address or phone information or for whom the contact information was incorrect (i.e., returned letters, wrong telephone numbers), we developed additional low-intensity tracking methods, including contacting staff and attending community meetings at other service sites patronized by clients and accompanying various agency staff during home visits with clients. Staff kept a secure database with client contact data and notes on each point of contact with client or a person in contact with client. Participants received a metrocard for travel expenses.

Data analysis

We analyzed all data using Stata 10.1 (http://www.stata.com/). Standard descriptive statistics were used to summarize data collected for demographics and smoking-related characteristics. We used Fisher’s exact test (for small expected frequencies) to test associations between the cessation and quit attempts outcomes with baseline smoking characteristics, number of sessions attended, and use of pharmacotherapy. We used t-tests to examine pre and post differences among clients in cigarettes smoked per day.

We conducted smoking outcome analyses using the intention-to-treat (ITT) principle; however, we also present results from the complete case samples. The ITT sample (n=58) included all clients who completed a baseline assessment and, for the intervention group, attended at least one counseling session. For these analyses, we coded subjects lost to follow-up as not abstinent at 12 weeks, no quit attempts during the previous 12 weeks, and post-treatment CPD equivalent to baseline CPD. The complete case analysis (n=44) included only those participants who completed baseline and 12-week follow-up assessments. We report the 24-week abstinence rates using an ITT analysis as well, assuming those who were not surveyed at 24 weeks continued to smoke.

RESULTS

Subjects

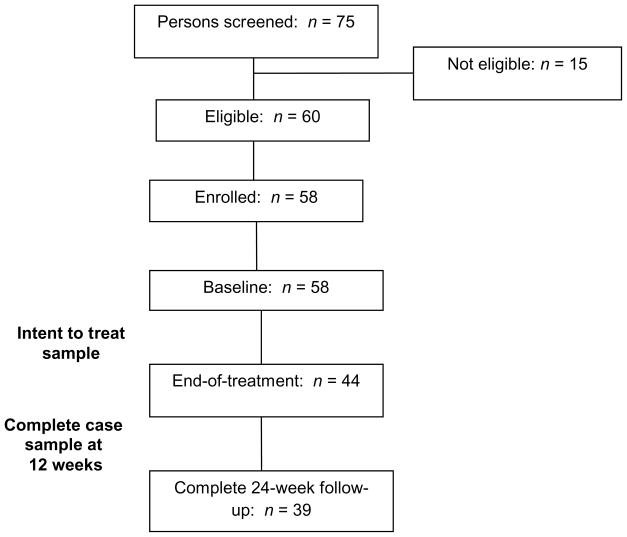

Of 75 total clients screened, 60 were eligible and 58 enrolled in the study (Figure 1). Of the 15 who were not eligible, 10 were considered mentally unstable and unable to participate, as determined by the social worker and clients’ case managers. The remaining five had recently quit but still considered themselves a smoker. Two eligible smokers were not enrolled because they refused to complete consent and/or the baseline survey.

Figure 1.

Participant Flowchart

The mean age of study participants in the intervention was 47 years (SD = 8.97 years, range 23–67 years), and 89.7% of clients were male. On average, 51.7% of clients had no high school education. Seventy four percent were unemployed. Many participants had co-morbid mental health conditions: 28.3% reported a history of schizophrenia, 50.9% depression, and 30.4% anxiety.

Study participants smoked an average of 12.4 cigarettes per day (SD = 8.5 CPD, range 3–40) and had a mean Fagerström score of 3.7 (SD=2.1), indicating low dependence. Over 70% of clients had attempted to quit at least once in their lifetime. The average readiness to quit was 6.9 for the intervention group (i.e., ready to quit in the next 30 days).

The concurrent and intervention groups did not differ significantly on baseline demographic characteristics or level of nicotine dependence, but the concurrent group reported less confidence and readiness to quit and were less likely to endorse the negative health effects of smoking (data not shown).

Retention and adherence to treatment

Seventy five percent of participants completed the 12-week end of treatment assessment. Participants who were lost to follow-up (i.e., did not complete the 12-week end of treatment survey) were, at baseline, significantly less likely to have ever attempted to quit and had lower confidence in their ability to quit for one day compared with those who completed the 12 week survey. Among the 44 participants in the intervention group who completed the 12-week assessment, 39 (88%) also completed the 24-week assessment.

The mean number of sessions attended was 7.2 among clients overall (SD = 3.2). Those participants who did not drop out attended an average of 8.2 sessions (SD = 2.8), while those lost to follow-up attended a mean of 4 sessions (SD =2.5).

