Abstract

The computer-based design of protein-protein interactions is a rigorous test of our understanding of molecular recognition and an attractive approach for creating novel tools for cell and molecular research. Considerable attention has been placed on redesigning the affinity and specificity of naturally occurring interactions. Several studies have shown that reducing the desolvation costs for binding while preserving shape complimentarity and hydrogen bonding is an effective strategy for improving binding affinities. In favorable cases specificity has been designed by focusing only on interactions with the target protein, while in cases with closely related off-target proteins, it has been necessary to explicitly disfavor unwanted binding partners. The rational design of protein-protein interactions from scratch is still an unsolved problem, but recent developments in flexible backbone design and energy functions hold promise for the future.

Keywords: Rational protein design, computational protein design, de novo protein design, protein-protein interactions

Introduction

Protein-protein interactions are critical to most biological processes. The ability to rationally create and destroy selective protein-protein interactions can be used to develop valuable therapeutic agents as well as novel tools for basic cell and molecular research. In general, protein designers have been focused on three problems in interface design: enhancing the affinity of naturally occurring interactions, redesigning binding specificities within a family of interactions, and designing interactions from scratch. Two common approaches for achieving these goals are directed evolution and structure-based modeling. Recently, there has been significant progress in structure-based modeling as computational methods developed for stabilizing and designing monomeric proteins have been applied to protein interfaces. These programs use rapid optimization techniques to search for sequences that pack tightly, form good hydrogen bonds, and have favorable solvation energies [1,2]. Because the physical principles that determine protein stability and protein binding affinities are similar [3], sequence optimization algorithms and energy functions developed for de novo protein design can be used largely unaltered for protein interface design.

However, protein interfaces do have unique features that make them particularly challenging to design. Interfaces between proteins that interact transiently are generally more polar than the interior of a protein core [4]. To successfully design these types of interfaces it is especially important to be able to model the subtle tradeoff between desolvation and hydrogen bond formation. Additionally, water mediated interactions are more prevalent at interfaces than in the interior of proteins [5]. Naturally occurring protein-protein interactions can be very specific despite the presence of competing proteins with very similar structures and sequences. To design high specificity interactions protein designers have been required to create new algorithms that allow for the explicit optimization of the energy gap between target and off-target interactions [6].

Here, we review recent progress in computer-based design of affinity and specificity at protein interfaces and describe new methodology that is likely to be important for achieving even more ambitious goals such as designing novel protein interactions from scratch. We focus on studies that have been not reviewed previously [2,7,8].

Designing for affinity

A systematic approach to identifying mutations that increase the affinity of a protein-protein interface will clearly be a useful complement to current selection/screening methods. Sammond et al built and tested a protocol [9] that focused on a set of detailed structure-based “rules”. Before a mutation was predicted to be stabilizing, it must pass these rules, which fall into two categories. First, it must directly increase affinity by increasing the hydrophobic surface area buried by the interface. Second, it must maintain the structure of the interface – this was assessed via the interface interaction energy, ensuring that the mutation not disrupt any hydrogen bonds or lead to burial of additional polar groups, and a requirement that the mutation not destabilize the structure of the monomeric protein (each of these were evaluated using Rosetta).

Given the physically-reasonable basis of this approach, it is not surprising that other studies on different protein-protein interfaces have led to similar conclusions [10-12]. In two separate studies, Tidor and co-workers increased protein binding affinities by searching for mutations that had a net favorable Poisson-Boltzmann continuum electrostatic solvation and interaction score [13,14]. Many of the mutations swapped polar residues buried at the interface with similar sized hydrophobic amino acids (Figure 1). Mutations that were found to increase the affinity of the SHV-1 β-lactamase / BLIP complex [15] – while not designed with a particular focus on desolvation energies – served to emphasize their importance. Additionally, a reweighting of the terms in the Rosetta energy function to identify those which best predict affinity-increasing mutations in the TCR / MHC peptide complex pointed to sterics and solvation as most important [16]. This is in keeping with the lesson that an efficient way to increase affinity – given the accuracy of current energy functions – is through creation of additional intermolecular contacts without increasing burial of charged groups. This is far from the only way to increase affinity, however, as other studies have found affinity-increasing mutations through consideration of long-range interactions between charged amino acids [17].