Most participants used some form of pharmacotherapy (66%). Of those who used medication, 69% used one medication, 21% two, and 10% three. Twenty-five percent of clients used varenicline and 6.8% used bupropion; 20.5% used the nicotine patch, 13.6% the nicotine inhaler, and an equivalent percentage (13.6%) used nicotine gum and lozenge. Adherence rates for varenicline and bupropion were high, with clients using the medication for an average of six weeks for varenicline and five weeks for bupropion. In contrast, adherence to NRT was lower, with rates of medication use ranging from three weeks for the lozenge to 2.1 weeks for the patch.

Outcome measures

Abstinence rates

At 12-weeks, the CO-confirmed seven-day abstinence in the intent-to-treat sample was 15.5% (Table 2). We did not find an association between abstinence and baseline number of cigarettes smoked per day, use of pharmacotherapy or the number of treatment sessions attended. None of the participants in the concurrent group were abstinent at 12-weeks.

Table 2.

Smoking outcomes for intervention group at 12 weeks (end of treatment)

| Intent-to-treat sample at 12 weeks (n=58) | a Complete case sample at 12 weeks (n=44) | |

|---|---|---|

| % CO-confirmed 7-day abstinence | 15.5% | 20.5% |

| % attempted to quit for at least 1 day in past 12 weeks | 62.1% | 81.8% |

Note: CO = Carbon monoxide.

The complete case analysis (n=44) includes only those participants who completed baseline and 12-week follow-up assessments

At 24-weeks, among the 44 clients in the intervention group who completed the end of treatment survey, 13.6% were CO-confirmed abstinent (data not shown). This finding assumed that all clients who were not contacted were still smoking. The mean quit length was approximately 134 days (SD=62.3) and ranged from 15 to 180 days.

Quit Attempts

In the intent-to-treat sample, 62.1% of those in the intervention group attempted to quit during the 12-week program (Table 2). In contrast, among participants in the concurrent group, 12% made a quit attempt during this same time period.

The percentage of participants who made a quit attempt increased with the number of sessions attended. Among those who reported making a quit attempt in the previous 12 weeks, 16.7% attended four or fewer sessions, 33.3% attended 5–8 sessions and 50% attended 9–12 sessions (p=.02).

Cigarettes per day

Among participants who did not quit, the number of cigarettes smoked per day decreased from a baseline average of 13.1 to 11.4 at 12-weeks. However the decline did not reach significance (p=.07).

DISCUSSION

In this study a combination of MI+CBT + pharmacotherapy demonstrated promising effects for smoking cessation among a sheltered homeless population. Among the intervention group, CO-confirmed abstinence rates were 15.5% and 13.6% at 12 and 24-weeks, respectively. In contrast, none of the participants in the concurrent group were abstinent at 12-weeks.

Among the intervention group, the baseline average readiness score placed them in the contemplation stage, suggesting a rationale for beginning with a MI approach prior to CBT to enhance motivation and intention. Success of treatment depends on interest and readiness of smokers to change behavior, and there is evidence that treatment targeted at the current level of readiness may increase abstinence rates.22,35,36 Our findings warrant further study to understand more clearly how these psychological interventions work, taking into account the complex context of social environment and co-morbidities associated with homelessness.37

Differences between sheltered homeless smokers who chose to enroll in a treatment program and those who did not provided additional information regarding how we may improve enrollment rates. Not surprisingly, at baseline, smokers in the concurrent group were less ready to quit, less confident about quitting and less likely to endorse the negative health effects of tobacco use than the intervention group. These findings suggest a need to develop “pre treatment” interventions that address the skill, confidence, and knowledge gaps that may represent some of the barriers to committing to a course of smoking cessation treatment. Successful psychological interventions tailored to individual smoker’s readiness to quit have primarily been studied in the context of an abstinence-focused program. 22,36 Introducing behavioral approaches that “start where the client is” prior to enrollment in a smoking cessation program, may be particularly important in a population in which a large proportion of smokers are not ready to quit.

Our results also demonstrate the feasibility of enrolling and retaining homeless clients in an intensive smoking cessation protocol and obtaining follow-up assessments after treatment is completed. Over 70% of smokers completed both 12 and 24 week follow-up interviews. Further, participants in the intervention group who completed the program (i.e. completed the 12 week susrvey) attended an average of two-thirds of the 12 sessions.

Although attendance rates were encouraging, additional strategies may be needed to improve these rates, particularly if a non sheltered homeless population is to be included in subsequent studies. One approach used by Okuyemi and colleagues was to engage formerly or current homeless individuals as part of the research team who were responsible for participant contacts outside of the study. 16

Additionally, the length of the program may limit the potential for dissemination. Therefore, we need to continue to explore novel strategies for delivering care to this vulnerable population. Alternatives may include a stepped-care approach, routine integration of cessation services into other group treatment programs for homeless, interspersing the cessation intervention with other support group activities that clients find attractive, and allowing for rolling admissions in which clients can join at various points in the program and may reenroll. Several subjects who completed one 12-week program expressed a desire to reenroll in the intervention but were not allowed to because of restrictions associated with the study protocol.

Our approach of addressing tobacco use while clients were in treatment and sheltered, even transiently, took advantage of a window of opportunity to engage this hard-to-reach population. Providing care to homeless clients is complex, but previous studies support such an integrated approach, demonstrating that when comprehensive clinical and social services address the specific needs of the homeless and are located near or in shelters, utilization, compliance and follow-up to treatment are as high as for the domiciled poor.38

This study has several limitations. First, this was a non randomized study that lacked a comparison group. Based on service provision parameters established by the health care administrators at Project Renewal, our partnering organization, we were not able to randomize, blind or withhold intervention from clients. We were able to survey clients enrolled in parallel treatment groups at the study sites in order to track the natural history of cessation in a group that declined treatment, however these clients differed in key baseline indicators of cessation, including readiness and confidence to quit. Second, the small sample size and uniqueness of the Project Renewal population (gender, age, and racial ethnic composition) may limit generalizability to the broader sheltered homeless population. Finally, we found differences between dropouts and non-dropouts on certain smoking-related variables; however, we adopted the most conservative analysis for our intent-to-treat sample, assuming that all dropouts continued to smoke at the same levels and had no cessation activity. Despite these limitations, this pilot study provides initial data to inform the design and future study of smoking cessation programs in homeless populations.

CONCLUSION

Results of this study are promising, particularly given the significant co-morbidity associated with homelessness. However, larger studies are needed to identify the optimal methods for encouraging sheltered homeless clients to utilize smoking treatments, to determine the most effective smoking cessation treatment for this population and best practices for integrating smoking cessation into existing services, including the feasibility of having treatment staff deliver smoking cessation interventions. Developing effective smoking cessation interventions for this high risk underserved population is a necessary step toward reducing tobacco related health disparities.10,39

Table 1.

Demographic and smoking characteristics of intervention group at baseline

| Characteristics | Sample (n=58) |

|---|---|

| Percent or Mean (SD) | |

| Age in years | 47.0 (8.97) |

| Male | 89.7 % |

| Less than high school education | 51.7 % |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| White | 19.6 % |

| African-American | 44.6 % |

| Latino | 17.9 % |

| Other | 17.9 % |

| Unemployed | 74.1 % |

| Mental health history | |

| Schizophrenia | 28.3 % |

| Depression | 50.9 % |

| Anxiety | 30.4 % |

| Cigarettes per day | 12.4 (8.50) |

| a FTND score | 3.7 (2.14) |

| Ever attempted to quit | 73.7 % |

| Attempted to quit in last 12 months | 49.1% |

| Readiness to Quit ladder score | 6.9 (1.40) |

| Importance of quitting | |

| Somewhat or a lot | 91.4 % |

| Not important or not sure | 8.6 % |

| Thinking smoking is affecting health | |

| A lot | 78.9 % |

| Not at all/a little | 21.0 % |

Note: Values are means with standard deviations or percentages. Missing rates were negligible or zero for all variables.

FTND = Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a grant from the New York State Department of Health Tobacco Control Program. We thank Theresa Montini, PhD for her editorial assistance.

Footnotes

The material contained in this study has not been previously published and is not being considered for publication elsewhere.