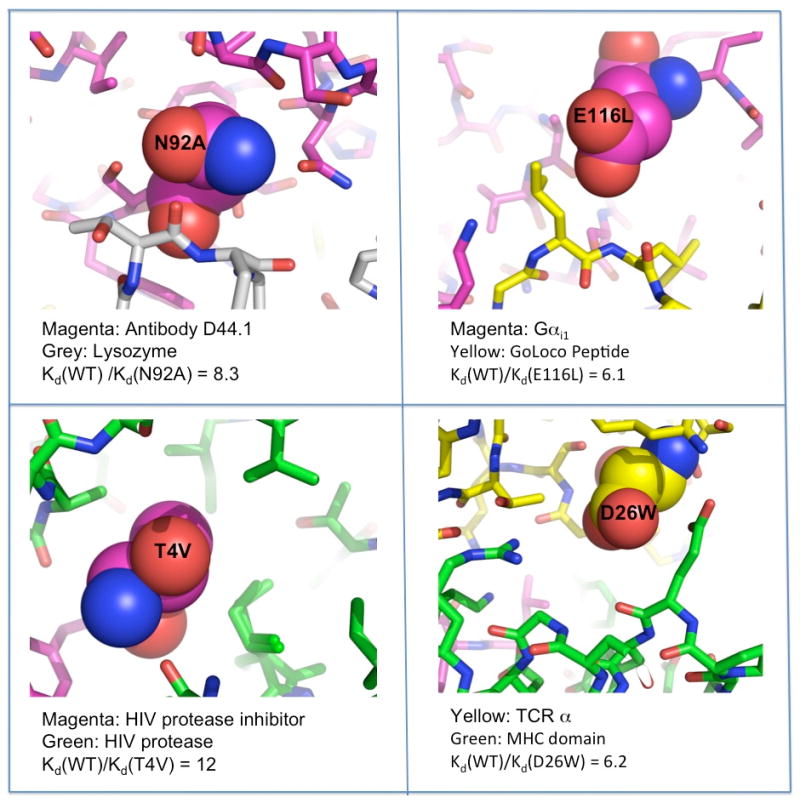

Figure 1. Reducing desolvation costs is an effective way to increase protein binding affinities.

Mutations are shown from four separate studies [9,13,14,16]. In each case, a polar residue buried at the interface (shown in space filling) was mutated to a hydrophobic residue. Between 6-fold and 12-fold increases in binding affinity were observed.

Specificity

One of the most aestetically appealing – and challenging – targets for designing specificity into protein-protein interactions is construction of an obligate heterodimeric interface from a homodimer. As pointed out by Bolon et. al. [18], this may represent the situation where “negative design” approaches are most essential. Since each component of the desired interface begins the design process with an identical backbone, “off-target” binding (ie. formation of homodimers) is especially likely. An exciting biological application of this goal has recently been realized through design of heterodimeric nucleases [19,20]; while homodimeric nucleases cleave palindromic DNA sequences, construction of heterodimeric nucleases greatly expends the universe of sequences which can be targeted. This was achieved though “implicit” negative design techniques: introduction of opposite (and hence complementary) charges on each subunit, or else introduction of “all-big” sidechains on one subunit and “all-small” sidechains on the other.

Most computational studies that have focused on changing binding specificities have tested their designs with only one or a handful of potential off-target binders. Recent work by Grigoryan et al. is groundbreaking because they computationally and experimentally test their designed bZIP-binding peptides against all 20 bZIP families in the human genome [21]. Given the overlap in sequence and structure space between bZIP families, it is not surprising that explicit negative design was required to create specific binders. Negative design was especially important for disfavoring homodimer formation by the designed proteins. To rapidly compute target and off-target binding energies a new method based on cluster expansion was developed that allows one to convert a structure-based model into a sequence-based scoring function [22]. Integer linear programming was then combined with rapid energy evaluation by cluster expansion to identify sequences that had specified stabilities and specificities [23]. It will be exciting to see if a similar approach can be used to design specificity in systems that are not as structurally conserved as the bZIP peptides. One potential limitation of the cluster expansion method is that it requires predetermined backbone coordinates for the target interactions, although it has been shown that cluster expansion can be accurately applied to families of very similar backbones [24]. In cases where “undesirable” targets exhibit significant structural differences from the “desirable” target, examples continue to accumulate in support of the idea that mutations neutral or stabilizing to the “desirable” target are on average destabilizing to “undesirable” targets, and hence specificity can be achieved through explicit consideration of the target interaction only [25-28][29].

Promiscuity

While rational design of a single protein sequence that binds a predetermined set of partners remains an unattained goal, the groundwork towards this has been laid through “multi-constraint” design [30]. Using a set of proteins known to bind more than one partner, Humphris and Kortemme redesigned each protein either with a single constraint (to bind one partner in particular) or with multiple constraints (to optimally bind all known partners simultaneously). With this experimental setup, divergence of the single-constraint designs from the multiple-constraint design is indicative of compromise made by the promiscuous protein in order to maintain binding to multiple partners. Surprisingly, the degree of compromise in the sequence of most promiscuous proteins was found to be minimal; the structural basis for this phenomenom was traced to the fact that diverse interaction partners had evolved similar means to form key interactions with the promiscuous protein. In contrast, a small number of proteins – “hub” proteins with an exceptionally large number of interaction partners such as ubiquitin – were found to have evolved their vast promiscuousity via a different approach. Extensive compromise over multiple surface patches was identified, probably representing the primary source of selective pressure on these protein sequences. These exciting revelations may provide direction for future efforts at rationally designing multi-functional proteins.

Methods and Future Goals

Despite considerable success in the redesign of naturally occurring protein-protein interfaces, building protein-protein interactions from scratch has proven to be a challenging problem for computational design [31]. In one case, grafting key residues from a known interface into a new scaffold protein created a novel interaction, but this is not a viable approach when the target interface has no known binding partners [32]. In contrast to modeling-based approaches, there are many examples in which directed evolution has been used to design novel protein binders [33,34]. Strikingly, selecting from protein libraries that have surface loops containing only tyrosines and serines is sufficient to generate high affinity binders [35]. Like naturally occurring antibodies, the sequences and structures of the designed loops co-evolve to present complementary surfaces to the target protein. These results highlight the need for computational protocols to sample backbone conformational space as well as sequence space when designing protein interfaces.

A variety of approaches have been developed for combining backbone optimization with sequence optimization. Humpris et al. showed that a pre-generated ensemble of backbones built with small perturbations to Cα-Cβ bond vectors followed by sequence optimization improved recapitulation of favorable sequences at a protein-protein interface [36]. Similar backbone perturbations have been incorporated into dead end elimination algorithms for simultaneous optimization of backbone and sequence [37]. Normal mode analysis has also been used to pre-generate alternative backbones and used to design new helical peptides that bind Bcl-xL [38]. Backbone optimization can also be iterated with sequence optimization. This strategy was recently used to design new conformations in a protein loop, a potential step in de novo interface design [39]. In all of these examples, relatively small perturbations were made to the protein backbone. In contrast, large changes in loop structure are frequently seen in antibodies and binders evolved in the laboratory. Inclusion of large conformational perturbations in computational design will be challenging but potentially useful for creating novel interfaces.

In addition to efficient methods for sampling backbone and sequence space, it is critical to have an accurate energy function for evaluating the relative favorability of different models [40-42][43]. After producing a set of models, it is also common to use a set of structure-based filters to eliminate models that have defects. For example, a high number of buried unsatisfied hydrogen bonds or the presence of low probability side chain rotamers may be cause to throw out a model. It is particularly useful to have a way to compare the quality of the design models to naturally occurring proteins. Sheffler and Baker have created a procedure for identifying cavities within a protein and estimating the probability of observing a similar cavity in high-resolution crystal structures [44]. Comparisons of this type may indicate that certain terms in the energy function are not being emphasized properly, or that more conformational sampling needs to be performed in order to find higher quality design models.