References

- 1.CDC. Cigarette smoking among adults---United States, 2007. MMWR. 2008;57:1221–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Connor SE, Cook RL, Herbert MI, et al. Smoking cessation in a homeless population: there is a will, but is there a way? J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17(5):369–72. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.10630.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fischer PJ, Breakey WR. The epidemiology of alcohol, drug, and mental disorders among homeless persons. Am Psychol. 1991;46(11):1115–28. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.46.11.1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kermode M, Crofts N, Miller P, et al. Health indicators and risks among people experiencing homelessness in Melbourne, 1995–1996. Aust N Z J Public Health. 1998;22(4):464–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-842x.1998.tb01415.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.North CS, Eyrich KM, Pollio DE, Spitznagel EL. Are rates of psychiatric disorders in the homeless population changing? Am J Public Health. 2004;94(1):103–8. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.1.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kalman D, Hayes K, Colby SM, et al. Concurrent versus delayed smoking cessation treatment for persons in early alcohol recovery. A pilot study. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2001;20(3):233–8. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(00)00174-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Richter KP, Ahluwalia HK, Mosier MC, et al. A population-based study of cigarette smoking among illicit drug users in the United States. Addiction. 2002;97(7):861–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00162.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Romberger DJ, Grant K. Alcohol consumption and smoking status: the role of smoking cessation. Biomed Pharmacother. 2004;58(2):77–83. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2003.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hwang SW, Lebow JM, Bierer MF, et al. Risk factors for death in homeless adults in Boston. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158(13):1454–60. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.13.1454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barrow SM, Herman DB, Cordova P, Struening EL. Mortality among homeless shelter residents in New York City. Am J Public Health. 1999;89(4):529–34. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.4.529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cousineau MR. Health status of and access to health services by residents of urban encampments in Los Angeles. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 1997;8(1):70–82. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2010.0378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hibbs JR, Benner L, Klugman L, et al. Mortality in a cohort of homeless adults in Philadelphia. N Engl J Med. 1994;331(5):304–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199408043310506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Salit SA, Kuhn EM, Hartz AJ, et al. Hospitalization costs associated with homelessness in New York City. N Engl J Med. 1998;338(24):1734–40. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199806113382406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Butler J, Okuyemi KS, Jean S, et al. Smoking characteristics of a homeless population. Subst Abus. 2002;23(4):223–31. doi: 10.1080/08897070209511495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arnsten JH, Reid K, Bierer M, Rigotti N. Smoking behavior and interest in quitting among homeless smokers. Addict Behav. 2004;29(6):1155–61. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Okuyemi KS, Thomas JL, Hall S, et al. Smoking cessation in homeless populations: a pilot clinical trial. Nicotine Tob Res. 2006;8(5):689–99. doi: 10.1080/14622200600789841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Colby SM, Monti PM, Barnett NP, et al. Brief motivational interviewing in a hospital setting for adolescent smoking: a preliminary study. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1998;66(3):574–8. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.3.574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fiore MC, Jaen CR, Baker TB. Service. DoHaHSPH. Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence: 2008 Update. Rockville, MD: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hall SM, Reus VI, Munoz RF, et al. Nortriptyline and cognitive-behavioral therapy in the treatment of cigarette smoking. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55(8):683–90. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.8.683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Muñoz JP, Garcia T, Lisak J, Reichenbach D. Assessing the Occupational Performance Priorities of People Who Are Homeless. Occupational Therapy In Health Care. 2006;20(3):135–148. doi: 10.1080/J003v20n03_09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: preparing people for change. 2. New York: Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hall SM. Psychological interventions: state of the art. Nicotine Tob Res. 1999;1 (Suppl 2):S169–73. doi: 10.1080/14622299050012021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stitzer ML. Combined behavioral and pharmacological treatments for smoking cessation. Nicotine Tob Res. 1999;1 (Suppl 2):S181–7. doi: 10.1080/14622299050012041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. [accessed 10-30-09];UMDNJ Tobacco Dependence Program. http://www.tobaccoprogram.org/tobspeciatrain.htm.

- 25.Brown RA, Kahler CW, Niaura R, et al. Cognitive-behavioral treatment for depression in smoking cessation. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2001;69(3):471–80. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.69.3.471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ellis A, Harper RA. A guide to rational living. Englewood Cliffs, N.J: Prentice-Hall; 1961. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Spence S, Stevens R, Parks R. Cognitive dysfunction in homeless adults: a systematic review. J R Soc Med. 2004;97(8):375–379. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.97.8.375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Backer TE, Howard EA. Cognitive impairments and the prevention of homelessness: research and practice review. J Prim Prev. 2007;28(3–4):375–388. doi: 10.1007/s10935-007-0100-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Solliday-McRoy C, Campbell TC, Melchert TP, Young TJ, Cisler RA. Neuropsychological functioning of homeless men. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2004;192(7):471–478. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000131962.30547.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Okuyemi KS, Caldwell AR, Thomas JL, Born W, Richter KP, Nollen N, Braunstein K, Ahluwalia JS. Homelessness and smoking cessation: insights from focus groups. Nicotine Tob Res. 2006;8(2):287–96. doi: 10.1080/14622200500494971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Survey Questionnaire. Atlanta, Georgia: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerstrom KO. The Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence: a revision of the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire. Br J Addict. 1991;86(9):1119–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Beck AT. Depression; causes and treatment. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Biener L, Abrams DB. The Contemplation Ladder: validation of a measure of readiness to consider smoking cessation. Health Psychol. 1991;10(5):360–5. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.10.5.360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hall SM. Nicotine interventions with comorbid populations. Am J Prev Med. 2007;33(6 Suppl):S406–13. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Prochaska JO, Velicer WF, Fava JL, et al. Evaluating a population-based recruitment approach and a stage-based expert system intervention for smoking cessation. Addict Behav. 2001;26(4):583–602. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(00)00151-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Morgenstern J, McKay JR. Rethinking the paradigms that inform behavioral treatment research for substance use disorders. Addiction. 2007;102(9):1377–89. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01882.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sachs-Ericsson N, Wise E, Debrody CP, Paniucki HB. Health problems and service utilization in the homeless. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 1999;10(4):443–452. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2010.0717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Warner KE. Charting the science of the future where tobacco-control research must go. Am J Prev Med. 2007;33(6 Suppl):S314–7. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]