As methods in computational interface design improve, an important aim will be to move beyond model studies and create proteins that are useful to others. When faced with pragmatic goals, it may be advantageous to combine computational methods with other techniques for protein engineering, such as directed evolution. Whether the goal is binding a specific target surface on a protein or designing a new enzyme, directed evolution usually requires that the starting sequences for selection contain some members that are at least partially functional. Computational design may be useful for creating libraries or individual sequences enriched in the target functionality, and thus provide a good starting point for directed evolution [45,46]. This approach was used in the recent design of an enzyme for a novel reaction [47]. The long-term challenge is to learn from the optimization of current designs imparted by directed evolution, to further improve rational approaches.

Conclusions

The successful redesign of protein-protein binding affinities and specificities indicate that computational design is a viable approach for redesigning protein-signaling pathways. It is clear that explicit negative design will be needed in some cases to achieve specificity, however, techniques that focus on only positive design are suitable when the targets are significantly different in structure. Directed evolution experiments have shown that relatively simple libraries can be used to create novel protein binders, and suggests means to improving current computational design methodologies.

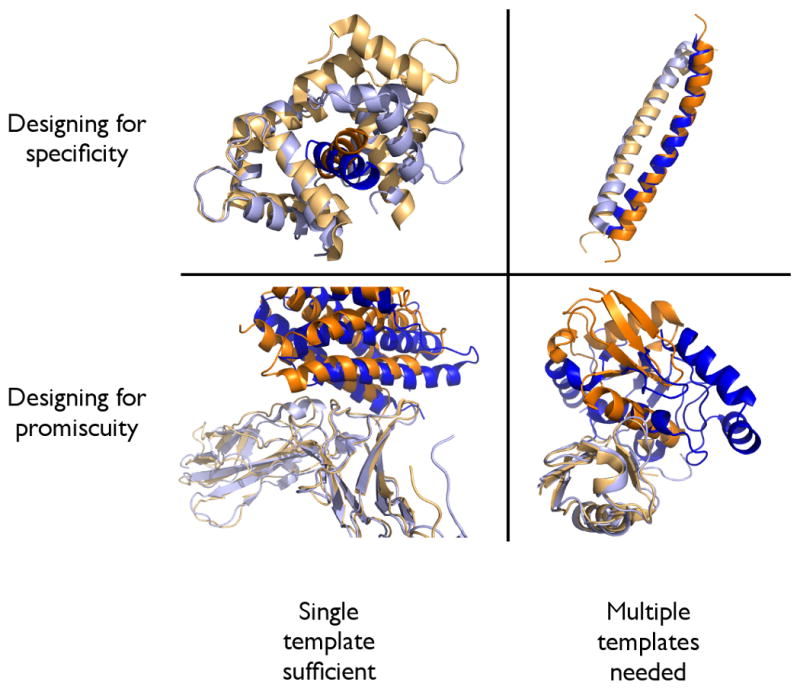

Figure 2. The use of single vs. multiple templates in studies of specificity/promiscuity.

(TOP LEFT) Calmodulin (light orange/light blue) bound to two different peptides (orange/blue). Because the conformation of calmodulin and the peptide orientation are signficantly different, mutations designed in the context of one interface are essentially random in the context of the other interface. These can therefore be assumed to generally be destabilizing to the “competing” interface, allowing specificity to be achieved through consideration of only a single template [27] (implicit negative design). (TOP RIGHT) By contrast, structures of bZIP coiled-coil structures are in general very similar to each other (shown are the c-Jun homodimer and the c-Fos/c-Jun heterodimer, with c-Jun in light orange/light blue/orange and c-Fos in blue). For this reason, consideration of multiple competing templates is critical for achieving specificity [21] (explicit negative design). (BOTTOM LEFT) Taking cues from Nature, promiscuous proteins that recognize similar proteins often reuse specific residue contacts (gp130 (light orange/light blue) is shown bound to IL-6 (orange) and a viral analog of IL-6 (blue)) [36]. Design problems falling into this category may not require explicit consideration of each template, since mutations to the promiscuous protein can be expected to have a similar effect on all binding partners. (BOTTOM RIGHT) By constrast, designing a promiscuous protein that recognizes vastly different partners (ubiquitin (light orange/light blue) is shown with Hrs (orange) and UBC1 (blue)) will require extensive compromise in selecting the identities of surface residues [36]. In such cases, it is therefore anticipated that multiple design templates must be considered explicitly.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grant RO1GM073960 to B.K.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Boas FE, Harbury PB. Potential energy functions for protein design. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2007;17:199–204. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2007.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lippow SM, Tidor B. Progress in computational protein design. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2007;18:305–311. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2007.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cohen M, Reichmann D, Neuvirth H, Schreiber G. Similar chemistry, but different bond preferences in inter versus intra-protein interactions. Proteins. 2008;72:741–753. doi: 10.1002/prot.21960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ofran Y, Rost B. Analysing six types of protein-protein interfaces. J Mol Biol. 2003;325:377–387. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)01223-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reichmann D, Phillip Y, Carmi A, Schreiber G. On the contribution of water-mediated interactions to protein-complex stability. Biochemistry. 2008;47:1051–1060. doi: 10.1021/bi7019639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Havranek JJ, Harbury PB. Automated design of specificity in molecular recognition. Nat Struct Biol. 2003;10:45–52. doi: 10.1038/nsb877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kortemme T, Baker D. Computational design of protein-protein interactions. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2004;8:91–97. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2003.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alvizo O, Allen BD, Mayo SL. Computational protein design promises to revolutionize protein engineering. Biotechniques. 2007;42:31, 33, 35. doi: 10.2144/000112336. passim. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sammond DW, Eletr ZM, Purbeck C, Kimple RJ, Siderovski DP, Kuhlman B. Structure-based protocol for identifying mutations that enhance protein-protein binding affinities. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2007;371:1392–1404. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.05.096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peimbert M, Dominguez-Ramirez L, Fernandez-Velasco DA. Hydrophobic repacking of the dimer interface of triosephosphate isomerase by in silico design and directed evolution. Biochemistry. 2008;47:5556–5564. doi: 10.1021/bi702502k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wakabayashi H, Griffiths AE, Fay PJ. Combining mutations of charged residues at the A2 domain interface enhances factor VIII stability over single point mutations. J Thromb Haemost. 2009;7:438–444. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2008.03256.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wakabayashi H, Varfaj F, Deangelis J, Fay PJ. Generation of enhanced stability factor VIII variants by replacement of charged residues at the A2 domain interface. Blood. 2008;112:2761–2769. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-02-142158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Altman MD, Nalivaika EA, Prabu-Jeyabalan M, Schiffer CA, Tidor B. Computational design and experimental study of tighter binding peptides to an inactivated mutant of HIV-1 protease. Proteins-Structure Function and Bioinformatics. 2008;70:678–694. doi: 10.1002/prot.21514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lippow SM, Wittrup KD, Tidor B. Computational design of antibody-affinity improvement beyond in vivo maturation. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25:1171–1176. doi: 10.1038/nbt1336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reynolds KA, Hanes MS, Thomson JM, Antczak AJ, Berger JM, Bonomo RA, Kirsch JF, Handel TM. Computational Redesign of the SHV-1 beta-Lactamase/beta-Lactamase Inhibitor Protein Interface. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2008;382:1265–1275. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.05.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haidar JN, Pierce B, Yu Y, Tong WW, Li M, Weng ZP. Structure-based design of a T-cell receptor leads to nearly 100-fold improvement in binding affinity for pepMHC. Proteins-Structure Function and Bioinformatics. 2009;74:948–960. doi: 10.1002/prot.22203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schreiber G, Shaul Y, Gottschalk KE. Electrostatic design of protein-protein association rates. Methods Mol Biol. 2006;340:235–249. doi: 10.1385/1-59745-116-9:235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bolon DN, Grant RA, Baker TA, Sauer RT. Specificity versus stability in computational protein design. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:12724–12729. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506124102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Szczepek M, Brondani V, Buchel J, Serrano L, Segal DJ, Cathomen T. Structure-based redesign of the dimerization interface reduces the toxicity of zinc-finger nucleases. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25:786–793. doi: 10.1038/nbt1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fajardo-Sanchez E, Stricher F, Paques F, Isalan M, Serrano L. Computer design of obligate heterodimer meganucleases allows efficient cutting of custom DNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:2163–2173. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grigoryan G, Reinke AW, Keating AE. Design of protein-interaction specificity gives selective bZIP-binding peptides. Nature. 2009;458:859–864. doi: 10.1038/nature07885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grigoryan G, Zhou F, Lustig SR, Ceder G, Morgan D, Keating AE. Ultra-fast evaluation of protein energies directly from sequence. PLoS Comput Biol. 2006;2:e63. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0020063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kingsford CL, Chazelle B, Singh M. Solving and analyzing side-chain positioning problems using linear and integer programming. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:1028–1036. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Apgar JR, Hahn S, Grigoryan G, Keating AE. Cluster expansion models for flexible-backbone protein energetics. J Comput Chem. 2009 doi: 10.1002/jcc.21249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shifman JM, Mayo SL. Exploring the origins of binding specificity through the computational redesign of calmodulin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:13274–13279. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2234277100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen CY, Georgiev I, Anderson AC, Donald BR. Computational structure-based redesign of enzyme activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:3764–3769. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900266106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yosef E, Politi R, Choi MH, Shifman JM. Computational design of calmodulin mutants with up to 900-fold increase in binding specificity. J Mol Biol. 2009;385:1470–1480. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.09.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tur V, van der Sloot AM, Reis CR, Szegezdi E, Cool RH, Samali A, Serrano L, Quax WJ. DR4-selective tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) variants obtained by structure-based design. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:20560–20568. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800457200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Joachimiak LA, Kortemme T, Stoddard BL, Baker D. Computational design of a new hydrogen bond network and at least a 300-fold specificity switch at a protein-protein interface. J Mol Biol. 2006;361:195–208. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Humphris EL, Kortemme T. Design of multi-specificity in protein interfaces. PLoS Comput Biol. 2007;3:e164. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0030164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huang PS, Love JJ, Mayo SL. A de novo designed protein protein interface. Protein Sci. 2007;16:2770–2774. doi: 10.1110/ps.073125207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu S, Zhu X, Liang H, Cao A, Chang Z, Lai L. Nonnatural protein-protein interaction-pair design by key residues grafting. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:5330–5335. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606198104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sidhu SS, Koide S. Phage display for engineering and analyzing protein interaction interfaces. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2007;17:481–487. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2007.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zahnd C, Amstutz P, Pluckthun A. Ribosome display: selecting and evolving proteins in vitro that specifically bind to a target. Nat Methods. 2007;4:269–279. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Koide S, Sidhu SS. The Importance of Being Tyrosine: Lessons in Molecular Recognition from Minimalist Synthetic Binding Proteins. ACS Chem Biol. 2009 doi: 10.1021/cb800314v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Humphris EL, Kortemme T. Prediction of Protein-Protein Interface Sequence Diversity Using Flexible Backbone Computational Protein Design. Structure. 2008;16:1777–1788. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2008.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Georgiev I, Keedy D, Richardson JS, Richardson DC, Donald BR. Algorithm for backrub motions in protein design. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:I196–I204. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fu X, Apgar JR, Keating AE. Modeling backbone flexibility to achieve sequence diversity: the design of novel alpha-helical ligands for Bcl-xL. J Mol Biol. 2007;371:1099–1117. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.04.069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hu X, Wang H, Ke H, Kuhlman B. High-resolution design of a protein loop. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:17668–17673. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707977104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Clark LA, van Vlijmen HWT. A knowledge-based forcefield for protein-protein interface design. Proteins-Structure Function and Bioinformatics. 2008;70:1540–1550. doi: 10.1002/prot.21694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Grigoryan G, Ochoa A, Keating AE. Computing van der Waals energies in the context of the rotamer approximation. Proteins. 2007;68:863–878. doi: 10.1002/prot.21470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Alvizo O, Mayo SL. Evaluating and optimizing computational protein design force fields using fixed composition-based negative design. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105:12242–12247. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805858105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vizcarra CL, Zhang N, Marshall SA, Wingreen NS, Zeng C, Mayo SL. An improved pairwise decomposable finite-difference Poisson-Boltzmann method for computational protein design. J Comput Chem. 2008;29:1153–1162. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sheffler W, Baker D. RosettaHoles: Rapid assessment of protein core packing for structure prediction, refinement, design, and validation. Protein Science. 2009;18:229–239. doi: 10.1002/pro.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mena MA, Treynor TP, Mayo SL, Daugherty PS. Blue fluorescent proteins with enhanced brightness and photostability from a structurally targeted library. Nat Biotechnol. 2006;24:1569–1571. doi: 10.1038/nbt1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Voigt CA, Mayo SL, Arnold FH, Wang ZG. Computationally focusing the directed evolution of proteins. J Cell Biochem Suppl. 2001 37:58–63. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rothlisberger D, Khersonsky O, Wollacott AM, Jiang L, DeChancie J, Betker J, Gallaher JL, Althoff EA, Zanghellini A, Dym O, et al. Kemp elimination catalysts by computational enzyme design. Nature. 2008;453:190–U194. doi: 10.1038/nature06879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Commented References

- *.Lippow SM, Wittrup KD, Tidor B. Computational design of antibody-affinity improvement beyond in vivo maturation. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25:1171–1176. doi: 10.1038/nbt1336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Affinity enhancing mutations were identified by searching for mutations that increase the favorability of electrostatic solvation and interaction energies calculated with the Poisson-Boltzmann equation.

- **.Grigoryan G, Reinke AW, Keating AE. Design of protein-interaction specificity gives selective bZIP-binding peptides. Nature. 2009;458:859–864. doi: 10.1038/nature07885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This is the first large-scale demonstration of computational protein design being used to redesign binding specificities. Explicit consideration of off-target binders was required to achieve specificity.

- **.Humphris EL, Kortemme T. Design of multi-specificity in protein interfaces. PLoS Comput Biol. 2007;3:e164. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0030164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Introduction of multi-constraint design methodology allowed the authors to estimate the degree of “compromise” encoded in sequences of promiscuous proteins. Surprisingly, little evidence for compromise was identified in most cases.

- *.Yosef E, Politi R, Choi MH, Shifman JM. Computational design of calmodulin mutants with up to 900-fold increase in binding specificity. J Mol Biol. 2009;385:1470–1480. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.09.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; In this case specificity was achieved by focusing only on the target peptide. Significant structural differences between the target and competing peptides may be the reason explicit negative design was not required.

- *.Humphris EL, Kortemme T. Prediction of Protein-Protein Interface Sequence Diversity Using Flexible Backbone Computational Protein Design. Structure. 2008;16:1777–1788. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2008.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Introducing small perturbations to Cα-Cβ bond vectors allowed for better recapitulation of sequences known to bind the target peptide. This may be an effective strategy for creating directed libraries for protein interface design.

- *.Sheffler W, Baker D. RosettaHoles: Rapid assessment of protein core packing for structure prediction, refinement, design, and validation. Protein Science. 2009;18:229–239. doi: 10.1002/pro.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study demonstrates the creation of a scoring term that calculates the probability of observing a particular structural feature in the protein database. Scores of this type provide a way to assess the overall quality of a set of design models.